ABSTRACT

The purpose of the study was to analyse how cross-border commuting differed from intranational commuting in Sweden, and how cross-border mobilities affected spatial integration. The authors analysed patterns and spatial flows of cross-border commuting by comparing them with characteristics of intranational commuting. In the article, they explore the assumption that the border constitutes an ‘engine’ for work-related mobility, which affects processes of spatial integration in cross-border areas. The empirical material comprised data from surveys of commuting from the Swedish county of Värmland to Norway and commuting within Värmland. The findings showed that cross-border commuting shared common features with intranational commuting, including how the frequency of commuting was dependent on distance. The motives for commuting differed, and the reasons for working in Norway were economic rather than professional. In terms of spatial integration, cross-border commuting was mainly one-directional, from Sweden to Norway, while leisure mobility and migration tended to be in the opposite direction. The authors conclude that the border region is characterised by integration through specialisation, which involves a permanent state of ‘transient’ mobility. Thus, a win-win situation can be distinguished, in which the border serves as a resource and an ‘engine’ for cross-border integration, mobility and economic activities.

Introduction

Few studies have analysed commuting in a cross-border context in relation to ‘ordinary’ commuting within national regions (Schwab & Toepel Citation2006; Gottholmseder & Theurl Citation2007; Buch et al. Citation2009). In this article, we explore the assumption that the border may constitute an important factor as an ‘engine’ for work-related mobility compared with other forms of commuting (Olsson et al. Citation2012). Analysing the border as an engine can be compared to viewing borders as symbolic, economic, or political resources, which requires cross-border activities by different types of actors (Sohn Citation2014). Borders can thus have a dual function: they can have a restrictive role that can slow down and hinder interactions due to national differentials, and they can provide new opportunities and generate positive economic spillovers (Sohn & Licheron Citation2017).

Cooper et al. emphasise how borders are constantly ‘made’ by ordinary people through ‘borderwork’, as ‘borders mean different things to different people and act differently on different groups’ (Cooper et al. Citation2014, 17). From this perspective, borders do not merely include the regulation of national territorial borders in a more traditional sense, they also ‘control mobility rather than territory’ (Dürrschmidt Citation2007, 56). Borders may boost work-related mobility due to economic differences in wages and housing, but also constitute physical, social, cultural, and mental barriers due to cultural and political differences and bureaucratic systems (Paasi & Prokkola Citation2008; Mathä & Wintr Citation2009; Cooper Citation2015). Borders may affect not only commuting but also other types of cross-border mobilities such as tourism, shopping, and migration. Together, such mobilities affect how border regions are spatially integrated, for example depending on whether they are specialised or converged, or depending on their links to urban and rural areas in each country (Durand Citation2015). The number of commuters from Sweden to Norway has increased significantly in the past few years, and in Värmland County (Värmlands län) () the share of cross-border commuters is more than four times as high as the general share of cross-border commuters from Sweden to Norway. This is partly related to the county’s proximity to Norway, and partly due to a relatively high unemployment rate in Sweden (Region Värmland Citation2015).

Fig. 1. The location of the study area, with the Swedish–Norwegian border region (left) and municipalities (right)

Our first research question is: Do cross-border commuting patterns differ from intranational commuting? To answer this question, we analyse commuting in terms of its frequency as well as in relation to means of transport, motives, and commuting time and distance. Our second research question is: How do commuting and other cross-border mobilities affect the spatial integration in the Swedish–Norwegian border region? In previous studies of commuting in cross-border areas, researchers adopted a spatial and functional perspective based on theories of cross-border integration that emphasised the economic differences and specialisations of border regions as driving forces for cross-border mobility (Buch et al. Citation2009; Decoville et al. Citation2013; Durand Citation2015).

In this article, we explore the border as an ‘engine’ and a resource for spatial integration in a Scandinavian context, based on a case study of a Swedish–Norwegian border region. In the county of Värmland, commuting connects the Swedish border region to adjacent Norwegian border region, as do other forms of cross-border mobilities. Commuting across the Swedish–Norwegian border is mainly from Sweden to Norway, while cross-border mobilities such as shopping and second home tourism are in the opposite direction. This article is primarily a meta-analysis aimed at providing an overview of labour-related mobility in the Swedish–Norwegian cross-border region, and is intended to serve as an important departure point for future studies of cross-border commuting from both an individual perspective and local perspective.

Commuting across borders

Travelling long distances for work has increasingly had positive connotations in strategies for regional development, growth, and innovation. International mobility for work and leisure has become a norm and symbolic of freedom, at least in parts of the Western world (Uteng & Cresswell Citation2008; Gil Solá Citation2013). In this article, mobility is defined as ‘repeated, every day, spatial movement’ (Gil Solá Citation2013, 41). Work-related mobility has increased as a result of better infrastructure and modes of transport, as well as the transition to a more functionally organised society, in which services and activities have been concentrated in fewer locations. Consequently, this has resulted in longer distances between the work location and place of residence (Frändberg et al. Citation2005; Vilhelmson Citation2014; Gottfridsson & Möller Citation2016).

Research on intranational commuting in the Swedish context has been fairly extensive and has included topics such as long-distance commuting (Öhman & Lindgren Citation2003; Sandow Citation2008; Sandow & Westin Citation2010; Scholten & Jönsson Citation2010), commuting in rural and urban settings (Vilhelmson Citation2005; Sandow Citation2008), and the socio-economic dimensions of work-related travel (Gottfridsson Citation2007; Sandow Citation2011). Commuting is influenced by several factors, including a mix of structural conditions and individual preferences and/or motives. Additionally, commuting is affected by societal norms and attitudes that advocate increased mobility as well as by labour and housing market conditions and available infrastructure (Gil Solá Citation2013; Gottfridsson & Möller Citation2016).

In Sweden, aims to facilitate work-related mobility through the expansion of labour market regions (regionförstoring) have been on the political agenda. Larger labour market regions have constituted a model for improving individuals’ access to well-paid jobs that require higher qualifications, while also making companies and organisations more competitive and economically successful in the region and promoting international competition for human capital and knowledge (Friberg Citation2008; Gil Solá Citation2013). However, commuting is also affected by working conditions, including working hours and place of work. Socio-economic variables such as education, income, gender, and family life affect commuting patterns, along with individual motives that affect choices about where to live and work, as well as lifestyle preferences (Gottfridsson Citation2007).

Huber & Nowotny (Citation2013) claim that cross-border commuting has mainly been ignored as an area of research in the theoretical literature of international mobility (Huber & Nowotny Citation2013). A few studies of cross-border commuting as an empirical phenomenon have been published with focus on the labour market and showing that certain professions and occupations are more attractive to cross-border commuters than to commuters from other labour market regions (Hansen Citation2000; Schwab & Toepel Citation2006; Gottholmseder & Theurl Citation2007; Buch et al. Citation2009).

Some authors have concluded that cross-border commuting does not differ significantly from intranational commuting. According to Hansen & Nahrstedt (Citation2000), the main motives for cross-border commuting include better wages and employment conditions, housing markets, and personal relations (e.g. family), which also affect other forms of commuting (Hansen & Nahrstedt Citation2000). Other studies have focused on the meaning and consequences of national borders as additional factors that affect people’s cross-border mobility, including bureaucratic and juridical obstacles, such as social insurance and tax regulations (Mathä & Wintr Citation2009).

Van Houtum & van der Velde (Citation2004) point to sociocultural factors in terms of perceptions of national differences that characterise people in border areas, and how such differences may create a sense of ‘us’ and ‘them’ and thus contribute to less work-related mobility across borders (van Houtum & van der Velde Citation2004). Following a study conducted in Vorarlberg in Austria, Gottholmseder & Theurl (Citation2007) claim that the cross-border commuters were characterised by living close to the border and that their decision to commute across it was influenced by issues such as their educational and professional background, as well as the need for labour and skills in the host country. Moreover, the household played an important role, and the results of a study conducted by Gottholmseder & Theurl (Citation2007) showed that the majority of cross-border commuters were male, lived near the border, and in the case of those with families with children, their partners did not commute across the border for work.

The border as a barrier or a resource for spatial integration

Due to their proximity, cross-border regions often share a common history as well as a cultural and economic context (Laakso et al. Citation2013). However, Lundquist & Trippl (Citation2009) emphasise the diversity of cross-border regions in terms of economic development, political climate, and cultural traditions. These differences may constitute barriers to cross-border integration due to unequal relations between those living in the border regions. At the same time, such disparities may become driving forces for successful integration processes (Lundquist & Trippl Citation2009; Decoville et al. Citation2013).

Durand (Citation2015) describes the transformation and complexities of border regions from two different perspectives: ‘de-bordering’ and ‘re-bordering’. The first perspective, ‘de-bordering’, downplays the effects of borders and promotes networks and freedom of movement and mobility between border regions. The second perspective, ‘re-bordering’, emphasises the roles of borders in national security and the protection of regions and nation states. The ‘de-bordering’ perspective reflects a more functional view of cross-border regions as aimed at economic integration and exchange between territories in terms of work mobility, tourism, shopping, and communication networks (Durand Citation2015). Rather than being defined by administrative borders, functional regions are often defined through existing work-related mobility patterns, including flows of commuters. This has also been evident within research on border regions, in which mathematical models have been developed and analyses of accessibility and the distances involved in cross-border interactions have been performed (Laakso et al. Citation2013; Durand Citation2015).

Sohn (Citation2014) discusses the role of borders as a resource and has formulated two types of cross-border integration: the ‘geo-economic model’ and the ‘territorial project’. In the geo-economic model, the main benefit of the border is differential benefits connected to differences in costs and prices. Labour and residential markets, as well as commerce and services are identified as the main domains affecting the model. Thus, the geo-economic model has close similarities with Durand’s functional view of cross-border regions (Durand Citation2015). In the second type of cross-border integration, the territorial project, place-making is the main objective and the key variables include mutual learning, common understanding, trust, and sense of belonging. The two types of cross-border integration are not mutually exclusive, and Sohn (Citation2014) shows how different European cases can be either predominantly one of these two types or different types of hybrid assemblages.

Durand acknowledges different dimensions of spatial integration, including ‘convergence and territorial homogenization’ (Durand Citation2015, 314). Thus, the character and diversity of border regions are important for explaining how they relate to one another. This includes spatial specialisation of border areas and their unique characteristics that attract workers and migrants to them, while being affected by housing and labour markets (Durand Citation2015). Decoville et al. (Citation2013) show how cross-border commuting is part of this process through three forms of spatial integration: (1) integration by specialisation, (2) integration by polarisation, and (3) integration by osmosis. In the first form of integration, which focuses on functional specialisation, work-related cross-border mobility takes place in one direction (mainly to urban centres), whereas migration flows take place in the opposite direction (to the periphery). The Copenhagen–Malmö region is often viewed as an example of integration by specialisation. Thus, it can be more beneficial to live on one side of the border and work on the other side of the border. In this case, both border regions may be regarded as ‘winners’ in the spatial integration process since they complement each other. However, the integration process also results in a concentration of economic activities in urban regions, while areas that are more peripheral remain ‘dormitory areas’ (Decoville et al. Citation2013).

The second form of spatial integration, integration by polarisation, shows how both work-related and residential mobility are one-directional, towards the urban centre. Consequently, it is more beneficial to work and live on one side of the border. However, the high demand for housing has triggered increases in property prices in the cities, which has resulted in mainly higher income households moving into the urban areas, as has been the case in Luxemburg and Basel. The third form of spatial integration, integration by osmosis, shows how the flows of commuters and residential mobility go in both directions across the border, reflecting a more balanced and converged border region in terms of labour and housing markets. The relation between the centre and periphery is less pronounced, as in the case of Lille or Aachen-Liege-Maastricht (Decoville et al. Citation2013).

The Swedish–Norwegian border region

The Swedish–Norwegian border region is characterised by cross-border mobility in multiple forms, including cross-border shopping, tourism, migration, smuggling, and temporary forms of labour mobility such as seasonal workers and cross-border commuters (Ericsson et al. Citation2012a; Möller et al. Citation2012; Citation2014; Tolgensbakk Citation2015). There is a long history of flows of people, goods, and services across the border, but the flows have taken different forms, have taken place for different reasons, and have varied in direction. The Nordic countries have a long history of political and economic cooperation and strong traditions for practising a high degree of permeability with respect to their national borders. In 1952, the Nordic Passport Union was established, giving Nordic citizens the freedom to settle in any of the Nordic countries, and in 1981 the Agreement Concerning a Nordic Common Labour Market was signed by the Nordic governments (i.e. the governments of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden). Since then, an extensive elaborate political cooperation has developed across the Swedish–Norwegian border, including border committees, cross-border policies, and regional development projects (Berger et al. Citation2007; Svensson & Öjehag Citation2012). Key issues have long been infrastructural investments and tourism development, in order to reduce barriers and friction relating to mobility. A number of authorities on both sides of the border have formed a cooperative body called Grensetjänsten, a border service that handles questions from citizens and companies about mobility across the border (Svensson & Öjehag Citation2012).

The extensive cross-border interactions between Sweden and Norway have been eased by similarities in languages, societal structures, and cultural values. Based on the typology of borderlands developed by Martinez (Citation1994), the Swedish–Norwegian border region can be categorised as an ‘interdependent borderland’, where the international relations are stable while allowing a significant amount of exchange. However, the cross-border interactions cannot be described as completely free flowing, nor can the Swedish–Norwegian ‘borderlanders’ be described as having a common social system of the type that characterises ‘integrated borderlands’ in Martinez’s typology. Elsewhere in Europe, obstacles to cross-border mobility are different languages, lack of information and relevant knowledge, labour market regulations, difficulties relating to acceptance of qualifications, and differences in tax and social security systems (Nerb et al. Citation2009).

Cross-border labour markets and commuting

Since Norway found petroleum in the North Sea in the 1970s, the development of the country’s economy has differed from that of Sweden’s economy. Although Sweden was once the stronger ‘big brother’ in terms of its economy, it was hit by the industrial crisis and escalating unemployment during the 1970s. The Norwegian economy was overheated and under pressure, and by attracting Swedish workers to the labour market, a win-win-situation evolved that also could reduce the costs of social welfare benefits in Sweden (Ørbeck & Gløtvold-Solbu Citation2012).

The economic imbalances between Norway and Sweden have prevailed but have stabilised. Today, due to a still flourishing Norwegian economy, including higher wages and demands for labour, the flows of labour including seasonal workers and daily or weekly commuters are mainly one-directional, from Sweden to Norway (Olsson et al. Citation2011). The economic development in the Oslo region has been particularly strong, and the Norwegian capital functions as a centre of gravity for its hinterland, including the part adjacent to the Swedish border region (Tóth et al. Citation2014). The social and economic development of parts of the region closest to the border has weakened over the years, especially on the Swedish side (Medeiros Citation2014). Ørbeck & Gløtvold-Solbu (Citation2012) estimate that 80,000 Swedes were working in Norway in 2009, which was 3% of the total in employment in Norway, and included 21,800 Swedes who were registered in 2009 as living and working in Norway for more than six months. Additionally, a group of seasonal workers from Sweden work in Norway for less than six months per year; Ørbeck & Gløtvold-Solbu (Citation2012) estimate that this group totalled c.27,700 people in 2009.

The number of commuters from Sweden to Norway has increased significantly and more than doubled in the past few years, from 13,200 in 2004 to 27,200 in 2012 (Region Värmland Citation2013). In 2012, 5400 inhabitants in Värmland commuted to Norway (Region Värmland Citation2013). Given that the share of cross-border commuters in the county is above the national average, cross-border commuting is not an unusual adjustment in Värmland, where it represents 4% of the population in the age range 20–64 years (Region Värmland Citation2013) ().

Table 1. Intranational and cross-border commuting in Sweden and the county of Värmland (Sources: Statistics Sweden Citation2012; Region Värmland Citation2015)

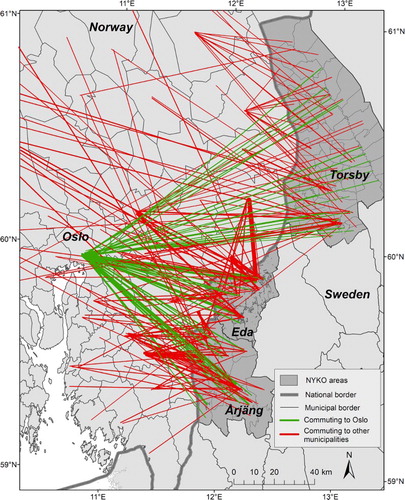

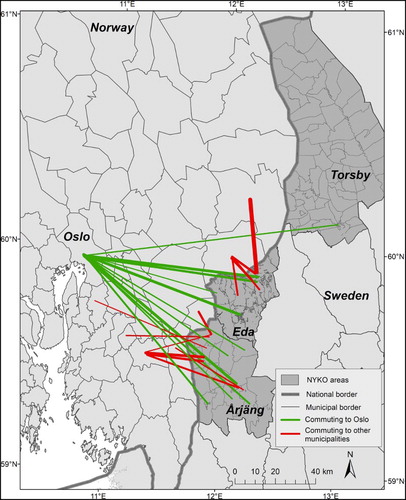

For our study, we selected three border municipalities that represent a significant share (36%) of the cross-border commuters in Värmland County: Torsby, Eda, and Årjäng (StatNord Citation2012) (for the location, of the municipalities, see ). These municipalities are regarded as remote in the Swedish context, but distances from densely populated areas in Norway are less than from densely populated areas in Sweden. Commuting across the border from Årjäng and Eda has been the subject of earlier research, but few studies have included the northernmost of the three municipalities, Torsby (Olsson et al. Citation2011).

In common with Årjäng and Eda, many residents in Torsby commute to work in Norway (StatNord Citation2012). There is less cross-border commuting from Torsby than from Eda and Årjäng: 35% of all commuting from Torsby is across the border, compared with 44% from Årjäng and 63% from Eda. There is slightly less commuting from all three municipalities to other Swedish municipalities than from other municipalities in Värmland. From Årjäng, there are more commuters to Norway than to municipalities in Sweden (Statistics Sweden Citation2012; StatNord Citation2012), which means that Årjäng is included in the local and regional labour markets of Oslo (Gottfridsson Citation2011).

Methods

Our empirical results were derived from three different surveys and official statistics of commuting retrieved from national and regional databases (i.e. StatNord and Statistics Sweden). The three surveys, for which details are listed in , were:

‘Gränspendling Norge 2012’ – Statistics Sweden’s survey of all cross-border commuters in the municipalities of Årjäng, Eda, and Torsby, conducted in 2012 (report published by Statistics Sweden Citation2012)

‘SOM Värmland 2014’ – a survey of intranational commuting both from and within Värmland, conducted between September 2014 and February 2015 by the SOM Institute (report published by Norell & Nilsson Citation2016)

Värmland County Council’s survey of intranational and cross-border commuting in Värmland, conducted in 2008 as part of the Swedish national life and health survey, Liv & Hälsa (report published by Kalander Blomqvist et al. Citation2008).

Table 2. Surveys included in the study

Survey of all cross-border commuters in the municipalities of Årjäng, Eda, and Torsby

Statistics Sweden’s survey of cross-border commuting, conducted in 2012, encompassed all cross-border commuters in the municipalities of Torsby, Eda, and Årjäng (Gottfridsson et al. Citation2012). Cross-border commuters were defined as all inhabitants with a taxable income from Norway of SEK 50,000 (c. EUR 4840) or more in 2009. The response rate was 43%, which means that the non-response rate was high. High non-response rates are a common problem in quantitative studies and the possible reasons for them need to be considered. In our case, the characteristics of the cross-border commuting might have been part of the explanation. The non-respondents were mainly in the age range 20–34 years. Previous studies have shown difficulties in accessing weekly commuters, but the commuters did not tend to be overrepresented in younger age groups. Öhman & Lindgren (Citation2003) found that weekly commuters often were over 35 years of age, with an average age of 44 years and peaks at 35 years and 55 years. Thus, the non-response rate in our study might have been affected by other factors. One common explanation for problems in accessing commuters is that younger people in general are less willing to participate in surveys than are people in older age groups (Christianson & Härnqvist Citation1980). Moreover, the large share of young Swedes working in the service sector in Norway may blur the image of weekly commuters as typically in the older age groups (Hanaeus Citation2013; Möller et al. Citation2014; Tolgensbakk Citation2015).

Intranational commuting from and within the county of Värmland

The SOM Institute survey of intranational commuting both from and within Värmland was conducted between September 2014 and February 2015as a collaboration between the SOM InstituteFootnote1 at Gothenburg University and Karlstad University (Department of Political, Historical, Religious and Cultural Studies and the Department of Geography Media and Communication). The study encompassed a random sample of 3000 people between the ages of 16 years and 85 years who were resident in Värmland. The survey included 73 questions in various categories, including media, politics, service, activities, and work life. Commuting was covered by three questions and commuters were defined as people who crossed a municipal border for work or to study, either within Värmland County or in other parts of Sweden. The response rate was 51% in general, but varied according sex and age group (Bové Citation2016). Two different groups of commuters were defined: those who crossed a municipal border within Sweden (N = 222), and those who commuted to Norway at the time of the survey (N = 20) (Gottfridsson & Möller Citation2016). Due to the sparse number of respondents, cross-border commuters are not represented in the survey results. The non-respondents were mainly in the age range 18–34 years. Fewer men than women answered the questionnaire, and the response rate was also lower among respondents with lower education levels compared with respondents with higher education levels (Bové Citation2016). Calibration was used to compensate for the high non-response rate (Särndal & Lundström Citation2005).

Intranational and cross-border commuting in Värmland as part of the Swedish national life and health survey, Liv & Hälsa

The part of the Swedish national life and health survey, Liv & Hälsa, conducted in Värmland in 2008 covered health, living habits, and living conditions (Kalander Blomqvist et al. Citation2008). The national life and health survey was conducted in collaboration with several other counties in Sweden, namely Uppsala, Sörmland, Västmanland, and Örebro (A). The part of the study conducted in Värmland covered a large sample of individuals, 11,900 from a total population of c.211,000 inhabitants (Kalander Blomqvist et al. Citation2008). The study comprised commuters in Värmland (N = 1256), including cross-border commuters (N = 131). The participants, who were in the age range 18–84 years, answered a number of questions about their health, lifestyle, and life situation in a postal questionnaire.

To visualise the cross-border commuting flows from Torsby, Eda, and Årjäng to Norway, a spatial analysis was performed based on Statistics Sweden’s cross-border survey in 2012. Commuting flows and distances were illustrated by linking the commuters’ place of residence in Sweden (based on NYKO areasFootnote2) and their workplace municipality in Norway. Two maps were developed, both consisting of two layers: one map layer made in ArcMap showing municipalities and NYKO areas, and one line layer showing commuting flows made using NodeXL software for Microsoft Excel. The thickness of the arrows represented the number of commuters. The method of visualising commuting flows was to some extent similar to the method used by Ho et al. (Citation2011) to visualise spatial data.

Results

In this section, we compare intranational and cross-border commuting with respect to frequency of commuting, means of transport, motives for commuting, and commuting time and distance. We highlight some significant characteristics of the cross-border commuting that distinguished it from other types of commuting. Unless otherwise stated, all results for cross-border commuting were derived from the dedicated cross-border commuting study conducted by Statistics Sweden, whereas the characteristics of intranational commuters were sourced from the SOM study and the regional results were sourced from the Liv & Hälsa survey.

Commuting frequency

Although there are some differences between the results of the three studies with respect to frequency, the main picture is clear: weekly commuting was much more common among cross-border commuters than among other commuters. This result was not unexpected because in many cases cross-border commuting represents longer travel distances than other types of commuting. Among intranational commuters, the share of weekly commuting was 10–15%, while the corresponding share was 60% among all cross-border commuters in Värmland. Among cross-border commuters in the three case municipalities, the share of weekly commuting was significantly lower (31%), but double the share of intranational commuters (). The lower share was due to the shorter distance from the border, which allowed for daily commuting.

Table 3. Cross-border and intranational commuters’ frequency of commuting, for the county of Värmland, 2008–2009 (%)

The main pattern of intranational commuting was daily commuting, while the main pattern of cross-border commuting was weekly commuting. The distribution of daily cross-border commuting is interesting because the commuting pattern of cross-border commuters who were resident near the border was more like that of intranational commuters than of other cross-border commuters in Värmland. This is indicated by the share of daily commuting, which was as high as 69% in Värmland compared with 39% for all cross-border commuting. Additionally, the cross-border commuters did more frequent ‘short-week’ (i.e. 2–4 days per week) daily commutes than did other types of commuters, which indicates that they engaged in part-time work to a greater extent than did the other commuters.

Means of transport

Many commuters commuted by private car, especially residents who lived outside towns and cities, and where public transport was usually not as easily accessible or well functioning as in more urban areas. The county of Värmland is rather peripheral from a Swedish perspective, and hence the use of private cars for commuting has been high (73% in the period 2008–2009) (). More recent national surveys have shown that the average of private cars for commuting is lower (60%) (Trafikanalys Citation2015).

Table 4. Cross-border and intranational commuters by means of transport, for the county of Värmland, 2008–2009 (%)

Cross-border commuters from the border municipalities commute almost exclusively by private car, whereas a small portion of cross-border commuters always used public transport in contrast to intranational commuters (). Remarkably, in the cross-border survey, although 18% stated they had access to public transport, only 3% used it frequently (Statistics Sweden Citation2012). The main reason why public transport was not used was that the public transport travel times did not coincide with the commuters’ work hours. In this respect, the border functioned as a barrier, as national transport systems tended to be directed towards central regions in the respective countries, often regardless of actual distances to towns and other places across the border.

Commuting time

Cross-border commuters generally had significantly longer travel times than did other commuters. Cross-border and intranational commuters showed diametrically opposed patterns regarding commuting time. While approximately half of the cross-border commuters travelled for more than 60 minutes in one direction to work, just under half of the intranational commuters travelled slightly less than 30 minutes (). The mean travel time for cross-border commuters in one direction between their place of residence and their workplace was twice that for intranational commuters: 89 minutes and 43 minutes respectively (). The time difference was mainly due to the dominance of weekly commuting among cross-border commuters. There were no differences in commuting times between the two groups with regard to daily commuting.

Table 5. Cross-border and intranational commuters by commuting time (one way), for the county of Värmland, 2008–2009

Commuting distance

The lack of difference between cross-border commuters’ and intranational commuters’ daily commuting time was readily explained when we mapped the geographical distribution of cross-border commuters. Cross-border commuters from Torsby, Eda, and Årjäng to Norway clearly fell into three separate groups ():

commuters who travelled to a place near the border or to the nearest place on the Norwegian side of the border

commuters who travelled to the Oslo region

commuters who travelled to various places elsewhere in Norway.

Table 6. Travel time between the Swedish border municipalities and the most frequent cross-border commuting destinations, one way by private car

highlights some degree of polarisation in cross-border commuting in two distinct groups: commuting to the nearest community of some size across the border or commuting to the capital area, which has an extensive and differentiated labour market. The starting points of the lines in represent NYKO areas from which there were five or more cross-border commuters, and the thickness of the lines indicates the extent of commuting. From , it is evident that cross-border commuting to the Oslo region was attractive for residents throughout Eda, Årjäng, and Torsby, and not just the communities or the places with best infrastructure and nearest to the border.

Motives for commuting

Higher wages were a significant motive for commuting, both for intranational commuters and for cross-border commuters. We found a significant difference in the importance of this motive between our two groups of commuters: while it was one of a number of motives to commute intranationally, it was clearly the main reason for the cross-border commuters (). In the cross-border survey, the open-ended questions relating to the most positive aspects of commuting to Norway revealed that higher Norwegian wages than those for similar jobs in Sweden were important pull factors for commuting across the border. The wages were described as a major contribution to improved personal and household income, which together with lower Norwegian taxes contributed to economic advantages.

Table 7. Motives for commuting among cross-border and intranational commuters, for the county of Värmland, 2008–2009 (%)

By far the main motive for intranational commuters in general was their opportunity to remain resident in their home municipalities. This was not a pre-coded alternative in the cross-border commuting survey. However, when the respondents in the cross-border survey reflected on their work in Norway in their responses to the open-ended questions, they identified that individual and place-related factors for working in Norway related to their wish to remain in their home community.

Another significant difference between the cross-border and within-border commuters was the relative importance of career motives. This was clear from the intranational commuters’ responses when they selected career as their main reason for commuting, but was almost irrelevant among cross-border commuters. The cross-border commuters seemed to a much larger extent to view crossing the border for work as a necessity to obtain higher paid work (). However, the responses to the open-ended questions in the cross-border survey revealed that the working conditions in Norway were important too, and thus highlighted social and cultural pull factors for commuting. The Norwegian work environment was described as more attractive than the work environment in Sweden due to better and shorter working hours, less stressful workplaces, good management and colleagues, better social welfare, better career opportunities, and a greater flexibility at work. Some respondents emphasised how working in Norway had enabled them to spend more time with their families and everyday life at home since they could choose to work part-time due to the higher wages, and one respondent claimed ‘More time with the kids, just a calmer everyday life. A richer life for the whole family in terms of time’. This adaption to everyday life is reflected in the share of ‘short-week’ daily cross-border commuting in .

Furthermore, commuting to work on the other side of the border was described in the cross-border survey as the opportunity to acquire different cultural values, and to learn new and interesting things through work in another cultural setting while also being appreciated for their labour. One respondent stated: ‘People at large are more easy going and easier to deal with. Better pay, but the working conditions are the most important.’ Additionally, respondents in the cross-border survey described Swedish labour as having a good reputation in Norway.

The findings presented in this subsection are in accordance with those of other researchers that indicated that wages and working conditions, real estate markets, and personal and/or family relations were the main motives for cross-border commuting in the Danish–German border region (Hansen & Nahrstedt Citation2000).

Attitudes towards commuting

In addition to the pull factors for commuting discussed in the preceding subsection, there is a question of what were the respondents’ attitudes towards their commuting. Commuting in general involves spending a lot of time in transit and away from family and the local community. Hence, almost 80% of intranational commuters claimed that they would consider alternative work in Sweden if they were given the possibility. However, only c.50% of the cross-border commuters said they would return to work in their Swedish home community if there were adequate job opportunities. This was a lower share than expected and, remarkably, many of those commuters were rather determined to continue commuting over the border, even if the opportunity to secure a suitable job inland arose (). The background to why cross-border commuters were less likely to consider alternative work options locally might have been related to the social and economic motives discussed in the preceding section. In the cross-border survey, one of the questions was ‘To what degree do you enjoy your work in Norway?’, to which 85% of the cross-border commuters reported that their degree of job satisfaction was ‘very good’ (51%) or ‘good’ (34%), and only 3% reported ‘bad/very bad’. When seen in the context of their motives for commuting, and their anticipation of a future work location, this finding indicates that their commuting was very much a preferred arrangement over all options they had evaluated, and thus seems a rather permanent adaption to work.

Table 8. Cross-border and intranational commuters’ desirability of alternative work in Sweden, for the county of Värmland, 2008–2009 (%)

The responses to open-ended questions in the cross-border survey provided insights into potential ‘push factors’ for leaving work in Norway though the given examples of negative aspects of commuting across the border. According to the respondents, one pronounced negative factor related to bureaucracy, ‘paper hassle’, and border regulations, due to differences in tax systems and social insurance schemes. Another respondent claimed ‘If you become unemployed in Norway, it takes a long time before you can come back to Swedish unemployment benefits and receive money.’ This problem is rooted in the two countries’ different tax and social security systems. The respondent emphasised that the authorities themselves, who were responsible for taxes and social insurance (including sick leave, parental leave, and unemployment benefits), were not aware of the guidelines and regulations. Another respondent stated that ‘no authorities know to a 100% what rules to apply’, while yet another wrote ‘border barriers must be removed.’ The respondents expressed feeling quite stressed due to their constant worry about becoming sick or unemployed. Moreover, some respondents (22%) definitively wanted to stop commuting to Norway (). In response to the question about the most negative aspects of working in Norway, a small percentage of the respondents selected the response option ‘Nothing’ (almost 6%, 73 out of 1334).

In summary, our material shows that cross-border commuters should not be treated as a homogenous group. We have identified both differences and similarities between cross-border and intranational commuters as well as within the studied group of cross-border commuters. In the latter case, the differences related to their place of residence and distance from the border. Cross-border commuters who lived near the border shared some of the characteristics of intranational commuters, including frequency of commuting, commuting distance, and time spent on work-related travels. However, the cross-border commuters differed from intranational commuters in terms of their attitudes towards and motives for commuting. By contrast, previous research has shown that intranational commuters prefer to stop commuting if possible (Olsson & Gottfridsson Citation2009).

Our study shows that cross-border commuting was considered a long-term and permanent solution, even if the commuters could have found a suitable job in Sweden. Although we identified push factors for cross-border commuting, such as difficulties in finding work at the place of residence, few respondents claimed that they wanted to stop commuting to Norway. This finding is supported by previous studies that as many as 79% of the respondents stated that commuting across the border was a long-term voluntarily chosen lifestyle (Olsson & Gottfridsson Citation2011). Thus, commuting had become a way of life, and an earlier study from Värmland revealed that living on the Swedish side of the border and working in Norway was a lifestyle in which the positive outcomes outweighed the negative ones, and generated stronger pull factors than the push factors (Gottfridsson et al. Citation2012).

Commuting and spatial integration

Cross-border commuting is only one form of work-related mobility in the Swedish–Norwegian border region. Other forms of mobility include migration, tourism, and cross-border shopping, which together contribute to the spatial integration process. Ericsson et al. (Citation2012b) claim that the cross-border mobility in the Swedish–Norwegian border region is characterised by a permanent state of transiency, which in turn governs and affects the future development of the border region. The transiency means that consumption and production processes in the region are dependent on the ongoing cross-border mobility and need to adjust to it (Ericsson et al. Citation2012b).

Norwegian migrants constitute a significant share of the local population on the Swedish side of the border. In Eda Municipality in 2011, 17.8% of the inhabitants were Norwegian citizens, and the corresponding share in Årjäng was 11% (Ørbeck & Gløtvold-Solbu Citation2012). However, on the Norwegian side of the border, the share of Swedes was significantly less, and represented only between 2% and 5% of the total population in the Norwegian municipalities with most Swedish immigration (Ørbeck & Gløtvold-Solbu Citation2012). Thus, Swedish migration into Norway seems to be concentrated in urban areas and established Norwegian tourism destinations; possible explanations are discussed by Ørbeck & Gløtvold-Solbu (Citation2012) and include differences in wages, which are considerably higher in Norway, and the costs of living, which are lower in Sweden. The employment rate in the Norwegian labour market has experienced an upward trend since the mid-1990s, while the employment rate in Sweden has not changed since the 1990s (Ørbeck & Gløtvold-Solbu Citation2012). Furthermore, the share of Norwegian citizens in Swedish municipalities is reflected in the results of our study: of all cross-border commuters in Eda, Årjäng, and Torsby, 31% were Norwegian, and c.40% of them still held the same job in Norway as when they had moved to Sweden.

The Norwegian presence in Swedish border communities is also evident from leisure-related mobility and consumption-related mobility, including tourism, second-home ownership, and cross-border shopping. Norway is the main foreign tourism market for Sweden in general and for Värmland in particular, representing 50% of the total number of guest nights (Region Värmland Citation2015). In terms of cross-border shopping, the growth has been particularly strong in Värmland County and the shopping centres in Charlottenberg in Eda Municipality and Töcksfors in Årjäng Municipality (B) (Region Värmland Citation2015). These two cross-border shopping destinations represent c.20–25% in terms of the total value of cross-border shopping in Norway (Statistics Norway Citation2018). Norwegian ownership of second homes in Sweden has increased by 360% in the present millennium (Ericsson et al. Citation2012a). In 2015, 11,500 second homes in Sweden were owned by Norwegians, of which 32% (3700) were in Värmland, and 14% of all second homes in Värmland were owned by Norwegians (Statistics Sweden Citation2016). In 2010, respectively 18% and 21% of second homes in Årjäng and Eda were owned by Norwegians (Ericsson et al. Citation2012a). In 2016, Torsby was one of five municipalities in Sweden where more than 1000 second homes were owned by foreigners (Statistics Sweden Citation2016).

The mechanisms facilitating leisure-related and consumption-related mobility flows are generally the same, namely higher wages in Norway and lower property prices and living costs in Sweden. Property costs in the border area in Värmland are currently suffering from a sparse regional and national market, while the distance from an urban market in the Oslo region is well within reach on a weekend basis, for second-home owners who travel for leisure.

The border as an engine for mobility: spatial integration by specialisation

The different forms of work-related mobility can be linked on a general level to Sohn’s geo-economic model (Sohn Citation2014) and differential benefits. In a more specific context, they are triggered by the border effect of what Decoville et al. (Citation2013) identify as spatial integration. In our case study region, integration by specialisation has become pronounced and is reflected in a win-win situation on either side of the Swedish–Norwegian border, with both sides specialising and complementing each other in terms of spatial consumption and production patterns. This integration thus benefits both sides of the border, contrary to most situations in which strong economic interactions sustain an unequal process of development whereby one side of the border benefits more than the other. Our findings relate to Sohn’s idea of the border as a resource for integration (Sohn Citation2014).

However, we suggest that the border also constitutes an engine for mobility and economic activities. Empirically, this is evident from flows of people and money in opposite directions: work-related mobilities from Sweden to Norway, represented by Swedes commuting to Norwegian workplaces, and Norwegians’ migrations to Värmland, while continuing to work in Norway. Leisure-related mobilities are mainly from Norway to Sweden, and characterised by Norwegians buying consumer goods, property, and tourism services in Sweden because the prices are lower. These flows in opposite directions across the border are interlinked and interdependent. The metaphor of the border as an engine also requires ‘fuel’, which is represented by differences in terms of wage levels, costs of living, and fluctuations in the Swedish and Norwegian labour markets. When the Norwegian economy is flourishing, wages and costs of living are high, while the situation is quite the opposite in Sweden. Thus, working in Norway and living in Sweden has become a winning formula for individuals on both sides of the border. Living in a border region gives easy access to the Norwegian labour market for daily commuters, which is impossible from places farther away in Sweden.

The pull factors are lubricated by shared cultural values and similar languages at an individual level but are counteracted by systemic differences in politics, rules, and regulations (e.g. different tax and social security systems), which creates ‘a paper hassle’. The mobility flows also generate additional regional effects, whereby Swedish border regions profit from urban and extensive economic markets in densely populated areas in adjacent Norwegian border regions. In this case, ideas of regional enlargement and visions of attracting new inhabitants and businesses continue to grow and develop. Although both border regions benefit from this integration, it also creates a concentration of economic activities in the urban regions around Oslo, while more peripheral areas remain ‘dormitory areas’, as discussed by Decoville et al. (Citation2013).

As an engine, the border is not static, and the generated mobility flows may fluctuate. As history has shown, the balance is fragile and vulnerable to structural changes in socio-economic conditions in either Norway or Sweden. Therefore, the sustainability of such a system remains crucial, considering the effects on Swedish individuals and their families who rely and depend on their income from work in Norway. One key factor in this context may be the fact that, unlike Norway, Sweden is a member of the EU. Thus, the differences in terms of wage levels and costs of living serve as the fuel for the border engine. Consequently, living in more remote parts of the border region may provide access to a labour market with better opportunities compared with other, more urbanised regions of Sweden. Thus, labelling border areas as ‘remote’ or ‘peripheral’ areas may be misleading in terms of their potential for regional development. Additionally, the processes of spatial integration of border regions include the need to adapt to a permanent ‘transient’ mobility, including planning and governing for local communities, which may bring challenges for the development of transport, housing, and other services to serve a more mobile population and short-term visitors.

Conclusions

In this article, we have analysed differences and similarities between cross-border and intranational commuting on a regional and aggregated level. Our study results indicate that cross-border commuting shares some common features with intranational commuting with respect to how the frequency of work-related mobility, particularly daily and weekly commuting, is dependent on distance. Cross-border commuters living close to the Swedish–Norwegian border have similar commuting patterns to intranational commuters within Värmland County, including a higher share of daily commuters.

However, the cross-border commuting included significant differences from the intranational commuting. First, the results indicate a difference in motives for cross-border commuting, which was mainly driven by economic and sociocultural motives, in contrast to intranational commuting, for which career-oriented pull factors for work-related travel were common. The differences in motives included national differences in terms of work culture and working conditions as important aspects of cross-border commuting. Second, the difference in motives for cross-border commuting was characterised by time-consuming, work-related travel over longer distances compared with intranational commuting. This was evident from a higher share of weekly commuting and that just over half of the cross-border commuters spent more than 60 minutes commuting in one direction for work. The share of weekly commuting among cross-border commuters from Värmland in general was higher than among commuters within the county of Värmland. By contrast, residents living close to the border had access to more favourable labour markets that were well within daily commuting distance, and hence most cross-border commuters in the border municipalities travelled to Norway daily. With regard to daily commuting, travel times were almost the same from crossing the border for work or commuting within Sweden, Third, cross-border commuting in the Swedish–Norwegian border region relied on transport by car rather than public means of transportation, due to the challenges of combining public transport with working hours in Norway.

Our results show that commuting as well as other forms of cross-border mobility, such as cross-border shopping, tourism, and migration across the Swedish–Norwegian border, contribute to spatial integration, known as integration by specialisation. Cross-border commuting is mainly one-directional, from Sweden to Norway, while leisure mobility and migration tend to go in the opposite direction. In this case, a win-win situation can be distinguished, in which the border serves as both a resource and an engine for cross-border integration, mobility, and economic activities.

Directions for future research

Based on our results, two lines of further research can be distinguished. First, since our study mainly analysed the patterns and mechanisms for cross-border commuting, there is a need to investigate also cross-border commuters’ own motivations, and the obstacles and inconvenience that may complicate a situation that is otherwise beneficial for both countries. In this context, the strategies and conditions for cross-border commuting could be explored in more depth, and variables such as gender, family situations, and nationality could be assessed. Second, the transforming and mobile labour market in the cross-border region requires additional studies to gain knowledge of the effects on cross-border commuting due to ongoing economic fluctuations in the Norwegian and Swedish economies.

Acknowledgements

This article is partly based on survey data generated by the SOM Institute, Gothenburg University, Sweden, in collaboration with researchers at Karlstad University, Sweden, and therefore P.O. Norell and Lennart Nilsson, the editors of the SOM study that was published in 2016 (Norell & Nilsson Citation2016), are thanked for making the data accessible to us. We also thank Østlandsforskning, Norway, and Karlstad University for financing the writing of the article, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their useful and valued comments.

ORCID

Cecilia Möller http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1918-6701

Eva Alfredsson-Olsson http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1532-8474

Notes

1 The SOM Institute is an independent survey research organisation at the University of Gothenburg. The SOM Institute has always focused on Swedes’ habits, behaviour, opinions, and values with respect to society, politics, and media (SOM institute Citation2016).

2 Nyckelkodsystemet (NYKO) is a Swedish geographical system for linking statistical information to smaller geographical entities than the municipalities, based on the cadastre and population statistics. Each NYKO area is given a unique code by Statistics Sweden (Statistiska centralbyrån) (Statistics Sweden Citationn.d.).

References

- Berger, S., Forsberg, G. & Ørbeck, M. 2007. Inre Skandinavien – en gränsregion under omvandling. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Bové, J. 2016. Den värmländska SOM-undersökningen 2014. Norell, P.O. & Nilsson, L. (eds.) Värmländska utmaningar: Politik, ekonomi, samhälle, kultur, medier, 527–540. Bohus: Karlstad University Press.

- Buch, T., Schmidt, T.D. & Niebuhr, A. 2009. Cross-border commuting in the Danish-German border region – integration, institutions and cross-border interaction. Journal of Borderlands Studies 24, 38–54. doi: 10.1080/08865655.2009.9695726

- Christianson, U. & Härnqvist, K. 1980. LING-projektens enkät 1980. Genomförande och bortfallsanalyser. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/26983/1/gupea_2077_26983_1.pdf (accessed June 2018).

- Cooper, A. 2015. Where are Europe’s new borders? Ontology, methodology and framing. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 23, 447–458. doi: 10.1080/14782804.2015.1101266

- Cooper, A., Perkins, C. & Rumford, C. 2014. The vernacularization of borders. Jones, R. & Johnson, C. (eds.) Placing the Border in Everyday Life, 15–32. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Decoville, A., Durand, F., Sohn, C. & Walther, O. 2013. Comparing cross-border metropolitan integration in Europe: Towards a functional typology. Journal of Borderlands Studies 28, 221–237. doi: 10.1080/08865655.2013.854654

- Durand, F. 2015. Theoretical framework of the cross-border space production – The case of the Eurometropolis Lille–Kortrijk–Tournai. Journal of Borderlands Studies 30, 309.

- Dürrschmidt, J. 2007. Sociology for a Changing World: Globalisation, Modernity and Social Change: Hotspots of Transition. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ericsson, B., Overvåg, K. & Hagen, S.E. 2012a. Å bo flere steder – fritidsboligeiere i Indre Skandinavia. Olsson, E., Hauge, A. & Ericsson, B. (eds.) På gränsen: Interaktion, attraktivitet och globaliseirng i Inre Skandinavien, 149–168. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Ericsson, B., Hauge, A. & Olsson, E. 2012b. Indre Skandinavia – hva nå? Olsson, E., Hauge, A. & Ericsson, B. (eds.) På gränsen: Interaktion, attraktivitet och globaliseirng i Inre Skandinavien, 149–168. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Frändberg, L., Vilhelmson, B. & Thulin, E. 2005. Rörlighetens omvandling: om resor och virtuell kommunikation – mönster, drivkrafter, gränser. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Friberg, T. 2008. Det uppsplittrade rummet: Regionförstoring i ett genusperspektiv. Andersson, F., Ek, R. & Molina, I. (eds.) Regionalpolitikens geografi – Regional tillväxt i teori och praktik, 257–284. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Gil Solá, A. 2013. På väg mot jämställda arbetsresor? Vardagens mobilitet i förändring och förhandling. PhD thesis. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, School of Business, Economics and Law.

- Gottfridsson, H.O. 2007. Färdmedelsvalets komplexa förutsättningar: En studie av arbetspendling i småbarnshushåll med Kils kommun som exempel. PhD thesis. Karlstad: Karlstad University.

- Gottfridsson, H.O. 2011. Gräset är grönare på andra sidan – att pendla till en arbetsplats i Norge. Olsson, E., Berger, S. & Gottfridsson, H.O. (eds.) Gränslöst liv? En studie av två gränskommuner i Värmland, 39–52. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Gottfridsson, H.O. & Möller, C. 2016. Värmlänningar i rörelse: En studie av värmlänningars vardagsmobilitet. Norell, P.O. & Nilsson, L. (eds.) Värmländska utmaningar: Politik, ekonomi, samhälle, kultur, medier, 361–384. Bohus: Karlstad University Press.

- Gottfridsson, H.O., Olsson, E., Möller, C. & Öjehag, A. 2012. Att gränspendla – samma fast olika. Olsson, E., Hauge, A. & Ericsson, B. (eds.) På gränsen: Interaktion, attraktivitet och globaliseirng i Inre Skandinavien, 93–107. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Gottholmseder, G. & Theurl, E. 2007. Determinants of cross-border commuting: Do cross-border commuters within the household matter? Journal of Borderlands Studies 22, 97–112. doi: 10.1080/08865655.2007.9695679

- Hanaeus, C.-G. 2013. Gränspendlingen från Sverige till Danmark och Norge åren 2001–2008. TemaNord 2013:5551. http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:700978/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accesssed June 2018).

- Hansen, C.L. 2000. Economic, political, and cultural integration in an inner European union border region: The Danish-German border region. Journal of Borderlands Studies 15, 91–118. doi: 10.1080/08865655.2000.9695558

- Hansen, C.L. & Nahrstedt, B. 2000. Cross-border commuting: Research issues and a case study for the Danish–German border region. van der Velde, M. & Van Houtum, H. (eds.) Border, Regions and People, 69–84. London: Pion.

- Ho, Q., Nguyen, H.-P. & Jern, M. 2011. Implementation of a flow map demonstrator for analyzing commuting and migration flow statistics data. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 157, 157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.07.029

- Huber, P. & Nowotny, K. 2013. Moving across borders: Who is willing to migrate or to commute? Regional Studies 47, 1462–1481. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2011.624509

- Kalander Blomqvist, M., Jansson, S. & Starrin, B. (eds.) 2008. Värmlänningarnas Liv & Hälsa 2008. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Laakso, S., Kostiainen, E., Kalvet, T. & Velström, R. 2013. Economic Flows between Helsinki-Uusimaa and Tallinn-Harju Regions. http://www.kaupunkitutkimusta.fi/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Helsinki-Tallinna + talousvirrat.pdf (accesssed June 2018).

- Lundquist, K.-J. & Trippl, M. 2009. Towards Cross-border Innovation Spaces: A Theoretical Analysis and Empirical Comparison of the Öresund Region and the Centrope Area. SRE–Discussion 2009/05. Vienna: Institut für Regional- und Umweltwirtschaft, WU Vienna University of Economics and Business.

- Martinez, O. 1994. The dynamics of border interactions. Schoefield, C.H. (ed.) Global Boundaries, 8–14. World Boundary Series Vol. 1. London: Routledge.

- Mathä, T. & Wintr, L. 2009. Commuting flows across bordering regions: A note. Applied Economics Letters 16, 735–738. doi: 10.1080/13504850701221857

- Medeiros, E. 2014. Terrirorial cohesion trends in Inner Scandinavia: The role of cross-border cooperation – INTERREG-A 1994–2010. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 68, 310–317. doi: 10.1080/00291951.2014.960949

- Möller, C., Olsson, E. & Öjehag, A. 2012. ‘Harryland’? – Gränshandel i tre värmländska kommuner. Olsson, E., Hauge, A. & Ericsson, B. (eds.) På gränsen: Interaktion, attraktivitet och globaliseirng i Inre Skandinavien, 77–92. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Möller, C., Ericsson, B. & Overvåg, K. 2014. Seasonal workers in Swedish and Norwegian ski resorts – potential in-migrants? Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 14, 385–402. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2014.968365

- Nerb, G., Hitzelsberger, F., Woidich, A., Pommer, S., Hemmer, S. & Heczko, P. 2009. Scientific Report on the Mobility of Cross-border Workers within the EU-27/EEA/EFTA Countries. http://www.google.se/url?sa = t&rct = j&q=&esrc = s&source = web&cd = 3&cad = rja&uact = 8&ved = 0ahUKEwjC1cHV4LnZAhXIkSwKHQjNClUQFgg1MAI&url = http%3A%2F%2Fec.europa.eu%2Fsocial%2FBlobServlet%3FdocId%3D3459%26langId%3Den&usg = AOvVaw32f8OrpOqg2Rr86spsusv3 (accesssed June 2018).

- Norell, P.O. & Nilsson, L. (eds.) 2016. Värmländska utmaningar: Politik, ekonomi, samhälle, kultur, medier. Bohus: Karlstad University Press.

- Öhman, M. & Lindgren, U. 2003. Who is the long-distance commuter? Patterns and driving forces in Sweden. Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography Document 243.

- Olsson, E. & Gottfridsson, H.O. 2009. Pendling – acceptabelt och lönsamt men helst inte. Kalander Blomqvist, M., Jansson, S. & Starrin, B. (eds.) Värmlänningarnas Liv & Hälsa 2008, 38–51. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Olsson, E. & Gottfridsson, H.O. 2011. Gräset är grönare på andra sidan – att pendla till en arbetsplats i Norge. Olsson, E., Berger, S. & Gottfridsson, H.O. Gränslöst liv? En studie av två gränskommuner i Värmland, 35–48. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Olsson, E., Berger, S. & Gottfridsson, H.O. 2011. Gränslöst liv? En studie av två gränskommuner i Värmland. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Olsson, E., Hauge, A. & Ericsson, B. 2012. På gränsen: Interaktion, attraktivitet och globalisering i inre Skandinavien. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Ørbeck, M. & Gløtvold-Solbu, K. 2012. Svensker på jobb i Norge. Olsson, E., Hauge, A. & Ericsson, B. (eds.) På gränsen: Interaktion, attraktivitet och globaliseirng i Inre Skandinavien, 29–44. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Paasi, A. & Prokkola, E.K. 2008. Territorial dynamics, cross-border work and everyday life in the Finnish-Swedish border area. Space and Polity 12, 13–29. doi: 10.1080/13562570801969366

- Region Värmland. 2013. Relationen Sverige-Norge och Värmlands roll. Region Värmland raport nr. 14. http://www.regionvarmland.se/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/rapport14_sverige-norge.pdf (accessed June 2018).

- Region Värmland. 2015. Norge – Sveriges viktigaste grannland. http://www.regionvarmland.se/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Rapport-Nr.17-Norge-%E2%80%93-Sveriges-viktigaste-grannland-2015-.pdf (accessed June 2018).

- Sandow, E. 2008. Commuting behaviour in sparsely populated areas: Evidence from northern Sweden. Journal of Transport Geography 16, 14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2007.04.004

- Sandow, E. 2011. On the Road: Social Aspects of Commuting Long Distances to Work. PhD thesis. Umeå: Umeå University.

- Sandow, E. & Westin, K. 2010. The persevering commuter – duration of long-distance commuting. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 44, 433–445.

- Särndal, C.-E. & Lundström, S. 2005. Estimation in Surveys with Nonresponse. Chichester: John Wiley.

- Scholten, C. & Jönsson, S. 2010. Påbjuden valfrihet? Om långpendlares och arbetsgivares förhållningssätt till regionförstoringens effekter. Växjö: Linneaus University, Department of Social Sciences.

- Schwab, O. & Toepel, K. 2006. Together apart? Stocktaking of the process of labour market integration in the border region between Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic. Zeitschrift für Arbeitsmarktforschung 39, 77–93.

- Sohn, C. 2014. Modelling cross-border integration: The role of borders as a resource. Geopolitics 19, 587–608. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2014.913029

- Sohn, C. & Licheron, J. 2017. The multiple effects of borders on metropolitan functions in Europe. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1410537 (accessed June 2018).

- Som Institute. 2016. About the SOM Institute. http://som.gu.se/som_institute/about-som (accessed June 2017).

- Statistics Norway. 2018. Grensehandel. https://www.ssb.no/varehandel-og-tjenesteyting/statistikker/grensehandel (accessed May 2018).

- Statistics Sweden. 2012. Registerbaserad arbetsmarknadsstatistik 2011. http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Publiceringskalender/Visa-detaljerad-information/?publobjid = 16790 (accessed June 2018).

- Statistics Sweden. 2016. Statistiknyhet från SCB: Det norska ägandet av svenska fritidshus nu störst. https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/boende-byggande-och-bebyggelse/fastighetstaxeringar/fastighetstaxeringar/pong/statistiknyhet/utlandskt-agande-och-utlandssvenskars-agande-av-fritidshus-i-sverige-2015/ (accessed May 2018).

- Statistics Sweden. n.d. NYKO-delområde: Allmänt om nyckelkodning. https://www.scb.se/contentassets/4d5516f7c4504a669fdf242136eacfee/meromnyko.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- StatNord. 2012. Nordisk gränsregional statistikdatabas, StaNord. http://www.grs.scb.se/ (accessed June 2018).

- Svensson, S. & Öjehag, A. 2012. Politik bortom gränsen: globala trender och lokala realiteter. Olsson, E., Hauge, A. & Ericsson, B. (eds.) På gränsen: Interaktion, attraktivitet och globaliseirng i Inre Skandinavien, 269–286. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Tolgensbakk, I. 2015. Partysvensker: Go hard! En narratologisk studie av unge svenske arbeidsmigranters nærvær i Oslo. PhD thesis. Oslo: Oslo University.

- Tóth, G., Kincses, Á. & Nagy, Z. 2014. The changing economic spatial structure of Europe. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 68, 301–309. doi: 10.1080/00291951.2014.963665

- Trafikanalys. 2015. RVU Sverige 2011–2014: Den nationella resvaneundersökningen. Statistik 2015:10. https://www.trafa.se/globalassets/statistik/resvanor/2009-2015/rvu-sverige-2011-2014.pdf (accessed June 2018).

- Uteng, T.P. & Cresswell, T. 2008. Gendered Mobilities. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Van Houtum, H. & van der Velde, M. 2004. The power of cross-border labour market immobility. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 95, 100–107. doi: 10.1111/j.0040-747X.2004.00296.x

- Vilhelmson, B. 2005. Urbanisation and everyday mobility: Long-term changes of travel in urban areas of Sweden. Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography 302. https://journals.openedition.org/cybergeo/3536 (accessed June 2018).

- Vilhelmson, B. 2014. Transport geography in Sweden. Journal of Transport Geography 39, 246–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.06.016