ABSTRACT

The purpose of the article is to explore the relationship between place-making and social creativity. It is grounded in a single case study and an analytical generalization approach to the study of two projects in the town of Vardø, Norway: Vardø Restored and Biotope. Empirical data are presented as thematic stories in becoming, which are discussed using actor–network theory (ANT) and meshwork-inspired analysis. Social creativity is understood as inhabitants’ ability to meet new challenges with creativity. Place-making is understood in terms of place-specific creative and regenerative processes, with a focus on the role of community entrepreneurs and creative community arenas outside the formal planning system. Important findings suggest that social creativity emerges from community activities, in which multiple individuals and actors play important roles. Through these processes, entrepreneurs become community entrepreneurs when their collective orientations are activated. Individual community entrepreneurs can take active roles in stimulating social creativity based on their place-specific commitments, broad value-creation perspectives, and sensitivity to place-specific complexities, as well as by gaining credibility. The author concludes that creative community arenas for direct encounters between many different lifelines and actors, future motives, and collective actions are fundamental for the emergence of social creativity and place-making dynamics.

Introduction

In 2009, travellers on the northern tip of the Varanger Peninsula in the county of Finnmark, Norway, were advised not to visit the town of Vardø by people living in the region (). However, during recent years people have started to present this old Arctic town as one of the most interesting places to visit. What caused this positive change?

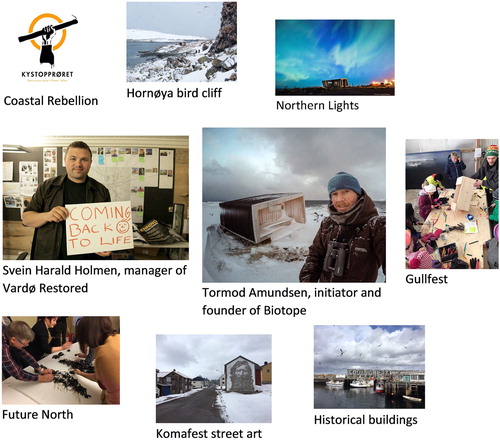

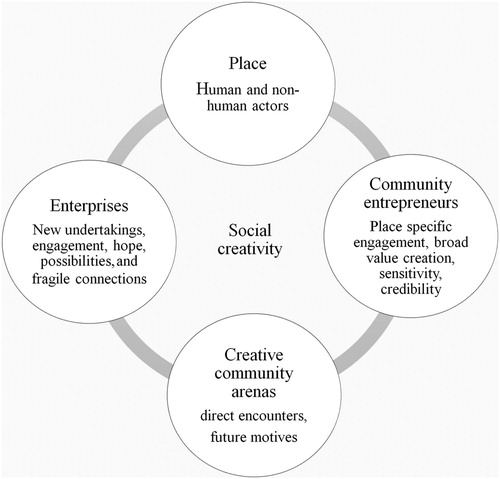

This article focuses on the emergence of social creativity in relation to two place-making projects in Vardø, as part of attempts to understand what has contributed to the positive change: Biotope and Vardø restored. The architecture and tourism concepts developer Biotope has created the birdwatching infrastructure in Vardø and Varanger. Vardø Restored is a non-profit organization working with the restoration of historical buildings, art projects and new development opportunities for house owners. Social creativity can be understood as people’s ability to meet new challenges with creative solutions for the future (Førde Citation2010). To understand relational emergences at the interplay of social creativity and place-making, it is necessary to address both individuals and interactions between actors within a landscape context. The study of the chosen place-making projects within Vardø has laid the groundwork for a conceptual model for understanding relationships between place-making and social creativity as emerging and continual processes rather than merely as results or products. The model is presented and discussed in the penultimate section of the article (i.e. in the section ‘Place-making and emerging social creativity’).

Due to centralization and decline in the fishery industry, the old subarctic town of Vardø lost half of its population between 1980 and 2010. Today, there are 2081 inhabitants (Statistisk sentralbyrå Citation2019), living in an area of 3.7 km2. The decline caused a negative spiral of extensive disintegration of the infrastructure, rampant pessimism and a negative reputation for the town. Vardø exists ‘on hold’, due to a high degree of uncertainty about what the future will bring and is awaiting future resolutions to contemporary problems (Kampevold Larsen & Hemmersam Citation2017). Arctic landscapes are changing fast due to dramatic climate changes and new industrial development forces, which are attracting increased international attention (Kampevold Larsen & Hemmersam Citation2018). However, images of the northern landscapes formed at distance rarely address local community’s livelihoods or desired futures. The northern territories are high up on the Norwegian government’s agenda for foreign and domestic policy affairs, with ideas for fisheries, aquaculture, oil and gas, and tourism as part of the green growth and sustainable development strategies for the future (Utenriksdepartementet, Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementet & Statsministerens kontor Citation2017). In this regard, a need to challenge dominant Western modern capitalist planning and development thinking has been addressed (Løkken & Haggärde Citation2017; Nyseth et al. Citation2017).

The difficult situation for many coastal communities in the north relates to a global discourse on reinventing rural areas (Nyseth & Viken Citation2009). Globally related changes often lead to a range of challenges, such as social fragmentation, identity erosion, and harm to the environment, which together constitute a bundle of radical uncertainties for people living in rural areas, such as coastal places in the north of Norway (Nyseth et al. Citation2017). Many old fishing villages in Norway have undergone transition to holiday villages (Gerrard Citation2009). Tourism is increasing in Norway and is highlighted as an important industry for the future (Meld. St. 19 (Citation2016–2017)). However, studies of European rurality have shown that places have been turned into tourism ‘machines’ and playgrounds for visitors (Butler Citation2011). Terms such as ‘overtourism’ are becoming increasingly prevalent, also in Norway. Hence, there is a fundamental need to address how local development and tourism can work together, thereby challenging the destination discourse (Førde Citation2016).

According to the European Landscape Convention (ELC) (Council of Europe Citation2000), the term landscape means ‘an area, as perceived by local people or visitors, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors’. The ELC highlights the important role of the everyday landscape for quality of daily life and identity. In this article, ‘an area’ is considered in relation to Vardø as a place. The complexity of place is addressed as open and dynamic processes in becoming, whereby people, nature, materiality, sociality, and cultural relations are thrown together (Massey Citation2005). In relation to ELC and the becoming of place, the perspective of community entrepreneurship, understood as processes contributing to community solutions (Borch & Førde Citation2010), can be used in place-making that involves tourism initiatives.

The research strategy for this article was based on an empirical and explorative case study with an analytical generalization approach. The aim was to explore the relationship between place-making praxis and social creativity, and to establish a conceptual framework for studying this relationship. The analytical strategy was empirically driven, wherein the empirical work conducted in Vardø sparked a process of relevant literature selection. In referring back and forth between empirical data and literature, a conceptual understanding of place-making and social creativity evolved as fundamentally relational and dynamic processes. In this article, I seek to answer the following research question: How can the interplay between place-making and social creativity enable vibrant landscapes?

Methods

Vardø was chosen as case due to the particular creative place-making activities unfolding within an island community, where emergent social creativity has been increasingly evident. I collected data using multiple sources of evidence, during five fieldwork sessions of two weeks’ duration each between 2017 and 2018. This involved 15 in-depth interviews and many informal conversations based on a non-representative strategic selection of people and using the snowball method. The interviews lasted 45–90 minutes. However, conversations with key individuals also evolved due to several visits to Vardø. Conversations with fishermen, entrepreneurs, representatives of authorities, activists, artists, and others revolved around topics relating to Vardø as a place, development activities and future orientations. The interviews took place in people’s homes, cafes, offices, at the hotel, and during different events. I used participatory observation as an approach because it allowed me, as a researcher, to participate in processes relevant to my study, such as the birdwatching festival, Gullfest, and Vardø Restored workshops. Inspired by Tim Ingold’s understanding of participatory observation (Ingold Citation2013), I aimed at joining the inhabitants in their search of potential paths for the future. I also used secondary sources such as maps, photographs, videos, documents, web pages, and social media to understand Vardø as a place and to define the place-making activities’ interplay with social creativity. During the fieldwork, certain themes emerged as prominent for social creativity, presented as thematic stories in becoming that relate to Vardø Restored and Biotope.

The individuals cited in the article gave informed consent for their full names to be given. Additionally, they were given the chance to read the text and respond to the content on several occasions. Different themes were discussed with them over a longer period of time, due to several meetings and informal talks with different individuals, such as Svein Harald Holmen and Tormod Amundsen.

Relational place-making literature

Through the fieldwork, the role of two individuals and entrepreneurship projects within Vardø became prominent for understanding the interplay between place-making, social creativity and the enablement of vibrant landscapes. I considered community entrepreneurship and creativity literature relevant for exploring this dynamic interplay. Actor–network theory (ANT) and the concepts of individual lifelines and meshwork (Ingold Citation2011) contributed to shaping the analytical lens for exploring the relational, dynamic and transboundary entrepreneurial processes. A combination of these two relational ontologies is suitable for analysing the world as complex becomings, such as interplay between place-making, social creativity, and potential movements towards virtuous circles and vibrant landscapes (Selman Citation2012). ANT has been used for understanding the broader network of actors involved in actings, allowing for connections to be made between actors across different sectors, on different scales, and in different concepts and periods (Law Citation2008). Ingold’s approach to meshwork contributes to ANT by focusing on individuals within their situated environment and where improvised actings along the lines of movement becomes alive (Ingold Citation2011).

Entrepreneurship and creativity within the landscape

Entrepreneurship concerns processes of change, the ability of actors to perceive opportunities of change, and processes of translating ideas into practice (Jóhannesson Citation2012). Borch & Førde (Citation2010) use the term ‘community entrepreneurship’ to address processes of social and cultural change and value creation that result in new collective solutions for communities. This approach to entrepreneurship relates to an increased awareness of everyday life and community praxis rather than to extraordinary achievements within entrepreneurship literature (Hjort & Bjerke Citation2006). Creativity is an important component of community entrepreneurship (Førde & Ringholm Citation2012) and relates to processes of setting socio-material actors in motion (Kramvig & Førde Citation2015). Lønning (Citation2010) argues that creativity always has to do with being able to see new possibilities for the future based on recombinations of the extant.

Within local development literature, there has been a growing awareness of creativity as experimentation and improvisation, thus challenging ‘creative class’ thinking (Førde & Kramvig Citation2017). Maintaining sensitivity to sociocultural complexities, empowering community processes and co-thinking of futures should be the focus of creative processes within small towns (Nyseth et al. Citation2017). In this respect, social creativity can be used as a term that highlights people’s ability to meet new challenges with creative ideas and solutions (Førde Citation2010). According to Hallam & Ingold (Citation2007), creativity should be seen as improvisation in terms of the movements that give rise to the results rather than innovation in the form of products. Ingold (Citation2013) expands on the understanding of creativity by seeing it as a process of growth whereby the makers become participants who intervene in a world of active materials and add energy to the forces already at work. In response to Ingold, Stuart McLean (Citation2009) proposes a broader understanding of creativity, involving linguistic representations, conceptual formations and transformations, which are capable of adding the articulations from the stories told by humans, detailing the coming-to-being of the material universe.

In order for social creativity to grow, there is a need to provide arenas and meeting places (Førde & Ringholm Citation2012). Community entrepreneurs can play major roles in enabling such spaces, as well as in mobilization processes in times of crisis (Borch & Førde Citation2010). Community entrepreneurs can be recognized as individuals or a combination of different individuals who care greatly for the place where they live. Such individuals can operate as change agents, who are concerned with development and conservation of landscapes as common goods (Haukeland Citation2010). The role of integration actors in contributing to functional local democracy has been highlighted in conjunction with the way they manage informal transboundary processes, build trust and legitimacy, and stimulate group dynamics in both local and regional contexts (Clemetsen & Stokke Citation2018).

Integration actors can be seen in relation to community entrepreneurs (Borch & Førde Citation2010) and contribute to re-establish lost linkages within and between natural and human systems (Selman Citation2012). Moving from vicious circles towards virtuous circles in small towns, creative processes should be based on mutually reinforcing activities between much-needed economic development and social cohesion (Hamdouch & Ghaffari Citation2017). Hence, a focus on both individual and collective processes is important to enable reinforcement of virtuous circles between actors and underlying forms of landscape capital for regenerative communities (Selman & Knight Citation2007). However, moral support from local authorities is crucial for the long-term relationships between different actors involved in development grounded in local resources (Hamdouch & Ghaffari Citation2017). Both economic support and moral support are important for local initiatives that invest time and resources in local projects (Førde & Ringholm Citation2012). In such cases, there often exist tensions between formal anchoring and creativity (Førde & Ringholm Citation2012), partly due to the nature of formal organizational frameworks that tend to restrict the freedom of creative and spontaneous actings. At the same time, it is fundamentally necessary for local places to meet sustainability issues involving constraints aimed towards preventing the destructive forces of creativity.

Modes of ANT and meshwork

Latour states ‘To use the word “actor” means that it’s never clear who and what is acting when we act since an actor on stage is never alone in acting’ (Latour Citation2005, 46). In order to study complex relationships of change and becoming within place-making and everyday life, the actor–network theory (ANT) can be used to understand the social and natural world as continuously generated effects relating to webs of relations within which they are located (Law Citation2008). This perspective allows for all kinds of actors involved in agencies, such as objects, subjects, concepts, humans, machines, nature, and ideas. The authors of ANT studies relating to tourism have pointed to the need to move beyond dichotomous understandings of tourism as either economic or cultural, and to encourage researchers to follow actors outside the traditional tourism discourse in order to contribute new insights (van der Duim et al. Citation2013). ANT provides a means to move around, make connections and follow relationships between seemingly opposed positions or dualisms. Studying entrepreneurship and creative processes inspired by ANT can help to establish important connections with actors other than human ones (Jóhannesson Citation2012). However, Latour (Citation2010), in reflecting on limitations of the network approach, suggests that it is useful for making connections, but not to live. According to Latour (Citation2010), the value of the network is that it is easy to insist on its fragility and the empty spots it leaves around. ANT provides analytical lenses for understanding relationships between many different local and non-local actors relating to social creativity emergence.

Ingold (Citation2011, 145) states: ‘A world that is occupied but not inhabited, that is filled with existing things rather than woven from the strands of their coming-into-being, is a world of space’. The quote relates to his conception ‘logic of inversion’, highlighting a central modern way of conceptualizing landscapes by turning the pathways along which life is lived into enclosed boundaries. In response, Kenneth Olwig notes that landscapes ‘should be shaped from the inside by assemblies that know their things, not by the assemblage of things within framed, netlike and boxed space’ (Olwig Citation2016, 270). Tim Ingold’s concept of meshwork offers a different mode of inquiry from ANT by placing stronger emphasis on the forces at work around individual lifelines within the landscape (Ingold Citation2011). He uses the term ‘meshwork’ to denote that action emerges from the interplay of forces conducted within entanglements of individual lifelines, instead of seeing the world as interconnected points. The meshwork is not limited to one place, since individuals move between places, where lines become entangled and knotted.

Ingold’s perspectives have evolved considerably since the late 2000s, moving away from concepts such as dwelling and placing stronger emphasis on movement and flow through perspectives of inhabitation and wayfaring (Wylie Citation2016). Whereas ANT can contribute towards understanding the wider actor networks involved in agencies, Ingold (Citation2011) focuses specifically on individuals within their situated environment, where they breathe the air and walk the ground, which also encompasses how they join shared forces and attend to each other through direct encounters (Ingold Citation2015). There seems to be an important temporal difference between ANT and meshwork, one that relates to different modes of inhabiting the world (Lindstrøm & Ståhl Citation2015). Whereas network refers to connected and planned routes, meshwork refers to trails emerging through wayfaring in knotted entanglements. Further, whereas ANT invites the researcher to identify, map, follow, and connect actors, meshwork invites the researcher to explore improvisations and individual movements in ongoing of life.

Vardø in the subarctic and northern territories of Norway

To understand the place-making stories presented in this section in relation to the literature and analytical lens, a wider contextual description related to the case of Vardø is needed. The northern landscapes have long traditions of coastal fisheries (Meløe Citation1998). Fisher-farmers have played a major role in local communities, as well as in the Norwegian welfare model (Brox Citation1969). Nature-based life in traditional fishing villages has led to local emotional affiliations with universal occupations – a stance that is at odds with national ideals (Rossvær Citation1998). Some argue that government policies relating to the distribution of fishery quotas, which favour well-to-do capitalists and their trawlers, have caused the neglect and undermining of communities in the northernmost regions of Norway (Trondsen Citation2013). This is a deeply felt frustration for the ‘Coastal Rebellion’, a group of Vardø-based activists. Since 2017, the activists have mobilized fishing villages in the north to fight for coastal fishermen’s rights to harvest the ocean. During spring 2017, a public meeting was held in Vardø in conjunction with the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries’ proposed ideas of reversing the trawler owners’ obligations to deliver fish to coastal communities. The minister and her colleagues were met with banners and slogans carried by hundreds of people from Vardø and Varanger. On 1 May 2017, people in Vardø (for the first time in 25 years) organized a parade to celebrate the international workers day under the claim that ‘the fish belongs to the people’.

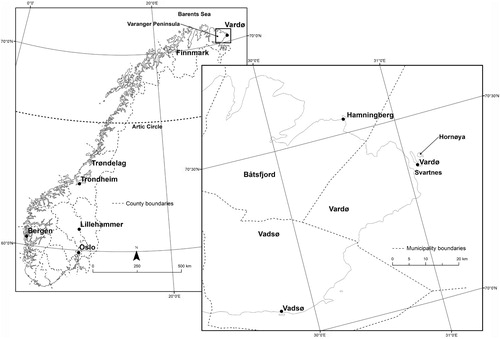

Vardø Municipality spans the mainland, the island of Vardø, on which the town of Vardø is located, and Hornøya nature reserve to the north-east of the town (). Vardø is connected to the Varanger Peninsula by a tunnel, located close to the productive fishing fields in the Barents Sea. There is a vibrant Arctic atmosphere, with Northern Lights during the dark winter months and midnight sun in the summertime. The visible land masses along the shoreline are vestiges of the ice that receded some 12,000 years ago (Brekkhus et al. Citationn.d.). The Gulf Stream has enabled settlement in the Varanger region and it keeps the sea free of ice all year round. The climate is very harsh, with long winters, violent storms and changing weather conditions, rendering mobility unpredictable. The region is multicultural, with a mix of Sami, Finnish, Russian, and Norwegian people and traditions. For centuries, Vardø functioned as a military outpost and administrative centre for trade and fisheries in the far north (Balsvik Citation1989). The town lost many of its administrative functions during the 1970s, and in recent decades Vadsø has functioned as the administrative centre of Finnmark County.

To counteract a negative spiral, new governmental offices were established in Vardø in 2005. Today, these offices are considered very important for the town, while some inhabitants had the feeling that the establishment should not have been necessary for a place like Vardø. The town has maintained its strategic position within a geopolitical area of tension due to radar installations, with increased NATO surveillance of Russian activity in the north. The increased military activity has provoked Russia, which has responded with simulated bomb attacks. This contrasts the way that many people living in this region identify with their neighbours, as part of a rich cultural history of trade and partnerships. The powerful forces at work such as the military activities, national policies and different industrial positionings have combined to cause the radical uncertainty for people living in this small town. At the same time, these conditions have sparked the motivation for local mobilization processes, the formation of local alliances, new stories, and an aspired-to future.

Janike Kampevold Larsen (Citation2018) describes the coastline of Vardø as a connecting zone, thus highlighting its open and globally connected history, which is based on a development grounded in local resources. However, today, multiple extraction industries have positioned themselves for the next ‘big thing’, such as oil and gas production in the Barents Sea, fish farming, and tourism. The Arctic ice melt has opened up for increased transportation activity through the Northeast Passage. For many years, Vardø Municipality has been preparing for new activities in the northern waters. Between 2008 and 2012, the municipality and private investors spent NOK 1 billion (EUR 104,071,268) on supply harbour infrastructure on the mainland at Svartnes (Kampevold Larsen Citation2018). A number of inhabitants were frustrated by those investments, while at the same time they saw that the old fishery harbour at the heart of the town was falling apart (). The municipality has highlighted tourism as an important industry for the future. However, several inhabitants were of the opinion that little had been done to support local tourism entrepreneurship and smaller place-making initiatives in the past. As a response to the old industrial thinking, one local tourism entrepreneur said, ‘while we have a great tradition with the fish, we do not have any experience of managing place-making and value creation across different kinds of smaller scale entrepreneurship projects’.

Place-making stories

Introducing thematic stories

The thematic stories presented in this section, which are grounded in the empirical material, describe emerging creative processes in Vardø. I present the individual lifelines of community entrepreneurs Svein Harald Holmen (Vardø Restored) and Tormod Amundsen (Biotope), which are prominent for understanding the emergence of social creativity in Vardø. Additionally, I present thematic stories related to the restoration of Vardø and involving historic buildings and house owners, Komafest (a street art festival), and the research project Future North, run by the Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO). Thematic stories related to Biotope cover the bird festival, Gullfest, and the island of Hornøya and its bird life.

While the themes involve many different individual lifelines, actors also exist within networks. Within the thematic stories, I make connections between town festivals, entrepreneurs, the Coastal Rebellion, and Vardø Municipality, while acknowledging that many individuals mentioned in the stories are part of a meshwork of lines (). I also make connections to other actors at work related to the meshwork such as national funding programmes, in which the financial resources have been fundamentally important for the emerging stories of Vardø Restored. The contextual description involving national policies and various powerful forces involved in Vardø provides an important background for understanding sparks related to the mobilization processes and local alliances within these thematic stories.

Svein Harald Holmen and Vardø Restored

Svein Harald Holmen started Vardø Restored in 2012 to help local house owners with applications for funding to restore old buildings of national cultural heritage value. The idea behind Vardø Restored has been to create new stories about Vardø by regenerating pride in the town’s cultural history through empowering residents to start new development initiatives and by enabling synergies between projects. Rasmus Skydstrup, a skilled craftsman who once worked on Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim, worked together with Holmen and house owners for several years. Storytelling has been very important for Vardø Restored, as is evident from the personal stories of house owners, the restoration work and art projects on the organization’s website. Until 2018, Vardø Restored was part of Varanger Museum. Today, it is a private non-profit organization led by Holmen and landscape architect Brona Keenan. During the 2017 Yukigassen (snowball festival) and the Pomor Festival (two of the town’s five annual festivals) Vardø Restored and a local chef collaborated on food concepts. The Tenning storytelling festival in 2018 was a collaborative project between Vardø Restored and activists from the Coastal Rebellion, who invited Professor of Sociology Ottar Brox as one of the key speakers.

In 2017, Holmen (aged 40 years) told me about his childhood in Vardø, when it was normal to begin working in the fishing industry at 12 years of age. His motivation for Vardø Restored relates to his deep love of his home town and its inhabitants, and his fear of losing it as a place for coastal fisheries. He recalled that when he returned to his home for Christmas in 2003, after UN military service in Kosovo, the experience was very emotional for him. A fishery crisis in 2002 had caused a major community breakdown, as 270 people had lost their jobs. Holmen described the gloomy atmosphere in a partially abandoned place compared with the lively town that he had left in 1998. He then bought a café in the abandoned fishing village of Hamningberg in Båtsfjord Municipality, Finnmark, where he ran a profitable business serving tourists. The village, located c.28 km north-west of and one hour’s drive from Vardø, is a very popular place for visitors and second-home owners. After being involved in a National Tourist Route (Nasjonale turistveger) project and a cultural heritage project, Holmen became increasingly frustrated with top-down bureaucracy that resulted in conflicts.

After a personal crisis Holmen spent a couple of weeks in Canada learning about indigenous methods for creating space for dialogues and common ground for knowledge sharing between local people and different actors. He returned to Hamningberg and managed to turn the situation around by using some of those methods, which became known as ‘the lavvu method’. After a while, Holmen became the project manager of the value creation programme for cultural heritage in Hamningberg (directed by the Directorate for Cultural Heritage), as well as for a natural heritage programme (directed by the Norwegian Ministry of Environment), and a regional park project in Varanger. Through the natural heritage programme, Holmen saw the potential in funding Biotope’s ideas and bird tourism. This led to the pre-study, ‘Birding Destination Varanger’, developed by Biotope, and the establishment of the first wind shelters in collaboration with the National Tourist Route project.

Tormod Amundsen and Biotope

Biotope is a nature architecture company that uses architecture as a tool to protect and promote birds, wildlife and nature. In 2009, the company’s two architects Tormod Amundsen (aged 40 years) and Elin Taranger moved to Vardø with the aim of making Varanger the world’s best Arctic birdwatching destination. Earlier, the Finnish tourism industry had transported tourists to Varanger for birdwatching. Today, this practice has changed, as many new local and regional actors have become involved in the industry, such as Wild Varanger, which takes tourists out to sea and lets them dive with guillemots. Since 2009, Biotope has been working with nature and Arctic birds, designing wind shelters and developing destinations in the region. The adoption of a bird’s perspective in Varanger has resulted in 16 wind shelters, designed with deep knowledge of the birds’ behaviour, ecological conditions, landscape qualities, and birdwatchers’ needs. The story of Biotope is about Arctic birds and visitors connected through both specially designed wind shelters and high-tech equipment in terms of cameras, telephoto lenses and binoculars. On Biotope’s Facebook page, which boasts more than 8000 followers, Amundsen presents stories about the region’s birdlife and stories about fishery resources, politics, birds, and the future derived from conversations with fishermen.

By the time Amundsen reached the age of 15 years, he knew the scientific name of almost every bird species in Europe. Having grown up in the county of Trøndelag in Central Norway, he had spent a lot of time in the great outdoors. After a trip to Vardø while studying architecture in Bergen, he was dazzled by Arctic nature and the development potential. At the same time, he noted the extensive pessimism due to the economic depression. When Amundsen, Elin Taranger and their daughter first settled in Vardø, they met with a lot of resistance and scepticism regarding their ideas. According to Amundsen, as a place for residents and tourists, Vardø was fundamentally dependent on maintaining the place as an intact and authentic fishing village. Biotope has gained much attention nationally and internationally within the tourism industry, as well as among architects and birdwatchers. In recent years, Biotope has had seven employees working in Vardø. However, as a consequence of its involvement in many international projects, a restructuring of its Vardø-based office has been necessary. Recently, the firm opened an office in England, and the main office may relocate to Denmark or Sweden.

Gullfest – bird festival

Biotope has arranged a bird festival, Gullfest, in Vardø each year, which has become quite popular within the community. As part of this festival, there is collaboration between Biotope and the local school: workshops are held, when children, teachers, Biotope employees, volunteers, and artists come together to producing paintings of birds and make bird boxes. Field trips are organized with the children to learn about different bird species and the shared environment. Professional artists and birdwatchers with knowledge and experience from the British birdwatching community are brought in to help facilitate these events. Talks and exhibitions are held, during which local people and families meet with people from the birdwatching community. Many of the inhabitants proudly discussed this work as a very good example of local development and involvement praxis. One of the schoolteachers said that whereas earlier, children had only known two types of birds – seagulls and sparrows –they could now name many birds.

Hornøya

Many of the inhabitants living in Vardø said that the ‘bird islands’ were places they went to gather eggs in the springtime. Hornøya bird cliff, which is located within a 10-minute boat ride from Vardø harbour, is currently a significant resource for the tourism industry. Biotope has played an important role in marketing the area in the global birdwatching community, in which Amundsen had been involved in guiding groups of people. Easy access to this Arctic place and a large number of bird enthusiasts has made the potential for economic development relevant. Traffic is restricted on the island and only simple trails are provided.

A marked trail from the bird hide leads to Hornøya Lighthouse, a protected cultural heritage site, where it is possible to stay for NOK 400 per night. This has served as a base for many visitors, including large TV production crews from NRK (in Norway) and the BBC. As a nature reserve, Hornøya is home to thousands of endangered Arctic seabird species, such as the common guillemot, kittiwake, Atlantic puffin, razorbill, and shag. From January to April, the iconic Steller’s eider and king eider migrate from Siberia to different localities in Varanger. The birds migrate for the same reason as people do, namely for easy access to fish. The island and its ecosystems have been under the scrutiny of researchers due to climate change and increased tourism, suggesting that increased pressure in recent years has negatively affected the successful breeding of the common guillemot and shag.

Historical buildings

The colourful building environment in Vardø town lies low in the terrain within the open Arctic landscape. Many of these buildings are part of the largest intact urban structures in Finnmark that were built before the bombings during World War II, thus representing stories from the Russian–Norwegian Pomor trade era (1740–1917). Some of the houses are constructed from timber that was floated down the rivers from the Russian inland forests towards the White Sea, loaded onto boats, and then shipped to Vardø. In the late 18th century, there were 12 bakeries and fancy hat stores in the town. Currently, there are ongoing initiatives to revitalize one of the old bakeries. The owner of that building moved back to Vardø from Lillehammer to work on the project as part of the Vardø Restored project. Restoration processes have stimulated the upgrading of Østre Molokrok, which houses facilities for fishermen in the heart of the old fishery harbour.

Around 50 buildings have been included in the Vardø Restored project and over NOK 10 million (EUR 1.04 million) was received from national cultural heritage institutions for the purpose. The latter investments have released many new private investments in the town. As an example, the owner of the restaurant Nordpol Kro received NOK 400,000 (EUR 41,628) to replace old windows. This led to private investments of NOK 600,000 (EUR 62,442) to build a modern music scene, which in turn led to the establishment of a music club in Vardø that books artists to perform at Nordpol Kro and elsewhere in Vardø. The owner of Nordpol Kro considered that Vardø Restored had been vital for the continuity of the oldest restaurant in the north of Norway: ‘I nearly had to shut down here. Without help, we couldn’t have replaced all the windows, and, of course, we identify ourselves with the buildings, particularly when they are restored.’ During previous Gullfest events, Nordpol Kro has been an important meeting place for residents and visitors, with talks and exhibitions held there.

Komafest

In 2012, the artist Pøbel arrived in Vardø after working with street art projects in Lofoten and came up with the idea of the festival named Komafest. The intention was to use art to highlight that depopulation and decline in Norwegian districts related to centralization and fishery politics. Pøbel contacted Svein Harald Holmen to discuss the idea of using art to spark further restoration projects in Vardø. However, he made it clear that it was not possible to succeed by being anonymous and that they needed to build the project from the bottom up.

The two men drove around the town and presented the idea to house owners, the mayor, the local chef, and craftsmen, among others. In the course of a few days, they obtained permission from more than 50 house owners to paint their external walls. Holmen said that they enjoyed a tremendous driving force in the project, because they involved people in every step of the process. This resulted in 13 well-known international artists creating 55 pieces of art, through which shame over decaying buildings was turned into pride and hope for a better future. Many people spoke enthusiastically about the festival as an occasion when almost the entire community took to the streets. House owners were involved in deciding what motifs would be painted on their walls. According to one resident,

Komafest got people to care about their houses again. Many of the houses with street art are bought up now, and there is ongoing development inside a lot of them. Before, people were ashamed of the town. They said, tear down this old [expletive]! Today, this has changed, and it changed fast with the street art. It woke up a lot of people here.

Future North

Since 2013, Vardø Restored has collaborated with the Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO) on many different research activities and student endeavours. The research project Future North studies ongoing changes in the Arctic from a landscape perspective. In collaboration with Vardø Restored, the project members have created and designed scenarios, engaged in participatory processes, undertaken mappings, and held discussions on cultural values and future orientations. This has been part of the work towards a new cultural heritage plan for Vardø.

Examples of designed scenarios have included the reuse of public spaces and old bakeries. The visionary master’s thesis titled Savour the Past, Taste the Future: Community Regeneration Through Food Heritage in Vardø, co-authored by Keenan and Hamaker (Keenan & Hamaker Citation2016), led to Keenan working full-time at Vardø Restored. The representatives of Future North concluded that there was a future for Vardø as an attractive place for tourists, artists, and potentially as a hub for cultural engagement and learning. Within my empirical material, involved local actors stated that Future North had been important as a source of inspiration and motivation. New projects had been planned with the aim of strengthening the relationship between Vardø Restored, the municipalities, and different culture-related place-making projects.

Place-making and emerging social creativity

Introducing a model

Based on the thematic stories obtained both during my research and from the literature, in this section I present a general conceptual figure expressing the relationship between place-making and emerging social creativity. is not an expression of balanced components, since the component of place comprises all existing practices and actors. Rather, it illustrates a procedural context for transboundary and continuous processes involving place, community entrepreneurs and creative community arenas, and contributing new enterprises that materialize in social creativity and potentially virtuous circles. The enterprises component encompasses what has been done and what has not been done, addressing new undertakings, engagement, hope, possibilities, and fragile connections. In the following, I briefly discuss the place component, before discussing the components of community entrepreneurs and creative community arenas in relation to the empirical material. The analytical lens for the model is inspired by two different modes of inquiry: individual lifelines acting (meshwork), and actors involved in acting (ANT).

Place as context for place-making and social creativity

The context of rapid changes in the Arctic identified by Kampevold Larsen & Hemmersam (Citation2017; Citation2018) and for small towns in general (Nyseth et al. Citation2017) has motivated the place-making perspective inspired by Førde (Citation2010) and Selman (Citation2012). Selman addresses the question of how recreating a living economy grounded in local resources requires investments in many different areas. In the case of Vardø, Vardø Restored and Biotope have contributed restoration projects, community activities and tourism initiatives. In this respect, ANT (Latour Citation2005; Law Citation2008; van der Duim et al. Citation2013) has been instrumental in enabling me to make connections between place-making and tourism-related actors.

The case study revealed how the restoration and transformations of historical buildings, such as Nordpol Kro, and the increase in birdwatching tourism, were mutually stimulating. Other actors of importance for the actions of Biotope and Vardø Restored included festivals, a chef, the Coastal Rebellion, and the fisheries. The thematic stories show how they tended to each other’s needs, as shown by the care and mutual respect they showed for their individual projects. This finding highlights the interplay and correspondence between individual lines at the local level, rather than interconnected points (Ingold Citation2015). The place component is important for identifying and acquiring knowledge of the existing situation and challenges, as well as the becoming of informal local alliances, involving actors and lifelines and movements towards virtuous circles (Selman Citation2012) relating to the in-depth focus on community entrepreneurship projects.

Community entrepreneurs

Place-specific engagements

Development processes related to Vardø Restored and Biotope showed that individuals were strongly committed and through vigour and creativity they invigorated the community in new ways. The acts of both Svein Harald Holmen and Tormod Amundsen in accordance with opportunities in locally-based resources can clearly be related to the concept of affordance, as described by Ingold (Citation2011). They both actively assumed different roles in society and appeared as important actors for change (Haukeland Citation2010) by helping to set in motion new place-specific stories about Vardø. A common trait was that both Holmen and Amundsen were heavily involved in the place by virtue of living in Vardø and were working to create local and regional values.

Holmen’s project demonstrates how his deep love of his home place and fear of losing it functioned as a powerful driving force for change. By contrast, Amundsen’s story reflects lifestyle interests serving as a core motivation. This reflects the fact that both entrepreneurs were acting in accordance with their inner basic values as the driving force for their community development projects, which in turn shows how a strong commitment can evolve as a result of various relationships to place; based on one’s skills, knowledge and life stories (Ingold Citation2011). An important means of stimulating social creativity towards contributing to dynamic and vibrant landscapes is to accommodate motivated individuals with a strong commitment to the place’s resources and community, which in development projects are an intrinsic part of their individual lifelines.

Broad value creation

Collective solutions are a central element of community entrepreneurship (Borch & Førde Citation2010). One key characteristic of community entrepreneurs is their collective approach and that they relate to a place with expanded value creation perspectives. Inspired by broad value creation (Haukeland & Brandtzæg Citation2009), Holmen developed a strategy for cultural and social creation to bolster shared stories of the town and opportunities for house owners. The strategy represents an awareness of the link between the social field and cultural heritage, thus resonating with the Faro Convention (Council of Europe Citation2005) and the European Landscape Convention (Council of Europe Citation2000), and emphasizing collectively shared cultural heritage and social values related to the intangible landscape.

In a different way, Amundsen entered the social field based on lifestyle interests and the necessity of making the project financially relevant. However, to ensure his project in Vardø would be successful, he took steps to create local commitment and a sense of universal ownership in terms of birdwatching and related activities. Irrespective of Amundsen’s motives, the aforementioned steps served to activate the social and cultural value creation field. For places such as Vardø, which are in great need of new jobs and opportunities related to the economic sector, as highlighted by Kampevold Larsen & Hemmersam (Citation2017), Biotope opened up for a new sense of community and social creativity through local development grounded in local and regional resources. The development in Vardø shows the importance of perceiving the use and protection of nature and culture also in a wider local and societal context, in which values are fundamentally dependent on people who care about the places where they live.

Sensitivity

Creativity in relation to place depends on individuals’ sensitivity, which involves an eye for place-specific contexts (Nyseth et al. Citation2017). This can be seen in conjunction with the way Holmen and Amundsen related to the natural environment and community life in Vardø. With regard to the example of Vardø as a tourist destination and fishing village, one of the fishermen said: ‘You can say whatever you want about tourism and birds and all that, but it is not enough for 2000 people to make a living from. We need fish, and we need them badly.’ The quote expresses the strong relationship between society, the sea and fish. The fisheries represent a rich cultural history that is an important aspect in the foundation for settlement in Vardø, an aspect that many feel is under threat, as demonstrated by the Coastal Rebellion. By virtue of Holmen’s heavy personal involvement in this story, Vardø Restored itself is grounded in emotional and symbolic aspects of local development (Vestby Citation2015).

Amundsen’s understanding of local complexity appears similar in relation to this strongly pressured community, as he was involved in the local fishermen’s struggle for the survival of coastal fishing, creating a dialogue about fish, birds and potential futures. Such sensitivity contributes to positive relationships between tourism and fishery activities, with common interests and consciousness aimed at safeguarding and developing a vibrant coastal society. However, this does not represent planned routes and connections between things, but rather lived improvisations along the lines, whereby individuals tend to each other in a world of becoming, and in which things are not yet given (Ingold Citation2015).

In drawing inspiration from Ingold’s concept of ‘making’ (Ingold Citation2013), creativity can be understood as an emerging process through which individuals enter into a world of already existing material processes. In turn, this refers to the concept of affordance. In Vardø, the concept of affordance can be understood as due to the Arctic qualities that distinguish the geographical locality in which the projects and lives are unfolding. In this respect, creativity is understood as emerging through different variable, relational factors, wherein the weather, wind and light are inextricably intertwined with Holmen’s and Amundsen’s day-to-day life and projects within the landscape. This does not represent connections in networked space, as Ingold (Citation2011) puts it, but lived conditions in which the forces of weather are directly entangled with individual improvisations in the landscape.

The distinctive place-specific qualities within the Arctic affect individual’s creativity. The fact that wind shelters are used in local outdoor activities as well as for birdwatching expresses a collective sensitivity. Stories are told about the weather, Northern Lights and bird species, as illustrative of the vivid Arctic features told via Biotope’s social media. Technological connections to the international birdwatching community through social media storytelling highlight other important workings within the wider actor network (Latour Citation2010). Additionally, the skills involved in storytelling in the digital world, combined with community entrepreneurs’ sensitivity to the wider landscape context, are a very important part of communicating with inhabitants in Vardø, and for inspiring, informing and creating awareness of birdlife and its development.

Credibility

Both Holmen and Amundsen had a high degree of trust in Vardø and this can be seen in the context of what Clemetsen & Stokke (Citation2018) call integration actors, for whom high levels of trust and legitimacy are crucial for their role. Common to the two individuals is that they both lived and worked in Vardø, where they contributed to local value creation, involved the local community, created awareness and pride in local resources, and enhanced local ownership of the development. This can also be seen in the context that they were prime movers by virtue of their skills, personal characteristics and ability to produce results.

My empirical data show that from 2009 Biotope worked actively to legitimize its ideas about birdwatching, which were met with scepticism at the local level. As the result of necessary partnerships, mobilization, inclusion, transparency, and targeted activities in the local environment and in the Varanger region, scepticism was clearly reversed and turned in a positive direction, thereby contributing to social creativity. This meant that also trust ensued as a result of a group of people recognizing the integrity of the individual (Clemetsen & Stokke Citation2018). Furthermore, Holmen’s story shows how a high degree of trust was achieved through many years of experience in managing the processes in the field of cultural heritage and was strongly motivated by community values. Yet another important factor for building trust is that both entrepreneurs were strongly motivated by other factors than economic self-interest.

Creative community arenas

Direct encounters

In Vardø, artistically driven processes have been an important part of the local development, involving an important duration for creative processes, as highlighted by Hallam & Ingold (Citation2007). Each year, Gullfest involves the local elementary school representing an arena where pupils build bird houses and produce paintings of birds. Working with local school plans is a way to create a continuum in which the children in Vardø will grow up with a stronger ecological awareness of the inherent value of the birds found in the area, where also activities for birdlife protection and exhibitions enable the children’s families to become involved.

In line with Ingold’s thinking (Ingold Citation2013; Citation2015), creativity emerges through direct encounters between many corresponding lines, where inhabitants experiment with their way into the future within their surroundings. However, the British birdwatching community’s involvement in Gullfest connects Vardø to new international communities too, addressing the open local–global network (Massey Citation2005). The international street artists have a strong influence on heritage processes and other lines of the meshwork in Vardø. My empirical data show how the place-specific art sets emotions, thoughts and body in motion, thus helping people see new opportunities and raising hopes for the future. In this respect, creativity is activated through the place-specific approach that underlies the shared processes, thereby helping to provide direction for the emergence of social creativity. This in turn highlights how both Komafest and Gullfest can be regarded as actors (Latour Citation2005; Law Citation2008) due to their strong contribution to social creativity emergence.

Future motives

Social creativity in local development involves experimenting with alternative future scenarios and requires perspectives that depart from linear, rational expedience and sector demarcation. Komafest became an important arena for social change with hope for the future. Vardø Restored has worked with Future North over a long period of time, another actor that distinguishes itself in terms of how emerging social creativity can be understood. The design of various future scenarios and participatory processes related to further opportunities for homeowners has helped to bolster motivation and to open up for social creativity. An important aspect in this regard is continuity, along with the fact that, over a period of several years, an arena has been created for meetings between Future North and the local community, in which Vardø Restored has served as an important networker (Borch & Førde Citation2010).

Keenan & Hamaker’s master’s thesis is another example of a contribution that has opened up people’s perspectives on their own home place, as the authors carried out prolonged periods of fieldwork consisting of mappings, participatory processes, design, and new visualizations (Keenan & Hamaker Citation2016). It is also an example of how skilled individual design practice intersects with technology, resources, people, memories, and imagined futures (Law Citation2008; Latour Citation2010). However, in this regard, an important point is that the dialogic processes, as well as the drafting and designing of future scenarios, represent important meetings that help to generate ideas about the future. In this respect, community development in Vardø provides evidence that experimental approaches have been important for social creativity (Nyseth et al. Citation2017).

Enterprises and connectivities

The place-making initiatives with strong community orientations in Vardø have been instrumental in opening up for new stories based on individual and shared values. Social creativity can be identified through different factors that become active as a result of local development. As furthered by Jóhannesson (Citation2012) when using ANT, this is not merely a matter of physical materialization in the landscape, such as wind shelters or restored buildings, but also of non-realized ideas, heightened awareness, optimism, belief in the future, and enhanced relationships. In Vardø, this includes heightened awareness concerning shared cultural history and birdlife, restored houses, new ideas for local development such as the bakery project and the cultural hub in Grand Hotel, increased volunteering and bolstered voluntary spirit, new tourism entrepreneurs and local development projects, and positive relations between fisheries and tourism. New entrepreneurs with strong social affiliations have become active, such as the owners of Østre Molokrok, who were working to upgrade the historic fishing port. Additionally, Biotope has opened up for new ideas and opportunities in Vardø. Such activities, in various ways, are ancillary to the self-reinforcement of local development, which strengthens landscape quality as well as the sense of community, and contributes to a more vibrant landscape (Selman & Knight Citation2007).

The dimension of enterprise () has an important role in addressing the fragility of networks, as addressed by Latour (Citation2010). In Vardø, several of the house owners are in need of dedicated business plans and development strategies to be able to move on and to build on the work that has been done in the last decade. New initiatives and cooperation between research environments, local projects, and the municipality would be important steps forward to manage value creation activities with sensitivity to contemporary challenges.

The case study shows that local authorities seem to have focused on big industrial thinking favouring major external actors. In this respect, there clearly exist tensions between creative initiatives and the formal and traditional municipality planning and development thinking (Førde & Ringholm Citation2012), thus representing challenges for actors such as Biotope and Vardø Restored. Hence, moral support is crucial for their long-term commitment, and this highlights many different value perspectives, contradictory interests and future motives. Major uncertainties for the future regarding Vardø Restored highlight the fragility of private actors that depend on external funding and exist with limited municipality support. The study also highlights the need to strengthen relationships between nature conservation management and private actors that are stimulating activities within protected areas.

Summary

The model in reflects the need for inhabitants within places such as Vardø to act creatively and responsibly to enable future development possibilities grounded in local resources. This is illustrated in the model by relationships between place, community entrepreneurs and creative community arenas. The last component in the model (enterprises) reflects new undertakings and fragilities, which should be taken into consideration for further processes. My discussion has addressed the multiplicity of relations within the overall procedural context.

Place-making and social creativity need to be seen within the broader context of the place, drawing attention to present situation and challenges, humans and more-than-human actor-dynamics, positionings, and alliances at work. The role of two community entrepreneurs in mobilizing and responding to local realities discussed in this article are expressed in the model () by virtue of their place-specific engagements, broad value creation, sensitivity to place complexities, and credibility. The model also expresses the important relationship between community entrepreneurs and creative community arenas, enabling social creativity to emerge through direct encounters between individuals, actors and non-human actors. The artistically driven processes, experimentation and involvement discussed in this article, contribute to the emergence of future motives and social creativity.

Conclusions

In relation to the two entrepreneurial projects in the case study, social creativity is activated when creativity is anchored in the place and its inhabitants, and occurs in creative community arenas in which direct encounters between actors and future ideations take place. Given the impulse of social creativity, the pioneers are also inspired to expand or strengthen their roles within the community. The role of community entrepreneur is activated by virtue of a strengthened community, by contributing to new enterprises. New place-specific enterprises emerge as a result of the community processes comprising a multitude of actor relationships that contribute to renegotiations, from which new movements and juxtapositions emerge. This shows that social creativity is influenced by many different interacting actors, who must also be regarded in the light of their individual lifelines and the situated environment. A dynamic relationship between creative place-specific projects and community processes is an essential prerequisite for long-term responsible local development and the emergence of social creativity. A conscious awareness of this requirement may contribute to both individual and joint value-oriented opportunities and stories, and to the creation of self-reinforcing dynamics between actors and activities in place.

To manage challenges related to inherently destructive creativity existing within the commercial tourism discourse, the model developed in this article () is not enough. Tourism very often leads to unintended consequences and needs to be met with formal planning and regulations as well as place-specific creativity. To enable social creativity through local development processes involving tourism requires a departure from the product-oriented destination discourse. The perspective developed in is transferable to other local contexts, particularly declining places in districts. In this respect, the model () can be used as a framework for analysing qualitative place-making complexities, as emerging and continuous processes rather than results. The conceptual framework opens up for moving beyond traditional borders, encouraging a view on understanding the role of different inhabitants, the coming together of individuals and actors, and potentially reinforcing activities.

By combining the modes of meshwork and ANT, the model presented in this article is a flexible contribution to analyses of emerging social creativity through practical entrepreneurial and creative processes at the intersection of place-making and tourism. Both meshwork and ANT have deep philosophical roots, which extend far beyond the discussion of the concepts in this article. However, applying the meshwork mode within a practical place-making and landscape context means that one has to be present within the processes of the studied. Through processes of getting to know inhabitants along the lines, as well as their struggles, uncertainties, motivations, desires, and aspirations, more improvised, informal and sensitive aspects became apparent. These have proved of major importance for discussing place-making within places such as Vardø. However, there is a need to develop the framework further in relation to the meshwork–network relationship and in relation to different case areas.

ORCID

Thomas Haraldseid http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8205-3143

References

- Balsvik, R.R. 1989. Vardø: grensepost og fiskevær 1850–1950. Vol. 1. Vardø: Dreyer Bok.

- Borch, O.J. & Førde, A. 2010. Innovative bygdemiljø: ildsjeler og nyskapingsarbeid. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Brekkhus, I.V., Holmen, S.H., Clemetsen, M., Barane, J., Johansen, G. & Bjarnadóttir, S.L. n.d. Varanger regional park: forstudie. https://naeringssenter.no/images/forstudie/VARANGER_forstudie_regionalpark_web.pdf (accessed January 2020).

- Brox, O. 1969. Hva skjer i Nord-Norge? En studie i norsk utkantpolitikk. Oslo: Pax.

- Butler, W.R. 2011. Sustainable tourism and the changing rural scene in Europe. MacLeod, D.V.L. & Gillespie, S.A. (eds.) Sustainable Tourism in Rural Europe: Approaches to Development, 15–27. London: Routledge.

- Clemetsen, M. & Stokke, K.B. 2018. Managing cherished landscapes across legal boundaries: The contribution of integration actors to a functional local democracy. Egoz, S., Jørgensen, K. & Ruggeri, D. (eds.) Defining Landscape Democracy: A Path to Spatial Justice, 165–177. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Council of Europe. 2000. Explanatory Report to the European Landscape Convention. European Treaty Series No. 176. https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=09000016800cce47 (accessed January 2020).

- Council of Europe. 2005. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed July 2019).

- Førde, A. 2010. Nyskaping, brytningar og samspel. Borch, O.J. & Førde, A. (eds.) Innovative bygdemiljø: Ildsjeler og nyskapingsarbeid, 155–170. Bergen: Bokforlaget.

- Førde, A. 2016. Å studere turiststader: metodologiske refleksjoner. Viken, A. (ed.) Turisme: Destinasjonsutvikling, 55–70. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Førde, A. & Ringholm, T. 2012. Planlegging for lokal utvikling: kreativitet og forankring. Aarsæther, N., Falleth, E., Nyseth, T. & Kristiansen, R. (eds.) Utfordringer for norsk planlegging: Kunnskap, bærekraft, demokrati, 238–253. Kristiansand: Cappelen Damm & Høyskoleforlaget.

- Førde, A. & Kramvig, B. 2017. Cultural industries as a base for local development: The challenges of planning for the unknown. Hamdouch, A., Nyseth, T., Demaziere, C., Førde, A., Serrano, J. & Aarsæther, N. (eds.) Creative Approaches to Planning and Local Development: Insights from Small and Medium-sized Towns in Europe, 81–97. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Gerrard, S. 2009. Fra fiskevær til ferievær? Om kystsamfunn i endring. Niemi, E. & Smith-Simonsen, C. (eds.) Det hjemlige og det globale: Festskrift til Randi Rønning Balsvik, 386–399. Oslo: Akademisk.

- Hallam, E. & Ingold, T. 2007. Creativity and cultural improvisation: An introduction. Hallam, E. & Ingold, T. (eds.) Creativity and Cultural Improvisation, 1–24. New York: Berg.

- Hamdouch, A. & Ghaffari, L. 2017. Social innovation as the common ground between social cohesion and economic development of small and medium-sized towns in France and Quebec. Hamdouch, A., Nyseth, T., Demaziere, C., Førde, A., Serrano, J. & Aarsæther, N. (eds.) Creative Approaches to Planning and Local Development: Insights from Small and Medium-sized Towns in Europe, 190–207. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Haukeland, P.I. 2010. Landskapsøkonomi: bidrag til bærekraftig verdiskaping, landskapsbasert entreprenørskap og stedsutvikling: med eksempler fra regionalparker i Norge og i Europe. Bø: Telemarksforsking.

- Haukeland, P.I. & Brandtzæg, B.A. 2009. Den brede verdiskapingen: Et bærekraftig utviklingsperspektiv på natur- og kulturbasert verdiskaping: Bø: Telemarksforskning.

- Hjort, D. & Bjerke, B. 2006. Public entrepreneurship: Moving from social/consumer to public/citizen. Hjort, D. & Steyaert, C. (eds.) Entrepreneurship as Social Change, 97–120. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Ingold, T. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2015. The Life of Lines. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jóhannesson, G.T. 2012. ‘To get things done’: A relational approach to entrepreneurship. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 12, 181–196. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2012.695463

- Kampevold Larsen, J. 2018. Landscape in the new north. Kampevold Larsen, J. & Hemmersam, P. (eds.) Future North: The Changing Arctic Landscapes, 86–105. London: Routledge.

- Kampevold Larsen, J. & Hemmersam, P. 2017. Landscapes on hold. Ray, S.J. & Maier, K. (eds.) Critical Norths: Space, Nature, Theory, 171–189. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

- Kampevold Larsen, J. & Hemmersam, P. 2018. What is the future north? Kampevold Larsen, J. & Hemmersam, P. (eds.) Future North: The Changing Arctic Landscapes, 3–15. London: Routledge.

- Keenan, B.A. & Hamaker, M.F. 2016. Savour the Past, Taste the Future: Community Regeneration through Food Heritage in Vardø. Master’s thesis. Oslo: Oslo School of Architecture and Design, Institute of Urbanism and Landscape.

- Kramvig, B. & Førde, A. 2015. Sted, kunnskap og kreativitet. Aure, M., Gunnerud Berg, N., Cruickshank, J. & Dale, B. (eds.) Med sans for sted: Nyere teorier, 333–353. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Latour, B. 2010. Networks, Societies, Spheres: Reflections of an Actor-Network Theorist. http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/121-CASTELLS-GB.pdf (accessed June 2019).

- Law, J. 2008. Actor network theory and material semiotics. Turner, S.B. (eds.) The New Blackwell Companion to Social Theory, 141–158. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lindstrøm, K. & Ståhl, Å. 2015. Figurations of spatiality and temporality in participatory design and after: Networks, meshworks and patchworking. Codesign 11, 222–235. doi: 10.1080/15710882.2015.1081244

- Løkken, G. & Haggärde, M. 2017. Renewed sustainable planning in the Arctic: A reflective, critical and committed approach. Hamdouch, A., Nyseth, T., Demaziere, C., Førde, A., Serrano, J. & Aarsæther, N. (eds.) Creative Approaches to Planning and Local Development: Insights from Small and Medium-sized Towns in Europe, 208–233. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lønning, D.J. 2010. Kva er nyskaping? Om fridom, skaparglede, framtid og fellesskap. Ål: Boksmia.

- Massey, D. 2005. For Space. London: Sage.

- McLean, S. 2009. Stories and cosmogonies: Imagining creativity beyond ‘nature’ and ‘culture’. Cultural Anthropology 24, 213–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1360.2009.01130.x

- Meld. St. 19 (2016–2017). Opplev Norge: unikt og eventyrlig. Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-19-20162017/id2543824/sec1 (accessed July 2019).

- Meløe, J. 1998. The two landscapes of Northern Norway. Acta Borealia 7, 68–80. doi: 10.1080/08003839008580385

- Nyseth, T. & Viken, A. 2009. Place Reinvention: Northern Perspectives. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Nyseth, T., Hamdouch, A., Demaziere, C., Aarsæther, N., Førde, A. & Serrano, J. 2017. Perspectives on creative planning and local development in small and medium-sized towns. Hamdouch, A., Nyseth, T., Demaziere, C., Førde, A., Serrano, J. & Aarsæther, N. (eds.) Creative Approaches to Planning and Local Development: Insights from Small and Medium-sized Towns in Europe, 13–22. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Olwig, R.K. 2016. Heidegger, Latour and the reification of things: The inversion and spatial enclosure of the substantive landscape of things – the Lake District case. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 95, 251–273. doi: 10.1111/geob.12024

- Rossvær, V. 1998. Ruinlandskap og modernitet: hverdagsbilder og randsoneerfaringer fra et nord-norsk fiskevær. Oslo: Spartacus.

- Selman, P.H. 2012. Sustainable Landscape Planning: The Reconnection Agenda. New York: Routledge.

- Selman, P. & Knight, M. 2007. On the nature of virtuous change in cultural landscapes: Exploring sustainability through qualitative models. Landscape Research 31, 295–307. doi: 10.1080/01426390600783517

- Statistisk sentralbyrå. 2019. Vardø – 2002 (Finnmark, Finnmárku): Befolkning. https://www.ssb.no/kommunefakta/vardo (accessed May 2019).

- Trondsen, T. 2013. Har kystsamfunnene noen fremtid? Jentoft, S., Nergård, J.-I. & Røvik, K.A. (eds.) Hvor går Nord-Norge? Politiske tidslinjer, 345–360. Tromsø: Orkana Akademisk.

- Utenriksdepartementet, Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementet & Statsministerens kontor. (2017). Nordområdestrategi – mellom geopolitikk og samfunnsutvikling. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/strategi_nord/id2550081/ (accessed July 2019).

- van der Duim, R., Ren, C. & Jóhannesson, G.T. 2013. Ordering, materiality, and multiplicity: Enacting actor–network theory in tourism. Tourist Studies 13, 3–20. doi: 10.1177/1468797613476397

- Vestby, M.G. 2015. Stedsutviklingens råstoff of resultat: Funksjonelle og emosjonelle relasjoner mellom mennesker og sted. Aure, M., Gunnerud Berg, N., Cruickshank, J. & Dale, B. (eds.) Med sans for sted: Nyere teorier, 165–176. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Wylie, J. 2016. A landscape cannot be a homeland. Landscape Research 41, 408–416. doi: 10.1080/01426397.2016.1156067