ABSTRACT

The cartographic image of the peripheral European north was vague in the European political and cultural centers of the Late Renaissance, where the ethos was flavored by ambitions of supremacy through exploration and the Counter-Reformation. Maps were practical and symbolic manifestations of those aims. The author discusses the cartographic image-shaping of the European north in the mural atlases of three Late Renaissance Italian galleries. The article’s iconographic scope is derived from the concept of the cycle of mural maps. Holistically interpreted, the cycles of maps reveal the muralists’ desire to satisfy their patron’s will by designing the space according to various cartographic skills and artistic principles. The mural atlases are interpreted as fundamental elements of such cycles. The study is based on personal observations made in the galleries along with existing literature. The map cycles reveal the impulse during the Later Renaissance for obtaining up-to-date geographical information about the European northern periphery. The study reveals Olaus Magnus’s important role in upgrading geographical knowledge about the region, and how in the mural maps reflect his cartographic perception. The author concludes that Olaus Magnus’s depiction of the geographical shape of the European north impacted the iconography of the studied map cycles.

Introduction

In this article, I analyze mural maps in three Italian Renaissance galleries depicting the continental European north: the Scandinavian peninsula, Denmark, and Finland (Iceland excluded). The collections of mural maps, or “mural atlases,” with images of the European north are in (1) the Guardaroba nuova in the Palazzo Vecchio, in Florence, (2) the Sala del Mappamondo in the Palace or Villa Farnese (Palazzo Farnese) in Caprarola, and (3) the Terza loggia in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican (Palazzo Apostolico Vaticano). The mural maps in the Palazzo Ducale (Venice) are not discussed here because the originals were destroyed and replaced with more “up-to-date” murals in the 18th century.

Northern Europe formed the domain of the Kalmar Union (1397–1523), which collapsed as a result of political turmoil in the early 16th century. Olaus Magnus (1490–1557) was one of the first cartographers to give the region an explicit cartographic shape, on his Carta Marina of 1539. Earlier maps of northern Europe had been made by Claudius Clavus in 1427 and Jacob Ziegler in 1532 (Ginsberg Citation2006, 16–21, 37–44). However, the Carta Marina came to establish the imagery of the far north during the second half of the 16th century and beyond (Mead Citation2007, 1781–1789). Olaus Magnus was the last titular Roman Catholic archbishop of Sweden. Exiled from Sweden in 1524, he moved via Danzig and Venice to Rome in 1537, where he lived until his death in 1557. He was appreciated as a clergyman who had attended the Council of Trent in 1545, which launched the Counter-Reformation and was well-known as a Renaissance scholar, cartographer and publisher on northern topics (Johannesson Citation1982, 208–215).

Carta Marina is the generally used short form of the longer title of Olaus Magnus’s map, Carta Marina et Descriptio Septemtrionalium Terrarum ac Mirabilium Rerum in eis Contentarum Diligentissime Elaborata Anno Dni 1539 Veneciis Liberalitate Rmi D. Ieronimi[o] Qvirini[o]: Patriarche Venetiai[e] (“A Marine Map and Description of the Northern Countries and of their Marvels Most Carefully Drawn up in Venice in the Year 1539 with the Generous Assistance of the Most Honourable Lord and Patriarch Hieronimo Quirino”, title translation by Lynam Citation1949, 3). In 1539 Olaus Magnus wrote two 16-page vernacular commentary booklets on the map: Opera breve (“A Short Treatise”), in Italian, destined for southern European savants (Magnus Citation1539a; English translation in Ginsberg Citation2006, 186–195), and Ain kurze Auslegung und Verklerung der neuuen Mappen (“A Short Interpretation and Explanation of the New Map”), in German, for northern European scholars (Magnus Citation1539b; Swedish translation in Magnus Citation1965 [1539]). Olaus Magnus published a complementary text, Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (“Description of the Northern Peoples”) in 1555, which included a small, modified version of the map (Magnus Citation1555; Mead Citation2007, 1788).

The question addressed in this article is: What impact did the cartographic contributions of Olaus Magnus have on the mural maps of the three Italian palaces in the Late Renaissance period? In order to answer this question, I studied the cycles of mural maps through personal observations in the galleries in 2013, 2014 and 2016, along with existing literature, especially that dealing with the cartographic map cycles that also contain geographical representations of the European north (Schulz Citation1987; Fiorani Citation2005; Citation2007). This article follows three lines of investigation:

A comparative study of the mural maps of the European north in the map cycles of the three Italian galleries. I examine the iconographic processes of image-making with respect to the European north in the painted wall maps or “mural atlases” of the three Italian palaces during the Late Renaissance. The term “mural atlas” is used by Kish (Citation1953) in his study of the series of mural maps in the Sala del Mappamondo, Caprarola. Conceptually, the mural atlases are interpreted as systematically organized collections of mural maps in holistically designed spaces using the model of the cycle of maps. I describe the map cycles in each gallery and iconographically the visual, meaningful environment, the “locator,” wherein the mural maps are situated.

A survey of the visual correlations between the mural maps and related printed source maps. The backgrounds of each mural illustrating the European north are traced from contemporary cartographic sources and literature on the history of cartography by assessing the visual correlations between plausible map originals and the mural maps.Footnote1

A comparative study of the actors, defining the essential features of the mural maps that focus on the European north—looking for “mirabilia” (wonders, marvels, or curiosities). Hypothetically, some Italian patrons prioritized cycles of maps as the main leitmotif for designing their personally significant spaces. The potentates’ power positions and intellectual orientations, as well as the interests of Renaissance cartography, are considered in this article. It is plausible that potentates’ own knowledge and the interests of contemporary cartography helped the patrons to hire professional designers, cartographers, and muralists to impart their patrons’ ideological and political “will” through effective cartographic representations, which in turn influenced how admirers or notable guests viewed the map cycles in order to obtain a better understanding of the European north. Some of the wall maps also depict northern mirabilia—wonders, marvels, or curiosities; the reasons for these are given special attention in this article.

In the following, the conceptual background of the article is first presented, followed by a presentation of the distinguishing features of Italian mural maps of the Late Renaissance. The layout and mural maps of the north are then discussed and characterized successively for the three galleries. Particular attention is paid to the Gronlandia mural map in the Terza loggia, on which the mirabilia of the north are depicted. The possible sources for the mural maps are comprehensively discussed throughout, with special focus on the role of Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina and Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus.

Conceptual background

This article is based on the iconographic interpretations of the map cycle formulated by Schulz (Citation1987) and Fiorani (Citation2005; Citation2007). The mural maps form a set of visual representations belonging to a map cycle in a holistically designed space, the gallery. In the map cycle, aspects of the Renaissance worldview (humanism, classical mythology, theology, and cosmology) were manifested through depictions influenced by the sciences, technology, and the visual arts. In the design of a gallery, the mural atlas was a manifestation of a potentate’s value system and power position, articulating hisFootnote2 motives, to which his team of muralists, architects, designers, cartographers, and fresco painters tried to give visual shape and symbolic meanings.

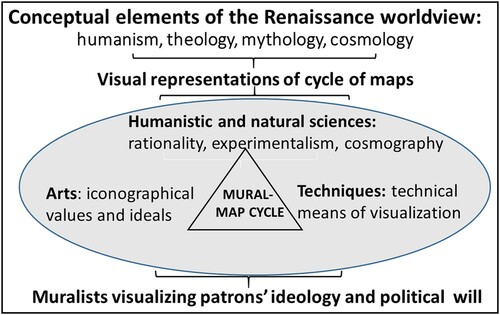

In her review of Fiorani’s book The Marvel of Maps (Citation2005), Della Dora (Citation2005, 1) emphasizes that interpreting early maps involves more than just revealing power issues, which is a topic that Brian Harley focuses on in his article “Deconstructing the Map” (Harley Citation1989). Further, citing Cosgrove (Citation1999) and Casey (Citation2002), Della Dora summarizes the aesthetic, moral, and phenomenological topics that “tie the map and mapping to specific scientific and artistic traditions and spatial perceptions” (Della Dora Citation2005, 1). She argues that these aspects help broaden the approach of Fiorani (Citation2005), and of Schulz (Citation1987), by providing a deeper synthesis of the mural maps of the Late Renaissance. In Scandinavia, Ehrensvärd (Citation1981; Citation1987) similarly sought to link the artistic approach to a visual analysis of early maps. However, in converting the map originals to larger scale mural maps through the creative perceptions of the visual art, with its own practices and ideals, a contemporary assessment of the visual correlations may well become even more complicated. Thus, my approach in this article is more hypothetical than explanatory. A conceptual model for the interpretation of the map cycles is provided in .

Fig. 1. Conceptual model of the cycle of maps, inspired by Schulz (Citation1987) and Fiorani (Citation2005; Citation2007)

Printed versus mural atlases in the Italian Late Renaissance

Manuscripts, printed maps, and mural atlases presented geographical knowledge in differing ways during the Late Renaissance. Manuscripts and printed charts were “open sources,” and as books or rolls they were transportable. The mural atlases were stationary, intended only for certain closed spaces and accessible only to visitors selected by the patron for certain reasons.

The working processes differed between printed atlases and mural atlases, too. Map printing required wood-cutting or copper-engraving specialists, who transformed the cartographer’s sketch maps into plates for the printing press. The printing process limited the size of the maps to the size of a book or separate loose sheets to be glued together to form a larger map, a wall map. By contrast, the making of mural maps utilized the traditional fresco technique in dryer climatic conditions, such as in Rome, or tempera painting on wood or canvas in moister places, such as Florence and Venice (Fiorani Citation2007, 807). In the making of mural maps, fresco painters and muralists rather than cartographers played a crucial role. They converted a sketch map into a painted mural map, the size of which might be much larger than any printed map. One substantial discrepancy between the printed maps and murals was that the muralists had a wide range of colors at their disposal for depicting the geographical features and symbolic figures.

In the Late Renaissance, the mural maps and atlases were avant-garde in representing a contemporary image of the world, as well as cosmographical knowledge, by means of scientific cartography. Such maps became popular among mapmakers in the late 16th century. The mural maps were not simply wall decorations alongside other architectural features, but up-to-date sources of geographical information and symbolic meanings reflecting the patron’s worldview and power position. Whereas printed maps were two-dimensional objects, the mural maps were regarded as an indispensable part of a spatial construction, and hence might be interpreted as three-dimensional objects, emphasizing the artistic values of the holistic iconography of the space (Schulz Citation1987, 97–98; Fiorani Citation2005, 7–8).

Mural maps were popular for a short time span, the 1560s to 1580s. The geographical pattern of their existence was similarly quite concentrated. The consumption and production of painted wall maps belonged to the Italian cartographic legacy, which was based on the knowledge, resources, and ethos of ecclesiastic supremacy in the Late Renaissance.

The European north in Italian mural atlases—a comparative study

The Guardaroba nuova at the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence (1563–1586)

The Guardaroba nuova at the Palazzo Vecchio was originally commissioned by Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici (reigned as the Grand Duke of Tuscany 1563–1574) and was completed in 1586 by his successor Duke Francisco as a collection room outfitted with cupboards (guardaroba) for the mirabilia: wonders, marvels, curiosities of nature, and antique relics from various regions throughout the world—similar to the medieval Kunst- und Wunderkammer (Cabinet of Art and Wonders) (Schulz Citation1987, 99). With the exception of a globe, the maps painted on the wooden doors of each cupboard are the only objects preserved in the collection room (); all of the collected items, decorations, and busts of the Renaissance rulers have long since been removed or disappeared. The original idea behind the map cycle commissioned by Cosimo I was to recreate the cosmos in the collection room, with the celestial constellations painted on the vault and the earthly sphere painted on and in the cupboards, which were filled with collected relics and other curiosities (Schulz Citation1987, 99).

Fig. 2. The mural atlas of the Guardaroba nuova (Florence) consisting of maps painted on cupboard doors (110 × 90–110 cm); the map of Norvegia Gotiae is located on the rear wall, upper row, and Livonia et Littuania on the lower row; the late 16th century terrestrial globe has a symbolic location among the maps of the various parts of the world (Photo: Arvo A. Peltonen, 24 May 2014) (Courtesy of the Palazzo Vecchio, Municipality of Florence)

The cycle of maps

The maps on the cupboard doors were meant to decorate the room, which was to hold the duke’s “most precious possessions” (Schulz Citation1987, 98). The architect of Palazzo Vecchio, Giorgio Vasari, characterized the idea of the map cycle as not a reproduction of Ptolemy’s maps, “but rather a comprehensive representation of the earth in the manner of Ptolemy” (Schulz Citation1987, 98). This characterization applies also to other map cycles and the arrangement of maps in printed atlases and other mural atlases. The Guardaroba nuova consists of 57 cupboards. Each door has two maps, but only 53 of the 114 maps were completed (Schulz Citation1987, 99). The designer of the Guardaroba was mathematician and cartographer Egnazio Danti, who oversaw the project from its beginning in 1563 until the death of Cosimo I in 1574.

Cosimo I’s successor, Duke Francesco (Francis, Grand Duke of Tuscany, reigned 1574–1587), fired Danti in 1575. After leaving Florence, Danti served Pope Gregory XIII (reigned 1572–1585) in Rome. Before leaving Florence, Danti had completed 32 maps, among them the map of Norvegia Gotiae in 1565, comprising Scandinavia and Finland (Supplementary Fig. 1). Cartographer Stefano Buonsignori subsequently finished the Guardaroba cycle of maps by painting 18 tempera maps in 1586. The painters of the other maps on the cupboard doors are unknown (Schulz Citation1987, 99).

The European north in the Guardaroba nuova

On the map of Norvegia Gotiae (“Norway and Gothia [Sweden]”) (Supplementary Fig. 1), the Scandinavian peninsula and Finland are recognizable by the shapes of their shorelines, islands, and lakes. The map contains some place names (Rosen Citation2009, 586). The text of the cartouche is somewhat blurry. Danti included on the map geographical information at the same level of accuracy for the Scandinavian peninsula, islands of Denmark (excluding Jutland), and Finland. The map displays the shape of continental north as it appears on Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina of 1539.

Besides Danti’s Norvegia Gotiae, the southern part of the European north is also depicted on Buonsignori’s La Germania (“Germany”) of 1577. On the latter mural map Jutland is represented in more detail. Danti also painted the map Livonia et Littuania (“Livonia and Lithuania”) (no date) (lower row corner, ), which depicts the regions around the Baltic Sea, eastern Sweden, and southwestern Finland. However, the map lacks detailed geographical information and includes few place names. Quite plausibly, Danti learned the shape of the Baltic Sea coastline from the engraver of Giacomo Gastaldi’s map of the Baltic from 1568, which was printed in Antonio Lafreri’s atlas of 1572, Geografia Tavole Nove (Nordenskiöld Citation1973 [1889], 125).

Danti’s Norvegia Gotiae has a strong visual correlation with Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina of 1539. The Carta Marina, consisting of nine sheets, was familiar to both Gerard(us) Mercator (Gerard Kremer) and Giacomo Gastaldi. The European north on Mercator’s map of Europe from 1554 was clearly influenced by Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina, but there are some dissimilarities in the shoreline of coastal Norway, for example regarding Trondheim Fjord. It is plausible that whereas Danti’s Norvegia Gotiae derived its outline from Mercator’s map of Europe (Supplementary Fig. 2), the northeastern part of the European north emulated the cartographic features of Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina. Thus, the cartographic legacies of both Jacob Ziegler and especially Olaus Magnus had a conspicuous impact on Mercator’s map of Europe, which in turn influenced Danti’s Norvegia Gotiae in the Guardaroba nuova.

There is no direct information as to whether Duke Cosimo I and his political and economic invitees utilized the geographical information about the European north, but the opportunity was available during the turbulence of the Counter-Reformation and contradictions between the papacy’s and Charles V’s sacral and secular domains. This might also have informed Cosimo I’s considerations regarding his own economic maneuverings in Europe or his “cosmic” interests in northern curiosities, as geographically arranged in his own collection room, his Wunderkammer.

The Sala del Mappamondo at Palazzo Farnese, Caprarola (1572–1574)

The Sala del Mappamondo (Sala della Cosmografia) at the Palazzo Farnese is located ca. 50 km north of Rome. The palace was constructed during the 16th century by three generations of the papal Farnese family as their summer villa in the medieval village of Caprarola. The different construction phases of the edifice are still visible, from its pentagonal fortress-like lower floors to the Renaissance palace constructed in the 1550–1570s during Cardinal Alessandro Farnese’s lifetime (1520–1589) (Vecchi Citation1996, 8, 10).

The cycle of maps

The concept of the map cycle is explained in the reception room of the Sala del Mappamondo (Supplementary Fig. 3). Schulz (Citation1987, 101) cites a contemporary’s view that “the whole room is not only a wall atlas but the cosmological scheme with the Zodiac on the vault. The mural atlas consists of all known four continents on the side walls.” The oval Mappamondo, with female personifications of each continent, dominates the room on the wall opposite the main entrance. The mural map of Europa is situated on the window wall adjacent to the Mappamondo. Above the doors and windows there are portraits of five early explorers, and there are personifications of mythical figures along the frieze strip between the vault and the walls, after which appear several constellations of the Zodiac with names from classical mythology, such as Pisces and Aries (Vecchi Citation1996, 18; Quinlan-McGrath Citation1997, 1057–1059; Markkanen Citation2013, 76–78).

Symbolically, the mural maps in the Sala del Mappamondo reveal the cosmographical space linking the divine celestial sphere to earthly existence (Partridge Citation1995, 442). The enterprise probably reflected Cardinal Alessandro Farnese’s humanistic worldview and aspiration to attain the highest position at the Holy See after Pope S. Pius V (reigned 1566–1572). However, Gregory XIII (by birth Ugo Boncompagni) was elected Pope in 1572, before the cycle of maps of the Sala del Mappamondo could convey the spirit of the Late Renaissance and Mannerism (Quinlan-McGrath Citation1997, 1091–1093, 1098).

The European north in the Sala del Mappamondo

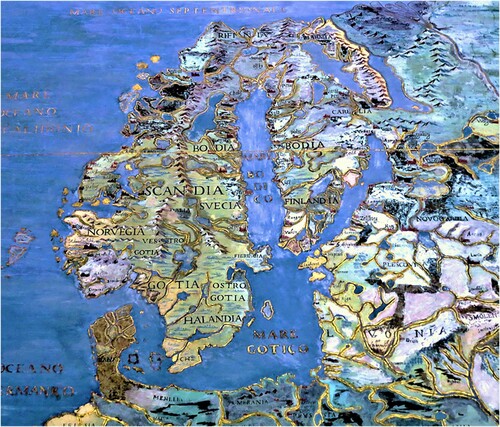

The European north on the mural map of Europa () is similar to the map of Norvegia Gotiae in the Guardaroba nuova (Supplementary Fig. 1). Both mural maps were painted on a conical projection in the upright position (with the central meridian approximately along the Bothnian Bay). However, unlike Norvegia Gotiae, the cartographical characteristics are less apparent on the mural map of Europa. The latter lacks a visible coordinate grid but is instead framed with degrees of latitude and longitude in the margins. The geographical features (coastlines, lakes, river valleys, and other topography) make the shape of the European north quite recognizable. Hierarchical lettering of the topographical landforms and regions alongside conventional place symbols with place names make the mural map of Europa one of the most informative and visually clear “scientific” sources of geographical knowledge about the European north in its time. Even though some of the place names were displaced or misspelled, the muralist’s pen had been in skilled hands. Even the smallest letters in the place names are still legible, although the European north is only a small part of the map of Europa.

Fig. 3. The European north, extracted from the mural map of Europa, ca. 110 × 100 cm (Photo: Arvo A. Peltonen, 24 January 2013) (Courtesy of the Palazzo Farnese and I Musei della Provinzia di Viterbo)

Instructive source maps and a skilled team were needed to prepare a fresco of the mural map of Europa’s quality. Cardinal Alessandro Farnese hired professionals to design and decorate the whole villa, including the Sala del Mappamondo. Mathematician and cosmographer Orazio Trigini de’ Marii sketched the mural maps, but it is not known who painted the Zodiac on the vault. Among the muralists, Giovanni Antonio Vanosino da Varese and his team were responsible for painting the wall maps (Vecchi Citation1996, 18, 20).

Source maps for the mural map of Europa

Kish (Citation1953) and Schulz (Citation1987) do not give any direct clues about the cartographic sources of the mural map of Europa and especially its northernmost regions. However, Kish (Citation1953, 53) assumes that cartographer de’ Marii and muralist Vanosino da Varese utilized Claudio Duchetti [Duchetto]’s map of Europe of 1571 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Duchetti’s map of Europe of 1571 might have served as a general source for the mural map of Europa. His 1571 map is the same as one in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), which is listed as having been made by Paolo Forlani [Forlano] Veronese. Forlani was, like Duchetti, an engraver and cartographer at Antonio Lafreri’s workshop (Woodward Citation1992, 57).

Antonio Lafreri’s atlas of 1572 might have had a major role in other ways in shaping the image of the European north, since some editions contained a patinated, quarter-size, copperplate printed folio (double sheet) of Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina, which certainly had a great impact also on Duchetti’s and Forlani’s 1571 map of Europe. Especially the northeastern part of the map, showing the peninsula of Finland, has a strong visual correlation with both Lafreri’s folio of the “Carta Marina” in the Roman Atlas of 1572 and the original loose sheets of the Carta Marina of 1539. Kish (Citation1953, 539) seems to be correct in concluding that the 1571 maps of Europe by Duchetti and Forlani influenced the muralists of Caprarola in their outline of the mural map of Europa.

However, the shape of the Scandinavian peninsula on the mural map of Europe at Caprarola () might also be traced “directly” to Gerard Mercator’s map of Europe of 1554 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Kish (Citation1953) did not consider the impact of Mercator’s map of Europe on the muralists’ work in compiling the mural map of Europe at Caprarola, and especially the “visual correlation” between Mercator’s Europe of 1554 and that of Duchetti and Forlani in 1571 (Supplementary Fig. 4). While it is apparent that Duchetti and Forlani based their map on Mercator’s map of 1554, the projections and positions of northern Europe differ slightly; Mercator located the European north obliquely, whereas Duschetti and Forlani placed it in an upright position, with the latter reflected in the position of the peninsulas of Scandinavia and Finland on the mural map in the Sala del Mappamondo.

However, like Norvegia Gotiae in the Guardaroba nuova, the mural map depicting the European north at Caprarola might be a hybrid of Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina (1539) and other sources. As I have shown in an earlier article, the northern part of the Baltic rim and Finland closely correlate with the Carta Marina in their visual details (Peltonen Citation2013, 102–105). The shape of Scandinavia on Mercator’s 1554 map of Europe also shares similarities with the outline Olaus Magnus gave to the peninsula on his Carta Marina.

Both Mercator’s 1554 map, and Duchetti and Forlani’s maps of 1571 via Mercator, clearly utilized Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina to sketch the shores and the interior geographical features (e.g., lakes and ridges) of the Baltic rim, especially the peninsula of Finland and its environs. Hence, plausibly, the northeastern part of the mural map of Europa at Caprarola reflects the “cartographic handwriting” of Olaus Magnus. However, as in the case of the Guardaroba nuova, it is difficult to trace the shape of western Scandinavia back to a single source; rather it is interpreted as an amalgamation of several sources. The slightly exaggerated undulation of the Norwegian coastline depicted on the mural map of Europa might have been the result of Giovanni Antonio Vanosino da Varese’s own artistic inspiration ().

Cardinal Alessandro Farnese and the European north

For sources of information about the European north during the Late Renaissance, there was a link between Cardinal Alessandro Farnese and the enclave of the Nordic Catholic exiles in Rome at the Santa Brigida Hospice, especially the Magnus brothers. The hospice had earlier also been a meeting point where experts on northern European issues met. For example, Jacob Ziegler who was in Rome in 1521–1525 met with the Magnus brothers and Norwegian archbishop Erik Walkendorf at the hospice (Nordenskiöld Citation1973 [1889], 60; Ehrensvärd Citation2006, 57; Mead Citation2007, 1785) (on the correspondence between the Magnus brothers and Cardinal Farnese, see Buschbell Citation1932). The meetings may explain why the geographical facts and shape of the European north became richer in geographical content and more accurate on the mural map of Europa at Caprarola.

Cardinal Farnese had a good command of European matter and even of global matters, including northern issues. His erudition and scholarly orientation were undoubtedly reflected in the cycle of maps at the Sala del Mappamondo. As to the European north, Lafreri’s cartographers would have greatly appreciated Olaus Magnus’s cartographic knowledge of the peripheral northern regions in the Late Renaissance. Cardinal Farnese and his group of muralists knew of the Italian cartographic business, especially Lafreri’s competent atlas team (Woodward Citation2007, 775–776).

The Terza loggia at the Vatican Apostolic Palace (1560–1565, 1572–1585)

The Terza loggia, on the third floor of the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace, is the third site discussed in this article as a place at which to study the map cycles and interpret the shaping of the European north and its context. Besides personal observations, useful literature includes the early surveys by Banfi (Citation1952) and Almagiá (Citation1955), and later by Schulz (Citation1987) and Fiorani (Citation2005; Citation2007).

The cycle of maps

Alongside the artistic and decorative aspects of the map cycle of the Terza loggia, the wall maps reproduced the “scientific” conventions of the Late Renaissance (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). In every fresco, the maps display the coordinate grid in conical or sinusoid projections with degrees and a scale. Most of the mural maps have a cartouche, which informs about the characteristics of the country or region, and sometimes about the wonders, mirabilia, of the far north.

The cycle of maps in the Terza loggia was the initiative of Pope Pius IV, the pope who dictated the final word at the Council of Trent in 1563. During his time, the west wing of the loggia was laid out as a cycle of maps. Pope Gregory XIII took responsibility for continuing the cyclical decorations for the north wing. Both popes supported the Counter-Reformation after the Council of Trent. The Terza loggia may be regarded as a monumental reflection of the ethos of the Counter-Reformation).

West wing

The construction and decoration of the third floor proceeded in two time periods between 1560 and 1582. The first phase was undertaken during Pius IV’s papacy in 1560–1565, when the west wing (Supplementary Fig. 5a), or la Bella Loggia, Loggia della Cosmografia, was under construction.

Information concerning the muralists who worked on la Bella Loggia is somewhat uncertain. The literature mentions that the cartographic designer of the gallery was Stefano [Étienne] [F]rancese. Banfi (Citation1952, 28; Citation1954, 34–36) assumes that this French cartographer was Stefano [Étienne] Tabourot, whom Abraham Ortelius included on his list of cartographers. Almagiá (Citation1955, 4, 27) mentions Stefano Tabourot as a cartographer who had participated in the project in the west wing, but he also cautions that the map designer might well have been Stefano Du Pérac (Étienne Du Pérac or Dupérac), also French at birth. Also, Fiorani (Citation2007, 807) emphasizes Stefano Du Pérac’s role as the cartographer responsible for the west wing, as also mentioned by Karrow (Citation1993, 34). Du Pérac (a kinsman of atlas “assembler” Antonio Lafreri) had easy access to the printed maps and engraved (etched) plates for the mural maps displaying the geographical characteristics of the European north.

The gallery consists of 12 arcades, each of which contains a mural map of a particular country or part of Europe, with a total of 13 maps located in the Ptolemaic sequence from west to east. No single mural map depicts the continent of Europe as a whole. The arcades showing (1) the Scandinavian peninsula (Scandia), (2) Muscovy (Moscovia), including the peninsula of Finland, and (3) “Greenland” (Gronlandia) are discussed in detail later in this article (in the section “Gronlandia and the mirabilia of the European north”).

Corner

In the corner is depicted a pair of massive hemispheres (ca. 400 × 400 cm each), planned by Egnazio Danti, indicating a holistic plan for joining the cartographical representations of the two wings (Supplementary Fig. 5b). The hemisphere in the line of the west wing comprises the continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa—the “Old World”—while the hemisphere in line with the north wing depicts the “New World” of southeastern Asia and the Americas, including “New Spain.” The shape of the European north is clearly visible in the “upper” part of Europe on the hemisphere with the Old World.

North wing

Regarding the second phase of the map cycle of the Terza loggia after the demise of Pius IV, his successor S. Pius V did not pay further attention to developing the Terza loggia. However, the next pope, Gregory XIII, took an active role in completing the initiative. During his papacy, the corner of the Terza loggia was finished, as was the north wing (Supplementary Fig. 5c). It is well documented which muralists took part in designing, decorating, and painting its mural atlas, which was divided into nine arcades with altogether 11 maps of Africa, the Americas, and Asia. Gregory XIII employed Egnazio Danti of Florence as the cartographer for the north wing, and the fresco painter Giovanni Antonio Vanosino da Varese led the team of muralists. In short, he hired the most professional specialists in wall maps in Italy. Plausibly, Vanosino had worked for Pius IV in painting the mural maps in the west wing 10 years earlier (Banfi Citation1952, 29–30). Unfortunately, during restoration in the late 19th century, substantial changes were made to the north wing, partially destroying the cartographical legacy of Danti (Banfi Citation1952, 29–30). Only two hemispheres painted by him are preserved in their original form.

The iconographic interpretation of the map cycle

The map cycle of the Terza loggia is similar to the map cycle of the Sala del Mappamondo at Caprarola, but celestial aspects of the cosmography are missing, for example the Zodiac. A map cycle also exists in Gregory XIII’s Sala Bologna, the office where he signed his decisions and declarations at his private quarters in the Apostolic Palace. The cycle of maps of the Terza loggia is a visual representation of the sacral space, emphasizing the strengthening supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church after the Council of Trent had been held and providing a spiritual foundation for the future (Schulz Citation1987, 106; Fiorani Citation2005, 243).

It is uncertain who commissioned the entire Terza loggia project as a cycle of maps, or which cartographer was responsible for designing the sequence of maps for the west wing. The group of muralists who worked on the west wing was responsible for depicting the European north for Pius IV and his eminent invitees at the Apostolic Palace before printed atlases became readily available. Banfi (Citation1952, 27) argues that the same cartographer devised the idea of the mural atlas for both the west wing and north wing. Furthermore, he suggests that the architect of the Apostolic Palace, Pirro Ligorio, might also have been the initiator of the map cycles for both wings and symbolically linked both wall atlases together by putting the hemispheres in the corner between the wings. Besides being an architect, Ligorio was a competent cartographer and therefore might have persuaded Pius IV to accept such a plan.

Source maps for the mural maps of the European north in the Terza loggia

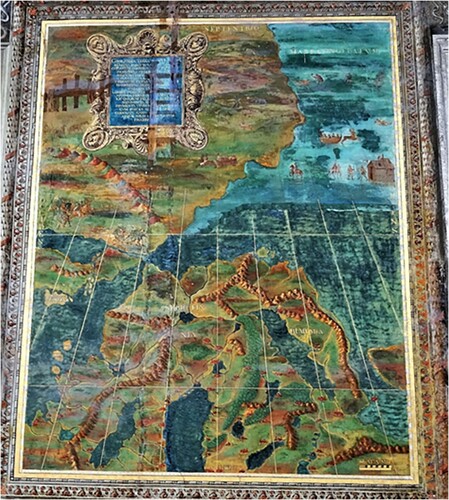

The European north does not appear as a regional entity in the map cycle in the Terza loggia as it does on Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina in 1539 or Egnazio Danti’s mural map of Norvegia Gotiae in the Guardaroba nuova. The European north is divided over three maps, with separate parts of Finland shown on the different maps: (1) the map of Scandia (Scandinavia) including the western coastline of Finland (Supplementary Fig. 6), (2) the peninsula of Finland in the upper northwest corner of the map of Moscovia (Muscovy) (Supplementary Fig. 7), and (3) Gronlandia e Biarmia, which shows the northernmost parts of the European north, including northern Finland (). This division of the European north may reflect earlier conventions based on the Ptolemaic Novae Tabulae (new folios that were not original to Ptolemy) (Nordenskiöld Citation1973 [1889], 26). Otherwise, it might not have been desirable for political reasons during the Counter-Reformation to emphasize symbolically the European north as a unified region after the “advent of heresy” (i.e., the spreading of Lutheranism).

Fig. 4. The mural map of Gronlandia e Biarmia (La Scandinavia settentrionale e Terre nordiche), 266 × 327 cm, in the west wing of the Terza loggia; the coordinate grid is visible in the lower part, but it seems to be missing in the upper part of the mural due to partial overpainting during subsequent restorations; the descriptive pictograms are scattered around the cartouche and on the right upper part of the mural map (Photo: Arvo A. Peltonen, 7 October 2016) (Courtesy of the Segreteria di Stato della Santa Sede and I Musei Vaticani)

The three frescoes were painted at approximately the same time in the early 1560s. There were only a few contemporary printed map originals or sketches at the cartographers’ and muralists’ disposal to copy and transfer onto the mural maps. The first monumental printed atlases started spreading throughout Europe 10 years later in the 1570s (Ortelius in 1570; Lafreri in 1572; and de Jode in 1578). The muralists, Egnazio Danti working in the Guardaroba nuova and Stefano Du Pérac working in the west wing of the Terza loggia, encountered the same problem of where to find credible sketches for the European north in the 1560s. By contrast, Orazio Trigino de’ Marii, working in the Sala del Mappamondo, and Stefano Buonsignori, working in the Guardaroba nuova, could utilize a wider selection of up-to-date printed maps from, for example, the atlases of the 1570s.

For the mural atlas in the Guardaroba nuova, Egnazio Danti appears to have derived his map of Norvegia Gotiae from Mercator’s map of Europe of 1554 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, it is evident that Mercator’s depiction of the European north would have had a high visual correlation with the three mural maps covering the northern parts of Europe in the Terza loggia (Almagiá Citation1955, 19, 21, 23, 25; Fiorani Citation2005, 109; Citation2007, 816). However, in referring to Richter & Nordlind (Citation1936), Almagiá (Citation1955, 19) emphasizes that the impact of Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina (1539) must have been significant in shaping Mercator’s ideas of northern Europe. As in the case of Danti’s Norvegia Gotiae in the Guardaroba nuova, the Scandinavian peninsula in the west wing of the Terza loggia appears to be, besides a slightly revised copy of the Carta Marina, an amalgamation of several sources, which Mercator had creatively joined together (; Supplementary Fig. 6).

Crane (Citation2002, 158–160) notes that Mercator compiled his map of Europe of 1554 from many sources. The sources were transferred, via Mercator’s “cartographic filters,” to the muralists working in the Sala del Mappamondo at Caprarola and in the Terza loggia. Fiorani (Citation2007, 110) notes that cartographers and merchants traveling in Russia might have had a role in describing the geographical features of Muscovy and the location of particular western Russian places in texts and maps. However, the topographical content and position of the peninsula of Finland was based on a generalized version of the Carta Marina. As to the mural map of Gronlandia, Almagiá (Citation1955, 25) suggests that Mercator’s 1554 map of Europe (Supplementary Fig. 2) provided the source material for this mural map, but with certain elements added from the Carta Marina.

Gronlandia and the mirabilia of the European north

In the west wing of the Terza loggia, the mural atlas conforms to the highest cartographical standards regarding the contemporary accuracy of the cartographic representations. However, there are two exceptions to the conventional principles of using color in symbols and signs. First, the conspicuous hue of the mural maps of Italy and the Holy Land is gold, like the mural maps of the same countries in the Sala del Mappamondo at Caprarola, thus representing their place as the pillars of Christianity. Second, the mural map of Gronlandia, referred to by Almagiá (Citation1955, 22) as La Gronlandia e la Scandinavia settentrionale (“Greenland and Northern Scandinavia”), originally did not have a title, but the cartouche text informs about the regions and their northern wonders and miracles, or mirabilia.

The Gronlandia mural map—tracing the impact of Olaus Magnus

The Gronlandia mural map () is located adjacent to the hemisphere of the Old World, and thereby occupies a prominent place in the west wing of the Terza loggia. The size of the mural map, 266 × 327 cm, is about the same as the other mural maps in the gallery (Almagiá Citation1955, Tavole [Plate]). It is an impressive wall map, and most of the details can easily be seen, although over the centuries the fresco has been exposed to variable weather conditions, fires, and people’s destructive touch. The west wing was restored three times before the 17th century but, as noted by Taja (Citation1750, 248) in his tourist guide for visitors to the Apostolic Palace, the cartouche of Gronlandia was partly unreadable in 1750 (Banfi Citation1952, 29).

Hence, observers seeking to interpret the Gronlandia mural map should consider possible changes made by the later restorers. The Gronlandia map might have been the creation of cartographer Stefano Du Pérac or possibly Stefano Tabourot (Banfi Citation1952, 23–24; Almagiá Citation1955, 4; Bratt Citation1958, 41). Although Giovanni Antonio Vanosino da Varese oversaw the team of fresco painters, it is difficult to assess how much of their original contributions are still visible.

The lower part of the Gronlandia mural map is a conventional cartographical representation of northernmost Scandinavia (; Supplementary Fig. 8). The region has a high visual correlation with map sheets B and C of Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina as to the geographical outline of the region northward from 65° N to the Arctic Ocean. The region depicted on the Carta Marina covers areas named on the map as Finmarchia, Scricfinia, Biarmia, and both Lappia Occidentalis and Lappia Orientalis, areas that include an abundance of pictograms and text descriptions (Supplementary Fig. 9). However, the Gronlandia mural map provides only a few geographical names: Gronlandia, Sf[c]ricfinnia, Ins. Pygmaeorum, and the Mare Congelatum. Inhabited places are shown with similar signs as on other mural maps, but without any place names. The lower part of the mural map does not have any imaginative pictograms, such as typically appear on sheets B and C of the Carta Marina (; Supplementary Fig. 9), but it has a clearly marked coordinate grid and other properties typical of “scientific” maps of the Late Renaissance.

The upper part of the Gronlandia mural map does not have longitudes or latitudes. This part of the map shows the “extreme” north outside the area covered by the Carta Marina. It may correspond to the southern limit of one of four “polar islands,” which Mercator depicted in a circular inset on his world map of 1569. Ortelius repeated the four polar islands on his map of the northern region in 1570, and included the statement “Pigmei hic habitant” (“Pygmies live here”). Mercator might in part have drawn inspiration for the polar islands from Ruysch’s 1508 map of the World (Crane Citation2002, 73, 159, 208–211). The landmass to the north on the Gronlandia mural map is shown surrounded by the Mare Congelatum and covered by Arctic ice. The Gronlandia mural map also shows a small island, Ins. Pygmaeorum, inhabited by pygmies (; Supplementary Fig. 8). Although Olaus Magnus cited ancient geographers and philosophers (e.g., Pytheas, Plinius, Solinus) when writing about pygmies in his Historia (Magnus Citation1555, Book II, Chapter 11B), the island of pygmies is not shown on the Carta Marina.

The upper part of the Gronlandia mural map contains further mystical elements, mirabilia, which are described in the cartouche (Taja Citation1750, 248; Almagiá Citation1955, 22). The cartouche describes the greenness of Greenland and the ability of the Biarmians and “Scrifinnii”Footnote3 (Skiing Sámi) to survive in extreme conditions, as they use rawhide garments, ride yoked deer-like donkeys scudding on the ice, move on snow using curious shoes, and eat dried meat, fish, and bird oil.

The text in the cartouche can be traced to Chapters 4 and 5 in Book I of Olaus Magnus’s Historia (Magnus Citation1555; Granlund Citation1976, 16–19). The cartouche underscores the mirabilia mentioned by Olaus Magnus in the title of the Carta Marina. One important detail mentioned by Olaus Magnus in his Historia (Magnus Citation1555, Book I, Chapter 4; Granlund Citation1976, 17) is that the governor of the Holy Town, Philippus Archintus, had received a message from Pope Paul III stating that he did not believe that Scricfinni could scud on snow so skillfully. This indicates that there had been some communication between the Farneses and the Magnus brothers earlier, showing that the Pope was curious about northern mirabilia (Buschbell Citation1932).

Gronlandia reflected the extreme north according to Olaus Magnus

Either Stefano Du Pérac or Stefano Tabouret, as well as Giovanni Antonio Vanosino, and/or a later restorer, had reproduced on the upper part of the Gronlandia mural map the classical concept of the extreme north, Ultima Thule, by giving it a cartographic form derived from Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina of 1539 and his Historia (Magnus Citation1555). The upper part is clearly a result of restoration or renovation because, for example, the coordinate grid is partly covered by newer paint (). Both Banfi (Citation1952, 30) and Almagiá (Citation1955, 19, 25) have suggested that one of the restorers—Giovanni Antonio Vanosino himself or Egnazio Danti, or else a much later restorer, possibly Filippo Agricola (1776–1857)—had missed the worn spots on the mural map. Stains on the upper part of the mural map make this part of the mural difficult to read today, but it is still recognizable. According to evidence provided by Agostino Taja (Citation1750, 248), the descriptive figures were certainly painted before his time, as they were already somewhat worn by the late 18th century.

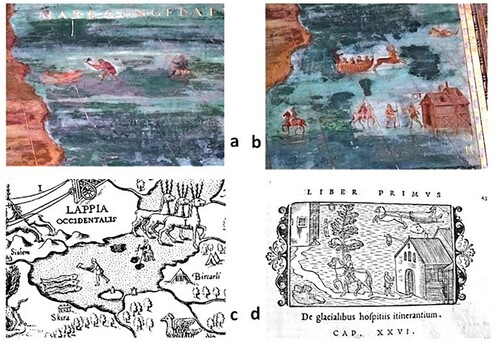

Almagiá (Citation1955, 24–25) identified parts of the Gronlandia mural map that had been copied from Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina. Further, besides the text of the cartouche, the sketches of most pictograms can be found as vignettes in the relevant chapters of Olaus Magnus’s Historia, as I have reported in an earlier article (Peltonen Citation2015, 56). However, the muralists transferred recognizable figures from northern Scandinavia from Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina (sheets B and C) to the mystical upper part of Gronlandia, since this was still terra incognita (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. 9). Thus, the muralists found a suitable place for the northern wonders and curiosities, the mirabilia, of the extreme north. The figures were conventional stereotypes of the European north that prevailed in the European political and cultural core during the Late Renaissance.

The Gronlandia mural map is cartographically exceptional. Throughout the centuries, symbol and sign systems on maps had represented notions of an “eternal summer.” However, Olaus Magnus on the Carta Marina, as well as the muralists of Gronlandia who borrowed from Olaus Magnus, employed an encyclopedic, cartographic language for both summer and winter phenomena, as well as a visual depiction of historical time flows and movements in a “topological space” (Supplementary Fig. 9). Like Olaus Magnus, either Stefano Du Pérac or Stefano Tabouret and Giovanni Antonio Vanosino da Varese depicted the winter activities of the Nordic (Arctic) peoples on ice and snow. Also the ice brink along the Mare Congelatum is visible on the mural map. Although some of the figures have become somewhat unclear due to wear and aging of the Gronlandia map, the winter activities depicted appear to include fishermen on the ice (Supplementary Fig. 8, box 6), a skier or skater on snow or ice (box 10), reindeer pulling a sled (box 7), and a rider and a hostelry on ice (boxes 8 and 9). It should be remembered that Olaus Magnus had positioned the descriptive pictograms (Supplementary Fig. 9) in northern Scandinavia (e.g., his fishermen on ice (box Bh), with an added explanatory note on the Carta Marina and in the commentary booklets Opera breve (Magnus Citation1539a) and Ain kurze Auslegung (Magnus Citation1539b); similarly, reindeer are depicted pulling a sled (box Fb). The figure of a rider and a hostelry on ice is not from the Carta Marina but from the commentary booklets and a vignette in Olaus Magnus’s Historia (Citation1555, Book I, Chapter 26) ().

Fig. 5. Details of the pictograms from the upper part of the Gronlandia mural map in the west wing of the Terza loggia at the Vatican Apostolic Palace, showing Arctic peoples engaged in activities during winter conditions: a) ice fishing; b) hostelry and winter activities on ice; the figures are comparable to those on c) the 1539 Carta Marina and d) the vignette in Olaus Magnus’s Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (Magnus Citation1555, Book I, Chapter 26) (Photos: Arvo A. Peltonen, 7 October 2016) (Courtesy of the Segreteria di Stato della Santa Sede and I Musei Vaticani, Uppsala University Library, and the National Library of Finland, A.E. Nordenskiöld Collection)

Besides the activities conducted in harsh winter conditions, the muralists emphasized natural, economic and military themes of the far north, such as reindeer husbandry, the hunting and milking of reindeer, and a people capable of warfare in all seasons. The pictograms show the reindeer being milked (Supplementary Fig. 8, box 1), spearmen traveling on reindeer and on foot (box 2), men hunting (box 3), a lynx chasing its prey (box 4), and reindeer pulling a cart (box 5). The analogous illustrations on the Carta Marina (Supplementary Fig. 9) are the milking of reindeer (box Eg), spearmen riding reindeer and marching (box Ci), hunting on snow (e.g., three pictograms scattered throughout sheet B), a lynx and its prey (box Eh), and reindeer pulling a cart (box Bi).

As I have reported in an earlier article, all figures on the Gronlandia mural map and the Carta Marina are found as vignettes in Olaus Magnus’s Historia (Peltonen Citation2015, 52–54). Thus, the muralists working on the Gronlandia mural map were familiar with both sources (). The text of the cartouche for the Gronlandia mural map informs about the hard life and hardy peoples living in the challenging Arctic conditions, thereby reemphasizing the mirabilia of the north to elites in the European metropolitan centers (Johannesson Citation1982, 232–236).

Mysteries: speculations

Why miraculous imagery?

Once can only speculate why the cartographically skilled muralists of the west wing of the Terza loggia still reproduced mythical stereotypes of the peripheral European north in the Late Renaissance, although only on the upper part of the mural map of Gronlandia. There might have been political connotations involved in the use of the figures, or they might simply have appealed to the artists. A later parallel is poetically described in a quotation by Jonathan Swift (Citation1733, 12), as pointed out by Helen Wallis (Citation1981, 106):

So geographers, in Afric-maps,

With savage-pictures fill their gaps;

And o’er unhabitable downs

Place elephants for want of towns.

However, during Olaus Magnus’s stay in Rome, his activity was focused on upgrading the image of Europe’s northern periphery to replace the still prevailing prejudices inherited from the classical historians and geographers of Antiquity (Grabe Citation1949, 31–33). It is well known that Olaus Magnus and his brother Johannes before him used their energy to persuade the Holy See and Catholic scholars to convert their prejudices to up-to-date knowledge about the European north, which was in the process of separating itself from the Roman Catholic Church (Collijn Citation1910; Granlund Citation1951; Grabe Citation1961; Johannesson Citation1982; Miekkavaara Citation2008a). Olaus Magnus’s own political program was to convince the recently converted Lutheran, thus heretic, but affluent, gallant peoples of the north to return to the Catholic Church. Hence, the Holy See should have taken a stand on returning the European north to its political and cultural fold, and even encourage some European nations to take military action against the heretical European north, especially Gustav Vasa’s regime of Sweden. Sketching a clerical policy for the Counter-Reformation was Olaus Magnus’s contribution to that program (Collijn Citation1910, 3–5; Granlund Citation1951, 42; Grabe Citation1961, 23–24; Johannesson Citation1982, 49, 193–194, 206–208, 215, 294–296, 298; Miekkavaara Citation2008a, 311).

The pictograms on the Gronlandia mural map may symbolically reflect Olaus Magnus’s own ambitions. However, the figures on the map might have aroused the curiosity of the sacral and secular potentates in the metropolis and helped to turn their minds from peripheral Arctic mysteries and mirabilia towards a more practical interest in the advantages of the north. The map symbols were iconographic keys for understanding the unique potential of the European north: fishing and the fur trade, the versatile use of reindeer, and the excellent mobility of warriors (i.e. spearmen) in all seasons, utilizing suitable means of transport, such as sleighs and chariots (Supplementary Fig. 8). Additionally, the harsh winter could have been viewed as an opportunity for having fun by the brave Arctic peoples, who chose to engage in activities such as skiing, skating, and reindeer riding. Olaus Magnus’s own “will” might indirectly have been present in the cycle of maps at the Terza loggia in the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace via these descriptive figures, whoever painted them. When gazing at the Gronlandia mural map, popes and other ecclesiastics were being invited to keep the northern issue in their minds.

Whose imagery?

There is still one other mystery related to the origin of the pictograms on the Gronlandia mural map. Ulla Ehrensvärd (Citation2006, 60) refers to an earlier cartographic depiction of the European north by Liévin [Livinus] Algoet in 1530, known from an imprint by Gerard de Jode in 1562. Algoet’s original map of 1530 had been lost, and only one double-sheet copy of de Jode’s 1562 map is preserved in the Bibliotèque nationale de France, Paris (Supplementary Fig. 10). The map contains many descriptive symbols that are thematically and visually similar to Olaus Magnus’s pictograms on the Carta Marina, as well as some figures that resemble the vignettes in his Historia, as I have mentioned in an earlier article (Peltonen Citation2015, 57–58). Ehrensvärd (Citation2006, 63) states: “It is usually assumed that Algoet copied Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina in 1539, but perhaps it was the other way around, that Olaus copied Algoet in 1530!” However, this does not seem plausible. A reduced version, dated 1570, of the 1562 map was published in de Jode’s atlas Speculum Orbis Terrarum (“Mirror of the World”) in 1578. In the cartouche of the reduced map, de Jode states that it was based on the “newest and most accurate description by Livinus Algoet” (these maps are discussed by Ginsberg (Citation2006, 122–125)). However, that map did not include any pictograms on the continental European north that were similar to the illustrations on Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina, but only some decorative symbols on the seas around the region: small and large sail boats and some whales typical of the printed maps of the Late Renaissance, which the Carta Marina includes too. Liévin Algoet, a calligrapher and secretary from Antwerp, would not have known the European north as well as did Olaus Magnus or his brother Johannes. This would seem to indicate that the pictograms were not found on Algoet’s 1530 map but were added to de Jode’s version of the map in 1562, but not to his condensed atlas version of 1578 (Karrow Citation1993, 35).

Ehrensvärd (Citation2006, 66) mentions that Mercator compared the maps of the European north by Liévin Algoet and Olaus Magnus and noted that “Olaus’s representation of the Norwegian coast was poor.” Thus, it is plausible that Mercator used Algoet’s outline of the Atlantic coast of the European north, but for the interior of the far north it seems that he derived geographical facts for his 1554 map of Europe (Supplementary Fig. 2) to a great extent from Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina. Likewise, the descriptive figures on Gerard de Jode’s map of 1562 appear to have been copied from Olaus Magnus’s works. Perhaps an amalgamation of information from either Algoet’s map or de Jode’s maps and the Magnus brothers’ oral information or map sketches partly explains the early versions of the European north on Mercator’s double-codiform map of the World, Orbis imago of 1538, and on his terrestrial globe of 1541 (Supplementary Fig. 11a–b) (Miekkavaara Citation2008b, 72). Mercator’s maps, as well as de Jode’s cartographic representations of 1562 and 1578, would have been at the disposal of muralists’ working in all three map galleries studied in this article.

Conclusions

In this article, I have discussed the shaping of the cartographic image of the continental European north in the mural atlases of the Late Renaissance (1560s–1580s) in three Italian galleries: the Guardaroba nuova in Florence, the Sala del Mappamondo at Caprarola, and the Terza loggia in the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace in Rome. Global trends in the Late Renaissance—explorations, the Counter-Reformation, and the humanistic ethos—enhanced the need for truthful information, including from the global peripheries. More accurate cartographical and geographical knowledge was required from “heretical” Scandinavia (Finland included) in order to define the ideological policies to be implemented by the ecclesiastic or/and secular potentates of the European core.

The “cycle of maps” concept has served as a revised iconographic model for organizing the observations. I have interpreted not only the mural maps, but also the entirety of the designed spaces—the galleries—in which the painted maps are located. The purposeful design of each gallery was meant to augment the interpretative power for understanding the iconographic role of the mural maps as crucial visual elements of the decor in the respective galleries. Thus, the “framing” of the mural maps spoke as meaningful locators of geographical knowledge, like decorative cartouches in the manuscript and printed maps, but in 3D form.

On all of the mural maps studied, the shape of the European north was approximately similar and up-to-date for its time. The cartographic accuracy of the painted wall maps was at about the same level as that of printed maps in atlases or on loose sheets at that time. Thus, the professional cartographers such as Egnazio Danti and Stefano Du Pérac and muralists such as Giovanni Antonio Vanosino da Varese followed and actively assessed contemporary developments in cartographic and geographical literature.

In the spirit of the Late Renaissance, some potentates gave priority to cartographic representations as decorative elements in their palaces in addition to the conventional iconography of the era. Patrons aspired to a high level of cartographic professionalism by employing qualified cartographers, painters and designers to provide accurate depictions of the cycles of maps in their edifices. The map cycles in the meeting halls or galleries were important forums for manifesting their political or ideological message and a means of persuasion among the eminent domestic and international invitees visiting their palaces. I have shown that Popes Pius IV and Gregory XIII and Cardinal Alessandro Farnese exhibited cartographical interest by religiously and spiritually manifesting the cycles of maps in the Terza loggia and the Sala del Mappamondo. The map cycle of the Guardaroba nuova was inspired by Duke Cosimo I’s aspirations to manifest the rationality of the cosmos: “The Cosmos is Cosimo’s Ornament” (Fiorani Citation2005, 33)

In all three galleries, the painted wall maps of the European north were inspired by Gerard Mercator’s map of Europe of 1554. Subsequently, Mercator’s map of Europe from the late 1560s became a “generic norm” for visualizing Europe. Thus, artists used Mercator’s printed map as their main source when painting the mural maps of the continent. In the 1560s and 1570s, the work of cartographers in Antonio Lafreri’s publishing house, such as Claudio Duchetti and Paolo Forlani, and plausibly also Gerard de Jode’s atlas enterprise, had a strong influence on the muralists’ cartographic choices. Olaus Magnus gave the regions of Scandinavia and especially Finland clear geographical shape, including the interior areas, which inspired Mercator and Italian cartographers in their depictions of the European north, increasingly an indispensable part of maps of continental Europe and outlying regions. Their contributions were an amalgamation of a cartographic “puzzle” in which the cartographic “handwriting” of many cartographers can be traced.

Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina was one of the most conspicuous authoritative guides shaping images the European north, and its idiosyncrasies can be found on all of the mural maps studied. The Carta Marina is among one of the rare maps to depict winter conditions and activities, movements, and the dynamism of time through map symbols in a single, holistic cartographic representation. Thus, the Carta Marina served as an example of cartographic creativity long after its own time.

SGEO_1865444_Supplementary_Material

Download Zip (10.2 MB)Acknowledgements

This study was completed with the support of Simo Örmä, curator of the Finnish Institute in Rome, who assisted me when contacting the Guardaroba nuova in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, the Sala del Mappamondo in the Palace or Villa Farnese in Caprarola, and the Terza loggia in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican. I also thank other personnel at the Institute and the galleries for facilitating my research. Special thanks are owed to retired librarian Leena Miekkavaara for in-depth discussions. I also thank to William R. Mead and the Ulla Ehrensvärd (both deceased), who, decades ago, persuaded me to consult the early maps. Additionally, I thank Guest Editor Michael Jones for encouraging me to submit my article to Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography.

Notes

1 Maps referred to in the text are listed in Appendix 1.

2 All potentates behind the map cycles were male (e.g., pope, cardinals, dukes).

3 The cartouche is worn, hence the name is unclear. Almagiá (Citation1955, 22) spelt it “Scrifinnii” in his interpretation of the cartouche. Olaus Magnus (Citation1555, Book I, Chapter 5) spelt the name as “Scricfinni.”

References

- Almagiá, R. 1955. Le pitture geografiche murali della Terza loggia e di altre sale Vaticane. Monvmenta Cartographica Vaticana (MCV) Vol. 4, 1–32, Elenco delle Tavole. Cittá Della Vaticana.

- Banfi, F. 1952. The cosmographic loggia of the Vatican Palace. Imago Mundi 9, 23–34.

- Banfi, F. 1954. The cartographer Etienne Tabourot. Imago Mundi 11, 34–36.

- Bratt, E. 1958. En krönika om kartorna över Sverige. Stockholm: Generalstabens litografiska anstalt.

- Buschbell, G. 1932. Briefe von Johannes und Olaus Magnus, den letzten katolischen Erzbishöfen von Upsala. Historiska Handlingar 28:2. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Casey, E. 2002. Representing Place: Landscape Painting and Maps. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Collijn, I. 1910. Olaus Magnus – Ett försök till karakteristisk och några önskemål: Föredrag hållet i Michaelisgillet den 18 dec. 1909. www.vöbam.se/texter/michaelisgillet.php (accessed 25 June 2020).

- Cosgrove, D. (ed.) 1999. Mappings. London: Reaction Books.

- Crane, N. 2002. Mercator: The Man who Mapped the Planet. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Della Dora, V. 2005. Towards a ‘3D understanding' of Renaissance cartography [Della Dora on Francesca Fiorani’s The Marvel of Maps: Art, Cartography and Politics in Renaissance Italy]. H-HistGeog, H-Net Reviews October 2005. www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=10923 (accessed 16 March 2015).

- Ehrensvärd, U. 1981. Decorative illustrations in early maps and atlases. Hakulinen, K. & Peltonen, A. (eds.) Papers of the Nordenskiöld Seminar on History of Cartography and Maintenance of Cartographic Archives, 119–131. Helsinki: Nordenskiöld samfundet i Finland.

- Ehrensvärd, U. 1987. Color in cartography: A historical survey. Woodward, D. (ed.) Art and Cartography: Six Historical Essays, 123–146. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ehrensvärd, U. 2006. The History of the Nordic Map: From Myths to Reality. Helsinki: John Nurminen Foundation.

- Fiorani, F. 2005. The Marvel of Maps: Art, Cartography and Politics in Renaissance Italy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Fiorani, F. 2007. Cycles of painted maps in the Renaissance. Woodward, D. (ed,) History of Cartography, Vol. 3, 804–830. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ginsberg, W.B. 2006. Printed Maps of Scandinavia and the Arctic, 1482–1601. New York: Spetentrionalium Press.

- Grabe, H. 1949. Det litterärä antik- och medeltidsarvet i Olaus Magnus patriotism. Stockholm: Caslon Press Boktryckeri.

- Grabe, H. 1961. Olaus Magnus: Svensk landsflyktning och nordisk kulturapostel i Italien. Svenska Humanistiska Förbundets skrifter 70. Stocholm: P.A. Norstedt & Söners Förlag.

- Granlund, J. 1951. The Carta Marina of Olaus Magnus. Imago Mundi 8, 35–43.

- Granlund, J. 1976. Olaus Magnus (1555): Historia om de nordiska folken I–IV. Östervåla: Gidlunds.

- Harley, B. 1989. Deconstructing the map. Cartographica 26, 1–20.

- Johannesson, K. 1982. Gotisk renässans: Johannes och Olaus Magnus som politiker och historiker. Stockholm: Michaelisgillet, Almquist & Wiksel International.

- Karrow, R.W. Jr. 1993. Mapmakers of the Sixteenth Century and their Maps. Chicago: Speculum Orbis Press.

- Kish, G. 1953. The mural atlas of Caprarola. Imago Mundi 10, 51–56.

- Lynam, E. 1949. The Carta Marina of Olaus Magnus, Venice 1539 & Rome 1572. Tall Tree Library Publication No. 12. Jenkintown, PA: Tall Tree Library Publications.

- Magnus, O. 1539a. Opera breve, laqvale demonstra, e dechiara, ouero da il modo facile de intendere la charta, ouer del le terre frigidissime di Settentrione: oltra il mare Germanico. Venice: Giouan Thomaso.

- Magnus, O. 1539b. Ain kvrze Avslegvng vnd Verklerung der neuuen Mappen von den alten Gœttenreich vnd andern Nordlenden sampt mit den uunderlichen dingen in land vnd wasser darinnen begriffen. Venice: Olaus Magnus Gotthus.

- Magnus, O. 1555. Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus. Rome: Ioannem Mariam de Viottis. http://runeberg.org/olmagnus/ (accessed 28 April 2018).

- Magnus, O. 1965 [1539]. Beskrivning till Carta Marina. Transl. G. Billsten & W. Billsten. Stockholm: Generalstabens Litografiska Anstalt – Kartförlag.

- Markkanen, T. 2013. Tähtien turvatit. Roma XI, 62–86.

- Mead, W.R. 2007. Scandinavian Renaissance cartography. Woodward, D. (ed.) History of Cartography, Vol. 3:2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Miekkavaara, L. 2008a. Unknown Europe: The mapping of the Northern Countries by Olaus Magnus in 1539. Belgeo 3–4, 307–324.

- Miekkavaara, L. 2008b. Suomi 1500-luvun kartoissa: Kuvauksia ja paikannimiä. Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö AtlasArt.

- Nordenskiöld, A.E. 1973 [1889]. Facsimile-Atlas to the Early History of Cartography with Reproductions of the Most Important Maps Printed in the XV and XVI Centuries. Introduction by J.B. Post. New York: Dover Publications.

- Partridge, L. 1995. The Room of Maps at Caprarola. The Art Bulletin 77(3), 413–444. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3046119?seq=1 (accessed 24 September 2019).

- Peltonen, A. 2013. Olaus Magnus ja Caprarolan Suomi. Roma XII, 96–109.

- Peltonen, A. 2015. Terza loggian porot ja muut Pohjolan ihmeellisyydet. Roma XIV, 41–59.

- Quinlan-McGrath, M. 1997. Caprarola’s Sala della Cosmografia. Renaissance Quarterly 50(4), 1045–1100. www.jstor.org/stable/30309404 (accessed 1 April 2019).

- Richter, H. & Nordlind, W. 1936. Orbis Arctoi nova et accurata delineatio auctore Andrea Bureo Sueco 1626. Meddelanden från Lunds Universitets Geografiska Institution, Avhandlingar III. Lund: G.W.K. Gleerups Förlag.

- Rosen, M. 2009. Charismatic cosmography in late Cinquecento Florence. Archives Internationales d’Histoire des Sciences 59(163), 575–590.

- Schulz, J. 1987. Maps as metaphors: Mural map cycles of the Italian Renaissance. Woodward, D. (ed.) Art and Geography: Six Historical Essays, 97–122. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Swift, J. 1733. On Poetry: A Rhapsody. Dublin: S. Hyde.

- Taja, A. 1750. Descrizione Del Palazzo Apostolico Vaticano. Roma: Pagliarini. http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:bvb:12-bsb10079785-2 (accessed 7 July 2018).

- Vecchi, M. 1996. Caprarola il sogno farnesiano. [Caprarola]: [publisher unknown].

- Wallis, H. 1981. Early maps as historical and scientific documents. Hakulinen, K. & Peltonen, A. (eds.) Papers of the Nordenskiöld Seminar on History of Cartography and Maintenance of Cartographic Archives, Espoo (Finland), September 12–15, 1979, 101–116. Helsinki: Nordenskiöld Samfundet i Finland.

- Woodward, D. 1992. Paolo Forlani: Compiler, engraver, printer or publisher? Imago Mundi 44, 45–64.

- Woodward, D. 2007. The Italian map trade, 1480–1650. Woodward, D. (ed.) History of Cartography Vol. 3:1, 773–795. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

1

Maps referred to in the text

Clavus, C. 1427. Europe ta-bula. (Helsinki: The National Library of Finland, A.E. Nordenskiöld Collection).

de Jode, G. 1562. Terrarvm Septentrionalivm Exacta Novissimaqve Descriptio per Livinvm Algoet [1530?]. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

de Jode, G. 1578. Septentrionaliv[m] regionvm Svetiae Gothiae Norvegiae Daniae. Speculum Orbis Terrarum. Antverp. (Helsinki: The National Library of Finland, A.E. Nordenskiöld Collection).

Duchetti [Duchetto], F. 1571. [Map of Europe.] (See Forlani [Forlano], P. 1571).

Forlani [Forlano], P. 1571. [La Descrittione dell’Europa / da Paolo Forlano]. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, BnF Gallica, Les Cartes. (Also attributed to Duchetti [Duchetto], F. 1571)

Gastaldi, G. 1568. La prima parte della descrittione del Regno di Polonia Venezia. (Reproduced in Lafreri, A. 1572).

Lafreri, A. 1572. Geografia Tavole Nove: Indice Delle Tavole Moderne di Geografia Della Maggior Parte Del Mondo Di Diverse Autori. Roma. (Helsinki: The National Library of Finland, A.E Nordenskiöld Collection).

Magnus, O. 1539. Carta Marina et Descriptio Septemtrionalivm Terrarvm ac Mirabilivm Rerum in eis Contentarvm Diligentissime Elborata Anno Dni 1539 Veneciis Liberalitate Rmi D. Ieronimi[o] Qvirini[o]: Patriarche Venetiai[e]. (Uppsala: Uppsala University Library, facsimile The National Library of Finland).

Magnus, O. 1572 [1539]. [Carta Marina 1539] (One-quarter size copperplate printed folio in Lafreri, A. 1572).

Mercator, G.1538. Double-cordiform projection of Orbis Imago. (Sint-Niklaas: Mercatormuseum).

Mercator, G. 1541. [Terrestrial globe.] (Sint-Niklaas: Mercatormuseum).

Mercator, G. 1554. Europae Desriptio [facsimile of 1572]. (Sint-Niklaas: Mercatormuseum).

Mercator, G. 1569. Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accomodata. Facsimile. Sint-Niklaas: Mercatormuseum).

Nordenskiöld, A.E. 1973 [1889]. Facsimile-atlas to the Early History of Cartography with Reproductions of the Most Important Maps Printed in the XV and XVI Centuries. Introduction by J.B. Post. New York: Dover Publications.

Ortelius, A. 1570. Septentrionalivm regionvm descrip. In Ortelius’s atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Antverpen. (Helsinki: The National library of Finland, A.E. Nordenskiöld Collection).

Ruysch, J. 1508. Nova et Viniversalior Orbis Cogniti Tabvla ex Recentibvs Confecta Observationibvs Ptolemaeus 1508 Romae. Tabvle XXXII in Nordenskiöld, A.E. 1973 [1889] Facsimile-Atlas to the Early History of Cartography with the Reproductions of the Most Important Maps Printed in the XV and XVI Centuries. Introduction J.B. Post. New York: Dover Publications.

Ziegler, J. 1532. Octava tabvla continent Cheronnesum. Schondiam, Regna autem potissima Norvegiam, Svegiam, Gothiam, Findlandiam, Gentem Lappones. Qvae Intvs Continentvr. Argentoratum [Strasbourg]: P. Opilio. (Helsinki: The National library of Finland, A.E. Nordenskiöld Collection).