ABSTRACT

The sharing economy (SE) literature has grown rapidly in recent years. The literature has focused on the diffusion of SE in metropolitan regions, while rural regions have been almost entirely overlooked. To fill this gap, the article examines the SE in a rural region in Norway to explore how it is framed by key actors in regional development at different spatial scales. The article treats the SE as a mechanism through which new knowledge, practices, and routines are developed. The analytical framework reveals how pro-SE and con-SE narratives co-evolve through both endogenous and exogenous factors within the region. The narratives are heterogenic. The pro-SE narrative articulates a viable source of economic growth in regions, whereas the con-SE narrative highlights a fear of undermining rural tourism and liberalization of labour. The article extends the SE literature by providing insights into how innovation paths relate to discursive processes in a rural context. The authors conclude that the SE can both increase positive development paths and obstruct regional development processes, depending on the strength of influence from contextual factors, namely policy regulations.

Introduction

The sharing economy (SE) has recently received increased attention from politicians, industry representatives, and governments (De Grave Citation2016; Frenken & Schor Citation2017; Frenken et al. Citation2019). The term ‘sharing economy’ is often used as an umbrella term (Netter et al. Citation2019; Gerwe & Silva Citation2020) to describe a phenomenon that features, according to Meelen & Frenken (Citation2015), ‘consumers (or firms) granting each other temporary access to their under-utilized physical assets (“idle capacity”), possibly for money’. Framed in diverse ways – through liberal approaches as well as conservative and critical representations – the SE is perceived in a multitude of ways. Until recently, the academic literature within social sciences has paid little attention to the role of SEs and their diversity, both in terms of how platforms emerge as new avenues of economic organization and how the ‘sharing turn’ (Grassmuck Citation2012) influences spatial dimensions. However, there is growing interest in the SE from various academic disciplines.

From our perspective, the SE incorporates innovative processes that can renew markets and connect actors in new ways. The innovation literature has argued that it is challenging to renew fundamental institutions because it would require a shift away from well-established organizational routines and practices (Nelson & Winter Citation1982). However, sharing is not a new phenomenon among friends and family (Belk Citation2014b), but the sudden rise of the SE has turned our attention towards ‘stranger sharing’ (Frenken & Schor Citation2017). The existing literature tends to highlight the SE as a material phenomenon in which sharing creates either avenues for business actors or prosperity, or challenges for policy actors. We believe this could be adjusted by looking at the SE as a relational phenomenon that is constituted by discursive conditions. By doing this, we answer the call for research on the SE that takes a multilevel approach (Cheng Citation2016) in order to understand the spatial dimensions. Furthermore, there is less knowledge about sharing economy in rural areas (Gyimóthy & Meged Citation2018; Agarwal & Steinmetz Citation2019). Lastly, Cheng (Citation2016) calls for research combining academic literature and grey literature (e.g. industry reports, conference papers) in order to obtain additional insights into the SE phenomenon.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the SE has been dominated by actor groups using socially progressive ‘feel-good’ rhetoric (Frenken & Schor Citation2017). This rhetoric from liberal policy agitators relies mainly on sustainability, growth, inclusiveness, and avenues for micro-entrepreneurs. In such a context, it is reasonable to question whether the SE is of exclusive interest to shareholders and their interests, and whether SE can be utilized solely by people in urban regions. We are not aware of any studies of how the SE is narrated, or framed in discourse, outside urban regions. In this article we explore this issue from a critical perspective in which key actors representing different spatial layers are researched.

Discourse is not expressed directly to us and is not reducible to grammatical or other linguistic elements, but rather concerns and sets the preconditions of what the narrative is about and what triggers its expectation (Neumann Citation2001). As our understanding of social phenomena influences how we talk about them and consequently how we behave, it is pertinent to study the content of discourse and narratives, as they offer relevant contexts for the creation of meaning and arguments. The framing of different dimensions of sharing economies and how they unfold in spatial contexts outside the big city centres and in rural areas can teach us important lessons about the role the SE plays in regional development. Furthermore, it is of relevance to understand how these processes develop and why different actors attribute different meanings to them. For example, we need to know more about why such rhetoric (tactics) may or may not be profitable for governments, multinational corporations (MNCs), and local business actors at different spatial scales. In such a context, it is relevant to study how the SE itself is framed, and by whom, as an opportunity or threat for renewal in rural regions.

This article’s research design treats the SE as a mechanism by which new knowledge, practices, and routines are developed and whereby innovative practices function as opportunities for industry sectors that arise from the SE. Drawing on a combination of qualitative methods, this article explores different narratives on the SE in a rural region. The interviews demonstrate that the SE is framed in diverse ways and varies substantially across spatial levels of society and across sector boundaries. As argued by Fløysand & Jakobsen (Citation2007) and Fløysand et al. (Citation2016), narratives and regional development can co-evolve through discursive practice. By addressing how key actors in regional development within policy and industry in Norway at different spatial levels narrate the SE, this article contributes to the literature on how the SE is framed at different spatial layers in Innlandet County in Norway (a description of the county as a study region is provided in the Methods section). We argue that the linkage between the rural features (economic specialization, low density) and practices of the SE creates an interdependency between the pro- and con-SE discourse. The article addresses the following research question: How is the sharing economy, as an innovative practice, framed by key actors in regional development within a rural region in Norway?

The next section contains a review of relevant literature on the SE and discusses how the SE is understood from a narrative perspective. The literature review helps us to develop the analytical framework of the article. The third section develops the methodology of the study, followed by the presentation of results. The empirical data is then discussed with the use of the analytical framework developed in the literature review section, and the concluding section summarizes the study and provides policy recommendations.

Literature review

Sharing economy and its regional dimensions

Several researchers have tried to conceptualize and define the SE (e.g. Botsman Citation2013; Belk Citation2014a; Frenken et al. Citation2015; Schlagwein et al. Citation2019) without managing to find a commonly agreed-upon definition. Most definitions include at least five characteristics: value creation, better utilization of underutilized assets, online accessibility, community, and reduced need for ownership (Agarwal & Steinmetz Citation2019). In this article, we follow the earlier definition of SE provided by Meelen & Frenken (Citation2015): ‘consumers (or firms) granting each other temporary access to their under-utilized physical assets (“idle capacity”), possibly for money’.

The literature on SEs is growing rapidly but has a strong bias towards cities and metropolitan regions where sustainability, participant behaviour, regulatory framework, business models, and conceptual studies have received most attention (Agarwal & Steinmetz Citation2019). Short distances and high population density make sharing especially easy in densely populated areas, and the phenomenon first emerged in cities, partly because of globalization, urbanization, and the financial crisis in 2008 (Habibi et al. Citation2017; Richter et al. Citation2017; Zervas et al. Citation2017; Šiuškaitė et al. Citation2019). There is less knowledge on the SE in Northern Europe and Scandinavia. Strømmen-Bakhtiar & Vinogradov (Citation2019) found that hotels in Norway had more guests in regions where Airbnb had expanded rapidly, compared with regions with lower Airbnb activity. By contrast, an examination of Airbnb in the county of Østfold in south-eastern Norway by Leick et al. (Citation2020) revealed that Airbnb rentals had a negative impact on traditional types of accommodation, which indicates that Airbnb is treated as a substitute for traditional accommodation. More knowledge is needed about the development of the SE in rural areas (Gyimóthy & Meged Citation2018; Agarwal & Steinmetz Citation2019; Strømmen-Bakhtiar & Vinogradov Citation2019). SE services are often more expensive and less available in sparsely populated areas, which underlines the importance of including geography and geographical principles (e.g. population density and distance decay) in the examination of the SE in order to understand its diffusion in space (Thebault-Spieker et al. Citation2017).

By developing a multilevel perspective on sharing, C.J. Martin (Citation2016) shows that the SE is framed mainly as an economic opportunity, wherein economic growth is promoted; underutilized assets, time, and skills can be used for monetary gains. More critical framings highlight the reinforcing of the neoliberal paradigm as an incoherent field of innovation and as creating unregulated marketplaces (C.J. Martin (Citation2016).

The SE poses challenges to existing legal frameworks when it does not fit directly into conventional regulatory frameworks, and questions of regulations, laws, and tax payment remain unresolved (Agarwal & Steinmetz Citation2019). One important element in this context is the role of public policy. Policymakers and other key actors play a pivotal role in creating and sustaining new industrial activities in the periphery (Isaksen et al. Citation2018). Still, conceptualizations of how regions develop have until recently paid little attention to the role of the state (MacKinnon et al. Citation2009). Thus, there is little evidence of insights into the scope for policy-supportive new developments in rural regions (MacKinnon et al. Citation2009; R. Martin Citation2012; Simmie Citation2012; Morgan Citation2013). Following Dawley (Citation2014), we argue that knowledge of the role of policy actors and interventions on multiple scales is vital in order to understand the emergence of new activities in rural regions.

According to Agarwal & Steinmetz (Citation2019), is it questionable whether conventional regulatory frameworks are the appropriate foundation for solving the policy problems associated with the SE or whether a completely new framework is needed for SE. Unequal conditions for platforms and industries, challenges with taxes, consumer protection, protection of labour, and privacy protection are identified as the most prominent challenges regarding the SE, according to Frenken et al. (Citation2019). They developed four policy options to meet these challenges: enforcement of existing regulations, toleration, new regulations, and deregulation. The latter two seem to be the most promising: the rules can be adjusted to fit the new practices that platforms have enabled by deregulation or by providing new regulations, which can contribute to a legalization of practices that were once illegal. However, Frenken et al. (Citation2019) argue that supporting a distinct policy option should take the sectoral context into account because each option will have different impacts depending on the stakeholders and sector.

Innovation and the sharing economy

Even though people have long been sharing available resources and values (Belk Citation2014b), the SE is considered to be an innovation (Guttentag Citation2015; Richter et al. Citation2017). Innovative technological platforms make ‘stranger sharing’ possible, as they provide trust-generating systems wherein the provider and customer can rate each other (Schor Citation2016; Schlagwein et al. Citation2019). The SE is often described as a disruptive innovation (Guttentag Citation2015; Muñoz & Cohen Citation2018; Grabher & van Tuijl Citation2020) in which market economies are potentially transformed (C.J. Martin Citation2016) and in which the focus is shifted from product innovation to platforms and their business models (Eckhardt et al. Citation2019). From our perspective, the SE is an innovative process that renews markets and connects actors in new ways. From the innovation literature, it has been argued that such processes are challenging because they require moving away from well-established organizational routines and practices (Nelson & Winter Citation1982). Fløysand et al. (Citation2016) argue that the literature stream on innovation and regional development has been particularly concerned with attempts to conceptualize how industries develop along different paths. However, the literature has been less successful in conceptualizing how sectors and their development paths relate to discursive processes (Iammarino & McCann Citation2013; Fløysand et al. Citation2016). Few studies have paid attention to innovation and the SE and its spatial implications, particularly when it comes to using discourse and narrative perspectives in an SE context.

Innovation in rural regions

Previous innovation research has often implied that rural regions lack the necessary capabilities for renewal based on their endogenous sources of knowledge, capital, and networks (Jauhiainen & Moilanen Citation2012; Tödtling & Trippl Citation2005; Eder Citation2019). However, definitions of ‘rurality’ vary widely, and the boundaries between rural and urban are not very clear. For instance, the term ‘rurbanization’ was introduced by Hompland (Citation1984, cited in Haugen & Lysgård Citation2006, 175) to describe a process in which rural and urban areas become more similar as a result of technological development, increased mobility, and rural tourism (e.g. second homes). However, population density, depopulation, small firms, remoteness, agriculture, and organizational thinness with little research and development (R&D) and low innovation capability are often used to determine whether a region is rural or urban (Rousseau Citation1995; Tödtling & Trippl Citation2005; Doloreux & Dionne Citation2008; Jakobsen & Lorentzen Citation2015; Eder Citation2019). Eder (Citation2019) calls for more explicit descriptions of peripheral regions to determine which regions are rural, both from a functional perspective (economic factors as weak human capital, thin institutional structures, and scarce links to markets) and from a geographical perspective (remoteness and poor access to economic core regions) (Jauhiainen & Moilanen Citation2012). There has been increasing attention given to innovation in rural regions (Doloreux & Dionne Citation2008; Eder Citation2019; Eder & Trippl Citation2019). Eder & Trippl (Citation2019) argue that more strategic efforts are needed to generate innovation in rural regions, which represents an alternative to the mainstream view of innovation within rural regions as experienced by economic agents (i.e. within economic geography). The innovation processes in these regions are often an outcome of compensation and exploitation practices, where the compensation strategy refers to compensation of local disadvantages, and where utilization of regional properties describes strategies for exploitation.

Theories of narratives and discourses

The literature on discourse theory contains two main categories of theories that can be observed within the social sciences. The first category, discourse theory, views the entire social world as a discursive construction. The theory was initially developed by Michel Foucault (Citation1991). The second category, critical discourse analysis, has grown out of the work of Fairclough (Citation1995) and Laclau & Mouffe (Citation2001). While Foucault’s theory claims that discourse is the fundamental structure and constitutes the basis for all types of social practice, the second category (critical discourse analysis) emphasizes changing paradigms of meaning, knowledge, and political claim-making. Neumann (Citation2001) and Laclau & Mouffe (Citation2001) stress the practices of ‘articulation’ of claims and see them as efforts to ‘fix meaning’ in political struggles. In this article, our discourse approach draws on Laclau & Mouffe (Citation2001) Neumann (Citation2001) and Fairclough (Citation1995). However, to capture the voices of regional renewal and politics, we find it useful to supplement their concept of articulation with the concept of narratives.

Rose (Citation2001, 138) defines discourse as ‘the process used to produce the meaning of a topic that inherently structures the perceptions and practices of the participants, although without their necessarily being conscious of being controlled’. Thus, narratives become the specific perceptions or modes of explanations located within a certain topic and promoted by an actor or group of actors (Rose Citation2001).

Analytical framework

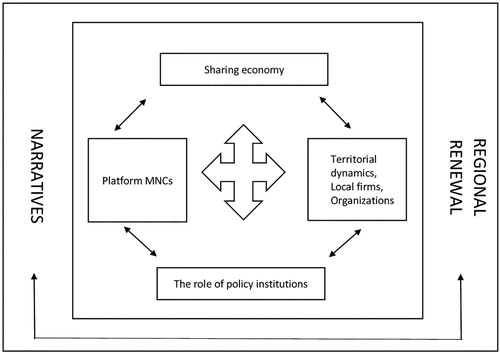

We have developed an analytical framework based on the literature cited in the preceding section. Under this framework, narratives encompass specific perceptions or modes of explanations promoted by stakeholders in a region regarding how SE practices relate to the broad field of regional development in terms of SE narratives ().

Fig. 1. Analytical framework of the nature of meetings between the sharing economy, policy, local firms, and platform multinational corporations, and narratives and regional renewal

The analytical framework includes the nature of the meeting between the SE and territorial dynamics, such local firm dynamics, platform MNCs, and regulative aspects, in a region. The narratives of SE surround these dynamics and are a ‘frame’ for how the SE develops in regions. These factors (the SE, territorial dynamics, policy, and platform MNCs) are linked through a complex process of co-evolution, in which different narratives on the SE influence actors that are central to territorial dynamics, organization, and policy within regions. Informed by the literature, we expect that narratives of SE will to a certain degree influence the perception of regional renewal within regions, depending on the regulative aspects and how the territorial dynamics co-evolve with different digital platforms.

Methods

Innlandet County as a study region

The rationale behind our selection of a study region was twofold. We were looking for regions characterized by being rural, but also by tourism because the SE has been most developed within the tourism sector. Innlandet County is located in south-eastern Norway and contains evident rural structures. It has a growing elderly population, low birth rate, long distances, a large number of employees within the public sector, and an industry structure dominated by agriculture, manufacturing, and tourism. Three regional centres in the county encompass a large number of public sector functions. Traditionally, regional policies have been important in order to stabilize the population and secure employment within small and distant municipalities in Innlandet County, especially in the northern parts.

However, Innlandet County has important strongholds because of its geographical location, especially during the winter season. Since the 1990s, rural mountain hinterlands close to major Norwegian cities have experienced second-home development that has outpaced residential building development by a factor of three to four. The skiing industry that expanded with the development of these second homes has created the most dominant growth impulse in the mountain regions in this period. Since the year 2000, the economic volume of the exogenous-to-the-region impulse has been in the order of EUR 25 billion (Arnesen & Teigen Citation2019). Thus, Innlandet County contains a variety of development processes. These include economic and employment stagnation in the northern part of the county, economic concentration in the most prosperous and populated part of the county, and a growing agglomeration of second homes in selected destinations (e.g. Sjusjøen, Hafjell, Trysil). All of the development processes create the basis for the empirical investigation of the narratives in the article.

Design and data collection

A combination of qualitative methods was chosen and data were collected through interviews and analysis of research and policy documents during winter 2019–2020. Our main data source was semi-structured interviews held individually with 13 key actors on national and county levels (). Participants from across Norway were interviewed because they were considered important to the development of the analytical framework conditions, regulations, and rights of employees. The interviewees from the county level prioritized the framework conditions, funding, or development in their region. An interview guide containing 14 questions was used in all interviews, but different follow-up questions were asked, and the interviewees were able to talk freely about the topics. Introductory questions about the organizations that the interviewees represented were followed by questions about how the interviewees defined the term ‘sharing economy’. The interviewees were also asked about how the sharing economy was mentioned and described in their organization. The interviews included questions on what challenges and possibilities the interviewees had experienced concerning the SE in the researched county and what experiences they had had with the SE, both personally and professionally. They were also asked about their perspectives on how the sharing economy influences industrial and commercial development, regional development, settlement, employment, tourism, and transportation in Innlandet County. All participants were interviewed by telephone and the interviews lasted an average of c.25 minutes. Data saturation was achieved by interviewing the main actors first and confirmed when additional interviews failed to provide additional information (Malterud Citation2012).

Table 1. Interviewed key actors

Additionally, a wide range of documents and ‘grey literature’ was collected () to provide additional insights into the SE phenomenon, as called for by Cheng (Citation2016). Document analysis is assumed to be applicable, especially when a single phenomenon is researched (Bowen Citation2009). The analysed documents are mainly government reports and web pages, and search terms such as ‘sharing economy, ‘platform economy, and ‘digitalization’ were used.

Table 2. Analysed documents

Data analysis

Thematic analysis is suitable when several methods are applied and when under-researched themes are investigated. To define the narratives, we followed Braun & Clarke’s suggestion of a six-phase thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke Citation2008 [Citation2006]). The data from the interviews were first transcribed word-for-word and imported to NVIVO (Bazeley & Jackson Citation2013), where they were analysed. We then read through all transcripts, with the aim of becoming familiar with the data and to acquire a thorough understanding of the material (phase 1). We looked for latent themes before generating some rough codes (phase 2) in order to sort the material (e.g. ‘challenges’ or ‘opportunities’). In phase 3, we searched for themes and sorted them in a thematic map. Examples of the themes we found are ‘regulations’, ‘undermining of existing industry’, ‘low local economic growth’, and ‘opportunities for economic growth’. We continued this analysis in phase 4 and ultimately identified ‘opportunities for economic growth’, ‘need for regulation’, and ‘undermining of existing industry’ as dominating narratives. We merged the two latter narratives into one narrative and named, defined, and refined the narratives in phase 5. Two emerging narratives became clear and we gave them the following descriptive designations: ‘a viable source of economic growth in the region’ and ‘undermining of rural tourism and liberalization of labour’. In phase 6, we analysed each of these narratives.

Defining narratives is a process of reflection. In our case, it posed some challenges due to the heterogeneity of actors and the actors’ position within the narratives. As the data analysis progressed, the dynamism of creating narratives as an analytical process was underlined, highlighting that the same actor could have different opinions and thus both support and be negative towards the SE as a phenomenon. Thus, one actor could play a role in more than one narrative.

Narratives of the sharing economy

Pro-SE narrative – a viable source of economic growth in the region

The framing of the SE in a rural region by the Norwegian Government and leading national agencies is relevant for this article because the national government is the main actor in innovation policies at the regional level (Wanzenböck & Frenken Citation2020). The Official Norwegian Report on the opportunities and challenges relating to the SE (NOU Citation2017:4) is strongly positive towards the SE. First, the report underlines how new technology facilitates the marketing of new goods and services. Second, the report highlights lower costs due to increasing competition. Third, the report shows that the SE could extend local markets in a global direction and even create entirely new markets: ‘In general, the sharing economy means that local markets are expanding and to some extent may become global. Furthermore, the rapid development of new sharing economy platforms will contribute to the creation of new markets’ (NOU Citation2017:4, 35–40).Footnote1

Overall, NOU Citation2017:4 concludes with the argument that the SE can increase the innovation capability in selected markets and sectors, and thus increase competition, lower prices, and provide better quality and choices for consumers. This view is largely echoed by the Norwegian Hospitality Association (NHO), the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, and Innlandet County:

The Norwegian Hospitality Association is positive towards the opportunities provided by the sharing economy. (NHO Reiseliv Citationn.d.)

The possibilities are at the centre for us. People can, through digital channels […], offer their services or goods in a much easier way. (Interviewee, Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation)

[…] small actors can also reach out to markets that are willing to pay, both by developing unique experiences and by adopting new technology. (Oppland fylkeskommune Citation2018, 34)

According to one interviewee, the regional industry association (see footnote 2) argues that the market for second homes in the region is the arena where the SE can be utilized in the future. This view was to a largely echoed by an interviewee from the social development section of Innlandet County Council: ‘When it comes to Airbnb, it gives a different opportunity for the international market to see how Norwegian people live’.

SE services such as Airbnb and Couchsurfing expand the market for accommodation if the demand is present. More visitors can increase spillover effects in the region. Other industries, such as sports shops or amusement parks, will see increased revenue when people visit the region, even if they spend the night with a local host accessed through Airbnb. Several interviewees reflected upon these developments as opportunities, as follows:

Tourists will spend money on experiences, trade, and services even if they do not stay at hotels. If SE can attract people who otherwise would not have been visiting the region, it would give added value. (Interviewee, Regional council 2)

If you prefer one-day accommodation with your family, […] I am sure you can find quite expensive offers out there. However, with such a price, I guess many of the family people would consider SE. (Interviewee, NHO Innlandet)

Rural regions have often been characterized by agriculture, and Norwegian farms have traditionally had a variety of structures (e.g. storehouses or barns). Given the direction agriculture has taken recently, these buildings have been underutilized. Sharing makes it possible to utilize them as accommodation and earn revenue from them. Regional actors emphasized the SE as a way to renew agriculture and farm tourism in rural regions: ‘SE can provide renewal of farm tourism’ (Interviewee, Innlandet County Council, social development section).

Despite a highly optimistic view of the SE, there is little evidence of coherence between the pro-SE narrative and regional policy strategies. The interview data revealed that none of the key regional actors had taken initiatives or implemented active policies to increase the embeddedness of the SE and turn it into a regional advantage. Furthermore, the interview data revealed there was a low level of understanding of the concept of the SE, even though some of the interviewees had utilized the SE themselves.

Thus, the pro-SE narrative is rather paradoxical. The data demonstrate that there is poor knowledge of the SE and few actors in the region have active strategies or policies directed towards better utilization of SE resources. However, regional stakeholders almost unanimously voiced an positive attitude towards the SE, thus highlighting that it constitutes an important dimension for further development of the region. We interpret these new opportunities as innovative practices that can contribute to regional renewal.

Con-SE narrative: undermining of rural tourism and liberalization of labour

Challenges concerning the SE are described in the former county of Oppland’s planning strategy for the period 2016–2020 as follows:

It is a challenge that this [the SE] is not regulated by laws and rules. This fact challenges existing industries such as the taxi and hotel industry. […] It is a challenge to find a balance between more effective utilization of resources and preserving good working conditions with regard to taxes, employment relationships, and responsibilities. (official document, Oppland fylkeskommune Citation2016, 16)

The difference in price between a traditional hotel and Airbnb accommodation is a major driver of increased local use of the latter. Moreover, a broad diffusion of SE can lower the incomes of local hotels and reduce economic growth in the local economy, and consequently reduce regional development. An interviewee from the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation argued as follows:

SE can lead to undermining of traditional sectors like hospitality or accommodation. […] A major shift from traditional ways of doing business towards the sharing economy, can lead to a strongly negative development, and in some cases, it can diminish local communities.

A global transformation away from transaction-intensive businesses and towards sharing economies can potentially have a range of effects. A representative of one of the political coalitions claimed: ‘SE can be good for the climate, bad for regional development. […] Firms within merchandise and manufacturing complain about re-using materials and goods due to the negative effects for local firms’ (Interviewee, Regional council 3). Furthermore, an interviewee from NHO Innlandet described potential challenges in the tourism sector that might arise due to a lack of regulations as follows: ‘If you have a firm that is organized by employees and you pay tax, and right across the street someone is renting out their houses over time to different tourists […] with different rules on tax payments […] of course it can be seen as a threat’.

The above-mentioned challenges were also described by the interviewee from the DMMO: ‘I have experienced that [the hotels] have been quite annoyed. However, I don’t think the local hotels have considered that actors who share their homes on Airbnb are direct competitors. Rather, the hotels are more concerned about the differences in terms and conditions.’ The statement supports a claim from The Norwegian Hospitality Association:

The fact that actors buy apartments and run them as hotels without being regulated like them is a threat towards hotel owners, but even more of a threat to local communities. […] If tourism is to grow as a business, we depend on harmony between locals and visitors. A city that has to be attractive to visit must also be attractive to live in. (NHO Reiseliv Citation2018)

The role of regulation involving platform actors is at the core of the con-SE narrative. SE practices lack guidelines on tax regulations and security of employment. The necessity of having regulations is highly evident in the Official Norwegian Report on the opportunities and challenges relating to the SE:

When transactions between individuals fall outside existing regulations, or it is unclear how such turnover should be treated in accordance to the regulations, difficult boundary delineations can occur. Consideration of competition compared with traditional business players, who must comply with current regulations in several different areas, thus becomes a relevant topic. (NOU Citation2017:4, 8)

In sum, even though the SE can be assumed to contribute to new opportunities for economic growth and renewal of rural districts, we identify a con-narrative in the region and among national actors. Furthermore, key stakeholders fear negative economic returns in the tourism sector. At the same time, and strongly related to the argument of fear of undermining local tourism firms, the narrative is clear on a call for new regulations adapted to the SE to protect the Norwegian model.

Discussion of the analytical framework

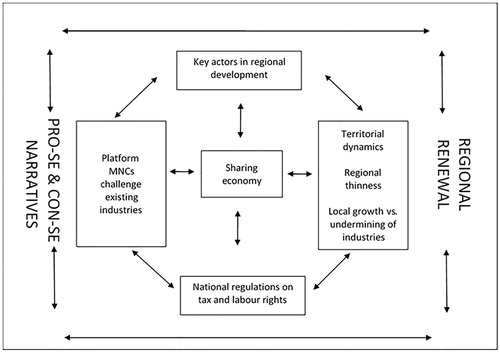

The analytical framework presented in shows how narratives and the SE can co-evolve through both endogenous and exogenous factors such as firms, actors, and contexts, and cut across different spatial levels. The analytical framework highlights how different contextual factors are linked to and influence the framing of the SE. In this section, we discuss and extend the framework by investigating the ways in which and the extent to which narratives of the SE are influenced by capital, firms, policies at different levels, people, and places. The analytical framework helps our understanding of the SE as a relational phenomenon highly influenced by contextual factors endogenous and exogenous to the study region (Innlandet County).

The analysis of the narratives, supported by empirical examples, illustrates the heterogeneous nature of the meetings between the SE and regional actors, as well as the surrounding factors that influence the framing of the SE within a rural region. The heterogeneity of the SE narratives means industry and policy actors can be divided into two groups. While the interviewed key policy actors in the region supported the emergence of the SE based mainly on the need for regional renewal and the potential for increased income for tourism firms, some of the key industry representatives viewed the SE as a threat to regional development because of its expected negative effects on local firms. The latter view has led us to understand the SE as an innovative practice in rural regions.

As highlighted earlier (in the Introduction and the section Theories of narratives and discourses), defining narratives is a process of transforming, selecting, and simplifying the empirical world into analytical categories, which makes sense in an academic study. We argue that the pro-SE and con-SE narratives provide categories of meaning that highlight the content, controversies, and different meanings of the SE for different regional development actors within the region. Moreover, based on insights from the relationships between actors, institutions, and narratives, we argue that prerequisites for substantial change in regions can exist where articulations mainly rely on discursive environments of pro-sharing narratives. This articulation can facilitate and enable renewal of tourism firms and local entrepreneurs, and thus push forward a new form of regional development in the SE, along with new policies that can attract new platform actors and services to rural regions. The strongly supportive attitude from key regional actors within policymaking can help to provide an avenue for positive change in regions. This is consistent with how C.J. Martin (Citation2016) frames the SE, as it reflects the finding by Strømmen-Bakhtiar & Vinogradov (Citation2019) that hotels in regions with high Airbnb activity had more guests than hotels in regions with lower Airbnb activity. By contrast, we argue that continuation and extension of the existing regional path occurs when the phenomenon of the SE is surrounded by con-narratives highlighting barriers to innovation that will obstruct a broad diffusion of the SE within regions. The critical statements expressed by the interviewed key actors in the tourism sector in the study region (Innlandet County) provide an example of voices in that can highlight the negative aspects of SE. The actors feared an undermining of existing industry in the region, such as happened in Østfold County, where Leick et al. (Citation2020) found that Airbnb rentals had a negative impact on traditional types of accommodation.

Dominant positions within the con-narrative are held by industry actors in Innlandet County. The interviewed industry actors claimed that characteristics of rural regions (specialization, low density, lacking capacity) hindered their willingness to share the positive attitude of SE demonstrated within urban regions. By contrast, rurality plays a different role in pro-SE narratives. Although it is similarly important as in the con-narrative, it is as a process that defines the need for new jobs and new development. In the theories of innovation at the regional level, structural factors have been recognized as barriers to innovation within non-core regions (Tödtling & Trippl Citation2005; Virkkala Citation2007; Grillitsch & Nilsson Citation2015; Isaksen & Trippl Citation2017). A number of theories focus on density and agglomeration, as competitiveness is achieved more easily in environments supported by such characteristics. More specifically, theories state that these processes grow more efficiently within cities (Glaeser Citation2011; Florida et al. Citation2017). Hence, the con-narrative of SE confirms theories within economic geography that highlight structural conditions as factors that hinder the emergence of innovation within rural regions.

We argue that pro-SE and con-SE narratives play an overarching role in the discussion of innovation practices in rural regions, as highlighted on the left side of the analytical framework in . In this article we contend that the role of narratives is vital because it includes different framings and thus provides context in a wider understanding of the SE. An analysis performed without taking into account the context and economic impact of SE would have been articulated as extremely positive through its favourable effects in cities and metropolitan regions. It is most likely that such an analysis would discuss the financial success of sharing economies, the beneficial conditions of platform performance, and urban growth. However, through the inclusion of narratives in our analytical framework, we highlight how territorial dimensions come into play: local hostility towards Airbnb spurs calls for regulations, and the fear of undermining local firm performance may hinder the innovation capability of the SE.

Traditionally analysed in an urban context with high population density, the SE has been a highly relevant alternative for tourists and people living in cities compared with traditional and regulated business actors such as firms. Introducing the SE in a rural region highlights important elements regarding both demand, due to the low population density in these regions, and ways it can challenge existing firms: introduction of the SE can undermine the few traditional firms left in the tourism sector in local communities. This is relevant, as it also points to lacking industry mix in Innlandet County. The specific rural dimension comes into play because Innlandet is highly specialized within a few sectors. For example, tourism is a fragmented sector comprising many small firms and strongly season-based activities. Local communities in the study region are dependent on the sector both directly (in terms of job creation) and indirectly (tourism involves purchases from services in general). These processes extend the economic and broader societal role of the tourism sector in the study region. Hence, the SE could lead to economic stagnation, which ultimately could force people to create new jobs or even to relocate. Regional specialization involves many resources in one sector and creates a vulnerability for firms, especially within resorts and services such as accommodation and transportation.

We argue that specific regional and rural aspects influence the con-narrative of SE as an innovative practice within Innlandet County. Hence, the con-narrative creates practices and opens up for attitudes of ‘holding-on’ to existing jobs instead of looking for new possibilities when SE as a new practice is introduced to the region. This specific vulnerability regarding both the threat of losing jobs and the perceived lack of probability for diversifying towards new jobs is a phenomenon more likely to be found in rural and dispersed regions than in urban regions (Virkkala Citation2007; Isaksen & Trippl Citation2017). Having strongholds within sectors containing regional labour that easily can be replaced by more competitive labour can be an important challenge for rural regions. To summarize, these factors can be particularly important for understanding how rural regions encounter new innovative solutions.

Furthermore, the con-narrative is strong not only on regulative concerns with respect to the threat of undermining local firms and especially tourist destinations, but also on taxes and funding of the welfare state. Our claim is that political bias influences how rurality can shape narratives that support or criticize SE. Liberal and conservative politicians at the local level can be more open to SE as an innovative practice, while more social-oriented politicians are prone to protect local companies and employment from external competition. The latter political position argues robustly for taxation and has strong trust in the Norwegian model, in which the ‘rules of the game’ of working life are settled. Innlandet County is a stronghold for Norway’ traditional Labour Party, supported by the Centre Party and with deep roots in their effort to balance regional disparities favoured by voters in Innlandet County in particular and in rural places more generally. We argue that political parties on the left in the political system are more eager to protect existing jobs in order to maintain rural development and sustain the existing industry mix as a defined aim in policies of regional development. Rural regions tend to have a political bias to the left and are inclined to develop strongly towards social-oriented political authorities. This can be supported by the fact that political parties on the left often aim for job security in general. At the same time, the political authorities are more prone to be supportive of local firms that are threatened from outside a region compared with political interests on the liberal part of the political spectrum. The question of tax on labour and regulations in general, concerning the relationship between labour and management, is central to such a discussion. In this respect, our analytical framework () illustrates the way policy influences the relationship between discourse and materiality and/or reality, understood as regulating the relationship between platform MNCs, local firms, and regional actors. As such, policy, and in this context, national regulations, should be considered crucial in guiding the interplay among the SE, renewal of regions, and regional development. Having a broad contextual understanding of regional renewal, and not isolating the SE as a phenomenon, can add value to our understanding of the way the SE is framed as an innovative practice in rural regions. In this respect, the spatial dimension is vital because only national policies can have the power to balance such policies towards the platform MNCs.

We argue that narratives contribute to a multidimensional understanding of the SE in rural regions, involving a multi-actor and multilevel approach that embraces different actors and firms. In addition to providing increased clarity regarding a range of arguments and positions, a narrative can influence the degree of renewal and innovation in rural regions through the way arguments are articulated and communicated.

The analytical framework illustrated in needs to be supplemented by a framework that highlights how the heterogeneity of narratives co-evolves with policy bias, territorial dynamics and regional specialization, and platform MNCs. shows the findings of our analytical discussion and empirical investigation, and shows dynamism between the factors and how different actors, spatial levels, and territorial dynamics co-evolve through narratives of the pros and cons of the SE.

Fig. 2. Dynamism among territorial dynamics, sharing economy narratives, and policy regulations in the study region, Innlandet County

A permeating factor in the discussion of the role of the SE as an innovative practice in rural regions is the question of regional renewal. The analytical framework seeks to establish a relationship between, on the one hand, pro- and con-SE narratives, and, on the other hand, the role of policies, capital, platform MNCs and local firms, people, and places. The framework also seeks to establish how these complex processes co-evolve through a dynamic relationship and end up as a specific output of continuation or change for rural regions.

Conclusions

In this article, we have researched the sharing economy in a rural region in Norway, namely Innlandet County, with the aim of contributing to the literature on how the SE is framed at different spatial layers by answering the following research question: How is the sharing economy, as an innovative practice, framed by key actors in regional development within a rural region in Norway? The SE literature within much social science research is framed as a disruptive agent of change, which itself can provide novel ways of organizing economic practice between producers and sellers of goods and services. This article offers an alternative approach by investigating the dominant narratives on the SE from a rural regional perspective and by paying particular attention to the relationship between dominating discursive practices and the SE as an innovative practice. Furthermore, this article informs the SE literature on rural regions about the role of the SE in a rural context by conceptualizing how innovation paths relate to discursive processes. The SE narratives in this article underlie a rather complex composition of arguments that point in different directions, and therefore the narrative approach has helped us to present two evident positions within the ‘chaotic’ landscape of actors, arguments, roles, and positions within the framework of the SE. Our analysis demonstrates that the SE is framed in diverse ways and varies substantially across spatial levels of society and across sector boundaries.

Through our analytical framework and empirical investigation of discursive processes, we have demonstrated that discursive practices relate in the following ways to innovation in rural region. The con-SE narrative increases the threshold (or hinders it) for innovation capability in rural regions by highlighting problematic issues of undermining existing sectors in regions as a result of the SE, and regulative dimensions are needed to balance the role of SE actors and more traditional firms. The con-narrative highlights important barriers to renewal. However, the analysis demonstrates that the pro-SE narrative lowers the threshold and facilitates innovative capability in rural regions by highlighting the enabling factors on which regional business sectors rely. Thus, the SE can work as a mechanism that can facilitate both expanding and declining paths in rural regions. The analysis demonstrates the mismatch between the potential of the SE narrated both at the national level and within the study region versus regional capacity or interest to deliver it. Furthermore, our analysis suggests that while there is greater awareness about the need to realize the potential of the SE in the larger metropolitan regions, this ‘outward orientation’ is not necessarily well understood and well translated into concrete action within the region, nor is it aligned to SE priorities in regional policies. Thus, we assert that there is a decoupling between the industry sectors in the region and the SE.

Hence, the linkage between the rural features (economic specialization, low density) and practices of SE creates an interdependency between the two discourses in which rural dimensions influence the shaping of the con-narrative. Processes outside regions more effectively influence the pro-narrative, as experiences are drawn from practices of SE in metropolitan regions. Based on this finding, we argue that the pro-narrative emerges as a result of experiences from urban regions, where it seems to be efficiently diffused through public media channels and mediators as a frame of reference for the rural regions. Thus, we highlight that economic and policy activities in a region can be considered as interwoven on different spatial scales and not exclusively confined to regional contexts.

A policy implication based on this study is the need to increase education on SE and the opportunities it can provide. Fair regulations adapted to the SE are required to protect the Norwegian model, not only to avoid the feared undermining of the existing industry but also to achieve the described growth potential in the study region, Innlandet County.

Even though we have combined different sources of information, the number of interviews undertaken represents a limitation of the study. Another limitation is that the results should not automatically be transferred to other contexts. Hence, there is a need for further studies of diffusion of SE in rural regions, the role of regulative aspects, and how SE is embedded in existing industrial structure and policies within different regional contexts.

Notes

1 All translations into English have been made by us.

2 To ensure interviewees’ anonymity, the names of the organizations marked with an asterisk in are not given.

References

- Agarwal, N. & Steinmetz, R. 2019. Sharing economy: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management 16(6): Article 1930002. doi: 10.1142/S0219877019300027

- Arnesen, T. & Teigen, H. 2019. Fritidsboliger som vekstimpuls i fjellområdet. Lillehammer: Høgskolen i Innlandet.

- Bazeley, P. & Jackson, K. 2013. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. London: SAGE.

- Belk, R. 2014a. Sharing versus pseudo-sharing in Web 2.0. The Anthropologist 18(1), 7–23. doi: 10.1080/09720073.2014.11891518

- Belk, R. 2014b. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. Journal of Business Research 67(8), 1595–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.001

- Botsman, R. 2013. The Sharing Economy Lacks a Shared Definition. https://www.fastcompany.com/3022028/the-sharing-economy-lacks-a-shared-definition (accessed 22 May 2019).

- Bowen, G.A. 2009. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal 9(2), 27–40. doi: 10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2008 [2006]. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77–101.

- Cheng, M. 2016. Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. International Journal of Hospitality Management 57, 60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.06.003

- Dawley, S. 2014. Creating new paths? Offshore wind, policy activism, and peripheral region development. Economic Geography 90(1), 91–112. doi: 10.1111/ecge.12028

- De Grave, A. 2016. So long, collaborative economy! https://www.ouishare.net/article/so-long-collaborative-economy (accessed 18 March 2021).

- Doloreux, D. & Dionne, S. 2008. Is regional innovation system development possible in peripheral regions? Some evidence from the case of La Pocatière, Canada. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 20(3), 259–283. doi: 10.1080/08985620701795525

- Eckhardt, G.M., Houston, M.B., Jiang, B., Lamberton, C., Rindfleisch, A. & Zervas, G. 2019. Marketing in the sharing economy. Journal of Marketing 83(5), 5–27. doi: 10.1177/0022242919861929

- Eder, J. 2019. Innovation in the periphery: A critical survey and research agenda. International Regional Science Review 42(2), 119–146.

- Eder, J. & Trippl, M. 2019. Innovation in the periphery: Compensation and exploitation strategies. Growth and Change 50(4), 1511–1531. doi: 10.1111/grow.12328

- Fairclough, N. 1995. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. New York: Longman.

- Fløysand, A. & Jakobsen, S.-E. 2007. Commodification of rural places: A narrative of social fields, rural development, and football. Journal of Rural Studies 23(2), 206–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2006.09.012

- Fløysand, A., Njøs, R., Nilsen, T. & Nygaard, V. 2016. Foreign direct investment and renewal of industries: Framing the reciprocity between materiality and discourse. European Planning Studies 25(3), 462–480. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1226785

- Florida, R., Adler, P. & Mellander, C. 2017. The city as innovation machine. Regional Studies 51(1), 86–96.

- Foucault, M. 1991. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of Prison: Hammondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Frenken, K. & Schor, J. 2017. Putting the sharing economy into perspective. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 23, 3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2017.01.003

- Frenken, K., Meelen, T., Arets, M. & van de Glind, P. 2015. Smarter Regulation for the Sharing Economy. https://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2015/may/20/smarter-regulation-for-the-sharing-economy (accessed 4 July 2019).

- Frenken, K., Waes, A., Pelzer, P., Smink, M. & Est, R. 2019. Safeguarding public interests in the platform economy. Policy & Internet. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.217

- Gerwe, O. & Silva, R. 2020. Clarifying the sharing economy: Conceptualization, typology, antecedents, and effects. Academy of Management Perspectives 34(1), 65–96. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0010 (accessed 15 March 2021).

- Glaeser, E. 2011. Triumph of the City. London: Macmillan.

- Grabher, G. & van Tuijl, E. 2020. Uber-production: From global networks to digital platforms. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 52(5), 1005–1016. doi: 10.1177/0308518X20916507 (accessed 15 March 2021).

- Grassmuck, V.R. 2012. The sharing turn: Why we are generally nice and have a good chance to cooperate our way out of the mess we have gotten ourselves into. Sützl, W., Stalder, F. & Maier, R. (eds.) Media, Knowledge and Education / Medien - Wissen - Bildung: Cultures and Ethics of Sharing / Kulturen und Ethiken des Teilens, 7–34. Innsbruck: Innsbruck University Press.

- Grillitsch, M. & Nilsson, M. 2015. Innovation in peripheral regions: Do collaborations compensate for a lack of local knowledge spillovers? The Annals of Regional Science 54(1), 299–321. doi: 10.1007/s00168-014-0655-8

- Guttentag, D. 2015. Airbnb: Disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Current Issues in Tourism 18(12), 1192–1217. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2013.827159

- Gyimóthy, S. & Meged, J.W. 2018. The Camøno: A communitarian walking trail in the sharing economy. Tourism Planning & Development 15(5), 496–515. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2018.1504318

- Habibi, M.R., Davidson, A. & Laroche, M. 2017. What managers should know about the sharing economy. Business Horizons 60(1), 113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2016.09.007

- Haugen, M.S. & Lysgård, H.K. 2006. Discourses of rurality in a Norwegian context. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 60(3), 174–178. doi: 10.1080/00291950600889947

- Hedmark fylkeskommune. 2016. Regional planstrategi 2016–2020. https://www.stange.kommune.no/getfile.php/13415719-1517473135/Filer/Stange/PDF/Planer/Planstrategi%202017-2021/Regional%20planstrategi%20for%20Hedmark%202016-2020%20%283%29.pdf (accessed 17 March 2021).

- Hompland, A. 1984. Rurbaniseringsprosessen: Bygdebyen og det nye Norges ansikt. AN 9/94. Oslo: Institutt for samfunnsforskning.

- Iammarino, S. & McCann, P. 2013. Multinationals and Economic Geography: Location, Technology and Innovation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Innlandet fylkeskommune. 2020. Vi bygger Innlandet: Kunnskapsgrunnlag til Innlandsstrategien – Langversjon. https://innlandetfylke.no/_f/p1/if435d888-6623-4d03-90e9-c068a021a63c/vi-bygger-innlandet-kunnskapsgrunnlag-til-innlandsstrategien-langversjon.pdf (accessed 15 March 2020).

- Isaksen, A. & Trippl, M. 2017. Innovation in space: The mosaic of regional innovation patterns. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 33(1), 122–140.

- Isaksen, A., Tödtling, F. & Trippl, M. 2018. Innovation policies for regional structural change: Combining actor-based and system-based strategies. Isaksen, A., Martin, R. & Trippl, M. (eds.) New Avenues for Regional Innovation Systems – Theoretical Advances, Empirical Cases and Policy Lessons, 221–238. Springer: Cham.

- Jakobsen, S.-E. & Lorentzen, T. 2015. Between bonding and bridging: Regional differences in innovative collaboration in Norway. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 69(2), 80–89. doi: 10.1080/00291951.2015.1016550

- Jauhiainen, J.S. & Moilanen, H. 2012. Regional innovation systems, high-technology development, and governance in the periphery: The case of Northern Finland. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 66(3), 119–132. doi: 10.1080/00291951.2012.681685

- Jesnes, K., Sletvold Øistad, B., Alsos, K. & Nesheim, T. 2016. Aktører og arbeid i delingsokonomien. Fafo notat 2016:23. https://www.fafo.no/images/pub/2016/10247.pdf (accessed 15 March 2021).

- Laclau, E. & Mouffe, C. 2001. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso Trade.

- Leick, B., Eklund, M.A. & Kivedal, B.K. 2020. Digital entrepreneurs in the sharing economy: A case study on Airbnb and regional economic development in Norway. Strømmen-Bakhtiar, A. & Vinogradov, E. (eds.) The Impact of the Sharing Economy on Business and Society: Digital Transformation and the Rise of Platform Businesses, 69–88. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lillehammer-regionen. 2018. Regional næringsplan 2018–2028. https://gausdal.custompublish.com/regional-naeringsplan.498645.no.html (accessed 17 March 2021).

- LO [Landsorganisasjonen i Norge]. 2016. Notat om ‘Samhandlingsøkonomienn’. https://www.lo.no/contentassets/342afff677f649aa8b60f324e1740954/samhandlingsokonomien-hefte-a4-nett.pdf (accessed 17 March 2021).

- MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., Pike, A., Birch, K. & McMaster, R. 2009. Evolution in economic geography: Institutions, political economy, and adaptation. Economic Geography 85(2), 129–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01017.x

- Malterud, K. 2012. Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 40(8), 795–805. doi: 10.1177/1403494812465030

- Martin, C.J. 2016. The sharing economy: A pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form of neoliberal capitalism? Ecological Economics 121, 149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.11.027

- Martin, R. 2012. (Re)placing path dependence: A response to the debate. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36, 179–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01091.x

- Meelen, T. & Frenken, K. 2015. Stop saying Uber is part of the sharing economy: What is being shared besides your money? https://www.fastcompany.com/3040863/stop-saying-uber-is-part-of-the-sharing-economy (accessed 13 May 2020).

- Meld. St. 19. (2016–2017). Opplev Norge – unikt og eventyrlig. Det kongelige nærings- og fiskeridepartement. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/95efed8d5f0442288fd430f54ba244be/no/pdfs/stm201620170019000dddpdfs.pdf (accessed 15 March 2021).

- Morgan, K. 2013. Path dependence and the state: The politics of novelty in old industrial regions. Cooke, P. (ed.) Re-framing Regional Development: Evolution, Innovation, Transition, 318–340. New York: Routledge.

- Muñoz, P. & Cohen, B. 2018. A compass for navigating sharing economy business models. California Management Review 61(1), 114–147. doi: 10.1177/0008125618795490

- Nelson, R.R. & Winter, S.G. 1982. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge, MA: Belknapp Press of Harvard University Press.

- Netter, S., Pedersen, E.R.G. & Lüdeke-Freund, F. 2019. Sharing economy revisited: Towards a new framework for understanding sharing models. Journal of Cleaner Production 221, 224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.225

- Neumann, I.B. 2001. Mening, materialitet og makt: En innforing i diskursanalyse. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- NHO Reiseliv. n.d. Delingsøkonomi: Politisk sak, overnatting, servering. https://www.nhoreiseliv.no/vi-mener/delingsokonomi/ (accessed 15 March 2021).

- NHO Reiseliv. 2018. Delingsøkonomi innen boligutleie – hva kan kommunene gjøre? https://www.nhoreiseliv.no/vi-mener/delingsokonomi/dokument/boligutleie–hva-kan-kommunene-gjore/ (accessed 15 March 2021).

- NOU 2017:4. Delingsøkonomien – muligheter og utfordringer. Oslo: Finansdepartment. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/1b21cafea73c4b45b63850bd83ba4fb4/no/pdfs/nou201720170004000dddpdfs.pdf (accessed 15 March 2021).

- Oppland fylkeskommune. 2016. Regional planstrategi 2016–2020 – Mulighetenes Oppland i ei grønn framtid. https://www.valdres.no/dbimgs/regional_planstrategi_2016-2020.pdf (accessed 15 March 2021).

- Oppland fylkeskommune. 2018. Regional plan for verdiskaping 2018–2030. https://innlandetfylke.no/_f/p1/ie9c7c52a-f6ff-477b-a7e2-1ffbfe5bcfb4/regional-plan-for-verdiskaping-2018-2030.pdf (accessed 22 March 2021).

- Richter, C., Kraus, S., Brem, A., Durst, S. & Giselbrecht, C. 2017. Digital entrepreneurship: Innovative business models for the sharing economy. Creativity and Innovation Management 26(3), 300–310. doi: 10.1111/caim.12227

- Ringsaker kommune. 2012. Strategisk næringsplan 2012–2020. https://www.ringsaker.kommune.no/getfile.php/2289302.1897.eusqftdxeq/Strategisk+naeringsplan+2012.pdf (accessed 17 March 2021).

- Rose, G. 2001. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Material. London: SAGE.

- Rousseau, N. 1995. What is rurality? Occasional Paper (Royal College of General Practitioners 71, 1–4.

- Schlagwein, D., Schoder, D. & Spindeldreher, K. 2019. Consolidated, systemic conceptualization and definition of the sharing economy. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24300

- Schor, J. 2016. Debating the sharing economy. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics 4(3), 7–22. doi: 10.22381/JSME4320161

- Sel kommune. 2017. Strategisk næringsplan for Sel kommune. Vedtatt i Kommunestyre 19.6.2017. https://www.sel.kommune.no/_f/p7/i92e337e9-e68e-4bb5-ab19-a8a3c1db1850/naringsstrategi-2017-2021-med-handlingsdel-2017-2018.pdf (accessed 17 March 2021).

- Simmie, J. 2012. Path dependence and new technological path creation in the Danish wind power industry. European Planning Studies 20(5), 753–772. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.667924

- Šiuškaitė, D., Pilinkienė, V. & Žvirdauskas, D. 2019. The conceptualization of the sharing economy as a business model. Engineering Economics 30(3), 373–381. doi: 10.5755/j01.ee.30.3.21253

- Strømmen-Bakhtiar, A. & Vinogradov, E. 2019. The effects of Airbnb on hotels in Norway. Society and Economy 41(1), 87–105. doi: 10.1556/204.2018.001

- Thebault-Spieker, J., Terveen, L. & Hecht, B. 2017. Toward a geographic understanding of the sharing economy: Systemic biases in UberX and TaskRabbit. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) 24(3): Article 21. https://doi.org/10.1145/3058499 (accessed 15 March 2021).

- Tödtling, F. & Trippl, M. 2005. One size fits all? Research Policy 34(8), 1203–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.018

- Virkkala, S. 2007. Innovation and networking in peripheral Areas—a case study of emergence and change in rural manufacturing. European Planning Studies 15(4), 511–529. doi: 10.1080/09654310601133948

- Wanzenböck, I. & Frenken, K. 2020. The subsidiarity principle in innovation policy for societal challenges. Global Transitions 2, 51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.glt.2020.02.002

- Zervas, G., Proserpio, D. & Byers, J. 2017. The rise of the sharing economy: Estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry. Journal of Marketing Research 54(5), 687–705. doi: 10.1509/jmr.15.0204