ABSTRACT

The aim of the article is to use survey evidence of school choice and educational attitudes in Sweden to explore how spatial polarization and liberal school reforms have affected the way parents, pupils, and school management think about education. The authors identify a possible polarization of attitudes in Sweden towards the importance of education in general and schools in particular, against the background of a highly liberalized school market, including school choice and rural-urban regional differences in the population’s education level. The basis for the analysis is TIMSS 2015 data for pupils in Grade 4 (age group 10–11 years). The results showed that localization of the school was a very important factor in school choice and that localization was more important than parental education and social class. Additionally, the authors tested the association between maths results and the variables attitudes, location, school, and household, and found that a household with a lower proportion of tertiary-educated parents in less central locations could make it difficult for pupils to perform well in mathematics. The authors conclude that in Sweden neoliberalization has been a geographically uneven process with a concentration in the metropolitan areas.

Introduction

In the last 30 years, while escaping from a very severe economic crisis in the early 1990s and entering a phase of strong income growth, Sweden has seen large increases in inequality (Pareliussen et al. Citation2018), an increasingly ethnically diversified population (Malmberg et al. Citation2018; Pareliussen et al. Citation2018), regional polarization in socio-economic composition (Nielsen & Hennerdal Citation2019), and higher levels of neighbourhood socio-economic segregation (Tammaru et al. Citation2015). At the policy level, these shifts have been accompanied by large-scale privatization of public services, conversion of public housing, and different neoliberal school reforms (Baeten et al. Citation2015; Dovemark et al. Citation2018; Hennerdal et al. Citation2018). Although welfare state provisions in the form of a social safety net have been kept in place, the development in Sweden in many ways mirrors processes observed elsewhere and thus can be put forward as an example of a generalized trend of neoliberalization (Van Zanten Citation2005; Harvey Citation2007; Theodore et al. Citation2011; Wiborg Citation2013). In the literature on these phenomena, much of the focus has been on mapping structural change in segregation patterns, spatial sorting, and changes in ownership. However, structural change is also accompanied by changes in the way people navigate their everyday life, such as their school choices and attitudes towards schools and education. Furthermore, it could be argued that an analysis of changes at that level could be as least as important as an analysis of structural trends. Thus, the aim of this article is to use survey evidence of school choice and educational attitudes to explore how spatial polarization and liberal school reforms have affected the way parents, pupils, and school management think about education in Sweden.

One background factor is the increasing concentration of individuals with higher education in Sweden’s metropolitan areas. Even though there has been a dramatic expansion in higher education in Sweden, there are still large regional and rural-urban differences in the proportion of the population that has a tertiary education. As demonstrated by Nielsen & Hennerdal (Citation2019), there has been an expansion in the population living in areas with a comparatively low proportion of tertiary-educated individuals. As a consequence, children in metropolitan areas are more likely to meet families and have peers with a higher educational background than themselves compared with children in more peripheral regions.

A second background factor is the increasing possibility for parents to select which school their children will attend. This has facilitated an increased sorting of children according to their background and abilities, and earlier studies of school choice suggest a positive correlation between, on the one hand, active school choice and being a privileged pupil and, on the other hand, an underprivileged pupil (Oría et al. Citation2007; E.K. Andersson et al. Citation2012). The combination of regional polarization in educational background, and increasingly selective school choice may constitute a challenge for clearly stated principles of educational equality in Swedish school legislation (Regeringskansliet Citation2010). Such concerns have not been lessened by indications that educational inequality is increasing in Sweden (Skolverket Citation2018; E.K. Andersson et al. Citation2019).

For the purpose of our analysis we take advantage of a source that hitherto has not been used to explore polarizing tendencies, the survey Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study by the IEA (Martin et al. Citation2016). Specifically, we draw on TIMSS 2015, which for Sweden was conducted by the Swedish National Agency for Education in 2015.Footnote1 The 2015 survey does not provide explicit geographical information but based on the survey questions it is possible to differentiate between different types of location. Moreover, the 2015 survey distributed to Swedish pupils included three special school-choice questions, which we had constructed for the Swedish version. These questions made it possible to identify pupils who had actively chosen schools, and subsequently to analyse how their school choice was related to background factors, educational attitudes, and outcomes. Our definition of active choice of school was that a different school was chosen from the closest one to the pupil’s home.

Based in the Swedish TIMSS 2015 survey of pupils, parents, and school principals of pupils in Grade 4 (age group 10–11 years), we identify possible polarizations of attitudes to schools in particular and to the importance of education in general – first, with regard to families that made an active choice of school and families who did not, and second, between pupils in different parts of Sweden. More specifically, we investigate both the frequency of school choice, here represented as the choice of a school that is not the nearest one (E.K. Andersson et al. Citation2012), and the attitudes of pupils and parents towards both the current school and the importance of education (Malmberg et al. Citation2014).

Our analysis encompasses four aspects. First, we analyse the regional gradient with regard to different indicators: parental education, social class, and ethnic background, as well as active school choice and parents’ ambitions for their children. Second, we analyse the determinants of school choice, with regard to not only the role played by location, but also the influence of parental education, social class, ethnic background, and parental ambition. Third, the relation between school choice and attitudes is analysed, both on the individual level (school choosers and non-school choosers) and by comparing school choice and non-school choice schools. Fourth, we analyse how mathematics results are influenced by parental background, location, school choice, and the composition of the school class in terms of education level, foreign-born parents, school choosers, and parental ambition. In this regard, attitudes towards learning mathematics is a good indicator, as all pupils have classes in mathematics and the subject is important for their further studies. According to Agirdag et al. (Citation2012) the subject itself is not important, but it is an indicator for any main school subject. We also analyse attitudes towards science as a taught subject.

To summarize, our analysis shows that in relation to schools, neoliberalism is unevenly distributed in Sweden, with a strong concentration in metropolitan areas. In these areas a large proportion of parents have a tertiary education, parental ambitions are high, and a high proportion of the children are active school choosers. High ambitions are mirrored in the school principals’ evaluation of parents’ commitments and expectations. School choice seems to foster an increased appreciation of the school on the part of the pupil who attends it, and that pupils’ school results can be improved if the pupils attend a school where there are many active school choosers. Thus, even though we found only weak evidence of polarization in the attitudes expressed by the pupils in Grade 4 themselves, we found relatively strong evidence of polarization in the valuations and attitudes to which they were exposed.

Background

The Swedish school system has changed dramatically since the beginning of the 1990s. At that time, decentralization transferred the responsibility for school provision from the national level to the municipal level, and marketization of the schools occurred too (Wiborg Citation2013; Dovemark et al. Citation2018; Hennerdal et al. Citation2018). The establishment of private schools, including for-profit schools run by private companies, was encouraged, and private schools were provided with full public finance. Although such marketization has taken place around the world (Van Zanten Citation2005; Butler & Hamnett Citation2007), Sweden is among the countries in which this process has progressed the most (Wiborg Citation2013). This change has provided parents with the right to choose their child’s school and has laid the groundwork for competition among schools in order to attract sufficient numbers of pupils (for further information on competition among schools, see for example Björklund et al. Citation2004; Bunar Citation2010). The right to choose a school is possible from preschool and onwards. In some municipalities, parents are obliged to choose a school, whereas in other municipalities parents only need to choose whether they want their child to go to a school other than the one to which they have been assigned, which most often is the nearest one. Yet another feature of the marketization of the school system is that schools are financed by vouchers granted to the pupil. Consequently, if a school fills all of its places it will be in a better position to finance itself compared with a school with unfilled places. Also, talented pupils represent a resource, in contrast to pupils who are low achievers and thus require higher investments for schools. However, in this system there is extra funding that schools can apply for, and some funding is allocated to schools in accordance with equity funding policies (Franck & Nicaise Citation2017). Even though marketization has taken place, government control of schools remains in the form of bureaucratic control systems (Rönnberg Citation2011). In 2015, 14.8% of the pupils in compulsory school, Grades 1–9 (respectively 7–8 years to 15–16 years), attended private schools (Sveriges Officiella Statistik Citation2020).

School choice and attitudes to education

Traditionally, in many countries, Sweden included, pupils have been assigned to schools based on distance, in order to ensure that their journey to school should not impact on their ability to attend and that it will be short, safe and convenient (Musset Citation2012). In many countries this is still the case or free school choice is combined with an assigned school, whereby the pupil will attend a particular school if they do not select another, public or private (free or tuition-based) school. Only a few countries do not assign a school based on geographical distance (Musset Citation2012), but regional or municipal regulations within countries may differ, as in Sweden. Some municipalities allocate schools primarily based on school choice, and children who have not made an active choice will be placed in schools where places are available, regardless of distance.

One result of the free school choice that is now in place in many countries, of which Sweden possibly has the most neoliberal model, is that more pupils choose a school other than their local one (E.K. Andersson et al. Citation2012), although such choices are highly dependent on the school system in the individual country (Musset Citation2012). However, it is still more common for an active school choice to be made for the equivalent of secondary schools than for primary schools, which are in focus in this study.

With regard to school choice in general, research has identified the following criteria among others as important factors affecting the choice of school made by parents: educational standard, proximity, academic record, the type of pupils already enrolled at the school, denomination, and whether the child anticipates that he or she will like the school based on its reputation (Denessen et al. Citation2005; Burgess et al. Citation2011). Whether a choice is made at all can depend on the importance parents attach to making a choice (cf. Reay & Ball Citation1997 on working-class choice) and the extent to which parents feel a responsibility to ‘micro-manage their children’s developmental and educational career’ (Barrett De Wiele & Edgerton Citation2016, 205) and whether they believe that ‘choosing a particular school can make an important difference in the life of a child’ (Bulman Citation2004, 514). Certain groups, usually assumed to be middle class, are understood to possess an educational advantage due to parental intervention in their child’s schooling (Butler & Hamnett Citation2007; Oría et al. Citation2007; Benson et al. Citation2015). This advantage is further enhanced by the marketization of education and subsequent increased parental influence in school choice (Butler & Hamnett Citation2007; Oría et al. Citation2007; Benson et al. Citation2015). Many parents who are inclined to act proactively in order to improve their children’s life opportunities rather than considering that equal opportunities should be offered to all children (Brown Citation1990; Barrett De Wiele & Edgerton Citation2016) usually have a similar background (Benson et al. Citation2015).

In the case of Sweden, a study of preschool choice for the preschool yearFootnote2 in two municipalities found that in both municipalities the importance of academic achievement of the school was negligible, but rather pupil composition influenced choice (Kessel & Olme Citation2016). The socio-economic composition of the school is important in that parents will opt for a school where other families’ children belong to the same socio-economic group as themselves, rather than basing their choice on the academic merit of the school (Elacqua et al. Citation2006; Benson et al. Citation2015; Kessel & Olme Citation2016). This in turn may mean that schools attract pupils from socio-economically strong groups with children who achieve better academic results. Differences between groups of parents are small. An exception is highly educated immigrant parents who are more likely to make an active choice than other parents (Van Zanten Citation2005; Kessel & Olme Citation2016). Rangvid’s study in Denmark showed that immigrant pupils who opted out of their assigned school had higher average grades regardless of what type of school they chose, whether it was another public or private school with a majority of Danish children or a private school with almost entirely immigrant pupils (Rangvid Citation2010). Immigrant parents with a low education level are less prone to make an active choice. To parents in the process of choosing a school for their child, the academic qualifications of the school appear less relevant than pupil composition (Kessel & Olme Citation2016). Swedish parents with a low level of education are likely to live near a school with a comparatively high number of pupils with an immigrant background but that such schools will be less attractive than other schools to those parents (Andersson et al. Citation2012). Furthermore, Swedish parents with higher education try to avoid such schools and rank schools with a higher socio-economic status substantially higher than other schools (Kessel & Olme Citation2016). In the case of Denmark, Rangvid (Citation2010) found that Danish pupils opted out of schools when the proportion of immigrant children exceeded 35%, in favour of schools with a smaller proportion of immigrant pupils. In the Swedish study, Kessel & Olme (Citation2016) argue that a compulsory school choice probably would not change anything as today there is no difference between groups of parents who choose schools. The group that is less likely to make an active school choice comprises parents with an immigrant background, but when they do make a choice, they actively avoid choosing schools with high socio-economic status (Kessel & Olme Citation2016).

Boone and Van Houtte’s attempt to find the mechanisms behind class differences in educational choice in the Netherlands by measures of cultural and social capital among parents could not successfully explain the differences (Boone & Van Houtte Citation2013). However, they found that school choices made by children were strongly influenced by their parents’ ambitions and societal views about different types of educational options.

Taken together, the above-mentioned studies clearly indicate that school choice is strongly influenced by social class, with middle-class families being particularly interested in using school choice in a strategic way. However, in general, the studies do not explicitly consider how geography might influence school choice.

The role of geography and location on school choice and attitudes to education

In our study we focused on pupils who either chose or did not choose another school than their nearest one. Bell uses geography as a conceptual tool in order to understand parental school choice from a geographical perspective (Bell Citation2007; Citation2009). Most importantly, geography has a decisive role in what schools parents will consider, some schools are out of range for space-based reasons and the social composition of the school often reflects the social composition of the geographical area in which the school is located (Bell Citation2007; Citation2009; Butler et al. Citation2007; Oberti Citation2007; Hamnett & Butler Citation2013). In addition, schools either are or are not located in neighbourhoods that parents like or dislike and are thus considered good or bad schools based on their geographical position or the information available to parents (Bell Citation2007; Citation2009; Butler et al. Citation2007; Oberti Citation2007; Hamnett & Butler Citation2013). Furthermore, geography may be negotiated, as a school in the near vicinity may not have the preferred qualities or curriculum, in which case, parents may opt for a more distant school (Bell Citation2007; Citation2009). Bell refers to how USA media showed that only a small fraction of parents who most needed to move their child to a better school took the opportunity to do so: the parents either chose to leave their children in failing schools or did not make any choice at all (Bell Citation2007). Having interviewed 48 families, Bell concludes that poor working-class parents did not choose between schools that ranged in quality, but rather chose from schools that were failing, that were unselective and free of charge. Similarly, middle-class parents made a choice between schools that were non-failing and selective (Bell Citation2009). Similar results were found in a study in Canada, where 47% of the parents of pupils in public schools did not actively choose a school but sent their child to the designated neighbourhood school (Bosetti Citation2004). Several studies revealed that the chances of poor children attending a good school were substantially smaller than for children from families that were better off and that their chances were not affected by the choices available (Elacqua et al. Citation2006; Burgess & Briggs Citation2010).

In Sweden, there are substantial local and regional differences regarding the possibilities to choose a school, irrespective of attitude to school and to education in general. In densely populated areas, the number of schools within geographical reach is higher than in rural areas, where the choice of schools is very limited (Skolverket Citation2012). Furthermore, in urban areas there is also a substantial difference between the number of schools with different socio-economic family types living nearby and the number and type of schools available to pupils based on the schools’ catchment areas (Oberti Citation2007; Burgess et al. Citation2011). Pupils from higher socio-economic groups most often live in close proximity to more desirable schools, which gives them better access to the school of their choice and possibly to higher quality education (Oberti Citation2007; Burgess et al. Citation2011). Popular schools may use distance to school as a criterion for admission when the number of applicants exceeds the number of places (Butler et al. Citation2013; Hamnett & Butler Citation2013). Similarly, Barthon & Monfroy (Citation2010, 179) refer to spatial capital as a form of capital that is unequally distributed among social groups and contributes to the reconfiguration of social inequalities in urban environments. They found that the place where people live influenced their possibility to choose schools, as access to schools varied in different neighbourhoods. In addition, mobility and the way it provided access to other neighbourhoods became a form of social capital to which individuals had unequal access (Barthon & Monfroy Citation2010, 179).

An ethnographic study of the identity work of children in Sweden and their social geographies revealed that there was a relation between school and neighbourhood, and that segregation between neighbourhoods increased because of school choice (Gustafson Citation2006). The children from middle-class areas considered the multi-ethnic neighbourhood areas and their schools as no-go areas and the children in the multi-ethnic areas did not have any relationships with wealthy Swedish children (Gustafson Citation2006). In a separate study, 21 interviews were conducted with families in two different areas of Stockholm – a middle-class area and a multi-ethnic area with primarily multifamily housing and low-income families – and the findings showed that choice of school was not made according to a rational choice model but that instead structural factors were of great importance (Skawonius Citation2005). Family resources were at play, most importantly cultural or informational resources. To a large extent, the choice process was similar to that seen in other countries (Bell Citation2007; Citation2009; Hamnett & Butler Citation2013). The process involved a lack of economic resources to pay for school travel, lack of time for parents to accompany children to a more distant school, lack of information about the range of schools available and what to do to get into them, which prevented families from choosing certain schools in contrast to families that had the necessary resources to make choices (Skawonius Citation2005). Transportation matters, as some parents can pay for or organize transportation for their children to a distant school, whereas others cannot (E.K. Andersson et al. Citation2012). Parents who have the necessary means are prepared to transport their child to a distant school if the quality of that particular school outweighs the qualities of a closer school, otherwise proximity may be the most important factor (Bell Citation2009). If transportation is not an issue, then geography may not matter and either the child’s preference or parents’ preference for an equally suited school will be considered.

Attachment to place is evident in some studies of school choice. For families that have a strong attachment to place, such as a rural area (Walker & Clark Citation2010; Bagley Citation2015) or a specific neighbourhood in a city (Waslander et al. Citation2010), the importance of choosing the local school may override other issues in their choice process. In rural areas, this can lead to support for a village or town school, and in both rural areas and cities it can help families to show support for the area. Thus, we can assume that pupils in such schools may be prouder of their school than are other pupils.

The above-cited studies serve to clarify the importance of geography for school choice and how geography and social class may interact. To summarize, examples include differential mobility across social groups, residential sorting that influences the social composition of local schools, a preference for local schools, and a lack of alternatives in sparsely populated areas.

Data and methods

For this article, we draw on Swedish data for pupils in Grade 4 obtained from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study survey conducted in 2015 (TIMSS 2015) (source: see footnote 1). TIMSS 2015 was a large-scale study conducted in 56 countries by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). In addition to a test of how well the pupils in Grade 4 in the participating schools performed in mathematics and science, the pupils, their teachers, school principals, and parents were asked to fill in questionnaires. The answers to those questionnaires are the data used for this article.

In Sweden, 144 sampled schools with a total 4142 pupils in Grade 4 (most of whom were born in 2004) participated in the study conducted in March 2015 (source: see footnote 1). The participating classes were selected using a two-stage random sample design, where the schools were randomly sampled in the first stage, and one or more intact classes in those selected schools were sampled in the second stage (LaRoche et al. Citation2016).

School choice

In this article, the definition of school choice is based on two questions in the questionnaire prepared by the Swedish TIMSS team, which are specific questions for the Swedish survey and are based on an earlier survey reported by Malmberg et al. (Citation2014). The first question in the Swedish survey was ‘Have you actively chosen the school your child attends?’Footnote3 and was intended to reveal parents who considered choosing a school instead of letting their child be admitted to the school closest to home according to the municipality. In Sweden, the lower the child’s age, the more common it is for the child to attend a school close to home. In our study, the pupils were in Grade 4 (i.e. they were relatively young). The second question used to construct the school choice variable was ‘Are there any other schools located closer to home than the one your child attends?’ The purpose of the question was to identify whether parents refrained from choosing the closest school in order to secure a place for the child at their preferred school farther away. In this context, we defined school choice as to have actively chosen a school that is not the closest one. Strictly speaking, it meant that parents had taken a decision to forgo sending their child to the school closest to home. Moreover, the definition implied that active choice of school was defined as a physical act, not as a statement about how parents self-evaluated their behaviour in relation to school selection. Essentially, this meant disregarding those living close to a school that would otherwise have been counted as choosing that school, but we wanted to include parents for whom an active choice regarding school involved their child attending a school farther away than the nearest school. In this article, parents who opted not to choose the closest school are considered the choosers for whom we expected attitudes to differ from parents whose children attended the school closest to home. We assume that parents who choose a school close to home probably give priority to their housing and neighbourhood preferences, as well as to a school location that fits with their financial resources, and they probably make more class-based decisions than those who give priority to education. However, we do not examine this assumption in this article. The response rate to the questions used to construct the school choice variable differed when neither of the parents were born in Sweden (74%) in comparison with the cases in which at least one of the parents was born in Sweden (89%). It should be noted that the questions regarding parents’ active choice of school were only included in the Swedish TIMSS survey. The inclusion of the school-choice questions in the TIMSS survey offers a valuable opportunity to analyse how school choice relates to the attitudes of parents, pupils, and educators, as well as to explore regional patterns in school choice in relation to educational attitudes.

School characteristics and pupil background

Another variable used in the analysis was if neither of the children's parents was born in Sweden. Questions regarding the origin of the parents were included in both the pupil questionnaire and in the parent questionnaire in TIMMS 2015 and for this article, we draw on the findings relating to the parent questionnaire, with one exception: in cases when parents did not answer the question about their origin, we used the answers from the pupil questionnaire. In this way, we were able to account for the parents’ origin for 99% of the 4142 pupils; 18% did not have a Swedish-born parent.

Two additional variables about the pupil background were used to collect data from the questionnaire for parents: one was to determine whether at least one parent had completed tertiary education or higher, and the other was to determine the highest social class (i.e. salariat) of either parent according to the three-class version of the European Socio-economic Classification (ESeC) (Harrison & Rose Citation2006), to which a fourth class (Class 10, Unemployed) may be added, according to Harrison & Rose (Citation2006, 9–10). The four classes in ascending order are: Unemployed, Working Class, Intermediate, and Salariat (Harrison & Rose Citation2006). In the questionnaire, the responses Service or Sales, Craft or Trade, Plant or Machine Operator, and Labourer were jointly termed Working Class, the responses Small Business, Clerical, Skilled Agricultural of Fishery, and Technician were jointly termed Intermediate, and the responses Manager and Professional were jointly termed Salariat. If the answer was that at least one of the parents was unemployed, we set the answer as Unemployed.

An important focus in this article is the type of area in which the school is located. The data regarding location was obtained from the questionnaire filled in by the school principals. The multiple choice question: ‘How would you describe the area in which your school is located?’ had the following optional answers: (1) Urban, densely populated, (2) Suburban, on fringe or outskirts of urban area, (3) Medium-size city or large town, (4) Small town or village, and (5) Remote rural. The results are shown in . The variable named ‘region’ was a summary of the school principals’ perceptions of the location of their school, which can be seen as corresponding in broad terms to a classification of municipalities made by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner Citation2019).

Table 1. School location area type, frequency and percentage

In cases when the pupils’ responses did not have values for key variables, such as the type of area and whether their parents had actively chosen their school, the data were excluded, leaving data for 3403 pupils (82%) in 140 schools in the dataset used for analysis in this article ().

Table 2. The study variables

Results

First, we present out results relating to the location of the school together with a number of variables: active school choice, mean of school choosers in the school, and parents’ education, as well as the pupils attitudes towards mathematics and science. Second, we present the determinants of school choice, and third, we present the results of attitudes towards mathematics from regression models, including the different locations and variables for individuals (parental background) and variables for schools. Statistical details relating to the results presented in this section are available online at Stockholm University research repository.

Regional polarization

A particular advantage of having access to the information on both school choice and location is that we could control for location (i.e. area type). Usually, there is a strong correlation between highly educated parents and school choice (Andersson et al. Citation2012) but since parents with high education live in areas with a wider school choice, namely urban areas, the correlation might be spurious. In this article, we consider the traditional determinants of school choice to discover geographical differences that are due to location, not to parents’ education or social class. First, we comment on location.

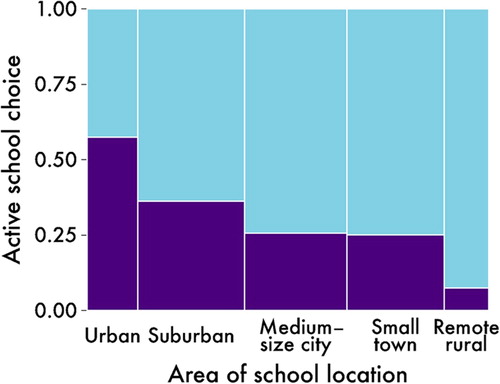

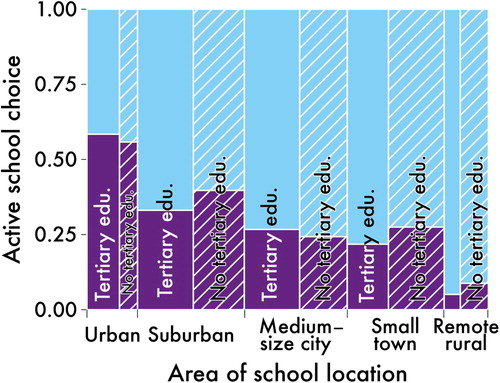

The proportion of parents who made a school choice (i.e. who chose a school other than their nearest school) was higher in urban areas where the number of schools to choose from was higher than in medium-size and small towns and rural areas, which generally have fewer schools (). We found a sharp regional gradient with regard to the extent to which parents exercised school choice, ranging from only 7% in remote rural areas to 57% in densely populated urban areas.

Fig. 1. Proportions of parents who answered that they had made an active school choice for their child (column widths proportional to number of responses)

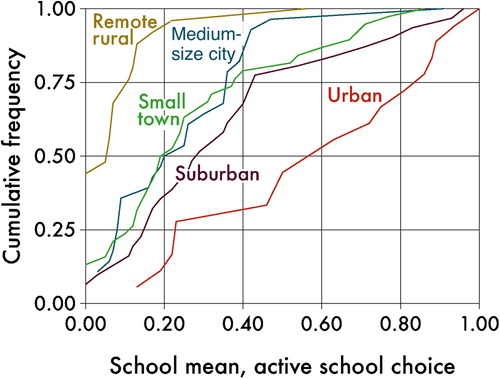

Our analysis of the proportion of active choosers among the pupils in the classes and schools included in the TIMSS surveyed revealed great variation between schools in different areas (). Schools in urban areas had a much larger proportion of school choosers (mean c.57%). In small villages and remote rural areas, the mean of school choosers was less than half of that in urban areas. shows that for the area types medium-size city, small town, and suburban, c.75% of pupils (cumulative frequency of pupils) attended schools where less than 40% of all pupils were active school-choosers. For remote rural area types, 75% of pupils attended schools where less than 10% of all pupils were school choosers. Additionally, 75% of pupils in urban area types attended schools where more than 80% of all pupils were active school-choosers ().

Fig. 2. Cumulative percentage for the different area types; content of active school choosers per school, ranging from lowest to highest percentage of choosers per school in the area

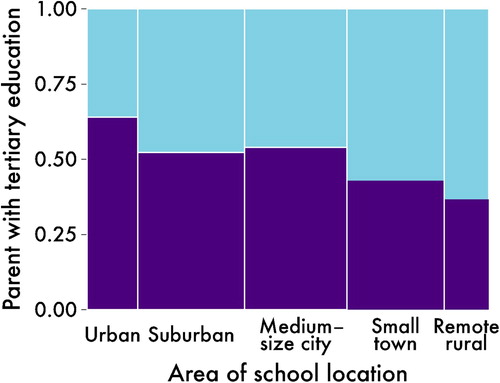

As can be seen from the above results, variation by location might have led to the finding that parental education and class were the most important factors in school choice. With regard to the results for parental education by location, we found that the gradient was about the same: 64% of parents in urban areas had a tertiary education but only 36% in remote rural areas (). As the first step of our analysis of locations was only bivariate, in the next section (on determinants of school choice) we present the results relating to the relationship between school choice, location and parental education. As for the class variables in the survey, the same pattern of advantaged urban areas and disadvantaged rural areas was found as described above, as unemployment and the working class were more prevalent in small towns and rural areas.

Fig. 3. The proportion of pupils with at least one parent with tertiary education (column widths proportional to number of responses)

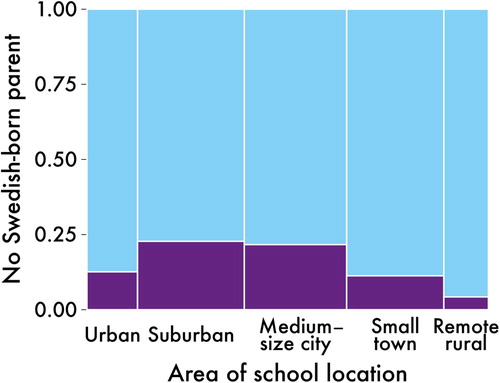

For the above-mentioned variables of risk of school choice, proportion of school choosers per school, parents with tertiary education, and parents’ social class, there was a linear gradient from urban to rural locations. However, for another group of variables, the medium-size cities and suburban locations (respectively 3 and 2 in ) were distinctive. Foreign-born parents were found in these two location types ().

Fig. 4. The proportion of pupils without a Swedish-born parent (column widths proportional to number of responses)

The urban–rural gradient was also found with regard to the variable expressing the parents’ expectation of children’s length of education. The expectations were the highest in urban locations and the lowest in remote rural locations. With regard to the aforementioned types of locations, the parents’ expectations were that, in due course, their child would be awarded a master’s degree or doctoral degree (not illustrated in the Figures).

From the school principals’ responses, we found that, compared with schools in other types of areas, schools in suburban locations seldom tended to report problems linked to insufficient supplies of instruction materials, supplies in general, instructional space, technological staff, audiovisual resources, computer technology, computer software, library resources, and science equipment and materials for experiments.Footnote4 Since only 140 schools were included in the Swedish TIMSS survey in 2015, the differences were not always significant. A possible explanation for the differences in supply is that many municipalities assign larger budgets to schools located in migrant-dense and poor neighbourhoods (often in suburban locations) and that these resources are used to ensure there is a sufficient supply of inputs to support instruction. By contrast, schools located in medium-size cities or large towns experienced the above-mentioned shortages, and overall seemed to be worse off than schools in the other locations.

The school principals were also asked to assess the teachers at their school. There was some tendency (not significant) for principals in urban and suburban schools to have a higher judgment of their teachers’ understanding of learning goals and success in implementing the curriculum, as well as higher expectations of the pupils.Footnote5 Moreover, there was a regional gradient with regard to how principals evaluated the role of parents. Many principals of schools in dense urban areas reported that parents had a high or very high level of commitment and expectations, that parental support for children to achieve good results was strong, and that parents demanded that the schools should maintain high academic standards.Footnote6 However, there was a tendency that principals of schools in suburban areas, medium-size cities, small towns, and remote areas less often reported high or very high scores on these items. However, since there were few observations, the results were not significant. The principals’ evaluations of the pupils were similar: for schools in dense urban areas, the principals reported a high or very high desire on the part of pupils to do well and their high ability to reach goals. This was to a lesser extent the case for schools in remote areas.

Another question in the survey answered by the school principals related to different kinds of discipline problems. In that regard there was an urban–rural gradient, but principals of remote rural schools most often reported a favourable environment, with few problems with late arrival, absenteeism, classroom disturbance, cheating, vandalism, theft, intimidation among pupils, and physical fights.

Lastly, when parents were asked about their children’s skills at the start of primary school, parents in more central locations reported their children had higher mathematical skills with respect to counting, recognizing numerals, and writing numerals compared with parents in more peripheral locations.

Determinants of school choice

From results, we know that geographical location is important for the performance of active school choice, the proportion of active school-choosers in schools, and parents’ education. In urban, densely populated areas, parents and pupils chose schools to a greater extent compared with parents in other locations. In this section we discuss parents’ characteristics and determinants of school choice.

Perhaps slightly surprising, with regard to area type, parental education was not an important characteristic of parents with regard to whether or not they made an active school choice (). This might have been because by 2015 the possibility for free school choice existed for all groups in society. Furthermore, few earlier studies have fully controlled for location type. Nevertheless, we found significance in suburban areas (), where parents without tertiary education had a somewhat higher propensity to make an active school choice.

Fig. 5. The area type and the proportion of parents with higher education who made an active school choice (column widths proportional to number of responses)

However, among parents who chose a school other than their nearest school (i.e. who made an active choice), it was evident from their responses to a question about their expectation that their ambitions for their children were higher, thus the schools mainly selected would have attracted parents with high ambitions and supposedly more involved in their children’s education. The parents answered the following question about their child: ‘How far in his/her education do you expect your child to go?’ We chose to analyse the highest level of education that they expected their child to finish, namely postgraduate education leading to either a master’s degree or doctoral degree. A total of 22% of parents believed their child would complete higher education. Throughout all the different areas, from urban to remote rural, more parents who made an active choice of school expected their child to finish postgraduate education than parents who did not make an active choice. For this reason, attitudes to education might be more positive in the case of schools attended by children whose parents include a high proportion of active choosers.

In contrast to the findings of Kessel & Olme (Citation2016), we found that foreign-born parents were more likely to choose a school than were Swedish parents, particularly in the case of schools located in suburban areas, medium-size cities or towns, and small towns and villages (). In those areas, 31% of Swedish-born parents made an active school choice for their children but for foreign-born parents the corresponding figure was 55%. However, it is possible that those who responded to the survey were school choosers and thus more involved in their children’s education compared with the foreign-born non-choosers. The latter parents might have been under-represented in the survey because all pupils with a migrant background were under-represented.

Parents’ social class (i.e. as defined according to the three-class version of ESeC) showed a small influence on school choice compared with location. The number of active choosers was determined by area type alone and we found there were many active choosers in urban areas and few in remote rural areas. The element of class that we introduced with reference to the three-class version of ESeC did not show significant results for almost all location types. The exception was that the unemployed and working class made an active choice to a larger extent than did the salariat and intermediate classes, contra the result reported by Reay & Ball (Citation1997). Normally, parents’ education and class are considered strong determinants of school choice. However, we suggest that our construction of the school choice variable changed our results in this regard. It might have been the case that families with higher class and well-educated parents were already favourably located closest to a ‘good’ school and thus chose that one. However, according to our definition of active choice regarding school, a different school from the closest one was chosen.

School choice and attitudes

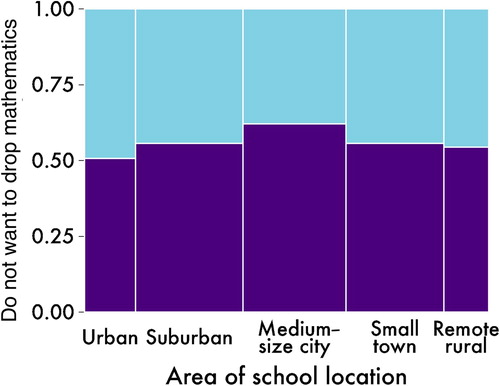

Although the ambitions of the parents as regards their children differed between those who chose a school and those who did not, similar differences in ambitions were not found among the children. In the survey, questions were asked regarding the pupils’ attitudes to the school subjects of mathematics and science. Pupils’ ambitions to learn more mathematics or science were not significantly different among those who were school choosers and those who were non-school choosers. This finding might reflect that the data were collected from children aged 10 or 11 years and thus relatively young. Although school choice did not make a difference to the ambitions expressed by the pupils there were some regional differences (). In medium-size cities pupils reported most frequently that they wished to learn more about mathematics.

Fig. 6. The proportion of pupils who did not want to drop mathematics (column widths proportional to number of responses)

There were some other geographical variations in the results based on the location of the schools. In densely populated urban areas and medium-size cities the interest in mathematics, expressed as ‘I learn many interesting things’, was somewhat higher among pupils who were school choosers compared with those who had not chosen a school. By contrast, in small towns the opposite was the case – a higher interest was found among pupils who had not chosen a school. Also, when examining the attitudes towards mathematics and science, we found that the two locations differed (). In particular, pupils who attended schools in the medium-size cities wished to learn more about mathematics and were enthusiastic about learning many new ‘things’ (saker) in mathematics. Positive attitudes towards learning were also found for the natural sciences, particularly among pupils who attended schools in the medium-size cities.

With regard to natural science as a taught subject, the degree of interest, expressed as ‘I learn many interesting things in science’, was slightly higher among pupils who were non-choosers in densely populated urban areas, and medium-size cities and for those who choose a school in small towns and villages. However, pupils in small towns and villages that had actively chosen their school were more likely to agree with the statement ‘I wish I did not have to study science.’

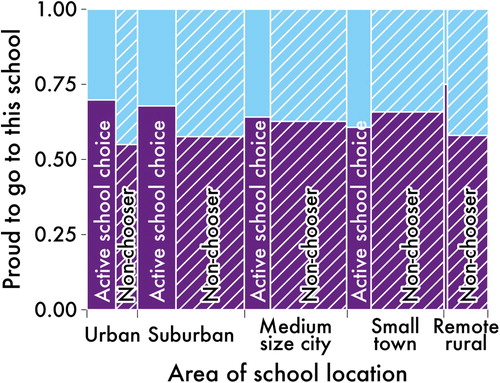

More pupils who chose their school in an urban or suburban area were proud of their school compared with pupils who had not chosen a school (). This was also the case for pupils who chose their school in rural areas, although the numbers were very small (not shown in Figures). In the rural group, the majority of the children were proud of their school. With respect to pupils’ pride in their school, no differences could be ascertained between those who were school choosers and not school choosers in medium-size cities or in the small towns and villages

Fig. 7. The area type and the proportion of pupils who agreed strongly with the statement ‘I am proud to go to this school’ (column widths proportional to number of responses)

School principals in active choosers’ schools more often reported that their pupils had a strong desire to do well than did principals of non-choosers’ schools. Furthermore, compared with school principals of ‘non-chooser’ schools, there was a weak tendency for school principals to give higher ratings for parental commitment, parental expectations, parental support for pupil achievement (i.e. for the pupil to achieve good results), and parental pressure. Late arrival was one type of problem more often reported by principals in schools with many active choosers. However, they less often reported problems with pupils using profane language.

Lastly, the school principals were asked to give their opinion on how many of their pupils had already acquired certain reading and counting skills at the start of primary school. There was a tendency for ‘active-choice schools’ to recruit pupils with more skills at the start of primary school, but the results were not clear-cut. Also, when parents were asked the same question, parents with children in schools with many active choosers gave significantly higher assessments of their children’s skills at school start compared with parents with children in schools with few active choosers.

School polarization and TIMMS2015 survey results relating to mathematics tests

To test the importance of the results relating to differences in attitudes between school locations in the TIMSS 2015 survey, we performed regression analyses on test results in mathematics as the dependent variable (the first to fifth plausible values in mathematics – the item IDs for the variables in the TIMMS 2015 International Database are IASMMAT01 to ASMMAT05 (TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center Citationn.d.)), and to perform an estimation with plausible values, we used Macdonald’s Stata module (Macdonald Citation2019) (for a description of how to perform regression analysis with plausible values, see OECD Citation2009).

shows the significant effects of location on mathematics results when only location variables were used but not when individual-level variables and school-class level co-variates are added (i.e. proportion of children with highly educated parents, proportion of children with foreign-born parents, and proportion of children in a class who were active school choosers). From the individual level variables in , it can be seen that parents with tertiary education had a strong positive effect and foreign-born parents a strong negative effect. also shows a parental ambition as having a positive effect, whereas making an active choice did not have a significant effect.

Table 3. The effects of parental status, location and class composition on maths results from the TIMMS 2015 survey (see footnote for source); fixed-effect models, with standard error shown in parenthesis (estimated using Macdonald’s Stata module (Macdonald Citation2019)); significant results (1%) shown in bold font

Furthermore, there is a positive association between mathematics results and having school peers with tertiary-educated parents, and a negative association between mathematics results and having school peers with foreign-born parents (on socio-economic influence, see Agirdag et al. Citation2012). In addition, being in a class with many active school choosers had a positive effect on the pupils’ mathematics results. Together, the explanatory variables explain a relatively modest amount of the variation in mathematics scores. However, it should be noted that we excluded attitude variables, which can be seen as representing pupils’ assessments of their ability in mathematics (Akyüz Citation2014).

Our results point to a polarization of Swedish schools based on school choice and location. The estimates shown in suggest that a lower proportion of parents with tertiary education in less central locations could make it harder for their children to excel in mathematics. Moreover, the results suggest that increased shares of children with higher parental expectations in schools with many pupils who make an active choice about the school they want to attend could help other pupils in such schools to achieve good results in mathematics.

Discussion

We found differences between types of areas in Sweden in the TIMSS survey material with respect to both attitudes towards education among parents and active choices regarding schools. We also found a spatial relation between attitudes towards education and school choice in that parents who expected long-term education for their children also made an active choice of school more frequently, which means that the children of parents with high expectations ended up together in the most popular schools.

These spatial differences are surprising for two reasons. First, when controlling for location, significance was lost in the commonly known parental education and class variables. Since, to our knowledge, this finding is the first based on school location data and school choice data from TIMSS (the Swedish TIMSS included a school choice questions not generally found in the TIMSS survey), we consider that the conflict with commonly known patterns of parental class and education can be explained by lack of previous research. Nevertheless, we found parental education and class influenced educational attitudes. However, in the Swedish TIMSS survey, it was found that parental education and class were less significant than school location, which was differentiated according to five area types.

Second, the spatial differences are problematic since ‘all children regardless of geographical location and background should have equal access to education’ (Regeringskansliet Citation2010, Chapter 1, Paragraph 8). The first chapter of Education Act of 2010 further states that ‘children and students shall be given the support and encouragement to develop as far as is possible’ (Paragraph 4) and that ‘the education shall be equal, irrespective of where in the country it is organized (Paragraph 9). Thus, spatial differences in education are not approved of and might result from differences in attitudes among parents. Moreover, according to the TIMMS 2015 survey, school principals reported that the children were exposed to different schools (source: see footnote 1).

In addition to differences in attitudes among parents, there is an apparent pattern of lower shares of people with tertiary education outside large cities and towns in Sweden (see ). The pattern both reinforces the spatial differences in educational attitudes and explains them. It reinforces the spatial differences in that there are few role models with high education in some area types, which means that neighbourhood effects do not lead to children being encouraged to take higher education. By constrast, the pattern explains the finding of lower education in peripheral areas in that children of parents with higher education who would normally follow their parents’ socio-economic careers instead follow the careers of comparatively lower educated parents.

Inequality in education can be approached in many ways in the social sciences. In this article we show spatial differences in attitudes that might affect outcomes. Evidently, the pupils whose parents had high expectations with regard to education of the children, also made school choices for their children. This was one outcome, but in this article we also present models () that estimate both the parental effects and school effects on mathematics test results based on the data from the TIMSS 2015 survey. According to Franck & Nicaise (Citation2017), parental attitudes towards education influence children’s attitudes and self-esteem to the extend that their performance is positively affected.

However, on the basis of research literature we can also theorize about how attitudes and spatial differences in education affect children. For example, never meeting highly educated persons, as more often happens in smaller cities, might limit the available role models and perceived opportunities to choose from for rural children. The result would then be reduced social mobility and some life-course trajectories would be hidden. Children in rural areas may become what their parents are with respect to both education and occupation, but with regard to higher education they may face difficulties in finding out about opportunities that they cannot see and experience in their surroundings (E.K. Andersson & Malmberg Citation2015). Thus, their future life courses will be regionally and spatially different; we found an urban–rural gradient in our study. However, in urban areas, if children only meet highly educated persons, there may not be any other types of careers visible to them. Entering the labour market and having a salary directly after secondary school may be out of the question for such children. However, usually cities and other urban areas have comparatively large numbers of different role models for children and therefore parents expectations with regard to their children will differ greatly. As indicated in the section ‘Determinants of school choice’, in Swedish cities, it is possible that parents’ high expectations put higher pressure on children and sometimes forcing children into certain educational choices.

Conclusions

In the literature, Sweden has been singled out as an example of neoliberalization that has gone very far in a former welfare state (e.g. K. Andersson & Kvist Citation2015; Sernhede et al. Citation2016). In this article we have used data from TIMSS 2015 – an international comparative assessment of pupil achievement in mathematics and science – to analyse the extent to which this neoliberalization has affected everyday life, particularly with respect to school choice. Our conclusion is that the impact of neoliberalism is geographically uneven. Whereas children and parents in metropolitan areas live in a strongly marketized school environment, this is much less the case in more peripheral areas. Marketization is seen as a sharp regional gradient with regard to the extent to which parents exercised school choice (see ). Our study also confirmed that there were large regional differences in education level of parents of pupils in Grade 4 and that there were clear regional differences in the socio-economic class status of the parents as well as in the parents'. expressed educational ambitions for their children. Somewhat surprisingly, given that social class has been stressed as an important factor for school choice, the differences in school choice were not a reflection of parents with tertiary education and/or the salariat group having a larger propensity to actively choose schools for their children; we did not find any difference in school choice between parents with or without tertiary education.

Over the years, the pressure to choose a school via municipal online systems has forced all parents to give more consideration to their choice, which earlier was only common among parents with education and with access to resources in the form of information. Furthermore, in relation to class, we found that parents in the salariat group were slightly less likely to make an active school choice for their children. Instead, a factor that strongly influenced school choice was whether parents were foreign-born, especially in suburban areas. Another factor that influenced school choice was parents’ educational ambitions for their children. Educational ambitions were higher in metropolitan areas, but parents with high educational ambitions for their children were more likely to make an active school choice, irrespective of where they lived.

However, even though there were large variations in parental background across regions, as well as in pupils with regard to school choice and non-school choice schools, the polarization was only weakly reflected in the attitudes expressed by the pupils in Grade 4. In densely populated urban areas and in suburban areas, pupils who had chosen a school expressed the view that they were proud of their schools more strongly compared with pupils who had not made a choice, but this tendency was not found in other areas. Otherwise, there were few differences between school choice and non-school choice schools with regard to pupils’ attitudes.

A possible interpretation of our findings is that educational marketization in Sweden should not necessarily be interpreted as an expression of structural trends towards neoliberalism. Instead, they can be seen as related to high levels of marketization that traditionally have been associated with dense urban areas (Wirth Citation1938). As working-class members of metropolitan populations have declined and professional career-oriented groups have increased, this trend might have been further strengthened (cf. Hamnett Citation2003). Thus, the findings presented in this article suggest that if interpretations of societal trends are based on patterns found in the metropolitan areas in Sweden, there is a risk that that the strength of neoliberalization in Sweden will be overemphasized, as there are large areas in Sweden where changes in the school environment have been much less pronounced than in, for example, Stockholm.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the Swedish Research Council (VR), grant registration number 2014-1977, and the Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences (RJ), grant registration number M18-0214:1. In addition, we are grateful to Pontus Hennerdal for help with the data and to Helen Eriksson, SUDA, Stockholm University for the Stata estimation.

Notes

1 Data files with test results and survey results for the Swedish population in TIMSS 2015, Grade 4 and Grade 8 (Datafiler med provresultat och enkätsvar för den svenska populationen i Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) 2015 årskurs 4, och årskurs 8), (Dnr 75-2013:69). The dataset can be accessed upon application to Skolverket.

2 In the year that children become 6 years of age, they attend preschool class (förskoleklass) to prepare them for starting school.

3 All translations from Swedish into English have been made by the authors of this article.

4 The item IDs for the variables in the TIMMS 2015 International Database are ACBG14AA, ACBG14AB, ACBG14AE to ACBG14AH, ACBG14BA to ACBG14BC, ACBG14BE, ACBG14CA, to ACBG14CD (TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center Citationn.d.).

5 The item IDs for the variables in the TIMMS 2015 International Database are ACBG15A to ACBG15E (TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center Citationn.d.).

6 The item IDs for the variables in the TIMMS 2015 International Database are ACBG15F to ACBG15M (TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center Citationn.d.).

References

- Agirdag, O., Van Houtte, M. & Van Avermaet, P. 2012. Why does the ethnic and socio-economic composition of schools influence math achievement? The role of sense of futility and futility culture. European Sociological Review 28(3), 366–378. doi:10.1093/esr/jcq070

- Akyüz, G. 2014. The effects of student and school factors on mathematics achievement in TIMSS 2011. Education and Science 39(172), 150–162.

- Andersson, E.K. & Malmberg, B. 2015. Contextual effects on educational attainment in individualised, scalable neighbourhoods: Differences across gender and social class. Urban Studies 52(12), 2117–2133.

- Andersson, E., Malmberg, B. & Osth, J. 2012. Travel-to-school distances in Sweden 2000–2006: Changing school geography with equality implications. Journal of Transport Geography 23, 35–43. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.03.022

- Andersson, E.K., Hennerdal, P. & Malmberg, B. 2019. The re-emergence of educational inequality during a period of reforms: A study of Swedish school keavers 1991–2012. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science. doi:10.1177/2399808319886594

- Andersson, K. & Kvist, E. 2015. The neoliberal turn and the marketization of care: The transformation of eldercare in Sweden. European Journal of Women’s Studies 22(3), 274–287.

- Baeten, G., Berg, L.D. & Lund Hansen, A. 2015. Introduction: Neoliberalism and post-welfare nordic states in transition. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 97(3), 209–212.

- Bagley, C. 2015. School choice in an English village: Living, loyalty and leaving. Ethography and Education 10(3), 278–292.

- Barrett De Wiele, D.C. & Edgerton, J.D. 2016. Parentocracy revisited: Still a relevant concept for understanding middle class educational advantage? Interchange: A Quarterly Review of Education 47(2), 189–210.

- Barthon, C. & Monfroy, B. 2010. Sociospatial schooling practices: A spatial capital approach. Educational Research and Evaluation 16(2), 177–196.

- Bell, C. 2007. Space and place: Urban parents’ geographical preferences for schools. Urban Review: Issues and Ideas in Public Education 39(4), 375–404.

- Bell, C. 2009. Geography in parental choice. American Journal of Education 115(4), 493–521.

- Benson, M., Bridge, G. & Wilson, D. 2015. School choice in London and Paris – A comparison of middle-class strategies. Social Policy & Administration 49(1), 24–43.

- Björklund, A., Edin, P.-A., Fredriksson, P. & Krueger, A. 2004. Education, Equality and Efficiency – An Analysis of Swedish School Reforms During the 1990s. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Peter-Fredriksson-2/publication/267260610_Education_equality_and_efficiency_-_An_analysis_of_Swedish_school_reforms_during_the_1990s/links/54748aa50cf245eb436de4ea/Education-equality-and-efficiency-An-analysis-of-Swedish-school-reforms-during-the-1990s.pdf (accesssed 7 March 2021).

- Boone, S. & Van Houtte, M. 2013. In search of the mechanisms conducive to class differentials in educational choice: A mixed method research. Sociological Review 61(3), 549–572.

- Bosetti, L. 2004. Determinants of school choice: Understanding how parents choose elementary schools in Alberta. Journal of Education Policy 19(4), 387–405.

- Brown, P. 1990. The ‘third wave’: Education and the ideology of parentocracy. British Journal of Sociology of Education 11(1), 65–86.

- Bulman, R. C. 2004. School-choice stories: The role of culture. Sociological Inquiry 74(4), 492–519.

- Bunar, N. 2010. Choosing for quality or inequality: Current perspectives on the implementation of school choice policy in Sweden. Journal of Education Policy 25(1), 1–18.

- Burgess, S. & Briggs, A. 2010. School assignment, school choice and social mobility. Economics of Education Review 29(4), 639–649.

- Burgess, S., Greaves, E., Vignoles, A. & Wilson, D. 2011. Parental choice of primary school in England: What types of school do different types of family really have available to them? Policy Studies 32(5), 531–547.

- Butler, T. & Hamnett, C. 2007. The geography of education: Introduction. Urban Studies 44(4), 1161–1174.

- Butler, T., Hamnett, C., Ramsden, M. & Webber, R. 2007. The best, the worst and the average: Secondary school choice and education performance in East London. Journal of Education Policy 22(1), 7–29.

- Butler, T., Hamnett, C. & Ramsden, M.J. 2013. Gentrification, education and exclusionary displacement in East London. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37(2), 556–575.

- Denessen, E., Driessen, G. & Sleegers, P. 2005. Segregation by choice? A study of group-specific reasons for school choice. Journal of Education Policy 20(3), 347–368.

- Dovemark, M., Kosunen, S., Kauko, J., Magnúsdóttir, B., Hansen, P. & Rasmussen, P. 2018. Deregulation, privatisation and marketisation of Nordic comprehensive education: Social changes reflected in schooling. Education Inquiry 9(1), 122–141.

- Elacqua, G., Schneider, M. & Buckley, J. 2006. School choice in Chile: Is it class or the classroom? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 25(3), 577–601.

- Franck, E. & Nicaise, I. 2017. The Effectiveness of Equity Funding in Education in Western Countries. https://nesetweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/NESET-II_AHQ2.pdf (accessed 7 March 2021).

- Gustafson, K. 2006. Vi och dom i skola och stadsdel. Doctoral thesis. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- Hamnett, C. 2003. Gentrification and the middle-class remaking of inner London, 1961–2001. Urban Studies 40(12), 2401–2426. doi:10.1080/0042098032000136138

- Hamnett, C. & Butler, T. 2013. Distance, education and inequality. Comparative Education 49(3), 317–330.

- Harrison, E. & Rose, D. 2006. The European Socio-economic Classification (ESeC) User Guide. Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex. https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/archives/esec/user-guide (accessed 9 March 2021).

- Harvey, D. 2007. Neoliberalism as creative destruction. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 610(1), 21–44.

- Hennerdal, P., Malmberg, B. & Andersson, E.K. 2018. Competition and school performance: Swedish school leavers from 1991–2012. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 64(1), 70–86. doi:10.1080/00313831.2018.1490814

- Kessel, D. & Olme, E. 2016. Rapport 1: Obligatoriskt skolval. Föräldrars motiv vid val av skola, och vad det innebär vid obligatoriskt skolval. https://www.lr.se/download/18.2c5a365d1645ac11059e0e2/1559028168089/obligatoriskt_skolval_LR_Lf_LO_201610.pdf (accesssed 22 February 2021).

- LaRoche, S., Joncas, M. & Foy, P. 2016. Sample design in TIMSS 2015. Martin, M.O., I.V.S. & Hooper, M. (eds.) Methods and Procedures in TIMSS 2015, 3.1–3.37. http://timss.bc.edu/publications/timss/2015-methods/chapter-3.htm (accessed 7 March 2021).

- Macdonald, K. 2019. PV: Stata module to perform estimation with plausible values. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s456951.html (accessed 24 March 2021).

- Malmberg, B., Andersson, E.K. & Bergsten, Z. 2014. Composite geographical context and school choice attitudes in Sweden: A study based on individually defined, scalable neighborhoods. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104(4), 869–888. doi:10.1080/00045608.2014.912546

- Malmberg, B., Andersson, E.K., Nielsen, M.M. & Haandrikman, K. 2018. Residential segregation of European and non-European migrants in Sweden: 1990–2012. European Journal of Population 34(2), 169–193.

- Martin, M.O., Mullis, I.V.S. & Hooper, M. (eds.) 2016. Methods and Procedures in Timss 2015. https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/publications/timss/2015-methods.html (accessed 24 March 2021).

- Musset, P. 2012. School Choice and Equity: Current Policies in OECD Countries and a Literature Review. OECD Working Papers No. 66. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED529507 (accessed 7 March 2021).

- Nielsen, M.M. & Hennerdal, P. 2019. Segregation of residents with tertiary education in Sweden from 1990 to 2012. The Professional Geographer 71(2), 301–314. doi:10.1080/00330124.2018.1518719

- Oberti, M. 2007. Social and school differentiation in urban space: Inequalities and local configurations. Environment and Planning A, 39(1), 208–227. doi:10.1068/a39159

- OECD. 2009. Analysis with plausible values. PISA Data Analysis Manual: SPSS, Second Edition, 117–130. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/pisa-data-analysis-manual-spss-second-edition_9789264056275-en (accesssed 24 March 2021).

- Oría, A., Cardinib, A., Balla, S., Stamoua, E., Kolokithaa, M., Vertigana, S. & Flores-Morenoa, C. 2007. Urban education, the middle classes and their dilemmas of school choice. Journal of Education Policy 22(1), 91–105.

- Pareliussen, J.K., Hermansen, M., André, C. & Causa, O. 2018. Income inequality in the Nordics from an OECD perspective. Aaberge, R., André, C., Boschini, A., Calmfors, L., Gunnarsson, K., Hermansen, M., Langørgen, A., Lindgren, P., Orsetta, C., Pareliussen, J., Robling, P.-O., Roine, J., & Egholt Søgaard, J. (eds.) Increasing Income Inequality in the Nordics, 17–57. Nordic Economic Policy Review 2018. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Rangvid, B.S. 2010. School choice, universal vouchers and native flight from local schools. European Sociological Review 26(3), 319–335.

- Reay, D. & Ball, S.J. 1997. ‘Spoilt for choice’: The working classes and educational markets. Oxford Review of Education 23(1), 89–101. doi:10.1080/0305498970230108

- Regeringskansliet. 2010. Skollag (2010:800). SFS nr: 2010:800. Utbildningsdepartementet, Stockholm. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800 (accessed 24 March 2021).

- Rönnberg, L. 2011. Exploring the intersection of marketisation and central state control through Swedish national school inspection. Education Inquiry 2(4), 689–707.

- Sernhede, O., Thörn, C. & Thörn, H. 2016. The Stockholm uprising in context: Urban social movements in the rise and demise of the Swedish welfare-state city. Mayer, M., Thörn, C. & Thörn, H. (eds.) Urban Uprisings: Challenging Neoliberal Urbanism in Europe, 149–173. London: Palgrave Macmillian.

- Skawonius, C. 2005. Välja eller hamna: Det praktiska sinnet, familjers val och elevers spridning på grundskolor. Doctoral thesis. Stockholm: Stockholm University, Pedagogiska institutionen.

- Skolverket. 2012. Likvärdig utbildning i svensk grundskola? En kvantitativ analys av likvärdighet över tid. Rapport 374. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Skolverket. 2018. Analyser av familjebakgrundens betydelse för skolresultaten och skillnader mellan skolor: En kvantitativ studie av utvecklingen över tid i slutet av grundskolan. Rapport 467. https://www.skolverket.se/getFile?file=3927 (accessed 7 March 2021).

- Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner. 2019. Kommungruppsindelning 2017. https://skr.se/tjanster/kommunerochregioner/faktakommunerochregioner/kommungruppsindelning.2051.html (accessed 9 March 2021).

- Sveriges Officiella Statistik. 2020. Skolenheter och elever läsåren 2011/12-2016/17 [Excel file]. https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/sok-statistik-om-forskola-skola-och-vuxenutbildning?sok=SokC&omrade=Skolor%20och%20elever&lasar=2016%2F17&run=1 (accessed 24 March 2021).

- Tammaru, T., van Ham, M., Marcińczak, S. & Musterd, S. 2015. Socio-economic Segregation in European Capital Cities: East Meets West. London: Routledge.

- Theodore, N., Peck, J. & Brenner, N. 2011. Neoliberal urbanism: Cities and the rule of markets. Bridge, G. & Watson, S. (eds.) The New Blackwell Companion to the City, 15–25. Chichester: Blackwell.

- TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. n.d. TIMSS 2015 International Database. https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2015/international-database/ (accesssed 9 March 2021).

- Van Zanten, A. 2005. New modes of reproducing social inequality in education: The changing role of parents, teachers, schools and educational policies. European Educational Research Journal 4(3), 155–169.

- Walker, M. & Clark, G. 2010. Parental choice and the rural primary school: Lifestyle, locality and loyalty. Journal of Rural Studies 26(3), 241–249.

- Waslander, S., Pater, C. & van der Weide, M. 2010. Markets in Education: An Analytical Review of Empirical Research on Market Mechanisms in Education. OECD Education Working Papers No. 52. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Wiborg, S. 2013. Neo-liberalism and universal state education: The cases of Denmark, Norway and Sweden 1980–2011. Comparative Education 49(4), 407–423.

- Wirth, L. 1938. Urbanism as a way of life. American Journal of Sociology 44(1), 1–24.