ABSTRACT

Several Norwegian mountain and coastal municipalities have experienced comprehensive second-home development in recent decades. From a sustainability perspective, it is necessary to understand both the importance of various geographical locations within a local context, as the location has an impact on available resources, amenities, and courses of action, and the complex interdependencies between the three sustainability pillars: economy, society, and environment. The purpose of the article is to provide knowledge on why and how various locations matter for planning sustainable second-home tourism. The analysis is based on document studies and interviews from three Norwegian destinations, supplemented with official statistics. The findings indicate that emphasis on, and development challenges associated with, the sustainability pillars differ across locations. They also indicate that local capacities to assess, plan, and implement adequate measures to address specific sustainable development challenges vary. Hence, there is a need for regional and local authorities to reflect on the driving forces behind the development of second-home tourism, as the impacts vary depending on what and who is driving the development. The authors conclude that it matters where second-home development is planned and what sustainability measures are adequate, applicable, and available. Nevertheless, all three pillars must be considered even if just one is enhanced.

Introduction

Several Norwegian mountain and coastal municipalities have experienced comprehensive second-home development in recent decades, a type of development that has deviated from former trends in two ways. First, the scope of such development has increased in terms of numbers and density (Arnesen et al. Citation2012; Arnesen & Ericsson Citation2013; Ellingsen & Arnesen Citation2018). Second, the technical standards of the second homes have improved significantly and now often equal the owners’ primary residence (Overvåg Citation2009a; Arnesen et al. Citation2012; Arnesen & Ericsson Citation2013).

In partial contrast to recent trends in some other European countries, no significant permanent urban-to-rural migration has occurred in Norway or the other Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland). Instead, the quality-of-life motives that contribute to such migration are satisfied by frequent visits to rural second homes (Müller Citation2011; Ericsson et al. Citation2012; Hiltunen et al. Citation2013; Adamiak et al. Citation2017). As a result, second-home tourism with new spatial-temporal household arrangements is a prominent feature of domestic tourism in the Nordic countries (Müller Citation2021).

The forces driving the second-home development are diverse and complex and may include local landowners, investors, real estate developers, or public authorities and/or politicians. Many rural communities struggle with job loss and depopulation, partly caused by local economic shifts from agricultural and forestry-based production to service industries. Second-home development is often seen as a lifeline within rural communities striving for economic progress through various counter-urbanization processes. Such communities respond to increasing demands for second homes due to people’s mobility lifestyles and higher incomes, as well as their desire for nature experiences, outdoor recreation in convenient settings, and improved infrastructure (Eimermann et al. Citation2017). Locally, the expected effects may consist of land sales representing substantial income for landowners, and second homes as significant contributors to local economies through residential taxes, local retail trade, and increased market potential for the construction and service industries (e.g. Flognfeldt Citation2004; Overvåg Citation2009b).

Several authors have noted the value of including second-home planning in regional and local development plans (Müller et al. Citation2004; Brida et al. Citation2011; Åkerlund et al. Citation2015). However, research on Norwegian conditions reveals that second-home issues are rarely included in any planning instruments, except land-use plans (Overvåg Citation2011; Skjeggedal & Overvåg Citation2014).

The geography of second-home tourism differs in terms of community relations and resource management and use patterns, and many of these geographies have not been addressed properly (e.g. Back & Marjavaara Citation2017; Müller Citation2021). Based on a review of Nordic second-home tourism research, Müller (Citation2021) has calls for assessment of development of second homes in different geographical contexts. In an analysis of second homes in different settings, Back found that a rural–urban dichotomy alone did not explain differences in land-use planning, public services, local economy, and social or political impacts, but also that ‘there were marked differences between the second-home landscapes in how the municipalities managed these situations […] and second-home tourism’s impacts on municipalities, planning authorities and local economics’ (Back Citation2020, 1339).

As different places struggle with different challenges regarding development issues, such as market access, growth potential, environmental impacts, and conflicting interests, we argue that local factors such as demographics, labour markets, resources, amenities, development strategies, and location must be assessed to understand also which sustainability dimensions are likely to require the most attention in each case and why.

Sustainability is commonly seen as resting on three pillars of economic development, social issues, and ecological awareness, and therefore sustainability means balancing these concerns (Hall et al. Citation2015). Tourism is considered sustainable to the extent that tourism-specific planning and management systems fully account for current and future economic, social, and environmental impacts. Also, the interests of visitors, industry, environment, and host communities should be balanced (Gössling et al. Citation2009; Williams & Ponsford Citation2009). However, short-term economic benefits often overshadow holistic, long-term approaches (Hall Citation2015). Furthermore, long-term approaches necessitate assessments of social, cultural, and environmental effects, as well as instruments for balancing economic and user-intensity effects on the quality of life and well-being of locals, second-home owners, and tourists (Hall et al. Citation2015; Andersen et al. Citation2018). Whereas sustainability measures previously tended to be perceived as a threat to profitability and competitiveness of tourism businesses, they are now increasingly seen as a market asset (Pulido-Fernandez et al. Citation2015; Cucculelli & Goffi Citation2016). Hence, sustainability measures are often recognized as prerequisites for maintaining the resources upon which tourism businesses depend for product development (Fredman & Tyrväinen Citation2010). However, conflicting interests may be a barrier to further development at a destination. According to Sørensen & Grindsted (Citation2021), one reason for conflicting interests is different sustainability approaches. This leads to our first research question: How does local context (location) influence local actors’ perceptions of sustainability challenges regarding second homes?

A particular concern with respect to the first research question is how crucial sustainability goals are perceived and considered at local levels (i.e. down to the individual business level) and regional levels, as well as the extent to which stakeholders at these levels have access to means and instruments that enable them to contribute to more sustainable second-home tourism development. This leads to our second research question: How does the local context (location) influence what are the adequate, applicable, and available means and instruments for dealing with the sustainability challenges regarding second homes?

In this article, the above-mentioned issues are discussed in view of the extensive second-home development in Scandinavia in general, and in Norway specifically. We also take into consideration that current research pays attention to how this kind of development is a response to increasing market demands, as well as the needs of local communities for new industry paths and employment, and thus, sustainable settlements (e.g. Ericsson [Citation2006]; Overvåg Citation2010; Velvin et al. Citation2013). We explore sustainability issues based on local-level findings from three Norwegian inland destinations included in the research project on sustainable tourism experiences, ‘Bærekraftige opplevelser i reiselivet’, run by the Centre for Tourism Research (Senter for reiselivsforskning) at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences in the period 2017–2020.

Literature review

Second homes and sustainability

Rural second-home tourism used to be regarded as relatively environmentally friendly compared with most other types of tourism (Müller et al. Citation2004). However, the environmental impacts of second-home development have increasingly been brought into focus and debated (Long & Hoogendoorn Citation2013; Hall Citation2014). Environmental concerns relate to large temporary populations and potential effects on amenity values, as well as wildlife, vegetation, and habitat (Hiltunen Citation2007; Støen et al. Citation2010). Furthermore, there is an increasing focus on the impacts of second homes on climate change, and it is argued that increased frequency of visits is generating growth in energy use and infrastructure (Næss et al. Citation2019).

Until recently, second homes had traditionally been dispersed across amenity-rich rural landscapes and natural environments. Today, new second homes are increasingly clustered in existing or new resorts (Paris Citation2014). Accordingly, the average land use per entity has been reduced to some extent, as new second homes are built in agglomerations rather than dispersed. However, the extensive infrastructure required to establish and operate second-home resorts often decreases the aesthetic and biodiversity value of rural landscapes (Gallent et al. Citation2005; Hiltunen Citation2007).

The positive economic effects of second homes due to property taxes, land sales, and new market opportunities for local construction and retail have been highlighted (Hoogendoorn & Visser Citation2011; Robertsson & Marjavaara Citation2015). However, despite the potential for capital transfer from urban centres to rural communities, Czarnecki (Citation2018) and Sheard (Citation2019) argue that economic benefits are far from unambiguous, as second-home dwellers tend to be motivated by free or inexpensive outdoor activities and they mainly prefer self-catering. A related issue is how potential economic benefits are distributed within a community, which raises concerns about the long-term social sustainability in such communities.

The social dimensions of second homes are also related to the effects of seasonal influxes of temporary second-home populations. There has been a tendency for more scholars to look beyond the notions of home, place of residence, migration, and population, and to include diverse mobilities, which often are related to multiple residences and tourism (Overvåg Citation2011; Halfacree Citation2012; Hall Citation2015). Owing to improved communicating infrastructure and high standards of second homes, the number of visits has increased considerably, and hence mobility between two homes has become a way of life (Overvåg Citation2011; Ellingsen Citation2017). Accordingly, distinctions between primary and second home, and between permanent and temporary have become blurred (Farstad & Rye Citation2013; Åkerlund et al. Citation2015). As part-time inhabitants, the economic and social capital of second-home owners may contribute to revitalizing of rural life and local development (Flognfeldt Citation2004). Recurrent visits and repeated experiences of the same place may foster a strong sense of place, as people can have multiple place attachments (Kaltenborn et al. Citation2007; Overvåg Citation2011; Ellingsen Citation2017). However, second-home owners might also represent views on land use, development, and environment that deviate from those of permanent residents (Hall Citation2014; Farstad Citation2016), which underpins findings that stakeholders and actors at a destination have different sustainability approaches (Sørensen & Grindsted Citation2021).

Hall et al. (Citation2015) argue that clearly defined national policies and procedures to facilitate sustainable second-home development are insufficient. In addition, local planning tends to focus on economic development without sufficient consideration of the social and environmental impacts of second homes (Hidle et al. Citation2010; Müller & Hall Citation2018). Whereas rural communities seek to attract second-home owners, such communities are often poorly equipped to govern implications beyond land-use planning for such mobility (Hall Citation2015). Nevertheless, although second-home development has become subject to policymaking, legislation, and regulation (Müller et al. Citation2004; Hall Citation2015; Ellingsen & Arnesen Citation2018), measures have been limited to mainly land-use planning. Municipal provision of public services (e.g. sewerage, infrastructure, and social services) is primarily or usually based on the number of permanent residents (Paris Citation2014). Hence, second-home dwellers become a population that is ‘invisible’ to local authorities; consequently, infrastructure and public services are not dimensioned according to the actual number of people who use them (Paris Citation2014; Adamiak et al. Citation2017; Back & Marjavaara Citation2017; Müller & Hall Citation2018). Thus, inadequate policies and deficient plans may impact negatively on the potential for second-home development benefits.

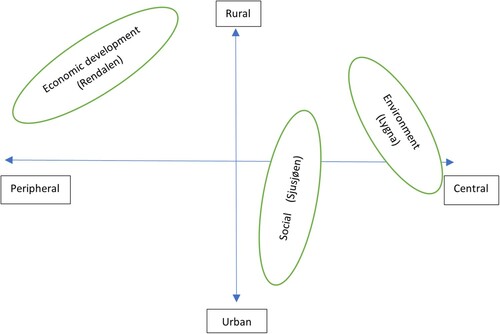

The concept of sustainability has extended from its original focus mainly on ecological and environmental issues to include social and economic sustainability (Bramwell et al. Citation2017; Butler Citation2019). As Fennell & Cooper (Citation2020, 3) state, sustainable development ‘is based on the idea that economic growth should occur in a more ecologically responsible and socially equitable manner’. A simple model commonly used to explain sustainability is the triangle of environmental (conservation), economic (growth) and social (equity) dimensions (Keiner Citation2005). This model is used as a starting point for our analysis and discussion, although it is modified (based on Medalen Citation2008) to suit the Norwegian context ().

Fig. 1. Three dimensions of sustainability and their respective main conflict themes and policy areas (based on Medalen Citation2008)

While a growing amount of literature on second-home development has identified multiple sustainability challenges, there seems to be a lack of suggestions for feasible solutions (Hiltunen et al. Citation2013; McCool et al. Citation2013). In part, this might be because of insufficient focus on local contexts (Back Citation2021). Even though purpose-built second homes in amenity-rich areas can be characterized by some common features, the local context needs to be taken into consideration (Back Citation2020).

The dichotomies of centre–periphery and urban–rural have been a key issue in Norwegian politics, with strong resistance from politicians towards centralization, and a policy of preserving settlements throughout the country. Nonetheless, migration to central and urban areas has been consistent and has increased, as free market forces have gained more leeway when primary industries (fishing, agriculture, and forestry) employ fewer people than before (Hidle et al. Citation2006). Despite a rather unambiguous development, the effect on rural and/or peripheral communities is far from uniform, implying that the above-mentioned two dichotomies are insufficient to describe and analyse the variation in how communities encounter challenges. As pointed out by Frisvoll (Citation2018), there are rural communities in central areas in geographical proximity to metropolitan areas, as well as towns and urban communities in the peripheries (e.g. in the northernmost counties, far from main metropolitan areas). Economic prosperity and political and administrative capacity to act strategically vary depending on factors such as types of economic basis, population size, and proximity to metropolitan areas (Frisvoll Citation2018). In addition, rural communities are still characterized by different ways of living and cultural affiliation (Rahbek Christensen Citation1997). Cultural expressions and values tend to divert from the dominant urban culture, often in terms of both identities and lifestyles (Øian Citation2013; Skogen et al. Citation2017). Accordingly, the sustainability challenges of rural communities need to be addressed differently. In the remaining part of this article, we discuss how measures to improve sustainability in second-home development must be considered in light of how features of local contexts influence the manifestation of sustainability issues and the ability to implement adequate instruments to improve these issues.

Norwegian contexts and the cases

Research on second-home tourism in Norway has a vague history back to 1948 (Sund Citation1948) which, over time, has been concerned with various aspects of what is now conceptualized as sustainability. Until the 1965 implementation of the Planning and Building Act, the location and construction of second homes were to a large extent private matters between landowner and builder. The first major study of second homes in Norway was conducted by Fjellplanteamet (English translation: The Mountain Planning Team) in the 1960s. The team’s primary research focus was landscape and environmental sustainability (Sømme & Langdalen Citation1965). In the late 1960s, second homes were regarded as primarily a landscape matter.

In the models for second-home locations compiled by Fjellplanteamet, it was suggested that alpine and coastal areas should be exempt from further second-home development (Sømme & Langdalen Citation1965; Ericsson et al. Citation2011). During the late 1960s, access to a second home was considered a major welfare benefit. Hence, as long as the location and landscape (mainly visual) impacts were acceptable, second-home development was encouraged by central government.

During the 1970s and 1980s, drawbacks and negative consequences became notable, including increased traffic and pollution, landscape interference, and disruption of agricultural operations. Accordingly, the welfare benefits were given a less prominent position, as the Ministry of the Environment (Miljøverndepartementet) advised local public administrations to ‘tighten up’ and implement building bans in specific areas (Ericsson et al. Citation2011). Norway’s hosting of the 1994 Winter Olympics triggered a building boom in well-equipped second homes located in agglomerations and mountain villages, which became the dominant form of second-home development. The boom is also considered the starting point of a development motivated by real estate profitability potential initiated by professional property investors and/or powerful landowners, who leaned heavily on many rural municipalities’ administrators and politicians to allow building permits (Ericsson et al. Citation2011). The development marked the beginning of a period of pronounced importance of money, influence, power, and other resources to second-home development (Müller Citation2007).

The development of well-equipped second homes led to more intensive use, causing ripple effects to local businesses by creating employment and trade turnover, which further encouraged municipalities to ‘speed up’ second-home development. This became especially pronounced in municipalities with sparse population and potential for second-home development. The development was supported yet further when municipalities’ property taxation was extended in 2007 to encompass second homes. Whereas factors such as climate change awareness and negative environmental impacts made central government reluctant to sustain second-home development, many municipalities continued to increase the pace of development (St.meld. nr. 21 (Citation2004–2005); Ericsson et al. Citation2011).

Second homes in the mountain areas of Norway are almost exclusively in purpose-built clusters in areas that are geographically separated from residential areas and rarely affect local communities directly, unlike in other countries where second homes are more integrated into residential areas (Overvåg & Berg Citation2011; Hoogendoorn & Marjavaara Citation2018; Back Citation2021). In the Nordic countries in general, it is nature and landscape environments rather than the idyll of rural villages that attract second-home owners. In other words, the development is not characterized by amenity migration but rather by frequent visits. Norwegian second homes in mountain areas rarely influence housing markets, while this may be the case in coastal towns and villages.

Nevertheless, although the historical policies described above illuminate discrepancies between national wishes and local actions, second-home development measures must be considered based on each municipality’s unique situation (Back Citation2021). As planning and development of second homes are regulated by the Planning and Building Act, which is enforced by the municipalities, this is almost entirely a municipal matter because state interventions are mainly limited to objections regarding land use and biodiversity.

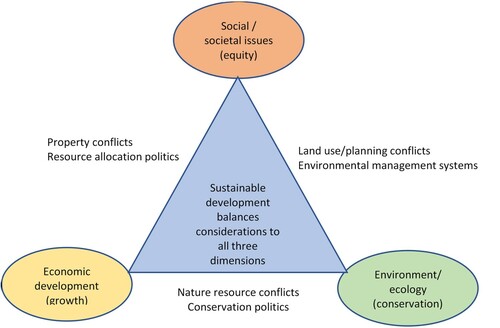

This brief review demonstrates that while aspects of sustainability clearly were assessed by stakeholders and actors in Norway in the period between the mid-1960s and c.2010, they were not necessarily notified as sustainability motives. To elaborate further on sustainability considerations connected to second-home development today, the research project ‘Bærekraftige opplevelser i reiselivet’ (2017–2020), run by the Centre for Tourism Research at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, included a study of where, when, and how second-home development contributes to, or counteracts, current sustainability goals. This was done by selecting three destinations to reveal sustainability challenges in various local contexts. The destination cases selected for further investigation were Sjusjøen in Ringsaker Municipality, Renåfjellet in Rendalen Municipality, and Lygna in Gran Municipality ().

Fig. 2. Three Norwegian case study areas: Sjusjøen, Renåfjellet and Lygna (© Esri ArcGIS Pro 2.7, reproduced with permission)

Case descriptions

Destination Sjusjøen – a recreational village

Sjusjøen, in Ringsaker Municipality, is one of Norway’s largest, most densely developed second-home agglomerations, with c.7000 second homes (Statistisk sentralbyrå Citationn.d.,a). Property rights are executed by two commons and a limited company. During the first decades after World War II, numerous cabins without electricity, water, or vehicle access during winter were dispersed throughout the amenity-rich mountain landscape, close to the barren mountain heaths. Recent developments include second homes built to high standards, which are relatively expensive, accessible by vehicle, and located in clusters in forest areas farther from the barren, vulnerable landscape areas, combined with densification in older developments.

Sjusjøen is in a remote part of Ringsaker Municipality, which also encompasses two minor towns, good job opportunities, and a growing population. Sjusjøen is geographically separate from the main residential areas. Most of the second-home owners are registered as resident in metropolitan areas, within a driving time of 2–3 hours by car. In parallel to the second-home development, traditional accommodations were demolished or converted into apartments for rent or ownership. Of several original hotels and lodges, only one mountain lodge is still operating. Today, the area hosts extensive infrastructure and service facilities: a sports shop, a grocery store, restaurants and cafes, a fitness centre, and a sports hall. The area’s main attraction is its mountain landscape, with an extensive network of well-maintained ski tracks (i.e. prepared tracks), as well as hiking trails, some of which have been adapted and designated for cycling. Accelerated development in recent years has created controversies between second-home owners and landowners regarding landowners’ responsibility to develop common areas and ensure future sustainability. Local and regional outdoor recreationists and second-home owners who prefer the preservation of what they perceive as an authentic landscape resent the transformation entailed by the extensive development of second homes and the accompanying infrastructure.

Destination Renåfjellet – an area in a municipality in decline

Renåfjellet is a destination located in a remote (peripheral), rural, and sparsely populated municipality, Rendalen Municipality, which encompasses vast, uninhabited forests and mountain ranges. The municipality’s population is declining, and job opportunities are scarce and dominated by public administration. Thus, Rendalen is far from in the same position as Ringsaker with regard to location, population development, negotiable resources, and potential for economic growth. Currently, the municipality’s 2300 second homes exceed its number of residents (1800) (Statistisk sentralbyrå Citationn.d.,a), and there are an additional 1500 construction-ready scattered plots (Statistisk sentralbyrå Citationn.d.,b). Many second homes can be characterized as traditional cabins, which are scattered and lack electricity, water, and sewage facilities. The second homes (c.350) built on the slopes of Renåfjellet are close to a regional traffic hub and a minor shopping area. These second homes represent a new generation in terms of location and standards in Rendalen. They are connected to the power grid, centralized water and sewage infrastructure, and are with easy access to a minor alpine skiing facility. Despite comprehensive investments and facilitation in the area, and despite planning approval for many plots and general goodwill to promote development, further construction of new second homes has stalled since c.2010. Neither the investor nor the developer are local to Renåfjellet.

Despite the alpine skiing facility adjacent to the Renåfjellet development, the main attractions for second-home owners and other tourists are still traditional mountain activities (e.g. hiking, hunting, fishing, cross-country skiing on prepared trails, mountain skiing).

Destination Lygna – a rural area with metropolitan influence

Gran Municipality, which is located within a convenient commuting distance and influence from the capital, Oslo, nonetheless has mainly rural attributes, including employment in agriculture and a scattered settlement pattern. There are c.1600 second homes within the municipality boundaries (Statistisk sentralbyrå Citationn.d.,a). The focal area for new second-home development is Lygna, on a hillside with boreal forest, c.8 km to the north-east of the nearest main residential area. The area currently hosts a national cross-country skiing and biathlon centre, a hotel, a cafeteria, a convenience store, and a campsite.

A relatively newly approved municipal subplan includes more than 1000 new second homes. However, construction and development have long been in operation, and newly built second homes already in use are surrounded by building and construction activity.

In addition to a comprehensive conventional second-home development in Lygna, a new vision for ‘climate-positive second-home development’ (cited from the developer’s prospectus accessed in 2019) was initiated by landowners in collaboration with Gran municipality. In this case, the ‘climate-positive’ concept implies that each second home should produce renewable energy, thereby compensating for its total energy footprint and greenhouse gas emissions from the building process and owners’ transport, and offsetting the total use of the second home during its lifetime. The plan includes adding produced excess energy to the national grid.

Methods

Research design and data collection

To address the research questions, triangulation of qualitative methods was applied, supplemented with official macrodata from Statistics Norway. The main data source was in-depth, individual interviews with key stakeholders and other actors. They typically represented the political and administrative level in the cases, the state and regional county administrations, and landowners in the case study areas (). Additionally, representatives of local users, outdoor recreation associations, tourism and trade businesses, and second-home associations were interviewed. Individual interviews were conducted with 13 Sjusjøen stakeholders, 6 Renåfjellet stakeholders, and 8 Lygna stakeholders. A further 6 interviewees participated in one focus group discussions in Sjusjøen, and 12 participated in two different focus group discussions in Renåfjellet (). The stakeholders were selected based on the local context, and their involvement and influence over the respective destinations’ development. Thus, their position varied between destinations, as the importance of successful second-home development differed significantly in the three municipalities.

Table 1. Description of data collection and key stakeholders

A semi-structured guide was used in all interviews, which focused on challenges and opportunities related to the development of the respective second-home area, including local responsibilities and cooperation, the area’s potential as a year-round destination, and sustainability issues (social, economic, and environmental). The participants were not specifically asked to define the word ‘sustainability’, but different matters based on the subject’s three pillars were addressed. Sustainability was later used as an analytical concept in the data analysis. The interviews were carried out between mid-2018 and mid-2020, and each interview lasted c.1–2 hours. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. In this article, representative quotes from the participants and from published sources have been translated into English by the authors.

The interviews were supplemented with document studies. The documents comprised land use and zoning plans, and consultation input regarding second-home development in the case study areas. In addition, newspaper articles and Facebook posts in relevant groups were analysed to ensure inclusion of prevailing perceptions on sustainability and second-home development. Details of the studied documents are listed in . Since most of the significant actors were interviewed, theoretical data saturation was achieved, and additional interviews did not provide further information but confirmed previous insights. Local and regional context data () were accessed through publicly available macrodata from Statistics Norway and were used to supplement the collected data.

Table 2. Document studies

Table 3. Municipality facts relating to the three case destinations in 2020

Data analysis

The data were analysed thematically. According to Braun & Clarke (Citation2012), thematic analysis is useful in qualitative research for identifying patterns of meaning regarding how a certain topic is described. First, the data were organized into themes, then similar themes were merged, and themes with insufficient or no evidence were removed. Descriptive and striking quotes from the data were selected to illustrate the detected patterns, which are presented in the Results section. The identified themes were further analysed to identify connections and how the themes fitted into a narrative. The data analyses were performed using NVivo12 (©2021alfasoft).

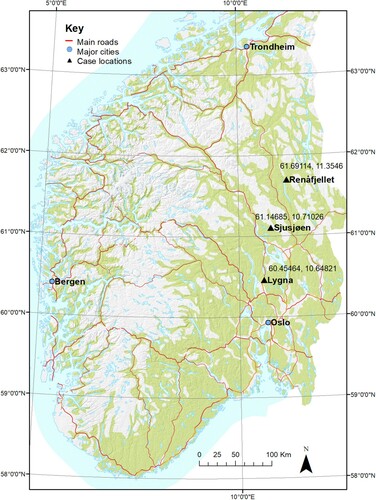

Conceptual foundation

Based on an article on the impact, planning, and management of second homes co-authored by Müller et al. (Citation2004), Back & Marjavaara developed a typology of second-home landscapes that ‘form a theoretical concept mapping spatial differences in impacts of second-home tourism’ (Back & Marjavaara Citation2017, 4). Back (Citation2020, 1328) later concluded that the ‘results reveal considerable variance between locations and argues for more context-aware second-home research’. To elaborate this angle further, we applied a two-dimensional model with continuums for geographical dimensions (centrality versus periphery) and cultural dimensions (urbanity versus rurality) as a conceptual foundation for our discussion. The two dimensions allow for classifying Norwegian municipalities located outside cities into four archetypes based on their main resource base and the municipality’s capacity to assess, plan, and implement adequate measures to deal with specific sustainable development challenges and opportunities (Frisvoll Citation2018). The capacities include access to available human resources and competence, as well as institutional capacity to engage in strategic planning (beyond day-to-day operations) and, not least, decision-making authority to access and implement relevant and adequate measures. According to Frisvoll (Citation2018), these capacities vary with location on the geographical and cultural dimensions. Planning and development of second homes in Norway is almost entirely a municipal matter, which makes ‘local context’ an important dimension also in sustainability issues (Hiltunen et al. Citation2013). The four archetypes in our model () are:

Municipalities in Decline – Municipalities are characterized by a long-term decline in population and employment, weak industry structure, and employment that rests heavily on public administration and agriculture. These locations score high on both the rurality and periphery dimensions (the far upper left quadrant in ). Rendalen is a typical municipality in decline.

Manufacturing Booms – Municipalities are characterized by industry activities based on nearby exploitable natural resources (e.g. energy for power-intensive industries, suitable quality water for fish farming, mineral resources for mining). The numbers and types of industrial activities are often limited. The locations generally score high on the rurality and periphery dimensions but less significantly than municipalities in decline (in both left quadrants, but mainly in the upper one in ). These municipalities are typically in remote arms of fjords, surrounded by steep mountains and nearby hydropower plants, and are not very feasible for second-home tourism.

Recreational Villages – These may be either rural or urban municipalities located within weekend travel distances (i.e. travel time from place of residence to second home) from large, diversified labour markets in towns or cities. These municipalities have growth potential in second-home development, including new development, in amenity-rich areas and often within or in the vicinity of established tourist destinations (to the left side in the right quadrants in ). Sjusjøen is a typical recreational village in Ringsaker Municipality.

Within Commuting Distance – In common with the third archetype, the fourth archetype comprises rural or urban municipalities located within commuting distance from large, diversified labour markets in towns or cities (to the right side in the right quadrants in ). Development factors include vicinity of urban facilities and good living environments locally. Gran Municipality is an example of a municipality in this group.

Fig. 3. Two-dimensional model for the situations of municipalities outside cities (redrawn version of model by Frisvoll Citation2018, 3)

Results

As described in this section, the three cases represented distinctly different regional contexts, partly because of their combined location on the two dimensions in , which also have bearing on sustainability issues. We describe the sustainability challenges as they were perceived in their local context. Furthermore, we consider applicable and available means to deal with the challenges in each case.

Destination Sjusjøen

Sustainability challenges

Today, development in Sjusjøen as a second-home destination is mainly driven by two commonsFootnote1 and one limited company as landowners. Their strategy is to strengthen the area’s agglomerative distinctiveness. This is especially notable in the central parts of the destination area, yet the distribution of new developments and densifications has also resulted from land distribution and zoning between landowners. The findings from the interviews and documents indicated that regional authorities and second-home owners believed that landowners and other real estate developers had too much power:

We have little control over the second-home development. We can give recommendations, but not much more if it is not stated in the guidelines. Sustainable second-home development must be a responsibility of the municipalities and with a long-term perspective, but they do not take this seriously enough […] And then the municipality struggles when the zoning plan is accepted because it cannot order the developer to build in an environmentally friendly way. (County authority advisor on wildlife)

Second-home owners have increasingly questioned what they receive in return for their property tax. This has especially been the case when they have perceived that regulations and further developments favour landowners and developers without considering existing second-home owners:

The expansive development in Ringsaker’s mountain area is a sad example of how environmental and general outdoor recreation issues are being set aside to the benefit of strong economic interests. Ringsaker Municipality sees only property taxes and jobs, and it welcomes all activity that generates income. Money-rich investors also win because, as is well known, investing in real estate is more profitable than bank savings. Love of nature and landscape is not visible in the architecture of the new ‘second-home palaces’ that are popping up. (Second-home owner, Focus Group 1 Discussion)

Our request is therefore addressed to the politicians, ‘You are elected by the people to protect the interests of the public, with responsibility for following national guidelines.’ With the municipality’s [NOK] 115 million [EUR 11.5 million] in surplus and over 2000 second-home plots regulated in less vulnerable areas, it is unnecessary and wrong to defy the majority to satisfy a few who will ‘sacrifice’ [a specific area] for financial reasons. (Ringsaker Blad Citation2017)

Applicable and available means

The findings from interviews, public documents, and media analyses all pointed to conflict hot spots in Sjusjøen between economic development and social dimensions. As illustrated by the examples in the preceding subsection, the discussions and disagreements concern property conflicts, resource allocation, and, apparently, growth coalitions (Gill Citation2000) between local landowners, investors, and politicians, which are at the expense of second-home owners. It can certainly be argued that second-home owners’ objections to further development are a form of opposition characterized as ‘not in my backyard’. However, rapid, and not always gentle, development has changed the ambience completely in several older developments that have been subject to densification. While densification is generally regarded as a good environmental way of further developing second-home areas, it is also important to consider the effects on existing buildings and residents, as well as on attractiveness in the future.

Recently, local authorities have questioned whether the public/taxpayers, should pay an excess bill to upgrade waterworks and sewerage capacity, when such an investment lays the foundation for rapid, dense development and the associated profit potential for landowners.

Planning processes in Norway assume that information is provided to ‘affected parties’ and that the parties are actively involved in planning to ensure involvement and promotion of relevant objections. Involvement, participation, and access to relevant information may be challenging when affected parties reside elsewhere (i.e. second-home owners who are generally out of reach of local media or public information meetings), and therefore may escalate conflicts. In the Sjusjøen case, the municipal council’s change in the approved land-use plan opened a limited, but centrally located, area for development affecting nearby second-home owners and public access to the barren area. Although the objection deadline was well before political confirmation of the revised land-use plan, affected second-home owners claimed to know little or nothing about either this new political plan’s approval or the additional developments it allowed. Under the former land-use plan, the development would not have been allowed. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the need for municipalities to spread information to people staying within the municipality, regardless of permanent residence. This has led to a new use of SMS technology for distributing relevant information, a technology that may also be used to distribute information about municipal plans and propositions. Furthermore, SMS technology could be used to provide information in time to facilitate involvement and participation from all affected parties in the future.

A main challenge concerning the achievement of more sustainable development in Sjusjøen is to overcome controversies regarding the scope of development and zoning policies. The above-mentioned environmental issues at stake are also part of the conflict and should therefore not be ignored. These issues are partly addressed by densification and locating new construction below the treeline. However, a holistic approach to further development is obscured by the distribution among landowners of land available for further development.

Destination Renåfjellet

Sustainability challenges

Renåfjellet hosts a developed agglomeration of modern second homes. As described above in the section ‘Destination Renåfjellet – an area in a municipality in decline’, there is a significant number of traditional, low-tech cabins scattered throughout Rendalen Municipality. As a partial answer to the municipality’s declining population and to counteract job losses, a second-home agglomeration was established in Renåfjellet in the late 1980s to 1990s. This was partly a response to expected market preferences, as it seemed difficult to find buyers for scattered, low-standard plots. During an interview conducted in 2020, a representative of Rendalen Municipality informed that there were c.350 second homes in Renåfjellet, and a further 300 plots ready for construction.

The interviews highlighted and confirmed the need to maintain, and preferably increase, the municipality’s economic activities and development. The interviewees’ almost unanimous perception of the ‘sustainability’ concept can be illustrated by the following quotes:

A development generating profit. A potential for local businesses to generate income and profit, is what I call sustainable […] It must be something to build the future on. And to last for many years. (Participant in Focus Group Discussion 1)

A development of the community as an entity. A development that contributes to maintaining local settlement. (Focus Group Discussion 2)

Simply to make it possible for the next generation to keep on living here. That implies economic sustainability, and to maintain the social life, so you don’t have to travel to socialize, to keep up a living society. All three elements are important, that is economy and social life combined with the environment. (Focus Group Discussion 2)

Sustainability is an investment for long-term value added. (Focus Group Discussion 2)

second-home development is essential for the municipality and for the local businesses, as second-home development represents a more solid basis for existence […] The hope is that second-home development may generate some new residents in the future. (Politician)

Applicable and available means

Despite the obvious qualities of Renåfjellet, the ambitions for second-home development have suffered from limited market interest. Few participants questioned why that had been the case. This is a paradox that eventually will have to be addressed. Do relevant market segments find the destination attractive or are they even able to find it at all? As one interviewee said: ‘Rendalen is top secret’ (Leader of a business association, Focus Group Discussion 2).

Does the municipality have the power and ability to take a more active role in second-home development to support local actors, in order to sustain a feasibility study of local assets, market demand, and distribution channels? One private business manager, a former politician, stated:

Rendalen Municipality does an excellent job in many areas, except when it comes to business development. […] I think it’s due to lack of competence. […] The focus is on the day-to-day work, reporting, and administrating services, even though there has been a population decline of a thousand inhabitants since the mid-1980s. (Arbeidets Rett Citation2021)

Destination Lygna

Sustainability challenges

Lygna is a fairly new second-home destination in Gran Municipality. The area has already been exploited, especially for winter sports activities and road service facilities, but to a lesser extent for second homes. The new development is characterized by heavy construction activity. One aspect of the development was to introduce the concept of ‘climate-positive second homes’. As the traditional construction site developed, the climate-positive concept appeared somewhat out of place in the context of a fully facilitated agglomeration. Therefore, the commons’ main developer proposed regulating a new virgin area dedicated to climate-positive second homes. The proposal was finally approved following several rounds of planning committee meetings and municipal council meetings. A climate-positive prototype is planned to be set up to promote sales. When realized at full scale, the plan will yield c.100 new buildings.

As Gran Municipality is in Oslo’s area of influence and within commuting distance of the city, economic or business dimensions are not significantly challenging. Moreover the second-home development in Lygna has not yet given rise to social dimension issues. Instead, Gran is generally focused on environmental issues. Among other initiatives, the municipality, in partnership with the regional council (Regionrådet for Hadeland), has established a temporary position as a climate coordinator to guide the region’s municipalities (i.e. Gran, Lunner and Jevnaker) on these issues. This underlines the authorities’ environmental concerns regarding the impacts of second-home development in Lygna.

The main development area in Lygna gives a very strong impression of nature transformation, but one with solutions that appear to have been accepted by the authorities, developers, and the market. This is probably due to the ongoing process of developing Lygna as a second-home tourism destination. There are no longer any major conflicts between existing users and further development. However, this does not mean there are no landscape or environmental issues. Many people want more information about the long-term consequences of relatively extensive second-home development, as shown by the following quote from a local resident:

Large nature areas are in the process of being reduced to second-home plots. Second-home development has many obvious benefits for the local community, but the consequences for nature and forests are obviously negative. When is enough enough? (Hadeland Citation2019a)

Applicable and available means

Sustainability issues related to second-home development in Gran Municipality do not seriously address either social or economic issues. Thus, from a local perspective, most sustainability achievements are likely to be focused on the ecology and conservation pillar. This perspective is reinforced by Gran’s location within the influence of the densely populated Oslo region. Such proximity may intensify pressure on the environment and thus reduce the recreational values for local and non-local users, as well as increase greenhouse gas emissions. Market access and, to date, stable snow conditions have been arguments for the new agglomeration and its climate-positive concept.

The new alternative climate-positive development concept amplifies the above-mentioned issues due to the use of virgin areas, which hitherto have been subject to building restrictions in politically approved valid planning documents. There is also scepticism regarding the scope of such development. It can certainly be argued that developing climate-positive second homes is better for the climate and the environment compared with developing conventional second homes. However, questions have been raised about how the climate gain will be realized in practice, and whether expressed climate concerns are just a form of greenwashing in order to offer even more second homes in an attractive area while at the same time avoiding major landscape encroachment. There may also be questions regarding the relationship between the climate and the environment, and whether local measures have major sustainability impacts. The significance of the claimed climate and sustainability impacts was questioned by a resident, who was member of Friends of the Earth Norway and spoke ironically about greenwashing regarding the recent political support of the climate-positive second-home development:

We thought the threat to natural diversity had become large enough in Gran. However, a large second-home area is still needed, so the developers can figure out how 100 new second homes can help the climate. (Hadeland Citation2019b)

Discussion

Sustainable development in various contexts – same but different?

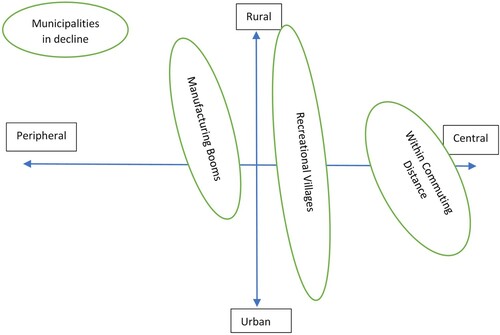

Our three cases reflect a cross-section of the types of variance in regional contexts that must be considered when discussing specific ‘sustainable development’ measures in different contexts. This point is illustrated in and , which serve as a starting point for such a discussion.

Overall, our analysis demonstrates that sustainability issues are manifested and dealt with in different ways in the three communities and it illustrates that the three sustainability pillars are addressed according to the specific features that each destination site and municipality faces.

Until recently, the rather exclusive focus on economic development in Sjusjøen supplanted consideration of the growing social and environmental concerns. Rather, to the extent environmental and social issues are highlighted, the focus tends to justify economic motives and aims, rather than vice versa. In other words, economic interests and aims are not framed by assessments of environmental and social effects. As such, the case of Sjusjøen falls within the category of a general critique of tourism development and sustainability (Hall Citation2013; Saarinen Citation2014). However, today there are clear signs of changes, as conflicts have emerged between landowners and developers on the one hand, and local recreationists and early cabin owners on the other hand. As illuminated by the situation in Sjusjøen, the social and equity dimensions in particular have become prominent.

In contrast to Sjusjøen, the sustainability discourses in Lygna in Gran Municipality do not address either social or economic issues as much as they address environmental issues. Gran is located within commuting distance of diversified labour markets, and the residents themselves benefit from good living conditions in a rural region, proximity to urban facilities and good local recreational amenities. Proximity to the capital region also entails a market potential for future second-home development. This may place additional pressures on the environment in this municipality and others of the same type, and therefore the ecology and conservation pillar has received much attention. As current second-home development does not interfere with established old-fashioned second homes and outdoor recreation landscapes, social conflicts appear to be much less prominent in comparison with the Sjusjøen case.

In contrast to both Lygna in Gran Municipality and Sjusjøen in Ringsaker Municipality, the case of Renåfjellet in Rendalen Municipality represents municipalities that perceive second-home development as a crucial means for counteracting a precarious situation of declining populations, scarce or limited job opportunities, and existing employment opportunities being dominated by the public sector. Accordingly, the main concern in Rendalen is to initiate a successful process of investment in second-home development, and thus social and environmental concerns have received little attention to date. However, this might need reassessment if the current second-home development strategy becomes successful.

In Rendalen, further development of second homes has stalled. It may be reasonable to assume that a limited municipal administration with many imposed administrative tasks has limited opportunities to address long-term strategic challenges. If so, this could limit the municipality’s potential and ability to support and take a lead in development measures. Furthermore, it might be challenging the municipality to gain access to the right competence in public positions. Moreover, small, peripheral, rural municipalities are limited in terms of access to, and influence on, decisions made at higher administrative and political levels (Frisvoll Citation2018).

According to the three-pillar sustainability model, our cases may be arranged in the corners of a triangle according to their current main sustainability challenges (cf. ). Because the cases belong to different locality clusters, it is possible to link their sustainability challenges to specific locations, as illustrated by the ‘centre versus periphery’ and ‘urban versus rural’ dimensions (). Our analysis indicates that while sustainability challenges are present in all cases, they are also different, as political power and other resources (e.g. access to relevant professional competence and networks, as well as to administrative and economic resources) will define their scope of action and realistic, achievable results. The sustainability challenges that we consider are likely to require the most attention in each of the three second-home contexts shown in the ovals in .

Tourism destinations are usually a complex mix of actors and stakeholders with diverse interests (Sørensen & Grindsted Citation2021). If there is no leader with the power to commit stakeholders to engage in joint actions or reach agreement on common measures, it may be difficult to reach a sustainable implementation agreement. This in turn indicates and would reinforce the municipality’s role in, and responsibility for, developing and strengthening community aspects, which require efforts and resources beyond daily operations and maintenance through standard administrative tasks.

Conclusions

In this study, we have demonstrated that specific local contexts must be assessed in order to understand which sustainability dimension is likely to require the most attention in each of the studied case and why. While second-home development in all three analysed cases have been motivated by public and private economic growth, there have been differences in scale with respect to the urgency of the attention to economic, environmental, or social aspects of sustainability, respectively. This in turn reflects how the three different sustainability pillars are perceived, weighted, and handled in the specific local contexts. Accordingly, to assess sustainability challenges and adequate measures, our findings support the notion that measures must rest on a solid fundament of knowledge of the actual situation, based on a destination’s location, the specific features of local societies, public plans, and available resources. We argue that these available resources may vary systematically with geographical location and cultural affiliation of communities and municipalities. We have focused on the scope of power and influence held by various local stakeholders, including public authorities, and our cases demonstrates the importance of the municipality taking the lead in defining the sustainability challenges that may result from second-home development. However, the measures and instruments available for municipalities in general limit their scope of action, and we find that measures are also likely to differ depending on whether the potential for the most sustainability benefit is found in limiting or promoting second-home development.

As location influences public authorities’ resources and capacity to deal with sustainability challenges (Back Citation2021), and as long as second-home development is not sufficiently integrated into long-term planning (Overvåg Citation2011; Skjeggedal & Overvåg Citation2014), much of the detailed decision-making at the level of zoning plans is left to landowners and developers, giving them somewhat disproportionate power. This is particularly evident in the case of Sjusjøen, where strong landowners have the potential to control development ‘out of sight’ of the municipality’s population centres. In rural and peripheral mountains, as in the case of Renåfjellet, where business actors and entrepreneurs themselves do not have enough power or resources to initiate development, we find that local authorities’ capacities may be especially important. These conclusions are based on our in-depth study of three cases, representing distinct second-home geographies. It would be valuable for these analyses to be replicated with other cases in similar settings.

In closing, and consistent with the generally increased attention paid to sustainability and climate change, measures on individual, local, regional, national, and global levels must be implemented (Gössling et al. Citation2009; Williams & Ponsford Citation2009; Bramwell et al. Citation2017). A focus on greenhouse gas emissions and climate actions is important but must not one-sidedly overshadow other sustainability measures that may provide greater benefits locally, such as effects on biodiversity, social equity, relations and identities, and precarious community development needs. Furthermore, locally accessible resources and power options will set the limits for implementing effective climate actions with significant global impacts. Accordingly, how local contexts influence sustainability issues is a crucial research focus.

Acknowledgements

The work for this paper was supported by Kompetanse-, universitets- og forskingsfondet i Oppland AS, the Eastern Norway Research Institute, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, and the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research. We thank the participants from the three municipalities: municipality and county politicians, business actors, non-government organization employees and second-home owners. We also thank the reviewers, as the article has improved significantly as a consequence of their comments.

Notes

1 In this article the term ‘commons’ refers to organizations with a shared use of common resources, such as grazing.

References

- Åkerlund, U., Lipkina, O. & Hall, C. M. 2015. Second home governance in the EU: In and out of Finland and Malta. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 7(1), 77–97.

- Adamiak, C., Pitkänen, K. & Lehtonen, O. 2017. Seasonal residence and counterurbanization: The role of second homes in population redistribution in Finland. GeoJournal 82, 1035–1050.

- Andersen, I.M.V., Blichfeldt, B.S. & Liburd, J.J. 2018. Sustainability in coastal tourism development: An example from Denmark. Current Issues in Tourism 21(12) 1329–1336.

- Arbeidets Rett. 2021. Retter krass kritikk mot kommunen og mener han ble skjelt ut av ordføreren: - Det er ikke sant. 10 May 2021. https://www.retten.no/retter-krass-kritikk-mot-kommunen-og-mener-han-ble-skjelt-ut-av-ordforeren-det-er-ikke-sant/s/5-44-539847 (accessed 10 June 2022).

- Arnesen, T. & Ericsson, B. 2013. Policy responses to the evolution in leisure housing: From the plain cabin to the high standard second home (The Norwegian case). Roca, Z. (ed.) Second Home Tourism in Europe: Lifestyle Issues and Policy Responses, 285–306. London: Routledge.

- Arnesen, T., Overvåg, K., Skjeggedal, T. & Ericsson, B. 2012. Transcending orthodoxy: Leisure and the transformation of core – periphery relations. Danson, M. & de Souza, P. (eds.) Regional Development in Northern Europe. Peripherality, Marginality and Border Issues in Northern Europe, Regions and Cities, 182–195. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Back, A. 2020. Temporary resident evil? Managing diverse impacts of second-home tourism. Current Issues in Tourism 23(11), 1328–1342.

- Back, A. 2021. Endemic and diverse: Planning perspectives on second-home tourism’s heterogeneous impact on Swedish housing markets. Housing, Theory and Society. doi:10.1080/14036096.2021.1944906

- Back, A. & Marjavaara, R. 2017. Mapping an invisible population: The uneven geography of second-home tourism. Tourism Geographies 19(4), 596–611.

- Bramwell, B., Higham, J., Lane, B. & Miller, G. 2017. Twenty-five years of sustainable tourism and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism: Looking back and moving forward. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25(1), 1–9.

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2012. Thematic analysis. Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D. & Sher, K.J. (eds.) APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological, 57–71. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Brida, J.G., Osti, L. & Santifaller, E. 2011. Second homes and the need for policy planning. Tourismos 6(1), 141–163.

- Butler, R. 2019. Contributions of tourism to destination sustainability: Golf tourism in St Andrews, Scotland. Tourism Review 74(2), 235–245.

- Cucculelli, M. & Goffi, G. (2016). Does sustainability enhance tourism destination competitiveness? Evidence from Italian destinations of excellence. Journal of Cleaner Production 111, 370–382.

- Czarnecki, A. 2018. Uncertain benefits: How second home tourism impacts community economy. Hall, M.C. & Müller, D.K. (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Second Home Tourism and Mobilities, 122–133. London: Routledge.

- Eimermann, M., Agnidakis, P., Åkerlund, U. & Woube, A. 2017. Rural place marketing and consumption-driven mobilities in Northern Sweden: Challenges and opportunities for community sustainability. Journal of Rural Community Development 12(2-3), 114–126.

- Ellingsen, W. 2017. Rural second homes: A narrative of de-centralisation. Sociologia Ruralis 57(2), 229–244.

- Ellingsen, W. & Arnesen, T. 2018. Fritidsbebyggelse-fra byggesak til stedsutvikling. Journal of Geography 63(3), 154–165.

- Ericsson, B. [2006]. Fritidsboliger – utvikling og motiver for eierskap. http://www.utmark.org/utgivelser/pub/2006-1/art/Ericsson_Utmark_1_2006.html (accessed 24 May 2022).

- Ericsson, B., Skjeggedal, T., Arnesen, T. & Overvåg, K. 2011. Second Homes i Norge – bidrag til en nordisk utredning. Lillehammer: Østlandsforskning.

- Ericsson, B., Overvåg, K. & Hagen, S.E. 2012. Å bo flere steder – Fritidsboliger i Indre Skandinavia. Olsson, E., Hauge, A. & Ericsson, B. (eds.) På gränsen – Interaktion, attraktivitet och globalisering i Inre Skandinavien, 149–167. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

- Farstad, M. 2016. Relasjonelle kvaliteter i bygd og by: Stereotypiene møter innbyggernes erfaringer. Haugen, M.S. & Villa, M. (eds.) Lokalsamfunn, 260–282. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Farstad, M. & Rye, J.F. 2013. Second home owners, locals and their perspectives on rural development. Journal of Rural Studies 30, 41–51.

- Fennell, D.A. & Cooper, C. 2020. Sustainable Tourism: Principles, Contexts and Practices. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

- Flognfeldt, T. 2004. Second homes as a part of a new lifestyle in Norway. Hall, C.M. & Müller, D.K. (eds.) Tourism, Mobility and Second Homes: Between Elite Landscape and Common Ground, 233–243. Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

- Fredman, P. & Tyrväinen, L. 2010. Frontiers in nature-based tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 10(3), 177–189.

- Frisvoll, S. 2018. Hele Norge skal leve? Når manglende kapasitet hemmer utvikling. Notat nr. 2/18. Trondheim: Ruralis.

- Gallent, N., Mace, A. & Tewdwr-Jones, M. 2005. Second Homes: European Perspectives and UK Policies. Chippenham: Ashgate.

- Gill, A. 2000. From growth machine to growth management: The dynamics of resort development in Whistler, British Columbia. Environment and Planning A 33, 1083–1103.

- Gössling, S., Hall, C.M. & Weaver, D. 2009. Sustainable Tourism Futures: Perspectives on Systems, Restructuring and Innovations. New York: Routledge.

- Gran kommune. n.d. Klimapådriver for Hadeland. https://www.gran.kommune.no/klimapaadriver-for-hadeland.475532.no.html (accessed 10 June 2022).

- Hadeland. 2019a. Håvard Lucasen: Når er nok nok? 27 December 2019. https://www.hadeland.no/havard-lucasen-nar-er-nok-nok/o/5-21-680579 (accessed 10 June 2022).

- Hadeland. 2019b. Øyvind Kvernvold Myhre: Klimahyttene og julenissen. 14 December 2019. https://www.hadeland.no/oyvind-kvernvold-myhre-klimahyttene-og-julenissen/o/5-21-677279 (accessed 10 June 2022).

- Halfacree, K. 2012. Heterolocal identities? Counter-urbanisation, second homes, and rural consumption in the era of mobilities. Population Space and Place 18(2), 209–224.

- Hall, C. M. 2013. Framing behavioural approaches to understanding and governing sustainable tourism consumption: Beyond neoliberalism, ‘nudging’ and ‘green growth’? Journal of Sustainable Tourism 21(7), 1091–1109.

- Hall, C.M. 2014. Second home tourism. Tourism Review International 18(3), 115–236.

- Hall, C.M. 2015. Second homes planning, policy and governance. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 7(1), 1–14.

- Hall, C.M., Gössling, S. & Scott, D. 2015. Tourism and sustainability: Towards a green(er) tourism economy. Hall, C.M., Gössling, S. & Scott, D. (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability, 490–515. London: Routledge.

- Hidle, K., Cruickshank, J. & Nesje, L.M. 2006. Market, commodity, resource, and strength: Logics of Norwegian rurality. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 60(3), 189–198.

- Hidle, K., Ellingsen, W. & Cruickshank, J. 2010. Political conceptions of second home mobility. Sociologia Ruralis 50(2), 139–155

- Hiltunen, M.J. 2007. Environmental impacts of rural second home tourism – case Lake District in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 7(3), 243–265.

- Hiltunen, M.J., Pitkänen, K., Vepsäläinen, M. & Hall, C.M. 2013. Second home tourism in Finland: Current trends and eco-social impacts. Roca, Z. (ed.) Second Home Tourism in Europe: Lifestyle Issues and Policy Responses, 165–198. London: Routledge.

- Hoogendoorn, G. & Visser, G. 2011. Economic development through second home development: Evidence from South Africa. Tijdschift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 102(3), 275–289.

- Hoogendoorn, G. & Marjavaara, R. 2018. Displacement and second home tourism: A debate still relevant or time to move on? Hall, M.C. & Müller, D.K. (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Second Home Tourism and Mobilities, 98–112. London: Routledge.

- Kaltenborn, B.P., Andersen, O. & Nellemann, C. 2007. Second home development in the Norwegian mountains: Is it outgrowing the planning capability? The International Journal of Biodiversity Science and Management 3(1), 1–11.

- Keiner, M. 2005. History, Definition(s) and Models of Sustainable Development. Zurich: ETH.

- Long, D.P. & Hoogendoorn, G. 2013. Second homeowner’s perceptions of a polluted environment: The case of Hartbeespoort. South African Geographical Journal 95(1), 91–104.

- McCool, S., Butler, R., Buckley, R., Weaver, D. & Wheeler, B. 2013. Is concept of sustainability utopian: Ideally perfect but impracticable? Tourism Recreation Research 38(1), 213–242.

- Medalen, T. 2008. Bærekraftig planlegging og governance – teori og praksis. Norsk forening for bolig- og byplanlegging. https://boby.no/wp-content/uploads/2008/12/Medalen_NPM_2008.pdf (accessed 24 May 2022).

- Miljødirektoratet. 2019. Klimapositivt hytteliv på Lygna. https://www.miljodirektoratet.no/ansvarsomrader/klima/for-myndigheter/kutte-utslipp-av-klimagasser/klimasats/2016/klimapositivt-hytteliv-pa-lygna/ (accessed 10 June 2022).

- Müller, D.K. 2007. Second homes in the Nordic countries: Between common heritage and exclusive commodity. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 7(3), 193–201.

- Müller, D.K. 2011. Second homes in rural areas: Reflections on a troubled history. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 65(3), 137–143.

- Müller, D.K. 2021. 20 years of Nordic second home-tourism research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 21(1), 91–101.

- Müller, D.K. & Hall, C.M. 2018. From common ground to elite and commercial landscape. Hall, C.M. & Müller, D.K. (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Second Home Tourism and Mobilities, 115–121. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Müller, D.K., Hall, C.M. & Keen, D. 2004. Second home tourism impact, planning and management. Hall, C.M. & Müller, D.K. (eds.), Tourism, Mobility and Second Homes: Between Elite Landscape and Common Ground, 15–32. Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

- Næss, P., Xue, J., Stefansdottir, H., Steffansen, R. & Richardson, T. 2019. Second home mobility, climate impacts and travel modes: Can sustainability obstacles be overcome? Journal of Transport Geography 79: Article 102468.

- Øian, H. (2013). Wilderness tourism and the moralities of commitment: Hunting and angling as modes of engaging with the natures and animals of rural landscapes in Norway. Journal of Rural Studies 32, 177–185.

- Overvåg, K. 2009a. Second Homes in Eastern Norway: From Marginal Land to Commodity. Doctoral Thesis. Doktoravhandlinger ved NTNU, 1503–8181. Trondheim: NTNU.

- Overvåg, K. 2009b. Second homes and urban growth in the Oslo area, Norway. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 63(3), 154–165.

- Overvåg, K. 2010. Second homes and maximum yield in marginal land: The re-resourcing of rural land in Norway. European Urban and Regional Studies 17(1), 3–16.

- Overvåg, K. 2011. Second homes: Migration or circulation? Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 65(3), 154–164.

- Overvåg, K. & Berg, N.G. 2011. Second homes, rurality and contested space in eastern Norway. Tourism Geographies 13(3), 417–442.

- Paris, C. 2014. Critical commentary: Second homes. Annals of Leisure Research 17(1), 4–9.

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I., Andrades-Caldito, L. & Sánchez-Rivero, M. 2015. Is sustainable tourism an obstacle to the economic performance of the tourism industry? Evidence from an international empirical study. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 23(1), 47–64.

- Rahbek Christensen, L. 1997. Hver vore veje. Købehavn: Museum Tusculanums forlag.

- Ringsaker Blad. 2015. Byggekontroll avdekker lovbrudd på byggeplasser i Ringsakfjellet – Mange underbetales i fjellet. 24 September 2015. https://www.ringsaker-blad.no/nyheter/okonomi-og-naringsliv/arbeidsliv/mange-underbetales-i-fjellet/s/5-79-33861 (accessed 10 June 2022).

- Ringsaker Blad. 2017. Hyttebygging i Lunkelia fortsatt ikke vedtatt! 13 March 2017. https://www.ringsaker-blad.no/debatt/kommentar/lunkelia/hyttebygging-i-lunkelia-fortsatt-ikke-vedtatt/o/5-79-83093 (accessed 10 June 2022).

- Ringsaker kommune. 2020. Referat fra møte mellom velforeningene i Ringsakerfjellet og Ringsaker kommune. 23 October 2020. https://filer.romasenvel.no/2021/Vedlegg%203%20-%20Til%20%C3%A5rsberetning%20-%20Referat%20fra%20m%C3%B8te%20mellom%20velforeningene%20i%20Ringsakerfjellet%20og%20Ringsaker%20kommune%2023.10.2020_2_P.pdf (accessed 10 June 2022).

- Robertsson, L. & Marjavaara, R. 2015. The seasonal buzz: Knowledge transfer in a temporary setting. Tourism Planning and Development 12(3), 251–265.

- Saarinen, J. 2014. Critical sustainability: Setting the limits to growth and responsibility in tourism. Sustainability 6(1), 1–17.

- Sheard, N. 2019. Vacation homes and regional economic development. Regional Studies 53(12), 1696–1709.

- Skjeggedal, T. & Overvåg, K. 2014. Fjellkommuner i Norge: Bygdesamfunn eller verneområder? Tidsskriftet Utmark (1&2). https://utmark.org/Portals/utmark/utmark_old/utgivelser/pub/2014-1%262%26S/spes/Skjeggedal_Overvaag_UTMARK_1%262%26S_2014.html (accessed 24 May 2022).

- Skogen, K., Krange, O. & Figari, H. 2017. Wolf Conflicts: A Sociological Study Vol. 1. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Sømme, A. & Langdalen, E. 1965. Fjellbygd og feriefjell. Oslo: JW Cappelen.

- Sørensen, F. & Grindsted, T.S. 2021. Sustainability approaches and nature tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research 91: Article 103307.

- Statistisk sentralbyrå. n.d.,a. Bygningsmassen: 03174: Eksisterende bygningsmasse. Fritidsbygg, etter bygningstype (K) 2001–2022. https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/03174 (accessed 10 June 2022).

- Statistisk sentralbyrå. n.d.,b. Befolkning: 01222: Endringar i befolkninga i løpet av kvartalet, for kommunar, fylke og heile landet (K) 1997K4 – 2022K1. https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/01222 (accessed 10 June 2022).

- St.meld. nr. 21 (2004–2005). Regjeringens miljøvernpolitikk og rikets miljøtilstand. Oslo: Klima- og miljødepartementet.

- Støen, O.G., Wegge, P., Heid, S., Hjeljord, O. & Nellemann, C. 2010. The effect of recreational homes on willow ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus) in a mountain area of Norway. European Journal of Wildlife Research 56(5), 789–795.

- Sund, T. 1948. ‘Sommer-Bergen’: Avisenes adresseforandringer som vitnesbyrd om bergensernes landopphold sommeren 1947. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift 12(2), 92–103. doi: 10.1080/00291954808551651

- Velvin, J., Kvikstad, T.M., Drag, E. & Krogh, E. 2013. The impact of second home tourism local economic development in rural areas in Norway. Tourism Economics 19(3), 689–705.

- Williams, P.W. & Ponsford, I.F. 2009. Confronting tourism’s environmental paradox: Transitioning for sustainable tourism. Futures 41(6), 396–404.