ABSTRACT

Creativity and geography have received little attention in the literature on responsible innovation. To address these shortcomings, the article places responsible innovation explicitly in a territorial and non-technocentric context by exploring how artist-led social innovation takes ‘responsibility for place’. The article is guided by the following research question: How can artist initiatives shape sustainable regional development in peripheral areas? To address this research question, the author draws on a conceptualization of artist-led social innovation processes geared to ‘deperipheralization’ that is applied to study two initiatives – Ifö Center in Bromölla, Sweden, and Rjukan Solarpunk Academy, in Rjukan, Norway – situated in peripheral old industrial towns. The study reveals a variety of ways by which artists can be agents of change that transform places but at the same time take responsibility for inclusion and participation. The author concludes that through social innovation, artists' initiatives can empower local citizens and other actors to experiment collectively with unconventional ideas related to social and environmental sustainability and take responsibility for place. The social innovations studied have enacted responsibility for development objectives that are intrinsically significant due to an ethos of care in both a temporal sense (care for future) and a spatial sense (care for place).

Introduction

Responsible innovation epitomizes the wide societal focus and relevance of innovation (Schot & Steinmueller Citation2018; Uyarra et al. Citation2019). Increasingly, the rationale and purpose of innovation are tied to broader development objectives such as the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (Mazzucato et al. Citation2020), while at the same time opening up for more heterodox forms of innovation beyond firm-led innovation (e.g. social innovation and innovation in the public sector). A key contribution of the responsible innovation literature relates to the development (and use) of four guiding principles in innovation processes meant to safeguard collective stewardship and commitment of care for the future, namely anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness (Stilgoe et al. Citation2013). At the same time, responsible innovation is criticized for being procedural, technocentric, and universalistic (Jakobsen et al. Citation2019). While focusing primarily on guidelines and rules, far less attention is paid to the actual capabilities required to innovate responsibly (Coenen & Morgan Citation2020). Related to this, the role of creativity in responsible innovation has received surprisingly little attention.

To address these shortcomings, this article seeks to put responsible innovation explicitly in a territorial and non-technocentric context by exploring how artist-led social innovation takes ‘responsibility for place’. The article investigates bottom-up, contemporary arts and culture initiatives that introduce artistic methods of engagement to envision and enact sustainable regional futures in peripheral areas. In much of the literature on regional development, creativity, and arts is associated with the larger cities and urban areas. In this discourse, there is a predominant focus on culture and arts as sources of innovation, as being instrumental to economic growth, and as being driven by creative industries and attraction of talent and human capital (Scott Citation2010). This perspective became further popularized through the highly influential ‘creative class’ concept (Florida Citation2002). In exploring alternative approaches to such an urban and instrumentalist bias, this article explicitly considers social innovation, responsibility for place, and creativity in the context of peripheral areas. In doing so, the article furthers our understanding of how artists' initiatives can contribute to transformation processes in peripheral places by taking responsibility for inclusion, engagement, and participation. The article is guided by the following research question: How can artist initiatives shape sustainable regional development in peripheral areas?

To address the research question, the article draws on a conceptualization of artist-led social innovation processes geared to deperipheralization that is applied to study two initiatives – Ifö Center in Bromölla, Sweden, and Rjukan Solarpunk Academy, in Rjukan, Norway – both of which are situated in peripheral old industrial towns. In aligning with a key premise of responsible innovation (Stilgoe et al. Citation2013), both initiatives explicitly aim to take care of the future through collective stewardship of innovation in the present.

This article proceeds as follows. The next section situates the article in a broader theoretical perspective about innovation in the periphery, discusses the main concepts of responsible and social innovation, and elaborates on the role of arts and creativity. The Methods section introduces the methodological approach. The first case analysis, is presented in the section ‘Ifö Center’, and the second case analysis is presented in the section ‘Rjukan Solarpunk Academy’. The article ends with the section ‘Conclusions’.

Theoretical perspective

Periphery and innovation

Until recently, most of the literature on the geography of innovation has regarded peripheral areas as innovation backwaters, primarily defined by the deficits and weaknesses in their regional innovation systems, such as lack of innovative firms, R&D activity, innovation skills, networks, and institutional thickness (Eder Citation2019). These have been portrayed as ‘the places that don’t matter’ in contemporary knowledge-based economies (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018), which stand in stark contrast to innovation dense ‘creative cities’ (Florida Citation2002; Scott Citation2006).

‘Periphery’ has been a well-established theoretical concept in human geography. It was introduced at the beginning of the 20th century and became synonymous with the outskirts or ‘fringe’ of a city, region, or nation, based on the distance from a centre and standing in contrast to the core (Kühn Citation2015; Stenbacka & Heldt Cassel Citation2020). This core-periphery duality has taken a stronghold in our understanding of geographies of innovation, shaping a discourse in which core localities are considered superior in terms of technological, economic, and social innovation (Moulaert & Sekia Citation2003; Shearmur et al. Citation2016; Pugh & Dubois Citation2021). Implicitly, the periphery lags behind, as knowledge and generative interactions, innovation, and creativity are all tied to ‘the urban’ (Shearmur Citation2017). What is left for the periphery is a ‘no-innovation’ narrative.

Glückler et al. (Citation2022) criticize the conflation between periphery and non-innovative because such assumptions build on a narrow economic and instrumental perspective on innovation. Various scholars (Kühn Citation2015; Pugh & Dubois Citation2021) have called for a more holistic approach towards periphery across economic, environmental, and sociocultural and political themes, as well as one that acknowledges its potential – a space for opportunity and not just a liability (Rodríguez-Pose & Fitjar Citation2013; Glückler Citation2014; Hautala Citation2015; Grabher Citation2018). Empirical analyses have, for example, pointed to the innovativeness of small-scale business within cultural industries and climate change solutions in a peripheral context, and how remoteness is valued as something positive in, for example, tourism (Stenbacka & Heldt Cassel Citation2020), which can even shape regional and national identities (Sörlin Citation1999). Also in policy, there are examples where rural development explicitly targets progressive objectives for regional innovation policies, such local participation, social innovation, and communality, as in the case of Finnish vitality policy (Makkonen & Kahila Citation2021). Importantly, studies have found that peripheries can be sources of originality (Glückler et al. Citation2022) and creativity (Hautala Citation2015; Fitjar & Jøsendal Citation2016; Grabher Citation2018), constituting sites for novelty creation that challenges centre-based mainstream perspectives and practices (Hautala & Jauhiainen Citation2018; Pugh & Dubois Citation2021).

In addition, there is growing empirical evidence that much innovation in peripheral areas is overlooked because firms in the periphery innovate differently, drawing on other networks, resources, and strategies than firms in urban centres (Fitjar & Rodríguez-Pose Citation2011; Fritsch & Wyrwich Citation2021). Morgan & Henderson (Citationin press) go even further and argue for a wider conceptualization of relevant forms and processes of innovation in peripheral areas, not just limited to innovation in the firm. They highlight the potential for a wider cast of actors and processes to engage in social and other forms of innovation. In recent years, a suite of novel conceptualizations of innovation has emerged, notably responsible and social innovation, which engages with different dimensions of sustainability in and of innovation (Coenen & Morgan Citation2020).

In this article, I adopt a ‘periphery-as-process’ perspective (Stenbacka & Heldt Cassel Citation2020) and consider how artist-led social innovation contributes to deperipheralization. In doing so, I seek avoid a reification of the periphery by not only making a distinction between peripheral territories and peripheral actors (Glückler et al. Citation2022), but also adopting a constructivist ontology and dynamic understanding of periphery. In this regard, ‘(de)peripheralization’ (Kühn Citation2015, p. 368) describes a multidimensional process that leads to our ideas of what peripheries are (or are not) ‘through social relations and their spatial implications’ (Kühn Citation2015, p. 368). The dynamic processes through which peripheries actually emerge or transform become the focus. This lends greater agency to the strategies, innovations, and practices of actors that constitute peripheralization. Peripheralization retains fluidity and avoids deterministic accounts of peripheral areas emphasizing how they may transform over time and, for the purpose of this article, the role therein of social innovation.

Responsible and social innovation

Responsible innovation is understood as ‘taking care of the future through collective stewardship of science and innovation in the present’ (Stilgoe et al. Citation2013, 1570) and is defined as ‘a transparent, interactive process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other with a view to the (ethical) acceptability, sustainability and societal desirability of the innovation process and its marketable products’ (von Schomberg Citation2012, 54). It comprises progressive approaches to innovation that highlight collective action, transparency, and emphasis on process and responsiveness between societal actors with a stronger aim to reach social sustainability. In doing so, responsible innovation recognizes that much innovation has been directed towards inappropriate or contested ends (e.g. warfare) and seeks to stretch the purpose of innovation beyond merely economic, technological, and scientific values. However, most responsible innovation research is limited to technological innovation (Jakobsen et al. Citation2019; Owen & Pansera Citation2019). While having gained strong popularity in European science, technology, and innovation policy since early 2010s, the policy approach to responsible innovation appears as a one-size-fits-all framework based on principles of anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness (Coenen & Morgan Citation2020).

Similar to responsible innovation, social innovation has become an increasingly used and popular term in the spheres of policy, practice, and academia. Both responsible innovation and social innovation emphasize ethical and moral dimensions of innovation, acknowledging the responsiveness to societal challenges, and emphasizing process (Bolz & de Bruin Citation2019). However, whereas responsible innovation has its roots in science and technology studies (STS) and applied ethics (Koops Citation2015), social innovation has its roots in sociology, with a stronger focus on innovations as new forms of social relations (Westley Citation2008; Ayob et al. Citation2016). The rapid development of social innovation as a broad and multifaceted field of research and practice has been criticized for rather elusive definitions and being analytically fuzzy (Benneworth et al. Citation2015; Marques et al. Citation2018). However, Moulaert et al. (Citation2014) argue that such flexibility allows for versatility that loosens boundaries between research and action, and that emphasizes normative and moral awareness. Social innovation actions, strategies, practices, and processes arise whenever satisfactory solutions cannot be found in the institutionalized field of public or private action for either problems of poverty, exclusion, segregation, and deprivation, or opportunities for improving living conditions (Moulaert et al. Citation2014). Avelino et al. (Citation2019, 196) define transformative social innovation as ‘a process of change in social relations involving new ways of doing, thinking and organising that challenge alter and/or replace dominant institutions and structures’. Following Moulaert (Citation2009), I understand social innovation in this article as inherently territorial. It happens in a spatial context by the transformation of spatial relations, which are ‘context and spatially specific, spatially negotiated and spatially embedded’ (van Dyck & van den Broeck Citation2014, 133).

Taken together, the above-discussed novel conceptualizations of innovation emphasize alternative futures (responsible innovation) and alternative spatial imaginaries (social innovation). The emphasis on relations, collaboration, and participation in both responsible innovation and social innovation resonates explicitly with key challenges relating to innovation in peripheries, and it emphasizes the need to adopt a relational perspective on transformation of place in processes of deperipheralization/peripheralization. This warrants further extending the diversity of actors relevant for innovation processes (Solheim Citation2017) and invites us to take a closer look at the role of artists and creativity in the transformation of place. Following the pedagogical ideas of Paolo Freire (Citation1970), Bentz & O’Brien (Citation2019) suggest that art, art-based methods, and aesthetics serve as a powerful means to expand future imaginaries and develop new scenarios of transformative change.

Arts and creativity

Arts practices and processes can open new ways of seeing, thinking, and doing by inspiring people or communities, but that should not be mistaken for arts as a single solution to a larger problem or issue. The potential lies in the arts’ capacity to open up for reflection and bridge communication (Dewey Citation1934) of deep values and feelings, due to their inherently metaphoric qualities (Smiers Citation2005). It is part of the intangible processes and the making of beliefs and values that in turn can be discovered in creative processes and visualized in artistic material outcome. Imagination and creativity are integral parts of these processes. The arts can thereby help us think in novel ways about society through processes of recombination and social innovation (Mulgan Citation2021).

Creativity is defined as the ability to produce or use original and unusual ideas, and it is a multidimensional and complex phenomenon (Toivanen et al. Citation2013; Anderson et al. Citation2014). Creativity has been described as the most important economic resource of the 21st century (Florida Citation2002), with an ability to develop something novel and adapt to new situations, inseparable from unusual solutions and originality (Lemons Citation2005). Arts are having an increasingly relevant role in the promotion of creativity, but this is predominantly seen as an urban feature. Cohendet et al. (Citation2014) show that radical and transformative ideas, both in art and science, often come about in profoundly relational ways through interactions, frictions, or even clashes in localized, often urban, milieux. The same applies to innovation and creativity (Törnqvist Citation2004; Asheim et al. Citation2007). In focusing on the creative class, industries, or districts (Florida Citation2002), previous research has primarily focused on an instrumental use of artistic knowledge and practice through the notion of symbolic knowledge, defined as knowledge that is ‘applied in the creation of meaning and desire, as well as in the aesthetic attributes of products, producing designs, images, and symbols, and in the economic use of such forms of cultural artifacts’ (Asheim & Hansen Citation2009, 430). This conceptualization stresses context specificity and heterogeneity of meaning across social groups in innovation processes. However, from a territorial perspective, the emphasis on creative class and industries has been criticized for overlooking the risk of gentrification, and deepening socio-spatial exclusion and inequality (Ley Citation2003; Mathews Citation2010).

It is therefore relevant to move beyond a mainstream, economic use of artistic knowledge in innovation processes and to consider how artists engage with social innovation and venture beyond the boundaries of arts, culture, creative industries, and urban milieux. This, in turn, raises questions about what kinds of creativity matter. In this regard, Shearmur (Citation2012, 15), in adopting a relational perspective on innovation and creativity, argues that it does not make sense to attribute innovation to any particular physical location:

each type of milieu, whether geographic or social, may have a role to play in generating, developing, and promoting innovation. This means that rural and urban places, small towns and large cities, the wealthy and the poor, those labelled ‘creative’ and those assumed not to be, may all participate, in their own way, in the innovative process.

Hautala & Jauhiainen (Citation2018) show how artists in general are drawn to locations with art clusters and urban centres where the milieu and its organizations support ongoing creativity (Drake Citation2003). However, they also found that artists distanced themselves from those centres to challenge and redefine ‘the mainstream’ and where processes of ‘marginalization’ and ‘peripheralization’ formed creative projects on the fringes of domains where issues and problems could open up opportunities for creative responses (Hautala & Ibert Citation2018). Similarly, this article breaks with the urban bias in spatial approaches to creativity by focusing on artist-initiated and artist-led processes of social innovation and engagement processes in a peripheral context. Accordingly, I consider creativity in a relational context between people situated with different experiences and in networks across space. Diversity is seen as an asset for creativity, as well as for social innovation (André et al. Citation2014; Trembley & Pilati Citation2014). This suggests that artists, together with intellectuals and members of civil society, can create communities of practice to promote deep cultural changes (Leichenko & O’Brien Citation2019). Thus, arts and cultural networks and mobile artistic practices can potentially bridge across locations and between people, opening up for interconnectedness and positioning places, including peripheral areas, as continuously emerging and ‘in production’ (Massey Citation2005).

Introduction to the case studies

The two case studies focus on bottom-up artist-led initiatives that aim to take responsibility for regional development and transformation of place through social innovation. Both Bromölla and Rjukan are old industrial towns that have witnessed processes of peripheralization in recent decades. The towns emerged from industry development connected to natural resources in their respective local area in the early 20th century and later developed into regional company towns. Currently, both towns are challenged due to an aging population, depopulation, and economic decline, while the municipalities in which they are located, respectively Bromölla Municipality and Tinn Municipality, are working towards reinvention through the hospitality industry, with nature-based and/or cultural tourism. The artists’ initiatives have introduced creative practices and artistic methods to envision and enact sustainable regional futures. First, the case studies are described and analysed with regard to the kinds of social innovations that have been enacted by the artists initiatives. Second, the case studies are described and analysed with regard to how these social innovations have afforded processes of deperipheralization and transformation of place.

Methods

The analysis is based on two qualitative case studies in which explorative research methods and hybrid strategies based on multiple sources were used. According to Yin (Citation2018), case studies provide a suitable research design for addressing ‘how’ research questions, for instances when the researcher has little control over events, and when the focus is on a contemporary phenomenon within real-life contexts. The case study affords in-depth, contextual inquiry (Yin Citation2018), and sometimes longitudinal inquiry of one or a range of similar events (Flyvbjerg Citation2006). My research comprised 15 semi-structured interviews held between June and November 2021, of which 9 were combined with the method of walking-based interviews (Pink et al. Citation2010), all with stakeholders related to the two chosen cases. The walking interviews served to complement the research material, as they more closely related to the spatial context and creative processes in place, and hence opened up for an in-depth contextual study. Additionally, photo-documentation of the surrounding environment was done as part of the walking-based interviews. The visual documentation of the ‘walk and talk’ context can be read as texts (Pink et al. Citation2010) and brings out a tangibility based on the relational aspects with space and material. At the time when the interviews were held, several of the interviewees were focusing on artistic creative practices that were closely linked to material and place. By being physically present, relevant reflections on creativity and place can potentially emerge in ways that can be more challenging outside such contexts. Key informants were selected in order to provide ‘information-rich cases’ (Kreuger & Casey Citation2009), and they included artists, volunteers, project employees, and local and regional civil servants working on cultural development. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and ‘initial coded’ (Charmaz et al. Citation2018) manually, then categorized and analysed according to main questions. The interviews were mainly conducted in Norwegian and Swedish, but some of the interviewees chose English as their preferred language for the interviews.Footnote1 Additionally, participant observations of project participants, visitors (citizens), and artists were undertaken, and short were held interviews with citizens, all on-site. Summative notes were taken in conjunction with the fieldwork. The data production complied with Norwegian Centre for Research Data’s ethics of informed consent and safe storage of data. Local and regional cultural strategy documents and other background material relevant to the two cases were selected, read, and analysed during the research process.

Ifö Center

The first case study, Ifö Center, is situated in the town of Bromölla, which is in the northeast of Skåne County, Sweden. In 2021, Bromölla has c.8000 inhabitants (Bromölla kommun Citation2022). Historically, the town is known for its strong manufacturing industry, with sanitary porcelain products such as toilets and sinks. Bromölla is built around a centrally located industrial park (Iföverken), which affords it a strong identity as a single-industry town. Designers and artists were connected to the development of sanitary hardware products during the 1930s to 1970s. This led to the collaboration between Iföverken and Bromölla Municipality, and the production of several public ceramic art works during that period, which has contributed to the town’s visual identity, together with the centrally located industry park. The manufacturing industry is still present, but today Bromölla is mainly considered a commuter town. Bromölla is challenged by an aging population and several years of budget deficit, with cuts in culture and leisure activities, among other cuts.

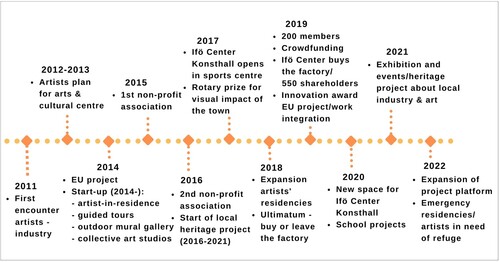

Ifö Center is an arts and cultural centre located in a former insulator factory in the gated industrial park. It was initiated by and is led by two artists – Teresa Holmberg and Jonathan Haner – in collaboration with its members, volunteers, visiting artists, and individuals taking part in different work integration programmes and internships. Ifö Center is a not-for-profit association organized as an umbrella for a second not-for-profit organization, as well as for a shareholder company with a special dividend limitation. The property is owned by Ifö Center, its members, and shareholders: it contains 43,000 m2 of premises hosting different functions (Ifö Center Citationn.d.,a). For artists and artisans specifically, there are art studios and collective art production studios providing for the use of a wide range of mediums and techniques. In addition, there are spaces for large-scale productions. From a public engagement point of view, there are both indoor exhibition spaces accessible from outside the gated park, and a continuously growing outdoor gallery with murals painted on the factory buildings. Ifö Center offers artist-in-residence programmes, different arts and craft courses for the general public and artists, a language café for the local community, guided tours, and engagement programmes for schools. Additionally, Ifö Center has storage space available for rent, hosts other cultural not-for-profit associations, and has a guest house for visiting artists. Key points in Ifö Center’s development are shown in .

Ifö Center as social innovation: changing social relations

The purpose of Ifö Center is to provide artists with a variety of collective art production studios, engage with local communities, as well as external partners and tourists, and care for Bromölla’s industrial heritage and identity by cross-fertilizing it with arts initiatives and creative engagement projects. Social sustainability is at heart of the initiative. As a regional arts and cultural centre, Ifö Center has adopted a wider societal scope and responsibility through social innovation: it explicitly seeks to promote the local industrial and cultural heritage while adding artistic collaborative processes and activating place through collective action and the inclusion of different stakeholders in the process, such as artists, residents, visitors, factory workers, and policymakers.

Ifö Center was started when two artists took the initiative to set up an art practice in the active industry setting of Bromölla’s industrial park. Initial encounters between artists and some of the factory workers were not entirely without frictions and at times were unwelcoming, whereas others offered a helping hand. In that process the artists learned about the factory workers’ precarious work situations. The collaboration eventually resulted in a public artwork. Gradually, the artists expanded the premises from a small office space to take over 4500 m2 of unused factory space (Ifö Center Citationn.d.,b). Ultimately, Ifö Center bought the entire factory of 43,000 m2 (Ifö Center Citationn.d.,a), guided by a vision to create an inclusive cultural centre in an active industry setting, with values of collective creativity, ownership, and responsibility. New relations between artists, citizens, industry stakeholders, and the public sector were forged and negotiated in that process:

This was the first place I came to when I arrived in Sweden. First place to live, to work, at Ifö Center […] we practice Swedish with each other […] and you can meet so many people in one day. (Crew member of daily operations)

A significant moment in the creation process was when Ifö Center mobilized a range of stakeholders to buy the complete factory. In 2018 it was announced that Ifö Ceramics in Bromölla was to be closed down, and Ifö Center was given the option to either leave the building or buy the entire factory building; it chose the latter. While realizing that it needed a new approach to achieve the rather utopian goal, it was important for Ifö Center to keep the idea of collective values. It decided to set up a crowdfunding campaign and establish a shareholder company with a special dividend limitation in recognition of the collective engagement and shared ownership of Ifö Center. The company’s mission is to work as a catalyst and incubator for innovation, entrepreneurship, social inclusion, arts and culture, and tourism, and to promote sustainable development. Its collective engagement and shared ownership have been empowering for many members and stakeholders: ‘The most amazing thing is when we could buy this factory. […] Yes, I think it is a bit different, it’s both big and different, and buying a factory is not something you do every day’ (Volunteer and member).

The artists who initiated Ifö Center transcended from being short-term actors carrying out a temporary art project in an industry setting to becoming long-term agents of change by taking over a large part of a factory and then gradually extending the range of activities and responsibilities. Upscaling the initiative, including different stakeholders in the process, embedding it within a regional context, and connecting with international networks of cultural centres initiated by citizens and artists, such as Trans Europe Halles, have given Ifö Center a reputation and legitimacy beyond Bromölla. The local government was dedicated to support Ifö Center in its early phase of establishment, as it recognized its potential for bringing in tourism, strengthening the town as an attractive place to live, and promoting Bromölla in a regional context. However, as Ifö Center grew bigger and stronger, support from local government decreased as a result of changes in political leadership and budget cuts in culture. As a response, regional funding increased and long-term support was established, which acknowledged the value of Ifö Center for inclusive cultural production in a part of the region that until then had been a geographical blind spot for such activities. The breadth and variety of collective workshops gathered in one site is considered unique in Skåne County and has created opportunities for a diverse set of artists and artisans to interact and meet:

Primarily we feel that we want to build a place for creative people, and at the same time we are aware that if you gather many creative people in one place, it will also be interesting for other people, and I think it’s totally OK, but it is important to keep some kind of balance, so that it does not come at the expense of the artists, so it does not become ‘animals at the zoo’, but to keep a good balance. (Artist and initiator)

Transformation of place

Historically, Bromölla has been built around the industrial park and traces of this can be seen in the structure of the city, though its buildings, ceramic art, and names of objects and organizations. The closure of Ifö Ceramic factory had a direct impact on the local community, creating an insecure situation for many families. The economic decline was visible due to a lack of building maintenance of the factory and industrial park. However, a new narrative emerged when Ifö Center and ‘culture’ were able to take over the factory together with citizens. Ifö Center currently contributes to transformative change in Bromölla in three important ways: (1) creative impulses through artist mobility, (2) changing Bromölla’s visual identity, and (3) engaging and empowering the local community through voluntary work and work programmes.

Creative impulses through artist mobility

Ifö Center activates care for place by engaging artists and other stakeholders, in conjunction with artistic processes and material. While the initiative is run by two artists in collaboration with different local stakeholders, there is a flow of visiting artists through artist-in-residence programmes. This gives mobile artists an opportunity to stay in Bromölla temporarily, to work on new productions, and to engage with members of the local community and with other artists working at Ifö Center simultaneously. Also, as a member of the Swedish Artist Residency Network (SWAN), Ifö Center takes part in ‘emergency residencies’ through the international organization Artists at Risk, by inviting artists in need of refuge. In addition to citizens’ interactions with artworks accessible to the passer-by in an everyday setting, there is also opportunity to participate directly in artistic processes. Thus, Ifö Center stimulates curiosity, new ways of thinking, and promotes imagination and debate among the local community.

Change of visual identity

Places are in production. This creates an opportunity for artists to carry out their practices. Artists draw on different narratives in society, which are interpreted in creative practice and translated into artistic processes and material form. The murals in the outdoor gallery at Ifö Center are a poignant example of the transformation of place through artistic practice (): ‘What is most noticeable to the outside world is the outdoor gallery and the fact that you get into a completely different world, as well as this international perspective. Yes, that you connect Bromölla with a different context as well’ (Municipal officer). The gallery symbolizes the intertwined narrative between the local industrial heritage and ‘new voices’ representing visiting artists’ interpretation of and artistic interaction with Bromölla. Today, most Bromölla citizens know about the artists’ initiative one way or another, and often refer to the murals in the outdoor gallery – it defines place and makes it authentic and special. In turn, artists spread their place-based work through visual documentation and stories that are communicated and disseminated in the media, and more specifically within the arts world. In addition, the outdoor gallery is strategically part of the local tourist promotion and has become a popular tourist attraction.

Engaging and empowering local community through voluntary and work programmes

Albeit on a small scale, Ifö Center has created opportunities for different members from the local community to interact. New relations are not only forged both between people working with the daily operations at Ifö Center, employees working at the industrial park, and visiting artists, but also between Ifö Center front of house staff and visitors to the exhibitions. Social responsibility is central to the structure of the organization. The past history of each person working at Ifö Center is only brought forward if the person chooses to talk about it. Rather, the focus lies on the present of what can and will be created together, with the idea that each and every person can contribute something. Ownership of creativity is promoted by creating opportunities for holding classes and creative workshops, which are held not only by professional artists, but also by the persons working with Ifö Center’s daily operations.

Rjukan Solarpunk Academy

Rjukan Solarpunk Academy (RSA) is in Rjukan, a mountain town in Tinn Municipality in the county of Vestfold og Telemark in Norway, to the southeast of the country’s largest national park, Hardangervidda. Already in the 19th century Rjukan’s waterfalls were depicted by painters and the images were spread beyond Rjukan, thus contributing to Norway’s identity. Rjukan emerged as a one-company town in the early 20th century, when it expanded from a small rural village into a modern industrial town in a short period of time. In 1911, the then largest hydropower plant in the world was established in Rjukan and this is also part of the early history of Norsk Hydro, one of Norway’s largest energy companies. Over the course of 120 years, Rjukan transformed from a small farming community to a modern industrial town. In 2021, Rjukan has a population of c.3500 inhabitants (Tinn kommune Citation2021). The town is challenged by depopulation and an increasingly aging population, but there are also opportunities, such as in the tourism industry. Since 2015, Rjukan has been classified as world heritage by UNESCO for its industrial heritage.

The RSA was initiated and led by two artists, Margrethe Kolstad Brekke and Martin Andersen. It comprises a school of art, an artists-in-residence programme, space for exhibitions and studios, the site-specific public artwork Solspeil, which is a sun mirror by Martin Andersen, and a café that experiments with different concepts relating to sustainability. The RSA is a non-profit association combined with the café. The initiative is still in its early experimentation phase with regards to its organizational structure. Underpinning the current collaborative initiative, the artists’ creative practices take sustainability thinking as a leitmotif. Key points in Rjukan Solarpunk Academy’s development are shown in .

Rjukan Solarpunk Academy as social innovation: changing social relations

The core purpose of the RSA is to address climate change and open up for questions concerning sustainability through contemporary art, artistic processes, and cross-disciplinary collaborations while acting in a local social arena. The initiative has taken inspiration from the Solarpunk movementFootnote2 by specifically emphasizing imagined positive futures. The creative practices of the RSA seek to redeem the ability of individuals and society to imagine alternative futures and to create new paths to social imagination that consider the ‘wicked problems’ facing our societies. Rather than focusing on dark dystopian narratives, the RSA is dedicated to addressing the transition towards a ‘green’ future through positive future imaginaries. The academy is envisioned to be established in a zero-footprint sustainable way:

The art has contributed a lot to explain the seriousness of this situation [the environmental and climate crisis], but now it is about relating to the wicked problems and actually making changes. […] In this place we can experiment in a way that is not possible where the square metre prices are higher. (Artist (a) and initiator)

How can we manage to attract people, and stimulate development if we cut down on culture and cultural events? To get people here, work and jobs are not enough. To make this place attractive, they need a place to live and things to do during their leisure time. […] to live in a place where it’s all dead after work hours is not attractive. Then you won’t get people to move to Rjukan. (Director of Culture, Tinn Municipality)

Collaborations with academic researchers, other grassroots organizations, and artists are of major importance when addressing climate change issues. The RSA’s artists-in-residence programme has, for example, opened up for new ways of thinking and doing with regard to food and sustainability locally, by inviting the initiator of People’s Kitchen Tromsø (Tromsø Folkekjøkken), artist Liv Bangsund. The artist works with surplus food in different ways. During her stay, Liv Bangsund experimented with food, with the ambition to create new textile artworks. In addition, she artist engaged in workshops on surplus food, together with a group of upper secondary school students and an open event for the public. During the workshops, the participants collectively made shared meals with surplus food. Liv Bangsund departs from the idea that everyone is an artist, inspired by the artist Joseph Beuys (d. 1986), and a hands-on collective experience in which a dugnad (voluntary work) has high value:

I think it is unnecessary to dig in refuse bins or big containers when I can ask politely whether I can have it [surplus food from the shops]. At the grocery shops they are very preoccupied by all that’s thrown away and they don’t like it. […] It is very hands-on with the People’s Kitchen. When you touch the food that was supposed to be thrown away, something happens in the participant’s brain. The food becomes visual, the food that was supposed to be thrown away. Instead, we make dinner and enjoy ourselves. […] Maybe they [participants] get a thought today and maybe they will continue to think more about food a long time ahead. (Artist-in-residence)

Transformation of place

Rjukan Solarpunk Academy has transformative ambitions, with the vision of turning Rjukan into a leading example of climate transition. It has done and will do so by facilitating collaborations to connect research, creative processes, and different stakeholders. Notably, the artwork Solspeil is a manifestation of transformation of place, by (1) activating public space through participative processes and sustainable thinking, and (2) generating a new narrative about Rjukan.

Collaborations connecting research, creative processes, and different stakeholders

By engaging with the unfolding climate crisis, the RSA will challenge Rjukan to shift its temporal gaze from the past to the future. The initiative is built on the combined knowledge and experience of the two artists who initiated the RSA. One of those artists brings in ideas of ways of working through cross-disciplinary constellations and collaborating with academia with regard to climate change and transitions, and she translates relevant research into creative processes and practice. The other artist has adopted a direct place-based engagement, focusing on Rjukan and the relations within the place:

We try, in a way to, I think at least for the whole concept, the entire house, and this place, we wish to contribute more, to give more than we take. So, it will become positive and creative. That is very important. (Artist (b) and RSA initiator)

Activating public space through participatory processes and sustainable thinking

The RSA artist Martin Andersen created the public artwork Solspeil (literal translation: ‘Sun Mirror’) in collaboration with different stakeholders and the local municipality (). The site-specific artwork is a computer-driven heliostat positioned on a mountain top (combining mirrors, solar panels, and wind energy), which captures sun rays and directs them onto the town square in Rjukan. The town is located in a deep valley between mountains and direct sunlight is absent for six months of the year. Some citizens have had to leave the town in order to experience direct sunlight during the winter months. The artist (Martin Andersen) has activated place through participatory processes and interaction with the artwork. The work, which conceptually is centred on relational aesthetics, focuses on social context and collective values by including people, challenging dominant powers, collecting stories, and integrating a place-based and everyday life perspective. The square has increasingly become a social place when Solspeil is activated – from the passer-by who stays for a few minutes of sunlight, to organized events for people wanting to skate on ice. The owner of the artwork, Tinn Municipality, has made it into a strategic marketing tool and tourist attraction:

There was actually a lot of resistance against Solspeil before it was built. It was considered a waste of money. Why should we use five million crowns [NOK] for this mirror when we need money for the elderly, and school and children, and all that? A signature campaign was made and all kinds of stuff […] Solspeil has really put Rjukan on the world map lately. We have had a massive influx of tourists that maybe isn’t entirely caused by Solspeil, but it was a big conscious reason why we had more tourists coming here. […] Solspeil is not working all months of the year, and then debates and writings can start ‘why doesn’t Solspeil work?’ Yes, it is very popular amongst the local community, because it shines down on the square, and lights up around 30 metres. In winter we make an ice-skating rink there and when the sun shines down on the square it is a magnet. (Director of Culture, Tinn Municipality)

New narrative transforming place

The artwork Solspeil was inspired by human relations and their social context, and Rjukan is deeply connected to the narrative about the sun. Solspeil bridges place-based histories by activating place as a contemporary phenomenon with dreams and ambitions for the future. Historically, Rjukan has been shaped by several innovations, such as the world’s largest power station with the hydro-electric power plants, which marks the turn from coal-fired power to hydro-electric energy for industrial use. This was the foundation of Rjukan as a modern industrial town. Since 2015, Rjukan has been acknowledged as a world industrial heritage site with a focus on the above-mentioned historical innovations and achievements. This stands in contrast to the everyday life of Rjukan as a place also challenged by depopulation and municipal budget cuts. The focus of the site-specific artwork is based on the everyday wishes and dreams of Rjukan citizens in the past and the present. In combination with new technological solutions bridging the artwork to Rjukan’s industrial heritage and technological progress, Solspeil is bringing in new interest groups and networks to Rjukan. As a consequence, the narrative of Rjukan has changed from ‘Rjukan that lacks sun’ to ‘Rjukan and the sun’, which serves to highlight the symbolic nature of art and the power of meaning-making. The town square was renamed Soltorg (the Sun Square). Articles, debates, news clips, and films have communicated the change in the narrative and thus contributed to the meaning making of place.

Conclusions

In this article I have explored alternative ways by which innovation contributes to sustainable regional development in peripheral areas. In focusing on artist initiatives and artistic practices in the two case studies, I have considered forms of social innovation that deviate from dominant narratives of peripheral regions as innovation backwaters that are lacking critical mass in cultural and creative capabilities for regional competitiveness. These artist initiatives and innovations did not primarily address economic development goals, nor were they directly aimed at strengthening creative industry, even though tourism development has benefitted indirectly from respective initiatives. Rather, the artists have engaged with development objectives that can be considered intrinsically significant for place-based sustainability, such as education, well-being, sense of community, and care for environment, in contrast to development outcomes that are instrumentally significant, such as economic growth, business creation, and income (Morgan Citation2004). Examples of the ways in which the artists, organized in relation to experimental arts and cultural centres, have contributed to local/regional development are by activating public space through participatory processes and sustainable practices, rendering creative impulses through artist mobility, changing visual identity of place, creating new place narratives, engaging and empowering local community through voluntary and work programmes, and collaborating across research, arts, and other fields.

The artist initiatives have contributed to countering processes of peripheralization in the respective localities along material, organizational, and discursive dimensions. In material terms, they produce local, often site-specific artworks that render cultural, social, and economic value to a place by attracting attention and visitors. In organizational terms, the initiatives facilitate arenas and platforms for community-building by fostering connectivity and networking, both locally and globally. In discursive terms, they contribute to shaping a new narrative of place. Thus, through social innovation, artist initiatives can empower local citizens and other actors to experiment collectively with unconventional ideas related to social and environmental sustainability and to take responsibility for place. In terms of peripheralization, it should be noted that the artists leading the initiatives have not only consciously created their practices outside the urban core, but have also taken those practices to the edge of their own domains. That is, through social innovation and in taking responsibility for place, the artist initiatives have partly redefined artistic practices and identities as artists.

This study of artist initiatives and social innovation to redress peripheralization has shown that it is critical to question ‘responsibility for whom or what’ when innovating responsibly. The studied social innovations have enacted responsibility for development outcomes that are intrinsically significant through an ethos of care in both a temporal sense (care for future) and a spatial sense (care for place). Such an ethos of care informs both objectives and means of innovation. Care for place is enacted by mobilizing both individual and social creativity through inclusive practices and collective action. In this respect, inclusion and community engagement appear as central features to the way in which the artist-led social innovations have taken responsibility for place. Thus, my analysis has drawn attention to the profoundly relational qualities of responsible innovation processes. This, in turn, relates back to one of the defining characteristics of social innovation, namely its objective to change social relations between actors.

Importantly, my analysis has revealed that artists initiatives experimenting with social innovation in peripheral areas emphasize social creativity in addition to individual, artistic creativity (on rural creativity, see Woods Citationn.d.). Instead of mimicking success strategies of innovation and creativity grounded in urban cores, the two studied cases show that peripheral areas can be sources of creativity in their own right. However, this requires a broadened understanding of creativity that combines everyday creative contexts (e.g. the People’s Kitchen in Rjukan) and the artistic and/or monumental (e.g. factory murals in Bromölla). A broadened perspective on creativity has a critical role to play in reimagining and taking responsibility for peripheral areas.

Thus, creative practices by artists can play a hitherto neglected role in regional development in peripheral areas. They can help in fostering shared ownership and a broadened sense of responsibility for both future and place by bringing people together, by collectively reflecting on social, economic, and environmental change, and by sharing ideas for development that matters to people. Nonetheless, some words of caution regarding the limitations of this study are warranted. To enact social innovation, artists have to adopt a considerable degree of entrepreneurship to diversify their portfolio of activities and offerings. Partly this is welcomed and at times encouraged by policy when new ways of organizing and funding are explored. At the same time, this may risk instrumentalizing the value of arts by subordinating them to social and economic imperatives at the expensive of cultural and artistic expression. Further research is needed, not only to ascertain the long-term impact of artist initiatives but also to shed light on its potential dark sides and unintended consequences.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (428.6 KB)Acknowledgments

I thank Ifö Center in Bromölla, Rjukan Solarpunk Academy, and the interviewees for their invaluable time and for sharing their insights. The article benefited from collaborations through the project Just Mobility Transitions Network, coordinated by Associate Professor Siddharth Sareen at University of Stavanger. Many thanks are owed to Professor Flor Avelino and Professor Tobba Therkildsen Sudmann, as well as Professor Lars Coenen for helpful feedback on early drafts of the article. I am also grateful for the constructive comments from four anonymous reviewers and the guest editors of the special issue.

Notes

1 All translations from Norwegian and Swedish into English were done by the author of this article (Karin Coenen).

2 Solarpunk is a movement in speculative fiction, art, fashion, and activism that seeks to answer and embody the question of what a sustainable civiliztion looks like and can it be attained.

3 The initiative is part of the research programme ‘Empowered Futures: A Global Research School Navigating the Social and Environmental Controversies of Low-Carbon Energy Transitions’ funded by the Research Council of Norway.

References

- Anderson, N., Potočnik, K. & Zhou, J. 2014. Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management 40(5), 1297–1333.

- André, I., Abreu, A. & Carmo. A. 2014. Social innovation through the arts in rural areas: The case of Montemor-o-Novo. Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A. & Hamdouch, A. (eds.) The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research, 242–255. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Asheim, B. & Hansen, H. K. 2009. Knowledge bases, talents, and contexts: On the usefulness of the creative class approach in Sweden. Economic Geography 85(4), 425–442.

- Asheim, B., Coenen, L. & Vang, J. 2007. Face-to-face, buzz, and knowledge bases: Sociospatial implications for learning, innovation, and innovation policy. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 25(5), 655–670.

- Avelino, F., Wittmayer, J.M., Pel, B., Weaver, P., Dumitru, A., Haxeltine, A., Kemp, R., Jørgensen M.S., Bauler, T., Ruijsink, S. & O’Riordan, T. 2019. Transformative social innovation and (dis)empowerment. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 145, 195–206.

- Ayob, N., Teasdale, S. & Fagan, K. 2016. How social innovation ‘came to be’: Tracing the evolution of a contested concept. Journal of Social Policy 45(4), 635–653.

- Bathelt, H. & Glückler, J. 2005. Resources in economic geography: From substantive concepts towards a relational perspective. Environment and Planning A 37(9), 1545–1563.

- Benneworth P., Amanatidou, E., Edwards Schachter, M. & Gulbrandsen, M. 2015. Social innovation futures: Beyond policy panacea and conceptual ambiguity. Centre for Technology, Innovation and Culture, University of Oslo, Working Papers on Innovation Studies, No. 20150127. http://ideas.repec.org/s/tik/inowpp.html (accessed 6 December 2022).

- Bentz, J. & O’Brien, K. 2019. Art for change: Transformative learning and youth empowerment in a changing climate. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene 7: Article 52.

- Bolz, K. & de Bruin, A. 2019. Responsible innovation and social innovation: Towards an integrative research framework. International Journal of Social Economics 46(6), 742–744.

- Bromölla kommun. 2022. Befolkning, arbet, statistik. https://www.bromolla.se/kommun-och-politik/kommunfakta/befolkning-arbete-statistik/ (accessed 10 January 2023).

- Charmaz, K., Thornberg, R. & Keane, E. 2018. Evolving grounded theory and social justice inquiry. Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y. (eds.) The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 411–433. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Coenen, L. & Morgan, K. 2020. Evolving geographies of innovation: Existing paradigms, critiques and possible alternatives. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 74(1), 13–24.

- Cohendet, P., Grandadam, D., Simon, L. & Capdevila, I. 2014. Epistemic communities, localization and the dynamics of knowledge creation. Journal of Economic Geography 14(5), 929–954.

- Dewey, J. 1934. Art as an Experience. New York: Berkley Publishing Group.

- Drake, G. 2003. ‘This place gives me space’: Place and creativity in the creative industries. Geoforum 34(4), 511–524.

- Eder, J. 2019. Innovation in the periphery: A critical survey and research agenda. International Regional Science Review 42(2), 119–146.

- Fitjar, R.D. & Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2011. Innovating in the periphery: Firms, values and innovation in Southwest Norway. European Planning Studies 19(4), 555–574.

- Fitjar, R. & Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2013. Firm collaboration and modes of innovation in Norway. Research Policy 42(1), 128–138.

- Fitjar, R.D. & Jøsendal, K. 2016. Hooked up to the international artistic community: External linkages, absorptive capacity and exporting by small creative firms. Creative Industries Journal 9(1), 29–46.

- Fløysand, A. & Jakobsen, S.-E. 2011. The complexity of innovation: A relational turn. Progress in Human Geography 35(3), 328–344.

- Florida, R. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: Basic Books.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry 12(2), 219–245.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Melbourne: Penguin Random House.

- Fritsch, M. & Wyrwich, M. 2021. Is innovation (increasingly) concentrated in large cities? An international comparison. Research Policy 50(6): Article 104237.

- Gluckler, J. 2014. How controversial innovation succeeds in the periphery? A network perspective of BASF Argentina. Journal of Economic Geography 14(5), 903–927.

- Gluckler, J., Shearmur, R. & Martinus, K. 2022. From Liability to Opportunity: Reconceptualizing the Role of Periphery in Innovation. Working paper. SPACES online. http://www.spaces-online.com/index_2022.php (accessed 6 December 2022).

- Grabher, G. 2018. Marginality as strategy: Leveraging peripherality for creativity. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 50(8), 1785–1794.

- Hautala, J. 2015. Interaction in the artistic knowledge creation process: The case of artists in Finnish Lapland. Geoforum 65, 351–362.

- Hautala, J. & Ibert, O. 2018. Creativity in arts and sciences: Collective processes from a spatial perspective. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 50(8), 1688–1696.

- Hautala, J. & Jauhiainen, J. 2018. Creativity-related mobilities of peripheral artists and scientists. GeoJournal 84, 381–394.

- Ifö Center. n.d.,a. Ifö Center utlyser AIR2 - sök ett fritt arbetsstipendium! https://www.ifocenter.com/ (accessed 10 January 2023).

- Ifö Center. n.d.,b. Ifö Center är ett konstnärsdrivet kulturhus beläget på anrika Iföverken vid Ivösjön i Bromölla. https://www.ifocenter.com/ifouml-center-och-ifoumlverken.html (accessed 11 January 2023).

- Jakobsen, S., Fløysand, A. & Overton, J. 2019. Expanding the field of Responsible Research and Innovaton (RRI) – from responsible research to responsible innovation. European Planning Studies 27(12), 2329–2343.

- Koops, B. 2015. The concepts, approaches, and applications of responsible innovation: An introduction. Koops, B.-J., Oosterlaken, I., Romijn, H., Swierstra, T. & van den Hoven, J. (eds.) Responsible Innovation 2: Concepts, Approaches, and Applications, 1–15. Cham: Springer International.

- Kreuger, R. & Casey, M. 2009. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Kühn, M. 2015. Peripheralization: Theoretical concepts explaining socio-spatial inequalities. European Planning Studies 23(2), 367–378.

- Leichenko, R. & O’Brien, K. 2019. Climate and Society: Transforming the Future. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Lemons, G. 2005. When the horse drinks: Enhancing everyday creativity using elements of improvisation. Creativity Research Journal 17(1), 25–36.

- Ley, D. 2003. Artists, aestheticisation and the field of gentrification. Urban Studies 40(12), 2527–2544.

- Makkonen, T. & Kahila, P. 2021. Vitality policy as a tool for rural development in peripheral Finland. Growth and Change 52(2), 706–726.

- Marques, P., Morgan, K. & Richardson, R. 2018. Social innovation in question: The theoretical and practical implications of a contested concept. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 36(3), 496–512.

- Massey, D. 2005. For Space. London: SAGE.

- Mathews, V. 2010. Aestheticizing space: Art, gentrification and the city. Geography Compass 4(6), 660–675.

- Mazzucato, M., Kattel, R. & Ryan-Collins, J. 2020. Challenge-driven innovation policy: Towards a new policy toolkit. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 20(2), 42–437.

- Morgan, K. 2004. Sustainable regions: Governance, innovation and scale. European Planning Studies 12(6), 871–889.

- Morgan, K. & Henderson, D. In press. Everyday innovation in the periphery: The foundational economy in a less developed region. Teles, F., Ramos, F. & Rodrigues, A. (eds.) Territorial Innovation in Less Developed Regions: Communities, Technologies and Impact. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Moulaert, F. 2009. Social innovation: Institutionally embedded, territorially (re)produced. MacCallum, D., Vicari, H.S., Hillier, J. & Moulaert, F. (eds.) Social Innovation and Territorial Development, 11–23. London: Routledge.

- Mouleart, F. & Sekia, F. 2003. Territorial innovation models: A critical survey. Regional Studies 37(3), 289–302.

- Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A. & Hamdouch, A. (eds.) 2014. The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Mulgan, G. 2021. Social Innovation Foresight #1 on Social Imagination. https://socialinnovation.se/event/social-innovation-foresight-social-imagination/ (accessed 6 December 2022).

- Owen, R. & Pansera, M. 2019. Responsible innovation and responsible research and innovation. Simon, D., Kuhlmann, S., Stamm, J. & Canzler, W. (eds.) Handbook on Science and Public Policy, 26–48. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Pink, S., Hubbard, P., O’Neill, M. & Radley, A. 2010. Walking across disciplines: From ethnography to arts practice. Visual Studies 25(1), 1–7.

- Pugh, R. & Dubois, A. 2021. Peripheries within economic geography: Four ‘problems’ and the road ahead of us. Journal of Rural Studies 87(7), 267–275.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2018. The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11(1), 189–209.

- Schot, J. & Steinmueller, W.E. 2018. Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Research Policy 47(9), 1554–1567.

- Scott, A.J. 2006. Creative cities: Conceptual issues and policy questions. Journal of Urban Affairs 28(1), 1–17.

- Scott, A.J. 2010. Cultural economy and the creative field of the city. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, 92(2), 115–130.

- Shearmur, R. 2012. Not being there: Why local innovation is not (always) related to local factors. Westeren, K.I. (ed.) Foundations of the Knowledge Economy, 117–138. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Shearmur, R. 2017. Urban bias in innovation studies. Bathelt, H., Cohendet, P., Henn, S. & Simon, L. (eds.) The Elgar Companion to Innovation and Knowledge Creation, 440–456. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Shearmur, R., Carrincazeaux, C. & Doloreux, D. 2016. The geographies of innovations: Beyond one-size-fits-all. Shearmur, R., Carrincazeaux, C. & Doloreux, D. (eds) Handbook on the Geographies of Innovation, 1–16. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Smiers, J. 2005. Arts Under Pressure, Promoting Cultural Diversity in the Age of Globalization. London: Zed Books.

- Sörlin, S. 1999. The articulation of territory: Landscape and the constitution of regional and national identity. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift 53(2-3), 103–111.

- Solheim, M.C.W. 2017. Innovation, Space, and Diversity. PhD Thesis. Stavanger: University of Stavanger.

- Stenbacka, S. & Heldt Cassel, S. 2020. Introduktion – periferier och periferialisering. Heldt Cassel, S. & Stenbacka, S. (eds.) Periferi som process, 7–24. Årsboken Ymer. Ödeshög: Svenska sällskapet för Antropologi och Geografi.

- Stilgoe, J., Owen, R. & Macnaghten 2013. Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Research Policy 42(9), 1568–1580.

- Tinn kommune. 2021. Om Tinn kommune. https://www.tinn.kommune.no/artikkel/om-kommunen(accessed 11 January 2023).

- Törnqvist, G. 2004. Creativity in time and space. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 86(4), 227–243.

- Toivanen, T., Halkilahti, L. & Ruismäki, H. 2013. Creative pedagogy – supporting children’s creativity through drama. European Journal of Social & Behavioural Sciences 7(4), 1168–1179.

- Trembley, D.-G. & Pilati, T. 2014. Social innovation through arts and creativity. Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A. & Hamdouch, A. (eds.) The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research, 67–79. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Uyarra, E., Ribeiro, B. & Dale-Clough, L. 2019. Exploring the normative turn in regional innovation policy: Responsibility and the quest for public value. European Planning Studies 27(12), 2359–2375.

- van Dyck, B. & van den Broeck, P. 2014. Social innovation: A territorial process. Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A. & Hamdouch, A. (eds.) The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research, 131–141. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- von Schomberg, R. 2012. Prospects for technology assessment in a framework of responsible research and innovation. Dusseldorp, M. & Beecroft, R. (eds.) Technikfolgen abschätzen lehren, 39–61. Wiesbaden: VS.

- Westley, F. 2008. The social innovation dynamic. https://www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/cpipe/documents/Why/Frances%20Westley%2C%20Social%20Innovation%20Dynamic.pdf (accessed 10 January 2023).

- Woods, M. n.d. Creative ruralities. Paper presented to the ‘Creativity on the Edge’. Symposium, Moore Institute, National University of Ireland Galway in 2012. https://www.global-rural.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Creative-Ruralities.pdf (accessed 10 January 2023).

- Yin, R.K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. London: SAGE.