ABSTRACT

The urgent need to address the current climate crisis has highlighted the need to shift from planning to implementing decarbonisation strategies. Despite the importance of shifting towards the implementation of strategic plans and the increasing ubiquity of place-based approaches to decarbonisation, few studies have considered the dynamic of how place is mobilised and the scales at which narratives are translated into action. The aim of the article is to understand the ways in which place and scale are incorporated into the governance of place-based decarbonisation visions by drawing upon a relational framing. Based on semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders and a document review, the article focuses on how place is used to develop and justify two different approaches for supporting localised decarbonisation, Local Area Energy Plans and the Energy Innovation Agency in Greater Manchester, UK, a city region aiming to achieve carbon neutrality by 2038. The findings reveal that achieving localised decarbonisation ambitions is contingent upon the interaction between multiple places and scales, as well as the need for an overarching guiding framework. The authors conclude that Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation ambitions incorporate both absolute and imagined understandings of place, with place being both created and mobilised to achieve decarbonisation ambitions.

Introduction

Towns, cities, and city regions are increasingly undertaking action to support the achievement of low-carbon ambitions. Inaction at national and international scales and the opportunity to integrate particularities of place into decarbonisation approaches justify rescaling decarbonisation actions to more localised scales (Gudde et al. Citation2021). Place-based decarbonisation approaches reflect the particular contexts, resources, priorities, and stakeholders present (Pike et al. Citation2016), which increases engagement with the approaches developed (Raven & Stripple Citation2021). Furthermore, rescaling decarbonisation approaches to more localised scales can increase the speed of decision-making processes and the impacts felt (Rutherford & Coutard Citation2014). However, the development of place-based decarbonisation approaches may reduce the ability to replicate approaches in other contexts, due to differing geographical, economic, or governance characteristics (Rutherford & Coutard Citation2014; Rodríguez-Pose & Wilkie Citation2017).

The omnipresent threat of climate change, and looming target dates for achieving carbon neutrality demonstrate the need to shift from developing decarbonisation approaches to implementing the actions outlined. However, the shift towards implementation raises questions about the scales at which actions will occur and the governance structures required. In reflecting upon these questions, the aim of this research article is to understand the ways in which place and scale are incorporated into the governance of place-based decarbonisation visions. Despite the importance of shifting towards the implementation of strategic plans and the increasing ubiquity of place-based approaches to decarbonisation, little research to date has considered the dynamic of how place is mobilised and the scales at which narratives are translated into action.

This article addresses the research gaps identified through the case study of Greater Manchester, a city region in the North West region of England. The Greater Manchester case is used to identify and discuss how decarbonisation ambitions are created and by whom, and how the spatiality of decarbonisation processes is produced and translated into actions at different scales. The article contributes to understandings of place, including the agency of places themselves and how places can perpetuate existing power relations. The use of Greater Manchester as a case study is justified by the city region’s ambition to achieve carbon neutrality by 2038 through a place-based approach, and by the multiple scales at which decarbonisation actions are situated.

The insights presented were developed from 34 semi-structured interviews with stakeholders associated with the city region’s decarbonisation ambitions, and from a review of policy and strategy documents related to those ambitions. To support the analysis in this article, we adopted a relational framework that allows for the interrelations of structures, practices, objects, places, and identities across scales to be considered (Hart Citation2002; Becker et al. Citation2016a). These relational insights are combined with understandings of multilevel governance to unpack how interactions between multiple places, scales, and actors associated with the development and implementation of decarbonisation approaches.

The structure of the article is as follows. The theoretical framing introduced first, followed by an introduction to the case study of Greater Manchester. Thereafter, the methodology is presented. The analysis section discusses how Greater Manchester has drawn upon place when developing and justifying decarbonisation approaches, the associated power dynamics, and the different scales of action. The article is concluded with a reflection on the multiplicity embedded in place-based decarbonisation approaches and the value of considering the different interconnections and power dynamics when developing decarbonisation approaches.

Theoretical framing

This section outlines the theoretical framings that inform the arguments presented in this article. Current understandings of place, relationality, and multilevel governance are discussed in relation to decarbonisation.

Decarbonisation and place

There is an increasing consensus that cities play an important role in progressing sustainable transformations globally (Bulkeley et al. Citation2010). Cities and city regions are considered critical sites for action because they are ‘centres of technical, social and political innovation’ (OECD Citation2008, 48). They are also locations where different policies, ranging from the supranational to the subnational level, are implemented (Sassen Citation2010). The scale of the city enables local initiatives to be developed, which are ‘experimental, impermanent and iterative’ (Grandin & Sareen Citation2020, 73).

Different places experience different opportunities and constraints relating to decarbonisation (Bridge Citation2018), due to having different resources, cultural histories, and governance structures (Roelich Citation2018). As such, situating decarbonisation action at the local scale and regional scale highlights the need to consider the geography of transformation (Coenen et al. Citation2021). The geography of transformation emphasises the importance of considering the spatial contexts in which actions, including decarbonisation, are to be implemented, as well as the spatial impacts of the actions taken. As commented by Roelich (Citation2018, 28) in her research on transforming towards decentralised energy systems, there is the need to ‘recognise, value and work with the different motivations, the local histories and the varied lie of the land’. The influence of place characteristics highlights the value of having ‘context-specific’ understandings when developing decarbonisation approaches (Rutherford & Coutard Citation2014). This suggests that in order to implement different approaches and achieve decarbonisation ambitions successfully, there is a need to recognise the particularities of the places where actions are implemented.

By rescaling decarbonisation processes to more localised scales, place-based approaches can be developed. Within place-based decarbonisation approaches, consideration is given to how processes, practices, and policies are ‘grounded at particular moments in specific places’ (Rutherford & Coutard Citation2014, 1355). Thus, policies and strategies are developed that reflect the particular opportunities and constraints of local conditions and realities (Rodríguez-Pose & Wilkie Citation2017). A number of contextual factors affect the achievement of decarbonisation ambitions, including the visions and policies of actors and organisations, the institutions present, natural geographical resources, and market characteristics (Hansen & Coenen Citation2015). Acknowledging the particularities of place is particularly relevant when developing approaches to achieve decarbonisation ambitions, as there is the need for both technological and institutional change and a reordering of social and political relations (Bulkeley et al. Citation2010; Burke & Stephens Citation2018).

There are a number of benefits associated with the development of place-based decarbonisation approaches, including social and economic advantages, a closer connection between needs and policies, and the ability to adapt strategies to particular contexts (Pike et al. Citation2016). Situating approaches within a particular context facilitates engagement and encourages individuals to think about their futures (Rodríguez-Pose & Wilkie Citation2017). Place-based approaches and policies are tailored to the local conditions, characteristics, opportunities, and challenges (Rodríguez-Pose & Wilkie Citation2017). Establishing policy at more localised scales means that ‘stakes are more pertinent and contextualised’ (Coutard & Rutherford Citation2010, 712), which can lead to more effective policy implementation as actions are attuned to local conditions.

Despite the benefits of developing localised place-based approaches to decarbonisation, there is an opportunity to refine place-based approaches. Typically, decarbonisation ambitions and strategies are focused on the city scale rather than particular on populations or areas, which can constrain the effectiveness and impact of strategies (Rice Citation2014). One example is blanket campaigns that promote public transport usage, even though large populations already use these modes of transport (Rice Citation2014). Focusing on achieving ambitions at the scale of the city can blur the diversity of contexts and experiences at subcityFootnote1 and/or regional scales. Consequently, there is an opportunity to rescale ambitions and visions yet further, in order to reflect to a greater extent the heterogeneity within.

Decarbonisation and relational understandings

Although situating processes and practices at the city scale enables the consideration of local contexts, relational understandings highlight how local contexts are constructed in relation to other spaces and scales (Coutard & Rutherford Citation2010). Cities are not isolated entities (McCormick et al. Citation2013); rather, they are influenced by their multi-scalar relations. Cities face pressures ‘from above’ and expectations ‘from below’ (McCormick et al. Citation2013), and they can be considered mediators of these different scales. Both global and local flows of ‘capital and resources, people and ideas, energy and waste’ are facilitated through cities (Rice Citation2014, 382). The multiplicity of scales and relationships associated with cities demonstrates the need to consider how actions taken within cities to support decarbonisation ‘fit’ into other scales (García-Sánchez & Prado Lorenzo Citation2009).

The particularities of different places are determined by the ‘interrelations of objects, events, places and identities’ (Hart Citation2002, 14). Applying a relational understanding to cities helps to unpack the multi-scalar relationships that exist both within and beyond those cities. There is a need to appreciate the scalar dynamics and politics of cities by considering the ‘shifting relationships of local, trans-local, national and international structures and practices, and the ways these are socially shaped’ (Becker et al. Citation2016a, 97). Actions occurring at particular scales can only be understood in relation to other scales and the socio-spatial processes that produce them (Howitt Citation1998). A relational conception of cities acknowledges the multiplicity of existing configurations and highlights potential futures (Massey Citation2005). As such, the city is a ‘multiple entity’ made up of multiple ‘urbans’ that have been developed both intentionally and unintentionally (Becker et al. Citation2016b). Despite urban scale being materialised in particular ways, it is also ‘open and continuously renegotiated’ (Bouzarovski & Haarstad Citation2019, 261). The negotiation of scale demonstrates the impact of discourse, power, and politics on outcomes (Bouzarovski & Haarstad Citation2019).

Focusing on processes of decarbonisation, relational understandings help to unpack the complexities embedded within the transition to low-carbon societies. Cities, and the decarbonisation processes within them, shape and are shaped by incumbent energy systems and interests (Hommels Citation2005). The impact of incumbency on decarbonisation is demonstrated by both the advocation of carbon capture and storage technologies that enable powerful fossil fuel companies to maintain current practices and dominance (Meadowcroft Citation2009) and the requirement for new-build homes in the UK to have EV chargers – indicating the proliferation of and lock-in to car usage (Department for Transport Citation2022). The incumbency of energy systems and interests are institutionalised through governance, finance, business structures, and technologies situated at multiple scales (Hommels Citation2005). Consequently, energy systems themselves are shaped by political, economic, and cultural structures, whilst simultaneously shaping social processes and practices (Bridge Citation2018).

The co-ordination of low-carbon transitions within cities requires multiple scales of action. Actions to support localised transitions are not constrained to actors within the city itself, but rather actors situated at other scales perform activities that influence a city’s transition (Bulkeley et al. Citation2010). Localised energy transitions are embedded in and influenced by other scales (Grandin and Sareen Citation2020). When developing decarbonisation approaches, there is a need to consider the diverse spatialities of cities, including flows, connections, networks, sites, places, and materiality (Leitner et al. Citation2008). By considering the city as relational and co-constitutive emphasises how cities can only be understood from their relationships with other places and scales (McFarlane Citation2011). Also, the interaction between subcity scales needs to be acknowledged within these relational understandings, as presented in this article.

The multilevel governance of decarbonisation

Increasingly, governance practices are distributed across scales, including national, regional, and local scales (A. Smith Citation2007). Multilevel governance captures the interactions between supranational and subnational state and nonstate actors in defining and achieving collective goals (Betsill & Bulkeley Citation2006). A multilevel governance perspective engages with the ‘multiple tiers of government and spheres of governance’ through which ambitions are constructed and contested, and this helps to explain why certain actions either are or are not being taken (Bulkeley & Betsill Citation2005). As clearly expressed by Bulkeley & Betsill (Citation2005, 43), ‘multi-level governance perspectives provide insight into the opportunities and contradictions which emerge in the interpretation and implementation of urban sustainability across a range of scales and spheres of governance’. Addressing environmental issues, such as climate change, will benefit from the engagement with multiple places of governance (McFarlane Citation2011). Interventions to address climate change and to support decarbonisation are dependent on and situated within a heterogeneous assemblage of artefacts, knowledge, authority, and agency (Murray Li Citation2007), within which the interventions can also act as a means of governance (Castán Broto & Bulkeley Citation2013).

Governance practices can be considered as either ‘soft’ or ‘hard’: soft governance refers to building networks and sharing views, whereas hard governance involves implementing targets and reforming institutions (A. Smith Citation2007). Within the UK, the highly centralised energy system and associated lack of legislative power and funding resources held by municipal governments leads to those governments predominantly drawing upon ‘soft’ governance mechanisms (Hunt & Milne Citation2013; Cowell et al. Citation2017).

The establishment of strategic visions is an example of soft governance mechanisms implemented by municipal governments. The strategic visions established by municipal governments provide a common goal and mobilise action by other actors related to the vision in question (Karvonen Citation2020). Through the visions, developed understandings of what ‘low carbon’ is and the actions required to achieve decarbonisation are outlined (Bulkeley et al. Citation2014), with both technological opportunities and societal expectations being presented (Jasanoff Citation2015). By articulating ambitions within the context of a particular place, abstract ambitions are translated into concrete decisions, investments, and practices (Meadowcroft Citation2005). Organising at a municipal level provides the flexibility to experiment with different solutions and identify contextual challenges that need to be addressed (Cervas & Giancatarino Citation2017). Through localised visions, ‘concrete agendas reflecting the specific requirements and opportunities of a particular regional context’ are established (Späth & Rohracher Citation2010, 456), and this in turn increases the tangibility of actions. However, the visions and ambitions developed may not fully represent societal needs and priorities because the visions are influenced by the assumptions of the decision-makers that have developed them (Sadowski & Levenda Citation2020).

To date, researchers have considered the benefits of place-based approaches (Rutherford & Coutard Citation2014; Pike et al. Citation2016; Rodríguez-Pose & Wilkie Citation2017), the relational nature of place (McFarlane Citation2011; Becker et al. Citation2016a; Bridge Citation2018), and how narratives are used to articulate decarbonisation ambitions (Späth & Rohracher Citation2010; Felt Citation2015; Jasanoff Citation2015). However, little research has focused on the relationship between place, strategic visions, and achieving localised decarbonisation ambitions. Developing understandings of this relationship would support the move from planning to implementing strategic plans for decarbonisation. This article considers how both absolute place and imagined place are mobilised and created to support the achievement of place-based decarbonisation ambitions. The following section introduces the case study of Greater Manchester and outlines the methodology adopted in our research.

Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision

Greater Manchester, a city region in the North West region of England, comprises 10 local authorities (Bolton, Bury, Manchester, Oldham, Rochdale, Salford, Stockport, Tameside, Trafford, and Wigan). Greater Manchester Combined Authority has outlined ambitions to achieve carbon neutrality by 2038, 12 years ahead of the UK Government’s 2050 target (Greater Manchester Combined Authority Citationn.d.). The intention is for Greater Manchester to become a ‘clean, carbon neutral, resilient city-region’, with citizens and businesses adopting ‘sustainable living and business practices, focusing on local solutions to deliver a prosperous economy’ (Greater Manchester Combined Authority Citationn.d. 16). Within the decarbonisation approaches developed, emphasis is placed on people and place; individuals need to shift their practices and there is a focus on developing infrastructures to support the achievement of ambitions (Greater Manchester Combined Authority Citationn.d.). The decarbonisation ambitions of Greater Manchester and the approach taken justify treating Greater Manchester as a case study for localised place-based decarbonisation approaches.

Methodology

In order to develop understandings of the development and implementation of Greater Manchester’s place-based decarbonisation ambitions, we performed document analysis and held 34 semi-structured interviews. The document analysis included policy and strategy documents related to Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation ambitions, and the semi-structured interviews were held with stakeholders associated with decarbonisation processes in Greater Manchester.

The document analysis focused on outputs by the municipal government (Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA)) and associated partners concerning the city region’s decarbonisation ambitions and strategic plans. Document analysis can support research in a number of ways, including providing context, providing supplementary data, and corroborating findings from other sources, and this was the case in our research (Bowen Citation2009). The document analysis included a range of documents, such as strategic plans, policy documents, meeting minutes, and presentations. Both content and thematic analyses were performed and the information was categorised in relation to the aim of this article (i.e. to understand the ways in which place and scale are incorporated into the governance of place-based decarbonisation visions), and patterns within the data were identified (Bowen Citation2009). In aligning with the research objectives of understanding how place is mobilised and the scales at which decarbonisation narratives are translated into action, document analysis focused on established narratives, actions to be taken, and the actors expected to take those actions. Key insights were highlighted and cross-referenced across the documents.

When analysing documents for research purposes, focus is placed on ‘establishing the meaning of the document and its contribution to the issues being explored’, as documents are not necessarily ‘precise, accurate, or complete recordings of events’ (Bowen Citation2009, 33). Documents are not neutral, given that they are produced for a particular audience and purpose (Atkinson & Coffey Citation2011). By reviewing a range of documents produced about Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation ambitions, we gained insights into intended actions and outcomes (Crowther et al. Citation2021). Coupling these insights with the understandings obtained through the semi-structured interviews provided us with the opportunity to identify where there were disparities between ‘official’ narratives and the ‘actual’ experiences of what was narrated. This combination of methods also supported the triangulation of understandings, which in turn increased the reliability and validity of our research (Golafshani Citation2003).

The semi-structured interviews were held between October 2020 and July 2021 with a range of stakeholders associated with Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation ambitions and its low-carbon agenda (). Ethical approval for the research was obtained from the University of Manchester Ethics Committee. Due to restrictions relating to the COVID-19 pandemic, the interviews were held online via Zoom. As there are only marginal differences between data collected from online interviews and in-person interviews (Krouwel et al. Citation2019), and due to the increasing understanding of and accessibility of online video calling (Hacker et al. Citation2020), we do not consider that the use of online interviews had a negative effect on the data collected.

Table 1. Interviewees’ position held, transcription code, and numbers

The main part of participant recruitment was done through purposive sampling. The individuals approached were considered to be knowledgeable about and involved in Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation ambitions (Palinkas et al. Citation2015). There were also instances of snowball sampling, whereby participants recommended other individuals who could provide insights into the topics discussed and at times facilitated the interactions. When identifying and contacting participants, our intention was to ensure that diverse stakeholders connected with Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation ambitions were interviewed in order to obtain an overarching understanding of the city region’s ambitions and practices. The participants provided informed consent after reading through a participant information sheet that outlined our research and how their data would be used.

During the interviews, the participants were asked to reflect on different actions taken to support the achievement of Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation ambitions, the scale at which those actions had been taken, and what they believed was the optimum scale for taking decarbonisation actions. The responses to these questions provided insights into the scales at which decarbonisation ambitions are enacted in Greater Manchester. As the interview focused on Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation ambitions, understandings of place were incorporated into participants’ responses, particularly when asked about the overarching ambition and narrative of achieving carbon neutrality by 2038. During the interviews, the participants discussed the narratives developed to facilitate the achievement of decarbonisation ambitions and how place was incorporated into those narratives. Follow-up questions were used to gain further details regarding points raised in the interviews, particularly when participants mentioned something of interest to the overarching research objectives (Saldaña Citation2011). At times, anonymised points made by previous research participants were presented to individual interviewees, and this provided the opportunity for responses and introduced a more discursive element between the participants’ responses, despite the use of interviews.

The interviews were transcribed and coded thematically, using the software nVivo (J. Smith & Firth Citation2011). When analysing the transcripts, initial coding focused on identifying discussions about Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation ambitions, the approaches developed, and the scale of those approaches, with a second round of coding focusing on the detail within these broader categories (Timmermans & Tavory Citation2012). The codes identified during the first round of coding were high-level and broad, relating to the questions and applied to large sections of the transcribed text (Timmermans & Tavory Citation2012). The second round of coding was more analytical (Timmermans & Tavory Citation2012), with codes including ‘actors’, ‘challenges’, ‘benefits’, ‘justification’, ‘relationship’, and ‘tensions’. The findings from the analysis highlighted the narratives developed by Greater Manchester to support the achievement of decarbonisation ambitions, as well as how the narratives were being mobilised, by whom, and at what scales. Insights into how place is created and mobilised to support decarbonisation in Greater Manchester can be applied to other places that are developing place-based visions and approaches to decarbonisation.

The following discussion section draws upon a relational framework, in combination with the multilevel governance approach to unpack the processes of shifting from planning to implementing place-based decarbonisation visions.

Discussion

Incorporating place into governance

Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision and the actions outlined to support its achievement are grounded within the specific characteristics of the city region. Greater Manchester's place characteristics inform the decarbonisation actions that can be taken, as well as the governance structures established to support the achievement of those decarbonisation actions.

Greater Manchester’s ambition to achieve carbon neutrality by 2038 and the actions outlined to achieve this can be considered a vision. Visions can be conceptualised collectively as a ‘soft’ governance mechanism, since through their development and articulation a common ambition can be established, and individuals can collectively mobilise in relation to them (Karvonen Citation2020). A component of Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision, which is referenced in strategic documents produced by the municipal government, is that ‘everyone has a role to play’ (Greater Manchester Combined Authority Citationn.d.). Both the involvement of multiple actors and the apparent diffusion of responsibility for achieving Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision reflect broader trends of rescaling, whereby a greater number of actors can be involved (McGinnis Citation2011).

One municipal government employee stated: ‘we’re a convener, a coordinator […] our role is not just to do everything, because we’re not best placed to do everything’ (RG1). The diffusion of responsibility for achieving Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision is recognised by stakeholders within the city region, as summarised by one participant who was working for a climate change organisation:

the current approach is very much around trying to engage and support and mobilise action by residents and businesses, as opposed to assuming that the city council or central government is going to have a magic wand or a magic pot of money to throw at the problem. (C2)

Despite the requirement of collective action to achieve Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision, there is variation in how the 2038 target and associated actions are perceived by stakeholders within the city region. Some stakeholders align with the municipal government’s view that the vision will help to mobilise action, such as a policy officer within one of the city region’s local authorities, who said: ‘It’s great to have that overarching aim and target for the region’ (LA2). However, for others, Greater Manchester’s vision for achieving carbon neutrality is perceived more negatively, and they expect that it will not achieve the desired outcomes. One environmental activist within the city region was concerned that the 2038 target could lead to inaction, as ‘it could potentially cause people to think “well we’ve got a long time to sort this out”, rather than giving it the level of urgency’ (ACT4) it requires. Similarly, a researcher involved with the development of local decarbonisation plans reflected that simply outlining the vision was not enough, and that greater efforts needed to be made by the municipal government to outline the actions that need to be taken and to ‘do the thinking about how you actually get there’ (R2). The diverse ways in which Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision is perceived and the lack of collective support for it will probably impact the extent to which individuals engage with the decarbonisation actions outlined by the city region’s authorities.

Despite lacking unilateral support, both achieving carbon neutrality by 2038 and the distribution of responsibility remain the guiding vision for addressing climate change in Greater Manchester. Greater Manchester’s 5-Year Environment Plan for Greater Manchester: 2019–2024 (5YEP) is a key strategy document that outlines a pathway for achieving carbon neutrality within the city region, and it supports the mobilisation of resources and actors (Greater Manchester Combined Authority Citationn.d.). Within the 5YEP, emphasis is placed on developing an innovative place-based approach to decarbonisation (Greater Manchester Combined Authority Citationn.d.).

The 5YEP presents a strategic pathway for achieving Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision. As commented by a municipal government employee, ‘the 5YEP provided everybody with the framework and structure, it provided some clear layman’s terms messaging and it provided something that everybody could either corral around or hang off’ (RG1). The decarbonisation actions outlined in the 5YEP have helped to align actors with local authorities, and some interviewed study participants commented on how they themselves were working towards the 5YEP (LA1, LA5). The actions presented within the overarching strategy of the 5YEP are supported by other strategic documents, frameworks, and plans, including Greater Mnchester’s Spatial Energy Plan and Smart Energy Plan (Owen Citation2019; GMCA Citation2021).

However, some stakeholders in Greater Manchester believed that the 5YEP does not reflect the diversity of contexts, preferences, and perspectives of different actors within the city region. One interviewee in consumer protection reflected that the actors developing decarbonisation actions ‘underplay how much people should have a say in the kind of things that would make them change their behaviours’ (C3) in order to align with the decarbonisation vision. Building upon this idea, an academic that researched only low-carbon transitions (A5) argued the importance of engaging different individuals, since the need for collective action to achieve Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision required approaches that would ‘work’ for all members of the population. The study participants’ critiques of how Greater Manchester’s vision has been established, as well as the actions outlined, raise questions about the governance of the decarbonisation vision and its current inability to reflect the needs and experiences of everyone in the city region.

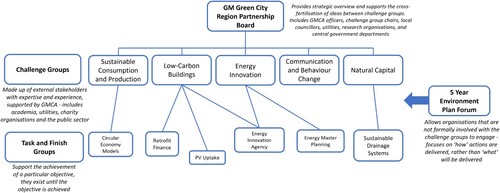

Existing governance structures have been restructured and new structures have been established to support the achievement of Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision () (Bellinson et al. Citation2021). Five Challenge Groups have been created to support progress on achieving Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision and progress the 5YEP. Each Challenge Group brings together a range of relevant actors to identify and implement priority actions (Atherton Citation2019). Additionally, a 5 Year Environment Plan Forum (5YEP Forum) has been established to enable organisations not formally involved in the Challenge Groups to contribute to the city region’s decarbonisation narrative (Atherton Citation2019). The interaction between the different actors within the Challenge Groups and the contributions made through the 5YEP Forum inform the decarbonisation actions taken. As such, the motivations, priorities, and understandings of the actors associated with these governance structures are embedded within the decarbonisation approaches developed (Akrich Citation1992).

Fig. 1. Simplified governance structure of Greater Manchester’s carbon neutrality ambitions (based upon Atherton Citation2019)

The Challenge Groups and 5YEP Forum might reinforce the city region’s vision for achieving decarbonisation vision through innovative approaches and collective action. Bellinson et al. (Citation2021) report that based on analysis of data provided by the GMCA, Greater Manchester’s Challenge Groups and 5YEP Forum had a total of 227 members, of which 17% were municipal government employees, 13% were in academia, and 12% were associated with infrastructure. Many of the strategic partners involved in the Challenge Groups had previously collaborated with the municipal government, as commented on by a municipal government employee: ‘a lot of the engagement comes from established relationships, especially in the energy sector […] although we haven’t always had a Challenge Group, there has always been some form of group of people working together on energy projects’ (RG2).

The tendency to draw upon established working relationships and collaborations to develop and implement Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision was criticised by an environmental activist, who said: ‘I worry a bit that some of the partnerships are the kind of the lower hanging fruit […] it’s the people who often sound or look a bit like you’ (ACT3). The reconfiguration of existing governance structures to support decarbonisation actions within Greater Manchester facilitates the continuation of existing practices and approaches. The perpetuation of existing actors and networks acts as a barrier to the incorporation of alternative perspectives and approaches. Governance mechanisms influence and are influenced by power dynamics, with this in turn affects the established decarbonisation visions and the approaches designed to support their realisation.

Furthermore, city regions are not isolated entities (McCormick et al. Citation2013), which demonstrates the value in considering the relationality and multilevel governance of Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision. The achievement of Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation ambitions is dependent on the involvement and alignment of actors situated at multiple scales (Bulkeley et al. Citation2014), with these interactions influencing the decarbonisation actions that can be taken. As reflected on by an academic who researched the decarbonisation of buildings (A2), the achievement of Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision is dependent on support and funding from the national government. Funding for projects to support decarbonisation in Greater Manchester comes predominantly from external grants, with previous projects being funded by the European Union (EU) and the UK Government’s Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) (Bellinson et al. Citation2021). Decarbonisation actions taken within Greater Manchester need to align with these funding calls demonstrating the multiscalar influence the city region’s actions. The receipt of funding from external grants is conditional upon Greater Manchester's decarbonisation actions aligning with the priorities and interests of the funding organisations. The temporalities and priorities of different actors in relation to decarbonisation ambitions influences the approaches developed by Greater Manchester (Bulkeley et al. Citation2010; McFarlane Citation2011). Greater Manchester’s place-based decarbonisation vision and its associated governance structure influence the framing and focus of actions taken. The following two subsections discuss how ‘absolute’ and ‘imagined’ place influence Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision.

Absolute place: Local Area Energy Plans and their relationality

Framing decarbonisation visions within the specificities of place enables implementation approaches to be developed that capture ‘absolute’ place characteristics. Within this article, we understand absolute place to include both physical geographical features and human socio-economic contexts of a particular location (Castree Citation2003). Within the 5YEP, reference is made to the geographical opportunities and constraints of the city region, the current energy demand within the city region, and the characteristics of the population and existing buildings (Greater Manchester Combined Authority Citationn.d.). According to a municipal government employee involved in the implementation of the 5YEP, situating ambitions within the particular context of place helps to ensure that recommended actions are ‘of benefit to the region and the people in the region’ (RG2). The development of place-based decarbonisation approaches helps ensure that the actions taken are relevant to the particular context of Greater Manchester (Coutard & Rutherford Citation2010; Pike et al. Citation2016). According to an academic who was interested in the governance of localised energy transitions, incorporating specific understandings of place characteristics into decarbonisation approaches helps to demonstrate ‘why it's [decarbonisation is] a particular opportunity in these ways for this region’ (A3).

The Local Area Energy Plans (LAEPs) developed for each of the local authorities within Greater Manchester incorporate absolute place characteristics. Each LAEP included modelling techniques to develop a pathway for achieving decarbonisation by identifying the best configuration of low-carbon technologies (Walters & Line Citation2022). The LAEPs acknowledge the particularities of the local authority to which they relate, as consideration is given to the different geographical and socio-economic characteristics of places, as well as the residents’ perceptions (Walters & Line Citation2022). According to the study participants, the LAEPs capture the unique characteristics of each local authority (LA5), and inform relevant actors about what is possible within their locality (RG1).

The LAEPs capture the variation within Greater Manchester and how the different contexts of the local authorities will influence their priorities, resources, and ability to implement required actions (). The variation in population density (as an indicator of housing types and their spatial distribution) and social characteristics, such as income deprivation and fuel poverty (which influence the capacity for undertaking decarbonisation actions), across the local authorities have contributed to different decarbonisation actions being suggested within the LAEPs. A local authority policy officer said that ‘different approaches will work in different boroughs’ (LA5). For example, the LAEP for Bury includes the insulation of homes and the installation of solar PV as low-regret options to support decarbonisation, reflecting the current housing conditions and the available space for localised generation (Walters & Line Citation2022).

Table 2. The diversity in Greater Manchester’s Local Authorities, based upon different characteristics and with the national average for England included for comparison

However, it is not enough to simply rescale decarbonisation actions to the scale of local authorities, as many actions within the LAEPs require the participation of individuals, households, and businesses. For example, Greater Manchester has a target to install 116,000 heat pumps by 2024, dependent on household participation (Walters & Line Citation2022). However, not all households within Greater Manchester are able to participate because the actions outlined do not align with their circumstances and appropriate support is not always available (Crowther et al. Citation2021). The variation within local authorities highlights the complexity of implementing decarbonisation visions, and the multiple scales of interaction (Cowell et al. Citation2017).

The achievement of Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision is dependent on multi-scalar interactions; the overarching decarbonisation vision is framed at the city region scale, the implementation plans outlining the actions to be taken are focused at the local authority scale, and many of the actions outlined within these implementation plans require the participation of individuals. The interactions between places and scales, and the cumulative nature of the actions taken all highlight the importance of co-ordination for achieving decarbonisation. A policy officer within one local authority (LA2) commented that there was a need to consider the coordination of the different actions taken within the different places and across multiple scales in order to achieve the intended outcomes.

Additionally, the focus of the LAEPs is influenced by different interconnections, and can be considered relationally. The actions outlined within each local authority’s LAEP aligns with the municipal government’s vision for how to achieve decarbonisation. For example, the focus on technological solutions within the LAEP models reflects Greater Manchester’s ambitions to develop an energy system that is ‘smart, sustainable and fit for the future’ (Greater Manchester Combined Authority Citationn.d.). Furthermore, the development of the LAEPs occurred as a result of the municipal government obtaining funding (Greater Manchester Combined Authority Citation2021), which in turn supported the development of approaches that reflect the GMCA’s vision for achieving decarbonisation.

Imagined place: the Energy Innovation Agency and issues of fragmentation

As with absolute place, imagined place is used to justify the actions developed to support the achievement of Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision. Drawing upon Anderson’s idea of imagined communities (Anderson Citation1983), we understand imagined places as a product of how places are represented through various mediums. As such, strategic visions, including Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision, can be considered imagined places. Through visions, a future is outlined, which individuals should strive to achieve and which captures both social and technological aspects of place (Jasanoff Citation2015). The future of place presented through visions is dependent on the collective work of different actors coming together (Felt Citation2015).

Greater Manchester’s municipal government draws upon the historical legacy of the Industrial Revolution to establish the city region as a place of innovation, legitimising the ambition to adopt an innovative approach to decarbonisation. The framing of Greater Manchester as having ‘a history of industrial and people powered action’ (Greater Manchester Combined Authority Citation2021) justifies the city region’s focus on innovative decarbonisation approaches with ‘individual, community, industry and institutional action at its heart’ (Greater Manchester Combined Authority Citation2021). This imagination of Greater Manchester is further reinforced through the inclusion of the Manchester worker bee symbol on documents and web pages that outline decarbonisation visions. The worker bee symbol emerged during the Industrial Revolution to reflect the hard work ethic of Mancunians, the hive of activity within the city (city region), and the unity between individuals in Manchester (Manchester City Council Citation2023a). The use of the Manchester worker bee symbol emphasises the collective identity of Greater Manchester and everyone coming together to play their part, and as such acts as a soft governance mechanism (A. Smith Citation2007). Framing the city region’s decarbonisation vision in relation to the historical legacy of Greater Manchester not only justifies the actions developed, but also depoliticises the decisions made and obscures underlying power dynamics (Cantoni & Rignall Citation2019).

The imagined places drawn upon within Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision contribute to material infrastructures and outputs. For example, references made to innovation materialised in the Energy Innovation Agency (EIA). The EIA was established through the Task and Finish Group associated with the Energy Innovation Challenge Group (), with the purpose of facilitating low-carbon innovation within Greater Manchester (Atherton Citation2019; Energy Innovation Agency Citation2023a). Innovation is facilitated through the provision of bespoke support from the partners involved, including the municipal government, three universities, a property developer, an environmental services provider, an energy company, and a technology company (Energy Innovation Agency Citation2023b). Innovations supported through the EIA align with Greater Manchester’s vision of decarbonisation, namely an innovative, place-based approach.

The partners involved with the EIA influence the innovations that are supported through the EIA. The support provided by the EIA reflects the partners (and networks) involved with the agency, meaning that the perspectives, knowledge, and resources of these partners will guide the innovation projects implemented and the approaches taken. Through the EIA, the dominant vision of decarbonisation as determined by influential actors manifests in outputs, thus highlighting how visions are able to guide and influence the actions taken (Bulkeley et al. Citation2014; Karvonen Citation2020). The politics within the urban space contribute to the social, cultural, and material spaces of change and innovation established (Castán Broto & Bulkeley Citation2013).

Furthermore, the constructed nature of visions (Li & Lin Citation2022), and by association the constructed nature of imagined place, highlight how different imaginations of Greater Manchester exist and could be drawn upon to guide and justify alternative approaches to achieving decarbonisation. The multiplicity of place demonstrates the opportunity for alternate future configurations (Massey Citation2005). The focus on innovation through the EIA is in part a product of the formal governance structure it was developed through, and the range of actors associated with the Energy Innovation Challenge Group (Bellinson & Smith Citation2021). As such, it highlights the influence of governance structures and the associated power dynamics, and the consequences of these on material outputs.

The power dynamics supported and reinforced through the formal governance structures supporting the achievement of Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision provide little opportunity for alternative visions to be considered. Questions concerning who develops the visions and how this influences the material outputs based on their understandings of place were discussed by an academic who was interested in localised energy transitions, and according the same academic, ‘the question of who’s in the room is still is still pertinent in that it’s probably still quite tied to […] industry, government perspectives’ (A3). The repurposing of existing governance structures enabled the perpetuation of existing power dynamics and working relationships. As reflected on by a practitioner who supported those in energy poverty (RG3), the dominance of certain perspectives and approaches to decarbonisation can lead to a marginalisation of certain groups within decarbonisation approaches. Governance structures can perpetuate existing power dynamics and there is therefore a need to reflect critically on who is involved in the development of place-based decarbonisation visions.

As in the case of the discussed LAEPs, the achievement of Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision requires different innovations supported through the EIA in order to be coordinated. There is the need to align the actions taken and address particular areas in order to achieve broader decarbonisation ambitions (Bulkeley et al. Citation2014). However, such coordination between innovation projects is perceived as lacking, as stakeholders viewed the current innovation landscape as fragmented due to a lack of guiding framework (ACT5, LA2).

The fragmentation of the actions taken through support from the EIA and the LAEPs reflects broader concerns related to localised decarbonisation actions. One environmental activist commented that ‘it’s all a bit bitty. There’s lots of odd projects which tend to be, I think, driven fairly opportunistically in terms of where there’s grants to do bits of work, who the willing actors are, and so on’ (ACT5). This sentiment was shared by a participant who was working within a specialised research organisation and who commented that ‘lots of little projects that aren’t coordinated together won’t make the changes required happen’ (R2). Cugurullo’s concept of ‘Frankenstein urbanism’ (Cugurullo Citation2018) captures the lack of connection between different urban experiments conducted within the same place. When considered in isolation, such experiments situated at different scales function well, but tension emerges when they are juxtaposed against each other (Cugurullo Citation2018). To address such fragmentation, there is the need to ensure alignment across the multiple scales and places associated with the development and implementation of decarbonisation actions.

Conclusions

To support the achievement of Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation ambitions, both absolute and imagined places are drawn upon to justify, legitimise, and situate the decarbonisation approaches developed. The approaches developed to facilitate the achievement of decarbonisation ambitions are influenced by the governance structures established and their associated power dynamics.

Place supports progress on achieving decarbonisation ambitions by acting as a frame for the actions taken. The achievement of decarbonisation ambitions is dependent on cumulative action being taken in multiple places and at multiple scales. The places where decarbonisation actions are taken are connected to, influence, and are influenced by other places (McCormick et al. Citation2013; Grandin & Sareen Citation2020). Despite the different scales of actions taken, such as those focused on at local authority scale, at the household level, or in individual innovation projects, the actions are aligned as a result of the common goal developed at the city region scale. Articulating ambitions at the city region scale facilitates the coordination of different actors, as a common goal is established.

Acknowledging the multi-scalar nature of place-based decarbonisation approaches and associated governance structures helps to identify who is involved in localised decarbonisation actions and their underlying motivations. Different places have different power relations, capacities, and opportunities, all of which influence the decarbonisation approaches developed (Bridge Citation2018; Roelich Citation2018). Consideration of the different interrelations of place-based approaches facilitates the identification of embedded political processes and power dynamics. The identification of these underlying political processes and power dynamics supports the development of decarbonisation approaches that better cover the different circumstances experienced by different individuals within a place. The governance structures established, which build upon existing structures, perpetuate existing power relations and facilitate the dominance of certain perspectives and ideas. Acknowledging the multiplicity of places and actors associated with localised decarbonisation approaches helps to capture the embedded complexity and support the development of more nuanced just approaches to achieving ambitions (Coutard & Rutherford Citation2010; Pike et al. Citation2016).

This article has developed understandings of how place is mobilised to support decarbonisation visions and the scales at which place-based decarbonisation visions are translated into action. We have drawn upon theoretical framings of relationality and multilevel governance in our analysis of the politics and power dynamics of Greater Manchester’s place-based decarbonisation approaches. Our article highlights the paradoxes of the multiple scales embedded within localised, place-based decarbonisation visions and the implementation of such visions. To overcome potential paradoxes, there is a need to ensure coordination across scales. Greater Manchester’s overarching decarbonisation vision – to achieve carbon neutrality by 2038 through an innovative, place-based approach – goes some way to ensuring such coordination, albeit there remains a need to overcome fragmentation and approach implementation/multi-scalar implementation more cohesively.

The opportunity exists to build upon the insights presented in this article and to develop further understanding of the relationship between places, visions, and governance through a relational perspective. Within such future research, the interconnections and power dynamics that underpin localised decarbonisation approaches could be identified. As part of this, there would be a need to reflect upon the extent to which formal governance mechanisms, such as those established to support the achievement of Greater Manchester’s decarbonisation vision, could effectively engage individuals, as well as upon the extent to which responsibility is diffused. As a result of such reflections, processes to support the participation of individuals with different contexts, situated at different scales in localised decarbonisation actions, could be identified.

Regarding the implementation of place-based approaches, future research could consider whether it is possible to replicate the processes and mechanisms used to develop place-based approaches in other contexts and the best way of undertaking this. It is likely that the replication of approaches would not occur through the simple translation of processes and mechanisms, but rather by supporting the development of local capabilities and capacities to develop their own place-based approaches.

Notes

1 In this article, ‘subcity’ refers to the 10 local authorities that make up Greater Manchester, the towns within these local authorities, and the communities within the towns.

References

- Akrich, M. 1992. The de-scription of technical objects. Bijker, W. & Law, J. (eds.) Shaping Technology/Building Society. Studies in Sociotechnical Change, 205–224. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Anderson, B.R.O. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Atherton, M. 2019. Mission based approach to delivering the five year environment plan for GM. http://ontheplatform.org.uk/article/mission-based-approach-delivering-five-year-environment-plan-gm (accessed 11 September 2021).

- Atkinson, P. & Coffey, A. 2011. Analysing documentary realities. Silverman, D. (ed.) Qualitative Research, 56–75. 3rd ed. London: SAGE.

- Becker, S., Moss, T. & Naumann, M. 2016a. The importance of space: Towards a socio-material and political geography of energy transitions: Gailing, L. & Moss, T. (eds.) Conceptualizing Germany’s Energy Transition: Institutions, Materiality, Power, Space, 93–108. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50593-4_6

- Becker, S., Beveridge, R. & Röhring, A. 2016b. Energy transitions and institutional change: Between structure and agency: Gailing, L. & Moss, T. (eds.) Conceptualizing Germany’s Energy Transition: Institutions, Materiality, Power, Space, 21–41. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50593-4_3

- Bellinson, R. & Smith, R. 2021. Implementing missions: Learnings from Greater Manchester. https://medium.com/iipp-blog/implementing-missions-learnings-from-greater-manchester-87aac5fd03be (accessed 4 June 2022).

- Bellinson, R., McPherson, M., Wainwright, D. & Kattal, R. 2021. Practice-Based Learning in Cities for Climate Action: A Case Study of Mission-Oriented Innovation in Greater Manchester. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/sites/public-purpose/files/pr2021-03_a_case_study_of_mission-oriented_innovation_in_greater_manchester_final_edited_28_may.pdf (accessed 12 April 2023).

- Betsill, M.M. & Bulkeley, H. 2006. Cities and the multilevel governance of global climate change. Global Governance 12, 141–159.

- Bouzarovski, S. & Haarstad, H. 2019. Rescaling low-carbon transformations: Towards a relational ontology. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 44, 256–269.

- Bowen, G.A. 2009. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal 9, 27–40.

- Bridge, G. 2018. The map is not the territory: A sympathetic critique of energy research’s spatial turn. Energy Research & Social Science 36, 11–20.

- Bulkeley, H. & Betsill, M. 2005. Rethinking sustainable cities: Multilevel governance and the ‘urban’ politics of climate change. Environmental Politics 14, 42–63.

- Bulkeley, H., Castán Broto, V. & Maassen, A. 2010. Governing urban low carbon transitions: Bulkeley, H., Broto, V.C., Hodson M. & Marvin, S. (eds.) Cities and Low Carbon Transitions, 29–41. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bulkeley, H., Castán Broto, V. & Maassen, A. 2014. Low-carbon transitions and the reconfiguration of urban infrastructure. Urban Studies 51, 1471–1486.

- Burke, M.J. & Stephens, J.C. 2018. Political power and renewable energy futures: A critical review. Energy Research & Social Science 35, 78–93.

- Cantoni, R. & Rignall, K. 2019. Kingdom of the sun: A critical, multiscalar analysis of Morocco’s solar energy strategy. Energy Research & Social Science 51, 20–31.

- Castán Broto, V. & Bulkeley, H. 2013. Maintaining climate change experiments: Urban political ecology and the everyday reconfiguration of urban infrastructure. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37, 1934–1948.

- Castree, N. 2003. Place: Connections and boundaries in an interdependent world. Holloway, S.L., Rice, S.P. & Valentine, G. (eds.) Key Concepts in Geography, 165–185. London: SAGE.

- Cervas, S. & Giancatarino, A. 2017. Energy democracy through local energy equity: Fairchild, D. & Weinrub, A. (eds.) Energy Democracy: Advancing Equity in Clean Energy Solutions, 57–75. Washington, DC: Island Press/Center for Resource Economics. https://doi.org/10.5822/978-1-61091-852-7_4

- Coenen, L., Hansen, T., Glasmeier, A. & Hassink, R. 2021. Regional foundations of energy transitions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 14, 219–233.

- Coutard, O. & Rutherford, J. 2010. Energy transition and city–region planning: Understanding the spatial politics of systemic change. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 22, 711–727.

- Cowell, R., Ellis, G., Sherry-Brennan, F., Strachan, P.A. & Toke, D. 2017. Rescaling the governance of renewable energy: Lessons from the UK devolution experience. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 19(5), 480–502.

- Crowther, A., Petrova, S. & Evans, J. 2021. Toward regional low-carbon energy transitions in England: A relational perspective. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2021.635970

- Cugurullo, F. 2018. Exposing smart cities and eco-cities: Frankenstein urbanism and the sustainability challenges of the experimental city. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 50, 73–92.

- Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. 2021. Sub-regional fuel poverty data 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/sub-regional-fuel-poverty-data-2021 (accessed 3 October 2022).

- Department for Transport. 2022. Taking Charge: The Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Strategy. London: HM Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-electric-vehicle-infrastructure-strategy (accessed 12 April 2023).

- Energy Innovation Agency. 2023a. Services. https://www.energyinnovationagency.co.uk/services/ (accessed 28 April 2023).

- Energy Innovation Agency. 2023b. Partners. https://www.energyinnovationagency.co.uk/partners/ (accessed 28 April 2023).

- Felt, U. 2015. Keeping technologies out: Sociotechnical imaginaries and the formation of Austria’s technopolitical identity. Jasanoff, S. & Kim, S.-H. (eds.) Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power, 103–125. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- García-Sánchez, I.-M. & Prado Lorenzo, J.-M. 2009. Decisive factors in the creation and execution of municipal action plans in the field of sustainable development in the European Union. Journal of Cleaner Production 17, 1039–1051.

- GMCA. 2021. Places for Everyone: Joint Development Plan Document – Bolton, Bury, Manchester, Oldham, Rochdale, Salford, Tameside, Trafford, Wigan. https://www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/media/4838/places-for-everyone.pdf (accessed 18 May 2023).

- Golafshani, N. 2003. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report 8, 597–607.

- Grandin, J. & Sareen, S. 2020. What sticks? Ephemerality, permanence and local transition pathways. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 36, 72–82.

- Greater Manchester Combined Authority. 2021. About us. https://gmgreencity.com/about-us/ (accessed 28 April 2023).

- Greater Manchester Combined Authority. n.d. 5-Year Environment Plan for Greater Manchester: 2019–2024. https://www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/media/1986/5-year-plan-branded_3.pdf (accessed 12 April 2023).

- Gudde, P., Oakes, J., Cochrane, P., Caldwell, N. & Bury, N. 2021. The role of UK local government in delivering on net zero carbon commitments: You’ve declared a climate emergency, so what’s the plan? Energy Policy 154: Article 112245.

- Hacker, J., vom Brocke, J., Handali, J., Otto, M. & Schneider, J. 2020. Virtually in this together – how web-conferencing systems enabled a new virtual togetherness during the COVID-19 crisis. European Journal of Information Systems 29, 563–584.

- Hansen, T. & Coenen, L. 2015. The geography of sustainability transitions: Review, synthesis and reflections on an emergent research field. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 17, 92–109.

- Hart, G.P. 2002. Disabling Globalization: Places of Power in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Oakland. CA: University of California Press.

- Hommels, A. 2005. Studying obduracy in the city: Toward a productive fusion between technology studies and urban studies. Science, Technology, & Human Values 30, 323–351.

- Howitt, R. 1998. Scale as relation: Musical metaphors of geographical scale. Area 30, 49–58.

- Hunt, L.C. & Milne, S. 2013. The UK Energy System in 2050: Centralised or Localised? Guildford: Surrey Energy Economics Centre, University of Surrey.

- Jasanoff, S. 2015. Future imperfect: Science, technology, and the imaginations of modernity. Jasanoff, S. & Kim, S.-H. (eds.) Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power, 1–33. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Karvonen, A. 2020. Urban techno-politics: Knowing, governing, and imagining the city. Science as Culture 29, 417–424.

- Krouwel, M., Jolly, K. & Greenfield, S. 2019. Comparing Skype (video calling) and in-person qualitative interview modes in a study of people with irritable bowel syndrome – an exploratory comparative analysis. BMC Medical Research Methodology 19: Article 219.

- Leitner, H., Sheppard, E. & Sziarto, K.M. 2008. The spatialities of contentious politics. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 33, 157–172.

- Li, Y. & Lin, G.C. 2022. The making of low-carbon urbanism: Climate change, discursive strategy, and rhetorical decarbonization in Chinese cities. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 40(6), 1326–1345.

- Manchester City Council. 2023a. The Manchester bee. https://www.manchester.gov.uk/info/100004/the_council_and_democracy/7580/the_manchester_bee (accessed 12 April 2023).

- Manchester City Council. 2023b. Zero carbon Manchester. https://www.manchester.gov.uk/info/500002/council_policies_and_strategies/3833/zero_carbon_manchester (accessed 12 April 2023).

- Massey, D. 2005. For Space. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAWE.

- McCormick, K., Anderberg, S., Coenen, L. & Neij, L. 2013. Advancing sustainable urban transformation. Journal of Cleaner Production 50, 1–11.

- McFarlane, C. 2011. The city as assemblage: Dwelling and urban space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29, 649–671.

- McGinnis, M.D. 2011. Costs and challenges of polycentric governance. https://mcginnis.pages.iu.edu/core.pdf (accessed 4 May 2023).

- Meadowcroft, J. 2005. Environmental political economy, technological transitions and the state. New Political Economy 10, 479–498.

- Meadowcroft, J. 2009. What about the politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long term energy transitions. Policy Sciences 42, 323–340.

- Murray Li, T. 2007. Practices of assemblage and community forest management. Economy and Society 36, 263–293.

- OECD. 2008. Competitive cities in a changing climate: An issues paper. Elliott, V.C. (ed.) Competitive Cities and Climate Change, OECD Conference Proceedings, Milan, Italy, 9–10 October 2008, 48–77. https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/50594939.pdf (accessed 18 May 2025).

- Office for National Statistics. 2020. Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland (accessed 3 October 2022).

- Office for National Statistics. 2021. Mapping income deprivation at a local authority level. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/datasets/mappingincomedeprivationatalocalauthoritylevel (accessed 3 October 2022).

- Owen, S. 2019. SSH Phase 2. D40: Whole System Smart Energy Plan – Greater Manchester. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy & Greater Manchester Combine Authority, GMCA. https://es.catapult.org.uk/report/smart-energy-plan-greater-manchester-combined-authority/ (accessed 4 May 2023).

- Palinkas, L.A., Horwitz, S.M., Green, C.A., Wisdom, J.P., Duan, N. & Hoagwood, K. 2015. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 42, 533–544.

- Pike, A., Rodriguez-Pose, A. & Tomaney, J. 2016. Local and Regional Development. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Raven, P.G. & Stripple, J. 2021. Touring the carbon ruins: Towards an ethics of speculative decarbonisation. Global Discourse 11, 221–240.

- Rice, J.L. 2014. An urban political ecology of climate change governance. Geographical Compass 8, 381–394.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. & Wilkie, C. 2017. Revamping local and regional development through place-based strategies. Cityscape 19, 151–170.

- Roelich, K. 2018. The importance of place in energy system 4.0. Lloyd, H. (ed.) A Distributed Energy Future for the UK: An Essay Collection, 27–29. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

- Rutherford, J. & Coutard, O. 2014. Urban energy transitions: Places, processes and politics of socio-technical change. Urban Studies 51, 1353–1377.

- Sadowski, J. & Levenda, A.M. 2020. The anti-politics of smart energy regimes. Political Geography 81: Article 102202.

- Saldaña, J. 2011. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sassen, S. 2010. Cities are at the center of our environmental future. S.A.P.I.E.N.S 2(3) (2009). https://journals.openedition.org/sapiens/948 (accessed 12 April 2023).

- Smith, A. 2007. Emerging in between: The multi-level governance of renewable energy in the English regions. Energy Policy 35, 6266–6280.

- Smith, J. & Firth, J. 2011. Qualitative data analysis: The framework approach. Nurse Researcher 18, 52–62.

- Späth, P. & Rohracher, H. 2010. ‘Energy regions’: The transformative power of regional discourses on socio-technical futures. Research 39, 449–458.

- Timmermans, S. & Tavory, I. 2012. Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory 30, 167–186.

- Walters, B., Line, J. & Leach, R. 2022. Greater Manchester Local Area Energy Planning: Overview & Insight. Version 0.4. Client review. https://gmgreencity.com/resource_library/greater-manchester-local-area-energy-planning-overview-and-insight/ (accessed 12 April 2023).