Abstract

The urban way of life is considered to be a major milestone in human development. It has attracted unparalleled research interest, breaking boundaries between time and space and between modern academic disciplines. The 150-year-long history of this research in archaeology has witnessed shifting paradigms and has coped with ever-growing new evidence, so that it can substantiate the claim that diversity is what underpins the urban phenomenon worldwide. This long history, however, has also resulted in deeply rooted pre-conceptions of the characteristics of ‘urban’ and the replication of outdated constructs which assess new evidence as ‘wrong time, wrong place’. This article offers the views of a novice, unrestrained by top-down approaches and equally interested in the local origins of cities, as well as the global variability of what makes people dwell in that way. It is inspired by anomalously large sites dated to the 4th millennium bc – the so-called Trypillia mega-sites, in modern Ukraine. The inconsistent engagement with archaeological theory of current urban studies hinders the analysis of these sites within this framework and cannot provide a definitive answer to the question: ‘were these sites urban or not?’ The alternative suggested here is a discussion around four major issues, whose development would move the urban debate on significantly.

INTRODUCTION

Michael Mann (Citation1986) once famously said that there were two types of historians: parachutists and truffle-hunters. Given that ‘cities’ have been an academic topic for 150 years (Fustel de Coulanges Citation1864), one may be forgiven for assuming that parachuting into the field of urban studies in 2012 would have provided a robust, if sometimes controversial, framework within which to assess any new evidence from around the world. Such an assumption could not have been more unjustified. Three field seasons and thousands of learned pages later, I still cannot answer the question ‘Was the 236 ha fourth millennium bc Trypillia site of Nebelivka in the Ukraine urban or not?’ Adhering to one set of criteria currently in operation (Fletcher Citation2009), it certainly could qualify as a low-density urban centre. According to another set of criteria, however, it is an over-grown village – an exception that proves the rule (Liverani Citation2013). This is indicative of very strong preconceptions of what urban means. The current perceptions of the urban phenomenon in the past are far from straightforward. Many archaeologists, but particularly European prehistorians, have internalized Gordon Childe’s (Citation1950) view of the ‘urban revolution’ to see the city as a high-density occupation () place that differs from earlier, Neolithic settlements through the presence of his famous 10 criteria (craft specialization, the existence of writing, etc.). Another prevalent view of the city is based upon the well-known and also high-density Classical Greek and Roman towns. Both the Childean and the Classical views rely on an essentially Eurocentric framework whose validity worldwide should not be taken for granted. By contrast, archaeologists actively involved in studying urban formations have gradually reached a common understanding that it is diversity that underpins this global phenomenon and a cross-cultural definition of a ‘city’ is not possible. Thus, the ‘African type of urbanism’, the ‘Chinese type of urbanism’ and ‘low-density urbanism’ are now mainstream concepts in urban studies that are flourishing alongside the well-known Eurasian and Mesoamerican cases. Since European urbanism has the longest research history, it has so far resisted any challenges to its Childean and/or Classical foundations. In the following pages, I seek to explain why I could not provide a definitive answer to the above question. Put simply, it is because the urban concept itself has become unworkable.

Fig. 1. High-density compact occupation at Ur (modified from Woolley and Mallowan Citation1976, pl. 124).

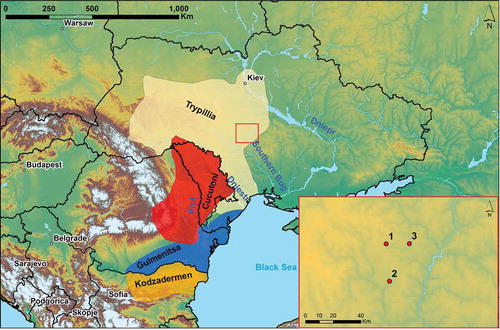

Before we turn to a more detailed discussion of the urban concept, a brief account of the Trypillian mega-sites would be beneficial. Trypillia is a part of the massive Cucuteni-Trypillia network (4800–2800 bc) spread over more than 200,000 km2 in present-day Romania and Ukraine. A couple of centuries into the development of this network, sites much larger than the average 2–3 ha settlements start to appear. The pinnacle of that trend is the appearance of mega-sites (>100 ha) the largest of which is Taljanky with its 320 ha (). The overall number of these mega-sites is disputable but perhaps they form 5% of the currently known Trypillian settlements. The majority of Ukrainian archaeologists consider these sites to be settlement giants (Kruts Citation2012), while a small minority sees them as (proto)urban (Videiko Citation2007). The debate is framed by selective use of Childe’s criteria, one side putting forward the large size and population as evidence for proto-urban development, the other emphasizing the lack of writing and monumental structures as opposing evidence. The urban proponents see Trypillian society as a chiefdom, their opponents underline the lack of craft specialization and well-developed administrative, military and trading functions of these sites. Views about the mega-sites in the Western tradition are very few and far between – they are exceptions to Fletcher’s (Citation1995) global model of settlement growth: towns but not cities (Anthony Citation2010) or part of a chiefdom with a three-tiered settlement hierarchy (Ellis Citation1984). Size was obviously what focused attention as to whether such sites might present an early case of urban organization but the lack of evidence for writing or monumentality makes it easy for critics to dismiss such claims. Moreover, leaving aside this check-list approach (see below), recent investigations have suggested that monumental buildings were part of the mega-sites; what remains unanswered is the social organization creating such sites. Urban or not, they were massive logistical projects requiring a long-term maintenance strategy, proper infra-structure and resource management on a scale hitherto unseen in prehistoric Europe. They are not one-off failed attempts at large agglomeration but a sustained settlement form amid numerous smaller sites. Calling them large villages or exceptions to global rules solves the categorizing problems of modern scholars but does not explain the agency of the people and will not bring us any closer to answering the questions: why did such large settlements appear? How did they function and what was the reason for their decline? Addressing these issues means that we must first return to the very basics of the term ‘urban’ and its current archaeological application.

URBAN AS ANALYTICAL CONSTRUCT

The modern tendency to standardization has all but eliminated emic terms to describe cities. Site differentiation as defined by modern scholars has perhaps very little in common with the site differentiation made by the people in the past or, in other words, how people perceived their own settled world. There are settlement forms for which indigenous names are known (e.g. altepetl: Hirth Citation2008; polis: Finley Citation1981; ilú: Odundiran Citationforthcoming), but these names have been ignored in favour of a higher analytical order, that of the term ‘urban’, to ensure comparability of often very different sets of evidence. Thus, motivations, aspirations and ideals for building and living in such places have been amalgamated to create a ‘higher’, if more abstract, analytical category. There are even more settlement forms whose indigenous names are not known, but which also are called ‘urban’ by modern scholars. So they too, by proxy, will share the characteristics of the ‘urban’ sites known from ethnographic or written sources.

With the exception of studies of the Roman period, ‘urban’ and ‘city’ are used interchangeably and by and large have lost their original meaning (Latin, ‘urbs’ and ‘civitates’). The connotation of ‘urban’ (of a city) coined in the early seventeenth century ad has been transformed from having descriptive qualities to having analytical power. It is no longer just an adjective but a yardstick of human development. Even when it is used as an adjective, it introduces yet another level of conceptual complexity as ‘rural’ makes no sense without ‘urban’ (Cowgill Citation2004, p. 527). Among the numerous zealous discussions about what defines the city, there has never been a challenge to the fundamental premise that ‘urban’ is a modern analytical construct. Willingly or not, urban has become an omnipotent analytical category in this discourse. This is dangerous because it hinders the interchange between higher-level (global) discussions of the meaning of ‘urban’ and case-specific discussions of particular settlements. There is a danger of high-level urban theorists not taking specific cases or emic narratives into account, just as local theorists may draw on a very limited range of higher-level theory (e.g. exemplary traits in check-lists) in their more focused research. So, for example, a very useful debate about processes of urbanization in late prehistoric/early medieval Scandinavia (Skre Citation2008, Anderson Citation2015) will tend to remain a local discussion, with minor contributions to the over-arching analytical category; therefore this debate will have no effect on how emerging cities in 4th-millennium eastern Europe could be approached (see below).

URBAN AS A GLOBAL AND LOCAL CONCEPT

A major problem in urban studies is that there is huge variability in the way that the term ‘urban’ is used, not least in the ‘global’ sense and in the ‘local’ sense. A survey of how the concept of ‘city’ is applied as an analytical concept shows that it tries to accommodate varied settlement evidence from across the globe, while at the same time being robust enough to differentiate between cities and previous settlements (usually Neolithic or, more generally, prehistoric) and between cities and other contemporary settlement forms (towns, villages, etc.). In effect, this means that the ‘urban concept’ operates on two levels – the global and the local. The global promotes diversity but also comparability, so that there should be no doubt in our minds that, although very different, Athens (a Greek polis) (Finley Citation1981), Linzi (a Chinese walled city) (von Falkenhausen Citation2008) and Great Zimbabwe (an African urban centre) (Pikirayi Citation2006) are all cities. The local requires much more rigour in identifying ‘urban’ markers, so that against a uniform background of broadly similar Chalcolithic and Bronze Age tell settlement forms, the ‘urban’ character of a Uruk should stand out (Rothman Citation2001). There is an obvious contradiction concerning how the same concept works at the two levels. Let us look at a hypothetical example. We have two neighbouring sites in a society with written traditions – one has evidence for writing, the other has not. According to the currently accepted view, the site with the evidence for writing is a city, the other is not. So at the local level of a society with writing, this particular variable serves to differentiate between cities and non-cities. But, if we use the same variable at the global level, we see that there are many cases worldwide of cities with no writing. This is usually explained by invoking diversity or resorting to rhetoric about different urban trajectories. In sum, the lack of certain traits at the local level means non-urban, while the lack of the same variable on the global level means diversity. It is not only writing that will not hold up to such scrutiny – the same is true for monumentality, fortification, size and many other criteria.

URBAN IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL THEORY

The viciousness of the debates among culture historians, processualists and post-processualists has not enlivened the field of urban studies. This is not to say that the urban literature is atheoretical or that well-founded critiques and deconstructions are not a common feature there. On the contrary, the intellectual breadth in urban discourse stretches from ancient Greek philosophy (Aristotle) through 20th-century German sociology (Weber) to a modern theoretical physicist (Bettencourt). Yet shifting paradigms in archaeological theory seem to have had little effect on how cities are perceived and studied, with none of the paradigms becoming obsolete. Adapted and reinvented as a neo-evolutionary social approach, Childe’s (Citation1950) culture history framework remains a very powerful construct. Processual notions underpin much of the present understanding of cities (e.g. cities as hubs for goods and services, a basic premise of central-place theory), while post-processualism came unnoticed through the back door and was never actually acknowledged as a valid approach in urban studies. However, its basic principles are traceable not only in what Trigger (Citation2008) calls symbolic and emic approaches but primarily in the embracing of relativist rather than essentialist views of the city. Challenges to the Eurasian pattern of urbanization that question the validity of the predominantly Childean Near-Eastern and Greco-Roman models have arisen from some breathtaking evidence from the Far East, the Americas and Africa.

As a result, the theoretical framework of the urban phenomenon is like the current state of archaeological theory – ‘pick and mix’. This is not the place to discuss in detail the ‘pick-and-mix’ tendency in archaeology; suffice it to say that in archaeological traditions with poor or selective engagement with archaeological theory, this may have serious implications, like allowing free rein to anecdotal claims for towns in the 5th millennium bc in Bulgaria (Nikolov Citation2012). Another result of this state of affairs is that theoretically inspired studies remain fragmentary due to their region- or site- or period-based character, with minimal cross-cultural impact, which is filtered down primarily by those very few equipped to seek common patterns across time and space. Let us illustrate these two points by focusing, first, on pioneering ‘cities’ and then briefly on Scandinavian early medieval towns.

Cities have been classified in various ways – pre-industrial and industrial, functional, whether religious/ceremonial, political and economic or in relation to another much debated social phenomenon, that of the state, where cities are self-standing city-states or part of territorial states or empires. However, one of the most obvious differentiations has been overlooked – that of urban settlements that appeared in an environment that was devoid of similar previous or contemporary dwelling practices as opposed to cities that appeared within a well-established, if punctuated, urban tradition. This may sound surprising, given the massive literature on first cities and the longevity of some debates on the peer-polity model (Renfrew and Cherry Citation1986) or indigenous development vs. external influences (e.g. Indus urbanism, cf. Kenoyer Citation2008). Most of these studies were conducted over a long period of time, in different archaeological traditions and perusing different research questions but ultimately resulting in the production (willingly or not) of a particular concept of ‘the city’. In the last 15 years, more and more archaeologists have been embracing the concept of ‘a city’ (Cowgill Citation2004), underpinned by the diversity thought to characterize the varied evidence from all periods across the globe. However, pioneer urban settlements are still perceived in terms of the ‘city’. I shall illustrate the inadequacy of the current theoretical approach to first cities by considering evidence from the prehistory of Eastern Europe.

PIONEERING CITIES

One of the most quoted definitions of a city is that of M. Smith (Citation2007, p. 4), who stated that ‘urban settlements are centers whose activities and institutions – whether economic, administrative, or religious – affect a larger hinterland’. There is nothing intrinsically urban in this definition. If one changes ‘urban settlements’ to ‘Balkan tells’, there will be many Balkan archaeologists content to adhere to such a definition and substantiating it with evidence for key Balkan tells with influence stretching out through extensive social networks (e.g. Vinča: Chapman Citation1998, Polgár-Csőszhalom: Raczky and Sebők Citation2014).

The inherent danger in essentializing certain characteristics of urban societies as opposed to earlier societies has not escaped the attention of modern scholars. Recently C. Renfrew (Citation2008) has tried to address this basically Childean opposition. While he accepts that Stonehenge was a central place for the Neolithic societies in Britain, the lack of permanent settlement/s and low residential density would not qualify this central place as a city (Renfrew Citation2008, p. 30). Çatalhöyük on the other hand is large enough and densely occupied but the lack of ‘any special buildings representing the separation of functions that one associates with centrality’ (Renfrew Citation2008, p. 31) hampers the interpretation of the site as a city. This is an illustration of the above-mentioned ‘pick and mix’ approach that is inconsistent and based more upon check-lists than social analysis. The ghost of social evolutionary approaches still affects the way that archaeologists perceive and interpret similar but diachronic evidence.

The Neolithic tell of Vinča in Serbia has long been considered a central ancestral place where the community concentrated ritual power and exerted control over exchange networks (Chapman Citation1998). But the place value, ritual power and control at Vinča are somehow not the same as those associated with the early city of Uruk. It is this alleged difference that has haunted me in my quest to understand the emergence of urban sites. Is this difference really there, and, if so, how to define it and even more how to explain it? Like the above case of sites with and without writing, the informed reader might advise looking at the bigger picture for ‘commonly recognized’ traits – like surplus accumulation or craft specialization – as true indicators of urban life. But there are many examples of both in Balkan prehistory, most prominently the Varna cemetery in Bulgaria with its unprecedented concentration of gold in the mid-5th millennium bc or the elaborate painted wares of the Cucuteni-Trypillia group of Romania and Ukraine in the 5th–3rd millennium bc. Sooner or later, we shall arrive at the same point where critics will see such accumulations or masterly production as different from their counterparts in ‘truly urban sites’. However, if such qualitative indicators were missing from urban sites, this would be proclaimed as diversity. Such circular arguments are not going to solve the deeply embedded prejudices towards complex sites preceding urban developments. Solid theoretical and methodological advances are needed to address the evidence at the threshold of urban development.

EARLY MEDIEVAL SCANDINAVIA

Moving to the second example – early medieval Scandinavian towns – I am interested in the recent theorization and wider impact of a fairly localized phenomenon. The discourse revolves around what defines the 7th–10th-century ad urban sites (see references in Urbańczyk Citation2008, Skre Citation2008), the creation of (evolutionary) check-lists (Urbańczyk Citation2008, p. 189) and counter-(timeless)-check-lists (Skre Citation2008, p. 196), contesting the analytical validity of the high medieval town as an analogy for towns of the Dark Ages (ibid.) and arguing for greater continuity between late prehistoric and early medieval settlement form (Anderson Citation2015). The discussion is internally consistent for the region and period in question and, although there is awareness that ‘urban’ is a much wider issue (Skre Citation2008, p. 207, Urbańczyk Citation2008, p. 189), there is no attempt to broaden the debate. The sense of ‘déjà-vu’ triggered by the discussion of the appropriateness of check-lists (as if the whole anti-Childean critique has by-passed this debate) was compensated for by engaging arguments anchored in local sociological and historical studies and invocations of Braudel and Christaller (Anderson Citation2015). This is a very interesting discussion which fails to strengthen its theoretical arguments with reference to the global urban debate.

This is a missed opportunity in the sense of the limited impact of theoretically engaged regional studies. Returning to the pioneering cities, a useful starting point in tackling this issue, one informed from the unlikely source of Scandinavian urbanization, is that urban and pre-urban are much more conceptually linked than modern scholars are ready to admit. A second useful insight is that looking down from a fixed point of the idealized city to an earlier set of evidence is unhelpful. In a nutshell, there is much more common ground between two seemingly unrelated phenomena that a fully operational theoretical framework should be able to pick up. A relational approach to different examples of urban development has great potential to advance the study of ‘urban’. But such potential may be threatened by a lack of source criticism of the data used to make the urban argument.

URBAN AND THE NEW PARADIGM

In a recent article, K. Kristiansen (Citation2014) invites us to celebrate the arrival of big data in archaeological applications rather than bemoaning the death of archaeological theory. Although I wholeheartedly applaud the accumulation of archaeological data on every level, from pottery scatters to global satellite images, I fear that if its use is not adequately theorized, it may bring more harm than good. How to interpret survey data is problematic enough (Whitelaw Citation2013), but now the problem is even more acute with the arrival of big data.

Site-based urban studies remain the dominant mode of investigations of the city. However, it is widely recognized that what gives substance to the city is its immediate surroundings. Regional surveys are not necessarily focused on the development of urbanization, although this is often offered as a by-product, but on more general settlement-pattern dynamics.

The research questions that surveys and gazetteers or large accumulations of a single type of artefact (e.g. pottery) can answer relate to large-scale phenomena and/or long-term traditions. Their large-grain resolution, however, makes them less suitable for concrete questions (see also Whitelaw Citation2013). The emergence and sustainability of a settlement form that has gained the status of analytical category are relevant concrete questions, the answers to which should be extracted not only from the alleged urban place but also from its immediate setting. So if, in a hypothetical 100 sq. km area occupied in a single phase, there are three sites known from county records, five found by intensive field-walking with recorded artefact and feature distributions and one partially excavated site, the sites would contain different information in terms of detail and accuracy. Such an imbalance of information has not stopped numerous reconstructions of rural/urban landscapes and any well-informed archaeologist knows that micro- and macro-level regional studies of sites with equal dataset resolution are simply impossible. While I am all in favour of maximum extraction of information from fragmentary datasets, I strongly disagree with the current practice of gross under-theorization of the evidential basis and the obvious disparity in the precision of the data. An excellent methodological and theoretical example of addressing this issue is the Knossos Urban Landscape Project (Whitelaw Citation2013).

One rare and elegantly theorized example of big data was Fletcher’s (Citation1995) worldwide study of settlement sizes. Based on an extremely rich body of data across time and space, Fletcher identifies three limits of settlement growth beyond which the society involved underwent significant social change. Thus, the first limit of 1–2 ha sees the change from mobile bands to sedentary villages, the second one of 100 ha accommodates the transition from villages to agrarian states, while the third limit of 100 sq. km defines the tipping point to industrial cities. The basic evolutionary premise of this model, together with taking size as its main determinant, constrains its analytical power and leaves some settlement forms, such as the Trypillian sites, as unexplained exceptions to settlement constraints.

The advances and limitations of survey data for population dynamics and settlement patterns are regularly debated (e.g. contributions in Bintliff and Sbonias Citation1999, Nichols Citation2006, Rice Citation2006), but the implications of the very same patterns for the next level of discourse, that of urban–non-urban relations, seem to have been overlooked. The number of sherds is translated into population densities, which in its turn is translated into a settlement classification relying on size to define whether a site is urban or not.

The newly emerging supra-regional datasets (e.g. 10,000 sites within the Fragile Crescent Project in Western Asia alone: personal communication, D. Lawrence) reinforce this unresolved tension, this time on an even bigger scale. Procedures for making sense of big datasets are poorly theorized; ultimately, the size and visibility of pottery scatters exert a strong influence on the definition of a settlement hierarchy. But, turning to site-based investigations, there is a hot debate over whether size, and to lesser degree artefact scatters, can be used as an urban indicator. Thus, there is a double standard and a pronounced inconsistency in studying ‘cities’ or central places and their hinterlands. The larger, more visible and usually long-excavated sites receive a place at the top of the settlement hierarchy, while remote sensing, survey data and the occasional excavation ‘infill the landscape’ with settlements of a different order. If the primacy of certain sites assumed on the basis of written records or long-term excavations is not questioned, regional surveys will comfortably replicate settlement hierarchies defined by size as the primary, if not the only, variable (Altaweel et al. Citation2015). After all, capital cities are not always the largest sites, whether Canberra, Ankara or Brasilia.

DISCUSSION

Despite the numerous stimulating discussions, primarily in general overviews and cross-cultural essay collections, these problems of definitions of ‘urban’ have never been raised quite like this before. This is probably because if one questions the fundamental principles of a working definition, there should be a suitable alternative in place. In my opinion, academic discourse around critical points is the most constructive way to move the debate forward and create alternative understandings. Without forming an exhaustive list, the following four critical points would seem to be essential to re-formulating the urban debate:

1. Recognition or deconstruction of the uncritical acceptance of ‘urban’ as an analytical category, of the inconsistencies in how the ‘urban’ concept is applied on local and global levels, and the double standard applied to site-based and regional-based urban studies. Are we not simply trying to pack too much into one concept?

I see this as a crisis not of definition (‘what is a city?’) but of categories (how to conceptualize the meaning of certain sites in relation to other sites?) and how to zoom in and out between the different scales of analysis without compromising this meaning. Present concepts which are closest to what I mean by categories are rural and urban, even though these concepts are very limiting. Paradoxically, the huge body of archaeological research on rural-urban relationships, much of which is theoretically well-informed, whether seeing a dominance of urban over rural (Schwarz Citation1994, p. 21) or promoting complementarity (Small Citation2006), fails to create a convincing conceptualization of the basic premise of a rural/urban dichotomy nested within a settlement hierarchy of two or more tiers. This is not to say that no societies were ever organized into such a system. Rather, it is to question its omnipotent validity. In that sense, it is regrettable that the concept of ‘heterarchy’ (Crumley Citation1987, King and Porter Citation1994) has somewhat lost its momentum over the last 20 years.

2. Is contextualization the way forward? A lot of energy has been devoted to arguing against the universal content of the city, but not against a universal term. There is no agreement as to what such a term should convey – a concept, a visual association or a shared understanding? We all have very clear pictures in our minds of the meaning of words like ‘tell’, ‘cave’ or ‘midden’. Cities, however, evoke well-rooted preconceptions and modern analogies. The primacy of the English language in the debate and therefore in the classification – hamlet, village, town, city – is also unhelpful and masks possible conceptual differences in settlement forms worldwide.

Replacing one word with another would be equally unhelpful as there is an obvious need for more adequate names for the different categories of sites. One suggestion is to use local terms for the different sites (if known) or explanations (place of…), although that maybe a bit cumbersome. However, if we are interested in the meaning of different sites, calling them by names such as ‘apoikia’ (home away from home: Whitley Citation2001, p. 124) or ‘mbanza’ (large, low-density settlements…evolving as a result of trade, refugee settlement or concentration of power: Kusimba et al. Citation2006, p. 154) is already very helpful.

3. Can we argue for different agencies responsible for the emergence of pioneering cities and cities that appear and function in a realm where people creatively refer to memory, primary knowledge or a recurrent experience of an urban way of life?

A large part of this article is about weak evidential reasoning (for best practice, see Chapman and Wylie Citation2016) for certain (influential) claims, in general, but it is palpable in particular when addressing evidence currently outside the ‘big urban family’ but bearing many markers of pioneering urban settlements. I would argue against the current futile approach to ‘first-time’ (I deliberately avoid the word ‘pristine’) cities – like the Trypillia sites, if they are cities at all – and cities that appear in an established urban tradition. The latter are sustainable settlement forms that produced enough benefits (despite known examples of limited coercion: Millon Citation1981) for the participating settlements (city and hinterland) to secure their social reproduction. Since the former were emerging cities (viz. a settlement form that was hitherto unknown), a detailed knowledge of the surrounding antecedent and contemporary landscapes is crucial in order to identify potential differences that could be transformed into meaningful urban signifiers.

In addition, we need to improve our understanding of mobility and low-density occupation as contributors to a settlement pattern in which these key characteristics are accepted to hold comparable meaning and significance to the meaning and significance of high-density () permanent sites taken to form the ‘norm’ of an urban settlement pattern.

4. There is perhaps little appreciation of the responsibilities incurred by the interpretation of big data (for an exception see Bevan Citation2012). Although there are warnings about the over-reliance on survey data for the relationship between cities and their surroundings (Small Citation2006, p. 328), the excitement about using the full potential of the data prevails. However, there is a tension between the aim to identify the ‘social construction of cities’ (Smith Citation2003) and their hinterlands (Yanushek and Blom Citation2006), on the one hand, and the disparity between the evidential basis of the alleged cities and their surroundings, on the other. While most commentators agree that ‘no single criterion, such as sheer size’ (Cowgill Citation2004) is useful in the definition of a city, it is precisely size (initially based upon sherd counts and then of demographic estimates) that are used in regional surveys to identify settlement hierarchy and ultimately urban centres. I have to share my immediate respect and admiration for the numerous regional surveys worldwide that have enriched our knowledge about settlement dynamics, long-term patterns of contraction and dispersion, changing land-use or resource management (Bintliff and Sbonias Citation1999, Gorenflo Citation2006). I also believe that this is the way forward, but with much more theoretical reflection about what sort of answers such surveys can provide.

However, we also need a much-improved theoretical and methodological basis for understanding and interpreting settlement differences in size, permanence, durability and monumentality and how these differences become settlement categories that I reluctantly continue to refer to as ‘urban’ and ‘non-urban’. I would much prefer these categories be diverse and contextualized, their names to be expressive of their nature and of the factors that link them together into some kind of nodal network, and hence enable modern cross-cultural analyses of their shared, but nonetheless varied, meanings for the people who co-emerged with them.

What are my suggestions concerning these four points? I hope it has become clear that I do not argue for a simple replacement of terms or concepts but, rather, a more nuanced debate which allows the recognition of both local diversity and wider convergences.

1. One of the great advantages of modern science is the awareness that production and transmission of knowledge are socially constructed. Instead of over-emphasizing the rift between ‘past’ and ‘present’ realities, which we can do very little about, it is more fruitful to focus on how to avoid fixed categories, as well as all-encompassing ones. Paradoxically, ‘urban’ has been applied as both. Cowgill (Citation2004, p. 527) has suggested that measurement along multiple properties could be a better conceptual tool to distinguish between ‘urban’ and other type of settlements. I would argue that, although only briefly sketched and certainly lacking the analytical depth of Cartwright and Runhardt’s (Citation2014) assessment of measurement in social sciences, this notion has suffered an undeserved oversight. I have argued elsewhere (Gaydarska Citationforthcoming) that a relational framework within which sites co-emerge will see as ‘urban’ those settlements whose residential centrality is underpinned by high-intensity social practices relative to contemporary and previous sites along a certain variable (‘property’ in Cowgill’s terms) or combinations of variables. It is important to point out that there is no fixed list of variables. I have suggested economic basis, ideology, investment projects, exchange networks, inter-personal relations and social power, conflict, utilization of social space, cultural memory and representation – but this is neither a prescriptive nor an exhaustive list. More importantly, the formulation of variable/s along which intensity should be measured depends on the research question asked. If we are interested in cross-cultural comparison, some variables will be more meaningful than others. Let us go back to writing, which is included together with mnemonics and performance in my suggested variable of cultural memory and representation. On a global level we will see that some societies have opted for writing as a system for administration and transmission of cultural memory, while others preferred different material media and/or performance. In that sense, although certainly very important in terms of demonstrating different material choices for communication, this variable perhaps has less comparative value. On a local level, we will see that certain sites have a high concentration of tablets, mnemonic objects or images, while others have fewer or none, thus heralding some special status for the former. What needs further attention is the development of robust methodology for measurement in archaeology.

2. Moses Finley once said that ‘city-state’ is an English convention in rendering the Greek word polis (Citation1981, p. 4). He then goes to explain why this was necessary as Aristotle used the word interchangeably to denote both ‘city-state’ and ‘town’ (ibid.). Such explanations are very illuminating as to why a certain settlement form has emerged, which ‘an English convention’ (or any other convention, for that matter) will fail to convey. I am a very strong proponent of local names and connotations of settlement sites. As with the polis, they may need conceptual teasing out but such a process is invaluable in revealing human agencies, ideals and motivations. This is not to say that we need to be mired in terminological or semantic discourses but to open up to local variations of what constitutes urban and non-urban. I would argue that the key in explaining the ‘urban’ phenomenon is shared understanding. It will be hard to win such understanding for many prehistoric settlements but the least we can do is not call them villages.

3. Coming to the third point of discussion, before we can start exploring potential different agencies underlying the inception of pioneering and non-pioneering cities, we need to agree that there is such a division. Despite influential calls to do so (Cowgill Citation2004, pp. 534–537), the prevailing view does not concur and sees the pioneering cities as first-order sites in a continuum, usually of evolutionary nature, that culminates in the idealized notion of a city. If offered, theoretical considerations dwell on characteristics positioned anywhere along that continuum with the aim of distinguishing pioneering cities from earlier and contemporary settlement forms. In a way, research interests in pioneering cites are predicated upon their ‘success’ as preferred forms of settlement organization. ‘Booms’ and ‘busts’ have no place in this orderly continuum and the Trypillia mega-sites, being a ‘dead-end’, cannot feature there either. I would argue that Çatalhöyük or Çayönü are not episodes in the ‘long gestation of the true city’ (Gates Citation2011, p. 13), but are very serious manifestations of hitherto novel overlapping social processes, rooted in ancestral values and challenged by daily practices. Mega-sites, and perhaps other type of sites, are such manifestations, too. While the nature of these processes, values and practices may or may not be cross-culturally and historically comparable, the failure to recognize the effects of established frameworks that are experienced ideologically, economically or simply personally will produce some spurious results. Pioneering settlement forms that turned into ‘dead-ends’ and their more successful counterparts that we now call ‘first cities’ are equally important in revealing the initial impetus behind settlements forms that shared many characteristics with previous and contemporary sites, yet were perceived and experienced as different. In my view, this approach differs strongly from the impetus towards the emergence of cities in the established urban tradition.

4. In the discussion of the first point, I have already proposed that the relative framework within which sites co-emerged is more instructive in identifying various categories of sites. I have also underlined the importance of the research questions asked. These two points are particularly pertinent in assessing big data in terms of urban development. A recent study of urbanism in ancient peninsular Italy offers a very sound methodology and series of procedures and decisions that are needed before any reasonable comparison could take place (Sewell and Witcher Citation2015). Following this example, we have to accept that a lot of data will be lost, and some of it not just a mere detail, in pursuit of the gain of greater comparability. That will give a chance to sites with less accurate information and the ‘lost’ data can always be rehabilitated, if the research question is rephrased. Modern technology of various kinds (Bevan Citation2015) can store, process, visualize and even analyse and describe huge amounts of archaeologically relevant data in a way that the human mind is not capable of, but what it cannot do is explain it. Just because the data are big, this does not make them self-explanatory. A future challenge in ‘urban’ archaeology is the development of a robust theoretical framework capable of both explaining patterns stimulated by relevant research questions and absorbing the implications of the loss of data caused either by methodological consideration (as in the above-mentioned case of ancient Italy) or by other factors affecting the comparability of the data (see below).

TRYPILLIA MEGA-SITES

This article began with a question about the ‘urban status’ of the 4th-millennium bc mega-sites of the Trypillia group. How does the discussion of the theoretical issues of urban studies reflect back upon one of my principal current research concerns?

A major empirical difficulty of providing a well-argued answer to the question ‘Are Trypillia mega-sites urban or not?’ is the disparity of the dataset. At first sight, it is extremely rich as it features hundreds of excavated sites (Videiko Citation2004), a detailed pottery typology (e.g. Ryzhov Citation1999, Citation2012), a respectable number of remote sensing plans (e.g. Koshelev Citation2004) and a number of general overviews and interpretations (e.g. Kruts Citation1989, Masson Citation1990, Videiko Citation2007, to mention just a few). The vast majority of this information is sustained by the typical rhetoric of the culture history approach, with artefact types locked in time and space, and social change seen as a result of diffusion, migration or invasion. Re-evaluation of this massive archive is in its infancy (e.g. Diachenko Citation2012, Citation2016), since in Ukraine there is still a very strong suspicion of what elsewhere would be regarded as mainstream practice and theory. Single-context recording, systematic intensive field-walking and test pits are not only not practised but are actively opposed. While each regional archaeological tradition has the right to decide what constitutes best practice, there seems to be little appreciation that there is no easy way of transmitting archaeological information from one tradition to another. Some steps have been made in reconciling the various ways of data acquisition and interpretation (Menotti and Korvin-Piotrovskiy Citation2012, Müller et al. Citation2016) but much more remains to be done if this truly vast archaeological archive is to become comparable beyond the region itself.

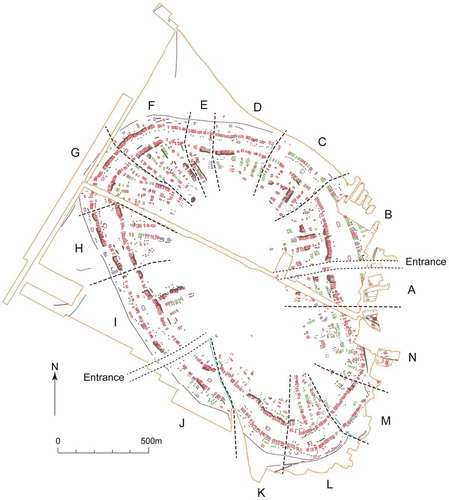

The site of Nebelivka (236 ha) in Kirovograd domain, Ukraine, has some 1500 structures, organized in two concentric circuits and inner radial streets that are currently divided into 14 quarters and over 140 neighbourhoods (). The overall spatial patterning suggests top-down planning but a closer look into individual neighbourhoods, consisting of three to 25 households reveals a high degree of variability. A shallow perimeter ditch with more symbolic than defensive functions and a small stream (now a palaeochannel) seem to have had a significant structuring effect. Twenty-three larger-than-usual houses flanked the outer circuit at 90 degrees in relation to the ‘normal’ house orientation. They are provisionally called ‘Assembly Houses’. Only one Assembly House was part of the inner circuit (Chapman et al. Citation2014). It contained typical domestic features, such as clay platforms, a fired-clay bin and a bench, all of which, however, were much larger or more numerous than those found in a ‘normal’ house. In contrast, the finds from this mega-structure – pottery, tools or animal bones – were not more numerous than in a house assemblage; if anything, they were fewer than expected from a feature of that size, with a set of 21 miniature vessels, many fired clay tokens and a single golden ornament that may be considered as special finds. The AMS dates, obtained from samples from over 80 test-pits spread across the site, are currently modelled with Bayesian statistics, and preliminary results show a period of occupation between 3950 and 3800 cal. bc. The big question we need to answer is: were the dated structures occupied at the same time (Millard et al. Citationforthcoming)? Also somewhat surprising was the outcome from the field survey, suggesting no contemporary settlement in a 5-km radius from the site, with the closest one located 12 km away. It is noteworthy that the partly contemporary 320 ha site of Taljanky is only 18 km away and the slightly later 200 ha site of Maidenetskoe 20 km away ().

Fig. 3. Plan of Nebelivka mega-site with proposed division into quarters. (Source: Archaeological Services Durham University and Y. Beadnell)

Bearing in mind the limitations of using just one case study, let us see how an alternative concept would fit the Nebelivka evidence. The 236-ha site of Nebelivka shows high-intensity social practices in some variables such as investment projects, ideology or cultural memory and representation, while in other variables such as economy or exchange networks it shows little difference from preceding or contemporary sites. It lacks an immediately occupied hinterland and its environmental impact seems to be limited, which raises a series of questions about the residential patterns of its inhabitants. The contemporaneity of the 1500 structures remains to be answered by Bayesian modelling and, if confirmed, that will mean up to 9000–10,000 inhabitants. The site has lasted 100–150 years, so it would appear that social cohesion, successful resource management and developed logistics were responsible for such longevity.

We do not know how the inhabitants referred to Nebelivka, and we call it a ‘mega-site’. This does not mean that mega-sites were the same as the ‘normal’ 2-ha Trypillia sites, only much bigger. It means that life there was experienced in a different way – from the overall planning, through the movement to visit a friend three quarters away, to the collective efforts to gather fuel for large-scale house-burning. These sites were perceived and valued in a different way from earlier and contemporary sites.

The mega-sites appearing late in the Trypillia sequence, such as Taljanky and Majdanetskoe, that also happened to be the largest ones, drew on the experience of earlier sites such as Vesely Kut and Nebelivka. Congregation of large groups of people, whether on a seasonal, a year-round or a cyclical basis became an important part of the habitus of Trypillian communities. The mobilization of substantial amounts of natural and human resources underpinning the creation and sustainability of such sites makes them serious contenders for central places for the (re-)negotiation of social order, for feasting and ceremonies that were inevitably accompanied by regular food and water supply, maintenance activities, economic transactions, refuse disposal and many more daily practices, whose performance on such a large scale required planning and co-ordination of a very different intensity from that required on a much smaller site. In this sense, size seems to have been a factor in defining the mega-sites as a ‘different category of site’, in terms of my alternative suggestion, or as ‘urban’ in terms of the more commonly accepted terminology.

Ukrainian archaeologists are very strong proponents of the consecutive occupation by broadly the same group of people of the three largest mega-sites starting with Nebelivka, followed by Taljanky and finished by Majdanetskoe. Recent AMS dating, however, shows an overlap between the first two sites, thus raising the possibility of competing centres (much more work is needed to study the hinterland of Taljanky) or a less permanent type of occupation that will see the two sites without thousands of occupants at the same time at both sites. The three-tier hierarchy of sites (Ellis Citation1984, Diachenko Citation2012) needs further argumentation, since it is based on site sizes whose recent assessment has been revealed to be rather inaccurate (Nebbia Citationin prep.). A heterarchy at both intra- and inter-site level seems more plausible, although also in need of further support, since no materialization of social difference but only of intensity was documented between the various categories of sites. Furthermore, the idea of V. Kruts (Citation1989, p. 128) that Taljanky may have consisted of 40 smaller social units – the typical representatives of sites up to 10 ha – is echoed by the spatial patterning at Nebelivka, where the tension between small-scale bottom-up planning and the overall top-down settlement design was, for at least some decades, successfully resolved.

In conclusion, Nebelivka, and perhaps the other mega-sites, are not to be viewed somewhere between the village and the city in an evolutionary framework but among diverse settlement forms in a distributed framework of settlement trajectories. These settlement trajectories have peaks and troughs, some settlement forms disappear, others are repeatedly preferred. Large low-density agglomerations with still debatable permanence of dwelling constituted the preferred form, along with many smaller sites, in the 4th millennium bc in the forest-steppe zone in modern Ukraine. The reasons for their emergence and decline are further research avenues currently under exploration.

CONCLUSIONS

My interest in the urban phenomenon was inspired by the little-known Trypillian mega-sites in Ukraine. Ironically, it was their size, ranging from 100 to 320 ha, that provoked their interpretation as possible (proto)cities – an interpretation that I now accept is far from straightforward. The lack of common understanding about the nature of these sites in the Ukraine (Videiko Citation2007, Kruts Citation2012) is mirrored by the lack of a robust analytical framework in current archaeological practice that can adequately address the methodological and theoretical issues posed by these sites. A scrutiny of the evidence from Nebelivka, the third largest Trypillian site currently known, has led to the deconstruction of the ‘urban’ concept. The aspiration for comparability through space and time has led to the adoption of a single word – ‘urban’ or ‘city’ – to convey the complexity of this form of occupation at the expense of more intimate and direct names, known in ethnographic and written sources. The uncritical fusion of ideas and approaches in the face of ever-growing new evidence has resulted in the currently irresolvable tension between local and global applications of the ‘urban’ concept. The resilience of the ‘check-list’ approach, dressed up as social evolution, essentializes ‘the city’ and proliferates types of sites and societies, sandwiched between ‘villages’ and ‘cities’, whether agglomerated sites (Birch Citation2013) or coalescent societies (Kowalewski Citation2006). Equally unhelpful is the relativistic approach of ‘anything goes’. ‘Urban’ has become too inclusive and has lost its meaning – to the extent that one of the leading figures in settlement archaeology has proclaimed that there is no longer any gain in calling your site a ‘city’ (personal communication, R. Fletcher). Any new evidence may add to the variety of known cities but will not move the concept forward.

In a rapidly globalizing world, cities have attracted fresh research interest (Batty Citation2013, Bettencourt Citation2013) that is understandably biased towards contemporary or fairly recent phenomena. The latest generation of scholars has the advantage of viewing the cities through a sequence of cumulatively enriching historical perspectives. Archaeologists have submitted to this tendency, fearing that for a long time the question of the ‘first’ cities obscures the question of sustainability (Smith Citation2003, p. 11). The lumping of pioneering settlement forms with more or less developed urban forms conceals the kind of reflexivity and agency exerted by the first city-dwellers that was so powerful that it allowed them to break free from long-established settlement traditions. It is about time that historical and comparative approaches help re-focus our attention towards collective motivations and individual agencies that transformed earlier settlements into the various settlement forms that we still call ‘urban’.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am much obliged to Patricia McAnany and Alison Wylie for providing valuable insights, comments and advice on an earlier draft. John Chapman has endured a long process of bouncing off ideas, for which I am very grateful. I am grateful to the editors and reviewers of NAR for their constructive comments.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Altaweel, M., Palmisano, A., and Hritz, C., 2015. Evaluating settlement structures in the ancient Near East using spatial interaction entropy maximization. Structure and Dynamics, 8 (1), 1–30.

- Anderson, H., 2015. Urbanization, continuity and discontinuity. In: I. Baug, J. Larsen, and S.S. Mygland, eds. Middle ages – artefacts, landscapes and society. Essays in honour of Ingvild Øye on her 70th birthday. Bergen: University of Bergen, 21–31.

- Anthony, D., 2010. The rise and fall of Old Europe. In: D. Anthony, with J. Chi, eds. The lost world of Old Europe: the Danube valley, 5000–3500 BC. New York: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World and Princeton University Press, 28–57.

- Batty, M., 2013. A theory of city size. Science, 340, 1418–1419. doi:10.1126/science.1239870

- Bettencourt, L., 2013. The origins of scaling in cities. Science, 340, 1438–1441. doi:10.1126/science.1235823

- Bevan, A., 2012. Spatial methods for analysing large-scale artefact inventories. Antiquity, 86 (332), 492–506. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0006289X

- Bevan, A., 2015. The data deluge. Antiquity, 89 (348), 1473–1484. doi:10.15184/aqy.2015.102

- Bintliff, J. and Sbonias, K., ed., 1999. Reconstructing past population trends in Mediterranean Europe. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Birch, J., 2013. From prehistoric villages to cities: settlement aggregation and community transformation. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Cartwright, N. and Runhardt, R., 2014. Measurement. In: N. Cartwright and E. Montuschi, eds. Philosophy of social science: a new introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 265–287.

- Chapman, J., 1998. Objects and places: their value in the past. In: D.W. Bailey, ed. The archaeology of prestige and wealth. International Series 730. Oxford: BAR, 106–130.

- Chapman, J., et al., 2014. An answer to Roland Fletcher’s Conundrum?: preliminary report on the excavation of a Trypillia mega-structure at Nebelivka, Ukraine. Journal of Neolithic Archaeology. 16:135–157. Available from: http://www.jungsteinsite.de/

- Chapman, R. and Wylie, A., 2016. Evidential reasoning in archaeology. London: Bloomsbury.

- Childe, V.G., 1950. The Urban revolution. The Town Planning Review, 21 (1), 3–17. doi:10.3828/tpr.21.1.k853061t614q42qh

- Cowgill, G., 2004. Origins and development of urbanism: archaeological perspectives. Annual Review of Anthropology, 33, 525–549. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.061002.093248

- Crumley, C., 1987. A dialectical critique of hierarchy. In: T. Patterson and C. Gailey, eds. Power relation and state formation. Washington, DC: American Anthropological Association, 155–168.

- Diachenko, A., 2012. Settlement system of West Tripolye culture in the Southern Bug and Dnieper interfluve: formation problems. In: F. Menotti and A.G. Korvin-Piotrovskiy, eds. The Tripolye culture giant-settlements in Ukraine: formation, development and decline. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 116–138.

- Diachenko, A., 2016. Demography reloaded. In: J. Müller, K. Rassmann, and M. Videiko, eds. Trypillia-Megasites and European Prehistory, 4100–3400 BCE. London: Routledge, 181–194.

- Ellis, L., 1984. The Cucuteni-Tripolye culture: a study of technology and origins of complex society. International Series 217. Oxford: BAR.

- Finley, M., 1981. Economy and society in ancient Greece. London: Chatto and Windus.

- Fletcher, R., 1995. The limits of settlement growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fletcher, R., 2009. Low-density, agrarian-based urbanism: a comparative view. Insights, 2 (4), 2–19. Durham University, Institute of Advanced Studies.

- Fustel de Coulanges, N.D., 1864. La cite´ antique. Paris: Librairie Hachette.

- Gates, C., 2011. Ancient cities. London: Routledge.

- Gaydarska, B., Forthcoming. Introduction. In: B. Gaydarska, guest ed. Re-assessing Urbanism in prehistoric Eurasia. Journal of World Prehistory.

- Gorenflo, L.J., 2006. The evolution of regional demography and settlement in the Prehispanic basin of Mexico. In: G. Storey, ed. Urbanism in the preindustrial world. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 295–316.

- Hirth, K., 2008. Incidental urbanism: the structure of the prehispanic city in Central Mexico. In: J. Marcus and J. Sabloff, eds. The ancient city: new perspectives on ancient urbanism. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 273–298.

- Kenoyer, J., 2008. Indus urbanism: new perspectives on its origin and character. In: J. Marcus and J. Sabloff, eds. The ancient city: new perspectives on ancient urbanism. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 185–210.

- King, E. and Porter, D., 1994. Small sites in Prehistoric Maya socioeconomic organization: a perspective from Colha, Belize. In: G. Schwarz and S. Falconer, eds. Archaeological view from the countryside: village communities in early complex societies. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 64–90.

- Koshelev, I., 2004. Pamiatniki tripol’skoi kul’turi po dannim magnitnoi razvedki. Kiev.

- Kowalewski, S., 2006. Coalescent Societies. In: T. Pluckhahn and R. Ethridge, eds. Light on the path: the anthropology and history of the Southeastern Indians. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 94–122.

- Kristiansen, K., 2014. Towards a new paradigm? Current Swedish Archaeology, 22, 11–34.

- Kruts, V., 1989. K istorii naseleniya tripolskoj kultury v mezhdurechye Yuzhnogo Buga i Dnepra (Regarding the history of Tripolye culture population in the Southern Bug and Dnieper interfluve). In: S.S. Berezanskaya, ed. Pervobytnaya Archeologiya: Materialy i Issledovaniya. Kiev: Naukova Dumka, 117–132.

- Kruts, V., 2012. Giant-settlements of Tripolye culture. In: F. Menotti and A.G. Korvin-Piotrovskiy, eds. The Tripolye culture giant-settlements in Ukraine: formation, development and decline. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 70–78.

- Kusimba, C., Kusimba, S., and Agbaje-Williams, B., 2006. Precolonial African cities: size and density. In: G. Storey, ed. Urbanism in the preindustrial world. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 145–160.

- Liverani, M., 2013. Power and citizenship. In: P. Clark, ed. The Oxford handbook of cities in world history. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 164–180.

- Mann, M., 1986. Presentation at TAG conference. Bradford.

- Masson, V., 1990. Tripolskoe obshchestvo i ego sotsialno-ekonomicheskie charakteristiki. In: V.G. Zbenovich, ed. Rannezemledelcheskie Poseleniya-Giganty Tripolskoj Kultury na Ukraine. Tez. Dokl. I Polevogo Seminara. Talianki: Institute of Archaeology of the AS USSR, 8–10.

- Menotti, F. and Korvin-Piotrovskiy, A., eds., 2012. The Tripolye culture giant-settlements in Ukraine: formation, development and decline. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Millard, A., et al., Forthcoming. Dating Nebelivka: too many houses, too little time. To appear in project monograph.

- Millon, R., 1981. Teotihuucan: city, state and civilization. In: J. Sabloff, ed. Handbook of middle American Indians, Vol. 1, archaeology, supplement. Austin: University of Texas Press, 198–243.

- Müller, J., Rassmann, K., and Videiko, M., eds., 2016. Trypillia-Megasites and European prehistory, 4100–3400 BCE. London: Routledge.

- Nebbia, M., in prep. Early cities or mega-villages? Settlements dynamics in the Trypillia culture. Thesis (PhD). Durham University, UK.

- Nichols, D., 2006. Shining stars and black holes: population and preindustrial cities. In: G. Storey, ed. Urbanism in the preindustrial world. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 330–340.

- Nikolov, V., 2012. Salt, early complex society, urbanization: Provadia-Solnitsata (5500–4200 BC). In: V. Nikolov and K. Bacvarov, eds. Salt and gold: the role of salt in prehistoric Europe. Faber: Provadia-Veliko Tarnovo, 11–65.

- Odundiran, A., Forthcoming. The house of Ife in regional context: sociopolitical complexity in Yorubaland, ca.1000–1500. In: M. Davies and K. MacDonald, eds. Connections, contributions and complexity: Africa’s Later Holocene archaeology in global perspective. Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs.

- Pikirayi, I., 2006. The demise of Great Zimbabwe, AD 1420–1550: an environmental re-appraisal. In: A. Green and R. Leech, eds. Cities in the world, 1500–2000. Leeds: Maney Publishing, 31–47.

- Raczky, P. and Sebők, K., 2014. The outset of Polgár-Csőszalom tell and the archaeological context of a special central building. In: Arheovest II: in honorem Gheorge Lazarovici. Szeged: Jate Press Kiadó, 51–100.

- Renfrew, C., 2008. The city through time and space: transformations of centrality. In: J. Marcus and J. Sabloff, eds. The ancient city: new perspectives on ancient urbanism. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 29–52.

- Renfrew, C. and Cherry, J., 1986. Peer polity interaction and socio-political change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rice, D., 2006. Late Classic Maya population: characteristics and implications. In: G. Storey, eds. Urbanism in the preindustrial world. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 252–276.

- Rothman, M., ed., 2001. Uruk Mesopotamia and its neighbors: cross-cultural interactions in the era of state formation. Santa Fe: School of Advanced Research.

- Ryzhov, S., 1999. Keramika Poselen Trypilskoi Kultury Bugo-Dniprovskogo Mezhyruzhzhia yak Istorychne Dzerelo. Thesis (PhD). Institute of Archaeology of the NAS of Ukraine, Kyiv.

- Ryzhov, S., 2012. Relative chronology of the giant-settlement period BII – CI. In: F. Menotti and A. Korvin-Piotrovskiy, eds. The Tripolye culture giant-settlements in Ukraine: formation, development and decline. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 79–115.

- Schwarz, G., 1994. Rural economic specialization and early urbanization in the Khabur valley, Syria. In: G. Schwarz and S. Falconer, eds. Archaeological view from the countryside: village communities in early complex societies. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 19–36.

- Sewell, J. and Witcher, R., 2015. Urbanism in ancient peninsular Italy: developing a methodology for a database analysis of higher order settlements (350 BCE to 300 CE). Internet Archaeology, 40. doi:10.11141/ia.40.2

- Skre, D., 2008. Dark Age towns: the Kaupang case. Reply to Przemysław Urbańczyk. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 41 (2), 194–212.

- Small, D., 2006. Factoring the countryside into urban populations. In: G. Storey, ed. Urbanism in the preindustrial world. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 317–329.

- Smith, M., ed., 2003. The social construction of ancient cities. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Smith, M., 2007. Form and meaning in the earliest cities: a new approach to ancient urban planning. Journal of Planning History, 6, 3–47. doi:10.1177/1538513206293713

- Trigger, B., 2008. Early cities: craft workers, kings, and controlling the supernatural. In: J. Marcus and J. Sabloff, eds. The ancient city: new perspectives on ancient urbanism. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 53–66.

- Urbańczyk, P., 2008. What was ‘Kaupang in Skiringssal’? Comments on Dagfinn Skre (ed.) Kaupang in Skiringssal. Kaupang Excavation Project Publication Series, Vol. 1. Århus University Press, Århus. (2007). Norwegian Archaeological Review, 41 (2), 176–194. doi:10.1080/00293650802516995

- Videiko, M., 2004. Encyclopaedia Tripil’s’koi cyvilizacii. Vol. 1. Kyiv: Ukrpoligrafmedia.

- Videiko, M., 2007. Contours and contents of the ghost: Trypillia culture proto-cities. Memoria Antiquitatis, 24, 239–250.

- von Falkenhausen, L., 2008. Stages in the development of ‘cities’ in pre-imperial China. In: J. Marcus and J. Sabloff, eds. The ancient city: new perspectives on ancient urbanism. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 209–228.

- Whitelaw, T., 2013. Collecting cities: some problems and prospects. In: P. Johnson and M. Millett, eds. Archaeological survey and the city. Oxford: Oxbow books, 70–106.

- Whitley, J., 2001. The archaeology of ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Woolley, L. and Mallowan, M., 1976. Ur excavations. Vol. 7, The Old Babylonian period. London: British Museum Publications.

- Yanushek, J. and Blom, D., 2006. Identifying Tiwanaku urban populations: style, identity and ceremony in Andean cities. In: G. Storey, ed. Urbanism in the preindustrial world. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 233–251.