Abstract

In this paper, we explore the social context of rock art creation through the lens of one woman’s childhood experiences in, what is now, Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory of Australia. We reflect upon oral history interviews conducted over the last three years with Warrdjak Senior Traditional Owner Josie Gumbuwa Maralngurra and her childhood spent walking country with family. As a witness to vast numbers of rock paintings being created, and sometimes an active participant in that process, Josie’s memories provide rare insights into the social and cultural context of rock art practices during the late 1950s and early 1960s. We argue that Josie’s personal experiences provide solid evidence for both the educational role that rock art continued to play across the region during the 20th century and its role as a tool for helping to ensure intergenerational connection to country.

INTRODUCTION

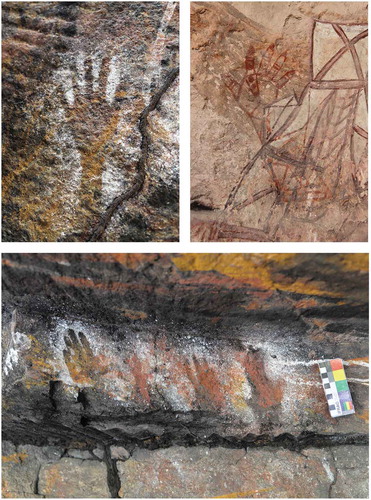

Rock art is often appreciated as a unique global archive of human creativity and cognition (McDonald and Veth Citation2012, David and McNiven Citation2018), but how can we use this media to discuss the role of children in the past? In contrast to other material culture that archaeologists use for this pursuit (e.g., Sofaer Citation2000, Baxter Citation2005, Coskunsu Citation2015, Derricourt Citation2018), rock art has the advantage that it presents an exceptional direct visual testimony and source of inspiration to discuss childhood. Children’s presence is most obviously indicated in rock art through the variation in the size of depicted anthropomorphic figures (e.g., Hays-Gilpin Citation2004, Citation2012, Goldhahn and Fuglestvedt Citation2012, cf. ). While we ponder on who made these artworks, their meanings, when and why, it is evident that some of these practices required children’s direct physical – embodied – participation, engaging them with pigments and rocks, in creating what we know as stencils and prints of different body parts (). The presence of children is then revealed through the variation in size of depicted hands, arms, and fingers (e.g., Clottes et al. Citation1997, Gunn Citation2006, Snow Citation2006, Bednarik Citation2008, Mackie Citation2015). The same goes for foot motifs (e.g., Fossati Citation1997, Goldhahn Citation2008, p. 110, Citation2012, Arcà Citation2015). Children are also possible to identify by reviewing the variation in the size of so-called finger flutings in caves in different parts of the world (van Gelder Citation2015a, Citation2015b). Even more intriguing, preserved footmarks on cave floors bear witness to the presence of children in secluded esoteric contexts where artworks were created and unfolded people’s life-worlds in Palaeolithic caves such as Niaux in southern France (Clottes Citation1995, cf. Bahn Citation2012, Cooney-Williams and Janik Citation2018).

Fig. 1. Hand Stencils from Kurrih (top left and below) and a Painted Hand from Nanguluwurr (top right), situated within today’s Kakadu National Park, indicating the presence of children through their size. All these hand figures belong to Josie Maralngurra and were created by her father Old Nym Djimongurr in the late 1950s and early 1960s (see main text for details). Photographs by Joakim Goldhahn (below), Andrea Jalandoni (top left), 2018, and by Paul Taçon (top right), 2019.

While it is easy to demonstrate a growing number of publications relating to the importance of children in our interpretation of the past generally (e.g., Lillehammer Citation1989, Citation2015, Moore and Scott Citation1997, Baxter Citation2005, Thompson et al. Citation2014, Coskunsu Citation2015, Cunnar and Höberg Citation2015, Gärdenfors and Högberg Citation2017, Crawford et al. Citation2018, Langley and Litster Citation2018, Högberg Citation2018), there have been few rock art studies which try to move beyond the complex task of demonstrating the presence of children to explore their roles in social and cultural life. Most such studies have relied on the depicted subject matter and formal analyses, e.g., an etic perspective. While such studies are vital in themselves, they seem to suggest that there exists a clear set of rock art that relates to children, while other parts of the assemblages do not. In short: if children or body parts of children are not depicted it follows that the created artworks were made by and for adults. The absence of evidence then becomes evidence of absence.

This seems to be a general problem within archaeological analyses of children in the past. Langley and Litster (Citation2018) examine this in some length in a recent article by discussing the interpretation of material culture among hunters and gatherers. They ask: ‘Is it ritual? Or is it children?’ (Langley and Litster Citation2018). They provide ample examples of ‘children’s toys’ from anthropological case studies, and show how similar material culture has been interpreted differently in archaeological contexts, and in many cases by adding ‘ritual’ and stirring. They conclude their analysis by stating that:

… we hope to have demonstrated not only that children can and should have produced a much wider range of archaeological residues but also the importance of differentiating between these residues and those resulting from adult ritual behaviors. Importantly, this point is not made simply to further cast children as a distorting effect on the archaeological record that must be drawn out but instead to prompt conscious attempts to identify whether an artifact or feature was the result of one or the other. Such analysis will result in archaeologists not only being able to more clearly study adult ritual actions in the deep past but also fueling the development of prehistoric childhood studies (Langley and Litster Citation2018, p. 630–631).

The idea of adult rituals versus children’s play being better identified and separated by proper analysis of material culture downplays a key issue – that kids often have an active role in so-called ‘adult rituals’. In Aboriginal Australia, for example, children were often an integrated part of rituals and ceremonial cycles. The journey from child to adult could involve participation in up to 20 ceremonial cycles, each constituted by one or several rituals, and each of these could go on for months (e.g., Engelhart Citation1998, see Berndt and Berndt Citation1970, Hamilton Citation1980, Morphy Citation1991, Taylor Citation1996, Bell Citation2002, Kaberry Citation2004, Beherndt Citation2005). To become fully initiated could take up to 30 years or longer (Engelhart Citation1998, p. 111).

A chief reason for the implicit urge to contrast children against adults, and play against ritual, seems to be grounded in modernistic distinctions and a worldview resting on naturalism (see Thomas Citation2004, Descola Citation2013, Goldhahn Citation2019a, Citation2019b), where archaeologists either seem to overestimate or underestimate the meaning and significance of material culture. As Langley and Litster (Citation2018) so clearly articulate, similar, or even identical material culture could be used in a range of so-called ‘ritual’ and ‘profane’ contexts. There is no easy way to distinguish one from the other as this-worldly experiences of everyday practices and ritual and ceremonial life-worlds constitute each other (e.g., Durkheim Citation1912, see Bell Citation1992, Bradley Citation2005). Instead of opposing one to the other – ritual vs play, adult vs children – we suggest embracing a continuum of social practices that relate to and reinforce each other. Any advocate for either interpretation should consider the alternative because the same material culture can be ritualized or de-ritualized (Miller Citation1985), and change meaning according to social and cultural contexts (Berggren and Nilsson Stutz Citation2010).

The relation between children and rock art rests on a similar modern preconception. Most analyses seem to be conducted to identify children through archaeological ‘etic,’ ‘chorological’ or ‘formal’ analyses of an assemblage (e.g., Malmer Citation1981, Chippindale and Taçon Citation1998, Whitley Citation2005). In this article, we want to challenge similar studies by presenting a single case study of a young girl’s experience growing up in a painted landscape with rock art as a part of her everyday life. We will present four painting episodes from the late 1950s and early 1960s from three rock art sites in Kakadu National Park (henceforth, Kakadu) in northern Australia (). This case study originates from formal and informal interviews and oral history conducted during our ongoing research project with Djok Senior Traditional Owner Jeffery Lee and, in this case, his kinship classificatory Warrdjak sister Josie Gumbuwa Maralngurra. These conversations were recorded in various ways, e.g., in our field diaries, as digital sound files, as well as photographs and video recordings. When necessary, these conversations have been translated and/or transcribed by local community members.

GROWING UP

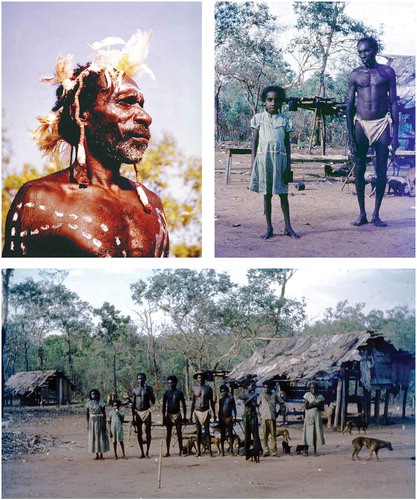

Our story’s lead character is Josie Gumbuwa Maralngurra (skin name Naglbangardi, ). Josie was born in 1952 in the ‘bush’ while her father was shooting water buffalos for Allan White at Malabanjbanjdju, not far from the current Djirrbiyuk outstation in, what is now, Kakadu (May et al. Citation2019, ). Josie’s father, Old Nym Djimongurr (c. 1910–1969), was a Warrdjak man (Nangarridj skin group) from central Arnhem Land (). He moved west into the Kakadu region during the 1930s looking for work. Djimongurr was recorded as having three wives Daisy (b. 1922), Jessie (b. 1917), and Molly Madjabunu (b. 1915) (The Native Affairs Branch Patrol Officers Reports 1950–1952). Josie’s mother was Djimongurr’s third wife, Molly (Ngalwakadj skin group, Jawoyn clan). Together, Molly and Djimongurr also had a son Namandali (c. 1936/1940-1969, Nabangardi skin group) who was significantly older than his younger sister Josie. He was also known by the name – Young Nym and ‘Wildeman’ (Native Affairs Branch Patrol Officers Reports 1950–1952). During the 1950s, Josie and her family would sometimes stay at Russ Jones’ Arnhem Land Timber Camp (Northern Territory Gazette May 13, 1957, p. 112, see also Levitus Citation1995, May and Blair Citation2012), known locally as Manlarrh. Here, her father was cutting timber in the dry season and working as a baker. Molly worked in the kitchen as a cook.

Fig. 3. Josie Gumbuwa Maralngurra at the Nanguluwurr rock art site, Kakadu. In the background a turtle and barramundi painted by her father Djimongurr in 1964. Photograph by Iain Johnston, 2019.

Fig. 4. Photographs of Old Nym Djimongurr and his daughter Josie. Photographs from Judy Optiz Collection c. 1960 and a 1963 photograph of Nym (top left) by Valerie Lhuedé (Citation2012), published with their kind permission. Below, Josie is standing between her mother and father, her brother Namandali standing next to Djimongurr. Nayombolmi is standing in the middle, wearing a hat. Jeffrey Lee’s grandmother is standing on the far right.

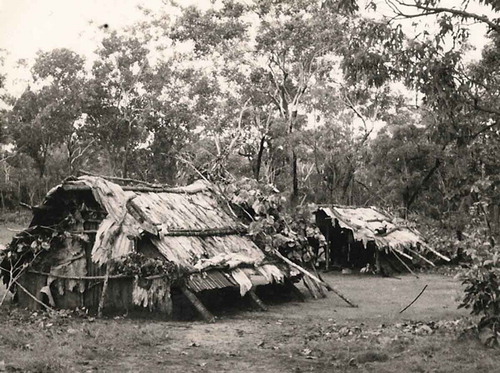

When staying at Manlarrh, Josie’s family and other kin would build traditional stringy-bark huts for shelter (). These bark huts were normally used during the wet season, from about November to April, in areas that did not offer comfortable rock shelters or caves for protection from rain and storms. She recalls that many of these huts were painted with imagery similar to rock paintings (see also Carrington Citation1890, p. 73, Worsnop Citation1897, p. 37, Jelinek Citation1989, Ryan Citation1990, p. 1, Taylor Citation1996, p. 15–17, Taçon and Davies Citation2004, May 2006, Wesley et al. Citation2018). One of Josie’s closest kin throughout her youth was the famous rock art artist Nayombolmi (1895–1967, see Haskovec and Sullivan Citation1986, Citation1989, May et al. Citation2019), who is also known by the name Barramundi Charlie (see ). He also worked seasonally at Jones’ timber mill (Levitus Citation2011). Nayombolmi was born and lived his life in the Kakadu area. He remembered his father and uncle decorating their stringybark huts (and rock shelters) with traditional motifs when he was growing up (Bennett Citation1969, p. 20–22). He continued this tradition well into the 1950s (Goon Citation1996, p. 25), if not longer (cf. Bennett Citation1969, p. 18–19, see also Jelínek Citation1979, Citation1989). Today we know of more than 650 rock paintings created by Nayombolmi (Haskovec and Sullivan Citation1986, Citation1989, Taçon Citation1989a, Taçon and Chippindale Citation2001), and our ongoing fieldwork is constantly revealing more (May et al. Citation2019, Goldhahn et al. Citationin press). Through the classificatory kinship system, Josie called Nayombolmi grandfather, and, as we will demonstrate below, they had a close relationship throughout her childhood.

Fig. 5. Example of a stringybark hut (see also fig. 4). These huts are believed to have belonged to Djimongurr and Nayombolmi, photograph at Manlarrh from the late 1950s from Judy Optiz Collection, now in Kakadu National Park, Parks Australia’s Archive at Bowali, Jabiru, published with their kind permission.

PERFORMING AND PAINTING FOR TOURISTS

Josie’s upbringing coincides with some major socio-economic changes in western Arnhem Land (Levitus Citation1982, Citation1995). Homesteads like Mudginberri as well as the Arnhem Land Timber Camp tried to start up small-scale tourist ventures in the early 1950s. The main attraction for tourists was wildlife adventures, including fishing and hunting. Moreover, at these places, Aboriginal workers created artworks to sell to the visitors and art collectors (Goon Citation1996).

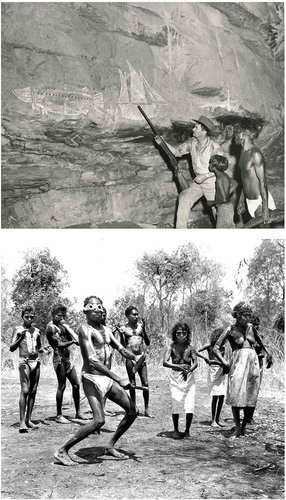

The potential for tourism is well demonstrated by the 1958 purchase of the Arnhem Land Timber Camp by Allan Stewart who transformed it into the region’s first professional safari camp – Darwin Safari Limited, better known as Nourlangie Safari Camp (Stewart Citation1969, Citation1985). Stewart had a background in marketing and had big plans for his safari camp. He used professional photographers such as Ern McQuillan to produce adverts in national magazines, such as The Bulletin (). He also produced short commercial movies that were shown in cinemas all over Australia (Stewart Citationn.d.). His adverts included hunting and fishing in pristine landscapes where ‘Time Stands Still’. They also promoted local Aboriginal culture, with images of rock art and cultural performances (). Josie and her extended family at Manlarrh were a major part of Stewart’s advertising.

Fig. 6. Photographs by Ern McQuillian from 1959 used by Stewart to lure visitors to his Safari Park. Above, photograph of rock art from Nanguluwurr. Josie’s father Djimongurr standing to the right of Allan Stewart. Also appearing is young boy Roy. This photograph appeared as a commercial in the magazine The Bulletin 1st of June 1960. Below, Djimongurr dancing and singing for tourists at Manlarrh. His wife Molly is shown in the centre and daughter Josie, partially obscured, at the back to her right.

Josie’s father was a renowned singer and dancer (, ). Djimongurr’s mesmerizing performances were frequently requested at traditional ceremonial gatherings in western and central Arnhem Land, and further afield. Tourists at Nourlangie Safari Camp were given a small taste of the broad repertoire that her father had mastered as part of his cultural obligations. Most, if not all, of the Aboriginal people staying at Manlarrh, used to participate in these performances, including Josie, her family, and Nayombolmi (, , ). Following Stewart (Citation1969, p. 19), the tourists were enthralled about:

… the way of life of our Aborigines. My Mailli [Aboriginal workers] were greatly interested in them too, and spent many hours with the guests explaining to them their tribal markings, bark paintings, and demonstrating their weapons and hunting skill. Kindly guests still send them Christmas cards, and colour pictures taken at Nourlangie.

Similar engagements and performances for tourists might seem staged and inauthentic. However, as we have argued elsewhere, places such Manlarrh, Mudginberri and the mission at Oenpelli (today’s Gunbalanya), can be seen as crucial nodes for the maintenance of cultural and ceremonial practices, nodes where Aboriginal people from different parts of western Arnhem Land could gather and share stories, mythologies, and law (May et al. Citation2019, Citation2020b). For example, Josie underlines that all performances organized by her father strictly followed established cultural protocols. Many initiation rituals for young children were staged at Manlarrh (Stewart Citation1969). In times where traditional cultural practices were under threat, nodes like Manlarrh and similar places had the potential to become a powerful source for preserving and continuing traditional cultural knowledge, a place where senior Aboriginal people could meet and reinforce traditional cultural values, practices, law, and more. Their song and dances, as well as their artworks, acted as active mediums for transmitting cultural knowledge between generations. The performances and artworks were also a way to educate outsiders about the power of Aboriginal culture (e.g., Berndt Citation1983, Morphy Citation2007).

Fig. 7. Some known rock painters who were staying at Manlarrh in the 1950s and early 1960s. From left to right: Raburrabu (Mission Jack), Nayombolmi (Barramundi Charlie), Toby Gangale and Djimongurr (Old Nym), c. 1960 (photo: Judy Opitz Collection).

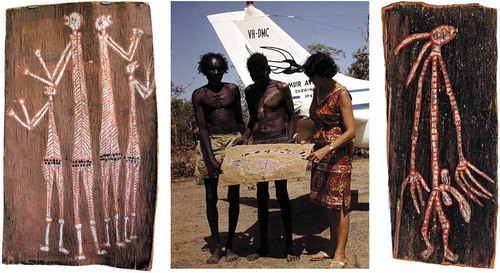

Stewart promoted the creations of bark paintings by local artists which he later sold to tourists (). He even took rock paintings from the landscape and used it to lure potential buyers: ‘A mural, done when Charlie [Nayombolmi] was a young man, is mounted behind my bar at Nourlangie. I have refused offers of 200 USD for it’ (Stewart Citation1969, p. 48). Photographs from the lounge in his safari camp show plenty of artworks for sale (Stewart Citation1969), and Stewart stated that these sold well and provided him with a wanted extra income (Stewart Citation1985). Artworks produced by Djimongurr, Nayombolmi, and other workers at Manlarrh, was traded to visitors from all over the world. Manlarrh and similar nodes of interaction were also increasingly visited by art dealers, such as Dorothy Bennett (Bennett Citation1969, Goon Citation1996, ), which contributed to the ever-expanding market for bark paintings from this region (Carroll Citation1983, Taylor Citation1996, May 2006, Morphy Citation2007).

Fig. 8. Left, bark painting made by Djimongurr c. 1963 at Manlarrh. Photograph by Goldhahn, 2018; Middle, Djimongurr (left) and Nayombolmi (right) at the airstrip at Muriella Park in September 1963 with a jointly made bark painting collected by Valerie Lhuedé depicting a barramundi fish. The lady in this picture is Dorothy Bennett. Photograph from Lhuedé (Citation2012), published with her kind permission. Right, Namorrodoo spirit painted by Nayombolmi c. 1958 (after Bennett Citation1969).

In our interviews with Josie, she expressed that her upbringing at Manlarrh was good and that she only had fond memories to share. She considered Stewart to be a ‘good man’. Josie remembered that her father often created bark paintings at their hut where they lived in an area segregated from the non-Aboriginal workers and the tourists (cf. , , ). Many times Djimongurr grasped the opportunity to tell his daughter stories about the subject matter he painted, sometimes accompanied by a song, introducing and educating Josie about cultural practices and laws. Equally, she often asked him to tell a story, which usually resulted in his taking out his bark and pigments with which to illustrate his words. When the bark painting had served its educational purpose, he would hand it over for sale. When asked what her dad was paid for his artworks, Josie just shook her head and said: ‘Nothing. Just food’.

ART AS EDUCATION – PERSPECTIVES FROM WESTERN ARNHEM LAND

As demonstrated above, throughout her childhood, Josie was surrounded by senior men that were creating art on rocks and barks (). This includes her father Djimongurr who was taught to be an artist by his father. Josie recalls camping in rock shelters where their rock art could be viewed side-by-side. In one of our first discussions, Josie stated that if her family stayed longer than two nights at any rock shelter, ‘my father always left painting behind’. Seeing her father create artworks was an everyday part of Josie’s childhood.

In western Arnhem Land, both rock art and bark paintings were created as part of a broader cultural belief system that included complex artistic traditions that cut across media (Taylor Citation1996). Some of these artworks are argued to have been created for enjoyment and/or to tell an amusing story from everyday life (Haskovec and Sullivan Citation1989, Taçon Citation1989a, Chaloupka Citation1993, see also Munn Citation1973, Mulvaney Citation1996). However, as Taylor (Citation1996) and May (Citation2006) argue, the same artworks could be used in educational situations where they acted as ‘gateways’ unfolding the present-past and future, cultural values, and law. For example, depending on the audience it may be explained as ‘just for fun’, or ‘just a fish’ or, for those of appropriate cultural standing, the deeper meanings may be revealed (Taylor Citation1996, May 2006, Citation2008).

In Josie’s experience most – if not all – artworks were considered ‘public’ and were used to educate children and adults about everyday social and cultural practices and rules. What was restricted was the ‘inside stories’ associated with and unfolding through the artworks. When children grow older, and proceed through ceremonial cycles, slowly transforming children to adults, the same or similar artworks could be articulated differently and used to transfer more restricted esoteric knowledge about local cultural practices and laws concerning hunting and gathering, initiations and ceremonies, marriage and kin systems, mythology and cosmology, and more. Bark paintings were considered to be openly accessible while some of the stories that went with the artworks were exceedingly esoteric (Taylor Citation1996, May 2006, p. 43, Citation2008, see also Morphy Citation1991, Citation1999). Taçon (Citation1989a, Citation1989b) argues that the same cultural knowledge system was in place in viewing and interpreting rock art in this area (see also Brady et al. Citation2020), as also suggested by Josie during our fieldwork. In short: the artwork itself may have been accessible but some aspects of the cultural knowledge hidden within its form was strictly controlled.

WALKING COUNTRY

Working opportunities at Manlarrh often coincided with the dry season from May to October, the time of year best suited to cutting timber and visiting the area as a tourist. In the downtime, Djimongurr and his family used to walk the country and return to more traditional ways of life. Some of these walks were extensive, stretching southwest to Pine Creek and further south to Jawoyn Country close to Katherine (), where Josie and her family visited family and kin, especially Josie’s mother’s family. They also attended ceremonies, collected pigment for paintings, material for baskets, and more.

At this time in his life, Djimongurr had become a Man of High Degree (e.g., Elkin Citation1977) and he acted as a nawiliwili or djungkay over the Nourlangie area (Stewart Citation1969, May et al. Citation2019); a social role and obligation sometimes explained as a form of ‘cultural police’ working under the instructions of the senior Traditional Owners of a clan’s country (Smith Citation1992, Taylor Citation1996, May et al. Citation2019). Among other things, this meant that he had responsibilities to look after places in the Nourlangie area. This resulted in many family trips. During shorter or longer visits during, primarily, the wet season, the family camped in rock shelters or built stringybark huts. The country was generous and provided all they needed in the form of water, food, and supplies for producing artworks. When they camped close to the growing number of tourist parks in the area, it happened that camp owners or workers such as Frank Muir and Fred Hunter at Muriella Park brought out commodities such as flour, sugar, tea, and tobacco.

Josie states that the trips ‘out bush’ during her upbringing were mostly done with her closest family, her father, brother, and mother. Many times they were also accompanied by Nayombolmi and his wife Rosie Almayalk (also known as Nalmainyarag), her classificatory grandfather and grandmother. This is the case for the four painting episodes to which we now turn.

PAINTING COUNTRY

During their travels, Josie often saw her father and Nayombolmi paint. They apparently ‘left no rock empty’. To date we have revisited three rock painting sites where Josie witnessed rock art being created on four occasions. Even today she remembers these events fondly and in great detail. This includes information on when they visited the site in question, how old she was at the time, where they slept, how they kept warm, where they cooked their food, who was travelling with them, how long they stayed, what kind of bush tucker they ate, and more. The same detailed information is also provided about the artwork she saw being created.

One of our first site visits with Josie was in 2018 to a site known as Kurrih. This rock shelter site is one of many djang sites in this region – a sacrosanct place which relates to and embodies the Ancestral Beings movements, actions and presence (e.g., Berndt and Berndt Citation1970, Taçon Citation1989a, Chaloupka Citation1993, Taylor Citation1996), which is also the reason we chose not to show a picture of it here. However, the Kurrih site is a low mushroom-shaped sandstone conglomerate formation, situated about ten metres above the valley floor. The shelter where the family camped is situated on the north side of the rock, facing a huge cliff in the escarpment which provides a secluded feeling. This was a much-favoured camping spot for Josie’s family, and they regularly returned to the Kurrih site on their walks.

This site was first registered by non-Aboriginals in 1973 as part of a fact-finding survey relating to mining exploration and development in the area (McLaughlin Citation1978, Chaloupka Citation1979). Kamminga and Allen (Citation1973, p. 62) described the site in the following way:

The specific archaeological site is a small shelter beneath a flat quartzite boulder […] the area of archaeological deposit is approx. 25 metres2 and its depth is in the range of 0.7 to 1 metre. Stone artefacts are scattered around the surface and also occur in the deposit. The quartzite boulder forming the shelter has had flakes struck off it, probably for manufacturing into tools. Although there is little economic material preserved in the deposit, ochred kangaroo leg bones, jaws and a hair belt have been placed in various crevices in the shelter. Frank Gananguu, a Gunwinggu-Gundjeipmi informant, stated that these ochred kangaroo bones were placed in crevices by women as trophies and magical emblems of the first kangaroo killed by their sons. There are large paintings of fish on the roof of the shelter and a wooden woomera was collected from the floor.

Both the hair belt and the woomera (a spear–thrower), neither which we have been able to re-locate, were left there by Josie’s family. Their last stay at the Kurrih site took place just a few years before Kamminga and Allen’s survey. The mentioned painted bones were part of a coming of age ritual, which in this case related to Josie’s brother Namandali’s ‘first kill’. The bones were placed there by his mother. Today, there are still some tin cans and grinding stones laying around which Josie and her mother used for preparing food. A steel fence bar which they used as a digging stick when they collected yams, is laying in a crevice in the shelter where they left it. There are also lithics scattered on the surface of the shelter, as well as shells. The latter were gathered from a nearby creek.

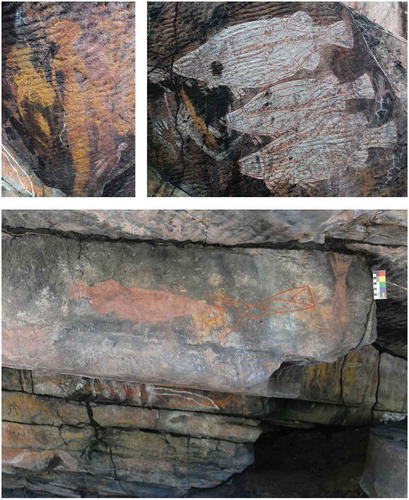

Along the walls of the shelter, there are ample examples of rock paintings. Following Lewis (Citation1988), Taçon (Citation1989a), Chaloupka (Citation1993), and Gunn (Citation2018), most of these images belong to the late Holocene art traditions (see also David et al. Citation2017). The assemblage includes some female figures that Josie saw her classificatory grandfather Nayombolmi paint, as well as three barramundi and a saratoga that were painted by her father (). The site also includes a Painted Hand figure (see May et al. Citation2020b), which Djimongurr created by outlining her brother Namandali’s hand and arm (). These images were made during two painting episodes that Josie recalls. She told us that some of the paintings at this site were created after she requested a story from her father (), a situation that has been recorded elsewhere in western Arnhem Land (see Haskovec and Sullivan Citation1986, Garde Citation2004, Munro Citation2010). Importantly, Josie also showed us five stencils of her hand which her father made on the wall of the shelter on two different occasions; four hand stencils were made at once when she was about seven years old, and another when she was about twelve or thirteen years old (, , ).

Fig. 9. Some of the images painted by Djimongurr and Nayombolmi at the Kurrih site; Top left, a yellow female figure made by Nayombolmi; Top right, three large barramundi fish by Djimongurr; Below, a saratoga and a Painted Hand (with diamond pattern) by Djimongurr, the later made by using his son Namandali’s hand and arm as a model. Note Josie’s hand stencil to the left of the barramundi (top right) and her hand stencils below the saratoga and Painted Hand (below, see also fig. 1). Photographs by Joakim Goldhahn, 2018, and (below) Ines Domingo Sans, 2017.

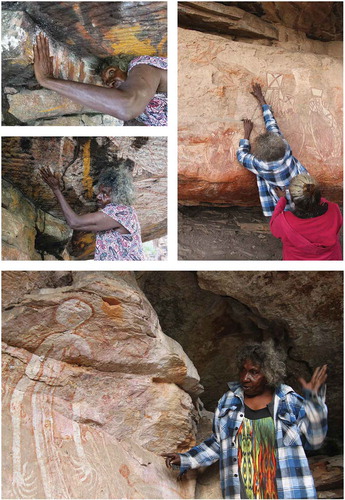

Without a doubt, the Kurrih site was a special place for Josie and her family. She had not revisited it, nor the other sites we discuss below, since 1969 when both her father and her brother passed away. It was in many ways an emotional return, evoking memories of missing loved ones, losses which sometimes cannot be expressed in words. It also evoked great joy, though being on Country with Jeffrey Lee and other family, revisiting the Kurrih site, viewing the artworks, and the things they left behind reminded her of the days when her family walked country together. As a bystander, it was palpable that all these mixed feelings were disquieting Josie, who sometimes needed to be left alone to reflect. Before we returned to our camp, Josie placed her hand on the hand stencil which embodies her childhood presence at the site, and an unbroken connection to her father and Country (, ).

Our next painting episode took place at one of the most iconic rock art sites in the world – the Anbangbang Gallery at Burrungkuy (), also known as Nourlangie Rock (e.g., Chaloupka Citation1982, Citation1993, Jèlinek Citation1989, Welch Citation2015, May et al. Citation2019, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). This site attracts more than 150,000 visitors each year. The latest layers of artworks on this panel were created during a week-long stay in the shelter during the wet season of 1963/1964 when Josie, her mother, and father camped there together with Nayombolmi and his wife Rosie. Josie’s recollection of this painting episode is recounted elsewhere (May et al. Citation2019) and will only be summarized here. During their week-long stay, Djimongurr and Nayombolmi created at least 18 figures on the panel, consisting of eleven anthropomorphic beings (three men and eight women), which are all decorated with intricate body art known to be used in important local ceremonies, three saratoga fish figures, and four mythological beings known to be involved in crucial events that took place in and around the area when the First People walked the earth (). In this case, the artists created the artworks together (cf. ). Josie, who was about twelve years of age at the time, assisted the artists by bringing food, water, and grinding the pigment which was mixed with water and a binder, or ‘bush glue’, known as djalamardi (Dendrobium affine) (May et al. Citation2019).

Fig. 10. The central part of the Anbangbang Gallery in 1968 photographed by Eric J. Brandl (courtesy of AIATSIS, Canberra).

Our last painting episode also took place during the early 1964 wet season. Djimongurr and Nayombolmi were without safari camp duties for a few days and their families walked from Manlarrh to Nanguluwurr (). It took a whole day to walk there in heavy rain. At the site the families camped a few metres apart separated by some rockfall. They brought blankets from Manlarrh to keep them warm during the night-time. As usual, the women and Josie gathered bush tucker, brought water and caught fish, turtles and small game, while the men hunted larger game with their dogs. Food was abundant which gave them plenty of time to paint. On this occasion, they stayed about three days and the artists worked on different panels, situated about 30 metres apart.

During this visit, Djimongurr painted at least seven fish and a long-neck turtle (see Chaloupka Citation1982, p. 27–30, Haskovec and Sullivan Citation1986, Taçon Citation1989a, p. 49, Welch Citation2015, p. 130–134). Before this though, he lifted Josie and painted the outline of her hand and arm. When she was back on the ground he infilled this painting with dots, lines, and diamond patterns. Thereafter, he painted a large barramundi over part of her hand and arm painting (, , ).

Fig. 11. Seven fish and a turtle painted at Nanguluwurr, created by Djimongurr during the wet season in early 1964. Josie’s Painted Hand can be seen to the left underneath the big barramundi (see figs. 1, 12). Photograph by Irina Ponomareva, 2018.

Later, in another part of the shelter, Josie was sitting and watching Nayombolmi paint a mythological being known as Namorrodorr (); a malicious creature which could threaten your life if you did not obey cultural protocols (see Spencer Citation1914, Citation1928, p. 803–804, 807, Mountford Citation1956, p. 203, Brandl Citation1973, p. 179, Taçon Citation1989a, p. 251–261, Chaloupka Citation1993, p. 60). He shared songs and stories related to this being with Josie. These mythological creatures were often used as motifs by Nayombolmi, sometimes in rock shelters (Haskovec and Sullivan Citation1986) more often in his bark paintings (, see Bennett Citation1969). Sotheby’s (Citation2016, p. 28) recorded the following story about Namorrodorr concerning one of his bark paintings:

Namorodos live in the rocky escarpments around Oenpelli with the Mimis and Nakidjidj spirits. They are all credited with being the first inhabitants of the area, and to have taught Aboriginals everything they know about hunting skills and ceremony. It is at night that the spirits leave their rocky homes and come out to hunt and fish, make love, sing and dance, then as dawn breaks they go back inside the rocks and pull shut the door they have blown in the rocks the previous evening. Namorodos are much feared. They have long hair which swishes in the wind as they play around at night, and long arms to which are attached very lengthy finger nails. These are detachable and can be flicked off at will to go straight into the body of a victim who is annoying them. It is mainly because of Namarodos that Aboriginals keep well away from the escarpments at night.

Fig. 12. Josie touching her own hand stencils at Kurrih (top left). Photographs by Fiona McKeague, 2018. Also, Josie touching her Painted Hand at Nanguluwurr (top right, see figs. 1, 11), and (below) Josie with the Namorrodorr figure that her classificatory grandfather Nayombolmi painted in early 1964. Photographs by Paul Taçon, 2019.

Nayombolmi explained to Dorothy Bennett (Sotheby’s Citation1969, p. 20–22) that Namorrodorr is extremely dangerous and that they kill their victims by stealing their livers and kidneys when they sleep. Although the victims wake up, they do not see any marks on their bodies. However, those victims die within three or four days. These creatures were related to flickering lights, ‘Like a bicycles headlight’, and shooting stars in the sky at night. Nayombolmi also explained that it was rare to see these creatures painted in rock shelters (cf. Taçon Citation1989a, p. 251–261, Chaloupka Citation1993, p. 60). He had been taught about Namorrodorr spirits by his father when he painted them on a stringybark hut just before a young Nayombolmi started to grow facial hair (Bennett Citation1969, p. 20–22). Almost 50 years later, he was now the teacher for a girl about the same age, talking, singing, and painting stories at Nanguluwurr ().

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Throughout her childhood, Josie was active in inspiring, viewing, and, sometimes, participating in creating bark and rock art. She was helping with logistics, grinding pigment and preparing binders, gathering food and water. By asking the old men to tell a story she was the inspiration for some of their created artworks. During the process of unfolding stories, mythologies and cosmologies through the creation of art, she was also educated about everyday life, malicious mythological beings, country and culture, cultural protocols and laws, and more. The artworks acted as gateways to reveal the ever present-past and future.

Of importance for this study is that Josie’s presence and participation in the creation of her father’s and classificatory grandfather’s artworks were not always manifested in ways that archaeologists would be able to detect. While the hand stencils her father made left tangible evidence of the presence of a child (), other times her direct involvement is not archaeologically visible (–). Still, they were made in an everyday situation where children were present, inspiring, viewing, participating, and learning.

An interesting circumstance to consider in this context is that artworks which reveal highly ceremonial content, at both Anbangbang and Nanguluwurr (see May et al. Citation2019, Citation2020a, Citation2020b), were created during everyday family visits to these sites, as opposed to the restricted ritual and ceremonial contexts these paintings refer to (–). This is important information to consider as ‘ritual content’ in artworks is often explicitly assumed to be made in ‘ritual contexts’ when rock art is studied and interpreted through formal methodologies (e.g., Langley and Litster Citation2018, also Kaul Citation1998, Layton Citation2001, Ross and Davidson Citation2006, Whitley Citation2011, Goldhahn and Ling Citation2013). Of course, such an assumption should not be taken for granted, but be challenged and explored with an open mind. Importantly, at the time of creation, the full content of these artworks’ significance was not transmitted to Josie, mainly because of her gender and that she had not gone through mandatory ceremonies to handle such knowledge by that age. What was shared was stories appropriate for her age, gender, social and cultural status (see Taylor Citation1996, Morphy Citation1999, May 2006, Citation2008). In either case, the images were created openly for all to watch, but the full story about their meanings and significance was kept for the relevant audiences, as remains the case today (Brady et al. Citation2020).

As has been demonstrated in this article, making art, whether this was conducted at a safari camp or out on country, was a part of everyday life, an interactive way to share and transmit stories and mythologies between generations. Yet, sometimes such artworks also embodied a person’s relation and attachment to certain places, in Josie’s case to Kurrih and Nanguluwurr. By embodying her presence at these sites in the form of hand stencils and a Painted Hand (), and in the case of Kurrih at several times and when Josie was different ages, her father seems to have used their visits to introduce and prepare Josie for obligations and responsibilities that she would first face much later in life (see Munn Citation1973, Morphy Citation1999, Brady et al. Citation2020 for similar cases and theoretical discussions concerning interpreting rock art). Such embodiments, with all the stories and obligations it came with, was a never-ending process.

From the outset of this project, one of Josie’s main concerns was being able to visit some of the sites she camped at as a child. She especially expressed a strong wish to find and revisit the Kurrih site which has special meaning for her. Here it is interesting to note how Josie reacted when she rediscovered her hand depictions at Kurrih and Nanguluwurr. Generally speaking, touching rock art is avoided as the images potentially embody spiritual powers associated with the place and/or the depicted subject matter, and sometimes with the spirit of the artist who made them (Taçon Citation1989a, Citation1989b, Chaloupka Citation1993, May et al. Citation2020b). According to Senior Traditional Owner Jeffrey Lee, this is a cultural protocol that all persons who visit rock art sites should follow and respect. After not visiting these sites for a long time, it was a tangible and deeply emotional experience for Josie to revisit and reconnect to the artwork her father and she made together more than 50 years ago. Her spontaneous reaction was to touch her hand stencils and Painted Hand (, ). It was as if her embodied artworks reinvigorated her attachment to these places and awakened her memories. Josie expressed that the hand figures reminded her of her father, and also a sense of cultural responsibility to transmit her knowledge about country and culture to her own family and kin.

Similar stories and personal attachments to a person’s hand stencils have been documented elsewhere in western Arnhem Land (e.g., Taçon Citation1989a, p. 138, Breeden and Wright Citation1991, p. 171–173, Garde Citation2004, Munro Citation2010, see also Mulvaney Citation1996, p. 12, p. 14). Chaloupka, for instance, writes that:

Almost every person of that generation knew the localities of their own hand stencils and could identify those belonging to others. Some people made stencils of their hand a number of times during their lifetime, in many instances in estates other than their own (Chaloupka Citation1993, p. 232).

Embodying the presence of children’s hands in the landscape seems to have been a cultural practice to ensure intergenerational connections to specific places, a way to introduce children to stories embodied in the landscape, to emplace their belonging, and to prepare them for obligations and responsibilities that they would face later in life.

An important conclusion of this study is that artworks such as rock art are part of broader sharing and transmission of knowledge that follows social and cultural protocols that cut across generations of people and media. Sharing stories around a campfire, performing songs and dances for tourists, or in ceremonial contexts, creating artworks for an emerging art market or in rock shelters, all unfolded people’s life-worlds. In many cultures, children are embedded and embodied in similar social and cultural practices, not separated from it. If we want to be able to deepen our knowledge of children’s relationship to rock art, we must therefore include and embrace a broader set of assemblages and material cultures in our analyses than ‘rock art’.

A chief aim of this article was to address how we can identify and explore children’s role in social and cultural life-worlds, and its relation to rock art. And indeed, our ethnographic case study truly demonstrates the complexity and challenges of teasing out interpretations of childhood from material culture alone. Sometimes we find traces of children manifested and embodied in the landscape, sometimes their presence and participation in the creation of artworks remains ‘silent’. Such an outcome might at first look discouraging. Admittedly, this rings true for all knowledge produced through formal archaeological methodologies – the absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence. Instead of identifying such limitation for archaeology as a problem that we can hardly overcome, we argue that our case study provides mounting possibilities for archaeology in general and rock art research in particular to develop methodological as well as theoretical strategies to bring children and adults together in archaeological analyses. One way forward is to turn the searchlight on our preconceptions and cultural biases and to expose how we can learn and address new questions and explore new opportunities. In this context, to be able to advance our study of children’s relationship to rock art, we suggest, moving beyond trying to identify children through formal archaeological methodologies, to view rock art as an educational heuristic utensil that encompassed and unfolded people’s life-worlds more generally. A start would be to always assume the presence of children or explicitly argue for why they should be excluded from the analyses, because a key feature of rock art is its ability to act as an intergenerational media allowing the transmission of knowledge, gender identity, and power relations to unfold.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Parks Australia as well as PERAHU and the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research at Griffith University for their support. This research was undertaken as part of the Pathways: people, landscape and rock art project and is funded by the Australian Research Council grant Australian rock art: History, conservation and Indigenous well-being, part of Paul S. C. Taçon’s ARC Laureate Project (FL160100123). As a partner in this research, Parks Australia has provided much support and we thank them for their collaboration and field assistance. We are grateful to all the Rangers who joined the fieldwork including Kadeem May, Gabrielle O’Loughlin, Louise Harrison, Jennifer Wellings, Jenny Hunter, Jasmine Nabobbob, Duane Councillor, Joe Markham, Jacqueline Cahill and Cindy Cooper. Thanks to Injalak Arts for helping with logistics for the oral history recordings in 2018. We are grateful to our co-researchers on the Pathways project: Paul S.C. Taçon, Jillian Huntley, Melissa Marshall, Iain Johnston, John Hayward, and Emily Miller. Many thanks also to everyone who helped with the fieldwork in 2017, 2018 and 2019. Our thanks to the other Traditional Owners of the Burrungkuy and surrounding areas for supporting this research and for the many discussions over the years. In particular, we thank Yvonne Margarula, Jessie Alderson, Mandy Muir, M Ngalguridjbal, Stephanie Djandjul, Susan Nabulwad, Fred Hunter, Jenny Hunter, Nakodjok Nabolmo Hunter (dec.), Victor Cooper, May Nango and Djaykuk Djandjomerr. Special thanks to Judy Opitz and Valerie Lhuedé AM for sharing their stories and their photographs with us. Finally, special thanks to Christine Nabobbob for her guidance, translations, interpretation, and friendship.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Arcà, A., 2015. Footprints in the Alpine rock art, diffusion, chronology and interpretation. In: G.H. Hipólito and J.J. García, eds. Symbols in the landscape: rock art and its context. Tomar: ARKEOS Perspectivas em Diálogo, 369–386.

- Bahn, P., 2012. Religion and ritual in the Upper Palaeolithic. In: T. Insoll, ed. The Oxford handbook of the archaeology of ritual and religion. Oxford: Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199232444.013.0023.

- Baxter, J.E., 2005. The archaeology of childhood: children, gender, and material culture. Walnut Creek: AltaMira.

- Bednarik, R., 2008. Children as Pleistocene artists. Rock Art Research, 25 (2), 173–182.

- Behrendt, L., 2005. Law stories and life stories: aboriginal women, the law and Australian society. Australian Feminist Studies, 47, 243–254.

- Bell, C.M., 1992. Ritual theory, ritual practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bell, D.R., 2002. Daughters of the dreaming. 3rd ed. Melbourne: Spinifex Press.

- Bennett, L., 1969. Oosutoraria mikai bijutsu = Art of the dreamtime: the Dorothy Bennett collection of Australian aboriginal art. Tokyo: Kodansha.

- Berggren, Å., and Nilsson Stutz, L., 2010. From spectator to critic and participant: A new role for archaeology in ritual studies. Journal of Social Archaeology, 10 (2), 171–197. doi:10.1177/1469605310365039.

- Berndt, R., 1983. A living art, the changing inside and outside contexts. In: P. Loveday and P. Cooke, eds. Aboriginal arts and crafts and the market. Darwin: Australian National University, 29–36.

- Berndt, R.M., and Berndt, C.H., 1970. Man, land & myth in North Australia: the Gunwinggu people. Sydney: Ure Smith.

- Bradley, R., 2005. Ritual and domestic life in prehistoric Europe. London: Routledge.

- Brady, L., et al., 2020. What painting? Encountering and interpreting the archaeological record in western Arnhem Land. Archaeology in Oceania, 2020. doi:10.1002/arco.5208.

- Brandl, E., 1973. Australian Aboriginal paintings in Western and Central Arnhem Land. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

- Breeden, S., and Wright, B., 1991. Kakadu: looking after the country – the Gagudju way. Sydney: Simon and Schuster.

- Carrington, F., 1890. The rivers of the Northern Territory of South Australia. Royal Geographic Society of Australasia (S.A. Branch) Proceedings, 2, 56–76.

- Carroll, P., 1983. Aboriginal art from western Arnhem land. In: P. Loveday and P. Cooke, eds. Aboriginal arts and crafts and the market. Darwin: Australian National University, 44–48.

- Chaloupka, G., 1979. Survey of sites of significance: Nourlangie rock cultural area. Darwin: Unpubl. report for Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory.

- Chaloupka, G., 1982. Burrunguy: Nourlangie rock. Darwin: Northart.

- Chaloupka, G., 1993. Journey in time. Sydney: Reed Books.

- Chippindale, C., and Taçon, P.S.C., 1998. An archaeology of rock-art through informed methods and formal methods. In: C. Chippindale and P.S.C. Taçon, eds. The archaeology of rock-art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–10.

- Clottes, J., 1995. Les cavernes de Niaux. Paris: Seuil.

- Clottes, J., et al. 1997. Art of the light and art of the depths. In: M.W. Conkey, ed. Beyond art: Pleistocene image and symbol. Berkeley: University of California Press, 203–216.

- Cooney-Williams, J., and Janik, L., 2018. Community art: communities of practice, situated learning, adults and children as creators of cave art in upper Palaeolithic. Open Archaeology, 4, 217–238. doi:10.1515/opar-2018-0014

- Coskunsu, G., ed., 2015. The archaeology of childhood: interdisciplinary perspectives on an archaeological enigma. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Crawford, S., Hadley, D.M., and Shepherd, G., eds., 2018. The Oxford handbook of the archaeology of childhood. Oxford: Oxford University.

- Cunnar, G.E., Högberg, A. eds., 2015. The child is now. 25. Special issue. Childhood in the Past, 8 (2). doi:10.1179/1758571615Z.00000000029.

- David, B., et al., eds., 2017. The archaeology of rock art in western Arnhem land. Canberra: Australian National University Press. Terra Australis 47.

- David, B., and McNiven, I., eds., 2018. The Oxford handbook of the archaeology and anthropology of rock art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Derricourt, R.M., 2018. Unearthing childhood: young lives in prehistory. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Descola, P., 2013. Beyond nature and culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Durkheim, É., 1912. The elementary forms of the religious life. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Elkin, A.P., 1977. Aboriginal men of high degree. 2nd ed. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press.

- Engelhart, M., 1998. Extending the tracks: A cross reductionistic approach to Australian Aboriginal male initiation rites. Stockholm: Stockholm Studies in Comparative Religion 34.

- Fossati, A., 1997. Cronologia ed interpretazione di alcune figure simboliche dell’arte rupestre del IV periodo camuno. Notizie Archeologiche Bergomensi, 5, 53–64.

- Garde, M., 2004. Growing up in a painted landscape. In: H. Perkins, ed. Crossing country: the alchemy of western Arnhem Land art. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 107–111.

- Gärdenfors, P., and Högberg, A., 2017. The archaeology of teaching and the evolution of Homo docens. Current Anthropology, 58, 188–201. doi:10.1086/691178

- Goldhahn, J., 2008. Rock art studies in northernmost Europe, 2000–2004. In: P. Bahn, N. Franklin, and M. Strecker, eds. Rock art studies: news of the world 3. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 16–36.

- Goldhahn, J. 2012. In the wake of a voyager: feet, boats and death rituals in the North European Bronze age. In: A.M. Jones, et al., eds. Image, memory and monumentality: archaeological engagements with the material world. London: Prehistoric Society’s Research Paper, 218–232.

- Goldhahn, J., and Fuglestvedt, I., 2012. Engendering North European rock art – bodies and cosmologies in stone and bronze age imagery. In: J. McDonald and P. Veth, ed. A companion to rock art. Chicester: Wiley-Blackwell, 237–260.

- Goldhahn, J., and Ling, J., 2013. Scandinavian Bronze Age rock art – contexts and interpretations. In: H. Fokkens and A. Harding, eds. Handbook of European bronze age. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 270–290.

- Goldhahn, J., 2019a. Birds in the Bronze Age: a North European perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Goldhahn, J., 2019b. Unfolding present and past (rock art) worldings. Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Culture, 12 (2), 63–77. doi:10.1080/1751696X.2019.1610217.

- Goldhahn, J., May, S.K., and Taçon, P.S.C., in press. Revisiting Francis Birtles’ car: exploring the 1929/30 cross-cultural encounter between an Australian icon and Aboriginal artist Nayombolmi at Imarlkba gold mine, Northern Territory. In: History Australia.

- Goon, K., 1996. Dorothy Bennett – a dreaming. Northern Perspective, 19 (1), 23–35.

- Gunn, R., 2006. Hand sizes in rock art: interpreting the measurements of hand stencils and prints. Rock Art Research, 23, 97–112.

- Gunn, R., 2018. Art of the ancestors: spatial and temporal patterning in the ceiling rock art of Nawarla Gabarnmang, Arnhem Land, Australia. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Hamilton, A., 1980. Dual social system: technology, labour and women’s secret rites in eastern Western Dessert of Australia. Oceania, 51 (1), 4–19. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4461.1980.tb01416.x.

- Haskovec, I.P., and Sullivan, H., 1989. Reflections and rejections of an Aboriginal artist. In: H. Morphy, ed. Animals into art. London: Unwin Hyman, World Archaeology, 57–74.

- Haskovec, P., and Sullivan, H., 1986. Najombolmi: the life and work of an Aboriginal artist. Darwin: Unpublished report to the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service 1986.

- Hays-Gilpin, K., 2004. Ambiguous images: gender and rock art. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press.

- Hays-Gilpin, K., 2012. Engendering rock art. In: J. McDonald and P. Veth, eds. A companion to rock art. Chicester: Wiley-Blackwell, 199–213.

- Högberg, A., 2018. Approaches to children’s knapping in lithic technology studies. Revista De Arqueologia, 31, 58–74. doi:10.24885/sab.v31i2.613

- Jelínek, J., 1979. A painted bark shelter in Central Arnhem Land. In: J.M. Cordwell, ed. The visual arts, plastic and graphic. The Hague: Mouton Publishers, 365–369.

- Jelínek, J., 1989. The great art of the Early Australians. Brno: Anthropos Institute.

- Kaberry, P.M., 2004. Aboriginal women: sacred and profane. London: Routledge.

- Kamminga, J., and Allen, H., 1973. Alligator Rivers environmental fact-finding study. Darwin: Government Printer.

- Kaul, F., 1998. Ship on bronzes: a study in Bronze Age religion and iconography. Copenhagen: National Museum, PNM Studies in Archaeology and History.

- Langley, M.C., and Litster, M., 2018. Is it ritual? Or is it children? Distinguishing consequences of play from ritual actions in the Prehistoric archaeological record. Current Anthropology, 59 (5), 616–643. doi:10.1086/699837.

- Layton, R., 2001. Ethnographic study and symbolic analysis. In: D. Whitley, ed. Handbook of rock art research. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, 311–331.

- Levitus, R., 1982. Everybody Bin all day work: a report to the Australian National Parks and Wildlife service on the social history of the alligator rivers region of the Northern territory, 1869-1973. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

- Levitus, R., 1995. Social history since colonization. In: T. Press, ed. Kakadu: national and cultural heritage and environment. Darwin: Australian National University, 64–93.

- Levitus, R., 2011. The life of Butcher Knight Namandarrk. Canberra: Unpublished Report to Parks Australia, Robert Levitus Anthropos Consulting Services.

- Lewis, D., 1988. The rock paintings of Arnhem Land: social, ecological, and material culture change in the post-glacial period. Oxford: BAR International Series 415.

- Lhuedé, V., 2012. The sunrise of Aboriginal art in Capricornia country. Milsons Point: Valued Books.

- Lillehammer, G., 1989. A child is born. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 22, 89–105. doi:10.1080/00293652.1989.9965496

- Lillehammer, G., 2015. 25 years with the ‘Child’ and the archaeology of childhood. Childhood in the Past, 8 (2), 78–86. doi:10.1179/1758571615Z.00000000030.

- Mackie, M.E., 2015. Estimating age and sex: paleodemographic identification using rock art hand sprays, an application in Johnson County, Wyoming. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 3, 333–341. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.06.023

- Malmer, M.P., 1981. A chorological study of North European rock art. Stockholm: KVHAA, Antikvariska Serien 32.

- May, S.K., 2006. Karrikadjurren: creating community with an art centre in Indigenous Australia. Unpubl. Doctoral Dissertation. Canberra. Australian National University.

- May, S.K., 2008. Learning art, learning culture: art, education, and the formation of new artistic identities in Arnhem Land, Australia. In: I.S. Domingo, S.K. May, and D. Fiore, eds. Archaeologies of art: time, place and identity. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 171–194.

- May, S.K., et al., 2019. “This is my father’s painting”: A first-hand account of the creation of the most iconic rock art in Kakadu National Park. Rock Art Research, 36 (2), 199–213.

- May, S.K., et al., 2020a. New insights into the rock art of Anbangbang Gallery, Kakadu National Park. Journal of Field Archaeology, 45 (2), 120–134. doi:10.1080/00934690.2019.1698883.

- May, S.K., et al., 2020b. Survival, social cohesion and rock art: the Painted Hands of Western Arnhem Land, Australia. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 1–20. doi:10.1017/S0959774320000104.

- May, S.K., and Blair, S., eds., 2012. Kakadu historical sites. Anlarr – Jim Jim Store – Munmalary. Bowali: Unpubl. Report to Parks Australia, Kakadu National Park.

- McDonald, J., and Veth, P., eds. 2012. A companion to rock art. Chicester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- McLaughlin, D., 1978. Aboriginal art sites: locations & photographs. Koongarra Project, AIATSIS Manuscript collection MS 2372. Noranda Australia Limited.

- Miller, D., 1985. Artefacts as categories: astudy of ceramic variability in central India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Moore, J., and Scott, E., eds., 1997. Invisible people and processes: writing gender and childhood into European archaeology. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Morphy, H., 1991. Ancestral connections: art and an Aboriginal system of knowledge. Chicago University Press. Chicago.

- Morphy, H., 1999. Encoding the Dreaming – a theoretical framework for the analysis of representational process in Australian Aboriginal art. Australian Archaeology, 49, 13–22. doi:10.1080/03122417.1999.11681648

- Morphy, H., 2007. Becoming art: exploring cross-cultural categories. New York: Berg.

- Mountford, C.P., 1956. Records of the American-Australian scientific expedition to Arnhem Land, Vol. 1: art, myth and symbolism. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Mulvaney, K., 1996. What to do on a rainy day. Rock Art Research, 13 (1), 3–20.

- Munn, N.D., 1973. Walbiri iconography: graphic representation and cultural symbolism in a Central Australian society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Munro, K., ed, 2010. Bardayal ‘Lofty’ Nadjamerrek AO. Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art.

- Native affairs branch patrol officers reports 1950–1952, 2019. http://www.cifhs.com/ntrecords/ntpatrol/F1_1952-602_Patrol_Reports.html [Accessed 21 Sept 2019].

- Ross, J., and Davidson, I., 2006. Rock art and ritual: an archaeological analysis of rock art in Central Australia. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 13 (4), 304–340. doi:10.1007/s10816-006-9021-1.

- Ryan, J., 1990. Spirit in Land: bark paintings from Arnhem Land. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria.

- Smith, C., 1992. Jungayi care for country. Barunga: Video documentary produced for the Barunga-Wugularr Community Government Council.

- Snow, D.R., 2006. Sexual dimorphism in Upper Palaeolithic hand stencils. Antiquity, 80, 390–404. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00093704

- Sofaer, J.D., 2000. Children and material culture. London: Routledge.

- Sotheby’s Aboriginal Art. 2016. London 21 September, Lot 14.

- Spencer, W.B., 1914. Native tribes of the Northern Territory of Australia. London: MacMillan.

- Spencer, W.B., 1928. Wanderings in wild Australia. London: MacMillan.

- Stewart, A., 1969. The green eyes are buffalo. Melbourne: Lansdowne.

- Stewart, A., 1985. Allan Stewart interviewed by Neil Bennetts [sound recording] 1985. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-215644546 [Accessed 16 Oct 2019].

- Stewart, A., n.d. East of the Alligator. Nourlangie Safari Camp: Allan Stewart Production.

- Taçon, P.S.C., 1989a. From Rainbow snakes to ‘x-ray’ fish: the nature of the recent rock painting tradition of western Arnhem Land, Australia. Unpubl. PhD thesis. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Taçon, P.S.C., 1989b. Art and the essence of being: symbolic and economic aspects of fish among peoples of western Arnhem Land, Australia. In: H. Morphy, ed. Animals into Art. London: Unwin Hyman, 236–250.

- Taçon, P.S.C., and Chippindale, C., 2001. Nayombolmi’s people: from rock painting to national icon. In: A. Anderson, I. Lilley, and S. O’Conner, eds. Histories of old ages: essays in honour of Rhys Jones. Canberra: Pandanus Books, Australian National University, 301–310.

- Tacon, P.S.C., and Davies, S.M., 2004. Transitional traditions: port Essington bark-paintings and the European discovery of Aboriginal aesthetics. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2004 (2), 72–86.

- Taylor, L., 1996. Seeing the inside: bark painting in western Arnhem Land. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thomas, J., 2004. Archaeology and modernity. London: Routledge.

- Thompson, J.L., Alfonso-Durruty, M.P., and Crandall, J.J., eds., 2014. Tracing childhood: bioarchaeological investigations of early lives in antiquity. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- van Gelder, L., 2015a. The role of children in the creation of finger flutings in Koonalda Cave, South Australia. Childhood in the Past: An International Journal, 8 (2), 149–160. doi:10.1179/1758571615Z.00000000036.

- van Gelder, L., 2015b. Counting the children: the role of children in the production of finger flutings in four Upper Paleolithic caves. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 34 (2), 120–131. doi:10.1111/ojoa.12052.

- Welch, D., 2015. Aboriginal paintings at Ubirr and Nourlangie: Kakadu National Park, Northern Australia. Darwin: David Welch Publishing.

- Wesley, D., et al., 2018. Indigenous built structures and anthropogenic impacts on the stratigraphy of Northern Australian rock shelters: insights from Malarrak 1, north western Arnhem Land. Australian Archaeology, 84 (1), 3–18. doi:10.1080/03122417.2018.1436238.

- Whitley, D.S., 2005. Introduction to rock art research. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

- Whitley, D.S., 2011. Rock art, religion and ritual. In: T. Insoll, ed. The Archaeology of ritual and religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 307–326.

- Worsnop, T., 1897. The prehistoric arts, manufactures, works, weapons, etc., of the Aborigines of Australia. Adelaide: Government Printer.