Abstract

This article presents an alternative to archaeological object observation through an exercise in alterity and slow looking. It is inspired by the movement of Slow Archaeology, and based on the art of slow looking, perspectivism, and 16th century Japanese object aesthetics in the context of the Japanese tea ceremony. The exercise experiments with different vantage points, embodiment, and empathy related to theories of the ontological turn and non-discursive knowledge. Stimulating ourselves to employ different ways of looking can be a helpful tool in starting to think about difference and alterity, but can also possibly reach new insights on ancient object-use, performance, and perception. It can therefore form an additional instrument to formal object analyses already practiced in archaeology, as well as be a form of emancipation in education as it draws on other, non-discursive, forms of knowledge.

INTRODUCTION

The need to slow down has become increasingly apparent in and beyond academia, as we continue to watch how capitalism is eroding democracies, economy, ecology, health care, and humanity, leaving us in a crisis of care (Koch Citation2012, Fraser Citation2013, Parr Citation2013,O’Donnell et al. Citation2017, Carrier Citation2018, Case and Deaton Citation2020 and many others). The university as a subsystem is of course no exception, and there is a growing body of critical scholarly voices who are carefully charting how neoliberal and privatized anti-democratic policies have affected scholarship in terms of inclusion, collaboration, justice, care, technology, and production (Mountz et al. Citation2015, Walker Citation2016, Stengers Citation2018, Breeze et al. Citation2019). Universities might seem slow institutions but are increasingly about speed through advanced capitalist valorization of quantitative publication pressure, student numbers, high-impact-factor journals, and the industrial capture of financial research resources (Hall Citation2016, Stengers Citation2018). Ironically, in archaeology the slow movement took hold with quite some speed during the last decade, where we see slow science, but also concepts such as degrowth, speculative ethics, radical and punk science, anarchism, and other anti-capitalist movements becoming increasingly addressed and implemented (see Morgan Citation2015, Rizvi Citation2016, Rathbone Citation2017, Caraher Citation2019, or Flexner Citation2020). These of course, all take quite different approaches to the concept of slowness in terms of both subject matter and goals.

In this article, I want to present an alternative way to look at objects through the lens of slow archaeology. I designed this method during the teaching of a graduate course at the Joukowsky Institute of Archaeology and the Ancient World at Brown University, called ‘Slow Archaeology’. The general premise of this course was to look at academia and archaeology, and observe in what ways we could slow down. During the course, we carefully analyzed the academic system: its knowledge production and its ethics, and speculated about possible (and impossible) ways of change. My pedagogical aims were focused on making theories of the ontological turn in anthropology more tangible and actual for students and on showing the existing webs of power, privilege, and time capitalizations in academia; the way we form part of this and ways we can resist. What Ialso wanted was to establish a form of emancipation (Rancière Citation1991), by stimulating other, non-discursive, types of knowledge as a critical, more radical form of pedagogy. This discussion is not new of course, however, I wanted to achieve these goals through practice. This resulted in the design of an exercise in ‘slow looking’; a playful exercise aimed at experimenting with different ways of knowing through object analysis. In a few rounds of carefully looking at an object from different vantage points, I wanted to shake our ways of viewing and attempt to perform alterity (Alberti Citation2016a, Bertelsen and Bendixsen Citation2017). This was done by taking Japanese metaphysics seriously as an alternative way of looking and a way of disrupting the western empiricist framework as a normalized understanding.

I suggest that this attempt of incorporating slowness and ontological difference into object analysis, as was done through this exercise, has value in, but also beyond the classroom, and could become used in archaeological research as an alternative, speculative way to engage with the objects that we study. Slow looking, I propose, can be a tool to incorporate ontological difference in a more embodied way. In this article, I first briefly discuss the way I define Slow Archaeology and slow looking, and then move on to a description of the outline of the exercise. I end with a discussion on the possibilities of a broader implementation of the exercise in archaeological research, in which I argue that we not only gain from slowing down and looking at things from different worlds of understanding, but that slow looking and performing alterity might be a relevant tool in the actual practice of ontological difference.

THE ROAD TO SLOWNESS

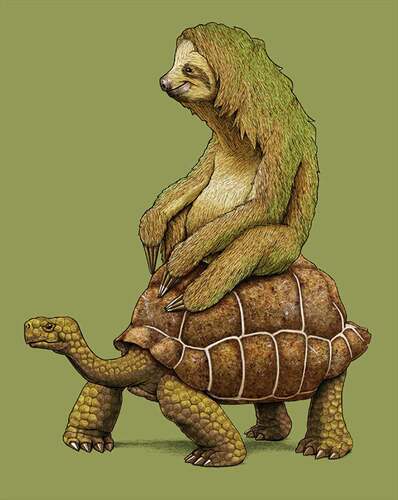

What I personally think is most important within Slow Archaeology are matters of privilege, responsibility, and care. This focus, instead of just thinking about how we can create more time, is far removed from how the general conception of the slow movement gained popularity in society, and therefore needs some elaboration. There is a very justified criticism against the slow movement’s initial conception of ‘taking more time’ for things, for it actually sustained a neoliberal system based on pyramids of outsourcing, exploitation, and elitism, where only those on the very top of the pyramid can actually slow down. ‘Slow’ in this case points to a lifestyle in which the slow food experts and influencers write books, enjoy and share images of their slow cooked meals, and propagate a healthy existence, but are meanwhile being served by an exploited service staff. This points to the irony of the propagator of a slow and mindful existence who established a 4-hour workweek, but relied on a poorly paid remote assistant from India to do so.Footnote1 For archaeology, this issue has been addressed by Graham, asking: ‘who ultimately benefits from a “slow” archaeology, and with whom would the power rest in such a scheme?’ (Graham Citation2017). As Sarah Sharma states in her brilliant book In the Meantime. Temporality and Cultural Politics: ‘Fiber affects fiber across the social fabric’, and we need to make visible these fibres of entangled and uneven politics of temporality (Sharma Citation2014, p. 128). Slow Archaeology, therefore, is a way of deconstructing current power-chronographies and time-capitalizations in academia and not at all about speed or about slowing down. It is about closely observing speed and privilege within existing neoliberal temporalities and making oneself aware of the position people take up in these entanglements, ultimately leading to one’s own responsibilities towards them (). That I can do this, read about this topic, have space to create a complete course on the subject matter, makes me very privileged, meaning I have a responsibility to act against inequality and address issues of injustice.

Fig. 1. The road to slowness is not about speed, but about attention and care (Speed is Relative, copyright Josh Billings, jbillustrator.com).

Closely related to speed and privilege within Slow Archaeology is the issue of the discipline’s and academia’s western empirical structures that are rooted in a white, masculine, colonial framework (famously brought to light by Edward Said (Citation1978), and more recently by (Ahmed Citation2012, Grosfoguel Citation2013, p. 73–90, Chatterjee and Maira Citation2014). As Stengers notes in her slow science manifesto: ‘whatever the future, research institutions are not equipped to formulate it’ (Stengers Citation2018). This is an important observation: we are working in- and with an institution unequipped for the people who currently inhabit it, unequipped for the world outside, and unequipped for the future. Moreover, its structure has broader implications than just for the university as a system, as it has thoroughly shaped how people should perceive truth through a ‘cognitive imperialism’: a global incursion of Enlightenment metaphysics (Kawagley Citation2006). The institution of academia therefore is a good example of Sharma’s large social fabric, but also definitely one through which we can try to affect one of its fibres. This has increasingly been done by a number of feminist, intersectional, and decolonial approaches in archaeology that offer inspiring and constructive ways to actually fight cognitive imperialism (Watkins Citation2001, Battle-Baptiste Citation2011, Todd Citation2016). This also counts in a different way for non-discursive approaches such as tacit knowing, affectivity, and multimodality in archaeology and anthropology (as has been attempted by for instance by Pink Citation2011, Ingold Citation2013a, or Hamilakis Citation2014, amongst others).

Although the more politicized part of slow looking in terms of observing speed and privilege is vital, with the following exercise I want to further tune in on the intertwined issue of privilege and cognitive imperialism. Non-canonical scholarship and non-discursive forms of knowledge and practice will be the basis for the practice of this slow looking, which has as its aim to combine discerning detail and paying attention, disturbing disciplinary convictions and spark imagination in different ways. It is meant as a deliberate ‘refusal to lock our theories or materials within scripted frameworks, new or old’ (Alberti et al. Citation2011, p. 905). I will now discuss the particularities of moving from Slow Archaeology to slow looking.

SLOW LOOKING

For the archaeologist it may sound quite off the wall that I argue we need to engage in slow looking, as it seems one of the most inherent practices of the discipline. Archaeologists usually spend hours observing stratigraphic profiles, objects and fragments of objects with a painstaking rigour: we describe them following a structured process not to miss out on any detail, we classify them, we draw them, we take them apart to the finest threads and study those threads under a microscope. In essence, archaeologists are slow lookers and I believe there are many aspects other fields and practices can learn from this way of observation, also in terms of slowness. However, we also have to admit that although the observation might be careful, it happens mostly in the context of fieldwork and from within an unyielding and narrow western empirical framework that has hardly been reformed since it was first installed. Observation for an archaeologist, thus, is a functional process, predominantly about identification and classification as we can see for instance in formal pottery classificatory descriptions such as this:

Ceramic- handle- terra sigillata- Arezzo Ware- Late First Century BC- fabric 5 YR 5/6.

The way we apply such rigorous methods vis-à-vis emic/etic interpretation frameworks has of course been dealt with extensively in processual/post-processual debates and does not need to be reiterated in this article. I want to focus instead on the practice of looking itself. It is not just about how we look, it is about the reason why we are looking; what do we actually want to learn from these objects? Part of the answer is that there are many more things to gain from observation than classification, and it is a shame that we do not widen our scope more often since we have the objects at our disposal. I designed the exercise to force myself and my students to pay attention to details in different ways than formal description normally allows for, and thus make room for other ways of understanding. The sources of inspiration are threefold: Tishman’s work on Slow Looking, the ōtsubo artistic and poetic performance within the sixteenth century Japanese tea ritual, and theories on perspectivism and the ontological turn in anthropology. I will briefly discuss each of them here.

SLOW LOOKING

Shari Tishman, an educational researcher who studies the role of close observation in learning, maker-centred pedagogy, and learning in- and through the arts, wrote a book named ‘Slow looking’, which was of great help in designing the object experiment. Tishman’s ideas are especially significant because of her focus on slow looking as a skill and an epistemic virtue, as something that can be trained and, therefore, be potentially applicable in all disciplines that use observation as an analytical tool (Tishman Citation2018). Many aspects from Tishman’s work are already familiar to an archaeologist or anthropologist, such as the close connection between observation and (thick) description, and the power of drawing as an observational tool. Among the vital points that she makes, is the inclusion of other perspectives than the human in observation and to engage in collaborative, creative ways of looking inspired by art and poetry. An example of such ways of observation is the ecological art project ‘One Cubic Foot’ by David Liitschwager (Liitschwager Citation2012, Tishman Citation2018, p. 56), which consisted of a detailed description of everything that passed through a metal frame of a cubic foot (ranging from New York’s Central Park, Table Mountain in South Africa, to the cloud forest of Costa Rica). Through the project, the artist wanted to know how much life exists in just one cubic foot, and how we can describe this. Together with local scientists, Liittschwager measured and photographed, as precisely and faithfully as possible, every creature that lived in or passed through the cube during 24 hours. Another illustrative demonstration of an attempt of detailed looking comes from literature in the form of George Perec’s (Citation1975) Tentative d’épuisement d’un lieu parisien (An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris). Here, the author observes and describes – or exhausts – everything mundane passing him by while seated at the Saint-Sulpice Square in Paris. It is an act of slow looking, in which attentiveness is processualised in a different, creative way. This means that through art, through literature and slow looking it is possible to create different ways of access to our surroundings, ways that are not present in standardized archaeological observation and recording methods. The true value of Tishman’s work lies not in its analytical aspects, but in the interdisciplinary framework she offers through paying immersive attention to detailed observation as the examples above testify, as well as the emphasis on different vantage points (physical and conceptual). This includes for instance the altering of perspectives between looking at the fabric of something under a microscope, but at the same time connecting this perspective to the experience of the object from a bug’s point of view (Tishman Citation2018, p. 58).

THE CHANOYU RITUAL AND JAPANESE AESTHETICS

Attentiveness and vantage points lead us to the second and most important inspiration for the developing of the current object assignment: the Japanese sensorial and aesthetic practice surrounding the storage jars involved in the Japanese tea ceremony (chanoyu). Chanoyu (dating back to at least the 9th century AD) is a ritual of preparing and serving the Japanese green tea Matcha, typically conducted in specially constructed spaces, and not so much focused on drinking tea but on aesthetics and performance. The ceremony, initially confined to temples, became diffused to the warrior elite and merchant classes and is still practiced in Japanese culture by specialized tea masters (Surak Citation2013, p. 58–59). Its practice is regarded as a non-Western art form that exhibits tranquillity, refinement, and humility along with an appreciation of the irregular and transient (Wilson Citation2018, p. 33). Generally, the tea ceremony performance is defined as ‘an intellectual diversion in another world’ (Sōshitsu Citation1998, p. xxiii, Tokugawa Citation1982). It therefore stretches beyond a secluded, elitist, cultural tradition, and in many ways provides a way of access into Japanese metaphysics. Chanoyu represents a distinctive way of perceiving beauty, which formed the foundation for the Japanese aesthetic perspective that began to take conscious form during the Muromachi period (1336–1573) (Yanagi Citation1989, Citation2019, p. 147). Not just the performance itself, the art of making tea, was important the intellectual and poetic engagement was just as much an integral part of the practice. What is significant in the context of slow looking is how the executing masters of the tea ceremony treated and experienced some of the objects involved during the ritual. Obviously, all of the utensils used in the ritual were treated with the utmost care and attention, but it was a particular vessel-type that was especially revered. The storage jars for the dry tealeaves, called chatsubo (tea urn) or ōtsubo (large jar) became a vital part of aesthetic appreciation within the ceremony. They were known in all their little details and their imperfections were not only recognized, they were admired and celebrated in poems, memoirs, and other writings (one of the most famous being that of Yamanoue no Sõjiki’s Records). Some of the pots became so illustrious they were even given names (Surak Citation2013). An example of such a vessel is that received the name ‘Chigusa’.

Fig. 2. Tea-leaf storage jar, named Chigusa. Mid 13th–mid 14th century China, Southern Song or Yuan period. Stoneware with iron glaze, 41.6 × 36.6 cm (National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Freer Gallery no. F2016.20.1).

The attention, admiration, and occasional naming is all the more astonishing when one realizes that the vessels in question were common ceramics from China, mostly produced in the 13th and 14th century, and did not possess any significant artistic value for the Chinese. The ōtsubo listed in Yamanoue no Sõjiki“s Records and those that are still preserved, such as Chigusa (Watsky and Cort Citation2014), all have a comparable size and shape between 30 and 40 cm, with a flat base, ovoid body, straight neck, small mouth and four lugs around the shoulder that could hold chords (Watsky Citation2013). According to Watsky, what made the ōtsubo compelling for the Japanese were not only their visual qualities, but ‘their adaptability as objects to match a tea mindset that sought to integrate tea vessels into the landscape – both actual and poetic – of Japan’ (Watsky Citation2013, p. 149).

These observations on the aesthetic performativity and materiality of the ōtsubo vessels are significant. The adaptability as an aesthetic characteristic, able to make a radical cultural-poetic re-appropriation possible, informs us about aspects of object experience that are valuable beyond Japan’s cultural traditions. Japanese aesthetics and aesthetic knowledge are material in their very essence, as the underlying principle of the beauty of tea was not an intellectual concept, but consisted of concrete objects that acted as intermediaries: the ōtsubo, but also the teahouse, the fire, the garden path, and the utensils (Yanagi Citation2019, p. 148). It were the objects and the detailed study of their imperfections that allowed the tea masters to ponder the complexities of beauty; they were an active source in the creation of their world-making. Hence, trying to incorporate such object-performances into our method of slow looking is a quest for something much more than a different way of looking; it will stimulate a different, object-based, mode of thinking. Furthermore, the holistic, aesthetic, and multisensorial aspects of the appreciation are characteristics that even in such a specific ritualized context like the Japanese chanoyu, lie much closer to many common past and present object experiences than the formal and empiricist analyses. Lastly, the chanoyu ritual informs us about people and their skill. The tea experts in charge of the ritual – those who were handling the objects and capable to observe, write about, and name vessels within the chanoyu ritual – were held in very high regard by the Japanese and considered to be a specialized group who possessed a unique poetic judgment and aesthetic skill. They were regarded as people that could ‘hear with the eyes’ (Watsky Citation2018). If we want to create a way to step away from western rational and formalized views and open up to other ways of looking and knowing, this is what we need to do: we need to hear with the eyes.

THE ONTOLOGICAL TURN AND ALTERITY

The chanoyu aesthetics presented radical new meanings to objects and thought, and without knowledge of the world in which these Japanese performances and shaping took place, we could only have limited understanding of the objects. However, tea ceremony aesthetics are not just a perspective; it is a substantiation of Japanese ontology. The acknowledgement of this reality and a serious engagement with instances of ontology to better understand objects and improve scholarly work, is exactly what the ontological turn in anthropology has proposed as a way forward in rethinking the discipline (Holbraad and Pedersen Citation2017). No longer should we view aesthetic performance such as chanoyu as just an ‘exotic’ cultural practice only to be tested against a western empirical standard. New metaphysics such as perspectivism and critical decolonization have distanced themselves from the idea that perception is just a matter of perspective (epistemology). As a result of this, scholars increasingly allow other ways of knowing and being into the academic discourse (Battle-Baptiste Citation2011, Descola Citation2011, Viveiros de Castro Citation2012, Citation2015, Halbmayer Citation2012, p. 9–23, Kohn Citation2015, Todd Citation2016, Alberti Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Bertelsen and Bendixsen Citation2017, Rizvi Citation2019 amongst others). For the disciplines of archaeology and anthropology that are dealing with worlds from the past and contemporary non-western contexts, this turn is not just an important expansion; it is a logical step forward in their efforts to interpret the past. Obviously, this is not an easy step; perhaps in a fundamental way it is impossible to ‘understand’ different ontologies. As one of the philosophical founders of the ontological turn, Viveiros de Castro stated, the conundrum exists in ‘How to create the conditions of the ontological self-determination of the other when all we have at our disposal are our own ontological presuppositions’ (Viveiros de Castro Citation2015, p. 11). This means that while we need to aim for permanent decolonization of thought and accept ontological difference, as ontology is the nature of being, it is affecting all thought and all embodied dealings with the world, and therefore is the very basis of any understanding.

However, this being said, the confrontation is already an improvement, as understanding ourselves to be ‘Other’ allows the western masculine gaze to open up to different worlds with a more deferential eye. The ontological turn is therefore about the need to focus on difference, or alterity, in a more radical way than has been done before. Alberti emphasizes alterity for archaeology, and argues that a way for the discipline to realize the potential of its materials and to tell us something different about the past is by accepting alterity as the ontological difference lying at the roots of archaeological material (Alberti Citation2016a, pp. 138–45). In trying to better understand the past, we need to open up to other knowledge systems. On a minimal scale therefore, through the concept of alterity, we can enfold Other worlds in relation to our own, and the object exercise designed in this article wishes to do this through performance.

It is very important to note in this respect, that this enfolding of ‘Other’ ways of knowing do not only include the past or far-away Amazonian world-makings, they also comprise many western ways of experience that the scientific theory of knowledge is incapable to account for due to cognitive imperialism. There are many domains beyond the reach of language observation in everyday life, where western empiricism proves a limited and insufficient method. For this reason, other modes of knowledge need to be addressed in order to grasp more fully the non-discursive aspects of experience (Kress Citation2010, p. 15). This means including tacit knowledge, such as famously described by Polanyi (Citation1966). This comprises ways of knowing that grow through engagement and practice and as affective, embodied, lived experiences of a multimodal nature (Polanyi Citation1966, Ceraso Citation2014, p. 104). This also includes aesthetic knowledge, a different and specific subjective way of looking that is often excluded as a valid way of observation in standard western formal object analysis (Sibley Citation1959, pp. 421–450, Goldman Citation2006, Kieran Citation2013, pp. 369–379). Aesthetic experience can be seen, according to John Dewey, as a ‘heightened vitality’, it signifies active and alert engagement with the world; as a non-discursive knowledge it is a form of participative knowing, doing, feeling, and making sense (Dewey Citation1934, Citation1938). Even though we could argue that all these non-discursive practices are framed by similar ontological assumptions as those that frame our western empirical approach, we need to remain very critical about the currently assumed meta-contrast between a singular homogenous western ontology vs. a complex plurality of non-western and past ontologies. Although there is a western gaze that is dominant, it is not homogenous. Forms of alterity and multimodal experiences are all around us, and an integration of these in observation practices is useful, if not vital, in order to become more aware of the experience of objects and worlds in past and present. Our descriptions, responses, and evaluations are not only informed by thought, but are shaped, constrained, and guided by a large variety of non-discursive criteria. Slow looking, the chanoyu practice, and the ontological turn therefore form a combination to a new alternative way of object analysis. One that I will now outline.

THE EXERCISE

This section details how to do the exercise, which can be carried out with a group varying from 2 to 12 participants but can also be done alone (perhaps when one decides to use it for research purposes). The start for the instructor is of course selecting an object for the exercise, and it is important to note that it does not matter at all what kind of object is chosen, although something with many details or traces of use is preferable. Depending on the group-size, a larger or more complex object can be selected. Because I wanted to do this as an archaeological exercise, I worked from a certain degree of familiarity and for this reason chose pottery: a modern, second-hand green-and brown glazed bowl of about 10 inches, hand-made and used, which I purchased from a local thrift-store (see ). However, as already stated, any object should do. The group consisted of nine people (seven graduate students, one undergraduate student and one colleague from the department). The object was placed on the centre of the table with all the participants sitting around it, so that they were able to pass the object around and look at it in detail. The exercise is completed in five to six different rounds, with a flexible running time between 2 to 4 hours (taking more time is of course better. We used 2.5 hours, but 3 is preferable, especially if one also wants to have a discussion afterwards).

ROUND 1: IT’S IN THE DETAILS: MAKING THE STRANGE FAMILIAR

This first round will seem the most familiar to archaeologists and material culture specialists, as in the beginning it roughly follows strategies of traditional descriptive analysis. It will however, have a very different goal than formal classification. This is the most intensive and time consuming round, and also a warming up for the more creatively challenging and imaginative parts that follow. The object on the table is passed around and each turn the participant has to list a unique feature of the object that has not been mentioned before. The group should take at least an hour to do this. This might seem tedious, and there will be a certain moment when nobody thinks they can list anything anymore, but after this moment passes, a thousand more details suddenly appear, making the exercise really rewarding. It is a matter of taking time and force oneself to the art of looking for details and more details. For an archaeologist already trained in studying objects in detail it is therefore an especially interesting exercise. We noticed that the first couple of times the object was passed around, the archaeologists in the group very much relied on their knowledge of archaeological description (mentioning inclusions, shape, fabric, etc.). However, as these options dried out, they were forced to look beyond the categories of formal description and many more details surfaced (small scratches, patches, colour variations, a certain roughness or smoothness in particular parts, etc.). An alternative additional exercise, which can be incorporated in this round, also rooted in archaeological practice, is the drawing of the object (we did not, however, due to time constraints). Drawing or sketching, as any archaeologist knows, is a different way of kinaesthetic and multimodal observation that can generate knowledge through performance (Goldschmidt Citation1991, pp. 123–143, McFadyen Citation2011, p. 33–43, Wickstead Citation2013, pp. 549–564). Many details of the object will reveal themselves through drawing that would otherwise go unnoticed.

Multi-sensorial Observation

Very important to explicitly incorporate in the exercise (as it is easily overlooked) are the use of other senses beyond the paradigm of vision. Despite the name, slow looking is in its essence a multisensory endeavour. The observation in the art of slow looking is not just about sight, but about trying to take into account all the bodily sensations and affective responses activated in the process of seeing something, and to allow for non-discursive constituencies of experience (Tomkins Citation1963, Halsall Citation2004, pp. 103–122, Hemmings Citation2005, p. 552). In order to stimulate a multi-sensory observation, you can make a specific round within this first part about describing for instance what the object sounds, tastes, or feels like. This can of course be done by straightforwardly trying to make sounds with the object, touch the material or taste it and describe that taste, but a multisensorial description should ideally also include a more imaginative and synaesthetic approach (see Campt Citation2017) in order to really cut loose from western empiricist sensorial observation. This, for example, includes connecting aspects of the object such as colour, fabric, shape, or material to certain flavours, sounds or other sensations (such as, ‘the thick brown glaze on the bowl tastes like caramel’ or ‘the upper part of the bowl sounds like a church bell’).

Aesthetic Appreciation of the Imperfect

The Japanese tea ceremony is not just about the details and inimitable features, but also about valuing the object’s unique imperfections. In The Book of Tea Okakura proclaimed that the Way of Tea was essentially a worship of the imperfect or the rejection of perfection, ‘as it is a tender attempt to accomplish something possible in this impossible thing we know as life’ (Okakura Citation1906, p. 35–52, Sōshitsu Citation1998, p. 160). I think that for any archaeologist, ceramic-, or material culture specialist, this is an interesting perspective to engage with. According to Yanagi, Japanese who love tea bowls will automatically turn over the bowl to check its raised foot, which is generally unglazed and rough, and regard this as a source of unequalled pleasure. This holds especially true for areas where the glaze is thin and uneven, which is called kairagi (sharkskin), and this appreciation connects to two very important principles in Japanese aesthetics: roughness and quiet appreciation (Yanagi Citation2019, pp. 162–163). Therefore, it is worthwhile to devote one round in this first part to not just ‘plain’ description and observation, but to ascribing aesthetic pleasure to the features and imperfections of the object as well. Name details that you find really stunning, scary, or beautiful for instance, or that in any way aesthetically move you. This part will create a personal aesthetic relationship with the object. Moreover, as aesthetics and the quiet appreciation of the imperfect are eradicated from formal description (for the reason of being subjective), being forced to engage with this is a good first step in disrupting the western empirical gaze.

This round has a threefold practice: firstly, to train ourselves in how aesthetic knowledge can be integrated in object practice, secondly, a training in the art of detailed and slow looking, and thirdly, a familiarizing with an object to an extent that the details are not just known, but become intimate and unique characteristics. Through this, the object becomes known on a personal level and the participants become a group possessing this unique knowledge. We can learn from chanoyu, not through cultural appropriation, but through the way of looking, which is able to playfully decentre the empiricist gaze and create a sense of familiarity through performance.

ROUND 2: VANTAGE POINTS I MAKING THE FAMILIAR STRANGE

As we also need to practice in different vantage points, the second round opposes the personal relationship just established by de-familiarizing the object. Each participant has one turn and has to say, describe, and argue what ‘else’ this object is. If not (in our case) a brownish glazed ceramic vessel, what is it? This takes some creative effort and because it is such a departure from normal scientific analysis, it was experienced as one of the more difficult rounds in the exercise. With our brown glazed pot, the participants came up with many creative examples, and compared the object to a gas planet, a forest, and a seat for rabbits amongst others. The de-familiarization process encourages making more imaginative comparisons, but without relying on archaeological classification schemes. Each participant had to start by saying: ‘this object is like a … ’. In the case that participants struggle to come up with something, the instructor can also give them something to start from (‘this object is like a phone booth/house/bird’; anything that is completely unrelated to the objects form) to stimulate the participants’ imagination. This also has an accompanying benefit in forcing the participants to describe the object from a radically different vantage point that is far removed from their own framework.

ROUND 3: VANTAGE POINTS II: SEEN FROM OTHER WORLDS

This round is meant as a further and more constructive de-familiarization process, grounded in philosophies of perspectivism, alterity, and ontological difference. It helps to shake up the empiricist perspective that we usually take for granted. A move also known from anthropological practical research strategies in order to intentionally distance oneself from everyday assumptions (Tishman Citation2018, p. 59). The vantage points can be both chosen to stimulate different human perspectives, but also non-human views. In the experiment, we chose to do a round where each student embodied a different predetermined point of view and had to describe the object from that perspective. Viewpoints selected were: a child, a tree, a scientist, a factory worker, a landscape painter, an art buyer, and the table the object was standing on. However, vantage points can also enact an ontological turn itself: one can also decide to make a round about looking at and describing the world when the object is in fact a god, an animal, etc. Or, one can decide to let the object speak and describe the table or the room from the point of view of the object itself.

This round is one of the most important with regards to the ontological turn in action, as an attempt is made to actually ‘perform alterity’ by creating room for embodied empathy and an understanding for ontological difference. It is not about acting out the cultural reality of specific worldviews, or about the projection, but about trying to cut oneself loose from normalized frameworks and from institutionalized western empirical descriptions. What this part will hopefully achieve in the end, is to demonstrate the limits of scholarly formal object analysis, but also to naturally open up broader possibilities of post-human understanding. For this reason, this object-analysis carries significance beyond learning about biases and the limit of our own perception. After this round is finished or after the exercise is done, it therefore might be worthwhile to discuss how to incorporate the ideas on vantage points in academic practice and how it can be linked to the intellectual debate on post-human approaches and the ontological turn. How does the pot-world or the table-world relate to theories of perspectivism and alterity as encountered in academic literature? When used for research, a direct link with the archaeological context can be made to discuss how the impact of the Other is reflected and how this relates to past contexts in different ways. I evaluate this further in the discussion section.

ROUND 4: EMBODIMENT MAKING THE STRANGE FAMILIAR AGAIN

The next round is meant to bring the object back to our own human corporeal world and way of understanding. In two or three rounds, all the participants have to ascribe body parts to the object. Again, this can be done for any object, but for a bowl this is initially remarkably easy, as it already has many body parts linked to human anatomy. It has a neck, body, shoulders, etc. Therefore, like the first description phase, multiple rounds are recommended to force participants to move beyond the known frameworks.

However, it could be observed that the participants, being warmed up in the previous rounds in different ways of looking and after two hours of interaction with the object from a great variety of vantage points, started to see body parts outside of the standard formalistic framework very quickly. They did not just describe shoulders, but hanging shoulders, and ‘a protruding belly (‘from a middle aged man that drank too much beer’), and they also described things such ‘suspenders’ and freckles in the object’s decoration patterns. Some of the participants were able to describe in detail the character and personality of the bowl and its personal background story.

ROUND 5: SPIRIT

This is the last round, meant to conclude the exercise and to end the ritual in a playful way. Like the ōtsubo that sometimes became so revered that it got a name (such as Chigusa), the group had to decide on a name for the object. After the hours we spent with the object, not only having obtained intimate knowledge of its physical details, vantage points, and making personifications in different ways, it was interesting to observe how effortless the name giving part of the ritual was. One of the students declared his name was Herbert (as they thought he was ‘a typical Herbert’), and everyone instantly agreed. It seemed to be not so much a deliberated decision as it was a natural conclusion from adding up the object’s characteristics and appearance. The object gradually and instinctively received a spirit within the process of slow looking. In the end, all the participants seemed to possess intimate knowledge on Herbert’s personality and after the experiment (when the object received an honorary place, first as an exhibit and later in the graduate office); people kept referring to it as Herbert instead of a vase. Of course, it seems that Herbert’s name and personality are derived from existing (western) ontological frameworks that have been activated again in this and the previous round, but as long as such things are made explicit after the exercise, this is not problematic. It will actually add to the discussion on ontological difference and western empirical bias, as these two rounds show that ‘we’ are very capable of animism, and that spirited objects are an inherent part of the western world as well, even if we want to dismiss such things in scientific analysis. It is about bringing the ‘different’ in connection to the self.

ROUND 6: CELEBRATION

This round is optional in the case the group wants the exercise not only to be a creative philosophical assignment, but have an extra artistic component as well. It is also inspired by the chanoyu practice, and concerns the artistic production surrounding the chatsubo. As was mentioned, the utensils were not only named, a whole artistic production emerged around them. They were celebrated in poetry and writing, and therefore the last optional exercise is to write a poem praising and commemorating the object (this is of course not only present in chanoyu ritual, the ancient Greek and Byzantine practice of Ekphrasis shares such performances and could work as an inspiration, see Baghrani Citation2014, pp. 191–216). The round can be executed in a variety of ways: each participant can write a haiku or small poem, or it can be made into a group effort by writing a poem together or a homework assignment in case it is part of a lecture. In whatever way this is done, it can be regarded as a fun creative addition and way to memorize the session. In our case, we wrote a poem that summarized the exercise, and in the end, we displayed the bowl as Herbert in the common room of the Joukowsky Institute ().

DISCUSSION: PERFORMING ALTERITY

In this part, I evaluate and reflect on the exercise with the purpose of connecting it to wider debates in archaeological and anthropological theory and to matters of pedagogy. In its simplest form the exercise was about stretching our frameworks, about a more radical way of reimagining object observation: not a replacement of formal object analysis, but rather an addition to it. However, it also had a larger ambition aimed at thinking otherwise and making an attempt in performing alterity. The object analysis can be regarded as a more accessible, non-discursive, and embodied way to engage with anthropological theory. In this way, non-discursive exercises such as these can help us obtain a different understanding of what alterity is. I believe therefore, that there is more to gain from this exercise than just an object-related classroom or pastime activity. Some of these have already been mentioned in the part on slow looking and the exercise itself. However, I want to discuss a few additional observations that emerged from playing.

The main advantage for archaeologists has been touched upon already and revolves around the breaking away from formal object observation. Of course, formal analysis should not be discarded, as it has a clear use of creating replicable and comparable outcomes. It is however unable to capture the complexity of past use and experience. There are a couple of points in which the current limitations appear most poignantly: its focus on classification, its western bias, the privilege of sight over other senses, and the lack of perspectives other than empiricist. To overcome this, the exercise tried to directly challenge the intellectual position of visual hegemony by stimulating aesthetic and multisensorial ways to approach objects. This particular emphasis on multisensorial approaches is of course not new, and has been discussed both for archaeological practice as well as well as for object engagement in museum contexts (among many see for instance the contributions in Day Citation2013, Hamilakis Citation2014, see Levent and Pascual-Leone Citation2014, for museum contexts). What is new here is the active element and different vantage points combined with the incorporation of ideas inspired by perspectivism, performativity, and aesthetic practices.

Of course, the exercise does not replicate any real-world experiences and also does not create nor present a different ontology, but the environment it produces opens up possibilities to other realities and worlds. Worlds in which – as we know from research dealing with perspectivism – the whole idea of ‘interpreting’ is sometimes different (non-symbolic or non-linguistic for instance: Viveiros de Castro Citation1998, p. 469–488, Kohn Citation2015, pp. 311–327). For this reason, I want to point out two additional gains of the exercise. Firstly, the general purpose of the ontological turn is to make a move towards ontological self-determination and multi-naturalism, but it is difficult, maybe even self-contradictory, to try to communicate this through academic writing, as it requires a language that is fully immersed in western epistemology. Creating non-discursive knowledge is therefore an important improvement for anyone who wants to engage with the ontological turn seriously. Furthermore, from a pedagogical point of view most of the written theory is dense, abstract, and imbued with a considerable amount of confusing language (often caused by the scholars’ attempts to break from restraining academic language). By performing alterity and practicing de-centring perspectives, we become able to not just read, but relate to the theory; subsequently making the readings on perspectivism and new-materialism actual.

Secondly, the embodiment is only part of this understanding, because the object-analysis is also potentially able to be an intellectual stimulant by becoming a world itself during the game (as they also did in Japanese metaphysics). What games or exercises such as these can shape is a temporary realm that even though it falls apart when the exercise ends, is an intellectual totality creating something more enduring. It has its own language, jokes, emotional affect, performance, and reality, which can be referred to through the power of memory and association. During the exercise, the object becomes a centre to which one can attach each new thing one learns, every new perspective, adding a layer every time the object goes round. In this way, it creates a context in which one can understand each of these new things and through which one can articulate what one sees, thinks, and makes of it. As Rancière remarks (with the book Telemaque as example), this is one of the principles of universal teaching, where learning is focused on one single thing and relates everything else to it (Rancière Citation1991, p. 20).

A next observation, deriving from rounds five and six, was that the ritualized part of the assignment could be a way to theoretically illustrate how agency in terms of animated or spirited objects emerges and how naturally this can happen in a group context. Most of the (anthropology) students have already read a lot of literature on spirited objects, animism, and ritualization, but often these are still regarded as strictly foreign and sometimes even exotic aspects of culture (emphasized by the available literature itself): a non-western ontology. This exercise shows that we can all create spirit-objects in a group- and play setting and that it is not a non-western phenomenon at all. As mentioned, there is already a component of anthropomorphization incorporated in the language we use to describe objects; seen for example in common pottery description, but assigning personal characteristics (even though based on a human ontology) and a personality to the object in the game occurred equally naturally. It seemed that for those involved, it became almost impossible to turn the pot back into an object, as everyone kept calling him Herbert. This endorses an important anthropological and psychological thesis, that we all possess the possibility of animism (notably Bird-David Citation1999, p. 67–91, Ingold Citation2006, p. 9–20, Citation2013b, pp. 734–752, see also Harvey Citation2006, Praet Citation2013). We all have kinship with the living world (Hogan Citation2013, p. 17–18) and although cognitive imperialism was a powerful force in eradicating animism in the West, the potential is still there and can be activated. It is internal to the workings of such rituals and subsequently touches upon what effect it has on the perception of objects and group-formation.

This last note leads to a specific observation that could be made with regard to the exercise and its ritual context. Another quite interesting effect that the exercise created could be observed right after the naming ceremony. I discovered that the knowledge shared between the group members also created a sort of group bonding in the sense that all members now shared a unique piece of knowledge and experience through the ritual. Not only is this an example of ‘participatory knowing’ as described by Dewey, this observation made me very aware of how such rituals could have worked in relation to group formation, such as with the highly esteemed experts in the chatsubo-ritual who were able ‘to hear with their eyes’. As a group, we were able to see something in a common object that nobody else knew or saw before. Such an embodied ritual and sharing of knowledge leading to the formation of a group identity has been described in anthropology of course, such as in the symbolic construction of community described by Cohen (Citation1985), to name one example. The object-experiment confirms how easily and naturally this happens in relation to the anthropomorphization processes in rituals. Next to the practice in different human and non-human vantage points, understanding of ritual expert experiences are also an example of the ontological turn in practice, as they are concrete performances of alterity in objects, in our surroundings, and in ourselves.

I want to end the discussion by making a connection back to the broader principles of Slow Archaeology as they were discussed in the beginning of this article. How is this exercise relating or adding to ideas of speed, privilege and responsibility? Aside from the attention to difference and care for details, and in line with the more political aspects of Slow Archaeology, the vantage points are not just important to understand or experience forms of perspectivism and alterity in an academic sense. The exercise also tries to stimulate empathy in different ways and a further debate on existing difference relating to injustices is possible by drawing to socially diverging vantage points. Through radical difference, we can try to see the others and the forgotten. In this way, the exercise has the potential to lead to a more embodied and principled thinking about the challenge of otherness in the everyday world. Through the inclusion of empathy, slow looking can potentially add to transformative education as social change (Guajardo et al. Citation2008, p. 3–22). In addition to this, the idea of shaking the system by stimulating other types of knowledge as a critical form of pedagogy, is important to re-state, in this case as a form of emancipation (Rancière Citation1991, Hooks Citation2003, Giroux Citation2020). With this I mean that including non-discursivity in education is a form of emancipation, as it draws from a more diverse and inclusive knowledge system, not one that needs to be top-down ‘instructed’, but one that is created bottom-up, focusing on existing creativity and intuition instead of reciting academic literature and language. This emancipation has, in a very small yet important way, potential to affect Shama’s ‘fibers’ and power dynamics in academia. For this reason it should come as no surprise that alterity should find more resonance in our teaching as well (McCarty et al. Citation2005, Barnhardt and Kawagley Citation2005, p. 8–23, Cobb and Croucher Citation2020).

CONCLUSION

This article was meant to introduce a way of incorporating slowness and the ontological turn into object analysis, and can be used both as a teaching exercise, as well as a different tool for research and observation. By looking slowly, or attempting to hear with the eyes, we are not aspiring to a different way of describing how the world works, but to decentre our own western empirical frameworks and try to become aware of the limitations of those frameworks when trying to interpret objects. By forcing participants to employ different vantage points and different ways of looking, the exercise can be a helpful first tool in playfully starting to think about difference and alterity. Through this, we might be able to ask different questions to our material or reach new insights on ancient object-use, performance, and perception. Alternatively, it might help archaeologists with the difficult but important task of uncovering and experiencing the impact of ancient concepts and indication of ontologies through objects. For this reason, it can form an additional instrument to the formal object analyses already practiced in archaeology as well as be a more embodied way of learning about archaeological theory and alterity.

DECLARATIONS

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript, the author has no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Beth Whitlock, Anna Soifer, Rachel Kalisher, Sarah Bell, Amanda Brynn, Nidhi Bhaskar, Evan Levine, and Carl Walsh who made this all happen and especially to Sarah and Anna and Lennart Kruijer for their further insightful comments on the article. Thanks to Yannis Hamilakis who pushed me to write this article and supplied me with many useful suggestions and to Benjamin Alberti for his encouragement and his very valuable comments on how to improve this article. I also want to express my gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers and the Editorial Board for their extremely useful and detailed feedback. Many thanks to Herbert.

Notes

1. Ferriss’ 2009, The 4-Hour Workweek.

REFERENCES

- Ahmed, S., 2012. On being included: racism and diversity in institutional life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Alberti, B., et al. 2011. “Worlds otherwise”: archaeology, anthropology, and ontological difference. Current Anthropology, 52 (6), 896–912. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/662027

- Alberti, B., 2016a. Archaeologies of risk and wonder. Archaeological Dialogues, 23 (2), 138–145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203816000179

- Alberti, B., 2016b. Archaeologies of Ontology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 45 (1), 163–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102215-095858

- Baghrani, Z., 2014. The infinite image: art, time and the aesthetic dimension in antiquity. London: Reaktion Books.

- Barnhardt, R., and Kawagley, A., 2005. Indigenous knowledge systems and Alaska native ways of knowing. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 36 (1), 8–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.2005.36.1.008

- Battle-Baptiste, W., 2011. Black feminist archaeology. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

- Bertelsen, C.E., and Bendixsen, S., eds., 2017. Critical anthropological engagements in human alterity and difference. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Bird-David, N., 1999. ‘Animism’ revisited: personhood, environment, and relational epistemology. Current Anthropology, 40 (S1), 67–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/200061

- Breeze, M., Taylor, Y., and Costa, C., eds., 2019. Time and space in the neoliberal university: futures and fractures. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Campt, T.M., 2017. Listening to Images. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Caraher, W., 2019. Slow archaeology, punk archaeology, and the ‘archaeology of care’. European Journal of Archaeology, 22 (3), 372–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2019.15

- Carrier, J.G., ed. 2018. Economy, crime and wrong in a neoliberal era. New York, Berghahn Books: EASA Series.

- Case, A., and Deaton, A., 2020. Deaths of despair and the future of capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ceraso, S., 2014. (Re)Educating the senses: multimodal listening, bodily learning, and the composition of sonic experiences. College English, 77 (2), 102–123.

- Chatterjee, P., and Maira, S., eds., 2014. The imperial university: academic repression and scholarly dissent. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Cobb, H., and Croucher, K., 2020. Assembling archaeology teaching, practice, and research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cohen, A., 1985. The symbolic construction of community. London: Routledge.

- Day, J., ed. 2013. Making senses of the past: toward a sensory archaeology. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Descola, P., 2011. Beyond nature and culture. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Dewey, J., 1934. Art as experience. New York: Berkley Publishing Group.

- Dewey, J., 1938. Experience and Education. New York: Touchstone.

- Flexner, J., 2020. Degrowth and a sustainable future for archaeology. Archaeological Dialogues, 27 (2), 159–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203820000203

- Fraser, N., 2013. Fortunes of feminism: from state-managed capitalism to neoliberal crisis. New York: Verso Books.

- Giroux, H.A., 2020. On Critical Pedagogy. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Goldman, A., 2006. There are no aesthetic principles. In: M. Kieran, ed. Contemporary debates in aesthetics and the philosophy of art. Oxford: Blackwell, 299–312.

- Goldschmidt, G., 1991. The dialectics of sketching. Creativity Research Journal, 4 (2), 123–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419109534381

- Graham, S., 2017. Electric archaeologist [online]. Available at: https://electricarchaeology.ca/2017/03/20/slow-archaeology. [ Accessed May 2020]

- Grosfoguel, R., 2013. The structure of knowledge in westernized universities: epistemic racism/sexism and the four genocides/epistemicides of the long 16th century. Human Architecture, 11 (1), 73–90.

- Guajardo, M., Guajardo, F., and Casaperalta, E., 2008. Transformative education: chronicling a pedagogy for social change. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 39 (1), 3–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1492.2008.00002.x

- Halbmayer, E., 2012. Debating animism, perspectivism and the construction of ontologies. Indiana, 29, 9–23.

- Hall, G., 2016. The uberfication of the university. Minneapolis (MN): University of Minnesota Press.

- Halsall, F., 2004. One sense is never enough. Journal of Visual Art Practice, 3 (2), 103–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/jvap.3.2.103/0

- Hamilakis, Y., 2014. Archaeology and the senses: human experience, memory, and affect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harvey, G., 2006. Animism: respecting the living world. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hemmings, C., 2005. Invoking affect. Cultural Studies, 19 (5), 548–567. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380500365473

- Hogan, L., 2013. We call it Tradition. In: G. Harvey, ed. The handbook of contemporary animism. Oxon: Routledge, 17–26.

- Holbraad, M., and Pedersen, M., 2017. The ontological turn: an anthropological exposition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (New Departures in Anthropology).

- Hooks, B., 2003. Teaching community: a pedagogy of hope. New York, London: Routledge.

- Ingold, T., 2006. Rethinking the animate, re-animating thought. Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology, 71 (1), 9–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00141840600603111

- Ingold, T., 2013a. Making: anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture. New York: Routledge.

- Ingold, T., 2013b. Dreaming of dragons: on the imagination of real life. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 19 (4), 734–752. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12062

- Kawagley, O., 2006. A Yupiaq worldview: a pathway to ecology and spirit. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

- Kieran, M., 2013. Aesthetic knowledge. In: D. Pritchard and S. Bernecker, eds. Routledge companion to epistemology. London: Taylor and Francis, 369–379.

- Koch, M., 2012. Capitalism and climate change: theoretical discussion, historical development and policy responses. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kohn, E., 2015. Anthropology of ontologies. Annual Review of Anthropology, 44 (1), 311–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214-014127

- Kress, G., 2010. Multimodality: a social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London: Routledge.

- Levent, N., and Pascual-Leone, A., eds., 2014. The multisensory museum. cross- disciplinary, perspectives on touch, sound, smell, memory, and space. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Liitschwager, D., 2012. A world in one cubic foot, portraits of biodiversity. Chigaco: Chicago University Press.

- McCarty, T., et al. 2005. Editors’ introduction: indigenous epistemologies and education: self-determination, anthropology, and human rights. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 36 (1), 1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.2005.36.1.001

- McFadyen, L., 2011. Practice drawing writing object. In: T. Ingold, ed. Redrawing anthropology: materials, movements, lines. Farnham: Ashgate, 33–43.

- Morgan, C., 2015. Punk, DIY, and anarchy in archaeological thought and practice. Online Journal of Public Archaeology, 5, 123–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.23914/ap.v5i0.67

- Mountz, A., et al. 2015. For a slow scholarship: a feminist politics of resistance through collective action in the neoliberal university. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 14, 1235–1259.

- O’Donnell, J., Jones, B., and O’Donnell, M., eds., 2017. Alternatives to neoliberalism: towards equality and democracy. Bristol: Polity Press.

- Okakura, K., 1906. The way of tea. Reprint, Rutland and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company. 1956.

- Parr, A., 2013. The wrath of capital: neoliberalism and climate change. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Perec, G., 1975. Tentative d’épuisement d’un lieu parisien. Le pourrissement des sociétés, special issue of. Cause Commune, 1 (936), 59–108.

- Pink, S., 2011. Multimodality, multisensoriality and ethnographic knowing: social Semiotics and the phenomenology of perception. Qualitative Research, 11 (3), 261–276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111399835

- Polanyi, M., 1966. The tacit dimension. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

- Praet, I., 2013. Animism and the question of life. London and New York. Routledge.

- Rancière, J., 1991. In: K. Ross, Translated, with an introduction by. The ignorant schoolmaster: five lessons in intellectual Emancipation. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

- Rathbone, S., 2017. Anarchist literature and the development of anarchist counter- archaeologies. World Archaeology, 49 (3), 291–305. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2017.1333921

- Rizvi, U.Z., 2016. Decolonization as care. In: C.F. Strauss and A.P. Pais, eds. Slow reader: a resource for design thinking and practice. Amsterdam: Valiz, 85–95.

- Rizvi, U.Z., 2019. Archaeological encounters: the role of the speculative in decolonial archaeology. Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, 6 (1), 154–167. doi:https://doi.org/10.1558/jca.33866

- Said, E.W. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books Series

- Sharma, S., 2014. In the meantime. temporality and cultural politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Sibley, F., 1959. Aesthetic concepts. Philosophical Review, 68 (4), 421–450. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2182490

- Sōshitsu, S., 1998. The Japanese way of tea: from its origins in China to Sen Rikyū. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Stengers, I., 2018. Another science is possible: manifesto for a slow science. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Surak, K., 2013. Making tea, making Japan: cultural nationalism in practice. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Tishman, S., 2018. Slow looking: the art and practice of learning through observation. New York: Routledge.

- Todd, Z., 2016. An indigenous feminist’s take on the ontological turn: ‘ontology’ is just another word for colonialism. Journal of Historical Sociology, 29 (1), 4–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/johs.12124

- Tokugawa, Y., 1982. Chatsubo (tea jars). Vol. 2, Kyoto: Tankõsha.

- Tomkins, S., 1963. Affect, imagery, consciousness vol ii: the negative affects. New York: Springer Publishing.

- Viveiros de Castro, E., 1998. Cosmological deixis and Amerindian perspectivism. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 4 (3), 469–488. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3034157

- Viveiros de Castro, E., 2012. Cosmological perspectivism in amazonia and elsewhere. four lectures given in the department of social anthropology,Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Hau Masterclass Series Volume 1. February–March 1998.

- Viveiros de Castro, E., 2015. Who is afraid of the ontological wolf? some comments on an ongoing anthropological debate. Cambridge Anthropology, 33 (1), 2–17.

- Walker, M.B., 2016. Slow philosophy, reading against the institution. London-New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Watkins, J., 2001. Indigenous archaeology: American Indian values and scientific practice. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

- Watsky, A.M., 2013. Representations in the nonrepresentational arts: poetry and pots in 16th-century japan. Impressions, 34, 140–149.

- Watsky, A.M., 2018. Hearing with the eyes: tea, aesthetics, and the senses in sixteenth-century Japan, lecture presented Oct 4th at Brown University’s Department of the History of Art and Architecture during the annual lecture series on ‘The Sensory’.

- Watsky, A.M., and Cort, L.A., 2014. Chigusa and the art of tea. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery: Smithsonian Institution.

- Wickstead, H., 2013. Between the lines: drawing archaeology. In: P. Graves-Brown, R. Harrison, and A. Piccini, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the archaeology of the contemporary world. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 549–564.

- Wilson, D., 2018. The Japanese Tea Ceremony and pancultural definitions of art. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 76 (1), 33–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jaac.12436

- Yanagi, S., 1989. The unknown craftsman: a Japanese insight into beauty. New York: Kodansha International.

- Yanagi, S., 2019. The beauty of everyday things. London: Penguin.