Abstract

This paper explores the use of iron in the Late Bronze Age and the earliest Iron Age (c. 1100–300 BC) in south-eastern Sweden, with a focus on the final Bronze Age and Pre-Roman Iron Age I. The aim is to study how early iron was used, valued and perceived, particularly in relation to pre-existing bronze and gold. Choosing iron for certain object types, such as dress attributes and arm rings, and in key symbols, notably the spiral, suggests an appreciation for its metallic shine and colour in contrast to bronze. This silvery lustre was in some cases exploited intentionally, and may sometimes have been associated with the moon in a celestial mythology. The lunar connection might have been accentuated by the origin of iron from bodies of water, which were surrounded by strong beliefs and were often the focus of sacrificial depositions in this period. The qualities sought after in iron during the Bronze Age–Iron Age transition were in some ways different from those appreciated later in Iron Age and historical times. It is necessary to further consider early iron in its contemporary setting without comparison to the ‘successful’ adaptation in the late Pre-Roman Iron Age onwards.

INTRODUCTION

The adaptation of iron in the Nordic area, as in many other regions, took place during the Bronze Age. The first iron in the Late Bronze Age (LBA) and early Pre-Roman Iron Age (PRIA) is commonly regarded as a minor complementary metal for small-scale household needs (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, Nørbach Citation1998, Winther Olesen et al. Citation2020). Bronze Age iron is primarily explained as a utility metal – a practical but fairly underused resource alongside the dominant bronze – even argued by some to have been an ‘unsuccessful’ innovation at this stage (Sørensen Citation1989a, Citation1989b). The breakthrough and eventual success of iron as an innovation, traditionally defined from when its functional properties gained importance as weaponry and tools (e.g. Montelius Citation1913a, p. 3, Nørbach Citation1998, p. 65), is believed to have occurred in the Late PRIA, sometime around 200 BC (Levinsen Citation1984, p. 155, Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1991, p. 125; however, see Nørbach Citation1998, p. 64). The innovation of key agricultural tools, including the iron share on ards, only appeared by the mid first millennium AD (Myrdal Citation1982).

The aim of this paper is to explore how iron was used, valued and perceived during its first centuries in circulation. Building on previous studies and syntheses of this material, we investigate its role and its relationship to bronze in the Nordic LBA and PRIA I. The classic works on the corpus of LBA metalwork have had a strong bias towards bronze (Baudou Citation1960, Larsson Citation1986, Jensen Citation1997), while contemporary finds of iron have often been left out. The two metals are rarely considered in combination. Our aim is therefore to analyse how iron – both imported and local – was appreciated and used in LBA and early PRIA societies. The transition between these periods is defined from metalwork typology, where many types of bronze objects, as well as, presumably, practices and social institutions associated with these, declined around 500 BC (Sørensen Citation1989a, Jensen Citation1997). Studying how iron was used alongside bronze can therefore provide clues regarding the wider issue of changing values of metal at this time.

The study focuses on central Sweden, which corresponds to the districts around lakes Mälaren and Hjälmaren in the south-east. This region was chosen because of well-documented and relatively frequent evidence of local production and use of iron during the latest Bronze Age and earliest Iron Age (Serning Citation1984, Wedberg Citation1984, Hansson Citation1989, Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, Strucke and Holback Citation2006). The Bronze Age–Iron Age transition is generally known as a find-poor period in this area. Funerary remains are dominated by incomplete stone-settings, small bone deposits and sparse find material. Likewise, for settlements, particularly in the early PRIA, the finds material is meagre. Depositions of bronzes in the landscape, primarily in wet contexts, are abundant in the LBA (Rundkvist Citation2015). Other depositions in water (including human and animal bodies) occurred throughout the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age (Fredengren Citation2011, Citation2015). This local study can provide a basis for comparisons, but also insights relevant to a better understanding of the adaptation of iron in a wider perspective.

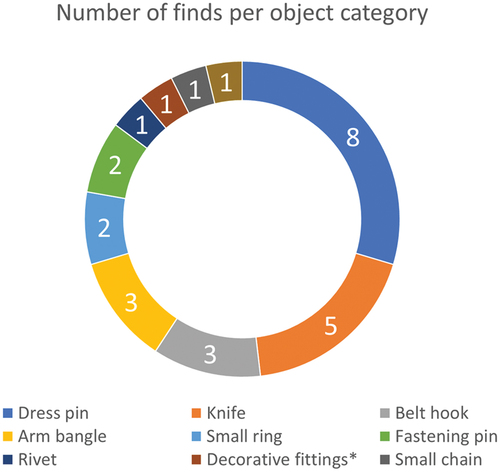

The materials under review are iron objects and bimetallic bronze–iron objects. A majority of the finds derive from either graves or landscape depositions (see ). Our analytical target is to outline the functions and roles of these objects in society c. 900–300 BC. Due to the dominance of later material the focus lies on the end of this period, LBA Period VI and PRIA I (c. 600–300 BC). Period VI and PRIA I are difficult to distinguish from each other typologically, and therefore changes and development in iron use over this time span will not be discussed. Rather than approaching this early phase of iron as a step in a long-term adaptation process, we limit this study to the specific roles of iron in society during the LBA and early PRIA.

Table 1. Iron finds from the Late Bronze Age and early Pre-Roman Iron Age in the study area (Närke, Västmanland, Södermanland, Uppland).

BACKGROUND

Archaeologists have long been aware that iron circulated in parallel to Bronze Age bronze: iron details appear on characteristic bronze objects, and some early iron objects are typological parallels to those of bronze. Earlier, some scholars advocated the idea that iron in the LBA and earliest Iron Age was a new and exclusive material, and therefore was used primarily as a luxury item in ornaments and jewellery (Montelius Citation1895, p. 164, Brøndsted Citation1959, p. 260). This view was largely abandoned as more finds emerged, proving many early iron objects to be everyday items. Montelius later argued (Citation1913b) that a widespread use of iron for details such as horse gear – rather than weapons and ornaments – indicated that iron was not rare and precious at the end of the Bronze Age.

The role and value of iron is tied to the question of its local availability. In the early twentieth century, all early iron was believed to be imported (Salin Citation1905). In the 1950s, Louise Halbert (Citation1956) argued that local iron production might have taken place in the Nordic LBA. Referring to iron chaplets integrated in bronze figurines of Nordic style, Halbert suggested that imported iron was unlikely to have been used for such minor details. However, the question of a local iron production in the LBA remained contested. As late as the 1960s Stenberger (Citation1964, p. 330) argued that iron before 100 BC was non-local, that the PRIA was a metal poor ‘Age of Wood’ and that the society was not yet ready for iron.

More recently, local production of iron in the Bronze Age has been attested from various regions within present-day Sweden. Archaeological finds of slags and furnaces demonstrate the existence of small-scale iron production from the Late Bronze Age (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, Kihlstedt Citation1998, Strucke and Holback Citation2006, and possibly, Lazarides Citation2017). Slag finds and occasional furnaces have been dated to around 900 BC onwards. The earliest known reduction furnaces from the region in focus for this paper are dated to LBA period V–VI with 925–811 BC in Sågebol, southern Närke (Kihlstedt Citation1998), 780–520 BC in Ramsberg, northern Västmanland (Grandin and Hjärthner-Holdar Citation2000, Damell Citation2008, p. 354), to the LBA-early PRIA with 810–290 BC in Smedsgården, southern Närke (Hansson Citation1989, p. 85) and a forge dated to 780–520 BC in Åbrunna, Södermanland (Strucke and Holback Citation2006, p. 26). LBA iron smelting has been documented in the vicinity of domestic settings (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a), as well as in direct relation to ore sources at a further distance from contemporary settlements (Grandin and Hjärthner-Holdar Citation2000, Karlsson Citation2003).

Iron production in central Sweden is earlier than in many other parts of the Nordic area (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, however, see also Prescott Citation1991, p. 105 for a possible LBA bloom found at Skivarhelleren, Norway). In Denmark, Norway and the Fennoscandian region, the earliest iron furnaces and reduction slags known so far date to the PRIA (Nørbach Citation1998, Lyngstrøm Citation2008, Citation2020, Larsen Citation2009, Grandin Citation2010, Simonsen and Bukkemoen Citation2015, Winther Olesen et al. Citation2020, Bennerhag et al. Citation2021). Famous early artefacts with iron details from Norway are the Vestby animal figurines of Nordic Bronze Age style with iron chaplets from a LBA Period V–VI hoard (Bjørn Citation1929, Hagen Citation1954, Rosenqvist Citation1954). The earliest iron objects known at present in Denmark are dated to 700–500 BC (Lyngstrøm and Jouttijärvi Citation2018, p. 155, Lyngstrøm Citation2020, p. 52). Although there are overarching characteristics for metalwork in the Nordic area, there are also regional differences in how metals were designed, used and deposited.

EARLY IRON FROM ‘WITHIN’

Several aspects are important to stress about the environment in which iron was first used. As Ben Roberts and Miljana Radivojević (Citation2015, p. 302) point out, the process of an innovation or adaptation needs to be seen from within, in relation to pre-existing materials, technologies, forms and qualities into which the new material is established. These include technological and cultural choices surrounding metalwork: its use, its ornamentation/iconography, its forms and aesthetics, and the ways in which its visibility and other sensual qualities were harnessed. Here, particular attention will be given to how objects acted as visual and physical articulations of social categories. Inspiration is drawn from how artefacts’ effect and ‘act’ through colours, visibility and designs, themes which have recently been explored for several periods and materials, notably in relation to costume and appearance (e.g. Bergerbrant et al. Citation2013, Martin Citation2014, Martin and Weetch Citation2017, Vedeler et al. Citation2018, Standley Citation2020). The Late Bronze Age iron featured several differences and similarities compared to other metals and alloys already in circulation. This relates primarily to bronze, but also gold, pure copper, tin and lead.

The technologies involved in making iron differ from those used to process other metals available at this time. The most striking contrast would be that of origin. Bronze, gold and tin were brought in from foreign lands as pieces or objects through exchange networks and external contacts (Ling et al. Citation2014, Melheim et al. Citation2018, however, note the possible exception of local copper slag from a contextually uncertain settlement find in Hallunda, Sweden: see Ling et al. Citation2014, pp. 119, 124). By the end of the period, however, bronze did not always come from ‘outside’, as we can assume that large quantities of metals and alloys remained in local circulation to be recycled.

Iron, by contrast, was not only acquired from foreign areas but also produced out of local sediments in rivers, bogs and lakes, and processed through direct reduction techniques in what is known as a bloomery (Englund Citation2002). During the LBA in central Sweden iron ore was almost exclusively extracted from wet environments (although sometimes also ochrous, limonitic surface soil (‘red soil’), see Wedberg Citation1984, p 155–157, Damell Citation2008). Iron ore in bogs and lakes can be identified through its colour, appearance and smell (Skogstrand Citation2021). Limonite ore may also occur in streams where iron-rich sediments accumulate after being transported from ore-rich rock formations further upstream (Hansson Citation1989, p. 76). The reworking of imported iron is always a potential source to raw material. However, iron furnaces with LBA dates indicate that at least part of the iron was made locally.

The processing of metals and the qualities of bronze and iron as materials differed greatly. Iron – in contrast to copper, tin and gold – was not cast into liquid form in northern Europe at this time, but was welded together from pieces (Lyngstrøm and Jouttijärvi Citation2018, p. 154). Iron-working entailed new processes and different transformations compared to those involved in the melting, casting and smithery of bronze, processes that had little in common (Buchwald Citation2005, p. 197). Iron working, notably the smelting of ore to produce the metal, is a completely different transformative technology that also gave rise to new metaphors and symbolism, where references to sexual reproduction and fertility have been stressed for the North European Iron Age (Haaland Citation2004, see also Giles Citation2007). Only some overlaps exist in these technologies: notably smithery, through hammering, warms metal into shapes (iron) or parts of objects into shapes (bronze), and presumably the use of forced draft via bellows for reaching high temperatures in order to melt (bronze) and reduce (iron ore). The contexts of early slags and furnaces in central Sweden indicate that the new technology was probably adopted first by bronze workers (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 182–184).

MATERIAL AND SOURCE CRITICISM

In studying the role of iron, we will assess the qualities of this metal that appear to have been valued in the LBA and early PRIA, such as colour nuance, hardness, luminousness and the visibility and appearance of iron objects when in use. Occurrences of iron will briefly be discussed in relation to cultural practices, such as on human bodies and depositional contexts.

The focus in this case study is to analyse functions, find- and use contexts and sensual properties (notably visual) of iron used in this period. Due to this focus, we make no distinction here between locally produced versus imported iron/bimetallic objects. The premise is that all iron objects in circulation were present because they appealed to the local community, either through adopting a finished, foreign object or through producing an object locally. Considering the variety of iron objects circulating in neighbouring regions that were not adopted, we see imports as indicative of conscious selection and local preferences.

The materials studied in this article are iron finds from the south-eastern Swedish mainland. This region is often termed ‘central Sweden’, and here includes the counties of Närke, Västmanland, Uppland and Södermanland. These are areas with local iron-working from Bronze Age periods IV–V onwards (Hansson Citation1989, p. 85, Citation1993b, p. 173). Finds from other regions in Scandinavia are brought in for comparison in the discussion. The compilation is based on the work of Hjärthner-Holdar (Citation1993a), who was the first to systematise and date the earliest iron finds and iron slag occurrences in Sweden. Complementary data from later discoveries of iron objects have been added. However, since it is not possible to conduct systematic searches in the Swedish report literature the list should not be seen as a full compilation (appendix).

Some important points on source criticism also need to be emphasised. Iron finds are underrepresented compared to contemporary copper-alloys. Iron is more susceptible to oxidation. In combination with the low number of iron objects known from landscape depositions, this means that iron has survived to a much lesser degree in the archaeological record than bronze. The selective and limited depositional practices in graves and landscapes have consequences in terms of representativity and have created bias. We can assume that the range of iron objects originally in circulation was broader, including items other than the ones selected for funerary and landscape deposit. The preserved glimpse offered through this data – although biased and incomplete – can illuminate some important spheres of iron use, while others will unfortunately remain hidden.

Recent studies of Danish LBA bronze razors have demonstrated cases where inlays that previously were identified as iron are actually copper covered with an iron-bearing corrosion (Lyngstrøm and Jouttijärvi Citation2018). This raises the question of potential misidentification. Traces of iron on bronze objects included in this material have not always been chemically confirmed as iron. Analyses have been performed, however, on two of the characteristic bronze–iron objects found in the study area, an iron chaplet in an LBA Period V hanging vessel from Härnevi (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 164) and iron on bronze discs from Hassle (Oldeberg Citation1952, p. 377). These two confirmed cases, and the lack of inlays similar to those from Danish razors, allow for the hypothesis that rust, or small components visible as iron, are most likely iron rather than corroded copper. Nevertheless, this is a question which would benefit from further analyses in future research.

Finally, it should be emphasised that 14C-analyses only provide limited information in this period. Radiocarbon dates are typically imprecise due to the so-called Hallstatt plateau in the calibration curve, making difficult distinctions within the time span 800–400 BC (Hornstrup et al. Citation2012, p. 18–20). Consequently, grave finds are more precisely dated when found with typologically datable bronze objects than from the results of 14C-dating. Changes in the use of iron from Bronze Age period V to the PRIA I are therefore not addressed.

EARLY IRON IN THE STUDY AREA

Iron objects and bimetallic objects with iron from the LBA and early PRIA in the study area comprise 40 or 41 objects from 21 different sites (, also see appendix). The chronological span covers the 500–700 years of iron use from the first occurrence of iron finds in period III/IV up until the mid PRIA (). Among the oldest iron finds in the region are a possible awl from a period III–IV burial (no 6 in the appendix), a small ring from a mound of fire-cracked stones with dates to LBA period IV–V (no 11 in appendix) and two unidentifiable iron objects recently found in graves dated to LBA period IV and period IV–V, respectively (Hed Jakobsson et al. Citation2021, p. 67).

Datable and identifiable iron objects have primarily been found in graves and depositional contexts. The material consists of corroded iron objects and iron rust on bronze objects. Iron finds from settlement contexts – often fragmentary and recovered from miscellaneous cultural layers – are more difficult to date, and almost all such finds have therefore been omitted. For similar reasons, not all grave finds listed by Hjärthner-Holdar have been included. This concerns finds from contexts of very uncertain date. We have also left out corroded iron finds where the original object type is no longer recognisable, as context, function and appearance are key to this study. The total range of iron objects known from the LBA – early PRIA from neighbouring regions of Sweden thus includes more types than listed here (see Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 177).

The artefacts have been divided into eight broad categories.

1. Small cutting and piercing tools: The material includes six knives or knife fragments of iron, all but one found in graves with a date range from Period V–PRIA I. The material also includes one possible awl, found together with a double button from Period III/IV in a burial. If the button reflects the date of the deposition, this would be the oldest iron find included from the area.

2. Small dress attributes: in the form of seven clear and two uncertain dress pins and two clear and one uncertain belt hook. In this category, we also include the small fragment of an iron chain with unknown function, found in a grave with an iron knife and a bronze dress pin in Åsen, Västmanland. Belt hooks with spiral ends are rare but form a distinct type, stylistically relating to the bronze hooks with spiral ends from period V, and known in three other cases from southern Sweden (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 176).

3. Small support items: two c. 4–5 cm wide rings of unknown function, probably for suspension. A belt ring is another suggested interpretation (e.g. Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 131). Equivalents in bronze are known from the LBA, sometimes used for suspending razors and tweezers (e.g. SHM 7571:173). Corrosion makes it difficult to assess any traces of wear on these iron rings.

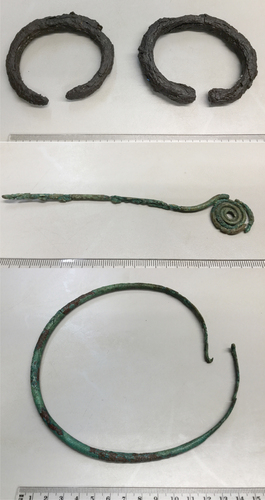

4. Body attributes/jewellery: three massive arm rings or arm bangles have been found in the region. Two of these, from Tibble, Uppland, were found together with a spiral-headed pin and a neck ring of bronze (Modin Citation1966, see The other find from Söderby, Uppland, contained one iron bangle and fragments of a bronze ring from Period VI, possibly another arm ring (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 166). In both cases, the iron arm rings appear to have formed parts of sets including two rings.

Bimetallic objects with iron in this dataset include:

5. Rivets: one iron rivet has been identified in the study area on a foreign bronze sword from Kråkenäs, Svärta, Södermanland, dated to LBA Period V. The iron rivet is probably a secondary addition, and the sword appears to be composed from two pieces originally belonging to different weapons (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 151–152).

6. Pins on the back of brooches (or rusty traces of such pins): are seen on the two bronze disc-shaped brooches with concentric circles deposited by a boulder in Ransten, Södermanland. Similar cases with rust or remaining parts of iron pins have been found on the back of other, disc-shaped bronze plates from Helgö, Småland (SHM 9041:21), Bunna, Gotland (SHM 8191:10 and 11), Triberga, Öland (SHM 9321) and Bäckaryd, Scania (SHM 8762).

7. Casting chaplets: identified on one belt dome from period V in the mixed hoard from Härnevi, Uppland. Casting chaplets of iron are also known in the bronze animal figurines from the Norwegian Vestby hoard, Hadeland (Hagen Citation1954, Rosenqvist Citation1954).

8. Decorative fittings on ornamental plates: partially preserved iron details on 12 disc-shaped ornaments in a hoard from Hassle, Närke. The discs have had boss-shaped central rivets and mounts around the outer rim of the front of each plate. These objects lack any direct parallels.

Grave finds account for most of the small cutting tools, support items, dress and body attributes while iron items in depositions are bimetallic objects with iron details on large bronze objects like swords and ornamental plates (see ). Unlike bronze or bimetallic objects, iron objects were generally not left under boulders, in rivers, lakes and other places in the landscape as sacrifices. There is, however, one exception to this pattern: an ‘imported’ full-length iron ‘Hallstatt sword’ of Mindelheim type, dated to Period VI (Jensen Citation1989), found under a stone slab by Sjögerstad in the neighbouring region of Östergötland (SHM 11299, Oldeberg Citation1952).

DISCUSSION: THE ROLE OF IRON IN THE BRONZE AGE AND EARLIEST IRON AGE

The Bronze Age iron in central Sweden will here be discussed in relation to two main themes: (1) early iron use and the role of this metal in the LBA–early PRIA society compared to the views in previous research and, (2) the values of iron seen in relation to the wider LBA-PRIA world-view, including colour symbolism, animate landscapes and mythological associations.

FUNCTIONS, CONTEXTS AND PRACTICES

Since the late twentieth century, early iron in Scandinavia has primarily been emphasised as a pragmatic, secondary metal for repairs, small tools and small jewellery (Halbert Citation1956, Sørensen Citation1989a, Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a). The complementary role of Bronze Age iron has been explained from different perspectives. Based on Danish materials, Levinsen (Citation1984) argued that the earliest iron was a rare status material, while Sørensen (Citation1989b, p. 465) claimed that its minor role in relation to bronze meant it was not ‘ascribed any particular values during the Bronze Age’. Sørensen (Citation1987, p. 92, Citation1989a, p. 465, Citation1989b) further suggested that the limited use of iron was a consequence of the strong cultural preference for bronze. The dominant role of bronze in social and ritual communication made iron irrelevant. She argued that iron in the Nordic Late Bronze Age can be seen as a ‘suppressed’ innovation at this stage, used ‘without having any distinct consequences or impact’ (Sørensen Citation1989b, p. 186).

By contrast, studying Swedish iron artefacts and early remains of iron metalworking, Eva Hjärthner-Holdar (Citation1993a, Citation1993b) later argued that iron was used for a variety of purposes and was an important addition to the ‘flora’ of available metals. In her view, iron should be understood as a cleverly harnessed innovation, primarily as a minor ‘utility metal’ used as a complement to bronze (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, Citation1993b). The potentials and properties of iron appear to have been well known, based on its use for cutting tools and chaplets in casting supports (as iron has a higher melting point than bronze). Contrary to Sørensen, Hjärthner-Holdar emphasised this as a successful adaptation of iron where ‘people had presumably well understood the potentials and advantages of this material’ (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 188, translation by authors).

The difference in empirical starting points – where Hjärthner-Holdar studied material from southern and central Sweden while Sørensen primarily discussed Danish material – could be one of the reasons differing conclusions were reached. In central Sweden, as has previously been demonstrated (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a), iron was used for many different purposes; in small tools and for repairs and eventually also in dress attributes and jewellery. Regardless of the interpretation of the role and relative importance of early iron – skilfully harnessed or irrelevant – the circumstances were clearly different from its use in later Iron Age societies when iron was more abundant. How can we understand iron in this specific context?

In the material in our study – in contrast to bronze – large, massive cult objects and dress attributes (belt plates, belt domes, spectacle fibulas) do not occur in iron, nor was it used for large, prestigious weapons (spearheads, ceremonial axes and most swords). One exception is the iron sword found in Sjögerstad, Östergötland, the only sword of iron known from this period in Sweden. While iron sword types were common in Central Europe at this time, they appear to have reached Scandinavia only rarely (Jensen Citation1989, p. 151). Apart from the Sjögerstad sword, mentioned above, we are only aware of one other iron weapon from the Bronze Age in Sweden: a symbolic miniature iron dagger with double spiral grip-end from an urn grave with Period V bronzes in Norbjär, Scania (SHM 10769:1, Stjernquist Citation1961, p. 79).

One explanation for this bias could be that large objects might have been too complex to forge in the early stages of iron technology. Another important reason is the aspect of choice, i.e. which materials were considered appropriate for what purposes. Most of the classic bronze attributes appear to have been intrinsically linked to the metal itself, as there was almost a monopoly of bronze in ritual activities (Sørensen Citation1987, p. 91–93, Levy Citation1999). Large and symbolic ornaments and weapons in the LBA Period V–VI were dominated by bronze, as were neck rings throughout the LBA and PRIA. The restricted range of objects considered appropriate for manufacture in iron can thus be revealing. These choices would have had technical, practical, functional and social reasons behind them.

Another example indicating a selective use of iron concerns tools. Chisels and socketed axes of iron have not been found in well-dated contexts attributed to this time period. A socketed axe of iron from an undated settlement context in Kumla, Södermanland, has been proposed to date to LBA Period VI, based on typological parallels to Polish axes and the character of nearby burials (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 152). However, the oldest, clearly dated iron socketed axes known to date are from the late PRIA and early Roman Iron Age (e.g. Nørbach Citation1998, p. 64, Hedeager Citation2021). One clear example from Gotland shows a socketed axe of Nordic Bronze Age type made from iron, but coated with bronze (Serning Citation1984, p. 62). The iron was thus ‘hidden’ and it would have appeared as a bronze axe. This find might suggest that iron was considered inappropriate for axes at this time.

Early iron finds in central Sweden and their position in the social topography fit with several of the previous characterisations proposed for early iron use in Scandinavia. Iron was used both as a precious jewellery metal (Montelius Citation1895, p. 164, Brøndsted Citation1959, p. 260, Levinsen Citation1984) and as a utility metal for tools and repairs (Sørensen Citation1987, p. 92, Citation1989a, Nørbach Citation1998). Furthermore, the belt hooks with double spirals, dress pins, arm rings and ornamental plates highlight the rarely discussed fact that iron also played a role as a visual element in dress, body decoration and in ceremonial contexts. We will now turn our attention to where and how this new metal was used and displayed.

IRON AS DRESS ATTRIBUTE, BODY ORNAMENT AND PERSONAL TOOL – USE AND DISPLAY

Iron was adopted for certain elements of dress but not for others. The role of metalwork attributes in appearance has been explored in more detail with regard to the Early Bronze Age (EBA) (e.g. Sørensen Citation1997, Bergerbrant Citation2007). This is due to the fact that bodies, grave goods and even textiles are better preserved in the inhumation rite that dominated in this period. The shiny, ornate, often ‘standardised’ and conspicuous ornaments and dress fittings of the EBA have been shown to have expressed and upheld social categorisation, which was tied to age, gender, roles and ranks (Sørensen Citation1997, Citation2013, Levy Citation1999, Bergerbrant Citation2007, Bergerbrant et al. Citation2013). The similarities between EBA and LBA attributes in terms of type, size and combinations allows for drawing on studies of the EBA to interpret LBA metalwork and its placement and visibility on the body and costume. While clearly inconspicuous compared to the often large and visually striking bronze attributes, those of iron – notably pins, belt hooks and arm rings – nevertheless took an active part in social categorisation. As fasteners of garments and parts of belts, iron attributes had a visible placement on the torso and waist.

Iron dress pins occur in several types from the area: swan’s neck pin, cruciform-headed pin, disc-headed pin and bow pin (appendix). All types were also present in bronze, meaning that no pin type was exclusively made of iron. Dress pins were probably mostly used to affix pieces of clothing. LBA bronze pins range from the long, large-headed pins, visible from afar, to smaller and more discreet pins (Baudou Citation1960, pp. 77–86 and figures XVI–XVIII, Jensen Citation1997, p. 163 and figures 83–83). Due to the dominance of cremation burial and the complex funerary rites during LBA-PRIA I our understanding of costume – and more generally the link between the buried individual(s) and the (often fragmented) objects in the funerary deposits – are limited. In an inhumation grave from Gotland, dated to the LBA Period VI–PRIA I transition, bronze pins were also found by the head, indicating a use in the headdress or hair (Nylén Citation1972, p. 8–9).

Turning to the question of visibility, it can be noted that the belt hooks feature double spirals, and that some pins have disc-shaped heads (). Symbolic investment in belt hooks and pins indicates they were meaningful markers in the social hierarchy. These iron objects were not hidden, but rather manifestly worn. It is possible that carrying such attributes was reserved for certain individuals, and not accessible or sanctioned for everybody in the community. Dress pins and belt hooks with double spiral ends were visually and socially differentiating. As attributes of dress they were used directly on the individual person, visibly marking and constructing aspects of their social persona, for example by means of stressing similarity/difference, signalling belonging or underlining defiance (Sørensen Citation2013, p. 218). These iron objects were designed in accordance with existing forms and symbols generally characterising bronze metalwork of the LBA-PRIA I.

Knives are the second most common iron find from this period in this area (). Like the dress pins, the iron knives correspond to the design of their bronze counterparts (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993b, p. 170). Most are found in burial contexts; presumably, these were personal tools deposited with the dead. The knowledge of how knives (bronze or iron) were handled is limited. Were metal knives used as multi-purpose tools, or reserved for specific tasks? Considering their similarity, bronze and iron knives might have been used interchangeably. Alternatively, knives of iron may have been appreciated or chosen for a perceived difference in properties or associations.

Fig. 1. Iron artefacts from the LBA and earliest PRIA recovered from the study area in central Sweden. Knives and dress pins from funerary contexts are the dominant find types.

Fig. 2. Dress pins made from iron where the same type also exists in bronze. Grave finds from Önsta-Gryta, Västmanland (SHM 31576). Photo: Sören Hallgren, The Swedish History Museum/SHM (CC BY).

Finally, there are three massive iron arm rings or bangles in the study area (). Iron arm rings from period VI are also known from Danish hoards (Montelius Citation1913b, p. 77, Jensen Citation1997, p. 157). Rings for wrists or feet were thus apparently accepted in iron, while, by contrast, neck rings are exclusively made from bronze or gold. A rare example of twisted iron neck rings of LBA Period VI type is known from northern Germany (Montelius Citation1913b, p.75–76), but is exceptional. Massive iron arm rings were visually striking attributes. As argued for conspicuous bronze attributes, they articulated certain parts of the body and visibly marked persons within a group (e.g. Sørensen Citation1997, pp. 101–104, Levy Citation1999, pp. 208–210, 214), this presumably signalled the bearer’s special social role and made public rather than private statements.

Fig. 3. Two iron bangles (top) found with a bronze pin (middle) and bronze neck ring (bottom) in Täby, Uppland (SHM 29348). Photo: Thomas Eriksson, The Swedish History Museum/SHM (CC BY).

To sum up, iron objects were used both in tools and small implements as well as for attributes in dress during the LBA-PRIA I. As dress attributes, they formed a part of the visual appearance of persons and were markers meant to be seen by others. As previously pointed out (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a), the early iron use indicates openness rather than suppression in the region under study here. Iron was appreciated for its additional qualities which added to the ‘flora’ of available metals, rather than as a replacement or equivalent to bronze (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993b, p. 165). These additional qualities in the LBA might not only have been to facilitate superior cutting tools (although steel production might have been present very early, see e.g. Buchwald Citation2005, p. 68–69, Hjärthner-Holdar Citation2009). The discussion will now turn to the implications of iron being used for aspects other than for repairs and minor tools for everyday use.

COMPOSITE OBJECTS – FUNCTIONALITY, APPEARANCE AND EFFECT

Besides hardness and sharpness, iron’s lustre, colour and similarity and difference to the shine of bronze seems to have been appreciated. Concerning bronze, a significant range of objects of the LBA clearly aimed to create conspicuous objects, exploiting the metal’s large, light-reflecting surfaces (Levy Citation1999). Together with the abundant spiral motifs, wheel-crosses and concentric circles, an explicit connection between shiny, golden bronze and the sun seems apparent (e.g. Kaul Citation2005, Vandkilde Citation2014, p. 621). Gold was sometimes used to enhance or decorate bronzes, most famously as a cover on one side of the horse-pulled ‘sun-disc’ on a cult figurine from Trundholm in Denmark. The figurine is interpreted as a representation of a central Bronze Age myth concerning the travel of the sun by day and night (Kaul Citation2004, Citation2005, Goldhahn Citation2013, p. 251). Gold, but also bronze, seems to have been associated with a celestial skyworld where the sun was a powerful element in myths and Bronze Age cosmological narrative (Kaul Citation2004). The use of iron in some spirals and circular forms is hardly a coincidence in such a meaningful universe.

Iron used on bronze appeared mostly as details and repairs, but sometimes also as decorative additions on exclusive bronze objects. Iron on composite objects includes sword rivets, brooch pins, casting chaplets and ornamental fittings. Such additions are often invisible, especially considering that they appear on large bronzes meant to be seen from a distance in public rituals (e.g. Sørensen Citation1997, p. 107–108, Levy Citation1999). One example is the small iron rivet to affix the handle on the period V sword from Svärta (Arbman Citation1934, p. 210). The rivet head would have been visible above the scabbard, but only from up close. Another ‘hidden’ example is an iron mouthpiece on a bronze horse gear set in a mixed Period VI hoard from Gotland (SHM 7994, Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 138–139). These details appear as subtle additions of a shiny metal, similar enough to appear as bronze. There are, however, some finds from the study area that challenge the interpretation of iron in all bimetallic objects as only a practical, bronze-saving solution.

A hidden but possibly meaningful placement of iron on bronze is as pins on the back of ornamental plates. Such fastening pins did not affect the visual appearance of the bronze object (). However, the importance of what was on the back-sides of these plates is indicated by symbols occurring on several such objects. An abstract human figure has been found on the back of an ornamental plate that is similar to the ones with iron pins (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 175–176). Similarly, a range of peculiar symbols feature on the back of some LBA spectacle fibulas (Oldeberg Citation1933, pp. 190–192, 216). Additions to the backs of these objects (the side that was directed towards the bearer) were therefore probably considered significant.

Fig. 4. Fastening pin on the back of ornamental plate/disc shaped jewellery of bronze from Ransten, Södermanland (SHM 13771). Swedish History Museum.

The only clear case where additions also intentionally changed the appearance of composite objects are the 12 plates with concentric circles from the Hassle hoard (SHM 21513). They are dated to the end of the Bronze Age–Earliest Iron Age and feature central iron boss-shaped rivets and iron fittings around the rim. The bronze-iron plates lack any exact parallels, and different ideas about their origin have been proposed (Arbman Citation1938, Stjernquist Citation1962, pp. 83–85, Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 149, Jensen Citation1997, p. 180). Their use-context remains uncertain. Similar decorative plates are found on horse tack, but the Hassle discs appear too large for this purpose. Traces of wood on the back of some of the plates suggest they had been mounted on a wooden structure. They were seemingly used for public display in processions or ceremonies, for example on a wagon (Stjernquist Citation1962, p. 83, Citation1971).

Unlike other bimetallic objects, the iron on the Hassle plates was purely ornamental and also must have made an impression that was visible from afar. Here, the silver-coloured iron would have created a certain contrast to the more orange-yellow-golden bronze, giving the discs a more silvery appearance (). The iron has no practical function on these discs. Hence, iron was sometimes used and appreciated for its visual quality and contrasting colour.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF COLOURS

As for the Hassle discs, a lighter, more silvery colour in metalwork appears to have been deliberately sought for certain objects. Such colour nuances can for example be accomplished through copper-alloys with unusually high tin content (Thrane and Jouttijärvi Citation2020, p. 37). Silvery details have been noted on an ornamental disc featuring a central boss-shaped rivet with high silver content and remarkably light colour from a mixed LBA hoard in Hubbo, Västmanland (Bohlin Citation1968, pp. 128–131). Four ornamental discs in a Danish hoard from Jørgensø, Funen, were also described as being of an unusually light-coloured alloy (Thrane Citation1975, p. 132). Silver colour was thus a sought-after quality for some disc-shaped ornaments.

Colour preferences as a factor in the desire to produce different alloys is a rather recent insight in Bronze Age research (e.g. Roberts et al. Citation2015, pp. 388–389, Kuijpers Citation2018, pp. 105–111, Sørensen and Appleby Citation2018, pp. 40–48, Thrane and Jouttijärvi Citation2020, p. 37). Metalwork where colours linked to myth and symbolic schema has been demonstrated in other historical contexts (Herbert Citation1984, Hosler Citation1995). Seen in relation to the symbolic connection between the golden metals, i.e. gold and bronze and the sun, its silvery colour might instead have evoked an association with the moon. Although the moon is rarely observed in mythological motifs or in LBA iconography (Kaul Citation2005, pp. 256–261), it is not too far-fetched to suggest that a society so preoccupied with the movements of celestial bodies also placed importance on the moon cycle.

In this context it is also noteworthy that the Hassle bronze-iron discs make up the total number of twelve, possibly referencing the sum of lunar appearances during a year cycle. Perceptions of time and systems for calendrical organisation in this period are elusive (although see Randsborg Citation2010 for a hypothesis and discussion in, Lund and Melheim Citation2011, p. 452), and another interpretation is that an even number allowed for an object, such as a wagon, to be symmetrically adorned on both sides. A reference to the moon in LBA metalwork has previously been suggested in relation to a necklace of tin beads from the Vestby hoard, interpreted as a lunar calendar (Lund and Melheim Citation2011). Here, too, the sum of 12 is important. Divisions of the necklace by larger beads into 12 sections have been pointed out as a possible reference to a lunar year (Lund and Melheim Citation2011, p. 452). To this observation, it could also be added that a lunar association might have been strengthened by the silvery/grey colour of tin.

In light of the fact that colour was pregnant with meaning, the silvery, shiny colour nuance of polished iron was probably important. In the Nordic area, iron was not used for inlays on bronze objects, unlike many other regions on the continent (Berger Citation2014). Inlays on a limited number of Bronze Age swords and razors in Scandinavia instead appear to be of copper (Schwab et al. Citation2010, Lyngstrøm and Jouttijärvi Citation2018). It has recently been suggested that metal objects in Bronze Age Europe relatively rarely display colour contrasts (Soafer et al. Citation2018, p. 148–149). However, in our view, the idea preferences and conscious choices regarding colour are manifest in other ways than what is immediately obvious to the modern eye. As demonstrated in relation to the Hassle discs with silvery iron fittings, appreciation of silver colour has been noted on other ornamental discs from the LBA through unusually light bronze alloys.

Even though the colour of iron may vary depending on treatment and finish, it presents a range of glows and nuances, which are different from bronze, thereby creating a contrast and ‘dialogue’ between metals. This ‘dialogue’ is most evident on bi-metallic objects, but also when considering the various metals and alloys occurring side by side in this time period.

HANDLING IRON AND BRONZE IN THE LANDSCAPE

Finally, iron differs from bronze not only in terms of appearance and manufacture but also regarding origin. The origin from local bogs and waters for at least some of the iron in circulation differentiates it from imported bronze. The source of iron ore from sweet waters, streams or bogs should be considered in relation to how such places were perceived in LBA ontology and landscape perception. Water bodies were the focus of a powerful cult and held a special ritual and cosmological status in the LBA (Fredengren Citation2011, Goldhahn Citation2013, p. 254, see also Østigård Citation2021). The ‘harvest’ of iron ore from local wetlands was probably an integral part of how early iron was perceived and valued (Carlsson Citation2001, p. 71–72).

Based on the appreciation of its silvery colour, its origin in local waters and its use in some visible objects, sometimes with spirals and circular designs, we suggest that iron came to be linked to special values and even revered in the LBA and early PRIA in central Sweden. In a value system where metals and their origins were linked to myths with celestial elements, it would be surprising if iron was adopted without being surrounded by specific cultural values and ideas. This is especially likely considering that the first to adopt iron technology in LBA central Sweden appears to have been the bronze casters (Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, p. 188). Bronze working was deeply embedded in a mythological and cultural framework (Goldhahn Citation2007, Engedal Citation2009, Melheim Citation2015), and casting sometimes formed part of public rituals and other culturally significant events and gatherings (Melheim et al. Citation2016, Sörman Citation2018). Thus, early iron was integrated into a very specific way of thinking and understanding the world and its materials. Similar to gold, which was used to enhance the sunglow of certain objects and symbols, iron was adapted and made meaningful within this matrix.

CONCLUDING REMARKS: HARNESSING THE PROPERTIES OF IRON

The results of this study challenge some earlier interpretations of iron as playing a minor, utilitarian role in the LBA and the early PRIA (Levinsen Citation1984, Sørensen Citation1989b, Hjärthner-Holdar Citation1993a, Nørbach Citation1998). The use of iron for small and inconspicuous objects like cutting tools, small dress attributes and rivets or fastening pins, and the dominance of bronze in the metalwork more broadly, has led to the understanding that early iron in the Nordic area during the LBA–early PRIA primarily represented a negligible, functional complement.

Its presence on highly valued bronze objects, and the selective use of iron for certain personal attributes and body ornaments, show that iron was sometimes displayed and valued for its visual qualities. This deepens the understanding behind why and where iron was considered appropriate. The iron on 12 decorative bronze disks from Hassle, and indications of a preference for lighter-coloured copper-alloys on similar ornaments, indicates the role of iron in relation to colour preferences in LBA metalwork. The practices, values, designs and symbols associated with this metal – when compared to bronze – reveal that iron was not perceived as a neutral or uninteresting complement, but as something similar but different. Compared to the values surrounding other metals, primarily bronze and gold, we identify colour, lustre and its watery origin as important factors in the adaptation of iron, while more familiar qualities such as hardness and sharpness were also attractive features.

Bronze Age iron has often been seen in relation to the later use of iron, emerging as a ‘productive force’ in the Early Iron Age society (e.g. Levinsen Citation1984, Nørbach Citation1998, p. 65–66). Such a view might have obscured other qualities, functions and associations tied to iron in the more distant past. The properties of iron sought after in the ninth to second centuries BC were in part different from those appreciated during later times, when iron gradually became integrated in everything from weaponry and agriculture to industry and transportation. Iron during LBA-PRIA I was indeed used for its ability to be smithed into sharp, cutting edges, but also for other things. We have proposed here that its lustre and colour – thereby both its similarity and difference in relation to bronze – was harnessed. Turning away from the economic and cultural-historical role of iron in later societies, we can see Bronze Age iron in its own right, in relation to the particular ontology, mentality and mythology into which it was first integrated.

ABBREVIATIONS

LBA Late Bronze Age

Nä Närke

PRIA Pre-Roman Iron Age

SHM Statens historiska museum (The Swedish History Museum)

SLM Sörmlands länsmuseum (Sörmland county museum)

Sö Södermanland

UMF Uppsala universitets museum för fornsaker (Uppsala University’s museum for ancient artefacts, now Museum Gustavianum)

Up Uppland

VLM Västmanlands läns museum (Västmanland county museum)

Vä Västmanland

APPENDIX

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors of the Norwegian Archaeological Review for thoughtful feedback that greatly helped us improve the text. We also thank Sophie Bergerbrant for pointing us to relevant literature. Finally, we would like to extend our appreciation to the staff at Örebro county museum for accommodating our visit to access the replicas of the Hassle hoard.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Appelgren, K., 2016. Östra berget i Påljungshage – rituell miljö från bronsålder och äldsta järnålder: arkeologisk förundersökning och undersökning. Södermanlands län, Södermanland, Nyköpings kommun, Helgona socken, Stenbro 1:8, Helgona 213, 348, 350, 353, 405 och Helgona 406. Hägersten: Arkeologerna, Statens historiska museer.

- Arbman, H., 1934. Periferisk bronsålderskultur. Fornvännen, 29, 203–212.

- Arbman, H., 1938. Mälardalen som kulturcentrum under yngsta bronsåldern. In: H. Nordling-Christiansen and P.V. Globe, eds., Winther-festskrift. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 83–108.

- Aspeborg, H., and Appelgren, K., 2005. Tankar om begravningar under bronsålder och äldre järnålder: väg E4, sträckan Uppsala-Mehedeby, Uppland, Tensta socken, Forsa 3:3, RAÄ 434: arkeologisk undersökning. Uppsala: UV GAL, Riksantikvarieämbetet.

- Baudou, E., 1960. Die regionale und chronologische Einteilung der jüngeren Bronzezeit im Nordischen Kreis. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Bennerhag, C., et al. 2021. Hunter-gatherer metallurgy in the Early Iron Age of Northern Fennoscandia. Antiquity, 95 (384), 1511–1526. doi:10.15184/aqy.2020.248

- Berger, D., 2014. Late Bronze Age iron inlays on bronze artefacts in central Europe. In: E. Pernicka and R. Schwab, eds., Under the volcano. Proceedings of the International Symposium of the Metallurgy of the European Iron Age in Mannheim 2010. Rahden/Westfahlen: Verlag Marie Leidorf, 9–24.

- Bergerbrant, S., 2007. Bronze Age identities: costume, conflict and contact in Northern Europe 1600-1300 BC. Lindome: Bricoleur Press.

- Bergerbrant, S., Bender Jørgensen, L., and Fossøy, S.H., 2013. Appearance in Bronze Age Scandinavia as seen from the Nybøl burial. European Journal of Archaeology, 16 (2), 247–267. doi:10.1179/1461957112Y.0000000026

- Bjørn, A., 1929. Vestby-fundet: et yngre bronsealders votivfund fra Hadeland. Universitetets Oldsaksamling Skrifter, II, 35–73.

- Bohlin, A., 1968. Västmanlands bronsålder. Västmanlands fornminnesförenings årsskrift, XLVII, 98–162.

- Brøndsted, J., 1959. Danmarks Oldtid. Vol. II, Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

- Buchwald, V.F., 2005. Iron and steel in ancient times. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab.

- Carlsson, A., 2001. Tolkande arkeologi och svensk forntidshistoria: bronsåldern (med senneolitikum och förromersk järnålder). Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Damell, D., 2008. Om järnproduktion under bronsålder och äldre järnålder i Linde bergslag. In: J. Goldhahn and H. Kalmar, eds., Gropar & monument: en vänbok till Dag Widholm. Kalmar: Högskolan i Kalmar, 353–362.

- Edlund, M., 2008. Treuddar och hägnader: E18-undersökning vid Bengtstorps gravfält. Närke, Täby socken, Bengtstorp 1:1, RAÄ 34, RAÄ 35. Örebro: UV Bergslagen, Riksantikvarieämbetet.

- Engedal, Ø., 2009. Verdsbilete i smeltedigelen. In: T. Brattli, ed., Det 10. nordiske bronsealdersymposium. Trondheim 5.-8. okt. 2006. Trondheim: Tapir, 37–49.

- Englund, L.-E., 2002. Blästbruk: myrjärnshanteringens förändringar i ett långtidsperspektiv. Stockholm: Jernkontoret.

- Fredengren, C., 2011. Where wandering water gushes – the depositional landscape of the Mälaren valley in the late Bronze Age and earliest Iron Age of Scandinavia. Journal of Wetland Archaeology, 10 (1), 109–135. doi:10.1179/jwa.2011.10.1.109

- Fredengren, C., 2015. Water politics: wet deposition of human and animal remains in Uppland, Sweden. Fornvännen, 111, 161–183.

- Giles, M., 2007. Making metal and forging relations: ironworking in the British Iron Age. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 26 (4), 395–413. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.2007.00290.x

- Goldhahn, J., 2007. Dödens hand - en essä om brons- och hällsmed. Gothenburg: Gothenburg university.

- Goldhahn, J., 2013. Rethinking Bronze Age cosmology: a North European perspective. In: H. Fokkens and A. Harding, eds., The Oxford handbook of the European Bronze Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 248–266.

- Grandin, L., and Hjärthner-Holdar, E., 2000. Bronsålderns järnproducenter. Uppsala: Riksantikvarieämbetet, UV GAL.

- Grandin, L., 2010. Järnframställning under förromersk järnålder: kemisk analys av slagg från blästugn med underliggande slagguppsamling: Holen 131/1, Gausdal kommune, Oppland, Norge. Uppsala: Riksantikvarieämbetet, UV GAL.

- Haaland, R., 2004. Technology, transformation and symbolism: ethnographic perspectives on European iron working. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 37 (1), 1–19. doi:10.1080/00293650410001207

- Hagen, B., 1954. Europeiske impulser i østnorsk bronsealder. Viking, 18, 97–125.

- Halbert, L., 1956. Djurskulpturer och järn från yngre bronsålder. Fornvännen, 51, 80–94.

- Hansson, P., 1989. Samhälle och järn i Sverige under järnåldern och äldre medeltiden: exemplet Närke. Uppsala: Societas Archaeologica Upsaliensis.

- Hed Jakobsson, A., Hjulström, B., and Lagerstedt, A., 2021. Återbruk – Molnby i Vallentunas utkant: bosättare, stenröjare och torpare. Upplands Väsby: Arkeologikonsult AB.

- Hedeager, L., 2021. Jernets magt. Available from: https://danmarkshistorien.lex.dk/Jernets_magt [Accessed 7 May 2021].

- Herbert, E.W., 1984. Red gold of Africa: copper in precolonial history and culture. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Hjärthner-Holdar, E., 1991. The transition from bronze to iron in the late Bronze Age. Lab Ark, 5, 125–134.

- Hjärthner-Holdar, E., 1993a. Järnets och järnmetallurgins introduktion i Sverige. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- Hjärthner-Holdar, E., 1993b. Övergången från brons till järnmetallurgi – en fråga om resurser. In: L. Forsberg and T.B. Larsson, eds., Ekonomi och näringsfång i nordisk bronsålder: Rapport från det 6:e nordiska bronsålderssymposiet, Nämforsen 1990. Umeå: Umeå University, 163–176.

- Hjärthner-Holdar, E., 2009. The earliest production of iron and steel in Sweden 1-5 september 2007. In: T. Brattli, ed., The 58th international sachsensymposium. Trondheim: Tapir, 26–36.

- Hornstrup, K.M., et al., 2012. A new absolute Danish Bronze Age chronology. Acta Archaeologica, 83 (1), 9–53.

- Hosler, D., 1995. Sound, color and meaning in the metallurgy of Ancient West Mexico. World Archaeology, 27 (1), 100–115. doi:10.1080/00438243.1995.9980295

- Jensen, J., 1989. Hallstattsværd i skandinaviske fund fra overgangen mellem bronze- og jernalder. In: J. Poulsen, ed., Regionale forhold i nordisk bronzealder: 5. nordiske symposium for bronzealderforskning på Sandbjerg slot 1987. Aarhus: Jysk Arkæologisk Selskab, 149–157.

- Jensen, J., 1997. Fra Bronze- til Jernalder. En kronologisk undersøgelse. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab.

- Karlsson, C., 2003. Mellan brons och järn. In: L. Karlenby, ed., Mittens rike: arkeologiska berättelser från Närke. Örebro: Riksantikvarieämbetet, UV Bergslagen, 363–376.

- Kaul, F., 2004. Bronzealderens religion: studier af den nordiske bronzealders ikonografi. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab.

- Kaul, F., 2005. Bronze Age three-partite cosmologies. Præhistorische Zeitschrift, 80 (2), 135–148. doi:10.1515/prhz.2005.80.2.135

- Kihlstedt, B., 1998. Arkeologisk undersökning: boplats och järnframställningsplats vid Sågebol, E20, Närke, Viby socken, RAÄ 214. Hägersten: Riksantikvarieämbetet, UV Mitt.

- Kuijpers, M.H.G., 2018. An archaeology of skill: metalworking skill and material specialization in Early Bronze Age central Europe. Oxon, New York: Routledge.

- Larsen, J.H., 2009. Jernvinna: faglig program, volume 2. Oslo: Museum of Cultural History.

- Larsson, T.B., 1986. The Bronze Age metalwork in southern Sweden: aspects of social and spatial organization 1800-500 B.C. Thesis (PhD). Umeå University.

- Lazarides, A., 2017. Järnframställningsplats från yngre bronsåldern i Viared: arkeologisk slutundersökning, RAÄ Borås 151, Viared 8:104, Borås socken och kommun. Lödöse: Västarvet kulturmiljö/Lödöse museum.

- Levinsen, K., 1984. Jernets introduktion i Danmark. Kuml, 31 (31), 153–168. doi:10.7146/kuml.v31i31.109139

- Levy, J.E., 1999. Metals, symbols, and society in Bronze Age Denmark. In: J. Robb, ed., Material symbols: culture and economy in prehistory. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University, 205–223.

- Ling, J., et al., 2014. Moving metals II: provenancing Scandinavian Bronze Age artefacts by lead isotope and elemental analyses. Journal of Archaeological Science, 41, 106–132. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.07.018

- Lund, J., and Melheim, L., 2011. Heads and tails – minds and bodies: reconsidering the late Bronze Age Vestby hoard in light of symbolist and body perspectives. European Journal of Archaeology, 14 (3), 441–464. doi:10.1179/146195711798356692

- Lyngstrøm, H., 2008. Dansk jern: en kulturhistorisk analyse af fremstilling, fordeling og forbrug. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab.

- Lyngstrøm, H., and Jouttijärvi, A., 2018. Failing arguments for the presence of iron in Denmark during the Bronze Age period IV. Regarding the razors from Kjeldbymagle and Arnitlund and a knife from Grødby. Danish Journal of Archaeology, 7 (2), 154–160. doi:10.1080/21662282.2018.1479952

- Lyngstrøm, H., 2020. Early iron and ironworking in Denmark. In: M. Brumlich, E. Lehnhardt, and M. Michael, eds., The coming of iron: the beginnings of iron smelting in Central Europe: proceedings of the International Conference Freie Universität Berlin Excellence Cluster 264 Topoi, 19-21 October 2017. Rahden: Verlag Marie Leidorf, 51–59.

- Martin, T.F., 2014. (Ad)Dressing the Anglo-Saxon body: corporeal meanings and artefacts in early England. In: P. Blinkhorn and C. Cumberpatch, eds., The chiming of crack’d bells: recent approaches to the study of artefacts in archaeology. Oxford: Archaeopress, 27–38.

- Martin, T.F., and Weetch, R., eds., 2017. Dress and society: contributions from archaeology. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Melheim, L., 2015. Recycling ideas: Bronze Age metal production in southern Norway. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Melheim, L., Prescott, C., and Anfinset, N., 2016. Bronze casting and cultural connections: Bronze Age workshops at Hunn, Norway. Praehistorische Zeitschrift, 91 (1), 42–67. doi:10.1515/pz-2016-0003

- Melheim, L., et al., 2018. Moving metals III: possible origins for copper in Bronze Age Denmark based on lead isotopes and geochemistry. Journal of Archaeological Science, 96, 85–105. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.04.003

- Modin, M., 1966. Ett gravfynd från Täby i Uppland. Fornvännen, 61, 154–163.

- Montelius, O., 1895. Den nordiska jernålderns kronologi I. Svenska fornminnesföreningens tidskrift, 9 (2), 155–214.

- Montelius, O., 1913a. När började man allmänt använda järn? 2. Fornvännen, 8, 61–91.

- Montelius, O., 1913b. När började man allmänt använda järn? 1. Fornvännen, 8, 1–27.

- Myrdal, J., 1982. Jordbruksredskap av järn före år 1000. Fornvännen, 77, 81–104.

- Nørbach, L.C., 1998. Ironworking in Denmark: from the late Bronze Age to the early Roman Iron Age. Acta Archaeologica, 69, 53–75.

- Nylén, E., 1972. Mellan brons- och järnålder: ett rikt gravfynd och dess datering med konventionell metod och C14. Antikvariskt Arkiv, 44, 5–46.

- Ojala, K., 2016. I bronsålderns gränsland: Uppland och frågan om östliga kontakter. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- Oldeberg, A., 1933. Det nordiska bronsåldersspännets historia: med särskild hänsyn till dess gjuttekniska utformning i Sverige. Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets-, historie- och antikvitetsakademien

- Oldeberg, A., 1952. Två Hallstattsvärd. In: M. Stenberger, ed., Arkeologisk forskning och fynd: studier utgivna med anledning av H M konung Gustav VI Adolfs sjuttioårsdag. Stockholm: Svenska arkeologiska samfundet, 372–381.

- Østigård, T., 2021. Vinter og vår i vannets verden: arkeologi om økologi og jordbrukskosmologi. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- Petré, B., 1982. Arkeologiska undersökningar på Lovö. Del 1: neolitikum, bronsålder och äldsta järnålder: undersökningar 1971-1980. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Prescott, C., 1991. Kulturhistoriske undersøkelser i Skrivarhelleren. Bergen: Historisk museum.

- Randsborg, K., 2010. Spirals! calendars in the Bronze Age in Denmark. Adoranten, 2009, 1‒11.

- Roberts, B.W., et al. 2015. Collapsing commodities or lavish offerings? Understanding large-scale metalwork deposition at Langton matravers, dorset. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 34 (4), 365–395. doi:10.1111/ojoa.12064

- Roberts, B.W., and Radivojević, M., 2015. Invention as a process: pyrotechnologies in early societies. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 25 (1), 299–306. doi:10.1017/S0959774314001188

- Rosenqvist, A.M., 1954. Studier av bronseteknikken i Vestbyfunnet. Viking, 18, 125–155.

- Röst, A., In prep. Brända bens betydelser: människoben från bronsålderns Hallunda.

- Rundkvist, M., 2015. In the landscape and between worlds: Bronze Age deposition sites around lakes Mälaren and Hjälmaren in Sweden. Umeå: Umeå University.

- Salin, B., 1905. Den förhistoriska tiden. In: A. Erdmann and K. Hildebrand, eds., Uppland. Skildring af land och folk. Volume 1. Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 161–228.

- Schwab, R., Ullén, I., and Wunderlich, C.-H., 2010. A sword from Vreta Kloster, and black patinated bronze in early Bronze Age Europe. Journal of Nordic Archaeological Science, 17, 27–35.

- Serning, I., 1984. Tidigt järn i Mellansverige. Gotländskt arkiv, 1984, 51–64.

- Simonsen, M.F., and Bukkemoen, G.B., 2015. Småhus og tidlig jernproduksjon i Sørum. In: I.M. Berg-Hansen, ed., Arkeologiske undersøkelser 2005-2006, Kulturhistorisk museum, Universitetet i Oslo. Kristiansand: Portal, 121–135.

- Skogstrand, L., 2021. Det første jernet. Universitetet i Oslo. Available from: https://www.norgeshistorie.no/forromersk-jernalder/0405-det-forste-jernet.html. [Accessed 12 June 2021].

- Soafer, J., Bender Jørgensen, L., and Sørensen, M.L.S., 2018. Part III: effects: shape, motifs, pattern, colour, and texture: introduction. In: L. Bender Jørgensen, M.L.S. Sørensen, and J. Soafer, eds., Creativity in the Bronze Age: understanding innovation in pottery, textile, and metalwork production. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 141–150.

- Sørensen, M.L.S., 1987. Material order and cultural classification: the role of bronze objects in the transition from Bronze Age to Iron Age in Scandinavia. In: I. Hodder, ed., The Archaeology of Contextual Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 90–101.

- Sørensen, M.L.S., 1989a. Period VI reconsidered: continuity and change at the transition from Bronze to Iron age in Scandinavia. In: M.L.S. Sørensen and R. Thomas, eds., The Bronze Age - Iron age transition in Europe. aspects of continuity and change in European societies c. 1200 to 500 B.C. Part ii. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 457–492.

- Sørensen, M.L.S., 1989b. Ignoring innovation - denying change: the role of iron and the impact of external influences on the transformation of Scandinavian societies 800-500 BC. In: R. Torrence and S.E. van der Leeuw, eds., What’s new? A closer look at the process of innovation. London: Unwin Hyman, 182–202.

- Sørensen, M.L.S., 1997. Reading dress: the construction of social categories and identities in Bronze Age Europe. Journal of European Archaeology, 5 (1), 93–114. doi:10.1179/096576697800703656

- Sørensen, M.L.S., 2013. Identity, gender, and dress in the European Bronze Age. In: A. Hardings and H. Fokkens, eds., The Oxford handbook of the European Bronze Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 216–233.

- Sørensen, M.L.S., and Appleby, G., 2018. Making metals: from copper to bronze. In: L. Bender Jørgensen, M.L.S. Sørensen, and J. Soafer, eds., Creativity in the Bronze Age: understanding innovation in pottery, textile, and metalwork production. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 75–80.

- Sörman, A., 2018. Gjutningens arenor: metallhantverkets rumsliga, sociala och politiska organisation i södra Skandinavien under bronsåldern. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Standley, E.R., 2020. Love and hope: emotions, dress accessories and a plough in later Medieval Britain, c. AD 1250–1500. Antiquity, 94 (375), 742–759. doi:10.15184/aqy.2020.61

- Stenberger, M., 1964. Det forntida Sverige. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Stjernquist, B., 1961. Simris II. Bronze Age problems in the light of the simris excavation. Lund: Lund University.

- Stjernquist, B., 1962. Ett svenskt praktfynd med sydeuropeiska bronser. In P. G. , Hamberg, eds. Proxima Thule: sverige och Europa under forntid och medeltid: hyllningsskrift till H.M. Konungen den 11 November 1962. Stockholm: Svenska Arkeologiska Samfundet, 72–93.

- Stjernquist, B., 1971. Hasslefyndet och kontinenten. In: Välstånd: Hallstatt. Gruvor och handel i Europas mitt 2 500 år före EEC. Stockholm: Statens Historiska Museum, 34–40.

- Strucke, U., and Holback, T., 2006. Järn och brons - metallhantverk och boende vid Åbrunna: väg 73, sträckan Jordbro-Fors: Södermanland, Österhaninge socken, Åbrunna 1:1, RAÄ 201: arkeologisk undersökning. Hägersten: Riksantikvarieämbetet, UV Mitt.

- Thrane, H., 1975. Forbindelser med Europa nord for Alperne i Danmarks yngre broncealder: (per. IV-V). Odense: Aarhus University.

- Thrane, H., and Jouttijärvi, A., 2020. A new Bronze Age hoard from Mariesminde at Langeskov on Funen, Denmark. Acta Archaeologica, 91 (2), 11–22. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0390.2020.12226.x

- Vandkilde, H., 2014. Breakthrough of the Nordic Bronze Age: transcultural warriorhood and a Carpathian crossroad in the sixteenth century BC. European Journal of Archaeology, 17 (4), 602–633. doi:10.1179/1461957114Y.0000000064

- Vedeler, M., et al., eds., 2018. Charismatic objects: from roman times to the middle ages. Oslo: Cappelen damm.

- Wedberg, V., 1984. Röda jorden: rapport från ett arkeologiskt forskningsprojekt. Västmanlands fornminnesförening och Västmanlands museum: årsskrift, 62, 155–162.

- Wigren, S., 1985. Femton kilometer forntid under motorvägen: fornlämningar från bronsålder till medeltid i Trosa-Vagnhärads, Västerljungs och Lästringe socknar i Södermanland: arkeologiska undersökningar 1979-1981. Stockholm: Riksantikvariämbetet.

- Winther Olesen, M., et al., 2020. Iron smelting in central and western Jutland in the early iron age (500 BC - AD 200). In: M. Brumlich, E. Lehnhardt, and M. Michael, eds. The coming of iron: the beginnings of iron smelting in Central Europe: proceedings of the International Conference Freie Universität Berlin Excellence Cluster 264Topoi, 19-21 October 2017. Rahden/Westfalen: VML Verlag Marie Leidorf, 61–80.