Abstract

Since its discovery in the 1970s, the rich rock art assemblage of Alta, Northern Norway, has been increasingly examined and interpreted. Central to the interpretations are topics such as ritual, circumpolar cosmology, landscapes and communication. The interpretative frame of reference has grown steadily, while discussions and disagreements have been surprisingly few. This paper argues that the outcome of this is a broad but still closely related set of understandings that define the kind of interpretations that qualify as likely or eligible. The paper offers a critical view on how ethnographic sources as well as concepts such as circumpolarity, rituals, and shamanism are mobilized in this interpretative formation. It also questions the increasingly more profound and intricate understandings of the rock art as a world-shaping and mediating tool. The interpretative imperative of finding a ‘deeper meaning’ is discussed and alternative approaches to rock art suggested.

INTRODUCTION

Primitive man lived in constant terror of finding that the forces around him which he found so useful were worn out. For thousands of years men were tortured by the fear that the sun would disappear forever at winter solstice, that the moon would not rise again, that plants would die forever, and so on (Eliade Citation1958, p. 346)

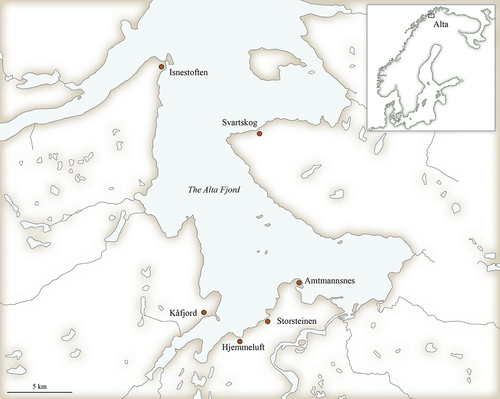

The Alta rock art, which is the collective name for all the prehistoric rock engravings and paintings discovered in the Alta area, Northern Norway (), is a veritable cornucopia. In the making for 5000 years, their sheer number (between 5500 and 7000, depending on how they are counted), the variation in motifs and styles, as well as in the location and layout of the rocks and the sites, are properties that in themselves can provide materials for countless analyses concerning age, groupings, traditions, and styles. The engravings are also a source of information regarding the environment, resources and technologies as well as the practises and conditions in the societies they originated from. And then it is the matter of how to understand them – why were they made, and what did they mean? To be fair, Mircea Eliade’s musings on ‘primitive man’ are not representative for how researchers have reasoned to find the meaning and purpose behind the Alta rock art. However, an assumed urgency to negotiate, mediate and communicate with ‘forces’, spirits or other people, to balance, structure and control the world, as well as to secure life and order in society, are consistently and increasingly stressed in interpretations, making rock art a matter of need, and thus of utmost importance.

’Rock art was often made where communication with the spirits were believed to be good’ Knut Helskog stated (HelskogCitation2010: 169), while Ingrid Fuglestvedt has asserted that: ’Rock art sites are to be regarded as ritual places, and rock art making is part of the ritual: this interpretation now has full consensus‘ (Fuglestvedt Citation2018, p. 3). Such statements are frequently uttered in the archaeological discourse on rock art, both generally and with regard to the object of this study, the Alta rock art assemblage. In this context statements such as these must be regarded as premises to move forward in discussions and considerations on how to understand rock art. Nevertheless, the way they are self-evidently expressed seems to imply a certainty on why the rock art was created and what it basically meant. On what are these givens based? Where does this certainty come from?

Put differently, it seems that interpretations are shaped in compliance with certain taken-for-granted ideas of what rock art was; that is, that it belonged to the ritual, cosmological and religious, and, thus, something that was always seriously and zealously designed with intent and meaning. This givenness may be said to have become something like a ’black box‘ in the Latourian sense (Latour Citation1987), though the various interpretations by themselves are not necessarily thought of as representing any truth or givens. Seen together they nevertheless act to create certain norms, and thus, restrictions on opinions which the scholarly discourse on the Alta rock art seldom transgresses.

In this paper, by following the development and growth of research and texts on the matter, I aim to examine how the interpretational framework for the Alta rock art has advanced. I further identify and consider some motives and rationales for the interpretations provided and treat some central premises that may be questioned. For sure, critically scrutinizing this body of research may trigger requests for alternatives, i.e. new solutions for how to decode the ancient shapes fashioned into these northern rocks. However, instead of presenting any substitute explanations to what the rock art meant, alternative ways to approach this phenomenon are discussed.

THE ALTA ROCK ART

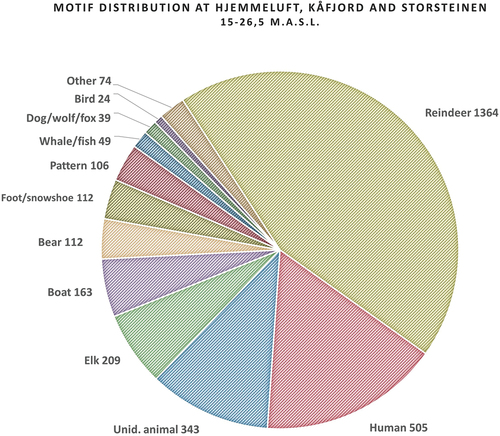

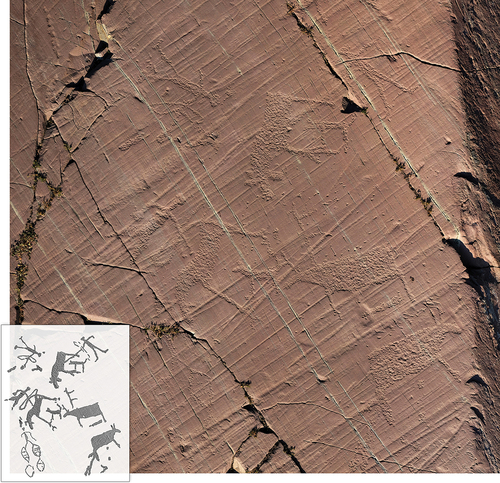

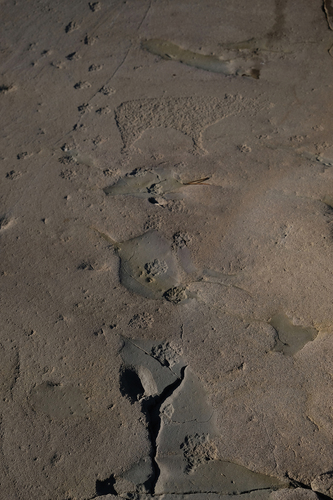

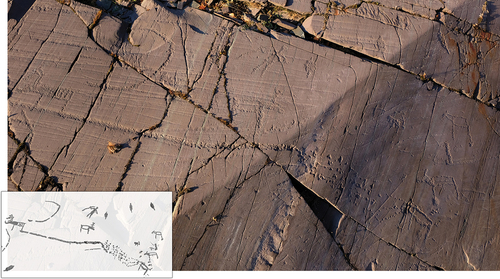

The diverse and plentiful Alta rock art is situated within a limited geographical area of the Alta Fjord, in Finnmark in northern Norway. Elsewhere in the region rock art is sparse. The Alta rock art comprises several thousand engravings, a number continuously rising as new figures and panels are discovered and documented. While the corpus also includes five relatively small sites with prehistoric rock paintings, this paper concerns the engravings only. The latter are found at four major and four smaller sites in the vicinity of the seashore, situated between ca. 8 and 26,5 m.a.s.l. Most of the engravings were made on bedrock, or on immovable large boulders, such as the so called Storsteinen, but engravings also occur on smaller blocks. The geology differs at the four major sites, influencing the rock arts’ appearance and physical endurance in a fluctuating natural environment. Site topography is also quite diverse, and the most obvious common trait is the proximity to the seashore. The panels vary considerably in size, numbers and content; some panels contain one figure, while others display hundreds. Animals, like reindeer, humans, elk and bears are common motifs, as well as boats, geometric patterns, footprints and bear tracks (). A characteristic trait is the many scenes and happenings recorded on the rocks, especially among the earliest engravings. Figures, sometimes quite many, partake in activities, interact or form groups, which in turn has inspired many of the interpretations mentioned in the next section. Recognizable motifs, such as reindeer or bear, display a wide variety of forms within the defined phases, and some forms occur across phases.

Fig. 2. The estimated number of identified motifs between 15 and 26,5 masl in Hjemmeluft, Kåfjord and Storsteinen are 3101. Figures that were incomprehensible to the author, as well as dots, lines (ca. 1600) and bear tracks (ca. 1700) are not included. Neither were the rock engravings at Amtmannsnes (14–16 masl), nor the ones at Apana Gård in Hjemmeluft (8–13 masl), ca. 700 figures altogether. A preliminary assessment of the motifs’ occurrence, suggest a predominance of humans, reindeer (or inconclusive cervidae at Amtmannsnes) and boats (at Apana Gård). Such numbers will vary and change due to new documentation and new discoveries, how the figures are categorized, and who is doing the work. However, the tendencies would probably be quite similar. (Illustration: K. Tansem).

A phase sequence based on stylistic similarities within the same height ranges above present sea level was developed by Knut Helskog and published in 1983. It has later been adjusted and refined, however, the general principles of the chronological framework have not been seriously challenged (Helskog Citation1984, Citation1985, Citation1987, Citation1999, Citation2014, Gjerde Citation2010a, Tansem Citation2020). The rock engravings are estimated to have been made from ca. 7000 to ca. 2000 years ago (e.g. Gjerde Citation2010a, Helskog Citation2014). The dating is based on raised shoreline chronology (for general discussions on shoreline dating in Northern Europe see Gjerde Citation2010a, Goldhahn Citation2017, Lahelma Citation2008, Lødøen Citation2015, Ramstad Citation2000, Sognnes Citation2003; for discussions on Alta see Gjerde Citation2010a, Helskog Citation1983, Tansem Citation2020), as well as on dated archaeological materials in the region (e.g. Helskog Citation1983, Citation2011, Gjerde Citation2010a). Both the age estimates and Helskog’s phase sequence rest on the assumption that Stone Age rock art generally was produced on clean and fresh rocks on the seashore (e.g Sognnes Citation2003, Gjerde Citation2010a, Tansem and Storemyr Citation2021), an assumption that is reflected also in interpretations. This notion has been debated (e.g. Sognnes Citation2003, Lødøen Citation2015, Stebergløkken Citation2015), and pertaining to the Alta rock art, there are variations and anomalies when compared with the suggested chronological sequence (Tansem Citation2020). However, the overall patterns still seem to be in accordance with this framework as originally presented by Helskog (Citation1983) ().

Fig. 3. All the recorded engraved bears in Alta at approximate elevation, save the one at Isnestoften. Bears on the same elevations are generally assumed to be of the same age. Characteristics of style justify this notion, though variations in and across phases also occur. (Illustration: K. Tansem, based on tracings by R. Normann and K. Tansem).

ESSENCE AND MEANING

The Alta rock art did and does not exist as an isolated corpus; connections and relations are legion, both in space and time. Hence, when presenting more than 40 years of research, only what are considered significant contributions are included. In these short summaries, details and nuances are necessarily lost, and the presentation may come across as missing out on aspects of the research done. The main objective, however, is not to scrutinize every statement made about the Alta rock art, but rather to identify and account for some major themes and plots that have developed in the interpretations of it.

BEFORE ALTA

The understandings of northern or Arctic rock art were early on connected to magic and religion, and there was also a general agreement on its ‘psychological source in primitive hunting magic’ (Gjessing Citation1936, p. 1, my translation). Gutorm Gjessing suggested a development from naturalistic and large figures to small and schematic ones in the northern hunter’s rock art (Gjessing Citation1936, Citation1942, Citation1944). From being an ‘asocial individualistic magic’ performed by the hunters at the hunting grounds, rock art became a more organized social activity performed by the shaman who turned the art into a ‘shamanistic ritual dogma’ (Gjessing Citation1942, p. 437–438). However, the magic still concerned the hunt, both in order to secure a good outcome and the regeneration of the game. This is also where the circumpolar association is beginning to take its hold on rock art interpretation in the north (see section 3). Another prominent scholar on the early rock art research scene in Northern Norway was Povl Simonsen, who by and large agreed to Gjessing’s chronological and magical setup and origin (Simonsen Citation1958).

A NEW ROCK ART CORPUS TO APPRAISE

The discovery of the Alta rock art in the 1970s introduced a formidable new corpus of northern rock art. In 1983, Knut Helskog published the first archaeological analysis of the material, mostly concerned with chronology and age (Helskog Citation1983). Helskog found that Gjessing’s developmental scheme did not apply to Alta but proposed no major alternative interpretations to contest the already established understanding of rock art as ritualistic hunting and fertility magic (). However, he made suggestions for how particular figures and scenes could be interpreted (Helskog Citation1984, Citation1985, see also 1999, 2014) as expressions of myth and symbolism, portraits of spirits or people in power, and also about how the art may display both real and mythological events. Helskog moreover stressed the significance of northern ethnographic accounts for understanding the art and the societies who made them. The bridging idea was that the physical conditions for life in the north, and implicitly the economy, social organization, and religion described in these accounts, were similar to that of the prehistoric peoples of Finnmark (Helskog Citation1984). To further examine and justify this, Helskog compared both the figurative and the presumed spiritual and ritual content of the rock engravings to historical ethnographic records of the Sámi (Helskog Citation1984, Citation1985, Citation1987).

POST-PROCESSUAL INTERVENTION: THE MEETING PLACE

Using post-processual theory, Bryan Hood (Citation1988) brought the concept of space into the Alta rock art discussion, and the idea of Alta as a meeting place. Hood rejected the earlier hunter’s magic interpretations as eco-functionalist; the rock art could rather be seen as representing ‘traces of the whole gamut of social practises, ideologies and contradictions‘ (Hood Citation1988, p. 65). Hood interpreted the Alta rock art as a kind of material discourse that articulated and structured socio-economic relations between coast and inland. This included organization of labour, maintenance of social reproduction networks over large distances, and control of resources, e.g. hunting grounds and lithic raw material such as chert, which is obtainable in the Alta area (Hood Citation1988, pp. 77–78). By itself emerging from the coastal bedrock, exchanged chert could take on significance as a portable mediator of the discourse encoded in the rock engravings.

The new conception of the large rock art sites as meeting grounds where people gathered to negotiate social and ideological matters through rituals and rock art (Hood Citation1988, Hesjedal Citation1990, Tilley Citation1991) proved to have considerable impact on the general perception of hunter’s rock art (Fuglestvedt Citation2018, p. 76). This was hereafter emphasized or mentioned by most scholars working on the Alta rock art, underlining its intermediate location between the outer coast and the interior (e.g. Olsen Citation1994, Hesjedal et al. Citation1996, Helskog Citation1999, Citation2004, Citation2011, Citation2014, Gjerde Citation2010a, Fuglestvedt Citation2018). Less attention, however, has been given to the ideological codes and power structures that Hood suggested as being embedded in the rock art.

LANDSCAPE, SHAMANISM AND ROCKS

From the 1990s and onward, new ideas and perspectives influenced the interpretations. The works of David Lewis-Williams and Thomas Dowson (e.g. Williams and Dowson Citation1988) on rock art, shamanism and altered states of consciousness (ASC) have played a weighty part in placing shamanism as a pivotal element of hunter’s rock art. Despite being occasionally mentioned, the emphasis on ASC is downplayed in most interpretations concerning shamanism and the Alta rock art. Far more influential for the interpretations of the latter was another element connected to the shaman theory introduced; how the rock surface itself acted as an interface or ‘veil’ suspended between this world and the spirit world. Accordingly, certain features of the rock, such as fissures, could be considered openings which entranced shamans may use to communicate with the other-worldly spirits or even enter through themselves. This novel way of viewing the rock, not as a passive canvas, but as part of the supernatural scheme, should from now on become a principal feature of attention. Moreover, increased archaeological and anthropological focus on landscape, and phenomenological conceptions of this (e.g. Bradley Citation1991, Ingold Citation1993, Tilley Citation1994), also had a huge impact on how the Alta rock art was described and understood; that is, as something relating and responding to the surrounding landscape, the rock surfaces themselves, as well as the layout of the sites.

Attempts to connect changes in the art with overall changes in the archaeological record (e.g. Helskog Citation1984, Citation1987, Citation2000, Olsen Citation1994), however, dwindled. The chronology and dating established by Helskog was rarely questioned (exceptions being Olsen Citation1994, Hesjedal et al. Citation1996, see also Gjerde Citation2010a, Helskog Citation2000, Citation2014), and attention was rather directed at the rock art’s social and religious role. Most interest was now given the earliest (and richest) rock art panels, mostly leaving out the later ones (found at Amtmannsnes, Storsteinen and lower altitudes in Hjemmeluft) (e.g. Helskog Citation1999, Citation2004, Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2012, Gjerde Citation2010a, Fuglestvedt Citation2018, Tansem Citation2020).

SEASHORE AND COSMOLOGY

In 1999 Helskog launched the idea that the rock engravings’ proximity to the seashore could be of crucial cosmological significance (see also Tilley Citation1991, p. 135–139). Inspired primarily by Siberian ethnographic sources, and elaborated on in several consecutive texts, the cosmos was seen as divided into three strata (sky/upper world, land/this world, water/lower world), where the seashore became a cosmological interface where these worlds converged (Helskog Citation1999, Citation2004, Citation2010, Citation2012). Being by definition an intermediate zone, the shore hence attained a new ritualized significance and was thus the perfect place for transformation and communications with other worlds and the spirits therein. ‘Passages’ to the lower world, such as cracks in the rock surfaces, amplified the communicative potential. Helskog detected real landscape features represented in the rocks’ surfaces, such as rivers, lakes, valleys and mountains, also seen as mirroring the cosmological ones (Helskog Citation1999, p. 77, 2004, p. 283–285).

Against this topographical backdrop the engravings depicted spirits, symbols and mythological incidents, as well as actual happenings with people, animals and things, all moving in and out of different worlds, and connected through stories played out on spiritually potent rocks (). The need for an intermediate ritual leader was emphasized, though not always referred to as a shaman (e.g. Helskog Citation1999, p. 90, 2012, p. 212, 2014). According to Helskog, ‘Nothing seems more important than to communicate with “the other things”, the life of the supernatural, for human benefit’ (Helskog Citation2004, p. 266–267, see also Citation2014). Making rock art was a communicative and beneficial activity and which also, with reference to Hood (Citation1988), included payoffs as securing social order, and negotiating rights to resources between coastal and interior groups (Helskog Citation2004, p. 282).

Fig. 4. Hunting elks with spears and bows at Kåfjord, 23 masl. Notice the dogs partaking in the hunt. (Photo/tracing: K. Tansem).

Fig. 5. Bear tracks are the only motif in Alta that occurs in greater numbers than reindeer. The more than 1700 tracks are often, but not always, accompanied by bears. The rows of tracks are assumed to make the time and storytelling aspects apparent in the art. These are at Hjemmeluft (Photo: K. Tansem).

GEOGRAPHY AND JOURNEYS

Landscapes, real or spiritual, was Jan Magne Gjerde’s (Citation2010a) main research objective in a comparative analysis of five large rock art sites in northern Fennoscandia, among them Alta (). As Hood and Helskog, Gjerde emphasized the meeting place perspective, as the sites were positioned at geographical locations ideal for this (Gjerde Citation2010a, p. 454). The concept of journeying, in a real or spiritual sense, was emphasized as crucial to both rock art and society. Gjerde moreover proposed that the location of the sites coincided with favourable hunting grounds for big game like reindeer, elk and beluga whale, which also guided the choice of motifs at the particular rock art sites. This further connected the art to the hunt as one of its most important reasons and references (Gjerde Citation2010a).

Fig. 6. An example of how cracks and other natural surface features are used to position the rock art: At the Kåfjord panel one can follow scattered reindeer tracks uphill from the right, forming a single trail on the flat top surface, ending in the hunting fence where hunters are waiting. (Photo/tracing: K. Tansem).

Gjerde (Citation2010a, p. 112–113) based his interpretations on circumpolar ethnographic sources, considered vital to understand northern rock art and landscapes. Concurring with Helskog’s cosmological readings, i.e. the rock art’s spiritual and ritual affinity to the landscaped and membraned rocks, Gjerde extended its function to acting as a mnemonic device, storing important and varied knowledge of the lands. Accordingly, panels were interpreted as representing real, geographically placed activities intertwined with spiritual landscapes (Gjerde Citation2010a, p. 278–281, also 2019). A link to a shamanistic-like cosmology seemed evident, as this in ‘some form seems to be integral, either in the making, performance, or different uses of the rock art’ (Gjerde Citation2019, p. 204, also 2010a, p. 120–123, 446, 452).

MOTEMES AND THE HUMAN – BIG GAME ENIGMA

In her comprehensive work on Scandinavian Late Mesolithic rock art, Ingrid Fuglestvedt started by pointing out that she was ‘certainly not denying the fact that rock art is rooted in rituals and trance, or that its compositions are connected to landscape conceptions, cosmology or mythology’ (Fuglestvedt Citation2018, p. 8). However, the origin of rock art, she argued, was to be located in ‘the actions of the wild mind’, and by applying Claude Lévi-Strauss’ theories of language, myth and music to major Scandinavian rock art sites, Fuglestvedt identified rock art as ’aesthetically expressed reflections over the Mesolithic leitmotif, also defined as the human – big game enigma’ (Fuglestvedt Citation2018, p. 129).

Central to Fuglestvedt’s thinking about rock art are the concepts of metaphor, transformation, repetition, ambiguity and confrontation. Adding to that, her analytical invention, the moteme (in line with phoneme and mytheme), was defined as ‘the smallest motif unit of significance in Nordic hunter’s rock art’ (Fuglestvedt Citation2018, p. 79). Fuglestvedt identified 12 motemes, and among them were design patterns, elk-humans and -boats, herds, hunting scenes, big game head poles, rituals and complex confrontations (Fuglestvedt Citation2018, p. 159–162). The key moteme was the big game herd. The preoccupation with herds originated from the sociality of animals and was related to an emerging attention to human society (Fuglestvedt Citation2018, p. 128). All 12 motemes are represented in Alta, and Fuglestvedt (Citation2018, p. 159) acknowledged, referring to the imagery of the earliest phase, that her motemic concept would be impossible without the Alta rock art. All the Scandinavian motemes of the Late Mesolithic period, she argued, were commenting each other, linked by a system of internal references (Fuglestvedt Citation2018, p. 294), suggesting a ‘super-individual level of meaning belonging to the collectively and historically inherited world’ (Fuglestvedt Citation2018, p. 10). Fuglestvedt also observed transitions between animistic and totemic rock art in Scandinavia where the distribution of the motemes indicated possible contemporaneity and long-distance lines of contact (Fuglestvedt Citation2018, p. 162, 334, 338–349). As the Late Mesolithic rock art tradition ended, and early farming in the south emerged, the hunting-gathering way of life and an animistic mindset typical of the circumpolar culture tradition continued in the north (2018, p. 400, also Fuglestvedt Citation2020).

STATUS QUO: INTERPRETATIVE FUNDAMENTALS

Following this review of interpretations of the Alta rock art, it seems that most of them extend or elaborate previous ones. In the texts referred to, there are few examples of attempts to dispute previous interpretations in their various forms. It seems more appropriate to describe the historiography as a continuous and peaceful swelling of the interpretational framework, where new suggestions have been added and fitted into or alongside the ones already proposed.

The interpretations can be grouped in some main, though often overlapping, thematic compartments; the circumpolar hunting magic and shaman segment, which grew into the cosmology, landscape and ‘veil’ division. Here, the rocks themselves have become increasingly more active participants through what they afford or offer. Parallel and interspersed are the structuralist and post-structuralist text and language-inspired interpretations, where negotiating and mediating aspects in a meeting place setting are emphasized. The rock art is also conceived of as mnemonic and informational, as keeping or sharing knowledge, providing geographical reference and as involved in storytelling, the latter lately also explored by non-representational and narratological approaches (Nyland and Stebergløkken Citation2020, Ranta et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, the art can simultaneously represent both real and mythological happenings and entities. There is also a growing tendency that the main analytical and explanatory features in interpretations rarely are restricted to local or regional expressions of rock art. They are rather ascribed a more general validity relevant to rock art over large geographical areas such as Fennoscandia or Northern Europe, although regional differences in line with or inconsequential to the overarching theory, often are included.

The common explanations for why people made rock art, seems to be twofold. On the one hand, it was a way to communicate with other entities, corporal or spiritual, in order to affect or control certain aspects of the world(s). On the other hand, rock art was as a means to make sense of the world, where transformation and ambiguity in the art reflected, shaped and processed the perceived reality, and relational conditions that people had to deal with. On a more principal level, the interpretations appear to emphasize some commonly perceived ‘fundamentals’ with regard to rock art and the making of it. That rock art and ritual are inseparable, for one thing, seems given. Making rock art, moreover, was a serious endeavour and a necessity to achieve vital goals. Yet another a priori is intentionality. In the considerations of the detailing of the motifs’ shapes and parts, and in assuming that the figures are carefully placed in relation to each other and features in the rocks, intentionality becomes an important premise for most interpretations. As a consequence, the figures that are taken into consideration in analyses are never conceived of as unfinished, failed or just made without any serious purpose (see Fahlander Citation2020a). From its very beginning, and lately increasingly so, the interpretation of rock art has been based on an assumed association with religion; that is, beliefs, world views, ritual practises and the supernatural. In Alta, thus, the art was ‘caused’ by the belief in a spirited world, variously explained as animism, totemism and variants of shamanism incorporated into an overarching multi-dimensional cosmology often depicted as ‘circumpolar’. In the next sections I will further explore what might be conceived of as problematic aspects of the assumed ritual character of rock art, the use of ethnographic accounts to explain it and herein also the ideas of the circumpolar connection.

RITUAL

Close to every text occupied with the Alta rock art mentioned in this paper refers to rock art and rock art making as ritual. Ritual, as with several of the nonsecular or otherworldly elements in archaeological interpretations, is claimed to escape general definition, and there are undoubtedly problematic aspects with this concept and its usage (e.g. Brück Citation1999, Insoll Citation2004). It is perhaps therefore that ritual only sporadically is defined, for example as ‘an enactment of religious beliefs by which people communicate with the supernatural’ (Helskog Citation2004, p. 265, also 1999).

Moreover, the rock art’s connection to the rituals is mostly vague and diverse: it is seldom specified how it is ritual or ritualized. Simonsen (Citation1986, p. 198) asked ’Was the holy act the hewing of the picture or the performance of some ceremony after the picture was finished?’ He in fact answered the question and meant the engravings were ornaments to accompany the ceremonies to be performed on the site. Simonsen had noticed rock engravings he considered to be failed or modified, upon which he reasoned that to avoid making mistakes and correcting them during important ceremonies, the engravings were made beforehand. In other considerations the Alta rock art’s ritual role seems flexible and uncommitting, and thus adaptable to shifting interpretations.

Hence, the rock engraving activity may be described both as the ritual, or part of the ritual, and preparing for later rituals in which the engravings could be activated and/or provide a context. The rituals themselves appear highly flexible, and may be connected to hunting, fertility, seasonal changes, animal reverence and journeying (physical and spiritual). They may also have served to maintain or negotiate relationships between groups, have acted as rites of initiation or transition, and above all as a way to communicate with spirits and souls. The rituals could be communal or private, and, thus, to be performed either by spiritual leaders or lay people. The rock art, moreover, is also conceived of as ritual because it sometimes depicts what is asserted to be ritual acts ().

Fig. 7. Depictions of people engaged in other activities than hunting or fishing are often interpreted as performing rituals. At Hjemmeluft. (Photo: K. Tansem).

When rock art is determined as ritual in a routine and axiomatic manner, it becomes an intrinsic property that asserts the rock arts’ formal and symbolic nature. Already at their outset, interpretations on the rock art’s meanings and intentions are delimited by this truism. This triggers the questions of whether the rock art was always ritual, made in a ritual context or with ritual objectives in mind? Given the rock art’s and the associated rituals’ assumed crucial significance, all the inherent potent meanings and possible consequences the rock art makers had to be aware of and handle, actually become quite staggering.

ETHNOGRAPHIC ANALOGY, HUNTER-GATHERERS AND THE CIRCUMPOLAR CONNECTION

Although the use of ethnographic analogy in archaeological reasoning have been under debate (in general e.g. Binford Citation1967, Fahlander Citation2004, Hodder Citation1982, Ravn Citation2011, Wylie Citation1985, concerning rock art e.g. Bahn Citation2010, Berrocal Citation2011, Currie Citation2016, Porr and Bell Citation2012), the use of such analogies is one of the foundations, perhaps the most important one, on which the dominating interpretations of Fennoscandian hunters and gatherers’ rock art rest. The fact that the Alta rock art were made by hunters and gatherers, has strongly influenced how it has been interpreted. However, the hunter-gatherer category may be regarded as problematic in itself, considering the colonial historical context of its origin, the vagueness of what distinguishes it from other forms of human society and what it actually is supposed to comprise (e.g. Warren Citation2021). Graham Warren, for example, has warned about the danger of both imposing regional or local ethnographic presents into the past, and of fetching analogies from ethnographically observed hunter-gatherers from more distant geographical environments without justifying the choice. This persistent use of selected analogical comparisons re-establishes and affirms the category of ‘hunter-gatherers’, which may result in the generation of a fixed ‘indigenous’ perspective devoid of diversity and dynamism (Warren Citation2021).

In research on the Alta rock art, references to hunter-gatherers’ worldviews, whether depicted as animism, totemism or shamanism are many. While the discussions and criticisms concerning both the concept of shamanism and the interpretations of rock art it has inspired, are extensive (e.g. on shamanism: Hutton Citation2001, Insoll Citation2004, Kehoe Citation2000, Sidky Citation2010, on shamanism and rock art:, Bahn Citation2010, Berrocal Citation2011, Jacobson Citation2001, McCall Citation2007, Rozwadowski Citation2012, VanPool Citation2009), the responses are few (however, see Whitley Citation2006). Adrian Currie (Citation2016, p. 88) identifies three kinds of objections from critics aimed at both direct and indirect ethnographic analogy concerning shamanism: the reliability of the source, whether ‘shamanism’ is an adequate term, and how it is utilized in interpretation. Even though Currie’s first two points are stressed at times, the third objection, regarding interpretative use, is rarely discussed. Interpretations involving shamanism (or comparable religious practices) and more specifically the accompanying three-tiered cosmology has a strong footing also in research done on other rock art collections in Northern Europe (e.g. Tilley Citation1991, Goldhahn Citation2002, Lahelma Citation2005, Citation2008, Janik Citation2015). Maria Cruz Berrocal’s (Citation2011, p. 11) statement regarding studies of South African and European palaeolithic rock art may apply also here: ‘In reality, shamanism is no longer used as a plausible hypothesis; instead, it has acquired the status of a fact’. Accordingly, rock art easily becomes a supplementary or derivative evidence of the prehistoric existence of this worldview, and whereby the interpretation of the rock art turns into an act of translation (Berrocal Citation2011).

Regarding the interpretations of the Alta rock art, intertwined with the preferred ethnography is the notion of the circumpolar, a concept that goes beyond a mere geographical reference to the region that includes the parts of Europe, Asia and the Americas that is above the Arctic Circle. In his 1944 book ‘Circumpolar Stone Age’ Gjessing presented his theory of circumpolar cultural uniformity based on ‘the fundamental view that the unique natural conditions around the Arctic Ocean had set a strong common impress upon the Arctic cultures’ (Gjessing Citation1944, p. 5). By analysing and comparing archaeological and ethnographic records from the Northern Hemisphere, he found a common origin of European and northern Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and currently existing cultures in ancient Asiatic Stone Age culture (Gjessing Citation1944, pp. 65–67). This manifested in a still persisting ‘strange cultural fellowship’ stretching from Fennoscandia to Greenland. Despite exposure to ‘culture-infiltrations’, traditions remained since ‘everywhere in Arctic hunting cultures (lies) a tremendously tenacious and invincible conservatism, deeply anchored in hunting itself.’ (Gjessing Citation1944, p. 7).

The conditional premise of a homogeneous circumpolar environment rests on a shaky foundation. In fact, the circumpolar area is not at all similar, varying from tundra to taiga, and from coastal to inland milieus, differing in climates and biomes. Nevertheless, the recurring assumption of a past and present circumpolar ‘fellowship’ of hunter-gatherers, that not only generated similar solutions to practicalities, but apparently by default also the same worldviews and cosmologies is still vigorous. Features of ‘circumpolar’ hunting cultures are considered conditional to the Alta rock art, although one does acknowledge that most of the ethnographic records actually are acquired from colonized societies that would be classified as pastoral or agricultural. The cosmologies, ritual practises and gears that are put on the interpretative table, may indeed indicate compelling similarities, but the recorded variations are nevertheless substantial (e.g. Hallowell Citation1926, Hutton Citation2001).

There is also more to this than explicit analogies. By attaching the term ‘circumpolar’ to concepts like rock art, ethnography, hunter-gatherers, cosmology, and rituals, an extended connotation is added that somehow connects and characterizes the peoples of the north disregarding time and place. It should also be noted that rock art research is not alone in harbouring these ideas of a circumpolar (sometimes referred to as boreal, sometimes Arctic) cosmology and general conformance (e.g. Appelt et al. Citation2017, Jordan and Zvelebil Citation1999, see also Herva and Lahelma Citation2020). While innate conservatism rarely is considered a valid argument, an assumed longevity is still present and only occasionally explained.

This, of course, is not to denounce the significance of ethnographic analogies and information altogether. Currie (Citation2016, p. 93) aptly observed that there ‘is no such thing as the licence for ethnographic analogy, but nor is there such a thing as the objection to it’ (see also Binford Citation1967, Insoll Citation2004, Bahn Citation2010, Berrocal Citation2011). Warren, despite his critical reservations, still judged hunter-gatherer ethnography as vital to illuminate human diversity and used archaeologically it may be read ‘against the grain’, in a ‘creative and subversive praxis’ (2021, p. 807), a notion that will be revisited later in the paper.

DISCUSSION

This critical exploration into the interpretations of the Alta rock art has questioned some of the premises that many interpretations seem to rest on, and their possible implications. The meanings uncovered are usually conditioned by certain assumptions and givens, forming a framework of interpretation that has been, and still is, effective. In the next part of the paper, I will discuss some further aspects of this framework, followed by some examples of other possible outsets when engaging with rock art.

Bjørnar Olsen described his impression of recent (in 2010) writings on rock art as a:

never ending urge to intellectualize the past: a constant search for a deeper meaning,something beyond what can be sensed. According to this unveiling mode a boat, anelk, or a reindeer can be claimed to represent almost everything – ancestors, rites oftransitions, borders, supernatural powers, and so on – apart, it seems, only fromthemselves. A boat is never a boat; a reindeer is never a reindeer; a river is always a‘cosmic’ river. This is not at all to dismiss the image’s potential symbolicsignificance. However, may it not be plausible that – sometimes at least – it wasactually the depicted being that mattered? (Olsen Citation2010, p. 86).

The inclusion of the reindeer in Olsen’s criticism of the urge to always go beyond the depicted being actually calls for some reflections. Ironically, the reindeer is rarely ascribed another role than as itself; as a practical and corporal entity in the world, an object for the hunt – as food and deliverer of other needed materials (however see e.g. Gjerde Citation2010a, Helskog Citation2014, Skandfer Citation2021, Günther Citation2022). Compared to the significance ascribed to the elk and the bear in most interpretations, the reindeer acts more like an inconsequential ‘figural filler’, or as ‘extras’ among the cosmological ‘lead characters’ in the readings of the Alta rock art panels. This bias is hardly demographically motivated. As the by far most common motif in Alta (more than 40% of the classified figures), one might have expected some more attention to this species and also to why an apparently ritually and cosmologically less significant figure was depicted so often. In other words, in constructing plausible, compelling and applicable interpretations, the attention to some aspects in the art might take focus away from others.

One example of research on rock art that made a clear point of the importance of interpretations beyond time, place and appearance, is Christopher Tilley’s groundbreaking book Material culture and text. The art of ambiguity (1991). Here he described the recording and research previously done on Nämforsen in Sweden (primarily targeting Hallström Citation1960), as overlaying the actual rock art as ‘an opaque slime sticky with words and figurational representations’, accompanied by a ‘deadening visual catalogue of the empiricist archaeological text’ (Tilley Citation1991, p. 7). Tilley admitted that his own book was ‘parasitic’ on Gustaf Hallström’s, and that he was unfair in his judgment as Hallström delivered what the archaeological zeitgeist demanded: provision of materials and chronology as an end in itself. He nevertheless considered Hallström’s work, the meticulous documentation and descriptions, as a ‘complete failure’ (Tilley Citation1991, pp. 14–15). To Tilley, Hallström exemplified the tragedy of the archaeology of his time – characterized by ‘painstaking, almost masochistic effort, an immense labour, but a failure to disclose meaning. What this amounts to is an evasion of the responsibility to make sense of the past’ (Tilley Citation1991, p. 15).

The introduction of post-processual theory brought about a whole new set of tools to extract meaning from the archaeological record (). As mentioned earlier (section 3), the post-structuralist work in the early 1990s had great impact in adding the interpretational possibilities that were provided by the idea of the ‘subtle language of figural art’ (Fuglestvedt Citation2018, p. 76). Paired with the increasing interest in the ethnographic record for comparative studies, it perhaps led to what Olsen (Citation2012, p. 21) diagnosed as ‘our current obsession with turning mute things into storytellers or otherwise loading them with interpretative burdens they mostly are unfit to carry’. If this is an apt description of the current situation, it comes close to what Susan Sontag called an ‘aggressive’ hermeneutics, which according to her characterized modern art critics (Sontag 2009 [Citation1966]). In these interpretations, the apparently intelligible and manifest expressions are always doomed as insignificant, and, thus, to be pushed aside to find the true meaning – the latent and hidden content.Footnote1 Perhaps the will to interpret beyond the figures’ appearance, finding new connections and meaningful features, has turned into an imperative, answering this persistent archaeological zeitgeist’s call for taking ‘the responsibility to make sense of the past’(Tilley Citation1991, p. 15).

Although the interpretations of the Alta rock art differ in many ways, the elaborate meaningfulness of the engravings is hardly ever questioned. In most texts, it is emphasized that accurate knowledge of meaning is impossible to obtain, as in this random example from Helskog: ‘We can recognise bears and boats, but we have no direct knowledge about what they metaphorically symbolise’ (Helskog Citation2004, p. 265). That they ‘metaphorically symbolise’, however, does not raise any doubt, as confirmed by the very beginning of the same text, where it is stated that: ‘Rock carvings are here taken to represent religious beliefs and rituals’ (Helskog Citation2004, p. 265). When there exists a general agreement about the rock art as being made in accordance with such overarching frames of meaning, and thus with a hidden content to be revealed, attention to what the engravings actually portray may, as argued by Olsen in the citation above, come across as insignificant or even disturbing in the efforts to disclose the real meaning ().

As the meaning of rock art is difficult to prove, it is equally difficult to disprove. The nature of the matter at hand, prehistoric and also often labelled as art, prevents it from delivering ready answers, and most interpretations cannot be refuted with other than a personal lack of conviction, which does not account to much in a scientific conversation. The theories put forward might be more or less convincing in their efforts to describe worldviews, societies and situations past. However, despite that the rock art’s own material support for the interpretations is vague, the interpretations themselves appear more and more solid and self-evident through their repetition and circulation in the scientific discourses. By contributing to the interpretative imperative, the research on the Alta rock art has built layer upon layer, adding new variations, without outright disputing any of the previous suggestions, rendering the construed reality the rock art makers had to cope with very complicated indeed. Interpretations keep emerging, and most of them avoid confrontations with the fresh and newly formed ‘opaque slime’ covering their empirical source.

Though not fitting his singular paradigmatic framework, the research on the Alta rock art carries features that comply with what Kuhn (Citation2012[1962]) aptly called ‘normal science’. This condition is characterized by a situation where scholars agree on the base principles and goals for the research, which thus advances in a cumulative manner. Related ideas are proposed by Bruno Latour (Citation1987) through his term ‘blackboxing’, mentioned earlier. This describes how scientific work is obscured by its own success; when a matter of fact is settled, the internal complexity of the fact and its construction becomes unimportant, inputs and outputs being the focal points. In my opinion, the notion that rock art is ritual, formal, and fundamentally intentional, can be judged as factual, a black box, which premises require no further scrutiny. The many interpretations that emerge from this box have thus attained a solidity, or partial solidity, that becomes defining for the academic discourse concerning the Alta rock art. One consequence of this is that suggestions about the rock art’s nature or rationale which are not in compliance with such settled matters of fact, might risk being disregarded as serious contributions to this discourse.

ALTERNATIVES

There is, however, inspiration to be found in different ontologies, or ontological stances, by which the rock arts’ predicated formal and representational nature may be viewed otherwise. Olsen refers to how the Sámi herders’ attentiveness to the reindeer and the herd is based on concern for their well-being. The reindeer and the herd had value and significance in their own right and should be respected, cared for and honoured. He goes on to suggest that this may not have been very different in the past:

maybe it was just the world as it circumspectively appeared to the prehistoric carver through his or her own concerned engagement with it that northern rock art ‘is about’. This was a meaning that in some sense was already given and to carve was to add to, to work on, or to supplement this latent circumspective significance. In this world, the reindeer was sufficiently meaningful in itself by ‘just’ being a reindeer (Olsen Citation2010, p. 87)

Rock art could then be referring to the reality these people lived in, an ontological perception of the world as spirited and animated, not as something separate and esoteric, but as actual and worldly. Given certain beings significance to their life, such as the reindeer, depicting them may have been an expression of sincere concern and attentiveness (). Even making an image of what might have been a god, a spirit or an idea may not necessarily imply a special act of communication or negotiating with the powers or the others, but merely accounting for or commenting elements or principles that were perceived to be there, acting and being in the world.

Fig. 8. Next to the halibut caught on a fishing line, stands an animal that has been interpreted as a spirit assisting the fishers. The animal is suggested to be an elk, a bear, as well as an ambiguous and meaningful fusion of the two. These figures in Hjemmeluft were painted red in the 1980s to make their whereabouts easier to detect for visitors. (Photo: K. Tansem).

This is somewhat reminiscent of how Martin Porr and Bell (Citation2012) described animism or ‘a hunter-gatherer world view’, not as a particular belief system, but rather as an awareness of the fundamental conditions of life itself, created by humans’ continuous engagement with their environment. That there is such a thing as an identifiable hunter-gatherer worldview as opposed to a modern understanding of the world is ‘an illusion of Western imagination’ (Porr and Bell Citation2012, p. 185). They argue that the importance of art, music and narratives among non-western people is not accidental, but concerns the dynamics of life, not to control the environment, but by dialogue finding a way through it. As this reflects the fundamental characteristics for human life everywhere, elements and methods of expression usually found outside academic discourse must be included to complement and expand it.

Art history has mostly left prehistoric rock art to social anthropology and archaeology to treat as it was determined, together with other non-western art, as objects with functional and magical properties, and not purely aesthetic expressions (i.e. art for art’s sake) (Porr Citation2019). Archaeology, on the other hand, has mostly considered the making and using of rock art as collective activities, devoid of individual expression (e.g. Tilley Citation2021). Aesthetics or art historical approaches, as well as indigenous perspectives on art, are thus rarely included in discussions on rock art. Studies of rock art have neglected to take individual agency and creativity – inherently unstable and dynamic human characteristics only assumed to arise in modern times – into consideration (Porr Citation2019). Human creativity and their entanglement not only with rock art but with objects in general, should thus be studied at different temporal scales, focusing on the mutual relationships between the individual and the social, as well as the individual and the environment (Porr Citation2019).

‘Rock art is a s much ecology as it is art’, stated Benjamin Alberti and Fowles (Citation2018, p. 151) in an article concerning the rock art of the Rio Grande Gorge in New Mexico, USA, containing thousands of rock art panels, dated from ca. 5000 BC to present. From an ecological perspective, the history of a place is always more-than-human; its history transcends human participation. The authors suggest that the human rock art tradition in their case began with ‘ecologically literate’ people wanting to join in the local history of the land, and they did this by making images. In their case the initial images resembled what was already created in the landscape; animal tracks in mud, dust and snow. Human travellers in a challenging landscape relied on animal trails – and making such marks allowed them to participate in existing animal meaning creation (Alberti and Fowles Citation2018). Moreover, ‘rock art begets rock art’ (Alberti and Fowles Citation2018, p. 139), which may account for the various forms of later rock art in the area. It was created by Native Americans, but also Catholic colonizers and even more recent graffiti-producing visitors who were prompted to annotate previous imagery, drawing it into their own workings on the rock surfaces. They were all partakers in a rock art tradition that was already underway before humans entered into it (Alberti and Fowles Citation2018).

This brings us to the matter of rock art and place. The large collections of rock art at specific locations in Northern Europe has been explained as an outcome governed by properties of the landscape or the place, which made them suitable for social, ritual and rock art producing gatherings in prehistoric times. However, such accumulative processes as proposed by Alberti and Fowles (Citation2018) have rarely been considered pertaining to the Alta rock art. Generative effects or processes have also been suggested by Fredrik Fahlander after studying the Bronze Age rock art in the Boglösa area in Sweden, which he considered to be a landscape passed through, rather than dwelt in (2020b). Instead of taking the perception of the rock art as reflections or illustrations of ideology or cosmology as his point of departure, Fahlander focused on what it did (or does), as material articulations working beyond representation (see also Nyland and Stebergløkken Citation2020). Acknowledging that rock art figures might incite and influence actions and events, the recurring production of similar motifs, the transformations of, additions to and even the destruction of rock art figures might be viewed as imagery in the becoming. Over time, relations between old and new motifs were generated, some of them intentional, others not. Even ‘accidental’ visual expressions could develop and be repeated intentionally over time (Fahlander Citation2020b).

Fahlander pointed at the importance of keeping the discussions specific in order not to let regional variability obscure local patterns (Fahlander Citation2020b, p. 134). This could also be articulated the other way around, as focusing on regional patterns may obscure local variations. The substantial diversity found in the Alta rock art, recordable from site to site and from panel to panel, within and between phases, are so far rarely accounted for, also forming patterns within patterns that may provide more diversified insights concerning this specific rock art ensemble if its local idiosyncrasies are taken into consideration ().

Fig. 11. Two panels at Hjemmeluft, situated ca. 63 metres from each other at the same elevation. The upper contains reindeer, some animals that may be reindeer, a bear and a line. To my knowledge, it has not been considered in any analysis. The lower panel, however, is far more diverse regarding motifs, full of action and is frequently referred to in interpretations. (Tracing and illustration: K. Tansem).

Fig. 12. A bear and her cub; wandering between worlds or simply in this? At Hjemmeluft (Photo: K. Tansem).

Finally, in this listing of alternative ways of approaching rock art, there are some examples of reading ethnography ‘against the grain’ (Warren Citation2021), concerning the manner of which ritual, rock art and treatment of spirits may be thought of or dealt with. Willerslev (Citation2007, p. 151) described how the Siberian Yukagir hunters provide secular rather than spiritual reasons to their ritual activities: ‘it is work rather than spirits that concerns them, and their frame of mind is just as sensible and empirical as that of any worker engaged in some practical project.’. Furthermore, he asked if taking animism seriously involves not taking it too seriously (Willerslev Citation2013), as he observed that important aspects of the animistic cosmologies of the Siberian Yugakirs is laughter, irony and ridicule towards the spirits. Interesting are also the responses given in interviews with practitioners of traditional and ongoing rock art production among Samburu in Kenya (Goldhahn et al. Citation2021). Ceremonial and ritual activities were described, but the creation of the art was not part of it, it was on the contrary considered as a recreational activity during stays away from the village while herding cattle. The aesthetic qualities of the artwork were valued, and the more skilled artists appreciated. For the Sámi, one could get ‘reindeer luck’ and a large and beautiful reindeer herd by making deals with a sieidi (sacred rocks), serving and worshipping it, but the luck would not be true, and it would not last. It would be better to treat the sieidi with respect from a distance, wishing it well, but mostly leave it alone, and obtain the luck otherwise (Oskal Citation1995, p. 140–141).

Comparisons with contemporary rock art ‘ethnographies’ (e.g. Alberti and Fowles Citation2018, Nash Citation2010, Goldhahn et al Citation2021), as well as insights from thoughts on non-humans or objects (Domanska Citation2006, Petursdottir Citation2012), the strange (Farstadvoll Citation2019), ‘problematic stuff’ (Büster Citation2021), the apparently ‘meaningless’ (Olsen Citation2011), on wonder (Stengers Citation2011) and, in this context, perhaps especially on art (Porr Citation2019), may generate novel approaches and appreciations of rock art. If it is possible to take it as far as envisaging that some or even all of the Alta rock art were made for no consequential reasons, outside a formal and symbolic frame of reference, is it not too simple an approach to make sense of the past? Trying to take rock art also at face value, perceiving its meaning as immediate, missing, or in some cases even flippant, rather than as content-rich social or religious utterances, may probably be ascribed as naïve or banal (see Olsen Citation2012, Petursdottir Citation2013), or even as not taking rock art seriously at all. In some ways this argument might be turned however – that attributing postulates of what prehistoric rock art was to its creators and their societies, may be viewed as somewhat disrespectful and distancing. It has been argued that ethnography cannot be held superior to e.g. modern social practises in archaeological analyses, and to continue to rely on the ‘constructed ethnographical record … will only preserve a dull view of prehistory, not to mention its androcentric and Western, patronising implications’ (Fahlander Citation2004, p. 205). And according to Porr and Bell (Citation2012, p. 192) the academic creation of a specific hunter-gatherer ontology located in certain mental or perceptual settings, objectifies hunter-gatherers as well as their philosophies, when elements of what is perceived of as ‘animism’ might be recognized in every human practise.

FINAL REMARKS

Framed rather sarcastically, Tilley wrote that all Gustav Hallström could say after his lifelong work at Nämforsen was that ‘the most important thing is the material’ (as quoted in Tilley Citation1991, p. 10). Some would agree with Hallström. To rephrase Warren’s query on hunter-gatherer archaeology: ‘if there is a distinctive kind of archaeology which is to do with rock art, then what is it that provides that identity? Is it really the materials that we deal with, or the ideas that we use? Or is it something else?’ (Warren Citation2021, p. 796). Rock art archaeology has perhaps become an art of interpretation first and foremost, downscaling the importance of collecting, documenting and describing the material that the interpretations refer to, and in that process simultaneously and involuntarily act to devalue the material, its richness and idiosyncrasy. After all, it is rarely the interpretations that create wonder to those who come to experience the rock engravings in Alta – it is the rock art itself; its time depth and unbelievable duration, but foremost the immediate expressions delivered directly by the figures, the rocks and the landscape they are in.

Olsen (Citation2010, pp. 86–87) made a plea for that the rock art figures ‘at least sometimes’ actually could refer directly to the beings portrayed and, thus, that their being was significant enough in itself (). Dismissing the distinction between form and content as illusory, Sontag claimed that interpretation had become the revenge of the intellect upon art, and even the world: ‘By reducing the work of art to its content and then interpreting that, one tames the work of art. Interpretation makes art manageable, comfortable.’ (Sontag 2009 [Citation1966], p. 8). Curiously, prehistoric rock art is rarely treated as relating to creativity, individuals or, actually, as art, perhaps because ‘Images and artistic objects seem to establish a realm that neither the philosopher nor the modern archaeologist can control’ (Porr Citation2019, p. 159). The fact that the rock art makers’ reasons to do their artwork is beyond our reach, leaves in some respects the rock art as well as other archaeological remains to be their own testimony.

The objective of this paper is not to refute understandings of the Alta rock art as ritual or religious expressions, or any other social and cosmological interpretations. The interpretations suggested are both innovative and important and serve to widen and enrich perspectives on how the rock art may be understood. However, a clearer delineation between interpretations would make them more manageable in a multivocal interpretational environment regarding a matter that cannot be decoded once and for all. This may in turn inspire to a gentler and more democratic discourse concerning what rock art was as well as what it is.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for advice and suggestions on an earlier draft. Much gratitude is also extended to Bjørnar Olsen and Gørill Nilsen for invaluable input and kind support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Footnote: Even Sontag added ‘latent’ content, as she opened her essay with: ‘The earliest experience of art must have been that it was incantatory, magical; art was an instrument of ritual. (Cf. The paintings in the caves at Lascaux, Altamira, Niaux, La Pasiega, etc.)’ (Sontag 2009 [Citation1966], p. 3, italics in original).

References

- Alberti, B., and Fowles, S., 2018. Ecologies of rock and art in Northern New Mexico. In: E. Suzanne and B. Pilaar, eds., Multispecies Archaeology. London: Routledge, 133–153.

- Appelt, M., Grønnow, B., and Odgaard, U., 2017. Studying scale in prehistoric hunter-gatherer societies: a perspective from the Eastern Arctic. In: M. Sørensen and K. Buck Pedersen, eds., Problems in palaeolithic and mesolithic research. Vol. 12. Copenhagen: Arkæologiske Studier, 39–59.

- Bahn, P., 2010. Prehistoric rock art. polemics and progress. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Berrocal, M., 2011. Analogical evidence and shamanism in archaeological interpretation: South African and European palaeolithic rock art. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 44 (1), 1–20. doi:10.1080/00293652.2011.572672

- Binford, L., 1967. Smudge Pits and hide smoking: the use of analogy in archaeological reasoning. American Antiquity, 32 (1), 1–12. doi:10.2307/278774

- Bradley, R., 1991. Rock art and the perception of landscape. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, l (l), 7–101.

- Brück, J., 1999. Ritual and rationality: some problems of interpretation in European archaeology. European Journal of Archaeology, 2 (3), 313–344.

- Büster, L., 2021. ‘Problematic stuff’: death, memory and the interpretation of cached objects. Antiquity, 95 (382), 973–985. doi:10.15184/aqy.2021.81

- Currie, A., 2016. Ethnographic analogy, the comparative method, and archaeological special pleading. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 55, 84–94. doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2015.08.010

- Domanska, E., 2006. The return to things. Archaeologia Polona, 44, 171–185.

- Eliade, M., 1958. Patterns in comparative religion. London: Sheed and Ward Ltd.

- Fahlander, F., 2004. Archaeology and anthropology - brothers in arms? In: F. Fahlander and T. Østigaard, eds., Material culture and other things. post-disciplinary studies in the 21st century. Lindome: Bricoleur Press, 185–211.

- Fahlander, F., 2020a. The partial and the vague as visual mode in bronze age rock art. In: I.M. Back Danielsen and A. Meirion Jones, eds., Images in the making. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 202–215.

- Fahlander, F., 2020b. The stacked, the partial, and the large. visual modes of material articulation in mälaren bay rock art. In: K.I. Austvoll, et al., eds., Contrasts of the nordic bronze age. essays in honor of christopher prescott. Turnhoult: Brepols, 127–137.

- Farstadvoll, S., 2019. Vestigal matters: contemporary archaeology and hyperart. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 52 (1), 1–19. doi:10.1080/00293652.2019.1577913

- Fuglestvedt, I., 2018. Rock art and the wild mind. visual imagery in mesolithic Northern Europe. London and New York: Routledge.

- Fuglestvedt, I., 2020. Scenes of human control of reindeer in the alta rock art. an event of early domestication in the far North? Current Swedish Archaeology, 28 (28), 121–146. doi:10.37718/CSA.2020.06

- Gjerde, J.M. 2010a. Rock art and Landscapes. Studies of Stone Age rock art from Northern Fennoscandia. Thesis (PhD), Archaeology, University of Tromsø.

- Gjerde, J.M., 2019. ‘The world as we know it’ – revisiting the rock art at bergbukten 4B in alta, northern Norway. Time and Mind, 12 (3), 197–206. doi:10.1080/1751696X.2019.1645521

- Gjessing, G., 1936. Nordenfjeldske ristninger og malinger av den arktiske gruppe. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- Gjessing, G., 1942. Yngre steinalder i Nord-Norge. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- Gjessing, G., 1944. Circumpolar stone age. København: Ejnar Munksgaard.

- Goldhahn, J., 2002. Roaring rocks: an audio-visual perspective on hunter-gatherer engravings in Northern Sweden and Scandinavia. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 35 (1), 29–61. doi:10.1080/002936502760123103

- Goldhahn, J., 2017. North European rock art: a long-term perspective. In: B. David and I. McNiven, eds., The oxford handbook of the archaeology and anthropology of rock art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 51–72.

- Goldhahn, J., et al., 2021. ‘I have done hundreds of rock paintings’: on the ongoing rock art tradition among samburu, Northern Kenya. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 31 (2), 229–246. doi:10.1017/S095977432000044X

- Günther, H. 2022. The rhythm of rock art animals. Picturing reindeer, elk and bear around the seasonal cycle in Stone Age Alta. Thesis (PhD), Archaeology, Stockholm University.

- Hallowell, I., 1926. Bear ceremonialism in the northern hemisphere. American Anthropologist, New Series, 28 (1), 1–175. doi:10.1525/aa.1926.28.1.02a00020

- Hallström, G., 1960. Monumental art of Northern Sweden from the stone age: nämforsen and other localities. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Helskog, K., 1983. Helleristningene i Alta i et tidsperspektiv – en geologisk og multivariabel analyse. In: I. Østerlie and A. Kjelland, eds., Folk og ressurser i nord. foredrag fra trondheimssymposiumet om midt og nordskandinavisk kultur 1982. `Sandnes. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 47–60.

- Helskog, K., 1984. Helleristningene i Alta: en presentasjon og en analyse av menneskefigurene i Alta. Viking, 47, 5–42.

- Helskog, K., 1985. Boats and meaning: a study of change and continuity in the alta fjord, arctic Norway, from 4200 to 500 B.C. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 4 (3), 177–205. doi:10.1016/0278-4165(85)90002-9

- Helskog, K., 1987. Selective depictions: a study of 3,500 years of rock carvings from arctic Norway and their relationship to the Sami drums. In: I. Hodder, eds., Archaeology as Long-Term History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 17–30.

- Helskog, K., 1999. The shore connection: cognitive landscape and communication with rock carvings in Northernmost Europe. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 32 (2), 73–94. doi:10.1080/00293659950136174

- Helskog, K., 2000. Changing rock carvings – changing societies? Adoranten, 5–16.

- Helskog, K., 2004. Landscapes in rock art: rock-carving and ritual in the old European North. In: C. Chippindale and G. Nash, eds., The figured landscape of rock art. Looking at pictures in place. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 265–288.

- Helskog, K., 2010. From the tyranny of figures to the interrelationship between myths, rock art and their surfaces. In: G. Blundell, C. Chippindale, and B. Smith, eds., Seeing and Knowing. understanding rock art with and without Ethnography. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 87–169.

- Helskog, K., 2011. Reindeer corrals 4700–4200 BC: myth or reality? Quaternary International, 238 (1–2), 25–34. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2010.10.001

- Helskog, K., 2012. Bears and meaning among hunters-fishers-gatherers in Northern Fennoscandia 9000-2500 BC. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 22 (2), 209–236. doi:10.1017/S0959774312000248

- Helskog, K., 2014. Communicating with the world of beings. the world heritage rock art sites in alta, arctic Norway. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Herva, V., and Lahelma, A., 2020. Northern archaeology and cosmology. A relational view. London: Routledge.

- Hesjedal, A. 1990. Helleristninger som tegn og tekst. Thesis (magister), University of Tromsø.

- Hesjedal, A., et al., 1996. Arkeologi på Slettnes. Dokumentasjon av 11.000 års bosetning. Tromsø: Tromsø Museums. skrifter. 26.

- Hodder, I., 1982. The present past: an introduction to anthropology for archaeologists. London: B.T. Batsford.

- Hood, B., 1988. Sacred pictures, sacRed rocks: ideological and social space in the North Norwegian stone age. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 21 (2), 65–84. doi:10.1080/00293652.1988.9965473

- Hutton, R., 2001. Shamans. Siberian spirituality and the Western imagination. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Ingold, T., 1993. The temporality of the landscape. World Archaeology, 25 (2), 152–174. doi:10.1080/00438243.1993.9980235

- Insoll, T., 2004. Archaeology, ritual, religion. London: Routledge.

- Jacobson, E., 2001. Shamans, shamanism and anthropomorphizing imagery in prehistoric rock art of the mongolian Altai. H.-P. Francfort, R.N. Hamayon, and P. Bahn, eds., The concept of shamanism. uses and abuses. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, Bibliotheca Shamanistica, 277–294.

- Janik, L., 2015. In search of the origins of shamanism, community identity and personal experiences: prehistoric rock art and the religion of northern peoples. Fennoscandia Arcaeologica, 32, 139–150.

- Jordan, P., and Zvelebil, M., 1999. Hunter fisher gatherer ritual landscapes. In: J. Goldhahn, eds., Rock art as social representation. Vol. 794. Oxford: BAR International Series, 101–127.

- Kehoe, A., 2000. Shamans and religion: an anthropological exploration in critical thinking. Long Grove: Waveland Press Inc.

- Kuhn, T.S., 20121962. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lahelma, A., 2005. Between the worlds. rock art, landscape and shamanism in subneolithic Finland. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 38 (1), 29–47. doi:10.1080/09018320510032402

- Lahelma, A., 2008. A touch of red: archaeological and ethnographic approaches to interpreting finnish rock paintings. Iskos. Vol. 15. Helsinki: Finnish Antiquarian Society.

- Latour, B., 1987. Science in action: how to follow scientists and engineers through society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lewis-Williams, D., and Dowson, T., 1988. The signs of all times: entoptic phenomena in upper palaeolithic art. Current Anthropology, 29 (2), 201–217. doi:10.1086/203629

- Lødøen, T., 2015. Treatment of corpses, consumption of the soul and production of rock art: approaching Late Mesolithic mortuary practises reflected in the rock art of Western Norway. Fennoscandia Archae-ologica, 32, 79–99.

- McCall, G.S., 2007. Add shamans and stir? A critical review of the shamanism model of forager rock art production. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 26 (2), 224–233. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2006.09.001

- Nash, G., 2010. Graffiti-art: can it hold the key to the placing of prehistoric rock-art? Time and Mind, 3 (1), 41–62. doi:10.2752/175169710X12549020810452

- Nyland, A., and Stebergløkken, H., 2020. Changing perceptions of rock art: storying prehistoric worlds. World Archaeology, 52 (3), 503–520. doi:10.1080/00438243.2021.1899042

- Olsen, B., 1994. Bosetning og samfunn i Finnmarks forhistorie. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Olsen, B., 2010. In defense of things: archaeology and the ontology of objects. Lanham: AltaMira Press.

- Olsen, B., 2011. Halldors lastebil og jakten på tingenes mening. Kunst og Kultur, 4 (4), 180–189. doi:10.18261/1504-3029-2011-04-02

- Olsen, B., 2012. After interpretation: remembering archaeology. Current Swedish Archaeology, 20 (1), 11–34. doi:10.37718/CSA.2012.01

- Oskal, N. 1995. Det rette, det gode og reinlykken. Thesis (PhD), University of Tromsø.

- Petursdottir, T., 2012. Small things forgotten now included, or what else do things deserve? International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 16 (3), 577–603. doi:10.1007/s10761-012-0191-0

- Petursdottir, T. 2013. Concrete matters: Towards an Archaeology of Things. Thesis (PhD), University of Tromsø.

- Porr, M., 2019. Rock art as art. Time and Mind, 12 (2), 153–164. doi:10.1080/1751696X.2019.1609799

- Porr, M., and Bell, H.R., 2012. ‘Rock-art’, ‘animism’ and two-way thinking: towards a complementary epistemology in the understanding of material culture and ‘rock-art’ of hunting and gathering people. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 19 (1), 161–205. doi:10.1007/s10816-011-9105-4

- Ramstad, M., 2000. Veideristningene på Møre: teori, kronologi og dateringsmetoder. Viking, 63, 51–86.

- Ranta, M., et al., 2020. Hunting stories in Scandinavian rock art: aspects of ‘tellability’ in the north versus the south. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 39 (3), 228–246. doi:10.1111/ojoa.12197

- Ravn, M., 2011. Ethnographic analogy from the Pacific: just as analogical as any other analogy. World Archaeology, 43 (4), 716–725. doi:10.1080/00438243.2011.624781

- Rozwadowski, A., 2012. Rock art, shamanism and history: implications from a Central Asian case study. In: B. Smith, K. Helskog, and D. Morris, eds., Working with rock art. recording, presenting and understanding rock art using indigenous knowledge. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 193–204.

- Sidky, H., 2010. On the antiquity of shamanism and its role in human religiosity. Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 22 (1), 68–92. doi:10.1163/157006810790931832

- Simonsen, P., 1958. Arktiske helleristninger i Nord-Norge II. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- Simonsen, P., 1986. The Magic picture: used once or more times? In: G. Stensland, eds., Words and objects. towards a dialogue between archaeology and history of religion. Oslo: The Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture, series B: Skrifter LXXI, 197–211.

- Skandfer, M., 2021. The appreciation of reindeer: rock carvings and sámi reindeer knowledge. In: J.M. Gjerde and M. Arntzen, eds., Perspectives on differences in rock art. Sheffield: Equinox, 113–128.

- Sognnes, K., 2003. On shoreline dating of rock art. Acta Archaeologica, 74 (1), 189–209. doi:10.1111/j.0065-001X.2003.aar740104.x

- Sontag, S., 20091966. Against interpretation and other essays. London: Penguin.

- Stebergløkken, H. 2015. Style dating of rock art – an outdated method? In T. Frederico, ed. Proceedings XXVI Valcamonica Symposium 2015. Prospects for the Prehistoric Art Research, 50 years since founding of Centro Camuno, Valcamonica. Capo di Ponte: Centro Camuno di Studi Preitorici, 279–284.

- Stengers, I., 2011. Wondering about Materialism. In: L. Bryant, N. Srnicek, and G. Harman, eds., The speculative turn: continental materialism and realism. Melbourne: re.press, 368–380.

- Tansem, K., 2020. Retracing Storsteinen: a deviant rock art site in Alta, northern Norway. Fennoscandia Archaeologica, 37, 83–107.

- Tansem, K., and Storemyr, P., 2021. Red‐coated rocks on the seashore: the aesthetics and geology of prehistoric rock art in alta, arctic Norway. Geoarchaeology, 36, 314–334. doi:10.1002/gea.21832

- Tilley, C., 1991. Material Culture and text: the art of ambiguity. London: Routledge.

- Tilley, C., 1994. A phenomenology of Landscape: places, paths and monuments. Oxford: Berg.

- Tilley, C., 2021. Thinking through images: narrative, rhythm, embodiment and landscape in the Nordic bronze age. Oxford: Oxbow books.

- VanPool, C., 2009. The signs of the sacred: identifying shamans using archaeological evidence. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 28 (2), 177–190. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2009.02.003

- Warren, M., 2021. Is There Such a thing as hunter-gatherer archaeology? Heritage, 4 (2), 794–810. doi:10.3390/heritage4020044

- Whitley, D., 2006. Is there a shamanism and rock art debate? Before Farming, 4 (4), 1–7. doi:10.3828/bfarm.2006.4.7

- Willerslev, R., 2007. Soul hunters: hunting, animism, and personhood among the siberian yukaghirs. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Willerslev, R., 2013. Taking animism seriously, but perhaps not too seriously? Religion and Society: Advances in Research, 4 (1), 41–57. doi:10.3167/arrs.2013.040103

- Wylie, A., 1985. The reaction against analogy. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, 8, 63–111.