?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper argues that the Nordic boatbuilding tradition and the use of sail in Scandinavia can be traced back to the Early Bronze Age when it developed in response to emerging chiefdoms and an associated need for long-distance trade in bronze metals. The southern Scandinavian boat imagery dated to the Bronze Age (BA) depicts different types of boats and means of propulsion, including large vessels and the use of sail. This paper focuses on crew-lines on such imagery as indicative of boat length in relation to both the 350 BC Hjortspring boat, a BA type boat and the width-to-length ratio of BA ship-settings. This comparison suggests the BA boat imagery and ship-settings depict the same type of plank-built vessels and that the BA ship-settings are likely to represent ‘real’ vessels. Centrally positioned post holes in four of these ship-settings are therefore likely to represent masts, providing a direct link with mast-like features also present in the rock art boat imagery. Available BA boatbuilding technologies, based on analysis of the Hjortspring boat, and other indirect evidence of BA boatbuilding technologies, suggests that large, sailed vessels most likely existed, propelled in combination with mainly paddling.

INTRODUCTION

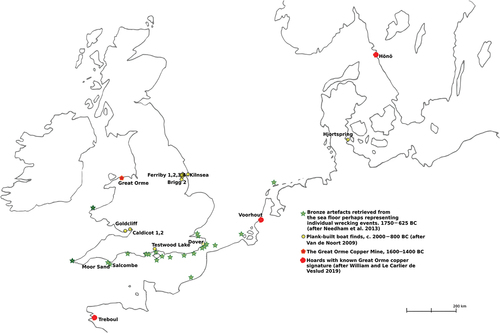

Plank-built boat technology, where individual planks were fastened with withies or sewn with thread, caulked to make watertight and strengthened with beams or frames attached to integral cleats protruding inwards from the planks, not only resulted in sturdier, longer lasting and more seaworthy vessels, but also allowed for better control of shape and size in comparison to previous boat types (McGrail Citation2007, Van de Noort et al. Citation2014, Kastholm Citation2015, Bengtsson Citation2024). Direct evidence of this new boatbuilding technology appears on the British Isles around 2000 BC, where it is commonly associated with the development of metal trade networks (Van de Noort Citation2006, Citation2009). The emergence of these networks is suggested by over 20 assemblages of bronze artefacts, dating between c. 1800–600 BC, found on the sea floor along the Irish Sea, English Channel and North Sea coasts, representing individual wrecking events () (Needham et al. Citation2013).

Fig. 1. Locations of plank-built vessels and bronze artefacts found on the seabed and hoards featuring Great Orme copper in north-western Europe (after Needham et al. Citation2013, Van de Noort Citation2009, William and Le Carlier de Veslund Citation2019). The Hjortspring boat, part of a war offering found in a bog in Als, Denmark, is the oldest substantial plank-built vessel from Scandinavia and indirectly 14C-dated to c. 350 BC (Rieck Citation1994).

In the Scandinavian Bronze Age (c. 1700–500 BC), the trade in metals, including copper, tin and gold, laid the foundation of new wealth and the formation of chiefdoms (Kristiansen and Larsson Citation2005, Kristiansen and Earle Citation2015, Ling et al. Citation2018). Whereas boats must have been involved in the importation of bronze metals into most parts of Scandinavia on account of its geography, the importance of a western maritime trade route is evident already from c. 2100 BC; Nørgaard et al. Citation2021). Recent research highlights the significance of British mines, in particular Great Orme in Wales, as a main supplier of copper in north-western Europe c. 1600–1400 BC () (William and Le Carlier de Veslud Citation2019, Nørgaard et al. Citation2021), and in the production of as much as c. 30 to 40% of Scandinavian bronzes (Johan Ling, personal communication 2024). Yearly consumption rates of bronze metal in Denmark alone c. 1500–1400 BC are estimated to have been between 1–2 tonnes with perhaps the double for Scandinavia as a whole (Ling et al. Citation2018, Horn et al. Citation2024). Set in relation to one ‘wreck’ assembly at Salcombe () constituting 40 tin and 280 copper ingots with a total weight of c. 80 kg (Wang et al. Citation2018) as representative of an average north-western bronze raw metal cargo during the Bronze Age, this might equate to between 10 and 20 boat loads per year arriving in Scandinaiva via the western sea routes during this period (Bengtsson Citation2024).

The potential wealth and status gained from building a boat capable of reaching places where metals could be acquired and brought back home would have provided an important incentive to drive boatbuilding technologies towards the construction of larger and more seaworthy plank-built vessels, as well as the development of improved methods of propulsion (Artursson Citation2013, Bengtsson Citation2015, Citation2017, Ling et al. Citation2018).

Any vessel engaged in this trade would have been built to cope with the more open sea conditions of the eastern and southern shores of the North Sea, and large enough to accommodate equipment needed to handle and maintain the boat, including sea anchors, ropes, bailers, repair materials, as well as personal equipment for the crew (food and utensils, water, warm clothes, tents for shelter, weapons for defence, etc.) in addition to any non-perishable produce used for trading for bronze metals and/or food along the route (Kaul Citation2003, Bengtsson Citation2017, Citation2024).

For these reasons, it is very likely that seafaring abilities and technologies in Western Europe and Scandinavia have been greatly underestimated in earlier archaeological research.

Although there is no direct archaeological evidence of Scandinavian BA plank-built boats, rich indirect evidence provided by e.g. rock art (Bengtsson Citation2015, Citation2017) and ship-settings (Artursson Citation2013, Wehlin Citation2013) does allow for some conjecture as to the development of boats, boatbuilding technologies and means of propulsion during this period- something which will be explored further in this paper.

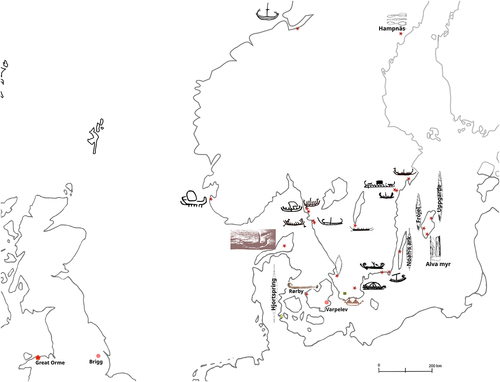

THE SCANDINAVIAN BOAT IMAGERY

Some 20,000 boat images carved into glacially smoothened rocks along the Scandinavian palaeogeological coasts and inland waterways bear witness to the importance of boats to contemporary BA society (Bengtsson Citation2003, Citation2015, Ling Citation2008). Within southern Scandinavian rock art, boat imagery remains the most common more complex type of figure, but is also found decorating grave chambers, engraved on bronze artefacts, as gold models and ship-like stone monuments or ship-settings, all of which are considered to share the same symbolic meaning () (Artelius Citation1996, Kaul Citation1998, Bradley et al. Citation2010, Bengtsson Citation2017). The likeness between, for example, rock carvings of swords, axes, and shields in comparison to actual contemporary artefacts (see Toreld Citation2012) suggests that the symbolic imagery is based on and often depicts truthful aspects of BA society, and the boat imagery is no exception (Kaul Citation2003, Kristiansen Citation2004, Ling Citation2012). Studied as a corpus across the region it is clear this boat imagery contains a wealth of information on different types and sizes of boats, used for fishing, transportation of people, animals, cargo and methods of propulsion () (Sognnes Citation2001, Bengtsson and Bengtsson Citation2011, Bengtsson Citation2017).

Fig. 2. Locations of some of the imagery, boats and artefacts featured in this article (after Bengtsson Citation2017, Citation2024).

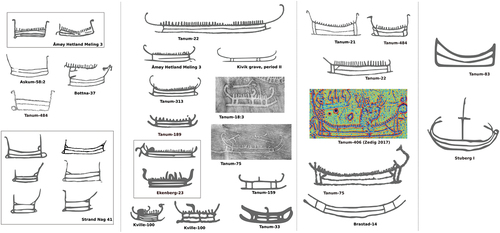

Fig. 3. Examples of rock carved boat imagery from southern Scandinavia (after Bengtsson Citation2015).

Fig. 4. Examples of boat imagery featuring methods of propulsion and steering devices. The Swedish imagery is named based on parish numbers in the Sweidish national monuments register whereas other imagery is named based on whichever system used in the documentation material they are collected from (see Bengtsson Citation2015, p. 146, Citation2017).

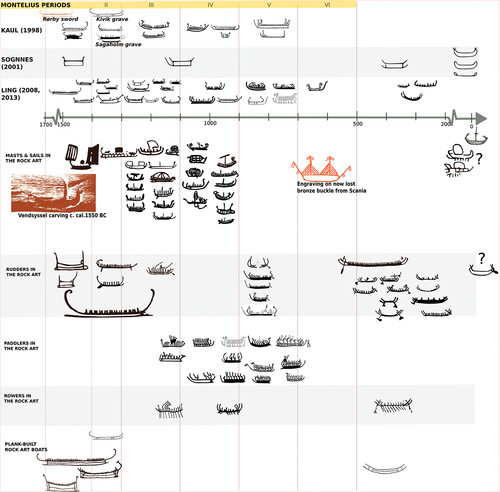

The prevalence of boat imagery within clearly datable grave contexts, has made it possible to create chronologies based on the artistic changes in and which the two horn projections at each end of the vessel are depicted (), which have been further refined using other relative dating methods including sea level dating, enabling some boat depictions to be dated within a mere 200 years () (Kaul Citation1998, Sognnes Citation2001, Ling Citation2008, Citation2013).

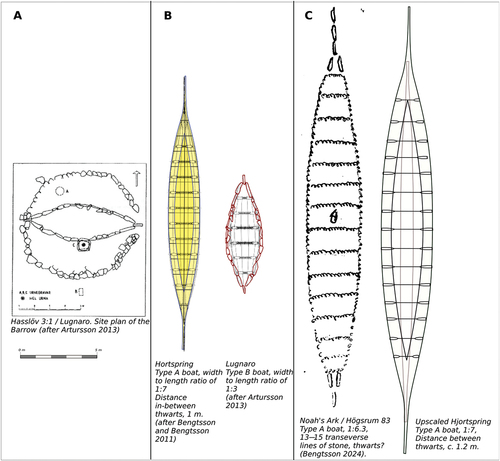

Fig. 5. A) Examples of BA Gotlandic ship-settings (Wehlin Citation2013, Skoglund and Wehlin Citation2013). B/D) Two Ölandic ship-settings featuring transverse lines and horn projections (after Bengtsson Citation2024). C) Bird’s-eye view of the Hjortspring boat (after Bengtsson Citation2024).

Fig. 6. Tentative chronology of rock art boats featuring technical details within the southern Scandinavian rock art, in comparison to established BA chronologies (after Bengtsson Citation2015, pp. 176, Citation2017, p. 87, Citation2024).

Whereas the rock carving tradition appears to be phased out during the Pre-Roman Iron Age (PRIA), the habit of erecting stone monuments in the shape of boats, so-called ship-settings, has a much longer continuity from when it first appears in the Late Neolithic until it disappears at the end of the Viking Age (Nicklasson Citation2005, Larsson Citation2007). Ship-settings are generally associated with graves and cemeteries, with those dated to the BA found under mounds, erected as solitary monuments or in groups (Artelius Citation1996). Whilst relatively few have been excavated, the BA ship-settings are often distinguishable in being built up by more closely placed stones forming a continuous line in-between bow and stern stone, or exhibiting lines of stones that appear to mimic the horn projections seen in the rock art () (Artelius Citation1996, Skoglund Citation2008, Artursson Citation2013, Wehlin Citation2013). Many are also of a more realistic size in comparison with ship-settings of later periods (Capelle Citation1995, Artursson Citation2013, Wehlin Citation2013).

Based on the above, many BA ship-settings can be dated on a typological basis, thereby providing evidence of the width-to-length ratio of the vessels they represent as well as other clues on how boats were constructed and propelled, be it a marked higher sheer line towards the endships, lines of stones perhaps marking seats for a paddling crew, or central postholes or large stones marking a mast and platforms or side rudders () (Artursson Citation2013, Skoglund and Wehlin Citation2013, Bengtsson Citation2024).

Thus, boat imagery and ship-settings appear to complement one another and can potentially help us form a more nuanced understanding as to the size, construction and methods of steering and propulsion that existed during the Bronze Age.

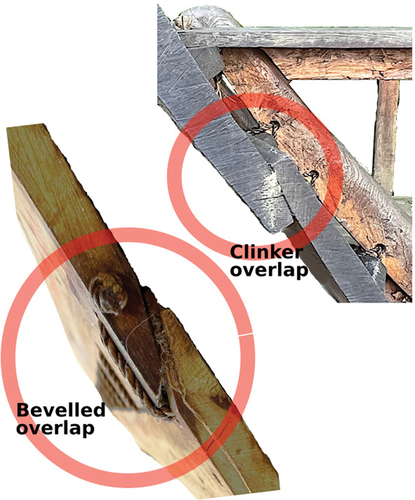

THE INDIRECT EVIDENCE FOR LARGE SAILED PLANK-BUILT BOATS IN BRONZE AGE SCANDINAVIA – ROCK ART AND SHIP-SETTINGS

The Nordic boatbuilding tradition with overlapping clinker boards that are strengthened with internal beams resulted in very light and mobile vessels (Christiansen et al. Citation1972, Hasslöf et al. Citation1972). This tradition can be traced back to c. 350 BC with the Hjortspring boat, the bevelled overlap () of which by many scholars is believed to be the precursor to the clinker tradition (see Bengtsson Citation2017, pp. 49–50), and represents a type of boat that was most likely spread across the region in the Bronze and Pre-Roman Iron Ages () (Crumlin-Pedersen Citation2003, Kastholm Citation2008). The Hjortspring boat has a bottom plank that is 15.4 metres long, further extended at each end with horn projections to reach a total length of c. 18 metres () (Valbjørn Citation2003a, Bengtsson Citation2024). This lightweight boat, weighing a mere 530 kilos, was found together with 16 paddles and two steering oars, one positioned at each end of the vessel (Rosenberg Citation1937, Crumlin-Pedersen and Trakadas Citation2003).

Fig. 7. The difference between a bevelled overlap as used on the Hjortspring boat and a clinker overlap as featured on the AD c. 320 Nydam 2. The upper side strake is overlapping the lower side strake from the outside as the hull shape is created, with a less distinct ‘step’ in the bevelled overlap. Photos. B. Bengtsson.

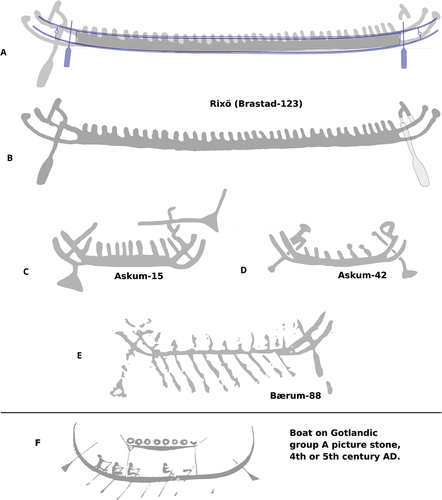

Fig. 8. A) An outline of the Hjortspring boat overlaying a carved boat from Rixö, west Sweden (after Bengtsson and Bengtsson Citation2011) B) The Rixö boat with forward steering oar reconstructed, C–E) Rock art boats with double steering oars from sites in Askum and Baerum (after Bengtsson Citation2015, p. 172), F) Boat on a group A pictures stone from Gotland, dated to 4th or 5th centuary AD, featuring double steering oars (after Varenius Citation1992, pp. 59–60).

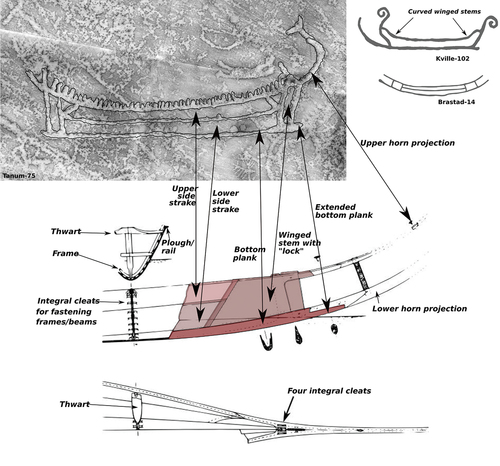

Fig. 9. Rubbing of boat from Tanum-75. Double arrowed lines identifying corresponding boat parts between carved boat and the Hjortspring boat (after Rosenberg Citation1937, Bengtsson Citation2017). The same boatbuilding method is mirrored in the two boats from Brastad and Kville.

Seen from the side, this vessel bears a striking resemblance to many boat depictions in both rock art and on bronzes dating to the Bronze Age. In one example from Rixö (Brastad-123), a rock art boat can be found that appears very similar to the Hjortspring boat, both in terms of silhouette and in the use of double steering oars, one at each end (). In the Rixö carving the forward steering oar and the human like figure holding on to it are both clearly visible, whereas the corresponding figure in the stern has been left unfinished (), leaving it to the imagination to complete the image (Bengtsson Citation2015, Citation2017). By comparing this boat with boat images from, for example, Askum-9 and Baerum-88 in Sweden and Norway, respectively, the interpretation of the Rixö carving as having double steering oars becomes justifiable (). In fact, this use of double steering oars can be traced back to Early BA in the boat imagery () and appears to have continued well into the 5th century AD, as evident by early Gotlandic picture stones () (Bengtsson Citation2015, p. 234).

Further evidence that rock art often depicts what can be interpreted as truthful representations of actual objects can be found at Tanum-75, where one vessel appears to illustrate the way in which the boat was built. In comparison with the boatbuilding technology employed on the Hjortspring boat, the rock carving gives the impression of having been made with a clear idea of the construction method, making it possible to identify parts for the bottom plank, sheer strakes, winged or v-shaped stems, upper and lower horn projections, whereas other details such as integral cleats, thwarts, etc., are not visible (). Strömberg (Citation1983) argues for the same boatbuilding method in relation to the Kville-102 boat (), here pointing towards the change in curvature of the upper strake at the endships as perhaps indicative of hollowed out winged stems, whereas the rock art boat from Brastad-14, possibly contemporary to the Hjortspring boat, more clearly mirrors this boatbuilding technology ().

Interestingly, the Kville-102 boat appears to have a higher freeboard at the two endships, something which would be advantageous in waves. However, the horn projections could have a similar role perhaps best demonstrated by the plough or rail feature that runs all around the upper side strakes, stems and upper horn projections on the Hjortspring boat, which is designed to deflect waves away from the boat (Bengtsson Citation2024). Some of the earliest rock art boats that could be of a plank-built construction can be found at Tanum-21, Tanum-484, Kville-100 and Strand-41 () (Fredsjö Citation1971, Bengtsson Citation2015, Melheim and Ling Citation2017).

The basic silhouette of both the Hjortspring boat and the Rixö boat carving, with a long, straight bottom plank and upper sheer strake, appears to represent a type of boat that existed right from the beginning of the BA, making it difficult to set a precise date on the Rixö carving (). One early example of this shape can be found at the Tanum-22 site in Bohuslän, located in an area of Scandinavia where the relative sea level has decreased by some 20 metres since the beginning of the Bronze Age, due to the complex land elevation process () (Bengtsson Citation2003, Ling Citation2008). Hence, this boat could only have been carved from around 1700 or 1600 BC once the rock had emerged from the sea (Ling Citation2008). This date of c. 1600 BC appears to match a very similar vessel exhibiting the same upwards and inwards ended upper horn projections that were incorporated into the design of one of the two Rørby swords during its casting process () (Kaul Citation1998). Further examples of this shape come from the c. 1400 BC Sagaholm barrow on Lake Vättern, where a total of six boats have been carved onto five slabs of sandstone enclosing its grave chamber () (Goldhahn Citation1999).

Fig. 10. Examples of depictions of potential plank-built vessels showing winged stems and/or planks. Tanum-406 after Zedig Citation2017 in the Swedish rock art research archives (SHFA Citation2024).

Fig. 11. Boat depictions on the Rørby sword and the Sagaholm barrow share the same basic shape as the Hjortspring boat seen from the side, suggesting a common boatbuilding technology throughout the BA.

The Sagaholm boats clearly demonstrate that the straighter Hjortspring type silhouette existed alongside more elaborate upper horn projections at the time this barrow was erected. It also suggests that upper and lower horn projections were simply added to what was most likely a basic construction of plank-built vessels of the time. The reason why the horns were added might include ease of landing and handling the boat and for attaching the double steering oars (Bengtsson and Bengtsson Citation2011). Thus, even though the fashion in horn projections changed throughout the BA, providing a useful dating tool, the basic boatbuilding method remained the same. The more rockered silhouette of the Hjortspring type boats of the PRIA, perhaps best illustrated by the boat carving from Brastad-14 (), could also represent a change in fashion in how boats were represented. This might also explain why only some BA ship-settings have rows of stones marking out these projections.

In some rock carvings a crew is clearly visible, seated or standing in boats (). In other imagery, the crew is instead indicated by short vertical lines extending upwards from the upper sheer strake of the boat depictions, so called crew lines, which in the past have been used to discuss aspects of crew organisation, and in comparison to ethnographic evidence of crew numbers (Fredsjö Citation1971, Østmo Citation1992, Ellmers Citation1995, Bradley Citation2008, Kastholm Citation2008, Ling Citation2008, Citation2012, Skoglund and Wehlin Citation2013) but rarely in relation to boat lengths, other than for arguing for a strict dimensional code in these boat depictions (Ling Citation2012).

Fig. 12. Symbolic boat imagery similar in shape to the Hjortspring boat (after Bengtsson and Olsson Citation2000, Bengtsson Citation2015, Goldhahn Citation1999, Högberg Citation1995, Kaul Citation1998, Ling Citation2008), A) Tanum-22, B) Rørby boat (after Kaul Citation1998), C) Boat, Sagaholm barrow, D) Boats from Kville with seated human figures, the aftmost holding on to a steering device, E) Crew holding paddles, F) Rowed vessel from Tanum, G) Two boats carvings from Tanum dated to c. 1600 BC, based on the shape of the upper horn projections, H) Two early BA boats from Tanum, I) Two early BA boats from Tanum.

That these lines represent an intentional way in which to depict a crew is suggested by the boat depiction on the Rørby sword. It has similar lines but executed in a way that suggests pairs of paddlers sitting on either side of each thwart as well as a single line at each end, representing the persons in charge of the two steering oars () (Østmo Citation1992, Ellmers Citation1995, Kastholm Citation2008, Ling Citation2008, Citation2012). This way of depicting a crew in pairs is also found on several early boat depictions at Tanum-311, -238 and -66, and might offer a more precise way of appreciating the relative size of depicted vessels, as each pair might be set in relation to a thwart () (Bengtsson Citation2017). If using the Rixö boat as an example and assuming these lines can indeed be taken to represent the crew, this boat would be carrying a crew of 38 (18 × 2 plus two on the steering oars). Compared to the Hjortspring boat which had only space for a sitting crew of 20 this would suggest that the Rixö carving is depicting a much larger vessel. By dividing the total length of the Hjortspring boat (14 metres excluding extended bottom plank/horn projections) with the number of crew/paddler pairs – 10 – and multiplying this with the number of crew pairs visible, for example, on the Rixö boat, we would get a simple equation of 25.2 m. Thus, the relative length of the boat depicted at Rixö in comparison to the Hjortspring boat would lie in the region of 25 metres and, when applying the same formula to the other boat depictions mentioned above, these are found to have comparable lengths of between 7 and almost 27 metres (). This is not dissimilar in length to many ship-settings dated to the Bronze Age (Artursson Citation2013, Wehlin Citation2013). Nor is it dissimilar to estimates of the size of early BA boat carvings in Bohuslän based on unpaired crew lines (Ling Citation2012). Despite the possibility that depicted boats might be carrying up to four or more people per thwarts (depending on the width of the boat), the depicted vessels here nonetheless suggest two groups of boats existed at the time, one smaller, at 4–9 metres long, and one larger, with boats between 21–42 metres long.

Table 1. Paired paddlers/crew lines and estimated boat lengths: a comparison between the Hjortspring boat and southern Scandinavian boat depictions dated to the BA.

Whilst paddlers, steering oars and plank-built vessels visible within the BA imagery can be extrapolated back in time from the not-too-distant Hjortspring boat, other visible details suggesting e.g., the use of oars and sail are more elusive. Firm evidence does not appear in the archaeological material until the Nydam and Oseberg ships of the 2nd and 9th c. AD (Bengtsson Citation2017, p. 51). Within the southern Scandinavian imagery, oars are only present in one or two BA boat depictions, with a further two dated to the PRIA (). Mast and sail-like attributes on the other hand, some of which can be interpreted as having yards and standing rigs (Burenhult Citation1973, Artursson Citation1987, Stölting Citation1996), can be found in most major rock carving areas, appearing on different types of boats throughout the period, and more widespread than, e.g., clearly depicted paddlers (Bengtsson Citation2015, pp. 164, 166). In addition, they appear on boat imagery in bronze and wood, the oldest carved onto a once living tree trunk from Vendsyssel, dated to c. 1550 cal. BC () (Bengtsson Citation2015, pp. 174, 175). Here, however, the ship-settings might provide additional evidence, not only with regards to how large and wide some of the Bronze Age vessels might have been, but also in relation to the potential use of sail.

Six ship-settings as examples of overall size and use of sail

It is a widely held assumption that, at the end of the Viking Age and Early Medieval period, at least two types of large vessels were used. One, a more narrow boat (type A), propelled by a combination of oars and sails that enabled it to move also when there was a lack of wind or when the wind direction was less favourable. The other, a wider type of vessel (type B), which was built primarily to maximize cargo capacity and which relied almost entirely on sails and favourable wind conditions in reaching its destination (Cederlund Citation1980, Rausing Citation1984, Artursson Citation2013). A typical width-to-length ratio for the type A vessel is cited as between 1:5–1:10, whereas the equivalent ratio for the cargo/type B vessel lies in the region of 1:2–1:4 (Cederlund Citation1980, Rausing Citation1984, Artursson Citation2013). Irrespectively of when the type A and B vessels first came into use, these width-to-length ratios are useful for assessing propulsion. Especially since a type B vessel would have a considerably larger displacement, and therefore require a larger crew to generate enough power to maintain speed in comparison to a type A vessel. BA rock art and the Hjortspring boat suggest paddles were preferred over oars, most likely because it is easier to use in the shallow and narrow waters these boats operated in (before, e.g., the advent of purpose-built harbours). It would also be a more natural partner to sail, should these have existed, in that paddles are more easily stowed away when the boats became too heavy or the distances too long and raising a sail became a relief.

The above ratios are useful to bear in mind when contemplating some of southern Scandinavia’s ship-settings, including the one found within the Lugnaro barrow in Halland, Sweden (). Excavated and reconstructed in 1926 and dated to c.800 BC, this barrow contained the carefully laid out contour of a ‘boat’, 7.7 metres long and 2.5 metres wide (Artursson Citation2013). A direct comparison between this boat and the Hjortspring boat suggest it might have had space for 10–12 paddlers, five to six per side ().

Fig. 13. A) The Lugnaro barrow, B) The relative size of Hjortspring and Lugnaro, C) Noah’s Ark and an upscaled Hjortspring boat (after Artursson Citation2013, Bengtsson and Bengtsson Citation2011, Bengtsson Citation2024).

This tallies the estimates of boat length in relation to visible crew lines presented in and would suggests that it is possible to make direct comparisons between depictions of boats and the boat shaped monuments of the BA. Another ship-setting worth considering in this regard is Noah’s Ark from Öland (). Although undated, it appears very similar to an upscaled version of the Hjortspring boat, while featuring 13–15 transverse hull lines. Without the horn projections this boat is around 22 metres long, which, divided by 1.4, translates into a crew of around 30–32. This is not dissimilar to what would be estimated if interpreting the transvers lines as indications of thwarts and would suggest it might represent a vessel similar in size to the Rørby boat ().

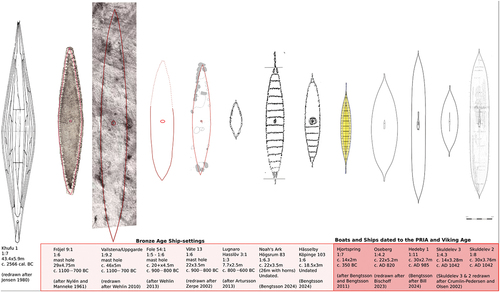

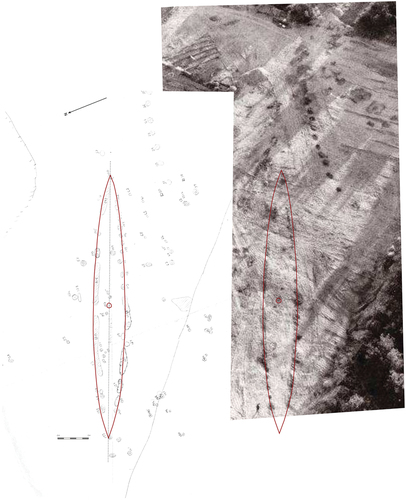

On Gotland there are over 400 known ship-settings dating to c.1200–700 BC. Of these about 17% have a width/length ratio of 1:5 or higher, thus falling within the longer and more narrow type A category boat, 11% of which can be classified to within a 1:6–1:10 category, i.e., a width-to-length ratio similar to the Hjortspring boat. Of the wider B type of boat with a lower width/length ratio, about 24% of the Gotlandic ship-settings fall within a ratio of between 1:3–1:4, whereas most ship-settings (75%) have a width/length ratio of 1:4 or below. Lengthwise, more than 50% of the Gotlandic ship-settings are between 7–13 metres long, which is in line with estimates for the average rock art boat and roughly equal to the length of British plank-built vessels such as the c. 1800 BC Ferriby 1 (15.9 m) and the c. 1500 BC Dover boats (c. 12 m) (Bradley Citation2008, Artursson Citation2013, Bengtsson Citation2024). Only 50 of the Gotlandic ship-settings exceed 16 metres in length (approximately 12%), 14 of which are more than twice that length. Of the 30 longest ship-settings (24–46 metres long), only four have a width-to-length ratio below 1:5, indicating that such large substantial vessels might have been rare (Wehlin Citation2013). These relationships are not dissimilar from the relationship between different size vessels in historic times.

It is often assumed that relatively narrow vessels such as the Hjortspring boat could not have been sailed, something which has conclusively been demonstrated as erroneous (Bengtsson and Bengtsson Citation2011). Nor can it be assumed that all vessels depicted in the rock art are similarly long and narrow. The large visual gallery of different types of boats displayed within the rock art is most likely mirrored by the large variation in the width-to-length ratios of the contemporary ship-settings. Thus, not only can relatively narrow vessels use sail as a means of propulsion, but the above ship-setting material suggest most plank-built vessels in the Bronze Age might have been relatively wide, of a type that for later periods are presumed to have been propelled primarily by sail.

Over 70 of Gotland’s 400 known ship-settings have been archaeologically investigated in the last century. Of these, only excavation methods from the mid-1950s onwards are considered modern, which coincides with the earliest record of centrally located postholes inside a ship-setting (Nylén and Manneke Citation1961). Early interpretations of this feature included the support of some symbolic construction used in connection with the burial ritual or a mast (Manneke Citation1967). Later, the term mast-pole or -hole is used unequivocally based on the clear spatial connection between ship-setting and posthole (Zerpe Citation2002) and can be found on not only one but four ship-settings, in time ranging between c. 1100–700 BC (). Many more might have existed, which the Fole ship bears witness to, half of which has been destroyed by modern quarrying activities (Wehlin Citation2013). What the four that are preserved have in common is that they are over 20 metres long and have a width-to-length ratio of over 1:5 (). In addition, with the exception of the Uppgarde boat of which only an outline remained at the time of discovery (), these boat monuments are shaped with stones that increase in height from the middle of the ‘side strake’ towards the stems, creating a silhouette evoking that of an actual boat as viewed from the side. In combination with other details that might be linked to construction details mirroring those on actual boats (Skoglund and Wehlin Citation2013, Wehlin Citation2013), it can be assumed that also the masts are marked out on these clearly very special monuments (Bengtsson Citation2017, p. 92). That it is masts that are marked out is made more likely in view of the many mast and sail like attributes on the boat carvings on rocks, bronze and on a tree dating to the same period ().

Table 2. Gotlandic ship-settings dated to the BA with central postholes.

Fig. 14. The length and width of ship-settings and relevant archaeological boat finds mentioned in the text (boats redrawn after Bengtsson and Bengtsson Citation2011, Bengtsson Citation2024, Bill Citation2024, Bischoff Citation2023, Crumlin-Pedersen and Olsen Citation2002, Jensen Citation1980, Nylén and Manneke Citation1961, Wehlin Citation2013, Zerpe Citation2002).

Fig. 15. Plan drawing and aerial photo of the Uppgarde ship with central posthole circled in red. Photo: Manneke (Citation1967), from Wehlin (Citation2010).

Whereas both Väte and Fole are similar in size to Noah’s Ark and might belong to the same size class as the Rørby boat, the ship-settings from Fröjel and Uppgarde are considerably longer. Are these two vessels exaggerated versions of ‘real’ boats or could they represent boats that were once used on nearby waters? In the rock art, the nearest equivalent discussed here is Tanum-22 which might have been around 26 metres long so, from that respect, these sizes might not be unrealistic. The boat from Uppgarde is only slightly longer than the 1500 years older Khufu 1 boat from Egypt (). Whilst Khufu 1 is an altogether different boat, being decked, having a higher freeboard, and endships with a considerable overhang in comparison to the kind of boat the Uppgarde ship-setting might represent, the comparable length of the two vessels suggests Uppgarde might be of a realistic size (Jenkins Citation1980). Another comparable size vessel we find chronicled in the Norse Sagas (Sturluson Citation2018, pp. 414–415) was the Long Serpent of King Olaf, built in c. AD 1000, which with its 34 rowing benches (equivalent to c. 48 m) was declared the best and most costly boat ever built in Norway. Thus, the answer to the question of whether these are realistic size vessels for BA Scandinavia comes down to whether the Scandinavian boatbuilding technology at the time might have been capable of producing such large vessels. Whichever the case, this same boatbuilding technology is very likely to have produced vessels that used sails as a complement to both paddling and rowing.

DISCUSSION: BA BOATS AND BOATBUILDING TECHNOLOGY

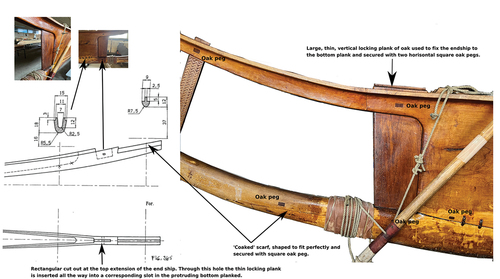

The craftmanship displayed by the building of the Hjortspring boat clearly shows it was built within a long boatbuilding tradition which the carved boat depictions suggest developed some time just before or at the onset of the Bronze Age in c. 1700 BC () (Melheim and Ling Citation2017). Details of the Hjortspring boat show a keen understanding of woodworking technologies that included an ability to make ‘coaked’ scarves (for explanation see machine drawing in ) strong enough to secure heavy horn projections and the fastening of winged stems onto a bottom plank, secured with square pegs of oaks (Valbjørn Citation2003a). These sophisticated scarves indicate an ability to also join two or more bottom planks (K. Valbjørn, personal communication, July 15, 2022, see also Wright Citation2015, for comparative examples from the UK).

Fig. 16. Details of Tilia Alsie in relation to a technical drawing (Valbjørn Citation2003, p. 40) of the lock assembly of the Hjortspring boat. Photos: B. Bengtsson.

On the British Isles, oak trees with boles measuring up to 23 metres existed well into the 14th century AD, whereas the Brigg and Varpelev logboats, both dated to c. 1000 BC, might have required oak boles measuring some 16 metres, as would the linden tree bole used for the bottom plank of the Hjortspring boat (Kastholm Citation2012, Wright Citation2015, Bengtsson Citation2024). These lengths provide an idea of how many scarves a bottom plank would have required, indicating that a Rørby type vessel might have needed at least one scarf depending on the availability of suitable trees.

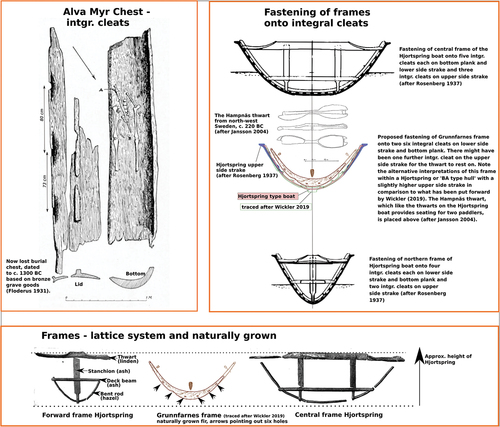

The use of integral cleats which is fundamental to the plank-building tradition can in Scandinavia be traced back to the c. 1300 BC oak chest from Alva Myr (bog) on Gotland, used for the burial of a male individual with accompanying bronzes providing the date () (Wehlin Citation2013). The lid of this chest () conveys a knowledge and an ability to use and carve out cleats in a material that is harder to work than the wood species usually associated with early Scandinavian boatbuilding technology such as linden and fir (Bengtsson Citation2024). The spacing in-between the opening of the holes running through the centre of these cleats are approximately 73–80 cm, 20–27 cm less than the spacing between frames on the Hjortspring boat. This, coupled with the cleats facing the outside of the lid, suggests it is not part of a boat as has been suggested in the past (Wehlin Citation2013, Kastholm Citation2015), but rather evidence for use of integral cleats in other contexts than that of boatbuilding () (Bengtsson Citation2024).

Fig. 17. The Alva Myr chest and BA type frames to scale (Floderus Citation1931, Bengtsson Citation2024).The Alva Myr chest and BA type frames and thwarts to scale (after Bengtsson Citation2024, Floderus Citation1931, Jansson Citation1994, Rosenberg Citation1937, Wickler Citation2019).

As for internal frames, used to stiffen the hull ‘shell’, the intricate lattice system of bent hazel rods, beams and stanchions as found on the Hjortspring boat and the naturally grown frame from Grunnfarnes in northern Norway, indicate that at least two systems were used alongside in the 4th century BC () (Valbjørn Citation2003a, Wickler Citation2019, Bengtsson Citation2024). The lattice frame system might at first appear less sturdy than a grown frame, but attached to the many internal cleats on the vessel along with the thwart it produces a strong, light and flexible frame that effectively transfers stresses from crew as well as rig and sail across a larger area (Valbjørn Citation2003a, Bengtsson and Bengtsson Citation2011). A heavier grown beam on the other hand might allow for a more open inside hull structure, which could also potentially make it easier to carry large cargoes or to stow away, e.g., oars while sailing (). Furthermore, stress tests of sewn joints, such as those that might have been used on the Hjortspring boat, in combination with the evidence of scarves, the number of integral cleats and their individual tensile strength, and available size trees do not contradict the existence of Rørby sized vessels or larger during the BA (Valbjørn Citation2003a, Citation2003b).

When contemplating the bird’s eye view of the ship-settings discussed here in relation to some of the earliest actual archaeological finds of sailed vessel in Scandinavia – including the Oseberg, the Hedeby 1 and the Skuldelev 2 and 3 ships, dated to between c. AD 820–1042 () – it is striking how similar they are. These similarities include the width-to-length relationship as well as the positioning of central post holes in relation to actual mast steps.

Returning then, to the Uppgarde ship-setting, which, with its impressive size and early date, might be regarded as the only unrealistic vessel the indirect BA boat material presented here provide evidence of. Three things are worth considering: firstly, the Uppgarde boat is located near what around 1000 BC might have been a natural harbour, connected to the sea by the Gothem river, and surrounded by what appear to have been one of the richest areas on Gotland at the time, which also included fortifications (Wehlin Citation2010). Secondly, the features of the ship-settings discussed here suggest they are intended to represent actual boats. The role of the ship-setting, apart from commemorating the past, the deceased, might also look to the future to preserve the shape and form of the ship for future generations. Thirdly, the Long Serpent, the priced and unique ship of King Olof (Sturluson Citation2018, pp. 425, 439) is described as the product of a great mind, suggesting not only wealth would be needed to build such a vessel but also a rare mind, a boatbuilder capable of conceiving and crafting such a vessel from whatever means he had at his disposal. Such a combination of wealth, mind and skill must have been exceedingly rare throughout history. Still, is it inconceivable that on such a wealthy island as Gotland in the first millennium BC, one particularly successful chieftain managed to amass resources, find a great mind to build his boat and then to commemorate it for posterity? We leave this question open for now.

Regardless of how big any one vessel might have been, the available indirect evidence of boats, boatbuilding technologies and methods of propulsion within both pictorial and monumental evidence, some of which can be directly related to features and proportions of actual archaeological boat finds, would suggest this material is not coincidental but might actually convey details of existing seafaring technologies in the Scandinavian Bronze Age.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that the Bronze Age boat imagery in southern Scandinavia depicts plank-built vessels of a type that belonged to the same boatbuilding tradition as the c. 350 BC Hjortspring boat. More importantly, aspects of this boat imagery can be directly related to the contemporary ship-settings, suggesting use of sail and the existence of boats that from stem to stem (excluding horn projections) might have been in the region of up 20–30 metres or perhaps even larger. The correlation in time between this material and new research stressing the importance of a western maritime trade route, potentially connecting Scandinavia with the British Isles already by 2100 BC and more intensely c. 1600–1500 BC could signify a period in time of great innovation in seafaring technologies within the region that might also have included the use of sail.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Artelius, T., 1996. Långfärd och Återkomst - skeppet i bronsålderns gravar. Thesis (PhD). Gothenburg University.

- Artursson, M., 1987. Mast-, rigg- och segelliknande konstruktioner på Götalands Hällristningsskepp. Thesis (BA). University of Lund.

- Artursson, M., 2013. Ships in stone: ship-like stone settings, war canoes and sailing ships in bronze age southern scandinavia. In: S. Bergerbrant and S. Sabatini, eds. Counterpoint: Essays in Archaeology and Heritage Studies in Honour of Professor Kristian Kristiansen. BAR International Series, 2508. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 499–504.

- Bengtsson, B., 2003. The southern Scandinavian rock carvings. A synthesis of past interpretations and the introduction of a maritime perspective. Thesis (MA). University of Southampton.

- Bengtsson, B., 2015. Sailing rock art boats. A reassessment of seafaring abilities in Bronze Age Scandinavia and the introduction of sail in the North. Thesis (PhD). University of Southampton.

- Bengtsson, B., 2017. Sailing rock art boats. A reassessment of seafaring abilities in Bronze Age Scandinavia and the introduction of the sail in the North. In: BAR international series, 2865, Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Bengtsson, B., 2024. Using direct and indirect evidence of boats and boatbuilding for understanding the nature of seafaring in atlantic europe c. 5000–500 BC. In: B. Cunliffe et al., eds. Maritime Encounters 1. Presenting counterpoints to the dominant terrestrial narrative of European prehistory. Oxford: Oxbow Press.

- Bengtsson, B., and Bengtsson, B., 2011. Sailing rock art boats – a report on sail trials in bronze age type boats. Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 6 (1), 37–73. 10.1007/s11457-011-9077-2

- Bengtsson, L., and Olsson, C., eds. 2000. World heritage area’s central part and grebbestad. Tanumshede: Vitlycke Museum.

- Bill, J., 2024. The longship from Haithabu harbour [online]. Available from: https://www.vikingeskibsmuseet.dk/en/professions/education/the-longships/findings-of-longships-from-the-viking-age/the-longship-from-haithabu-harbour [Accessed 14 May 2024].

- Bischoff, V., 2023. The Oseberg ship. Reconstruction of form and function. Roskilde: The Viking Ship Museum.

- Bradley, R., 2008. Ship-settings and boat crews in the Bronze Age of Scandinavia. In: J. Goldhahn, ed. Gropar och Monument: en vänbok till Dag Widholm. Högskolan i Kalmar: Kalmar: Humanvetenskapliga institutionen, pp. 171–184.

- Bradley, R., Skoglund, P., and Wehlin, J., 2010. Imaginary vessels in the late bronze age of Gotland and south Scandinavia: ship settings, rock carvings and decorated metalwork. Current Swedish Archaeology, 18 (1), 79–103. doi:10.37718/CSA.2010.08

- Burenhult, G., 1973. Rock carving chronology and rock carving ships with sails. Meddelanden från Lunds universitets historiska museum, 1971–1972, 151–162.

- Capelle, T., 1995. Bronze-Age Stone Ships. In: O. Crumlin-Pedersen and B.M. Thye, eds. The ship as a symbol. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark, Department of Archaeology and Early History, pp. 71–75.

- Cederlund, C.O., 1980. Bulverketbåten – en modell for dokumentation av båt- och fartygslämningar. Fornvännen, 75, 30–43.

- Christiansen, S.E., et al. 1972. Boatbuilding tools and the process of learning. In: O. Hasslöf, ed. Ships and shipyards – sailors and fishermen. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, pp. 235–259.

- Crumlin-Pedersen, O., 2003. The Hjortspring boat in a ship-archaeological context. In: O. Crumlin-Pedersen and Trakadas, A., eds. Hjortspring. A pre-roman Iron-Age warship in context. Roskilde: The Viking Ship Museum, pp. 209–233.

- Crumlin-Pedersen, O., and Olsen, O., eds. 2002. The Skuldelev ships I. Roskilde: The Viking Ship Museum.

- Crumlin-Pedersen, O., and Trakadas, A., 2003. Hjortspring. A pre-roman iron age. Roskilde: The Viking Ships Museum.

- Ellmers, D., 1995. Crew structure on board Scandinavian vessels. In: O. Olsen, ed. Shipshape. Essays for Ole Crumlin-Pedersen on the occasion of his 60th anniversary February 24th 1995. Roskilde: The Viking Ship Museum, pp. 231–240.

- Floderus 1931, and Fredsjö, Å., Ett gotländskt ekkistefynd från bronsåldern. Fornvännen, 26, 284–290.

- Fredsjö, Å., 1971. Hällristningar. Kville härad i Bohuslän, Svenneby socken. Göteborg: Fornminnesföreningen i Göteborg.

- Goldhahn, J., 1999. Sagaholm – hällristningar och gravritual. Thesis (PhD), University of Umeå.

- Hasslöf, O., 1972. Main principles in the Technology of Ship-Building. In: O. Hasslöf, et al., ed. Ships and Shipyards – Sailors and Fishermen. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, pp. 27–72.

- Högberg, T., 1995. Arkeologisk rapport 1 från Vitlyckemuséet - Litsleby, Tegneby & Bro, Tanums socken. Uddevalla: Bohusläns museum.

- Horn, C., et al. 2024. Nordic bronze age economies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jansson, S., 1994. Nordsvensk Hjortspringbåd? Marinarkæologisk Nyhedsbrev fra Roskilde, 2, 16–17.

- Jenkins, N., 1980. The boat beneath the pyramid. King Cheops’ royal ship. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Kastholm, O.T., 2008. Skibsteknologi i bronzealder og jernalder. Nogle overvejelser om kontinuitet og diskontinuitet. Fornvännen, 103 (3), 165–175.

- Kastholm, O.T., 2012. Stammebåden fra Varpelev og dens europæiske slægtninge. Køge Museums Årbog, 39–52.

- Kastholm, O.T., 2015. Plankboat skeuomorphs in Bronze Age logboats: a Scandinavian perspective. Antiquity, 89 (348), 1353–1372. doi:10.15184/aqy.2015.112

- Kaul, F., 1998. Ships on bronzes. In: Religion and Iconography, Vol. 3, Copenhagen: The National Museum.

- Kaul, F., 2003. The hjortspring find. the oldest of the large nordic ware booty sacrifices. In: L. Jørgensen, B. Storgaard, and L. Gebauer Thomsen, eds. The spoils of victory. the north in the shadow of the roman empire. København: Nationalmuseet, pp. 212–223.

- Kristiansen, K., 2004. Seafaring voyages and rock art ships. In: P. Clark, ed. The Dover Bronze Age boat in context – society and water transport in prehistoric Europe. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 111–121.

- Kristiansen, K., and Earle, T., 2015. Neolithic versus Bronze Age social formations: a political economy approach. In: K. Kristiansen, L. Šmejda, and J. Turek, eds. Paradigm found. archaeological theory – present, past and future. essays in honour of evžen neustupný. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 234–247.

- Kristiansen, K., and Larsson, B., 2005. The rise of Bronze Age society. travels, transmissions and transformations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Larsson, G., 2007. Ship and society. Maritime ideology in late Iron Age Sweden. Thesis (PhD). Uppsala University.

- Ling, J., 2008. Elevated rock art. Towards a maritime understanding of rock art in northern Bohuslän, Sweden. Thesis (PhD). Gothenburg University.

- Ling, J., 2012. War canoes or social units? human representation in rock-art ships. European Journal of Archaeology, 15 (3), 465–485. doi:10.1179/1461957112Y.0000000013

- Ling, J., 2013. Rock art and seascapes in Uppland. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Ling, J., Earle, T., and Kristiansen, K., 2018. Maritime mode of production. raiding and trading in seafaring chiefdoms. Current Anthropology, 59 (5), 488–524. doi:10.1086/699613

- Manneke, P., 1967. Restaureringen av skeppssättningen vid Gannarve i Fröjel. Gotländskt Arkiv, 43–52.

- McGrail, S., 2007. Early seafaring in northwest europe: plank boats, log boats and hide boats. The Mariner’s Mirror, 93 (4), 441–449. doi:10.1080/00253359.2007.10657040

- Melheim, L., and Ling, J., 2017. Taking the stranger on board, north meets South. In: P. Skoglund, J. Ling, and U. Bertilsson, eds. Theoretical Aspects on the Northern and Southern Rock Art Traditions in Scandinavia. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 59–86.

- Needham, S., Parham, D., and Frieman, C.J., 2013. Claimed by the Sea: Salcombe, Langdon Bay, and other marine finds of the Bronze Age. In: Council for British Archaeology Research Report, Vol. 173, York: Council for British Archaeology. doi:10.5284/1081830

- Nicklasson, P., 2005. En vit fläck på kartan - norra Småland under bronsålder och järnålder. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Nørgaard, H.W., Pernicka, E., and Vandkilde, H., 2021. Shifting networks and mixing metals: changing metal trade routes to Scandinavia correlate with Neolithic and bronze age transformations. Public Library of Science ONE, 16 (6), e0252376. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0252376.

- Nylén, E., and Manneke, P., 1961. Gotland, Fröjel sn. Gannarve. Rapport rörande restaurering av skeppssättning. Archive of the Swedish National Heritage Board (ATA), Dnr, 4724/61.

- Østmo, E., 1992. Helleristninger i et utkanskströk. Bidrag til skipshistorien fra nye jeralderristninger på Dalbo i Bærum. In: Varia, Vol. 24, Oslo: Universitetets Oldsaksamling.

- Rausing, G., 1984. Prehistoric boats and ships of northwestern Europe. some reflections. från forntid och medeltid, 8. Lund: University of Lund.

- Rieck, F., 1994. The Iron Age Boats from Hjortspring and Nydam – New Investigations. In: C. Westerdahl, ed. Crossroads in Ancient Shipbuilding. Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Boat and Ship Archaeology, Roskilde 1991. Oxford: Oxbow, 45–54.

- Rosenberg, G., 1937. Hjortspringfundet. In: Nordiske Fortidsminder. København: Gyldendalske Boghandel, Vol. 3, p. 1.

- Skoglund, P., 2008. Stone ships: Continuity and change in Scandinavian prehistory. World Archaeology, 40 (3), 390–406. 10.1080/00438240802261440

- Skoglund, P., and Wehlin, J., 2013. A bronze age ship made of stone: record and analysis of a ship setting from lau, gotland. In: S. Bergerbrant and S. Sabatini, eds. Counterpoint: Essays in Archaeology and Heritage Studies in Honour of Professor Kristian Kristiansen. BAR International Series, 2508. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 491–498.

- Sognnes, K., 2001. Prehistoric Imagery and Landscapes. Rock art in Stjørdal, Trøndelag, Norway. In: BAR International Series. Oxford: Archaeopress, 998.

- Stölting, S., 1996. Überlegungen zu Felsbildschiffen mit Mast oder Segel. Adoranten, 1996, 31–35.

- Strömberg, H., 1983. Båttyper på hällsritningar i Kville: ett inlägg i diskussionen om hällristningsbåtarnas konstruktion. Uddevalla: Bohusläns Museum, pp. 21–48.

- Sturluson, S., 2018. Norse sagas. E-artnow: Kindle Edition.

- Toreld, A., 2012. Svärd och mord – nyupptäckta hällristningsmotiv vid Medbo i Brastad socken, Bohuslän. Fornvännen, 107 (4), 241–252.

- Valbjørn, K.V., 2003a. Hvad Haanden former er Aandens Spor. Nordborg: Hjortspringlaugets Forlag.

- Valbjørn, K.V., Crumlin-Pedersen, O., 2003b. Boatbuilding. In: A. Trakadas, ed. Hjortspring. A pre-roman iron-age warship in context. Roskilde: The Viking Ship Museum, pp. 70–83.

- Van de Noort, R., 2006. Argonauts of the North Sea – a social maritime archaeology for the 2nd millennium BC. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 72, 267–287. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00000852

- Van de Noort, R., 2009. Exploring the ritual of travel in prehistoric Europe, the Bronze Age sewn-plank boats in context. In: P. Clark, ed. Bronze age connections. cultural contact in prehistoric Europe. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 159–175.

- Van de Noort, R., et al. 2014. Morgawr, an experimental Bronze Age-type sewn-plank craft based on the Ferriby boats. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 43 (2), 292–313. doi:10.1111/1095-9270.12058

- Varenius, B., 1992. Det nordiska skeppet. Teknologi och samhällsstrategi i vikingatid och medeltid. Thesis (PhD). Stockholm University.

- Wang, Q., Strekopytov, S., and Roberts, B.W., 2018. Copper ingots from a probable bronze age shipwreck off the coast of Salcombe, Devon, composition and microstructures. Journal of Archaeological Science, 97, 102–117. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.07.002

- Wehlin, J. 2010. Approaching the gotlandic bronze age from sea future possibilities from a maritime perspective. In: M., Martinsson-Wallin. ed. Baltic Prehistoric Interactions and transformations: the neolithic to the bronze age. Gotland University Press, Vol. 5, pp. 89–100.

- Wehlin, J., 2013. Baltic stone ships. monuments and meeting places during the late Bronze Age. Thesis (PhD). University of Gothenburg.

- Wickler, S., 2019. Early boats in scandinavia, new evidence from early iron age bog finds in arctic norway. Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 14 (2), 183–204. doi:10.1007/s11457-019-09232-1

- William, R.A., and Le Carlier de Veslud, C., 2019. Boom and bust in Bronze Age Britain: major copper production from the Great Orme mine and European trade, c. 1600–1400 BC. Antiquity, 93 (371), 1178–1196. 10.15184/aqy.2019.130

- Wright, E., 2015. North Ferriby and the Bronze Age boats. Abingdon: Routhledge.

- Zedig, H., 2017. 3D-visualisering av L1967:2411, SHFA [online]. Available from: https://shfa.dh.gu.se/image/132078 [Accessed 13 May 2024].

- Zerpe, L. 2002. Arkeologisk undersökning. Skeppssättning RAÄ 13, Gräne 5:1, Väte socken 1998. Unpublished report stored at Gotland Museum’s topographical archive, Visby.