?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Recent advancements in reactor designs could offer new revolutionary capabilities, including remote monitoring, increased flexibility, and reduced operation and maintenance costs. Embracing new digital technologies would allow for operational concepts such as semiautonomous or near-autonomous control, and two-way communications for real-time integration with the upcoming smart electric grid. However, such continuous data transmission from and toward a reactor site could potentially introduce new challenges and vulnerabilities, necessitating the prioritization of cybersecurity.

Conventional information technology–based encryption schemes, which rely mostly on computational complexity, have been shown to be vulnerable to cyberattacks. With the advent of quantum computing, practically any asymmetric encryption could be potentially compromised. For example, it has been shown that a RSA-2048 bit key could be broken in 8 h.

To address this challenge, we explore the feasibility of quantum key distribution (QKD) to secure communications. QKD is a physical layer security scheme relying on the laws of quantum mechanics instead of mathematical complexity. QKD promises not only unconditional security but also detection of potential intrusion, as it allows the communication parties to become aware of eavesdropping. To test the proposed hypothesis, a novel simulation tool (NuQKD) was developed to allow for real-time simulation of the BB84 QKD protocol between two remote terminals. A reference scenario is proposed, generic enough to cover various internal and external communication links to a reactor site. Using NuQKD, the internal and external data links were modeled, and receiver operating characteristic curves were calculated for various QKD configurations.

A performance analysis was conducted, demonstrating that QKD can provide adequate secret key rates with low false alarms and has the potential of addressing the nuclear industry’s high standards of confidentiality for distance lengths up to 75 km of fiberoptics. Using a conservative estimation, QKD can provide up to 21.5 kbps of secret key rate for a distance of 1 km and 14.4 kbps at 10 km. The target secret key rates for the corresponding links were estimated at 16 kbps and 80 bps, respectively, based on the analysis of real data from a PUR-1 fully digital reactor. Consequently, QKD is shown to be compatible with existing and future point-to-point reactor communication architectures. These results motivate further study of quantum communications for nuclear reactors.

I. INTRODUCTION

The nuclear industry is embarking on a transformation that will result in a more reliable and efficient new generation of advanced reactors, the success of which will eventually determine its future. Advanced reactors are being proposed with new capabilities and will need to be compatible with digital and two-way communication technologies focused on optimizing plant operation. For instance, several proposed modern designs consider the possibility of remote and semi-autonomous operations.

To be successful, however, new reactors should also have the capability of being integrated into a modern electrical power grid. The smart grid would make use of information technologies, instead of being based on the conventional, one-directional power flow of today. In other words, the smart grid would constitute an interconnected system of distributed energy sources powered by two-way information and communication systems. Despite the advantages, the smart grid would impose an additional layer of complexity, introducing new challenges that are not yet fully understood.

Further challenges are added to the instrumentation and control (I&C) systems of advanced reactors, since continuous data transmission would be required throughout their operation. It might also introduce new vulnerabilities as a result of networking complexity. The recent rise in cyberattacks targeting I&C systems indicates the rapid evolution of attack technologies and further emphasizes the importance of cybersecurity. It becomes clear that the transition to a new model of power generation and distribution will only become beneficial given undisrupted and fully secured information and communication flow.

However, conventional security for information technology (IT) systems is based on classical encryption schemes. Since these rely on the computational complexity of certain mathematical functions to secure the transmitted data, they are only valid under certain assumptions regarding the adversary’s computational capabilities and strategy. Even if these assumptions might be fulfilled for the time being, it is not guaranteed that they will be relevant in the future, given the exponential rise in available computational power, the increased sophistication of cyberattacks, and the advent of quantum computers.[Citation1]

A promising novel method to address this challenge and ensure secure communications is quantum key distribution (QKD).[Citation2] Introduced theoretically about 4 decades ago, QKD could improve the level of communication security and has already attracted attention from various critical areas, including national defense, finance, and government. Various countries have proposed plans to build QKD networks to ensure safe transmission and privacy of data.[Citation3] Despite the promise for better security, limited research has been performed for the practical application of QKD technology in the nuclear industry.

Nuclear reactors today are based on technology that was mainly developed for one-way power flow from a large power plant to customers at the receiving end. However, modernization of the electric power grid and transition to renewable sources of energy and storage requires integration with the communication infrastructure. The smart grid will unavoidably include a collection of information using sensors and devices from multiple stakeholders and information sources that are interconnected and could include operations, transmission, distribution, electricity generation, process heat flow, markets, customers, service providers, etc. Each information source will have sensors and devices that perform online equipment monitoring, monitoring of the interconnections, load conditions, environmental conditions, etc. shows the key information and process flows, and highlights the highly asymmetric networks that will constitute the grid.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of microreactor integration to the smart grid (after Ref. [Citation4]). An advanced reactor processes information from sensors outside the site boundary (coming from the grid), and also sends information to the operations centers. Information from field sensors and devices within the site boundary is processed simultaneously to ensure the safety and reliability of the reactor itself. Each of these data flows has its own priority and security needs (e.g., command and control signals from the operations would require potentially secure communication channels).

![Fig. 1. Schematic representation of microreactor integration to the smart grid (after Ref. [Citation4]). An advanced reactor processes information from sensors outside the site boundary (coming from the grid), and also sends information to the operations centers. Information from field sensors and devices within the site boundary is processed simultaneously to ensure the safety and reliability of the reactor itself. Each of these data flows has its own priority and security needs (e.g., command and control signals from the operations would require potentially secure communication channels).](/cms/asset/ff967bc2-d044-49fe-b30a-e53f451ff9b5/unct_a_2368977_f0001_oc.jpg)

Potential risks associated with this architecture include (1) greater complexity that can increase exposure to adversaries, (2) interconnected networks that could introduce common vulnerabilities and increased opportunities for denial of service (DoS) attacks, and (3) two-way information flows that could increase the number of entry points and the introduction of malicious codes or compromised hardware.

These risks are exacerbated when applied to critical infrastructure, such as nuclear environments, that have different security requirements than the IT sector. For example, while in IT computer system confidentiality is the highest security priority, in operational technology (OT) systems, availability is typically prioritized.[Citation5] This is justified since any critical infrastructure system is expected to minimize operational disruptions to avoid availability implications. In addition, these systems serve a safety purpose that necessitates a higher degree of reliability. For instance, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s Regulatory Guide 5.71[Citation6] classifies reactor systems into safety and nonsafety, with different security requirements for each system (e.g., separating the two corresponding networks and limiting bidirectional communication).

A review of the most notable cyberattack incidents in recent history targeting critical infrastructure can provide useful insights into cybersecurity vulnerabilities and could potentially lead to valuable observations for dealing with future attacks by revealing existent patterns in cybercriminal activity. A timeline of the most discussed attacks targeting nuclear facilities is presented in . In , notable cyberattack incidents against nonnuclear critical infrastructure are also included.

TABLE I Publicly Available Cyber Incidents in Nuclear Facilities

Fig. 2. Timeline of cybersecurity incidents targeting critical infrastructure (after Ref. [Citation16]).

![Fig. 2. Timeline of cybersecurity incidents targeting critical infrastructure (after Ref. [Citation16]).](/cms/asset/bce77b18-065d-402f-8ab9-cca3928be3a1/unct_a_2368977_f0002_oc.jpg)

Past I&C attacks appear to be sophisticated, in the sense that they employ a combination of discrete attack types. The last decade has seen an increased number of cyberattacks against critical infrastructure, including nuclear facilities. The attacks exploiting system vulnerabilities not previously disclosed are known as zero-day attacks. According to the M-trends 2022 special report published by the Mandiant Group,[Citation7] zero-day exploitations have seen an exponential increase during the last decade (2012 to 2022). Such a trend also signifies an exponential increase in the level of cyberattack sophistication. Modern threats are also multivectored and exploit not one but any available means of propagation into the infiltrated system. While the simpler, more loosely protected networks of the past made uncomplicated attacks possible (DoS, delayed transmission, etc.), the modern era of cyberattacks is characterized by evasive, resilient, and complex threats (e.g., ransomware).[Citation8]

In this paper, we evaluate not only whether QKD can offer better security, but also which QKD solution would be the most efficient in a nuclear environment and in which communication links of a nuclear reactor would QKD be beneficial. For this reason, we analyzed the communication requirements of a generic nuclear reactor. NuQKD,[Citation17] a novel tool capable of simulating real-world QKD experiments, was used to identify the performance of a QKD scheme for various conditions and parameters in a nuclear I&C system. In order to explore the feasibility of such an implementation for nuclear reactor communications, a nuclear reactor reference scenario was developed, inspired by the networking features of advanced reactor designs. The performance of a QKD application at the data links described in the reference scenario was evaluated using NuQKD for multiple parameter combinations.

II. QUANTUM COMMUNICATIONS

Information in today’s critical infrastructure is primarily protected through encryption. Communication systems in I&C and Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition systems (SCADA) are based on classical encryption schemes. Classical cryptography offers two ways to ensure security of information: private (symmetric) and public (asymmetric) key encryption. However, both of these techniques suffer from shortcomings. Public encryption is based on computational complexity, meaning that the security of the communication depends on the complexity of mathematical functions. As standard computational power is increasing, and with the progress in quantum computing, the security of data exchange could be vulnerable.

For this reason, new techniques have been proposed that follow the concept of “security by design,” such as implementing physical barriers to cyber threats. On the other hand, private key encryption requires a secure key distribution process. The issue of distributing the symmetric key among the communication parties has been a fundamental problem for the implementation of any secure private key encryption scheme.

Two major challenges arise when it comes to the communications of critical infrastructure: The first challenge has to do with generating a truly random key that cannot be traced back to any mathematical function, even with the infinite computational means available to an eavesdropper. The second challenge is related to how one can ensure the secure transmission of a private key between the communication parties in a way that it cannot be compromised regardless of the means available to an attacker. The implementation of QKD provides a way to address both challenges at the same time.

II.A. QKD Fundamentals

Even though QKD was introduced theoretically 4 decades ago, it has recently gained increased attention due to quantum hardware advancements that have allowed commercial applications and recent progress in quantum computing, indicating that conventional encryption techniques could be potentially vulnerable.

Quantum key distribution first appeared in 1984 when Charles Bennett and Gilles Brassard introduced the BB84 protocol.[Citation18] The authors demonstrated that the uncertainty principle could be exploited to detect an eavesdropper if polarized photons were used for digital information transmission. QKD is an unconditionally secure scheme, a claim structured on a relatively straightforward physical principle: When nonorthogonal quantum states are used to encode data, unlike classical communications, information cannot be accessed without additional information related to the quantum state formation. If such a thing is attempted, the decoded data would be random. In the case of polarized photons, the additional required information refers to polarization bases.[Citation17,Citation18]

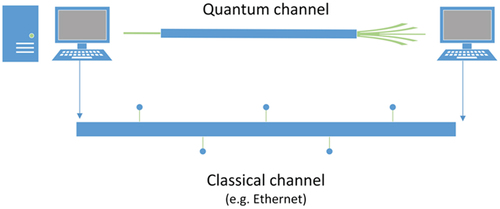

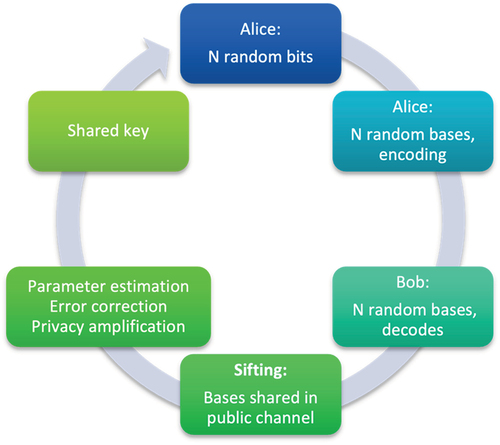

A QKD system in its most generic form is a point-to point architecture consisting of the sender (Alice), the receiver (Bob), and the QKD link connecting them (). The QKD link includes a quantum channel (transmitting encoded qubits/polarized photons) and a classical channel (follow-up communications, key distillation, encryption). An eavesdropper attempting to interfere with the transmitted qubits would disturb the quantum states, which would lead to the attack being detected. The classical channel procedures include sifting, parameter estimation, error reconciliation, and privacy amplification. When processing is completed, the two parties should have access to an identical, truly random secret key that can be used for data encryption using symmetric algorithms (e.g., OTP, AES, etc.). The iteration performed for each key distribution is demonstrated schematically in .

Quantum key distribution schemes employ optical fiber or free space as the quantum channel. The optical fiber has been proven more reliable due to low losses and high stability, and has been evaluated for communication distances up to 600 km.[Citation19] However, optical fiber exhibits issues when deployed in unusual terrains and cannot exceed transmission distances of such an order of magnitude due to signal degradation. On the other hand, free space has been used as a quantum medium for air-to-ground, satellite, and underwater QKD communications. Since the channel losses propagate quadratically instead of exponentially, free space should enable longer transmission distances than fiber under certain circumstances.[Citation3]

Protocol BB84 belongs to the group of discrete variable QKD protocols.[Citation18] Even though multiple protocols have been introduced in the decades following its introduction,[Citation20,Citation21] BB84 remains relevant as its core is widely used in commercial QKD applications (e.g., Decoy-State BB84, etc.). The quantum channel involved can be either optical fiber or free space,[Citation22] while the information is encoded in qubits using the polarization of transmitted single photons. The photons are polarized using either the rectilinear basis (0- and 90-deg states) or the diagonal basis (+45- and −45-deg states). Based on this, a block of N qubits is encoded, as shown in EquationEq. (1)(1)

(1) , in one of the four quantum states,

The first step in the key distribution process is the preparation of states. Alice generates two random bit sequences of equal length: the first corresponds to the sent information bits and the second to the bases used to encode them into qubits. After the quantum states are transmitted, Bob generates a sequence of random measurement bases to measure the qubits. Each qubit is decoded based on the selected basis and the bit encoded by Alice. If for a particular qubit the bases applied for encoding and decoding coincide, Bob will measure the exact value Alice intended to send. In the opposite scenario, Bob’s detection will provide a random result with 50% probability.

For the next stage, the classical channel is used for a procedure called sifting. Alice and Bob announce the used measurement bases publicly, and every bit not measured with the same basis is discarded by both.[Citation23] The remaining part of the sequence constitutes the sifted key. For BB84, the sifted key will statistically have 50% the length of the original sequence (raw key).

In the subsequent stage (parameter estimation), Alice and Bob share additional bits to estimate the mismatches between their measurements. During this procedure, the length of the key is further diminished since shared bits are sacrificed and cannot be used for the formation of the final secret key. This means that a raw key of 100 photons, reducing to 50 bits after sifting. will further reduce to 25 bits if half of the key is shared for parameter estimation. The parameter used for error evaluation is the quantum bit error rate (QBER), defined as the number of erroneous bits on the sifted key over its length,

The accuracy of the QBER estimation increases by sharing a larger part of the key. However, given this requires discarding more bits, it eventually reduces the final secret key rate (SKR). Following parameter estimation, classical postprocessing error correction codes are implemented to eliminate the dissimilarities between the two sequences and obtain a single error-free key (reconciliation). In the privacy amplification stage, the two legitimate parties attempt to further minimize any information that might have been gained by an attacker. Finally, the SKR [EquationEq. (3)(3)

(3) ] expresses the total reduction of the key length and is a metric of the overall efficiency of the QKD scheme,

where Rsifted is the key rate obtained after sifting.

The final secret key length is affected by the presence and intensity of error sources in the communication. The higher the noise in the channel and the attack level, the more bits have to be shared to obtain an error-free key, eventually reducing the SKR. An optimally selected and well-characterized channel is necessary to minimize losses that would decrease performance. The theoretical secret key fraction for BB84 is

where h(1/2− qe) and h(QBER) are calculated using the Shannon binary entropy, while qe describes the attack error. Unless the channel is noiseless and there are no attacks, the actual SKR is always less than the theoretical SKR.[Citation24]

II.B. QKD Sources of Error

The two most common types of error introduced in a QKD communication scheme are channel noise due to depolarization and an intercept-resend attack.

The intercept-resend attack constitutes a fundamental eavesdropping scenario. As the name suggests, it describes the case when an attacker has access to the quantum channel and attempts to decode the transmitted qubits (all or a fraction of them) by choosing an arbitrary basis to measure the state of the photons. If the selected basis coincides with the one used to encode the qubit on the sender’s side, then the attacker accurately obtains the qubit data. In the opposite case, the decoding is random, as 0 or 1 can be obtained with equal probability.

Nevertheless, since the quantum state has collapsed, the eavesdropper prepares a new qubit as guided by the measurement outcome. The qubit is re-sent along the channel and received by Bob. At this point, Bob is unaware that the received qubit did not in fact originate from Alice. Fortunately, both parties should be able to detect the eavesdropper’s presence later in the parameter estimation stage. The attack level is modeled with the parameter ε, which corresponds to the percentage of pulses-photons that the eavesdropper chooses (or has the capability) to intercept and resend,

A value of ε = 1 indicates a full-scale attack, since every pulse sent over the quantum channel is intercepted. In this case, this would statistically translate to 1/4 of the sifted key being erroneous.[Citation24] In order to realize the presence and/or level of attack, the communication parties estimate the QBER. Since 1/4 of the key bits are expected to have errors, an ideal estimation should provide the theoretical value of QBER = 0.25.

Depolarization is a phenomenon that occurs in both free space (due to environmental conditions) and optical fiber (due to phase variations). In BB84, the probability of a bit in the sifted key being erroneous due to depolarization is equal to the channel disturbance, while the probability of being identical for both Alice and Bob is equal to the channel fidelity.[Citation25] Channel noise can be modeled using only the depolarizing parameter p. A depolarizing channel (described in Ref. [Citation26]) can be considered as a unitary operator Tp applied on a quantum state |ψ〉, transforming it as

where i are the Pauli matrices for i = x, y, z. The depolarizing parameter p directly contributes to the quantum bit error rate.[Citation26] In the case where no eavesdropper is present, QBER is found equal to

It is understood that the probability 1-p corresponds to the event that the original state |ψ〉 remains unaltered.[Citation27] Assuming the only error sources present are depolarization and an eavesdropper following the intercept-and-resend strategy, a straightforward formula was derived in Ref. [Citation24] to calculate the theoretical BB84 QBER rate as a function of the depolarization parameter p and attack rate ε,

The QBER is a quantitative evaluation of the communication security. Estimating high QBER values indicates that the channel is not reliable or the potential presence of an eavesdropper, and consequently, lower security. For this reason, the communication parties determine a threshold value in advance and abort the protocol when it is exceeded to preserve confidentiality. If QBER exceeds the threshold, the key generation process is generally aborted, as it is assumed an attacker is interfering with the communication channel. Typical values are approximately 3% to 5% due to device imperfections and transmission errors. Because QKD systems attribute all errors to an attacker, it is important to characterize the channel with respect to noise to prevent false positives and provide reliable system performance.

II.C. Brief Introduction to QKD Protocols

To this day, multiple QKD protocols have been proposed in the literature. Regardless of their dissimilarities, all protocols are aimed at the composition and distribution between communication participants of a provably unbreakable key. Additionally, they consist of two consecutive stages: (1) the quantum transmission stage, when quantum states are sent through the private channel and measured, and (2) the classical postprocessing stage where participants utilize the classical-public channel to convert the obtained bit strings to usable keys.[Citation23]

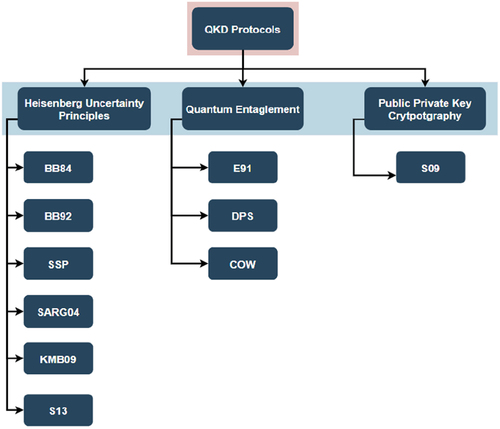

The two main categories are the “prepare and measure” and “entanglement-based” protocols. In the first case, quantum states are transmitted through a quantum channel after being prepared, and finally measured from the receiver. Protocols of this category (e.g., BB84, B92) are based on Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. In the second case, no transmission is involved, only a source of entangled photons. To generate a key, the communication parties obtain pairs of entangled states and measure the corresponding states.[Citation23] Protocols of this category (e.g., E91, BBM92) are based on quantum entanglement (QE). A classification of prominent protocols based on the physical principle on which they operate is provided in .

In this work, we focus on Discrete-Variable (DV-QKD) and prepare and measure since they have been extensively investigated in the literature and provide robust performance. Even though BB84 is the most covered protocol due to its simplicity and performance, B92 is also a prominent prepare-and-measure protocol. Introduced by Charles Bennett, it proved that any two nonorthogonal quantum states are sufficient for establishing a QKD communication scheme.[Citation28] B92 is simpler than BB84 in the sense that it only uses two qubit states from the two measurement bases used in BB84. On the other hand, the six-state protocol (SSP99) modifies the BB84 protocol by adding a third measurement basis, leading to defining a total of six possible states. As expected, a shorter fraction of the key is preserved during the sifting stage, leading to a shorter sifted key (1/3 versus 1/2 of the raw key).

The SARG04 protocol was designed in 2004 to address photon number splitting (PNS) attacks. It is identical to BB84 except for the sifting process and is capable of being applied on the same equipment.[Citation29] Even though the same states are used as in BB84, sifting differs in the sense that Alice does not reveal the polarization basis used to encode each qubit. Therefore, it becomes impossible for the eavesdropper to obtain the bit information without storing additional photons and increasing the risk of being detected. As a tradeoff for the additionally featured security, SARG04 generates a shorter sifted key than BB84 (1/4 versus 1/2 of the raw key), which decreases the key production rate.[Citation23] It has also been proven that for nonnegligible channel depolarization, BB84 will perform better than SARG04.[Citation26] On the other hand, given the protocol’s resistance toward PNS attacks, it exhibits higher efficiency than BB84 for longer distances.[Citation29] presents a summary of the states used and the expected key decrease through the sifting stage for the four prominent protocols.

TABLE II Comparison of Prominent Discrete Variable Prepare-and-Measure Protocols

The first QE-based protocol (E91) was proposed in 1991 by Ekert.[Citation30] BBM92[Citation31] was introduced 1 year later as a QE-based protocol equivalent to BB84. The difference lies in the fact that a pair of entangled photon particles is used to declare the states. BBM92 is preferred against the advanced B92 and E91.[Citation20] More recently, innovative QKD protocols have been proposed. KMB09 introduced a new approach on eavesdropping detection through the error rate. S09, ZV11, and AK15 eliminated the requirement of a classical channel. S09 is further considered very efficient for short-distance key distribution, while AK15 is tolerant to noise disturbances. IB20 is the latest QKD protocol. Introduced in 2020, it proposed a combinatory implementation of DV-QKD and CV-QKD, while being the most reliable for long distances.[Citation21]

The QKD protocol simulation is important to researchers, as it allows for obtaining an insight before proceeding to complicated experiments involving advanced and costly hardware. Several simulators are available, a comprehensive survey of which is available in Ref. [Citation32]. In this work, we leverage the newly developed NuQKD simulation framework, which is briefly presented in Sec. III. NuQKD combines a variety of features not available in another standalone simulator, and has been benchmarked against analytical, numerical, and experimental data.[Citation17]

III. NuQKD

To evaluate the feasibility of a QKD implementation for nuclear reactor communications, a customizable simulator was developed, called NuQKD. NuQKD[Citation17] is a Python-based code with a modular structure, allowing for the customization of multiple low-level simulation parameters. The core code is supplemented by optional, user-controlled modules that provide flexibility simulating equipment and channel imperfections.

NuQKD enables BB84 simulation by establishing communication between two computer terminals. For the purposes of the nuclear environment performance analysis, the terminals represent communication between the advanced reactor facility, located potentially in a remote location, and an operations center intended to monitor and semi-autonomously operate the reactor.

The code comes with numerous capabilities. It allows for the simulation of nonideal channels (both optical fiber and free space), while accounting for imperfect equipment (weak attenuated pulses, imperfect detection, dead time, dark count rate, etc.). The bit strings required for quantum channel simulation are fetched in real-time from true random number generators to ensure maximum simulation fidelity. Simulations produce various performance metrics useful for the evaluation of the scheme (sifted key length, QBER estimation, elapsed communication time, and more). An overview of the inputs and outputs of the simulation is shown in .

Fig. 6. Overview of the NuQKD input and output parameters (after Ref. [Citation17]).

![Fig. 6. Overview of the NuQKD input and output parameters (after Ref. [Citation17]).](/cms/asset/8c1d222d-24c1-4471-9c13-c62631339709/unct_a_2368977_f0006_b.gif)

The three starting parameters for the communication parties are the number of iterations, raw key size, and sharing rate. The raw key size determines the number of photons to be exchanged for each key distribution. The number of iterations corresponds to the user-defined number of key distributions for a given key size. The accuracy of the statistics improves for increased iterations. The sharing ratio f refers to the classical processing part of the algorithm and determines the fraction of the sifted key shared between the parties for error estimation. It is given as

Having a higher sharing ratio leads to a more precise QBER estimation at the cost of sacrificing a larger part of the key. As a consequence, the usable-key generation rate is decreased. NuQKD employs a large number of additional customizable parameters and modules, which are presented in detail in Ref. [Citation17].

Finally, ΝuQKD has been extensively benchmarked against theoretical, numerical, and experimental data and has been shown to produce results in close agreement with real-world QKD experiments.[Citation17] It has been shown to efficiently simulate both optical fiber and free space applications and to enable the accurate modeling of source, channel, and detector imperfections.

IV. RELATED WORK AND NOVELTY

The novelty of this work lies in the fact that quantum communications for nuclear power reactors are a particularly underexplored field, with very limited research presented in the literature. Pantopoulou et al. presented a preliminary concept study for small modular reactor (SMR) remote monitoring using AES-256 encryption with the BB84 protocol.[Citation33] The SeQUeNCe quantum network simulator[Citation34] was used to evaluate key distribution over a 10-km lossy depolarizing channel paired with the Cascade error correction protocol, with respect to the elapsed time for key distribution, encryption, and decryption processes. Roberts and Heifetz investigated wireless QKD applications for SMRs by conducting an environmental simulation analysis with SeQUeNCe that involved a ground-satellite quantum channel based on microwave transmission.[Citation35] The average protocol times were evaluated for a combination of weather conditions using an atmospheric attenuation model specifying clear weather, cloud/fog, and rain scenarios.

The present work differentiates in the sense that it specifically identifies data transmission requirements for several use cases of advanced reactor networking by studying the entirety of data generated from a real-world, fully digital reactor I&C system. Based on the estimated target rates and leveraging the newly developed NuQKD simulator,[Citation17] we evaluated QKD performance using a variety of equipment specifications and compared the results against the customized requirements of a smart grid–compatible reactor. As a result, we present a numerical study tailored to the functionalities of advanced reactors (remote monitoring, semi-autonomous operation), and confirm the potential of QKD for securing information.

As important limitations of quantum cryptography in the 5G network era stem from restrictions in available quantum hardware, this work demonstrates that QKD is, in principle, compatible with nuclear power installations. Contrary to most consumer applications, nuclear power plants (NPPs) employ more well-defined communication links (static system segments[Citation36]). For example, the QKD inherent limitation of point-to-point communications is not an issue here, since a NPP needs to be securely connected with several explicitly specified systems instead of an arbitrary, varying number of users around the globe. Dark fiber availability is also common at the level of power generation in smart grid applications.[Citation37]

Finally, the obtained results constitute conservative estimations, since typical equipment parameters are used as simulation inputs. A 75% sifted key reduction is considered instead of employing any particular reconciliation protocol of higher efficiency (e.g., optimized Cascade), therefore obtaining a lower limit for key generation rates. As a result, the performance of the presented communication architecture can only improve compared to the reported values, as quantum technology advances and readily available classical algorithms are incorporated.

V. PERFORMANCE EVALUATION

To evaluate the performance of a potential QKD implementation on reactor communications, a reference scenario with various communication links and data traffic was developed. Actual process data from the fully digital PUR-1 reactor were studied to determine the bandwidth requirements of the system links. NuQKD was then used to simulate the performance of QKD for each of the communication links.

V.A. Reference Scenario

The reference scenario was developed to reflect the communication and networking features of modern reactor designs. A prevalent example of such designs are microreactors, offering multiple advantages such as small size, simple plant layout, and fast onsite installation. At this moment, there exist several different microreactors at an advanced design stage.[Citation38] Given they are intended for installation in remote areas and unattended operation, the I&C systems may also need to function remotely.[Citation22]

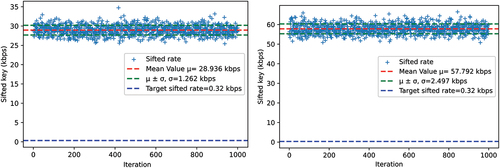

The connections in the reference scenario have been simplified to make it suitable for not only advanced but also conventional NPPs connected to the smart grid. These modern nuclear system architectures follow a distributed approach by having a single control room monitoring multiple reactors. An example of such design is the licensed light water SMR design proposed by NuScale, which specifies a control room capable of monitoring and controlling 12 modules.[Citation39] The reference scenario is schematically presented in .

Fig. 7. Reference reactor scenario. The green area marks the reactor site. Diodes 1 and 3 are two-way, external links connecting the reactor to the RTU and consumer network, respectively. Diode 2 is an internal link for the one-way transmission of all reactor signals to the data storage station. Diodes 1, 2, and 3 handle 67, 2000, and 10 signals, respectively.

Three communication links were defined:

Diode 1, an external link, connects the reactor main facility to a remote workstation [remote terminal unit (RTU)], considering a distance up to 100 km. This connection handles data sufficient for the real-time remote control of the reactor. This connection is bidirectional since data are transmitted to the workstation, while control commands are also received from it. It is assumed that an intermediate node might be required, acting as a repeater.

Diode 2, a one-way, internal communication link with a distance of up to 1 km, leads to the data storage station, where all sensor data are transmitted and stored in real time.

Finally, diode 3 is an external communication link to the consumer network (energy grid). Through this connection, data such as power supply and demand of electricity and/or steam water are exchanged.

Each of the diodes has different bandwidth requirements, based on the signals that need to be transmitted.

V.B. Signal Bandwidth and Data Encoding

Operating data are associated with various quantities and multiple origins. In general, they can be classified into one of six categories:

process data (operational data, physical measurements)

communication data (network traffic, packets, etc.)

configuration data (network, host and device configuration settings)

host data (resource usage, etc.)

monitoring data (system logs, alerts, and indications)

metadata (other system-related data).

A digital I&C typically processes around 2000 signals. These values are represented as vector columns. However, data types are naturally multimodal. Some time series consist of continuous float numbers (e.g., count rate from fission chamber), while others contain binary signals that can be represented with a single bit value (e.g., manual SCRAM, ACK button).

Sensor signals are sampled and recorded typically with sampling frequencies on the order of a few cycles per second. This allows the raw signals to be properly filtered in order to avoid delivering distorted information to the operator. For our reference scenario, we have chosen a sampling frequency equal to fs = 1 Hz, a value typically used in commercial, off-the-shelf Programmable Logic Controllers (PLC). The floating-point number variables are reported in the human-machine interface with a precision of a few digits. In this work, we chose a precision of six decimal digits, as it was found to be adequate for reporting even the most sensitive magnitude variations (e.g., small reactivity insertions). These characteristics need to be considered when signals are encoded to be transmitted.

For the purposes of this work, 67 signals out of the 2000 total were selected. These constitute the core signals, sufficient to fully monitor and control reactor operation. These signals are transmitted via diode 1 of the reference scenario, connecting the reactor site with the RTU. Through diode 2, all 2000 signals need to be transmitted. Finally, diode 3 would only be used for transmitting specific signals (e.g., output power, operational status, etc.). For the scope of the reference scenario, 10 signals would be a fair estimation.

The simplest implementation of encoding decimal data into binary is the binary-coded decimal code (BCD). BCD makes use of four binary digits to encode each decimal floating point. Even though more bit-efficient encoding schemes have been developed (e.g., Chen-Ho encoding, densely packed decimal encoding), BCD can provide a first-order estimation of the maximum number of bits required before further optimization, thus constituting an upper limit.

It is important to consider the different data types to estimate the total bandwidth requirements. For this reason, upper and lower values of different types of reactor signals are presented. The binary size of each variable is determined by three factors: data type, required precision, and signal priority.

For a primary estimation, we relied only on the data type and ignored the required precision and priority. In this case, all signals were treated as equally important, and a standard value of precision digits was selected for all floating numbers regardless of the physical significance. Six decimal digits were used to report the floating-point variables to obtain the worst-case scenario for bandwidth requirements. This estimation should lead to the determination of an upper limit.

By examining the data range, it was observed that out of the 67 signals, 40 were floats, 12 were binary, and 15 were integers. By examining the signal values on a time window of 24 h, including both steady-state and transient operation conditions, we observed that out of the 40 float value signals, 22 were constantly found in the range from −4 to 4. Therefore, their integer part can be represented by two bits.

From the remaining 18, four were found in the range from −16 to 16 (integer part represented by four bits), six between −32 and 32 (integer part represented by five bits), four between −64 and 64 (integer part represented by six bits), and 3 more between −128 and 128 (integer part represented by seven bits).

One particular channel, recording the counts per second (cps) as detected from the fission chamber, exhibited the widest range, with a minimum value at 3.0223 cps, a maximum of 40 120 000 counts. To represent the range of the integer part accurately, 26 binary digits needed to be allocated.

From the analysis of the previously described signals, it was estimated that a maximum of 533 bits would be required to encode the entirety of the 67 reactor signals in a second. The detailed calculations are demonstrated in . This mean that a QKD system capable of delivering at least a SKR of 533 bps for a given transmission distance and operating parameters would be suitable for delivering the entire core data from a digital I&C to a remote terminal.

TABLE III Bandwidth Requirements for 67 Reactor Signals

It should be noted, however, that this calculation did not include the bandwidth that should be allocated to enable two-way communications. In other words, bandwidth needs to be reserved for command transmission and other operational data that would enable full remote operation. Furthermore, this approach is valid by assuming that 1 Hz is a reasonable sampling frequency for the reactor signals.

To calculate the bandwidth required for transmitting the entirety of signals to the data storage station (diode 2), we assumes that the different signal data types appeared as frequently as we encountered them in the selected set of 67 signals. In this sense, the overall bandwidth required for diode 2 could be estimated as approximately 30 times larger than the bandwidth of the core signals, or .

Following the same procedure for diode 3, we estimated the required bandwidth to be allocated for 10 signals would be . A summary of the reference scenario signal bandwidth requirements is displayed in .

TABLE IV Link Specifications and Requirements

V.C. Evaluation of Key Rates as a Function of Distance

NuQKD was used to evaluate the link diodes specified in the reference scenario. The first step was to select the equipment parameters. The equipment specifications with respect to the NuQKD input parameters are displayed in .

TABLE V Input Parameters for Reference Scenario Evaluation*

It was assumed there was no further optical attenuation due to the detector. We further selected a dead time of τ = 50 ns and a typical detector efficiency of ηD = 0.5. Regarding the weak pulse source, the simulation was carried with repetition frequencies of 1 MHz and 2 MHz, as these specifications can be met by standard equipment. The mean photon number was selected to be μ = 0.189. This was chosen as a tradeoff value as it contributes to minimizing multiphoton pulses without significantly decelerating the key generation process.

Since the reference scenario involves distances on the order of tenths of kilometers, the main priority regarding the quantum channel specifications was to minimize the attenuation per unit length. As of yet, it has been shown that the minimum attenuation was exhibited in a single mode fiber operating at a wavelength of 1550 nm, and was equal to 0.2 dB/km. To also consider the channel error sources, it was further assumed that the depolarization level is p = 5%. For the moment, eavesdropping is not taken into account (as it does not affect the rate of sifted key formation).

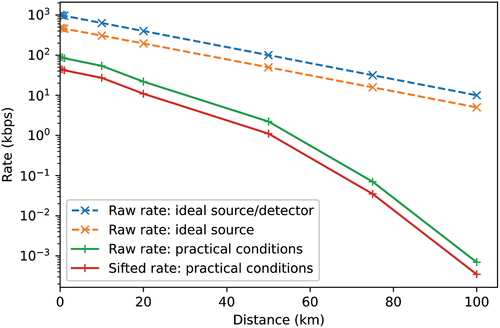

We first executed a simulation with the previous parameters while varying the transmission distance. The distance range was from 0.1 up to 100 km, the maximum link defined in the reference scenario. To understand the effect of the weak coherent source on the key generation rate, an ideal source was first considered and then replaced by a Poissonian source with μ = 0.189. Both sources operate at a frequency frep = 1 MHz. The attenuating channel of α = 0.2 dB/km was present in both cases.

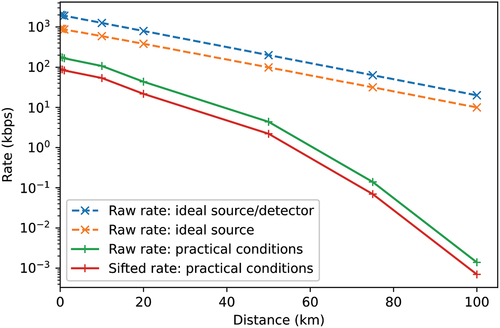

It was shown that the nonideal source had a crucial effect on the key formation rate. While a potential ideal source forms the raw key with a rate approaching 1 Mbps for l = 100 m (0.1 km), the weak coherent source provided at best around 90 kbps. The difference becomes more important as the distance increases. For l = 50 km, the rate with the ideal source was approximately 100 kbps, while for the weak coherent source it dropped to just 3.5 kbps. Therefore, it was concluded that the inexistence of an ideal source significantly deteriorates QKD performance.

For the next step, we explored the relation between the raw key and sifted key rates generated with the weak coherent source as a function of distance. The different raw key rates and the sifted key rate obtained in practical conditions are displayed in . It is shown that both the raw and sifted key rates decline exponentially along with an increase in the transmission distance. Additionally, the sifted key rate is, on average, half the raw key rate, as would be expected.

Fig. 8. Raw key rate and sifted key rate as a function of distance for weak attenuated pulse source (frep = 1 MHz and μ = 0.189) and imperfect detector (ηD = 0.5 and τ = 50 ns). Channel is an attenuating Single-Mode optical Fiber (a = 0.2 dB/km). The raw key rate of an ideal single-photon source operating at the same frequency coupled with a perfect detector on the attenuating channel is displayed with the blue dashed line. Keeping the ideal source and switching to the practical detector, the orange dashed line occurs.

The same procedure was repeated after doubling the repetition frequency of the ideal and weak coherent sources, now operating at 2 MHz. The corresponding curves are featured in . While the ideal source forms the raw key with a rate approaching 2 Mbps for l = 100 m, the weak coherent source provides at best around 180 kbps. The same trend holds true for all transmission distances. As expected, the raw key rate appears to be linear with respect to the source frequency.

Fig. 9. Raw key rate and sifted key rate as a function of distance for weak attenuated pulse source (frep = 2 MHz and μ = 0.189) and imperfect detector (ηD = 0.5 and τ = 50 ns). Channel is an attenuating Single-Mode optical Fiber (a = 0.2 dB/km). The raw key rate of an ideal single-photon source operating at the same frequency coupled with a perfect detector on the attenuating channel is displayed with the blue dashed line. Keeping the ideal source and switching to the practical detector, the orange dashed line occurs.

summarizes the corresponding rates obtained with the weak coherent sources for discrete distance values. For 1 MHz, the sifted key rate dropped to values less than 50 bps approximately after 75 km. At 100 km, the sifted key was less than 1 bps, a value that cannot be of any practical use.

TABLE VI Raw Key Rate and Sifted Key Rate for Varying Distances*

V.D. Eavesdropping Detection Performance

The discrete distance cases of interest were further explored in terms of the error rate by introducing a selective attacker in addition to the depolarizing channel. The eavesdropper was present on half of the total iterations, intercepting all of the transmitted pulses of each key distribution iteration (ε = 1). A bit sequence of 1 and 0 was formed and stored, corresponding to whether the particular iteration was attacked or not, respectively. For this simulation, we used the raw key rate obtained in the previous analysis as the input photon number of each iteration. This practically means that key distillation and classical processing takes place every second. The sharing ratio was initially chosen as f = 1/100.

The detection of an eavesdropper, and therefore the decision of the parties to abort communication or not, were solely based on the QBER estimation. If the estimation exceeded the predetermined threshold, the protocol was restarted, as it was assumed that the communication was intercepted. Given a particular threshold, the communication parties would have to decide whether to abort (QBER > threshold) or to continue (QBER < threshold). In practice, the error cannot be explicitly attributed to depolarization or eavesdropping; thus, it might be possible to erroneously detect an eavesdropper and mistakenly abort communication. In the data analysis stage, four cases could be defined for each iteration based on the attack bit sequence and the selected threshold:

True Positive (TP): QBER value exceeds the threshold and attack is equal to 1.

False Negative (FN): QBER value is lower than the threshold, but attack is equal to 1.

True Negative (TN): QBER value is lower than the threshold and attack is equal to 0.

False Positive (FP): QBER value is higher than the threshold, but attack is equal to 0.

By counting the occurrences of each of these events for a given number of iterations, the confusion matrix can be constructed, as shown in .

TABLE VII Confusion Matrix for a Certain Threshold Value

The true positive rate (TPR) (sensitivity) is given by EquationEq. (10)(10)

(10) and the false positive rate (FPR) (specificity) by EquationEq. (11)

(11)

(11) ,

The ideal eavesdropping detection implies that . Since this might not be possible in practice, and in order to prioritize security, it is important to ensure that no actual attacks are left undetected (

, while minimizing FPs. Therefore, the objective is to model the efficiency of decision making for the different thresholds.

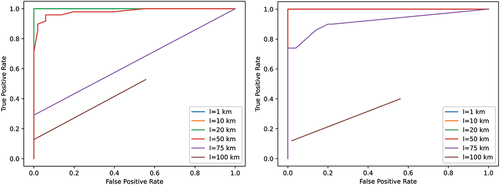

The detection threshold was varied to obtain the overall performance of each link with respect to detecting an eavesdropper. For each threshold, the sensitivity and specificity were recorded. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is an intuitive way to visualize detection efficiency as the threshold is varied, and is constructed by plotting TPR versus FPR. Apart from the number of photons, the ROC is also affected by the accuracy of the error estimation, and is thus dependent on the sharing ratio as well. For the scope of this application, it can be stated in an abstract formulation that

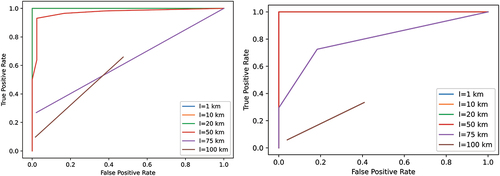

The ROC curve for the distances of interest is shown in the left image in . We observed that lengths of 1 km, 10 km, and 20 km provided ideal detection of an attacker in the 5% depolarizing channel. For l = 50 km, a deviation from the ideal case was recorded, even though the performance was still sufficient. However, starting from l = 75 km, the detection performance deteriorated significantly to a point where it was not considered reliable. This trend was attributed to the fact that the obtained raw and sifted keys, in agreement with , were too small to provide an accurate estimation. For keys of this size, a sharing ratio of 1/100 cannot function at all.

Fig. 10. ROC for transmission distances of interest (frep = 1 MHz, p = 5%, ηD = 0.5, τ = 50 ns, and μ = 0.189): (left) f = 1/100 and (right) f = 1/10.

When choosing to share one bit out of every 10 (f = 1/10), the performance improved significantly, as shown in the right image in . Ideal detection was offered for distances up to 50 km, while the performance at 75 km also improved. This highlights the importance of adjusting the sharing ratio according to the order of magnitude of the sifted key and taking into account the transmission distance of the particular link. A similar trend was noticed when the simulation was executed for the 2-MHz source, as shown in .

V.E. Key Generation Performance on Reference Scenario Communication Links

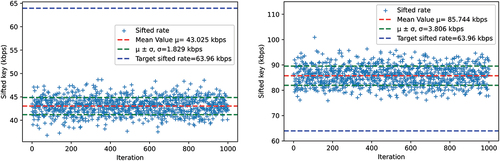

Following the sifted key formation rates for the three reference scenarios, links were evaluated through individual NuQKD simulations with 1000 iterations each.

V.E.1. Link 1: l = 100 km

The first diode is intended to connect the reactor site to the RTU, establishing a two-way communication. The distance was assumed to be 100 km; therefore, it is important that the channel introduce the least possible attenuation per unit length. This value is known to be found in an optical fiber operating at a wavelength λ = 1550 nm and is equal to α = 0.2 dB/km. Therefore, an optical fiber quantum channel was explored for this link.

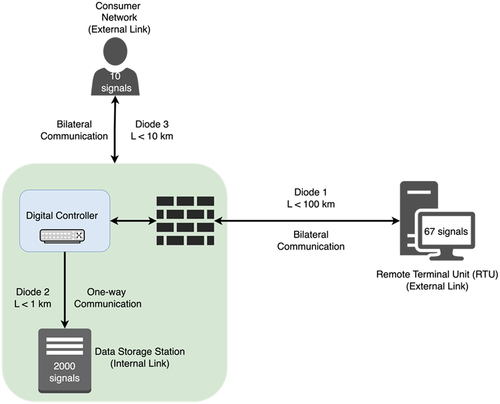

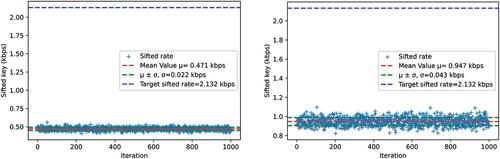

This diode aims to transmit in real time the reactor signals essential for obtaining a sufficient overview of the operating conditions. Further, the operation and emergency commands should be transmitted from the RTU to the reactor site at all times in order to ensure the remote control is safe. The NuQKD simulation yielded a sifted key of 471 bps on average for a source frequency of 1 MHz. For 2 MHz, the sifted key rate was 947 bps. displays the sifted rates obtained for 1000 iterations.

Fig. 12. Sifted key rates for Link 1 (l = 100 km and a = 0.2 dB/km): (left) 1 MHz and (right) 2 MHz.

When compared with the required transmission rate, the sifted key rate was not sufficient for either of the source frequencies. Sifted key rates of 471 bps and 947 bps cannot lead to a SKR of 1 kbps or greater after parameter estimation, privacy amplification, and error correction processes have taken place. This setback was understood, given that 100 km is a large, arbitrary distance.

However, the result did not mean the QKD implementation in the specific link was impossible, instead there existed several options to consider. Obtaining a weak pulse laser source with a higher repetition frequency should be able to compensate for the distance loss and achieve the desired bandwidth. An alternative option would be to consider protocol variations that allow for higher source intensities (e.g., Decoy-State BB84) to achieve higher key rates. As a more practical approach that is not based on acquiring higher-end equipment, data prioritization could be a viable solution.

Many of the signals generated from the reactor might not be fundamental for remote control, or it might not be necessary to deliver them in such a high sampling rate. For example, there are quantities that vary in a much larger timescale than seconds, in which case 1 Hz is considerably more than required. Nevertheless, exploring different methods for compressing the reactor data in a way that can still be transmitted with standard QKD equipment is most certainly on the intended expansion of the current work.

V.E.2. Link 2: l = 1 km

The second diode connects the reactor site to the data storage station, which is located in the proximity. The total amount of reactor-generated data, including physical variables and OT and IT signals should be transmitted in real time to be stored and should provide a full history record when needed. Thus, all the ≈2000 reactor-processed signals need to be included in the calculations. It was estimated in the reference scenario that the target SKR was approximately 16 kbps.

The distance is considerably less than the length of the RTU link, and was taken at 1 km. It is expected that this diode will transmit the reactor signals in their entirety and with the original sampling rate. The 1550-nm, single mode fiber was recruited for this diode as well.

The NuQKD simulation yielded a sifted key rate of 43 kbps on average for a source frequency of 1 MHz. For 2 MHz, the sifted key rate was 86 kbps. displays the sifted rates obtained for 1000 iterations. The sifted key rate was more than sufficient to fulfill all requirements posed for the 2-MHz source.

Even in the extreme scenario that through the stages of error estimation, error correction, and privacy amplification, 75% of the sifted key was sacrificed (a conservative lower limit), the remaining SKR would still be .

The available key was much greater than the required 16 kbps. This confirms the capability of directly implementing QKD for this particular link, even with equipment components of inferior specifications. It was also evident that the communication scheme should be sufficiently tolerant of future deterioration of the channel due to environmental conditions or wear.

V.E.3. Link 3: l = 10 km

The third link connects the reactor to the consumer network. The intention was to establish a two-way information exchange scheme, where the electricity or heat demand/production status was transmitted from and toward the reactor. As a result, no data related to reactor operation and maintenance need to be shared over this link. This is advantageous since only a small fraction of the reactor-generated data needs to be exchanged, therefore requiring a dedicated bandwidth less than 533 bits.

We estimated that 80 bps would be a sufficient rate for the signals associated with this use case. Using the same parameters as in the other links, an average sifted key rate of almost 29 kbps was produced for the 1-MHz source and 58 kbps for the 2-MHz source. displays the simulation results over 1000 iterations.

The obtained sifted rate was again significantly above the requirements, regardless of the source used. It is reminded that this particular link is not expected to transmit the entirety of the reactor-generated data in real time, as operation and maintenance signals are not required from the consumer network. Given that the confidentiality level of the remaining data is not high enough, it may not justify a dedicated QKD link with OTP encryption. Nevertheless, it was shown that it is technically feasible. The SKR, assuming 75% of the sifted key was sacrificed during postprocessing would be approximately 7.23 kbps for the 1-MHz source and 14.4 kbps for the 2-MHz source.

VI. CONCLUSION

The feasibility of addressing the confidentiality requirements of nuclear reactor communications with QKD was explored in this work. A review of the modern trends in I&C systems attributed to the advent of advanced digital reactor designs, along with the historical approach of cyberattacks against nuclear facilities, led to highlighting the vulnerabilities and necessities of nuclear communications today. It was pointed out that the normal operation of a nuclear facility demands immediate and robust information transmissions.

A reference scenario inspired by smart grid–compatible reactors was designed. NuQKD, a novel simulation tool allowing for low-level parameter customization, was recruited to evaluate the performance of a practical QKD application with respect to the reference reactor’s external connections. The study designated the main potential difficulty in an actual nuclear environment as the achievement of a sufficient key rate for larger transmission distances approaching 100 km. Several suggestions were proposed for the elimination of such an obstacle by optimally choosing hardware specifications and by applying preprocessing techniques for data prioritization and compression. Shorter transmission distances appeared to be already suitable for installing a QKD link, using typical equipment specifications and without any preprocessing even required.

Furthermore, the eavesdropping simulations indicated that our QKD system is capable of perfectly detecting an intercept-and-resend attack in a depolarizing channel for up to a 50-km distance. To achieve this performance, only 10% of the sifted key was sacrificed for parameter estimation; therefore, the secret key generation rate was not significantly deteriorated.

The obtained results were overall interpreted as promising and justifying proceeding to further experimentation through the installation of a real-world QKD system at a reactor site. Regarding future work, we intend to continue the analysis of reactor signals. Applying prioritization and more advanced data compression should further reduce the required bandwidth and therefore the target SKRs. Furthermore, we are considering closely modeling the environmental parameters affecting free space and optical fiber transmissions and conducting an in-depth noise analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sacit Cetiner at Idaho National Laboratory, Phil Evans at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and Joseph Lukens at Arizona State University for fruitful discussions and expert input. Konstantinos Gkouliaras would like to acknowledge the Greek Atomic Energy Commission for supporting his doctoral studies through a graduate fellowship.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- C. GIDNEY and M. EKERÅ, “How to Factor 2048 Bit RSA Integers in 8 Hours Using 20 Million Noisy Qubits,” Quantum, 5, 433 (Apr. 2021); https://doi.org/10.22331/q-2021-04-15-433.

- H.-K. LO, M. CURTY, and K. TAMAKI, “Secure Quantum Key Distribution,” Nat. Photon, 8, 8, 595 (Aug. 2014); https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2014.149.

- Y. CAO et al., “The Evolution of Quantum Key Distribution Networks: On the Road to the Qinternet,” IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials, 24, 2, 839 (2022); https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2022.3144219.

- K. GKOULIARAS and S. CHATZIDAKIS, “Evaluation of a QKD Network Structure Suitable for Secure Communications for Advanced Nuclear Reactors,” Trans. Am. Nucl. Soc., 126, 188 (2022).

- D. PLIATSIOS et al., “A Survey on SCADA Systems: Secure Protocols, Incidents, Threats and Tactics,” IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials, 22, 3, 1942 (2020); https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2020.2987688.

- “Regulatory Guide 5.71, Cyber Security Programs for Nuclear Facilities,” Nuclear Regulatory Commission (2010).

- “M-Trends 2022 Special Report,” Mandiant (2022); https://mandiant.widen.net/s/bjhnhps2mt/m-trends-2022-report (accessed June 4, 2023).

- W. TOUNSI and H. RAIS, “A Survey on Technical Threat Intelligence in the Age of Sophisticated Cyber Attacks,” Comput. Secur., 72, 212 (Jan. 2018); https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2017.09.001.

- B. MILLER and D. ROWE, “A Survey SCADA of and Critical Infrastructure Incidents,” Proc. 1st Annual Conf. on Research in Information Technology (RIIT’12), p. 51, ACM Press (2012); https://doi.org/10.1145/2380790.2380805.

- C. PORESKY et al., “Cyber Security in Nuclear Power Plants: Insights for Advanced Nuclear Technologies,” 6711 (Sep. 2017); https://doi.org/10.13140/rg.2.2.34430.69449.

- S. KIM et al., “Cyber Attack Taxonomy for Digital Environment in Nuclear Power Plants,” Nucl. Eng. Technol., 52, 5, 995 (May 2020); https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2019.11.001.

- R. LANGNER, “Stuxnet: Dissecting a Cyberwarfare Weapon,” IEEE Secur. Privacy Mag.” 9, 3, 49 (May 2011); https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2011.67.

- F. ZHANG, J. W. HINES, and J. B. COBLE, “A Robust Cybersecurity Solution Platform Architecture for Digital Instrumentation and Control Systems in Nuclear Power Facilities,” Nucl. Technol., 206, 7, 939 (July 2020); https://doi.org/10.1080/00295450.2019.1666599.

- “Indictment Related to Wolf Creek Computer Hack Unsealed,” NuclearNewswire (Apr. 4, 2022); https://www.ans.org/news/article-3818/indictment-related-to-wolf-creek-computer-hack-unsealed/ (accessed May 13, 2023).

- D. DAS, “An Indian Nuclear Power Plant Suffered a Cyberattack. Here’s What You Need to Know,” Washington Post (Nov. 4, 2019); https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/11/04/an-indian-nuclear-power-plant-suffered-cyberattack-heres-what-you-need-know/ (accessed May 13, 2023).

- S. D. ANTÓN et al., “Two Decades of SCADA Exploitation: A Brief History,” Proc. 2017 IEEE Conf. on Application, Information, and Network Security, pp. 98–104 (2017); https://doi.org/10.1109/AINS.2017.8270432.

- K. GKOULIARAS et al., “NuQKD: A Modular Quantum Key Distribution Simulation Framework for Engineering Applications,” Adv. Phys. Res., 2400016 (Mar. 2024); https://doi.org/10.1002/apxr.202400016.

- C. H. BENNETT and G. BRASSARD, “Quantum Cryptography: Public Key Distribution and Coin Tossing,” Theor. Comp. Sci., 560, 7 (Dec. 2014); https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcs.2014.05.025.

- M. PITTALUGA et al., “600-km Repeater-Like Quantum Communications with Dual-Band Stabilization,” Nat. Photon., 15, 7, 530 (July 2021); https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-021-00811-0.

- A. I. NURHADI and N. R. SYAMBAS, “Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) Protocols: A Survey,” Proc. 2018 4th Int. Conf. on Wireless and Telematics (ICWT), p. 1, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (July 2018); https://doi.org/10.1109/ICWT.2018.8527822.

- R. NANDAL et al., “A Survey and Comparison of Some of the Most Prominent QKD Protocols,” Proc. ICICNIS 2020 (2021); https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3769123.

- S. CHATZIDAKIS, “Exploring Quantum Key Distribution For Nuclear I&C Cybersecurity,” presented at the 12th Nuclear Plant Instrumentation, Control and Human-Machine Interface Technologies (NPIC&HMIT 2021), p. 10 (2021).

- R. WOLF, “Quantum Key Distribution: An Introduction with Exercises,” Lecture Notes in Physics, Vol. 988, Springer International Publishing (2021); https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73991-1.

- M. S. ABDELGAWAD, B. A. SHENOUDA, and S. O. ABDULLATIF, “EnQuad: A Publicly-Available Simulator for Quantum Key Distribution Protocols,” Cybern. Inf. Technol., 20, 1, 21 (Mar. 2020); https://doi.org/10.2478/cait-2020-0002.

- Y.-C. JEONG, Y.-S. KIM, and Y.-H. KIM, “Effects of Depolarizing Quantum Channels on BB84 and SARG04 Quantum Cryptography Protocols,” Laser Phys., 21, 8, 1438 (Aug. 2011); https://doi.org/10.1134/S1054660X11150126.

- M. DEHMANI, H. EZ-ZAHRAOUY, and A. BENYOUSSEF, “Quantum Key Distribution with Several Cloning Attacks via a Depolarizing Channel,” J. Russ. Laser Res., 36, 3, 228 (May 2015); https://doi.org/10.1007/s10946-015-9495-y.

- I. SLIMEN et al., “Stop Conditions of BB84 Protocol via a Depolarizing Channel (Quantum Cryptography),” J. Comp. Sci., 3, 6, 424 (June 2007); https://doi.org/10.3844/jcssp.2007.424.429.

- C. H. BENNETT, “Quantum Cryptography Using Any Two Nonorthogonal States,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 68, 21, 3121 (May 1992); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.3121.

- D. STUCKI et al., “Long-Term Performance of the SwissQuantum Quantum Key Distribution Network in a Field Environment,” New J. Phys., 13, 12, 123001 (Dec. 2011); https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/13/12/123001.

- A. K. EKERT, “Quantum Cryptography Based on Bell’s Theorem,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 67, 6, 661 (Aug. 1991); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.67.661.

- C. H. BENNETT, G. BRASSARD, and N. D. MERMIN, “Quantum Cryptography Without Bell’s Theorem,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 68, 5, 557 (Feb. 1992); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.557.

- A. AJI, K. JAIN, and P. KRISHNAN, “A Survey of Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) Network Simulation Platforms,” Proc. 2021 2nd Global Conf. for Advancement in Technology (GCAT), pp. 1–8, Bangalore, India, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (Oct. 2021); https://doi.org/10.1109/GCAT52182.2021.9587708.

- M. PANTOPOULOU et al., “Monitoring and Secure Communications for Small Modular Reactors,” Dynamic Data Driven Applications Systems, E. BLASCH, F. DAREMA, and A. AVED, Eds., pp. 144–151, Springer Nature Switzerland (2024); https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-52670-1_14.

- X. WU et al., “SeQUeNCe: A Customizable Discrete-Event Simulator of Quantum Networks,” Quantum Sci. Technol., 6, 4, 045027 (Sep. 2021); https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-9565/ac22f6.

- M. ROBERTS and A. HEIFETZ, “Investigating Wireless Quantum Key Distribution for Advanced Reactor Communications,” ANL/NSE-21/49, Argonne National Laboratory ( Aug. 2021); https://doi.org/10.2172/1837006.

- M. MEHIC et al., “Quantum Cryptography in 5G Networks: A Comprehensive Overview,” IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials, 26, 1, 302 (2024); https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2023.3309051.

- T. KURUGANTI et al., “Quantum Key Distribution Applicability to Smart Grid Cybersecurity Systems,” Oak Ridge National Laboratory (2014).

- R. TESTONI, A. BERSANO, and S. SEGANTIN, “Review of Nuclear Microreactors: Status, Potentialities and Challenges,” Prog. Nucl. Energy, 138, 103822 (Aug. 2021); https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2021.103822.

- K. LAFERRIERE, J. STEVENS, and R. F. NUSCALE, “Small Modular Reactor Human-System Interface and Control Room Layout Design,” Proc. Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Mtg., 63, 1, 516 (Nov. 2019); https://doi.org/10.1177/1071181319631102.