Figure 1. The author documenting the massive tower structure with the wadi in the background. Image courtesy of the author.

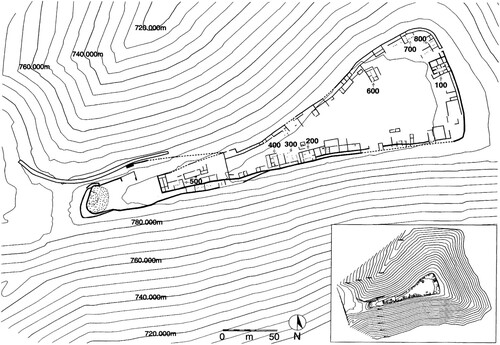

This report is on the 2022 survey season at Khirbet al-Mudayna al-‘Aliya (KMA for short), an early Iron Age site, dating to roughly the end of the 11th/early 10th century bce. The 2.3 ha site located in south-central Jordan was previously excavated by Bruce Routledge (University of Liverpool) over several seasons between 1994 and 2004. These excavations showed it was an Iron Age village which contained around 60 houses, in which people led seemingly regular lives (Farahani et al. Citation2016; Lev-Tov et al. Citation2011; Routledge Citation2000). There was little suggesting social hierarchy, long-distance trade, or other signs indicating anything other than regular Iron Age village life. That is, however, excluding the site’s massive fortification structures. KMA is surrounded by a casemate wall, which follows the contours of the promontory the site is situated on (see ). The only area of access to the site, from the west, is guarded by a substantial tower overlooking a dry moat.

Figure 2. Map of the site of KMA. Routledge Citation2000.

This juxtaposition of a regular village with massive fortifications is an enticing dilemma, for why would the Iron Age inhabitants of KMA have invested this effort to guard a relatively small and unremarkable village? This picture becomes increasingly interesting when zooming out, as KMA is not an isolated phenomenon. There are various similar sites located near KMA which, based largely on pottery typologies, seem to fall in the same period as KMA (Ninow Citation2004; Olavarri Citation1983; Routledge Citation2008; Routledge et al. Citation2014; Worschech et al. Citation1986).

KMA was securely dated through 14C samples of the site’s construction and eventual destruction. Interestingly, these dates show that it was constructed around 1060 bce and abandoned around 980 bce (Routledge et al. forthcoming). This leaves roughly 80 years for the construction, use and sudden abandonment of this massive site, raising many questions. Who constructed this site and for what purpose? Why was it abandoned after 80 years? How does the site fit with the aforementioned other fortified villages? Were these villages part of an early Iron Age kingdom as is often suggested (e.g., Finkelstein and Lipschits Citation2011), or are there other social dynamics at play which could explain the sudden investment in labour?

This survey season was designed to shed light on the investment of labour needed to construct such a site, by closely recording KMA’s many structures, paying particular attention to building techniques, potential quarrying locations, and the sequence of the site’s construction. In addition to the generous funding from the PEF, which was put towards airfare, funds were secured from the Wainwright Fund for Near Eastern Archaeology, the NWCDTP and the University of Liverpool to conduct this fieldwork season with a small team.

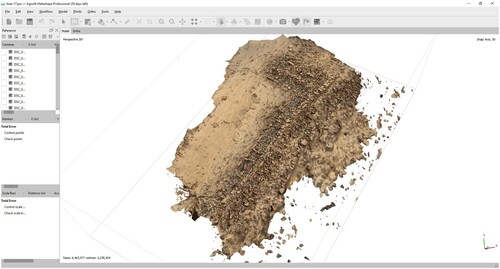

We set out to capture the entire site in 3D using photogrammetry. Photogrammetry software can reconstruct physical objects and the environment in 3D based on overlapping photographic images. Previously we had success capturing trenches and objects using this method but had rarely seen it applied at a scale like this. Ideally, such a scale would require the use of drones or kites, both of which are difficult to use in Jordan due to local restrictions, financial limitations, and weather conditions. Hence, we devised an experimental methodology in which the site would be divided into smaller sections which could be captured at several angles while fieldwalking using 2.5 m camera poles. Although trials in Liverpool looked promising, these were under significantly different conditions than those of south-central Jordan.

In the field the terrain proved difficult to traverse and differences in elevation challenging to properly capture. Furthermore, full and systematic coverage was not always straightforward due to the scale of the site. Fortunately, initial 3D models clearly indicated the feasibility of our methodology (see ) and where necessary we adjusted our tactics. Beginnings and ends of transects were marked with coloured flags to keep us on the right track, and areas with substantial differences in elevation were captured from additional angles. Our methodology proved effective, as we managed to capture the entire site in 8 working days.

Having achieved our initial goals earlier than expected we had time to also investigate the site’s eastern slope, on which previous investigations spotted remains of three cisterns (Routledge pers. comm.). On this slope we found remains of a previously unknown built road leading down towards the wadi. We furthermore discovered a total of 16 cisterns which were cut into the hill’s soft limestone layers (see ). These cisterns were in different states of preservation, some being near completely sanded up whereas others were remarkably well-preserved. The inner walls of several of these well-preserved cisterns held remains of plaster, which were sampled for further study at the University of Liverpool. The reinforced road led down to a final retaining wall guarding access up the slope to the cisterns. Protruding from this wall was a small built path leading down to the wadi proper. While these features have not yet been dated directly, due to their clear connection to the site, an early Iron Age date seems likely.

The 2022 fieldwork season at KMA can be regarded highly successful as the primary objectives were achieved and important new insights were gained, both in terms of methodology and our knowledge of the site. Our experimental methodology for capturing a site this size without the use of drones or kites proved feasible and effective. In addition to generating 3D models covering the entire site, which will allow for close-up analyses of the built structures on top of the site, we also managed to reinforce a previously assumed direct link between the site and the wadi with the road leading down the slope. Furthermore, carefully assuming the contemporaneity of the sixteen cisterns with the site proper of KMA, the new evidence gathered in the 2022 field season may enable us to approach issues on water management strategies at early Iron Age casemate sites. Furthermore, chemical analyses on the plaster samples will be conducted to determine their composition, which could also shed more light on early Iron Age plaster production. These results will be processed in the author’s PhD thesis, and eventually incorporated into the forthcoming final publication on the excavations at KMA.

Bibliography

- Farahani, A., et al., 2016. ‘Crop Storage and Animal Husbandry at Early Iron Age Khirbat al-Mudayna al-‘Aliya (Jordan): A Paleoethnobotanical Approach’, in K. M. McGeough (Ed.), The Archaeology of Agro-Pastoralist Economies in Jordan, Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 69, Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research 27–89.

- Finkelstein, I., and Lipschits, O., 2011. ‘The Genesis of Moab: A Proposal’, Levant, 43(2), 139–52.

- Lev-Tov, J. S. E., Porter, B. W., & Routledge, B. E., 2011. ‘Measuring Local Diversity in Early Iron Age Animal Economies: A View from Khirbat al-Mudayna al-’Aliya (Jordan)’, BASOR 361, 67–93.

- Ninow, F., 2004. ‘First Soundings at Khirbat al-Mu’mmariyyah in the Greater Wadi al-Mujib Area’, ADAJ, 48, 257–66.

- Olavarri, E., 1983. ‘La Campagne de Fouilles 1982 a Khirbet Medeinet al-Mu’arradjeh pres de Smakieh (Kerak)’, ADAJ, 27, 165–78.

- Routledge, B., 2000. ‘Seeing Through Walls: Interpreting Iron Age I Architecture at Khirbat al-Mudayna al-ʿAliya’, BASOR 319, 37–70.

- Routledge, B., 2008. ‘Thinking Globally and Analysing Locally — South-Central Jordan in Transition’, in L. L. Grabbe (ed.) Israel in Transition: From Late Bronze II to Iron Age II (ca. 1250-850 bce): 1 The Archaeology, London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC 144–76.

- Routledge, B., and Halbertsma, D. J. H., n.d. ‘Dating Events, not Periods: Towards Building a New Chronology of the Iron Age I Period’, Forthcoming.

- Routledge, B., et al., 2014. ‘A Late Iron Age I Ceramic Assemblage from Central Jordan: Integrating Form, Technology and Distribution’, in E. van der Steen, J. Boertien, and N. Mulder-Hymans (eds), Exploring the Narrative: Jerusalem and Jordan in the Bronze and Iron Ages: Papers in Honour of Margreet Steiner, London: Bloomsbury & T&T Clark 60–85.

- Worschech, U. F. Ch., Rosenthal, U., and Zayadine, F., 1986. ‘The Fourth Survey Season in the North-West Ard el-Kerak, and Soundings at Balu’ 1986’, ADAJ 30, 285–310.