ABSTRACT

This article presents the results of lead isotope analysis (LI) conducted on four bronze anklets from an early Iron Age burial (Burial D/F3) at the site of Ḥorvat Tevet, Israel. The results show that the copper in these items most likely originated in Timna. All the known LI data from the Late Bronze and early Iron Age southern Levant is then plotted to demonstrate that Arabah copper dominated the region in the early Iron Age. The significance of these objects for reconstructing exchange networks in the early Iron Age Jezreel Valley is briefly explored. We then turn to discussing the social meaning of these objects. Based on a catalogue of all known southern Levantine burials dated between the Late Bronze III (12th century bce) and Iron IIA (9th century bce) containing anklets or bracelets in association with skeletal remains with biological sex and age determinations, we conclude this was likely the burial of a high-status female.

Introduction

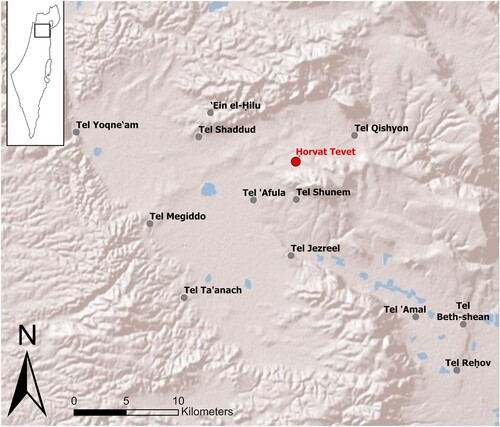

Ḥorvat Tevet is a small site located some 15 km north-east of Tel Megiddo in the north-eastern margins of the Jezreel Valley (). The site consists of three terraces sloping south to the northern bank of Naḥal Tevet at the foot of the Ha-Moreh Hill. Successive trial and salvage excavations at the site uncovered a sequence of nine occupational levels spanning the Late Bronze I–Medieval Periods.Footnote1 Throughout most of this time, Ḥorvat Tevet was the home of a rural community, whose subsistence economy was based on the nearby fields. It was only in the late Iron IIA that the site acquired its public nature, marked by a series of destructions and reconstructions (Sergi et al. Citation2021; Butcher et al. Citation2022; Spiciarich et al. Citation2023). The following article, however, will focus on the rural community that inhabited the site in the early Iron Age.

The earliest Iron Age occupation at Ḥorvat Tevet (Level 8) is associated with some scanty domestic remains (on the upper terrace), rock-cut pits (on all three terraces), and at least 25 burials on the northern margins of the site, all dated to the Iron I. Most of these burials were poorly furnished with just a few ceramic vessels as grave goods. One individual (Burial D/F3) however, was differentiated by a unique, more elaborate burial, which included four bronze anklets. The presence of jewellery in burials is a well-known phenomenon, but the use of bronze anklets and bracelets (‘bangles’) as burial offerings was specifically common in the southern Levant during the LB II–Iron IIA (Tufnell Citation1958; Green Citation2007, 287–94; Brody and Friedman Citation2007; Golani Citation2013, 144–50; Weitzel Citation2021, 84–6, 188–91; Braunstein Citation2018; Verduci Citation2018, 125–37; Citation2021). This is exactly the period during which copper production in the Arabah Valley grew in intensity, reaching an unprecedented peak in the Iron I/IIA (Levy et al. Citation2008; Ben-Yosef et al. Citation2012; Ben-Yosef Citation2016; Kleiman, Kleiman, and Ben-Yosef Citation2017). Studying the production techniques and origin of such items provides insight into exchange networks into which a rural community in the Jezreel Valley was integrated during the early Iron Age. Furthermore, examining the bronze anklets in their archaeological context sheds light on the meaning of these objects in both life and death for those who wore them.

In the following, we present the results of lead isotope analysis (LI) on four bronze anklets found in Ḥorvat Tevet Burial D/F3. By plotting this data against available LI data from other sites, we provide further evidence that Arabah copper came to dominate the southern Levant (and much of the eastern Mediterranean) in the early Iron Age. We will then discuss the significance of these objects for the reconstruction of exchange networks in the early Iron Age Jezreel Valley. Namely, there are implications that Tel Reḥov (located 25 km from Ḥorvat Tevet) was a major player in a northern branch of this trade. Finally, we argue that these, and other metal objects, were important symbols of both social rank and gender identity for rural elites in the Jezreel Valley.

The Iron I Cemetery in Ḥorvat Tevet

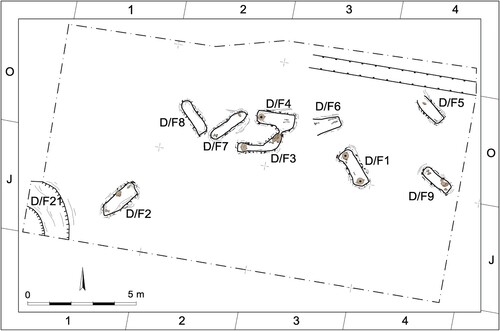

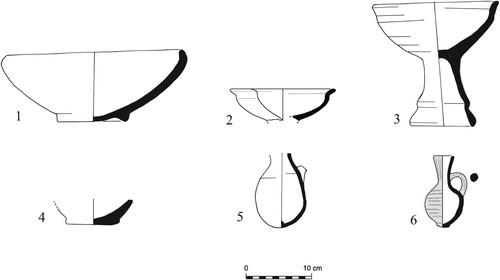

The Iron I cemetery extends over an area of at least 250 × 100 m along the northern outskirts of the site. The burials were found 0.3–0.5 m below the modern surface inside pits cut from the basaltic bedrock (). The acidity of the bedrock resulted in poor skeletal preservation, and thus only limited information regarding age, sex and body treatment could be determined. The ceramic assemblage from the graves consists of common, local Iron I forms, including rounded bowls with a simple or inverted rim, carinated bowls with an S-shaped profile (‘cyma’ bowls), chalices with a plain or flaring rim, dipper juglets with a rounded base and trefoil mouth, small lentoid flasks with two handles, ridge-necked (non-hippo) storage jars, and lamps with a pinched rim and rounded base (; ). These types have close parallels in Iron I strata, such as Tel Dan VI–IVB, Tel Hadar IV, Tel Hazor XII/XI, Tel Kinrot VI–IV, Tel Megiddo VI, Tel Reḥov VII and Tel Yoqne‘am XVIII–XVII (Weitzel Citation2021, 59–84 with references). Moreover, there was nearly a total absence of red-slipped and hand-burnished vessels that distinguish the Iron IIA ceramic horizon.

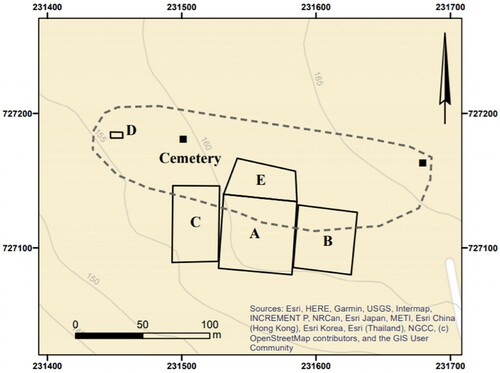

Figure 2. Excavation areas at Ḥorvat Tevet. The boundary of the cemetery is represented by the dotted line that encompasses all of Areas D and E and the northern parts of Areas A, B, and C (map by Anastasia Shapiro, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority).

Figure 3. Area D, where Burial D/F3 was found (modified by authors and Itamar Ben-Ezra after original drawing by Shatil Emmanuelov, courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University).

Figure 4. A selection of ceramics from the Iron I cemetery of Ḥorvat Tevet (drawing by Yulia Gottlieb, courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University).

Table 1. Descriptions of Vessels in .

On the other hand, two small juglets with handle attached mid-neck, often referred to as ‘black juglets’, were found in two of the burials (e.g., :6). This type is typically dated to the Iron IIA (Arie Citation2013, 705–6; Weitzel Citation2021, 74). Aside from this single type however, there are no other vessel types from the cemetery or from Level 8 that must be dated exclusively to the Iron IIA. Moreover, although this type becomes pre-eminent in the Iron IIA, one similar juglet was attributed to stratum VIA (Iron I) from Yigael Yadin’s excavation at Tel Megiddo, suggesting that production of this type had apparently begun at the time of Tel Megiddo’s destruction (Zarzecki-Peleg Citation2016, 39, :14, 285).Footnote2 The presence of these juglets pushes the date of the latest burials to the very end of the Iron I or the very beginning of the Iron IIA, i.e., the mid-10th century bce. Although when viewed in isolation this pottery could date as late as the 9th century, the overall number of burials and low burial density,Footnote3 the fact that Level 8 did not leave behind a thick layer of accumulation debris, and the lack of other fossiles directeures for the Iron IIA or the LB III (12th century bce), all suggest a short duration of the cemetery and nearby village. We, therefore, prefer to minimise the lifespan of the cemetery to the 11th–10th centuries bce, in accordance with radiocarbon results retrieved for Iron I strata from nearby sites (Lee, Bronk Ramsey, and Mazar Citation2013; Toffolo et al. Citation2022). Thus, the end date of the cemetery was close in time to, or even slightly later than, the destruction of Tel Megiddo VIA and contemporary strata.

The use of the cemetery by adults and sub-adults, males and females, the clustering of tombs, and the location of the village nearby, all imply that the cemetery was used by the family group(s) residing in the village of Ḥorvat Tevet Level 8. The burials reflect a society with a kin-based social structure and minimal accumulation of wealth. Therefore, the site was probably inhabited by a local kin-based community in the Iron I whose subsistence economy relied on the nearby fields, with minimum exchange with nearby rural and urban centres (Amir et al. Citation2021; Weitzel Citation2021; Weitzel et al. Citation2024).

Burial D/F3

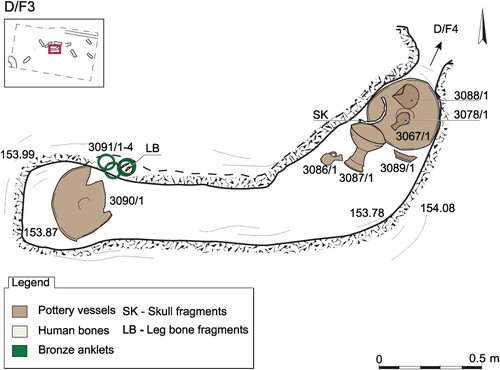

While most of the burials are simple pit burials containing similar sets of grave goods (the ‘funeral kit;’ cf. Baker Citation2012), one burial stood out as being unique. Burial D/F3 consisted of an L-shaped pit with a niche hollowed out on its northern side to form an overhanging rock ledge under which the body could be partly obscured (). The skeleton was poorly preserved. However, all the surviving elements were fully fused and thus can be assumed to belong to an adult individual.Footnote4 Despite poor skeletal preservation, the orientation of the body was inferred by the presence of lower leg remains on the western end of the pit and skull fragments adhering to a cluster of vessels on the eastern end (). Judging from the distance between the two elements, the individual was probably laid to rest in a fully extended position with the skull protruding out from underneath the rock ledge.

Figure 5. Plan of Burial D/F3 (modified by authors and Itamar Ben-Ezra after original drawing by Christopher Banbury, courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University).

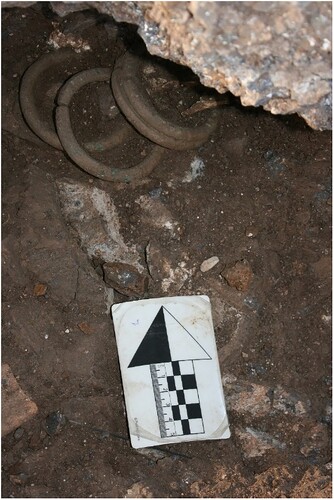

Figure 6. Anklets underneath the rock ledge on the western end of Burial D/F3. Note the small fragments of lower leg bone inside the anklets.

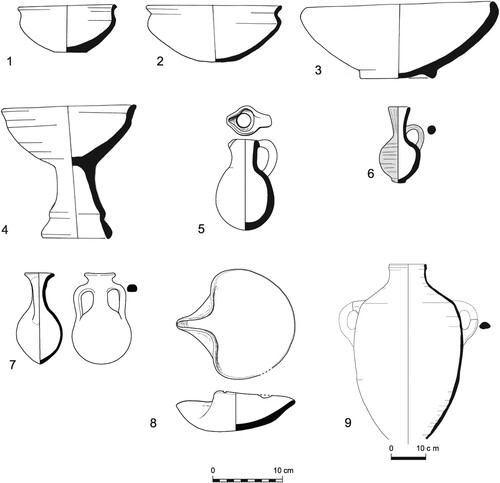

The north-eastern corner of the grave seemed to be intentionally connected with Burial D/F4 to the north, which held another adult burial and a jar burial (presumably of an infant). This suggests that these two units functioned together as a crude family tomb. A larger and more diverse ceramic assemblage accompanied the deceased in Burial D/F3 (; ). A storage jar with a dipper juglet (: 5) inside was placed on top of the eastern edge of Burial D/F3. At a depth of 0.2 m below the jar, a cluster of grave goods encircled the head of the deceased. This cluster consisted of a chalice (: 3), a lamp, the base of a closed vessel (: 4), and a juglet (8: 6). Residues of beeswax and animal fat detected inside the juglet, and animal fat in the chalice, are the remnants of mortuary ceremonies (Amir et al. Citation2021). A large bowl (Pl. 8: 1) was placed next to the feet. An additional chalice (: 2) was recovered from the grave fill above the body. North of the large bowl and under the rock ledge were four bronze anklets in which small lower leg bone fragments were found in situ (; ). Linen textile fragments preserved on the exterior of three of these anklets are the remains of attire worn by the deceased at the time of burial.

Figure 8. Ceramic Assemblage from Burial D/F3. Note: storage jar and lamp not illustrated (drawing by Yulia Gottlieb, courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University).

Table 2. Descriptions of Items in and (Contents of Burials D/F3).

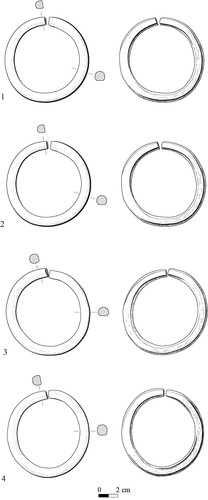

Figure 9. Bronze Anklets from Burial D/F3 (drawing by Yulia Gottlieb, courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University).

Burial D/F3 was notable for standing out in several ways. First, with its rock ledge covering the body, it featured a more elaborate burial pit. Second, Burial D/F3 contained double the number of objects and object types of any other burial in the cemetery. This larger and more diverse funeral kit suggests a more elaborate funeral with more actions being performed or symbolised, e.g., serving, pouring libations, storing, lighting, etc.

Furthermore, the anklets were the highest-quality objects found in the cemetery and the rarest. They were limited in their distribution to just one or two additional burials.Footnote5 The anklets were made of raw materials that had to be imported from afar, and could also be melted down and re-used (see below). To take several of these objects out of circulation was a conspicuous act that would have conveyed social prestige and a high level of wealth accumulation among the otherwise nondescript burials in the cemetery. Therefore, this burial apparently attests to a certain amount of wealth differentiation within the Iron I community at Ḥorvat Tevet.

The Bronze Anklets

The four bronze anklets from Burial D/F3 consist of an open bronze ring flattened on one side with a semi-circular cross-section (; ). The ring largely maintains its thickness as it approaches the terminals, which are squared off and almost touching. All four examples measured between 8 and 8.5 cm in outer diameter and ca. 6.5 cm in inner diameter. Their weight ranged between 121 and 133 g. Textile fragments were preserved on the exterior of the specimens in : 2–4.

These objects equate to Golani’s (Citation2013, 147) Type I.5, which occurs almost exclusively at sites in the Shephelah and Benjamin plateau and is mainly, though not exclusively, found in Iron IIA contexts. Like the juglet type described above, this emphasises the later date of Burial D/F3 in relation to most of the other burials in the cemetery. This type, however, is not very different from other open-ended bangle subtypes such as those with tapering and/or overlapping ends, rounded cross-sections, etc. that date primarily to the Iron I–II and have a wide distribution across the southern Levant (Golani Citation2013, 144–52; Verduci Citation2018, 127–33) and beyond (Curtis Citation2013, 107–10).

Elemental and Lead Isotope Analysis

In order to assess the composition and provenance of the anklets from Ḥorvat Tevet, the objects were subjected to chemical and lead isotope (LI) analysis.Footnote6 The results of the baulk chemistry are presented in . Although these items should technically be referred to as bronze, the measured tin content is only 1.1–2.7%. Such low and unstandardised Sn content barely affects the characteristics of the alloy (Fürtauer et al. Citation2013) and is usually regarded as an unintentional alloy (e.g., Craddock Citation1988). Accordingly, the anklets are probably made of recycled metal and not pure copper alloyed with fresh tin. Scrap metal was a widely used commodity in the Eastern Mediterranean during the early Iron Age (e.g. Budd et al. Citation1995; Hauptmann, Maddin, and Prange Citation2002; Yahalom-Mack et al. Citation2014); thus, it is not surprising to encounter artefacts that are made of such metals. Nevertheless, the chemical analysis suggests these items are made of fairly high-quality metal as shown by the very low content of elements such as silicon, calcium (representing slag or soil contamination in the metal) and iron (representing both slag or soil and metallic residues from the smelting process).

Table 3. Chemical composition of samples as determined by ICP-AES and ICP-MS. Results are in wt.%.

Table 4. Lead isotopic ratios and measurement of the analysed samples.

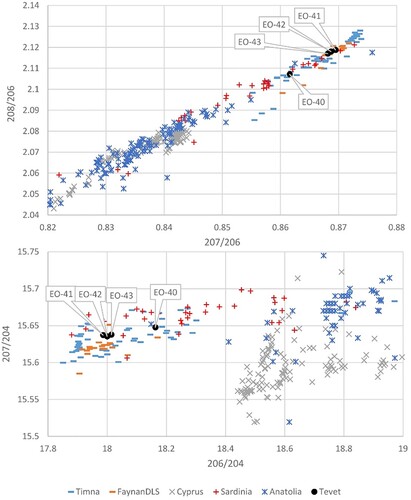

Complete LI results are presented in and plotted against relevant ore bodies from the Mediterranean basin (). The LI signature of the anklets agrees well with the data from the Arabah. They form two clusters, OE-40 and OE-41,42,43. The former is most probably derived specifically from Timna copper, as it does not match any known LI ratios of the DLS formation in Faynan. It should be noted that some Sardinian ores slightly overlap these of the Arabah and match the LI of the anklets from Ḥorvat Tevet; however, this option is much less likely based on geographical consideration and the fact that copper ingots from Sardinia tend to show much lower lead content than the metals from the Arabah (Begemann et al. Citation2001).

Figure 10. Ratios of the analysed objects compared with previously analysed ore specimens from potential sources in Timna (Gale et al. Citation1990; Dsael et al. Citation2012; Harlavan et al. Citation2017; Segal et al. Citation2015) and Faynan (Jansen Citation2011; Hauptmann Citation2000) in the Arabah, Sardinia (Begemann et al. Citation2001), Anatolia (Hiaro, Enomoto, and Tachikawa Citation1995; Hauptmann et al. Citation2002; Seeliger et al. Citation1985; Wagner et al. Citation1985; Wagner et al. Citation1986; Wagner et al. Citation1989) and Cyprus (OXALID).

Early Iron Age Metal Trade

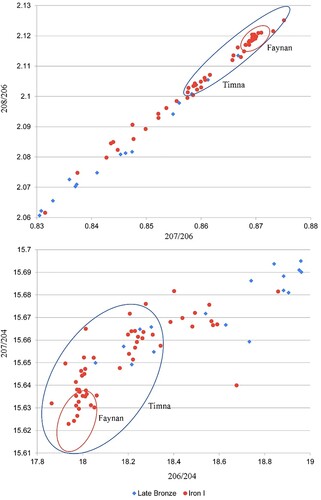

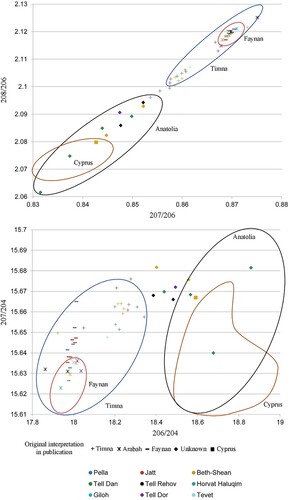

Although using LI analysis for provenance studies of ancient metals was already suggested more than fifty years ago, in the past decade it has been gaining more scholarly attention than ever before (Pernicka Citation2014). With this trend, in recent years several dozens of LI analyses of copper and copper-based objects from the Levant dated to the Late Bronze and Iron I have been published. The results of these analyses were grouped for the current research and are plotted together here in order to provide a wide perspective of the Iron I copper circulation and trade in the Levant. Also, in order to emphasise the contrast between the Late Bronze Age and Iron I Levantine copper trade, previously published LI data from Levantine Late Bronze copper objects were also gathered and plotted against Iron I data ().

Figure 11. LI results of copper artefacts from Late Bronze and Iron I contexts in the Levant divided according to chronology (Bruins, Segal, and van der Plicht Citation2018; Philip, Clogg and Dungworth Citation2003; Stos-Gale Citation2006; Yahalom-Mack and Segal, Citation2009; Yahalom-Mack and Segal, Citation2018, Citation2020).

Figure 12. LI results of copper artefacts and from the Levant divided by site and suggested source in original publication (citations are provided in ).

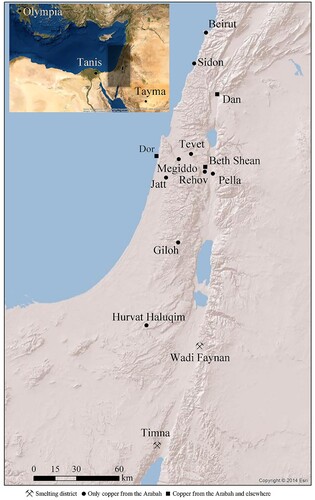

Figure 13. Map showing the distribution of copper in Levantine sites during the Iron I according to LIA. The small map shows sites beyond the Levant where copper from the Arabah was found in Iron I contexts. The dark square indicates the specific area represented on the larger map. In Megiddo, Sidon and Beirut, copper was matched only with Arabah ore (Eliyahu-Behar and Yahalom-Mack Citation2022; Vaelske, Bode, and El-Morr Citation2019). In these sites, however, LI data is not specified and thus do not appear in .

The following is a brief review of the Iron I data presented in . First, with regards to the Late Bronze/Iron I transition, a clear contrast between the copper sources of these periods is demonstrated by the LI data (Yahalom-Mack and Segal Citation2018; ). During the Late Bronze, copper from northern origins (Cyprus, Anatolia and Greece) dominated the Levantine markets. In contrast, in the course of the Iron I, the copper in Levantine settlements overwhelmingly originated from the Arabah. This dichotomy, however, is incomplete; Yahalom-Mack and Segal (Citation2018) show that copper from the Arabah had already reached as far as Tel Dan during the Late Bronze, and during the Iron I, metal from the north was found in few sites within the Levant (alongside metal from the Arabah, see ).

As industrial scale smelting operations in Timna (in the southern Arabah) began in the course of the Late Bronze (Erickson-Gini Citation2014; Yagel, Ben-Yosef, and Craddock Citation2016), it is not surprising to find its products in Levantine settlements during this period. Nevertheless, with the start of the vastly more intense smelting operations in Faynan during the Iron I (Levy, Najjar, and Ben-Yosef Citation2014), Arabah copper completely dominated the regional markets. In fact, out of sixty-three sampled copper objects from secure Iron I contexts in the Levant, only one was suggested to be of northern origins (Sample BS-1B from Beth-Shean, in Yahalom-Mack and Segal Citation2009) and ten are said to originate from unknown sources (). Interestingly, while some of these unknown origins should probably be viewed as northern, LI ratios that fall in between data from different ore fields could imply the recycling and mixing of Arabah and northern copper (Yahalom-Mack, Finn and Ezrel. Citation2023). In addition to the above, LI data of Iron I copper assemblages from Saudi Arabia (Renzi et al. Citation2016), Egypt (Evian et al. Citation2021; Schulze and Lehmann Citation2014; Vaelske, Bode, and Loeben Citation2019) and Greece (Kiderlen et al. Citation2016) also match the Arabah ore field. The LI results show that the Arabah smelting industries were the main copper supplier of the Levantine region during the Iron I (Yahalom-Mack, Finn and Ezrel Citation2023), and probably even in the entire eastern Mediterranean.

The Bronze Anklets from Ḥorvat Tevet: Economy and Exchange

As demonstrated above, the four anklets in Burial D/F3 were produced from recycled copper that was sourced from Timna in the Arabah Valley. Despite wide exposure of the site, no evidence for metalworking has been found at Iron I Ḥorvat Tevet. Furthermore, jewellery moulds have only been found at urban centres, where specialised metalsmiths apparently resided (Golani Citation2013, 23, n. 46). For these reasons, the anklets in Burial D/F3 were likely acquired from a nearby city.Footnote7

Notably, the best parallel for this bangle type from a northern site is probably an unpublished specimen from Tel Beth-Shean (Golani Citation2013, 147). This joins further evidence which points to the integration of Iron I/IIA Ḥorvat Tevet into the socio-economic sphere of the Beth-Shean Valley (e.g., Mazar Citation2020, 103–4, 115–16; Amir et al. Citation2021; Butcher et al. Citation2022; Spiciarich et al. Citation2023).

Other than the four bronze anklets, the material associated with the Ḥorvat Tevet cemetery reflects integration within local trade networks. The ceramic assemblage was comprised exclusively of local types. Thus, all vessels used in the graves were likely produced in the site environs or acquired through local exchange. Furthermore, linen found on the bronze anklets from Burial D/F3 was of local production (Orit Shamir, personal communication), and it could have possibly originated in the nearby Beth-Shean Valley, which was a centre for linen textile production in the Iron I/IIA (Shamir Citation1996, 140–142; Boertien Citation2013; Mazar Citation2019). Finally, 13 vessels within the graves contained the remains of heated beeswax (Amir et al. Citation2021). Growing evidence suggests that bee-keeping was an important part of the economy of the Beth-Shean and eastern Jezreel Valleys during the Late Bronze III–Iron IIA. In addition to the evidence from Ḥorvat Tevet and Tel Reḥov (see below), residue of beeswax was discovered inside a clay anthropoid coffin at Tel Shaddud that was produced in the Beth-Shean Valley (van den Brink et al. Citation2017, 111–14; Namdar et al. Citation2017; Beeri, van den Brink, and Kirzner Citation2021, 13). Honey or beeswax was also found inside storage jars included as burial offerings at the site (Beeri, van den Brink and Kirzner Citation2021, 13, 17).

To date, the only apiary known archaeologically in the entire Bronze and Iron Age Near East was found in Tel Reḥov Stratum V (Mazar and Panitz-Cohen Citation2020). This stratum is dated to the beginning of the late Iron IIA, meaning that Tel Reḥov was a production centre for beeswax during the late 10th–early 9th century bce. However, apiculture there could have begun even earlier. The excavator recently described how the site developed peacefully throughout the Late Bronze to Iron IIA without any major destruction events, and exhibited much continuity in its material culture traditions (Mazar Citation2020). Notably, beeswax was also used in the lost wax technique for producing bronze objects and thus likely related to the Arabah copper trade (Mazar Citation2016, 103). This could also be an explanation for how the bronze anklets reached the site. The discovery of beeswax at Ḥorvat Tevet and Tel Shaddud seems to relate the central and eastern Jezreel Valley to the overall production patterns visible in the early Iron Age Beth-Shean Valley. The presence of metal jewellery in some of the burials suggests an interaction between a few local elites at Ḥorvat Tevet and an urban centre that was involved in the Arabah copper trade. One candidate would be Tel Reḥov – the major urban centre of the Beth-Shean Valley. This reconstruction raises the possibility, already discussed by Mazar (Citation2020, 105), that some of the copper produced in the Arabah made its way to Tel Reḥov and the Beth-Shean Valley, and was even traded and exported from there to the Phoenician coast, which could also explain the unprecedented continuous prosperity of Tel Reḥov in the Iron I–IIA.

The Bronze Anklets from Ḥorvat Tevet in Context: Symbolism and Identity Construction in a Rural Community

Previous studies have noted correlations between the practice of wearing bangles with sub-adults/adult female burials (Braunstein Citation1998, 293, 295; Green Citation2006, 520–22, Tables 5.1–5.2; Braunstein Citation2018). Green (Citation2007) concluded that while single anklets have been found on male/female and adult/sub-adult skeletons, multiple anklets are found only on sub-adult and biologically female skeletons. For this study, we assembled a database of 75 burials from the southern Levant dated to the Late Bronze III–Iron IIA in which there was a clear object-body association between metal bangles and individuals with either age or sex determinations ().

Table 5. Burials in the southern Levant with sex or age identification with bangles in situ (Late Bronze III–Iron IIA)

Bangles are most often found with sub-adults (45 burials). In adult burials, single anklets were rare, and in both cases were found on individuals who were also wearing one bracelet (two burials). Whenever found with adults with sex identification, multiple anklets and multiple bracelets are found only with individuals either sexed as female or whose sex was not identified (14 burials).Footnote8 To the best of our knowledge, not even a single Late Bronze or Iron Age burial has yet been found in the southern Levant in which a securely identified adult male was found with multiple anklets or multiple bracelets. The only secure occurrences of bangles with biological males at all are Tell es-Sa’idiyeh T. 177 and T. 218A (Tubb and Rowan Citation1988, 78; Green Citation2007, 293). This is corroborated by Levantine visual sources, which depict females adorned with multiple anklets, while male figures are mainly shown wearing single anklets (Green Citation2007, 297–303; Golani Citation2013, 150–2; Verduci Citation2021, 132; with earlier references). Since Ḥorvat Tevet Burial D/F3 was osteologically identified as an adult, sub-adult age can be ruled out for this individual. Therefore, Burial D/F3 likely held an adult female. The identification of the ‘richest’ burial in the Iron I cemetery at Ḥorvat Tevet as an adult female and its association with metal objects provides important insights into how gender identity was symbolised in this rural community in both life and death.

The apertures of the anklets in Burial D/F3 measured just 6.5 cm in inner diameter. These would have been difficult to slip over the foot of a grown adult; and, due to their rigidity, prying them open would have required considerable force and the help of tools (Green Citation2007, 295). Thus, these objects may have been put on the individual at a younger age and then grown into. Whatever the case may be, as objects made of valuable, recyclable bronze, the choice not to remove these items and to bury them must have been deliberate. Despite this, the anklets were hidden under the deceased’s attire at the time of final interment, suggesting that the person was already identified with the anklets, and it was unnecessary for the funeral participants to see the objects during the ceremony.

These objects were probably not specific to the funeral kit, but instead worn in everyday life as a semi-permanent part of the body (Verduci Citation2021, 129). The fact that bangles appear often on figural depictions of females who are interpreted as goddesses of sexuality also suggests a connection with sex and high-status (Bahrani Citation2001, 157–8; Green Citation2007, 300; Benzel Citation2013; Verduci Citation2021, 132–4). At the same time, the fact that bangles are associated with sub-adults suggests that even bangle-wearing individuals classified as adult females according to bioarchaeological data could have held a sub-adult status within the society (Green Citation2006, 139–40; Braunstein Citation2018, 55). Yet, these objects should be associated with only a select group of females. Although skeletal data is sparse, assuming ca. 50% of those buried in southern Levantine cemeteries were females, only a small minority are found with bracelets/anklets. Therefore, these probably represent a case of intersecting vertical rank and gender identity.

Ironically, the four bronze anklets found in Ḥorvat Tevet Burial D/F3, may have simultaneously denoted a high social status while also restricting the wearer’s freedom of movement. While the total weight of the four items in Burial D/F3 was not huge, the hardness of the anklets would have caused discomfort while walking when an anklet struck against the ankle (Verduci Citation2021, 135), or if care was not taken to prevent chafing.Footnote9 In addition, the wearing of anklets in stacks would have created a tinkling, musical sound when walking, and thus drawing constant attention to the wearer and creating the inability to move in silence. This sound is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible in a passage which also associates bangles with females and with the outward display of wealth (Isa 3:16–24).

Ethnographic evidence suggests that anklets often relate to status and wealth display in Middle Eastern society. For example, a nineteenth-century ce traveller’s account reports visiting a Bedouin encampment in Sinai and seeing the wives of the sheikh wearing elaborate jewellery sets, including heavy silver anklets (Paine Citation1859, 259–62). In Palestinian and some north African marriages, bangles and other types of ornaments can be given to the bride as a bride-price or as a gift from friends or relatives in preparation for the wedding (Granqvist Citation1931, 145–6; Fisher Citation1984, 241). A similar practice is reflected in Gen 24, in which Abraham’s servant presents Rebekah with a gold nose ring and two bracelets in exchange for marrying Isaac (Platt Citation1992, 826). Whether bangles were obtained at marriage or were placed on individuals at a young age and grown into, they served as a wearable form of wealth, and in many societies such items even function as currency. It has been argued, for example, that weights of ancient Near Eastern bangles correspond to known exchange standards (Lassen Citation2000, 241–4; Green Citation2007, 296; Brody and Friedman Citation2007, 99, 103 with further references).

A relatively large number of burials dated to the Late Bronze III–Iron IIA were excavated to varying degrees throughout the rural hinterland of the Jezreel Valley at the sites of Tel ʽAfula, Tel Qiri, Tel Kedesh, Tel Qishyon, Tel Shaddud, Kfar Yehoshua, and Nahal Yifat (Sukenik Citation1948, 8–13; Dothan Citation1955, 41–4; Druks Citation1966; Stern and Beit-Arieh Citation1973, 122, Citation1979, 13; Arnon and Amiran Citation1981, 206–7, Citation1993, 873–4; Arie Citation2011, 258–72, 299–303, 311–13; Yannai Citation2011; van den Brink et al. Citation2017; Beeri, van den Brink, and Kirzner Citation2021; Golani, Berger, and van den Brink Citation2021, 26*; Beeri Citationforthcoming; Beeri and Bron Citationforthcoming). Some of these yielded metal objects. Most of these cemeteries are characterised by a small number of well-furnished burials, differentiated by larger assemblages of ceramic grave goods, higher quality grave goods, and more elaborate graves. Metal objects seem to be the main characteristic that distinguishes a few burials in each cemetery. For example, one form of funeral kit includes a set of multiple bronze bangles (as in Burial D/F3). At Tel Shaddud, there was one example of this kit in the Iron I burials (T.2) and one example among the Iron IIA burials (T.35). The latter also included a shell necklace (Arie Citation2011, 265–8). Another distinctive type of burial is that equipped with bronze or iron knives and daggers. Bronze knives or daggers were found in the Tel Shaddud anthropoid burial and at Kfar Yehoshua (Druks Citation1966, 214; van den Brink et al. Citation2017, 117). Single occurrences of bronze knives or daggers were also found at Tel Kedesh T.1 and out of context at Nahal Yifat (Stern and Beit-Arieh Citation1979, 21, : 16; Arie Citation2011, 260). Iron knives were found in Tel Shaddud T.238 and T.247. In Tel Shaddud T.247, the knife co-occurred with an iron sickle and fibula (Beeri and Bron Citationforthcoming). These burials generally also contained a higher number of ceramic offerings (5 to 14). The burial of a biological female at Tel Qishyon, which yielded twenty ceramic objects, also appears to be another elite burial, albeit without any metals.

Several burials with possible or probable sex and age identifications are among these ‘elite’ burials. This allows for hypothesising different forms of status enhancement used for males and females. For instance, Ḥorvat Tevet Burial D/F3 and the female tomb at Tel Qishyon are two of the highest-ranking burials in the Iron I–IIA Jezreel Valley and these are both the probable burials of females. In addition, Tel Shaddud T.2 and T.35 contained sets of bronze anklets/bracelets (Arie Citation2011, 265, 269). For the reasons described above, this strongly suggests that these burials held either children or adult females. On the other hand, when sex identification is possible, the deposition of knives, daggers, or spearheads is exclusively found in male burials, and is thus apparently an expression of elite male identity.Footnote10

Conclusion

According to LI analysis, the most likely origin for the copper in four bronze anklets found in Burial D/F3 at Ḥorvat Tevet comes from Timna in the Arabah Valley. When added to LI data obtained from other sites, it is clear that Arabah copper dominated the Levantine copper trade in the early Iron Age. This data could also be evidence for a branch of the Arabah copper trade that travelled north into the Beth-Shean Valley. The small community at Ḥorvat Tevet probably did not have direct relations with Arabah copper production sites but was instead related to an urban centre that did. At least one candidate is Tel Reḥov – a large and well-connected city that prospered throughout the Late Bronze and early Iron Age and with which Ḥorvat Tevet appears to have other material culture connections in the Iron I/IIA.

Within the community, these items were used to construct aspects of social rank and gender identity. The individual in Burial D/F3 was differentiated in burial from the general population, including by the wearing of anklets, which signalled social prestige and wealth. However, ‘the dead do not bury themselves’ (Parker Pearson Citation1993: 203, Citation1999: 3). Ultimately, the choice to prepare Burial D/F3 as an outstanding burial was the deliberate choice of those who participated in the funeral. The relative wealth of the grave goods assemblage may not reflect the wealth or power of the deceased per se, but instead reflect the wealth of family members who buried the individual. It is also notable that the ostensibly wealthiest burial in the cemetery was likely the burial of a female. However, since the marker of female identity in this case was apparently also a marker of vertical social rank, both social rank and gender identity can intersect to produce distinctive funeral kits.

Acknowledgements

This study is the outcome of a research project titled ‘The Archaeological Expression of Palace–Clan Relations in the Iron Age Levant: A Case Study from the Jezreel Valley, Israel,’ funded by the Gerda Henkel Stiftung (AZ 20/F/19) and directed by Omer Sergi, Hannes Bezzel and Karen Covello-Paran. Partial support was also provided by the Israel Science Foundation grant nos. 1880/17 and 408/22 to Erez Ben-Yosef. The illustrations were prepared by Yulia Gottlieb, Itamar Ben-Ezra and Omer Zeevi, and we extend our gratitude to them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jordan Weitzel

Jordan Weitzel (MA in Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures, 2021, Tel Aviv University) is a PhD student at the University of California, Berkeley. His research interests revolve around the society, economy, and polities of the Levant during the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Omer Sergi

Omer Sergi, Senior Lecturer, Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures, Tel Aviv University. PhD (2013), Tel Aviv University; Post-Doc, Karls-Ruprecht University Heidelberg (2012–14); Associate Lecturer, Ancient Israel Studies, Tel Aviv University (2015–21); Senior Lecturer, Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures (since 2022); Co-Director, Ḥorvat Tevet Salvage Excavations (2018–19); Co-director research project “The Archaeological Expression of Palace-Clan Relations” (2019–23); Co-director, Tel Shaddud Regional Project (since 2022).

Karen Covello-Paran

Karen Covello-Paran, senior field and research archaeologist in the Archaeological Research Department, Israel Antiquities Authority. PhD (2015) Tel Aviv University; lecturer at International MA Program in Ancient Israel Studies, Tel Aviv University; Co-director, research project “The Archaeological Expression of Palace-Clan Relations” (2019–23); Co-director, The Tel Shaddud Regional Project (since 2022).

Hannes Bezzel

Prof. Dr Hannes Bezzel, Professor for Old Testament Studies, Friedrich Schiller-University, Jena. Born in 1975; studied protestant theology in Göttingen, Zurich, and Munich; 2007 Dr. theol. Göttingen; 2010 Junior professor for Old Testament Studies, Jena; 2014 Habil. Jena; since 2015 Professor for Old Testament Studies, Jena; Co-director, research project “The Archaeological Expression of Palace-Clan Relations” (2019–2023).

Omri Yagel

Omri Yagel (MA in Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures, 2017, Tel Aviv University) is a PhD student at the Tel-Aviv University. His research interests revolve around archaeometallurgy, ancient technologies, metal trade and the copper industries of the Arabah Valley during the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Yehudit Harlavan

Dr Yehudit Harlavan, Researcher, The Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem. Amongst research interests are provenance studies of silisiclastic sediments and ancient artefacts using iso-geochemistry tools, mainly the isotopic systems of Pb, Sr and Nd.

Erez Ben-Yosef

Erez Ben-Yosef is Professor of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University’s Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures. Since 2012 he directs the Central Timna Valley Project, a multidisciplinary research into copper production and trade during the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Notes

1 Trial excavations were carried out on behalf of the IAA in the cemetery (Abu Zidan Citation2013), on the upper and middle terraces (directed by Karen Covello-Paran, 2012) and on the lower terrace (directed by Yoav Tzur, 2018–19). They were followed by two seasons of extensive salvage excavations on the upper and middle terraces of the site, carried out by the Israeli Institute of Archaeology on behalf of the Sonia and Marco Institute of Archaeology in Tel Aviv University (directed by Omer Sergi in 2018, and by Omer Sergi and Rachel Lindemann in 2019).

2 Cf. also Singer-Avitz Citation2016, 235 on the possible Iron I dating of this vessel type.

3 By comparison, the nearby cemetery of Tel Shaddud, in a similar geographic and social context, covers an area of comparable size to Ḥorvat Tevet and reportedly contained hundreds of burials just from the area of the water reservoir southwest of the tel (Raban Citation1977, 14; Arie Citation2011, Plan 9.4.1).

4 The skeletal remains were analysed by Rachel Kalisher.

5 Aside from Burial D/F3, bangles were also found in a burial excavated by Abu Zidan (Citation2013). Abu Zidan also found two bangles out of context.

6 The analyses were carried out at the geochemical laboratory of the Israel Geological Survey according to the following procedure: To avoid external contamination, samples were slightly polished and then drilled in a clean hood using a Dremel 3000 equipped with a 2mm drill bit. Swarf (c. 30–70mg) was then collected and dissolved in Aqua Regia (HNO3:HCl 1:3) dried and diluted with 3.1 M HCl up to 50ml. From each solution, 2ml were evaporated and re-diluted with 0.1 M HNO3 for ICP-MS (Perkin Elmer NexION,) and Atomic-Emission-Spectrometer (ICP-AES, Optima-3300) elemental analyses. Internal standards were added (Rh-Re and Sc, respectively), and international standards were analysed along the studied samples. Lead was separated using the routinely used ion-chromatography method. Isotopic compositions of Pb (LI) were measured using a Nu Plasma HR-MC-ICP-MS instrument. Mass discriminations were corrected using internal Tl standard and repeated measurements of the SRM-981 standard.

7 That said, the moulds listed by Golani are all made of stone and were mostly found in Late Bronze Age contexts. Moreover, they were not used to produce the specific bangle type under examination here. This could imply that jewellery production techniques underwent a change in the transition from the Late Bronze to early Iron Age. The possibility that some jewellery (or at least this bangle type) was produced in moulds that do not preserve well in the archaeological record, such as sand moulds (Merkel Citation1986, 259; Van Lokeren Citation2000, 275; Kassianidou Citation2001, 101) or clay moulds that broke as part of the lost wax casting technique (Rose, Fabian, and Goren Citation2023), should also be considered.

8 For the purposes of this study, adult is defined as post-pubescent, i.e., the point at which it becomes possible to differentiate biological sex according to morphological features. We understand this may not be how the society we are studying defined adulthood (cf. Braunstein Citation2018, 54–5).

9 Among the Igbo people of western Africa, the discomfort of walking while wearing bronze anklets causes the female wearer to change her gait, in a way that is considered sexually attractive in the society (Fisher Citation1984, 73).

10 Neighbouring regions have, however, occasionally produced biological female burials equipped with knives (e.g., Green Citation2006, 137).

Bibliography

- Abu Zidan, F., 2013. ‘Horbat Tavat’, Hadashot Arkheologiyot: Excavations and Surveys in Israel 125, <http://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/report_detail_eng.aspx?id=5435&mag_id=120> [accessed 10 October 2022].

- Amir, A., et al., 2021. ‘Heated Beeswax Usage in Mortuary Practices: The Case of Ḥorvat Tevet (Jezreel Valley, Israel) ca. 1000 bce’, JAS: Reports 36, 1–11.

- Arie, E., 2011. “In the Land of the Valley”: Settlement, Social and Cultural Processes in the Jezreel Valley from the End of the Late Bronze Age to the Formation of the Monarchy (unpublished doctoral thesis), Tel Aviv University (Hebrew with English abstract).

- Arie, E., 2013. ‘The Iron IIA Pottery’, in I. Finkelstein, D. Ussishkin, and E. H. Cline (eds), Megiddo V: The 2004–2008 Seasons, Vol. II, Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 31, Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology of the Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, 668–828.

- Arnon, C. and Amiran, R., 1981. ‘Excavations at Tel Qishon – Preliminary Report on the 1977–1978 Seasons’, ErIsr 15, 205–12 (Hebrew).

- Arnon C. and Amiran R., 1993. ‘Tel Kishion’, New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Vol. 3, Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society / Carta, 873–4.

- Bahrani, Z., 2001. Women of Babylon: Gender and Representation in Mesopotamia, London / New York: Routledge.

- Baker, J. L., 2012. The Funeral Kit: Mortuary Practices in the Archaeological Record, New York: Routledge.

- Beeri, R., forthcoming. ‘The Ceramics of the Iron Age IIA at Tel Shaddud−Area B’ (Hebrew).

- Beeri, R. and Bronn, E., forthcoming. ‘Stratigraphy of Area B’ (Hebrew).

- Beeri, R., van den Brink, E. and Kirzner, D., 2021. ‘Canaanite Burial Customs, Anthropoid Coffin Burials and Egyptian Rule in the Jezreel Valley in the Late Bronze Age in Light of an Excavation at Tel Shaddud’, Cathedra 177, 9–34.

- Beherec, M.A., 2011. Nomads in Transition: Mortuary Archaeology in the Lowlands of Edom (Jordan) (Unpublished doctoral thesis), University of California, San Diego.

- Beherec, M.A., Najjar, M., and Levy, T.E., 2014. ‘Wadi Fidan 40 and Mortuary Archaeology in the Edom Lowlands', in T.E. Levy, M. Najjar, and E. Ben-Yosef (eds), New Insights into the Iron Age Archaeology of Edom, Southern Jordan, Vol. 1, Surveys, Excavations and Research from the University of California, San Diego-Department of Antiquities of Jordan, Edom Lowlands Regional Archaeology Project (ELRAP), Monumenta Archaeologica 35, Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 665–721.

- Ben-Yosef, E., 2016. ‘Back to Solomon’s Era: Results of the First Excavations at “Slaves’ Hill” (Site 34, Timna, Israel)’, BASOR 376, 169–98.

- Ben-Yosef, E., et al., 2012. ‘A New Chronological Framework for Iron Age Copper Production in Timna (Israel)’, BASOR 367, 31–71.

- Benzel, K., 2013. ‘Ornaments of Interaction: Jewelry in the Late Bronze Age’, in J. Aruz, S. B. Graff, and Y. Rakic (eds), Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C., New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 258–67.

- Begemann, F., et al., 2001. ‘Chemical Composition and Lead Isotopy of Copper and Bronze from Nuragic Sardinia’, EJA 4, 43–85.

- Ben-Shlomo, D., 2012. The Azor Cemetery: Moshe Dothan’s Excavations, 1958 and 1960, IAA Reports No. 50, Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Boertien, J., 2013. Unravelling the Fabric: Textile Production in Iron Age Transjordan (unpublished doctoral thesis), University of Gröningen.

- Braunstein, S. L., 1998. The Dynamics of Power in an Age of Transition: An Analysis of the Mortuary Remains of Tell el-Far'ah (South) in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age (unpublished doctoral thesis), Columbia University.

- Braunstein, S. L., 2018. ‘Children and Bangles in the Late-Second Millennium bce Southern Levant’, in F. Pedde and N. Shelley (eds), Assyromania and More: In Memory of Samuel M. Paley, Studies in Near and Middle Eastern Archaeology 4, Münster: Zaphon, 49–67.

- Brody, A. and Friedman, E., 2007. ‘Bronze Bangles from Tell en-Nasbeh: Cultural and Economic Observations on an Artifact Type from the Time of the Prophets’, in R. B. Coote and N. K. Gottwald (eds), To Break Every Yoke: Essays in Honor of Marvin L. Chaney, The Social World of Biblical Antiquity, Second Series 3, Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix, 97–114.

- Bruins, H .J., Segal, I., and van der Plicht, J., 2018. ‘Bronze Chisel at Horvat Haluqim (Central Negev Highlands) in a Sequence of Radiocarbon Dated Late Bronze to Iron I Layers’, in E. Ben-Yosef (ed.), Mining for Ancient Copper: Essays in Memory of Beno Rothenberg, Tel Aviv University Monograph Series 37, Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, 16–27.

- Budd, P. et al., 1995. ‘Oxhide Ingots, Recycling and the Mediterranean Metals Trade’, JMA 8, 1–32.

- Butcher, M. et al. 2022. ‘The Late Iron IIA Cylindrical Holemouth Jars and their Role in the Royal Economy of Early Monarchic Israel’, TelAviv 49, 205–29.

- Craddock, P., 1988. ‘The Composition of the Metal Finds,’ in B. Rothenberg (ed.), Researches in the Araba 1959-1984, Vol. 1, The Egyptian Mining Temple at Timna, London: Institute of Archaeo-Metallurgical Studies, 169–80.

- Curtis, J., 2013. An Examination of Late Assyrian Metalwork with Special Reference to Nimrud, Oxford / Oakville: Oxbow Books.

- Dothan, M., 1955. ‘The Excavations at ‘Afula’, ‘Atiqot 1, 19–70 (Hebrew).

- Dsael, D., et al., 2012. ‘Tracking Redox Controls and Sources of Sedimentary Mineralization Using Copper and Lead Isotopes’, Chemical Geology 310, 23–35.

- Erickson-Gini, T., 2014. ‘Timna Site 2 Revisited,’ in J. M. Tebes (ed.), Unearthing the Wilderness: Studies on the History and Archaeology of the Negev and Edom in the Iron Age, Ancient Near Eastern Studies Supplement 5, Leuven / Paris / Walpole: Peeters, 47–84.

- Druks, A., 1966. ‘A “Hittite” Burial near Kfar Yehoshua’, BIES 30, 213–20 (Hebrew).

- Eliyahu-Behar, A. and Yahalom-Mack, N., 2022. ‘Appendix I: The Area Q Hoard, Analysis of the Metal Objects and the Beads’, in I. Finkelstein and M. A. S. Martin (eds), Megiddo VI: The 2010–2014 Seasons, Vol. III, Tel Aviv University Monograph Series 41, University Park / Tel Aviv: Eisenbrauns / Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, 1170–75.

- Evian, S. B. D., et al., 2021. ‘Pharaoh’s Copper: The Provenance of Copper in Bronze Artifacts from Post-Imperial Egypt at the End of the Second Millennium bce’, JAS: Reports 38, 103025.

- Fisher, A., 1984. Africa Adorned, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

- Fischer, P.M., Bürge, T., and al-Shalabi, M.A., 2015. ‘The “Ivory Tomb” at Tel Irbed, Jordan: Intercultural Relations at the End of the Late Bronze Age and the Beginning of the Iron Age', BASOR 374, 209–32.

- Fürtauer, S., et al. 2013. ‘The Cu-Sn Phase Diagram, Part I: New Experimental Results,’ Intermetallics 34, 142–7.

- Gale, N. H. et al., 1990. ‘The Adventitious Production of Iron in the Smelting of Copper’, in B. Rothenberg (ed.), Researches in the Arabah 1959-1984, Vol. 2, The Ancient Metallurgy of Copper, London: Institute of Archaeo-Metallurgical Studies, 182–91.

- Green, J. D. M., 2006. Ritual and Social Structure in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age Southern Levant: The Cemetery at Tell es-Sa’idiyeh, Jordan (unpublished doctoral thesis), University of London.

- Green, J. D. M., 2007. ‘Anklets and the Social Construction of Gender and Age in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age Southern Levant’, in S. Hamilton, R. D. Whitehouse and K. I. Wright (eds), Archaeology and Women: Ancient and Modern Issues, Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 283–311.

- Golani, A., 2013. Jewelry from the Iron Age II Levant, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis Series Archaeologica 34, Freiburg / Göttingen: Academic Press / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Golani, A., Berger, U., and van den Brink, E. C. M. 2021. ‘The Renewed Excavations at Tel Qishyon (Qišyôn)—An Interim Summary’, in K. Covello-Paran, A. Erlich, and R. Beeri (eds), New Studies in the Archaeology of Northern Israel, Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 13*–29*.

- Granqvist, H., 1931. Marriage Conditions in a Palestinian Village, Societas Scientiarum Fennica Commentationes Humanarum Litterarum III.8, Helsingfors.

- Guy, P. L. O. and Engberg, R., 1938. Megiddo Tombs, OIP XXXIII, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Harlavan, Y., et al., 2017. ‘Tracing the Sources of Sedimentary Cu and Mn Ores in the Cambrian Timna Formation, Israel Using Pb and Sr Isotopes’, Journal of Geochemical Exploration 178, 67–82.

- Hauptmann, A. 2000. Zur frühen Metallurgie des Kupfers in Fenan/Jordanien, Der Anschnitt: Beiheft 11, Veröffentlichungen aus dem Deutschen Bergbau-Museum Bochum 87, Bochum: Dt. Bergbau-Museum.

- Hauptmann, A., Maddin, R. and Prange, M., 2002. ‘On the Structure and Composition of Copper and Tin Ingots Excavated from the Shipwreck of Uluburun’, BASOR 328, 1–30.

- Hauptmann, A., et al., 2002. ‘Chemical Composition and Lead Isotopy of Metal Objects from the “Royal” Tomb and Other Related Finds at Arslantepe, Eastern Anatolia’, Paléorient 28, 43–69.

- Hiaro, Y., Enomoto, J. and Tachikawa, H., 1995. ‘Lead Isotope Ratios of Copper Zinc and Lead Minerals in Turkey - in Relation to the Provenanca Study of Artifacts’, in H. I. H. Prince Takahito Mikasa (ed.), Essays on Ancient Anatolia and its Surrounding Civilizations, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 89–114.

- Ibrahim, M. M., 1972. ‘Archaeological Excavations at Sahab’, ADAJ 17, 23–36.

- Jansen, M., 2011. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Cu-Isotopie in der Archäometallurgie des Kupfers (unpublished masters thesis), Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

- Kassianidou, V., 2001. ‘Cypriot Copper to Sardinia: Yet Another Case of Bringing Coals to Newcastle?’, in L. Bonfante and V. Karageorghis (eds), Italy in Cyprus in Antiquity: 1500–450 bc: Proceedings of an International Symposium held at the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America at Columbia University, November 16–18, 2000, Nicosia: The Costakis and Leto Severis Foundation, 97–119.

- Kiderlen, M., et al., 2016. ‘Tripod Cauldrons Produced at Olympia Give Evidence for Trade with Copper from Faynan (Jordan) to South West Greece, c. 950–750 bce’, JAS: Reports 8, 303–13.

- Kleiman, S., Kleiman, A., and Ben-Yosef, E., 2017. ‘Metalworkers’ Material Culture in the Early Iron Age Levant: The Ceramic Assemblage from Site 34 (Slaves’ Hill) in the Timna Valley’, TelAviv 44, 232–64.

- Laemmel, S., 2003. A Case Study of the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age Cemeteries of Tell el-Far'ah South (Unpublished doctoral thesis), University of Oxford.

- Lassen, H., 2000. ‘Introduction to Weight Systems in the Bronze Age East Mediterranean: The Case of Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios’, in C. F. E. Pare (ed.), Metals Make the World Go Round: The Supply and Circulation of Metals in Bronze Age Europe: Proceedings of a Conference Held at the University of Birmingham in June 1997, Oxford: Oxbow Books, 233–46.

- Lee, S., Bronk Ramsey, C., and Mazar, A., 2013. ‘Iron Age Chronology in Israel: Results from Modeling with a Trapezoidal Bayesian Framework’, Radiocarbon 55, 731–40.

- Levy, T. E., et al., 2008. ‘High-Precision Radiocarbon Dating and Historical Biblical Archaeology in Southern Jordan’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, 16460–5.

- Levy, T. E., Najjar, M., and Ben-Yosef, E., 2014. New Insights into the Iron Age Archaeology of Edom, Southern Jordan, Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

- Master, D. and Aja, A., 2017. ‘The Philistine Cemtery of Ashkelon,' BASOR 377, 135–59.

- Mazar, A., 2016. ‘Culture, Identity and Politics Relating to Tel Reḥov in the 10th–9th Centuries bce’, in O. Sergi, M. Oeming, and I. de Hulster (eds), In Search of Aram and Israel: Politics, Culture and Identity, Orientalische Religionen in der Antike 20, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 89–119.

- Mazar, A., 2019. ‘Weaving in Iron Age – Tel Reḥov and the Jordan Valley’, Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 7, 119–38.

- Mazar, A., 2020. ‘The Tel Reḥov Excavations: Overview and Synthesis’, in A. Mazar and N. Panitz-Cohen, Tel Reḥov: A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley Vol. 1, Introductions, Synthesis and Excavations on the Upper Mound, Qedem 59, Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Mazar, A. and Panitz-Cohen, N., 2020. ‘The Apiary,’ in A. Mazar and N. Panitz-Cohen (eds), Tel Reḥov: A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley, Vol. II, The Lower Mound and the Apiary, Qedem 60, Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Merkel, J. F., 1986. ‘Ancient Smelting and Casting of Copper for “Oxhide” Ingots,’ in M. Balmuth (ed.), Studies in Sardinian Archaeology, Vol. II: Sardinia in the Mediterranean, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Namdar, D., et al., 2017. ‘Absorbed Organic Residues in a Late Bronze Age II Clay Coffin with Anthropoid Lid from Tel Shadud, Israel’, JAS: Reports 12, 726–33.

- Paine, C., 1859. Tent and Harem: Notes of an Oriental Trip, New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- Parker Pearson, M., 1993. ‘The Powerful Dead: Archaeological Relationship between the Living and Dead’, CAJ 3, 203–29.

- Parker Pearson, M., 1999. The Archaeology of Death and Burial, College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

- Pernicka, E., 2014. ‘Provenance Determination of Archaeological Metal Objects,’ in B. W. Roberts and C.P. Thornton (eds), Archaeometallurgy in Global Perspective: Methods and Syntheses, New York: Springer New York, 239–68.

- Philip, G., Clogg, P. W. and Dungworth, D., 2003. ‘Copper Metallurgy in the Jordan Valley from the Third to the First Millennia bc: Chemical, Metallographic and Lead Isotope Analyses of Artefacts from Pella’, Levant 35, 71–100.

- Platt, E. E. 1992. ‘Jewelry, Ancient Israelite’, in D. N. Freedman (ed.), The Anchor Bible Dictionary, Vol. 3, New York: Doubleday, 823–34.

- Raban, A., 1977. ‘Tel Shaddud’, Hadashot Arkheologiyot 61, 13–14.

- Pritchard, J.B., 1980. The Cemetery of Tell es-Sa’idiyeh, Jordan, University Monograph 41, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

- Renzi, M. et al., 2016. ‘Early Iron Age Metal Circulation in the Arabian Peninsula: The Oasis of Taymāʾ as Part of a Dynamic Network (Poster), Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 46, 237–46.

- Rose, T., Fabian, P. and Goren, Y., 2023. ‘The (In)visibility of Lost Wax Casting Moulds in the Archaeological Record: Observations from an Archaeological Experiment’, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 15, 31.

- Rowan, H.D., 1990. ‘Inventory of Graves Excavated 1989', in J.N. Tubb (ed), Preliminary Report on the Fourth Season of Excavations at Tell es-Sa’idiyeh in the Jordan Valley, Vol. 22, 38–42.

- Schulze, M. and Lehmann, R., 2014. ‘Model für Wachsfiguren und Bronzen im Museum August Kestner, Hannover’, in M. Fitzenreiter, C. E. Loeben, D. Raue, and U. Wallenstein (eds), Gegossene Götter, Metallhandwerk und Massenproduktion im alten Ägypten, Rahden/Westf.: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH, 133–54.

- Seeliger, T. C., et al., 1985. ‘Archaeometallurgische Untersuchungen in Nord- und Ostanatolien’, JRGZM 32, 597–659.

- Segal, I. et al., 2015. ‘Provenance of Ancient Metallurgical Artifacts: Implications of New Pb Isotope Data from Timna’, in A. Hauptmann and D. Modarressi-Tehrani (eds), Archaeometallurgy in Europe III, Bochum: Deutsches Bergbau-Museum, 221–7.

- Shamir, O., 1996. ‘Loomweights and Whorls’, in D. T. Ariel, Excavations at the City of David 1978-85, Directed by Y. Shiloh IV, Qedem 35, Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 135–70.

- Spiciarich, A., et al. 2023. ‘Strategies of Animal Exploitation in Late Iron Age IIA Ḥorvat Ṭevet (the Jezreel Valley) Reveal Patterns of Royal Economy in Early Monarchic Israel’, PEQ, 21 March 2023 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.108000310328.2023.2184088?src= [accessed 26 June 2023].

- Stern, E. and Beit Arieh, I., 1973. ‘Excavations at Tel Kedesh (Tell Abu Qudeis)’, in Y. Aharoni (ed.), Excavations and Studies: Essays in Honour of Professor Shemuel Yeivin, Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University / Carta, 93–124 (Hebrew).

- Stern, E. and Beit Arieh, I., 1979. ‘Excavations at Tel Kedesh (Tell Abu Qudeis)’, TelAviv 6, 1–25.

- Stos-Gale, Z. A., 2006. ‘Provenance of Metals from Tel Jatt Based on their Lead Isotope Analyses’, in M. Artzy, The Jatt Metal Hoard in Northern Canaanite/Phoenician and Cypriot Context, Cuadernos de Arqueología Mediterránea 14, Barcelona: Publicaciones del Laboratorio de Arqueología Universidad Pompeu Fabra de Barcelona, 115–20.

- Sergi, O., et al. 2021. ‘Ḥorvat Tevet in the Jezreel Valley: A Royal Israelite Estate’, in K. Covello-Paran, A. Ehrlich and R. Beeri (eds), New Studies in the Archaeology of Northern Israel, Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 31*–48*.

- Singer-Avitz, L., 2016. ‘Khirbet Qeiyafa: Late Iron Age I in Spite of It All — Once Again,’ IEJ 66, 232–44.

- Sukenik, E. L., 1948. ‘Archaeological Investigations at ‘Affula’, JPOS 21, 1–79.

- Toffolo, M. B. et al. 2022. ‘The Absolute Chronology of Megiddo, Israel, in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages: High-Resolution Radiocarbon Dating’, in I. Finkelstein and M. A. S. Martin (eds), Megiddo VI: The 2010–2014 Seasons, Vol. III, University Park / Tel Aviv: Eisenbrauns / Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology of the Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, 1418–37.

- Tubb, J. N. and Rowan, D. 1988. ‘Inventory of Graves Excavated 1985–1987’, in J. N. Tubb, ‘Tell es-Sa’idiyeh: Preliminary Report on the First Three Seasons of Renewed Excavations’, Levant 20, 73–80.

- Tufnell, O., 1930. ‘Burials in Cemeteries 100 and 200', in W.M.F. Petrie (eds), Beth-Pelet I (Tell Fara), Publications of the Egyptian Research Account and British School of Archaeology in Egypt XLVIII, London: British School of Archaeology, 11–13.

- Tufnell, O., 1958. ‘Anklets in Western Asia’, Bulletin of the Institute of Archaeology 1, 37–54.

- Vaelske, V., Bode, M. and El-Morr, Z., 2019. ‘Early Iron Age Copper Trails: The Case of Phoenicia. First Results of a Pilot Study’, Bulletin d'archéologie et d'architecture libanaises 19, 267–79.

- Vaelske, V., Bode, M. and Loeben, C. E., 2019. ‘Early Iron Age Copper Trail between Wadi Arabah and Egypt during the 21st Dynasty: First Results from Tanis, Ca. 1000BC’, Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie 12, 184–203.

- van den Brink, E. C. M et al., 2017. ‘A Late Bronze Age II Clay Coffin from Tel Shaddud in the Central Jezreel Valley, Israel: Context and Historical Implications’, Levant 49, 105–35.

- Van Lokeren, S., 2000. ‘Experimental Reconstruction of the Casting of Copper “Oxhide Ingots”’, Antiquity 74, 275–6.

- Verduci, J. A., 2018. Metal Jewellery of the Southern Levant and its Western Neighbours: Cross-Cultural Influences in the Early Iron Age Eastern Mediterranean, Ancient Near Eastern Studies Supplement 53, Leuven / Paris / Bristol: Peeters.

- Verduci, J. A., 2021. ‘Adornment Practices in the Ancient Near East and the Question of Embodied Boundary Maintenance’, in K. Neumann and A. Thomason (eds), The Routledge Handbook of the Senses in the Ancient Near East, Oxford / New York: Routledge, 127–40.

- Wagner, G. A., et al., 1986. ‘Geochemische und isotopische charakteristika früher rohstoffquellen für kupfer, blei, silber und gold in der Türkei’, JRGZM 33, 723–52.

- Wagner, G. A. et al., 1985. ‘Geologische Untersuchungen zur Frühen Metallurgie in NW-Anatolien’, Bulletin of the Mineral Research and Exploration Institute of Turkey 101, 45–81.

- Wagner, G. A., et al., 1989. ‘Archäeometallurgische Untersuchungen an Rohstoffquellen des Fürhen Kupfers Ostanatolien’, JRGZM 36, 637–86.

- Weitzel, J., 2021. Early Iron Burial Practices in Light of the Cemetery of Ḥorvat Tevet (unpublished masters thesis), Tel Aviv University.

- Weitzel, J., et al., 2024. ‘The Early Iron Age Cemetery of Ḥorvat Tevet: Life and Death in a Rural Community in the Jezreel Valley’, AJA 128, 145–66.

- Yahalom-Mack, N., et al., 2014. ‘New Insights into Levantine Copper Trade: Analysis of Ingots from the Bronze and Iron Ages in Israel‘, JAS 45, 159–77.

- Yahalom-Mack, N. and Segal, I., 2009. ‘Provenancing Copper-Based Objects Using Lead Isotope Analysis’, in N. Panitz-Cohen and A. Mazar, Excavations at Tel Beth-Shean 1989-1996: The 13th–11th century bce Strata in Areas N and S, Vol. III, Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 589–96.

- Yahalom-Mack, N. and Segal, I., 2018. ‘The Origin of the Copper Used in Canaan During the Late Bronze-Iron Age Transition’, in E. Ben-Yosef (ed.), Mining for Ancient Copper: Essays in Honor of Beno Rothenberg, Tel Aviv University Monograph Series 37, Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, 313–31.

- Yahalom-Mack, N., and Segal, I., 2020. ‘Chemical and Lead Isotope Analysis of Copper-Based and Lead Artifacts’, in A. Mazar and N. Panitz-Cohen (eds), Tel Reḥov-A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley, Vol. V, Qedem 63, Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem 41–51.

- Yahalom-Mack, N., Finn, D. M., and Erel, Y., 2023. ‘Assessing the Circulation of Arabah Copper (Timna vs. Faynan) from the End of the Late Bronze and Iron Age in the Southern Levant by Combining Lead Isotopic Ratios with Lead Concentrations’, in E. Ben-Yosef and I. W. N. Jones (eds), “And in Length of Days Understanding” (Job 12:12): Essays on Archaeology in the Eastern Mediterranean and Beyond in Honor of Thomas E. Levy, Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology, Cham: Springer, 1181–99.

- Yagel, O., Ben-Yosef, E. and Craddock, P., 2016. ‘Late Bronze Age Copper Production in Timna: New Evidence from Site 3’, Levant 48, 33–51.

- Yannai, E., 2011. ‘An Early Iron Age Cist Grave at Kibbutz Ha-Zore'a’, ‘Atiqot 65, 47–51, 66* (Hebrew with English abstract).

- Zarzecki-Peleg, A., 2016. Yadin’s Expedition to Megiddo: Final Report of the Archaeological Excavations (1960, 1966, 1967 and 1971/2 Seasons), Text, Qedem 56, Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.