ABSTRACT

This article focuses on parents’ construction of and emotions in their everyday lives. The study brings into focus the meanings in the foreground of everyday life, while also revealing new insights into cultural beliefs and prejudices. Interviews were conducted with five nuclear and four divorced families, and each participant (N = 18) was interviewed twice. The second interview was a photo-narrative interview, for which each participant took photographs pertaining to their daily life. Content and thematic analysis were applied to the data. Three main categories of everyday life emerged from the data: family daily life, couples’ daily life, and one’s own daily life. The importance of and pleasure derived from one’s own daily life were emphasized as the foundation of well-being for both the individual and the whole family.

1. Introduction

Everyday life consists of humdrum “day-to-day” practices, along with the multiple rhythms, emotions, and actions of daily existence. Daily routines, connected with departures, arrivals, reunions, and transitions, take place in specific locations (Bennett & Watson, Citation2002; Felski, Citation2000; Rönkä & Korvela, Citation2009). Everyday life seems to be “blindingly obvious,” so self-evident that it can be hard to see it at all. However, it is not something that should be taken for granted (Miller & Woodward, Citation2012, pp. 84, 155). While everyday life comprises traditions and routines, it is also continuously in process. It lies in-between the private and public domains where domestic duties, work, and travel are situated (Bennett & Watson, Citation2002; Felski, Citation2000). It varies, for example, by time of day and size of family (Felski, Citation2000; Rönkä, Laitinen, & Malinen, Citation2009).

Contemporary everyday family life is a joint venture involving contradictions, complexities, and ambiguities linked to parents’ everyday lives with children (Silberschmidt Viala, Citation2011). The ups and downs of daily family life—fluctuations in stressors, demands, and social and emotional experiences—affect the well-being of all its members (Repetti, Wang, & Saxbe, Citation2011). Therefore, in everyday life each family member—child or adult—exhibits different kinds of agency in his or her actions, emotions, and speech. Here, we focus on the emotions of parents.

The research topic concerns the everyday life of parents. We addressed two specific questions: (1) What kinds of experience and their meanings do parents report in their daily lives? (2) What kinds of emotion do parents describe in their daily lives?

2. Parenthood and Everyday Life in Finland

One-third of the families in Finland consist of a married couple with a mean of 1.84 children below 18 years of age (OSF, Citation2015). For most people of working age, everyday life is essentially framed by paid employment and family life. Work and family are linked to individual values and notions that change along with prevailing social conditions (Hoser, Citation2012). In Finland, it is increasingly common for the parents of young children to work. For Finnish women, independent economic status and having one’s own financial resources are cultural norms. Both parents tend to work full time and, apart from taking family leave when they have young children, to remain continuously in the labor force up to the age of retirement (Jalovaara & Miettinen, Citation2013). Women’s employment rates are almost as high as those of men (OSF, Citation2014) and family policies like parental leave and the provision of childcare help women to combine paid work and childbearing.

In the Nordic countries, both parents are expected to take part in their children’s everyday lives, such as caring for them and helping them with their homework (Forsberg, Citation2009a, p. 17). This is described by the concept of “shared parenthood,” which stresses equality in the division of parental responsibilities (Evertsson, Citation2014; Vuori, Citation2009). Although men in Finland and the other Nordic countries have increasingly accepted that it is their responsibility to be involved in childcare (e.g., Lappegård, Citation2008; Miettinen & Rotkirch, Citation2011), their responsibility for household duties has not increased to the same extent (Bonke & Esping-Andersen, Citation2011; Kan, Sullivan, & Gershuny, Citation2011; Sevón, Citation2012). Fathers continue to be at greater liberty to decide the terms of their engagement and participation, take parental leave less often, and work significantly more hours outside the home than mothers. Nevertheless, we can consider Finnish men overall to be relatively engaged and involved fathers (Eerola & Mykkänen, Citation2015).

Today’s Finnish families with children describe their everyday life as busy, routinized, repetitive, and cyclic. According to quantitative studies of time use in Finnish families, the majority of mothers and fathers working full time outside the home experience lack of time and would like more time to spend with their children as well as on physical exercise, reading, and artistic hobbies (Miettinen & Rotkirch, Citation2011; Pääkkönen, Citation2010). Previous studies have shown that parents may experience conflicting feelings and feel enslaved by duties and routines both at home and at work (Brannen, Citation2005; Forsberg, Citation2009b; Hochschild, Citation1997). Parents of small children may often wonder how they can find more time for themselves, their marriage and their children, and their hobbies (Korvela, Citation2003; Kyrönlampi-Kylmänen & Määttä, Citation2012; Rönkä et al., Citation2009). Employed parents, especially mothers, often complain that heavy workloads create severe time pressures (Mattingly & Blanchi, Citation2003) that prevent them from spending sufficient time with their children (Milkie, Mattingly, Nomaguchi, Bianchi, & Robinson, Citation2004) and that they feel rushed (Bianchi & Wight, Citation2010; Gunnarsdottir, Petzold, & Povlsen, Citation2014; Miettinen & Rotkirch, Citation2011). The emergence of the involved fathering and intensive mothering norms over recent decades has further intensified feelings among parents that, regardless of the amount of time devoted to children, it is never sufficient (Coltrane, Citation1996; Hays, Citation1996; Mattingly & Sayer, Citation2006). This may have something to do with the intensive mothering ideology, which includes the normative prescription that mothers should spend as much “quality time” as possible with their children (Hays, Citation1996; Offer, Citation2016).

On the one hand, it has been argued that parenting has intensified over the last few decades, meaning that it has become more child-centered and labor-intensive (Hays, Citation1996). This intensive parenting ideology includes the notion that shared “family time” is important (Craig & Mullan, Citation2012). As a result, parents are increasingly including children in their leisure pursuits (Bianchi, Robinson, & Milkie, Citation2006), one of the perceived benefits of which is that it promotes family bonding and increases the sense of togetherness (Ashbourne & Daly, Citation2010; Craig & Mullan, Citation2012). On the other hand, family life has been seen to be at the core of the debate on individualization. The key argument of the individualization thesis concerns the increase in individual choice (Oinonen, Citation2013; Smart, Citation2007). The individualization thesis claims that in western societies traditional social structures and institutions have lost much of their influence on the individual’s life. Consequently, individuals have more freedom, or agency, in choosing how to live their lives (Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, Citation1995; Beck-Gernsheim, Citation2002; Giddens, Citation1991). However, it has been argued that this leaves individuals to construct their own biographies. To create the kind of identities and lives individuals want, they have first to accumulate the requisite resources and competences themselves (Beck, Citation1992).

3. Emotions in Everyday Life

In recent years, emotions have become a dominant theme in the human sciences. Some scholars have talked about an emotional or affective turn, meaning an increased emphasis and focus on affect and emotions both in the social sciences and more broadly in societal development (Gónzales, Citation2013, p. 1; Greco & Stenner, Citation2008, pp. 2–6). Emotions are both cultural artefacts and significantly subjective. Emotions are also a vehicle for relational subjectivity, which interprets cultural means. In this study, emotions are approached from a social constructionist viewpoint, where discourse does not merely describe reality but is a constitutive part of it (Barbalet, Citation2008, p. 109; Gónzales, Citation2013, p. 2; Greco & Stenner, Citation2008, p. 8). According to Hárre (Citation1986), this means that emotional talk is regarded as constitutive of emotional experience rather than simply a reflection of it.

Emotions are culture-bound and every culture has its own codes and rules related to them. Cultural values vary from one society to another, and in each culture people are expected to follow certain “feeling rules,” meaning rules prescribing what we should feel in a given situation (Hochschild, Citation1979, Citation1983). Emotions are also greatly gendered: both men and women draw on the culturally available model of emotion as a phenomenon that needs to be controlled. Talk about the control of emotions is evidence of a broadly shared cultural view of the danger of emotions—that they constitute a threat to order, that they are too wild and irrational. Emotions considered to be unhealthy are viewed as experienced, and shown, in particular by women (Lutz, Citation2008, pp. 63–66). It has also been documented that men suppress their emotions more than women, have greater experience of negative emotions, and tend to display more anger-related emotions than women. The norms of masculinity are one reason explaining these types of behavior; for example, suppressing their emotions might be one way in which men try to avoid being rejected on the basis of being unable to “take it like a man” (Brody, Citation1993; Flynn, Hollenstein, & Mackey, Citation2010).

Emotions in family and daily life are important because they tend to spread to other members of the family and influence the collective family atmosphere. The emotional work that family members do in recognizing each other’s needs and taking responsibility for each other is critical for a smooth-running everyday life (Daly, Citation2003; Larson, Citation2005). Although everyday life is filled with emotions in constant flux from positive to negative and vice versa (Rönkä et al., Citation2009), emotions have been relatively little studied empirically and systematically (Kleres, Citation2011).

In this article, the objective was to find out what forms of, and perspectives on, daily family life are revealed to us in photographs and interviews, and how individuals in the same family experience and attribute meanings to their everyday lives. We focus primarily on parents’ views of their daily life, with special interest in the emotions they experience.

4. Method

4.1 Data

This article is based on our research project “Narrated and photographed everyday family life,” which aimed to show everyday family life from the point of view of the children, father, and mother in the same family. The data set consists of photographs and photo-narrative interviews (see Kaplan, Lewis, & Mumba, Citation2007; Rose, Citation2012) with nine Finnish families: 9 mothers (age 28–49), 9 fathers (age 37–52) and 14 children (age 4–15), and 238 photographs taken by parents and 114 taken by children (see ).

Table 1. Participants.

Each participant was interviewed twice, making a total of 64 interviews: 36 with parents and 28 with children. Here, we focus on parents’ experiences and emotions. The only criterion for participation in the research was having a child below age 15 in the family. The present authors interviewed most of the family members, but two families (two parents and two children) were interviewed by a master’s student, who received instruction and training from the authors. The first two participating families, who were not personally known to us, were recruited through our own contacts, i.e., friends and acquaintances, while a small snowball effect (Patton, Citation2015) brought in the other families. Two prospective families refused to participate in the study, one owing to the timing of the research and the other to the imminence of their divorce proceedings and unwillingness to share their life with the researchers. In two further families, the parents refused to allow their children to be interviewed, and hence we interviewed only the parents. Parents varied in length of education, from secondary school to university. Participants included one male and one female student, one housewife and one stay-at-home father, while the remainder of the parents were in paid employment. Participants’ occupations varied from non-managerial (e.g., postman) to managerial (e.g., service manager), and from artistic (e.g., actor) to academic (e.g., researcher). One family came from a rural area and the others from a middle-sized town. The average number of children in the 9 families was 2.3. Five families were nuclear and three were divorced, and in one family divorce was currently in process. In the divorced families, the children mainly lived with each parent alternately: every other week and weekend with their father or mother. Eleven parents had a house of their own and seven lived in rented accommodation (). All the interviews with parents were conducted in their homes.

The photo-narrative (also called photovoice) method has the advantage of giving informants a voice, which means that they are seen as active agents, providing data in their own right (Einarsdóttir, Citation2005; Foster-Fishman, Nowell, Deacon, Nievar, & McCann, Citation2005; Kaplan, Citation2008). Participants are invited to answer research questions by looking at photographs they have taken and explaining them to the researcher. The photographs document aspects of everyday family life. Clearly, the photographs and the narratives told about them are only one segment of a more complex picture: they are not an absolute representation of a given state, but instead a tool to aid understanding while being aware that “the whole of anything is never told” (Punch, Citation2002; Rose, Citation2012).

Photographs are often inspiring and help informants to reflect on and think more deeply and in greater detail about their lives. The photo-narrative method enables interviewees to choose issues that they feel represent their own views and experiences. Photography as a research tool is also a quick, easy, and useful way to obtain different family members’ perspectives on their lives (Guell & Ogilvie, Citation2015; Wang & Burris, Citation1997).

In the first interview, we and the informants spent time getting to know each other, and gaining relevant background information (e.g., age, education, hobbies). We also made the first informed consent request. We then asked some questions about daily life, such as: “What do you think daily life consists of?” “Can you define it?” “Please tell me about yesterday; what was it like?” “Was it usual/unusual?” “Why?” “Describe what emotions you felt yesterday?” and “Why and where did you feel those emotions?” The aim was to map the family, people, places, daily routines, and feelings—and at the same time get to know each other.

At the end of the first interview, we gave the informants disposable cameras. Those who so preferred could also use their own mobile phones. During the same research weeks, each family member took photographs of things, situations, people, feelings, or objects connected to their everyday family life. The family were allowed 1–2 weeks to take the photographs. Loose instructions were given, such as: “You can take photos of places, things, and times in your everyday life that are ordinary, special, or important. You can photograph your and others’ doings and moments when you feel (strong) emotions.” One father and three children declined to take any photographs; instead, they talked about their important daily moments and emotions without visual aids.

After the week(s) of photographing, we collected the disposable cameras or the photographs that had been sent to us. Before the second interview, we copied the photographs and made one set for ourselves and one for the informants. At the beginning of the second interview, we spread all the photographs on the floor or on a table and viewed them as a whole. The interviewees were then asked to choose five that they felt were the most important for them and to talk about each one: “Why did you choose this photo?” “What does this photo reveal about you/about your daily life?” “Where are you, what is the situation, and who are the people in this photo?” At the end of the interview, we asked them to consider if there was anything missing from the photographs and, if they could take photographs again, where they would take them. All informants were interviewed separately and, when the interview data was transcribed, each participant was assigned a pseudonym. Care was taken in the transcriptions to preserve the anonymity of the participants.

Participation was voluntary and participants were free to withdraw at any time (Wiles et al., Citation2008). Informed consent was freely given (on two occasions by each informant), and was also updated during the research process, especially where photographs were concerned. The researchers went through every photograph selected by the informant, who made the decision to allow or not allow use of the photograph in question (Böök & Mykkänen, Citation2014; Mykkänen & Böök, Citation2013). Throughout the research process, we treated informants’ consent as an ongoing process and open to review at all times (Einarsdóttir, Citation2007). As the data were gathered following the signed consent of both parents and children, and the study did not expose the subjects to risk or mental harm, an ethical review was not required (National Advisory Board on Research Ethics Helsinki, Citation2009).

4.2 Analysis

In this article, we focus on the interviews with parents, first to gain an overall impression of their daily family lives and, second, to assist our understanding of the emotions they feel in their daily family life. Our chosen method was qualitative content analysis, which is based on systematic examination of the data (Krippendorff, Citation2004) and thus enables the researcher to get “close to the data and to the surface of words” (Sandelowski, Citation2000). First, we extracted all the definitions, descriptions, and meanings of daily life and content-analyzed them (see Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). We were especially interested in all the “thick descriptions” (Geertz, Citation1973) that revealed the meaning of the parents’ everyday lives. The coding of the interview data was performed inductively and openly, and driven by similarities and differences in the meaningful moments and contexts in the parents’ speech. After coding, the categories were grouped under higher-order headings. Besides the textual analysis, we also coded the photographs (N = 238) under the same codes to capture a visual picture of the data and to ascertain whether the photographs were “in line” with the categories we found in the interviews. All the coding was performed first by the researchers separately and then discussed together to obtain the overall classification. The categories identified by the researchers were generally rather similar, and the few disparities that existed were discussed until a consensus was reached. This kind of research triangulation increases the validity of the study (Patton, Citation2015).

Second, we focused on the emotions experienced and narrated by the parents. Tinkler (Citation2013, pp. 11–13) states that photographs help people to understand and interpret their daily life experiences and the emotiveness within them. This was also the case in the present interviews, where the participants’ photographs were mostly used as a tool to capture detailed experiences and emotions. Emotions are known to be difficult to track, and as Daly (Citation2003, p. 775) says: “They often involve wild swings or expressions that are inconsistent with other attitudes and behavior.” To identify emotions in the data, we focused first on words and sentences directly related to emotional states, like “tired” or “I felt really angry” (Kleres, Citation2011). Then, we extracted sentences that indicated “wild swings” in emotions, even if no words directly descriptive of emotions were present—for example, “I felt trapped in a corner.” The analysis proceeded inductively; in other words, the analysis was not theory-directed (Patton, Citation2015).

The study has several limitations. Because we used snowball sampling, the interviewed parents can be viewed as mainly representative of middle-class Finnish families, which may also be reflected in the interview data (Offer, Citation2016; Tubbs, Roy, & Burton, Citation2005). For example, the sample contained no low-income families or families with financial or mental health problems; that is, families whose lack of material and cultural resources may cause their daily life to be differently constructed.

Narrative and visual approaches have much to offer in eliciting hidden and taken-for-granted aspects of family life. However, it should be borne in mind that photographs can idealize family life, that is, they can represent people in ways in which they would like themselves and their families to be seen (Phoenix & Brannen, Citation2014). Cultural ideological conventions can also bias informants’ stories, such as only showing happiness in the family (White, Bushin, Carpelan-Méndez, & Ni Laoire, Citation2010; see also Harrison, Citation2004). In assessing the credibility of the photographs and the narratives accompanying them, it was important to consider how much performativity and normality the respondents wanted to display. Guell and Ogilvie (Citation2015), however, argue that respondents not only produce the photographs, but are also able to give thick and rich descriptions of their daily lives such that, as in the present instance, the photo-narrative is more than just a “Kodak-moment.” However, while our analysis did not aim to authenticate our participants’ experiences, the possibility of partiality in their narratives as a result of the research method was taken into account (ibid).

5. Findings

5.1 Everyday Life: Definitions and Categories

Parents saw their daily life as “ordinary life,” filled with people important to them, emotions, doings, and responsibilities. Over half of the pictures featured people, most of them family members. There were also many pets in the photographs. Everyday objects, such as dishwashers, vacuum cleaners, dirty laundry, shoes, etc., and technology and social media (television, telephones, and computers) were often photographed. Family members were pictured as active mothers, fathers, and children—cooking, cleaning, playing, going for a walk, or engaged in a hobby. Gendered roles were visible in the photographs taken by the parents: mothers were mostly shown cooking and doing household duties, while fathers were playing with children, sitting in front of a computer, or watching television.

When asked about missing photographs, parents explained that the most emotional moments, like kissing, hugging, or quarreling, had not been included. Moreover, locations such as parents’ bedrooms or the sauna, so beloved of Finns, were seldom photographed. Missing moments or places can be interpreted as intimate spaces framed by individual and cultural codes that restrict photographing. For example, one mother explained how it didn’t enter her mind to photograph moments during a quarrel.

Daily life in the interview data seemed to involve timetables and routines both inside and outside the home; these, at best, can create feelings of safety. Everyday life was also typically described by means of binary oppositions such as, “Sometimes it’s lively; other times it’s deadly boring” (Mother, age 48). However, these unsurprising days were also interpreted as points which root people in time and give meaning to life. Another participant described it thus: “Everyday life, it grounds you in your life—it’s an earth conductor” (Mother, age 48).

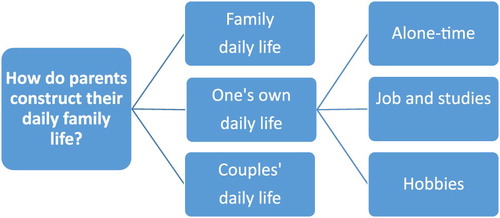

The interview data analysis yielded three broad categories of daily life from the perspective of parents (see ): (1) family daily life, (2) couples’ daily life, and (3) one’s own daily life. All three categories consisted of pleasurable and burdensome elements and were related to each other. The “size” and meaning of the category varied according to the day, week, month, or year. In other words, these three categories of everyday life are context-bound. After coding, we examined the photographs in light of these categories: the photographs revealed that 68% of the pictures pertained to “family daily life” (children, domestic duties, and doing things together, such as eating meals, 3% to “couples’ daily life” (e.g., two coffee cups or the couple watching television together), and 29% to “one’s own daily life” (e.g., using a laptop, doing yoga).

In the next excerpt, a father expresses amazement when looking at the photographs he has taken. Everyday life seemed to be something more than and different to what he thought it was in the first interview. The research process opened his eyes to the various elements and dimensions of everyday life; that, although you live in a family as a family member, you are also an individual with your own interests and occupations.

Last time we met I somehow emphasized that everyday life is like doing things together, but now, during this week I somehow noticed it’s not so much about doing things together (with the family) all the time. It’s also doing things by yourself, and everyone has their own affairs. Being together is a bit much at certain moments. Mornings are pretty busy and being together exists in moments like sauna and having meals, supper. Everyday life does consist of repeated things, but it isn’t necessarily so much about being and doing together as I thought. (Father, age 39)

Family life also consisted of many obligations, such as taking care of a child’s needs and doing household chores. How and by whom these things were done varied. For example, one mother described how she prepared dinner together with her children, whereas another preferred to cook alone and leave the children to play. Overall, the parents’ goal was to build a fluid and functional daily life, supporting family cohesion.

In general, the interviews with parents in the nuclear families revealed shared parental roles: both mothers and fathers took care of the children and did household duties. However, the interviews showed that mothers were mainly the primary organizers at home. One mother (age 41) described it thus: “Daily life starts in the morning when as a housewife you delegate daily chores to others. … In coping with daily life, I like to maintain a balance and keep an eye on everything.” Most parents constructed a picture of a responsible mother, one who takes care of the childcare arrangements, timetables meals, and allots turns at washing dishes and hoovering. All in all, she takes care of the “big picture,” while the father helps and does “his share.”

While divorced mothers’ experiences and feelings about “family daily life” resembled those of nuclear family mothers, this was not the case in the fathers’ narratives. Divorced fathers emphasized the importance, intensiveness, and positiveness of the time they spent with their children, even if they were also exhausted at the same time. For example, one father (39 years) told how every day he felt “happy because he had the best two children in the world” and how picking up the children and being with them was the highlight of his week. Another father (38 years) instead reflected on how, despite the anxiety caused by the divorce, he was spending more time with his children than before. “We have now more closeness than ever,” he stated

Couples’ daily life refers here to time spent alone with one’s spouse. This was often a shared moment or doing that empowers the mother or father as a spouse, such as going to the movies or for a walk, shopping, having romantic moments, or just watching television. One father (age 43) expressed how important it was that “we got to go for a walk, just the two of us.” Couples’ daily life reproduces and strengthens the position of a spouse.

One’s own daily life refers to a time or moment of one’s own that is free from family duties and bestows a feeling of autonomy: you can do what you want. When describing their personal daily life, parents constructed themselves as individuals rather than as family members. Parents’ own daily life was further categorized into three sub-categories: (1) alone-time, (2) job and studies, and (3) hobbies.

Various emotions, from positive to negative, were attached to the three main categories mentioned above: for example, tiredness and satisfaction arising from the performance of daily family routines and responsibilities; happiness and tension in the couple’s daily life (as a couple); and feelings of energy, enjoyment, and loneliness in one’s own daily life. Next, we examine the emotions of mothers and fathers in the context of their own daily life.

5.2 Emotions in Parents’ Own Daily Life

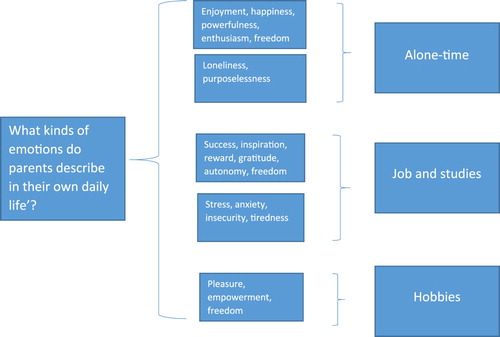

The emotions identified in parents’ own daily lives were contextualized into the three sub-categories described above: alone-time, job and studies, and hobbies (). One-third of the emotions reported were negative, e.g., tiredness, distress, disappointment, feeling rushed, and loneliness. However, the other two-thirds were positive, e.g., happiness, joy, freedom, gratitude, enjoyment of beauty, excitement, empowerment, and peacefulness. One emotion that united all three categories was the feeling of freedom.

5.3 Precious Alone-time

One’s own daily life was often described as a time when the parent distanced him or herself from the other family members and was alone. “Alone-time” can be, but is not necessarily, spontaneous time, as everyday family matters must usually be organized beforehand to make such time even possible. Alone-time differs from, e.g., hobbies in that it is time without regularities or arranged actions. Often this time or moment occurred in the evening, when the children were already in bed. Sometimes alone-time time was only possible early in the morning:

I can be alone and read the paper peacefully before anyone else wakes up. I get so irritable if Kimmo [my husband] for example wakes up at the same time and comes to mess up my system. It’s always been really important to me to be alone in the mornings, I can read the paper and drink coffee and be there just all alone. That’s really important. (Mother, 46 years)

[After the divorce] I’m happy and feeling better, already mentally. And also physically because you can rest in other ways. Every other weekend, that’s time for me. And the children are away one evening every week so there’s also a few hours which give you much. Although I don’t spend that time sleeping, I can recharge my batteries in other ways. I think that is the thing which has made me a better mother. (Mother, 35 years)

Loneliness haunts me. It’s hard to wait for the future, because there isn’t anything to wait for. I’ve had the family, and now it’s gone, and I don’t have that kind of dream any more. I sometimes come close to tears. I miss them. (Father, 38 years)

5.4 Interesting Job and Studies

Because almost every parent was working or studying outside the home, having a job or studying seemed to be an essential part of a successful personal daily life. It gave the parent a break from family demands and the chance to focus on something independently, of one’s “own”; as one mother (33 years) put it, “My spouse or child can’t limit me then.” It seems easier to put family obligations aside elsewhere than at home. One’s job more often than one’s home was seen as inspiring and demanding, and success at work bestowed a sense of self-competence. Many parents also seemed to have a strict work ethic. When days are burdensome and tiring and you are coming and going “all in a rush, it’s your duty to do your work as well as possible, then you feel rewarded” (Father, 38 years). Interestingly, creative work, for example as a writer or actor, especially aroused positive emotions of gratitude, freedom, and autonomy, as it could be done without having to take the needs of other family members into account. Being together with colleagues also brought a sense of relatedness and community:

I like my job and it’s really lovely to get to meet my colleagues instead of working from home and doing constant housekeeping; there’s a sense of community which is a welcome change in my week. I can sit and have coffee with my colleagues and chat. (Mother, age 48)

5.5 Indulgence of Hobbies

Like alone-time, job and studying, hobbies were another area of personal daily life in which mothers and fathers could escape from their parenting role by participating in an activity outside the home. Hobbies were seen as a domain where you could empower yourself by enjoying esthetic or physical pleasures or by “spoiling” yourself. This category differed from job and studies in that the individual trains or develops her or his physical and/or mental health in some way but is not obliged to do specific tasks in the same way as when at work or studying:

That kind of physical exercise is like your own. It’s become an indulgence even if it’s sweaty and needs effort, at the same time it’s a moment when you pamper yourself; it’s really pleasurable. (Father, 39 years)

Interestingly, guilt was seldom explicitly mentioned when parents talked about spending time on their hobbies. It seems that today’s parents allow themselves to take time out.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

This study focused on constructions of and emotions in the daily family life of parents. It seemed that daily life unified many different places, objects, things, pets, and people, and that home was the center of daily family life. The parents saw their daily life as divided between three domains: family daily life, couples’ daily life, and one’s own daily life. Family daily life consisted of interaction and closeness with family members and emotions ranging from happiness to anger. Having children obliged parents to adopt a routinized and ordered everyday life (Forsberg, Citation2009a, 28), which, in turn, brought security and continuity. Parents seemed to be highly inclined to live up to the dominant cultural and social expectations, to the norms and practices that make for good, involved parents who enjoy a “normal,” healthy, and smooth family and social life (Forsberg, Citation2009a, p. 17; Hoser, Citation2012). Couples’ daily life was seldom photographed, but instead talked about. Although parents emphasized the importance of spending time with their spouse, this was time that it was easiest to skip or postpone. Parents may feel that children come first or it may be that couple time is not so highly valued culturally as family time or own time. To find couple time, parents have to make a conscious effort to negotiate how they spend it, to organize the family schedule, and to obtain good childcare. In contrast, at its best, “own time” is spontaneous and unscheduled time (Dyck & Daly, Citation2006).

We were especially interested in the category one’s own daily life, as its importance was highlighted by the interviewees. Having time to oneself included, for example, work outside the home, hobbies or just a peaceful moment alone, such as an unrushed coffee break. It seems that parents choose times for being apart and for being together that meet their individual needs (Ashbourne & Daly, Citation2010). The motive for having time of one’s own was the feeling of freedom it gave; one could choose what to do and feel certain of not being interrupted. In practice, parents valued their own time so much that to gain it they were prepared to sacrifice sleep or time spent as a couple. This aspect of one’s own daily life gave parents “fuel,” the strength to cope with the daily hassles and repetitiveness of family life.

Research has shown (e.g., Bialeschki, Citation1994; Shaw, Citation2008) that mothers are more likely than fathers to put off their personal leisure until their children are older and more independent. Most of our informants had school-aged children and thus probably already had more opportunity to enjoy personal leisure than, for example, the mothers of toddlers. Ashbourne and Daly (Citation2010) also found that, as their children grow older, parents begin to experience more autonomy with respect to time. The socioeconomic status of the present sample of parents was stable, which further facilitated having time to oneself. However, a limitation of our study is that we had no single parents as informants whose daily life and own time may be differently constructed from that of couples.

Contrary to earlier studies (e.g., Deutsch, Citation1999; Milkie et al., Citation2004; Miller & Brown, Citation2005), the mothers and fathers interviewed here did not mention feelings of guilt when talking about taking time out for themselves. One possible explanation is the small sample size. However, the shared parenthood or egalitarian parental relationships that are more common today make it easier for mothers and fathers to focus on their own interests and needs. The parents in this data argued that they had earned their time out and that this also benefited the children. At the same time, spending time outside the home and family allows mothers and fathers to take a break from the “pressures of good mothering or fathering” (Offer, Citation2016).

In this study, work and colleagues also framed parents’ own daily life. Ensuring economic security, the need for self-development, the company of other adults in the workplace, and the maintenance of one’s professional skills all supported parenthood (Rönkä et al., Citation2009). As Hochschild (Citation1997) has argued, work gives people a sense of fulfillment, of being capable, and of enjoyment in what they do. In this sample, signs of disparities between parents were observed; for example, mothers seem to enjoy their paid work more than fathers, while fathers more often mentioned feeling tired after their working day.

The data also indicated the prevalence of traditional gender-based practices and responsibilities. Moreover, there appeared to be a “cultural lag” between the economic realities of modern life (e.g., women’s employment) and traditional gender ideologies (Hochschild & Machung, Citation1989; Röhler & Huinink, Citation2010). The role of mothers as coordinators and foremen, delegating housework and making sure that everything works, was emphasized. The mother was the one who kept the larger picture of the family in mind (see also Dyck & Daly, Citation2006).

The parental discourses of daily family life arise in specific sociohistorical contexts and thus reflect, and are constrained by, societal views and ideologies concerning everyday family life (Shaw & Dawson, Citation2001). Shaw (Citation2008) also argues that parents are clearly in the role of recipients of media messages about good parenting behavior. At the same time, parental practices and the diverse patterns of daily life also contribute to ideas and beliefs about fatherhood and motherhood. In this study, the parents’ narratives about their daily life can be seen as reflecting current ideologies about families and parenthood. The individualistic “wellness culture” of present-day society may also impose demands on parents, who then try to do their best for the family by looking after their own well-being: a good parent is a parent who has good physical and mental well-being and who is allowed, more than in previous generations, to talk about his or her own needs and aspirations. Generating individual and collective well-being in everyday family life seems to be the joint “business” of the different family members.

The individualistic thesis argues that people no longer adhere to a pre-determined identity. They have more freedom to choose among the many lifestyles currently on offer (Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, Citation2002; May, Citation2011). People also have more freedom to choose what they consume and these choices form a basis for identity construction (Bauman, Citation1990). The emphasis laid by the present parents on the importance of having a daily life of one’s own may be informed by this “consumerist ethos.” However, we should be skeptical of the view that people are free to choose which lifestyle-groups (e.g., “fitness parents”) to belong to. Warde (Citation1994), for example, argues that social class continues to play an important part in identity, even in consumer culture (Southerton, Citation2011).

Emotions are usually seen as gender-bound (Lutz, Citation2008), and therefore we can assume that the parents in this study also have learnt which emotions are acceptable and which are not. However, a change seems to have taken place in men’s emotional openness concerning fatherhood (Mykkänen, Citation2010). If women and mothers have traditionally been labeled emotional, it seems that fathers are also rapidly reaching this point. Here, both parents equally named and narrated positive and negative emotions, although gender differences were evident in the narratives of the divorced, but not nuclear, parents. Whereas divorced mothers felt empowered and enjoyed their own daily life, divorced fathers more often reported feelings of loneliness and being lost. It has been documented that divorce is consistently and negatively associated with men’s psychological well-being (Shapiro & Lambert, Citation1999). One reason for this may be that fathers report being more socially isolated than mothers, suggesting that they receive less social support than mothers (Skreden et al., Citation2012). Nevertheless, the divorced fathers in this study reported enjoying a more emotionally intense relationship with their children following their divorce, and thus experienced being a “better father” (see also Cohen-Israeli & Remennick, Citation2015). In sum, divorce can in some cases produce new kinds of parenting or parenting practices, whereby mothers gain more time of their own and fathers more time with their children.

This study enhances our understanding of parents’ emotions pertaining to having a daily life of one’s own and the daily practices of motherhood and fatherhood. Family cohesion was constructed during daily family life, which seemed to be framed by work. Working part time could perhaps reduce time pressure and create more possibilities for parents to spend time with their children. Just as it is important to spend time together as a family, so it is also important to support parents and organize childcare so that parents can have time of their own—and time together. Well-being and positive emotions experienced by parents ripple out to their children and promote the well-being of the whole family.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Finnish Cultural Foundation.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ashbourne, L. M., & Daly, K. J. (2010). Parents and adolescents making time choices: “Choosing a relationship”. Journal of Family Issues, 31(11), 1419–1441. doi: 10.1177/0192513X10365303

- Barbalet, J. (2008). Emotion in social life and social theory. In M. Greco & P. Tenner (Eds.), Emotions. A social science reader (pp. 106–111). London: Routledge.

- Bauman, Z. (1990). Thinking sociologically. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Beck, U. (1992). The risk society. Towards a new modernity. London: Sage.

- Beck, U., & Beck-Gernsheim, E. (1995). The normal chaos of life. Cambridge, MA: University Press.

- Beck, U., & Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2002). Individualization. London: Sage.

- Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2002). Reinventing the family. In search of new lifestyles. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

- Bennett, T., & Watson, D. (2002). Understanding everyday life: Introduction. In T. Bennett & D. Watson (Eds.), Understanding everyday life (pp. ix–xxiv). Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Bialeschki, M. D. (1994). Re-entering leisure: Transition from the role of motherhood. Journal of Leisure Research, 26(1), 57–74.

- Bianchi, S., Robinson, J., & Milkie, M. (2006). Changing rhythms of American family life. New York, NY: Russel Sage.

- Bianchi, S. M., & Wight, V. R. (2010). The long reach of the job: Employment and time for family life. In K. Christensen & B. Schneider (Eds.), Workplace flexibility: Realigning 20th-century jobs for 21st-century workforce (pp. 17–42). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Bonke, J., & Esping-Andersen, G. (2011). Family investments in children: Productivities, preferences and parental childcare. European Sociological Review, 27(1), 43–55. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcp054

- Böök, M. L., & Mykkänen, J. (2014). Photo-narrative processes with children and young people. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 5(4.1), 611–628. doi:http://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs.bookml.5412014

- Brannen, J. (2005). Time and the negotiation of work-family boundaries: Autonomy or illusion? Time and Society, 14(1), 113–131. doi: 10.1177/0961463X05050299

- Brody, L. R. (1993). On understanding gender differences in the expression of emotion: Gender roles, socialization, and language. In S. L. Ablon, D. Brown, E. J. Khantzian, & J. E. Mack (Eds.), Human feelings: Explorations in affect development and meaning (pp. 87–122). Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Cohen-Israeli, L., & Remennick, L. (2015). “As a divorcee, I Am a better father”: Work and parenting among divorced Men in Israel. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 56(7), 535–550. doi: 10.1080/10502556.2015.1080083

- Coltrane, S. (1996). Family man: Fatherhood, housework and gender equity. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Craig, L., & Mullan, K. (2012). Shared parent-child leisure time in four countries. Leisure Studies, 31(2), 211–229. doi: 10.1080/02614367.2011.573570

- Daly, K. (2003). Family theory versus the theories the families live by. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(3), 771–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00771.x

- Deutsch, F. M. (1999). Having it all: How equally shared parenting works. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Dyck, V., & Daly, K. (2006). Rising to challenge: Father’s role in the negotiation of couple time. Leisure Studies, 25(2), 201–217. doi: 10.1080/02614360500418589

- Eerola, P., & Mykkänen, J. (2015). Paternal masculinities in early fatherhood: Dominant and counter narratives by Finnish first-time fathers. Journal of Family Issues, 36(12), 1674–1701. doi: 10.1177/0192513X13505566

- Einarsdóttir, J. (2005). Playschool in pictures: Children’s photographs as a research method. Early Child Development and Care, 175(6), 523–541. doi: 10.1080/03004430500131320

- Einarsdóttir, J. (2007). Research with children: Methodological and ethical challenges. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 15(21), 197–211. doi: 10.1080/13502930701321477

- Evertsson, M. (2014). Gender ideology and the sharing of housework and child care in Sweden. Journal of Family Issues, 35(7), 927–949. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14522239

- Felski, R. (2000). The invention of everyday life. New Formations, 39, 13–31.

- Flynn, J. J., Hollenstein, T., & Mackey, A. (2010). The effect of suppressing and not accepting emotions on depressive symptoms: Is suppression different for men and women? Personality and Individual Differences, 49(6), 582–586. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.022

- Forsberg, L. (2009a). Involved parenthood. Everyday Lives of Swedish Middle-Class Families. Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 473. Linköping: Linköping University, Department of Child Studies.

- Forsberg, L. (2009b). Managing time and childcare in dual-earner families: Unforeseen consequences of household strategies. Acta Sociologica, 52(2), 162–175. doi: 10.1177/0001699309104003

- Foster-Fishman, P., Nowell, B., Deacon, Z., Nievar, M., & McCann, P. (2005). Using methods that matter: The impact of reflection, dialogue and voice. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 8(2), 175–192. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8626-y

- Geertz, C. (1973). Thick descriptions: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

- Gónzales, A. M. (2013). The emotions and cultural analysis. London and New York: Routledge.

- Greco, M., & Stenner, P. (2008). Introduction: Emotion and social science. In M. Greco & P. Stenner (Eds.), Emotions. A social science reader (pp. 1–22). London: Routledge.

- Guell, C., & Ogilvie, D. (2015). Picturing commuting: Photovoice and seeking well-being in everyday travel. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 201–218. doi: 10.1177/1468794112468472

- Gunnarsdottir, H., Petzold, M., & Povlsen, L. (2014). Time pressure among parents in the Nordic countries: A population-based cross-sectional study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 42, 137–145. doi: 10.1177/1403494813510984

- Hárre, R. (1986). The social construction of emotions. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Harrison, B. (2004). Snap happy: Toward a sociology of “every” day photography. In C. Pole (Ed.), Seeing this believing? Approaches to visual research (pp. 23–40). Oxford: Elsevier.

- Hays, S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. New Haven, CT: Yale, University Press.

- Hochschild, A. (1983). The managed heart. Commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hochschild, A. (1997). The time bind: When work becomes home and home becomes work. New York, NY: Owl Books, Henry Holt and Company.

- Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion, work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85(3), 551–575.

- Hochschild, A., & Machung, A. (1989). The second shift: Working families and the revolution at home. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

- Hoser, N. (2012). Making it as a dual-career family in Germany: Exploring what couples think and do in everyday life. Marriage & Family Review, 48(7), 643–666. doi: 10.1080/01494929.2012.691085

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

- Jalovaara, M., & Miettinen, A. (2013). Does his paycheck also matter? The socioeconomic resources of co-residential partners and entry into parenthood in Finland. Demographic Research, 28(31), 881–916. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2013.28.31

- Kan, M. Y., Sullivan, O., & Gershuny, J. (2011). Gender convergence in domestic work: Discerning the effects of interactional and institutional barriers from largescale data. Sociology, 45(2), 234–251. doi: 10.1177/0038038510394014

- Kaplan, I. (2008). Being “seen”, being “heard”: Engaging with students on the margins of education through participatory photography. In P. Thomson (Ed.), Doing visual research with children and young people (pp. 175–191). London: Routledge.

- Kaplan, I., Lewis, I., & Mumba, P. (2007). Picturing global educational inclusion? Looking and thinking across students’ photographs from the UK, Zambia and Indonesia. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 7(1), 23–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2007.00078.x

- Kleres, J. (2011). Emotions and narrative analysis: A methodological approach. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 41(2), 182–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5914.2010.00451.x

- Korvela, P. (2003). Yhdessä ja erikseen. Perheenjäsenten kotona olemisen ja tekemisen dynamiikka [Together and separately. The dynamics of the family members being and doing at home]. Tutkimuksia/Stakes=Research reports/National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health 130.

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Kyrönlampi-Kylmänen, T., & Määttä, A. (2012). Children’s and parent’s experiences of everyday life and the home/work balance in Finland. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 1, 46–64. http://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs31201210473

- Lappegård, T. (2008). Changing the gender balance in caring: Fatherhood and the division of parental leave in Norway. Population Research and Policy Review, 27, 139–159.

- Larson, R. W. (2005). Commentary. In B. Schneider & L. J. Waite (Eds.), Being together, working apart. Dual-career families and the work-life balance (pp. 159–163). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Lutz, C. (2008). Engendered emotions. In M. Greco & P. Stenner (Eds.), Emotions. A social science reader (pp. 63–71). London: Routledge.

- Mattingly, M. J., & Blanchi, S. M. (2003). Gender differences in the quantity and quality of free time: The U.S. Experience. Social Forces, 81(3), 999–1030. doi: 10.1353/sof.2003.0036

- Mattingly, M. J., & Sayer, L. C. (2006). Under pressure: Gender differences in the relationship between free time and feeling rushed. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(1), 205–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00242.x

- May, V. (2011). Introducing a sociology of personal life. In V. May (Ed.), Sociology of personal life (pp. 1–10). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Miettinen, A., & Rotkirch, A. (2011). Yhteistä aikaa etsimässä. Lapsiperheiden ajankäyttö 2000 -luvulla. Perhebarometri. Time use of families with children on 2000. Searching for shared time. The Annual Family Barometer]. Väestöntutkimuslaitos. Katsauksia E 42/2012 [Population Research Institute].

- Milkie, M. A., Mattingly, M. J., Nomaguchi, K. M., Bianchi, S. M., & Robinson, J. P. (2004). The time squeeze: Parental statuses and feelings about time with children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(3), 739–761. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00050.x

- Miller, Y. D., & Brown, W. J. (2005). Determinants of active leisure for women with young children—An “ethic of care” prevails. Leisure Sciences, 27(5), 405–420. doi: 10.1080/01490400500227308

- Miller, D., & Woodward, S. (2012). Blue jeans: The art of the ordinary. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Mykkänen, J. (2010). Isäksi tulon tarinat, tunteet ja toimijuus [Becoming a father—Types of narrative, emotions and agency]. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Mykkänen, J., & Böök, M. L. (2013). Photographing as a research method – Finnish children’s views of everyday life. In E. Oinonen & K. Repo (Eds.), Women, men and children in families. Private troubles and public issues (pp. 169–194). Tampere: Tampere University Press.

- National Advisory Board on Research Ethics Helsinki. (2009). Ethical principles of research in the humanities and social and behavioural sciences and proposals for ethical review. Retrieved from http://www.tenk.fi/sites/tenk.fi/files/ethicalprinciples.pdf

- Offer, S. (2016). Free time and emotional well-being: Do dual-earner mothers and fathers differ? Gender & Society, 30(2), 213–239. doi: 10.1177/089124321559642

- Oinonen, E. (2013). Relatedness of private troubles and public issues. In E. Oinonen & K. Repo (Eds.), Women, men and children in families. Private troubles and public issues (pp. 9–26). Tampere: Tampere University Press.

- OSF. (2014). Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Labour force survey [e-publication]. ISSN=1798-7857. Employment and unemployment 2014. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 15.6.2016]. Access method. Retrieved from http://www.stat.fi/til/tyti/2014/13/tyti_2014_13_2015-04-28_tie_001_en.html

- OSF. (2015). Official Statistics of Finland: Families [e-publication]. ISSN=1798-3231. Annual review 2015, 1. Average number of family members is 2.8 persons. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 25.1.2017].

- Pääkkönen, H. (2010). Perheiden aika ja ajankäyttö. Tutkimuksia kokonaistyöajasta, vapaaehtoistyöstä, lapsista ja kiireestä [The time and time use of families. Studies about total workload, voluntary work, children and time pressure.] Tilastokeskus Tutkimuksia 254 [Statistics Finland. Research Reports 254].

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Phoenix, A., & Brannen, J. (2014). Researching family practices in everyday life: Methodological reflections from two studies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 17(1), 11–26. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2014.854001

- Punch, S. (2002). Research with children: The same or different from research with adults? Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark), 9(3), 321–341. doi: 10.1177/0907568202009003005

- Repetti, R. L., Wang, S.-W., & Saxbe, D. E. (2011). Adult health in the context of everyday family life. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 42(3), 285–293. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9293-x

- Röhler, A., & Huinink, J. (2010). Pair relationships and housework. In J. Treas & S. Drobnic (Eds.), Studies in social inequality: Dividing the domestic: Men, women, and household work in cross-national perspective (pp. 192–213). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Rönkä, A., & Korvela, P. (2009). Everyday family life: Dimensions, approaches and current challenges. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 1(2), 87–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2009.00011

- Rönkä, A., Laitinen, K., & Malinen, K. (2009). Miltä arki tuntuu? In A. Rönkä, K. Malinen, & T. Lämsä (Eds.), Perhe-elämän paletti. Vanhempana ja puolisona vaihtelevassa arjessa [The palette of family life. Being a parent and a spouse in everyday life] (pp. 203–221). Jyväskylä: PS-Kustannus.

- Rose, G. (2012). Visual methodologies. An introduction to researching with visual materials. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health, 23(4), 334–340.

- Sevón, E. (2012). “My life has changed, but his life hasn’t”: Making sense of the gendering of parenthood during the transition to motherhood. Feminism & Psychology, 22(1), 60–80. doi: 10.1177/0959353511415076

- Shapiro, A., & Lambert, J. D. (1999). Longitudinal effects of divorce on the quality of the father-child relationship and on fathers’ psychological well-being. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(2), 397–408.

- Shaw, S. M. (2008). Family leisure and changing ideologies of parenthood. Sociology Compass, 2(2), 688–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00076.x

- Shaw, S. M., & Dawson, D. (2001). Purposive leisure: Examining parental discourses on family activities. Leisure Sciences, 23(4), 217–231. doi: 10.1080/01490400152809098

- Silberschmidt Viala, E. (2011). Contemporary family life: A joint venture with contradictions. Nordic Psychology, 63(2), 68–87. doi: 10.1027/1901-2276/a000033

- Skreden, M., Skari, H., Malt, U. F., Pripp, A. H., Björk, M. E., Faugli, A., & Emblem, R. (2012). Parenting stress and emotional wellbeing in mothers and fathers of preschool children. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(7), 596–604. doi: 10.1177/1403494812460347

- Smart, C. (2007). Personal life. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

- Southerton, D. (2011). Consumer culture and personal life. In V. May (Ed.), Sociology of personal life (pp. 134–146). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Tinkler, P. (2013). Using photographs in social and historical research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Tubbs, C. Y., Roy, K. M., & Burton, L. M. (2005). Family ties: Constructing family time in Low-income families. Family Process, 44(1), 77–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00043.x

- Vuori, J. (2009). Men’s choices and masculine duties: Fathers in expert discussions. Men and Masculinities, 12(1), 45–72.

- Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309

- Warde, A. (1994). Consumption, identity-formation and uncertainty. Sociology, 28(4), 877–898. doi: 10.1177/0038038594028004005

- White, A., Bushin, N., Carpelan-Méndez, F., & Ni Laoire, C. (2010). Using visual methodologies to explore contemporary Irish childhoods. Qualitative Research, 10, 143–158. doi: 10.1177/1468794109356735

- Wiles, R., Prosser, J., Bagnoli, A., Claske, A., Davies, K., Hollande, S., & Renold, E. (2008). Visual ethics: Ethical issues in visual research. ECRC National Center for Research Method Review paper. NCRM/011. Retrieved from http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/421/1/MethodsReviewpaperNCRM-011.pdf