ABSTRACT

Understanding how children experience life in educational settings should be an imperative for educational practitioners, evaluators, and researchers. Listening to children’s points of views would facilitate the development of educational settings that meet the needs of children and contribute to their wellbeing and development so that their experiences are both joyful and meaningful. A total of 56 children between the ages of 5 and 7 in 65 educational settings located in central Sweden were included in the study. Amongst the 56 participating children, 29 were identified as having special educational needs. The children’s views were collected from 2012 to 2015 using drawings and interviews, and these were analysed using a thematic analysis. Nine themes that reflected matters of importance for the children, both those with and without special educational needs, are described. These themes are discussed and linked to previous research, educational evaluation models, and theories of values and needs.

Introduction

In this study, we investigate the views of young children (ages 5–7) with and without special educational needs in the context of early inclusive and special education in Sweden on their early school life and describe matters that they consider important for their wellbeing and development. Attention is given to what the children say that they value (i.e., like, think is good) and need in their early educational experiences. We discuss and link children’s views of matters of great importance for their wellbeing and development to previous research, educational evaluation models and tools, and theories of values and needs.

Children’s Right to Share Their Opinions and to be Listened to

Children, both those with and without special educational needs, have the right to share their opinions about their everyday life in preschool and school, and to be listened to and be respected (United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [UN CRC], Citation1989, article 12–13; United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [UN CRPD], Citation2006, article 7). Children can be understood to be experts on their own lives, and to have important things to say about their education to teachers, researchers, and evaluators (Aronsson, Hedegaard, Højholt, & Ulvik, Citation2012; Clark & Moss, Citation2011; Lundqvist, Citation2014; Mason & Danby, Citation2011). Incorporating children’s views into educational research/evaluations is therefore considered important (Allodi Westling, Citation2002; Clark & Moss, Citation2011; Due, Riggs, & Augoustinos, Citation2014; Kellet, Citation2011; Lundqvist, Citation2014; Qvarsell, Citation2015; Siljehag, Citation2014, Citation2015; Stanek, Citation2014; Tangen, Citation2008; UN CRC, Citation1989; UN CRPD, Citation2006). The children can describe to practitioners, researchers, and evaluators what they value and dislike in early school years, and what they feel worried about. The information gained from children on such matters may facilitate the planning and development of high-quality educational settings that meet the needs of children, that the children find to be joyful and meaningful and that provide them with the optimal conditions for wellbeing and development.

Research and Evaluation Tools

There are a number of studies and evaluation tools that describe the needs of children, suggest optimal conditions for their wellbeing and development, and provide advice on how to develop high-quality educational environments.

For example, Allodi Westling (Citation2002), Einarsdottir (Citation2008, Citation2010), Kragh-Müller and Isbell (Citation2011), and Wiltz and Klein (Citation2001) have investigated the perspectives of children on their education reporting that children need to experience stimulating educational activities, to build friendships, and to play with peers to be able to thrive. Further, children want opportunities to choose what to do (Einarsdottir, Citation2008, Citation2010; Kragh-Müller & Isbell, Citation2011). Conversely, children found to be negative peers’ mean behaviour, unstimulating activities, and lack of autonomy (Einarsdottir, Citation2008, Citation2010; Kragh-Müller & Isbell, Citation2011).

Harms, Clifford, and Cryer (Citation2005, Citation2010) investigated what constitute optimal conditions for children’s wellbeing and development in preschool settings, and reported that children need to have furnishings for relaxation and comfort; spaces for privacy; spaces for gross and fine motor play; lots of equipment to practise their gross and fine motor skills; spaces for block building; sand and water for play; a safe setting; positive and warm interactions with staff and peers; free time; opportunities to explore nature and learn more about culturally relevant topics and subjects – for example, math, reading and writing. These elements have been structured in a descriptive model, the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale - Revised (ECERS-R), which can be used as a tool for the evaluation of early years learning environments.

Soukakou (Citation2012, Citation2016) investigated what constitute optimal conditions for children’s wellbeing and development, with attention given to the adaptations and the support that should be provided in inclusive educational environments, for children with special educational needs. Soukakou’s model, the Inclusive Classroom Profile (ICP), identifies these elements: adaptations of space, materials and equipment; adult involvement in peer interactions; adults’ guidance of children’s free-choice activities and play; conflict resolution; membership; relationships between adults and children; support for communication; adaptation of group activities; transitions between activities; positive and warm feedback; family-professional partnership; and monitoring children’s learning. The ICP can be used as a tool for the evaluation of inclusive early years learning environments (Soukakou, Citation2016; Soukakou, Evangelou, & Holbrooke, Citation2018).

Theoretical Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks of human development, values, and needs describe basic human needs and values, and we apply them to the understanding of children’s experiences: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow, Citation1943), self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Niemiec & Ryan, Citation2009), the bioecological model of human development (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation1998), and Schwartz’s model of universal basic human values (Schwartz, Citation1992, Citation1994, Citation2012).

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow, Citation1943) suggests that children have basic physical needs (e.g., the need to breathe, eat, sleep, rest, and move); safety needs (e.g., having a sense of wellbeing and an everyday life that is void of anxiety and fear); the need to belong and be loved (e.g., friendship and family, feeling appreciated and respected by others); the need for esteem (e.g., to be accepted, respected, and valued); and finally the need for self-actualisation (e.g., the need to reach one’s full potential, to achieve goals, and to feel competent when with others).

Self-determination theory

Self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Niemiec & Ryan, Citation2009) postulates the existence of basic needs that are necessary for healthy development and psychological wellbeing, and increased involvement, motivation and performance: autonomy (e.g., the feeling that you can make choices or decide what to do); competence (e.g., achievement in a number of relevant areas); and relatedness (e.g., interaction with others; sense of belonging to a community; the feeling of being liked and respected by teachers and peers).

Bioecological model of human development

In the bioecological model of human development (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation1998), participation in proximal processes, such as group or solitary play and other activities, are set forth as the primary engines for children’s wellbeing and their emotional, social, moral, and intellectual development.

Universal theory of human values

The universal theory of human values (Schwartz, Citation1992, Citation1994, Citation2012) encompasses 10 motivational types of value that are considered to be fundamental since they reflect basic human needs. The 10 values have been defined as desirable goals that guide human actions and that are structured in a bidirectional structure in which self-enhancement versus self-transcendence are the poles in one direction, while conservation versus openness to change are the poles in the other direction. The basic values are seen as universally shared, but the modalities of application and the relative importance of the values may vary between individuals and across different cultures.

The value model has been tested across various cultural contexts, and modifications have been introduced over time (Cieciuch, Davidov, Schmidt, Algesheimer, & Schwartz, Citation2014; Cieciuch, Davidov, Vecchione, Beierlein, & Schwartz, Citation2014; Schwartz, Citation2017), including with school children (Döring et al., Citation2015). The 10 values included in the picture-based survey for children (Döring et al., Citation2015) are the following: universalism (e.g., appreciating and protecting people and nature, making new friends) and benevolence (e.g., helping others, protecting the welfare of peers) that relate to self-transcendence; tradition (e.g., accepting the customs of a culture, thinking about God), conformity (e.g., observing the rules) and security (e.g., feeling safe and harmonious) that relate to conservation; power (e.g., being rich and powerful, having status and control) and achievement (e.g., being the best, achieving success, demonstrating competence) that relate to self-enhancement; hedonism (e.g., enjoying life, feeling pleasure), stimulation (e.g., doing exciting things and being challenged), and self-direction (e.g., choosing, discovering new things, creating) that relate to openness to change.

Schwartz’s theory of values has been used in previous narrative analysis of children’s values in educational settings (Allodi Westling, Citation2002) and as a framework for a model of goals and values in school (Allodi Westling, Citation2010a, Citation2010b; Allodi Westling, Sundbom, & Yrwing, Citation2015) that has been applied in school interventions.

All these aforementioned theories and models of development, values, and needs are largely compatible, which may result from the fact that they describe basic and fundamental structures of human needs, which are recognisable in different contexts. In this study, we link children’s views of matters of great importance for their wellbeing and development to previous research, educational evaluation models and tools, and theories of values and needs.

Values and Needs

The concepts of values and needs that are used in this study are similar, in the sense that they are used to represent significant experiences of early school years that are necessary for a sense of wellbeing to be achieved and a development to take place. These significant experiences are valued and needed because they are seen as good. There is in this sense an overlap between these concepts, but they can also be viewed as partially distinct. The concept of needs may indirectly suggest the idea that the subject that has needs is quite a passive entity, while the concept of values may suggest the image of a purposeful subject, an agent with preferences and motivations. In order to relate to relevant previous research, early school years educational evaluation tools and applicable theoretical frameworks, we have chosen to adopt the concepts of values and needs, and also to maintain the idea that the views of children can contribute to an understanding of what they value as well of what they need.

Needs and values are abstract concepts that may not be familiar for the children aged 5–7 years. At this age children cannot necessarily distinguish between needs and values. The concepts had to be explained so that all children could understand what we asked about: therefore we asked the children what they liked, what they liked to do, and what they thought was good when they were in their early childhood education. So the children were not explicit and directly asked about their (basic) needs for wellbeing and development in early school years and, instead, the concepts of likes and good things, as well as dislikes were taken on. These concepts were assumed to be easier to understand for a young child, as well as to talk about, describe, and draw. In this study, values (likes and good things) were seen as possible to transform into needs: beneficial experiences in early school years facilitate wellbeing and development, and therefore these can be understood as needs of children.

The contents of their answers were interpreted as trustworthy and reliable indications of valuable experiences, activities and situations for them, since children already at very early ages show understanding of moral situations and are capable of identifying bad and good experiences (Clark & Moss, Citation2011; Hamlin, Citation2014; Hamlin & Wynn, Citation2011).

Diversity in Experience and the Swedish Early School Years

When collecting children’s views on early school years, it is important to consider the experiences of children with various abilities (Allodi Westling, Citation2002; Lundqvist, Citation2014). Children who have special educational needs or a disability, in inclusive or segregated programmes, should have the opportunity to take part in research and evaluations, so that it is not only the experiences of the majority population (e.g., children who do not have special educational needs or a disability) that are reflected in research. Children who have special educational needs can have many similar experiences compared with children without such special needs, but they can also have different experiences compared with their peers. The children’s unique views on early school years therefore might be expected to contribute to enriched, pluralistic, and non-reductive views of educational, or, more generally speaking, of human experiences (Allodi Westling, Citation2002; Lundqvist, Citation2014; Wendell, Citation1996).

In Sweden, early school years should be tailored and adapted to the needs of every child, in order to support them in their participation and learning, and to compensate for disadvantages as well as social inequities (Education Act, Citation2010: 800). Additional support should also be obtained when needed. This would make it possible to create educational provisions that are not only accessible, but also truly inclusive and beneficial in terms of wellbeing and development. However, if the resources and conditions in the educational environment are not sufficient and if the educators do not offer high-quality education, then it is likely that children would be affected by these shortcomings in their education. Several studies have shown that disabled children risk, for example, to experience less participation (Eriksson, Welander, & Granlund, Citation2007; Imms et al., Citation2017) and that there are variations in terms of quality between Swedish preschool educational settings (Lundqvist, Allodi Westling, & Siljehag, Citation2016). Recent evaluations from the Swedish School Inspectorate confirm that the provisions to children with special educational needs in preschool need to be strengthened and developed in many locations, even though there are some good examples (Swedish School Inspectorate, Citation2016, Citation2018).

Aim

The aim of this study is to investigate the views of children, both those with and those without special educational needs, on their early school years life (e.g., preschools, preschool-classes, leisure-time centres, and first-grade classes). A further aim is to describe matters that children consider important for their wellbeing and development. The questions posed are the following: What are, according to the children, the important elements for their wellbeing and development in early school years? Which themes can be identified in the responses of the children with regards to what they report is good for them in their early year education, mirroring their values and needs? In which ways do these themes relate to educational evaluation tools and theoretical models of human development, values, and needs?

Methods

Study and Participants

This study is part of another inclusive and special education oriented study (Lundqvist, Citation2016) that took place from 2012 to 2015, in which children were followed from their final year in preschool to first grade. A longitudinal design (Taris, Citation2000) during the data collection and a qualitative approach (Creswell, Citation2013) were adopted. The first collection of data took place in the preschool units from November 2012 to March 2013, the second in preschool-classes and leisure-time centres in March and April 2014, and the third in first-grade classes and leisure-time centres from November 2014 to February 2015.

The eight preschools at which the study commenced were selected strategically with the aim of achieving variation between the settings and the children enrolled. After preschool, the children moved to several preschool-classes, leisure-time centres, and first-grade classes. Information was shared and consent was obtained from the head teachers, teachers, other staff, parents, and the children. The children’s willingness and consent to participate were checked on a regular basis by way of spoken questions and children’s initiatives, body language, and mimicry.

A total of 56 children between the ages of 5 and 7 in 65 educational settings (preschools n = 8, preschool-classes n = 17, leisure-time centres n = 20, and schools n = 20) located in five different Swedish municipalities were visited. Three children dropped out over time. Among the 56 children, 29 had special educational needs, either transient or long-term, and some of these children had a disability diagnosis such as autism, Down syndrome, or a language disorder. Of those 29 children with special educational needs, 5 had an intellectual disability. The information on special educational needs and disability diagnosis of the children was obtained from staff members who knew the children well. In this study, the notion of children with special educational needs refers to children who needed and were provided additional support (e.g., extra help and attention, time visualisations, special equipment, prompting, one-on-one activities, speech therapy, augmentative and alternative communication methods and tools) from staff members in educational activities, routines and/or play in order to be able to take part and learn in the early-years education.

The children attended preschools with an overall quality ranging from low to good, and with a quality of inclusion ranging from low to nearly good (Lundqvist et al., Citation2016). The ECERS-R (Harms et al., Citation2005, Citation2010) and the ICP (Soukakou, Citation2012, Citation2016) were used in these quality assessments. After preschool, the children began attending regular school settings, with the exception of the children who had an intellectual disability (n = 5) who started in segregated programmes (Lundqvist, Citation2016).

The methodology of the study was reviewed and approved in 2012 by a Regional Ethical Review Board (2012/421–31/5). Guidelines and recommendations from the Swedish Research Council (Citation2011) and from previous research (Siljehag, Citation2015; Smith, Citation2011) have been followed.

Data-Collection Methods

The children’s views, both those with and without special educational needs, were collected through the use of drawings. Each time fieldwork was conducted, the children were asked to depict in drawings the activities and objects that they valued (liked and viewed as good) in their preschool, preschool-class, leisure-time centre, and first-grade class. The children were given blank A4 sheets of paper, colouring pencils, and rubbers by the researcher. The children were asked to comment on their drawings to help make an accurate interpretation. A number of children drew more than one drawing, while others included several activities or objects in the same drawing. In total, 198 drawings were collected.

Drawing seemed to be a familiar activity for most children, and it led to them being active. They could think, make changes, and add objects or activities as they drew. However, drawing was challenging for some of the children with special educational needs. In this study, one staff member helped one child by providing ideas of activities and objects that she knew the child liked to do and was fond of, and that the child was able to draw after her prompts. Another staff member took a child onto her knee and held a pen together with the child. Together, they drew the green pedal car that the child liked to ride during outdoor play. There were not always enough support staff to help in such situations; therefore, proxies were used. Adopting proxy-arrangements as a means of broadening children’s participation involves an adult who knows a child well being asked to describe what the child likes to do on the child’s behalf and providing the closest approximation to how the child would answer if he or she could. In this study, the staff members were asked to be proxies in some cases. Seven children had proxy reports. If proxies had not been used in this study, some of the children enrolled would not have been included in the results.

The children’s views, both those with and without special educational needs, were also collected through interviews. The children were individually interviewed on several aspects of their education and were asked to rate their experiences related to these aspects as positive, blended, or negative. In this study, the evaluations concerned the children’s overall satisfaction and experiences with preschool, preschool-class, leisure-time centres, and first-grade class, and their experiences of outdoor play, indoor play, meal and snack times, circle times, and subject lessons (e.g., physical education, music, mathematics, reading, and writing). The semi-structured interviews were conducted in the children’s learning environments. Some interviews were recorded and transcribed, whereas others were written down by the child and researcher on a form during the interview. The interviews were facilitated by Pictogram® illustrations (National Agency for Special Needs Education and Schools, Citation2010). Illustrations of a positive face, a face that the children could interpret as a blended feeling, and a negative face were used. Illustrations of preschools, preschool-classes, leisure-time centres, first-grade classes, outdoor play, indoor play, circle times, and subject lessons were also employed. In total, 135 interviews were conducted.

The pictures of feelings and features made the children feel comfortable in terms of the questions posed, made them feel confident and made it possible for them to share their views without using speech. Sharing views through visualised semi-structured interviews – which imply an understanding of questions and illustrations, and communicating a view – could be challenging for some of the children with special educational needs. Therefore, proxy arrangements were also used in this part of the data collection.

Thematic Analysis

A thematic analysis, following the guidelines of Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), was adopted in the analysis of data. The following steps were taken by the first author: (1) several readings of the interview transcriptions as well as observations of the drawings were conducted; (2) contents of interest in the data that related to the research questions were noted; (3) the contents of the drawings were coded. Several codes were employed such as outdoor, indoor, free play, educational activity, routine, fine motor skill, gross motor skill, with peers, unaccompanied, speed, imagination, creativity, movements, and freedom. For example, a drawing of an outdoor swing in the sun on which the child had written “I like to swing” was coded in the following way: free play, outdoor, swing, movement, warmth, excitement, freedom, and the whole body; (4) the contents of the drawings, by means of the codes, were divided into themes; (5) the content of the interviews was related to the themes that were identified. For the most part, the content of the interviews could be related to the identified themes. However, an additional theme, this one about comforting objects and the children’s home and family, was considered necessary and was consequently added; (6) the themes were assigned headlines so as to reflect values and needs of the children, that is to say positive experiences and matters of great importance for their wellbeing and development. In the process of analysis, the children’s expressions of positive and negative experiences and matters of great importance were interpreted as and translated to needs and values of the children. In this study, the concepts of values and needs were understood as closely related to each other as well as to child wellbeing and development. These headlines were as follows: a sense of belonging with peers; opportunities for play, creative activities, and thinking; experiences of speed, excitement, and physical challenges; elements of cosiness, withdrawal, and comfort for recreation; to feel safe; to experience growth in knowledge and understanding of the world; to feel free and autonomous; and comforting objects and bonds with home and family; (7) a critical examination of the themes was made. Thereafter, the other two authors were involved in the analysis. The second and third authors validated and discussed the thematic analysis with the first author. The themes identified were validated in the discussion, but there were also elements that emerged that were not taken into account sufficiently within the eight preliminary themes. The data was examined again and discussed jointly by the authors. As a result, a ninth theme, this one called connection to nature, was added. The headings of the themes were further discussed by the authors.

Examples of children’s drawings and comments are included in the results in order to augment the trustworthiness of the study.

Results

Themes on Children’s Values and Needs

In the drawings and in the interviews, the children described activities and situations that they valued, such as playing with peers, being at the leisure-time centre, and having subject lessons. In the interviews, they also described dislikes and worries, such as boring circle times, reprimands from teachers, passivity and lonesomeness, the lack of a parent close by, difficult school work, and threats and physical violence that hindered their wellbeing and development.

Nine themes that reflected matters of importance for the children emerged in the analysis of the drawings and of the interviews. In order for the children, including those with special educational needs, to maintain and develop positive experiences of early school years, they described through words and drawings that they valued and needed: (1) to feel a sense of belonging with peers; (2) to have opportunities for play, creative activities, and thinking; and (3) to have experiences of speed, excitement, and physical challenges. They also valued and needed: (4) elements of cosiness, withdrawal, and comfort for recreation; and (5) to feel safe. Moreover, they valued and needed: (6) to experience growth in knowledge and understanding of the world; (7) to feel free and autonomous; (8) to have comforting objects and bonds with home and family; and (9) to have a connection with nature.

A sense of belonging with peers

A central theme in the results is that of sense of belonging with peers, which reflects the pleasure and importance of participating, having friends, and doing activities together with others, and the perceived problems that occur when there were no peers to play with and when children felt lonely.

The children drew drawings of social interactions with peers, which afforded them a sense of belonging, and described with joy in the interviews the pleasure and importance of having peers. When one girl was asked what she liked, she responded: “To play with friends.” A girl with special educational needs said that she liked to attend the preschool-class: “I like to be here. Where I live, in the countryside, I am lonely.” A boy said: “I like preschool because I have nice friends.”

The interviews also revealed that there were children who had experiences of feeling left out in their early school years and who had felt sad because of this. To deal with such isolation, one girl walked in circles. She said: “Good. I get fresh air [in outdoor play]. The thing I don't like is that no one plays with me. I just walk in circles, circles, circles.” On her preschool drawing, an outdoor social activity was illustrated. She said: “To play. I do not play.” Another girl climbed the apple tree to deal with her uncertainty in social outdoor play. She said in the interview: “When it is a little difficult to know what to do, I go and sit in the apple tree.” In her preschool drawing, the apple tree was depicted.

Clearly crucial to their wellbeing in early school years was a sense of belonging. Dislikes arose when they were not able to be with their peers, when they were not eating the same food as their peers, or when the children were angry at each other and got into fights. Despite a sense of belonging with peers being key to children’s sense of wellbeing, not every child feels he or she belongs.

Opportunities for play, creative activities, and thinking

One more theme in the results is opportunities for play, creative activities, and thinking: these reflect the joy and importance for children of working with their hands, creating and playing with beautiful things, using their imagination in play and role-playing, doing artistic activities, and constructing. However, they also highlight the problems that occur when children are supposed to sit still, wait, and be passive.

The children drew drawings of block buildings and artwork showing them using their hands and playing with sand and water, pedal cars, and playhouses, all of which allowed them to think creatively. The joy they experienced with such activities revealed itself in the interviews. For example, one girl said: “I like to sew and I usually do that.” In her preschool-class and leisure-time drawing, she drew a teddy that she had sewn. Another girl, who had special educational needs, said how she liked to play indoors since she could “draw and do such things.” One boy said: “To build. Lego.”

The children who reported blended or negative experiences towards play said that the outdoor playground was worn-out, and that they did not like the toys, which were too few or boring.

Experiences of speed, excitement, and physical challenges

This theme reflects the pleasure of speed, excitement, and physical challenges that the children experience in their early school years, especially in outdoor spaces.

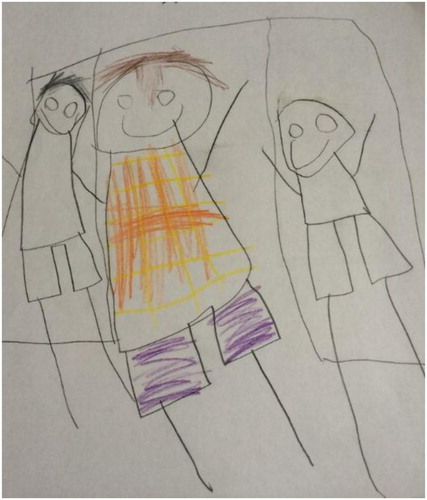

The children drew drawings of slides, bikes, swings (), climbing, and football games, and talked enthusiastically about such activities as well as about discos, sledding, and board games in the interviews. They also drew drawings of play incorporating spying and treasure hunts. They also talked with joy about eating food from other countries. These activities, which often required whole-body engagement, allowed them to feel acceleration, an adrenaline rush, weightlessness, and the wind in their hair, and offered them opportunities to taste new flavours. Many of these activities also allowed them to be loud, to compete, and to improve their gross motor skills.

Figure 1. Experiences of speed, excitement, and physical challenges: “To swing. Me in the middle. My hair.”

A proxy to a boy with special educational needs reported that he liked to ride a pedal car at high speed down the little hill in the preschool playground. The adult and the child drew the pedal car that the boy used to ride during outdoor play. A girl drew a football game and said: “I like football in the recesses and leisure-time centre.” Excitement was something the children related to physical activities, although they sought such excitement in circle times, subject lessons, and free play as well.

In preschool and preschool-class, there were children who were not that fond of circle times since they had to sit still and they found them uninteresting and unexciting. The children also said that the circle time situations could be loud, caused them to worry because of difficulties with speaking, were too long, and involved uncomfortable seating on the floor. One child suggested that it would be better if children could lie down instead of sitting, and another suggested that circle times should be made more interesting.

Elements of cosiness, withdrawal and comfort for recreation

The children did not only have a need for speed, excitement, and challenges, but also expressed a need for elements of cosiness, comfort for recreation, and withdrawal from the larger group of children. Some problems occurred when children were not given such opportunities.

The children drew drawings of soft toys, of little houses in the preschool playground, and of places in forests. Proxies reported that there were children who had special educational needs who liked to rest, to have a bath, to hold a soft toy and to listen to music. The children also produced drawings of spaces to which they could withdraw for play with one or two peers. In one of the interviews, one girl said that she liked to sit and relax on a sofa. Others talked about watching movies and the pleasure of listening to stories and eating fruit, tasty food, candy, popcorn, and ice-cream on particular occasions. One girl said: “Now and then we watch movies.” Another girl drew a drawing of a little house in her school playground and said: “To play in the little house with Emma [a fictive name of peer]. I like that.”

Feeling safe

The theme feeling safe expresses how the children want to feel safe and secure. The children who had experienced threats or physical violence from peers felt distressed. Although they were not many, some talked about physical violence, mentioning kicks, fights with hands, involuntary wrestling, and threats from peers, which had a negative impact on them. One girl said that a peer planned to bring his dad to school to hit her. Feeling safe seemed to be an important and basic need that was not always maintained for every child.

Experience growth in knowledge and understanding of the world

Experiencing growth in knowledge and understanding of the world reflects a pleasure and eagerness on the part of the children to learn to read, write, and do mathematics, and to explore and to understand complex phenomena in the world, such as waste management, the structure of the infinite universe, and life in space.

The children drew drawings of educational activities in which they were reading, writing, working with mathematics books, and working on certain science interests, and in the interviews they talked about how they liked to practise their skills in reading, writing, and mathematics and to have homework. These educational activities allowed them to develop academic skills and problem-solving skills, and to transform them from being simply a child to becoming a child at school – that is to say, a student. The activities also allowed them to reflect upon existential questions, such as one’s place in the world (which can relate to recycling issues or knowledge of the universe), and to expand their knowledge in areas of interest. One girl with special educational needs said: “This I have to learn [to write]. That is good.” Another girl said: “Great fun. I love to read.”

Typically, the children liked the subjects that they were skilled in. Consequently, blended and negative experiences could occur when the subjects were viewed as difficult.

Feeling free and autonomous

Feeling free and autonomous reflects the joy of having recesses and free play. It also seems important for the children to have the opportunity to make their own decisions and choices, and to be allowed to have some autonomy – that is to say, not have staff involved in some activities and situations.

The children drew drawings of their free time and play in small houses and trees that they climbed, and they talked in the interviews about the pleasure of doing what they wanted during playtime and breaks. One girl explained: “More fun than school [the leisure-time centre]. Run. Play. Do just about anything.” Two boys, one of which had special educational needs, said: “Because you are allowed to play freely [at the leisure-time centre].” “You are allowed to play what you want [at the leisure-time centre].” Consequently, there are blended and negative experiences that can be related to children being told what to do in play with peers, the lack of free play, restricted choices, and restrictions when it came to playing with a certain friend.

Comforting objects and bonds with home and family

Another theme is comforting objects and bonds with home and family, which reflects the fact that children, in order to thrive in early school years, need to prevent and deal with their homesickness.

There were children who drew drawings of activities and objects that reminded them of home, such as toys and soft toys, and who in the interviews talked about missing their mothers and fathers, about how they preferred being at home, and about how they longed to go home. One boy said: “I only like it here a little bit. I do not like school that much. I like it better at home. You learn a lot at home as well.” One girl said: “Being at home is better.” One girl who drew a drawing of her soft toys clarified: “These are my soft toys, the horse and the dog [from home].” She also said: “I cannot be at preschool without them.” One more example of this feeling came from a boy who has special educational needs, who explained that it was boring playing in the school playground since he “did not have a mum to play with.”

Connection with nature

The final theme that emerged in the analysis is called connection with nature. This theme reflects the importance of having connections with nature in early school years. The children’s drawings when they were asked about what they liked and enjoyed in the early years education encompassed green grass, yellow suns, blue clouds, skies, big green trees with leaves, branches, and apples, raindrops, stones, forests, sand, snow, rainbows, brown earth, moons and stars, and birds. One girl expressed in words just how much fun she had playing outdoors and climbing in trees, while another said that she liked to be in the woods during breaks. A boy with special educational needs said that he liked to play in the sand, while another boy explained that he liked to make snowmen. The children liked to play outdoors, but there is something more in their accounts and drawings than simply playing in the equipped playground; the children seem to appreciate and value the experience of being and playing in the natural world.

Links to Educational Evaluation Tools and Theoretical Frameworks on Values and Needs

When the children’s opinions on values, needs, and important features in their early school years are compared with the contents of the ECERS-R – the structured observation rating scales designed to measure overall quality – several similarities emerge. The children in this study as well as the rating scale emphasise the value and need for pleasant relationships and interactions, free play, gross motor activities, space for privacy, cosy areas, safety, and opportunities for learning and connections to nature. This means that making an evaluation based on the perspective of children may also say something about the overall quality of an education setting.

When the children’s opinions are compared with the contents of ICP (Soukakou, Citation2012, Citation2016) – the structured observation rating scale designed to examine whether programmes have high-quality inclusive practices – a number of correspondences and a few dissimilarities emerge. The children in this study identify peer relationships and interactions, play, safety, and opportunities for learning as important, and these are also present in ICP. Some elements that are not included or being made explicit in the ICP form are the values and needs for speed and connections with the natural environment.

For the most part, the findings from this study are consistent with the hierarchy of needs theory (Maslow, Citation1943), self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008a, Citation2008b), the concept of proximal processes in the bioecological model (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation1998), and the theory of values (Schwartz, Citation2012).

In , the themes identified in this study with regards to the views of children on their early childhood education relate to the hierarchy of needs theory (Maslow, Citation1943). The children did not draw or talk much about basic physical needs, with the exception of recreation, meal, and snack times. The other needs in Maslow’s theory could be related to several themes based on the views of the children. Safety and security needs could be related to the themes of cosiness and safety, whereas the need to belong and to be loved could be related to the theme of belonging, comforting objects, and bonds with home and family. Esteem could be linked to the theme of freedom and autonomy, and self-actualisation could be linked to the themes of free play, creative activities, speed, excitement, physical challenges, knowledge growth, and understanding of the world.

Table 1. Correspondence between the themes and contents identified in this study and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory (Maslow, Citation1943).

In , the themes relate to self-determination theory. The themes of play, creativity, freedom, autonomy, withdrawal, and nature fit into the domain of autonomy. The themes of belonging, cosiness, safety, and bonds with home, place well within the domain of relatedness, while creative activities and thinking, speed, excitement, challenges, knowledge growth, and understanding the world fit well into the domain of competence. This study thus readily endorses the manifestation of the basic needs described by the self-determination theory, even in young children.

Table 2. Correspondence between the themes and contents identified in this study and the domains of the self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Niemiec & Ryan, Citation2009).

When the children in this study described their values and needs during their early school years, they described various activities with peers and staff members such as educational activities (e.g., subject lessons and reading) and play activities (e.g., indoor and outdoor play with peers, block building, and artwork) that can be understood as being important proximal processes (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation1998), that is to say, primary engines for wellbeing and emotional, social, moral, and intellectual development.

In a possible correspondence between 10 motivational value types (Schwartz, Citation1992, Citation1994, Citation2012) and the content identified in the study is presented. There seems to be a correspondence between the themes and the value types. For instance, theme nine, connection with nature, may be related to universalism and theme one about belonging to benevolence. The theme about bonds with home and family could be related to tradition since it expresses devotion to one’s home and family members, and the value type security through harmony and stability by means of objects from home. Security could also be related to themes four and five. Theme six, growth in knowledge and understanding the world, may be related to power and achievement. Self-direction, linked to the pole openness to change, could be related to play, creative thinking, and activities that are meaningful (theme two) and feeling free and autonomous, for example choosing what to do (theme seven). Stimulation, also linked to the pole openness to change, is related to the theme of speed, excitement, and physical challenges, and hedonism to themes about play with beautiful things and fun toys, creativity, excitement, and comfort for recreation using, for example, music. All the value types, except the value of conformity, could match with themes and elements collected from the views of the children. The themes identified in this study to a large extent support the validity of the content of the motivational theory of values (Schwartz, Citation1992) and provide empirical evidence of these basic human needs in a group of young children.

Table 3. Correspondence between the motivational values types (Döring et al., Citation2015; Schwartz, Citation1992, Citation1994, Citation2012, Citation2017) and contents and themes identified in this study.

Discussion

The nine themes identified in this study may be seen as enhancing the wellbeing of the children, and may facilitate their development. These themes involve social, intellectual, psychological, and motor domains and represent a broad range of domains in the educational life of a child – domains that ought to be acknowledged in educational settings. The children seem to need an inner life satisfaction as well as certain conditions in their surrounding educational environments and both people and objects play a role when it comes to their wellbeing and development.

Play seemed to contribute to a sense of fulfilment in terms of several values and needs, such as belonging; creativity; experiences of speed, excitement, and physical challenges; elements of cosiness, withdrawal, and comfort for recreation; the feeling of freedom and autonomy; and connection with nature. Therefore, play is not isolated to one theme, but links to several.

After at least some form of inclusive education in preschools, the children with an intellectual disability did not follow their peers to regular and inclusive settings. They entered segregated programmes. This seems problematic since belonging with peers is a key feature for wellbeing.

The element of cosiness, withdrawal and comfort for recreation (e.g., resting in a cosy area, holding a soft toy, and listening to music) seems to be especially important for the children enrolled who have a disability and special educational needs, which may help them to enjoy and cope. Lower levels of participation in some group activities would not necessarily always indicate a problem that needs to be solved or a risk. These moments of rest and relaxation may help the children to gain strength for other activities in which they later want to participate. The children who do not have disability/special educational needs also value cosiness, withdrawal, and recreation.

The need for experiences of speed, excitement, and physical challenges, as well as the need for elements of cosiness, withdrawal, and comfort for recreation, could be looked at as being quite opposite. Even the theme of belonging as well as that of withdrawal seems to point in two different directions, as do feeling safe and experiencing physical challenges. This may indicate that the children need variation of experience and a balance in their everyday life. A child may value playing outdoors after circle time or schoolwork, since such outdoor free play involves different experiences that satisfy other needs, and vice versa. According to the theory of values (Döring et al., Citation2015; Schwartz, Citation1992, Citation1994, Citation2012), and other frameworks such as those of Kahn (Citation1997), Kaplan (Citation1995), Kellert and Wilson (Citation2013), Szczepanski (Citation2008), and Harms et al. (Citation2005, Citation2010), experiences with nature can have a positive effect on wellbeing and human development. It is also possible that the children have somewhat different preferences: in this case, some children might value and need more exciting and challenging activities, while other children might value and need more reading, elements of cosiness, and withdrawal. The aim of this study, however, was not to identify the children’s possible different preferences; rather, it was to describe which types of values and needs they seem to have.

The lack in variation and balance between values and needs could hinder the wellbeing and development of a child. Staff in both inclusive and segregated programmes would not only need to ensure that the nine matters of importance are in place, but also need to ensure that there is a balance between the values and needs of each child.

All the value types, except the value of conformity in the theory of human values (Schwartz, Citation1992, Citation1994, Citation2012), could match with themes and elements collected from the views of the children. This result may indicate that it can be difficult for children to draw and tell about the value of conformity (e.g., observing and learning social rules) because this concept could be viewed as more abstract. It may also indicate that conformity is not important to them, or that it is not something that they long for. Another possible interpretation is that this value is not expressed clearly, but it is present in the social rules of the activities in which children participate in the social context of preschool/school. Moreover, the adults may be perceived as taking a great share of responsibility for the value of conformity, because they want the children to follow social rules and adapt to routines.

Understanding how children experience life in educational settings should be a relevant goal to pursue for educational practitioners, evaluators, and researchers. Listening to children and taking them seriously is a key for those adults in their proximity as a means of showing the children respect. This approach of listening and respecting is pivotal in children’s wellbeing and development of their own concepts of equity and fairness, and also in their understanding of what the recognition of others means. In fact, listening and demonstrating respect can be the children’s way of developing a sense of their own self-worth (Qvarsell, Citation2015; Siljehag, Citation2015). A child should not be walking in circles during outdoor playtime and should not be without friends; nor should a child experience threatening behaviour. The fact this was the case for a few children in this study is a concern. The children should have the opportunity to enjoy and be provided with adequate support provisions from staff members in such circumstances.

The child who walked in circles and the child who experienced threatening behaviour were not described as being children with special educational needs by staff. One explanation for this situation could be that lonesomeness and inadequate safety are not considered to represent a need for extra support in the same way that disabilities or difficulties in learning and behaviour do. If this is the case, then staff would need to expand their understanding of the notion of special educational needs to also include those children who feel lonely and unsafe. Another explanation could be that the staff were not aware of these disempowering experiences and therefore did not see the need to provide support so that the children would feel a sense of belonging and safety.

To deal with loneliness, one girl walked in circles and another girl climbed an apple tree. These two activities could be seen as coping strategies as well as strategies for appearing busy so that nobody would notice their lack of companionship. It is important to keep in mind that a child may feel lonely even if he or she appears occupied. The teachers would have to observe interaction and play in order to detect similar situations of low participation or exclusion that may at times not be evident. It would be appropriate for staff to plan, implement and evaluate interventions to increase meaningful social interplay between the children.

Listening to children’s points of views allows for their values and needs to be taken into account, and may contribute to the design of evaluation tools, practices, and research that enable all children to receive an equitable education, therefore increasing their participation in meaningful activities in social situations in ways that contribute to their wellbeing and happiness. The views of all children, regardless of ability and experience, are worth considering since they may give a broad range picture of their educational experiences.

The involvement of children with diverse abilities and experiences in this study can be seen as a strength when it is compared with studies that do not report these views; however, the study does have limitations. One is that the number of children that participated was limited; additional values and needs in terms of wellbeing and development may have been observed if a larger number of children, with an even greater variety of abilities and experiences, had participated. The study, therefore, does not claim to provide a complete and comprehensive picture of children’s likes, values, and needs, and the results should not be generalised. However, the many links and similarities between the empirical evidence of this study, educational evaluation tools, and existing theoretical frameworks on development, values, and needs seem to support the validity of these tools and theoretical frameworks as well as the external validity of this study.

The main contribution of the present study is that it increases the knowledge and understanding of matters that the children in the context investigated valued and needed in order to experience wellbeing and development during their early school years.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the children who shared their views.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allodi Westling, M. (2002). Children’s experiences of school: Narratives of Swedish children with and without learning difficulties. Scandinavian Journal of Education Research, 46(2), 181–205. doi: 10.1080/00313830220142191

- Allodi Westling, M. (2010a). Goals and values in school: A model developed for describing, evaluating and changing the social climate of learning environments. Social Psychology of Education, 13(2), 207–235. doi: 10.1007/s11218-009-9110-6

- Allodi Westling, M. (2010b). The meaning of social climate of learning environments: Some reasons why we do not care enough about it. Learning Environments Research, 13(2), 89–104. doi: 10.1007/s10984-010-9072-9

- Allodi Westling, M., Sundbom, L., & Yrwing, C. (2015 , September). Understanding and changing learning environments with goals, attitudes and values in school: A pilot study of a teacher self-assessment tool. Poster session presented at the ECER 2015: Education and Transition - Contributions from Educational Research, Budapest.

- Aronsson, K., Hedegaard, M., Højholt, C., & Ulvik, O. (2012). Introduction. In K. Aronsson, M. Hedegaard, C. Højholt, & O. Ulvik (Eds.), Children, childhood, and everyday life - children’s perspectives (pp. vii–2). Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental process. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & R. M. Lerner (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models for human development (5th ed., pp. 993–1028). New York: John Wiley.

- Cieciuch, J., Davidov, E., Schmidt, P., Algesheimer, R., & Schwartz, S. H. (2014). Comparing results of an exact versus an approximate (Bayesian) measurement invariance test: A cross-country illustration with a scale to measure 19 human values. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 982. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00982

- Cieciuch, J., Davidov, E., Vecchione, M., Beierlein, C., & Schwartz, S. H. (2014). The cross-national invariance properties of a new scale to measure 19 basic human values: A test across eight countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(5), 764–779. doi: 10.1177/0022022114527348

- Clark, A., & Moss, P. (2011). Listening to young children: The mosaic approach (2nd ed.). London: National Children’s Bureau.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008a). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological wellbeing across life’s domains. Canadian Psychology, 49(1), 14–23. doi: 10.1037/0708-5591.49.1.14

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008b). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 182–185. doi: 10.1037/a0012801

- Döring, A. K., Schwartz, S. H., Cieciuch, J., Groenen, P. J. F., Glatzel, V., Harasimczuk, J., … Bilsky, W. (2015). Cross-cultural evidence of value structures and priorities in childhood. British Journal of Psychology, 106(4), 675–699. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12116

- Due, C., Riggs, W. D., & Augoustinos, M. (2014). Research with children of migrant and refugee backgrounds: A review of child-centered research methods. Child Indicators Research, 7(1), 209–227.

- Education Act. (2010:800). Stockholm: Swedish Code of Statutes.

- Einarsdottir, J. (2008). Children’s and parents’ perspectives on the purposes of playschool in Iceland. International Journal of Educational Research, 47(5), 283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2008.12.007

- Einarsdottir, J. (2010). Children’s experiences of the first year of primary school. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 18(2), 163–180. doi: 10.1080/13502931003784370

- Eriksson, L., Welander, J., & Granlund, M. (2007). Participation in everyday school activities for children with and without disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 19(5), 485–502. doi: 10.1007/s10882-007-9065-5

- Hamlin, J. K. (2014). The origins of human morality: Complex socio-moral evaluations by preverbal infants. Research and Perspectives in Neurosciences, 21(1), 165–188. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-02904-7_10

- Hamlin, J. K., & Wynn, K. (2011). Young infants prefer prosocial to antisocial others. Cognitive Development, 26(1), 30–39. doi:10.1016/j.cogdev.2010.09.001

- Harms, T., Clifford, R. M., & Cryer, D. (2005). Early childhood environment rating scale-revised edition. New York: Teacher’s College Press.

- Harms, T., Clifford, R. M., & Cryer, D. (2010). Utvärdering och utveckling i förskolan: ECERS-metoden - att kvalitetsbedöma basfunktioner i förskolemiljö för barn 2,5–5 år: Manual [Evaluation and development in the preschool: The ECERS-R-method]. Stockholm: Hogrefe psykologiförlaget.

- Imms, C., Granlund, M., Wilson, P. H., Steenbergen, B., Rosenbaum, P. L., & Gordon, A. M. (2017). Participation, both a means and an end: A conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 59(1), 16–25. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13237

- Kahn, P. H. (1997). Developmental psychology and the Biophilia Hypothesis: Children’s affiliation with nature. Developmental Review, 17(1), 1–61. doi: 10.1006/drev.1996.0430

- Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15, 169–182. doi: 10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

- Kellert, S. R., & Wilson, E. O. (2013). The Biophilia Hypothesis. Washington: Island Press.

- Kellet, M. (2011). Empowering children and young people as researchers: Overcoming barriers and building capacity. Child Indicators Research, 4(2), 205–219. doi: 10.1007/s12187-010-9103-1

- Kragh-Müller, G., & Isbell, R. (2011). Children’s perspectives on their everyday lives in child care in two cultures: Denmark and the United States. Early Childhood Education Journal, 39(1), 17–27. doi: 10.1007/s10643-010-0434-9

- Lundqvist, J. (2014). A review of research in educational settings involving children’s responses. Child Indicators Research, 7(4), 751–768. doi: 10.1007/s12187-014-9253-7

- Lundqvist, J. (2016). Educational pathways and transitions in the early school years: Special educational needs, support provisions and inclusive education (Doctoral thesis). Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Lundqvist, J., Allodi Westling, M., & Siljehag, E. (2016). Characteristics of Swedish preschools that provide education and care to children with special educational needs. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 31(1), 124–139. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2015.1108041

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396. doi: 10.1037/h0054346

- Mason, J., & Danby, S. (2011). Children as experts in their lives: Child inclusive research. Child Indicators Research, 4(2), 185–189. doi: 10.1007/s12187-011-9108-4

- National Agency for Special Needs Education and Schools [Specialpedagogiska skolmyndigheten]. (2010). Pictogram för dem som behöver kommunicera med bilder. Retrieved from http://static.pictosys.se/pictogram/Pictogrambroschyr2013.pdf

- Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 133–144. doi: 10.1177/1477878509104318

- Qvarsell, B. (2015). Etik i barnrelaterad pedagogisk forskning och praktik - en fråga om respekt [Ethics in child-related educational research and practice: A matter of respect]. In B. Qvarsell, C. Hällström, & A. Wallin (Eds.), Den problematiska etiken. Om barnsyn i forskning och praktik [The problematic ethic: Views of children in research and practice] (pp. 31–48). Göteborg: Daidalos förlag.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). New York: Academic Press.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? Journal of Social Issues, 50, 19–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb01196.x

- Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz Theory of basic values. Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1–20. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1116

- Schwartz, S. H. (2017). The refined theory of basic values. In S. Roccas, & L. Sagiv (Eds.), Values and behavior: Taking a cross-cultural perspective (pp. 1–35). Cham: Springer.

- Siljehag, E. (2014). Pre-school teachers and special educators – a shared democratic mandate? In The 3dr Nordic ECEC conference in Oslo. Approaches in Nordic ECEC research. Current research and new perspectives (pp. 24–27). Oslo: Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. Retrieved from http://www.udir.no/tall-og-forskning/finn-forskning/rapporter/Konferanserapport----den-tredje-nordiske-barnehageforskningskonferansen/

- Siljehag, E. (2015). Etik i forskning där barn medverkar. En processtudie [Research ethics in research with children]. In B. Qvarsell, C. Hällström, & A. Wallin (Eds.), Den problematiska etiken. Om barnsyn i forskning och praktik [The problematic ethic: Views of children in research and practice] (pp. 117–142). Göteborg: Daidalos förlag.

- Smith, A. B. (2011). Respecting children’s rights and agency: Theoretical insights into ethical research procedures. In D. Harcourt, B. Perry, & T. Waller (Eds.), Researching young children’s perspectives. Debating the ethics and dilemmas of educational research with children (pp. 11–25). London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Soukakou, E. P. (2012). Measuring quality in inclusive preschool classrooms: Development and validation of the inclusive classroom profile (ICP). Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(3), 478–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.12.003

- Soukakou, E. P. (2016). Inclusive classroom profile. ICPTM (Manual Research ed.). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

- Soukakou, E. P., Evangelou, M., & Holbrooke, B. (2018). Inclusive classroom profile: A pilot study of its use as a professional development tool. International Journal of Inclusive Education. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2017.1416188

- Stanek, A. H. (2014). Communities of children: Participation and its meaning for learning. International Research in Early Childhood Education, 5(1), 139–154.

- Swedish Research Council [Vetenskapsrådet]. (2011). God forskningssed. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet.

- Swedish School Inspectorate [Skolinspektionen]. (2016). Förskolans kvalitet och måluppfyllelse 2015–2017 [Preschool quality and goal achievement 2015–2017]. Government Report. Dnr. 2015:3364.

- Swedish School Inspectorate [Skolinspektionen]. (2018). Förskolans kvalitet och måluppfyllelse – ett treårigt regeringsuppdrag att granska förskolan [Preschool quality and goal achievement: A three-year long school inspection]. Governement Report. Dnr. 2016:11445.

- Szczepanski, A. (2008). Handlingsburen kunskap: Lärares uppfattningar om landskapet som lärandemiljö [Knowledge through action: Teachers’ perceptions of the landscape as a learning environment]. Linköping: Linköpings Universitet.

- Tangen, R. (2008). Listening to children’s voices in educational research: Some theoretical and methodological problems. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 23(2), 157–166. doi: 10.1080/08856250801945956

- Taris, T. W. (2000). A primer in longitudinal data analysis. London: SAGE.

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Retrieved from http://www.regeringen.se/content/1/c6/12/36/15/618de295.pdf

- Wendell, S. (1996). The rejected body: Feminist philosophical reflections on disability. New York: Routledge.

- Wiltz, N. W., & Klein, E. L. (2001). What do you do in child care? Children’s perceptions of high and low quality classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 16(2), 209–236. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(01)00099-0