ABSTRACT

Based on the wide-ranging liberal reforms introduced in the early 1990s, Sweden has become one of the most prominent realizations of Milton Friedman’s proposal for market-based schooling. From 1991 to 2012, the percentage of Swedish ninth-grade students attending independent, voucher-financed, private schools increased from 2.8% to 14.2%. A recent study using municipality-level data claimed that the resulting increase in school competition positively affected student performance in both private and public schools. In this study, using data on 2,154,729 school leavers, we show that this result does not hold when controlling for individual-level background factors and differences in the peer composition of schools.

Introduction

This study focuses on school competition and school performance among Swedish school leavers from 1991–2012. In the Swedish context, the reforms made in the early 1990s created opportunities for both municipal and independent actors in the so-called school market (Forsberg, Citation2015). With public and private providers, the possibility of choosing a school and the allocation of financial resources based on the choices made, the system was designed to create space for competition and make schooling more efficient and based on individual choice. Thus, competition was a core factor in the neoliberal and decentralization trends that influenced the policy agenda targeting the Swedish school system (Bunar, Citation2010).

Currently, the Swedish school system is seen as a hybrid model. There have been efforts to increase the market control and public authority control in the school system (Bunar, Citation2010; Rönnberg, Citation2011). Free choice of a school and the right for private initiatives to establish schools and to make profits through school corporations have been defended and preserved. The Swedish Schools Inspectorate (est. 2008) controls the applications to open schools and regulates the criteria for admission to schools, the local authorities (municipalities) regulate school vouchers, and the cost of the schools falls on the municipalities.

In the international debate, Sweden has been noted as having the most neoliberal school system in the world (along with Chile, which has now regulated the gains from school corporations). Furthermore, among the Scandinavian countries, Sweden’s school market has been highlighted as a special case and the most neoliberal one (Wiborg, Citation2013). Therefore, Sweden is an interesting case to analyze due to the increasing competition over the years and because the system is consistent across regions and municipalities in terms of regulations.

In researching this reformed system, researchers have measured the effects of competition between municipal and independent schools in relation to students’ performance. Some studies support that achievements are substantially stronger in instances where competition is more intense (Bergström & Sandström, Citation2007; Böhlmark & Lindahl, Citation2015). Other studies report relatively weak positive effects (Edmark, Frölich, & Wondratschek, Citation2014). Epple, Romano, and Zimmer (Citation2015) describe different studies of the effect of charter schools on local student results but the results are contradictory. In this study, the aim is to build on the study of Böhlmark and Lindahl (Citation2015) and assess the role of competition on performance in an educational system, as measured by the local presence of independent schools. The role of competition is measured for educational achievement controlling for individual-, school- and neighborhood-level data for a total population of 2.15 million 15-year-old students in Sweden. Below, the framework for this competition is described further.

The Swedish Hybrid System

During the post-war period, the expansion of educational opportunities for low- and middle-income groups was an important part of the social democratic program to build an all-encompassing welfare state (Blomqvist, Citation2004). Two reforms were particularly important: the establishment of a comprehensive and compulsory 9-year school in the early 1960s and the establishment of comprehensive upper-secondary education in the early 1970s catering to both students pursuing tertiary education and students pursuing vocational education. The responsibility for managing the primary and secondary schools was given to the municipalities after a major reform ensured that all such municipalities were sufficiently large to handle the schools efficiently (Román & Ringarp, Citation2016). However, the municipalities were not given full control of the schools. A powerful, centralized governing board made detailed decisions on curriculum, grading, and textbooks and provided continuous oversight (Blossing, Imsen, & Moos, Citation2014; Lakomaa, Citation2011).

In the early 1990s, a newly formed conservative government initiated radical reforms. The reform had three pillars: the right for private actors, including for-profit companies, with adequate qualifications to be officially recognized as education providers; voucher-based financing of compulsory and upper-secondary education; and an acknowledgement of the parents’ right to select the school they want their children to attend. These reforms, modeled after Milton Friedman’s ideas about free school choice (Friedman, Citation1955), gave Swedish primary and secondary education a regulatory framework that was similar to neo-liberal ideas. However, although free entry for private actors and unrestricted parental selection of schools represent a high degree of marketization, the tradition of strong governmental control has not been abandoned. Various authors have designated Swedish primary and secondary education as a hybrid system that combines strong marketization and continued bureaucratic controls (Bunar, Citation2010; Christophers, Citation2013; Nicaise, Esping-Andersen, Pont, & Tunstall, Citation2005; Rönnberg, Citation2011).

Municipalities are expected to assign students to schools in accordance with the wishes of the student’s parents. If allowing a student to attend a specific school would hinder another student from attending a close-to-home school, the demands of the parents may not be met (§ 30 Education Act) (Regeringskansliet, Citation2010). Municipalities are also required to pay private providers of compulsory education for students from the municipality who attend independent schools. Before an independent school is opened, the private provider must obtain approval from the Swedish Schools Inspectorate to start a compulsory school. Independent schools are required to be open to all students who have a right to compulsory education (§ 35). If the independent schools want to select students, this selection must be based on the principles established by the Swedish Schools Inspectorate (§ 36). Additionally, the selection criteria are not allowed to jeopardize the principle of openness.

The inspectorate decides on licenses for starting new or expanding independent schools in Sweden. They follow-up to ensure that the schools are created in accordance with the licensed conditions. They also receive applications from independent and municipal schools that desire to conduct lessons in English, operate compulsory school education without applying the set timetable, or implement proficiency tests (as accounted for above). The inspectorate reports that there has been a decline in the number of applications to start new schools and the number of schools that have obtained licenses since 2009. The establishment of independent schools is concentrated in large cities. Currently, primarily established school corporations acquire new licenses. The most common reason for the inspectorate to deny applications has been the size of the student base, such as not having enough anticipated students. There are reasons to believe that it is now more difficult to obtain a license than in the early 1990s (The Swedish Schools Inspectorate, Citation2016).

Before the school reform in 1992, the Swedish state granted independent schools one school voucher per student per year, with the requirement that the school represented an alternative to public schools, such as an alternative pedagogical orientation or boarding school. After the reform, the need for independent schools to provide an alternative to public schools ended, the ability for schools to charge a fee became restricted, and independent schools were given a voucher from the municipality corresponding to at least 85% of the amount that the municipality spent on education per student. In practice, this meant that the size of the school voucher per student quintupled and it became economically attractive for corporations to engage in independent schools. In 1997, the remuneration was changed to 75% of the municipality’s cost, and the ability to charge a fee disappeared. In 2010, the voucher changed again. It was the same for all students, regardless of whether they studied at a school operated by the municipality or at one operated by an independent actor. Now, the home municipality of the student grants a basic voucher that is supposed to cover the costs of students’ education, health, and meals. In cases involving students with special needs, an additional amount is granted (Angelov & Edmark, Citation2016, pp. 27–32).

Parents and students can choose a school freely. As long as there are vacancies, schools must admit the students who apply. This openness in admitting students was first described in the Education Act 2010:800, Chapter 10, 36 § (Regeringskansliet, Citation2010). When there are more applicants than available spaces, only the selection criteria approved by the Swedish Schools Inspectorate (established 2008) can be used. When there is a queue, the approved criteria include the date of the notice, sibling priority, geographical distance to the school, priority to students who have already started preschool and six-year-olds at the same school and if there is a functionality or alignment in the education (e.g., Waldorf, Montessori) that a student follows. Both municipal and independent schools use these criteria. However, the date of the notice criterion is only used by independent schools. With approval from the inspectorate, the school can use other criteria, such as admission based on proficiency tests in music (Chapter 10, 9–9a §§ Education Act 2010:800). In practice, relatively strict limits on the number of students admitted to different schools in combination with the priority given to students living nearby (at municipal schools only) has restricted the options for students.

Many municipalities have organized a centralized admission system: an online application system that encompasses both municipal and independent schools. Other municipalities have more simplified systems in which children are assigned to the nearest municipal school unless they opt out and apply to an independent school with its own admission system.

The hybrid nature of Swedish compulsory education makes it an interesting case for analyzing the effect of competition. A clearly formulated regulatory framework in combination with a tradition of efficient public administration at the local and central levels has made the establishment of independent schools a relatively simple and hassle-free process. This has allowed independent schools to increase their share of compulsory education across a broad range of municipalities. Substantial variation in the market share of private school providers remains across municipalities, which enables student performance to be compared between municipalities with strong or weak competition.

In addition to be an interesting case to study due to its hybrid nature, the school voucher program in Sweden is noted as a successful pioneering project that other countries should emulate (Holland, Citation2003). For example, in an op-ed video by The New York Times, Izumi explained why he thought that the Obama administration should take inspiration from the school voucher program in Sweden (Izumi, Citation2009). In The Guardian, Svanborg-Sjövall (Citation2013) noted that the Swedish school reform had an important influence on education policy in the UK and argued, based on a study by Böhlmark and Lindahl (Citation2012), that it has been shown that “the average performance in state schools increased long-term as a result of more independent schools entering the market, and school expenditure has not risen” (Svanborg-Sjövall, Citation2013).

Earlier Research on School Competition

The introduction of open enrollment and voucher financing in Sweden as school reforms can be viewed as inspired by ideas that were initially developed and promoted by economists. Early attempts to evaluate the effects of these reforms have been largely dominated by economists (see, for example, Bergström & Sandström, Citation2007; Böhlmark & Lindahl, Citation2015; Edmark et al., Citation2014). In these studies, geographical variations in student outcomes played a central role in identifying the effects of increasing competition. Various methods have been employed to ensure that the estimated effects reflect the effects of competition and not an underlying factor that can affect student outcomes. In terms of the statistical approach, these studies differ from the modeling approaches used to study school outcomes by researchers outside economics. The standard approach over the last 20 years has been to use a multilevel statistical framework to manage the interaction between individual-level and group-level effects (Leckie, Pillinger, Jones, & Goldstein, Citation2012; Snijders & Bosker, Citation2012). In research on the effect of competition, the possibilities of a multi-level design and the contextual effects framework have not been fully realized. This is unfortunate because the effect of local competition on individual-level outcomes can be understood as a contextual effect. Thus, a multilevel framework would allow the effects of competition to be disentangled from other contextual effects, such as changing school composition and changes in residential composition, including large regional shifts in the education level.

In 2010, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published an extensive literature review on how the introduction of market mechanisms affected education systems in different countries. One consistent finding is that increased school choice tended to increase school segregation (Waslander, Pater, & Weide, Citation2010). In the early stages of these schemes, it was argued that allowing parents to select non-neighborhood schools would make it possible to reduce the school segregation that results from residential segregation (Lindbom, Citation2010). This possibility has not been realized (Allen, Citation2007; Östh, Andersson, & Malmberg, Citation2013). Studies indicate increasing school segregation in terms of ethnicity, socio-economic background and ability (Noreisch, Citation2007).

Economic models of school choice suggest that the existence of peer effects on educational achievement provides independent schools with an incentive to recruit high-ability students, a phenomenon referred to as “cream skimming”. In tuition-based systems, this can be achieved by subsidizing fees for poor, high-ability students (Epple & Romano, Citation2012). In Sweden, independent voucher-financed schools are not allowed to charge tuition and thus cannot use tuition to influence the student composition. Independent schools can choose where to locate (Trumberg, Citation2011), and their location influences how costly and far away the school is for different students. Thus, location can be used as a tool to influence the composition of the student body, especially because students with a majority and middle-class background tend to commute longer distances than do minority students from non-middle-class families (Allen, Citation2007; Andersson, Malmberg, & Östh, Citation2012; Butler & Hamnett, Citation2010; Reay & Ball, Citation1997). In the US, various studies have analyzed the locations chosen by charter schools. The results suggest that these schools aim to recruit a select group of students (Glomm, Harris, & Lo, Citation2005; Gulosino & d’Entremont, Citation2011). An overview of American research on the effect of charter school competition on student performance in public schools was presented by Epple et al. (Citation2015). They found that “the current body of evidence on the competitive effects of charter schools is mixed, which may be disappointing to the advocates of charter schools” (p. 55).

For our study, evidence of the effects on educational achievements of competition between schools is of interest, particularly the study by Böhlmark and Lindahl (Citation2015). In this highly cited study, Böhlmark and Lindahl examined shifts that occurred from 1992 to 2009 in the share of compulsory school students in Swedish municipalities who attended independent schools and correlated these shifts with changes in the performance of compulsory school students. However, Böhlmark and Lindahl did not include individual-level data in their estimation and thus could not use individual-level control variables or school level control variables. They used municipal-level data and thus could only use municipal-level control variables, including the following: the share of students with at least one university-educated parent, share of students with at least one high school-educated parent, average family earnings, share of second-generation immigrant students, and share of foreign-born students and municipality averages for students’ gender, parents’ age at the birth of the child, mother’s years of schooling, father’s years of schooling, indicator variables for missing parental schooling, and immigrant’s age at immigration. In addition, to eliminate municipal-level fixed effects, they used the changes in these variables and in students’ grades from 1992 to 2009 in their estimations. In an earlier version of this paper (Böhlmark & Lindahl, Citation2007), using data up to 2003 only, they employed annual data with and without a municipality fixed effect. Without the fixed effect, the share of students in independent schools did not have a significant effect on student performance when municipal control variables were included. When a municipal fixed effect was introduced with the control variables, a significant positive effect of independent school was found. The specification used in their 2015 article corresponds to the use of a municipal fixed effect, as the differences in the variables included in the model remove the municipal average (taken over time) in the same manner as would the introduction of a municipal fixed effect.

Using aggregate data to estimate effects on student performance raises some concerns. Parameters that are estimated using aggregate data may not reflect individual-level effects. This is the so-called ecological fallacy (Piantadosi, Byar, & Green, Citation1988).

Contrary to Böhlmark and Lindahl (Citation2015), in this paper, we estimate the effect of independent schools by using a model with individual-level data. This allows us to control for individual background factors more precisely and for possible school and neighborhood effects on student performance. As we demonstrate below, accounting for school-level effects can be critical to assess how competition effects school performance.

Data and Study Design

This study assesses the role of competition in the school market in general terms and has a narrower aim of testing a previously studied measurement (i.e., Böhlmark & Lindahl, Citation2015) of school competition using an alternative method and different data. Both queries can be approached by estimating the effects of the share of independent schools on grades over a period characterized by a growing independent school market.

To compare and build upon earlier research, we use register data from Statistics Sweden, which is the official collector of statistics in Sweden. Registers have been used since 1990, when the last census was conducted. The main Statistics Sweden data sources used in this study are the student register of The Swedish National Agency for Education, the population register, the register of real estate assessments, the geography database, and the integrated, longitudinal database for health insurance and labor market studies, LISA. These data were combined into a SQL database designed specifically for the needs of this research by Statistics Sweden and made available to us through a remote desktop solution (Geostar, Citation2015). The geographical coordinates of every individual who has lived in Sweden since 1990 are available in Geostar. The register data in Geostar were used to extract those who completed ninth-grade school every year and to construct the dependent variable, the share of independent schools variable, and three sets of independent variables, individual background variables, school composition variables, and residential area peer composition variables. These variables are described in more detail below.

The effect of these variables on student performance was analyzed using multilevel regression models. Such models are used when the data have a nested structure, such as students in schools and neighborhoods. There must be enough within-level variation to necessitate the use of multilevel analyses. We estimated one model for each of the 22 years studied, starting with an empty model without independent variables. Then, different groups of variables were included using stepwise entry. First, only the share of students in independent schools variable was entered (Model 1). Second, individual-level variables were added (Model 2). Third, school-level variables were entered (Model 3). Finally, neighborhood variables were added to the model on the individual level (Model 4). Models 5 to 8 consist of different combinations of individual, school and neighborhood data (see for a full description). The models were estimated using maximum-likelihood as implemented in the MLwiN 2.1 software. In this paper, our focus is on the estimates obtained for the effect of the share of independent schools in municipalities. Another study using a similar design by Andersson, Hennerdal, and Malmberg (Citation2016) focuses on comparing the effects of the school context and the residential peer context on student performance.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in this study is the grade (as a score) of each student in ninth grade, transformed into a percentile rank score. A score of 1.0 was given to students who had the highest grades, and a score of 0.0 was given to students with the lowest grades. The grade score was calculated as the sum of the grades for the main school subjects. The ninth grade is the final year of compulsory school, which implies that all students follow the same curriculum. A potential problem is that the Swedish grading system changed after 1994. We handled this issue by using percentile rank scores. Using the percentile rank of student grades eliminates the effect of grade inflation, which is the general tendency for a teacher to give higher grades over time.

Individual-Level Data

As we build upon earlier research (Böhlmark & Lindahl, Citation2015) in which the share of independent schools in the municipality was examined, we also try to refine the tests. We stress the importance of using individual data, not aggregated individual data, to avoid the ecological fallacy by making inferences relating to individual-level outcomes from aggregate data.

A study in which the influence of school and neighborhood peer effects on educational achievements are controlled for must have reliable individual variables. For this purpose, we included the following variables for individuals: sex, country of birth, whether their parents receive a social allowance, whether their parents have tertiary education, whether their parents are non-employed, and whether they live in a single-parent household. We also included the following variables for individuals: the family’s disposable income and whether they live in single-family housing (see ). Whether the students have foreign-born parents was excluded due to the strong correlation with the country of birth.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, percentages and standard deviations for four years.

Previous studies supported the selection of variables included in this study. Female students usually have higher achievement in school in Sweden, whereas students with parents receiving a social allowance, who have parents who were born abroad, or who have single parents usually receive lower grades (Andersson & Subramanian, Citation2006). Furthermore, students with tertiary-educated parents perform better in school than do their counterparts, as do students with high-income parents and students living in single-family housing. Variables such as parental non-employment and being born abroad are likely to negatively affect students in terms of their educational achievement (Andersson & Malmberg, Citation2015).

The number of students who completed grade 9 during the 22 years studied was 2,356,695. However, due to missing data in the register on family background, approximately 30% of the students were lost in 1991 and following years. This loss decreased to 5% in 1998. From 2001 until the end of the study period, the loss of data each year was below 2%. The number of student cohorts leaving compulsory school increased up until 2006, when the number was greater than 120,000, and it subsequently decreased until the last year measured. The decrease in students from 2006 to 2012, in combination with a nearly constant number of schools in the same period, could have created more competition in recruitment among schools.

Of the students in our sample, approximately 60% lived in single-family housing. That figure did not change much over time. Girls and boys were evenly represented in the material and the level of tertiary education among parents increased from approximately 30% in 1991 to more than 40% in 2012.

Over the years, foreign-born parents increased in proportion, as did single-parent households. The average percentile for the parents’ disposable income in relation to the rest of the Swedish population remained unchanged during the study period, except for the variation due to the change of equalizing weights for children when reconstructing the variable after 2004.

School-Level Data

The school population consisted of 15-year-olds for every year. To include more than just that year’s students, we included those finishing the ninth grade both the year before and after the particular cohort of students when we computed the measures of school composition. Thus, for students finishing ninth grade in 2000, students finishing that year and students finishing in 1999 and 2001 constituted the school population (see ). Students in schools with fewer than 15 students (including the year before and after graduation) were excluded from the sample. The correlation between the school-level variables is high, often greater than 0.60 or less than −0.60. This suggests that multicollinearity can be a problem and that the individual parameter estimates presented below for these variables should be interpreted with some caution. When the students were aggregated into schools, the distribution of the shares of the students in the schools had a bell-shaped distribution for female students, parents with tertiary education, students from single-parent households and family disposable income. Foreign-born students, foreign-born parents, parents receiving a social allowance, single-family housing and non-employed parents variables showed a skewness in the distribution.

Neighborhood Data

The population in the residential neighborhood surrounding each 15-year-old student was defined as the peers aged 13 to 17 years who lived closest to the student (see for the variables). Using a multi-scalar approach, we gradually expanded the neighborhood from the 12 closest peers (k = 12) to the 800 closest peers (k = 800). We found lower −2*log likelihood values for models using lower k values. For all 22 years, the lowest −2*log likelihood values were for either k = 12 or k = 25. This suggested that the contextual influences were the strongest for those k values. Consequently, we used contextual measures based on k = 25 to evaluate the effect of residential context on school performance (see Andersson et al., Citation2016).

In the data, the geocode for each individual corresponded to the place of residence on December 31 of each year. Grades are reported in June. Therefore, to avoid measurement errors resulting from students’ moving after having finished compulsory school, the residential context was measured in relation to where the students lived on December 31 the year before graduation.

Due to the individualized neighborhoods, there is no possibility to group the students into neighborhoods as a new level in the multilevel analysis. Thus, the neighborhood variables are introduced at the individual level in the multilevel models. When the students were aggregated into neighborhoods, the distribution of the shares of the students in the neighborhoods had a bell-shaped distribution for parents with tertiary education, students from single-parent households and family disposable income. The foreign-born parents, parents receiving a social allowance, single-family housing and non-employed parents variables had a skewness in their distributions.

Share of Students in Each Municipality that Graduate from Independent Schools

For 1998 to 2012, data for each municipality regarding the share of students in the last year of compulsory school who attended an independent school were available from The Swedish National Agency for Education (Citation2016). For the seven years before 1998 that were included in this study, the data were constructed using Geostar (Citation2015). In the student database, there were no data regarding whether the students went to a school operated by a private actor. However, the register provides data about the location of the school. To compute the share of students in the ninth grade who studied at schools run by private actors for each municipality and each year, the locations of workplaces at which people work with compulsory education were used. From the data, it was possible to determine the workplaces with people who were employed by a private company and categorize the students attending a school located closest to the private workplaces as students attending a school run by a private actor. For the workplace locations in which there were employees working for both the municipality and a private company, the students were assigned in proportion to the proportion of employees. A comparison of the calculated statistics with the official numbers available for 1998 to 2012 showed that this method works well and provides reliable results.

Trends in Student Composition

presents the descriptive statistics for the independent variables included in the study, showing the composition of the student population and how it changed from 1991 to 2012. Notably, the share of individuals with foreign-born parents in the student population increased considerably, as did the share of individuals who have parents with tertiary education. The share of foreign-born students also varied over the years and was higher in 2012 than it was 1991. The share of students with non-employed parents increased rapidly in the 1990s before declining, although it remained higher than that observed in 1991.

also shows the variation in school composition and residential peer context. The table shows that the percentages of foreign-born students and students with foreign-born parents increased, as did the variation in the share of such students between schools and across neighborhoods. The same is true for the share of students with non-employed parents. Another change is that there was increased variation in the gender composition of schools. In addition, the variation in the mean percentile family income of residential peers increased across neighborhoods but not between schools.

Results and Discussion

This study used multilevel models to investigate if the parameter estimate for the municipal share of independent school students was correlated with students’ grades. Different models were used to study how the inclusion and exclusion of different socio-economic variables (individual variables, school composition variables, and neighborhood composition variables) affected the results. The results were calculated for all eight models and each of the 22 years separately. There was very little between-school variation at the start of our study period (ICC = 2.54%), but it increased substantially over the next 14 years, with the ICC reaching 13.7% in 2005 (see Supplemental file for more details). We also tested the results using single-level models to examine the robustness of the results; the results are not presented in this paper. In single-level models, the effect of clustering is not considered, so the standard errors are underestimated (see Sarzosa, Citation2012). Thus, as expected, the width of the confidence intervals was reduced compared with those of multi-level models. The parameter estimate showed the same patterns.

Results from the Eight Models

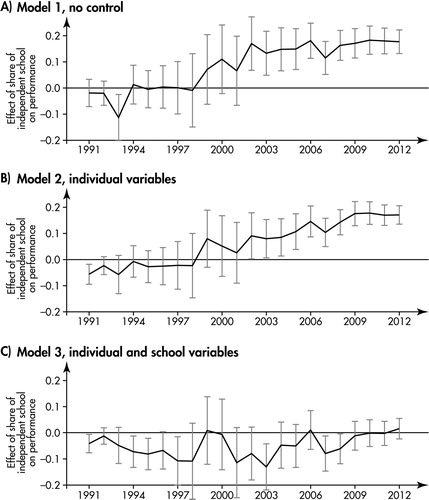

The most important finding in the results was that, with a model including the share of independent schools in the municipality as the only independent variable to test the correlation with grade as the dependent variable, a high share of independent schools in the municipality had a positive correlation with grades, beginning in approximately 2002. This pattern was also apparent when neighborhood data were included in the model. However, by adding school-level data, no statistically significant effect on grades could be explained by the share of independent schools.

For example, the parameter estimates for all the variables and all multilevel models used for the year 2012 are shown in (see Tables S1–S8 in the online supplementary material for parameter estimates for all years). Model 4 is the full model with all the variables included. The parameters for individual-level variables are estimated together with school-level and neighborhood variables. As expected, the individual-level variables had significant effects on grades. Being female was positively associated with grades, as was having parents with tertiary education. Moreover, the higher the parental income was, the higher the students’ grades were. Living in single-family housing was also positively associated with students’ grades, but not to the same extent as the other variables. The grades of students who were foreign-born, had parents receiving a social allowance, had parents who were non-employed or lived with a single parent were lower. These estimates were constant across all models. In , the AIC (Akaike information criterion) values in Models 2–5 show the importance of the individual-level variables. Including them reduced the AIC values by more than 75%. Over time, the parameter estimates of the individual level variables were stable, except for income. According to the parameter estimates, the effect of income increased over time (see Supplemental file, Table S4).

Table 2. Multilevel models and estimates for 2012, with grades as the dependent variable. Statistically significant parameter estimates (p < 0.05) are shown in bold. The share of students in independent schools in the municipality is for 2012 (the results for all years 1991–2012 can be found in the online supplementary material, Tables S1–S8).

In Model 4 shown in , the schools’ student composition had both positive and negative effects on students’ grades. The estimates had similar signs to those at the individual level. Being at a school with a greater proportion of female students, having parents with tertiary education and having parents who were foreign born were positively associated with students’ grades. This is interesting because it suggests that the negative effect of being foreign born is not linked to ethnicity. In contrast, being at a school with a large share of foreign-born students and a large share of single-parent households had a negative effect on students’ grades. Only the sign for the estimate for living in single-family housing changed. As a school characteristic, the share of students in single-family housing was negatively associated with students’ grades. This might be explained by the fact that schools with a large share of students in such housing are located in regions in which the overall educational level and incomes are lower. The importance of the school variables in affecting students’ grades can also be assessed based on the AIC values. The change in AIC was 316, indicating a non-negligible effect, although this change is much smaller than the change that occurred when individual variables were added (see Menard, Citation2000 on the interpretation of log-likelihood and AIC values as “error variation”). Over time, there were changes in the parameter estimates for the school-level variables. The parameter for proportion of foreign-born students became more negative, whereas the parameters for mean income and proportion of girls increased, and the proportion of students with foreign-born parents became more positive (see Supplemental file, Table S4).

Model 4 also included variables that capture the neighborhood context of the students. Adding these variables improved the fit of the model, as shown in . There was a decrease in the AIC value. Both having peers with highly educated parents and having peers with high-income parents had a significantly positive effect on school performance. This is in agreement with expectations and corresponds to the effects for these variables using individual-level and school-level measures. Positive significant effects of having a high share of non-employed parents and single-parent households in the neighborhood were found. These findings are in contrast to the effect found for the corresponding variables measured at the individual and school levels. The estimates for the neighborhood variables were relatively sensitive to the other variables included in the model, especially when controlling for individual-level variables (see Model 8 compared to Model 5). The effects of tertiary education and income decreased when individual-level control variables were added. Interestingly, the effect of having neighbors in single-family dwellings changed from positive to negative when individual-level control variables were added. Furthermore, the effect of having neighbors receiving a social allowance lost its significance when individual-level variables were controlled for. The change in AIC associated with adding the neighborhood variables to the model with individual control variables was larger than the change in AIC associated with adding the school variables (579 compared to 316). Over time, the parameter estimates for neighborhood context variables were relatively stable, with one exception: the estimate for income became more positive (see Supplemental file, Table S4).

The parameter estimates for the individual-level, school-level, and neighborhood variables showed that our control variables were effective. The key question in this paper is related to how the share of students in independent schools at the municipal level affects student performance. As shown in , the estimate for this variable varied considerably across different models. In Model 1, with no control variables, it had a relatively strong positive and significant effect. Adding individual-level control variables (Model 2) did not change the estimate much, and the estimate was still significant. Adding additional neighborhood control variables (Model 5) reduced the estimate for the share of students in independent schools by nearly 50%, although this effect was still significant. If school-level control variables were added (Model 3), only 10% of the effect of independent schools remained and the estimate was not significantly different from zero. With all the control variables included (Model 4), almost no effect remained. The point estimate was 0.005, compared to 0.171 in the model with individual-level controls and 0.177 in the model with no controls. The relative weakness of the independent school variable is indicated by the fact that the change in AIC associated with adding it to the model with the individual control variables was only 77.

The results obtained with only individual-level control variables were similar to those obtained by Böhlmark and Lindahl (Citation2015), who estimated the effect of independent schools using data that were aggregated to the municipal level. Thus, it could be that this aggregated approach is successful in controlling for individual-level parental background but not the added effect of school composition. In addition, as our estimates show, when school composition effects are controlled for, the positive effect of independent schools disappears. Given the large change in AIC that results from adding individual control variables and the much smaller change that results from adding school control variables, it may be surprising that the latter, not the former, has such a strong effect on the estimate for independent schools. A possible explanation for this is presented in the conclusion.

The structure of Model 1, which has no variables (only the share of students in independent schools in the municipality), is shown in A. In earlier years in the period, the variable had a negative or non-existent effect on grades. However, from 2002, there was a positive association between the share of students in independent schools and grades; i.e., the higher the share of students in independent schools in the municipality was, the better their grades were. This was also the intended result of the school reform designed to promote competition to improve students’ outcomes. However, it is important to note that this is the first raw result when no individual, school or neighborhood controls were added to the model. The increase in the effect of the share of students in independent schools is in line with earlier research over the same period in which increased individual and neighborhood effects were found (Andersson et al., Citation2016).

Figure 1. Parameter estimates for the share of students in independent schools in the municipality from 1991 to 2012. Bars show the 95% confidence intervals. The three diagrams show the parameter estimates for three different models. A) Model 1 is an empty model, except for the share of students in independent schools in the municipality. The parameter estimates show that, since 2001, students’ grades were positively correlated with the share of students in independent schools in the municipality. B) In Model 2, individual variables were added. The parameter estimates for this model since 2002 also show a positive correlation between students’ grades and the share of students in independent schools in the municipality. C) In Model 3, which includes both individual variables and school composition, there was no significant correlation between students’ grades and the share of students in independent schools in the municipality.

In graph B in , the pattern of the effects of the share of students in independent schools largely stays the same, although they are slightly lower.

C shows that the above-measured effects of the share of students in independent schools in the municipality disappeared when school-level control variables were added to the model. Thus, the positive effects on grades in the models with no control variables and individual-level control variables are explained and accounted for by school-level variables. However, the negative effect of independent schools at the beginning of the period, the 1990s, remained.

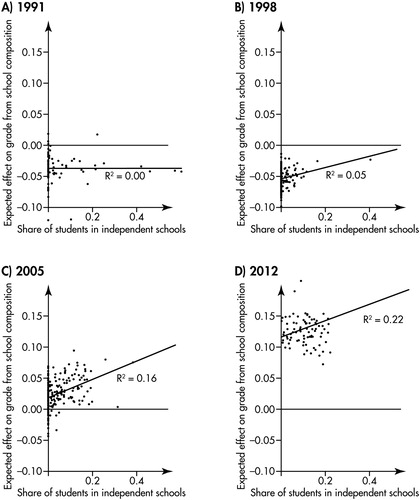

Municipalities with Favorable School Compositions and Independent Schools

Using the parameter estimates for the school variables, it was possible to calculate the municipalities that had the most favorable school compositions according to the estimated model.Footnote1 We used the estimates of Model 3 (see Table S3 in online supplementary material for estimates for all years or for the 2012 estimates) because including residential context variables is not necessary to analyze the effects of school composition on the estimate obtained for the share of the independent school variable. shows the expected effect on the grade of the average student of the school composition in the municipality according to Model 3 and the extent to which this effect is correlated with the share of students in independent schools in the municipality for four different years. There was a positive correlation in 2012 between the share of students in independent schools in the municipality and the effect of the school composition on grades in each municipality. This correlation grew stronger during the study period (from no correlation at all in 1991) and provides an explanation for why regression models without school composition variables can show a positive correlation between the share of independent studies in the municipality and grades.

Figure 2. The expected effect on the grade that the average student experiences from the school composition in the municipality according to Model 3 and the extent to which this effect is correlated with the share of students in independent schools in the municipality for four different years. The selected four years are evenly distributed in the studied time span, and the trends between these years are continuous.

Conclusion

In this paper, we addressed the question of how school competition affects student performance using data on Swedish students who graduated from compulsory school from 1991 to 2012. During this period, enrollment in privately managed, voucher-financed, independent schools increased significantly but unevenly across Swedish municipalities. An earlier study using data that were aggregated at the municipal level showed that an increasing presence of independent schools in a municipality had a positive effect on student performance. The interpretation was support for the idea that competition increases school performance (Böhlmark & Lindahl, Citation2015). We used a similar design, but instead of aggregating the data, we estimated individual-level models to control for parental background, school composition and residential context. In models with no control variables and individual-level control variables, we reproduced the results (Citation2015). Starting in approximately 2002, there was a positive effect of independent school presence on student grades. However, this positive effect was not robust to the inclusion of school-level control variables. When school composition was controlled for, the parameter estimate for the share of students in independent schools in the municipality was reduced drastically and there was no positive effect on grades.

To interpret these results, it should be noted that the estimates that we obtained indicated that grades were influenced by parental background and by school and neighborhood peers (and their parents’ characteristics). These contextual effects on school performance imply that school segregation and residential segregation that sort students with advantaged and disadvantaged backgrounds into different schools and neighborhoods have the potential to increase the impact of students’ socio-demographic position on their educational performance. If there was no segregation, the direct effect of family context would be the only mechanism by which socio-demographic status influences performance. With segregation, however, there can be two additional effects. Children from a family background that promotes school performance can be sorted into schools with similar children, which gives them additional educational benefits. In addition, children from a family background that promotes school performance can be sorted into neighborhoods with similar children, which gives them additional educational benefits. Furthermore, the opposite is true for children with a family background that is less supportive of school performance. Notably, if there were perfect sorting, it would be difficult to separately estimate the effects of individual factors, school context, and residential context. Perfect sorting would imply that the student composition in the school that a student attends would be completely determined by family background factors; hence, these factors would capture both individual-level effects and peer effects. With less-than-perfect sorting, there is variation in the context for students with similar family backgrounds, which allows for identification of the contextual effects.

Given that our model estimates support the existence of school effects and neighborhood effects and the effects of family background, the previous results may have been related to a failure to account for contextual effects (Böhlmark & Lindahl, Citation2015). The fact that the estimate for the share of students in independent schools was reduced to zero when school context and residential context were controlled for indicates the possibility that the independent school share is masking the effects of school composition and neighborhood composition. The effects are not well accounted for in models using aggregate data. Such masking could result if independent schools preferred to be located in municipalities with a relatively large proportion of students coming from family backgrounds that promote school performance. As explained in the introduction, private providers of compulsory education in Sweden are free to establish themselves wherever they expect the highest financial returns. Thus, targeting high-income areas and highly educated families is possible.

The interpretation that the share of students in independent schools is masking school composition is further supported by the finding that the positive effect of independent schools in models with no control variables for school context increased over time. This corresponds to the increasing importance of school composition for student outcomes identified by Andersson et al. (Citation2016).

Our finding that the Swedish data fail to support the idea that increased private-public competition enhances school performance is not without interest, given that Sweden has been proposed as an example demonstrating that neo-liberal school reforms have beneficial effects. The conclusion from this paper is that the Böhlmark and Lindahl analysis of the Swedish case cannot be used to substantiate such claims about the beneficial effects of school competition, as their identifying assumption of constant individual level and contextual effects on school performance cannot be upheld.

Supplementary material, Tables S1–S8

Download MS Excel (86.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Pontus Hennerdal http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3942-0427

Bo Malmberg http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7345-0932

Eva K. Andersson http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9620-1314

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 First, we calculated the average school composition for the students in each municipality for each of the nine variables. Then, the expected effect on the grade from the school composition for each municipality was calculated by applying the parameter estimates for Model 3 to these average values.

References

- Allen, R. (2007). Allocating pupils to their nearest secondary school: The consequences for social and ability stratification. Urban Studies, 44(4), 751–770. doi: 10.1080/00420980601184737

- Andersson, E., Hennerdal, P., & Malmberg, B. (2016). Changing influence of school context, neighborhood and family on educational outcomes during a period of liberal reforms: A study of Swedish school leavers 1991–2012. Paper presented at the ENHR, European Network for Housing Research.

- Andersson, E., Malmberg, B., & Östh, J. (2012). Travel-to-school distances in Sweden 2000–2006: Changing school geography with equality implications. Journal of Transport Geography, 23, 35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.03.022

- Andersson, E., & Subramanian, S. V. (2006). Explorations of neighbourhood and educational outcomes for young Swedes. Urban Studies, 43(11), 2013–2025. doi: 10.1080/00420980600897834

- Andersson, E. K., & Malmberg, B. (2015). Contextual effects on educational attainment in individualised, scalable neighbourhoods: Differences across gender and social class. Urban Studies, 52(12), 2117–2133. doi: 10.1177/0042098014542487

- Angelov, N., & Edmark, K. (2016). När skolan själv får välja. Stockholm: Finansdepartementet.

- Bergström, F., & Sandström, M. (2007). Konkurrens mellan skolor – för kvaliténs skull! In A. Lindbom (Ed.), Friskolorna och framtiden – segregation, kostnader och effektivitet (pp. 27–49). Stockholm: Institutet för framtidsstudier.

- Blomqvist, P. (2004). The choice revolution: Privatization of Swedish welfare services in the 1990s. Social Policy & Administration, 38(2), 139–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2004.00382.x

- Blossing, U., Imsen, G., & Moos, L. (2014). The Nordic education model: “A school for all” encounters neo-liberal policy. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Böhlmark, A., & Lindahl, M. (2007). The impact of school choice on pupil achievement, segregation and costs: Swedish evidence (No. 2786). Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

- Böhlmark, A., & Lindahl, M. (2012) Independent schools and long-run educational outcomes: Evidence from Sweden’s large scale voucher reform. Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp6683.pdf

- Böhlmark, A., & Lindahl, M. (2015). Independent schools and long-run educational outcomes: Evidence from Sweden’s large-scale voucher reform. Economica, 82(327), 508–551. doi: 10.1111/ecca.12130

- Bunar, N. (2010). Choosing for quality or inequality: Current perspectives on the implementation of school choice policy in Sweden. Journal of Education Policy, 25(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1080/02680930903377415

- Butler, T., & Hamnett, C. (2010). “You take what you are given”: The limits to parental choice in education in east London. Environment and Planning A, 42(10), 2431–2450. doi: 10.1068/a4323

- Christophers, B. (2013). A monstrous hybrid: The political economy of housing in early twenty-first century Sweden. New Political Economy, 18(6), 885–911. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2012.753521

- Edmark, K., Frölich, M., & Wondratschek, V. (2014). Sweden’s school choice reform and equality of opportunity. Labour Economics, 30, 129–142. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2014.04.008

- Epple, D., & Romano, R. (2012). Economic modeling and analysis of educational vouchers. Annual Review of Economics, 4, 159–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-080511-110900

- Epple, D., Romano, R., & Zimmer, R. (2015). Charter schools: A survey of research on their characteristics and effectiveness. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Forsberg, H. (2015). Kampen om eleverna: Gymnasiefältet och skolmarknadens framväxt i Stockholm, 1987–2011 [The Battle over Pupils: The field of upper secondary education and the emergence of the school market in Stockholm, 1987–2011] (Doctoral thesis). Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

- Friedman, M. (1955). The role of government in education. In R. A. Solo (Ed.), Economics and public interest (pp. 123–144). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Geostar. (2015). Geografisk kontext: Ett nytt sätt att mäta vad omgivningen betyder för individens livsbana [Geographical context: New ways of measuring the significance of surrounding for the life course of individuals]. Retrieved from Statistics Sweden, http://scb.se/mona/

- Glomm, G., Harris, D., & Lo, T.-F. (2005). Charter school location. Economics of Education Review, 24(4), 451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2004.04.011

- Gulosino, C., & d’Entremont, C. (2011). Circles of influence: An analysis of charter school location and racial patterns at varying geographic scales. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 19(8), 1–29. doi: 10.14507/epaa.v19n8.2011

- Holland, R. G. (2003). Voucher lessons from Sweden. Retrieved from https://www.heartland.org/news-opinion/news/voucher-lessons-from-sweden

- Izumi, L. (2009). Op-Ed: Sweden’s choice why the Obama administration should look to Europe for a school voucher program that works. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/video/opinion/1194838660912

- Lakomaa, E. (2011). The municipal takeover of the School system. SSE/EFI Working Paper Series Business Administration, 2.

- Leckie, G., Pillinger, R., Jones, K., & Goldstein, H. (2012). Multilevel modeling of social segregation. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 37(1), 3–30. doi: 10.3102/1076998610394367

- Lindbom, A. (2010). School choice in Sweden: Effects on student performance, school costs, and segregation. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 54(6), 615–630. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2010.522849

- Menard, S. (2000). Coefficients of determination for multiple logistic regression analysis. The American Statistician, 54, 17–24. doi: 10.2307/2685605

- Nicaise, I., Esping-Andersen, G., Pont, B., & Tunstall, P. (2005). Equity in education, thematic review: Sweden. Paris: OECD.

- Noreisch, K. (2007). School catchment area evasion: The case of Berlin, Germany. Journal of Education Policy, 22(1), 69–90. doi: 10.1080/02680930601065759

- Östh, J., Andersson, E., & Malmberg, B. (2013). School choice and increasing performance difference: A counterfactual approach. Urban Studies, 50(2), 407–425. doi: 10.1177/0042098012452322

- Piantadosi, S., Byar, D. P., & Green, S. B. (1988). The ecological fallacy. American Journal of Epidemiology, 127(5), 893–904. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114892

- Reay, D., & Ball, S. J. (1997). Spoilt for choice: The working classes and educational markets. Oxford Review of Education, 23(1), 89–101. doi: 10.1080/0305498970230108

- Regeringskansliet. (2010). Skollag 2010:800 [Education Act]. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Román, H., & Ringarp, J. (2016). 25 år som förändrade skolan: Grundskolans införande 1947–1972 ur ett kommunalt perspektiv [25 years that changed school: A municipality perspective on the establisment of comprehensive education 1947–1972]. Vägval i skolans historia: tidskrift från Föreningen för svensk undervisningshistoria, 16(2).

- Rönnberg, L. (2011). Exploring the intersection of marketisation and central state control through Swedish national school inspection. Education Inquiry, 2(4), 689–707. doi: 10.3402/edui.v2i4.22007

- Sarzosa, M. (2012). Introduction to robust and clustered standard errors. Retrieved from http://econweb.umd.edu/~sarzosa/teach/2/Disc2_Cluster_handout.pdf

- Snijders, T. A., & Bosker, R. J. (2012). Multilevel analysis (2nd ed.). London: SAGE Publications.

- Svanborg-Sjövall, K. (2013). Sweden proves that private profit improves services and influences policy. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/feb/05/sweden-private-profit-improves-services

- The Swedish National Agency for Education. (2016). SIRIS: Internet database. Retrieved from http://siris.skolverket.se/

- The Swedish Schools Inspectorate. (2016, November 18). Skolstart 2016/17. Retrieved from https://www.skolinspektionen.se/skolstart2016-17

- Trumberg, A. (2011). Den delade skolan. Segregationsprocesser i det svenska skolsystemet [Divided schools. Processes of segregation in the Swedish school system] (Doctoral thesis). Örebro University, Örebro.

- Waslander, S., Pater, C., & Weide, M. v. d. (2010). Markets in education: An analytical review of empirical research on market mechanisms in education. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Wiborg, S. (2013). Neo-liberalism and universal state education: The cases of Denmark, Norway and Sweden 1980–2011. Comparative Education, 49(4), 407–423. doi: 10.1080/03050068.2012.700436