ABSTRACT

This article presents a study of how teenage immigrant students, newly arrived in Norway, constructed themselves discursively through a number of identity texts. Drawing on theories from New Literacy Studies, Critical Discourse Analysis, and Social Semiotics, we analyzed a corpus of 97 multimodal identity texts. The study aimed to explore how the students contributed to their personal discursive construction in a society that was new to them. Our study showed that, while struggling with acquiring the dominant language, the immigrant students demonstrated linguistic and semiotic skills and talents. By analyzing the students’ use of linguistic and visual resources, we identified three main categories of identity construction in the students’ texts – spatial identity, relational identity, and functional identity. The analysis suggested that, in their identity work, the immigrant students simultaneously internalized and challenged dominant discourses of the globalized society.

Introduction

In 2015, like in the rest of Europe, the migrant population rose rapidly in Norway. Many migrants came as refugees of war and conflict, and many of the asylum seekers were school-aged children and adolescents (Garvik, Citation2015; Statistics Norway, Citation2019). Newly arrived immigrant students may be defined as children and youths who, due to the short time they have lived in their new home country, have specific educational needs (Dewilde & Kulbrandstad, Citation2016). Most students involved in the present study arrived without parents or other adults taking parental responsibility. Underage immigrants who arrive alone in Norway are considered a particularly vulnerable group. A range of risk factors, such as traumatic experiences, discontinuous school attendance, the lack of a social network, and poor language skills, may influence their physical health and how they function at school (Dewilde & Kulbrandstad, Citation2016, p. 29).

This article is part of a larger project,Footnote1 where the overall objective is to explore how teenage immigrant students not mastering with the dominant language could benefit from utilizing multimodal texts when expressing themselves and their identities. Since these students struggle with the dominant language, they also struggle to express their identity. Based on experiences from previous research (Dávila, Citation2017; Honeyford, Citation2014), we wanted to explore how multimodal ways of expression could benefit them in their attempts to navigate in their new country, in their academic literacies, and in their identity work.

In this article, we analyze what ideas, values, and identities students represent through their multimodal texts. Three research questions have guided the research:

Who or what is represented in students’ multimodal texts?

How are places and objects depicted in students’ multimodal texts?

How are people depicted in students’ multimodal texts?

What kind of identity do students construct through their multimodal texts?

Literature Review

Discourse practices performed through language and other semiotic modes, such as images, contribute to the construction of social identities, “subject positions,” and types of “self” (Fairclough, Citation1992, p. 64). Research in Critical Discourse Analysis over the last decades has typically analyzed how immigrants and other minority groups are represented in institutional discourse, especially in media texts. Studies from various European countries have shown that the media often represent minority groups in stereotypical and even negative ways. In a review of international research on the representation of minority groups, Lirola (Citation2014, p. 483) presented the main finding that immigrants and other minority groups are represented as “the others” in the literature, different from the majority. Several analyses have shown that newspaper images typically depict immigrants as passive and not performing any actions, with immigrants and minorities frequently portrayed as groups, as if they do not have any individual identity (KhosraviNik, Citation2009; van Dijk, Citation1991). Other studies have observed that anti- and pro-immigration debates often refer to “immigrant” and “immigration” in essentialist and dichotomous terms, and schools perpetuate colonialist discourses of assimilation and socialization (Honeyford, Citation2014, pp. 197–198).

Despite the existence of such dominant discourses on immigration, previous research has also shown that educators can contribute to the creation of spaces where immigrant students can challenge dominant discourses and articulate self-representations. Identity texts can serve as powerful tools in enabling students from marginalized social backgrounds to develop various linguistic, artistic, multimodal, and intellectual talents (Cummins et al., Citation2015; Cummins & Early, Citation2011; Honeyford, Citation2014). The production of identity texts can also function as a type of counter-discourse to the implicit devaluation of marginalized students’ abilities, languages, cultures, and identities. A counter-discourse can be understood as a way of challenging established meaning, “leaving space for alternative representations to shift into the mainstream space” (Macgilchrist, Citation2007, p. 75). The concept of an identity text Footnote2 was developed by Canadian literacy researchers, and it is used to describe “the products of students’ creative work or performances carried out within the pedagogical space orchestrated by the classroom teacher” (Cummins & Early, Citation2011, pp. 3–4). Case studies from various countries worldwide have documented how students and teachers in multilingual schools work with identity texts (Cummins & Early, Citation2011). Most studies focus on various pedagogical approaches to creative work with identity texts. However, the meaning potential of the texts created by students from marginalized groups has been less explored. Among the rather few examples, Archakis (Citation2014) examined how, in their school essays, immigrant students positioned themselves against the racist discourse in their new home country, Greece. Although these immigrant students had been through an assimilation process, they still expressed bonds to their homeland. Archakis (Citation2014, p. 312) interpreted these findings by suggesting that the immigrants were adopting a broader identity.

In an ethnographic case study, Honeyford (Citation2014) analyzed presentations of transcultural identity in the photo essays of students with a Mexican background living in Canada. This study especially focused on which discourses of immigration the students drew on and how the students expressed power through multimodal texts. The study’s main finding was that the students created new and unexpected ways of representing their identities, through multimodal ways of working.

A Swedish study of newly arrived immigrant students’ language learning confirmed the advantages of developing creative literacy practices for this group of students (Dávila, Citation2017). This study called attention to how students who are newcomers are often placed in linguistically isolated classrooms, suggesting that multimodal and multilingual literacy practices could give these students valuable literacy experiences (Dávila, Citation2017). In the tradition of critical literacy, research has been conducted on the textual productions of students belonging to minority groups, such as immigrants and indigenous people (Janks, Citation2010; Luke, Citation2000; Mills et al., Citation2016). Most of these studies have referred to societies in Australia, Canada, and South Africa; however, Europe, especially Northern Europe, seems to be underrepresented in the research. Each country offers different contexts of reception for immigrants in terms of availability of social support in a receiving community, degree of openness, acceptance, and so on (Portes & Rumbaut, Citation2014). In general, Norwegian research on newly arrived immigrant students is limited. As pointed out by Dewilde and Kulbrandstad (Citation2016), most research so far has focused on second language (L2) learning, while few studies have explored the situation of newly arrived immigrant students. This study aims to contribute to insight both in terms of how young immigrants see themselves and how the creation of multimodal texts can invoke literacy engagement and make students’ identities visible in and outside class.

Background and Presentation of Data

According to the Norwegian Law of Education, newly arrived children and youth have the right to education depending on their age and legal status (Opplæringslova [Education Act], Citation1998). All young people aged 16–18 years who have completed compulsory school have the right to attend upper secondary school. With some restrictions, these rights also include individuals who are seeking asylum. Young immigrants aged 16–18 years who come to Norway without nine years of primary and lower secondary school have the right to receive education that is comparable to compulsory schooling. However, immigrant and refugee students who are placed in separate intensive classes before the transition to mainstream classrooms risk being linguistically isolated, meaning that few individuals in the environment speak the dominant national language (Dávila, Citation2017, p. 2). In addition, school attendance could be challenging for this group of students, especially youths who arrive in a new home country late in their school careers and have had few or poor experiences of attending school (Dewilde & Kulbrandstad, Citation2016, p. 14). Norwegian municipalities may offer immigrant education at separate adult educational centers, but for teenage students, it is often demotivating to study in classes with adults much older than they are. For that reason, some Norwegian municipalities offer teenage immigrant students alternative schooling. The aim of such an education program is qualifying these students for ordinary upper secondary schooling.

For the project presented in this article, we recruited students from a school for teenage immigrant students through contact with local education authorities. The municipality was highly responsive to our suggested research project from the beginning; it had been searching for initiatives adapted for this group of underage immigrants. The project included two classes of immigrant students aged 16–19 years, three teachers, and two teaching assistants. A total of 23 students participated in the project, comprising 20 male and 3 female students. Most of the youths came to Norway in 2015 or later. Their home countries were Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia, Eritrea, Kosovo, and El Salvador. The students had oral communication skills in various languages, such as Arabic, Pashto, and Spanish. Their writing skills in the first language (L1) varied.

In this article, we present findings from the analysis of a corpus of 97 multimodal texts made by the 23 newly arrived immigrant students. The texts are photos the students took with their mobile devices, as well as short captions written in the dominant language. The project also generated other kinds of data, such as notes from planning meetings and observations. Analysis of such data is not included in this article, since these data did not provide extended knowledge to the analysis of the students’ texts.

Theoretical Frame: Critical Literacy and Self-representation

This study drew on theories from New Literacy Studies (Cope & Kalantzis, Citation2000; Heath & Street, Citation2008), critical literacy (Janks, Citation2010; Luke, Citation2000), Critical Discourse Analysis (Fairclough, Citation1992; van Leeuwen, Citation2008), and multimodal literacy (Jewitt & Kress, Citation2003). Nearly two decades ago, the New London Group called for a new pedagogy, challenging the existing formalized, monolingual, and monocultural literacy pedagogy. The concept of “multiliteracies” was meant to respond to two important tendencies in society. First, the new literacy pedagogy needed to consider society’s increasing cultural and linguistic diversity. Second, it needed to include more forms of representations and textual forms associated with multimedia technologies. The group encouraged cross-cultural communication and productive diversity (The New London Group, Citation2000). A multimodal approach to learning implies awareness of how various modes,Footnote3 such as writing and images, could be included and contribute to meaning making in communication. Multimodal approaches offer new ways of exploring and understanding language and placing it in a multimodal communicational landscape (Jewitt, Citation2017; Kress & Jewitt, Citation2003).

According to Janks (Citation2010, p. 188), not only are students constructed by the social, but they can also take part in its construction. This assumption refers to Fairclough’s (Citation1992, p. 12) notion of a dialectical relationship between texts and society: Discourse is shaped by power relations and has constructive effects on social identities and relations. This implies that students can contribute to social action and change through their work with texts (Janks, Citation2010). In the framework of critical literacy, students’ possibilities for agency are emphasized, and their identities and experiences are seen as a learning resource (Cummins & Early, Citation2011, p. 161; Honeyford, Citation2014, p. 196). It is crucial for all students living in democratic societies to understand how language is used to achieve social goals. Encouraging students to express their agency and identity in texts is a way of emphasizing their power (Cummins & Early, Citation2011, p. 32).

Our detailed analysis of multimodal texts created by newly arrived immigrant students draws on theories of Multimodal Critical Discourse Studies (Machin, Citation2013; van Leeuwen, Citation2013). Critical analysis of discourse has traditionally examined institutional texts, focusing on how people are categorized in various texts, such as newspapers, in a given culture or society (Fairclough, Citation1995; van Leeuwen, Citation2008). Modes like images are included in Multimodal Critical Discourse Studies. As we based the analysis on tools from Social Semiotics and Critical Discourse Analysis, we were interested in which discourses the immigrant students drew on and how they positioned themselves through their multimodal texts (Honeyford, Citation2014, p. 208).

Research Method and Design

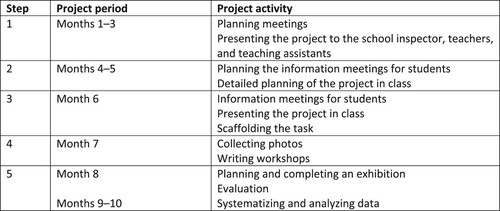

This research project was conducted in two classes at a school for immigrant students in a small townFootnote4 in southeast Norway. The overall project was intervention based. The planning and conducting of the research involved close collaboration with the school inspector, teachers, and teaching assistants,Footnote5 and the project was adapted to the ordinary timetable of the students’ education. The three researchers taking part in the project visited the school several times over eight months. The project was organized in five steps, delineated below.

At the start of the project, the school inspector explained that most of the students were alone in their new home country, living away from their parents and families. Most had limited experience of being a student. The students had no common language to use in class except the dominant language, of which they had limited or extremely poor knowledge. Due to these challenging learning conditions, the school inspector emphasized the students’ motivation and understanding of the project’s aim as critical. However, she believed in the idea of using multimodal identity texts as a learning resource.

During the information meetings (see ), we introduced an open task to the students asking them to reflect on who they were and what was important for them in their daily lives. The researchers showed students some scaffolding examples of possible ways of solving the task. Teaching assistants who could translate information to students with extremely poor knowledge of Norwegian took part in all the meetings. The students were then encouraged to share five photos each, shot with their mobile devices. In the writing workshops, the students wrote a brief caption for each photo, supported by the teachers and teacher assistants. The questions that the students were encouraged to explore, both in images and writing, were articulated in a simple way: Who am I? What is important to me? The aim was to affirm the students’ identity and evoke their literacy engagement (Cummins et al., Citation2015).

Due to economic and technical limitations, and because the students were struggling with the dominant language, the researchers and teachers decided to choose a relatively simple research design requiring minimal digital and technical resources. After the photo collection and writing workshops, in collaboration with the teachers and assistants, the researchers organized an exhibition at the school to present a sample of the students’ multimodal identity texts to an invited audience. This idea relied on the understanding that discourse has constructive effects, and that this group of students needed to express their visibility in a context outside the classroom (Janks, Citation2010; Luke, Citation2000).

Ethical Perspectives

The project was approved by data protection services at the Norwegian Centre for Research Data. All data were anonymized and treated according to the guidelines of this center (Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Citation2018). The students were informed that their participation in the project was voluntary. Only a few refused to take part. The photos in this article have been anonymized, and they are reproduced with the permission of the photographers.

Analytical Approach

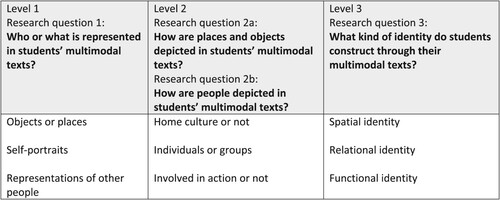

Since the images were most salient in the students’ multimodal texts, visual meaning was given priority in the analysis. By analyzing photos in terms of social semiotics, we may identify what ideas, values, and identities these texts represent. As the students struggled with the dominant language, the visual meaning facilitated their potential for agency. The visual mode allowed them to express their opinions, feelings, and identity without requiring complicated vocabulary and grammatical structures in their new language. However, the captions that the students were encouraged to write gave linguistic training in the new language and contributed to limiting and expanding the interpretation of the images’ meanings. The analysis of the students’ multimodal texts was carried out at three levels corresponding to the three research questions (see ).

At level 1, we categorized all the images in the data corpus according to who and what was represented in the images. At level 2, we performed a closer analysis of the images in the data corpus. Drawing on theories from Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012; van Leeuwen, Citation2008), we especially focused on the connotative and symbolic meanings of the depicted objects and spaces. We also identified whether the students foregrounded objects or places with explicit reference to their home culture. Further, we analyzed whether the students depicted themselves as individuals or members of a group and if they were involved in an action. At level 3, we interpreted the possible meanings of identity that the students expressed through their multimodal texts.

To explore and understand how the students defined their identities, we drew on van Leeuwen’s (Citation2008) theories of discursive constructions. However, while van Leeuwen’s theories refer to different strategies for representing people as “others,” our analysis explored how these students constructed themselves. We identified three forms of possible identity types in the data material, namely, spatial, relational, and functional identity. Footnote6

Spatial identity occurred in multimodal texts when the students visually and linguistically emphasized their relation to a specific place or location. Critical Discourse Analysis underlines that space is socially constructed, shapes behavior, and signifies symbolic meaning (Ledin & Machin, Citation2018, p. 110; van Leeuwen, Citation2008, pp. 95–98). Both internal and external spaces, inside and outside buildings, contribute to socially constructed meaning (van Leeuwen, Citation2008, p. 88). Spatial discourse can contribute to construction of identity, in terms of signifying what roles individuals can take up, relating to such questions as “who can I be in this place?” and “how does this place make me feel?” (Ravelli & McMurtrie, Citation2015, p. 51). If an image depicts an environment without any human beings, objects become especially important. The objects may function in symbolic ways, connoting positive or negative values and associations (Machin, Citation2011, pp. 32–33; van Leeuwen, Citation2008, p. 144). If specific objects are made salient, achieved by foregrounding or exaggerating the size, the object is given symbolic status (Fawzy, Citation2018, p. 12; Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2006, p. 108).

Relational identity arose in the texts when the students focused on themselves in relation to other people. In multimodal texts, it is possible to express interpersonal relations visually, for instance, by depicting people together in a group, and linguistically, with nouns denoting relations like “mother,” “friend,” or “colleague.” Relational identifications are also realized by a possessive pronoun, signifying how social actors belong together, as in, “my mother” or “my friend” (van Leeuwen, Citation2008, pp. 42–43).

Functional identity occurred in texts when the students represented themselves as involved in an activity, emphasizing what they did. In images, people may be depicted as involved in action (narrative representation) or not (static representation). The roles in which people are depicted may have various symbolic meanings. In narrative representations, the actors are defined symbolically as “agents,” the “doers” of an action (van Leeuwen, Citation2008, pp. 142–144). Below, the results of the analysis are presented in detail.

Results

Level 1: Who or What is Represented in Students’ Multimodal Texts?

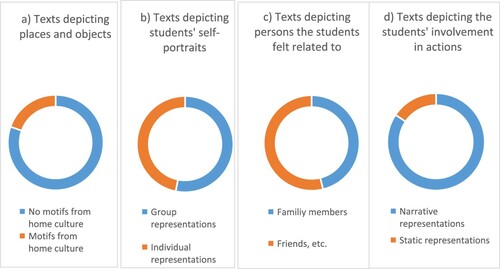

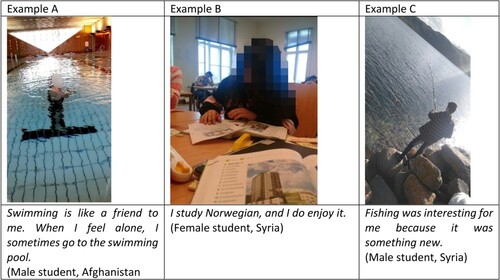

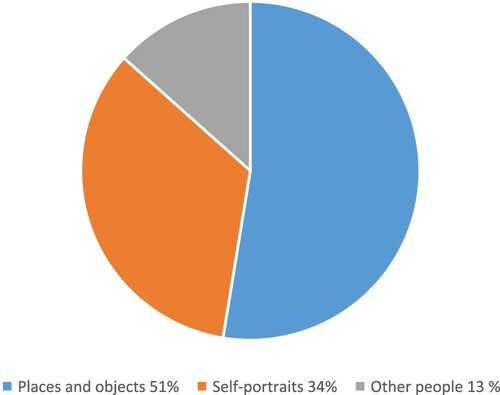

We identified three main categories of motifs in the students’ 97 multimodal texts. The first category covered multimodal texts that represented places and objects, the second covered self-portraits, and the third covered texts that represented other people like the students’ family and friends (see ).

Figure 3. Percentage distribution of who and what is represented in the newly arrived immigrant students’ multimodal texts.

The largest category foregrounded places and objects. The second category comprised self-portraits, images that depicted the student’s face or body. The third and smallest category of texts depicted people to whom the student felt some kind of relation.

Level 2: How are Places, Objects, and People Depicted in the Students’ Texts?

At this level of analysis, we explored each textual category more closely in terms of how the students’ multimodal texts depicted places, objects, and people. The figures below give an overview of the findings. (a) illustrates how much the students emphasized places and objects from their home culture. (b) depicts whether the students represented themselves in a group or alone. (c) shows what types of relations students emphasized, and (d) presents the roles in which the students depicted themselves. We present and discuss some concrete examples of these findings below.

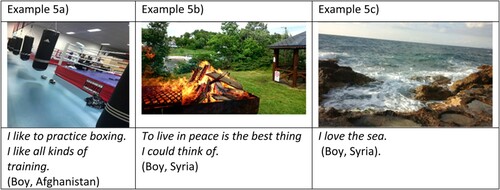

Texts Foregrounding Spaces and Objects

Most of the students’ images depicted places or objects (see ). The students represented spaces they connected with various positive activities, for instance, school as a place for studying and sport centers as places for practicing sport (see Example A in below). One student from Afghanistan shared an image of his Norwegian school and wrote the caption: “In most poor countries, people have no right to go to school, especially not women. In Norway, everybody has the right to go to school, and I really enjoy it.”Footnote7 Another student from Afghanistan shared an image of the environment near his Norwegian school and wrote: “This is the area around my school. I am fond of this area, and I am fond of my school. To attend school is important for me. This is a historic area and I feel at home here.”

The students often chose to represent Norwegian landscapes. Via the short captions, they expressed how they engaged in the spaces and how the landscapes made them feel. When the students referred to images that depicted landscapes, they often emphasized positive values, such as peace, freedom, and happiness. One student from Eritrea wrote: “I love to be in nature. It feels enjoyable and nice to be alone. In nature, you do not feel lonely.” The students also expressed their passion for natural phenomena, as in, “Snow is my favorite weather” or “I love the sea.” Examples A, B, and C in show three students’ representations of spaces.

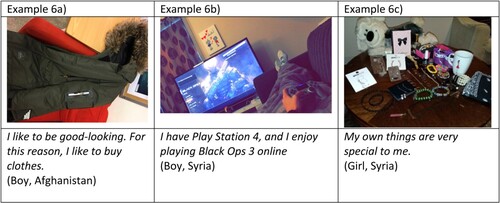

In some of the other texts, the students chose to emphasize specific objects that were important to them: “The mobile phone is one of my most important things,” a student from Afghanistan wrote: “I have PlayStation 4, and I enjoy playing Black Ops 3 online,” expressed a student from Syria (see , Example B). We have interpreted these objects (as shown in ) as attributes that connote a materialistic, technological, and globalized youth culture. Such objects can also express relational identity and the ways in which relationships are mediated by technology. The reason for this interpretation is that data games and mobile phones can be understood as phenomena that connote status within a youth culture. By owning such objects, the youths express their materialistic status. By playing computer games, they take part in the globalized culture of data gaming, as well as showing their gaming competence.

When we analyzed texts in the category of places and objects, we tried to identify whether the motifs could be associated with students’ home cultures. We found that rather few students expressed values directly associated with their home cultures (see (a)).

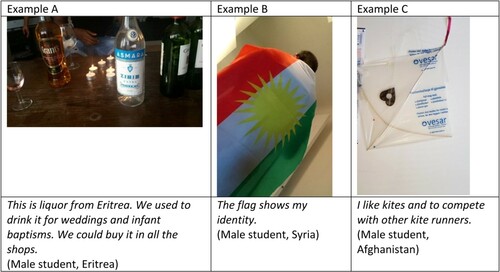

In , Example A (below), we see how a student chose to depict a bottle of alcohol from his home country, Eritrea. In the caption, the student explained how the liquor was associated with festive days like weddings or infant baptisms. The comment, “We could buy it [alcohol] in all shops,” indirectly underlines the difference between Eritrea and his new home country. In Norway, the sale of alcoholic liquors is strictly regulated and only possible in specific shops. In , Example B, another student expressed his home culture visually by showing himself wrapped in the Kurdish flag and verbally with the caption, “The flag shows my identity.” The flag is a symbolic attribute of the collective values of the Kurdish people. A Somalian student shared an image of a table covered with food and wrote in the caption, “This food is important to me since it represents Somalian food traditions.” One possible interpretation of Example C () is to see it as an illustration of how an immigrant student brought knowledge and traditional cultural values with him from his home country, Afghanistan, to his host country. This image depicts an Afghan kite made of a Norwegian bin liner. In the caption, the student expresses his affection for kite running: “I like kites and to compete with other kite runners.”

Texts Foregrounding People and Relations

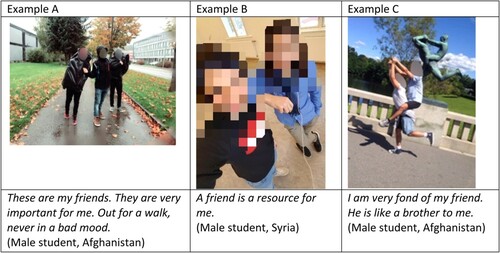

In the analysis of students’ self-portraits, we explored whether the students represented themselves visually alone or in a group. As shown in (b) (above), the students often depicted themselves with other people (group representation). In these images, the students emphasized being with friends, classmates, teammates, or family (see examples in ).

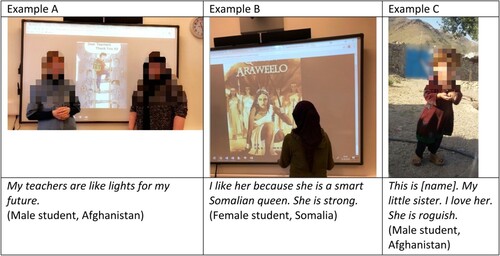

Some students’ images were not self-portraits, but instead, depicted people to whom the students felt related. As shown in (c) (above), we identified two types of these images. Most images in this category represented persons the students had some kind of relation to, such as teachers, idols, and movie stars. The remainder represented family members (see ). The students’ relational identifications typically involved expressions like “my friends,” “my teachers,” and “my little sister” (see examples in above and 9 below).

In most of the images, the students depicted themselves performing some kind of act (see (d)). The students emphasized various sport activities they enjoyed, such as swimming, riding, or hiking. Other represented activities were cooking, drawing, fishing, and playing cards (see examples in ).

In some of the texts, the students provided reasons for why they liked a specific activity: A student from Afghanistan wrote, “Swimming is like a friend to me. When I feel alone, I sometimes go to the swimming pool” (see , Example A). Another student from Afghanistan wrote: “I really like cooking. I like when people express their thanks. I would like to be a cook.”

Level 3: What Kinds of Identities do Students Construct Through Their Multimodal Texts?

We found that the immigrant students constructed themselves via three ideal types of identity texts, which we refer to as spatial, relational, and functional identity. In this grouping of the students’ texts, we drew on van Leeuwen’s theories of visual and linguistic representation of social actors. We defined the three types of identity texts as ideal types and not necessarily mutually exclusive. In some instances, the classification of the students’ texts was not obvious, and some texts fit several categories (see examples below). However, we tried to make the analysis as precise and transparent as possible.

Spatial identity occurred when the students depicted space and buildings as salient motifs. As shown above, the students often emphasized their relation to a specific place – a building or location, for instance, a boxing hall, garden, or place near the sea (see examples in ). We also included texts that depicted objects in this category. We found that the youths often foregrounded everyday objects like clothes, jewelry, and computer games (see examples in ). We identified some motifs from the students’ home culture, for instance, a Kurdish flag or Afghan kite (see ), but such examples were not frequent in the data material (see also (a)). When the project took place, the students had lived in Norway for only a short time. Since place and objects are powerfully connected to individual and collective memory (Mills et al., Citation2016, p. 8), it was interesting to observe how the past was nearly absent in most of the students’ identity texts. One reason for this finding may be that buildings and objects from the students’ homes were not accessible. Another explanation could be that most of the students did not want to focus on what they had left behind.

Relational identity occurred when the students depicted one or several persons in their texts and focused on interpersonal relations. Most images in this category were self-portraits, in which the students had included friends, classmates, family members, and teachers. In the captions, the students emphasized how important these interpersonal relations were to them (see examples in and ). Considering that most of these students came to their host country alone, without any family or friends, it was interesting to observe how the young immigrants emphasized their collective identity in many texts. The students focused on personal kinship by representing themselves as a part of a family or a group (van Leeuwen, Citation2008, pp. 42–43).

Functional identity occurred when the students chose to depict themselves as involved in actions. When we analyzed agency in the students’ self-portraits, we identified who did what and what was done (Machin, Citation2011, p. 123). We found that, in most of these texts, the students depicted themselves as active (narrative representations; see (d)). By representing themselves taking part in various kinds of activities, such as swimming, studying, or fishing (see examples in ), the students clearly defined themselves in terms of their function and symbolically represented themselves as “doers” (van Leeuwen, Citation2008, p. 143). In this last category, we could also have included texts in which the students represented their agency more implicitly, through representations of attributes or places that connote activity (e.g., the representation of the boxing hall in , Example A, or computer game in , Example B).

Discussion: Immigrant Students’ Multimodal Texts as Counter-discourse

The overall objective of this study was exploring how newly arrived immigrant students who were struggling with the dominant language in their new society could benefit from utilizing multimodal texts when expressing their identities. As mentioned above, most of the youths in our study were underage immigrants who arrived in Norway alone and had specific educational needs. The intention was to encourage these teenagers to use their identity as a resource for learning (Cummins & Early, Citation2011; Honeyford, Citation2014). Based on a close analysis of a corpus of 97 multimodal texts, we identified how the youths constructed themselves in three ideal types of identity texts. In this project, we did not explicitly thematize questions regarding existing discourses of immigrants and immigration for the students. However, the study demonstrated that, through their identity texts, the youths could challenge some of the stereotypical discourses about immigrants.

First, in spatial identity texts, we found that several students expressed their affection for local places and environments in their host country, Norway. As newly arrived immigrants, these students had left their home countries. They had experienced being homeless, and they were trying to settle down in a new place. Through their spatial identity texts, the students expressed power by stating their belonging and positioning themselves as integrated actors in their new community. We also found that objects from a globalized youth culture were salient in the students’ texts. Like all young people, they were interested in new technology, games, and fashion. In a minority of the texts, the students foregrounded motifs that they explicitly connected to their home culture.Footnote8 We interpreted these findings as an indication of how the students negotiated their changing identity, and more indirectly, challenged a dominant discourse representing immigrants as “different” or “other.”

Second, in relational identity texts, we identified how the students represented themselves with friends, family, and teachers. Some of the texts exclusively represented persons to whom the students felt related (see (b and c) above). Like many newly arrived language minority students, the participants were placed in separate intensive language classes, and they were linguistically isolated (Dávila, Citation2017). However, through their multimodal identity texts, the students showed that they were able to establish new social networks. By shooting and sharing self-portraits, “selfies,” the immigrant students also demonstrated that they were taking part in a common, globalized discourse practice (Lüders, Citation2008). While several studies have shown that collective self-portraits are rare when youths share selfies online (Schwarz, Citation2010; Veum & Undrum, Citation2018), many of the immigrant students’ self-portraits emphasized interpersonal relations.

Third, in functional identity texts, we found that the students tended to represent themselves as “doers.” By representing themselves taking part in various kinds of activity, the students expressed agency and power (Cummins & Early, Citation2011), and indirectly, they challenged stereotypical discourses of passive immigrants (Lirola, Citation2014). To summarize, our analysis suggested that, in their identity work, the immigrant students seemed to both internalize and challenge dominant discourses of the globalized society.

This study had some limitations. It was limited to the analysis of 97 multimodal texts produced by 23 newly arrived immigrant students in a particular school. The presented findings were results from close analysis of the students’ texts. Based on the methodological principles of discourse analysis, we sought to make the research procedure as explicit and transparent as possible so that our operationalization and interpretations would be traceable and understandable (Wodak, Citation2006, p. 609). However, cases of doubt did occur, and in some cases, alternative interpretations could have been possible. Moreover, the scaffolding examples, introduced by the researchers and teacher assistants at the beginning of the project, could have shaped the kinds of images the youths produced.Footnote9 The students chose not to depict themselves, or any human being, in most of the texts. This may have resulted from how the project was framed by the researchers. At the start of the project, all the students were informed that they did not have to share images depicting themselves, their body, or their face. This information was important to communicate for ethical reasons. The contextual frame could clearly have had an influence on the level of self-exposure in the texts. In contrast, the framing could also have worked as a fruitful challenge for finding alternative and creative ways of representing identity.

Despite these limitations, this study’s findings have several implications for pedagogy and studies of language and literacy education for newly arrived immigrants. It confirmed findings from previous research indicating that newly arrived immigrant students who have received little or no formal schooling in their countries of origin could benefit from developing creative and multimodal literacy practices (Dávila, Citation2017). Further, the study demonstrated the advantage of choosing a simple pedagogical approach and drawing on the immigrant students’ interests and experiences when working with identity texts. We experienced that continuous support and attention from the teachers was crucial for this group of students, as was the involvement of bilingual teacher assistants. The two teacher assistants involved in our project contributed not only as translators but also as motivators and role models. The teacher assistants were young people with similar backgrounds, and many of the students could easily identify with them. The process of motivating through scaffolding examples was another crucial aspect. At the beginning of the project, the three researchers demonstrated possible ways of solving the task. Because many of these students struggled with personal challenges in their daily lives, the school inspector was worried that they would not be motivated for participating. She encouraged one of the teacher assistants to create multimodal identity texts and present them to the students. Since the teacher assistant was an immigrant, his presentation had an extra motivating effect on the students. During the project, the teachers faced some challenges. For instance, some students did not attend all the workshops. The teachers were patient; they kept encouraging the students and offered extra and individual support. Ultimately, all the students managed to share their photos and write captions in the dominant language.

This study also confirmed previous research by suggesting that identity-affirming literacy practices are likely to increase students’ literacy engagement (Cummins et al., Citation2015). The last part of the project, where the students’ texts were presented to a broader audience in an exhibition, was particularly important. A number of Norwegian students, immigrant students from other schools, teachers, and members of the community board were invited to view the presentation of the students’ texts. Most of the immigrant students had not had experience with such an exhibition, and when they saw their photos enlarged and hanging on the walls with the captions they had written in the dominant language, they were proud and excited. When the audience arrived, the students stood in front of the texts they had created, and their texts functioned as a starting point for conversations with the audience. At the exhibition, the students had the chance to explain and elaborate on the meaning potential of their texts, allowing them to practice in the dominant language. The exhibition demonstrated to the students, as well as their audience, that it is possible to construct oneself discursively, and thus, express visibility in a context outside the classroom (Janks, Citation2010; Luke, Citation2000). The study of the newly arrived immigrants’ texts offers some insights that can hopefully contribute to a better understanding of young immigrants’ ways of shaping their identities in a new setting.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank the participants for taking part in the project and sharing their multimodal texts. We also thank the school inspector, teachers, and teaching assistants at our partner school for their contribution and kind and enthusiastic collaboration.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Project title: Multimodal literacy in the multicultural classroom. The project was funded by grants from the University of South-Eastern Norway and led by Associate Professor Aslaug Veum.

2 Cummins and Early (Citation2011) described identity texts as follows: “Students invest their identities in creation of these texts – which can be written, spoken, signed, visual, musical, dramatic, or combinations in multimodal form. The identity text then holds a mirror up to students in which their identities are reflected back in a positive form. When students share identity texts with multiple audiences … , they are likely to receive positive feedback and affirmation of self in interaction with these audiences” (p. 3).

3 All modes consist of sets of semiotic resources. Examples of semiotic resources of visual modes like photographs are gaze, setting, and angle (Jewitt, Citation2017; Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2006).

4 The town has approximately 50,000 inhabitants.

5 The teacher assistants were bilingual, one in Arabic and Norwegian and the other in Pashto and Norwegian.

6 The categories functional and relational identity are inspired by van Leeuwen’s (Citation2008, p. 42) distinction between two key types of categorization—functionalization and identification.

7 The students’ captions were translated from Norwegian to English by the researchers. Although most students did not write exact Norwegian, we have corrected students’ grammar and spelling in the English versions of the captions.

8 However, this finding does not indicate that we consider the terms “home culture” and “globalized culture” to be dichotomous. We are also aware of the possibility that the students’ chosen motifs could have been influenced by how the project was framed. See the discussion at the end of the article.

9 We discussed this risk when we planned the project design, and after careful consideration, we decided that the benefits of scaffolding would exceed the disadvantages.

References

- Archakis, A. (2014). Immigrant voices in students’ essay texts: Between assimilation and pride. Discourse & Society, 25(3), 297–314. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926513519539

- Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. Routledge.

- Cummins, J., & Early, M. (Eds.). (2011). Identity texts: The Collaborative creation of power in multilingual schools. Institute of Education Press.

- Cummins, J., Hu, S., Markus, P., & Montero, K. M. (2015). Identity texts and academic Achievement: Connecting the Dots in multilingual school contexts. TESOL Quarterly, 49(3), 555–581. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.241

- Dávila, L. T. (2017). Newly arrived imiigrant youth in Sweden negotiate identity, language & literacy. System, 67(2017), 1–11. www.elsevier.com/locate/system https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.04.001

- Dewilde, J., & Kulbrandstad, L. A. (2016). Nyankomne barn og unge i den norske utdanningskonteksten [Newly arrived children and youths in the Norwegian educational context]. Nordand. Nordisk tidsskrift for andrespråksforskning, 11(1), 13–33.

- Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Polity Press.

- Fairclough, N. (1995). Media discourse. Edvard Arnold.

- Fawzy, R. M. (2018). A tale of two squares: Spatial iconization of the Al Tahrir and Rabaa protests. Visual Communication, 8(1), 35–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357218803395

- Garvik, O. (2015). Asylsituasjonen i Norge 2015 og 2016. Store norske leksikon (encyclopedia). https://snl.no/asylsituasjonen_i_Norge_2015_og_2016

- Heath, S., & Street, B. (2008). On ethnography: Approaches to language and literacy research. Teachers College Press.

- Honeyford, M. A. (2014). From Aquí and Allá : Symbolic Convergence in the Multimodal Literacy Practices of Adolescent Immigrant Students. Journal of Literacy Research, 46(2), 194–233. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X14534180

- Janks, H. (2010). Literacy and power. Routledge.

- Jewitt, C. (2017). Introduction. In C. Jewitt (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis (2 ed., pp. 1–7). Routledge. Tylor & Francis Group.

- Jewitt, C., & Kress, G. (2003). A multimodal approach to research in education. In S. Goodman, T. Lillis, J. Maybin, & N. Mercer (Eds.), Language, literacy and education: A reader (pp. 277–292). Trentham Books in association with the Open University.

- KhosraviNik, M. (2009). The representation of refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants in British newspapers during the Balkan conflict (1999) and the British general election (2005). Discourse and Society, 20(4), 477–498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926509104024

- Kress, G., & Jewitt, C. (2003). Multimodal literacy (Vol. 4). Peter Lang.

- Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. Routledge.

- Ledin, P., & Machin, D. (2018). Doing visual analysis. Sage.

- Lirola, M. M. (2014). Approaching the representation of Sub-Saharan immigrants in a sample from the spanish press. Deconstructing Stereotypes Critical Discourse Studies, 11(4), 482–499. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2014.915382

- Lüders, M. (2008). Conceptualizing personal media. New Media & Society, 10(5), 683–702. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444808094352

- Luke, A. (2000). Critical literacy in Australia: A Matter of context and standpoint. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 43(5), 448–461.

- Macgilchrist, F. (2007). Positive discourse analysis: Contesting dominant discourses by Reframing the Issues. Critical Approaches to Discourse Analysis Across Disciplines, 1(1), 74–94.

- Machin, D. (2011). Introduction to multimodal analysis. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Machin, D. (2013). What is multimodal critical discourse studies? Critical Discourse Studies, 10(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2013.813770

- Machin, D., & Mayr, A. (2012). How to do critical discourse analysis: A multimodal introduction. Sage.

- Mills, K. A., Davis-Warra, J., Sewell, M., & Anderson, M. (2016). Indigenous ways with literacies: Transgenerational, multimodal, placed, and collective. Language and Education, 30(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2015.1069836

- The New London Group. (2000). A pedagogy of multiliteracies designing social futures. In B. Cope, & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies. Literacy learning and the design of social futures (pp. 9–37). Routhledge.

- Norwegian Centre for Research Data. (2018). Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Data protection services. https://nsd.no/personvernombud/en/index.html

- Opplæringslova [Education Act]. (1998). Lov om grunnskolen og den vidaregåande opplæringa (opplæringslova) [the Education Act]. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1998-07-17-61

- Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2014). Immigrant America: A Portrait (4 ed.). University of California Press.

- Ravelli, L. J., & McMurtrie, R. J. (2015). Multimodality in the Built environment: Spatial discourse analysis. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Schwarz, O. (2010). On friendship, boobs and the logic catalogue: Online self-portraits as a means for the change of capital. Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies, 16(2), 163–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856509357582

- Statistics Norway. (2019). Stor nedgang i antall flyktninger. https://www.ssb.no/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/stor-nedgang-i-antall-flyktninger

- van Dijk, T. (1991). Racism and the press. Routledge.

- van Leeuwen, T. (2008). Discourse and practice: New tools for critical discourse analysis. Oxford University Press.

- van Leeuwen, T. (2013). Critical analysis of multimodal discourse. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of applied lingusitics (Vol. 10, pp. 1–5). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Veum, A., & Undrum, L. V. M. (2018). The selfie as a global discourse. Discourse & Society, 29(1), 86–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926517725979

- Wodak, R. (2006). Dilemmas of discourse (analysis). Language in Society, 35(4), 595–611. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S004740450606026X