ABSTRACT

In this article, a study of combined discursive emphasis on the concepts “culture for learning” and “learning outcomes” in recent education policy messages is presented. These concepts have been individually examined but seldom as parallel or converging policy messages. Inspired by discursive institutionalism, we address the policy framing of a 14-year period of intense education reform with Norway as an example. Findings indicate that the key concept of the reform culture-for-learning policy idea functioned as a buzzword for a shorter time, gaining public acceptance of the new reform, while the more concrete learning-outcomes policy idea rooted. Both ideas were presented as solutions to perceived problems in schools due to unsatisfactory PISA results and the emerging globalization of educational policies. This study highlights the roles of concepts and ideas in educational governance and how these roles can be factors in reform success or failure. It is beneficial if the new policy is in a chain of equivalence with other concepts.

Introduction

Educational policy initiatives are frequently presented with catchy concepts like “lifelong learning” (OECD, Citation2000b), “learning society” (OECD, Citation2000a), and “learners for life” (OECD, Citation2003). Sometimes such words take the form of being buzzwords – pleasant-sounding concepts or phrases offering a sense of direction and legitimacy that policy actors use to justify policy change or new ideas (Cornwall & Brock, Citation2005; Godin, Citation2006). As such, certain words play a key role in the framing process of policy problems to be solved and their solutions (Schmidt, Citation2008). Ideas have increasingly been recognized as major factors and a primary foundation of political behavior that shape and frame how political problems are understood and define goals and strategies (Béland & Cox, Citation2011). Key ideas are foregrounded and restricted by policy actors in discourse to impact ways of seeing or thinking about a policy issue (Arnott & Ozga, Citation2010). Concepts can be considered central parts of discourses that form key elements in the dynamics of policy change and reform, and discourse can be studied as interactive processes of conveying ideas (Schmidt, Citation2008, p. 303). Buzzwords have been recognized as concepts or phrases that only become prevalent for a shorter time (Godin, Citation2006, p. 24), and although they are not without meaning, they are often hard to define precisely (Scudellari, Citation2017). Loosely defined policy messages often leave the complex processes of concretization to be solved by practitioners (Hargreaves & Moore, Citation2000; Prøitz, Citation2010). Consequently, a study of defining education reform concepts and ideas seems appropriate.

With this paper, we aim to provide an expanded understanding of the framing of policy problems and solutions defined by the use of key concepts in governance, exemplified by the high-profile concepts of culture for learning and learning outcomes in the Norwegian setting. We have examined the evolution of high-profile concepts used in a period of comprehensive education reform.Footnote1 By tracing announced policy key concepts over a reform-intensive period of 14 years, the study enables an exploration and display of how certain and more publicly likeable concepts are used in the initial reform years, while other, potentially more controversial concepts characteristic of the core essence of reform seem explicated in later reform years before they take over the policy framing of ongoing education policy developments. This study shows how certain concepts can open the door for new policy by being ideational, less concrete, and refer to well-known values. However, other concepts at later stages, being more concrete and activating new values and practices, follow up and fill the space provided while expanding the meaning of the initial reform ideas. The study is an analysis of how the communication of certain concepts and ideas can drive the presentation of educational reform and further discusses possible strategies linked to the observed use of varied concepts and policy ideas.

This work is important, as it shows how policy messages are framed differently at disparate stages of education reform. It contributes to the field of education policy discourse by supplementing studies on the importance of language and concepts in policy development and extending and nuancing our understanding of how certain concepts are used in the early stages of reform introduction while other concepts emerge at later stages of reform implementation and operation. The usage of concepts and ideas in policy is a central issue in understanding the governance processes in education, a question that has barely been analyzed in depth empirically.

Norway’s policy reform of 2006 was introduced under the title “Culture for learning,”Footnote2 with the pronounced goal of improving the culture for learning in schools. “Culture” is a likeable word that suggests a natural, spontaneous, and human side to an organization. The word makes intuitive sense: People use it with ease, despite there being no consensus on the definition (Hoy, Citation1990, pp. 149–150). The reform particularly emphasized the importance of developing a culture for learning in schools in parallel with the expansion of a learning-outcome orientation in national curricula and regulations for assessment (Aasen et al., Citation2012; Mausethagen, Citation2013; Møller & Skedsmo, Citation2013; Mølstad & Prøitz, Citation2018; Nordkvelle & Nyhus, Citation2017; Prøitz, Citation2014). This article traces these concepts and their framing over the reform-intensive period 2003–2017 to gain knowledge about the usage and role of concepts and ideas over time to discuss the role such concepts have in educational governance. More specifically, the research question of this article is: How are education reforms conceptually introduced and framed by the concepts “culture for learning” and “learning outcomes” in policy? Moreover, what usage and role do such concepts have in educational governance over time, and how do they affect one another?

This paper is structured into six sections. In the first section, we introduce and clarify the topic, purpose, and research question of the study. In the second section, we present a review of literature relevant to the study, such as studies on culture for learning in education and learning outcomes in education policy. Following this section, we present the theoretical framework grounded in policy framing and discursive institutionalism. In sections four and five, the context of the study, methods, and analysis are described and presented. In the final section, the findings of the study are discussed, followed by concluding remarks.

Culture for Learning in Education

The use of the concept of culture for learning can be considered connected to a worldwide policy trend in education to improve teaching and learning by developing the school as a learning organization, for example, as explicated by the OECD:

Schools should be reconceptualized as “learning organizations” that can react more quickly to changing external environments, embrace innovations in internal organization, and ultimately improve student outcomes. (OECD, Citation2016b)

Countries have introduced reforms to enhance the development of schools as learning organizations by improving the organizational climate and culture (Hoy, Citation1990). Thematically, the culture for learning within the classroom setting has been understood as a key component to improve the context of teaching and learning and has attracted extensive attention in education policy and research (cf. Heo et al., Citation2018; Teräs et al., Citation2014). Norway is an interesting case due to school reforms in which the two concepts – culture for learning and learning outcomes – were prominent. Although the concept culture for learning can be considered an international and nationally trending concept in education reform, there seem to be few studies on how this is played out in policy. In contrast, there are conceptual studies on learning outcomes where, for example, the renewed focus on learning outcomes has been problematized as scientific management (Au, Citation2011), and calls have been made for research on learning outcomes in different educational contexts, such as the Scandinavian (Hargreaves & Moore, Citation2000). Furthermore, studies have shown that there is a dominant understanding of learning outcomes as the product of education (Hopmann, Citation2008; Kennedy et al., Citation2009; Lassnigg, Citation2012; Lawn, Citation2011; Ozga, Citation2009). This contrasts other, alternative understandings of learning outcomes that emphasize more process orientation in education (Eisner, Citation2005; Prøitz, Citation2014; Prøitz & Nordin, Citation2019). Culture is a popular concept in educational policy and research, though the concept often is used without any consensus on the definition (Hoy, Citation1990, pp. 149–150). For a more elaborate understanding for this main concept of this study we have, in the following section, explored the literature on culture in the field of education.

Culture in the School Context

During the 1980s, culture became a central theme of organizational research (Maslowski, Citation2006; Trice & Beyer, Citation1993) and has been influential ever since. There are multiple definitions of “organizational culture”; however, they all seem to be: “an attempt to capture the feel, sense, character, or ideology of the organization” (Hoy, Citation1990, p. 156). Furthermore, culture, climate, and environment are concepts that tend to be intuitively, but not empirically, verifiable (Anderson, Citation1982; Hoy, Citation1990; Tagiuri, Citation1968). This makes these concepts confusing umbrella terms that are hard to pin down and describe concretely (Alvesson, Citation2002; Baker, Citation2014; Harris, Citation2018; Hoy, Citation1990; Swidler, Citation1986). Culture has been explored and theorized about in several disciplinary fields, often debating the relationship and/or differences between climate and culture (Hoy, Citation1990; Tagiuri, Citation1968; Trice & Beyer, Citation1993). Research on culture within the school context is not new: Waller stated as early as Citation1932 that schools have a separate culture, comprising distinctive personal relationships, a set of folkways, moral codes, traditions, ceremonies, and activities (p. 103).

In the literature on organizational culture, a “culture for learning” is often defined as a set of shared beliefs, values, and attitudes favorable to learning, as noted by the OECD (Citation2010). Additionally, a “good culture for learning” is defined by the openness to new ideas, experimentation, and the openness to errors, empowerment, and participation of employees in decision making and dialogue (Gil & Mataveli, Citation2017). This makes an interesting contradiction to the dominant learning outcome orientation explicated in policy, which mainly emphasizes the product, not process (Prøitz & Nordin, Citation2019). Despite this contradiction, a positive school culture has been encouraged by policy actors as a specific means for improving student results (Hoy, Citation1990, p. 150). Following the growing emphasis on culture in organizational research during the 1980s, culture became recognized as an important aspect of school activities (Hoy, Citation1990; Maslowski, Citation2006). Several studies have been conducted to find connections between school culture and student results or school improvement (Carpenter, Citation2015; Caspersen, Citation2011; MacNeil et al., Citation2009), or to explore schools’ adaptability to policy implementation based on school culture (Van Gasse et al., Citation2016). Other studies have examined the culture for learning in classrooms, finding that trust and positive relationships between teachers and students facilitate successful learning (Heo et al., Citation2018). The culture of policy has also received attention through studies of how values and other cultural influences affect educational policy activity (Marshall, Citation1989) and how a growing audit culture has an impact on education in general (Apple, Citation2005).

Correspondingly, in this article, the policy concepts of culture for learning and learning outcomes are analyzed and discussed in relation to the framing process in educational governance, using analytic tools borrowed from discursive institutionalism (Schmidt, Citation2008, Citation2011).

Policy Framing and Discursive Institutionalism

The framing of policy messages is important when studying education policy developments since this can help identify what aspects of a situation it is focused on and what aspects are ignored (Coburn, Citation2006; Cornwall & Brock, Citation2005; Metha, Citation2011). In the framing process, the “system of ideas” presented is central, for example, in the ways concepts can be understood to work together in what Laclau (Citation1997) calls “chains of equivalence,” where the meaning of equivalent words in a chain gives concepts that work together an advantage over concepts that are conflicting. Meanwhile, conflicting concepts do not have other words that help actualize and enrich meaning (Laclau, Citation1997).

By analyzing what kinds of ideas serve what purposes, how ideas of different types interact, and how ideas change over time, analyses can illuminate how ideas matter in policy (Béland & Cox, Citation2011, p. 25). The way a problem is framed has significant implications for the types of policy solutions that will seem appropriate; therefore, much of the political argument is fought at the level of problem definition. Accordingly, a “problem definition” describes the range of potential choices for policy. For example, one can argue that an educational problem definition emphasizes improvements in test scores and school accountability (Metha, Citation2011, p. 33). Problem definitions can be found in the descriptions of goals for the policy, which is relevant for this study, where the vision of the reform is to create a culture for learning.

Accordingly, the theoretical and analytical point of departure for this article is inspired by the work of Schmidt (Citation2008, Citation2011) and the fourth “new institutionalism”: discursive institutionalism (DI). In DI, ideas are assumed to be a primary source of political behavior and the foundation that shapes how we understand political problems and define our goals and strategies. Additionally, ideas are perceived as the currency used to communicate about politics (Béland & Cox, Citation2011). Discourse is understood as a more versatile and overarching concept, while ideas lie in the background. When the term “discourse” is used, it simultaneously indicates ideas represented by discourse.

In DI, there are three main levels of ideas, based on their level of generality, starting with the least general level of ideas:

“Policy ideas” often take form as policy solutions, which are proposed by policy makers, often situated at a surface level, and are rapidly changing depending on the underlying policy problem, the legacies the new problem challenges, and the capacity of involved actors to change their policy legacies.

“Programmatic ideas” embrace programs that underpin policy ideas. They are crisis-driven and revolutionary, often in periods of uncertainty when “old ways” have failed. They can also be characterized as paradigm shifts, building on Kuhn’s work (cf. Godfrey-Smith, Citation2003). In contrast, there can also be slow shifts (steps/adjustments) in programmatic ideas over time. Usually, several ideas are fighting for dominance (Schmidt, Citation2011).

The “steadiest” level and longer-lasting ideas are called “philosophical ideas,” which are background ideas as underlying assumptions rarely contested, as they refer to shared values and principles of knowledge in the public in general, also called “public philosophies.” Even though public philosophies are usually slow to change, substantial change does and can occur (Schmidt, Citation2011).

The three levels of ideas comprise two types of ideas: cognitive and normative. “Cognitive ideas” clarify “what is and what to do,” while normative ideas point out “what is good or bad about what is,” considering “what one ought to do.” Cognitive ideas provide guidelines for political action and speak to how policies offer solutions to problems. They legitimize policies by appealing to logic and necessity. Normative ideas attach values to political action and serve to legitimize the policies in a program through reference to their appropriateness, which is often closely linked to ideas on the level of philosophical ideas (Schmidt, Citation2008, Citation2011). Normative ideas are often open to interpretation regarding what exactly should be done about a problem. A central question is why some ideas become policies, programs, and philosophies that govern political reality while others do not (Schmidt, Citation2008, p. 307). One factor that influences this issue is the presence of complementary normative ideas capable of satisfying policy makers and citizens alike (Schmidt, Citation2008, p. 308).

Tracing such discursive processes of ideas, concepts and discourses in policy provide a relevant tool for this study to examine the usage and role of these ideas and concepts. The successful discursive framing of concepts and ideas can include relevance to the issue at hand, adequacy, applicability, appropriateness, resonance, and whether the meanings of the words in the discourse are equivalent or conflicting. The credibility of a discourse is likely to benefit from consistency and coherence (Schmidt, Citation2008, p. 311). The basis of our analysis is that the construction of policy involves discourses based on key concepts. That is, we ask how they are part of the framing process of policy problems and solutions and their effect on educational governance. Using DI-inspired analytical tools, we can discuss the levels and types of ideas, providing an understanding of the dynamics of change and continuity (Schmidt, Citation2011), which can expand our understanding of policy implementation and educational governance processes.

Context of the Study

The presented study draws on data from the Norwegian setting. Norwegian education policy has traditionally been characterized by strong social-democratic values often recognized in Scandinavian countries (Telhaug et al., Citation2006). In Norway, this trait was primarily developed after World War II, because education was a central part of the nation’s rebuilding. The rebuilding project was highly influenced by ideological ideas of a social-democratic welfare state characterized by social equality and inclusion (Aasen, Citation2003; Prøitz, Citation2014; Telhaug et al., Citation2004). This led the education system to be publicly viewed and recognized as a tool for individual and collective liberation, social inclusion, social justice, and equality (Aasen et al., Citation2014, p. 722). The public has traditionally viewed public schools as a vital, fundamental element of the welfare state, and an egalitarian and comprehensive school system is highly regarded. However, more recent Scandinavian reforms have been influenced by what is characterized as a market-liberal knowledge regime changing the school system from state intervention to create equality, to a stronger market-liberal mindset that supports an individual, merit-oriented educational system (Aasen et al., Citation2014). This development is especially prominent in Norway through the introduction and development of the Knowledge Promotion ReformFootnote3 (Aasen et al., Citation2014; Telhaug, Citation2005) studied in this article. With the 2006 reform, an outcome-oriented education policy was introduced in Norway that included elements of a national outcome-oriented curriculum, national tests, a national quality-assessment system, new regulations for assessment, and a stronger emphasis on governing by goals and local accountability (Aasen et al., Citation2012). The new national curriculum (LK06) represented a break from former curriculum traditions by defining thematic areas and learning outcomes rather than specifying content and working methods (Mølstad & Prøitz, Citation2018; Prøitz & Nordin, Citation2019). The reform also introduced a strong assessment scheme unfamiliar to Norwegian education that breached a long tradition of skepticism towards assessment in Norway (Lysne, Citation2006). The developments in Norway and Scandinavia are regarded as part of more overall developments in international education policy. Influenced by the EU and OECD, education has changed more toward developing human capital, subsequently becoming increasingly viewed as a contribution to the nation’s economic competitiveness in a globalized economy (Aasen et al., Citation2014; Telhaug, Citation2005). This was the subject of early criticism of the educational reform advocating that equality and solidarity would be replaced by competition (competition inside the school, between schools, and between countries) (Telhaug, Citation2005). Consequently, the example of Norway within a Scandinavian setting illuminates the issue of how older and newer values in education policy are at play in framing education reform initiatives.

Method

Guided by the research question, a corpus of contemporary (2003–2017) educational policy documents was analyzed (Bowen, Citation2009). The period selected for the study can be characterized as reform-intensive, containing the introduction and implementation of the comprehensive Knowledge Promotion Reform and a longer period of reform adjustments (Aasen et al., Citation2012; Prøitz et al., Citation2019). The point of departure is Report to Parliament No. 30 (2003–2004) (henceforth, Report 30), introducing the educational reform of 2006. Report 30 was the starting point in a chain of public documents. It introduced the reform and emphasized culture for learning in schools and the prominence of learning outcomes. This report is titled “Culture for Learning,”Footnote4 indicating a strong emphasis on culture and thus being regarded as an important discursive event and the context in which current educational discourses and activities produced by discourse arise. The analysis includes the following six reports concerning primary and lower-secondary schools regarding educational reform: (1) Report to Parliament No. 16 (2006–2007): Early Intervention for Lifelong Learning,Footnote5 (2) Report to Parliament No. 31 (2007–2008): Quality in School, (3) Report to Parliament No. 22 (2010–2011): Motivation–Mastery–Opportunities; in lower secondary school: (4) Report to Parliament No. 20 (2012–2013): On the Right Path. Quality and Diversity in the Comprehensive School, (5) Report to Parliament No. 28 (2015–2016): School Subject Specialization and Renewal, and (6) Report to Parliament No. 21 (2016–2017): A Will to Learn – Early Intervention and Quality in School (henceforth, reports 16, 31, 22, 20, 28, and 21).

Government reports to Parliament are compiled by government officials in the Ministry of Education and Research. These reports provide a basis for future policy change and legislation. Given their position as recommendation documents and promoting overall and integrated future policy in a field, these texts serve as reference points for government discourse and are viewed as important sources for analyzing dominant trends and shifts in discursive patterns (Aasen et al., Citation2014; Mausethagen, Citation2013; Mausethagen & Granlund, Citation2012, p. 820).

The analysis can best be described as a three-phase content document analysis, which allows examinations of large data sets in a systematic manner (Prøitz, Citation2014; Weber, Citation1990). Phase one was a thorough reading of Report 30 to get an in-depth understanding of the introduction of the reform and identify key ideas and concepts. Phase two was a word count of the key concepts and related concepts in the selected policy documents. Word count is a technique to find patterns in larger sets of documents produced over time and can indicate the significance of certain terms and to what extent the text relates to various concepts therein (Bergström & Boréus, Citation2012; Grue, Citation2011; Prøitz, Citation2014; Prøitz & Nordin, Citation2019). The count of entries was conducted using the query tool in NVivo softwareFootnote6 to obtain an overview of the usage of concepts of culture for learning, learning outcomes, and related concepts throughout the period. To limit the methodological threat of synonyms being used for aesthetic reasons, leading to an underestimation of the importance or frequency of the key concept, it is important to include synonyms in the word count (Prøitz, Citation2014, p. 282). Consequently, word counts were done for related concepts such as learning environment, climate, and learning results.Footnote7 The word count was a search for phrases, not single words. Thus, it counted solely occurrences of the whole phrase: “culture for learning,” excluding references to, for example, the single word “culture.” Since culture for learning also is the title of Report 30, all counts referring to this document (and other namesFootnote8) were excluded from the word count. Headings and titles were also excluded to avoid overestimating the importance of the concept. Finally, sections of texts where key words were present were identified using the text search query in NVivo. The sections were examined methodically with a discourse-inspired approach to document analysis (Mausethagen & Granlund, Citation2012) to identify which other concepts occurred in the same sections to detect potential chains of equivalence. The goal of the last phase was to describe how key ideas and concepts were represented and recorded in reports and how they take part of the framing process of the reform. “Representations” refer to how language is used in a text to give meaning to social practices, events, groups or objects, and conditions (Fairclough, Citation2015). The use of concepts and ideas is viewed as a central political tool that is used strategically in educational governance regarding policy implementation and in general.

The method employed enabled a combined approach that, first, provided an overview of the usage of key concepts and, second, opened for a closer scrutiny of texts extracts wherein key concepts occurred. With this approach, we could identify the frequencies of occurrences of key concepts in policy documents at different times in the reform and in what textual settings they were used. The overall patterns we identified across the data show the development of conceptual usage that places the concept of culture for learning as a normative (foundational) background reform idea. The key concepts of learning outcomes and the related concept of learning environment are identified as cognitive foregrounding reform ideas when examining the developing usage of concepts throughout the studied period. Furthermore, the categories cannot be considered completely mutually exclusive, as the concepts sometimes could take form as partly both normative and cognitive and occasionally partly overlap in relation to the two analytical categories, especially when observed over time. In addition, the study indicates that the discursive use of concepts over time in the documents may have functioned as strategic political arms to shape the public understanding of change (Schmidt, Citation2011) in the implementation process of new policy. Consequently, we have chosen to organize the presentation of the findings according to analytical lenses of normative background reform ideas and cognitive foregrounding reform ideas.

The Normative Background Reform Idea: Culture for Learning

This section starts with a description of how the concept of culture for learning is presented in Report 30 and how the use of the concepts develops through the documents. The opening page of Report 30 statesFootnote9:

The school must also prepare students to be able to look beyond Norway’s borders and be part of a larger, international society. … The vision [of the Knowledge Promotion Reform] is to create a better culture for learning. To achieve this, the ability and desire to learn must increase. The school itself must become a learning organization. Only in this way can it offer attractive workplaces and stimulate pupils’ curiosity and motivation to learn. The school cannot teach us everything, but it can teach us to learn.

Tracing Culture for Learning Into the Related Concept of Learning Environment

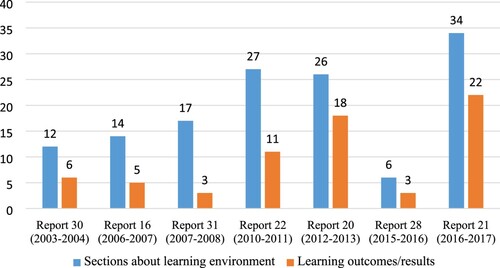

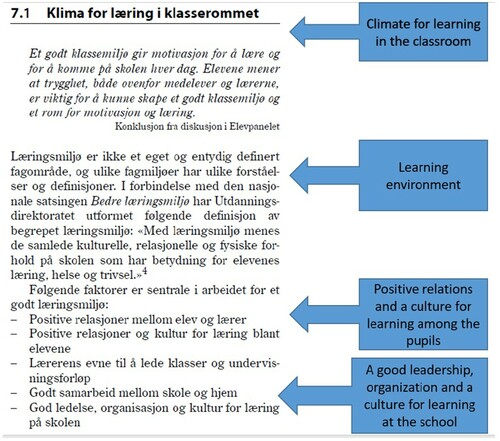

Report 30 was followed by two reports with important adjustments to the reform (reports 16 and 31). Neither emphasized culture for learning. Report 31 mentions culture for learning only once: “The evaluation … shows that many school owners, school leaders, and teachers are concerned with strengthening the collective culture for learning in the school.” However, culture for learning resurfaces in reports 22, 20, and 21, where the focus has shifted. The concept of learning environment seems more in focus. The culture for learning is now limited to the means of creating a good learning environment. By scrutinizing the context of entries about learning environments in these reports, we found that many factors reflect Report 30 concerning what can promote schools’ culture for learning, exemplified by a paragraph in Report 22 (p.68) (see ).Footnote10 There, the terms “climate for learning,” “learning environment,” and “culture for learning” are used interchangeably. The illustration also displays how learning environment is highly connected to the issue of learning. We also observe here how the term “culture for learning” is absorbed into the definition of a good learning environment. Under the heading “Climate for Learning in the Classroom,” learning environment is defined, and a list of factors described as central to creating a good learning environment is presented. Two factors are: positive relationships and a culture for learning among the pupils, and good leadership, organization, and a culture for learning at the school.

Figure 1. Use of the terms “climate for learning,” “learning environment,” and “culture of learning” in Report 22.

The word count supports our impression that the concept of culture for learning abruptly ceases in reports following Report 30. In contrast, the concept of (the) learning environment has a higher word count throughout the period and is accordingly used in a more stable way. In our interpretation, it appears that culture for learning has been absorbed into the definition of a good learning environment.

Cognitive Foregrounding Reform Ideas: Learning Environment and Learning Outcomes

The absorption of culture for learning into learning environment warranted closer analysis. Consequently, all paragraphs and arguments in the seven reports mentioning learning environment were scrutinized. The results demonstrate that the concepts of learning environment and learning outcomes/learning results often, and to an increasing extent, are positioned together (see ). For example, in the 34 sections identified as referring to learning environment in Report 21, learning outcomes or learning results co-occurred 22 times (64%). One example is: “It is set in motion measures to improve pupils’ learning environment with special emphasis on well-being and learning outcomes” (p.39). Another is: “Surveys point to the fact that students get better learning outcomes when they have a learning environment with little bullying, good academic support, a good relationship with the teachers and a high degree of well-being” (p.46). In Report 20, we also see examples where the concepts learning environment and learning results not only co-occur but also are substantially connected: “Studies indicate that how students experience the learning environment in school has a great impact on their motivation, efforts and achievements. In a survey of schools with improvement under the Reform, the researchers find that the most important common denominator in the schools that have had the strongest positive development of grades after the introduction of the reform is that the students experience the learning environment as particularly good” (p.76). Another example is “The work for a better learning environment must have a double goal: A good learning environment for all pupils is both a goal and a means of achieving better learning outcomes” (p.56). A valid interpretation of this is that there is an assumed alignment between the learning environment and learning outcomes/learning.

Normative Background and Cognitive Foregrounding Ideas: Bridging old and new Philosophies

Based on the observations, one can say that the normative background idea of culture for learning faded from the documents, absorbed by more cognitive foregrounding and the stronger concept of learning environment, which becomes closely linked to learning outcomes. This can be understood in how the reform of 2006 had its roots in several events pointing towards stronger results and an outcome orientation in education, such as market-liberal influences containing discourses of globalization and competitiveness and the below-average results of Norwegian students on PISA tests (Karseth et al., Citation2013). The PISA results also supported then-contemporary research revealing that no other country had larger issues with discipline and turmoil in classrooms (Haug & Solbrekke, Citation2003; Telhaug, Citation2005). The reform represented a major shift in Norwegian education policy, from content and process orientation towards competences, moving away from equality and community towards liberty, competition, and individualism (Aasen et al., Citation2014; Telhaug, Citation2005). The policy arguments for change can be understood as starting from a normative idea presenting “what is good or bad about what is,” considering “what one ought to do” (Schmidt, Citation2008, Citation2011). Arguably, the reform idea was presented on the philosophical level (Schmidt, Citation2008, Citation2011) and linked to an emergent shared understanding in policy and among the public for a need to change due to the perception of crisis concerning average PISA results. The problem was PISA results, interpreted as Norwegian students not being prepared to be part of (or compete in) a larger, international society. The solution was educational reform. Public philosophies underwrite collectively shared perceptions and opinions about what measures should be considered legitimate (Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2018, p. 168). Presumably, there was a successful social construction of the need for reform (Cox, Citation2001), where the publication of PISA results triggered public philosophies concerning education. The public became increasingly concerned with Norwegian pupils’ competitiveness in a globalized market. Accordingly, the focus shifted somewhat from traditional philosophies related to collective liberation, social inclusion, social justice, and equality, which are closely linked to the concept of culture. In this context, the normative idea of culture for learning may appeal more to the “old public philosophies” connected to a strong social democratic policy, while the cognitive idea about learning-outcome orientation and learning environment combined appeal more to the new “market-liberal public philosophies.” This observation supports earlier research on how varied knowledge regimes in education policy have been seen to shift to the foreground and background at different times (Aasen et al., Citation2014). In the initial years of the reform, culture for learning seemed to have formed a bridge between older and newer philosophies, making an overlap of parallel policy messages possible in a period of transition. This happened before the tensions and somewhat contradicting content of the reforms’ two key phrases “culture for learning” and “learning outcomes” may have led to an alteration of the normative key concept of culture for learning to the more cognitive and compatible “learning environment.” We have seen the latter work in a chain of equivalence with learning outcomes, which also is in line with those public philosophies concerned with Norwegian students’ competitiveness in an increasingly globalized market. This interpretation of policy discourse as characterized by parallel and contradicting ideas forming the ideational fundament for reform somewhat challenges the notion of public philosophies as established underlying assumptions rarely contested as shared public ideas. The studied example suggests ideas drawing on contradicting knowledge regimes simultaneously leading towards substantial change.

Culture for Learning and Learning Environment

A policy trend spotted in the analysis was the shift from a strong emphasis on culture for learning in Report 30 to an increasing focus on learning environment, especially prominent after 2009, when the government initiated the project “A Better Learning Environment.” In parallel, the concept of culture for learning was absorbed into the definition of “learning environment.” A focus on a good learning environment is in line with the education act/legislationFootnote11 and the national core curriculum, which states the value-related, cultural, and knowledge base for primary and secondary education. The core curriculum has continued since 1993,Footnote12 indicating the content is in line with public Norwegian philosophies. While the concept of culture for learning is not noticeable in the core curriculum or in national legislation, the policy focus on learning environment is legitimated by both legislation and longstanding values relating to education explicitly stated in the core curriculum. Concerning DI, this means learning environment is supported by public philosophies. Besides legitimatization through national legislation and the national core curriculum, learning environment is also externally (internationally) legitimated. For example, it is a central theme for the OECD (Citation2012, Citation2016a):

Learning environments provide the context in which learning takes place. A learning environment is an organic, holistic concept that embraces the learning taking place as well as the setting: an eco-system that includes the activity and outcomes of the learning.

Culture for learning – Just a Buzzword?

There seemed to be an agreement among policy actors and the public about the need for a change in education. However, more specific ideas about how the school system should be changed so Norwegian students could achieve and compete better cannot be considered philosophical, since they were rather new concepts in education and could not then be considered “broad concepts tied to values and moral principles” (Schmidt, Citation2011, p. 111). In this article, the focus is mainly on the two central reform ideas, culture for learning and learning-outcome orientation, which can be seen as policy solutions. The policy idea of culture for learning was strongly communicated to the public as a policy solution not only through Report 30 but also later to achieve a good learning environment and outcomes. However, to persuade the public of the proposal’s benefits, the ideas must be justified (Metha, Citation2011). Why did the idea of culture for learning seem to fade, while learning outcomes succeeded? The legitimacy of these two ideas is in Report 30, also anchored in international surveys and the unsatisfactory Norwegian results. Culture for learning as a normative idea can be interpreted as a policy solution presented to resolve the school system after the “PISA shock,” pinpointing challenges related to learning outcomes and learning environment. However, one can argue that these policy solutions are part of the more general (and unchanging) “programmatic ideas” level, which embraces programs that underpin policy ideas. While the idea of learning outcomes was already internationally established in research and policy, it also had a stronger policy framing globally and a growing foundation in Scandinavia (Prøitz, Citation2014; Prøitz & Nordin, Citation2019). A focus on learning outcomes is also in line with the global neoliberal policy paradigm (Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2018), in which measurement and monitoring are favored methods in governing schools and ensuring students and a nation’s global competitiveness. Learning outcomes as presented in the dominant policy discourse are more standardized and easier to grasp, define, and measure, while culture for learning as a concept is harder to clearly frame. The co-occurrences of learning outcomes and learning environment in policy may lead to an enrichment of the concepts that actualize the conceptual meanings in a chain of equivalence (Laclau, Citation1997). Conversely, a culture for learning is quite vaguely described in the policy framing of Report 30. The framing strongly resembles activities often associated with the monitoring of results and outcomes:

… a desire for continuous development that comes from within the school itself. Cooperation between teachers, networking and exchange of experience between schools, collaboration between home and school, and with local community and businesses and teacher-training institutions are also important prerequisites for school development. … When school owners, school leaders and teachers have knowledge of what should be changed and what should be continued, and this knowledge is used purposefully to strengthen the quality of school and vocational training, the foundation for a culture for learning is laid.

Concluding Remarks

This paper aimed to answer the questions of how core elements of education reforms are conceptually introduced and framed in policy and what the implications of conceptual elements such as culture for learning have for educational governance. Tools from DI highlight how global ideas become integrated into local policy and how some ideas and policy solutions are used to legitimize education reform and the policy emphasis on learning outcomes. However, the reform idea of culture for learning does not seem to be grounded in the same way. Culture for learning, it may be argued, functions as a normative bridge between old and new philosophical ideas in the introduction of the reform. The concept may accordingly been used to gain public acceptance for the new reform. Thereafter, we can see that it abruptly diminishes and collapses into the more concrete, cognitive, and stable concepts of learning environment and learning outcomes through chains of equivalence. This study of concepts, ideas, and discourses in education policy enables an enlarged, although limited, gaze into certain aspects and events of education governance meant to mobilize and prepare public opinion for change. The study has shown how culture for learning, pointing towards more normative process-oriented approaches of schooling, became a buzzword rather than gaining solid reform ground in policy documents. The study exemplifies and thereby highlights how certain concepts that may function well in overall policy communication can be difficult to define and to operationalize for teachers and school leaders in education practice settings. Yet, a buzzword is short, catchy, and easy to remember. Hence, it might still have performed as an effective communicator and mobilizer for education change, and perhaps more so than announcing a focus on learning outcomes. A learning outcome oriantaion might have conflicted with traditional public philosophies in the early phase of the reform.

Potential implications of buzzwords’ impact on policy can be at the practitioner’s level for the principals and teachers at the schools meant to carry out the policies. It is challenging to translate legislative intent into guidelines, goals, and practice at schools when new policy is built on buzzwords. This may also be one reason the policy emphasis on culture for learning abruptly faded and later was integrated into the more comprehensive concept of learning environment.

This paper also indicates that how a reform or new policy is conceptualized and framed is important for its survivability. For a new policy to survive, it seems to be beneficial if it is in a chain of equivalence with other concepts.

Another implication of this study is to call for more research into the use of ideas and concepts in educational governance. Why do certain concepts become short-lived buzzwords, and what is their function in policy development? This might enlighten our understanding of the usage of varied policy messages and the importance of their conceptual framing in periods of transition and education reform. Furthermore, this study of policy documents can only say something about what is emphasized and highlighted in policy. It says nothing about how things turned out in schools. Further research into consequences of initial policy ideas such as culture for learning in Norway’s schools and internationally could shed more light on the potential uptake of overall and more short-lived policy reform ideas.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Knowledge Promotion Reform.

2 In Norway, there is a distinction between the terms “culture for learning” (kultur for læring) and “culture of learning” (læringskultur). In this paper, “culture for learning” partly refers to the title of the policy document announcing the reform “Culture for learning” and partly the usage of this concept pointing towards educational reform for the development of a culture for learning. As such, “culture for learning” in this paper, for example, is separate from a study of an existing culture of learning.

3 Educational reform introduced in 2003, implemented in 2006.

4 Kultur for læring.

5 The title of document 2 is an official English translation; the other titles were translated by the authors.

6 See https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/what-is-nvivo for more information on NVivo.

7 References to the environment and climate were excluded. Only references to the social climate, etc., were included.

8 For example, references to the government-initiated project ‘A Better Learning Environment’ (2009) (‘Bedrelæringsmiljø’) were excluded from the word count.

9 All citations included in this article are translated by the authors.

10 English translation of : Climate for learning in the classroom

The learning environment is not a separate and unambiguously defined subject area, and various academic environments have different understandings and definitions. In connection with the national initiative Better learning environment, the Directorate of Education has formulated the following definition of the term learning environment: “By learning environment it is meant the total cultural, relational and physical conditions in the school that are important for the students’ learning, health and well-being.”

The following factors are central to work for a good learning environment:

Positive relationships between student and teacher; Positive relationships and a culture for learning among students; The teacher’s ability to lead classes and the teaching proceedings; Good cooperation between school and home; Good leadership, organization, and culture for learning at the school.

11 Opplæringsloven §9A.

12 The core curriculum is being changed in the curriculum reform of 2020, which has created much engagement in academic communities (6,700 inputs on the proposals). However, the focus on a good learning environment is also continued in this new curriculum reform, retrieved 26.06.19 https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/skolens-nye-grunnlov-er-fastsett/id2569170/

References

- Aasen, P. (2003). What happened to social–democratic progressivism in Scandinavia? Restructuring education in Sweden and Norway in the 1990s. In M. W. Apple (Ed.), The state and politics of knowledge (pp. 109–147). Routledge Falmer.

- Aasen, P., Møller, J., Rye, E., Ottesen, E., Prøitz, T. S., & Hertzberg, F. (2012). Kunnskapsløftet som styringsreform – et løft eller et løfte? Forvaltningsnivåenes og institusjonenes rolle i implementeringen av reformen [The Knowledge Promotion Reform. The Role of Levels of Government and Institutions in Reform Implementation] (Report no.20). NIFU.

- Aasen, P., Prøitz, T. S., & Sandberg, N. (2014). Knowledge regimes and contradictions in education reforms. Educational Policy, 28(5), 718–738. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904813475710

- Alvesson, M. (2002). Understanding organizational culture. Sage.

- Anderson, C. S. (1982). The search for school climate: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 52(3), 368–420. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1170423

- Apple, M. W. (2005). Education, markets, and an audit culture. Critical Quarterly, 47(1–2), 11–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0011-1562.2005.00611.x

- Arnott, M., & Ozga, J. (2010). Education and nationalism: The discourse of education policy in Scotland. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 31(3), 335–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01596301003786951

- Au, W. (2011). Teaching under the New Taylorism: High-stakes testing and the standardization of the 21st century curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(1), 25–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2010.521261

- Baker, D. (2014). The schooled society. The educational transformation of global culture. Stanford University Press.

- Bergström, G., & Boréus, K. (2012). Innehållsanalys. In G. Bergström, & K. Boréus (Eds.), Textens mening och makt: metodbok i samhällsvetenskapligtext–ochdiskursanalys (3rd ed.). Studentlitteratur.

- Béland, D., & Cox, R. H. (2011). Ideas and politics in social science research. Oxford University Press.

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Carpenter, D. (2015). School culture and leadership of professional learning communities. International Journal of Educational Management, 29(5), 682–694. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-04-2014-0046

- Caspersen, J. (2011). Skolekultur og elevresultater – Hvilke muligheter gir TALIS – undersøkelsen? (34). https://www.udir.no/globalassets/upload/5/skolekultur_elevresultater.pdf

- Coburn, C. E. (2006). Framing the problem of reading instruction: Using frame analysis to uncover the microprocesses of policy implementation. American Educational Research Journal, 43(3), 343–379. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312043003343

- Cornwall, A., & Brock, K. (2005). What do buzzwords do for development policy? A critical look at ‘participation’, ‘empowerment’ and ‘poverty reduction’. Third World Quarterly, 26(7), 1043–1060. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590500235603

- Cox, R. H. (2001). The social construction of an imperative: Why welfare reform happened in Denmark and the Netherlands but not in Germany. World Politics, 53(3), 463–498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2001.0008

- Eisner, E. W. (2005). Reimagining schools: The selected works of Elliot W. Eisner. Routledge.

- Fairclough, N. (2015). Language and power (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Gil, A. J., & Mataveli, M. (2017). The relevance of information transfer in learning culture. Management Decision, 55(8), 1698–1716. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2016-0800

- Godfrey-Smith, P. (2003). Theory and reality: An introduction to the philosophy of science. University of Chicago Press.

- Godin, B. (2006). The knowledge-based economy: Conceptual framework or buzzword? The Journal of Technology Transfer, 31(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-005-5010-x

- Grue, J. (2011). Maktbegrepet i kritisk diskursanalyse: Mellom medisinske og sosiale forståelser av funksjonshemming [The concept of power in critical discourse analysis: Between medical and social understandings of disability]. In T. R. Hitching, A. B. Nilsen, & A. Veum (Eds.), Diskursanalyse i praksis (pp. 116–134). Høyskoleforlaget.

- Hargreaves, A., & Moore, S. (2000). Educational outcomes, modern and postmodern interpretations: Response to Smyth and Dow. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 21(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690095144

- Harris, J. (2018). Speaking the culture: Understanding the microlevel production of school culture through leaders’ talk. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 39(3), 323–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2016.1256271

- Haug, P., & Solbrekke, T. D. (2003). Evalueringaav reform 97 [Evaluation of the education reform of 1997]. Norskpedagogisktidsskrift, 88(04|4), 245–247.

- Heo, H., Leppisaari, I., & Lee, O. (2018). Exploring learning culture in Finnish and South Korean classrooms. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(4), 459–472. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2017.1297924

- Hopmann, S. T. (2008). No child, no school, no state left behind: Schooling in the age of accountability. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 40(4), 417–456. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270801989818

- Hoy, W. K. (1990). Organizational climate and culture: A conceptual analysis of the school workplace. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 1(2), 149–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532768xjepc0102_4

- Karseth, B., Møller, J., & Aasen, P. (2013). Reformtakter: Om fornyelse og stabilitet i grunnopplæringen [Reform measures: Renewal and stability in basic education]. Universitetsforlaget.

- Kennedy, D., Hyland, A., & Ryan, N. (2009). Learning outcomes and competences. Introducing Bologna objectives and tools. https://curriculum.gov.mt/en/Teachers%20Learning%20Outcomes/Documents/Training%20Material/Paper-LoS-and-Competences-Bologna.pdf

- Laclau, E. (1997). The death and resurrection of the theory of ideology. Modern Language Notes, 112(3), 297–321. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3251278

- Lassnigg, L. (2012). ‘Lost in translation’: Learning outcomes and the governance of education. Journal of Education and Work, 25(3), 299–330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2012.687573

- Lawn, M. (2011). Governing through data in English education. Education Inquiry, 2(2), 277–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v2i2.21980

- Lysne, A. (2006). Assessment theory and practice of students’ outcomes in the Nordic countries. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 327–359. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830600743365

- MacNeil, A. J., Prater, D. L., & Busch, S. (2009). The effects of school culture and climate on student achievement. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 12(1), 73–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120701576241

- Marshall, C. (1989). Culture and education policy in the American states. The Falmer Press, Taylor and Francis, Inc.

- Maslowski, R. (2006). A review of inventories for diagnosing school culture. Journal of Educational Administration, 44(1), 6–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230610642638

- Mausethagen, S. (2013). Reshaping teacher professionalism: An analysis of how teachers construct and negotiate professionalism under increasing accountability. Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences.

- Mausethagen, S., & Granlund, L. (2012). Contested discourses of teacher professionalism: Current tensions between education policy and teachers’ union. Journal of Education Policy, 27(6), 815–833. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.672656

- Metha, J. (2011). The varied roles of ideas in politics. In D. Béland, & R. H. Cox (Eds.), Ideas and politics in social science research (pp. 23–46). Oxford University Press.

- Møller, J., & Skedsmo, G. (2013). Modernisingeducation: New public management reform in the Norwegian education system. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 45(4), 336–353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2013.822353

- Mølstad, C. E., & Prøitz, T. S. (2018). Teacher–chameleons: The glue in the alignment of teacher practices and learning in policy. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(3), 403–419. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1504120

- Nordkvelle, Y., & Nyhus, L. (2017). Management by objectives as an administrative strategy in Norwegian schools: Interpretations and judgements in contrived liberation. In N. Veggeland (Ed.), Administrative strategies of our time (pp. 220–260). Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

- OECD. (2000a). Knowledge management in the learning society. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264181045-en

- OECD. (2000b). Where are the resources for lifelong learning? OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264061439-en

- OECD. (2003). Learners for life: Student approaches to learning. Results from PISA 2000. OECD Publishing. . https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264103917-en

- OECD. (2010). Defining learning organisations and learning cultures. In Innovative workplaces: Making better use of skills within organisations (pp. 19–29). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264095687-4-en.

- OECD. (2012). Review education policies. https://gpseducation.oecd.org/revieweducationpolicies/#!node=&filter=all

- OECD. (2016a). PISA 2015 results (Volume II): Policies and practices for successful schools, PISA. OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2016b). What makes a school a learning organisation? A guide for policy makers, school leaders and teachers. https://www.oecd.org/education/school/school-learning-organisation.pdf

- Ozga, J. (2009). Governing education through data in England: From regulation to self-evaluation. Journal of Education Policy, 24(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930902733121

- Prøitz, T. S. (2010). Learning outcomes: What are they? Who defines them? When and where are they defined? Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 22(2), 119–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-010-9097-8

- Prøitz, T. S. (2014). Learning outcomes as a key concept in policy documents throughout policy changes. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(3), 275–296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2014.904418

- Prøitz, T. S., & Nordin, A. (2019). Learning outcomes in Scandinavian education through the lens of Eliot Eisner. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1595717

- Prøitz, T. S., Rye, E., & Aasen, P. (2019). Nasjonal styring og lokal praksis – skoleledere og lærere som endringsagenter [National governance and localpractice – school leaders and teachers as change agents]. In R. Jensen, B. Karseth, & E. Ottesen (Eds.), Styringogledelseigrunnopplæringen [Management and leadership in the primary and secondary education and training] (pp. 21–37). CappelenDamm AS.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2008). Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annual Review of Political Science, 11(1), 303–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135342

- Schmidt, V. A. (2011). Speaking of change: Why discourse is key to the dynamics of policy transformation. Critical Policy Studies, 5(2), 106–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2011.576520

- Scudellari, M. (2017). Big science has a buzzword problem. Nature, 541(7638), 450–453. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/541450a

- Swidler, A. (1986). Culture in action: Symbols and strategies. American Sociological Review, 51(2), 272–286. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2095521

- Tagiuri, R. (1968). The concept of organizational climate. In R. Tagiuri& G, & W. Litwin (Eds.), Organizational climate: Explorations of a concept (pp. 1–32). Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University.

- Telhaug, A. O. (2005). Kunnskapsløftet – ny eller gammel skole? Beskrivelse og analyse av Kristin Clemets reformer i grunnopplæringen [The knowledge promotion reform –new or old school?]. Cappelen akademisk forl.

- Telhaug, A. O., Mediås, O. A., & Aasen, P. (2004). From collectivism to individualism? education as nation building in a Scandinavian perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 48(2), 141–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0031383042000198558

- Telhaug, A. O., Mediås, O. A., & Aasen, P. (2006). The Nordic model in education:Education as part of the political system in the last 50 years. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 60(3), 245–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830600743274

- Teräs, H., Teräs, M., Leppisaari, I., & Herrington, J. (2014). Learning cultures and multiculturalism: Authentic e-learning designs. In T. Issa, P. Isaias, & P. Kommers (Eds.), Multicultural awareness and technology in higher education: Global perspectives (pp. 197–217). IGI Global.

- Trice, H. M., & Beyer, J. M. (1993). The cultures of work organizations. Prentice-Hall.

- Van Gasse, R., Vanhoof, J., & Van Petegem, P. (2016). The impact of school culture on schools’ pupil well-being policy-making capacities. Educational Studies, 42(4), 340–356. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2016.1195718

- Wahlström, N., & Sundberg, D. (2018). Discursiveinstitutionalism: Towards a framework for analysing the relation between policy and curriculum. Journal of Education Policy, 33(1), 163–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1344879

- Waller, W. (1932). The sociology of teaching. John Wiley & Sons.

- Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis (2nd ed.). Sage.