ABSTRACT

This work investigated the processes of teacher informal learning focused on building positive teacher–pupil interaction. The conceptual framework “Teacher professional agency for learning” was merged with the “Teaching through interaction” model to compound the exploratory framework of this study: Teachers learn by interacting. Teachers first reported their professional agency through a survey. Next, five high scoring teachers were selected for interview. Final participants accounted being motivated and confident of improving their relationships with pupils and reported using diverse learning strategies to improve teacher–pupil interactions. The teachers revealed the need to be authentic to build positive relationships with pupils. This study contributes to the area of teacher learning by addressing transferable strategies that support everyday teacher practices and professional development.

1. Introduction

In order to teach increasingly complex contents while providing personalized education (Bransford et al., Citation2005; Powell & Kusuma-Powell, Citation2011), developing positive interactions with pupils is essential (Hamre & Pianta, Citation2001). A positive teacher–pupil relationship can be characterized by respectful communication, sensitivity and responsiveness, focus and interest on teaching–learning content, and a low level of disruptive behaviour (Jennings & Greenberg, Citation2009). From the pupils’ perspective, experiencing a teacher's support makes the pupils feel that they belong in the classroom, increasing their affective learning, e.g., pupil attitude towards the content and the teacher (Frymier & Houser, Citation2000), which reinforces their effective learning, active exploration of the school environment, and engagement in peer interactions (Jennings & Greenberg, Citation2009; Titsworth et al., Citation2013). From the teachers' perspective, a pleasant classroom climate reinforces enjoyment and self-efficacy feelings, increasing enthusiasm and commitment to the profession, which may prevent teacher drop out from work (Dicke et al., Citation2015).

The impacts of a good teacher–pupil relationship emphasize the need of understanding how teachers engage and sustain positive interactions with their pupils (Henning et al., Citation2017). De Bruyckere and Kirschner (Citation2016) have shown that if teachers want to actively strengthen their relationships with pupils, casual contacts and informal moments, such as class breaks or school trips, are greatly appreciated by students and impact on classroom atmosphere. Complementarily, Brekelmans et al. (Citation2005) reported that teacher–pupil relationship, based on influence and proximity, is rather stable over the teachers’ career. Both studies, however, call for future research on extended subjective conceptualized descriptions of how teachers understand interacting with pupils over time. This work aims to address such suggestion.

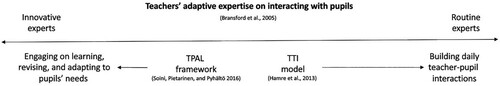

We started from the work of Bransford et al. (Citation2005), who reported that the current high diversity of pupils in one classroom and the regular change of pupil groups increase the dynamism of teachers' work and require a high level of “adaptive expertise”. That is, teachers need to be routine experts in order to deal effectively with daily classroom situations, but also innovative experts capable of revising previous routines in order to adapt to individual pupils and their personal learning processes (Bransford et al., Citation2005). To visualize our understanding of teacher adaptive expertise, the double arrowed line in points to both the routine expertise tip as well as to the innovative tip. Yet, research has not investigated in an integrated manner these two apparently opposite, but in fact complementary aspects of teacher expertise on relating to pupils. Therefore, this study addresses the whole spectrum by investigating how experienced teachers continue to learn (the innovative side) focused on building daily positive interactions with pupils (the routine side).

For that purpose, we examined the research question (RQ): How do experienced teachers perceive their informal learning process of developing positive interactions with pupils? The RQ will be answered by merging two existing theoretical contributions. First, the “Teaching through interaction” model will represent the different dimensions of teacher–pupil classroom interactions. Second, the conceptual framework “Teacher professional agency for learning” will approach teachers’ engagement in professional learning. We combined both to create a comprehensive exploratory framework for understanding teachers’ informal learning focused on improving their relationships with pupils.

1.1 The Teaching Through Interaction Model

The teaching through interaction (TTI) model developed by Hamre et al. (Citation2013) highlights the interactions between teachers and students as a core task of a teacher's work. It consists of a “multilevel latent structure for organizing teacher–student interactions” (Hamre et al., Citation2013, p. 463), designed with three broad domains: Emotional Support, Classroom Organization, and Instructional Support, which are subdivided into 13 dimensions. Hamre et al. (Citation2012) built the dimensions based on daily classroom interactions that have been indicated to promote children's social and academic development.

The Emotional Support domain (Hamre et al., Citation2013) considers the overall emotional tone of classroom interactions: either positive, warm and respectful, or negative, stressful and marked by conflicts. This domain also considers how much a teacher is sensitive to and aware of pupils’ needs, motivations and perspectives, creating student-driven activities. It observes how teachers promote a learning environment in which pupils feel safe to explore autonomously. This domain is compounded by the dimensions: positive climate, negative climate, teacher sensitivity, regard for students’ perspectives and overcontrol.

The Classroom Organization domain (Hamre et al., Citation2013) approaches the ability of teachers to prevent and redirect misbehaviour by presenting clear expectations. The efficacy of teachers in providing routines and learning instructions is also covered. This domain considers the quality and diversity of the daily materials offered to pupils to maximize learning according to each child's particularities. The Classroom Organization domain is compounded by the dimensions: behaviour management, productivity, instructional learning formats and classroom chaos.

Finally, the Instructional Support domain (Hamre et al., Citation2013) considers the quality of teacher's instructions regarding the stimulation of students’ higher-order thinking. Likewise, the degree to which a teacher's feedback promotes formative evaluation to expand understanding, and teacher's speech formulation boosts differential uses of language by pupils, is also considered. This domain is compounded by the dimensions: concept development, quality of feedback, language modelling, and richness of instructional methods.

In this study, we used the TTI model as a theoretical reference to analyse the teacher–pupil routine interactions from the teachers’ perspective. However, it does not address how teachers have learnt to build such interactions with pupils over time. The next section adds to the TTI model a holistic conceptual framework that helps to understand how teachers engage on learning towards building interactions with pupils.

1.2 The Teacher Professional Agency for Learning Framework

Everyday classroom situations demand flexible pedagogical practices from teachers, resulting in rich informal learning environments (Korthagen, Citation2010; Kwakman, Citation2003; Lohman, Citation2006). Informal learning can be defined as changes in (or reinforcement of) professional competences occurring as a result of engaging in learning activities which are not “structured in terms of time, space, goals, and support” (Kyndt et al., Citation2016, p. 1113). Informal learning often occurs in a reactive form, although it does not imply to be a passive or an unintentional process (Hoekstra et al., Citation2007).

Evidence shows that teachers engage in informal learning at work when they have strong professional agency (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015). Although this concept has been under active – and sometimes contradictory – elaboration in the past decade (Edwards, Citation2005; Vähäsantanen et al., Citation2018), in this study teacher professional agency will focus on the teachers’ ability to manage their own processes of learning centred on building positive interactions with pupils. The specific concept of teacher professional agency in the classroom (TPAC) aims to integrate teachers’ learning in the classroom gauged by three interrelated elements: efficacy beliefs about learning, motivation to learn, and active learning strategies (Soini et al., Citation2016).

Teachers with strong TPAC recognize themselves as capable of learning, of evaluating their own teaching in the light of the students’ outcomes, and of acting intentionally towards improving their professional competence (Takahashi, Citation2011). This means that strong efficacy beliefs in learning help teachers to face the challenges that might arise in their learning process (Soini et al., Citation2016) focused on building positive interactions with pupils.

Teachers also need motivation to accomplish self-oriented learning. Factors such as interest in the profession (Reeve & Su, Citation2014) and love of learning (Kyndt et al., Citation2016) support teachers’ motivation towards continuous professional development. Complementarily, teachers who are more motivated for learning enact self-regulative strategies and adapt to students’ needs (Jennings & Greenberg, Citation2009).

Additionally, one needs to actually engage in actions to alter behaviour or strengthen previous practices (Soini et al., Citation2016). Teachers have reported using different strategies to improve professional competences at work, such as reading to keep oneself updated with professional developments; experimenting something new; reflecting to recognize problems and change them; or “just” learning by doing the classroom routines (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006; Hoekstra et al., Citation2007).

Beyond the above individual learning strategies, teachers see “collaboration with their colleagues as an important resource for exercising professional agency through actively developing teaching practices” (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2015, p. 668). However, Soini et al. (Citation2016) discussed that learning from the teacher community and from classroom situations requires classroom boundary crossing (CBC), which means the capacity of a teacher to cross the classroom limits to identify learning opportunities from other school contexts and actors, sharing with them solutions for correlated problems (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015). CBC combines communicative processes which lead to transformative practices to all involved. Therefore, we consider CBC as an collaborative learning strategy aligned with the concept of TPAC (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2015; Pyhältö et al., Citation2015), and both will be referred as “Teacher professional agency for learning” (TPAL) framework.

In addition, research has shown that inherently connected to teacher professional agency for learning and how teachers relate to pupils over time are the construction of teacher identity (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2015) and how professional and personal identities interrelate in teachers’ work (Day et al., Citation2006). According to James-Wilson (Citation2001, p. 29): “This professional identity helps them to position or situate themselves in relation to their students and to make appropriate and effective adjustments in their practice and their beliefs about, and engagement with, students”. Thus the extent to what teachers recognize that building positive interactions with pupils is a core part of their role as a teacher, and how much personal investment they put on it, impacts how much effort they exert to learn about teacher–pupil interactions over time (Lasky, Citation2005). Complementarily, De Bruyckere and Kirschner (Citation2016) reported that pupils want teachers to put their “true self” and to be authentic in order to build bond in their interactions. Considering these studies, it seems that the professional engagement of teachers with their pupils is intermeshed with how much teachers “are being themselves” in their relationships.

To summarize the link between the two main theoretical contributions, this study used the TTI model to analyse daily teacher–pupil interactions at different dimensions, addressing the routine expertise of the spectrum represented in . Additionally, we integrated the TPAL framework, with the TPAC and CBC concepts, to compose the core elements that engage teachers in informal learning towards positive relationships with their pupils. This second contribution addresses, then, the innovative expertise of the spectrum. With both conceptual contributions we were capable to address teachers’ adaptive expertise on interacting with pupils (Bransford et al., Citation2005). Therefore, the aim of merging both frameworks was to conceptually and holistically comprehend teachers’ informal learning focused on building positive interactions with pupils.

2. Methodology

We applied a mixed method approach with multiple-cases analysis (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017) in two phases. (1) Quantitative phase: survey application aimed at exploring the overall TPAL of school teachers. The highest scoring teachers on TPAL with time availability were purposefully sampled for the next phase. (2) Qualitative phase: individual semi-structured interviews for in-depth data analysis.

2.1 Quantitative Phase: Measurements, Participants, and Analysis for Purposeful Sampling

The Teacher's professional agency in the classroom (TPAC) scale operationalizes in 10 items the deliberative action of teachers to improve their practice in classroom in two parts: collaborative environment and transformative practice (CLE, six items, e.g., “I can modify my teaching to adjust to different groups of pupils”) and reflection in the classroom (REF, four items, e.g., “I still want to learn a lot about teaching”). The Classroom boundary crossing scale (CBC, three items, e.g., “I can utilise other teachers' ideas in my own teaching”) measures a teacher's capacity to use ideas from other teachers, as well as to share her/his own practices with others. Both scales are rated on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). They were validated in the Finnish context and were used to indicate how much teachers were prone to engage in informal learning at work (Soini et al., Citation2016).

The invitation to participate in the survey was sent randomly to half of the primary schools in the capital area of the eastern part of Finland. Ten medium-sized schools (100–400 students) agreed on participating in the research. The online survey was then sent by email to all teachers of each school, comprehending the ones who take responsibility of their own class and teach subjects for their pupils, but also to the teachers who occupy functions other than classroom teaching such as the headmasters, special teachers, and educators. The participation was voluntary, and 48 teachers answered the survey (ca. 25% response rate). The participants worked in first to sixth grades, some of them teaching more than one grade. The teachers follow the Finnish national core curriculum (Finnish National Board of Education, Citation2016) as a framework, but all schools have their own curriculum as an action plan. The grade with the highest portion of teachers responding was 5th grade, and 70.8% were female. They had from 5 to 39 years of teaching experience (M = 19.9, SD = 9.02).

The internal consistency of the scales was tested using the software IBM SPSS Statistics 23. The TPAC and the CBC scales together reached Cronbach's α = .83, confirming strong reliability of the results. Overall, the participants scored high for the measured aspects of TPAC and CBC together (M = 5.32). features means, standard deviations, Cronbach's alpha, and intercorrelations between CLE, REF, and CBC. Additionally, in our sample, neither gender (x2 (16, N = 48) = 12.47, p = .71) nor years of experience (x2 (24, N = 48) = 25.41, p=.384) influenced how teachers perceived their TPAC and CBC.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, Cronbach's alpha, and intercorrelations among all subscales (N = 48).

The survey provided a reliable and general view about the TPAL of the teachers, supplying relevant information for the selection of the five high scoring participants with time availability to be part of the second phase of the research.

2.2 Qualitative Phase: Interviewees and Data Analysis

Interviewees were selected for being a group of teachers who perceived to be more tuned to learning from their classroom situations, pupils, and teacher community according to the survey results. Therefore, this sample would be more able to express, in-depth, their values, experiences, and insights of their informal learning and consequential developments focused on building positive interactions with pupils (Gaskell, Citation2000). The interviews were audio recorded and the most relevant parts transcribed verbatim. shows the interviewees’ profile, together with their TPAC/CBC values, and general characteristics of the interviews.

Table 2. Interviewees’ profile by gender, years of experience, teacher activity, grade, interviews’ time, and TPAC and CBC means.

The interviews started by appraising how the teachers understand teacher–pupil interactions to set the focus of the investigation. The subsequent questions were developed based on the TPAL framework and directed to the teachers’ learning focused on their relationships with pupils in their entire career. The teachers were constantly invited to illustrate in details everyday classroom situations which they considered relevant for their learning towards their interactions with pupils. These narratives were strategic for teachers to better recall informal learning processes that were not planned but happed in a (re)active form at their workplace. Additionally, when aspects of the TTI model were explicitly mentioned, they were also explored during the conversation.

The analysis of the text corpus from the interviews was made using theory-driven content analysis (CA) as analytical method. The theory-driven CA (Neuendorf, Citation2016) was based on the TPAL framework and the TTI model. The categories were identified in the text corpus when full sentences and their semantic meanings could be deduced from them. Therefore, when participants referred to the reasons that would drive them to invest in understanding and improving their relationships with pupils, these parts fell within the motivation category. When the teachers reported how confident they were to be capable of changing and adapting their relationships with pupils, these parts were considered as self-efficacy in learning. When teachers described any types of actions, both mental and behavioural, that would lead them to improve their interactions with pupils, these parts were coded as learning strategies.

For analytical purposes, the category active learning strategy was rooted into two sub-groups. Collaborative strategies included the CBC category, i.e., any type of collaboration with other school agents to improve their relationships with pupils. Individual strategies included reading any type of literature; experimenting something new; reflecting about events; and learning by doing classroom routines.

Exceptionally the learning by doing strategies were then, analysed, across the TTI dimensions of emotional support, classroom organization, and instructional support (Hamre et al., Citation2013), because they were suitable to clearly organize how teachers report their learning strategies towards bettering their interactions with pupils in classroom routines. For instance, when a teacher reported to consider pupils’ emotional state in the classroom, this was classified in the category teacher sensitivity within the emotional support dimension. The same was done over the codes across the dimensions of classroom organization and instructional support. Because these learning strategies are not isolated from each other, some codes overlapped, and they were reported in the results to mirror the complexity of the participants’ learning process focused on improving their relationships with pupils.

Complementarily, a data-driven CA (Neuendorf, Citation2016) was accomplished. It was observed from the teachers’ spontaneous voicing the importance of a new code regarding teacher–pupil relationships: the teachers’ authenticity. It appeared in the sense that teachers merge their personal identity within their professional role to build authentic relationships with pupils. This data-driven code was inserted in the teacher identity category because of its intrinsic theoretical relationship (Day et al., Citation2006; Lasky, Citation2005), which was also supported by the data. Therefore, the category and its code were added to the final coding frame.

Intra-coder and inter-coder reliability were calculated based on individualized quotations taken from the text corpus, totalizing 282 analytical units. To reach agreement, most of the codes applied within one quotation should be the same. The first author coded the interviews twice with a time gap of 4 months, yielding an intra-coder Cohen's kappa of k = .68 (95% CI, .62 to .73), p = .01. Additionally, the second author coded a sample of the interviews to yield intercoder reliability, reaching k = .62 (95%CI, .52 to .71). Both coefficients support transferability of the findings according to the literature (Neuendorf, Citation2016).

Although the sample presented useful variations of the investigated dimensions, enriching the empirical findings and theoretical discussions, it also brought up similar points of coverage from their experiences. Therefore, we considered that the data reached a saturation point of data analysis (Seawright & Gerring, Citation2008).

3. Results and Discussion

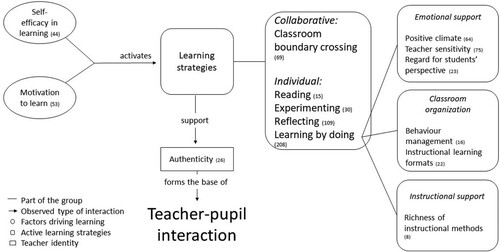

The frequency distribution of the individual codes featured a range of eight to 109 appearances (excluding the codes that had null frequencies). The codes motivation to learn, efficacy beliefs in learning, reflecting, experimenting, CBC, positive climate, teacher sensitivity, and authenticity were equal to or above the global median of appearance (Med = 26, SD = 30.06). However, the codes negative climate, overcontrol, productivity, classroom chaos, concept development, quality of feedback, and language modelling did not appear to support teachers to learn about building positive interactions with pupils – thus not further discussed.

The findings are presented in three groups of codes based on their interconnections according to the role they played in the teachers’ informal learning focused on building positive interactions with pupils. The relationships of the codes were deduced from their regular interactions conform the teachers’ voicing of their own experiences and interpreted according to the literature review (Maxwell, Citation2004). Following this analysis, the exploratory framework Teachers learn by interacting was developed and represented in , which displays the frequencies of the codes and their relatedness. The groups of codes are represented by different shapes. The round cluster consists of the factors that support and initiate teacher informal learning. Teacher informal learning is then accomplished by active strategies to learn, both individual and collaborative ones, represented by the squared cluster. Finally, the rectangular cluster portrays the aspect of teacher identity that ultimately underlies teacher–pupil interactions.

3.1 How do Experienced Teachers Perceive Their Informal Learning Process of Developing Positive Interactions with Pupils?

3.1.1 Factors that Activate Teacher Informal Learning

Both motivation to learn and efficacy beliefs in learning appeared as relevant factors driving teachers to be interested in developing positive relationships with pupils in their everyday work.

In general, the main motivator for the teachers’ learning was to contribute to their pupils’ education and general growth. “Good interaction is very good motivation in teacher's work […] my pupils, they are growing mentally, as persons, they are growing in knowledge, they understand more and more and they achieve academic tasks” (Teacher 4). They recognized that interacting with pupils towards influencing their general development is a core teacher role.

Teachers were also motivated to learn about pupils with the explicit aim of including their interests in the classroom discussions and in the subject content. Therefore, the teachers fostered the interactions by indicating their willingness to know pupils’ life and their areas of interest. Using the vocabulary that pupils use and recognizing their hobbies facilitated the engagement of pupils to the lessons.

I’d like to know more about my pupils, so that I can be on the same level as them […] If the boys are talking about something in the class, I can ask them if this is ice hockey talk or are you talking about dogs or something else. […] So I can use their interests in our discussions. (Teacher 1)

All participants had consistent beliefs that they are learning and want to continue to do so regarding their interactions with pupils. They considered themselves capable of learning thanks to all the previous experiences they have been through with interacting with pupils. “[…] How you see yourself as a teacher and how many different situations you have in your backpack of social problems or interaction problems” (Teacher 2).

One teacher reported how his own efficacy beliefs in learning changed over time, because becoming more experienced helped him face the fact that he might not know everything – against his youthful beliefs. “You're always right when you're young. Older people, they don't know anything. But now, when I'm old, I know, they do know something” (Teacher 5). The last extract also represents how teachers identifying themselves as experienced teachers contribute to their sense of self-efficacy in learning, confirming the relevance of professional identity formation for teachers to employ their agency at work (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2015).

From the participants’ description of motivation and efficacy beliefs in learning, we interpret that the teachers are engaged in their work, want to learn from it, and place their pupils at the heart of their teaching. Ultimately, these factors activate teachers’ learning strategies to continue building positive interactions with their pupils.

3.1.2 Learning Strategies that Support Building Positive Interactions with Pupils

CBC, meaning sharing and aligning ideas with colleagues, children's parents, and other school staff, was a valuable strategy for teachers to learn to interact in different ways with pupils. According to the participants, other colleagues build a collective memory and share a common language that facilitate their joint learning process.

The teachers practice mentoring, joint classes, and cooperation within lessons. “We talk about a lot of different things. It's like cooperative teaching, we're teaching together […] Finnish teachers also reflect with each other, talking about all the possible things” (Teacher 5). Likewise, they help each other when one teacher needs a mediator for difficult situations with pupils, practicing peer coaching and collaborative classroom management to address students’ misbehaviour.

Complementarily, parents were considered valuable resources because of their knowledge regarding their children's particularities. Special relevance of parent cooperation was given in the cases of children from different ethnic backgrounds. This situation is currently relevant in Finland due to the increased number of immigrants that came to the country after the refugee crisis in 2015 (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland, Citation2016).

They [parents] are specialists of their children. […] For example, we had a meeting […] with one daughter from Syria. Her father was there and our meeting was 25 min. maximum, but what he talked was very useful for us and after that, now we know what to do with this child. (Teacher 4)

One participant emphasized, though, that sometimes parents can be invasive if they are present in the everyday work. “I'm afraid they're going to tell me how to do my job and I don't like that” (Teacher 5).

Other school staff were also valuable learning resource for teachers, such as teaching assistants. “My assistant has been working with these same children for four years before me. Quite often, she says, maybe we should do this or that. And it is very good.” (Teacher 4).

Only one teacher talked briefly about reading focused on interacting with pupils. He expressed his need to keep himself updated with technology to feel on the same page as his students. “I’m behind my pupils in many cases and I should study much more, for example about tablet computers” (Teacher 4). We consider that technology in education has the potential to promote powerful intergenerational learning and can boost teacher–pupil interactions (Gamliel & Gabay, Citation2014).

Experimenting was frequently mentioned by the participant as a powerful way of learning, because it is when teachers change the routine and try something new (Kwakman, Citation2003). The participants emphasized experimenting with different teaching methods more in the beginning of their careers, confirming previous literature (Grosemans et al., Citation2015; Kyndt et al., Citation2016). Also, the teachers reported that when they experiment, they consider their pupils as co-designers of such practices.

OK, we have history of Rome, and we're discussing with pupils about how they would like to learn as much as possible about Rome. […] I put them into groups, make them plan, make a mind map and come up with some ideas about how we're going to learn this. (Teacher 1)

Additionally, teachers try out different approaches to talk about pupils’ emotional state. For instance, when some pupils were going through a difficult personal situation and needed more attention from the teacher, exploring ways to relate with these pupils was important to sustain contact. That is why the capacity of experimenting (like improvising) different ways of interacting with pupils must be taken as a serious competence to be developed during teacher training and professional development.

What does this child need? Sometimes it can be setting limits, sometimes it can be giving comfort, sometimes it can be encouraging the child, sometimes it can be something else […] You can also use physical situations, you can say OK let's sit down and talk about this. (Teacher 3)

Because teachers were trying out new things, reflecting about them frequently overlapped. Reflecting appeared in different ways, such as recollections, awareness, and thoughts about feelings, decision-making processes, personal experiences that had an impact on their teaching practice, or reflections about pupils' verbal and non-verbal feedback to adjust interpersonal interactions:

The real time feedback that they’re giving to me in our classroom and how they're reacting to me and to the other pupils there. And where the cooperation goes nicely, they give advice and support each other. Then I can see that everything is working fine. But of course, you have to know what you’re watching. (Teacher 1)

The reflections become crucial in cases when something goes wrong in their interactions with pupils. The most common situation was when they approached pupils too hard after a problematic event – later regretting it. The participants indicated that the hard work is to learn how to deal with their own emotions in such cases and how to avoid them in the future.

Sometimes in a situation when I have been reacting too fast, I have noticed that it's not good. […] The teacher also must learn to face their own negative feelings and to face the children's negative feelings towards the teacher. […] Think why the child is doing this and that, and sort of rationalize it and think. ‘Did I do something?’, this is the natural question, I think, but are there other reasons why the child is doing this? […] I have the feeling one seems to need to think about it more, and sometimes you think more when you have made yourself sort of stupid […] And that's again a process, how can you avoid that in the future. (Teacher 2)

Importantly, the teachers were aware that eventually such disturbances could affect how the child feels in the classroom, which could further impact the child's learning. This finding confirms Frymier and Houser (Citation2000) study on how a positive teacher–student relationship facilitates affective learning, which in turn enhances cognitive learning.

Teachers also reported reflecting when they needed to adapt old practices to new educational settings and approaches, confirming Grosemans et al. (Citation2015) study that renovation of school building, curriculum reform, and shifts of pupils are changes that require teachers to develop new perspectives of interactions. When a participant changed his class, he thought: “I spent 6 years with that class and when I knew, now I’m going to start with new pupils, I was thinking what would I like to change, what I’d like to do in a different way” (Teacher 5). All these reflections corroborate previous studies about how teachers’ reflections support informal learning (Hoekstra et al., Citation2007; Kwakman, Citation2003; Kyndt et al., Citation2016).

The most relevant strategy to learn how to build positive interactions with pupils was learning by doing on daily interactions, because of the practical and relatively fast learning outcomes it gives during teachers’ everyday routines (Kyndt et al., Citation2016; Thurlings & Brok, Citation2017). These strategies were analysed in detail according to the subcategories emotional support, classroom organization, and instruction support.

Everyday practices of providing emotional support to pupils, such as (1) showing sensitivity, (2) building a positive climate, and (3) taking the pupils’ perspective into account were the most important actions reported by the participants. First, showing sensitivity means not only to be attentive to pupils’ academic and socio-emotional levels of functioning, but also actively to respond to their needs. According to the participants, teachers need to analyse what they are observing from daily pupils’ interactions and corporal expressions, so that they can use them to adjust their behaviour accordingly. Nevertheless, selecting the suitable action to address the specific needs of their pupils according to each situation can also be challenging.

Teachers usually know if something special has happened in the family, at least I try to follow the situation, what's going on there, and try to adapt my way, what to say or how I want to contact the child. […] to decide what kind of interactive things would be suitable in this situation. (Teacher 3)

The participants also recognized the importance of being aware of their own verbal and body language towards the pupils. This finding underlines how communication skills that strengthen the perception of closeness between persons are crucial for positive teacher–pupil relationships.

Just now I’m practicing, it's basically words and, of course, […] my expression and my face. How does my face look? Do I look angry, or irritated? Of course, my voice, if they have done something wrong, how do I express myself? […] In every case, how I react when they talk to me. (Teacher 5)

Second, building a positive climate in the classroom is achieved by strengthening the connection between teacher and pupils through horizontality in conversations, trust, and life history sharing. One teacher illustrated the importance of differentiating the communication with each pupil, because it integrates the personal characteristics of pupils into the group and recognizes their individual contributions to the educational process: ‘I did communicate, like in the same way with everybody, but now I need to do things in a different way with different pupils’ (Teacher 5).

The participants also explained that to develop horizontal relationships with pupils, teachers must take the first step, showing trust and giving pupils autonomy. For example, teachers delegate tasks to pupils that demand responsibility, without controlling how the pupils fulfil the tasks. “The cooperation builds trust, and trust is very important here because pupils are very free in the school. If I send them to our B hall and I trust them that they’re doing what we agreed that they would do there, that's why the trust is very important” (Teacher 1).

The participants were aware that some pupils could break their trust, demanding further intervention. Anticipating the possibility of misbehaviour was a strategy to deal more efficiently with possible frustrations, enabling themselves to better face the break of trust and discuss the situation with pupils. However, they would still take the first initiative of trust. This report aligns with Lasky (Citation2005) study on teacher willingness to be vulnerable with students in order to build up trust with them.

Strong connections between teachers and pupils develop in two directions. Hence, teachers not only should ask pupils to share their personal interests, but also accept pupils’ inquiries concerning their lives. This signalizes trust by sharing valuable personal information. “If I want to be close to my class, then I have to tell them things about me. […] then you’re able to get closer to the children and have more impact” (Teacher 2). This connection between teacher and pupil allows pupils to feel safe, which in turn facilitates their learning process and general growth, because the pupils are not afraid of being themselves or making mistakes. “At first, they need to feel themselves emotionally safe. […] It's not possible to grow, if they cannot be what they really are” (Subject 4).

Third, the interviewees stressed the relevance of taking pupils’ perspectives into account through actively promoting dialogues and seeking feedback, both in dyads and with the whole class. Emphasizing pupils' interests and points of view and taking these into consideration to build daily classroom activities showed relevance to support a positive atmosphere and student-centred learning environment. “In my work, that's one thing I try to do: give them time. Every time they want to tell me something, stop and listen. Make it important, ask some questions. […] OK, ah that's really cool” (Subject 5).

Though the low frequency of the classroom organization and instructional support codes, managing behaviour and integrating different instructional formats and learning methods appeared to strengthen teacher–pupil relationships. Regarding managing behaviour, setting limits and clarifying behavioural expectations were mentioned as important strategies to keep these interactions functional and positive, because both teachers and pupils have the sense of order and partnership (Hamre et al., Citation2013). “I have also trained my pupils. […] They know what I want them to do and they know how to cooperate with me” (Teacher 1). When these expectations are broken, discussions between the involved parties are conducted in order to correct the damage and adjust new expectations to more realistic levels. These negotiations between teachers and pupils were reported to build progressively stronger bonds.

Regarding the application of different learning methods, the participants mentioned that group work and surprising learning activities make pupils excited and, consequently, they enjoy being at school. Additionally, bringing extra equipment to the classroom to try them out also appeared to mediate teacher–pupil interactions, overlapping with the previous category experimenting. However, more important than just bringing something into the class is how to connect the equipment within the classroom context and children's interests. “[…] those equipment or animals or pictures or something, they're not so important, it's more important how you act with those things” (Teacher 1).

Briefly, the teachers’ learning strategies showed a broad range of variety. CBC, reflecting, and learning by doing with an emphasis on teachers developing sensitivity for pupils and building up a positive climate, were the most relevant strategies. Surprisingly, despite all these strategies, the participants perceived that their teacher–pupil interactions are mainly based on teachers “being themselves”, which will be discussed next.

3.1.3 Above All, Authenticity Underlies Teacher–Pupil Interactions

The code authenticity was described spontaneously by the teachers as both an intrinsic personal factor and a work tool that not only contribute to, but rather base their interactions with pupils. “I’m here just what I am. And the other teachers also […] To be yourself is a very important tool to build trust between teacher and pupils” (Teacher 1).

Therefore, authenticity comes into play as a factor that builds up trust. For the participants, “being yourself” is a critical part of their teacher identity, because it is a teacher's role to integrate personal and professional selves between teacher and pupils in order to create a sense of community, a safe classroom environment, and affective learning (Day et al., Citation2006; De Bruyckere & Kirschner, Citation2016; Lasky, Citation2005). Stressing the importance of this factor, when participants mentioned some need to improve their interactions with pupils, to achieve that, the teacher's self must be changed in a way that teachers need to “be true” (authentic) to themselves, to their pupils, and across all the areas of their lives.

[…] If I want to make some changes, the changes must come from me. I have to change a little bit first […] I’m the same person everywhere. I need to do this thing also in the teachers' room and try to do this also in my home, it's very difficult. (Teacher 5)

Such a holistic modulation into the teacher personal and professional lives is evaluated as a deep and difficult change to be achieved to improve teacher–pupil interactions. Having this in mind, the participants were asked about possible changes in the way they interact with pupils over their career. The teachers stated unanimously that their interactions did not change significantly over time, because their teacher–pupil relationships are based on the fact that “they are just being themselves” – and that does not change over time.

Actually, I wouldn't say that it changed that much, because who I am is also very much the teacher I am […] Of course, it might be something I forgot, but I don't remember that my way of interacting has changed during the years. (Teacher 2).

This finding is relevant because it highlights contradictions inside the teachers' perceptions. Regardless of their constant learning strategies to build positive interactions with their pupils, the participants nevertheless perceive that the core aspects of their teacher–pupil interactions do not change over time. Such a general and unclear feeling of learning can be attributed to the characteristics of informal learning: its everyday nature might leave teachers unaware of changes they have been through (Hoekstra et al., Citation2007). Therefore, in an apparent contrast to the findings described previously, the teachers reported that they did not have to learn how to interact with their pupils, because the way they do it comes naturally from them being authentic, true to themselves and to their pupils. Consequently, this authenticity is connected to their identity as a teacher and as a person – which is, in turn, predominantly stable over time. The participants’ reports of lack of radical changes in their interactions with pupils in the long-term confirm the finding of Brekelmans et al. (Citation2005) that teacher–pupil relationships are predominantly stable over time, with some small variations in the beginning of the teachers’ careers.

Summarizing, the category teacher identity emphasized how teachers’ capacity for being themselves at work and the interrelationship between their personal and professional identities are fundamental for building positive interactions with pupils. The participants comprehend that their relationship with pupils is stable throughout their careers and that their learning supports – but does not alter significantly – their interactions with pupils over time, because these interactions are grounded in the teacher's authenticity.

4. Conclusion

This study collected an elaborated understanding of a group of experienced teachers who perceived themselves to constantly build positive interactions with their pupils. In sum, three groups of multidimensional factors compounded the resulting exploratory framework Teachers learn by interacting: professional agency elements that drive teacher's learning; the active learning strategies that support the building of positive teacher–pupil interactions; and the teacher identity factor that ultimately underlies teacher–pupil interactions. On the one hand, the teachers' motivation towards supporting pupils’ growth, and their efficacy beliefs in learning activated their learning process. In sequence, their learning strategies showed a broad range of variety, stressing the importance of learning by sharing understanding and aligning practices with the whole school community, as well as by reflecting while employing classroom routines and experimenting new activities with pupils. On the other hand, the participants regarded that their learning processes support their interactions with pupils, but do not radically alter their interactions over time, because these interactions are grounded in their intermeshed identity as a teacher and as a person.

This study contributed to the theory building in the area of teacher learning by integrating the TPAL framework with the TTI model to address the adaptive expertise (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006) that teachers must develop to interact with pupils. In practice, this means that teachers need to engage in daily and exceptional actions that increase their understanding about the pupils, so they can make attentive decisions in the light of the pupils’ needs, while accounting for individual differences and the interactions between growth, learning, and cultural contexts (Bransford et al., Citation2005). Pre- and in-service education programs can also resort to our anecdotal evidence for the training of concrete strategies on learning to interact with pupils, such as engaging pupils to bring their interests into the classroom routines, peer mentoring for challenging situations, role playing appropriate verbal and non-verbal responses to pupils’ behaviour, personal history telling, among others. They comprise transferable skills that support a deep pedagogical understanding of the learner and his/her individual learning process. Therefore, they are relevant for sustaining affective and effective pupil learning and supporting teacher learning on pupils’ individual developmental paths.

Additionally, our study highlighted the need to integrate teacher identity to the process of teachers building positive interactions with pupils. The factors that sustain such identity and positive teacher–pupil interactions include how much teachers are true to their pupils and to themselves (authenticity). This reflects how relevant is for teachers to engage in self-awareness processes regarding their own image as a teacher for themselves, as well as what they consider is their role as a teacher for their pupils’ lives.

Further studies should be conducted regarding how teacher identity and professional agency can be reinforced through everyday work practices and organizational culture in the schools (Lasky, Citation2005), so that engaging and sustaining positive relationships in an everyday manner can be supported not only by personal factors, but structural factors as well. We conclude that teacher's learning about interacting with pupils is a complex phenomenon that must be understood in conjunction with its contextual facets. Therefore, we suggest that other differential perspectives should be considered to approach such a multidimensional process (Hamre & Pianta, Citation2001; Hoekstra et al., Citation2007; Soini et al., Citation2016).

4.1 Limitations

The sample size of the survey and the interviews’ findings are not representative neither generalizable. However, the purposeful sampling phase of the research aspired to capture “best practices” from the professional community and increase the validity of the findings, therefore, aiming for their reliable transferability (Neuendorf, Citation2016). Additionally, the fact that this research is based solely on teacher's self-report is also a limitation, because learning in informal contexts occurs partly implicitly. Therefore, parts of it cannot be easily apprehended in interviews (Hoekstra et al., Citation2007). Future studies with questionnaire applications and classroom observations must be undertaken in order to strengthen the research findings.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bransford, J., Derry, S., Berliner, D., Hammerness, K., & Beckett, K. L. (2005). Theories of learning and their roles in teaching. Preparing Teachers for a Changing World: What Teachers should Learn and be able to do, 40–87.

- Brekelmans, M., Wubbels, T., & van Tartwijk, J. (2005). Teacher–student relationships across the teaching career. International Journal of Educational Research, 43(1–2), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2006.03.006

- Bruyckere, P. D., & Kirschner, P. A. (2016). Authentic teachers: Student criteria perceiving authenticity of teachers. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1247609

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Assessing teacher education: The usefulness of multiple measures for assessing program outcomes. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(2), 120–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487105283796

- Day, C., Kington, A., Stobart, G., & Sammons, P. (2006). The personal and professional selves of teachers: Stable and unstable identities. British Educational Research Journal, 32(4), 601–616.

- Dicke, T., Elling, J., Schmeck, A., & Leutner, D. (2015). Reducing reality shock: The effects of classroom management skills training on beginning teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 48, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.01.013

- Edwards, A. (2005). Relational agency: Learning to be a resourceful practitioner. International Journal of Educational Research, 43(3), 168–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2006.06.010

- Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., & Hökkä, P. (2015). How do Novice teachers in Finland perceive their professional agency? Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(6), 660–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044327

- Finnish National Board of Education. (2016). National core curriculum for basic education 2014.

- Frymier, A. B., & Houser, M. L. (2000). The teacher-student relationship as an interpersonal relationship. Communication Education, 49(3), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520009379209

- Gamliel, T., & Gabay, N. (2014). Knowledge exchange, social interactions, and empowerment in an intergenerational technology program at school. Educational Gerontology, 40(8), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2013.863097

- Gaskell, G. (2000). Individual and group interviewing. Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound, 38–56.

- Grosemans, I., Boon, A., Verclairen, C., Dochy, F., & Kyndt, E. (2015). Informal learning of primary school teachers: Considering the role of teaching experience and school culture. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.011

- Hamre, B. K., Pianta, R. C., Burchinal, M., Field, S., LoCasale-Crouch, J., Downer, J. T., Howes, C., LaParo, K., & Scott-Little, C. (2012). A course on effective teacher-child interactions: Effects on teacher beliefs, knowledge, and observed practice. American Educational Research Journal, 49(1), 88–123. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831211434596

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72(2), 625–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00301

- Hamre, B. K., Pianta, R. C., Downer, J. T., Decoster, J., Mashburn, A. J., Jones, S. M., Brown, J. L., et al. (2013). Teaching through interactions: Testing a developmental framework of teacher effectiveness in over 4,000 Classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 113(4), 461–487. http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/psy_fac

- Henning, J. E., Rice, L. J., Dani, D. E., Weade, G., & McKeny, T. (2017). Teachers’ perceptions of their most Significant change: Source, impact, and process. Teacher Development, 21(3), 388–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2016.1243570

- Hoekstra, A., Beijaard, D., Brekelmans, M., & Korthagen, F. (2007). Experienced teachers’ informal learning from classroom teaching. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 13(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600601152546

- James-Wilson, S. (2001). The influence of ethnocultural identity on emotions and teaching. In Annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association (Vol. 4). New Orleans.

- Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325693

- Korthagen, F. A. J. (2010). Situated learning theory and the pedagogy of teacher education: Towards an integrative view of teacher behavior and teacher learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(1), 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.05.001

- Kwakman, K. (2003). Factors Affecting teachers’ participation in professional learning activities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(2), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00101-4

- Kyndt, E., Gijbels, D., Grosemans, I., & Donche, V. (2016). Teachers’ everyday professional development. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1111–1150. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315627864

- Lasky, S. (2005). A sociocultural approach to understanding teacher identity, agency and professional vulnerability in a context of secondary school reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(8), 899–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.003

- Lohman, M. C. (2006). Factors influencing teachers’ engagement in informal learning activities. Journal of Workplace Learning, 18(3), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620610654577

- Maxwell, J. A. (2004). Using qualitative methods for causal explanation. Field Methods, 16(3), 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X04266831

- Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland. (2016). Government integration programme for 2016–2019 and government resolution on a government integration programme. Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment.

- Neuendorf, K. A. (2016). The content analysis guidebook. Sage.

- Powell, W., & Kusuma-Powell, O. (2011). How to teach Now: Five keys to personalized learning in the global classroom. ASCD.

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2015). Teachers professional agency and learning-from Adaption to active modification in the teacher community. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(7), 811–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.995483

- Reeve, J., & Su, Y.-L. (2014). Teacher motivation. In The Oxford handbook of work engagement, motivation, and self- Determination theory, 349. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.26082-0

- Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques. Political Research Quarterly, 61(2), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907313077

- Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2016). What if teachers learn in the classroom? Teacher Development, 20(3), 380–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2016.1149511

- Takahashi, S. (2011). Co-constructing efficacy: A ‘communities of practice’ perspective on teachers’ efficacy beliefs. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(4), 732–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.12.002

- Thurlings, M., & Brok, P. d. (2017). Learning outcomes of teacher professional development activities: A meta-study. Educational Review, 69(5), 554–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2017.1281226

- Titsworth, S., McKenna, T. P., Mazer, J. P., & Quinlan, M. M. (2013). The bright side of emotion in the classroom: Do teachers’ behaviors predict students’ enjoyment, hope, and pride? Communication Education, 62(2), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2013.763997

- Vähäsantanen, K., Räikkönen, E., Paloniemi, S., Hökkä, P., & Eteläpelto, A. (2018). A Novel Instrument to measure the multidimensional structure of professional agency. Vocations and Learning, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-018-9210-6