ABSTRACT

In this study, we explore teachers’ professional space as an alternative to, and/or expansion of earlier conceptualizations of teacher autonomy. Professional space is here understood both as an objective space with e.g., physical, juridical, economic features, and as the teachers’ subjective negotiation of this objective space, where teachers are viewed as producers of professional space (subjective space). Based on an analysis of storyline interviews with teachers from Finland, Norway and the US we argue that professional space, both as an empirical entity and as a theoretical construct, opens up exploration of external and internal factors, as well as the multi-dimensionality of the factors over time and beyond physical space which influence teachers’ decision-making capabilities.

Introduction

In both Europe and North America, there has been increased political involvement in steering and controlling the teaching profession over the last couple of decades. A prominent international trend has been to increase the emphasis on student performance and on the external control of professional work (e.g., Ball et al., Citation2012; Biesta, Citation2010; Cribb & Gewirtz, Citation2007; Mausethagen, Citation2013a). Policies developed with the purpose of enhancing students’ performance are now internationally recognized as accountability policies. Teacher autonomy has become a significant topic of discussion, largely because of accountability policies that, some argue, limit the professionalism, authority, responsiveness, creativity and effectiveness of teachers (Buchanan, Citation2015). The need for professional autonomy has been associated with positive effects on teachers’ work, such as e.g., work satisfaction, efficiency, fewer dropouts and the improvement of student outcomes (e.g., Salokangas et al., Citation2019).

In this study, we explore teachers’ professional space as an alternative and/or expansion of teacher autonomy both empirically and conceptually. The three cases included in this study are carefully selected due to the different framing and regulation of the teaching profession. Finland can be considered the most permissive regarding teachers’ professional freedom. Norway regulates its teachers more, and there are extensive educational policies in the United States that determine how accountability mechanisms are introduced into teachers’ work. We will expand on the three case-contexts below.

Traditional approaches to professional autonomy have tended to explore the influence of externally (political) driven accountability policies on teachers’ professional practice. We argue that by approaching teachers’ decision-making capacities through the lens of professional space we will be able to explore the dynamics between externally- (political and top-down) and internally- (professional and from within) driven accountability forces in teaching practice in the US, Finland and Norway.

Professional space is understood in this study as objective space, such as the school’s internal and societal boundaries, as well as the subjective negotiation of this objective space by teachers (Oolbekkink-Marchand et al., Citation2017) and how additionally teachers are producers of professional space. This puts teachers at the center of the study, in contrast to the more traditional top-down policy approaches that are often used when exploring e.g., teacher autonomy.

Global accountability policies are initiated and negotiated quite differently in different country contexts (e.g., Pettersson, Citation2014; Salokangas et al., Citation2019). While we know that in both Europe and North America, there has been increased political involvement in steering and controlling the teaching profession in various ways, Finland by contrast has held onto the non-regulative, non-controlling and non-testing tradition for decades. Thus, there is a need for comparative research that analyses teachers’ professional space, opening up further exploration of the personal, communal, political, administrative, student-related, physical and time-related levels and factors that influence teachers’ description-making capacities.

We pose the following main research question in this article: How do Finnish, Norwegian and US teachers experience professional space? Hence, we first explore the concept of teachers’ professional space empirically among the Finnish, Norwegian and US teachers. Based on this empirical analysis, we then discuss how professional space may expand on earlier conceptualizations and units of analysis of teachers’ professional autonomy.

Since we explore teachers’ professional space as an alternative and/or expansion of teacher autonomy both empirically and conceptually, we will in the next section firstly give a brief configurative overview of the most recent research combining empirical and conceptual discussions on teacher autonomy. Secondly, we look at professional space as an analytical framework for exploring teachers’ decision-making capacities.

Teachers’ “Professional Autonomy” and Teachers’ “Professional Space”

A vast body of literature has empirically explored the phenomenon of teacher professional autonomy (e.g., Erss, Citation2015; Ingersoll, Citation2009; Mausethagen, Citation2013a, Citation2013b; Salokangas & Ainscow, Citation2017; Salokangas et al., Citation2019; Wermke & Forsberg, Citation2017). A prevailing characteristic of these studies is that their point of departure is that teachers’ autonomy is connected to the degree of external control and consequently the teachers’ amount of say in their daily work. This may also be documented in more conceptual work, such as Frostenson (Citation2015), who argues that teacher autonomy needs to be studied at the organizational level due to the managerial ideologies that are used to evaluate and influence the nature of teachers’ work. Mausethagen and Mølstad (Citation2015), on the other hand, bring in aspects of external control and self-governance as control of individuals and/or collective practices, product and/or process control, and teachers’ capacity to safeguard and justify their own knowledge base. They found that conceptualizations of teacher autonomy need to move beyond traditional dichotomies and that they are influenced by both internal (i.e., professional, such as relating to a professional knowledge base and ethical codes) and external (i.e., political) accountability pressure (Mausethagen & Mølstad, Citation2015).

Several fruitful attempts have been made to nuance and crystallize the concept of teacher autonomy (e.g., Cribb & Gewirtz, Citation2007; Frostenson, Citation2015; Wermke & Forsberg, Citation2017; Wermke & Höstfält, Citation2014), recent studies contributing both empirically and conceptually to the discussion on teacher-perceived autonomy by Wermke et al. (Citation2019) and Salokangas et al. (Citation2019), who propose an approach to teacher autonomy as a far more multi-dimensional and context-dependent phenomenon than earlier studies. They have developed a matrix that captures both teachers’ autonomy domains (horizontal axis) and levels or dimensions of autonomy (vertical axis). We propose in this article that an alternative approach or expansion of studies of professional autonomy may be a teachers’ professional space, which opens up for positioning the teacher more actively in their roles as decision-makers rather than being (purely) determined by external factors. It allows one to explore teachers’ as actors manoeuvring in their professional space but also to explore the professional space in which they are manoeuvring. The reason is that teachers’ manoeuvring is better understood against the background of the manoeuvring space than as autonomous actions (Oolbekkink-Marchand et al., Citation2017; Priestley et al., Citation2015). Oolbekkink-Marchand et al. (Citation2017) define professional space, on the one hand, as space where teachers have to obey rules (i.e., policy documents, national curriculum, local rules etc.) in their practice, but at the same time, “teachers can be seen as active interpreters of the school context and the space they have, to act on their own personal goals” (Oolbekkink-Marchand et al., Citation2017, p. 38).

In educational research, objective space is often understood normatively in the sense that political, legal and economic decisions create given structural frames and boundaries for professional practice (Oolbekkink-Marchand et al., Citation2017). Such an account rests on the belief that political, legal and economic decisions have an objective status, that they have the same meaning in different contexts and practices. Lefebvre (Citation1991) and Schatzki (Citation2010), argue that people do not only understand a given objective space subjectively but that space can also be understood as socially produced. Teachers produce space in and through their professional activities. Professional space is created by the way teachers enact policies and other environmental factors in an active and indeterminate way. This means that the conception of professional space includes both the space environment and active negotiation. Professional space is made in active manoeuvring, and active manoeuvring is made in professional space in a dynamic and ecological manner.

Time is also of interest (Oolbekkink-Marchand et al., Citation2017; Priestley et al., Citation2015; Schatzki, Citation2010). The concept of output assumes a future and a connection between the past, the present and the future. The future constitutes the professional space of teachers. Traditionally, the past is also important in teachers’ professional practices, for instance by legitimizing practices by referring to tradition and by thinking of education as passing knowledge from the past to the present. In this project we will analyze how teachers’ use and making of time constitutes their professional space. Is their time-orientation future-, present- or past-oriented? Is their future-orientation near (the end of the term) or distant (the good life of the students)?

Below we continue by exploring empirically how professional space, both as an empirical entity (through the analysis of the three cases) and a theoretical construct (in the discussion) opens up for exploring external and internal factors, as well as the multi-dimensionality of the factors that over time and beyond physical space influence teachers’ decision-making capabilities.

The Political and Professional Contexts of the Three Cases

This study explores teachers’ professional space in three different contexts: Finnish, Norwegian and the US, the latter in the state of California. Finnish teachers have a great degree of pedagogical autonomy and freedom in their work (e.g., Niemi, Citation2015; Tirri, Citation2014). Finland has held on to this non-regulative, non-controlling and non-testing tradition for decades. As Saari et al. (Citation2014, p. 195) suggest, “the ‘success’ of education might be dependent on the autonomy of teachers and on a less centralized and standardized curriculum”. Since the 1980s decentralization in governance has led to the abandonment of school inspections, controls have been loosened, and teachers have been able to decide independently how to implement the curriculum (Saari et al., Citation2014, p. 194; Simola, Citation2015). Thus, the Finnish National Core Curriculum gives very broad guidelines and does not restrict the pedagogical autonomy of teachers, nor does the government issue standardized testing on a yearly or national basis (e.g., Simola, Citation2015). Finnish teachers take part in school development through, for example, curriculum development and administration at the local level. Schools can design their work independently, and teachers do not have to worry about someone auditing their skills or their ability to teach. Nor are the teachers evaluated. The principals lead the school and its teachers, but there is no evaluation or criteria for a good teacher or good teaching (Jyrhämä & Maaranen, Citation2016). There is only one high-stakes test in Finland, the matriculation exam, which about half of the population (at approximately 18 years of age) takes (Kupiainen et al., Citation2009).

In Norway, the teaching profession has since the turn of the millennium increasingly been steered by accountability policies, frameworks and guidelines. The curriculum design is outcome-based. However, the accountability policies can be described as “softer” than in countries such as the US and the UK (Mausethagen, Citation2013b). In line with this emphasis on outcomes, the national testing of basic skills was introduced in 2004. School inspection is part of the Norwegian educational system (e.g., Hall, Citation2017). While the authorities do not publish league tables, the media announce the national ranking of schools on an annual basis (Tveit, Citation2014). Systematic use of data derived from testing is seen as important to meet the needs of the students, but leads to performance pressure (Mausethagen et al., Citation2020). However, there is also great variation between local authorities at the municipality level about carrying out various national accountability initiatives. In the most recent curriculum reform, Curriculum Renewal 2020, (introduced after the data in this article were collected), the emphasis on and number of learning outcomes are slightly reduced, and teachers report that they are optimistic about a larger space for decision making.

In the case of the US, the state of California will be used as an example case. It is important to note that different states have different structures and frameworks in place for their teachers and school systems. However, a common characteristic is that the educational system in the US is rather strongly structured and framed by accountability policies (Mehta, Citation2014). While there is no national curriculum in the United States, states and school districts, do require that certain standards are used to guide school instruction. In addition, federal law mandates that state standards need to be developed and improved for states to receive federal assistance. Therefore, each state has developed content standards for each school subject. Since the early 1980s a vast body of policy reports has been published in the US on the need to improve the quality of teaching and student results (Mausethagen, Citation2013b), such as No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top and Our Future, Our Teachers, Every student succeed etc. Many accountability policies have been introduced at all levels of the educational system (Cochran-Smith et al., Citation2013). Value-added measures are used to estimate or quantify how much of a positive (or negative) effect individual teachers have on student results. Such measures are reported in studies on, for example, how value-added measures have influenced practice (Grossman et al., Citation2013) or how teachers and principals trust classroom observation more than value-added measures (Goldhaber, Citation2015; Jiang et al., Citation2015). However, value-added measures are increasingly questioned by teachers, researcher and policy makers across the US (Amrein-Beardsley & Holloway, Citation2019).

Thus, these three cases are selected due to their differences, ranging on a scale from little or no control to heavily formal and external control schools and teachers. Norway holds an intermediate position on the scale, while Finland is especially interesting on account of its high ranking in students’ test results. Finland has overall chosen a different path than most counties in the world.

Storyline Method

Based on Beijaard et al. (Citation1999, p. 47), the storyline method fits into the narrative research tradition because of its emphasis on teachers’ stories. Beijaard et al. (Citation1999), who were inspired by Gergen (Citation1988; Gergen & Gergen, Citation1986), were pioneers in using the storyline method in the field of teaching and teacher education. A storyline represents a teacher’s evaluation of a series of experiences or events on the vertical line of a graph and is plotted in time on the horizontal line, i.e., the number of years the individual worked as a teacher.

The Storyline Method in This Study

The authors are “natives” of Finland and Norway. Both authors resided three and twelve months respectively in California doing ethnographic work. Here they observed classroom work and teacher union meetings, and interviewed principals, school administrators and representatives from the public and the private sector to avoid cultural biases (Afdal, Citation2019) when collecting and analysis the storyline data.

We adopted a similar storyline method as that used in a study by Oolbekkink-Marchand et al. (Citation2017). Our instructions for a storyline were inspired by Oolbekkink-Marchand et al.’s (Citation2017) study:

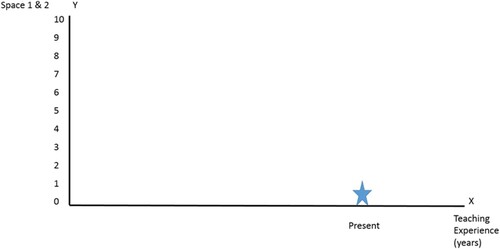

Below you see a graph [cf. ] with on the x-axis the time you have been teaching in years. On the y-axis we want to ask you to draw two lines. Try to recall key experiences during your career that have affected your professional space.

For the first line, we ask you as a teacher to think about the space you perceive you have been given in your school as a teacher. This may relate, for example, to space you perceive to be formal in your work, or informal in your work. Think about what you find important in your work in relation to formal and informal space. Draw a line in which you indicate the “amount” of experienced space you feel as a teacher throughout the year(s) you have been teaching.

For the second line, we ask you as a teacher to think about your utilization of the space you experience as a teacher. To what extent have you as a teacher utilized this space? To what extent have you utilized this space alone or collectively? Draw a line in which you indicate the “amount” of space you utilized as a teacher throughout the year(s) you have been teaching.

After you have drawn these two lines, please explain your “ups” and “downs” in the lines. For example, what caused you to feel this amount of space during this period? What contributed to the fact that you experienced space? What caused you to use this amount of space? Can you reflect on the differences between given and utilized space?

We first discussed the concepts “professional space”, “given space” and “utilized space” with the teachers. When the individual teacher seemed comfortable with the concepts and the task, we left them alone for a few minutes to work on the graphs. When they signaled that they were ready, we asked them to tell us about the two graphs and motivate their “ups and downs”, especially discussing the points where curves changed. Finally, we questioned them about the difference or similarities between the graphs and asked for their reflections.

We chose storyline as our research method for several reasons. Firstly, the method allowed us to explore both so-called “objective”, “top-down” and external factors as well as the subjective and constructed aspects that influence teachers’ professional space. Secondly, the method allowed us to capture aspects that influenced teachers’ professional space over time and across contexts. Finally, using the storyline method also safeguarded comparable entities (Afdal, Citation2019) to a greater extent across individual teachers’ stories as well as across the three cases compared to a more open narrative approach.

The Participants and Data of This Study

The participants of this study were 17 Finnish, 17 Norwegian and 15 Californian teachers. Of the Finnish and Norwegian teachers, nine were elementary and eight high school teachers, whereas among the US teachers seven were elementary and eight high school teachers. An additional selection criterion was that the pool of teachers in each case should be subject teachers within the natural sciences, languages and arts. We used snowball sampling in our selection of teachers. The length of their experiences as teachers varied greatly, from four years to over 30 years. Gender was distributed quite equally between the countries and also represents the general trend of gender distribution of the profession: four Finnish and Norwegian and three US participants were male. It is important to note that the three municipalities where we conducted our research may be categorized as upper middle-class communities where student results are above average.

The data consist of storyline graphs (cf. .) and the stories the teachers told after drawing the graphs. The stories were recorded, and were transcribed verbatim. In this article, the teachers have been given a code, consisting of a number from 1 to 49, abbreviations for each country, NO, FI and US. Some of the teachers drew their storylines into the future and speculated about what might happen, while others did not. Some of the teachers also gave more than one reason for exceeding or not using all the given space ( and ), and that is why the numbers in the tables do not add up to the number of teachers participating in this study. The number of teachers interviewed does not open up for generalization to national or state contexts, however we argue that our analysis opens up for an argumentative discussion on the implication of using professional space as an analytical lens in three different educational contexts.

Analytical Strategy

In this qualitative study we used inductive content analysis. The graphs were interpreted together with the stories the teachers told about their career paths and the experiences they had during their careers. The data were analyzed using data-driven content analysis; thus an open coding scheme was used based on an inductive approach without specifying a theoretical framework. All stories were read through several times and key experiences and significant turning points were identified. Firstly, these key experiences were searched for reasons for using a certain amount of professional space contrasting it with the amount of given space. Secondly, they were searched for factors that affected the amount of given space they had experienced in their work. A combined matrix of reasons and factors was formed. The reasons and factors were placed into main categories (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008, p. 111; also Dey, Citation1993).

We analyzed the data from each country context separately for the purpose of comparison, but also for pragmatic reasons such as language. The data in each case have been treated as one sample, and we do not make a distinction between teachers from elementary and high school within each case. We did this for two main reasons. Firstly, we did not find any significant differences between the teachers from different school levels within each case, and secondly, the number of teachers from each school level is rather small. Further, treating elementary and high school teachers as one sample makes our cross case analysis more robust.

Results of the Storylines

The results are presented in the following order. Firstly, we present the general trends in utilized and given spaces; secondly, we present the reasons for exceeding, not exceeding or using all the given professional space; and thirdly, we present the factors that the participants have identified as being significant for a lot of and for limited given space.

General Trends in Utilized and Given Spaces

Exceeding or not Exceeding the Given Space

The analysis of the storyline graphs began with a rough categorization of the lines based on crossing the given space line by the utilized space line. The three categories were “Exceeds given space”, “Crosses the lines a little”, and “Does not exceed given space”.

The storyline graphs were grouped into the “Exceeds given space” category if the space was exceeded more than half of the timeline. In the “Crosses the lines a little” category, the storyline graphs were grouped if the two lines crossed at some point or briefly on occasion. In the category “Does not exceed given space”, the storyline graphs were grouped when the utilized space line never exceeded the given space line. shows the distribution of the storyline graphs in percentages according to each country.

Table 1. Distribution of storyline graphs.

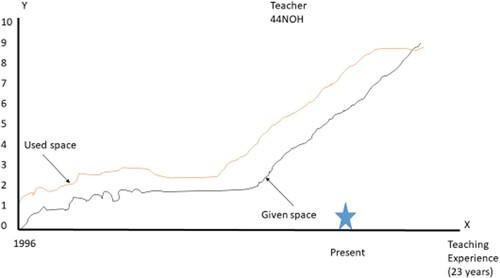

As can be seen from , the Norwegian teachers exceeded the given space most, although the difference with the US teachers is not large. The Finnish teachers differ from the Norwegian and US teachers by not exceeding the given space so much. The Finnish teachers, however, cross the line a little more than the US and Norwegian teachers. The biggest proportion of teachers that do not exceed the given space at all are the Finnish teachers. Below are examples of each type of storyline. In , a Norwegian high school teacher drew her utilized space line entirely above the given space line.

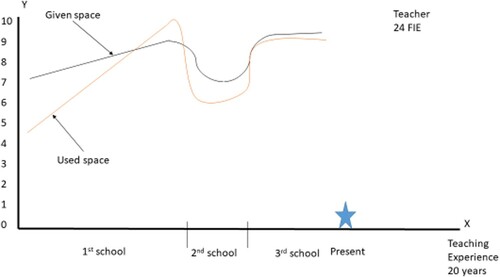

shows an example by a Finnish elementary teacher who crossed the given space line only briefly once during her 20-year career.

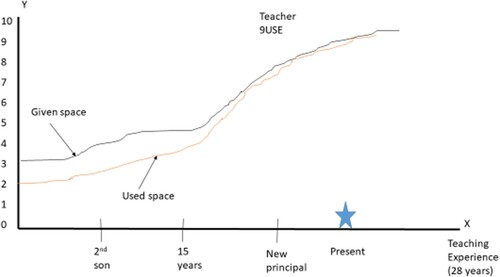

In , an elementary teacher from the US has drawn her utilized space line below or parallel to the given space line during her 28-year teaching career.

Reasons for Exceeding, not Exceeding or Using all the Given Space

Reasons for Exceeding the Given Space

In order to understand why the teachers did or did not exceed the given space, we categorized the reasons they gave. In the following, the reasons are categorized as school-level and personal-level reasons ().

Table 2. Reasons for exceeding the given space.

School-level Reasons for Exceeding the Given Space

Two kinds of school-level reasons appeared in the descriptions of teachers from all countries. They were trust from the principal and trust from the school community. This meant that if the principal and/or the school community trusted the teachers, they were able to work more freely and were even able to make adaptations in their work. One US elementary teacher explains his view of the trust the principal gave:

So in the beginning I really had a very supportive boss, I told you this story of how I took less money to work with her and turned down a job that I had to hopefully work with her … she would give us a very great degree of freedom and she would trust us … So she believed hire good people and give them freedom. 13US

I guess I feel that I am so, like people will trust me enough so I don’t feel like I’m, I don’t know, there is a level of trust or a belief in what I am doing so I feel like if I wanted to do … you know assign something brand new, that I wouldn’t get in trouble for it. You know I just feel like I could do that if I wanted. 7US

Personal-level Reasons for Exceeding the Given Space

Teachers from all three countries mentioned certain common reasons for exceeding the given space. Many participants said that with seniority/experience they felt they could do what they wanted. A Finnish elementary teacher describes how after about 10 years of teaching experience she knew how to do things:

I had a kind of secure feeling, so that I knew quite well how to do these things, so I didn’t really need to ask can I do this, so I know … sort of it became clear what I can do and in what ways. 24FI

Reasons for not Being Able or Willing to Use All the Given Space

The teachers also explained why they did not want or were unable to use all the given space (). There were reasons in common for all teachers, but also some reasons that only some countries shared as well as those that appeared in only one country.

Table 3. Reasons for not using all the given space.

School-level Reasons for not Using All the Given Space

Three Finnish teachers and one US teacher felt that they had too strict control at the school and for that reason they were unable to use all the professional space. Finnish and US teachers also said that the principal was the reason for not using all the space; in other words they felt that the principal was strict or non-supportive, as one Finnish high school teacher put it:

I started in X high school and it was such a strict school, and there was somehow a really strong hierarchy between teachers. And as a young beginning teacher, I somehow felt that I was put on a really short leash, and there were such strong people and the principal was so strict. I felt they didn’t give me space. 28FI

Personal-level Reasons for not Using All the Given Space

Especially in the beginning of their careers, the teachers mentioned that they were unable to use all the given space because they lacked confidence in themselves as professionals. Also, most of them mentioned that they were still novices, and therefore did not use all the professional space, as these two Norwegian teachers describe:

I started here in 1996. I worked a year in X city, then I think, maybe I didn’t take as much space. At that time, I felt very new and relied on the plans and structures already there. Although perhaps the space was large, I didn’t take much. 39NO

And then, when I started working, I was … then I was very nervous about making mistakes too, right? 38NO

Reasons for Using All the Given Space

The teachers mentioned reasons why they used all the space provided for them, in other words, they did not have reasons to go beyond or push boundaries ().

Table 4. Reasons for using all the given space.

School-level Reasons for Using all the Given Space

Teachers in all countries mentioned the principal as being a person who made it possible for them to use the given space to the maximum. Support from the community (principal, colleagues, or both) was also mentioned as a reason. Norwegian teachers mentioned that working closely with another teacher (cooperating teacher) helped them to increase the utilized space, whereas one became a team-leader in her own subject and was included in decision making more than before, and that made her feel that she was using all the given space.

Personal-level Reasons for Using all the Given Space

Being experienced enough or having a senior position in the community allowed the teachers to use all the professional space. Finnish and US teachers wanted to give the students as much as was in their power, which meant using all the possibilities or resources or creating better ones in order to give “extra” for the students. Confidence in oneself was mentioned by two Finnish and three Norwegian teachers. Finnish and Norwegian teachers mentioned that the teacher’s profession is one in which you need to obey laws and norms and follow rules and regulations. In other words, they considered that teachers could use all the given space, but not exceed it. Individual reasons mentioned by the teachers were also joining the Union, being enthusiastic about the work and beginning a pedagogical experimentation of not using text books at all in the teaching.

Factors for a Lot of or Limited Given Space

Factors for a Lot of Given Space

The teachers also described what factors had an effect on the amount of the given space. We categorized the factors as Administrative factors, Community-related factors, Student-related factors, Curriculum-related factors, and a Location-related factor ().

Table 5. Factors for a lot of given space.

In the administrative factors the significance of the principal was undoubtedly the biggest factor in encouraging a feeling of a great amount of given space. In the community-related factors, the support from colleagues was a factor for a lot of given space, which two US and two Norwegian teachers brought up. Finnish and US teachers mentioned that the school where they worked was a developmental school, which meant that the atmosphere was such that they felt they were given a lot of professional space. The Norwegian teachers mentioned sharing planning and shared responsibilities as factors for a lot of given space. In the student-related factors, for the US teachers, factors that caused them to feel that they were given a lot of space were high student achievement, which two teachers mentioned. This meant that when there was higher student achievement, they felt they had more freedom or not such a strict atmosphere. In the curriculum-related factors, for Finnish and Norwegian teachers the National Core Curriculum provided a feeling of a lot of given space. A Norwegian teacher described that her school was located geographically in such a place that provided more opportunities and the feeling of a lot of given space.

Factors for Limited Given Space

The teachers also revealed factors that affected their feelings of having limited given space (). These were categorized as Administrative factors, School-related factors, Curriculum-related factors, Student-related factors, and Community-related factors.

Table 6. Factors for limited given space.

As shows, the teachers from all three countries repeatedly mention the principal as a focal factor, this time, limiting their given space in the administrative factors. For the US and Norwegian teachers control from the school or district was a significant factor for limited professional space. Norwegian teachers mentioned several different factors for limited given space. Only the Finnish and US teachers mentioned school-related limiting factors, namely not having enough resources in the school, or working in a small school, whereas curriculum-related factors were mentioned only by the US and Norwegian teachers. The US and the Norwegian teachers also mentioned student-related factors, for instance lower student achievement, learning outcomes and that students are becoming more demanding. Only the Finnish teachers mentioned community-related factors.

The overview in further shows that it seems that most of the reasons given for limitation of space mentioned by the teachers may be related to the individual teachers work trajectories rather than to some local, national or cross-national trends among the teachers. The variation in and challenges with students are not mentioned as focal factors by many teachers. Another striking difference across all the categories is that the Finnish teachers mentioned fewer factors that limit their professional space than the Norwegian and US teachers. Finally, surprisingly few teachers across all three country contexts mentioned the curriculum, learning outcomes, documentation requirements and test regimes as limitations on their professional space.

Concluding Discussion

The empirical aim in this article was to explore teachers’ experience of professional space in three different political and professional contexts. Although their political contexts are different, teachers have traditionally been categorized as largely autonomous in Finland, “softly restricted” in Norway, and more extensively restricted in California. Firstly, in our analysis of teachers’ professional space in the three countries, how they utilized it and what factors played a role in experiencing the given space, had many commonalities. The general trends we found do to a certain extent reflect findings from earlier research on e.g., teacher professionalism and/or professional autonomy. The Finnish teachers experience a lot of space and trust; however, they are at the same time the most obedient when it comes to given space. Given and utilized space over the time of their career collapse into one dimension for most Finnish teachers. The difference between the US and Norwegian teachers are smaller than expected. Overall, the majority of teachers from both contexts are willing to exceed the given space if needed or when required both in terms of time and experience.

Secondly, we found that factors influencing professional space were mentioned by nearly all teachers. In all three country contexts professional space was argued for and distributed among administrative, community-related and student-related factors, as well as the curriculum, and location.

Thirdly, teachers in all three contexts show that the factors they raise as decisive for utilizing and developing professional space are anchored locally and in time more than being related to national or statewide policy frames and structures. Surprisingly few teachers in the three contexts mention the curriculum, learning outcomes, documentation requirements and test regimes as strong limitations on their experience and construction of professional space. The US and Norwegian teachers, however, did feel that accountability issues were more pressing. Mausethagen (Citation2013a), Buchanan (Citation2015), and Löfgren (Citation2015) have found similar restrictive factors, though this particular factor was absent among the Finnish teachers. The Finnish teachers mentioned that the National Core Curriculum was a factor that provided a lot of space.

Fourthly, the reasons the teachers gave for exceeding or not exceeding professional space is a mixture of personal and professional reasons. The early years of the career (little experience and confidence) and local school leadership (degree of steering and control) are especially mentioned as key factors.

Finally, the most significant finding of this study is the role of the principal, which was a common factor in all three countries. The principal was mentioned in all the countries as playing both a positive and a negative role. The principal played a significant role in allowing freedom, in matters of trust and in providing a feeling or atmosphere in which the teachers were able to use professional space either to the maximum or even exceed it. The principal could also have a negative affect by being strict or controlling, and thus restricting or reducing the teachers’ use and sense of professional space. Trust was another common finding. Teachers who felt they were trusted either by the principal or by their school community felt they had a large amount of professional space. This study, like many before, shows how unconfident new teachers feel at the beginning of their careers. Such teachers need support, concrete advice as well as mentoring.

This study includes a limited sample that was selective and convenient, necessitating that teachers’ professional space be investigated with a much larger sample. The samples we collected from each country were from a socio-economically average or above average region. This is also a limiting factor and should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. In future studies, it is of the utmost importance that samples are collected from different socio-economic areas. The storyline method has its limitations, such as an inability to recall past experiences, events, or feelings. Modifying the storyline method assignment, for example by giving the task well in advance and giving teachers time to recall the past, could help. However, towards the end of this article we argue that our way of approaching teachers’ professional space and future provides a fruitful expansion of professional autonomy. We end this article with an argument for how our conceptualization of professional space may expand on earlier conceptualizations and units of analysis of teachers’ professional autonomy.

Like Wermke et al.’s (Citation2019) and Salokangas et al.’s (Citation2019) analysis of teacher-perceived autonomy, we find that teachers’ experience of professional space is a multidimensional phenomenon. Professional space captures various social domains that teachers operate within (in our case e.g., classroom, school, school district, national context). It also captures various loci or level of autonomy and control (in our case in relation to e.g., administration, local professional community, student-related work and the curriculum). However, we argue that by exploring professional space as we have conceptualized it, we capture more than teachers’ experience of external control over their decision-making capacity. We were able to grasp both external (political and top-down) and internal (professional and from-within) factors influencing professional work (cf. Mausethagen and Mølstad, Citation2015). However, in all three contexts, the internal factors were largely individual rather than rising from the professional community. Our empirical analysis also shows that control and managerial ideologies (cf. Frostenson, Citation2015; Salokangas et al., Citation2019; Wermke et al., Citation2019) only partly reflect the factors influencing teachers’ amount of say in their work. We found that the teachers also made distinctions between influential factors and near actors (local district, principal) and distant actors (e.g., state wise /national). It is clear that proximity on a daily basis surpasses even legal policy initiatives when it came to the teachers’ scope of action. Personal reasons and professional experiences over time turned out to be more influential across the three contexts despite the argument that the three contexts in earlier research have been defined as varying from little or no control (Finland) to, medium control (Norway) to heavily formal external control (US). The results in our empirical analysis showed that the time dimension has been absent in earlier studies and discussions on teachers’ autonomy. Mausethagen and Mølstad (Citation2015), Wermke et al. (Citation2019) and Salokangas et al. (Citation2019) have laid the groundwork for portraying professional autonomy as fixed, especially to a specific time, independent of the career trajectory of the teachers and contextual changes locally and statewide or nationally. Approaching professional space also allows one to explore changes over time including the past, the present and expectations for the future. Finally, professional space allows one to put the teacher at the center. The distinction between perceived versus utilized space allows the researcher to regard teachers as agents who create their own decision-making capacity rather than being mostly determined by external control mechanisms. Our findings indicate that teachers exploit and expand their professional space despite the increase in external control mechanisms and accountability initiatives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Afdal, H. W. (2019). The promises and limitations of international comparative research on teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 42(2), 258–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2019.1566316

- Amrein-Beardsley, A., & Holloway, J. (2019). Value-added models for teacher evaluation and accountability: Commonsense assumptions. Educational Policy, 33(3), 516–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904817719519

- Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2012). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary schools. Routledge.

- Beijaard, D., van Driel, J., & Verloop, N. (1999). Evaluation of story-line methodology in research on teachers' practical knowledge. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 25(1), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-491X(99)00009-7

- Biesta, G. (2010). Why ‘what works’ still won’t work: From evidence-based education to value-based education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 29(5), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-010-9191-x

- Buchanan, R. (2015). Teacher identity and agency in an era of accountability. Teachers and Teaching, 21(6), 700–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044329

- Cochran-Smith, M., Piazza, P., & Power, C. (2013). The politics of accountability: Assessing teacher education in the United States. The Educational Forum, 77(1), 6–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2013.739015

- Cribb, A., & Gewirtz, S. (2007). Unpacking autonomy and control in education: Some conceptual and normative groundwork for a comparative analysis. European Educational Research Journal, 6(3), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2007.6.3.203

- Dey, I. (1993). Qualitative data analysis: A user-friendly guide for social scientists. Routledge.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Erss, M. (2015). The politics of teacher autonomy in Estonia, Germany, and Finland [Doctoral dissertation]. Tallinn University. https://www.academia.edu/19924326/The_Politics_of_Teacher_Autonomy_in_Estonia_Germany_and_Finland_Tallinn_University_Dissertations_on_social_sciences_Tallinn_2015

- Frostenson, M. (2015). Three forms of professional autonomy: De-professionalisation of teachers in a new light. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 2015(2), 28464. https://doi.org/10.3402/nstep.v1.28464

- Gergen, K. J., & Gergen, M. M. (1986). Narrative form and the construction of psychological science. In T. R. Sarbin (Ed.), Narrative psychology: The storied nature of human conduct (pp. 22–44). Preager.

- Gergen, M. M. (1988). Narrative structures in social explanation. In C. Antaki (Ed.), Analysing social explanation (pp. 94–112). Sage.

- Goldhaber, D. (2015). Exploring the potential of value-added performance measures to affect the quality of the teacher workforce. Educational Researcher, 44(2), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X15574905

- Grossman, P., Loeb, S., Cohen, J., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). Measure for measure: The relationship between measures of instructional practice in middle school English language arts and teachers’ value-added scores. American Journal of Education, 119(3), 445–470. https://doi.org/10.1086/669901

- Hall, J. B. (2017). Examining school inspectors and education directors within the organisation of school inspection policy: Perceptions and views. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(1), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2015.1120234

- Ingersoll, R. M. (2009). Who controls teachers’ work? Power and accountability in America's schools. Harvard University Press.

- Jiang, J. Y., Sporte, S. E., & Luppescu, S. (2015). Teacher perspectives on evaluation reform. Chicago’s REACH students. Educational Researcher, 44(2), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X15575517

- Jyrhämä, R., & Maaranen, K. (2016). Ethos of equality: Finnish educational policy and practice. In H. Morgan & C. Barry (Eds.), The world leaders in education: Lessons from the successes and drawbacks of their methods (pp. 15–36). Peter Lang Publishing.

- Kupiainen, S., Hautamäki, J., & Karjalainen, T. (2009). The Finnish education system and Pisa. http://www.oxydiane.net/IMG/pdf_opm46.pdf

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (Vol. 142). Blackwell.

- Löfgren, H. (2015). Teachers’ work with documentation in preschool: Shaping a profession in the performing of professional identities. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(6), 638–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2014.965791

- Mausethagen, S. (2013a). Accountable for what and to whom? Changing representations and new legitimation discourses among teachers under increased external control. Journal of Educational Change, 14(4), 423–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-013-9212-y

- Mausethagen, S. (2013b). A research review of the impact of accountability policies on teachers’ workplace relations. Educational Research Review, 9, 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2012.12.001

- Mausethagen, S., & Mølstad, C. E. (2015). Shifts in curriculum control: Contesting ideas of teacher autonomy. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 1(2), 30–41.

- Mausethagen, S., Prøitz, T. S., & Skedsmo, G. (2020). Redefining public values: Data use and value dilemmas in education. Education Inquiry, https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2020.1733744

- Mehta, J. (2014). When professions shape politics: The case of accountability in K-12 and higher education. Educational Policy, 28(6), 881–915. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904813492380

- Niemi, H. (2015). Teacher professional development in Finland: Towards a more holistic approach. Psychology, Society & Education, 7(3), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.25115/psye.v7i3.519

- Oolbekkink-Marchand, H. W., Hadal, L. L., Smith, K., Helleve, I., & Ulvik, M. (2017). Teachers’ perceived professional space and their agency. Teaching and Teacher Education, 62, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.11.005

- Pettersson, D. (2014). Three narratives: National interpretations of PISA. Knowledge Cultures, 2(4), 172–172.

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G., Philippou, S., & Robinson, S. (2015). The teacher and the curriculum: Exploring teacher agency. In D. Wyse, L. Hayward, & J. Pandya (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of curriculum, pedagogy and Assessment (pp. 187–201). SAGE Publicatioons.

- Saari, A., Salmela, S., & Vilkkilä, J. (2014). Governing autonomy, subjectivity, freedom and knowledge in Finnish curriculum discourse. In W. F. Pinar (Ed.), International handbook of curriculum research (2nd ed., pp. 183–200). Taylor & Francis.

- Salokangas, M., & Ainscow, M. (2017). Inside the autonomous school: Making sense of a global educational trend. Routledge.

- Salokangas, M., Wermke, W., & Harvey, G. (2019). Teachers’ autonomy deconstructed: Irish and Finnish teachers’ perceptions of decision-making and control. European Educational Research Journal, https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904119868378

- Schatzki, T. R. (2010). The Timespace of Human activity: On performance, society, and history as indeterminate teleological events. Lexington Books.

- Simola, H. (2015). The Finnish education mystery: Historical and sociological essays on schooling in Finland. Routledge.

- Tirri, K. (2014). The last 40 years in Finnish teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 40(5), 600–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2014.956545

- Tveit, S. (2014). Educational assessment in Norway. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 21(2), 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2013.830079

- Wermke, W., & Forsberg, E. (2017). The changing nature of autonomy: Transformations of the late Swedish teaching profession. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(2), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2015.1119727

- Wermke, W., & Höstfält, G. (2014). Contextualizing teacher autonomy in time and space: A model for comparing various forms of governing the teaching profession. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(1), 58–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2013.812681

- Wermke, W., Rick, S., & Salokangas, M. (2019). Decision-making and control: Perceived autonomy of teachers in Germany and Sweden. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(3), 306–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1482960