?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article explores teaching practice concerning sexual harassment and abuse in Norwegian upper secondary schools based on phone interviews with 64 social studies teachers. This study portrays great variation in what extent teachers address these issues and discusses how this variation can be understood considering teachers’ personal characteristics, their interpretation of the curriculum, school culture-related factors and media coverage of sexual harassment and abuse. Young female teachers address such matters the most and younger teachers teach more about these issues than older teachers in general. The effect of age is stronger on women than men; the older the female teachers are, the less do they address sexual harassment and abuse. Male teachers have the same level of teaching regardless of age. Teachers’ characteristics appear to be equally influential as school culture-related factors.

Introduction

Sexuality education has gained attention in Norway and worldwide over the last decade (Hind, Citation2016; Røthing & Bang Svendsen, Citation2009; Støle-Nilsen, Citation2017; Stubberud et al., Citation2017; Goldschmidt-Gjerløw, Citation2019; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Citation2018). Research in the field of Norwegian sexuality education focuses on teachers’ understandings and perceptions of practice in either secondary school from 8th to 10th grade (Røthing & Bang Svendsen, Citation2009; Støle-Nilsen, Citation2017) or from 1st to 10th grade (Hind, Citation2016; Stubberud et al., Citation2017), whereas less research has been done in upper-secondary schools (Goldschmidt-Gjerløw, Citation2019). In 2008, Røthing & Bang Svendsen conducted a survey among 11 school leaders, 10 school nurses and 24 teachers in secondary schools in Mid-Norway (N = 45) (Røthing & Bang Svendsen, Citation2008, author’s translation). 21 respondents answered that they taught about sexual violence, 26 respondents replied that they address rape in class and 25 respondents answered that they taught about sexual harassment (Røthing & Bang Svendsen, 2008; p. 51). At that time, there was not an explicit goal related to these issues in the curriculum from 2006 for secondary and upper-secondary school [Kunnskapsløftet]. They pointed out that this was rather peculiar given the prevalence of sexual violence among Norwegian adolescents (Røthing & Bang Svendsen, Citation2009, p. 196). Since then, the curriculum was revised in 2013 and for the first time in Norwegian history, learning about sexual violence was made an explicit goal in secondary school; learners should now be able to ‘analyze gender roles in descriptions of sexuality and explain the difference between wanted sexual contact and sexual abuse’ (The National Directorate for Education and Training, SAF1-03, Citation2013, author’s translation) in social studies. In the mandatory social studies subject [samfunnsfag] in upper secondary school, sexual violence was included implicitly as students should learn to: ‘Analyze the extent of various forms of crime and abuse and discuss how such actions can be prevented, and how the rule of law works’ (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, SAF1-03, Citation2013, author’s translation). There appears to prevail a cultural taboo regarding teaching about sexual violence, especially when it targets children and adolescents. In my own study (Goldschmidt-Gjerløw, Citation2019), I have found that child sexual abuse and rape among young peers are the least addressed topics related to sexual violence in upper secondary school. Still, there is not enough knowledge regarding why some teachers bring these matters into upper secondary classrooms, whereas others do not or do so to a little extent. This article contributes to fill both this knowledge gap and a methodological gap, since no current studies have explored through regression analysis how both teachers’ personal characteristics and school culture-related factors such as cooperation between teachers and focus from the school management influence teaching about issues related to sexual harassment and abuse in social studies in Norwegian upper secondary schools.

Based on phone-interviews with 64 social studies teachers, this study discusses variation in teaching practice concerning sexual harassment and abuse in Norwegian upper secondary schools. The influence of curriculum content on teaching practice regarding sexual harassment and abuse will be discussed based on an analysis of the national curriculum in social studies (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, SAF1-03, Citation2013) and teachers’ interpretations of this curriculum in upper secondary school. The research question is: How can we understand the variation in teaching practice concerning sexual harassment and abuse based on social studies teachers’ personal characteristics, school-culture related factors, curriculum content and media coverage of sexual violence?

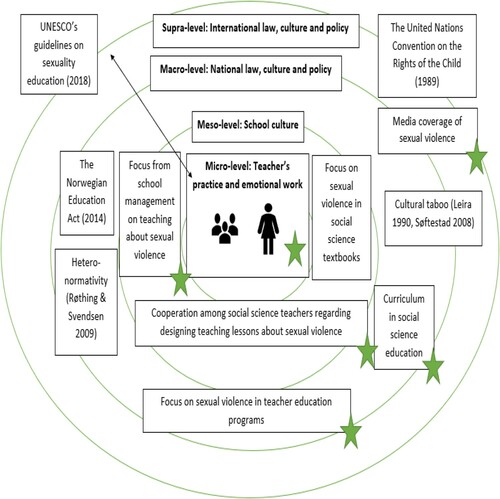

I have developed a theoretical figure based on the empirical content for this article, which is inspired by Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979). This figure visually illustrates the organization of teaching practice regarding sexuality education in Norway, including factors influencing practice on a micro, meso, macro and supralevel. Complementing this figure, I draw upon Bourdieu’s concepts of habitus, capital, field, doxa and reflexivity to provide lenses through which teachers’ personal characteristics and practices in class within the wider school field can be analyzed (Bourdieu, Citation1977, Citation1986, Citation1990, Citation1993; Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992; Swartz Citation1997).

Støle-Nilsen (Citation2017, pp. 18–20) identifies four different approaches to sexuality education in Norway; (1) the health approach, (2) the gender and diversity approach, (3) the crime approach and (4) the integrated approach, which combines the three preceding approaches. The purpose of the crime approach is to prevent criminal actions in relation to sexuality, such as sexual harassment and abuse, and the topics addressed include sexual boundaries, the legal framework, consent, abuse, rape, offenses and harassment (Støle-Nilsen, Citation2017, pp. 18–20). My own study could be thought to be situated within the crime approach, however, there are dimensions regarding sexual harassment and abuse that are linked to both health issues and gender and diversity matters. One example is to be found in Bendixen, Kennair and Daveronis’ study (Citation2018) among Norwegian adolescents; being exposed to verbal sexual harassment from young peers is associated with lower scores on indicators of well-being and unwanted sexual behavior negatively affects adolescents’ mental health; an effect that is stronger for girls than boys. Sexual harassment is closely linked to gender and diversity matters, as sexual harassment can be heterosexual harassment, harassment based on sexual orientation and/or harassment based on gender non-conformity (Meyer, Citation2009). Therefore, I do not situate my study within the crime approach to sexuality education, but rather encourage the readers to consider these issues through an integrated and holistic lense. The holistic perspective on sexuality education is also recently addressed internationally by the United Nations Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organization (UNESCO, Citation2018). This organization promotes comprehensive sexuality education, which is a:

Curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality. It aims to equip children and young people with knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that will empower them to: realize their health, well-being and dignity; develop respectful social and sexual relationships; consider how their choices affect their own well-being and that of others; and, understand and ensure the protection of their rights throughout their lives (UNESCO, Citation2018, p. 2016)

The right to education includes the right to sexual education, which is both a human right in itself and an indispensable means of realizing other human rights, such as the right to health, the right to information and sexual and reproductive rights. (United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to education, Citation2010, p. 7)

The need for addressing the cognitive, emotional, physical and social dimensions of sexual behavior through education has become urgent as recent Norwegian quantitative studies confirm high prevalence of sexual harassment and abuse among adolescents (Bakken, Citation2019; Bendixen et al., Citation2016; Mossige & Stefansen, Citation2016). The UngData-report confirms that 1 out of 4 girls in upper secondary school have been exposed to unwanted sexual touching against their will, which also applies to 10% of boys (Bakken, Citation2019, p. 3). Mossige and Stefansen’s study (Citation2016, p. 80) also portray gender differences regarding experiences with unwanted sexual acts; nine percent of girls has experienced being forced to unwanted sexual intercourse and this also applies to five percent of boys. Children who are sexually abused have a greater risk of becoming perpetrators themselves later in life (Glasser et al., Citation2001), and it takes on average 17.2 years before victims of child sexual abuse tell anyone about their experience (Steine et al., Citation2016). Studies indicate that education about body ownership, private parts of the body, distinguishing between types of touches, and who to tell could increase young learners’ capabilities of protecting himself or herself from abuse and increase the likelihood of reporting past or on-going abuses (Mikton & Butchart, Citation2009; Walsh et al., Citation2015), which could be considered an essential step towards countering the cycle of sexual violence.

This article applies the World Health Organization’s definition of sexual violence as:

Any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work. (World Health Organization, Citation2002, p. 149)

Approaches to Understanding the Organization of Norwegian Sexuality Education

illustrates the organization of Norwegian sexuality education based on the empirical content for this article, starting from micro-level with teachers’ practice in the classroom, to school culture-related factors at meso-level such as the level of cooperation among social studies teachers in regard to developing teaching lessons together on sexual harassment and abuse and focus from the school management regarding enabling teachers’ competence in this field. The macro-level includes national law, culture and policy documents for education, in which the national curriculum for social studies is of relevance for the discussion. The supra-level addresses law, culture and policy documents on an international level, such as UNESCO’s guidelines on sexuality education (Citation2018) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). Media coverage of sexual violence operates on both macro and supra level and is therefore situated “in between”. This figure is inspired by Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) and will now be discussed in light of Bourdieu’s conceptual framework of practice, fields, capital forms, doxa and reflexivity as a theoretical backdrop for discussing the empirical content.

Figure 1. Factors influencing teaching practice in the classroom. The stars indicate the analytical foci of this article. The model is based on empirical data collected by the author, 2018. It is inspired by Uri Bronfenbrenner (1979). First published in Goldschmidt-Gjerløw (Citation2019).

Bourdieu (Citation1990) presents habitus as one of the most central concepts in his social theory and it addresses among other aspects whether the individual is conscious of, or not, how the socio-cultural strata in which that person belongs, influence how he or she perceives and interacts in the social environment. Our actions and ways of being are not primarily based on reflection, but rather a pre-reflexive understanding of how we must act (Bourdieu, Citation1990). Teachers embody the social norms and conditions of their socio-cultural and historical context and are likely to a certain extent reproduce these norms through their teaching. It is of interest for this article to address the social norms concerning whether or not one could actually talk about sexual harassment and abuse. Social movements pushing for sexual liberation in the 1960s marked the beginning of increased openness concerning sexuality in the Western world (Tønnesen, Citation2018). However, the cultural taboo regarding sexual violence has prevailed up until recently. This taboo can be defined as a cultural phenomenon that entails a social prohibition on making visible or telling others about acts related to sexual violence (Leira, Citation1990), which does not necessarily operate at a conscious level and can become embodied in teachers’ habitus through an internalization of this social prohibition, because habitus develops according to the social sphere in which the person lives. Bourdieu terms this sphere the “field” (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992), which is a sphere of action that conditions those who act within it, according to their status within the field. The classroom can be seen as a field, situated within the wider field of the school. Teachers possess resources or what Bourdieu calls capital. He distinguishes between four forms of capital: economic, social, cultural and symbolic capital (Bourdieu, Citation1986). The empirical material for this article provides insight linked to cultural capital, and what I consider to be academic capital. Cultural capital can be seen as the aggregate of resources accumulated throughout one’s informal education, whereas academic capital is the aggregate of resources accumulated throughout one’s formal education. Through developing teaching lessons together with colleagues on issues related to sexual violence, teachers can increase their knowledge and insights into ways of teaching about these phenomena, which in turn could influence whether they address these matters in the classroom. The school management could also influence teachers’ resources, or cultural capital, through for example addressing teaching about sexual violence in staff meetings. Depending on teachers cultural and academic capital, each teacher possesses different sets of resources, which are likely to influence what they address, how and why in class.

Our habitus develops according to how our life conditions change, yet it does not change through mere reflection. Teachers are likely to develop ways of teaching which are in tune with their own habitus and changing this developed teaching practice is not impossible, but it would require social conditions for change. Conditions for change, rather than reproduction, are made when habitus meet structures radically different from those under which it was originally shaped (Swartz, Citation1997, p. 113). This can contribute to reflection over practice, which Bourdieu refers to as reflexivity. Reflexivity occurs from moments of mismatches between habitus and field which reveal the taken-for- granted assumptions of the “game” (Bourdieu, Citation1977). The condition for change of importance here is the #MeToo-movement, which altered the public discussion on sexual harassment and abuse from October in 2017 (Sayej, Citation2017). If this movement were to influence teaching practice in the sense that the topics of sexual harassment and abuse were included to a higher extent in class, we could perceive this as a changing doxa—altering the ‘taken for granted-assumptions’ of the implicit rules of teaching, which has implied not addressing these issues to any great extent.

Bourdieu is sometimes criticized for ending up in structural determinism, and it is not my intention to contend that teaching practice is structurally determined, but rather discuss that there are many factors influencing and to a certain extent, conditioning their practice. Still, as the empirical content will portray, teachers can also exert agency in the classroom, choosing which topics to emphasize in their teaching.

Methodological Overview

From February to October in 2018, in the midst of the #MeToo movement, I conducted a phone-survey with 64 social studies teachers from Norwegian upper-secondary schools regarding their teaching practice concerning sexual violence for the schoolyear 2017/2018. I applied a series of recruitment strategies; contacting former colleagues asking if they could put me in contact with eligible participants, publishing a request on the website for Norwegian social studies teachers on Facebook and sending emails to school leaders nationwide. The sampling was purposive, referring to how ‘researchers intentionally select (or recruit) participants who have experienced the central phenomena or key concept being explored in the study’ (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2019, p. 176). The reasons for recruiting purposively are linked to how the sample should have a particular profile; they had to teach or have taught the mandatory social studies subject in upper secondary schools during the last two years. It was also an aim that the gender representation coincided with the gender representation of teachers in Norway and that teachers from all age groups, multiple ethnicities and different study programs were included. As such, I purposively recruited to fulfill these criteria. This could be considered to be a potential drawback, thus, breaching the principle of random sampling (Mehmetoglu & Jacobsen, Citation2017, p. 221). I depended on gate-openers to have personal contact with eligible candidates to recruit informants, because they could motivate them to participate. This was important since teachers could be hesitant to talk about their practice regarding these issues. The response rate might have been very low without motivating gate-openers. Therefore, I opted for purposive sampling and the regression analysis is conducted as if the sample was random, which could be considered a limitation of method.

I used a structured survey with fixed response alternatives, while simultaneously inviting the participants to share their thoughts. I ‘ticked the boxes’ on the predetermined Likert-scale (discussed later) according to what the informants answered and took notes of their spontaneous reflections regarding the questions simultaneously on a physical copy of the survey. The quantitative material was transferred and analyzed in Stata, whereas the qualitative information was gathered in a notebook (Goldschmidt-Gjerløw, Citation2019).

There is a potential self-selection bias in the sample, because it could be that some of the informants taught more about these issues than those who declined to participate. A potential drawback with personal phone-contact with informants is the social desirability effect—the possibility that the individuals might reply what they think the interviewer would like to hear (Bertrand & Mullainathan, Citation2001). However, I did not notice that informants answered to “please me”, and I encourage them to answer as truthfully as possible.

To discuss representativity, the surveyed teachers’ characteristics are compared with key information from the national survey conducted by Statistics Norway among 16,400 teachers in upper secondary schools, in which 3157 are social studies teachers (Ekren et al., Citation2017). portrays the informants’ personal characteristics in my study:

Table 1. Overview of research participants regarding gender, age and educational level.

Table 2. Overview of index construction applied to measure the average degree of teaching about issues related to sexual violence.

Table 3. Description of the five independent variables—age, gender, education, educational relevance, cooperation and management, and the dependent variable average degree of teaching.

Table 4. Overview of results from the multivariate regression analysis.

Fifty-five percent of teachers in Norwegian upper secondary schools are women (Ekren et al., Citation2017, p. 19), which coincide well with the gender representation among the research participants in this study, in which 53% are women/47% are men. A gender-neutral alternative [hen] was included in the response alternatives, however, no informant identified with this option. The informants in this study are highly educated and over 73% of them holds a Master’s degree or Master’s degree with additional pedagogical studies (N = 47), whereas 27% do not (N = 17). When comparing to the educational level of the social studies teachers surveyed by Statistics Norway (N = 3157), 49.1% has a long higher education of 5 years or more (Ekren et al., Citation2017, p. 29). In sum, the characteristics of the participants coincide well regarding gender representation in the Statistics Norway report, however, they are younger and more educated than the national average.

Survey Design

The survey design was based on my experience as a teacher in upper secondary school over a period of six years. The questions related to what extent teachers address topics related to sexual harassment and abuse were in part inspired by research on sexual harassment and abuse in Norway (Bendixen et al., Citation2016; Mossige & Stefansen, Citation2016). I applied my knowledge of the national curriculum in social studies (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, SAF1-03, Citation2013) and content of the most widely used textbook, which made the survey culturally adapted to the Norwegian school context.

The survey consisted of 53 items (Goldschmidt-Gjerløw, Citation2019) and include questions about:

Personal information: age, gender, education, work experience.

Perceptions of their education’s relevance for teaching about sexual violence. The Likert scale was applied to measure perceptions (see an overview of this scale on the following page).

14 questions about to what extent certain topics related to sexual violence are covered through their teaching (see an overview on the following page).

Questions about to what extent the national curriculum covers these issues.

Questions about cooperation among the social studies teachers and focus on sexual violence from the school management.

Scale Construction and Scale Reliability

By combining the 14 questions about to what extent the teachers address different topics related to sexual violence, I made an index construction of their average degree of teaching (see the following page). The items were weighted equally. The Cronbach Alpha-test in Stata verified the reliability with a coefficient score of 0.89, showing very strong reliability and that removing one item would not make it stronger. The coefficient of 0.89 refer to how 89% of this index construction is reliable, and 11% of the variance is due to error (Mehmetoglu & Jacobsen, Citation2017).

Variables and Regression Model

This study has 64 observations and following the informal rule of having at least 10 observations per independent variable, the scope of this study was limited to a maximum of six independent variables. Including more variables could lead to overfitting the model, which refers to ‘asking too much from the available data’ (Babyak, Citation2004). The model to be estimated includes one dependent variable—teaching about sexual violence and six independent variables related to both teachers’ characteristics and school-culture related factors:

The main hypothesis was that there would be variation in teaching practice on sexual harassment and abuse, which is based both on my observations of teaching practice as a social studies teacher in three upper secondary schools from 2012 to 2018, and previous research (Røthing & Bang Svendsen, Citation2008; Støle-Nilsen, Citation2017). Another hypothesis was that female teachers address these issues the most, because girls and women are mostly affected by sexual violence and it could be that female teachers, to a greater extent than male teachers, try to influence young learners’ knowledge and attitudes regarding these matters through teaching.

The findings from this study are not generalizable to all teachers in Norway, but they portray correlations that are highly statistically significant for teachers’ practice concerning sexual violence in the mandatory social studies subject in upper secondary schools based on a highly reliable survey instrument.

Results

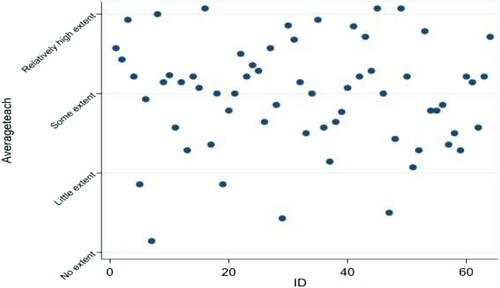

This scatter plot shows great variation in the extent to which the informants teach about sexual harassment and abuse, ranging from 0.14 (close to no extent) to 3.07 (relatively high extent) ():

Graph 1. Scatter plot of the variation in teaching practice based on each informant’s individual score measured by the index construction.

This finding coincides with the hypothesis that there would be variation, however, the variation is greater than expected. These teachers teach according to the same national curriculum in social studies (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, SAF1-03, Citation2013), yet, their teaching practice differs greatly. This illustrates how teachers are not ‘puppets on strings’; they exert agency in their teaching, although the curriculum conditions their teaching to a certain extent.

This regression analysis helps us see how both teachers’ personal characteristics and school culture-related factors are correlated with this variation in teaching practice:

Teachers’ Gender and Age

Female teachers tend to teach more about sexual harassment and abuse than their male colleagues. There are likely several reasons for this; women are most exposed to sexual violence and might feel a stronger need to counter such misbehavior through education than men do. Moreover, there was much public attention regarding the #MeToo-movement when these interviews were conducted, and this movement primarily shed light on young women’s experience with sexual harassment and abuse. Therefore, it might be that female teachers, and especially young female teachers, identify more with this movement than other teachers, and that this has influenced their teaching practice. When analyzing the mean average of teachers’ perceptions regarding the importance of addressing sexual harassment and abuse, female teachers express a higher level of importance than male teachers do, although male teachers also stress the importance of bringing these issues into the classroom.

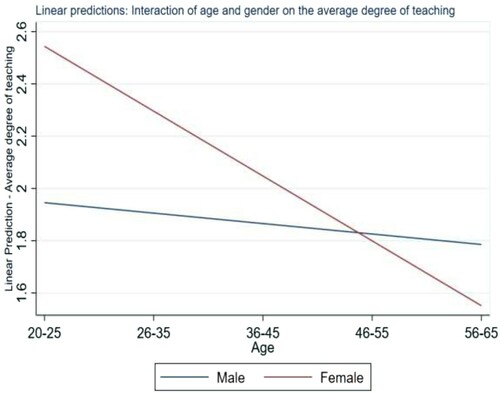

When examining possible interaction effects of age and being female on the average degree of teaching, age appears to have a stronger negative effect on female teachers than male teachers ():

Graph 2. Graphical representation of linear predictions of the interaction of age and gender on average degree of teaching about sexual harassment and abuse.

Comparing generations, the senior teachers could be more influenced by an embodied cultural taboo than later generations of young teachers due to changing social norms and public attention given to these sensitive issues. Today’s senior teachers grew up in an era with major societal changes. In school during the 1960s, the reproductive aspects of sexuality were prevalent (Røthing & Bang Svendsen, Citation2009, p. 81). By the 1970s, gender equality was established as an important ideal on a societal level and in the 1974-curriculum, there was an explicit gender equality focus (Røthing & Bang Svendsen, Citation2009, p. 82). However, issues related to sexual violence have not been included explicitly in the curriculum for secondary school until 2013, and still are implicit in the upper secondary curriculum (discussed later). It is likely that senior teachers have not been socialized into talking about sexual violence through their own schooling, which form part of the historical structures conditioning their habitus and practice in class, and that they to a certain extent reproduce these historical structures through their own practice. The historical doxa in school has been not to address these issues, which is also linked to the cultural taboo of sexual violence; senior teachers are likely to have embodied this taboo to a greater extent than the younger generations of teachers. This taboo does not necessarily operate at a conscious level as “the habitus—embodied history, internalized as a second nature and so forgotten as history—is the active presence of the whole past of which it is the product” (Bourdieu, Citation1990, p. 56). This finding contrasts previous research, as Støle-Nilsen (Citation2017, p. 122) did not find that age influenced teaching practice. This is probably due to how we have applied different methods and analysis; her study was based on qualitative interviews with 4 social studies and/or religion and ethics teachers, 4 natural science teachers and 4 school nurses (N = 12) (Støle-Nilsen, Citation2017, p. 56).

Teachers’ Educational Level and Educational Relevance

The analysis shows that an increase in teachers’ educational level is associated with a decrease in teaching about sexual violence. This finding might seem counterintuitive, but if we see this in relation to another empirical finding, it is logical; the teachers were asked to what extent they perceived their educational background to be relevant for teaching about sexuality and sexual violence, and 63%–66% responded to no degree or to a little degree. Støle-Nilsen (Citation2017:, p. 102) also finds that these issues are to a little extent part of teachers’ educational background in secondary school. Still, she did not find that this influenced teaching practice, whereas this study, on the contrary, finds that educational background and perceived relevance of education statistically influences teaching practice.

It is likely that when teachers specialize and hold a Master’s degree within a particular branch of social science, they might choose to emphasize topics they have key knowledge about in their teaching rather than sexual violence. If you go through five or six years at the university without learning about sexual violence through social science studies and/or pedagogical courses, this might not seem to be part of teaching social studies in upper-secondary schools. The analysis also implies that an increase in the perceived relevance of educational background is associated with an increase in teaching about sexual harassment and abuse. In other words, the more teachers have acquired of academic capital related to knowledge about sexual violence, the more do they address these issues in class. The participants were also asked to what extent they felt eligible regarding teaching about sexual violence based on knowledge they had accumulated throughout life regardless of their educational background. Fifty-two percent say they feel eligible to a relatively high or high extent, no one answered to no extent and 48% answered between little and some extent. As such, teachers feel they have more cultural capital, knowledge about sexual violence accumulated through informal education, rather than academic capital accumulated through formal education.

Influence of Cooperation on Teaching Practice

This study finds that there is little cooperation among social studies teachers on average in this field in Norwegian upper secondary schools. This might be linked to several factors; there might be little ‘fixed time’ for cooperation in schools, these topics are not heavily emphasized in the curriculum and therefore, they might cooperate on other topics. Given how these issues are to a little extent part of teachers’ educational background and academic capital, this might contribute to making them focus on other aspects of social studies.

The regression analysis shows that an increase in the level of cooperation is associated with a higher degree of teaching about sexual violence. Through cooperation, teachers can share knowledge and explore didactical opportunities, which could contribute to enhance their cultural capital in this field regardless of their gender, age, educational background and educational relevance. This point is made clear when looking into which teachers who had the minimum (0.14) and maximum teaching score (3.07); the minimum score is held by a middle-aged male teacher (36–45 years) and the maximum score is held by a senior male teacher (56–65 years). The latter contrasts the linear predictions drastically in the sense that his score is highly above average for males in that age group, whereas the first one is considerably below average. Both of these teachers answered that their educational background was to no or little extent relevant for teaching about sexual violence, but there were two factors distinguishing them from one another; whereas the teacher with the lowest average score reported that there were no cooperation among his colleague in this regard and no focus from the school management as for raising teachers’ competence, the senior male who had the maximum score reported that there were considerable cooperation at his school—they had made a #MeToo project for the students, and the school management had focus on enabling teachers’ competence on sexual violence.

School Management

This study shows that school managements nationwide have little focus on raising teachers’ competence regarding how to address sexual violence in general. On a more positive note, the analysis indicates that an increase in the level of school managements’ focus regarding enabling teachers’ competence is associated with an increase in teaching about sexual violence. When combining the two factors cooperation and school management, it becomes clear that school culture-related factors have an important influence on teaching practice. Some of the informants expressed that they would have appreciated more focus from the school management, and as one male teacher put it: ‘It would be great to learn more about this [how to teach about sexual violence] in the otherwise rather tedious staff meetings’. Støle-Nilsen (Citation2017:, p. 120) also found that several teachers in secondary school would like more focus from the school management in order to get more teachers ‘pulling in the same direction’. She affirms that ‘sexuality education could require more leadership than other issues given the topics’ nature and interdisciplinarity’ (Støle-Nilsen, Citation2017, p. 95, author’s translation).

Impact of #Metoo: Changing Doxa Influencing Teaching Practice?

The informants who taught about sexual harassment and sexual abuse during the schoolyear 2017/2018, said they did so partly due to the widely discussed #MeToo-movement in public media at that given time and the need for including current societal issues in class. This study finds that the changing doxa in public media coverage of sexual harassment and abuse has to a certain extent had an influence on teaching practice, contributing to making several of the informants include these matters in their own practice. However, the extent to which teachers report having included issues related to sexual violence in their teaching, such as the #MeToo-movement, depends on both teachers’ personal characteristics and school culture-related factors.

Changing Doxa in the Curriculum Renewal?

Coming back to the introduction, the United Nations considers that comprehensive sexuality is a ‘curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality’ (UNESCO, Citation2018). As previously introduced, there is one goal in the curriculum for the mandatory social studies subject [samfunnsfag] in Norwegian upper secondary schools that states that young students should learn to: ‘Analyze the extent of various forms of crime and abuse and discuss how such actions can be prevented, and how the rule of law works’ (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, SAF1-03, Citation2013, author’s translation). Yet, 73% of the surveyed informants express that the curriculum does not, or to a small extent, cover sexual abuse, which could be due to different interpretations of the Norwegian word for ‘abuse’ [overgrep] (Goldschmidt-Gjerløw, Citation2019, p. 16). Although this term can be used for physical or psychological abuse, it is most commonly used in referring to sexual abuse (www.overgrep.no, Citation2017). There is another more general goal concerning how the learner should ‘explore current local, national or global problems and discuss different solutions orally and in writing with an accurate use of relevant concepts’ (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, SAF1-03, Citation2013, author’s translation). This provides opportunities for the teachers to include current societal issues and opens up for agency regarding which topics to emphasize in teaching.

There is an aspect regarding evaluation in this subject that provides agency for teachers; there is no standardized exam and teachers themselves design the oral exam on the basis of the curriculum. Issues of sexual violence could therefore be included in this locally designed exam if teachers decide to do so.

In the new Norwegian curriculum for year 2020 and onwards in this subject—now called samfunnskunnskap, the learner should be able to ‘reflect over challenges regarding setting boundaries and discuss different values, norms and laws related to gender, sexuality and body’ (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, SAK01-01, Citation2019). Comparing this to the current goal, there are tendencies towards making the legal framework regarding boundaries somewhat more explicit and opening up for discussion concerning norms about gender and sexuality, but simultaneously, tendencies towards making sexual abuse more invisible, because the term abuse is no longer explicit.

The curriculum renewal also emphasizes three interdisciplinary themes (The Norwegian Government, Citation2016): (1) ‘Public health and life skills’, which includes matters such as interpersonal relations, sexuality, tolerance of diversity and life choices, (2) ‘democracy and citizenship’ and (3) ‘sustainable development’. Addressing sexual harassment and abuse could form part of these interdisciplinary themes, because being exposed to such misbehavior could affect both one’s psychological and physical health, it occurs in interpersonal relations and it assaults one’s sexuality. Sexual harassment and abuse is also linked to considerations regarding how one exerts citizenship; a person who sexually harasses another person, cannot be considered to be a democratic citizen, because the harasser would deprive the harassed person of his or her freedom privileges. Being reduced to gender or sexuality entails being deprived of the opportunity to be a citizen on equal terms as others in society (Cornell, Citation1995 in Sletteland & Helseth, Citation2018, p. 19, author’s translation).

Concluding Remarks

This study finds great variation in the extent to which Norwegian social studies teachers address issues related to sexual violence during the schoolyear 2017/2018. Young, female teachers are the ones who teach most about sexual harassment and abuse, and it is likely that they identify with the #MeToo-movement more than other teachers do, and that this influences teaching practice. It is not the intention of the author to ‘blame the male teachers’ for addressing sexual harassment and abuse less than female teachers; I rather encourage male teachers to talk to their students about sexual harassment and abuse, because both female and male teachers are essential role-models for young adolescents who are developing their sexual identities and understanding of how to engage in social and sexual relations with others.

The younger generations teach more about these issues than senior generations, which represents a generational shift. Senior generations of teachers could have embodied an historical cultural taboo through their own schooling and upbringing that they reproduce to a certain extent through their own practice. This does not mean that the senior generations of teachers represent ‘a lost cause’—as the anecdote about the senior male teacher in his sixties portray, if the school culture consists of widespread cooperation among teachers regarding developing teaching lessons on these topics and focus from the school management, this strengthens teachers' cultural capital and contributes to increased teaching. Through cooperation, teachers can contribute to each other’s reflexivity over practice and strengthen each other’s cultural capital by designing teaching lessons together, accompanying each other in class during the lessons and discussing the strengths and challenges of the designed lessons—in a ‘lesson study’—fashion. Providing comprehensive sexuality education would most likely require interdisciplinary cooperation with teachers from natural sciences, social studies, religion and ethics and language subjects. This way, teaching about these issues becomes a collective task and a shared responsibility in this field, which it should be—instead of an individual one.

This study finds that increased knowledge about sexual harassment and abuse through formal education has an impact on the extent to which these matters are addressed in class, and this finding should have political implications; The Norwegian state should allocate economic resources to teacher education institutions to provide both teacher students and current teachers professional development in this area. Taking part in professional development programs for teachers could provide conditions for change in their practice, because their habitus could meet structures that are radically different from those under which it was shaped, in Bourdieusian terms. Still, it is not sufficient to strengthen teachers’ academic capital through the teacher education and professional development programs for current teachers, because there is also need to increase school leaders’ academic capital through the leadership education.

The social studies teachers in upper secondary schools have the same national curriculum guiding their teaching, yet, teachers are not one homogenous group, they implement this curriculum differently and as the regression analysis portrays; both who teachers are matters and so does the school culture, for their teaching practice. In this regard, teachers exert agency through their teaching, because some choose to discuss sexual harassment and abuse in class regardless of the lack of an explicit focus in the curriculum. Exerting agency could here be considered to be a double-edged sword; on one hand, it is positive that some teachers address sexual harassment and abuse despite an ambiguous curriculum, but on the other hand, the opportunity to choose whether or not to include these matters in teaching, also contributes to many teachers’ silence on sexual violence. As such, there appears to be too much room for interpretation in this field. In the curriculum renewal in social studies for upper secondary school (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, SAK01-01, Citation2019), the issues of sexual harassment and abuse are still not mentioned explicitly. Therefore, it is likely that some teachers will continue to avoid these topics and there are reasons to critically question whether such issues will be thoroughly addressed in the aftermath of the #MeToo-movement.

A democratic society is more than a system of government consisting of abstract rules and processes; more importantly, it is a system of moral values and principles such as freedom, justice, equality and respect (Kelly, Citation1995 in Lim, Citation2015, p. 7). Regarding education, this means that we cannot only address the individual and institutional, such as knowledge about the political system, political parties and voting in elections, but more essentially, we have to address the individual and the relational—how we exert our citizenship, how we behave as human beings intrinsically influences other human beings lives. This takes us back to Kant—your freedom ends where the freedom of the other person begins. It is essential that young learners know that in order to protect both their own freedom privileges and those of others.

What teachers address in class can influence young learners’ lives—perhaps especially those who have experienced or are experiencing sexual violence without telling anyone, which makes addressing these issues a matter of ethics. If teachers are left to themselves whether to teach about sexual harassment and abuse, young learners are not provided with the sexuality education they should have according to both the UNESCO’s technical guidelines (UNESCO, Citation2018) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, Citation1989)—the latter being a legally binding document for Norway. What if key knowledge in mathematics and language subjects was taught in such differing ways? Leaving out knowledge about sexual harassment and abuse in education, or not addressing it thoroughly, could have major consequences both for young learners’ personal development and sexual boundaries, their relations to others and for society at large. The school system would be fostering citizens without in-depth knowledge on what constitute sexual harassment and abuse, which does not enable learners to protect their own freedom privileges and rights nor those of others. If education is to contribute to create a democratic society in which all citizens participate on equal terms regardless of their gender, silencing sexual harassment and abuse does no one any favors.

Acknowledgements

I am sincerely grateful for the contribution of each teacher who took part in this study. This article is written in solidarity with all of you. I would also like to express my gratitude to the editors, production team and anonymous reviewers at Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Babyak, M. (2004). What you see may not be what you get: A brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66, 411–421. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000127692.23278.a9

- Bakken, A. (2019). UngData 2019 – Nasjonale resultater [YoungData 2019 – National results] Norwegian Social Research, Oslo Metropolitan University. Retrieved November 26, 2019, from https://fagarkivet.oslomet.no/en/item/asset/dspace:15946/Ungdata-2019-Nettversjon.pdf

- Bendixen, M., Kennair, L., & Daveronis, J. (2018). The effects of non-physical peer sexual harassment on high school students’ psychological well-being in Norway: Consistent and stable findings across studies. International Journal of Public Health, 63(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-1049-3

- Bendixen, M., Kennair, L., & Viggo Grøntvedt, T. (2016). En oppdatert kunnskapsstatus om seksuell trakassering blant elever i ungdomsskolen og videregående opplæring [An updated knowledge report on sexual harassment among students in secondary and upper secondary education]. NTNU.

- Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2001). Do people mean what they say? Implications for subjective survey data. American Economic Review, 91(2), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.2.67

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1993). Structures, habitus, practices. In C. Lemert (Ed.), Social theory: The multicultural and classic readings (pp. 479–483). Westview Press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Polity Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

- Cornell, D. (1995). The imaginary domain: Abortion, pornography and sexual harassment. Routledge.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2019). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage.

- Ekren, R., Holgersen, H., & Steffensen, K. (2017). Kompetanseprofil for lærere i videregående skole [Profile of Teachers’ Competence in Upper-Secondary Schools] Statistics Norway. Retrieved November 11, 2019 from https://www.ssb.no/utdanning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/_attachment/352280?_ts=163d96c1810

- Glasser, M., Kolvin, I., Campbell, D., Glasser, A., Leitch, I., & Farrelly, S. (2001). Cycle of child sexual abuse: Links between being a victim and becoming a perpetrator. British Journal of Psychiatry, 179(6), 482–494. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.179.6.482

- Goldschmidt-Gjerløw, B. (2019). Children’s rights and teachers’ responsibilities: Reproducing or transforming the cultural taboo on child sexual abuse? Human Rights Education Review, 2(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.7577/hrer.3079

- Hind, R. (2016). Seksualundervisning i skolen – En undersøkelse blant kontaktlærere i grunnskolen [Sexual education in school – A survey among teachers in elementary school]. TNS Gallup, Sex & Samfunn [Sex & Society].

- Kelly, A. V. (1995). Education and democracy: Principles and practices. Paul Chapman.

- Leira, H. (1990). Fra tabuisert traume til anerkjennelse og erkjennelse. Del 1 Om arbeide med barn som har erfart vold i familien [From tabooed trauma to recognition and acknowledgement. Part 1 - On working with children who have experienced family violence]. Tidsskrift for Norsk Psykologiforening, 27(1), 16–22.

- Lim, L. (2015). Critical thinking, social education and the curriculum: Foregrounding a social and relational epistemology. The Curriculum Journal, 26(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2014.975733

- Mehmetoglu, M., & Jacobsen, T. G. (2017). Applied statistics using Stata – A guide for the social Sciences. SAGE.

- Meyer, E. (2009). Gender, harassment and bullying – Strategies to end homophobia and sexism in schools. Teachers College Press.

- Mikton, C., & Butchart, A. (2009). Child maltreatment prevention: A systematic review of reviews. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87(5), 353–361. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.08.057075

- Ministry of Education and Research. (2017). Overordnet del- verdier og prinsipper [General part- values and principles]. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/37f2f7e1850046a0a3f676fd45851384/overordnet-del—verdier-og-prinsipper-for-grunnopplaringen.pdf

- Mossige, S. & Stefansen, K. (2016). Vold og overgrep mot barn og unge – Omfang og utviklingstrekk fra 2007–2015. [Violence and child sexual abuse - Prevalence and Development from 2007-2015]. (NOVA-rapport 5/2016). Norwegian Social Research.

- Overgrep.no. (2017). Hva er forskjellen på overfall, overgrep og voldtekt? [What is the difference between assault, abuse and rape?] Retrieved May 14, 2020 from https://www.overgrep.no/hva-er-forskjellen-pa-overfall-overgrep-og-voldtekt/

- Røthing, Å., & Bang Svendsen, S. H. (2008). «Undervisning om seksualitet ved ungdomsskolene i Trondheim kommune». [Teaching about sexuality in secondary schools in Trondheim]. Trondheim kommune.

- Røthing, Å, & Bang Svendsen, S. H. (2009). Seksualitet i skolen. Perspektiver på undervisning [Sexuality in school – Perspectives on teaching]. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Sayej, N. (2017). Interview - Alyssa Milano on the #MeToo movement: ‘We’re not going to stand for it anymore’. The Guardian. Retrieved May 7, 2020 from https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2017/dec/01/alyssa-milano-mee-too-sexual-harassment-abuse

- Sletteland, A., & Helseth, H. (2018). Det jeg skulle ha sagt – Håndbok mot seksuell trakassering [What I should have said – Handbook against sexual harassment]. Forlaget Manifest.

- Steine, I. M., Winje, D., Nordhus, I. H., Milde, A. M., Bjorvatn, B., Grønli, J., & Pallesen, S. (2016). Langvarig taushet om seksuelle overgrep: Prediktorer og korrelater hos voksne som opplevde seksuelle overgrep som barn [Long term silence about sexual abuse: Predictors and correlates related to adults who experienced sexual abuse as children]. Tidsskrift for Norsk Psykologforening, 53(11), 889–899.

- Støle-Nilsen, M (2017). Seksuell danning – En studie av seksualundervisning i ungdomsskolen [Sexual ‘danning’ - A study of sexual education in secondary school]. University of Bergen. Retrieved October 16, 2019 from http://bora.uib.no/bitstream/handle/1956/16082/Seksuell-danning-AORG350-MSN.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Stubberud, E., Aarbakke, M. H., Bang Svensen, S. H., Johannessen, N., & Hammeren, G. R. (2017). Styrking av seksualitetsundervisning i skolen – En evalueringsrapport om bruken av undervisningsopplegget «Uke 6» [Strengthening sexuality education in school – En evaluation of the use of “week 6”], NTNU, KUN-report 2017:2. Retrieved October 28, 2019 from https://www.kun.no/uploads/7/2/2/3/72237499/stubberud_mfl_2018_-_styrking_av_seksualitetsundervisningen_i_skolen.pdf

- Swartz, D. (1997). Culture & power – The sociology of Pierre Bourdieu. University of Chicago Press.

- The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2013). Læreplan i samfunnsfag SAF1-03 [The curriculum for social science]. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://www.udir.no/kl06/SAF1-03/Hele/Kompetansemaal/kompetansemal-etter-vg1-vg2

- The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2019). Læreplan i samfunnskunnskap SAK01-01 [The curriculum for social science]. https://www.udir.no/lk20/sak01-01/kompetansemaal-og-vurdering/kv48

- The Norwegian Government. (2016). Meld.St. nr. 28 (2015-2016) Fag - fordypning - forståelse – En fornyelse av Kunnskapsløftet. [White paper number 28 Subject – specialization – understanding – A renewal of Kunnskapsløftet]. Retrieved May 6, 2020, from https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/e8e1f41732ca4a64b003fca213ae663b/no/pdfs/stm201520160028000dddpdfs.pdf

- Tønnesen, Ø. (2018). Seksualitetens historie [History of sexuality]. https://snl.no/seksualitetens_historie

- United Nations. (1989). United nations convention on the rights of the child. Retrieved January 6, 2021, from https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx

- United Nations Educational, Cultural & Scientific Organization. (2018). International technical guidance on sexuality education – An evidence-informed approach. ISBN 978-92-3-100259-5, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000260770

- United Nations General Assembly. (2010). Report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to education. https://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resource-attachments/UNSR_Sexual_Education_2010.pdf

- Walsh, K., Zwi, K., Woolfenden, S., & Shlonsky, A. (2015). School-based education programmes for the prevention of child sexual abuse. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004380.pub3

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2002). The world health report 2002: Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. Retrieved April 4, 2019, from https://www.who.int/whr/2002/en/whr02_en.pdf?ua=1