ABSTRACT

This study investigated which aspects of working with multilingual students bring joy to Finnish teachers. The data was collected via an online survey from teachers working mainly in basic education in Finland. The teachers (N = 588) reported a positive stance toward multilingual learners. The greatest number of responses (44%) cited students’ intrapersonal qualities, for example students’ motivation to learn and their academic, social, and emotional successes, as a source of joy. The positive impact of diversity on the school community (14%) and the teachers’ own development (12%) were the next most common sources of joy. Teachers with more experience working with multilingual learners were more likely to name students as a source of joy; similarly, teachers at schools with more multilingual learners were more likely to reference these students as a source of joy. The findings suggest that experience with many multilingual students promotes teachers’ commitment to them.

1. Introduction

Teaching can be a rewarding profession. However, teachers’ work is often portrayed as being filled with trouble, and the decline in the attraction towards teaching has become an international concern (Björk et al., Citation2019; Nieto, Citation2013). Teachers are seen as underpaid and undervalued, and the dropping numbers of students studying education is raising concerns, especially as many teachers are considering leaving the profession (Räsänen et al., Citation2020). However, opposing views about teaching also exist. Social media is full of stories wherein teachers report what wonderful students they have and how much they enjoy their work. Indeed, “Under conditions and in a context of respect and support, teaching is also tremendously rewarding” (Nieto, Citation2013, p. xiii).

One controversial narrative about teaching concerns the linguistic and cultural diversity of students, as increasing diversity is pushing societies in new directions and introducing new perspectives in classrooms. In Finland, this is reflected in the core curriculum for the country’s basic education (National Agency for Education, Citation2014); teachers are not only encouraged but required to consider the diverse identities and backgrounds of learners when designing lessons and methods. According to our experience as teacher educators, these guidelines are sometimes viewed as adding yet another element to the already demanding workload of teachers: however, many teachers consider their work more attractive specifically because of the diversity in their classrooms (Nieto, Citation2013). Our premise is that all teachers have opportunities to find joy in teaching students of diverse backgrounds, but the sources of such joy must be better understood and utilized. Moreover, enjoyment of one’s work also depends on resources and demands. Compared with many other contexts, the demands that teachers in Finland encounter are more balanced with the resources they are offered (e.g., high-quality teacher trainings and materials) (Kaukko & Wilkinson, Citation2018). However, according to our other studies, there are still issues that worry Finnish teachers, such as immigrant students’ Finnish language skills and limited educational opportunities (Alisaari et al., Citationmanuscript). This paper is inspired by the work of Sonia Nieto who has interviewed teachers in US who “thrive” and find teaching as “rewarding and even life-changing, for both teachers and students” (Nieto, Citation2013, p. xiii). According to Nieto’s interviews, the teachers who reported experiencing joy when working with students from diverse backgrounds noted that working with a diverse student population takes humility, a willingness to learn, acknowledgement of and appreciation for the tremendous assets of students of diverse backgrounds, and a commitment to public education (Nieto, Citation2013, p. xiv). In this study, we aim to investigate what are the sources of joy for Finnish teachers.

Teachers’ understanding of their praxis – the combination of their knowledge, skills, competencies, and actions – and how this is enabled or constrained in particular contexts (Kemmis et al., Citation2020; Olin et al., Citation2020) may influence how they consider the joys or the burden of their work. We have chosen to highlight some of the joys of teaching in linguistically and culturally diverse contexts. It is important to consider how the teaching profession is framed, as teachers’ resilience and coping abilities are influenced by the prevalent perceptions of their profession: “Taken together, social and school conditions and negative perceptions and expectations of students are a poisonous brew that gets in the way of the nation’s stated ideals of equal education” (Nieto, Citation2013, p. 13.) Highlighting the positive aspects of teaching could support teacher retention and positively influence students’ well-being (see also Nieto, Citation2013). Thus, this paper focuses on the positive aspects rather than the problems of teaching, which may help to remind educators why they enjoy their profession; it was important to uncover what brings teachers happiness in their work with multilingual learners.

In this paper, the term multilingual student/learner refers to students who (1) were born abroad or whose parents were born abroad; and (2) speak first languages other than language of instruction. This term was chosen to avoid a deficit view in referring to these students, though we acknowledge that Finnish-born students also often speak more than one language. Furthermore, while there is only one word in Finnish that means both multilingualism and plurilingualism (monikielisyys), we use the term multilingualism rather than plurilingualism (which is used in Francophone literature and European Union documents) to refer both to an individual’s ability to use two or more languages and to the existence of several languages in a society or a community (see also Aronin, Citation2019). In addition, we have chosen to use the term first language instead of home language (see e.g., Eisenchlas & Schalley, Citation2020) to refer to the language the immigrant students use with their families, as this term does not restrict the domain of the language to the speaker’s home, address the speaker’s proficiency in this language, or imply a language less valuable than the language of instruction; rather, it emphasizes the idea of the language that is the closest to a person’s identity (see also Alisaari et al., Citation2020; Seltzer, Citation2019). However, we use the terms with full awareness that none of them are neutral. The terms referring to the first languages of immigrant students is currently under discussion in Finland: kotikieli (home language) is not considered a neutral term, but ensikieli (first language) is considered a more neutral option (see Alisaari et al., Citation2020).

2. Linguistically and Culturally Responsive Praxis

Teaching is a constant reflection on and response to the needs and interests of learners, their communities, and society as a whole. Thus, it is essential that teachers make consistent moral, ethical, and practical judgments about which aims should be prioritized and how to best fulfill them. The navigation of this balance constitutes the praxis of teaching (Kemmis & Smith, Citation2008), the definitions of which draw on thinkers such as Freire (Citation2017), Habermas (Citation1963/Citation1973), hooks (Citation1994), and Kemmis and Smith (e.g., Kemmis & Smith, Citation2008). Most often, these definitions have roots in either neo-Aristotelian ideas of “morally committed, ethical action” or post-Marxist views of “history making action” (Kemmis & Smith, Citation2008, p. 4). Our understanding of educational praxis combines these two sets of ideals: Educational praxis is the intersection of teachers’ beliefs and practices, their way of “doing the right thing” in a “morally informed, committed way” (Kemmis & Smith, Citation2008, p. 4). In such actions, both the individual and societal consequences of teaching are considered, as each teaching encounter has short- and long-term impacts on individual learners and the society around them (Kemmis & Edwards-Groves, Citation2018).

In our work as teachers and researchers, we have seen teachers find joy in working to help individuals and humankind as a whole. In addition, Nilsson et al. (Citation2015) found that caring, which occurs when being present and promoting the well-being of oneself and others, is central to teachers’ well-being. Thus, the act of caring can be seen as a source of joy as well. However, while teachers’ own well-being can be fostered through success with pedagogical or social goals, negative experiences may lead to feelings of failure, or even burnout (Soini et al., Citation2010). Similarly, while alignment between one’s personal values and those of their employer promotes job satisfaction (Chatman, Citation1991; Verplanken, Citation2004), a society’s notion of what is “good” is dependent on context, including the time and place in history (Kemmis & Edwards-Groves, Citation2018, p. 7). When working with culturally and linguistically diverse groups of students, questions surrounding the notion of “good” might be even more complex (Kaukko & Wilkinson, Citation2018; Kaukko & Wilkinson, Citation2020), and reflecting on what is best for the students may require additional effort from teachers. However, we argue that the increasing cultural and linguistic diversity in school communities and the additional practices these entail may bring unique joys to teaching.

Rather than the more technical notion of pedagogy as the art and craft of teaching or the narrower definition of pedagogy as subject-specific methods of instruction, the idea of teaching as praxis (Kemmis & Smith, Citation2008; Olin et al., Citation2020) builds on the notion of pedagogy as a holistic task that focuses on the “upbringing” of the learner as a whole. This concept is also the basis of linguistically and culturally responsive teaching, which recognizes that every student contributes valuable assets to the class (Ladson-Billings, Citation1995; Lucas & Villegas, Citation2013). Culturally responsive teaching empowers students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically (Ladson-Billings, Citation1994) by legitimizing students’ cultural knowledge and prior experiences (Gay, Citation2000). Students’ backgrounds and knowledge are valued and seen as assets for learning, which helps teachers see beyond stereotypes and build on the students’ “funds of knowledge” (Moll et al., Citation1992). Linguistically responsive teaching, on the other hand, builds on the premise that students’ funds of knowledge include language, culture, and identity (Lucas & Villegas, Citation2013). Thus, valuing linguistic and cultural diversity and advocating for multilingual students’ language learning becomes part of teachers’ linguistically and culturally responsive praxis (Lucas & Villegas, Citation2011, Citation2013). It is important to create classroom settings where all students are considered valuable and feel a sense of belonging. Indeed, in line with Valdiviezo and Nieto (Citation2017), we argue that this kind of classroom should be every child’s right.

Schools are not only sites for learning but also for identity development, so it is crucial to affirm students’ identities and develop them in the school context (Paris, Citation2012). When teachers experience joy while working with multilingual learners, the students feel more valued (Nieto, Citation2013). However, in educational contexts, cultural and linguistic diversity is frequently seen as a deficit (Kaukko & Wilkinson, Citation2018; Skutnabb-Kangas, Citation2017). In contexts where a student’s first language is not the language of instruction, it can be hard to avoid sending unintentional messages regarding the values of different languages (Lo Bianco, Citation2010). Moreover, teaching practices that focus exclusively on the language and culture of the school might unintentionally overlook diversity (Cummins, Citation2001). Reflecting on these dimensions is a part of the additional efforts required of teachers who work with cultural and linguistic diversity.

There is a strong body of literature suggesting that teachers’ work satisfaction (i.e., their success in pedagogical and social goals) is related to their well-being (Soini et al., Citation2010). Moreover, teachers’ well-being promotes higher-quality teaching, thereby supporting a better education for students. To reveal the positive aspects of linguistically and culturally diverse education, we need to better understand what brings teachers joy in their work. Previous research has suggested that teachers’ development and possibilities to realize themselves through teaching significantly increase their engagement with their work and enhance their ability to perceive it as significant (Hakanen et al., Citation2006; Martela & Pessi, Citation2018). Furthermore, enjoyment of teaching (Hargreaves, Citation2000) and pedagogical well-being can increase through positive interactions between teachers and students (Runhaar et al., Citation2013; Soini et al., Citation2010), and possibilities for self-improvement and heightened self-efficacy may increase teachers’ professional resilience (Aho, Citation2010; Bermejo-Toro et al., Citation2016). However, there is a gap in the research exploring the joys of teaching in a multilingual context. In this article, we seek to fill this gap by examining what brings teachers joy while working in culturally and linguistically diverse settings. Our results will be beneficial for helping the discussion around linguistically and culturally diverse education shift to a more positive direction.

In conducting this study, our aim was to investigate what factors give Finnish teachers joy when they work with multilingual students who speak first languages other than Finnish, Swedish or Sami, the official languages of Finland. We do this by answering the following research questions:

RQ1: What brings teachers joy in teaching multilingual learners in Finland?

RQ2: How are teachers’ background factors linked to their reported experiences of joy?

3. Methodology

In this section, we introduce the methodology used in this study. First, we present the instruments used for data collection; second, we present the participants of the study; and third, we explain the data and analysis of the study.

3.1. Instrument

The data for this study was collected via an online survey in the spring of 2016. The survey was an adaptation of an unpublished preliminary survey by Milbourn, Viesca, and Leech (later presented at a conference in 2017) that focused on linguistically and culturally responsive teaching. The original survey was created according to the framework of linguistically responsive teaching developed by Lucas and Villegas (Citation2013). The Finnish adaptation and translation were done by Alisaari and her colleague Emmanuel O. Acquah. In the adapted version of the survey, there were 59 Likert scale (1–5) statements investigating teachers’ linguistically and culturally responsive pedagogy and their beliefs related thereto and 11 open-ended questions. The original survey was more extensive: 150 Likert scale statements and 16 open-ended questions. Five open-ended questions outside of the original survey were added to the adapted version, as these were considered important for gaining a deeper understanding of teachers’ beliefs and practices related to linguistically and culturally diverse students. One of the added questions was about the joys teachers experience when teaching multilingual students. The adapted version of the survey was then reviewed by experts at the Finnish National Agency for Education, the Finnish Network for Language Education Policies, and the Centre of Applied Language Studies. The final version of the survey was created based on these experts’ comments and in cooperation with a statistician to ensure reliability and validity of the instrument. The reliability of the survey’s Likert scale statements was found to be high by calculating Cronbach’s alphas (0.73–0.75).

The online survey was advertised in January 2016 on various fora: email lists, social media, the websites of Opettaja (the journal of the Finnish teachers’ union) and the Association of the Finnish as a Second Language Teachers, and at the Educa Educational Fair. A link to the survey was also sent to all local education departments in Finland with a cover letter in Finnish or Swedish, asking them to send it to all the teachers in their area. The aim was to reach as many Finnish basic education teachers as possible, but since it is unknown how many people received or saw the survey link, the actual participation percentage cannot be calculated. The cover letter included information about the aim of the study (to understand Finnish teachers’ beliefs and practices concerning teaching multilingual learners), data protection, and consent to participate the study. Participants gave their informed consent by completing the survey. In this paper, we focus on one of the open-ended questions (stated below) and the demographic and background information of the participants.

3.2. Participants

Altogether, 820 teachers completed the survey (78% female, 21% male, 1% other). The mean age of the participants was 41. The genders and ages of respondents were fairly representative of the larger Finnish teacher population (Kumpulainen, Citation2017), but the participants were self-selected by choosing to complete the study. The respondents worked in a variety of areas: 23.1% were primary school teachers, 44.3% were subject teachers in secondary or upper-secondary school, 4% were primary school teachers with additional qualification as a subject teacher, 14.9% were special education teachers or teachers of newly arrived immigrants, 2.9% were school counselors, 5.7% were principals, and 3.6% were others, mainly substitute teachers. The subject teachers represented different subjects, including Finnish as a first language and literature, Finnish as a second language and literature, English, German, Swedish, French, mathematics, physics, chemistry, Information and Communications Technology, and healthcare sciences. We chose to include principals and counselors in the study because these groups also have teaching responsibilities within the structure of Finnish basic education; as such, their experiences of joy are also important to investigate.

3.3. Data and Analysis

The data for this analysis consisted of 588 teachers’ responses to one optional open-ended question: “Mitkä kolme asiaa ilahduttavat sinua työskentelyssä suomea toisena kielenä puhuvien oppilaiden kanssa?” (“What three things give you joy in teaching students who speak Finnish as a second language?”) The number of teachers who responded to this question was similar to the number of teachers who responded to the other open-ended questions in the survey (Alisaari et al., Citation2019). All of the responses were in Finnish or Swedish, and all of the authors of this paper are speakers of these languages. The coding was done in Finnish. The data was analyzed using content analysis (see, e.g., Krippendorf, Citation1980).

All of the authors read the first 100 responses to gain an understanding of the data. Based on the initial analysis, the first author suggested six main categories for a more detailed content analysis. We agreed on the six categories and analyzed the first 100 teachers’ responses to the open-ended question based thereon. After the initial analysis, we discussed the categorizations, added subcategories, and further defined them (see the final categories in ). The first 100 teachers’ responses were then reanalyzed by all of us, and inter-rater reliability was calculated. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.97 for the main categories and 0.9–1.0 for the subcategories.

Table 1. Sources of joy main categories and subcategories with sample responses.

After the preliminary calibration of the analysis, the first two authors continued analyzing the remaining responses. When this was done, items marked as difficult to categorize were discussed among the three of us. Finally, the inter-rater reliability for the analysis of all the responses by the first two authors was calculated again. The ICC for the two authors was 0.97 for the main categories and 0.81–1.0 for the subcategories. Since the correlation between the two raters was very good overall, it was decided that the first author’s categorizations would be used in the subsequent statistical analysis. Of the teachers who responded to the question, 8% reported having no experience with multilingual students, and another 18% did not provide this information; those who did not answer the question under investigation were excluded from the analysis. In addition, although the teachers were asked to provide three aspects of joy, many listed fewer; the missing answers are reported as such.

After the data was categorized, we examined it using descriptive statistics. First, we investigated the response frequencies in different categories. Second, we used crosstabs to investigate whether the teachers’ backgrounds were linked to their responses. We considered the teachers’ positions (primary school/secondary school/special education; teachers/principals/counselors), teaching experience (in years), experience teaching multilingual students (in years), and the percentage of multilingual students at their schools as background factors. No statistical testing was used to investigate possible links between the teachers’ backgrounds and their responses, as the significant differences in the sizes of the main and subcategories made it impossible to use chi-square and z-test statistics. The frequencies and crosstabs were investigated via the multiple response set function in SPSS, as the responses to the open-ended question under investigation consisted of three separate responses. IBM SPSS Statistics 25 was used for all statistical analysis reported in the study.

4. Results

In this section, we present the frequencies of teachers’ responses, then we examine how teachers’ different background factors were linked to their reported sources of joy.

4.1. What Brings Teachers Joy?

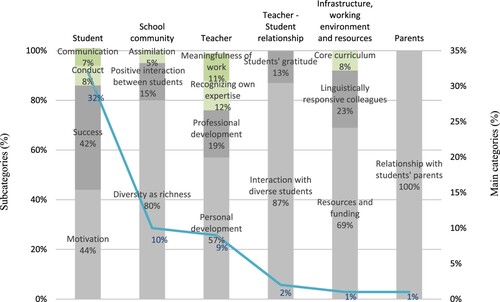

First, we investigated the frequencies of the teachers’ categorized answers. The responses were divided into the six main categories presented in . The greatest number of responses (44%) cited students’ intrapersonal qualities as a source of joy. The positive impact of diversity on the school community (14%) and the teachers’ own development (12%) were the next most common sources of joy. The main categories of the teachers’ answers are presented in .

Figure 1. The distribution of teachers’ responses within the main categoriesa.

Note: aThe percentages on the left hand side present the percentages of subcategories. Note that the n for 100% in each subcategory is different. The different colors in the columns show the distribution of the responses in subcategories. The percentages on the right present the main categories, which is marked with the blue line.

Next, we examined the frequencies of the teachers’ responses within the subcategories (). The category Relationship with students’ parents was not examined separately, as there were no subcategories of this main category.

Within the main category of Students’ intrapersonal qualities (44% of all responses), the teachers cited their multilingual students’ motivation (44% of responses within this category) and academic, emotional, or social successes (42%) as the main sources of joy in their teaching. Less frequently, students’ conduct in the classroom (8%) and their open communication (7%) were mentioned.

The Students in the school community category was the second-largest (14% of all responses), wherein most of the teachers (80%) described the students’ multitudinous languages and cultures as a “richness.” Teachers also found joy in positive interactions between students (15%) and helping “assimilate” their multilingual students into Finnish society (5%).

Aspects related to Teacher's own development comprised the third-largest category (12% of all responses). Teachers mentioned the opportunity to develop personally (57%) or professionally (19%) as sources of joy. Teaching multilingual students helped some teachers recognize their own expertise (11.9%) and made their work feel more meaningful (12%).

The category Teacher-student relationship (2% of all responses) included interaction with multilingual students (86.8%) and students’ gratefulness to the teacher (13.2%) as sources of joy. In the category Infrastructure, teachers’ working environment, and resources (1% of all responses), the teachers cited resources and funding (69.2%) or core curricula (7.7%) as sources of joy in their work. Colleagues, who were often mentioned as being linguistically responsive, were also reported (23.1%) as bringing joy.

4.2. Teaching Experience and Teachers’ Reported Sources of Joy

Next, we investigated whether the teachers’ background factors were linked to what brings them joy in teaching multilingual students. The background factors examined were teaching fields, teaching experience, experience teaching multilingual students, and the percentage of multilingual students at the teachers’ schools. We focused on possible differences between teacher groups by looking at the results of the main categories of the teachers’ answers, reported no experience and missing answers. Due to the great variance in the number of responses in the subcategories, only the main categories of responses were investigated.

First, we looked at the teachers’ teaching fields (see ). As stated previously, most of the teachers and over half of the principals and counselors indicated the students were the main source of joy in their work, and approximately 40% of the other groups saw the students as a source of joy. The category Students in the school community was reported as a source of joy for 10–20% of each group, with the exception of principals (8%). The principals were also the most likely to report “no experience” with working with multilingual learners (18%), compared to between 2% and 9% of the teacher groups. This may be explained by the leadership position of the principals and the possible interpretation of “experience” as referring specifically to teaching. The principals answered the question about sources of joy more diligently than the other teacher groups, with all but 6% of the principles giving the required three answers; 13–20% of the other groups listed only one or two sources of joy.

Table 2. The frequencies of the main categories based on teachers’ responses, reported “no experience” and missing answers across different background factors.

Second, we compared response frequencies with participants’ teaching experience. The teachers were divided into six groups of teaching experience: less than 1 year; 1–2 years; 2–5 years; 5–10 years; 10–20 years; and 20+ years. Longer teaching experience equated to higher reports of Students’ intrapersonal qualities as a source of joy: 56% of teachers with 1–2 years of experience reported Students’ intrapersonal qualities as a source of joy, compared to 35% of teachers with 2–5 years of experience and some 45% of the other experience groups. Teaching experience was also indicative of teachers’ own development being a source of joy; teachers with 1–2 and 10–20 years of experience rarely (7–9%) named their own development as a source of joy, while 20% of teachers with less than 1 year or 2–5 years of experience reported their development as a source of joy, and 12–13% of the other groups named their development as a source of joy. In addition, teachers with less than 1 year of experience reported Students in the school community as a source for joy less often (9%) than the other groups (13–15%). This group (less than 1 year) was also more diligent in giving all three answers (12% missing) compared to those with more experience (17–22% missing).

Third, the relationship between teachers’ experience teaching multilingual students and their responses was investigated. Here, there was a clear tendency of those with more experience teaching multilingual students naming Students’ intrapersonal qualities as a source of joy: 56% teachers with more than 20 years of experience teaching multilingual students named Students’ intrapersonal qualities as the source of joy, compared to 40–49% of teachers with between 1–20 years’ experience. Teachers who had no experience teaching multilingual students reported Students’ intrapersonal qualities as a source of joy in 22% of their responses; this group also mentioned Teachers’ own development as a source of joy less often (8%) than teachers with more experience (13–16%), although it should be mentioned that less than 10% of teachers with 5–10 years of experience reported Teachers’ own development as a source of joy.

4.3. Reported Joy and the Composition of Schools’ Student Cohorts

Finally, we studied the relation between the teachers’ responses and the percentage of multilingual students at their schools, finding that more multilingual students at a school equated to more frequent mention of Students’ intrapersonal qualities as a source of joy. Teachers whose schools had a 40–60% population of multilingual students reported Students’ intrapersonal qualities as a source of joy in over 70% of their responses, compared to 44–51% in teacher groups whose schools had a multilingual student population of 1–40% or over 80%; teachers working in schools with fewer than 1% multilingual students reported Students’ intrapersonal qualities as a source of joy in only 35% of their responses. Surprisingly, teachers whose schools had a multilingual student population of more than 80% never reported professional or personal development as a source of joy, which the other groups indicated in 6–17% of responses.

The teachers whose schools had a multilingual student population of 30–40% placed more emphasis on Relationship between the teacher and the student as a source of joy (11%) compared to the other groups (0–4%). Interestingly, the teachers at schools with a multilingual student population of 60–80% reported the students’ parents as a source of joy (7%) more often than the other groups (0–3%). Teachers in schools with the fewest (20% or less) and the most (over 80%) multilingual students were less diligent in answering the question: 17–21% had missing answers among these groups, compared to teachers at schools with 20–80% multilingual students (0–9% missing answers).

5. Discussion

Our aim in conducting this study was to investigate how teachers experienced joy when working with multilingual learners and discover what background factors were linked to these reported sources of joy. The topic most frequently mentioned as a joy of teaching was the students themselves, especially in relation to their intrapersonal qualities. Many teachers were delighted by their students’ motivation to learn and their academic, social, and emotional successes. Furthermore, students’ positive interactions with one another and the relationships between teachers and students incited joy, which aligns with previous studies (Hargreaves, Citation2000). A diverse student community and positive interactions between students were other aspects that gave the teachers joy. Cultural and linguistic diversity were seen by participants as valuable resources, which reflects the ideals behind the national core curriculum for basic education in Finland, wherein diversity is emphasized to ensure equal opportunities for all students. When teachers’ attitudes reflect this, the aims of the curriculum are much more likely to be fulfilled. Teachers’ responses regarding the joy brought by diverse school communities, the students themselves, and positive relations with students align with the aims of culturally responsive pedagogy.

Previous research has shown that culturally responsive pedagogy empowers students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically (Ladson-Billings, Citation1994) by legitimizing students’ cultural knowledge and prior experiences (Gay, Citation2000). Furthermore, according to previous research, positive interactions between teachers and students increase teachers’ pedagogical well-being (Runhaar et al., Citation2013; Soini et al., Citation2010). When teachers perceive their work with students as enjoyable, alignment between teachers’ values and their work is more likely. This can enhance their job satisfaction (see Chatman, Citation1991; Verplanken, Citation2004) and prevent them from leaving the profession (Heikonen, Citation2020).

In this study, the principals rarely reported the students in the school community bringing them joy. Principals are responsible for schools’ operating cultures, and their positive influence on linguistic and cultural praxis is essential (Kaukko & Wilkinson, Citation2018); according to Nieto (Citation2013), context, including a school’s emotional environment and material resources, influences teachers’ engagement with their work. Therefore, because school leadership plays a key role in enabling or constraining the ways teachers can enact linguistically and culturally responsive teaching, it is critical to convince principals of the importance of a diverse community as a resource for teachers and the students alike.

The students’ backgrounds and previous knowledge were valued as assets for the students and for the teachers’ own professional development. The participants discussed how their students promoted their own development and the importance of building on the skills and knowledge the students brought to the classroom, which aligns with previous findings (Nieto, Citation2013). This perspective goes beyond the deficit-focused stereotypes about multilingual learners. Although the teachers were not explicitly asked about affirming students’ identities, their responses could indicate that they viewed this as important. Students being recognized as valuable and a source of joy for their teachers affirms their identities, which in turn fosters the students’ well-being and academic success (Cummins, Citation2001; Paris, Citation2012). Indeed, teaching as praxis builds on the notions of affirming and developing the whole learner (Kemmis & Smith, Citation2008) and all participants engaging and learning in educational encounters. The teachers also reported on their role of connecting with students’ backgrounds (see also Moll et al., Citation1992; Nieto, Citation2013). This aligns with the principles of a culturally and linguistically responsive praxis leading to positive outcomes for both the individual learner and the increasingly diverse societies within and beyond school contexts (Valdiviezo & Nieto, Citation2017).

Teachers saw working with multilingual students as a source of personal or professional development and a source of joy. This is in line with previous research, indicating that teachers consider their work far more significant when they experience continuous personal or professional development and possibilities to realize themselves through meaningful work (Hakanen et al., Citation2006; Martela & Pessi, Citation2018; Nieto, Citation2013). This result also highlights the ethical dimension of teaching and the different ideals that underlie teachers’ work. The idea of teaching as praxis, that is, as consisting of ethically and morally committed work, provided a lens through which to interpret these dimensions; this study shows how aspects that are often viewed as challenges (most notably, the increasing cultural and linguistic diversity in classrooms) can in fact bring joy to teaching. Teaching is “not just a job, not even just a profession, teaching is a professional and emotional work, sometimes life-changing and life-saving and always consequential” (Nieto, Citation2013, p. 149). Working with multilingual groups may demand more from teachers, but such work encourages them to develop their own praxis and consequently grow as professionals. This praxis development, consisting of reflecting on the practical, moral, and ethical choices of one’s profession, was seen as a joy in the teachers’ work, and we argue that this joy should be better understood and facilitated in schools. Furthermore, a more thorough foundation for working ethically and effectively with diversity requires both pre- and in-service teacher education. In Finland, reflections on the practical dimensions of teaching are strongly present in pre-service teacher education, but they often do not emphasize diversity, and the ethical and moral dimensions could benefit from more prominence.

Some teachers mentioned their students’ gratefulness as a source of joy. Positive feedback from students can be linked to positive feelings, and gratitude positively impacts both teachers and classroom environments (Howells, Citation2014). However, there is also another perspective of gratitude: The “grid of immigration” (Back, Citation2003, p. 351) can cause immigrants to experience a burden of gratitude toward their host countries. They feel obliged to be thankful and contribute to the countries that have welcomed them, which can manifest as exaggerated politeness toward authorities, including teachers. The mention of students’ gratitude might be teachers’ genuine experiences of the feeling; however, more knowledge of working with immigrant students and a more critical stance toward their own work could change this experience.

Similarly problematic was mention of students’ “assimilation”, which implies partial identity loss instead of a two-way integration in which both society and individuals adapt. Some responses indicated an aim for a homogenous group or society and a hope that “assimilation” would make their students’ school lives easier. However, as the teachers mentioned this as a joy of teaching, it is possible that the intention was good.

The similar responses from groups of teachers with similar backgrounds was striking: Teachers with more experience working with multilingual learners were more likely to mention students as a source of joy, whereas this was less likely with teachers who had little or no experience. Nieto (Citation2013) has suggested that it is essential that teachers thrive, rather than survive, in their work; every student deserves a teacher who is energized and passionate, and this further influences the development of society as a whole. Our results are in line with previous research that found that teachers put more effort into survival earlier in their careers (Lindqvist et al., Citation2014), whereas through professional development and work experience, teachers learn to thrive and find joy, becoming able to positively impact students accordingly (Heikonen, Citation2020; Thomas & Beauchamp, Citation2011). This is in line with research (Alisaari et al., Citation2019) showing that experience in teaching multilingual learners leads to the most supportive beliefs about multilingualism. Furthermore, experienced teachers are able to see their own development as a positive resource more than teachers with less experience. Newly graduated teachers might struggle more with daily routines, which can reduce the attractiveness of their work (Thomas & Beauchamp, Citation2011) or lead to burnout (Soini et al., Citation2010) or leaving the profession (Heikonen, Citation2020). In contrast, opportunities for self-development through teaching can increase their engagement and resilience in their profession (Aho, Citation2010; Bermejo-Toro et al., Citation2016; Hakanen et al., Citation2006; Heikonen, Citation2020; Martela & Pessi, Citation2018).

In addition, the larger a school’s population of multilingual students, the more likely the teachers were to mention the students as a source of joy. Therefore, it can be inferred that experience with many multilingual students promotes teachers’ commitment to their students. This finding presents a compelling case for having future teachers practice at schools where there are many multilingual students: Novelty is often perceived as dangerous, but the more teachers work with multilingual students, the more feelings of fear or insecurity subside, and the more they can enjoy their work. Shifting the discourse on linguistic and cultural diversity to be more positive also has societal relevance beyond the school context, as such a shift would promote a more affirming stance toward linguistic and cultural diversity.

The biggest limitation of this study is that the participants were self-selected. Teachers who considered the survey topic interesting may have been more likely to participate, thus the results might not be generalizable nationally or internationally. However, as the number of responses was relatively high, the findings arguably provide a good understanding of the joys teachers find in their work. In addition, when investigating the possible links between teachers’ backgrounds and their reported sources of joy, some teacher groups were more diligent in giving three responses, which may indicate that the question was not clear in stating that three responses were required. Thus, we cannot interpret the reasons some teacher groups responded with fewer than three sources of joy. In future studies, the wording of the questions should be more carefully considered.

A further limitation is that eliciting answers with a survey is always more limited than using interviews for data collection. Interviews could have brought a deeper understanding of teachers’ joys, but the online survey reached a higher number of respondents. Furthermore, the survey was created as a preliminary research instrument, and though it was based on an existing survey, it was not validated in Finnish before this study.

6. Conclusions

In general, the teachers had a positive stance toward multilingual students and listed a variety of joys related to teaching them with no significant outliers. This speaks to the importance of relationships and the many positive aspects of working with multilingual learners, even with consideration for the challenges of a diverse environment.

Teachers’ willingness to succeed is related to how they perceive their work and its meaningfulness. Thus, it is crucial to understand that opportunities for teachers to develop themselves both professionally and personally are important for their enjoyment of teaching; these may also increase their resilience (Aho, Citation2010; Bermejo-Toro et al., Citation2016) and make their work feel worthwhile. The teachers in our study reported that this development happened while working and interacting with multilingual learners.

With this article, we introduce some counter-narratives surrounding diversity and multilingual learners. The teachers’ main source of joy, according to our results, were the students themselves. This result may help also other teachers recognize their students’ strengths, which is important because “If you want students to emerge from schooling after 12+ years as intelligent, imaginative, and linguistically talented, then treat them as intelligent, imaginative, and linguistically talented from the first day they arrive” (Cummins, Citation2019).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aho, I. (2010). Mikä tekee opettajasta selviytyjän? Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1470. Tampereen yliopisto 2011. https://trepo.tuni.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/66711/978-951-44-7893-2.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Alisaari, J., Harju-Autti, R., Heikkola, L. M., Kekki, N., & Kivipelto, S. (2020). #Kielitietoisuus #kielellisestivastuullinenopetus #kielellisestivastuullistavaopetus – twiittejä käsiteviidakosta. Kieli, Koulutus Ja Yhteiskunta, 11(7). https://www.kieliverkosto.fi/fi/journals/kieli-koulutus-ja-yhteiskunta-joulukuu-2020/kielitietoisuus-kielellisestivastuullinenopetus-kielellisestivastuullistavaopetus-twiitteja-kasiteviidakosta

- Alisaari, J., Heikkola, L. M., Acquah, E. O., & Commins, N. (2019). Monolingual ideologies confronting multilingual realities. Finnish teachers’ beliefs about linguistic diversity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 80, 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.01.003

- Alisaari, J., Kaukko, M., & Heikkola, L. M. (manuscript). “Oppilaat sulkeutuvat omaan kieleensä” - Integraatio ja kielen oppiminen opettajien huolena.

- Aronin, L. (2019). Lecture 1. What is multilingualism? In D. Singleton, & L. Aronin (Eds.), Twelve lectures on multilingualism (pp. 3–34). Multilingual Matters.

- Back, L. (2003). Falling from the sky. Patterns of Prejudice, 37(3), 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313220307595

- Bermejo-Toro, L., Prieto-Ursúa, M., & Hernández, V. (2016). Towards a model of teacher well-being: Personal and job resources involved in teacher burnout and engagement. Educational Psychology, 36(3), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2015.1005006

- Björk, L., Stengård, J., Söderberg, M., Andersson, E., & Wastensson, G. (2019). Beginning teachers’ work satisfaction, self-efficacy and willingness to stay in the profession: A question of job demands-resources balance? Teachers and Teaching, 25(8), 955–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2019.1688288

- Chatman, J. A. (1991). Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Academy of Management Proceedings, 36(3), 459–484. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.1989.4980837

- Cummins, Jim (2001). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: California Association for Bilingual Education.

- Cummins, J. (2019, November 5). Supporting learning among linguistically and culturally diverse students: The roles of scaffolding academic content, literacy engagement, and identity negotiation [Seminar presentation]. Matkalla kielellisesti, kulttuurisesti ja katsomuksellisesti vastuulliseen pedagogiikkaan, Helsinki, Finland.

- Eisenchlas, S. A., & Schalley, A. C. (2020). Making sense of “home language” and related concepts. In A. C. Schalley, & S. Eisenchlas (Eds.), Handbook of home language maintenance and development. Social and affective factors (pp. 17–37). De Gruyter.

- Freire, P. (2017). Pedagogy of the oppressed (50th Anniversary ed.). Bloomsbury.

- Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

- Habermas, J. (1973). Theory and practice. (J. Viertel, Trans.). Beacon Press. (Original work published 1963).

- Hakanen, J., Bakker, A., & Schaufeli, W. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of Social Psychology, 43(6), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001

- Hargreaves, A. (2000). Mixed emotions: Teachers’ perceptions of their interactions with students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(8), 811–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00028-7

- Heikonen, L. (2020). Early-career teachers’ professional agency in the classroom [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Helsinki. https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/319653/heikonen_lauri_dissertation_2020.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress. Routledge.

- Howells, K. (2014). An exploration of the role of gratitude in enhancing teacher-student relationships. Teaching and Teacher Education, 42, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.04.004

- Kaukko, M., & Wilkinson, J. (2018). Praxis and language: Teaching newly arrived migrant children to “live well in a world worth living in”. TESOL in Context, 27(2), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.21153/tesol2018vol27no2art834

- Kaukko, M., & Wilkinson, J. (2020). ‘Learning how to go on’: Refugee students and informal learning practices. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(11), 1175–1193. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1514080

- Kemmis, S., & Edwards-Groves, C. (2018). Understanding education: History, politics and practice. Springer.

- Kemmis, S., Edwards-Groves, C., Jakhelln, R., Choy, S., Wärvik, G.-B., GyllanderTorkildsen, L. & Arkenback-Sundström, C. (2020) Teaching in critical times. In K. Mahon, S. Francisco, C. Edwards-Groves, M. Kaukko, S. Kemmis, & K. Petrie (eds). Pedagogy, Education and Praxis in Critical Times. Springer. P. 85–116.

- Kemmis, S., & Smith, T. J. (2008). Enabling praxis: Challenges for education. Sense Publications.

- Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage.

- Kumpulainen, T. (2017). Opettajat ja rehtorit Suomessa 2016. Raportit ja selvitykset 2017:2. Opetushallitus.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children. Jossey Bass.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

- Lindqvist, P., Nordänger, U., & Carlsson, R. (2014). Teacher attrition the first five years: A multifaceted image. Teaching and Teacher Education, 40, 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.02.005

- Lo Bianco, J. (2010). Some ideas about multilingualism and national identity. TESOL in Context, 20(1), 22–36. https://search.informit.org/doi/10. 3316/informit.449335083505513

- Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2011). A framework for preparing linguistically responsive teachers. In T. Lucas (Ed.), Teacher preparation for linguistically diverse classrooms: A resource for teacher educators (pp. 55–72). Routledge.

- Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2013). Preparing linguistically responsive teachers: Laying the foundation in preservice teacher education. Theory into Practice, 52(2), 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2013.770327

- Martela, F., & Pessi, A. B. (2018). Significant work is about self-realization and broader purpose: Defining the key dimensions of meaningful work. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(363). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00363

- Milbourn, T., Viesca, K. M., & Leech, N. (2017, April). Measuring linguistically responsive teaching: First results [Paper presentation]. American Educational Researchers Association annual meeting, San Antonio, TX.

- Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849209543534

- National Agency for Education. (2014). Perusopetuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet [Finnish Core Curriculum for Basic Education]. Määräykset ja ohjeet 2014:96. Retrieved on March 23, 2017, from https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf

- Nieto, S. (2013). Finding joy in teaching students of diverse backgrounds: Culturally responsive and socially just practices in U.S. classrooms. Heinemann.

- Nieto, S. (2014). Why we teach now. Teachers College Press.

- Nilsson, M., Ejlertsson, G., Andersson, I., & Blomqvist, K. (2015). Caring as a salutogenic aspect in teachers’ lives. Teaching and Teacher Education, 46, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.10.009

- Olin, A., Francisco, S., Salo, P., Pörn, M. & Karlberg-Granlund, G. (2020). Collaborative Professional Learning for Changing Educational Practices. In K. Mahon, S. Francisco, C. Edwards-Groves, M. Kaukko, S. Kemmis & K. Petrie (eds). Pedagogy, Education and Praxis in Critical Times. Springer. P. 141–162

- Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12441244

- Räsänen, K., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., & Väisänen, P. (2020). Why leave the teaching profession? A longitudinal approach to the prevalence and persistence of teacher turnover intentions. Social Psychology of Education, 23(4), 837–859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09567-x

- Runhaar, P. R., Sanders, K., & Konermann, J. (2013). Teachers’ work engagement: Considering interaction with pupils and human resources practices as job resources. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(10), 2017–2030. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12155

- Seltzer, K. (2019). Reconceptualizing “home” and “school” language: Taking a critical translingual approach in the English classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 53(4), 986–1007. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.530

- Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (2017). Language rights. In W. E. Wright, S. Boun, & O. García (Eds.), The handbook of bilingual and multilingual education (pp. 185–202). Wiley.

- Soini, T., Pyhältö, K., & Pietarinen, J. (2010). Pedagogical well-being: Reflecting learning and well-being in teachers’ work. Teachers and Teaching, 16(6), 735–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2010.517690

- Thomas, L., & Beauchamp, C. (2011). Understanding new teachers’ professional identities through metaphor. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(4), 762–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.12.007

- Valdiviezo, L. A., & Nieto, S. (2017). Culture in bilingual and multilingual education. Conflict, struggle, and power. In W. E. Wright, S. Boun, & O. García (Eds.), The handbook of bilingual and multilingual education (pp. 92–108). Wiley.

- Verplanken, B. (2004). Value congruence and job satisfaction among nurses: A human relations perspective. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 41(6), 599–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.12.011