ABSTRACT

This 2-year longitudinal study compares students’ trajectories for perceived teacher–student relationship quality and students’ self-efficacy (together discussed as students’ school trust) to previously documented teacher-perceived experiences in teacher teams’ collective learning processes. The article’s main contribution is the reflection in students’ perceptions, of their teachers’ perceived quality and attainment in collective learning processes. Comparisons between schools show that trajectories for students belonging to the only teacher team that experienced a more mature and successful learning process in an earlier study, differed significantly from the trajectories for students in compared teams. Differences demonstrated large positive effect sizes (d=0.81–1.14). Individual analysis provides deeper insights about how these students’ perceptions changed. Additionally, the full sample data confirms earlier findings of substantial cross-associations between student-perceived teacher–student relationship quality and student self-efficacy. For example, sustainable associations between supportive teacher–student relationships and students’ global academic self-efficacy and self-efficacy for self-regulative learning were found (r = 0.43–0.51).

Introduction

Methods other than averages from national tests, grades and eligibility for higher education to evaluate the quality of education and school improvement are called for (Allodi, Citation2013; Ashan & Smith, Citation2016; Biesta, Citation2010a). High-quality teacher–student relationships are widely considered fundamental to good education (Bingham & Sidorkin, Citation2004; Hattie, Citation2009; Noddings, Citation2005) and are considered to have the potential to positively impact on students’ self-efficacy to manage learning (Bandura, Citation1989; Klassen, Citation2010; Zimmerman, Citation1999). Moreover, to develop trustful relationships in schools is a prominent objective of teachers’ collective learning (Doğan & Adams, Citation2018; Owen, Citation2016; Tschannen-Moran & Barr, Citation2004). The main aim of this article is to investigate whether and how teacher-perceived quality and attainment in collective learning processes are reflected in students’ perceptions of teacher–student relationship quality (TSR) and self-efficacy (SSE). The study explores individual students’ perceptions of the interaction with their teachers alongside with students’ self-beliefs concerning their own possibilities to succeed within different domains in school. First, we investigate correlations and change over 2 years in individual students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE, which in this study together is tentatively discussed as students’ school trust in a wider sense. Next, change in students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE over 2 years are studied in relationship to their teachers’ perceived experiences in a collective learning process carried out during the same 2-year period, like reported in a previous study (Jederlund, Citation2019). We aim not only to explore students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE but also to discuss how these perceptions may change as a function of their teachers’ actions. Thus, this article reports quantitative results, and discusses them in the light of previous process findings (Jederlund, Citation2019). We want to contribute to the emerging bridge between School Effectiveness Research, which explores quantified school factors of general significance for achievement, and School Improvement Research, which studies qualitative aspects of relational school development (Biesta, Citation2010b; Hargreaves, Citation1997; Håkansson & Sundberg, Citation2016; Hopkins et al., Citation2014; Jarl et al., Citation2017).

Expanding the discussion of TSR and SSE in relationship to one another expresses the assumption that students’ agency beliefs as learners are to a substantial extent influenced by social relational features of the surrounding school environment where students’ interplay with peers and teachers are crucial parts (Bandura, Citation1989; Wentzel, Citation2012). Caring and supportive teacher–student relationships are decisive, especially for students experiencing weak social support from outside, in sustaining hope and for enabling engagement in more adaptive self-regulatory and social behaviour that support learning (Baker et al., Citation2008; Martin & Rimm-Kaufman, Citation2015). Furthermore, the way students think about themselves as learners, influences their interpersonal actions and how they interpret the response they receive from their peers and teachers (Klassen, Citation2010). The same goes for teachers. Teachers’ confidence in being good teachers for their students influences how they approach their students and interpret their responses (Bandura, Citation1989; Tschannen-Moran & Barr, Citation2004). The perceived quality of a certain relationship is mutually determined over time by the self-beliefs of both parties, by mutual expectations about one another and through the interpersonal exchanges performed. Relying on such a systemic understanding of teacher–student interplay, it becomes of great value to explore students’ perceptions of TSR-quality and SSE alongside their teachers’ actions.

Background

Teacher–student Relationship Quality and Student Self-efficacy

A high-quality teacher–student relationship has been found to predict students’ engagement and academic self-efficacy as well as achievement (Wentzel, Citation2012; Roorda et al., Citation2011; Hughes, Citation2011; Lee, Citation2012; Martin & Rimm-Kaufman, Citation2015). The way students perceive their teacher’s approach towards them and their peers, both as individual human beings and as learners, is critical to many students’ sense of security, optimistic outlook and engagement in class, as well as for students’ social participation in school. This observation especially accounts for students who struggle academically and possess low confidence in their self-regulative capabilities to handle learning (Baker et al., Citation2008; Hughes et al., Citation2012; O’Connor et al., Citation2011). Disengagement, low participation in class and negative attitudes towards school are associated with negative TSR trajectories in longitudinal studies (Henricsson & Rydell, Citation2004; O’Connor et al., Citation2011). However, a teacher–student relationship of high quality may give students possessing low academic self-efficacy a sense of trust that promotes risk taking, curious exploration and persistence in face of difficulties. Further, TSRs of high quality are associated with more positive social self-views and school adjustment and negatively with externalizing and internalizing negative behaviours and school dropout (Croninger & Lee, Citation2001; O’Connor et al., Citation2011; Rudasill et al., Citation2010; Spilt et al., Citation2018).

Social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1989) posits that teachers’ approach to students has a big impact on students’ self-efficacy. Teacher response to students’ actions, successes and failures may be either favourable or unfavourable to students’ self-efficacy judgements (Bandura, Citation1989; Zimmerman, Citation1999). Some literature supports an association between perceived TSR quality and students’ self-regulative and academic self-efficacy. Hughes et al. (Citation2012) found students’ perceptions of warmth and support in TSRs predicted positive change in student-perceived academic self-efficacy, and Li et al. (Citation2012) found associations between student reported supportive TSRs and subject-specific self-efficacy in maths and reading. In Hughes et al.’s (Citation2012) study, students’ perceptions of conflict in TSRs were negatively associated with students’ maths self-efficacy. Finally, in a recent Swedish study that explored a multi-factor model of TSR and SSE (Jederlund & von Rosen, Citation2021), substantial correlations were found between student-perceived “TSR-support” and students’ self-regulative and global self-efficacy.

Perceptions of TSR Quality and SSE

International research shows students normally score high on various TSR-quality scales (Hughes, Citation2011; Wentzel, Citation2012). This could be explained by the generally high levels of relational qualities of education. However, to some extent, it may also be the effect of students’ bias towards sustaining a positive outlook and expressing positive judgements about their teachers. TSR quality in relationships between teachers and older students is generally rated lower, by both parties, than between teachers and younger students. In a few longitudinal studies carried out on individual students’ perceptions of TSRs, the students rated TSR quality in middle school higher than they did later in secondary grades (Hughes et al., Citation2012). In addition, girls scored generally higher than boys, and academically at risk students scored lower on “support” and higher on “conflict” when compared to non-at-risk students (Henricsson & Rydell, Citation2004; Hughes et al., Citation2012). Similar negative deviations for older students and for boys are found in several studies examining teachers’ perceptions of TSR quality, and for students whose ethnic backgrounds differ from their teachers’ backgrounds and for students who receive special educational support (Murray et al., Citation2008; Saft & Pianta, Citation2001). In keeping with what is reported on students’ TSR scores, students in general score high on different SSE scales. According to earlier studies, girls score higher on self-regulative self-efficacy than boys do (Pajares, Citation2002), and students’ overall self-efficacy judgements decrease as students’ progress from elementary to higher school levels (Fertman & Primack, Citation2009; Usher & Pajares, Citation2008). Students with different ethnic backgrounds and academically at risk students are also more likely to score low on social- and academic self-efficacy scales than are other students (Klassen, Citation2010).

Concordant with the literature, this study hypothesizes that students in general score high in regard to both TSR quality and SSE, but with a general decline over time. Further, it is hypothesized that girls score higher than boys and that younger students score higher than older students in both constructs.

Students’ School Trust

Trust can be conceptualized in various ways, but most definitions of trust have in common the positive expectation on actions of individuals, or actors, that you depend upon (Van Maele et al., Citation2014). Trust is expressed in mutually respectful relationships where people feel safe enough to risk their vulnerability to achieve goals because they see others as benevolent and reliable and as acting in ways that are beneficial, or at least not harmful, to themselves (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2000). In our reasoning, school trust includes students’ perceptions of quality in important teacher–student relationships as well as students’ confidence in handling social relationships in school, confidence for self-regulation of learning, and trust in global school success. To risk vulnerability at school (e.g., raising hand in class, showing own difficulties, asking for help), students rely on high-quality relationships with teachers and peers. They also rely on their own capability for self-regulation, i.e., to make efforts worthwhile, to engage, to concentrate, to keep order, to keep performing a task and to deliver on time (Bandura, Citation1989). Self-regulation of one’s own learning does not only include individual aspects of students’ school life but is also dependent on trustful relationships.

Influence of Teacher Collective Learning on TSR Quality and SSE

When teachers engage in “mature” professional learning communities (Owen, Citation2016, p. 404) – joint mapping of students’ needs, joint action for improvement and joint monitoring of processes – they step into a sphere of “relational school development”, since its foundations are collegial collaboration and shared responsibility. Teachers need to risk vulnerability and trust in colleagues’ benevolence and competence while engaging in joint action. Mature professional learning communities aim for teachers’ wellbeing by means of establishing high-quality learning environments, including interpersonal relationships with colleagues, school leaders and students. Roffey (Citation2012) argues that at all levels such environments involve “trust, respect, value, and collaboration” (in Owen, Citation2016, p. 407).

In collective learning processes that include joint exploration and development of daily practices teachers will encounter demands for visibility, extended collaboration and trying new actions. Developed practices may in turn affect teacher–student interplay in ways that affect students’ perceptions. Even though no studies directly look at the effects of teacher collective learning on student-perceived TSR-quality or SSE, some studies indicate associations between professional learning, teacher collective efficacy and achievement (e.g., Goddard et al., Citation2015; Owen, Citation2016). In addition, a number of studies discuss how these effects are mediated from teachers to students. The findings imply that teachers’ engagement in collaborative instruction and the joint focus on student learning and wellbeing, together with external support (principal support, counselling) for teachers’ processes, led to increased formative dialogues between teachers and students and promoted student-student interaction and engagement (Doğan & Adams, Citation2018; Owen, Citation2016; Tschannen-Moran & Barr, Citation2004).

Furthermore, Ramberg, Låftman, Almquist and Modin (Citation2018) have shown, using big Swedish samples of ninth graders and teachers from the same schools (n=8022/2073), that student-perceived “teacher care” is associated with teacher-perceived qualities of “school leadership”, “school ethos” (values and beliefs that permeate school) and “teacher cooperation and consensus”. Multilevel analyses on school improvement have shown that organizational facets like school leadership, organizational beliefs and teacher collaboration are intertwined impact factors on teachers’ collective learning processes (Louis & Murphy, Citation2017; Louis & Lee, Citation2016; Goddard et al., Citation2015; Ramberg et al., Citation2018). For example, Goddard et al. (Citation2015) explored a model in which school leadership, teacher team collaboration and collective efficacy, and school social climate are related to achievement. Based on studies in American and Australian schools (Clark & Goddard, Citation2016; Goddard et al., Citation2015), associations found between achievement, social climate and teacher collaboration in instruction rely on teacher trust in school leadership:

the degree to which staff reported collaborating on instructional improvement was strongly predicted by the strength of their school leadership team’s instructional leadership. (Clark & Goddard, Citation2016, p. 4)

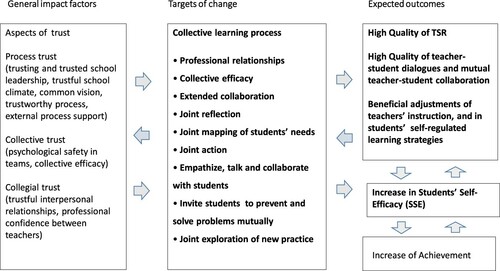

However, the above studies do not address how organizational facets like collective learning influence student achievement, i.e., what factors may be the mediators at the student level. We posit that teachers’ collective learning primarily have the potential to directly influence daily teacher–student transactions by means of, e.g., developed formative dialogues, pro-active adjustments of instruction and mutual problem solving between teachers and students. We assume that such qualities of teacher–student transactions (TSR quality) may enhance students’ social participation, increase engagement in the classroom and assist students to develop self-regulative learning strategies. Such new experiences then can strengthen students’ general school trust and contribute to achievement. We also assume that these processes are reversible. The suggested systemic relationships are illustrated in the model in .

Research Questions

This article focuses on the middle and upper right side of the model in . As stated in the Introduction, the main aim of the article is to investigate whether and how teacher-perceived quality and attainment in collective learning processes are reflected in students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE. Two research questions were asked:

RQ1. How do students perceive TSR quality and SSE in general, and how do these perceptions correlate and change over 2 school years?

RQ2. How do changes over 2 school years in students’ perceptions of TSR quality and SSE reflect their teachers’ perceived quality and attainment in collective learning processes carried out during that same 2-year period?

Earlier Reported Experiences of Teachers’ Collective Learning Processes

The present study is based on quantitative analyses using students’ scoring of TSR quality and SSE at three time points over 2 years. However, the obtained results are to a significant degree discussed in the light of earlier reported (Jederlund, Citation2019) evaluations and qualitative process reports from teachers and school leaders in 3 schools that completed a collective learning process during that same 2-year period. Therefore, this section describes the teachers’ evaluation and process experiences in concentrate as reported in the previous study (Jederlund, Citation2019). Following this, the method description of the quantitative analyses in the present study is presented.

The collective learning process consisted of a 2-year group counselling process that aimed to develop teacher collaboration and improve teacher–student interplay (Jederlund, Citation2019). The core of the process was collective reflection on the daily experiences and challenges in teachers’ interactions with students, as well as collaborative teacher action, by means of the joint mapping of school difficulties and students’ needs and the joint planning, performing and monitoring of improvement efforts together with students. Teacher–student talks were to be videotaped in order to make teachers’ practices visible to collective reflection, and to make improvement efforts subject to collective responsibility. One teacher team at each of 5 public schools in a Swedish large city county joined the study. The criteria for participation were school leaders’ active interest and organizational support and teachers’ engagement in the anchoring process. Counsellors were external and experienced educators, who were qualified and trained for group counselling in school contexts. The author acted as a counsellor at one school. In total, 37 teachers, 13 school leaders and 4 counsellors took part. Only teacher teams in 3 schools (School 1, 2 and 4) completed the collective learning process over 2 years, while the teams in School 3 and 5 ended the process after 1 year due to various local circumstances (see below, and for details Jederlund, Citation2019).

After 2 years, the teachers evaluated process impact on different levels at school. In addition, a qualitative in-depth analysis was carried out on participating teachers’ and school leaders’ process experiences. The main results from the 3 schools that completed their processes over 2 years are briefly reproduced here (for detailed information, see Jederlund, Citation2019). In the evaluation, the teachers assessed the degree to which the goals they had set in advance had been fulfilled, and the impact of the process on teachers’ collaboration, on participating students’ engagement, and on students at school in general. A total index of all assessments was calculated. It showed vast variation between schools: At School 1 and School 4 the teacher-perceived process impact was neither big nor small (rank point means of 2.98/3.00 respectively), while at School 2 the perceived impact was large, with a mean of 4.10 from a maximum of 5. The qualitative analysis showed that teachers’ experiences of trust at 3 different levels were decisive for the teachers’ perceptions of process quality and outcome. Process trust and collective trust (see above) showed to be prerequisites for enduring the process in schools 1, 2 and 4. These facets of trust were weak in the 2 teacher teams that ended the process after one year. For example, teachers and school leaders expressed different objectives, and organizing and conditions for teachers’ participation were subject to discussion. In addition, teachers expressed doubts about the collective efficacy of their team and a lack of trust in interpersonal relationships between colleagues. Indeed, beyond a determined school leadership and a common vision, collegial trust (see ) appeared to be a special prerequisite for the more successful process perceived by the teachers at School 2. They said trustful relationships and professional confidence enabled individual risk taking and the sharing of one’s own shortcomings with students. Likewise, collegial trust was said to promote mutual visibility of practice, which was embodied in frequently made video-recordings of teacher–student transactions and in new forms of direct collaboration, according to the teachers (Jederlund, Citation2019).

The study (Jederlund, Citation2019) concluded that teachers in School 2 experienced and outlined a deeper and more mature collective learning process, which was characterized by trustful relationships, mutual visibility in practise and extended collaboration in action, when compared to the teachers of the other teams.

In line with the teachers’ reported advantageous process experiences (Jederlund, Citation2019), in the present study, we hypothesize that the change trajectories of students’ perception of TSR quality and SSE in School 2 will deviate from an expected decline over time, and, above all, will deviate from the change trajectories of students’ perceptions of TSR quality and SSE in compared schools.

Method

Measure

The “Swedish TSR-SSE survey” was created for the purpose of monitoring relational school development processes by means of students’ perspectives of relational qualities in education (Jederlund & von Rosen, Citation2021). Its origins lay in 2 American instruments; one each from the respective TSR and SSE fields. The TSR part builds both on Weiss’ (Citation1974) theory of social provision and support and on Furman and Buhrmester’s (Citation1985) “Network of Relationships Inventory” (NRI), which have added the 2 dynamic dimensions of interpersonal relationships “relative power” and “conflict” to Weiss’ social support dimensions. Jan Hughes (Citation2011) later adopted the NRI for school research purposes in the “Teacher Relationship Inventory” (TRI). This investigates 3 dimensions of quality in the teacher–student relationship: support, conflict and intimacy. The SSE part builds on Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, Citation1989) and various self-efficacy scales that were successively developed by researchers (Fertman & Primack, Citation2009; Usher & Pajares, Citation2008; Zimmerman & Martinez-Pons, Citation1988) from the original items of Bandura’s (Citation1990) “Multidimensional Scales of Perceived Self-Efficacy”, in various scales such as academic self-efficacy, self-efficacy for self-regulated learning and self-efficacy for peer social interaction. In total, 37 items were translated and adopted in the Swedish instrument. The instrument contained 7 subscales, with high Cronbach α’s in the validation study (Jederlund & von Rosen, Citation2021), and even higher alphas in the present study (see ). Students responded to all items by choosing from response alternatives on a 5-point Likert scale.

Table 1. Subscales with Cronbach alphas and sample items of the Swedish TSR–SSE survey.

Participants and Procedure

Middle-school students (4th–6th grade) and secondary-school students (7th–8th grade) from 5 public schools were invited to respond to the Swedish TRS-SSE survey on a voluntary basis. All participants consented to participate with their caregivers’ approval, and they responded to the survey at three time points over 2 school years (n=382/372/332). None of the received questionnaires have missing data.

At invitation, each of the 5 schools had one teacher team participating in an intended 2-year collective learning process (participating teachers in the respective teacher teams in Schools 1/2/3/4/5, n = 8/8/7/7/6). Students belonging to these teacher teams together accounted for just over half of the full sample (see , column 7). Other survey-responding students comprised a group of students whose teachers did not participate in the collective learning process.

Table 2. All invited students, proportion consented, participants and attrition, and general school information.

In regard to RQ 1, the full sample data was used for the overall investigation of students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE and the trends in these perceptions over two years, as well as the association between the two constructs.

On the other hand, as mentioned above (p. 6), only teacher-teams in 3 schools completed the collective learning process over 2 years (participating teachers during the second year in Schools 1/2/4, n = 7/9/5). Therefore, in regard to RQ 2, only data from these 3 schools were analyzed. Furthermore, in the process, the teachers directed their improvement efforts mainly toward students belonging to the own team. Hence, in regard to RQ 2, these students established the study group of interest. We label this group as the Process-Participating Teachers’ Student group (PPTS group) from now on, reflecting that these students were the targets for their teachers’ collective action.

The 3 data collecting points were before the collective learning process started, after 1 year and at process end after 2 years. Note, student data collected at time point 1 was also used before in the validation study (Jederlund & von Rosen, Citation2021), while student data collected at time points 2 and 3 are analyzed in the present longitudinal study only.

The proportion of invited students that consented to participate in the survey varied notedly between the 5 schools. Among participants, however, attrition was small over time points and for most part caused by students having changed schools. In some cases, attrition was due to temporary absence. The differences in participation are further commented on in the discussion. Information on all survey-responding students and school information is provided in .

Statistical Analysis

Means for the full sample and for each school were calculated on all items and for each construct and subscale to explore students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE over time. Inter-correlations between scales were estimated using Pearson correlation coefficients (r). Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted in order to test whether there is a school effect on TSR and SSE measured over three time points, respectively. To compare change over 2 years between individual schools, a t-test has been used for computed scale differences between time points 1 and 3, which is denoted by the delta (Δ). Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d, and change magnitudes were interpreted using restrictive levels of Cohen’s d indices: d=0.20 a small effect, d=0.50 a medium effect and d=0.80 a large effect (Kraft, Citation2018). The significance level for all analyses was α=0.05. Analyses were run using SPSS, version 25.

Since PPTS group students’ trajectories at School 2 notably deviated from the trajectories of the corresponding groups in compared schools, student data from this school was explored at individual student level, to get an in-depth view of the actual change. We analyzed paired ordinal data using an augmented ranking approach (Svensson, Citation2012) in order to display disagreement/agreement between the students’ responses at different time points.

Results

In order to respond to RQ1, we calculated means for TSR and SSE and for all 7 subscales for each of the three time points, see .

Table 3. Means and standard deviations for TSR, SSE and seven subscales at three time points. Schools 1–5, full sample.

Students in all schools scored high in general on self-efficacy (SSE). The lowest scores, with medians of 3, were observed for the items “I feel confident that I can always concentrate during class” (SSE3) and “I feel confident that I can get myself to study also when there are more fun things to do” (SSE1). The highest scores (median=5) were found in the peer social interaction self-efficacy scale (SSE2) for items concerning making friends (e.g., “I feel confident that I can get and keep friends of the opposite sex”). In the global self-efficacy scale (SSE3) ratings were notably high for items expressing students’ thriving and global expectations in school (median=4). Similarly, high scores were obtained for students’ self-efficacy for self-assertiveness (SSE4), in which the response alternative “perfectly apply” was the most frequent.

As expected, students scored high on teacher–student relationship support (TSR1) and conflict (TSR2),Footnote1 meanwhile scorings for intimacy (TSR3) were remarkably lower. The lowest, with medians of 2 and some responses “not at all” were for the variables “How much do you talk to your teacher about things that you do not want others to know?” and “How much do you share personal things and feelings with your teacher?” Intimacy concerns a more personal and close aspect of the teacher–student relationship, and Swedish students seem to perceive such relationship qualities to a lesser degree. The highest scores (median=5) were found for several items on the conflict scale, which suggests that students in general and to a small extent perceive their TSRs as negative, authoritative or conflictual.

Group Comparison

Swedish girls’ and boys’ perceptions of TSR quality and SSE to a degree contradict international findings. In our full sample, girls score consistently lower than boys on TSR-support, TSR-intimacy and TSR in total, although not significantly. However, in concordance with international findings girls perceive significantly less conflict with teachers than boys (d=0.26, p-value=0.0135, for aggregated measures). Further, girls score significantly lower than boys on all SSE subscales. Girls are clearly outperformed by boys in all measures and in particular concerning self-efficacy for self-assertiveness in social interaction (SSE4). The inferiority of girls’ aggregated scorings on self-assertiveness is demonstrating a close to medium effect size (d=0.46, p-value<0.0001). A plausible explanation for the diverging results concerning gender, as compared to the international findings, may be cultural differences in gender roles and the surroundings’ expectations of girls and boys in Swedish school contexts when compared to, for example, American ones. Nevertheless, this needs further investigation.

Comparisons between middle-school students and secondary-school students confirm earlier findings. Younger students perceive higher quality in their TSRs and possess stronger self-beliefs and expectations about schooling than older students, however, these differences represent small effect sizes. Advantages of younger students in the TSR-support and self-regulative self-efficacy scales were statistically significant at time point 2 (p-values=0.044/0.036, d=0.21/0.22). The clearest difference shows the TSR-intimacy scale at time point 1 (d=0.38, p-value<0.001) and time point 2 (d=0.26, p-value=0.014), and the difference remains at time point 3, however not significant. The decreasing difference can likely be explained by the fact that the age of the youngest responding student group continuously rose. There were 2 exceptions to the general pattern. Secondary students perceived less conflict in TSRs (significant at time point 1, p-value=0.027, d=0.23), and possessed higher self-efficacy for self-assertiveness together with peers when compared to middle schoolers in all measures, although not significant. These hinted differences both are conceivable, due to elderly students’ generally more developed social skills.

Correlation Patterns

Evaluation of the correlation matrices between all subscales and over time (see ) confirms correlation patterns found in the validation study (Jederlund & von Rosen, Citation2021). Noteworthy, are the vast and stable cross-associations between TSR-support (TSR1) and students’ self-efficacy for self-regulative learning (SSE1) and global school success (SSE3), with r ranging between 0.43 and 0.51. Further, each of these 3 subscales is associated with all other subscales. In contrast, TSR-conflict (TSR2) shows negligible correlation to TSR-intimacy (TSR3) and, more expectedly, to subscales concerning student-student interaction (SSE2 and SSE4). Of importance, are the sustainable association over time between the global constructs of TSR and SSE.

Table 4. Intercorrelations between all subscales, and between TSR_total and SSE_total at timepoints 1, 2 and 3 (tp 1–tp 2–tp 3).

General Trend Over 2 School Years

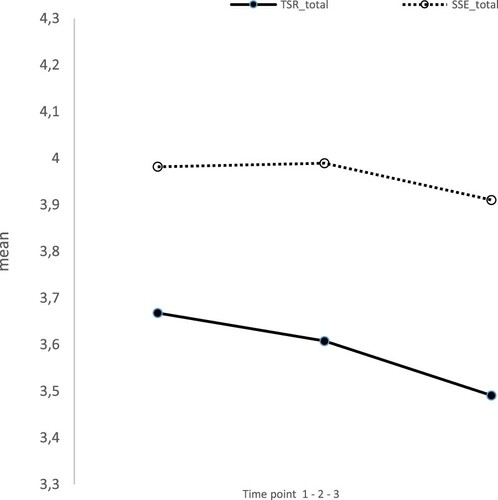

The descriptive analysis and data support the hypothesis of an overall decline in student-perceived TSR quality and SSE over time. The decline is most obvious in the TSR1, TSR3, SSE1 and SSE3 subscales and for TSR in total. Only 2 out of 9 scales, the SSE2 and the SSE4 that concern students’ social interaction and self-assertiveness together with peers, deviate from the expected decline by showing a slight increase in total scores (largely accounted for by secondary students in school 5). To illustrate change over 2 years for TSRtotal and SSEtotal, the trajectories are displayed below in . The decline of all marginal means are statistically significant (TSR p-value < 0.0001, d=0.50, and SSE p-value=0.007, d=0.23)

Change in Trajectories at School Level

Since TSR and SSE have been measured over three time points, a MANOVA was conducted in order to determine whether schools differ in TSR and SSE, respectively. This analysis showed that students’ trajectories differed significantly between schools, for TSR (Wilk’s λ=0.847, p-value<0.0001) as well as for SSE (Wilks λ=0.928, p-value=0.021). In continuation, the differences among individual schools have been investigated.

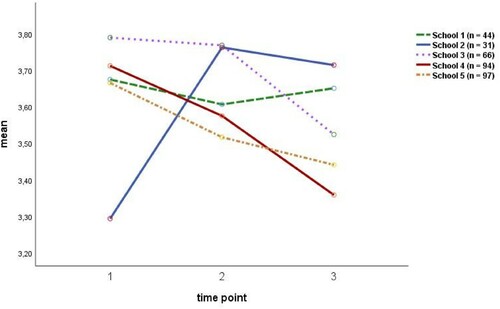

First, full sample analysis was conducted in order to test the hypothesis that students’ trajectories over time for perceived TSR quality and SSE at School 2 will deviate from the expected trend of general decline. An illustrative example of outcomes is displayed in , which shows the average trajectories for TSR across three time points.

The main observation is the crossover of trajectories for School 2 in relationship to other schools. From being lowest at the start, School 2’s trajectory comes out highest at time point 2, and it remains on top after 2 years. The difference between the change magnitude for TSR at School 2 as compared to the averaged change magnitude in the other schools (Δ = 0.660) is statistically significant (p-value < 0.0001) and represents a large effect size (d = 0.99) (see , right column). thus supports the hypothesis that change in School 2 students’ TSR-scorings deviate from the expected average decline, which indeed was the general trend in the full sample. A similar deviation from an expected pattern of general decline also occurred for School 2 students’ SSE scores, however here, the difference represents a smaller effect size (d = 0.43, p-value = 0.024, see ). Note that, at time point 3, the PPTS group in schools 3 and 5 (n=45/25) belonged to teacher teams that ended their collective learning process after time point 2. This could possibly have influenced the average trajectories for TSR and SSE during the second year, to some extent.

Table 5. Change differences, significances and effect sizes between School 2 and compared schools.

Next, we turned to RQ 2, and investigated if and how students’ perceptions of TSR reflected their teachers’ perceived quality and attainment in the 2-year collective learning process. We conducted more in-depth analyses in order to test our assumption that students’ trajectories of TSR and SSE in School 2 will substantially deviate from students’ trajectories in compared schools. Then we delimited the comparison to students in School 1, School 2 and School 4 because, as stated above, the teams in Schools 3 and 5 ended the process already after one year. Moreover, since teachers directed their improvement efforts mainly toward students belonging to their own team, all further comparisons are delimited to the corresponding PPTS group. Note that in School 2 all participants belonged to the PPTS group, while the PPTS group made up a minor part of the School 1 sample, and a major part of the sample in School 4.

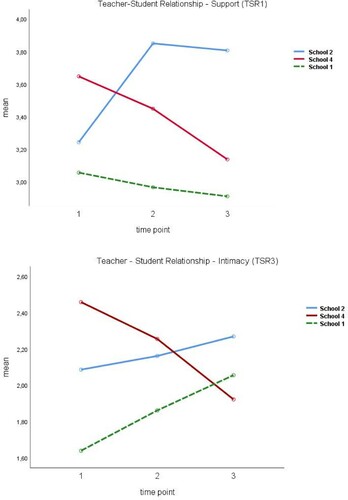

When comparing trajectories of PPTS group students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE the crossing trajectories found in the full sample re-occurred between School 2 and School 4. In contrast to the full sample comparison, School 1’s PPTS group, comprising a small group of secondary students, scored lowest all the way through, with only one exception (see below, and for illustrations).

Figure 4. PPTS group students’ trajectories of TSR-Support and TSR-Intimacy. Schools 1, 2 and 4 (n=12/31/64). For deltas, significances and effect sizes in comparisons, see .

To evaluate the magnitude of change differences among School 1, School 2 and School 4, deltas for all scales were compared, and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated. When comparing trajectories within PPTS groups between School 2, and School 1 and School 4 respectively, the results are convincing. Change in mean estimates from time points 1 to 3 show a positive direction for all 9 measures at School 2, while change in mean estimates both at School 1 and School 4 are negative for all measures, with only one exception each. At School 4 the TSR2 (conflict) shows a slight increase, and at School 1 the TSR3 (intimacy) outlies remarkably (Δ=0.42, d=0.53), although not significant due to the small number of students.

In , the “mean delta” column displays the magnitude of the difference in deltas from time points 1 to 3 (tp3–tp1) in each measure between School 2 and the compared schools. Most delta differences indicate substantial effect sizes. The superiority of School 2’s trajectories as compared to School 4’s trajectories manifest in large effect sizes for TSR in total, TSR1 and TSR3, and medium effect sizes for SSE in total and SSE1. The superiority of School 2’s trajectories as compared to School 1 yields large effect sizes for SSE in total, TSR2, SSE1 and SSE3, and a medium effect size for TSR in total.

In the next step, trajectories for the subscales showing the largest effect sizes in comparisons were further investigated. In , these comparisons are exemplified with trajectories for TSR-support and TSR-intimacy.

Actual Change at Individual Student Level

All trajectories above represent change in averages for all variables on the scales. Hence, we do not know in which specific items a student’s judgements changed, or how judgements changed. Neither do we know if most, several or only a few students’ scorings actually changed. In order to examine the nature of change patterns – the “how” – we undertook individual analysis of all 33 School 2 students’ assessments of all variables in all measures. The findings of this analysis, at student-item-time point level, are summarized next. In the descriptive summary, students are clustered as “most students” (n=17–33), “several students” (n=9–16) and “some students” (n=3–8).

The largest individual changes appear within the TSR-support domain. Here, most students perceive an increase in general quality of TSRs and appreciate more teacher support in learning. Most students further appreciate more secure and caring relationships with their teachers. As far as TSR conflict is concerned, just some students noticeably change their perceptions over time, but for those who do, the change is of particular importance since they actually experience a vast decrease of conflict with their teachers. Of similar importance, it may be argued, are the changes for some/several students in perceived TSR-intimacy and in self-efficacy for peer social interaction and self-assertiveness. These changes appear mostly after 2 years, meaning that developing interpersonal trust and relational skills takes time. In the self-efficacy for self-regulative learning domain, changes appear for most students, but of a somewhat less magnitude than for TSR-support. Variables expressing concrete self-regulation of learning show the largest improvement. On the global self-efficacy scale, several students express increased confidence to be able to concentrate. And even though reporting a decline in several specific SSE variables, most students possess an optimistic global outlook of schooling. Some students report a large increase of global school hope already after one year.

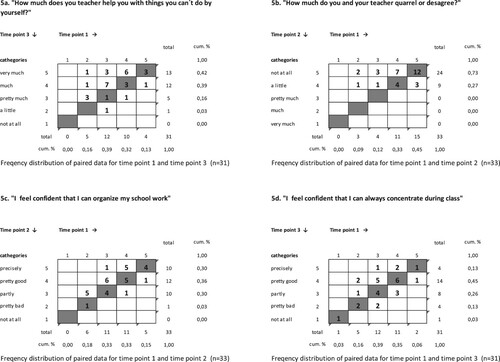

To elucidate in detail School 2 students’ change (or no change) in perceptions of TSR and SSE between time points, we finally conducted a rank order analysis on paired data (Svensson, Citation2012) for all individual students’ intra-variable agreement/disagreement. Students’ rankings on 4 representative variables are illustrated below in .

Figure 5. Contingency tables for paired individual student response to 4 variables at different time points.

In (a–d), frequency distributions of students’ chosen response alternatives are displayed in contingency tables. The “agreement diagonal” (from lower left to upper right) contains counts of “no change” in data pairs. Counts in cells above the diagonal show positive disagreement (higher rank at later time point), and counts in cells below the diagonal show negative disagreement (lower rank at later time point). The more distant the paired observation from the agreement diagonal, the more disagreement between students’ perceptions at the two time points, i.e., the more change. For example, in (a) the variable “How much does your teacher help you with things that you can't do by yourself?” reveals that data pairs from 7 students (1 + 3+3) show no disagreement between time points 1 and 3. However, 3 students (1 + 1+1) show negative disagreement and 21 students (3 + 7+6 + 1+3 + 1) show positive disagreement. Of the latter, 4 (1 + 3) have increased 2 positions, and 1 (1) has increased 3 positions.

(b) illustrates that 6 students (1 + 3+2) increased their ranking with 2 or 3 steps over a year, which indicates a vast improvement in their TSRs by means of less perceived conflict. (c,d) illustrates that there was less magnitude of change in SSE variables and that there was a wider distribution of students’ perceptions. The latter especially applies to students’ confidence to concentrate (5d). For this variable, despite an increase in average for one-third of the students (1 + 5+2 + 2+1), 6 students (2 + 3+1) report deterioration.

Discussion

Based on the background theory and vast research, building high quality TSRs ought to be an integral part of educational improvement. Nevertheless, teacher training, vocational programmes and learning communities seldom have an expressed relational ambition (Woodland Citation2016; Doğan & Adams, Citation2018; Wubbels et al., Citation2014). Moreover, students’ perceptions of relational qualities of education are rarely used as indicators of school improvement. In this article, we explore a possibility to track teachers’ developed collective action by means of students’ perceptions. The main aim was to investigate whether and how teacher-perceived quality and attainment in collective learning processes were reflected in their students’ perceptions of TSR quality and SSE.

Our main finding is the parallelism and consistency shown in 3 schools between trends over 2 years in students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE, and their teachers’ differently perceived quality and attainment in collective learning processes carried out during the same period.

In a previous study (Jederlund, Citation2019), only the teacher team in one school (School 2) performed and endured a collective learning process in a way that could be categorized as a mature, highly developed professional learning community (Doğan & Adams, Citation2018; Owen, Citation2016). In the present study, only students belonging to that team demonstrated a positive change in perceived TSR quality and SSE. Further, students in School 2 scored lowest of all in both constructs at the beginning of their teachers’ process but highest of all after 1 year. To be able to understand these differences between the schools, the qualitative process and school information obtained in the earlier study (Jederlund, Citation2019) is now beneficial. School 2 students’ weaker perceived TSR quality and SSE beliefs at start may be one clue to the positive trajectories that followed, as the foundation for teachers’ strongly sensed need for improvement. Students at School 2 had repeatedly performed lower than expected in relation to national standards and demographics, and the school was targeted for inspection. The new principal was determined and highly engaged in supporting the teachers’ process. The principal consistently communicated a vision for the school in terms of all teachers’ shared responsibility for students and security and thriving for all students and employees. The teachers’ collective learning process was declared concordant with this vision. The school leaders further reported they monitored the process closely, with explicit demands for improvement, but at the same time trusted in the teachers’ change potential and in the counselling process (Jederlund, Citation2019). In retrospect, the teachers’ collective learning process was characterized by process trust, trustful collegial relationships and collective efficacy. The teachers reported that trust paved the way for visibility in practice and for joint exploration of new forms of teacher–student transactions (Jederlund, Citation2019). Concordant with multilevel analyses of school development (Goddard et al., Citation2015; Louis & Lee, Citation2016; Louis & Murphy, Citation2017), we believe School 2 teachers’ mature improvement process relied on the complex interaction between trusted and trusting school leadership, acknowledged improvement needs, common vision, and good prerequisites for teachers’ collective learning and external support. We see the new forms of teacher–student interaction, with developed dialogues in and about learning, together with an adjusted teacher approach to students (empathizing, asking for students’ perspectives, seeking collaborative solutions, less conflicting), as plausible moderators of the positive change in School 2 students’ perceptions.

In our deepened analysis of how School 2 students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE changed, the obtained results confirm that individual students felt more secure, more liked and taken care of together with their teachers and better supported in learning. Things had clearly improved for students experiencing high conflict in their TSRs from the start, and several students reported that they could more easily speak to their teachers about important things when needed. The substantial improvement after only 1 year is of particular interest. It may be explained by the tangible transformation in teachers’ approach that met students (Owen, Citation2016). The collaborative teacher–student talks in which teachers asked for students’ perspectives on challenges, together with actual adjustments of the teacher approach and in instruction, from one semester to another, established completely new experiences for students that may rapidly have raised trust in teachers. Here, it can be noted the change in School 1 students’ trajectories for TSR after time point 2 (), which reflects teachers’ and school leaders’ process reports of progress in teacher collaboration and joint action in the school as a whole, during the second year (Jederlund, Citation2019). If this is true for teacher–student interaction, what can be said about the link to self-efficacy? Within a more trustful and collaborative teacher–student interplay, teachers may more easily promote students’ engagement and pro-social behaviour, better support students in developing adaptive self-regulative learning strategies and shape a stronger sense of students’ “school agency” (Bandura, Citation1989; Klassen, Citation2010). Our results suggest that teachers’ successful collective learning process in School 2 positively influenced their students’ TSR perceptions, and also their self-efficacy, although to a lesser extent. This finding is expected given the nature of the teachers’ actions and is in concordance with Hughes et al. (Citation2012) and Li et al. (Citation2012), who suggested that high-quality TSR is predictive of achievement, mediated through students’ raised self-efficacy.

Further, our full sample data extend earlier findings (Jederlund & von Rosen, Citation2021; Hughes, Citation2011; Li et al., Citation2012) of the association between student-perceived TSR quality and SSE. Associations appear both cross-sectional and longitudinal. We found substantial associations between TSR-qualities and self-efficacy for self-regulative learning and facets of self-efficacy in social interplay, with important examples like the ability to concentrate during class, to organize schoolwork, to ask a friend for help and to stop maltreatment. The results support further use of students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE as parallel quality indicators of learning environments and school improvement efforts. The substantial associations found between TSR and SSE invite to deeper theoretical and empirical research on the relationship, and to exploration of the possibility to develop a combined model of TSR and SSE (“School trust”).

Due to its design, this study has certain limitations, and therefore any generalization of the results cannot be made. Both the number of teacher teams and participating students are relatively small, and the selection of students was ruled by their schools’ choice to participate in a teacher-team-based learning process. Besides, the appropriate student group for our study was delimitated to 3 schools, since the teams in 2 schools quitted their processes after 1 year. School 2 students, who were selected for deeper analysis, all belonged to a process participating teacher team, which was the only teacher team of this small school. Hence, it is possible that the teachers’ improvement efforts more easily reached the students. School 2 teachers’ earlier reported positive process experiences, as well as the positive change in their students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE found in this study, must be considered with regard to this. Although we build on teachers’ own reports and possess extensive process and school information (Jederlund, Citation2019), the question must be raised of whether any other circumstances than the teachers’ collective learning process contributed to the deviating trajectories. There is still the possibility that the deviating trajectories for School 2’s students are due to unknown factors, or to chance.

Further, questions must be raised concerning the small number of participating students at School 1. According to teachers’ and school leaders’ reports, the reasons for poor recruitment were weak process engagement among some of the staff and a school history of weak school-home relationships (Jederlund, Citation2019). Moreover, our present analyses disclosed that the few School 1 students belonging to the PPTS group were non-representative. On the other hand, at School 4 the proportion of consenting students was acceptable (55%), and the PPTS group (n=80) established a valid comparison group to School 2’s students (n=33). Finally, the fact that the author counselled at School 2 may be another impact factor, even though teachers in School 1 and 4 reported a similar satisfaction with counselling (Jederlund, Citation2019). However, these uncertainties only have a negligible effect on the purpose of this study. Our ambition was not to discuss different prerequisites for school improvement or to explain different outcomes of any specific intervention or counselling model, but instead, it was to investigate whether and how teachers’ perceived quality and attainment in a 2-year collective learning process were reflected in their students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE. Given the results from the 3 compared schools, they were. This supports using the detailed analysis of the nature of change in individual School 2 students’ perceptions in a discussion of the plausible pathways from the teachers’ collective learning process to students’ improved sense of school trust.

In conclusion, we have shown that different levels of teacher-perceived quality and attainment in a 2-year collective learning process may be reflected in students’ perceptions of relational qualities of education. We see this result encourages a continued use of students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE as a means for monitoring teachers’ relational improvement efforts. The article further contributed by providing evidence of associations between student perceived TSR-quality and SSE. In continuation of this, we suggest that a possible combined measure of students’ “School trust” is appropriate for future examination. The findings provide a clear basis for more studies. Swedish students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE need further exploration and further comparison to international findings. Not least, a similar but larger longitudinal study would be of great value, and preferably include students’ achievement trajectories. In doing so, this would enable the exploration of the full systemic school development model illustrated in .

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 High score on TSR2 means a low level of conflict, since all items on this scale are reverse coded.

References

- Allodi, M. W. (2013). Simple-minded accountability measures create failing schools in disadvantaged contexts: A case study of a Swedish junior high school. Policy Futures in Education, 11(4), 331–363. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2013.11.4.331

- Ashan, S., & Smith, W. C. (2016). Facilitating student learning: A comparison of classroom and accountability assessment. In W. C. Smith (Ed.), The global testing culture. Shaping education policy, perceptions, and practice (pp. 131–151). Symposium Books.

- Baker, J. A., Grant, S., & Morlock, L. (2008). The teacher-student relationship as a developmental context for children with internalizing or externalizing Behavior problems. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.23.1.3

- Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Six theories of child development (pp. 1–60). JAI Press.

- Bandura, A. (1990). Multidimensional Scales of Perceived Self-Efficacy. Stanford University.

- Biesta, G. (2010a). Good education in an age of measurement. Ethics, politics, democracy. 1st ed. Paradigm Publishers.

- Biesta, G. (2010b). Pragmatism and the philosophical foundations of mixed methods research. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Mixed methods in social & behavioral science (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 95–118). Sage.

- Bingham, C., & Sidorkin, A. M. (Eds.). (2004). No education without relation. Peter Lang.

- Clark, T., & Goddard, R. (2016). A school staff opinion survey predicts student achievement in Victoria, Australia. Evidence from a Structural Equation Modeling analysis. Paper presented at the SREE Spring Conference, Washington, DC.

- Croninger, R. G., & Lee, V. E. (2001). Social capital and dropping out of high school: Benefits to at-risk students of teachers’ support and guidance. Teachers College Record, 103(4), 548–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/0161-4681.00127

- Doğan, S., & Adams, A. (2018). Effect of professional learning communities on teachers and students: Reporting updated results and raising questions about research design. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 29(4), 634–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1500921

- Fertman, C. I., & Primack, B. A. (2009). Elementary student self efficacy scale. Development and validation focused on student learning, peer relations, and resisting drug use. Journal of Drug Education, 39(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.2190/DE.39.1.b

- Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21(6), 1016–1024. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016

- Goddard, R., Goddard, Y., Kim, E. S., & Miller, R. (2015). A theoretical and empirical analysis of the roles of instructional leadership, teacher collaboration and collective efficacy beliefs in support of student learning. American Journal of Education, 121(4), 501–530. https://doi.org/10.1086/681925

- Hargreaves, A. (1997). Rethinking educational change. In M. Fullan (Ed.), The challenge of school change (pp. 3–32). IRI/Skylight.

- Håkansson, J., & Sundberg, D. (2016). Utmärkt skolutveckling. Natur & Kultur.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning – a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

- Henricsson, L., & Rydell, A.-M. (2004). Elementary school children with behavior problems: Teacher-child relations and self-perception. A prospective study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 50(2), 111–138. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2004.0012

- Hopkins, D., Stringfield, S., Harris, A., Stoll, L., & Mackay, T. (2014). School and system improvement: A narrative state-of-the-art review. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(2), 257–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.885452

- Hughes, J. N. (2011). Longitudinal effects of teacher and student perceptions of teacher-student relationship qualities on academic adjustment. Elementary School Journal, 112(1), 38–60. https://doi.org/10.1086/660686

- Hughes, J. N., Wu, J.-Y., Kwok, O.-M., Villarreal, V., & Johnson, A. Y. (2012). Indirect effects of child reports of teacher-student relationship on achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 350–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026339

- Jarl, M., Blossing, U., & Andersson, K. (2017). Att organisera för skolframgång. Strategier för en likvärdig skola. Natur & Kultur.

- Jederlund, U. (2019). Tillit som förutsättning för skolutveckling. En studie av skolutveckling genom kollektivt lärande i arbetslag. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige, 24(3–4), 7–34. https://doi.org/10.15626/pfs24.0304.01

- Jederlund, U. & von Rosen, T. (2021). Teacher-student relationships and students’ self-efficacy beliefs. Rationale, validation and further potential of two instruments. Ph.D. thesis. Preprint.

- Klassen, R. (2010). Confidence to manage learning: The self-efficacy for self-regulated learning of early adolescents with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 33(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/073194871003300102

- Kraft, M. A. (2018). Interpreting effect sizes of Education interventions. Brown University.

- Lee, J.-S. (2012). The effects of the teacher–student relationship and academic press on student engagement and academic performance. International Journal of Educational Research, 53, 330–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.04.006

- Li, Y., Hughes, J. N., Kwok, O., & Hsu, H.-Y. (2012). Evidence of convergent and discriminant validity of child, teacher, and peer reports of teacher–student support. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024481

- Louis, K., & Lee, M. (2016). Teachers’ capacity for organizational learning: The effects of school culture and context. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 27(4), 534–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2016.1189437

- Louis, K., & Murphy, J. (2017). Trust, caring and organizational learning: The leader’s role. Journal of Educational Research, 55(1), 103–126. http://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-07-2016-0077

- Martin, D. P., & Rimm-Kaufman, S. (2015). Do student self-efficacy and teacher-student interaction quality contribute to emotional and social engagement in fifth grade math? Journal of School Psychology, 53(5), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2015.07.001

- Murray, C., Waas, G. A., & Murray, K. M. (2008). Child race and gender as moderators of the association between teacher–child relationships and school adjustment. Psychology in the Schools, 45(6), 562–578. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20324

- Noddings, N. (2005). What does it mean to educate the whole child? Educational Leadership, 63(1), 8–13.

- O’Connor, E., Dearing, E., & Collins, B. (2011). Teacher-child relationship and behavior problem trajectories in elementary school. American Educational Research Journal, 48(1), 120–162. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831210365008

- Owen, S. (2016). Professional learning communities: Building skills, reinvigorating the passion, and nurturing teacher wellbeing and “flourishing” within significantly innovative schooling contexts. Educational Review, 68(4), 403–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2015.1119101

- Pajares, F. (2002). Gender and perceived self-efficacy in self-regulated learning. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_8

- Ramberg, J., Låftman, S. B., Almquist, Y. B., & Modin, B. (2018). School effectiveness and students’ perceptions of teacher caring: A multilevel study. Improving Schools, 22(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480218764693

- Roffey, S. (2012). Pupil wellbeing- teacher wellbeing: Two sides of the same coin? Educational & Child Psychology 29 (4): 9–17.

- Roorda, L., Koomen, H., Spilt, J., & Oort, F. (2011). The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research, 81(4), 493–529. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311421793

- Rudasill, K. M., Reio, T. G., Stipanovic, N., & Taylor, J. E. (2010). A longitudinal study of student–teacher relationship quality, difficult temperament, and risky behavior from childhood to early adolescence. Journal of School Psychology, 48(5), 389–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2010.05.001

- Saft, E. W., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Teachers’ perceptions of their relationships with students: Effects of child age, gender, and ethnicity of teachers and children. School Psychology Quarterly, 16(2), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.16.2.125.18698

- Spilt, J. L., Vervoort, E., & Verschueren, K. (2018). Teacher-child dependency and teacher sensitivity predict engagement of children with attachment problems. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(3), 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000215

- Svensson, E. (2012). Different ranking approaches defining association and agreement measures of paired ordinal data. Statistics in Medicine, 31(26), 3104–3117. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.5382

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Barr, M. (2004). Fostering student learning: The relationship of collective teacher efficacy and student achievement. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 3(3), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760490503706

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, W. (2000). A multidisciplinary analysis of the nature, meaning, and measurement of trust. Review of Educational Research, 70(2), 547–593. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070004547

- Usher, L., & Pajares, F. (2008). Self-efficacy for self-regulated learning. A validation study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 68(3), 443–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164407308475

- Van Maele, D., van Forsyth, P. B., & van Houtte, M. (Eds.). (2014). Trust and school life: The role of trust for learning, teaching, leading, and bridging. Springer Verlag.

- Wentzel, K. R. (2012). Teacher-student relationships and adolescent competence at school. In T. Wubbels, P. den Brok, J. van Tartwijk, & J. Levy (Eds.), Interpersonal relationships in education (pp. 19–36). Sense.

- Weiss, R. (1974). The provisions of social relationships. In Z. Rubin (Ed.), Doing unto others (pp. 17–26). Prentice Hall.

- Woodland, R. H. (2016). PK–12 professional learning communities: An improvement science perspective. American Journal of Evaluation, 37(4), 505–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214016634203

- Weiss, R. (1974). The provisions of social relationships. In Z. Rubin (Ed.), Doing unto others (pp. 17–26). Prentice Hall.

- Wubbels, T., Brekelmans, M., den Brok, P., Wijsman, L., Mainhard, T., & van Tartwijk, J. (2014). Teacher-student relationships and classroom management. In E. T. Emmer, & E. J. Sabornie (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management (pp. 363–386). Routledge.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (1999). Self-efficacy and educational development. In A. Bandura (Ed.), Self-efficacy in changing societies (pp. 202–231). Cambridge University Press.

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1988). Construct validation of a strategy model of student self-regulated learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(3), 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.3.284