ABSTRACT

Research studies have documented the causes of perceived stress in teachers, while less attention has been given to identifying appropriate stress-management strategies. The aim of this article is to provide insight into the strategies for coping with stress that newly qualified primary and lower secondary school teachers with a five-year integrated master’s degree from a Norwegian teacher education institution employ in their daily work after three years in the profession and the characteristics of these strategies. The data material consists of qualitative interviews with 27 teachers. The study shows that the teachers manage stress through: a) openness with and support from colleagues and family, b) shielding and escape, c) learning established stress-coping strategies and d) planning, structuring, and lowering ambitions. The themes are discussed with theoretical concepts of problem-, emotion- and relationship-focused coping strategies. The study discusses the limitations of Norwegian teacher education related to the handling of work stress.

Introduction

According to international research, teachers are one of the occupational groups that experience the most work-related stress (Kyriacou, Citation1987; Stoeber & Rennert, Citation2008). Teacher stress is often defined as the teacher’s experience of unpleasant emotions as a result of expectations and workload (Collie et al., Citation2012; Kyriacou, Citation2001). It has also been shown that teacher stress has a negative effect on both the quality of teaching and students’ engagement (Wong et al., Citation2017).

Teachers who experience a high level of stress over a long period of time, and who do not consider themselves to have sufficient resources to cope with stress, are at risk of burnout, a state of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation and a self-perceived reduced capacity for work (Fives et al., Citation2007; Wong et al., Citation2017). Burnout is a known problem in the teaching profession, as shown in previous studies (e.g., Aloe et al., Citation2014; Bermejo-Toro et al., Citation2016; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Citation2010, Citation2020). International studies have found that a considerable number of newly qualified teachers (NQTs) leave the profession after a short period of time and that this is often due to stress and burnout (Ingersoll et al., Citation2014; Kyriacou & Kunc, Citation2007; Wong et al., Citation2017). This has led to a shortage of teachers in Western countries (Lindqvist et al., Citation2014).

Teacher stress has interested researchers since the late 1970s (Kyriacou, Citation2001). Further research is needed given the ever-increasing incidence of teacher stress and its associated consequences (Herman et al., Citation2020). According to Cancio et al. (Citation2018), most studies have identified stressors in teachers, but few have identified strategies that can help teachers with appropriate stress management. Betoret (Citation2006) and Herman et al. (Citation2018) claimed that teachers with access to coping resources are less likely to report burnout than teachers without such access. The effectiveness of teachers’ stress-management techniques affects their health, well-being, and teaching (Cancio et al., Citation2018). Gustems-Carnicer et al. (Citation2019) found that using problem-focused coping can reduce the number of psychological or behavioural problems, while using avoidance coping strategies focusing on emotions can lead to higher levels of substance abuse. Several studies have also indicated that teacher education has an especial responsibility to prepare teacher students to cope with occupational stress and stress-related challenges (e.g., Braun et al., Citation2020; Cancio et al., Citation2018; Schäfer et al., Citation2020; Väisänen et al., Citation2018). Kebbi and Al-Hroub (Citation2018) also suggested that schools and teachers themselves should develop improved coping strategies and adapt them to different situations. A recent study shows that teachers use versatile strategies, especially emotion-focused coping strategies, to cope with the stress and strain deriving from work (Aulén et al., Citation2021).

The aim of this article is to provide insight into the characteristics of the strategies for coping with stress employed by NQTs with a master’s degree in Norway. Norwegian NQTs followed a pilot study programme in the teacher education reform introduced in Norway in 2017. The new programme of study, known as the Master’s Degree in Primary and Lower Secondary Teacher Education, provides subject specialisation and emphasises research-based and development-based knowledge (Ministry of Education Research, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). As such, it represents a professionalisation of both teacher education and the teaching profession. The research question is as follows: What strategies for coping with stress are employed by newly qualified primary and lower secondary school teachers with a master’s degree, and what characterises these strategies? The study can provide valuable insight into how NQTs cope with the stress of their job and what characterises the strategies employed to do so. The contribution is relevant to the discourse on whether teacher education programmes provide sufficient training for teachers to manage what is a stressful profession. The study also provides knowledge about how schools can support NQTs in coping with stress at the start of their careers.

The article first presents the following key theoretical concepts: problem-focused and emotion-focused coping (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984) and relationship-focused coping (Stephenson et al., Citation2016). These concepts were chosen following the analysis of the data material because they correspond to the findings in this study and are a suitable basis for exploring and discussing the results. In our approach, we will not assess the quality of the coping strategies; we will only describe and explain the strategies of the NQTs in line with Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) and Stephenson et al. (Citation2016). In the methodology section, we describe the study’s context, sample, data generation, and analysis method. We then present the findings. Later, we discuss the findings, theoretical and practical implications, limitations and future research before the conclusion.

Theoretical Background

Stress is a complex concept (Thiel & Dretsch, Citation2011). The following three theoretical approaches have mainly dominated studies of work-related stress: a) stimulus-oriented stress theories, where stress is understood as a stimulus in the environment that constitutes a physical or mental challenge for the person, termed a stressor; b) response-oriented stress theories, where stress is perceived as a response that focuses on the reaction people have to a stressor, which can be of both a mental and a physical nature and c) transactional stress theories, which describe stress as a process that includes the stressor and reaction concept but also the individual’s relationship to the environment by focusing on the individual’s perception, assessment and action in connection with potential stressors (Cox & Ferguson, Citation1991; Lazarus, Citation2006). In our study of how NQTs cope with stress, the emphasis is placed on the transactional theoretical perspective, as described by Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984). In accordance with this theoretical approach, stress is defined as the individual’s subjective judgement of the imbalance between the external demands and their resources to manage them. Stress is triggered when the dynamic interaction between the individual and the environment causes the individual to experience a real or perceived discrepancy between the demands of the situation and their biological, mental and/or social resources to deal with the situation (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). The capacity to manage stress and the coping mechanisms employed vary from individual to individual. Consequently, people experiencing the same external load can have very divergent experiences of stress depending on both their personal and externally available resources (Lazarus, Citation1993).

Coping can be understood as the ability to deal with stressful events (Lazarus, Citation2006). Coping can be defined as “constantly changing cognitive and/or behavioural efforts to manage specific external and internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person” (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984, p. 141). Based on this definition, coping is further understood as cognitive and behavioural responses to dealing with stressful situations. Coping with stress alludes to the internal mental and/or behavioural responses to external loads, threats, losses and challenges (Bru, Citation2019). Coping is also described as a set of strategies (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). According to Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984), coping strategies are constantly changing based on the demands of the situation and, as a result, of the coping strategies’ effect on the situation. Coping is thus a process and not solely a result of individual personal traits or the characteristics of the situation. Coping constitutes the thoughts and behaviours employed to try to deal with a stressful event. Whether or not they actually help the person is of secondary importance. Lazarus and Folkman’s definition of coping makes an important distinction between coping and automatic responses. Coping is limited to demands that exceed a person’s resources and require mobilisation. By assuming that coping entails efforts to manage demands, the authors avoid equating coping with mastery of the situation. This means that, according to Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984), coping includes active ways of dealing with a situation on a par with more passive strategies, such as avoidance.

According to Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984), coping requires different resources, which they divide into six main categories of health and energy, positive attitude, problem-solving ability, social skills, social support and material resources. They also argue that coping is a result of learned strategies. A person’s way of coping with stress is learned early. This early learned response will tend to remain the preferred coping strategy throughout life as long as this strategy is not challenged.

The literature sheds light on a number of different coping strategies (e.g., Skinner et al., Citation2003). A key pair of concepts is Lazarus and Folkman’s (Citation1984) distinction between problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies. According to Skinner et al. (Citation2003), this two-dimensional distinction is the most common way of categorising coping strategies. In addition, we have chosen relationship-focused coping (Stephenson et al., Citation2016) because this concept, together with the concept pair of Lazarus and Folkman, corresponds with the findings in this study.

Problem-focused coping refers to techniques that focus on solving problems. The strategy is aimed directly at the person-situation relationship, where the intention is to take a proactive, problem-oriented approach to specifically reducing or circumnavigating the underlying cause of the stress. Making plans, changing environmental conditions, and seeking practical help from others are all examples of problem-focused coping. They can also be personal actions, such as lowering one’s ambitions, acquiring knowledge, and improving existing skills or learning new ones (Lazarus, Citation2006).

Emotion-focused coping refers to the behavioural and cognitive strategies employed to change or avoid negative emotions that arise in a stressful situation (Lazarus, Citation2006). Emotion-focused coping can be considered a more passive strategy aimed at avoiding, evading, or escaping uncomfortable situations or problems. This strategy does not change the cause of the stress but regulates an individual’s emotional response to the issue causing the stress (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). Emotion-focused coping, is used when the problem seems impossible to solve or when the circumstances cannot be changed (Aulén et al., Citation2021). Examples of emotion-focused coping are exercising, taking a bath, reading a book, or crying. Emotionally oriented coping strategies can also take the form of denial, or substance use or medication, which are also known strategies for curbing stress (Kristoffersen, Citation2005).

Both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies are used to deal with loads that can cause stress. Emotion-focused strategies are most suitable when it is not possible to change or remove the source of stress (Bru, Citation2019). Meanwhile, Auerbach (Citation1989) considered the problem-focused strategy to be most suited to managing perceived stress over time. However, it is important to have a varied repertoire of strategies as well as the ability to use them flexibly (Taylor, Citation1991).

In the research literature, sharing problems with others has also been identified as a valuable coping strategy for teachers (Feltoe et al., Citation2016; Kyriacou, Citation1981, Citation2001; Kyriacou & Pratt, Citation1985). Stephenson et al. (Citation2016) drew attention to relationship-focused coping, which entails creating good personal relationships and maintaining these during periods of stress. Good relationships with colleagues can provide social support and empathy and help one to think more constructively when dealing with challenging situations (Cohen & Wills, Citation1985). Stephenson et al. (Citation2016) emphasised that relationships can counteract the feeling of being alone in dealing with stressors. Uchino (Citation2009) also highlighted how support from others can act as a mental health resource when negative and challenging situations arise.

Methods

Context of the Study

The present study is part of RELEMAST, a longitudinal research project to examine the experiences of newly qualified primary and lower secondary school teachers with a five-year integrated master’s degree. In 2010, a pilot version of an integrated, profession-oriented, and research-based five-year master’s degree programme in teacher education for primary school teachers and for teachers in years 5–10 was initiated at UiT The Arctic University of Norway. This national pilot scheme (called Pilot in the North) formed the basis for the further development of the national teacher education programmes in Norway adjusted to the educational system for grades 1–7 and 5–10. The new school teacher education programmes focus on research and development work combined with subject and didactic specialisation in three or four teaching subjects. The curriculum lacks any expressive learning outcomes related to coping and stress-management strategies in the teaching profession (Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2016a, Citation2016b).

Sample and Data Generation

The study sample initially consisted of 46 teachers who had completed a master’s degree in primary and secondary school teacher education in 2015, 2016, or 2017 at UiT. Due to maternity leave, changes of profession, or withdrawal from the study, the sample for this study finally comprised 27 teachers who had been working in the profession for three years. The teachers will be referred to by numbers, such as T1 (teacher number 1). Seven women were teaching grades 1–7 (1–7), while 10 women and 10 men were teaching grades 5–10 (5–10). The teachers worked in different parts of Norway.

The study is based on a purposive sample of informants who were selected because their qualifications were relevant to the research question (Silverman, Citation2013). The sample was not based on any other criteria. The sample arose as a result of self-selection following a written invitation to all student teachers who submitted their master’s thesis in 2015, 2016, or 2017. The information provided to the student teachers included a detailed description of the study. Written consent to participate was obtained from all participants.

The study has a qualitative approach and is framed within a constructivist research paradigm where knowledge is constructed in the interface between researchers and informants (Crotty, Citation1998). We collected data by means of semi-structured research interviews (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009). The interviews took the form of thematic, focused conversations structured by an interview guide with the following themes: position and competence, use of R&D competence, professional learning and professional identity, communication and relationships and challenges in daily life. We started by asking the following questions about challenges and stress at work: 1) what do you find most challenging about working as a teacher? and 2) how do you deal with challenges such as stress in daily life? (self-help/colleagues/management/others). The theme was also followed up based on the informants’ answers to the questions. Some of the informants’ answers related to other themes that were also relevant to the research question in this article. The flexibility of the guide enabled us to capture aspects and ask follow-up questions we had not thought of before the interview (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009). The interviews lasted for approximately one hour, and audio recordings were transcribed by research assistants. Efforts were made to transcribe the teachers’ words as accurately as possible. The interviews were conducted either at the teachers’ workplace, at the university, by telephone, or via a digital platform.

Analysis

The data analysis was carried out following Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019, p. 848) approach to thematic analysis (TA), which they include in and prefer to call reflexive TA (RTA). In RTA, the researchers have an active role in the knowledge production process through their reflexive engagement with theory, data and interpretation (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019, Citation2020).

We chose RTA because this approach is theoretically flexible, and it suits questions related to people’s experiences, views and perceptions (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). Braun and Clarke (Citation2006, Citation2020) described a six-phase process for analysis which we have used in our analysis process. Although the phases are sequential, where each phase is based on the previous one, the analysis has been a recursive process, with movement back and forth amongst the phases. We do not interpret the phase approach as a rule that must be followed exactly, but rather as a tool that guides the analysis process as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2020).

Phase 1: Data Familiarisation and Writing Familiarisation Notes

First, the first author read the transcripts as we considered it important to read the entire dataset before coding and looking for patterns. At this stage, the first author took notes that were discussed in relation to the research question. We did not start coding at this stage.

Phase 2: Systematic Data Coding

Using text search in NVivo, the first and second authors selected all text sequences that were relevant to the purpose of the study and the research question. We started generating concise codes. The coding was data-driven (inductive), as shown in . At this stage, we coded as many potential codes as possible. After encoding all the data, the first author identified similar codes and saved them in a word document.

Table 1. Example of Coding from Transcripts (Phase 2).

Phase 3: Generating Initial Themes from Coded and Collated Data

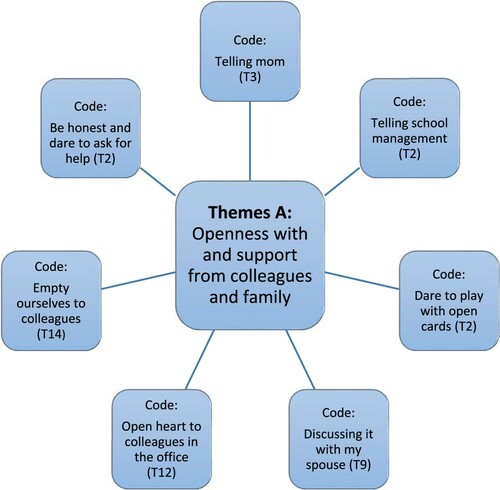

Here, the first author examined the codes and sorted data to identify significantly broader opinion patterns and potential topics. In this phase, the codes were sorted using mind maps (). At the end of this phase, there was a collection of themes.

Phase 4: Developing and Reviewing Themes

At this stage, the first and second authors collaborated to investigate the candidate topics to determine whether they answered the research question. In this phase, several themes were merged into one theme and some were rejected. The goal was to get all the data to fit into a theme and to improve the themes.

Phase 5: Refining, Defining, and Naming Themes

In this phase, the authors identified each theme to assess whether or not the themes contained sub-themes. We concluded that we had four main themes. The first author suggested an informative name for each topic. The analysis resulted in the following four themes: a) openness with and support from colleagues and family, b) shielding and escape, c) learning established stress-coping strategies and d) planning, structuring and lowering ambitions.

Phase 6: Writing the Report

In the last phase, we collaborated to provide sufficient evidence for each topic using quotes from the data as well as contextualising the analysis in relation to existing literature.

Findings

Four themes on strategies for coping with stress were prominent in the data material, as follows: a) openness with and support from colleagues and family, b) shielding and escape, c) learning established stress-coping strategies, and d) planning, structuring, and lowering ambitions. Strategy “a” is consistent with Stephenson et al.’s (Citation2016) description of relationship-focused coping. Two of these strategies, “b” and “c”, are emotion-focused coping strategies, and “d” is a problem-focused coping strategy, as theorised by Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984). displays the distribution of NQTs amongst the themes. Some informants are included in more than one theme .

Table 2. Themes, Informants and Interpretation.

Coping Strategy A: Openness with and Support from Colleagues and Family

The NQTs said that there were tasks and challenges in daily life that they had a need to tell others about. They described how they talked about and were open about the stress of their work to their close contacts, such as colleagues, friends, or family members, as reflected in the quotes below.

T 3 (1–7): Both colleagues and the school management and my mother. These are the ones I actually use.

T10 (5–10): I think I talk about it [stress] a lot. I’m the type of person who talks about what’s on my mind and shares it with others and asks for advice. And if I don’t ask for advice from those in my office, I ask the management, or someone at another school, or my partner. Talk about it at home a bit.

T2 (5–10): I think it’s about putting all your cards on the table, being honest, and to dare to ask for help.

Coping Strategy B: Shielding and Escape

The NQTs talked about the need to shelter and create time or space that acts as a refuge from work. Several said that they actively prioritised leisure activities even on hectic days. Having work-free periods, evenings, or weekends, and not taking work home or thinking about work at home was also a strategy and is reflected in the quotes below.

T25 (1–7): You learn not to let it affect you, and I think now I’ll go home and leave my mobile and iPad at work. And I won’t think about work at home. And I’ve managed to do that in recent years, and it’s been great.

T11 (5–10): When you asked me how I got back to work, it mostly relates to my ability to handle stress. So, it is about prioritising and shielding.

T12 (1–7): When it was at its worst, the ski slopes were my refuge, really, and football. Just doing other things even when you don’t have time. I have to switch off. I do things that I thoroughly enjoy, and it works well for me.

Coping Strategy C: Learning Established Stress-coping Strategies

Some of the NQTs described how they had learned strategies for coping with stress, such as mindfulness or yoga, and reflected on this, as follows:

T18 (5–10): I started listening to mindfulness audiobooks, so I’ve learned to breathe. It’s made all the difference – learning to be calmer and more aware of putting the stress aside. Yeah, its two weeks until the mid-year assessment needs to be completed, but it doesn’t help if I’m sitting here stressing while I’m writing. So, it’s about that awareness.

T14 (5–10): The year would pass without me realising that it’s all getting a bit too much. So, I started doing yoga and lots of other things to do with mental training and learning to live a bit more in the present. Because if you’re stressed, you walk fast in the corridors … The students notice all those things. So, I plan to start the autumn with this [yoga and mindfulness].

T13 (5–10): I think that all NQTs should really have such a course [stress-management course] because you learn to stand up for yourself.

Coping Strategy D: Planning, Structuring, and Lowering Ambitions

A group of NQTs found that planning, structuring and lowering ambitions helped them to manage stress at work. Being able to control the work tasks, to get through the work to prevent it from piling up and to lower ambitions were described as important, as exemplified in the following quotes:

T37 (1–7): You have ten hours of unrestricted time, and in those hours you must work. But, at the same time, you have to work a little with yourself to accept that every teaching plan cannot be as fantastic and perfect […] that you really lower the pressure on yourself.

T1 (5–10): It is a very high tempo. I think I save myself by being structured. I do not like to lose control, so I have a lot to do, and I make lists, and I pick away at it gradually, and I am quite ahead of the subjects and teaching and such because I do not like to fall behind with my tasks.

T4 (5–10): When I have a lot to do, I manage to do everything. I’m very focused on what I need to do first and then continue onto the next task.

Some NQTs searched for functional strategies to take care of themselves and those around them. They tested out various solutions but struggled to carry out their work in the time they had available, as exemplified in the following quote:

T9 (5–10): I need leisure time, and I need to switch off, and I want time at home. I’ve tried different things this year to identify what works best for my family life. I’ve tried to bring work home, and I’ve tried to save the work for a day with evening work. I’ve saved a bit for the weekends and tried different things. I’ve not found exactly what’s best for us.

T16 (5–10): I need to try to cut down on things because I don’t have time to do everything, such as school reports, and I’ve got over 100 students to write reports for since I teach English to three classes. And I can’t end up copy-pasting texts to deliver a report about every student, which isn’t great for any of them.

Discussion

The results show that the NQTs handle stressful situations by employing emotion-focused, problem-focused, and relationship-focused coping strategies. Most of the teachers use the strategies expressed as shielding, escape, and learning established stress-coping strategies, consistent with Lazarus and Folkman’s (Citation1984) description of emotion-focused coping. Using these strategies, the teachers tried to set aside time that could be used to visit friends, walk the dog, play football, and the like. Exercise as a coping strategy has been shown to reduce stress and promote health (e.g., Cohen & Wills, Citation1985; Howard & Johnson, Citation2004).

Another strategy was to learn stress-coping strategies such as yoga and mindfulness, which can be framed within the category of emotion-focused coping (Tharaldsen & Stallard, Citation2019). The teachers used these coping strategies to stay calm in stressful situations. Using approaches that focus on mechanisms such as increased awareness and breathing exercises when faced with an increasing workload, for example, can represent a form of coping and managing everyday stress. Research on teachers has shown that self-regulation of attention can be a protective factor in the relationship amongst stress, ambition, professional burnout (Abenavoli et al., Citation2013). Mindfulness (Baer, Citation2003; Bishop, Citation2002; De Vibe, Citation2008; Kabat-Zinn, Citation1990) and yoga (Hepburn & McMahon, Citation2017) are documented methods for the self-regulation of health and quality of life. An emotion-focused strategy in the form of a break can temporarily re-energise an individual and improve their motivation in the short term but does not solve the long-term problem that causes the stress (Carver et al., Citation1989).

We also find NQTs who employ problem-focused coping strategies in line with the theories of Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984). These teachers seem to be aware of which work tasks and ambitions create stress. They can plan and structure their workday with a realistic ambition of what can be done during working hours and take a proactive approach to solving the problem. Problem-focused strategies for coping with stress entail gaining control by managing and focusing on reducing or modifying the underlying cause of the increased stress level. Our results are consistent with the research by Carver et al. (Citation1989) and Murberg and Bru (Citation2004), who have also shown that planning can reduce stress through taking control, establishing an overview of what needs to be done, and preventing work from piling up.

The study also shows that several teachers employed a relationship-focused coping strategy (Stephenson et al., Citation2016). This strategy entails venting one’s frustrations by being open with and seeking support from colleagues, friends, and family. Use of this strategy is an indication that stress management ends up being the personal responsibility of the teachers, where they seek support from friends and family to offload their frustrations and get advice. Our results are consistent with international studies showing that sharing problems with others is a valuable coping strategy for teachers (Kyriacou, Citation1981, Citation2001; Kyriacou & Pratt, Citation1985). Talking to friends and family is also reinforced by earlier studies that identified social support as an effective method of reducing the impact of stress (e.g., Easthope & Easthope, Citation2007; Yang et al., Citation2009).

Teachers who use emotion-focused and relationship-focused coping strategies do not directly address the challenges that trigger stress; instead, they indirectly try to reduce the stressors. These strategies may be employed because the teachers learned and internalised them early in life. Therefore, teachers who have negative stress and rely on emotion-focused and relationship-focused coping strategies may be at risk of exhaustion and may want to leave the profession. An alternative explanation may be that the teachers find themselves unable to change the workload and work situation in their school.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The theoretical contribution of this study is that, when NQTs lack knowledge about stress coping strategies from their education, they turn to earlier experienced and internalised strategies. The results revealed four stress coping strategies. Some NQTs handle their stress through relationship-focused coping based on openness and the support of their colleagues and family. NQTs also use emotion-focused strategies such as shielding and escape from stress or learn established stress-coping strategies after their education. Some NQTs use problem-focused stress coping strategies with planning, structuring and lowering ambitions for their work as teachers. Also, the NQTs may combine several strategies.

It is paradoxical that extensive research has been conducted on teachers’ stress all the way back to the 1970s but that it is still not a theme addressed in teacher education (Ansley et al., Citation2021). When considering the high staff turnover and burnout rates in the profession, we could expect an extended focus on stress-coping strategies. This lack of prioritisation underscores that coping with stress is still considered the personal responsibility of the teachers. Our study supports the discourse on teacher education programmes’ responsibility for preparing student teachers to manage and cope with the challenges of occupational stress (Bjørndal & Grini, Citation2020; Bru, Citation2019; Lindqvist et al., Citation2020).

None of the teachers in our study reported that they learned about stress-coping strategies in the teacher education programme. This absence is consistent with the programme description (Pilot in the North, Citation2008) and the national framework plan (Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). A few applied specialist knowledge or undertook stress-management training. Considering the nature of the R&D-based curriculum in the new teacher education programme in Norway, we could expect that the NQTs would search for more knowledge-based strategies.

As consequence of The core curriculum (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, Citation2020), and the interdisciplinary theme of public health and life skills in school, students will also be taught about how to master their own lives. Teacher educators are expected to teach students content related to specific themes such as coping strategies, including stress management (Lillejord et al., Citation2017). However, to teach students about stress-coping strategies when the teachers themselves lack knowledge on this topic is not ideal (Madsen, Citation2020). The teachers need to be capable of mastering stress in their own lives to observe and identify such problems in their students. Our study revealed that there is a need to adjust the teacher education curriculum. According to Roland (Citation2019) and Braun et al. (Citation2020), future teachers should have knowledge of different coping strategies to make reflective choices when faced with their own or their students’ stress. Teachers who know what mechanisms create stress and how to prevent stress are more likely to master the complexity of teaching and remain in the teaching profession.

The results of our study have implications for education practices. Teaching has traditionally been understood as an individual responsibility in schools, where teachers must manage their own emotions and relationships (Feiman-Nemser, Citation2012; Jakhelln, Citation2010). In schools with little collaboration and communication between colleagues and management, the individual teacher risks being left to deal with the challenges on their own (Colbert & Wolfe, Citation1992), which can increase their stress. Our results indicate that managers and colleagues should pay more attention to how NQTs are coping and offer advice and support to reduce their work stress. Stress management, and the use of problem-focused coping strategies, should also be incorporated into formal induction programmes and the mentoring of NQTs. For example, peer group mentoring could set stress coping on the agenda as all teachers must cope with a demanding job.

Research Limitations and Future Research

All three authors work at UiT. Bjørndal and Jakhelln teach and supervise in both study programmes and supervised the master’s theses of four informants. Antonsen has no affiliation with teacher education and helped to ensure sufficient distance from the data. The teachers did not have any formal relationship with the researchers at the time of the interviews. During the interviews, the researchers formed the impression that the teachers gave honest answers to the questions and found that they gave both positive and negative feedback on the education programme and the start of their career. The teachers were also motivated to be interviewed so as to contribute to the development of teacher education. Nevertheless, we were aware of the risk of being inadvertently loyal to the informants and failing to take a critical approach to their comments (Silverman, Citation2013).

It may be that the teachers who coped with stress at work did not express this in the interviews as the interview guide contained many questions covering a range of topics. Using interview data has limitations (Desimone, Citation2009), especially when having informants describe personal and emotional experiences such as stress. Individuals may also have their own definitions and conceptions of stress. It may be the case that we did not allow enough time to clarify the concept during the interviews. The fact that we had 27 informants and that several researchers were involved in the analysis and discussion of the findings therefore helped to mitigate the risk of misinterpretations in the analysis. Also, the authors’ joint reflections generally helped to reduce error margins, bias and prejudice.

After three years of practice, the NQTs did not mention any effect of school leadership or mentoring related to their strategies for coping with stress. The lack of emphasis on school leadership or mentoring may be explicable as we did not specifically ask the NQTs about such support for handling stress. Another explanation is that their experience with school leadership or mentoring did not involve thematising coping with stress. Also, only six of ten NQTs in Norway normally are assigned a mentor in their first year (Rambøll, Citation2020).

The interview guide and setting may further explain why none of the informants mentioned any of the undesirable strategies for coping with stress that are documented in international studies, such as drug abuse (e.g., Richards, Citation2012) or religion (e.g., Hussain et al., Citation2019). Another weakness is the lack of other data sources or the use of other methods that could have provided us with additional information. However, researching how individuals cope with stress is challenging; for example, in observation studies, the individuals may camouflage their stress and emotions from others. In relation to external validity, our results can be applied to other samples and similar situations (Stake, Citation1994), and therefore, they do have transfer value (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006).

Design or intervention studies can be developed in teacher education as well as follow-up studies to ascertain whether the teachers actually adopt the learned strategies in service and whether they reduce stress at work. Quantitative studies may follow up whether NQTs’ stress coping strategies have an effect after their formal education. We also suggest developing focus group research or action research over time for investigating NQTs’ use of stress coping strategies. These research strategies can provide the opportunity to establish an environment of psychological safety in which to successfully deal with such a sensitive subject as personal stress. The dialogue amongst the participants over time may give fuller descriptions for understanding how NQTs may use stress coping strategies in different school settings. There is also a need to further investigate how school culture and management can contribute to improving NQTs’ stress management. We also support the position of Skaalvik and Skaalvik (Citation2020) who have argued for further research into the context of schools to reduce stress and promote well-being amongst NQTs.

Conclusion

The aim of the study was to gain insight into the strategies for coping with stress that NQTs with a five-year integrated master’s degree in Norway employ in their daily work and the characteristics of these strategies. The study shows that the NQTs employed four different strategies for coping with stress. One of the strategies was to take a break from work by shielding and escape. Another strategy was to learn and practise coping mechanisms. We understand these two strategies collectively as emotion-focused coping strategies, as theorised by Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984). Another strategy for coping with stress was openness with and support from colleagues and family, which we understand as relationship-focused coping strategies in line with the theories of Stephenson et al. (Citation2016). The last strategy is characterised by planning, structuring and lowering ambitions, where teachers proactively try to complete the tasks that are creating stress or reduce their ambition expectations. This strategy is consistent with Lazarus and Folkman’s (Citation1984) concept of problem-focused coping strategies.

The study shows that the NQTs’ strategies for coping with stress mainly seem to have been learned through personal experiences or by taking stress-management courses after completing their education. The teachers in the study use coping strategies that are probably suitable under some conditions but unsuitable under other conditions. The learned strategies are not necessarily research-based and therefore seem to be individual, internalised coping strategies. Based on our findings, we argue that research, education policy, teacher education programmes, and school practices must consider that the start of one’s career in teaching is extremely stressful. NQTs experience stress differently, and there are also differences between schools’ practices of and skills regarding caring for new employees. Coping experiences in stressful situations give teachers security and confidence in their own abilities to manage the profession and take care of their own well-being to support their students’ learning and the school environment.

Authors’ contributions

KEWB: Conceptualization; KEWB, YA, RJ: Data collection; KEWB: Literature review; KEWB: Analysis phase 1,2,3,4,5,6; YA: Analysis phase 2,4,5,6; RJ: Analysis phase 5,6; KEWB: Methodology; KEWB: Project administration; KEWB: Writing – original draft; KEWB and YA: Co-writing findings and discussion; YA: Review and editing of original draft; RJ: Critical reading and minor editing. All authors have approved the final article.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data sets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to demands for informant anonymity.

Acknowledgements

We thank the informants for their participation, dedication, openness, and critical contributions to the study.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abenavoli, R. M., Jennings, P. A., Harris, A. R., Katz, D. A., Gildea, S. M., & Greenberg, M. T. (2013). The protective effects of mindfulness against burnout among educators. Psychology of Education Review, 37(2), 57–69. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256464666_The_protective_effects_of_mindfulness_against_burnout_among_educators

- Aloe, A. M., Amo, L. C., & Shanahan, M. E. (2014). Classroom management self-efficacy and burnout: A multilevel meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 26(1), 101–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9244-0

- Ansley, B. M., Houchins, D. E., Varjas, K., Roach, A., Patterson, D., & Hendrick, R. (2021). The impact of an online stress intervention on burnout and teacher efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 98, 103251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103251

- Auerbach, S. M. (1989). Stress management and coping research in the health care setting: An overview and methodological commentary. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(3), 388–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.57.3.388

- Aulén, A.-M., Pakarinen, E., Feldt, T., & Lerkkanen, M.-K. (2021). Teacher coping profiles in relation to teacher well-being: A mixed method approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 102, 103323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103323

- Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg015

- Bermejo-Toro, L., Prieto-Ursúa, M., & Hernández, V. (2016). Towards a model of teacher well-being: Personal and job resources involved in teacher burnout and engagement. Educational Psychology, 36(3), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2015.1005006

- Betoret, F. D. (2006). Stressors, self-efficacy, coping resources, and burnout among secondary school teachers in Spain. Educational Psychology, 26(4), 519–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410500342492

- Bishop, S. R. (2002). What do we really know about mindfulness-based stress reduction? Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200201000-00010

- Bjørndal, K. E. W., & Grini, A. R. (2020). Lærerstudenters erfaringer med oppmerksomhetstrening som stressmestringsverktøy. I K.E.W. Bjørndal & V. Bergan (Red.), Skape rom for folkehelse og livsmestring i skole og lærerutdanning (s. 151–178). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Braun, A., Weiss, S., & Kiel, E. (2020). How to cope with stress? The stress-inducing cognitions of teacher trainees and resulting implications for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(2), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2019.1686479

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Bru, E. (2019). Stress og mestring i skolen – en forståelsesmodell. I E. Bru & P. Roland (Red.), stress og mestring i skolen (s. 19–46). Fagbokforlaget.

- Cancio, E. J., Larsen, R., Mathur, S. R., Estes, M. B., John, B., & Chang, M. (2018). Special education teacher stress: Coping strategies. Education and Treatment of Children, 41(4), 457–481. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2018.0025

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

- Colbert, J. A., & Wolfe, D. E. (1992). Surviving in urban schools: A collaborative model for a beginning teacher support system. Journal of Teacher Education, 43(3), 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487192043003005

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2012). School climate and social–emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 1189–1204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029356

- Cox, T., & Ferguson, E. (1991). Individual differences, stress and coping. In C. L. Cooper & R. Payne (Eds.), Personality and stress: Individual differences in the stress process (pp. 7–30). John Wiley & Sons.

- Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. SAGE Publishing.

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140

- De Vibe, M. (2008). Oppmerksomhetstrening (OT) og stressmestring. Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten.

- Easthope, C., & Easthope, G. (2007). Teachers’ stories of change: Stress, care and economic rationality. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 32(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2007v32n1.1

- Feiman-Nemser, S. (2012). Beyond solo teaching. Educational Leadership, 69(8), 10–16. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/beyond-solo-teaching (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286745247_Beyond_solo_teaching)

- Feltoe, G., Beamish, W., & Davies, M. (2016). Secondary school teacher stress and coping: Insights from queensland, Australia. International Journal of Arts & Sciences, 9(2), 597–608. https://www-proquest-com.mime.uit.no/scholarly-journals/secondary-school-teacher-stress-coping-insights/docview/1858849698/se-2?accountid=17260

- Fives, H., Hamman, D., & Olivarez, A. (2007). Does burnout begin with student-teaching? Analyzing efficacy, burnout, and support during the student-teaching semester. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(6), 916–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.03.013

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Gustems-Carnicer, J., Calderón, C., & Calderón-Garrido, D. (2019). Stress, coping strategies and academic achievement in teacher education students. European Journal of Teacher Education, 42(3), 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2019.1576629

- Hepburn, S., & McMahon, M. (2017). Pranayama meditation (yoga breathing) for stress relief: Is it beneficial for teachers? Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 42(9), 142–159. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2017v42n9.9

- Herman, K. C., Hickmon-Rosa, J., & Reinke, W. M. (2018). Empirically derived profiles of teacher stress, burnout, self-efficacy, and coping and associated student outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(2), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717732066

- Herman, K. C., Reinke, W. M., & Eddy, C. L. (2020). Advances in understanding and intervening in teacher stress and coping: The coping-competence-context theory. Journal of School Psychology, 78, 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.01.001

- Howard, S., & Johnson, B. (2004). Resilient teachers: Resisting stress and burnout. Social Psychology of Education, 7(4), 399–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-004-0975-0

- Hussain, S. N., Zulfqar, A., & Aziz, F. (2019). Analyzing stress coping strategies and approaches of school teachers. Pakistan Journal of Education, 36(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.30971/pje.v36i1.1155

- Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., & Stuckey, D. (2014). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force, updated April 2014. CPRE Report (#RR-80). Philadelphia: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

- Jakhelln, R. (2010). Early career teachers’ emotional experiences and development – a Norwegian case study. Professional Development in Education, 37(2), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2010.517399

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. Delta Trade.

- Kebbi, M., & Al-Hroub, A. (2018). Stress and coping strategies used by special education and general classroom teachers. International Journal of Special Education, 33(1), 34–61. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1184086 (https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1184086.pdf)

- Kristoffersen, N. J. (2005). Stress, mestring og endring av livsstil. In J. Kristoffersen, F. Nortvedt, & E. A. Skaug (Red.), Grunnleggende Sykepleie 3 (s. 206–270). Gyldendal.

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). SAGE Publishing.

- Kyriacou, C. (1981). Social support and occupational stress among schoolteachers. Educational Studies, 7(1), 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569810070108

- Kyriacou, C. (1987). Teacher stress and burnout: An international review. Educational Studies, 29(2), 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188870290207

- Kyriacou, C. (2001). Teacher stress: Directions for future research. Educational Review, 53(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910120033628

- Kyriacou, C., & Kunc, R. (2007). Beginning teachers’ expectations of teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(8), 1246–1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.002

- Kyriacou, C., & Pratt, J. (1985). Teacher stress and psychoneurotic symptoms. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 55(1), 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1985.tb02607.x

- Lazarus, R. S. (1993). From psychological stress to the emotions: A history of changing outlooks. Annual Review of Psychology, 44(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.000245

- Lazarus, R. S. (2006). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. Springer Publishing Company, Inc.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. Springer Publishing Company, Inc.

- Lillejord, S., Børte, K., Ruud, E., & Morgan, K. (2017). Stress i skolen – en systematisk kunnskapsoversikt. Kunnskapssenteret for Utdanning.

- Lindqvist, H., Weurlander, M., Wernerson, A., & Thornberg, R. (2020). Talk of teacher burnout among student teachers. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1816576

- Lindqvist, P., Nordänger, U. K., & Carlsson, R. (2014). Teacher attrition the first five years – A multifaceted image. Teaching and Teacher Education, 40, 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.02.005

- Madsen, O. J. (2020). Livsmestring på timeplanen. Rett medisin for elevene? Spartacus.

- Ministry of Education and Research. (2016a). Regulations Relating to the Framework Plan for Primary and Lower Secondary Teacher Education for Years 1–7. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/c454dbe313c1438b9a965e84cec47364/forskrift-om-rammeplan-for-grunnskolelarerutdanning-for-trinn-1-7—engelsk-oversettelse-l1064431.pdf

- Ministry of Education and Research. (2016b). Regulations Relating to the Framework Plan for Primary and Lower Secondary Teacher Education for Years 5–10. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/c454dbe313c1438b9a965e84cec47364/forskrift-om-rammeplan-for-grunnskolelarerutdanning-for-trinn-5-10—engelsk-oversettelse.pdf

- Murberg, T. A., & Bru, E. (2004). School-related stress and psychosomatic symptoms among Norwegian adolescents. School Psychology International, 25(3), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034304046904

- Pilot i Nord. (2008). Profesjonelle lærere på alle trinn: Integrert, differensiert og forskningsbasert lærerutdanning. Universitetet i Tromsø. https://bit.ly/2I02E3A

- Rambøll. (2020). Evaluering av veiledning av nyutdannede nytilsatte lærere [Evaluating mentoring of newly qualified teachers]. Hentet fra https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/tall-og-forskning/rapporter/2020/evaluering-av-veiledning-av-nyutdannede-nytilsatte-larere—delrapport.pdf

- Richards, J. (2012). Teacher stress and coping strategies: A national snapshot. The Educational Forum, 76(3), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2012.682837

- Roland, P. (2019). Stress, stressmestring og klasseldelse. I E. Bru og P. Roland (Red.), Stress og mestring i skolen (s. 197–218). Fagbokforlaget.

- Schäfer, A., Pels, F., & Kleinert, J. (2020). Coping strategies as mediators within the relationship between emotion-regulation and perceived stress in teachers. International Journal of Emotional Education, 12(1), 35–47. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/123456789/55034/4/v12i1p3b.pdf

- Silverman, D. (2013). Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook (4th ed.). SAGE Publishing.

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1059–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.11.001

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2020). Teacher burnout: Relations between dimensions of burnout, perceived school context, job satisfaction and motivation for teaching. A longitudinal study. Teachers and Teaching, 26(7–8), 602–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2021.1913404

- Skinner, E. A., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 216–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216

- Stake, R. (1994). Case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 516–529). SAGE Publishing.

- Stephenson, E., King, D. B., & DeLongis, A. (2016). Coping process. In G. Fink (Ed.), Stress: Concepts, cognition, emotion, and behavior (pp. 73–80). Academic Press.

- Stoeber, J., & Rennert, D. (2008). Perfectionism in school teachers: Relations with stress appraisals, coping styles, and burnout. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 21(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701742461

- Taylor, S. (1991). Health psychology. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Tharaldsen, K. B., & Stallard, P. (2019). Universielle tiltak for å styrke elevers motstandskraft og stressmestring. I E. Bru og P. Roland (Red.), Stress og mestring i skolen (s.73–91). Fagbokforlaget.

- The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2020). The core curriculum. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/?lang=eng

- Thiel, K. J., & Dretsch, M. N. (2011). The basics of the stress response: A historical context and introduction. In C. D. Conrad (Ed.), The handbook of stress: Neuropsychological effects on the brain (pp. 3–28). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118083222.ch1

- Uchino, B. N. (2009). Understanding the links between social support and physical health: A life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(3), 236–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x

- Väisänen, S., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Toom, A., & Soini, T. (2018). Student teachers’ proactive strategies for avoiding study-related burnout during teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(3), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2018.1448777

- Wong, V. W., Ruble, L. A., McGrew, J. H., & Yu, Y. (2017). Too stressed to teach? Teaching quality, student engagement, and IEP outcomes. Exceptional Children, 83(4), 412–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402917690729

- Yang, X., Ge, C., Hu, B., Chi, T., & Wang, L. (2009). Relationship between quality of life and occupational stress among teachers. Public Health, 123(11), 750–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2009.09.018