ABSTRACT

This study investigated primary school special education teachers’ (SETs’) (N = 283) conceptions on their work descriptions and uses of pedagogical documents after a reform in the national support framework. The respondents of this survey reported working mostly in Tiers 1 and 2 when all their tasks (instruction, consultation, and managerial tasks) were considered. The responsibilities of the SETs were, however, more clearly defined in Tier 3. The SETs allocate their work autonomously, but their work description is related to their workload. Clarifications in work descriptions and further elaboration of school’s tiered support functions, emphasizing collaborative practices, are suggested.

A decade ago, the Finnish education system underwent a major reform concerning the provision of special education (Law Citation642/Citation2010). The reasons for the reform were the continuing trend in the increase of students receiving special education and the need to provide more systematic support for all students (Ministry of Education, Citation2007; Thuneberg et al., Citation2014). The reform led to a new organization of the pedagogical support for students in Finnish comprehensive schools, according to a three-tiered model called “Learning and Schooling Support,” which has been viewed as an initiative promoting inclusion in schools (Paju et al., Citation2016; Pesonen et al., Citation2015; Sundqvist et al., Citation2019), since pedagogical support is provided for all students “in a noncategorical fashion” according to their varying needs (Sailor et al., Citation2020, p. 27).

The impacts of the reform on teachers’ work have been increasing collaboration and increasing amounts of paperwork, since the reform introduced renewed pedagogical documents related to systematic planning of the support (Eklund et al., Citation2020; Ekstam et al., Citation2015; Pesonen et al., Citation2015). In this study, we describe special education teachers’ (SETs’) work and time allocation in Finnish primary schools in the tiered support framework, examining whether the resources of part-time special education and school size are related to the work allocation of the SETs in different tiers. Further, we investigate the roles and responsibilities related to the pedagogical documents and the SETs’ opinions of them, also analyzing the relationship between clearly or unclearly defined responsibilities and teachers’ views concerning the pedagogical documents.

In the field of education, Finland is known of a school system that applies no external accountability principles but relies on quality work of autonomous teachers and autonomy of municipalities as education providers. Standards-based testing and evaluation of schools and teachers are lacking (Sahlberg, Citation2010). These features are visible in the differences of Finnish tiered support and the Multitiered Systems of Support (MTSS) programs that are currently widely used in the US, including Response To Intervention (RTI) models (Björn et al., Citation2018; Jahnukainen & Itkonen, Citation2016; Sailor et al., Citation2020). In the core of RTI systems is to monitor each student’s progress by rigorous testing, and if the student’s response to the intervention is low, move them to the next tier to receive more intensive and targeted, evidence-based interventions. The national stipulations concerning the Finnish tiered support system include only recommended pedagogical support methods and guidelines for the documentation of support. The teachers decide for whom, when, how and for how long they use these support methods. In this bottom-up implementation the teachers are supposed to make sense of the meaning of the reform (Thuneberg et al., Citation2014; see also Spillane et al., Citation2002). Organizational capacities and functions affect reform acceptance, successful implementation and the policy’s impact (Castro-Villarreal et al., Citation2014; Regan et al., Citation2015; Thorius & Maxcy, Citation2015), which is why in this article, we have taken the perspective of tasks, responsibilities and resource allocation of SETs.

The respondents of this survey are SETs providing part-time special education. These SETs work with whole general education classes, if not as co-teachers, at least through consultation with the classroom or subject teacher, providing also small-group and individual instruction (Mihajlovic, Citation2020; Sundqvist et al., Citation2019). Before the reform, Finnish SETs have, like their colleagues worldwide, indicated some degree of role ambiguity or lack of clarity in their work descriptions (Garwood et al., Citation2018; Qureshi, Citation2014; Shepherd et al., Citation2016; Takala et al., Citation2009), but the sources of role confusion are scarcely investigated. The RTI frameworks are claimed to hold the potential to clarify the role of SETs (Brownell et al., Citation2010), opening possibilities for early intervention and collaboration with general education teachers, such as planning curriculum modifications and differentiated instruction in general education classes (Leko et al., Citation2015; Shepherd et al., Citation2016; Swanson et al., Citation2012).

Besides instruction and consultative tasks, SETs often have managerial tasks (Mitchell et al., Citation2012), which include handling the matters of students with special educational needs and pedagogical documentation. In some countries, these tasks have been allocated for specific professionals, like Special Educational Needs Coordinators (SENCOs) in Sweden (Göransson et al., Citation2015; Sandström et al., Citation2019) and in the UK and Ireland (Curran & Boddison, Citation2021; Fitzgerald & Radford, Citation2017). General education teachers in Finland also rely on SETs in tiered support processes (Eklund et al., Citation2020), but the consultative and managerial role remains undefined (Sundqvist et al., Citation2014). SETs in Finland struggle with “organisational and practical barriers” in consultative and managerial roles (Sundqvist et al., Citation2014, p. 306; see also Eklund et al., Citation2020; Mihajlovic, Citation2020), such as lack of time allocated for consultative discussions, which is a challenge for the special educators in many countries (Ní Bhroin & King, Citation2020; Beck & DeSutter, Citation2020; von Ahlefeld Nisser, Citation2017). Nevertheless, in Sweden, for example, the mandate for pedagogical consultation has somewhat strengthened over past years, partly due to policy documents that state the mandate (Göransson et al., Citation2015; Sundqvist et al., Citation2014).

Researchers have raised the concern of excessive widening of the work description and workload of SETs in the tiered support framework both in Finland and in the US (Fuchs et al., Citation2012; Jahnukainen & Hautamäki, Citation2015; Shepherd et al., Citation2016; Swanson et al., Citation2012). According to Giangreco et al. (Citation2013), special educator school density is a significant predictor of special educators’ perceptions about whether their work responsibilities are conducive to providing effective special education. Special educator school density is defined as the number of special educators per total school enrollment and used to replace more common “caseload” in the situations where the SET works with whole classes, assessing the needs and providing support also for students not formally found as eligible for special education.

The Finnish Tiered Support Framework and Pedagogical Documentation

In the Finnish Learning and schooling support framework, Tier 1 is called “general support,” to which every student is entitled. The support must meet individual needs in everyday settings. General support consists mainly of differentiation, co-teaching, flexible groupings, and occasional remedial teaching or part-time special education.

In Tier 2, part-time special education becomes more important as well as the intensified use of the above-mentioned methods of support. Tier 2 is called “intensified support,” which is meant for students who need regular support or several forms of support at the same time. Tier 3, “special support,” is intended for students in constant need of special education services. In 2020, 12.2% of the students in Finnish comprehensive school received intensified support and 9.0% received special support (Official Statistics of Finland, Citation2020).

There is no referral to special education in addition to Tier 3 support in the current Finnish system. A student receiving Tier 3 support can be placed in a special education class, where their instruction is provided by a special education classroom teacher (SECT). If a student receives Tier 3 support while studying in a general education class, their special education is usually provided in part-time special education by a SET. Part-time special education has been viewed as a central but resource-lacking form of support in the tiered support model since it is available for students throughout the tiers (Pulkkinen & Jahnukainen, Citation2016). Of Finnish comprehensive school students, 21% received part-time special education regularly during the 2019–2020 school year (Official Statistics of Finland, Citation2020).

The transition from Tier 1 to Tier 2 is made with the help of a pedagogical document called a “pedagogical assessment,” and the content of Tier 2 support is indicated in a learning plan (Finnish National Agency of Education, Citation2014). The assessment is discussed in multi-professional collaboration inside the school. The decision to start Tier 3 support is made by an administrator appointed by the education provider, but the basis for this decision is a document called a “pedagogical statement” assembled by the teachers. The content of Tier 3 support is indicated in an individual education plan (IEP). The collection of information for the pedagogical documents about student’s progress and needs of support is performed in the same way as the student assessment always in Finland: by using diagnostic, formative, performance, and summative assessments (Sahlberg, Citation2010), as well as observations and discussions between the teachers.

Teachers in Finland have had a relatively small amount of obligatory documentation work (Houtsonen et al., Citation2010), and thus pedagogical documentation was the most concrete consequence of the reform for the teachers’ work (Ekstam et al., Citation2015). Teachers have reported an increased amount of paperwork in RTI frameworks in the US as well (Castro-Villarreal et al., Citation2014; Mitchell et al., Citation2012; Swanson et al., Citation2012). In the context of scarce resources, teachers tend to do only what is required of them, interpreting the reform through the actual new tasks that it has brought upon them instead of reflecting new approaches to their work (Pulkkinen, Citation2019; see also Sandström et al., Citation2019). This might be one of the reasons why IEPs are sometimes seen merely as administrative tools rather than instruments of pedagogical planning and student development (Räty et al., Citation2019).

Previous literature reveals that lack of coordination of the responsibilities of SETs and general education teachers in the IEP preparation can lead to incoherence between the planned support and realized instruction of the students with special educational needs (Nilsen, Citation2017). US RTI literature has noted unclear responsibilities which co-occur with inadequate implementation (Gomez-Najarro, Citation2020). In Finland, the National Core Curriculum (Finnish National Agency of Education, Citation2014) stipulates that the responsibilities concerning the preparation of new pedagogical documents must be defined in the municipalities’ and schools’ local curricula. Consequently, SETs in different cities and schools might have different workloads in these processes. It is also possible that the local curriculum, despite the stipulations, does not clearly define these responsibilities. In the survey conducted for comprehensive school and preschool teachers (n = 1,086) in Finland by the Finnish Trade Union of Education (Citation2013) the increased amount of paperwork and undefined responsibilities concerning tasks related to tiered support were noted.

Method

Participants

The current study was an electronic survey that was designed for all the qualified SETs who were delivering part-time special education in Finnish-speaking primary schools (grades 1–6) in Finnish cities with a population over 30,000. Larger municipalities were included because in these cities adoption of the tiered support system has shown to be more advanced (Thuneberg et al., Citation2014). Only primary schools were chosen, because we assumed that definitions of roles and responsibilities would be simpler in primary schools, where the matters of a single student are the concern of the CT and SET, whereas in secondary schools the SETs collaborate with several subject teachers in the matters of a certain student. The invitations to participate in research were sent to 36 cities all over Finland, of which one denied permission. The cover letter and the link to the questionnaire were sent to a special education services coordinator, who then delivered the e-mail to the SETs in September 2016. We received 283 responses.

The return rate was 34%, calculated with following manner. We requested the number of elementary school SETs from administrators of special education services or counted names of SETs on the schools’ websites, ending up as 952 recipients. However, this number included unqualified SETs and we required only the qualified SETs to respond. According to the National Agency of Education (Kumpulainen, Citation2017), 86.7% of the SETs working in Finland in spring 2016 were formally qualified. Using this percentage, 825 of the 952 recipients would have been qualified SETs, 283 responses thus representing 34% of the recipients.

Background information on the respondents shows that 79% of the respondents were female, representing the typical distribution of Finnish SETs and SECTs, 85% of which are female (Kumpulainen, Citation2017). Of the respondents, 37% had 5 years or less teaching experience in special education, while 23% had 16 or more years of experience, and the rest had 6–15 years of experience. The respondents were mostly (60%) teaching in schools of 201–600 pupils, while 18% of them teach in schools with 200 or less students, and similarly 18% have more than 600 students in their schools.

The Questionnaire

Literature was reviewed to develop an understanding of the aspects of the SET role that are relevant to the inquiry (Cole, Citation2005; Kearns, Citation2005; Rosen-Webb, Citation2011). Specifically, the questions concerning work allocation in different tiers were informed by Werts and Carpenter’s (Citation2013) study of roles and responsibilities in RTI settings as well as the knowledge of SETs’ “background work” tasks in addition to instruction (Mitchell et al., Citation2012; Takala et al., Citation2009). The national core curriculum (Finnish National Agency of Education, Citation2014) was especially utilized in the design of the question of the support forms that are emphasized in each tier. The responsibilities concerning pedagogical documents were inquired on the basis of National Core Curriculum and a study concerning Finnish principals’ views of teachers’ roles in tiered support decision making (Pulkkinen & Jahnukainen, Citation2016). Items to the question about opinions of pedagogical documents were drawn from the results of a survey conducted by Trade Union of Education (Citation2013) and the National Core Curriculum. Questions of the person responsible for work allocation of the SET was based on the personal experience of the SET’s work and the realization that this aspect was not covered in the literature. Before larger distribution of the questionnaire, it was piloted with 10 SETs from nine different cities in Finland. Based on their feedback, one question was removed, since the respondents viewed it as confusing and time-consuming, and their feedback revealed that it was not valid for its designed purpose.

The final questionnaire consisted of 7 background information items and 25 questions. In this article, we provide, first, descriptive statistics based on three questions concerning the work description of SETs in the tiered support framework and two questions about the respondents’ role in the decision-making about their time allocation in two questions (see Appendix 1). Second, we provide an analysis of two questions concerning pedagogical documents. One of them inquired about the responsibilities related to the documents. In this question, the respondents chose one from the seven following options concerning the responsibility of each document: classroom teacher, SET, SECT, principal, someone else, not defined or I don’t know.

The other question related to pedagogical documents concerned the opinions on the documents, including 15 items presented in , with Likert-scale response options from 1—completely disagree to 5—completely agree.

The questions not included in the analyses in this article inquired mostly about collaboration with the classroom teachers and the principal, which we intend to use for other purposes, along with questions about the work terms and conditions of the SETs, which are of interest only nationally.

Data Analysis

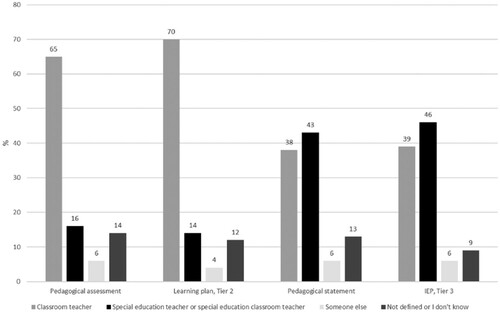

Descriptive statistics are reported to show the work description and time allocation autonomy of the SETs and respondents’ responsibilities and opinions concerning the pedagogical documents. Correlations between school size, workload (number of students in the classes the SET works with) and SETs’ work allocation in different tiers are analysed. To answer the second research question, SETs were divided into two groups concerning each pedagogical document: those who indicated that they knew the person responsible for this document, and those who stated that the responsibilities were not defined or that they did not know about the definitions (see ). Categories “SET” and “SECT” were unified in the analyses and in . Since only one respondent had chosen the option “principal” in only one item (IEP, tier 3), this category was merged with category “someone else” in .

Figure 1. Responsibilities concerning pedagogical documents (N = 283). Note: The responsibilities are presented as percentages %.

Before exploring differences between groups in items concerning SETs’ views on pedagogical documents, a principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted on the 15 items concerning the pedagogical documents for variable reduction. The number of principal components was determined based on an examination of eigenvalues. The analysis revealed four principal components with eigenvalues greater than 1. These four principal components accounted for 58% of the explained variance. The communalities for the items ranged from 0.33 to 0.79. The component correlations ranged from 0.02 to 0.43. The components were rotated using Promax rotation. We labeled components based on item loadings (see Appendix 3). Principal component 1 (Usefulness of pedagogical documents; five items) was defined by items that had the highest loadings and related to the perceived usefulness of the pedagogical documents. The highest loadings in the second principal component (Fluency of pedagogical documentation process) had items related to collaboration and perceptions of the clarity of pedagogical documents. In principal component 3 (Implementation of pedagogical documents; three items), the highest loadings had items related to the implementation of pedagogical documents in SETs’ work. In principal component 4 (Pedagogical documents as administrative tools; three items), the highest loadings had items concerning how pedagogical documents should be drafted for the acquisition of sufficient resources. The independent groups t-test was used to study whether teacher groups differ in their views on pedagogical documents. To explore the differences between the two groups (responsibilities clearly defined or not defined) in their views on pedagogical documents, we used principal component scores. Effect sizes were estimated using Cohen’s d. According to Cohen (Citation1988), the threshold values of d for small, medium, and large effects are 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80.

Results

Work Description of SETs

The resources for part-time special education varied in different cities and schools. We inquired about the total number of students in all classes the SET works with, meaning the number of students whose learning and need for pedagogical support the SET follows with the CTs. This number varied greatly between respondents (, see also Appendix 2), indicating that SETs have different workloads. In some schools there are several SETs, while in others only one, as the definition of “special educator school density” by Giangreco et al. (Citation2013) suggests. SETs’ work, including tasks other than instruction, such as consultation and writing pedagogical documents, concentrates on Tiers 1 and 2, although they also work in Tier 3 (). The proportion of students in different tiers participating in part-time special education also varied greatly () between individual respondents, as the ranges were almost 0–100 in each tier, although the medians revealed that Tier 1 (Mdn = 37.5%) and Tier 2 (Mdn = 40.0%) are mostly represented.

Table 1. Work allocation of special education teachers by tier of support.

The proportion of students from different Tiers attending part-time special education did not depend on the school size (see ). Instead, the workload of the SET (number of students in the classes the SET works with) correlated positively with the proportion of Tier 1 students participating part-time special education (r = .15, p < .005) and negatively with the proportion of Tier 3 students attending part-time special education (r = –.24, p < .001), even though these correlations were weak.

Of the various work forms, consultation seems to be emphasized in all three tiers (). The use of different co-teaching methods is more popular in Tiers 1 and 2, while the significance of small-group teaching and individual teaching grows in Tiers 2 and 3. Nevertheless, 67% of the respondents use small-group teaching already in Tier 1, and 25% of the respondents use individual teaching in Tier 1. Collaboration with other professionals and with students’ parents is emphasized in Tiers 2 and 3 more than in Tier 1.

Table 2. Percentages of respondents (N = 283) using specific work forms in each tier.

The SETs seem to be autonomous in their time allocation. In Finnish schools, the principals are responsible for the allocation of teaching resources in the school and the schedules of the teachers. According to this data, concerning part-time special education, the principals have mostly delegated these tasks to SETs. SETs allocate their resources independently or in collaboration with other teachers, when only 7% reported that the principal makes the decisions about the allocation, and 17% reported that the principal gives recommendations about how part-time special education’s resources should be allocated. The principal prepares the teaching schedules for 7% of the special needs teachers and 20% of them make the schedules in collaboration with the principal—the rest organize their schedules independently or in collaboration with other teachers.

SETs’ Views on Pedagogical Documents

Responsibilities concerning pedagogical documents related to tiered support are defined in the respondents’ local curricula so that as the intensity of support increases, the SETs’ responsibilities increase as well. In the first and second tier, the classroom teachers (CTs) are mostly responsible for the preparation of the documents (). The participants who had responded “someone else” concerning the responsibility of one or more pedagogical document (27 respondents) had clarified their response in an open field, and in all cases, they noted that the documents are prepared in co-operation with the CT and SET, even when the responsibility is assigned to the CT, and sometimes the SET in reality performs this task. In the question concerning the conceptions of the pedagogical documents, the SETs also indicated that the documents have produced new consultation tasks for them. The respondents strongly agreed on the items “It is part of my job to help and advise CTs in making the pedagogical documents” and “I observe that CTs perform their responsibilities related to pedagogical documents on time.” They also considered that pedagogical documents are useful tools in the collaboration between the SET and the CT. However, the respondents found some challenges in finding time to work on the documentation in collaboration with CTs. In the following, we present the results concerning statements on pedagogical documents. For the statements, means and standard deviations, please see .

Table 3. Correlations between special education teachers’ (SETs’) views on pedagogical documents, proportions of students receiving support in different tiers attending part-time special education, school size and SET’s workload.

The pedagogical document forms were viewed as moderately clear and easy to fill in, but there was great variation in participants’ views. In most of the respondents’ schools, there are deadlines for the preparation of the pedagogical documents. The functioning of multiprofessional collaboration at a municipal level related to pedagogical documents was rated functioning moderately (see ).

The SETs strongly agreed on the statements concerning usefulness of the pedagogical documentation for the students and their parents as well as for the collaboration between the SET and the CT and for themselves in planning their work. In addition, they viewed the pedagogical documents as useful to some extent for CTs in planning their teaching, although they stated that the purpose of the pedagogical documents had been understood to a slightly lesser extent in their schools. Concerning the relationship of support resources and pedagogical documentation, the SETs indicated that they write the pedagogical documents realistically, writing down only those forms of support that the school can provide.

Clearly or unclearly defined responsibilities and SETs’ opinions of pedagogical documents. For the purposes of this analysis, the respondents were grouped into two categories concerning each pedagogical document: (a) those who stated that the responsibilities related to the pedagogical document in question were not defined, or who did not know about the definitions, and (b) those who had knowledge about who has official responsibility for completing the pedagogical document in question in their school or city (see ). For the purposes of the comparisons between groups, we conducted a principal component analysis, as described in the methods section. Groups differed only in the second principal component: fluency of the document preparation process. The results suggested that teachers who reported that the responsibility for certain pedagogical documents was not defined in their work viewed this component more negatively (learning plan in Tier 2: t(281) = 2.40, p = .017, d = 0.44; pedagogical statement: t(281) = 2.41, p = .017, d = 0.42; IEP in Tier 3, t(281) = 2.41, p = .016, d = 0.51). Component fluency of the document preparation process included the next statements: “Multiprofessional collaboration needed in preparation of pedagogical documents functions well in my city,” “it is easy for me to arrange time for collaboration to prepare pedagogical documents together with classroom teachers,” “the purpose of the pedagogical documents is well understood in my school,” and “the forms for the pedagogical documents are easy to complete.”

Discussion

In this study, the work description of SETs in a tiered support framework was surveyed. Overall, our results showed that Finnish SETs provide support with various methods in all three tiers. This seems suitable for the idea of tiered support being a model where pedagogical support services are provided on a continuum, according to students’ needs (Rix et al., Citation2015).

Based on this data, the SETs seem to allocate their resources and draft their schedules independently, but some organizational factors, however, affect their work description. The number of students attending part-time special education varied according to the SET’s workload. The reasons for this variation in SETs’ work descriptions were not investigated in this study. Schools may have different profiles in terms of the student population’s needs for support, and the criteria to receive part-time special education or different levels of support might vary. Some cities or schools are moving towards more inclusive service delivery forms and ceasing the special classes. In these cases, the special educational needs of the students are met in part-time special education, and hopefully there would be an adequate special educator school density—meaning less students overall for the SET, so that they can concentrate on supporting Tier 3 students. The ways in which individual schools organize their support functions could be of interest in further investigations in Finland.

The respondents of this survey reported working mostly in Tiers 1 and 2 when all of their tasks (instruction, consultation and managerial tasks) were considered. The CTs are mostly responsible for the preparation of the pedagogical documents related to Tiers 1 and 2, concurring with the findings achieved by Sundqvist et al. (Citation2019) using partially the same questionnaire as we did. However, in this study, the SETs also indicated that they view consulting the CTs in document preparation to be part of their work, and that they also take care of the schedules concerning pedagogical documents in their school. This is in line with the views of Finnish principals (Pulkkinen & Jahnukainen, Citation2016), who viewed that the SETs, along with student’s homeroom teachers, played key roles in Tier 2 pedagogical document drafting. Furthermore, it has been noted that mainstream teachers value SETs’ expertise in matters of students with special educational needs in the tiered support framework (Eklund et al., Citation2020; Paju et al., Citation2016). In our view, SET’s perceptions of their managerial tasks concerning pedagogical documents are notable, since lacking mandate for consultative role of Finnish SETs has previously been indicated (Sundqvist et al., Citation2014).

Sundqvist et al. (Citation2019) concluded that the SET’s role can be considered most explicit in the third tier, while in the first and second tier, their role is more collaborative with the general teachers. Is the collaborative role of SETs in the first and second tier then implicit, “suggested without being directly expressed” (“Implicit,” Citation2021)? Are these implicit tasks noticed when the workload of the SETs is considered? Is their role de facto moving towards that of SENCOs, who have consultative and managerial mandate concerning issues of students with special needs (Curran & Boddison, Citation2021)? If so, the lack of defined status can hinder their effectiveness and cause role confusion (Fitzgerald & Radford, Citation2017; Göransson et al., Citation2015).

In this study, SETs found pedagogical documents as useful tools in documenting the pedagogical support and in collaboration between the SET and the CT, which supports the findings of some previous studies (Ní Bhroin & King, Citation2020; Rotter, Citation2014). Respondents with unclear responsibilities concerning pedagogical documents viewed the preparation process of the documents less fluent than others. Clarity of roles and responsibilities, collaborative practices and understanding the purpose of documentation have been found to be intertwined with the quality of pedagogical documentation and effective use of the documents as pedagogical tools (Hirsh, Citation2015; Nilsen, Citation2017; Ní Bhroin & King, Citation2020; Räty et al., Citation2019).

Limitations

There are at least five limitations that should be considered when attempting to generalize the results. First, SETs working in primary schools in Finnish cities with a population of over 30,000 participated in this study. Hence, the results do not extend to lower-secondary schools or to small municipalities, where the working environment is different. Second, calculating the population of the respondents proved to be difficult, as some city administrators could not provide information on the number of SETs working in part-time special education. Third, the response rate is relatively modest, setting limitations on the generalizability of the results. As the data indicates that the work profile of SETs greatly varies between schools, a larger body of respondents would have revealed exactly how the majority of SETs work in the tiered support system in Finland.

Fourth, a methodological choice was made in order to organize information from the 15 questionnaire items by using principal component analysis. The total variance explained after that was only moderate. Hence, by analyzing separate items, more detailed picture of group differences in SETs’ views could have been achieved.

Fifth, there always lies a possibility of misinterpretations within questionnaires that are more qualitative than quantitative of their nature. However, we used a careful piloting process before disseminating the questionnaire and there were only minor corrections needed at that point.

Conclusions

We found one possible source for the SETs’ reported feelings of role confusion, the contradiction between explicit and implicit tasks. Thus, with our suggestions for policy and practice we concur with Sundqvist et al. (Citation2014), stating that the consultative role of the SETs should be made clearer already in policy documents, and with Paju (Citation2021), noting that collaborative practices are the way to improve the quality of pedagogical support, but these practices should be consciously reflected in the school communities. In Finland, instead of forced top-down implementation policies, the autonomous role of municipalities and schools promote bottom-up implementation of reforms, such as the one discussed in this article. Research on contextualized implementation practices concerning, for example, RTI, have been invited (Thorius & Maxcy, Citation2015). In this sense, the locally varying role of Finnish SETs as autonomous tiered support agents can be of interest for international audience. Nevertheless, this study did not captivate the role of any individual SET, and a challenge for future research would be to examine ways how locally relevant and fit-to-context SET roles are constructed.

Concerning practice, in the name of employee well-being and efficiency of the reform implementation, at least local definitions of the roles and responsibilities in the tiered support processes are recommended (Garwood et al., Citation2018; Gomez-Najarro, Citation2020), for SETs as well as CTs. Clarity of the document forms is also most welcome (Rotter, Citation2014). Nonetheless, these clarifications of roles and tools should not remain as the only changes made to the practice. Fullan (Citation2016) warns about false clarity when change is interpreted in an oversimplified way through literally following guidelines instead of changing beliefs and teaching practices. Thus, we suggest that the focus is turned to the meaning of pedagogical documentation. As the meaning of any educational reform for teachers is best constructed in collaborative working culture (Fullan, Citation2016; Spillane et al., Citation2002) efforts to support teacher collaboration as well as further research on time allocation structures and other barriers for collaboration are needed (Ní Bhroin & King, Citation2020; Beck & DeSutter, Citation2020; von Ahlefeld Nisser, Citation2017).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Beck, S. J, & DeSutter, K. (2020). An examination of group facilitator challenges and problem-solving techniques during IEP team meetings. Teacher Education and Special Education, 43(2), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406419839766

- Björn, P. M., Aro, M. T., Koponen, T. K., Fuchs, L. S., & Fuchs, D. H. (2018). Response-to-intervention in Finland and the United States: Mathematics learning support as an example. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00800

- Brownell, M. T., Sindelar, P. T., Kiely, M. T., & Danielson, L. C. (2010). Special education teacher quality and preparation: Exposing foundations, constructing a new model. Exceptional Children, 76(3), 357–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291007600307

- Castro-Villarreal, F., Rodriguez, B. J., & Moore, S. (2014). Teachers’ perceptions and attitudes about response to intervention (RTI) in their schools: A qualitative analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 40, 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.02.004

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Cole, B. A. (2005). Mission impossible? Special educational needs, inclusion and the re-conceptualization of the role of the SENCO in England and Wales. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 20(3), 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250500156020

- Curran, H., & Boddison, A. (2021). It's the best job in the world, but one of the hardest, loneliest, most misunderstood roles in a school.’ Understanding the complexity of the SENCO role post-SEND reform. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 21(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12497

- Eklund, G., Sundqvist, C., Lindell, M., & Toppinen, H. (2020). A study of Finnish primary school teachers’ experiences of their role and competences by implementing the three-tiered support. European Journal of Special Needs Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1790885

- Ekstam, U., Linnanmäki, K., & Aunio, P. (2015). Educational support for low-performing students in mathematics: The three-tier support model in Finnish lower secondary schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 30(1), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2014.964578

- Finnish National Agency of Education. (2014). Perusopetuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet 2014 [The national core curriculum 2014]. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf

- Fitzgerald, J., & Radford, J. (2017). The SENCO role in post-primary schools in Ireland: Victims or agents of change? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(3), 452–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2017.1295639

- Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., & Compton, D. L. (2012). Smart RTI: A next-generation approach to multilevel prevention. Exceptional Children, 78(3), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291207800301

- Fullan, M. (2016). The NEW meaning of educational change. Teachers College Press.

- Garwood, J. D., Werts, M. G., Varghese, C., & Gosey, L. (2018). Mixed-methods analysis of rural special educators’ role stressors, behavior management, and burnout. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 37(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756870517745270

- Giangreco, M. F., Suter, J. C., & Hurley, S. M. (2013). Revisiting personnel utilization in inclusion-oriented schools. The Journal of Special Education, 47(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466911419015

- Gomez-Najarro, J. (2020). An empty seat at the table: Examining general and special education teacher collaboration in response to intervention. Teacher Education and Special Education, 43(2), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406419850894

- Göransson, K., Lindqvist, G., & Nilholm, C. (2015). Voices of special educators in Sweden: A total-population study. Educational Research, 57(3), 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2015.1056642

- Hirsh, Å. (2015). IDPs at work. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2013.840676

- Houtsonen, J., Czaplicka, M., Lindblad, S., Sohlberg, P., & Sugrue, C. (2010). Welfare state restructuring in education and its national refractions: Finnish, Irish and Swedish teachers’ perceptions of current changes. Current Sociology, 58(4), 597–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392110368000

- Implicit. (2021). In Oxford online dictionary (10th ed.). Retrieved April 6, 2021, from https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/implicit

- Jahnukainen, M., & Hautamäki, J. (2015). Epilogi. In M. Jahnukainen, E. Kontu, H. Thuneberg, & M.-P. Vainikainen (Eds.), Erityisopetuksesta oppimisen ja koulunkäynnin tukeen: Kasvatusalan tutkimuksia 67 [From special education to learning and schooling support: Research in educational sciences 67] (pp. 201–205). The Finnish Educational Research Association.

- Jahnukainen, M., & Itkonen, T. (2016). Tiered intervention: History and trends in Finland and the United States. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 31(1), 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2015.1108042

- Kearns, H. (2005). Exploring the experiential learning of special educational needs coordinators. Journal of In-Service Education, 31(1), 131–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580500200260

- Kumpulainen, T. (Ed.). (2017). Opettajat ja rehtorit Suomessa 2016 (Raportit ja selvitykset 2017:2) [Teachers and principals in Finland 2016. Finnish National Board of Education, reports 2017:2]. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/opettajat_ja_rehtorit_suomessa_2016_0.pdf

- Law 642/2010. Laki perusopetuslain muuttamisesta [Act on the Amendment of the basic education act]. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2010/20100642

- Leko, M., Brownell, M. T., Sindelar, P., & Kiely, M. (2015). Envisioning the future of special education personnel preparation in a standards-based era. Exceptional Children, 82(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402915598782

- Mihajlovic, C. (2020). Special educators’ perceptions of their role in inclusive education: A case study in Finland. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 4(2), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.33902/JPR.2020060179

- Ministry of Education. (2007). Erityisopetuksen strategia (Opetusministeriön työryhmämuistioita ja selvityksiä 2007:47) [Special education strategy. Ministry of Education report 2007:47]. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/79498/tr47.pdf?sequence=1

- Mitchell, B. B., Deshler, D. D., & Ben-Hanania Lenz, B. K. (2012). Examining the role of the special educator in a response to intervention model. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 10(2), 53–74.

- Nilsen, S. (2017). Special education and general education—coordinated or separated? A study of curriculum planning for pupils with special educational needs. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(2), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1193564

- Ní Bhroin, Ó, & King, F. (2020). Teacher education for inclusive education: A framework for developing collaboration for the inclusion of students with support plans. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(1), 38–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2019.1691993

- Official Statistics of Finland. (2020). Special education [e-publication]. Statistics Finland. Retrieved June 30, 2021, from http://www.stat.fi/til/erop/2020/erop_2020_2021-06-08_tie_001_fi.html

- Paju, B. (2021). An expanded conceptual and pedagogical model of inclusive collaborative teaching activities [Doctoral dissertation, University of Helsinki]. Retrieved June 29, 2021, from https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/326432

- Paju, B., Räty, L., Pirttimaa, R., & Kontu, E. (2016). The school staff's perception of their ability to teach special educational needs pupils in inclusive settings in Finland. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(8), 801–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1074731

- Pesonen, H., Itkonen, T., Kontu, E., Kokko, T., Ojala, T., & Pirttimaa, R. (2015). The implementation of new special education legislation in Finland. Educational Policy, 29(1), 162–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904814556754

- Pulkkinen, J. (2019). Reforming policy, changing practices? Special education in Finland after educational reforms [Doctoral dissertation, Finnish Institute for Educational Research, University of Jyväskylä]. Retrieved April 23, 2021, from https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/64018

- Pulkkinen, J., & Jahnukainen, M. (2016). Finnish reform of the funding and provision of special education: The views of principals and municipal education administrators. Educational Review, 68(2), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2015.1060586

- Qureshi, S. (2014). Herding cats or getting heard: The SENCo-teacher dynamic and its impact on teachers’ classroom practice. Support for Learning, 29(3), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12060

- Räty, L., Vehkakoski, T., & Pirttimaa, R. (2019). Documenting pedagogical support measures in Finnish IEPs for students with intellectual disability. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2018.1435011

- Regan, K. S., Berkeley, S. L., Hughes, M., & Brady, K. K. (2015). Understanding practitioner perceptions of responsiveness to intervention. Learning Disability Quarterly, 38(4), 234–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731948715580437

- Rix, J., Sheehy, K., Fletcher-Campbell, F., Crisp, M., & Harper, A. (2015). Moving from a continuum to a community: Reconceptualizing the provision of support. Review of Educational Research, 85(3), 319–352. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654314554209

- Rosen-Webb, S. M. (2011). Nobody tells you how to be a SENCo. British Journal of Special Education, 38(4), 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8578.2011.00524.x

- Rotter, K. (2014). IEP use by general and special education teachers. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014530410

- Sahlberg, P. (2010). Rethinking accountability in a knowledge society. Journal of Educational Change, 11(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-008-9098-2

- Sailor, W., Skrtic, T. M., Cohn, M., & Olmstead, C. (2020). Preparing teacher educators for statewide scale-up of multi-tiered system of support (MTSS). Teacher Education and Special Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406420938035

- Sandström, M., Klang, N., & Lindqvist, G. (2019). Bureaucracies in schools—approaches to support measures in Swedish schools seen in the light of Skrtic’s theories. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1324905

- Shepherd, K. G., Fowler, S., McCormick, J., Wilson, C. L., & Morgan, D. (2016). The search for role clarity: Challenges and implications for special education teacher preparation. Teacher Education and Special Education, 39(2), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406416637904

- Spillane, J., Reiser, B., & Reimer, T. (2002). Policy implementation and cognition: Reframing and refocusing policy implementation research. Review of Educational Research, 72(3), 387–431. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543072003387

- Sundqvist, C., Björk-Åman, C., & Ström, K. (2019). The three-tiered support system and the special education teachers’ role in Swedish-speaking schools in Finland. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(5), 601–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1572094

- Sundqvist, C., von Ahlefeld Nisser, D., & Ström, K. (2014). Consultation in special needs education in Sweden and Finland: A comparative approach. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 29(3), 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2014.908022

- Swanson, E., Solis, M., Ciullo, S., & McKenna, J. W. (2012). Special education teachers’ perceptions and instructional practices in response to intervention implementation. Learning Disability Quarterly, 35(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731948711432510

- Takala, M., Pirttimaa, R., & Törmänen, M. (2009). Inclusive special education: The role of special education teachers in Finland. British Journal of Special Education, 36(3), 162–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8578.2009.00432.x

- Thorius, K. A. K., & Maxcy, B. D. (2015). Critical practice analysis of special education policy: An RTI example. Remedial and Special Education, 36(2), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932514550812

- Thuneberg, H., Hautamäki, J., Ahtiainen, R., Lintuvuori, M., Vainikainen, M.-P., & Hilasvuori, T. (2014). Conceptual change in adopting the nationwide special education strategy in Finland. Journal of Educational Change, 15(1), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-013-9213-x

- Trade Union of Education. (2013). Toteutuuko kolmiportainen tuki? [Is the three-tiered support implemented?] Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B9kepXH6urXpcWFHbkg0U0NsVjA/edit

- von Ahlefeld Nisser, D. (2017). Can collaborative consultation, based on communicative theory, promote an inclusive school culture? Issues in Educational Research, 27(4), 874–891.

- Werts, M. G., & Carpenter, E. S. (2013). Implementation of tasks in RTI. Teacher Education and Special Education, 36(3), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406413495420