ABSTRACT

Understanding how student teacher professional agency (STPA) develops during teacher education is crucial for educators and curriculum developers interested in strengthening it. To explore this process comprehensively, environmental factors (i.e., curriculum coherence between theory and practice and the learning environment) and individual factors (i.e., professional identity) were considered. This study utilized quantitative cross-sectional data of 362 students who were in different stages of their teacher education in a Finnish university. Structural equation modeling (SEM) and network analysis were applied over the data to better understand the interactive processes of the factors being investigated. The results indicated that different aspects of curriculum coherence, learning environment and professional identity dynamically influence STPA during teacher education by changing their relationship with it over time.

1. Introduction

In order to teach increasingly complex contents while providing personalized education (Bransford et al., Citation2005), teachers need to manage proactively their professional skills, so they will be able to adopt (and adapt to) different teaching methods and learning settings. This demand has never been more relevant than in our current society due, for example, to the digitalization of education (Kim et al., Citation2013; Tondeur et al., Citation2019; Voogt et al., Citation2013), increasing demands from educational reforms (Imants & Van der Wal, Citation2020; Vähäsantanen et al., Citation2019), and the needs of pupils with various backgrounds (Powell & Kusuma-Powell, Citation2011).

These fast-paced changes in education request high-quality training for the beginning of teachers’ careers throughout their lifelong journey (Grosemans et al., Citation2015; Kwakman, Citation2003; Kyndt et al., Citation2016). Teacher education should endorse students’ continuous professional development to enable them to cope with work challenges over their careers (Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Imants & Van der Wal, Citation2020; Le Cornu, Citation2009). For that purpose, Heikonen et al. (Citation2020) and Soini et al. (Citation2015) state that fostering student teacher professional agency (STPA) can be a powerful way to support such challenging aims. In the educational context, Soini et al. (Citation2015) believe that student teachers’ active learning must be understood with an integrative concept, such as STPA, or “a student capacity that prepares the way for intentional and responsible management of learning at the individual and community levels” (Soini et al., Citation2015, p. 642).

This study investigates STPA during teacher education in a comprehensive manner, integrating environmental factors (i.e., teacher education curriculum and learning environment) and individual factors (i.e., student construction of their professional identity) in the analysis.

1.1. Student teacher professional agency

According to Soini et al.’s (Citation2015) framework for understanding STPA, four elements have been recognized when student teachers are managing their process of learning oriented to their professional practice. First, teaching competence to leverage the construction of pupils’ understanding and adapt teaching methods according to subject contents and pupils’ needs (Bransford et al., Citation2005). Second, the capacity to create collaborative learning environments, i.e. building up a positive classroom climate by implementing interpersonal skills and engaging pupils in the learning activities (Bronkhorst et al., Citation2011). Third, reflection through meaning-making of teaching situations, evaluating one’s pedagogical practice to improve it, taking the pupils’ growth as a referential goal that demands differential methodologies and continuous learning (Leite et al., Citation2020). Fourth, modeling experienced teachers, analyzing others’ efficient practices, and trying to integrate them into one’s expertise (Brown et al., Citation2015).

These STPA elements are involved when students are taking ownership of their learning during teacher education (Heikonen et al., Citation2020). According to the ecological perspective of STPA, the engagement of actors is a practice that occurs in “temporal-relational contexts-for-action” (Biesta et al., Citation2015, p. 626). Reflecting this perspective, Heikonen et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated that STPA develops during Finnish teacher education in a dynamic matter, in which students’ ability to reflect is consistently associated with learning by modeling and with their capacity to build a collaborative learning environment. Both the abilities to reflect and to model are positively related to students’ teaching competence. These relationships show a tendency to decrease during the second year of teaching education and increase in the third. Such non-linear development calls for further studies to understand how STPA can be nurtured, sustained, and enhanced during teacher education, considering environmental and individual factors that support STPA development.

1.2. Environmental and individual factors regulating student teacher professional agency

Previous research highlights two environmental factors. First, the clear curriculum connection between what is learned in theory and how it can be applied in practice (Jenset et al., Citation2018). Second, the role of the learning environment’s social interactions that students engage in during teacher education (Toom et al., Citation2017). Concerning individual factors, the literature emphasizes how much students are implicated in identifying themselves as teachers (i.e., students’ negotiations of teacher identity) (Arpacı & Bardakçı, Citation2015; Beauchamp & Thomas, Citation2009; Ruohotie-Lyhty & Moate, Citation2016). Therefore, this study analyses how coherence between theory and practice in a teacher education curriculum, learning environment, and students’ professional identity negotiation relate to STPA in different phases of teacher education.

1.2.1. Curriculum coherence between theory and practice

Previous work has already shown how curriculum organization influences teacher education outcomes (Canrinus et al., Citation2017; Hammerness & Klette, Citation2015). Assessment practices, pedagogical methods, well-aligned courses, and training schools are fundamental aspects of teacher education that impact early-career teachers’ practice (Bronkhorst et al., Citation2011; Klette et al., Citation2017). In addition, curriculum coherence supports the transfer of concepts from one context to another, links experiences within and across classrooms and field experiences, and promotes a shared understanding of teaching and teachers’ dispositions for professional development (Canrinus et al., Citation2017; Newmann et al., Citation2001). Bransford et al. (Citation2005) argue that a coherent curriculum supports students in connecting knowledge and skills based on traditional pedagogical practices, while also providing opportunities for students to develop their agency to investigate innovative conceptualizations and practices of teaching. In other words, education curriculum potentially facilitates STPA development toward continuous learning if well organized.

A framework developed by the research team Coherence and Assignments in Teacher Education (CATE-Study) analysed students’ perception of curriculum coherence in Finland, the United States, Norway, Chile, and Cuba (Canrinus et al., Citation2019). According to their framework, curriculum coherence means the extent to which the program meaningfully connects theory to practice through six categories: linking to practice as the opportunities students have to enact teaching actions during coursework (e.g., plan a lesson, rehearse through small group discussions, examine pupil work); using theory as the extent of learning about educational theories, research, and subject matters; research methods as how much students learn to conduct research for investigating educational topics and classroom situations; coherence between courses as how the courses allow building up a progressive understanding over time; coherence between courses and field experiences as the extent to which what students observe in their teaching practices reflects what they learn in the theoretical course; coherence between parts of the program as the opportunities that students have to connect different aspects of the program to develop their own understanding of education (Jenset et al., Citation2019; Klette et al., Citation2017).

This framework has provided insights into how teacher education programs impact the quality of student teachers’ training across cultures (Hammerness & Klette, Citation2015; Klette et al., Citation2017). For instance, when students perceived their program as coherent, they also reported more self-confidence in teaching – which reinforces better teaching practices and future engagement with professional development (Goh & Canrinus, Citation2019).

1.2.2. The learning environment

Although not extensive, there is evidence that the learning environment of teacher education regulates STPA via pedagogical interactions between educators and students (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015; Toom et al., Citation2017). Teacher educators are role models for students. Recognition from them brings empowerment and confidence, especially at the beginning of the program (Turnbull, Citation2005). In addition, peer learning has shown relevance for students in higher education, especially for those with learning challenges (Le Cornu, Citation2009). In sum, students are constantly looking to their educators and peers for support in a reciprocal collaborative learning process (Edwards, Citation2005; Pyhältö et al., Citation2015).

According to Soini et al. (Citation2015), the learning environment can be perceived through four elements: how much support students receive from their educators; how they experience belonging equally to the learning process among their peers; how they share a positive climate for collectively building knowledge; and how they are recognized by their educators. Surprisingly, in their analysis of first-year student teachers, only peer relations (climate) seemed to regulate STPA at this initial stage. The authors called for further studies to understand how the relationships between educators and students develop over time and whether they have a more significant impact on STPA.

1.2.3. Negotiating professional identity

Based on the personal experiences that students bring from their school time, together with the experiences they have during teacher education, student teachers progressively build their professional values, goals, interests, and career plans (Arpacı & Bardakçı, Citation2015; Beauchamp & Thomas, Citation2009; Ruohotie-Lyhty & Moate, Citation2016). The process of students building their professional identity is a continuous negotiation, elaborated over time according to students’ resources and experiences (Edwards & Burns, Citation2016; Taylor, Citation2017; Vähäsantanen et al., Citation2019). Leite et al. (Citation2020) have shown that a relevant part of a teacher’s identity is what teachers believe to be their role in influencing pupils’ personal growth, which in turn demands a disposition to constantly learn about their pupils and participate in their developmental processes. Consequently, how student teachers negotiate their professional identity and consider their role toward lifelong learning must be seen as a fundamental regulator of STPA, which shapes, and is shaped by, it.

Additionally, research has shown that the more connection there is between theory and practice for student teachers, the more realistic their professional identity will be (Ruohotie-Lyhty & Moate, Citation2016), meaning that the students’ expectations of what it is to be a teacher come closer to what they experience during teacher education and to what they will experience when they enter a classroom (Goh & Canrinus, Citation2019). Hence, a realistic professional identity supports students in better integrating their teaching competences, adjusting to school work, and getting involved in continuous learning (Biesta et al., Citation2015; Kwakman, Citation2003; Lohman, Citation2006).

1.3. Research question

The purpose of this study was to investigate STPA at different moments of teacher education, involving environmental factors (i.e., perceived curriculum coherence between theory and practice and learning environment) and individual factors (i.e., student negotiations of professional identity). To this end, the research question was: How do perceptions of curriculum coherence, learning environment, and professional identity correlate to STPA? Based on the previous literature review, we hypothesized that: (H1) students’ perceptions of curriculum coherence, (H2) learning environment, and (H3) teacher identity; all dynamically correlate to and influence STPA in different ways over the years of teacher education.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research context

Finland was chosen to be the context of this research because it was part of the CATE-Studies (Canrinus et al., Citation2019), which found that the Finnish program was one of the least coherent among others, as perceived by their students. This result was attributed to the flexibility that students have to move freely between parts of the program, resulting in more effort to make sense of the connections and less perception of program coherence. Drawing on these studies, we wanted to expand previous investigations of STPA development in Finnish teacher education by taking into consideration students’ perceptions of environmental and individual elements as influencing factors (Heikonen et al., Citation2017, Citation2020; Soini et al., Citation2015; Toom et al., Citation2017).

In Finland, teacher education is provided in public universities. To become a school teacher, students need a master’s degree in educational sciences or in the subject area they will teach. Pre-school teachers need a bachelor’s degree in educational studies. Teaching practice is included in all the pedagogical studies and implemented in the universities’ teacher training schools (Saloviita, Citation2019).

2.2. Participants

The research data were collected in the Fall of 2019 at one Finnish university during class time, with the permission of the teacher educators. A total of 362 students from the first to the last years of the teacher education (TE) programs participated in the data collection. The students were enrolled in different types of programs, including Early Childhood Education, Class Teaching, Subject Teaching, Special Education, and Adult Education. The students’ age ranged from 18 to 51 years (M = 24.04, SD = 4.73) and they included different cohorts in the TE program: 1st year students (n = 60), 2nd year (n = 59), 3rd year (n = 157), 4th year (n = 59), 5th year (n = 19), and 6th year or more (n = 8).

The research followed the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR 2016/679) and the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity guidelines (Kohonen et al., Citation2019). All participants were informed about the research before data collection; their participation was voluntary and informed consent was requested.

2.3. Measures

The four instruments used in this study are conceptually aligned with the overviewed literature and are described below:

Student Teacher Professional Agency in the Classroom scale (STPA) measures students’ agency for continuous professional learning. It contains 20 items organized in four subscales which represent the four interrelated elements recognized when students are engaged in managing their process of learning: sense of competence (COM, five items, α: .84), collaborative environment and transformative practice (CLE, eight items, α: .87), reflection in the classroom (REF, five items, α: .73), and modeling (MOD, two items, α: .70). Students responded on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree).

Teacher Education Coherence scale (TEC)Footnote1 measures students’ perceptions of coherence in their program. It contains 35 items organized in six subscales that represent how the curriculum meaningfully connects theory to practice: linkage to practice (LP, 12 items, α: .88), using theory (UT, 7 items, α: .77), research methods (RM, four items, α: .85), coherence between parts of the program (CPP, five items, α: .77), coherence between courses (CBC, ten items, α: .66), and coherence between courses and field experiences (CCF, four items, α: .59). Students responded on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (none) to 4 (extensive opportunity).

Learning Environment scale (LE) measures the social interactions between teacher educators and students, and among students. It contains 12 items organized in four subscales that represent how the social environment impacts pedagogically on students’ learning process: support (LES, three items, α: .78), equality (LEE, three items, α: .87), climate (LEC, three items, α: .77), and recognition (LER, three items, α: .85). Students responded on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree).

Negotiating Professional Identity scale (NPI) measures how students reflect about their expectations and understanding of their future career. It contains four items covering students’ professional values, goals, interests, and career plans on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). The scale’s alpha value was α = .81.

All measures are validated, reliable according to their (sub)scales’ alpha values, and previously used in Finnish contexts (Canrinus et al., Citation2017; Soini et al., Citation2015; Vähäsantanen et al., Citation2019). Although the TEC scale has a different Likert-scale compared to all other measures, this study adopted a mean item analysis that compatibilized their joint analysis.

2.4. Data analysis

The statistical software SPSS v.25 was used for data screening, descriptive statistics, reliability analysis, and Pearson correlation. Cronbach’s alpha (α) analysis confirmed the scales and subscales’ good internal consistency for reliability. Then, all the subscales’ individual items were transformed into mean items (variables), which are indicated by an “m” in front of their names. Pearson correlation was carried out with the mean items (featured in ). In addition, to compensate some of the discrepancies regarding sample size relative to the number of students by year of education, the students were clustered into three groups: students attending the 1st and 2nd years compounded the Beginning group (n = 119); students in the 3rd and 4th years of education compounded the Intermediate group (n = 218); and those who were studying more than five years compounded the Advanced group (n = 27).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations of mean variables (N = 360).

Next, the statistical software Mplus v.6 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–Citation2010) was used for structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis for two purposes. First, it was important to examine with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) if the latent structure of the measures followed similar patterns as in previous Finnish studies in which it was validated. Second, different models with varied relationships between STPA, teacher education coherence, learning environment, and negotiating professional identity were explored and examined through latent path analysis for the groups of students. In the SEM analysis, STPA, learning environment, and negotiating professional identity were considered to be latent variables (i.e., unobservable factors measured with multiple mean items), while the subscales that measure teacher education coherence were considered to be distinct observed variables (i.e., mean items from the subscales’ transformation). This allowed for more flexibility in the analysis and is in line with students’ consideration that these aspects are independent of each other, although related.

Latent path analysis based on CFA models with latent and observable variables was estimated using MLR and MLM procedures, which produce maximum likelihood estimates with standard errors and χ2 test statistics (p > .05) (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–Citation2010). The estimated standardized models were selected by evaluating their goodness-of-fit indicators: CFI > .95, TLI > .95, RMSEA < .05, SRMR > .05 (Geiser, Citation2013). It is important to notice that, because the Advanced group (students beyond their 5th year of studies) had only 27 students, it was not possible to carry out SEM analysis for them.

Lastly, the statistical software R and its packages, with special relevance to qgraph package (Epskamp et al., Citation2012), were used to implement a network analysis with the purpose of better visualizing the dynamic correlations between all the items. The network models developed for the three groups of students used an iterative process based on the positive and negative correlations of each item of all the scales. Therefore, the patterns of items’ correlations set the placement of the network nodes, computing a layout in which the length of the edges depends on the absolute weight of those edges (i.e., shorter edges for stronger weights) and showing how variables cluster.

This study opted for exploring both SEM and network analysis on cross-sectional data to better understand the interactive processes of the factors being investigated, even though causal temporal relationship of the investigated factors cannot be determined, because they were examined at the same time. The SEM allowed us to specify how observable and latent variables in our model are connected via multiple linear regressions and factor loadings (Geiser, Citation2013) and guaranteed statistical reliability through the goodness-of-fit indicators. The network analysis amplified the possibility of finding interdependencies among all the variables and conceptualized variables’ interrelationships as dynamic and processual systems (Schmittmann et al., Citation2013).

3. Results

The descriptive analysis (, with mean variables = m) suggests that, in general, students from all the years of teacher education have a strong sense of professional agency, with the disposition to reflect in the classroom displaying the highest outcomes (i.e., mREF: M = 6.35, SD = .55) and the sense of competence to orchestrate teaching and learning the lowest (mCOM: M = 4.84, SD = .82). Additionally, students reported that their learning environment afforded them a stronger sense of equality (mLEE: M = 5.96, SD = .96) while they reported less recognition (mLER: M = 5.01, SD = 1.10) from their educators. Regarding curriculum coherence, students reported having experienced all the investigated aspects to some extent, varying from more opportunities to connect ideas between courses and their field practices (mCCF: M = 2.89, SD = .37) to fewer opportunities to learn and apply research methods (mRM: M = 2.12, SD = .71). Finally, students were able to synchronize their teaching values, interests, and career goals with their practice, which represents positive negotiations of professional identity (mNPI: M = 5.62, SD = .84).

Regarding the interrelationship between all the aspects being investigated, significant correlations can be verified among most of the mean variables, with many of these correlations presenting intermediate to strong effect sizes (r over .30). However, only few significant correlations were observed between the elements of program coherence, illustrating that students experience their curriculum as distinct factors. Next, we present the results of the SEM analysis.

3.1. Factors regulating student teacher professional agency

To understand how curriculum coherence, learning environment, and professional identity negotiation influence STPA, CFA and path analysis explored the interrelationships between them.

3.1.1. For new students, negotiating teacher identity prevails

represents the final model with the best goodness of fit and the standardized coefficients of relationships for the students attending the 1st and 2nd years of their program (i.e., Beginning group). In this model, the learning environment and most components of the program coherence were not included because they did not show relevant relation to STPA and did not contribute to a good model fit in the analytical procedures.

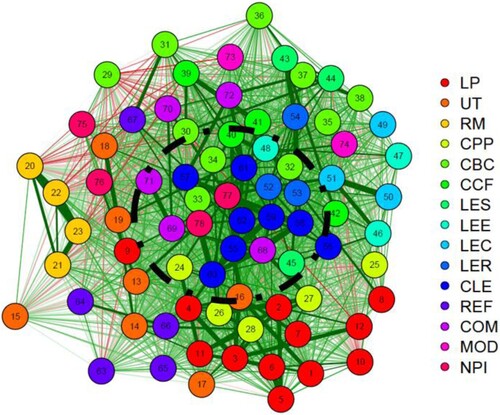

Figure 1. The interrelations between components of STPA, NPI, and TEC for students in the Beginning group [Standardized model: χ2 (32, n = 119) = 40.79, p = .13; CFI/TLI = .97/.96; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .08].

![Figure 1. The interrelations between components of STPA, NPI, and TEC for students in the Beginning group [Standardized model: χ2 (32, n = 119) = 40.79, p = .13; CFI/TLI = .97/.96; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .08].](/cms/asset/2ef10139-5fee-4bfa-85b4-46dc5c1096c9/csje_a_2127879_f0001_ob.jpg)

While all the standardized regression weights of the STPA and negotiating professional identity (NPI) factors’ items are over .5 (p < .01); the factor loadings of NPI, coherence between parts of the program (CPP), and coherence between courses and field experiences (CCF) over STPA are of medium levels and significant. All these factors account for 39% of STPA variance, which is a large effect size. This indicates that students starting teacher education have their professional agency strongly regulated by the construction of their professional identity and how much coherence they perceive between parts of the program, and theoretical courses with field experiences.

3.1.2. For intermediate students, linking theory to practice is fundamental

represents the final model with the best goodness of fit and the standardized coefficients of relationships for the students who were attending the 3rd and 4th years of their program (i.e., Intermediate group). In this model, only linking practice during courses (LP) was included in the analysis because the other components from the curriculum coherence did not show relevant relation to STPA and did not contribute to a good model fit.

Figure 2. The interrelations between components of STPA, NPI, LE, and LP for students in the Intermediate group [Standardized model: χ2 (61, n = 216) = 106.73, p < .00; CFI/TLI = .95/.94; RMSEA = .06; SRMR = .08].

![Figure 2. The interrelations between components of STPA, NPI, LE, and LP for students in the Intermediate group [Standardized model: χ2 (61, n = 216) = 106.73, p < .00; CFI/TLI = .95/.94; RMSEA = .06; SRMR = .08].](/cms/asset/de0734c3-97dd-45b1-8d57-c3169a71db41/csje_a_2127879_f0002_ob.jpg)

All the standardized regression weights of the STPA, learning environment (LE), and negotiating professional identity (NPI) factors, as well as the factor loading of linking theory to practice during courses (LP) over STPA are above .5 (p < .01). The factor loadings of LE and NPI have lower values but are still significant. Additionally, there was a relevant correlation between LE and NPI, which reflects the importance of social interactions with peers and educators for building ones’ own professional identity. All these factors account for 60% of STPA variance. This model indicates that students who are in the middle of their program have their professional agency strongly regulated by the construction of their professional identity, their perceptions of their learning environment, and how much opportunity to enact teaching practice they have.

Next, we analysed the same data with network analysis, and we included the data of the Advanced group of students to have a broader understanding of STPA, considering its relationship with teacher education coherence, learning environment, and negotiating professional identity in the end of teacher education.

3.2. Visualizing student teacher professional agency development

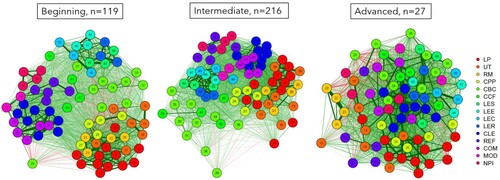

presents the networks generated from the three groups of students (Beginning, Intermediate, and Advanced). It features how all the scales’ items “move” in different times, showing how the items of teacher education coherence (TEC), learning environment (LE), and negotiating professional identity (NPI) spread around each other depending on the strength of their positive or negative relationships. Three clear clusters can be visualized in the Beginning group, while in the Intermediate network the clusters start to intermesh, and, finally, only one global network is seen in the Advanced group. Such dynamics help understanding which items and clusters are strongly related to STPA and which ones have a low impact on it.

Figure 3. The networks generated by all the scales’ items for the three groups of students: Beginning, Intermediate, and Advanced. The nodes represent items and the edges the empirical correlation between items. The numbers in the nodes refer to the order of appearance in the questionnaire. A stronger correlation (positive: green; negative: red) results in a thicker and darker edge. The acronyms in the legend correspond to the subscales featured in .

3.2.1. Starting the journey toward professional agency

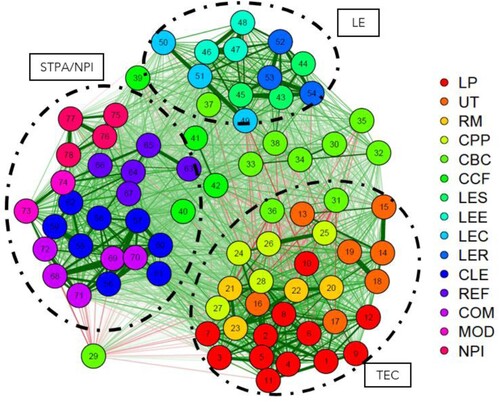

represents the Beginning group network, in which three clusters of items call attention. First, the TEC cluster is characterized by linking practice to courses (LP) items concentrating most of the strongest positive correlations, while the other subscales’ items are spread around the bottom left corner of the network, except the items from the coherence between courses (CBC) and coherence between courses and field experiences (CCF), which are out of the TEC cluster at this stage. Second, the LE cluster is characterized by having the support (LES), recognition (LER), and equality (LEE) items concentrated, while the climate (LEC) items are positioned next to the STPA/NPI cluster. Third, STPA and NPI items are so close to each other that they can be considered one cluster.

Figure 4. The network generated by all the scales’ items for the Beginning group (n = 119), with three clear factors’ clusters: STPA/NPI, TEC, and LE.

Looking at the whole network, it is important to understand the general correlation between items and clusters. NPI and reflecting in the classroom (REF) items are closer to the LE cluster, indicating that students’ reflections about teaching and learning and negotiations of their professional identity correlate to the social interactions with their peers and educators. In addition, the STPA/NPI cluster is positively correlated to the LE and TEC clusters. These results correspond and strengthen the first SEM analysis. For students beginning their education, the sense of professional agency is strongly correlated to negotiating professional identity, which are reinforced by discussions with peers and educators and built upon how much they can connect parts of their program.

3.2.2. Consolidating professional agency

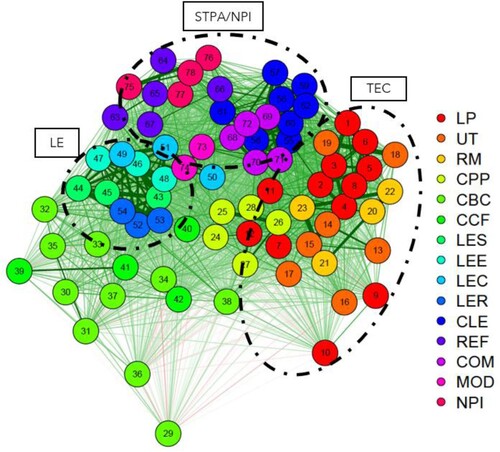

represents the Intermediate group network, in which the three clusters are still clear, but the items are more intermeshed among the original factors.

Figure 5. The network generated by all the scales’ items for the Intermediate group (n = 216), with three clusters still somewhat separated but more intermeshed: STPA/NPI, TEC, and LE.

The TEC cluster changed. Linking practice (LP), using theory (UT), and research methods (RM) items are strongly connected in a chain that ends up in the middle of the global network, “dragged” by the coherence between parts of the program (CPP) items. Again, most of the coherence between courses (CBC) and coherence between courses and field experience (CCF) items are outside of the TEC cluster; this time they are more isolated in the global network.

The learning environment (LE) cluster changed so that the climate (LEC) items are closer to the STPA/NPI cluster and are closely intermeshed with the equality (LEE) items. This indicates that students’ climate and sense of equality among peers relate even more to STPA at this stage.

Lastly, the STPA/NPI cluster has two sides: one concentrating the ability to build collaborative learning environment (CLE) and teaching competence (COM) items and the other gathering NPI and reflection (REF) items. This indicates how STPA unfolds in two different, but cohesive factors at this stage: on one hand, students reflecting about their practice in connection with elaborating their image as a future teacher on an abstract level; on the other, students learning about their teaching competences and roles at a practical level. At this stage, learning by modeling (MOD) items are more isolated and closer to the LE cluster, indicating that students are also modeling their practice through their own perceptions of good climate and equality among peers.

Looking at the whole network, some changes are clear. The TEC and LE clusters are now positively correlated and mediated mostly by coherence between parts of the program (CPP) items. In addition, the STPA/NPI and LE clusters are almost intermeshed now. The collaborative learning environment (CLE) and competence (COM) items have closer relationships with linking practice (LP) and using theory (UT) items. This indicates that these students see more curriculum coherence, are focusing their efforts on connecting theory to practice and with the support of educators and peers to build their sense of professional agency.

These results confirm and expand the corresponding SEM analysis. Students who are in the middle of their teacher education have their sense of professional agency again strongly correlated to their professional identity, with more relevance to their social interactions in the learning environment and how much they can engage in practical teaching roles in their courses.

3.2.3. Becoming a teacher ready for continuous professional development

Finally, represents the items’ relationships in the Advanced group, in which no cluster is distinguishable, and a global network took form with a core agglomeration of certain items surrounded by a peripheral distribution of other ones.

Collaborative learning environment (CLE) items occupy mostly the center, indicating that creating collaborative environments with their pupils and transforming teaching practices according to the classroom situation correlate the most with all other items for students at the final stage of education. CLE is predominantly correlated to the sense of competence (COM), the work-oriented interest (NPI), the perception of recognition from mentors (LER), and the realization of coherence in the study experiences over time (CBC). In addition, most items are positively correlated, strengthening the network connections. Interestingly, applying research methods (RM) still constitutes a clear isolated sub-cluster, which is in a negative relationship with NPI items. This indicates that developing academic research (RM) contrasts with the teaching goals students have for their future work.

4. Discussion

The complementary findings from the two analytical methods revealed that student teachers continuously negotiate their professional identity, perceive the relevance of different aspects of the social environment in different moments, and focus on varied aspects of the curriculum. This culminates with students presenting their STPA with the core ability to flexibly adapt and transform the classroom environment according to their future pupils’ needs, which is essential for entering the labor force as a teacher ready for professional development, as previously indicated by Heikonen et al. (Citation2017).

The results confirmed our first hypothesis, according to which the perception of coherence between theory and practice in the curriculum influences STPA, strengthening students’ competences for professional learning. For students at the beginning of their studies, STPA is regulated by how they experience strong coherence between different parts of their education program and how they connect theories to their initial teaching practices. For students in the middle of the program, practicing teachers’ roles become central for students in developing their actual teaching competences and a more realistic sense of professional agency. At the end of the program, students’ perception of how the curriculum led them to build an overall and in-depth understanding of teaching and learning strongly relates to their ability to construct collaborative learning environments. This finding supports Goh and Canrinus (Citation2019) study according to which students reported higher teaching confidence with a coherent education program, reinforcing their capacity to cope with school-related challenges throughout their careers.

Furthermore, the findings confirmed our second hypothesis, according to which students’ perceptions of support, equity, climate, and recognition differentially related to STPA in different times. At the beginning of the program, a positive climate among peers correlates positively to STPA. In the middle of the program, STPA is regulated by the general learning environment, specially by a good climate and equality among peers. At the end of the program, students’ perceptions of their mentors’ recognition correlate the most to STPA factors. This finding advances the study of Soini et al. (Citation2015), because the learning environment, as a latent construct in SEM analysis, only becomes a relevant factor influencing STPA in more advanced years of teacher education, which were missing in the previous study.

Finally, different aspects of negotiating teacher identity have varying relevance on STPA over time, confirming our third hypothesis and attesting Vähäsantanen’s et al. (Citation2019) findings. When students are in the beginning and middle of their education, STPA is largely regulated by how much they believe their professional identity will align with their future working conditions and practices. More specifically, identity negotiation was intricately connected to students’ reflections, which can be interpreted as students building up their image of what is at stake to become a teacher, what values this implies, and what career paths they can build. Such correlations continued until the end of the degree program, when practical concerns about advancing on the career path and focusing on their interests were more central.

The main contribution of this study is expanding the understanding of how STPA develops during teacher education and how it is investigated in its “temporal-relational contexts-for-action” (Biesta et al., Citation2015, p. 626). Previous research has addressed either the contextual aspects of STPA (Soini et al., Citation2015), or individual factors that regulate it (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2015), or even its temporal development (Heikonen et al., Citation2020); but not all simultaneously – which was done in this study. Such comprehensive approach can better support teacher educators and curriculum developers to understand how particular experiences allocated at different stages of the program can better nurture STPA over time.

For instance, we unfolded that in the program under study, when students are starting their education, the most relevant experiences to nurture STPA are the opportunity to clearly visualize how pedagogical theories are connected to teaching practice, to enjoy a positive climate among peers, and to reflect about their personal values and beliefs about what is to be a teacher. Complementarily, teacher educators could open communication channels or mentor study/research groups in which students perceive educators as accessible and available for support and recognition (Le Fevre, Citation2011).

Later in the program, applying teaching theories and rehearsing teaching tasks become central for STPA development, together with a continuous positive climate and equality perception among peers, and further elaborations of their goals and interests as a teacher. Supplementarily, the school faculty could emphasize more the connections between the different parts of the program, such as how different courses complement each other for a deeper understanding of teaching and learning (Goh et al., Citation2020). Educators and researchers could also refer to each other projects to help students align their different pedagogical approaches.

At last, when students develop a coherent understanding of what is to teach, have their mentor’s recognition of them becoming professional teachers, and are able to elaborate concretely their teacher career; all of it strengthens STPA. Additionally, courses could emphasize more the role of research, not only for strict academic tasks but also as a competence that teachers need to possess to support their pupils in their daily work (Edwards & Burns, Citation2016; Taylor, Citation2017).

4.1. Limitations and further research

As indicated in the methodological section, the results do not represent a causal temporal relationship of the investigated factors because of the study’s cross-sectional design. In addition, the sample size limits the results’ generalizability power to other education programs. Both limitations do not affect the contribution of the study though, which is to highlight the relevance of investigating environmental and individual factors that influence STPA during teacher education. Such comprehensive approach can better guide designing the curricula and courses’ practices, as well as support aligning experiences across different teacher education programs, scaffolding students to manage their learning process in a meaningful manner that is oriented for continuous professional development.

Lastly, this report does not reveal if the program under study provides “enough” curriculum coherence in alignment with the learning environment and teacher professional identity from a comparative perspective. As pointed out in the descriptive results, only a few elements of the curriculum significantly correlated with each other, which confirms previous international studies showing that Finnish education programs are perceived by students as among the least coherent (Canrinus et al., Citation2017; Canrinus et al., Citation2019).

Since contextual and temporal aspects have such a relevant influence on STPA, comparative and repetitive studies are valuable for this type of investigation. Therefore, we are replicating our analysis – with a broader and more balanced sample size – in a teacher education program with characteristics that contrast from the Finnish context, such as students’ perception of strong curriculum coherence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 A few changes were made in the original TEC subscales. In the LP subscale, the original item 1B was transformed in three distinct items to gather more information about what students practice during their courses. In the UT subscale, two items were added to extract information about how much students read, analyse, and discuss about educational theories related to students with learning difficulties and disabilities. Finally, in the CBC subscale, the original items 3A and 3B were reformulated for clearer definitions of the program vision of education.

References

- Arpacı, D., & Bardakçı, M. (2015). An investigation on the relationship between prospective teachers’ early teacher identity and their need for cognition. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 4(3), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v4i3.1176

- Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640902902252

- Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(6), 624–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

- Bransford, J., Derry, S., Berliner, D., Hammerness, K., & Beckett, K. L. (2005). Theories of learning and their roles in teaching. In L. Darling-Hammond & J. Bransford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 40–87). John Wiley & Sons.

- Bronkhorst, L. H., Meijer, P. C., Koster, B., & Vermunt, J. D. (2011). Fostering meaning-oriented learning and deliberate practice in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(7), 1120–1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.05.008

- Brown, A. L., Lee, J., & Collins, D. (2015). Does student teaching matter? Investigating pre-service teachers’ sense of efficacy and preparedness. Teaching Education, 26(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2014.957666

- Canrinus, E. T., Bergem, O. K., Klette, K., & Hammerness, K. (2017). Coherent teacher education programmes: Taking a student perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 49(3), 313–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2015.1124145

- Canrinus, E. T., Klette, K., & Hammerness, K. (2019). Diversity in coherence: Strengths and opportunities of three programs. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(3), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117737305

- Edwards, A. (2005). Relational agency: Learning to be a resourceful practitioner. International Journal of Educational Research, 43(3), 168–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2006.06.010

- Edwards, E., & Burns, A. (2016). Language teacher-researcher identity negotiation: An ecological perspective. TESOL Quarterly, 50(3), 735–745. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.313

- Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). Qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(4), https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i04

- Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., & Hökkä, P. (2015). How do novice teachers in Finland perceive their professional agency? Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(6), 660–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044327

- Geiser, C. (2013). Data analysis with Mplus (English ed.). Guilford.

- Goh, P. S. C., & Canrinus, E. T. (2019). Preservice teachers' perception of program coherence and its relationship to their teaching efficacy. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 27(T2), 27–45.

- Goh, P. S. C., Canrinus, E. T., & Wong, K. T. (2020). Preservice teachers' perspectives about coherence in their teacher education program. Educational Studies, 46(3), 368–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2019.1584856

- Grosemans, I., Boon, A., Verclairen, C., Dochy, F., & Kyndt, E. (2015). Informal learning of primary school teachers: Considering the role of teaching experience and school culture. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.011

- Hammerness, K., & Klette, K. (2015). Indicators of quality in teacher education: Looking at features of teacher education from an international perspective. International Perspectives on Education and Society, 27(2), 239–277. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-367920140000027013

- Heikonen, L., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Toom, A., & Soini, T. (2017). Early career teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom: Associations with turnover intentions and perceived inadequacy in teacher–student interaction. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 45(3), 250–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2016.1169505

- Heikonen, L., Pietarinen, J., Toom, A., Soini, T., & Pyhältö, K. (2020). The development of student teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom during teacher education. Learning: Research and Practice, 6(2), 114–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2020.1725603

- Imants, J., & Van der Wal, M. M. (2020). A model of teacher agency in professional development and school reform. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 52(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2019.1604809

- Jenset, I. S., Hammerness, K., & Klette, K. (2019). Talk about field placement within campus coursework: Connecting theory and practice in teacher education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(4), 632–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1415968

- Jenset, I. S., Klette, K., & Hammerness, K. (2018). Grounding teacher education in practice around the world: An examination of teacher education coursework in teacher education programs in Finland, Norway, and the United States. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(2), 184–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117728248

- Kim, C. M., Kim, M. K., Lee, C. J., Spector, J. M., & DeMeester, K. (2013). Teacher beliefs and technology integration. Teaching and Teacher Education, 29(1), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.08.005

- Klette, K., Hammerness, K., & Jenset, I. S. (2017). Established and evolving ways of linking to practice in teacher education: Findings from an international study of the enactment of practice in teacher education. Acta Didactica Norge, 11(3), 9. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.4730

- Kohonen, I., Kuula-Luumi, A., & Spoof, S.-K. (Eds.) (2019). The ethical principles of research with human participants and ethical review in the human sciences in Finland. Publications of the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (TENK) 3/2019.

- Kwakman, K. (2003). Factors affecting teachers’ participation in professional learning activities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(2), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00101-4

- Kyndt, E., Gijbels, D., Grosemans, I., & Donche, V. (2016). Teachers’ everyday professional development. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1111–1150. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315627864

- Le Cornu, R. (2009). Building resilience in pre-service teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(5), 717–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.11.016

- Le Fevre, D. M. (2011). Creating and facilitating a teacher education curriculum using preservice teachers’ autobiographical stories. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(4), 779–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.003

- Leite, L. O., Go, W., & Havu-Nuutinen, S. (2020). Exploring the learning process of experienced teachers focused on building positive interactions with pupils. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 0(0), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1833237

- Lohman, M. C. (2006). Factors influencing teachers’ engagement in informal learning activities. Journal of Workplace Learning, 18(3), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620610654577

- Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2010). Mplus users guide (6th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- Newmann, F. M., Smith, B., Allensworth, E., & Bryk, A. S. (2001). School instructional program coherence: Benefits and challenges. Consortium on Chicago school research.

- Powell, W., & Kusuma-Powell, O. (2011). How to teach now: Five keys to personalized learning in the global classroom. ASCD.

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2015). Teachers professional agency and learning – from adaption to active modification in the teacher community. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(7), 811–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.995483

- Ruohotie-Lyhty, M., & Moate, J. (2016). Who and how? Preservice teachers as active agents developing professional identities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 55, 318–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.01.022

- Saloviita, T. (2019). Outcomes of teacher education in Finland: Subject teachers compared with primary teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 45(3), 322–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2019.1599504

- Schmittmann, V. D., Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Epskamp, S., Kievit, R. A., & Borsboom, D. (2013). Deconstructing the construct: A network perspective on psychological phenomena. New Ideas in Psychology, 31(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2011.02.007

- Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., Toom, A., & Pyhältö, K. (2015). What contributes to first-year student teachers sense of professional agency in the classroom? Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(6), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044326

- Taylor, L. A. (2017). How teachers become teacher researchers: Narrative as a tool for teacher identity construction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61, 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.09.008

- Tondeur, J., Scherer, R., Baran, E., Siddiq, F., Valtonen, T., & Sointu, E. (2019). Teacher educators as gatekeepers: Preparing the next generation of teachers for technology integration in education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(3), 1189–1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12748

- Toom, A., Pietarinen, J., Soini, T., & Pyhältö, K. (2017). How does the learning environment in teacher education cultivate first year student teachers’ sense of professional agency in the professional community? Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.12.013

- Turnbull, M. (2005). Student teacher professional agency in the practicum. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 33(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660500122116

- Vähäsantanen, K., Räikkönen, E., Paloniemi, S., Hökkä, P., & Eteläpelto, A. (2019). A novel instrument to measure the multidimensional structure of professional agency. Vocations and Learning, 12(2), 267–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-018-9210-6

- Voogt, J., Erstad, O., Dede, C., & Mishra, P. (2013). Challenges to learning and schooling in the digital networked world of the 21st century. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29(5), 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12029