ABSTRACT

In this systematic scoping review, research on the inclusion of students with special education needs (SEN) in Nordic countries was reviewed to describe the scope and types of empirical research, identify the practices and approaches on the inclusion of students with SEN, and conceptually map how particular concepts (i.e., inclusion, SEN) are referred to by the authors of each study in the empirical literature. Based on a comprehensive literature search of relevant peer-reviewed articles and book chapters in three databases, 135 studies were selected as eligible in line with the a priori defined inclusion criteria. Results highlight that there still is a need to clarify perspectives on inclusion and on who needs support, and quantitative and mixed-method studies on actual practices and student outcomes including students’ perspectives are needed.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) defines inclusive education as the “process of strengthening the capacity of the education system to reach out to all learners” and explains that special education needs (SEN) is “a term used in some countries to refer to children with impairments that are seen as requiring additional support” (UNESCO, Citation2017, p. 7). The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified three main models to define SEN: the medical model (i.e., disability as a feature of the person), the social model (i.e., disability as a socially created problem rather than an attribute of an individual), and a more holistic biopsychosocial model of disability (i.e., disability arises from the mismatch between individuals’ capabilities and environmental requirements) (World Health Organization, Citation2002). In line with the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education (UNESCO, Citation1994) and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD; United Nations, Citation2015), children with SEN should be given the right to be educated in the general educational system and not be excluded because of disabilities. Hence, the inclusion of children with SEN into mainstream schools and classrooms has become an overall international trend (Krämer et al., Citation2021; Ruijs & Peetsma, Citation2009).

Despite consensus on the importance of inclusive education as well as the rights of students with SEN internationally, finding ways of including all children in schools is a major challenge for education around the world (Ainscow, Citation2020). There are great differences in the policies, practices, and approaches to inclusive education, as well as in the understanding and recognition of SEN across countries (Ainscow, Citation2020; Brussino, Citation2020). Reindal (Citation2016) argues that the concept of inclusive education has explored the world without having landed, and efforts of giving it a clear working definition have been elusive. A recent qualitative review of 34 studies in the Nordic countries found that inclusion and inclusive education were seldom defined explicitly and that there were different ways of understanding inclusion (Buli-Holmberg et al., Citation2022). While inclusive education, in some countries, is still considered an approach to serving students with disabilities in the mainstream educational setting (physical placement), internationally, –in its broader term–, it is a basic human right principle supporting diversity and emphasizing equity and fairness to meet students’ various needs (Ainscow, Citation2020).

In this scoping review, we systematically reviewed the empirical research on the inclusion of students with SEN in Nordic countries (i.e., Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) to provide an overview of the scope and types of empirical research, perspectives and understandings of inclusion and SEN, to describe inclusive practices and approaches as they are referred to by the authors in this research, and to identify research gaps in the existing literature.

SEN and inclusive education in Nordic countries

Just as in many other countries around the world, special education (SE) and inclusive policy in the Nordic countries have been influenced by the publication of the Salamanca Statement (UNESCO, Citation1994). This statement emphasizes that education systems must take into account the wide variation in children's characteristics, aptitudes, and needs, and that education must be provided in inclusive environments regardless of the student's physical, intellectual, emotional, and linguistic background as well as regardless of social, cultural, and ethnic background.

UNESCO (Citation2008) emphasizes that inclusion is a process characterized by increasing participation and preventing segregation and alienation. Although the process of inclusion had started before the publication of the Salamanca Statement in most Nordic countries, it has taken some time before the inclusive approach was incorporated in policy and curriculum (e.g., Berhanu, Citation2014; Egelund & Dyssegaard, Citation2019; Ogden, Citation2014; Sundqvist et al., Citation2019).Footnote1

According to the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (EASIE), the criteria for an official decision of SEN are similar across all Nordic countries: There has been an educational assessment procedure involving a multi-disciplinary team that includes members from within and external to the child’s/learner’s school. There is a legal document that describes the support the child/learner is eligible to receive, and which is used as the basis for planning. And finally, the official decision is subject to a formal, regular review process. The data from EASIE in 2016/2017 reports that Sweden has the lowest percentage of primary school students (enrolled in any formal educational setting) who received an official decision of SEN (less than 1%), followed by Denmark (4% in 2014/2015), and Finland and Norway (7%). Iceland has the highest percentage of students with an official decision of SEN (14%), but, together with Norway, also the highest percentage (93%) of these students educated in mainstream groups/classes. Denmark has the lowest percentage of students educated in mainstream groups/classes (6%), followed by Sweden (11%), and Finland (36%).Footnote2

Overall, the practice of inclusive education in Nordic countries initially involved removing the division between special and general education with an egalitarian focus, embracing the ‘one school for all’ concept in the practice as a part of Nordic education model, prevalent in all Nordic countries but in varying degrees. One specific recommended approach to inclusive education is the three-tier model, which has been implemented in Finland since 2010 and has recently been introduced in Norway in 2019 as a framework for structuring and systematizing educational support in various tiers (i.e., general support, intensified support, and special support) in line with the students’ needs (Sundqvist et al., Citation2019). However, the definitions of inclusive education and its practice, including three-tier model approaches, also depend on schools’ perspectives and missions, as well as the attitudes of teachers and other actors (Göransson & Nilholm, Citation2014).

The aim of the current review

Scoping reviews are conducted to scope a body of literature, to explore and identify the breadth and depth of the literature, to identify knowledge gaps, to clarify key concepts and definitions, or to investigate research evidence to inform practice (Moher et al., Citation2015; Munn et al., Citation2018; Peters et al., Citation2020; Tricco et al., Citation2016). By mapping the design and characteristics of empirical studies, scoping reviews can identify gaps in the type of research evidence that is present on a certain topic. If a topic is covered by various research designs and study characteristics, this allows for triangulation of the evidence and a more complete picture of the phenomenon under study. If the scoping review identifies gaps, this can provide direction for which type of research is needed in the future. Scoping reviews are also a helpful methodology when the literature on a topic as well as the concepts are large, complex, and heterogeneous and the aim is not to find out detailed answers to specific questions (Moher et al., Citation2015; Peters et al., Citation2020). For example, in the context of inclusive education, there is a lack of a common understanding of the concept under study. A recent systematic review of reviews on inclusive education suggested the use of an explicit definition of inclusive education in each study conducted to resolve issues concerning the ambiguity of the concept (Van Mieghem et al., Citation2020).

In addition to the differences in the interpretation and implementation of the concept of inclusion, the understanding of SEN and difficulties and disabilities related to SEN of students, are also inconsistent and vary across studies (Lindsay, Citation2007). Moreover, there is a considerable variation in the practices and approaches to inclusive education, not only across countries but even within countries (e.g., Nordahl et al., Citation2018). This makes it difficult for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to get a grip on the research conducted on inclusive education.

A systematic scoping review will provide the necessary overview of the existing research on inclusion, the conceptualization of key aspects, and guide future research by illuminating the gaps where more research is needed. This systematic scoping review focuses on both (a) identifying the practices and approaches on the inclusion of students with SEN and (b) conceptual mapping of how particular concepts (i.e., inclusion, SEN) are referred to by the authors in the empirical literature. To ensure the rigor of our scoping review, we followed the five-stage framework described by Arksey and O’Malley (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005): (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting the studies, (4) charting the data, (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

To sum up, in this systematic scoping review, the aim was to systematically review the empirical research on the inclusion of students with SEN in Nordic countries. More specifically, our research questions were:

What are the characteristics of the empirical studies on the inclusion of students with SEN?

Which perspectives and understandings of inclusion and SEN were referred to by the authors of each study?

Which inclusive pedagogical approaches and practices to include students with SEN were referred to by the authors of each study?

Method

When reporting on this systematic scoping review, we have followed guidelines in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) statement (Moher et al., Citation2009; Peters et al., Citation2020). A protocol was drafted and agreed upon with the research group prior to the start of the review to guide the review process, but not formally registered.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this systematic review were set a priori and these criteria were applied to studies identified as being potentially relevant. Studies with the following characteristics were included: (a) focusing on SEN; (b) having an inclusive education approach; (c) involving samples of basic education students (students at grades 1–13); (d) empirical quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods study; (e) written in English; (f) published in a peer-reviewed journal or as a peer-reviewed book chapter; (g) conducted in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, or Iceland; and (h) published after 2000 to allow research development in the area of inclusion after the publication and adaptation of Salamanca Statement. Hence, exclusion criteria were thus related to topic (i.e., a lack of a focus on SEN and inclusive education approach), target group (i.e., a different target group such as samples constituting early childhood education and care (ECEC), or higher education), study type (i.e., theoretical and conceptual articles or other papers not reporting primary empirical research), language (i.e., not written in English), publication type (i.e., textbooks, dissertations, and grey literature), county (i.e., research carried outside of Nordic countries unless as a comparison country) and publication year (i.e., research published before 2000).

Literature search

Following the development of a protocol detailing the search strategy, we conducted a systematic literature search of English language articles and book chapters in November 2020, and the search was conducted in various steps. First, to elaborate search terms to better identify relevant studies, we iteratively developed the keywords by (a) conducting pilot searches in electronic databases, (b) reviewing relevant books, reports, and book chapters on the study topic, and (c) doing ‘text analysis’ of identified relevant studies. After finalizing the search terms, an electronic search was conducted in three databases: EBSCO (ERIC and Academic Search Premier), OVID (PsycInfo), and SCOPUS. Searches were facilitated using two categories of search terms covering ‘special pedagogy/education’ and ‘inclusive education’. These two categories of search terms were combined by the Boolean operator ‘AND’, and further combined with ‘AND NOT’ with terms describing educational context out of the scope of this review, such as higher education or ECECFootnote3 (see detailed search syntaxes in Appendix A for each electronic database). A sample search string was:

TITLE-ABS-KEY(“special pedagog*” OR “special need*” OR “special education*” OR SEN OR “individual* education plan” OR IEP OR “special-need*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(inclusion OR inclusive OR “mainstream*” OR “equal education* opportunit*” OR integrat* OR “regular class*” OR “regular education*” OR “ordinary class*”) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY(“higher education” OR university OR college OR “further education” OR preschool* OR kindergarten OR nursery OR “early childhood education” OR ECEC OR ECE)

Data extraction

Studies were identified in line with the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Disagreements in the inclusion process were resolved through discussion among the first and second authors. Then, detailed information about each study was extracted in the EPPI-Reviewer database (http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/) to gain a detailed overview of the existing research. Initially, pilot testing of the data extraction form was conducted by extracting information from five percent of the studies (k = 7) to calibrate the data extraction form. After revising the data extraction form, two authors worked independently to extract data from the included studies. Data items included (a) study details (e.g., authors, publication year, country, study design), (b) sample characteristics (e.g., number of participants, age, gender, educational level covered), and (c) concepts and themes (e.g., descriptions of perspectives on and understandings of inclusion/inclusive education and SEN, and illustrations of pedagogical approaches and practices).

After data extraction, two authors independently categorized the extracted data to classify and summarize the overview of existing research, and to classify the descriptive themes. During this process, meetings were held to discuss the themes and generate further themes by comparing the themes created by each author and/or to refine the themes from the initial categorization, by going back and forth to the data extracted until we came to an agreement/ reached a consensus about the common themes.

Data were displayed using a variety of tabular and graphical forms. Regarding the conceptual themes, we aggregated the core themes identified in the included studies; however, since this is a scoping review, no further attempt was made to synthesize or theorize these themes. Data from the scoping review were also visually synthesized in an evidence gap map (EGM) using EPPI-Mapper application (Citation2020).

Results

Study identification

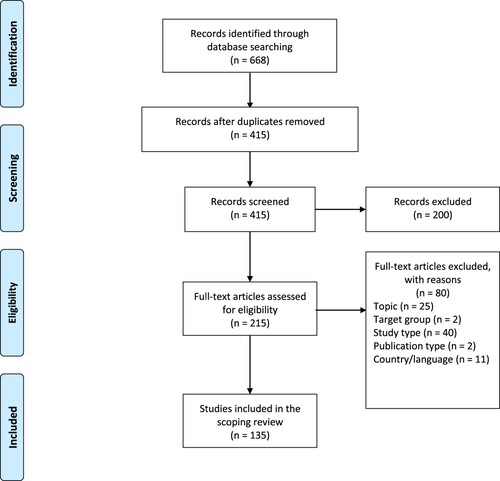

The electronic search produced 668 articles and book chapters across the three databases: 234 from EBSCO, 81 from OVID, and 353 from SCOPUS. The titles and abstracts of these studies were uploaded to the EPPI-Reviewer. After removing 253 duplicates, 415 articles remained for the independent title and abstract screening. Out of these 415 papers, 200 articles were eliminated after initial review due to violation of at least one of the inclusion criteria: excluded due to topic (k = 111), target group (k = 13), study type (k = 38), publication type (k = 7), and country (k = 31). The full texts of 215 studies were uploaded into EPPI Reviewer and thoroughly read, and 80 were excluded after review of the full text. As a result, 135 studies were included in this scoping review.Footnote4 shows the details of the search and study identification process.

Research question 1: characteristics of the empirical studies

Based on our search, there has been a steady increase in the number of empirical studies on inclusion of students with SEN, from only two studies in 2001 to 22 studies in 2020. Twenty-two percent of the studies (30 studies) were conducted between 2000 and 2010, while 78% of the studies (105 studies) were conducted between 2011 and 2020. From 135 studies included, 9 studies involved samples from Denmark, 44 from Finland, 4 from Iceland, 38 from Norway, and 51 from Sweden. Among these studies, 21 of them were comparative multi-country studies that also involved samples from 12 non-Nordic countries (e.g., Italy, Zambia, South Africa). The EGM summarizing the number of articles and characteristics of the included studies is available on https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Portals/35/Maps/KCE/.

The majority of the studies (59%) were qualitative, while the rest of the studies were either quantitative (26%) or mixed-method (15%). The data involved in the studies were mostly cross-sectional (85%), and a few studies investigated a longitudinal change (15%). The design of the included studies was predominantly non-experimental (60%); case studies (16%), ethnographical studies (5%), and document analysis studies (6%). None of the studies applied randomized control trial (RCT) design. Furthermore, only six studies (4%) focused on whether inclusive practices actually work, and only three of them assessed students’ outcomes such as academic achievement or socio-emotional outcomes.

Most of the studies involved a multimethod data collection approach (e.g., observation, interviews) (41.5%) or only a questionnaire (29%) to collect data. Other data collection methods included official documents, field notes, and focus group interviews. Most of the studies focused on only educational staff/ teachers (31.9%), multi-subject (e.g., focusing on both students and teachers) (22.2%), or only students (17%) as the study subject. The data collection mostly involved a multi-informant approach (41.5%), followed by only educational staff/ teachers (32.6%), and documents (e.g., policy documents) (6.7%) as informants. Students were the sole informants (not multi-informant studies) in 8 studies (5.9%), even though they were the only subjects (not multi-subject studies) in 23 studies (17%).

There was a wide range in sample sizes with various sources of data including students, teachers, parents. The highest proportion of research (37%) was undertaken in compulsory school (both primary school and lower secondary school levels), or only in primary school (18.5%). Very few studies focused on upper secondary level students (6%). In 28% of the studies, the educational context where the research took place was either not defined or was not applicable (e.g., document analysis, data from municipalities). In a majority of the included studies, the sample was drawn from mainstream classes/schools (52%), followed by mainstream classes with additional SE hours/classes (12%), only SE classes in mainstream schools (21.5%) or SE school contextFootnote5 (9.6%). In Norway, there was no sample drawn from a SE school context, while in Sweden, seven studies were from SE schools. In a large proportion of the studies (34%), the context was either not defined or not applicable.

Research question 2: core themes on inclusion and SEN

We identified core themes across the perspectives and understanding of inclusion and SEN, and coded the studies accordingly in response to our second research question: Which perspectives and understandings of inclusion and SEN were referred to by the authors of each study? A study was coded within a particular theme when certain terms related to that theme were mentioned.

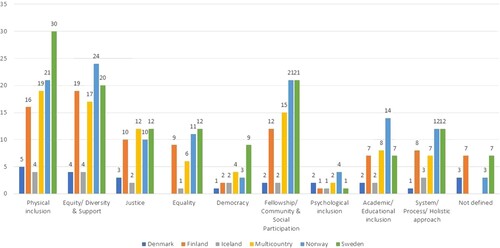

For the perspectives of inclusion, nine main themes emerged: Studies referring to inclusion in terms of (1) physical inclusion (95 studies), (2) equity/diversity and support (88 studies), (3) justice (49 studies), (4) equality (39 studies), (5) democracy (21 studies), (6) fellowship/community and social participation (73 studies), (7) psychological inclusion (11 studies), (8) academic/educational inclusion (40 studies), and (9) system/process/holistic approach (43 studies). In 20 studies, on the other hand, a perspective of inclusion was not explicitly mentioned.

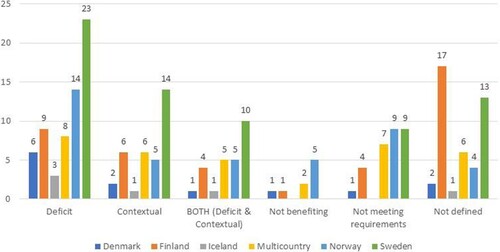

For the perspectives of SEN, four main themes emerged: Studies referring to (1) deficit approach (63 studies), (2) contextual approach (34 studies), (3) not benefiting from ordinary classroom (9 studies), and (4) not meeting/reaching goals/requirements (30 studies). In addition, in 26 studies both deficit and contextual approaches were mentioned, while in 43 studies, there was no explicit perspective referred to by the authors.

and respectively, provide an overview of the main themes of inclusion and SEN perspectives and understandings referred to by the authors in the empirical studies (see also and for the overview of themes for each country).Footnote6 Physical inclusion, fellowship/community, social participation, and equity/diversity and support themes were most prevalent in the concepts of inclusion in Swedish studies. In Norwegian studies, in addition to those three themes, academic/educational inclusion was also emphasized. In Danish and Finnish studies, a justice theme with inclusion as a human right was also dominant. Concerning the perspectives of SEN, referrals to the deficit approach were highly dominant in the primary studies from all countries except Finland, where an understanding of SEN was mostly not explicitly mentioned.

Table 1. Core perspectives of inclusion identified in the included studies.

Table 2. Core perspectives of SEN identified in the included studies.

Research question 3: pedagogical approaches and practices

The inclusive pedagogical approaches and practices referred to by the authors in the included empirical research to include students with SEN (research question 3) were categorized under six main themes: Approaches and practices focusing on (1) mainstreaming (31 studies), (2) segregation (27 studies), (3) class structure/differentiation (84 studies), (4) social/psychological/cognitive aspects and participation (24 studies), (5) instruments/ tools/assessments designed for inclusion (10 studies), and (6) system approach (43 studies).

We categorized approaches and practices involving mainstream regular class and traditional teaching under mainstreaming, while approaches and practices involving separate education outside of the mainstream school or using full-time segregated classes or schools as segregation. These two approaches were mainly described when concerning the placement of students with SEN.

The largest category (class structure/differentiation) involved specific SE practices adopted within mainstream schools such as having an extra teacher, mentor, SE teacher in the regular classroom, one-to-one teaching outside the classroom, using individual support plans (IEP), adapting facilities to groups with SEN, variety and flexible teaching practice in the classroom, adjustment of class size, introductory class for minorities, teaching in small groups within the regular class. This approach was mainly about using diverse and multiple strategies to cater to the students with different SEN.

The fourth category, social/psychological/cognitive aspects and participation, involved approaches and practices with a focus on social and psychological support such as help from a peer, promoting peer acceptance and support, encouraging social atmosphere, and involving students in the process. The practices under this category were more directed towards social training, participation, and learning activities to support students with SEN.

The instruments/tools/assessments designed for inclusion category included, for example, the use of supplementary equipment and materials, the use of art lessons, or instruments for systematic evaluation and improvement. The practices were mostly involving various technologies or tools to create technology-enhanced learning environments. Lastly, the system approach practices included approaches and practices with a holistic view and involvement of various actors. The focus of these practices and approaches was mostly on the collaboration across various actors to provide support to all students. Some examples include but are not limited to, the use of co-teaching and consultation, cooperation with municipal teams and school administrators, parent involvement and cooperation, providing autonomy to municipalities and schools.

Discussion

This systematic scoping review aimed to identify the body of empirical studies on the inclusion of students with SEN and conceptual mapping of how perspectives on particular concepts (i.e., inclusion, SEN) are referred to by the authors in the empirical literature in Nordic countries. Through the comprehensive literature search of relevant peer-reviewed articles and book chapters in three databases, we identified 135 eligible studies. Overall, this overview of the included empirical research revealed that the majority of the research was qualitative (59%), cross-sectional (85%), conducted in Sweden (30%), and investigated inclusion of students with SEN in compulsory education (37%) educated in mainstream classes/schools (52%). A recent qualitative review of inclusion in practice in the Nordic countries also found similar results (i.e., majority of qualitative studies, most studies conducted in Sweden) despite the limited coverage with 34 included studies (Buli-Holmberg et al., Citation2022).

Overview of gaps in the existing empirical research

There has been a steady increase in the number of empirical studies on inclusive practices of students with SEN over time in the Nordic countries. This reflects an increasing need and attempts to understand inclusive educational systems in the Nordic countries.

The majority of the empirical research eligible in this review was qualitative and cross-sectional, predominantly with non-experimental designs, and none of the studies applied an RCT design. The limited variation in study design and methodology narrows the scope of research questions asked and possible results that can inform practice. The fact that quantitative and longitudinal studies are underrepresented results in few studies that investigate the effects of inclusive practices, how these work across time, and how this affects students with SEN in the long run. Considering that inclusive practice has the purpose of improving outcomes for students with SEN, both socially and academically, it is worrying that the effects of different inclusive practices and approaches have not been investigated to a greater extent. Effect studies are necessary to inform policy and practice about which practices can provide opportunities for students to learn and develop positively. Hence, there is a need for longitudinal research using quantitative and mixed methods, with randomized control research designs.

The highest proportion of research was undertaken in compulsory schools (both primary school and lower secondary school levels), with very few studies focused on the upper secondary level. This may be because fewer students in upper secondary receive a SEN label (Markussen et al., Citation2019). For example, in Norway, there is a marked drop in the number of students who are defined as having SEN when they transfer from the final year of lower secondary school to the first year of upper secondary. Students may choose subjects they are more interested in, and vocational classes are often smaller and can cater to special needs. In upper secondary, about 66% of students with SEN are organized in smaller groups and the remainder take part in mainstream classes (Markussen et al., Citation2019). Longitudinal studies will be key in shedding light on how transitions, organizational structures, and student choice can matter for students with SEN in upper secondary school.

Most of the samples in the included studies were drawn from mainstream classes or schools but there was still variation; some samples were from additional SE hours/classes or a SE school context. There was also variation across countries. For example, in Norway, in line with the aim of the Education Act (Ministry of Education and Research, Citation1998) to reduce full-time placements in special schools or classes, no study included a sample drawn from a SE school context, while in Sweden seven studies (approximately 14%) involved samples from SE schools.

Even though a multi-informant approach was used to collect data in many studies (41.5%), students were rarely informants even when they were the only subjects being studied. It is disconcerting that students in the Nordic countries so seldom inform studies that investigate their own well-being and learning, especially since children's right to be heard in matters affecting them follows from the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, Citation1989). To get a better insight into how inclusive education affects and is perceived by students, students’ perspectives should be heard in research on inclusion and inclusive practices in schools. More research is also needed to involve various stakeholders’ perspectives such as families, and school personnel. Students with SEN are also a highly heterogeneous group with various SEN including different types of underlying disabilities or diagnoses, and hence, different needs. More research is needed for better identification of those specific needs.

Overview of conceptual themes, pedagogical approaches, and practices

One of the aims of this scoping review was to investigate which perspectives and understandings of inclusion and SEN have been referred to by the authors in the empirical research in the Nordic countries. This varied greatly across studies and is in line with the two aspects of inclusion that most scholars agree upon; that it is hard to define and has many different interpretations and that inclusion is not solely about physical placement (Göransson & Nilholm, Citation2014). It reflects the different and sometimes contradicting ideologies, including political, scientific, ideological, and ethical reasons for educational inclusion (Qvortrup & Qvortrup, Citation2018). A narrative review of research in European and North American journals (Nilholm & Göransson, Citation2017) expressed a concern that we share: “Agreement within a research field concerning how basic concepts are to be understood is, of course, desirable. In the light of this, it seems extraordinary that the definition of inclusion varies so much between articles and at times also within the same article” (p. 447).

Despite the variety in perspectives of inclusion, the identified themes of inclusion are in line with a perspective of inclusion as an ongoing process covering an array of values such as fellowship, participation, democratization, equal access, equity, and justice for all students (Booth, Citation1996). However, the most salient emerging category was physical inclusion and inclusion as an issue of placement (i.e., in mainstream schools and classes). This finding corroborates with the findings of Nilholm and Göransson (Citation2017) who also found that, with a few exceptions, inclusion most often indicates placement. Hence, inclusion is often seen as an issue that can be solved with the physical placement of students with SEN within the mainstream school environment.

Equity perspectives, which emphasize accommodation to a diversity of learners and provision of support in line with the individual needs, were also dominant discourses in how inclusion was referred to by the authors in the studies. In this approach, inclusion is regarded as beneficial for all students with difficulties regardless of where the education takes place (Nilholm & Göransson, Citation2017). The advocates of the perspective of physical inclusion can argue that the three-tier model may challenge inclusion since the three-tier approach directs students into different tracks, small groups, or individual instruction outside the mainstream setting, hereby “returning to the status quo of segregated special education” (Ferri, Citation2012, p. 863). On the other hand, others emphasizing the equity perspective argue that adapted education is a prerequisite for inclusion, which “may involve students being treated unequally in order to achieve equity” (Nes & Strømstad, Citation2006, p. 366). However, the three-tier model is also implemented in many ways in different countries, which may reflect various perspectives in implementation.

Together, the perspectives on inclusion that were mentioned in the included studies cover the three levels that should be considered in a comprehensive definition of inclusion as argued for by Qvortrup and Qvortrup (Citation2018); (1) physical inclusion in the community (numeric level), (2) whether the student is socially active in the community (social level), and (3) whether the student feels recognized by the members of the community and has a sense of school belonging (psychological level). However, these aspects were not always mentioned together, and research may often be guided by just one particular level thereby limiting the ability to represent a holistic perspective of inclusion.

While there was a large variation in how authors presented the perspectives of inclusion, the picture is somewhat clearer for the understanding of SEN. However, the relatively large number of studies, especially from Finland, that did not describe SEN, reflect that little attention has been paid to defining the term with meaningful content rather than using it as a euphemism (Vehmas, Citation2010). Across the studies that refer to the perspectives of SEN, a deficit approach, where SEN are ascribed to the students and individual shortcomings, was the most common discourse described in the studies in all Nordic countries (referred to in approximately 66% of the studies). Hence, this approach advocates that the student should fit the system. This approach is also prevalent in the attitudes of educational professionals. For example, a study among school administrators’ perspectives on SE policy and practice in Norway and Sweden revealed that among six potential reasons, students’ deficits were indicated as a common reason among 97.3% and 74% of municipalities in Norway and Sweden, respectively (Cameron et al., Citation2012).

A contextual approach to SEN, where SEN are ascribed to the context such as school social and physical environment and activities, school problems in teaching, attitudes of teachers, was described in 44% of the studies, either by itself or in addition to the deficit approach. In 20% of the studies, both a deficit and contextual approach or their interaction have been stated. That is, the studies mentioned that SEN may have arisen as a direct result of both individual deficits and inadequate environmental conditions or as a result of an interaction between these. These categories overlap with the medical model, social model, and biopsychosocial model of disability deployed by the WHO (World Health Organization, Citation2002).

Two additional themes, where authors do not explicitly emphasize whether the problem lies in the student or the context, also emerged. “Not benefiting from ordinary classroom practices” was mostly referred to by the authors in Norwegian studies, likely because the Education Act in Norway explicitly uses this definition: “Pupils who either do not or are unable to benefit satisfactorily from ordinary teaching have the right to special education.” (Ministry of Education and Research, Citation1998, Section 5.1.). Nevertheless, several Norwegian articles also referred to SEN as “Not meeting the requirements”, indicating that these two categories may often go hand in hand in Norway. In contrast, the concepts seem separated in the Swedish literature as the framing of SEN as a “lack of benefitting from ordinary practices” was not mentioned in any paper but “not meeting the requirements” was.

Pedagogical practices that facilitate inclusion by adapting the class structure or applying differentiative education were the most referred category in line with the equity approach. This is in line with a general conception of inclusion as an approach that is characterized by “providing for all by differentiating for some” (Florian & Black-Hawkins, Citation2011). A report on the effect of including students with SEN in mainstream classes on their scholastic and social development differentiated some of the practices and approaches we also found as “targeting schools” such as using co-teachers and as “targeting pupils” such as peer tutoring (Dyssegaard & Larsen, Citation2013). However, not all studies included established a positive effect of these practices in inclusion of students with SEN. It is argued that the inclusion of students with SEN is more difficult to implement in practice (Ogden, Citation2014) than to formulate in legislation (Sundqvist & Hannås, Citation2021). While politicians or other authorities in legislative power decide on the goal of an educational system (e.g., inclusive education), practitioners (e.g., teachers) have to implement and translate these goals into practice (Göransson & Nilholm, Citation2014; Van Mieghem et al., Citation2020). In this process, the lack of resources, competence, as well as negative attitudes can be the biggest obstacles to inclusive education and may result in variation in the pedagogical approaches and practices.

Limitations

The results of this scoping review should be interpreted with some caution. The scope was limited, since we only included English-language studies in peer-reviewed journals and book chapters, excluding grey literature. The relevant literature may also not be fully covered due to the search string in line with the a priori defined inclusion and exclusion criteria of this review. In addition, the purpose of a scoping review is to provide an overview of the current research, this means that data extraction and conceptual mapping takes place on the descriptive level and that the content is not synthesized or theorized in depth. This may result in more detailed information not being captured in the aggregative process. With research question three, we initially aimed to get an overview of the implemented inclusive pedagogical approaches and practices to include students with SEN in mainstream schools. However, during the process of categorizing the extracted data, it appeared to be difficult to pinpoint the degree to which the approaches and practices were taking place. Some studies were document analysis, some studies reported on retrospective memory, other studies reported on specific research interventions rather than general practice, and other studies focused on participants’ attitudes towards certain practices. What we could report were the approaches referred to by the authors in the articles. Thus, it is important to note that they do not necessarily reflect what is actually happening in practice in each country. Similarly, the perspectives and understandings of inclusion and SEN extracted are the ones referred to by the authors in these articles and do not necessarily reflect the positions/stands held by the authors. It is also worth noting that the challenges of the authors in the primary studies in reflecting the original concepts in English (translating the meaning) should be considered in interpreting the results.

Implications

The results of this scoping review reveal that SEN is a term that authors in the Nordic empirical literature often avoid explaining and when it is done there are major differences in the conceptualization across studies. This has not only implications for research but importantly, views on special needs direct students to various educational and social careers and therefore have great practical significance (Vehmas, Citation2010). Scholars argue that while disabilities or diagnoses might be an indicator for the type of needs a student might have, the identification of those needs is dependent on an understanding of how this affects the individual in a particular learning environment (Kärnä, Citation2015).

How SEN is conceptualized also has implications in terms of how interventions should be carried out and what they should target. When adopting a deficit or medical approach, the problem is thought to lie in the individual. Then, the interventions, practices should target the individual: “to “correct” the problem with the individual” (World Health Organization, Citation2002, p. 8). However, in line with the contextual or social approach, the interventions require a political response to correct the socially created problem by “the environment brought about by attitudes and other features of the social environment” (p. 9).

This review identified a heavy emphasis on deficit-based ideologies and approaches in the Scandinavian research and shows a lack of strengths-based perspectives or approaches. Including these or shifting to a more strengths-based approach can contribute to new pedagogical approaches that could enhance inclusion in a more comprehensive way.

Conclusions

This scoping review revealed a gap regarding evidence on whether inclusive practices work – only six studies covered this issue, none of them were controlled studies, and only three of them assessed students’ outcomes such as academic achievement or socio-emotional outcomes. Since very few studies reported reliably on actual practices of inclusion, it is difficult to form a clear picture of what is done to create an inclusive environment and the degree to which the Salamanca Statement has reached not only policy but also practice. Another prominent result of this scoping review is the absence of students’ voices and clear and uniform understandings of inclusion and SEN. Scholars have argued that a “lack of clarity about definitions of inclusion has contributed to confusion about inclusive education and practice, as well as to debates about whether or not inclusion is an educationally sound practice for students who have been identified as having special or additional educational needs.” (Florian & Black-Hawkins, Citation2011, p. 826).

The take-home message for research on inclusion in the Nordic countries is that there is still a need to clarify perspectives of inclusion and of who needs support. In addition, studies with high methodological rigour, as well as quantitative, and mixed-method studies on actual practice and student outcomes – including students’ voices – are needed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (35.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 An extensive systematic presentation of the inclusive policies in the Nordic countries is outside the scope of this study. Readers are referred to other studies for more country-specific information (e.g., Arnesen & Lundahl, Citation2006; Engsig, Citation2016; Halinen & Järvinen, Citation2008; Jónsson, Citation2016; Magnússon et al., Citation2019).

2 The proxy indicators for inclusion in mainstream groups/classes vary slightly from country to country (see https://www.european-agency.org/data/data-tables-background-information).

3 The educational context and content of ECEC varies greatly between countries and is in many countries quite different from the context of formal schooling. We therefore regarded it as not as useful to merge results from the two educational systems and think that inclusion in ECEC would be better studied in a separate review.

4 The list of the included studies as well as the detailed overview of the included studies can be requested from the first author.

5 Even though the context of SE schools is contrary to inclusive education concept, these studies included samples from SE schools sharing the same surrounding with a mainstream school (e.g., sharing the playground).

6 Due to the large number of included studies, study-based information cannot be provided within the manuscript limits, however, can be provided upon request, by contacting the first author.

References

- Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2020.1729587

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Arnesen, A.-L., & Lundahl, L. (2006). Still social and democratic? Inclusive education policies in the Nordic Welfare States. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830600743316

- Berhanu, G. (2014). Special education today in Sweden. In Special education international perspectives: Practices across the globe. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0270-401320140000028014

- Booth, T. (1996). A perspective on inclusion from England. Cambridge Journal of Education, 26(1), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764960260107

- Brussino, O. (2020). Mapping policy approaches and practices for the inclusion of students with special education needs (OECD Education Working Papers, No. 227. OECD Publishing, Paris, Issue. https://doi.org/10.1787/600fbad5-en.

- Buli-Holmberg, J., Høybråten Sigstad, H. M., Morken, I., & Hjörne, E. (2022). From the idea of inclusion into practice in the Nordic countries: A qualitative literature review. European Journal of Special Needs Education, https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2022.2031095

- Buli-Holmberg, J., & Jeyaprathaban, S. (2016). Effective practice in inclusive and special needs education. International Journal of Special Education, 31(1), 119–134. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1099986&scope=site.

- Cameron, D. L., Cook, B. G., & Tankersley, M. (2012). An analysis of the different patterns of 1:1 interactions between educational professionals and their students with varying abilities in inclusive classrooms. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(12), 1335–1354. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.580459

- Djordjevic, S., Stanojevic, D., & Djordjevic, L. (2018). Attitudes towards inclusive education from the perspective of teachers and professional associates. TEME, 42(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.22190/TEME1801001D.

- Dyssegaard, C. B., & Larsen, M. S. (2013). Evidence on inclusion: Danish clearinghouse for educational research. Danish Clearing House.

- Digital Solution Foundry, & EPPI-Centre. (2020). EPPI-Mapper (Version 1.2.5) [Computer software]. UCL Social Research Institute, University College London. https://protect-us.mimecast.com/s/Z1uTCR6MLxfnrq28ms9WzFM?domain=eppimapper.digitalsolutionfoundry.co.za

- Egelund, N., & Dyssegaard, C. B. (2019). Forty years after warnock: Special needs education and the inclusion process in Denmark. Conceptual and practical challenges. Conceptual and practical challenges [Empirical Study]. Frontiers in Education, 4(54), https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00054

- Engsig, T. T. (2016). The evolution of inclusive education in Denmark: a history of inclusions – from rights-based to accountability and competition. Afhandling præsenteret på 2016 International Summit on RTI and Inclusive Education, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, Indien.

- Ferri, B. A. (2012). Undermining inclusion? A critical reading of response to intervention (RTI). International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(8), 863–880. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2010.538862

- Florian, L., & Black-Hawkins, K. (2011). Exploring inclusive pedagogy. British Educational Research Journal, 37(5), 813–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2010.501096

- Göransson, K., & Nilholm, C. (2014). Conceptual diversities and empirical shortcomings – a critical analysis of research on inclusive education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 29(3), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2014.933545

- Halinen, I., & Järvinen, R. (2008). Towards inclusive education: The case of Finland. Prospects, 38(1), 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-008-9061-2

- Jónsson, O. P. (2016). Democratic and inclusive education in Iceland: Transgression and the medical gaze. Nordic Journal of Social Research, 7(2), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.7577/njsr.2097

- Kärnä, E. (2015). Inclusive research and learning environments: Ideas and suggestions for inclusive research and the development of supportive learning environments for children with autism and intellectual disabilities. In R. G. Craven, A. G. S. Morin, D. Tracey, P. D. Parker, & H. F. Zhong (Eds.), Inclusive education for students with intellectual disabilities (pp. 117–138). IAP Information Age Publishing, US.

- Krämer, S., Möller, J., & Zimmermann, F. (2021). Inclusive education of students with general learning difficulties: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 91(3), 432–478. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654321998072

- Lindsay, G. (2007). Educational psychology and the effectiveness of inclusive education/mainstreaming. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906X156881

- Magnússon, G., Göransson, K., & Lindqvist, G. (2019). Contextualizing inclusive education in educational policy: the case of Sweden. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 5(2), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2019.1586512

- Markussen, E., Carlsten, T. C., Grøgaard, J. B., & Smedsrud, J. (2019). « … respekten for forskjelligheten … ». En studie av spesialundervisning i videregående opplæring i Norge skoleåret 2018–2019 (8232704098). NIFU.

- Ministry of Education and Research. (1998). Act relating to primary and secondary education and training. Lovdata. https://protect-us.mimecast.com/s/opd9CVO5NBc0loG1wczrWNX?domain=lovdata.no

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moher, D., Stewart, L., & Shekelle, P. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0458-6

- Nes, K., & Strømstad, M. (2006). Strengthened adapted education for all—No more special education? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 10(4–5), 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110500264610

- Nilholm, C., & Göransson, K. (2017). What is meant by inclusion? An analysis of European and North American journal articles with high impact. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(3), 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2017.1295638

- Nordahl, T., Persson, B., Dyssegaard, C. B., Hennestad, B. W., Wang, M. V., Martinsen, J., Vold, E. K., Paulsrud, P., & Johnsen, T. (2018). Inkluderende fellesskap for barn og unge. Fagbokforl.

- Norwegian Education Act: Act relating to Primary and Secondary Education and Training (LOV-1998-07-17-61). (1998). https://lovdata.no/dokument/NLE/lov/1998-07-17-61.

- Ogden, T. (2014). Special needs education in Norway - The past, present, and future of the field. In M. Tankersley, B. G. Cook, & T. Landrum (Eds.), Special education past, present, and future: Perspectives from the field (Vol. 27, (pp. 213–238). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0735-004X20140000027012

- Peters, M. D., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

- Qvortrup, A., & Qvortrup, L. (2018). Inclusion: Dimensions of inclusion in education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(7), 803–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1412506

- Ratner, H. (2016). Modern settlements in special needs education: Segregated versus inclusive education. Science as Culture, 25(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2015.1120283

- Reindal, S. M. (2016). Discussing inclusive education: an inquiry into different interpretations and a search for ethical aspects of inclusion using the capabilities approach. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 31(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2015.1087123

- Roiha, A. S. (2014). Teachers’ views on differentiation in content and language integrated learning (CLIL): Perceptions, practices and challenges. Language and Education, 28(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2012.748061

- Ruijs, N. M., & Peetsma, T. T. (2009). Effects of inclusion on students with and without special educational needs reviewed. Educational Research Review, 4(2), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2009.02.002

- Sundqvist, C., Björk-Åman, C., & Ström, K. (2019). The three-tiered support system and the special education teachers’ role in Swedish-speaking schools in Finland. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(5), 601–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1572094

- Sundqvist, C., & Hannås, B. M. (2021). Same vision–different approaches? Special needs education in light of inclusion in Finland and Norway. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(5), 686–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1786911.

- Tirri, K., & Laine, S. (2017). Ethical challenges in inclusive education: The case of gifted students. In A. Gajewski (Ed.), Ethics, equity, and inclusive education (Vol. 9, pp. 239–257). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-363620170000009010

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Kastner, M., Levac, D., Ng, C., Sharpe, J. P., & Wilson, K. (2016). A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4

- UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for action on special needs education: Adopted by the world conference on special needs education; access and quality. Salamanca, Spain, 7-10 June 1994. UNESCO.

- UNESCO. (2008). Education for all global monitoring report: Education for all by 2015. Will we make it?

- UNESCO. (2017). A guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education. Geneva: UNESCO IBE. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf000, 2482, 54.

- United Nations. (1989). UN General Assembly, Convention on the Rights of the Child https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text.

- United Nations. (2015). “Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, sustainabledevelopment.un.org.

- Van Mieghem, A., Verschueren, K., Petry, K., & Struyf, E. (2020). An analysis of research on inclusive education: A systematic search and meta review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(6), 675–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1482012

- Vehmas, S. (2010). Special needs: A philosophical analysis. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504143

- World Health Organization. (2002). Towards a common language for functioning, disability, and health: ICF. https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf.