ABSTRACT

This study examined the factors shaping co-teaching within a Finnish primary school's community. The qualitative study was conducted by teacher and principal interviews and teacher surveys. Thematic content analysis revealed five factors establishing the co-teaching practices: providing collegial support, team building, continuous professional development, the intrinsic value of co-teaching, and the structure of the work community. These factors aggregated into two larger arenas: teachers’ sphere of influence and systemic elements -arena, which was experienced to be beyond individual teacher influence. These factors illustrate the complexity of the work community with co-teaching and how they can both complicate and contribute to an educator's daily work. In addition, individual, community and resource-specific challenges regarding co-teaching emerged. Finally, we identified three educator profiles on the involvement in decision-making when developing co-teaching practises. We distinguished pioneers, travelling companions and critical observers as three diverging roles that educators have adopted in influencing the decision-making.

1. Introduction

Due to rapid global changes in society, technological development and migration, educators must solve nonroutine problems, engage in continuous professional learning and perform professional innovations to improve the quality of learning and teaching (Lehtinen et al., Citation2014). Within this development, it appears necessary to change the focus from emphasising mere personal professional capabilities towards cultivating educators’ social and community proficiency. Finland's National Core Curriculum for Basic Education (Finnish National Board of Education, Citation2014) has steadily been developed towards a community view of teaching and learning, thus making teacher's professional work more collaborative. Building professional learning communities (PLC) and developing the practices of co-teaching are transforming teachers’ solitary work into collaborative work (Ronfeldt, Citation2017). Because not all forms of cooperation are useful, though, it is important to share experiences of building collaborative teacher communities and develop the practices of co-teaching. It is imperative for every school practitioner to see the overall picture of working together and to strive to develop it (Hargreaves & O’Connor, Citation2018). The purpose of the present interview study was to examine the Finnish school community's experiences of developing co-teaching practices.

According to an extensive review (Vangrieken et al., Citation2015), there has been conceptual confusion concerning teacher collaboration along several partly overlapping terms, such as teacher teams, teacher collaboration, professional (learning) communities, (teacher) learning communities, (teacher) learning teams and so on. Earlier research has emphasised the various forms and dimensions of collaboration, cooperative teaching (Bauwens et al., Citation1989), collaborative teaching (Nevin et al., Citation2009) and team teaching (Baeten & Simons, Citation2014). Little (Citation1990) refined the term “collaboration” by distinguishing different types of collaboration based on how a teacher's independence is transformed towards interdependency. In many definitions, the focus is on tasks, including working and reflecting together for job-related purposes (James et al., Citation2007; Kelchtermans, Citation2006). Working together may mean that partners do all the work together as opposed to cooperation, in which partners split the work and combine the final outcome (Sawyer, Citation2006). Collaboration is seen as different from collegiality, with the latter focusing on the relationships among colleagues (Bovbjerg, Citation2006; Datnow, Citation2011; Kelchtermans, Citation2006) and being based on mutual sympathy, solidarity, equal work situation and so forth. Based on Vangrieken et al. (Citation2015), collaboration can be defined as joint interaction in the group in all activities needed to perform a shared task. The term collaboration, therefore, is not static or uniform but rather an umbrella term, under which different types of collaboration can occur with varying depths.

According to Thousand et al. (Citation2006), team teaching refers to a team of teachers planning, teaching and assessing together, that is, activities that are visible, integrated in teachers’ roles and take place in the classroom environment. White et al. (Citation1998) separated the rotational and participant-observer models of team teaching from interactive team teaching, where simultaneously present teachers have equal roles in the classroom. In the rotational team teaching model, the division of labour is tighter, and teachers visit the classroom when their expertise is needed; here, a course coordinator is responsible for organising the teaching. In the participant-observer model, teachers alternate between leading the teaching process, assisting by making comments and providing examples. Further, Thousand et al. (Citation2006) described the main alternatives to participation: complementary, supportive and parallel team teaching and teaming.

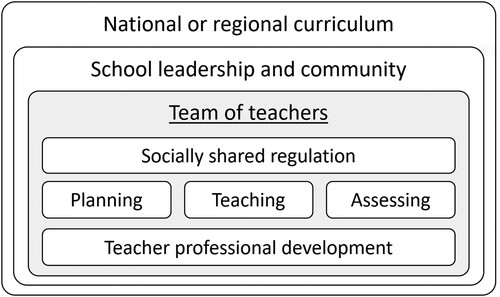

The definitions of co-teaching (as reviewed by Baeten & Simons, Citation2014; Fluijt et al., Citation2016) have often focused on classroom logistics, ignoring pedagogics (Anderson & Speck, Citation1998) and everything outside the classroom (Härkki et al., Citation2021). Instead, co-teaching definitions appear to refer to teacher collaboration in planning, teaching and assessing pupil work. Working relationships between general and special educators and inclusive classrooms are also frequently mentioned (Fluijt et al., Citation2016). Härkki et al. (Citation2021) argued that team-level regulation can occur either as coregulation, where individuals’ regulatory activities are guided and managed by other team members, or as socially shared regulation, where decisions and activities are made together (see also Järvelä & Hadwin, Citation2013). Härkki et al. (Citation2021) constructed a framework modelling co-teaching embedded in its context (see ), highlighting the value of socially shared regulation of co-teaching.

Figure 1. A model of contextualised team teaching (original by Härkki et al., Citation2021).

Co-teaching is also associated with the contexts of special education needs (SEN) pupils (Friend et al., Citation2010). Here, co-teaching is enacted when teaching is handled by two or more professional teachers (no “paraprofessionals” accepted). Further, it is expected that co-teaching will change the earlier teaching practices in terms of joint planning and shared responsibility, and that the pupils are divided into smaller groups on a case-by-case basis (Friend et al., Citation2010; Friend & Reising, Citation1993). Because co-teaching creates demands for teachers, they must engage in intensive collaboration, not only in classrooms, but also when planning lessons, setting common targets, sharing responsibilities and discussing their expectations for co-teaching (Conderman et al., Citation2009). The practical models for co-teaching include several options to be selected for different occasions, depending on whether there is a need to divide the pupils into smaller groups, keep them in the same bigger group or use station teaching (Conderman et al., Citation2009; Friend et al., Citation2010). In the current study, co-teaching is referred to as the cooperation of two or more teachers and includes planning, executing and reviewing actions.

1.1. Co-teaching in Finland

The Finnish educational policy places great trust on Finnish teachers, and they have a high level of autonomy (Niemi et al., Citation2018). Finnish teachers value building communities in schools with minimal social hierarchy (Klassen et al., Citation2018), and schools are based on rather conservative models and are prone to remain static due to high autonomy and established work routines (Johnson, Citation2006). The 2020 Working Life Survey indicated that class, subject and special needs teachers all agree that co-teaching can build the professional development of a school community and advance professional skills. Nonetheless, their views on its effect on agency varied: some experienced an increase in teacher agency, while others a reduction (Takala & Saarinen, Citation2020).

A 2010 study conducted in Helsinki found that only a third of comprehensive school class teachers implemented co-teaching weekly, but a feeling of satisfaction with co-teaching as a method was more common amongst them (Saloviita & Takala, Citation2010). A decade later, in 2021, half of the comprehensive school class teachers implemented two to four hours of co-teaching into their weekly lessons. Those who practiced co-teaching more often deemed it beneficial and less challenging than nonparticipants (Kokko et al., Citation2021). Finnish principals have viewed co-teaching as building mutual goals and working methods as well as assisting in the renewal of operational practices of the school community. Both principals and teachers deem co-teaching to be a valuable aspect of school life (Ahtiainen et al., Citation2011).

In recent decades, teaching in Finnish comprehensive schools has taken a developmental trend towards becoming more inclusive. Inclusive teaching aims to give all pupils basic education with the required needs and offer support to diverse pupils’ learning and personal growth. Inclusion in education may be defined as preventing and minimising the pupil's challenges with learning and participation in education, aiming towards the pupil's well-being. The main point is to give them a feeling of acceptance in their school community (Kyrö-Ämmälä & Arminen, Citation2020); previous studies have shown that co-teaching and inclusion are beneficial duo in school communities (Scruggs et al., Citation2007). Consequently, inclusion is only implicitly present in the current article.

1.2. Benefits of co-teaching

Certain positive themes have resurfaced when discussing teachers’ experiences on co-teaching. Co-teaching provides more support to teachers and enables inclusive teaching in a classroom setting consisting of a heterogeneous pupil group (Sirkko et al., Citation2020). Having another adult in a classroom is seen as invaluable (Kohler-Evans, Citation2006) as it presents a possibility for professional development (Roth & Tobin, Citation2002; Scruggs et al., Citation2007). When co-teaching provides a supportive and safe environment for teachers, they can construct a shared archive of professional knowledge and gain professional competence through learning from each other (Rytivaara & Kershner, Citation2012).

Co-teachers have noted that co-teaching reaches more pupils and positively affects pupil achievement (Kohler-Evans, Citation2006). A synthesis of co-teaching found that teachers see co-teaching to be beneficial for pupils’ social skills (Scruggs et al., Citation2007). For instance, general education pupils benefit from co-teaching because they get more personal assistance from teachers (Walther-Thomas, Citation1997).

Co-teaching encourages teachers to utilise their personal strengths and mutually share responsibility. When several teachers plan, execute and review teaching, the quality of education improves. Learning difficulties are detected more deficiently, and more productive remedial solutions are implemented. Thus, adequate learning support can be given more easily in teaching situations. When executed correctly, co-teaching can provide massive support to inclusion in school communities (Takala et al., Citation2020).

1.3. Requirements and demands for successful co-teaching

Although teachers generally see co-teaching as a viable model, a fifth of them noted that their colleagues do not support co-teaching as a method (Chitiyo, Citation2017). In a study of eight co-teaching pairs, teachers who have a growth mindset towards learning and teaching and appreciate opportunities for open dialogue have a positive view of co-teaching (Guise et al., Citation2017).

Several factors can be seen as prerequisites to successful co-teaching, such as professional well-being, similar perceptions of teachership, engaging in professional development and joint planning and reviewing of teaching (Sirkko et al., Citation2020). To be successful, co-teaching requires both external support from the school administration (Härkki et al., Citation2021) and a compatible relationship between the co-teachers for co-teaching (Pratt, Citation2014). Such compatible relationships may be reached through a three-part process of learning from each other, valuing mutual differences and building joint working strategies (Pratt, Citation2014). A successful co-teachership can be seen as a process of professional learning where the teachers create unique space for co-teaching. The main elements required to achieve this are commitment, time for negotiations, constructing different meanings to co-teaching and sharing professional knowledge (Rytivaara et al., Citation2019).

Co-teaching can be seen as a four-category continuum including requirements, interpretations, inclusion and professional joy (Sirkko et al., Citation2018). The first two focus on the logistics of co-teaching, as one needs the approval of the principal and a willing partner to start co-teaching. Inclusion focuses on adapting to a pupil's individual needs. Joy shows the positive emotions and power that are created when co-teaching is functional and includes open dialogue and an accepting atmosphere between the co-teachers (Sirkko et al., Citation2018). Co-teaching provides a sense of belonging and consists of three dimensions: teachers’ work practices, mutual relationships and personal characteristics. There are factors that enhance the sense of belonging, such as division of labour, a respecting and trusting relationship and similar pedagogical thinking, while hindering factors are discomfort, disrespect and differences in pedagogical thinking (Pesonen et al., Citation2021).

According to Härkki et al. (Citation2021) three qualitatively different co-teaching profiles emerged from the data of eight co-teaching pairs: (1) highly functional collaboration, (2) collaboration and (3) imbalanced co-operation. The collaborative profile had well-functioning co-teaching, while highly functioning teams were distinguished by having higher levels of co-construction, professional drive and socially shared regulation, e.g., making decisions together rather than being supported or shaped by other team members. In contrast, the imbalanced profile implemented co-teaching superficially, lacking in planning and teaching, balancing the workload, as well as having remarkable value differences and disagreements in teaching content. Thus, effective co-teaching also requires the handling of team-specific challenges through team reflection (Fluijt et al., Citation2016).

The biggest challenges of co-teaching are the limited understanding of co-teaching and its models, an imbalanced power dynamic between the teachers (Guise et al., Citation2017), administrative aspects such as scheduling collective planning time and lack of it (Ahtiainen et al., Citation2011; Scruggs et al., Citation2007) and finding the right co-teaching partner (Kokko et al., Citation2021; Sirkko et al., Citation2018). Special educators working with general educators have found that the lack of focus and trust in professional colleagues are the main hindrances to the successful co-teaching implementation (Morgan, Citation2016). Perceived positive aspects of co-teaching include collegial and pedagogical support, variation in everyday life, adaptability, and the possibility to give individual support (Ahtiainen et al., Citation2011). Equality between co-teachers, open dialogue, and the willingness to share responsibility within teaching enabled successful co-teaching (Guise et al., Citation2017).

2. Research aims

The purpose of the study is to examine factors relevant for building co-teaching practices in a certain school community, as well as disclose the challenges surrounding co-teaching and educators’ views of decision-making when developing co-teaching practises within their workplace community. The research questions for this study are as follows:

What factors emerge in the nature of co-teaching?

What challenges do educators perceive in implementing co-teaching practices?

How do different views of involvement in decision-making emerge regarding the development of co-teaching?

3. Methods

3.1. Research context

The current study was a part of a co-development project between Helsinki University and the City of Helsinki Education Division, aiming to support the participating schools in their organisational culture transformation. The school was a primary education school with 36 educators, consisting of teachers and school leaders, and over 350 pupils located in Helsinki. The data collection was a part of the school improvement work and enabled the researchers to identify the school's development targets.

3.2. Data collection

Research data were collected using two qualitative methods. First, 10 teachers, one vice-principal and one principal, of which two were men and 10 women, were interviewed in September 2019. Of the teachers, all but one were class teachers. The interviewed teachers were chosen to represent different grade levels and lengths of professional expertise. The interviews took approximately 1 hour, and were conducted on the school premises during participants’ working hours. The thematically semi-structured interview framework consisted of the following topics: (1) background questions, (2) school's development targets, (3) collaboration and teamwork, (4) professional development, and (5) school culture.

Second, a co-teaching questionnaire with open-ended items was administered to all teachers at the school, because co-teaching was mentioned in the interview as a desired development target of the school community. The questionnaire included detailed questions about co-teaching practices in the school, as well as teachers’ ideas on how it should be developed. Only the answers of the interviewed teachers (n = 10) have been included in the present study. The recorded interviews were transcribed and pseudonymised together with the questionnaire data.

3.3. Data analysis

A qualitative content analysis was performed, and the data were categorised with the help of enunciationFootnote1, which concentrates on inspecting the interview discussion by questions such as whose perspective is being told and what is the relation between the narrator, their story and the people described in the story (Metsämuuronen, Citation2017). The analytic method follows the general process of qualitative data analysis, where the data is divided into smaller units, categorised and then grouped into relevant themes (Mills & Gay, Citation2016). This method was based on Alasuutari’s (Citation2011) three-part content analysis, and in the current study the parts were referred to as chopping, reducing and theming (see the example in ). The first and second authors read the transcripts several times and formed a large theme table of the participants’ comments. The table was utilised in the second phase of the analysis when responding to the research questions.

Table 1. The qualitative content analysis process.

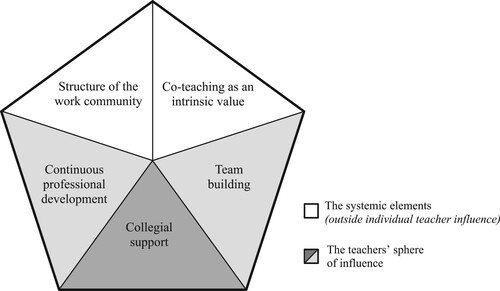

The theme table was separately examined according to each research question. With the first research question, five themes emerged: (1) collegial support, (2) team building, (3) continuous professional development, (4) structure of the work community, and (5) co-teaching as an intrinsic value. Two connecting arenas emerged from these themes, and they will be further discussed in the results with , which visualises the teachers’ perceptions of the features of co-teaching, as well as the relations between these perceptions. To answer the second research question, a framework with three main themes (individual, community and resource-specific challenges) emerged. These themes were further divided into subthemes, and they can also be found in the results.

Table 2. Main challenges regarding co-teaching.

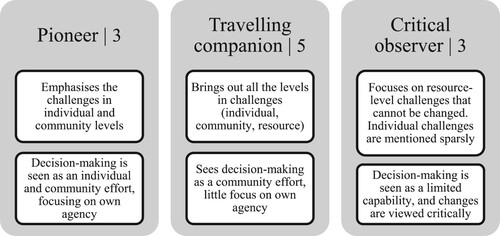

To answer the third research question, we identified three diverse educator profiles of influencing the decision-making when developing co-teaching. The profiles were constructed based on (1) the participants’ mentions of the challenges of co-teaching, (2) how they viewed decision-making, and (3) their own stated involvement in decision-making. After that, the first and second authors independently placed the participants into these types, and compared the consistency of the results. Their inter-reliability was 81% (nine out of eleven). One participant could not be placed into any of the roles because they did not discuss their own involvement in decision-making.

3.4. Ethical considerations

The research has been approved by University of Helsinki Ethical review board in Humanities and Social and Behavioural Sciences (Statement 20/2018, accepted 6.6.2018). The participants were provided with an informed consent form that they signed. Special care was taken to protect the research participants’ anonymity: all the interview quotes were referred to with pseudonyms. From now on, the participants will be referred to as educators to guarantee anonymity.

4. Results

The results were examined according to the research questions. We start with the educators’ views of the nature of co-teaching (first question), then address the challenges of the practical implementation of co-teaching (second question) and finally report the educator profiles in relation to their perceived influence within decision-making in their school community (third question).

4.1. Educators’ views on the nature of co-teaching: larger arenas forming the nature of co-teaching

Five themes emerged regarding the nature of co-teaching. These have been compiled and presented in . The nature of co-teaching emerged through the themes that reflected the aspects of co-teaching as a part of daily work. The themes were combined into two larger arenas: the teachers’ sphere of influence (coloured in grey) and the systemic elements (coloured in white). The teachers’ sphere of influence was seen to be within the teachers’ operating field and they had authority and influence over it. The arena consists of collegial support, teamwork and continuous professional development. The systemic elements -arena consists of institutional settings and beliefs that cannot be changed easily, thus being outside of influence. It consisted of two themes: the structure of the work community and co-teaching as an intrinsic value.

Collegial support provided additional resources for the individual teacher: having a partner reduced the workload significantly and gave the opportunity to test and share ideas, as well as plan, execute and evaluate teaching together. These were seen as promoting the quality of work and coping with the workload. Transparency and flexibility were seen as important features influencing the functionality of co-teaching. Most challenges were connected to the lack or deficiency of these features.

Continuous professional development included the development of both smaller decisions on everyday teaching and larger operating models around teaching and the school community. This ceaseless development was pictured as the foundation for a functioning work culture and, thus, an essential element of co-teaching. The development was also seen to play a major role in the success and usefulness of the school's operating culture and co-teaching.

P5: There are, you know, a lot of people who think alike, like most people want to plan and do things – but I know there are those who battle with this way of doing – but certainly people are also okay with not re-inventing the wheel every single day.

The last part included within the teachers’ influence was team building, which was seen as an inherent part of co-teaching because of the human nature of educational culture. Working closely with a partner can result in co-teachers forming close relationships outside of work. In co-teachership, personality and personal chemistry resurfaced more than in individual teaching, leading to educators wishing to have authority when creating co-teaching groups. The benefits of team building included utilising different strengths and academic knowledge to teaching by delegating certain lessons or activities to the more experienced one. At the same time, joint teaching could enable reciprocal observation and learning from colleagues. Furthermore, sharing and utilising teaching ideas and material was seen as beneficial for the whole school community. Even though team building was mostly portrayed in a positive setting, it also included a challenge regarding the induction and training of new colleagues. Co-teaching teams where the work experience varied greatly can become imbalanced, with the more experienced teacher becoming authoritarian.

The systemic elements of co-teaching included the structure of the work community, including the social structures and hierarchy of the school. In the context of co-teaching, this structure was revealed with the instructions, measures of support and expectations given to teachers by the school administration. Although co-teaching was carried out by co-teaching partners, the principal and rules around teaching were seen as having a great impact on how co-teaching can be executed.

P9: Well, there has been an attempt to create more structures from higher up and structurally. It certainly has to be done by people like ‘Hey, what do you wanna do together?’– I’ve been a bit confused like how it should be done because I thought in this school—I thought it would’ve been clear in the structures.

Co-teaching was seen as part of everyday life and teaching, but it also had a level of abstract value. Co-teaching as an intrinsic value was a part of the systemic elements and related to the seemingly unquestioned and assumed positive value of co-teaching. Unlike other parts, this was brought up by the challenges it created, e.g., building an identity as a co-teaching school and upholding it. The main dispute was with the gap between the advertised identity of the school and the real approach, as well as this identity losing its speciality because co-teaching has become more common as a teaching method.

Upholding this identity of co-teaching was challenging because of rapid changes within the work community. It took a lot of resources to train teachers who could possibly leave after the school year, thus creating a need for a new teacher to be trained. This constant change and training prevented the involved teachers from attaining the benefits of co-teaching. The educators also saw great differences between new teachers and those who had been longer in their work community and wanted the recruiting process to include co-teaching as one criterion when hiring new staff. Altogether, there was a prominent viewpoint that a school committed to co-teaching should be more cohesive in implementing such a work model for its teachers.

4.2. The challenges around the practical implementation of co-teaching

Three main themes arose when analysing the challenges of implementing co-teaching to answer the second research question: individual, community, and resource-specific challenges. Each main theme contained at least two subthemes. These themes are presented in , which also includes the categorisation and depiction of each main and subtheme.

Individual challenges were divided into two categories: personal and group challenges, with former including a perceived lack of competence and burnout under the workload. Group challenges focused on teamwork: co-teaching was deemed easier when personal chemistry was compatible, and the lack of it could lead to larger problems on everyday communications and teaching.

The themes around community challenges were divided into three subcategories: lack of sense of community, hierarchy and lack of leadership. The sense of community included the lack of feeling of working together, and educators making comparisons of classes. Hierarchy included experienced favouritism, i.e., not feeling as valued as others, and dividing cliques of old and new teachers. Lack of leadership entailed the need for clear leadership, such as distinct instructions on how to carry out co-teaching in practice. The lack of leadership was seen to lead to individual-level challenges, such as burnout.

Resource-specific challenges were situations that lead to co-teaching being diminished or changed. The resource was either tied to the structures of the workplace by incompatible teaching schedules, or not having the needed resources, e.g., computers, to implement planned lessons. In addition, the future structural changes to the school building caused fear and hope regarding the way it would affect their established methods of teaching.

4.3. Educators’ perceived capabilities in decision-making within their community

Finally, in the themes regarding the nature of co-teaching, continuous professional development emerged. The educators saw it as intertwined with co-teaching because it was the basis of the operating culture of their school. As a result, the educators highlighted many of their opportunities as influencing their decision-making because it would be reflected in their day-to-day work. Thus, we next open the views and levels of decision-making.

The educators had varied views on the way people can take part in decision-making within the school community. The problems and capabilities were divided into three levels: individual, community and resource levels. These levels are the same as the main themes regarding the challenges around co-teaching depicted in .

On individual level, educators pointed out their personal capabilities in decision-making, focusing on professionalism, and the guides and rules around co-teaching allowing adaptability for personal implementations in teaching. On this level, the principal was seen as an entity with elevated power who could enable or prevent these changes.

The community level had implications for working as a part of the co-teaching group and changes being made as a community. This part included the impact of the community itself based on the decision-making: an individual cannot overturn or deny a decision the whole community has decided on. The principal was seen as a factor in implementing these decisions into the school's everyday life.

P7: Obviously, it always goes with the principal because in the end they’re the pedagogical leader who makes it go forwards, but if someone's reluctant, it doesn't help if there's only one person trying something, they’ll just be running against the wall. So, I do think it starts with the work community as a group and then goes on. No one can make a group of thirty people change its course single-handedly.

These levels of decision-making and the involvement in developing co-teaching in the community were then compiled as three diverse educator profiles. The profiles were constructed based on (1) the educators’ mentions of the challenges of co-teaching, (2) how they viewed decision-making, and (3) their own stated involvement in decision-making. One educator could not be placed into any of the profiles because they did not discuss their own involvement in decision-making within their school community.

The three educator profiles are pioneers (N = 3), travelling companions (N = 5) and critical observers (N = 3). In , the levels of challenges the profile focuses on are described in the upper panel of the column, while the perceived influence on decision-making is described in the second panel.

Figure 3. Educator roles regarding the perceived influence on decision-making in their work community.

The pioneer is characterised by focusing on challenges on individual and community levels: they concentrate on the changes they can and have made within their own school. They emphasise idealistic executions and incorporate themselves into suggestions and implementations of change. The travelling companion brings out the challenges of their community at all levels. They acknowledge and address challenges equally, but do not volunteer to solve them personally. They want to participate in the changes, but do not focus on their own agency as much as the pioneer. The critical observer highlights resource challenges by focusing on the action of other people while individual challenges are mentioned in passing. Opportunities for change are addressed critically with awareness of the workload they bring.

These profiles can help depict the way the educators view their capabilities in taking part in the decision-making, and having insight on what kind of challenges they focus on. It is important to note that these roles fluctuate because of situational background, personal knowledge and experience.

5. Discussion

According to our results, the nature of co-teaching can be divided into two extended arenas depicting the educators’ work in an environment where their autonomy and level of decision-making capabilities are proportionate to the power relations in co-teaching and entire work community. These extended arenas are the teachers’ sphere of influence, where teachers can and will make changes, and the systemic elements, which are experienced to be beyond an individual's influence. They include five themes representing the educators’ view on the nature of co-teaching within their community. The systemic elements -arena includes the ideology of co-teaching and the structure of the work community. The latter was seen to strongly affect the educators’ experiences of co-teaching, especially with the need for collective planning time (Ahtiainen et al., Citation2011) and finding a suitable co-teaching partner (Sirkko et al., Citation2018, Citation2020). These were challenges that could not be resolved on their own.

The arena under teachers’ influence included collegial support, which was seen as relevant and a feature maintaining the benefits of co-teaching (Takala et al., Citation2020). The theme of team building had commonality with learning from the other teacher (Rytivaara & Kershner, Citation2012) and the positive effects on sharing teaching material, and creating a shared archive of knowledge (Rytivaara et al., Citation2019; Rytivaara & Kershner, Citation2012). The theme of continuous professional development's challenges can be tied to a feeling of losing control and trust (Morgan, Citation2016), which can hinder the implementation of co-teaching.

Three themes emerged when analysing the challenges to the practical implementation of co-teaching: individual, community and resource-specific challenges. The individual challenges were congruent with previous studies regarding personal chemistry (Sirkko et al., Citation2018), individual workload, exhaustion and burnout (Sirkko et al., Citation2020). Different views on co-teaching did not arise. At the community level, the need for leadership and guidance implied the need to discuss the joint purposes and objectives of co-teaching as a community (Ahtiainen et al., Citation2011). Resource-level challenges were in line with previous studies regarding planning and executing joint lessons (Ahtiainen et al., Citation2011), and scheduling collective planning time (Ahtiainen et al., Citation2011; Kokko et al., Citation2021).

The profiles regarding the influence in decision-making can be hard to distinguish in school settings because teachers in Finland generally avoid creating significant differences in the balance of power between personnel (Klassen et al., Citation2018). This could explain why more of the educators fit into the role of travelling companion rather than the other profiles. Critical observer's profile is congruent with the way Finnish schools are known to remain static because of teacher's autonomy (Niemi et al., Citation2018) and established routines that they want to uphold (Johnson, Citation2006). The educator types identified in the current study do not show how the educators implemented co-teaching in their everyday work lives. The profiles are also based on the answers given by one work community, so the possibility of a prevailing discourse in the community on co-teaching is probable.

Although three profiles of assumed roles were identified in this study, the underlying motives cannot be elaborated upon without further research. However, each profile is important for the community because a functioning work community needs both innovating pioneers and critical commentators, as well as travelling companions to process and decide on new changes in operating models. In this regard, the work community operates as its own micro-democracy, where the removal of any role creates an imbalance.

The current study has shown the multitude of factors that build co-teaching and how these two wider arenas are divided by the level of teachers’ capabilities to influence their work community and systemic elements, which cannot be changed without the whole work community. In addition, the challenges around co-teaching can be divided into individual, community and resource levels, and the way the educators discussed and focused on these challenges can bring out their involvement in decision-making when developing co-teaching as a work community. Awareness of these factors of co-teaching and the roles when it comes to developing co-teaching are useful for individual insight and allows to understand different views on co-teaching within a community.

The research on the extended factors building co-teaching should be expanded to several schools so that validation can be reached. This also applies to the educator profiles found in the current study. Examining the function of co-teaching at the school level and dividing the nature of co-teaching into larger arenas can help identify the challenges and amount of influence educators have when facing said challenges. Knowing these can help in determining the correct way to address and overcome these challenges as a community.

5.1. Limitations

Some limitations should be noted. First, all the interviewees were aware that the interviews would be utilised in school development work and as research data, which may have affected the transparency of their responses. However, the interviewees spoke openly about both the benefits and disadvantages of co-teaching and other practices in their school, giving the impression that they were not covering up their fundamental thoughts because of the research.

The second limitation regards the educator roles. One educator is not included as they did not mention their own perceived influence in their work community. The profiles includes both teachers and principals, whose job descriptions differ in the school community, thus having different viewpoints regarding making changes in the school community. Then again, the Decree on Qualification Requirements for Teaching Staff (2§, 14.12.Citation1998/986) in Finland has listed adequate work experience as a teacher as one of the requirements for the profession of principal. This still does not negate the difference in the work community. The clarity of the profiles may be affected by the fact that the willingness to involve different types of educators within the school was emphasised when gathering participants to the study. In addition, the profiles were identified by two researchers who, to reach inter-reliability within the profiles, independently placed educators into types and compared the results with each other.

Co-teaching is also a recognised tool for inclusive teaching. However, as schools deepen their inclusive practices, the need for co-teaching increases, and its implementation can include complex combinations of professional educators: class teachers, subject teachers and special education teachers. This multilevel intraschool collaboration can create novel and innovative practices, demand new structures and foster teachers’ professional development. Furthermore, inclusive teaching does not only mean taking care of pupils who need special support, but also supporting those pupils who can reach higher academic results than most of their peers. With co-teaching practices, teachers can combine their groups to support pupils in different learning phases. Finally, a future research area is studying how different kinds of learning spaces, especially flexible learning spaces (FLS), can support co-teaching or what kind of affordances FLS can give co-teaching practices. Further research that gives the school practitioners insights into what is working in practice and how different kinds of activity benefit pupils is needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Original term by Émile Benveniste (1966; as cited in Mosès, Citation2001).

References

- Ahtiainen, R., Beirad, M., Hautamäki, J., Hilasvuori, T., & Thuneberg, H. (2011). Samanaikaisopetus on mahdollisuus: Tutkimus Helsingin pilottikoulujen uudistuvasta opetuksesta [Team-teaching is an opportunity: A study of the renewed teaching in Helsinki pilot schools]. Publication series of Helsinki Education Department A1. The Education Department of Helsinki. Helsingin kaupungin opetusviraston julkaisusarja A1. Helsingin kaupungin opetusvirasto. https://docplayer.fi/6914-Samanaikaisopetus-on-mahdollisuus.html

- Alasuutari, P.. (2011). Laadullinen tutkimus 2.0 [Qualitative research 2.0] (Fourth edition). Vastapaino.

- Anderson, R. S., & Speck, B. W. (1998). “Oh what a difference a team makes”: Why team teaching makes a difference. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14(7), 671–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(98)00021-3

- Baeten, M., & Simons, M. (2014). Student teachers’ team teaching: Models, effects, and conditions for implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 41, 92–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.03.010

- Bauwens, J., Hourcade, J. J., & Friend, M. (1989). Cooperative teaching: A model for general and special education integration. Remedial and Special Education, 10(2), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258901000205

- Bovbjerg, K. M. (2006). Teams and collegiality in educational culture. European Educational Research Journal, 5(3–4), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2006.5.3.244

- Chitiyo, J. (2017). Challenges to the use of co-teaching by teachers. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 13(3), 55–66.

- Conderman, G., Bresnahan, V., & Pedersen, T. (2009). Purposeful co-teaching: Real cases and effective strategies. Corwin Press. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452219189

- Datnow, A. (2011). Collaboration and contrived collegiality: Revisiting Hargreaves in the age of accountability. Journal of Educational Change, 12(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-011-9154-1

- Decree on Qualification Requirements for Teaching Staff. [Asetus opetustoimen henkilöstön kelpoisuusvaatimuksista] 14.12.1998/986. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/1998/19980986

- Finnish National Board of Education. (2014). National core curriculum for basic education. Retrieved August 22, 2023, from https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf

- Fluijt, D., Bakker, C., & Struyf, E. (2016). Team-reflection: The missing link in co-teaching teams. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 31(2), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2015.1125690

- Friend, M., Cook, L., Hurley-Chamberlain, D., & Shamberger, C. (2010). Co-teaching: An illustration of the complexity of collaboration in special education. Journal of Educational & Psychological Consultation, 20(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474410903535380

- Friend, M., & Reising, M. (1993). Co-teaching: An overview of the past, a glimpse at the present, and considerations for the future. Preventing School Failure, 37(4), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.1993.9944611

- Guise, M., Habib, M., Thiessen, K., & Robbins, A. (2017). Continuum of co-teaching implementation: Moving from traditional student teaching to co-teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 66, 370–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.002

- Hargreaves, A., & O’Connor, M. T. (2018). Collaborative professionalism. When teaching together means learning for all. Corwin.

- Härkki, T., Vartiainen, H., Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P., & Hakkarainen, K. (2021). Co-teaching in non-linear projects: A contextualised model of co-teaching to support educational change. Teaching and Teacher Education, 97, 103188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103188

- James, M., McCormick, R., Black, P., Carmichael, P., Drummond, M.-J., Fox, A., MacBeath, J., Marshall, B., Pedder, D., Procter, R., Swaffield, S., Swann, J., & William, D. (2007). Improving learning how to learn: Classrooms, schools and networks. Routledge.

- Järvelä, S., & Hadwin, A. F. (2013). New frontiers: Regulating learning in CSCL. Educational Psychologist, 48(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2012.748006

- Johnson, P. (2006). Rakenteissa kiinni? Perusopetuksen yhtenäistämisprosessi kunnan kouluorganisaation muutoshaasteena [Stuck in structures? The process of unifying basic education as a challenge for change in municipal school organization]. University of Jyväskylä. Chydenius-instituutin tutkimuksia, 4/2006.

- Kelchtermans, G. (2006). Teacher collaboration and collegiality as workplace conditions. A review. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 52(2), 220–237. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:4454

- Klassen, R. M., Durksen, T. L., Hashmi, W. A., Kim, L. E., Longden, K., Metsäpelto, R.-L., Poikkeus, A.-M., & Györi, J. G. (2018). National context and teacher characteristics: Exploring the critical non-cognitive attributes of novice teachers in four countries. Teaching and Teacher Education, 72, 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.001

- Kohler-Evans, P. A. (2006). Co-teaching: How to make this marriage work in front of the kids. Education, 127(2), 260–264.

- Kokko, M., Takala, M., & Pihlaja, P. (2021). Finnish teachers’ views on co-teaching. British Journal of Special Education, 48(1), 112–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12348

- Kyrö-Ämmälä, O., & Arminen, K. (2020). Opettajia monenlaisille oppijoille – Inklusiivisia luokanopettajia kouluttamassa [Teachers for diverse learners – Training inclusive classroom teachers]. In M. Takala, A. Äikäs, & S. Lakkala (Eds.), Mahdoton inkluusio? Tunnista haasteet ja mahdollisuudet [Impossible inclusion? Identify challenges and opportunities] (pp. 73–104). PS-kustannus.

- Lehtinen, E., Hakkarainen, K., & Palonen, T. (2014). Understanding learning for the professions: How theories of learning explain coping with rapid change. In S. Billett, H. Gruber, & C. Harteis (Eds.), International handbook of research in professional practice-based learning (pp. 199–224). Springer.

- Little, J. W. (1990). The persistence of privacy: Autonomy and initiative in teachers’ professional relations. Teachers College Record, 91(4), 509–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146819009100403

- Metsämuuronen, J. (2017). Essentials of research methods in human sciences. Volume 1, elementary basics. Sage.

- Mills, G., & Gay, L. (2016). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and applications (Eleventh edition; Global edition). Pearson.

- Morgan, J. (2016). Reshaping the role of a special educator into a collaborative learning specialist. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 12(1), 40–60.

- Mosès, S. (2001). Émile Benveniste and the linguistics of dialogue. Revue de métaphysique et de morale, 32(4), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.3917/rmm.014.0509

- Nevin, A., Thousand, J. S., & Villa, R. A. (2009). Collaborative teaching for teacher educators: What does the research say? Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(4), 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.009

- Niemi, H., Lavonen, J., Kallioniemi, A., & Toom, A. (2018). The role of teachers in the Finnish educational system: High professional autonomy and responsibility. In H. Niemi, A. Toom, A. Kallioniemi, & J. Lavonen (Eds.), The teacher’s role in the changing globalizing world: Resources and challenges related to the professional work of teaching (pp. 47–61). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004372573_004

- Pesonen, H., Rytivaara, A., Palmu, I., & Wallin, A. (2021). Teachers’ stories on sense of belonging in co-teaching relationship. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 65(3), 425–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1705902

- Pratt, S. (2014). Achieving symbiosis: Working through challenges found in co-teaching to achieve effective co-teaching relationships. Teacher and Teacher Education, 41, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.02.006

- Ronfeldt, M. (2017). Better collaboration, better teaching. In E. Quintero (Ed.), Teaching in context. The social side of education reform (pp. 71–93). Harvard Education Press.

- Roth, W.-M., & Tobin, K. (2002). At the elbow of another. Peter Lang.

- Rytivaara, A., & Kershner, R. (2012). Co-teaching as a context for teacher’s professional learning and joint knowledge construction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(7), 999–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.05.006

- Rytivaara, A., Pulkkinen, J., & de Bruin, C. (2019). Committing, engaging and negotiating: Teachers’ stories about creating shared spaces for co-teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 83, 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.04.013

- Saloviita, T., & Takala, M. (2010). Frequency of co-teaching in different teacher categories. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 25(4), 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2010.513546

- Sawyer, R. (2006). Educating for innovation. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 1(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2005.08.001

- Scruggs, T. E., Mastropieri, M. A., & McDuffie, K. A. (2007). Co-teaching in inclusive classrooms: A metasynthesis of qualitative research. Exceptional Children, 73(4), 392–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290707300401

- Sirkko, R., Takala, M., & Muukkonen, H. (2020). Yksin opettamisesta yhdessä opettamiseen: Onnistunut yhteisopettajuus inkluusion tukena [From teaching alone to teaching together: Successful co-teaching in support of inclusion]. Kasvatus & Aika, 14(1), 26–43. https://doi.org/10.33350/ka.79918

- Sirkko, R., Takala, M., & Wickman, K. (2018). Co-teaching in northern rural Finnish schools. Education in the North, 25(1–2), 217–237. https://doi.org/10.26203/hxx9-kr24

- Takala, M., & Saarinen, M. (2020). Opettajan toimijuus muutoksessa – yhteisopetusta pienin askelin [Teacher’s agency at a turn - Co-teaching in small steps]. Työelämän Tutkimus, 13(3), 232–244. https://doi.org/10.37455/tt.97976

- Takala, M., Sirkko, R., & Kokko, M. (2020). Yhteisopetus ‒ yksi mahdollisuus toteuttaa inklusiivista kasvatusta [One prospect to implement inclusive education]. In M. Takala, A. Äikäs, & S. Lakkala (Eds.), Mahdoton inkluusio? Tunnista haasteet ja mahdollisuudet [Impossible inclusion? Identify challenges and opportunities] (pp. 139–158). PS-kustannus.

- Thousand, J. S., Villa, R. A., & Nevin, A. I. (2006). The many faces of collaborative planning and teaching. Theory Into Practice, 45(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4503_6

- Vangrieken, K., Dochy, F., Raes, E., & Kyndt, E. (2015). Teacher collaboration: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 15, 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.04.002

- Walther-Thomas, C. S. (1997). Co-teaching experiences: The benefits and problems that teachers and principals report over time. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 30(4), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221949703000406

- White, C. S., Henley, J. A., & Brabston, M. E. (1998). To team teach or not to team teach—That is the question: A faculty perspective. Marketing Education Review, 8(3), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.1998.11488640