ABSTRACT

This study examines how researchers and practitioners navigate between different discourses in a large-scale research-practice partnership (RPP). While argued to be challenging to conduct, RPPs are also argued to be promising for closing the research-practice gap in education. To contribute to our understanding of RPPs, 45 h of video recorded interactions between researchers and practitioners in a large scale RPP including 300 participants are analyzed. Through a discourse analysis, the presence of two discourses is identified: (1) an outcome-oriented discourse that aligns with traditional positions and division of labour, and (2) a process-oriented discourse that aligns with collaborative and less hierarchical positions. Explanations for the results are discussed in relation to didactic and curriculum traditions, as well as resource management and task distribution. Moreover, it is argued that, while the negotiation of discourses is necessary to avoid hegemony, the negotiation also produces ambiguous participant identities in the RPP.

Introduction

Education research and practice have traditionally been separated by a top-down structure that limits practitioners’ influence (Penuel et al., Citation2020; Tseng et al., Citation2018). To overcome this gap, researchers and stakeholders are increasingly engaging in research-practice partnerships (RPPs) that aim to empower and emancipate educational practitioners (Farrell et al., Citation2021; Tseng et al., Citation2017; Wentworth et al., Citation2021). However, RPPs also entail challenges, such as navigating authority structures and becoming aware of the discourses that shape them (Farrell et al., Citation2018, Citation2019). A recent literature review (Sjölund et al., Citation2022a) identified different approaches to collaboration in RPPs and how they affect the distribution of authority between researchers and practitioners. Moreover, these approaches are varyingly appropriate depending on, for instance, the context and competence of the participants. However, as positioning, identityFootnote1 and authority structures exist within and in relation to discourses, there is also a need to understand the discourses at play in RPPs (Fairclough, Citation2013). In light of this, recent efforts to create frameworks to understand RPPs have highlighted the need to consider factors such as discourses as well as sociocultural and political tensions that influence RPP work (Yamashiro et al., Citation2023). While there a few studies have investigated how practitioner and researcher collaboration is related to discourses (Chan & Clarke, Citation2014; Farrell et al., Citation2019), more research on how discourses and positioning depend on each other in RPPs is needed if we are to understand how discourses can affect RPP work. Moreover, we need opportunities to gain insights into the interactions between researchers and practitioners from an outside perspective (i.e., researcher not directly affiliated with the programme itself), which is rare in the research on RPPs (Coburn & Penuel, Citation2016).

To extend our understanding of RPPs and address the gap in knowledge regarding discourses and positioning, the present study adopts a discourse analytical approach to examine video recorded interactions of researchers and practitioners in a large-scale RPP in Sweden with over 300 participants. The aim of the study is threefold in that it investigates (1) the discourses at play in an RPP, (2) researcher and practitioner positions as related to discourses, and (3) how the discourses and positions are negotiated in the RPP. Lastly, possible explanations for the presence of the specific discourses and their relation to certain positions will be discussed.

Educational context and teacher autonomy

The Organization for Educational Co-operation and Development (OECD) is a central figure in the discussion on research and development in education. Based on reviews (OECD, Citation2003, Citation2004a, Citation2004b) of several countries’ research and development systems, it has argued for reforms in line with the development practices of evidence-based medicine. “Evidence-based practice” has also been argued to be the product of the demand from new public management to use taxpayers’ money as efficiently as possible (Hargreaves & Shirley, Citation2010). In, for instance, the U.S. and England, this has created a curriculum tradition of schooling, focusing on students’ learning of content. This is accompanied by a high degree of control through a detailed and decentralized curriculum (Hudson, Citation2007). Following this logic, it is important to know what works and what does not, hence the need for evidence that schools and teachers are doing the right things (Hammersley, Citation2001). In the Swedish context of the present study, however, the research and development structure has mainly been influenced by a Nordic and continental tradition (Levinsson, Citation2013; SOU, Citation1992:Citation94).

This Nordic and continental didactic tradition is characterized by a general state curriculum. This gives teachers more autonomy in terms of organizing teaching and learning as compared to the Anglo-Saxon curriculum tradition (Hudson, Citation2007). As a result, the two traditions place the teachers in different roles. The didactic tradition places the teacher at the centre of teaching and learning, with fewer frames around how to do their work. The didactic tradition can be said to have a process evaluation system with high teacher autonomy as well as a centralized curriculum that encourages teacher reflection on teaching and learning (Wermke & Höstfält, Citation2014). In contrast, the curriculum tradition positions teachers more as invisible agents of a detailed curriculum, which indicates that they are directed by the system to a larger degree. The curriculum tradition can be described as built on product evaluation with relatively low teacher autonomy. These differences set the foundation of the perspectives and prerequisites that teachers go into collaborations such as RPPs. As such it is pertinent to have this background when investigating discourses of collaboration and positioning in RPPs.

Shedding further light on teacher positioning in the Swedish context, one study (Wermke, Citation2011) compared continuous professional development cultures in Germany and Sweden, both of which are based on a didactic tradition. In this study they found that Sweden had a relatively “modern” state curriculum focusing on competences, providing weak directions to teachers. In contrast, the German curriculum is more traditional, and content focused and, relative to Sweden, has a state curriculum that provides stronger directives. As a result, enhanced by strong accountability measures (Ryve & Hemmi, Citation2019), teachers in Sweden were more insecure than German teachers, and as such, sought more guidance from outside actors, such as universities, for professional development. The German teachers, instead, were relatively confident and relied more on colleagues for professional development. Another study (Ryve & Hemmi, Citation2019) similarly argued that the Swedish context provide autonomous position for teachers on a policy level. However, Swedish teachers’ positioning in the classroom is instead reactive and passive in terms of, for instance, setting goals and orchestrating instruction. This further enhances the image of the autonomous but insecure Swedish teacher.

Research on research-practice partnerships

Research suggests that we should move towards more collaborative ways of integrating evidence into education (Farrell et al., Citation2022; Tseng et al., Citation2018). Specifically, RPPs have been identified as promising for closing the research-practice gap in education. RPPs can be briefly described as long-term, mutualistic partnerships invested in educational improvement and equity. One study (Honig et al., Citation2014) investigating research-based change efforts in education found that teachers and school leaders need help in shifting established practices if the change is to happen at a deeper level. However, as context and capabilities vary, some teachers, school leaders and researchers might be varyingly open to or capable of learning from collaboration partners. Hence, there is research suggesting that it is important to be able to adapt RPPs to match the local context and capabilities (Sjölund et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b).

However, while RPPs are argued to be promising for closing the research-practice gap in education, engaging in RPPs also comes with challenges. For instance, challenges have been identified related to funding for long-term sustainability (Rivera & Chun, Citation2023), stakeholder engagement (Akkerman & Bruining, Citation2016), the lack of a common language (Coburn & Penuel, Citation2016), and social dynamics such as trust, authority and status (Farrell et al., Citation2019). Moreover, previous studies have investigated the roles of participants in RPPs, finding a variety of different roles based on task distribution (Sjölund et al., Citation2022a) or participant focus and tasks (Mull & Adams, Citation2017). Another key aspect and challenge of the social dynamics of RPPs is to involve diverse stakeholders with an equitable authority structure (Coburn et al., Citation2008). Some researchers have argued that we need to give more authority and power to practitioners to create more equitable evidence-generating structures (Penuel et al., Citation2020; Tseng et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). However, there are those who contend that practitioners have more power and influence than universities in the current context of research and improvement (Breault, Citation2014). In an effort to organize our collective understanding of RPPs, Farrell et al. (Citation2022) proposed a framework that addresses how partner organizations work at the boundary between research and practice to achieve intermediate and long-term outcomes. However, other scholars (Yamashiro et al., Citation2023) have argued that the framework should be embedded in a larger context, which surfaces the political and sociocultural tensions. While this argument tries to highlight the larger context in which RPPs are embedded, discourse, identity and positioning are still underexplored in efforts to understand RPP work.

However, some scholars have investigated the relationship between discourse, positioning and identity in RPPs (Chan & Clarke, Citation2014; Farrell et al., Citation2019). For example, one study (Farrell et al., Citation2019) explored role and identity negotiation in RPPs using identity-referencing discourse, highlighting the link between discourse and identity. Another study argued that identities are not fixed throughout RPPs, but are instead renegotiated continuously (Chan & Clarke, Citation2014). Moreover, these identities are negotiated within and against discourses, which is a highly complex process. The researcher in a school-based action research programme, for instance, wrestled with balancing an identity as an expert and authoritative group leader with an identity as a caring, supportive and democratic facilitator (Chan & Clarke, Citation2014). A teacher in the programme rejected the project’s attempts to identify her as a co-researcher and consistently returned to the classroom teacher identity. In cases like this, when roles become unclear, there is a risk that RPP efforts will stall (Farrell et al., Citation2019). However, if participants in an RPP manage to successfully renegotiate roles, the collaboration can move forward again, with more stable authority structures in place (Coburn et al., Citation2008).

To conclude, the small body of literature on discourses, positioning and identity in RPPs has demonstrated the importance of understanding how discourse and identity are related to each other (Chan & Clarke, Citation2014; Farrell et al., Citation2019). Moreover, this is an important aspect if we are to advance our understanding of RPPs in general (Farrell et al., Citation2022; Yamashiro et al., Citation2023). In the present study, I aim to extend our knowledge of discourses and positioning in RPPs by offering an in-depth discourse analysis of naturally occurring data collected in a large-scale RPP.

Theory

In the present study, I investigate meetings between school leaders, researchers, and institute representatives. I conceptualize this data as discourses of RPPs in a preschool setting. Discourse is understood broadly as ways of representing aspects of the world (Fairclough, Citation2003) concerning “talk and texts as parts of social practices" (Potter, Citation1996, p. 105). Further, I am interested in the positioning and identities of researchers and practitioners related to discourses. In the study, identities are described as being more continuous and stable than positioning, which is momentary (Davies & Harré, Citation1990). As such, an individual can be specifically positioned in a single utterance, while an identity is something that necessarily exists over time. To operationalize these concepts, I will track and investigate the momentary positioning of participants to be able to discuss participants’ more continuous identities.

Important to note is that, while I adopt the perspective that discourses are a constitutive force, I also recognize that individuals have the agency to exercise choice in relation to these discourses. In other words, positions as well are not infinitely fixed but are constituted and reconstituted by participating and making choices in relation to various discursive practices. How one is positioned at any given time can vary depending on the choices made in relation to the subject positions that are available. Positions, as such, can be chosen for a person by others or the context in which they take part, however, an individual can reject one position in favour of another, and as such practice has influence over the formation of an identity. In essence, positioning statements can be acts of either self-positioning or positioning others.

Based on the description above, the discourse analytical approach allows me to investigate both how discourses of collaboration in RPPs are characterized as a part of that process and the positioning of practitioners and researchers. To identify and characterize discourses, I utilize a linguistic discourse analysis mainly focused on the semantic relationship between words. To identify participant positioning, I investigated passages where participants argued for or against a certain way of doing or meaning making. A more in-depth explanation of how concepts are used in the present study will be provided in the analysis section.

Method

In this section, I will first provide some insights into the Swedish preschool context. This will help me explain and contextualize, and as such increase the transferability of the discourses and positions identified in my analysis. Second, I will provide a description of the RPP under study before moving on to data collection and analysis, further explaining the context of the study. I will conclude the methods section by describing the limitations of the study, most of them related to the effects of the pandemic.

Swedish preschool context

Preschools in Sweden are either operated by the municipality in which they are located or by a private school authority. Swedish children attending preschool are typically between 1 and 5 years old, with an attendance rate of 83% (Nygård, Citation2020). When they turn 6, they commence a preschool grade before entering compulsory education. The Preschool Teacher Program spans 3,5 years, and as of 2016, approximately 39% of all preschool teachers in Sweden had completed this programme (Skolverket, Citation2018). Additionally, around 20% of employed preschool teachers held an upper-secondary degree in child education, while another 10% had undergone some form of teacher education training, such as starting a preschool teacher programme but not completing it. In recent years, the position of preschool teachers in Sweden has evolved, aligning more closely with that of teachers in compulsory schools, due to recent reforms emphasizing the role of preschools as preparation for compulsory education (Berg, Citation2022). Notably, the inclusion of the term “teaching” in the state preschool curriculum in 2018 serves as a clear indicator of how preschool teachers are increasingly being positioned more like compulsory educators.

The programme

The case programme investigated in this study is an RPP that could be characterized as a networked improvement community (NIC; Coburn et al., Citation2013), as it is a long-term effort organized around a cyclic process of inquiry in networked groups of professional learning communities (PLCs). The programme was initiated and is mainly funded by an organizing non-profit independent research and improvement institute. This institute is funded by its member municipalities and private school authorities. When this programme was in its inception, three researchers were tied to the programme and one university decided to co-fund the programme. Concurrently, the researchers and programme board invited me to be an observing researcher focusing in investigating the RPP itself. The programme launched in early autumn 2021, and is funded for an initial three years, with a possible extension depending on researcher and practitioner engagement. The general purpose of the programme is developing long-term and research-based ways of working, so that preschools develop work within the area of sustainable development with the purpose of strengthening children’s learning and development.

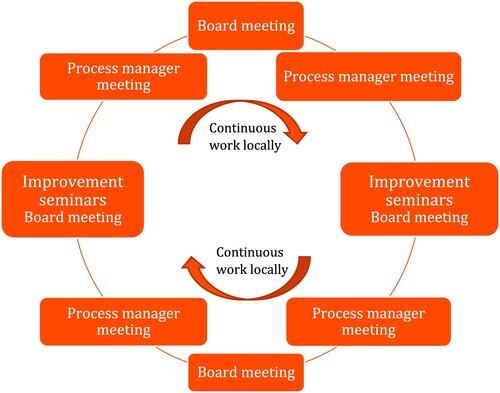

Three types of organizational entities are involved: academia (i.e., researchers), educational practice (e.g., preschool teachers, principals, and district office employees) and a non-profit independent research and improvement institute that works to stimulate practice-oriented research in the field of education. The institute is funded by its members, which are municipal and private school authorities. Among other things, they facilitate collaborative research and improvement programmes, which are run by a board elected (consisting of both practice and academy representatives) by participants in the programme. This programme, described in more detail below, is spread across several cities and regions in Sweden. It is a large-scale programme in terms of number of participants and its geographic coverage in Sweden, including 300 educational practitioners, three researchers, and one institute representative with responsibility for programme coordination. The board is collectively in charge of the programme budget. The programme organization is illustrated below ().

The programme board constitutes preschool and municipal leaders, a representative from the research group and an institute representative. A representative from practice is always chosen as chair of the board. The programme board is a policy and decision-making body. The process manager group mainly consists of preschool leaders, as well as one institute representative and representatives from the research group. The process manager group is an operations and implementation body, constituting those in charge of leading the local improvement groups. At board meetings and process manager meetings, practical issues, plans for research and improvement as well as improvement seminars are discussed. Each municipality or private school authority has at least one representative at both the programme board and the process manager group. These representatives then lead the respective local boards. Similarly, the people on the local board are in charge of one improvement group each, and the groups are in charge of the local improvement work.

To get more clarity on how the programme unfolds over time in a cyclic process, I will complement with another illustration of a yearly cycle ().

Data

To gather data relevant to addressing the study aims, I conducted video-recorded observations. First however, an ethics process of ethical vetting, missives and consent forms for the programme were administered and completed successfully. Two types of meetings involving preschool leaders, researchers and an institute representative were observed: board meetings (policy/decision-making body) and process manager meetings (operations/implementation body). illustrate the properties of recorded and transcribed material to be analyzed, which was collected in a period from August 2021 to December 2022, constituting the first half of the planned programme tide.

Table 1. Properties of data.

These data were recorded during COVID-19, the global pandemic, and as such the data were mostly recorded from online meetings conducted via Zoom. Despite this, such data allow us to gain insights into the interactions between researchers and practitioners in natural data from an outside perspective, which is rare in research on RPPs (Coburn & Penuel, Citation2016).

Analysis

The analysis was carried out in three phases. The first phase was informed by content analysis, which involves classifying the data into more manageable parts (Weber, Citation1990). The second and main phase of the analysis process was a linguistic discourse analysis (Fairclough, Citation2003, Citation2013). The third phase was a more general discourse analysis, focusing on finding implicit structures related to the participant positioning. Throughout these three phases, in relation to both discourses and positioning, the aim was to (1) identify existing ones, (2) characterize them, and (3) describe how they are negotiated.

The first phase of analysis involved reading the full transcripts and familiarizing myself with the data. While doing this, I commenced a phase of iterative and explorative content analysis (Weber, Citation1990), identifying and coding specific parts of the data that seemed relevant to investigating discourses of collaboration in the programme. With each iteration of analysis, I tried to reduce the number of nodes (i.e., codes) by grouping nodes with similar content into sets. For instance, the nodes “Researchers tell what research says” and “Researchers challenge with alternate perspectives”, along with several other nodes, created a set called “Researchers provide input”. When the sets were saturated and no new sets were created, the iterative process ended and I moved on to an in-depth discourse analysis of the different sets of nodes.

For the second phase, I utilized linguistic-focused discourse analysis, to identify and characterize discourses present in the programme. Hence, to analyze the transcribed material, I investigated how discourses are realized in different textual properties (e.g., vocabulary like pronouns as well as grammar). The general approach to the linguistic discourse analysis (Fairclough, Citation2003) in this study can be described as not only focusing on specific words but more importantly on the semantic relationships between them. For instance, several participants identified the programme as a process and not an education. As such, a “positive” relationship was established between the word “programme” and the word “process”, and a “negative” relationship between “programme” and education. Semantic relations such as these are key to identifying different perspectives on the world (i.e., discourses; Fairclough, Citation2003). These semantic relationships between words can be divided into three different ways of making meaning. First, meanings can be identified (synonymy) by addressing the overarching character of collaboration. For instance, the institute representative identified the programme as an interactive research programme. Second, meanings can be included (hyponymy) by addressing different elements of collaboration. For instance, the institute representative included open dialogue across organizations in the meaning of the programme. Third, meanings can be excluded (antonymy). For instance, the institute representative excluded the idea of only presenting results and receiving feedback in an interactive research programme such as this.

Lastly, I initiated a third phase focusing on researcher and practitioner positions. This was done by tracking momentary participant positioning when they argued for or against certain ways of doing or meaning-making regarding different aspects of the programme. For instance, when a preschool leader argued that researchers should be involved in group discussions by challenging school leaders, they meant that researchers should be positioned as critical research partners to preschool leaders in the programme. In this way, I could analyze how the participants in the programme positioned themselves in relation to the different discourses. Moreover, when a participant takes a subject position, it is related to a discursive practice and a specific perspective on the world (Davies & Harré, Citation1990). As such, through a series of positions, one can see patterns that reflect views of the programme in specific story lines or narratives. In the present analysis, these narratives were used to identify how the sequence of positions are connected to discourses. Specifically, in terms of proximity to each other, sequences of positioning and discourses were connected in a narrative. The second and third phase were repeated until the categories were saturated and the discourses and positions were stable.

Limitations

The limitations of the present study are mostly due to the global pandemic existing at the time. First, the data collected are primarily limited to an online format, where Zoom was used for meetings and seminars. This influenced the programme as a whole, which was stressed by the participants themselves at times, and is worth considering regarding the transferability of the results. Further, it could be interesting for future research to investigate the differences between online and in-person programmes, comparing the results of the present study to similar programmes based on in-person meetings.

Moreover, because I relied on meetings between school leaders and researchers (board and process manager meetings), I obtained no first-hand accounts from preschool teachers. For preschool teachers’ perspectives, I relied on second-hand information derived from what preschool leaders said their preschool teachers had mentioned and thought about certain aspects of the programme. In large-scale programmes such as this, with over 200 preschool teachers, for practical reasons it is rare for researchers and preschool teachers to engage in an extended dialogue. However, to investigate preschool teachers’ perspectives on collaboration more deeply, future studies on more small-scale RPPs might want to specifically aim to collect data when preschool teachers and researchers meet and to engage in dialogue with preschool teachers.

Results

Through discourse analysis, two overarching discourses, with related positions for programme participants, were identified. An overview of the results can be seen in .

Table 2. Overview of discourses and positions.

When describing the results, I follow the structure of , dividing the results into two overarching sections describing the two discourses. The two sections constitute in-depth descriptions of the respective discourses and the momentary positions they include. I conclude each discourse section with a summary of key aspects. Lastly, I also provide a more fine-grained description of how the discourses and positions were negotiated in the programme.

Outcome-oriented discourse

As the heading “outcome-oriented discourse” indicates, this section will characterize a discourse that sees collaboration as a “means” of reaching outcomes or goals. This is largely centred on a narrative concerning how to conduct and disseminate research in the programme, as well as on narratives regarding the relationship between researchers and preschool leaders. First, in a discussion on how data collected in the programme should be used, a clear distinction is made between the research and improvement efforts. This distinction was described by both researchers and preschool leaders, which can be seen in the quotes below.

The observation protocol results stay in your preschool. We are interested in the summarized results and then it is the three areas you have rated the highest in your team … . And this you own as process leaders and principals and you are responsible for what to do with it. On the other hand, when you have considered, well … what was it that we rated the highest and why did we do that? Then you have a reflective text that we think is really good as research data. (Researcher)

… What we do with our answers, we are responsible for that, because that’s what we collect for our local improvement work. That has nothing to do with the research programme or that part of what we do. (Preschool leader)

Participants are also positioned in the narrative on dissemination of conducted research, which emerged in a process manager meeting following an improvement seminar. During this process manager meeting, researchers and preschool leaders discussed how researchers disseminate research findings at improvement seminars, and preschool leaders argued that:

There is an expectation about what researchers will contribute and that you … sometimes there is an expectation that you will get all the answers. Now you will find out if what you do is correct or not. And that this can be part of it and you kind of think that successively this will change and that you will see that what researchers do in this case can contribute, very much asking more questions and cooperating in asking more questions. (Preschool leader)

However, I think it’s important to mention that there may be some teachers who think that now they (the researchers) will tell us how it is. However, we are supposed to teach you to do research on this together, create knowledge that is important to raise. (Preschool leader)

In the same way as was said earlier, that it might not have been a very in-depth analysis of the results that has been delivered so far. It also provides space for the groups, just as I understood that Iris (researcher) was talking about, to reflect themselves without someone else shoving the answers down their throats in some way. (Researcher)

An outcome-oriented discourse was not only present in narratives related to the research conducted in the programme. For instance, in a discussion on preschool teachers’ pedagogical approaches at a process manager meeting, one preschool leader expressed frustration with current collaboration practices between researchers and school leaders in the programme.

Yes, but I hope we will get into these reflective questions, so that I hope we don’t just close the lid, which I kind of experience right now, and also this language dilemma that’s been raised from several directions and also so that it doesn’t just become … then we’re on the wrong path, or then you just have to solve it. I mean, I think that if these are real questions and dilemmas that arise and if we are actually to be collaborators and shape this programme in different ways, I think this is important. That we, who are in practice, are also taken seriously. That you can talk about this in different ways. (Preschool leader)

Summary outcome-oriented discourse

Collaboration identified as a means to achieve a common goal

The outcome-oriented discourse portrays collaboration as a tool or strategy that individuals or groups use to achieve objectives. The emphasis is on the outcome of the collaboration and how it benefits everyone involved. This discourse highlights the benefits of collaboration, such as access to data for research and improvement as well as access to each other’s expertise to achieve programme goals. Moreover, there is a friction regarding the negotiation of discourses, where preschool leaders and researchers argued more in line with a process-oriented discourse, whereas preschool-teachers seemed to draw more from an outcome-oriented discourse. However, researchers and preschool leaders also drew on the outcome-oriented discourse when they spoke about using data for their respective goals.

The narrative related to the outcome-oriented discourse also included positioning of participants, which highlighted emerging positions. In this narrative, researchers were seen as scientific experts, preschool teachers as local implementers/interpreters, and preschool leaders as improvement leaders. Importantly, participants did not seem to assign the same ideal position to preschool teachers, preschool leaders, and researchers. For instance, preschool teachers identified themselves as implementers, and as such resisting the efforts of both preschool leaders and researchers in positioning them as interpreters.

Process-oriented discourse

This section will provide an in-depth description of the process-oriented discourse, which entails a perspective that views collaboration as a process of mutual learning and growth based on equitable discussion. In the present study, the process-oriented discourse was largely centred on a narrative concerning the interaction and communication between participants. For instance, when discussing expectations of the different roles of participants in the programme (a recurring topic at board and process manager meetings), one preschool leader emphasized the need for more discussions with researchers aimed at broadening perspectives.

We can pitch in here, also that we get the researchers into our groups to broaden our perspectives kind of based on, yeah, well, theories, methods, provide input, challenge also a bit because I think as a process leader you have a role in that when you get back home to your local preschool and start working. We were very much in the ‘how’ and not so much in the ‘what’ perhaps, but the ‘how’ and that we give each other input, but also do it based on the theories that exist. That we can relate to the research more clearly and broaden our perspectives, right, Sandra and Anna, you have to, kind of, fill in here. (Preschool leader)

Yes, but I think that this to, kind of, that the researcher and we (Preschool leaders) kind of, should challenge each other. We (Preschool leaders) have knowledge about what happens in practice, and research is what we might not always have time to learn about, and to, in different ways, dare to create amazement and curiosity in each other, in dialogue. (Preschool leader)

But also that it’s supposed to be an exchange of experiences, where the researchers, just as you sit here, Emma is in the board meetings. So that we have this continuous dialogue in this triangle, researchers, the board, and the institute. (Preschool leader)

But then, that this documentation after lunch should be a foundation to be able to highlight some things that came up in these discussions in the groups with the researchers, so that it doesn’t just end up with researchers standing there telling how it is and then we (practitioners) get to talk and then that’s the end. Instead, that it actually … should feel like it also becomes a collaboration, that the discussions are also food for thought for the research group. So, my hope is that it will be perceived as the start of a conversation with the research group, I would say. (Institute representative)

Yes, this is a little, to raise that we really … with a programme and that you (preschool teacher) need to be active as a participant, and that we, together, make this programme into what it becomes and that we learn from each other. And that you really need to do that and stress it often and it’s not … we will get there and will gain knowledge, but it’s something we create together. (Preschool leader)

Summary process-oriented discourse

Collaboration identified as a process of mutual learning and growth

The process-oriented discourse, through a narrative on communication and interaction between participants, entails the view that collaboration is a relationship in which individuals or groups learn from and with one another. The emphasis is on the learning and growth that take place during the collaboration, rather than just on the outcome. This discourse often highlights the importance of equitable engagement in the form of open communication, discussion, and dialogue in order to challenge perspectives and grow, as well as the ability to handle conflicts within the group in order to foster a positive collaborative experience.

Positions found in the narrative reflecting a process-oriented discourse on collaboration were researchers as critical partners, preschool leaders as practice partners and preschool teachers as local inquirers.

Negotiation of discourses and positions

To introduce this section, the results show that both the outcome-oriented and the process-oriented discourses are necessary to make progress towards programme goals while still emphasizing the importance of mutual learning and growth. What was negotiated here is the balance between the two discourses and the related positions. Moreover, both discourses and positions were negotiated throughout the dataset. In the present study, the fact that discourses are negotiated is used to denote how programme participants drew from different discourses when arguing for one perspective or another. It also occurred that the same participant drew from more than one discourse simultaneously. An example of this is when a preschool leader questioned researchers choosing certain tasks based on what gives them good data.

No, but I think, two things, if you go back to participation as Sandra (School leader) talked about. Because I think that this is what it’s about … Of course, the research group should collect their data. But we think we’re supposed to have research and we’re supposed to have learning for all participants who should develop their knowledge and if we’re supposed to find the intersections in that, to be able to lead the process, then we need space to talk about this. Because you see one picture of … well … kind of this is something we can work with more, and I think we want to have the opportunity to trial-think this together, in this forum (Process manager meetings) to kind of see … can we twist this a little. We think that it, perhaps, would be received better if we think like this … based on the knowledge from practice that we possess and knowledge based on this research and theoretical, so I think that this is perhaps a little gap, that it’s probably not a lack of, but instead it’s more about how we meet to develop together. (Preschool leader)

Another type of negotiation that occurred in the programme was an adjustment to have a less outcome-oriented focus and a more process-oriented focus. Specifically, as indicated in the data, the programme was too reliant on an outcome-oriented discourse, and efforts were made to renegotiate practices to draw more from a process-oriented discourse. For instance, one preschool leader argued that the programme had, on several occasions, closed the lid on important dilemmas found in practice, and that because of this, the open communication concerning practice-based dilemmas had been limited. The preschool leader argued that, moving forward, more focus and time should be dedicated to discussing practice-based dilemmas. This is a clear indicator that the preschool leader wanted to renegotiate the discourses of the programme to bring them more in line with a process-oriented discourse. Similarly, preschool leaders argued that researchers should take part in their group discussions, thus allowing researchers and preschool leaders to learn more from each other and experience mutual growth. This is also a case of trying to renegotiate the practices of the programme to bring it more in line with a process-oriented discourse. As an effect of these negotiations, the positioning of both researchers and practitioners was also renegotiated, as researchers would move from being research experts to more critical research partners, and preschool leaders would move from being improvement leaders to critical practice partners.

Preschool teachers, on the other hand, rejected authority in the form of interpretation and reflection on the data, instead adopting a more passive stance in relation to the programme and identifying themselves as teacher implementers. Through a statement of both self-positioning and positioning of others, they negotiated in favour of positions related to the narrative of the outcome-oriented discourse, asking researchers to give more clear directions based on their research. This would, contrary to researchers’ and preschool leaders’ perspective, result in positioning researchers as research experts.

Overall, the negotiation observed in this programme primarily concerned trying to change inherently outcome-oriented practices and positions into more process-oriented practices and positions. The exception here was preschool teachers, who were explicit about preferring more governance from researchers as research experts and who, as such, drew on positions in the narrative related to the outcome-oriented discourse.

Discussion

Summarizing the results, I have identified and characterized the presence and negotiation of two discourses with related positions for participants in the RPP. First, the outcome-oriented discourse, which views collaboration as a means to achieve a common goal, positions researchers as scientific experts, preschool leaders as improvement leaders, and preschool teachers as implementers/interpreters. Second, the process-oriented discourse, which views collaboration as a process of mutual learning and growth, positions researchers as critical partners, preschool leaders as practice partners, and preschool teachers as local inquirers.

In the following section, I will first try to explain the results in relation to the Swedish context and the position of Swedish teachers in general. Second, I will explain how the discourses and positions are influenced by resource management and task distribution. Finally, I will discuss the implications of the results in relation to the general goals described for RPPs, which are educational improvement and equity, as well as provide some suggestions for further research.

Preschool teacher discourse and position as produced by the educational context

As described in the results section, there are indications in the data that participants tried to re-negotiate the supposed outcome-oriented discourse influencing the RPP to bring it more in line with a process-oriented discourse. Similarly, I could see in the results that preschool teachers seemed to argue the opposite, in favour of an outcome-oriented discourse. This contrast between the different perspectives of researchers and preschool leaders, on the one hand, and preschool teachers, on the other, might not be that surprising, given the balance between autonomy, framing and accountability under which Swedish teachers operate. Hence, one explanation is that preschool teachers’ movement towards an outcome-oriented discourse is related to the didactic tradition in which this programme operates (Hudson, Citation2007), as well as the specific context that Sweden constitutes, as compared to other countries that also operate in the didactic tradition (Ryve & Hemmi, Citation2019). Importantly, the didactic tradition places teachers in a position of more autonomy, in contrast with the curriculum tradition. Arguably, when more freedom and autonomy are combined with weak framing, insecurity can grow. As such, preschool teachers would arguably want more guidance. This is argued to be the case in the Swedish context, where weak frames for teachers in form of vague state curriculum, along with frequent and demanding accountability testing (Ryve & Hemmi, Citation2019), have created an environment in which Swedish preschool and primary school teachers feel insecure (Wermke, Citation2011). “Insecure” teachers in Sweden tend to seek more support and guidance from outside sources compared to, for instance, their more confident German counterparts. This is in line with indications in the data that preschool teachers expect more guidance from researchers in the collaborative programme under study. German teachers, who have a clearer state curriculum (even though in a didactic tradition) focused on content rather than competences (Wermke, Citation2011), could be argued to have just the right amount of freedom and framing to be confident enough to collaborate productively. It should be noted, however, that German teachers, who have more confidence in their professional capacity, rely more on peer guidance and are sceptical of outside assistance. As such, German teachers seem to be less open to collaboration in the first place.

Discourse and positions as influenced by resource management and task distribution

Looking more closely at the different positions that are characteristic of the two discourses as they are negotiated, I can make a few more observations. For instance, the positions in the outcome-oriented discourse are more in line with the traditional roles of researchers and practitioners, where researchers are the “scientific experts” and, as such, do what they do best, with limited influence from practitioners, and where teachers are seen as implementers or interpreters, utilizing their expertise and experience of local practice (Sjölund et al., Citation2022a). The process-oriented discourse, in contrast, is characterized by positions with an emphasis on active collaboration, most apparent in the relationship between researchers and preschool leaders as critical/practice partners. In relation to this, an important part of organizing an RPP is to consider to what degree tasks are distributed between participants compared to what degree tasks are based on active collaboration between researchers and practitioners (Sjölund et al., Citation2022a). Aspects to consider include participants’ learning, progress towards RPP goals, and the resources consumed.

Arguably, if one conceives of collaboration as a means to reach a common goal (outcome-oriented discourse), the RPP utilizes collaborative processes that are as effective as possible in achieving that common goal. In this case, it makes sense for researchers to do what they do best, that is, engage in scientific inquiry, and for practitioners to do what they do best, that is, adapt to local practice. From this perspective, it is also reasonable to reduce the amount of active collaboration around tasks, if possible, as this would involve more people in more aspects of the RPP, thus utilizing more resources (e.g., time and money). This could be argued not to be the most efficient way of collaborating if one wishes to achieve common goals; instead, those arguing in favour of an outcome-oriented discourse would arguably rather divide work based on expertise than actively collaborate on tasks. In contrast, if one mainly views collaboration as a process of mutual learning and growth (process-oriented discourse), it makes sense to organize in a way that promotes as much interaction between researchers and practitioners as possible. In other words, if the aim is to learn from each other to grow as individuals and organizations, one should arguably strive for active collaboration on as many aspects of the RPP as possible.

Conclusions and future directions

To frame the conclusion of the present paper, I want to reiterate that the results show a connection between an outcome-oriented discourse, more traditional participant positions, and division of labour. Similarly, there is a connection between a process-oriented discourse, less traditional participant positions, and active collaboration on tasks between participants. Interestingly, active collaboration between researchers and practitioners on, for instance, data analysis has been identified as important if RPPs are to manage to integrate research into practice (Brown & Allen, Citation2021). This is crucial, and because integration of research into practice is a critical intermediary outcome of RPPs’ attempts to reach their long-term goals of educational improvement and equity (Desimone et al., Citation2016), it should also be of interest to those who are more outcome-oriented to consider an RPP structure with more active collaboration. But as discussed earlier, there are additional aspects involved here. For instance, more active collaboration on tasks also requires more resources, which might not always be available. As such, it would be valuable for further research to study how resources are distributed and used in different kinds of RPPs and how that influences the quality and efficiency of the collaboration between researchers and practitioners. Moreover, most (if not all) individuals, organizations and RPPs draw on both these discourses, and as can be seen in the present results, the discourses and positions are intensely negotiated, creating ambiguous identities for the participants. Hence, while a negotiation of discourses is necessary if one wishes to avoid the hegemony of a certain discourse, it can also mean that participants end up confused about the ambiguous identities. To continue investigating the ambiguity identified in the present study, researchers might want to explore how participants in RPPs experience and address the ambiguous positions that arise through discursive negotiations and how this ambiguity influences their motivation, engagement, and learning. It is also worth considering the replicability of these results outside of Sweden. Specifically, it would be valuable for scholars from other countries to investigate the prevalence of these discourses and positions in RPPS from their context. Lastly, while the negotiation of discourses and positioning and its power dynamics is surfaced to some degree in this study, the power-dynamics that is elucidated when preschool teachers resist the positioning of researchers and preschool leaders is underexplored, and outside the scope of this paper. Hence, I urge those invested in RPPs to continue the investigation of the power dynamics in RPPs and to do so in different contexts.

To conclude, when we are aware of the discourses that influence the way we perceive the relationship between researchers and educational leaders, we can also initiate a reflective process regarding them. Moreover, we can begin an emancipating process and avoid potentially limiting perspectives. As such, the present study provides key insights into the underexplored discourses and related positions that are foundational to participants’ perspectives in the context of RPPs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In the present study, we will adopt a distinction between positioning and identity, as identity is more continuous and stable and positioning is momentary (Davies & Harré, Citation1990). This distinction and its relevance to the study will be further described in the theory and method sections.

2 In the data, as described in the limitations section, first-hand information from preschool teachers is scarce, instead what is presented here is school leaders conveying what “their” preschool teachers have said.

References

- Akkerman, S., & Bruining, T. (2016). Multilevel boundary crossing in a professional development school partnership. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 25(2), 240–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2016.1147448

- Berg, B. (2022). Reformers påverkan på lärares undervisning i grundskolan och förskolan: En läroplansteoretisk studie om undervisningsuppdraget och lärarrollen i förändring. Mälardalen University (Sweden).

- Breault, R. (2014). Power and perspective: The discourse of professional development school literature. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 42(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2013.869547

- Brown, S., & Allen, A. (2021). The interpersonal side of research-practice partnerships. Phi Delta Kappan, 102(7), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/00317217211007333

- Chan, C., & Clarke, M. (2014, January 1). The politics of collaboration: Discourse, identities, and power in a School-University Partnership in Hong Kong. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 42(3), 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2014.902425

- Coburn, C., Bae, S., & Turner, E. (2008). Authority, status, and the dynamics of insider–outsider partnerships at the district level. Peabody Journal of Education, 83(3), 364–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/01619560802222350

- Coburn, C., & Penuel, W. (2016). Research-practice partnerships in education: Outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educational Researcher, 45(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X16631750

- Coburn, C., Penuel, W., & Geil, K. (2013). Research-practice partnerships: A strategy for leveraging research for educational improvement in School Districts (0277-4232). (Research to Practice Goes Both Ways, Issue. W. T. G. Foundation.

- Davies, B., & Harré, R. (1990). Positioning: The discursive production of selves. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 20(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1990.tb00174.x

- Desimone, L., Wolford, T., & Hill, K. (2016). Research-practice: A practical conceptual framework. AERA Open, 2(4), 233285841667959. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858416679599

- Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. Psychology Press.

- Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. Routledge.

- Farrell, C., Davidson, K., Repko-Erwin, M., Penuel, W., Quantz, M., Riedy, R., & Brink, Z. (2018). A descriptive study of the IES researcher–Practitioner partnerships in education research program (technical report, 3). NCRPP.

- Farrell, C., Harrison, C., & Coburn, C. (2019). What the hell is this, and who the hell are you?” Role and identity negotiation in research-practice partnerships. AERA Open, 5(2), 13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419849595

- Farrell, C., Penuel, W., Allen, A., Anderson, E., Bohannon, A., Coburn, C., & Brown, S. (2022). Learning at the boundaries of research and practice: A framework for understanding research–practice partnerships. Educational Researcher. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X211069073

- Farrell, C., Penuel, W., Coburn, C., Daniel, J., & Steup, L. (2021). Research-practice partnerships in education: The state of the field. William T. Grant Foundation.

- Hammersley, M. (2001). Some questions about evidence-based practice in education. In I. Thomas, & R. Pring (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in education (pp. 133–149). Open University Press.

- Hargreaves, A., & Shirley, D. (2010). Den fjärde vägen: En inspirerande framtid för utbildningsförändring (1 ed.). Studentlitteratur AB.

- Honig, M., Venkateswaran, N., McNeil, P., & Twitchell, J. (2014). Leaders’ use of research for fundamental change in school district central offices: Processes and challenges. In K. Finnigan, & A. Daly (Eds.), Using research evidence in education - From the schoolhouse door to Capitol Hill (pp. 33–52). Springer.

- Hudson, B. (2007). Comparing different traditions of teaching and learning: What can we learn about teaching and learning? European Educational Research Journal, 6(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2007.6.2.135

- Levinsson, M. (2013). Evidens och existens. Evidensbaserad undervisning i ljuset av lärares erfarenheter.

- Mull, C., & Adams, K. (2017). The identification, influence, and impact of boundary spanners within research-practice partnerships. In M. Reardon, & J. Leonard (Eds.), Exploring the community impact of research-practice partnerships in education (pp. 271–291). Information Age Publishing Inc.

- Nygård, O. (2020). Educational aspirations and attainments : How resources relate to outcomes for children of immigrants in disadvantaged Swedish schools [PhD dissertation]. Linköping University Electronic Press.

- OECD. (2003). New challenges for educational research. OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2004a). National review on educational R&D: Examiners’ report on Denmark.

- OECD. (2004b). National review on educational R&D: Examiners’ report on England.

- Penuel, W., Riedy, R., Barber, M., Peurach, D., LeBouef, W., & Clark, T. (2020). Principles of collaborative education research with stakeholders: Toward requirements for a New research and development infrastructure. Review of Educational Research, 90(5), 627–674. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320938126

- Potter, J. (1996). Representing reality: Discourse, rhetoric and social construction. Sage.

- Rivera, P., & Chun, M. (2023). Unpacking the power dynamics of funding research-practice partnerships. Educational Policy, 37(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/08959048221134585

- Ryve, A., & Hemmi, K. (2019, November 1). Educational policy to improve mathematics instruction at scale: Conceptualizing contextual factors. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 102(3), 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-019-09887-6

- Sjölund, S., Lindvall, J., Larsson, M., & Ryve, A. (2022a). Mapping roles in research-practice partnerships – A systematic literature review. Educational Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.2023103

- Sjölund, S., Lindvall, J., Larsson, M., & Ryve, A. (2022b). Using research to inform practice through research-practice partnerships – A systematic literature review. Review of Education, 10(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3337

- Skolverket. (2018). Beskrivande data 2017. Förskola, skola och vuxenutbildning (Rapport 468). https://www.skolverket.se/getFile?file = 3953

- SOU. (1992:94). Skola för bildning. Department of Education.

- Tseng, V., Easton, J., & Supplee, L. (2017). Research-Practice partnerships: Building Two-Way streets of engagement. Social Policy Report, 30(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2379-3988.2017.tb00089.x

- Tseng, V., Fleischman, S., & Quintero, E. (2018). Democratizing evidence in education. In B. Bevan, & W. Penuel (Eds.), Connecting research and practice for educational improvement: Ethical and equitable approaches (pp. 3–16). Routledge.

- Weber, R. (1990). Basic content analysis. Sage.

- Wentworth, L., Khanna, R., Nayfack, M., & Schwartz, D. (2021). Closing the research-practice Gap in education. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 19(2), 57–58. https://doi.org/10.48558/EH5B-Y819

- Wermke, W. (2011). Continuing professional development in context: Teachers’ continuing professional development culture in Germany and Sweden. Professional Development in Education, 37(5), 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2010.533573

- Wermke, W., & Höstfält, G. (2014). Contextualizing teacher autonomy in time and space: A model for comparing various forms of governing the teaching profession. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(1), 58–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2013.812681

- Yamashiro, K., Wentworth, L., & Kim, M. (2023). Politics at the boundary: Exploring politics in education research-practice partnerships. Educational Policy, 37(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/08959048221134916