ABSTRACT

In response to global competition in higher education, university rankings have been developed. These have been interpreted as indicating the regions and countries with the most prestigious and competitive higher education institutions. The rankings are viewed as important in many countries, but their role is ambiguous and contested in the Nordic region. This study aimed to analyse how rankings were addressed in research literature in the Nordic countries between 2003 and 2022. Both peer-reviewed studies and ‘grey’ (unpublished) literature were analysed via a scoping review methodology, encompassing 86 studies in total. The review identified five research themes pertaining to university rankings, touching on universities’ structural and governance reforms, educational affairs, funding and finances, research policies, and internationalization. The study also investigated the changes over time in the themes addressed in rankings-related discourse in the Nordic countries. Most of the studies were conceptual in nature and were conducted via qualitative methods.

Introduction

Governments habitually seek to answer the question, ‘What can be done to improve our nation’s performance?’ (Marginson, Citation2009, p. 591). Higher education (HE) is seen as playing a vital role in building competitive advantage. Even a single higher education institution (HEI) in a ranking can help to enhance institutional visibility in the international arena, especially in emerging economies with institutions positioned lower in the rankings. A country, region, or city that is ranked highly in a global ranking can enhance its potential as a knowledge hub and increase its appeal (Hazelkorn, Citation2014).

University rankings are now a worldwide phenomenon, caused and influenced by the globalization of HE (OECD, Citation2009). There are a variety of ranking procedures, ostensibly intended to increase transparency, and these have had a considerable impact on HE systems, individual institutions, and professional career paths. At the same time, they have covertly introduced a competitive market into HE (Nixon, Citation2020). Rankings can assist high-achieving students, especially international graduate students, in shortlisting their university choices; they may also serve as an important factor in influencing investment decisions, partnerships, and the recruitment of employees. Rankings also help other HEIs in identifying potential partners, assessing membership of international networks and organizations, and benchmarking (Hazelkorn, Citation2014).

There are several major global rankings in HE, the best-known and most influential of which are the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU), Times Higher Education World University Rankings (THE), and Quacquarelli Symonds World University Rankings (QS). The rankings are primarily based on research-related indicators. For ARWU, research amounts to 100%, of the indicators applied; for THE the figure is 85%, and for QS 70% (alongside other internationalization and reputation indicators in the latter two cases) (Hazelkorn, Citation2014; Loukkola, Citation2016; Yeo, Citation2018). Over the years, the United Kingdom and the United States have been consistently ranked as the top producers of scientific publications in the world (Bégin-Caouette, Citation2020), and HEIs from these two countries typically occupy the top positions in university rankings.

Although global rankings are likely to trigger powerful incentives, there may be some downsides. All ranking systems are incomplete in their ability to describe the realities of HEIs (OECD, Citation2009). Rankings provide a quantitative and popular means of benchmarking universities on a national, regional, and global basis. Nevertheless, a number of social, ethical, and methodological concerns and anomalies exist regarding the league tables of HEIs (Shahjahan et al., Citation2022). These include, notably, the fact that different ranking systems are associated with different notions of what constitutes quality in higher education, as well as the possibility that rankings may redirect attention from the central purposes and missions of higher education (Marginson, Citation2007).

In Europe, as elsewhere, rankings now form an element in formal policies at institutional, national, and regional levels. Two policy lines have shaped the ranking debate in the European context. The Bologna process resulted in the creation of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), and the European Union's (EU) ambition to enhance Europe's competitiveness through knowledge and skills. This aim includes both educational initiatives and significant investments in research through the development of the European Research Area (ERA). U-Multirank, which is generally regarded as the European response to global rankings, has received special attention (Loukkola, Citation2016). In any case, in addition to being committed to European goals, the governments of EU member states implement European HE policies because they consider these policies to be effective tools in addressing the challenges resulting from globalization (Litjens, Citation2005).

The Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Iceland) have experienced the effects of Europeanization and of the Bologna Process (Schmidt, Citation2009), even if Iceland and Norway are not EU member states. Higher education in this region is characterized by an emphasis on egalitarian values, including open access to HE and equality of opportunity (Sørensen et al., Citation2019). It is of particular interest to examine issues related to the global excellence and competition agenda in the Nordic region, as these issues have undoubtedly entered public debate, and in the context of increasing globalization the Nordic countries have been seen as having ‘slow mover’ characteristics (Poutanen, Citation2022).

Nordic higher education places a high priority on excellence and quality. Although there are potential tensions between excellence and egalitarian values in the Nordic countries, the value domain has appeared to cushion some of the incompatibilities (Elken et al., Citation2016b). However, little research has been conducted on the role and relevance of university rankings in Nordic HE. In a comparative study conducted by Elken et al. (Citation2016a) the authors found that global university rankings in the Nordic region do appear to have had a modest impact on the identities of HEIs. According to Elken et al. (Citation2016b), all of the case institutions in their study performed reasonably well in the rankings but were some ways from occupying the highest positions (in either ARWU or THE). Thus, to take an example, although in global rankings Finland is ranked highly in terms of primary school education in the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and in technology development and innovation capability, no Finnish university has been ranked among the world's most prestigious universities (Aula & Siltaoja, Citation2021). It is therefore important to explore the role of university rankings in Nordic HE more precisely by mapping the relevant scientific literature onto the Nordic countries in question. With this aim in view, the present study sought to analyse studies touching on university rankings, conducted in the Nordic countries between 2003 and 2022. The more specific research questions were:

What are the key themes of current research on university rankings in the Nordic countries, and how have these themes varied over time?

What types of evidence are used in studies on university rankings in the Nordic countries?

This study's contribution is twofold. Firstly, it fills a significant gap in the existing body of literature on university rankings, which has largely overlooked the unique experiences and strategies of Nordic countries. Secondly, our study uncovers the dynamic evolution of discourse on rankings, revealing not just static themes but the changing trends and shifts over time. This longitudinal perspective is relatively rare in ranking studies but essential to fully understand the ongoing impact of rankings on higher education systems.

The practical implications of our research are manifold. For policymakers, our study offers a rich understanding of the ranking-led changes in governance, funding, education, research, and internationalization strategies that could inform future policy decisions. Practitioners, including university leaders and administrators, could draw from our insights to navigate the complexities of global performance indicators and make strategic decisions. For researchers, our study not only presents an exhaustive review of the literature but also highlights the evolving discourse and areas of further investigation. Additionally, by examining the Nordic experience, we provide a valuable regional perspective, informing discussions about the implications of global ranking systems on different higher education systems. Finally, our study helps to illuminate the potential future trajectory of higher education in the Nordic region, given its historical responses to global rankings. It allows stakeholders to anticipate future trends and developments, ultimately contributing to the shaping of a more resilient and adaptable higher education system in the face of global challenges.

Materials and methods

To address the research questions, we conducted a scoping review. Scoping reviews generally encompass a broad spectrum of topics and may use a variety of study designs. They are less likely to address specific research questions or to evaluate the quality of studies in the manner of a systematic review (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005). There can be various reasons to undertake a scoping study. In our case, we wished to investigate the range of studies published on university rankings in the Nordic countries, in order to identify the scope and nature of the research activity in the field. Furthermore, the scoping could potentially serve as a summary of research findings in the field. Using Arksey and O'Malley's (Citation2005, p. 22) approach, the scoping review was conducted via the following steps:

Study selection stage: We included only studies published between 2003 and July 2022. The starting date of 2003 was chosen because the first global ranking of universities was developed in 2003 by Shanghai (ARWU), and the annual Times Higher World University Rankings (THE) were launched in 2004, accompanied by a joint edition in collaboration with QS. If a study was published, for example, in 2015 but its data pertained to a period prior to 2003, it was excluded. The search language was English. Studies could be both published and unpublished (the latter being referred to as ‘grey’ literature). Studies were not excluded on the basis of geographical location as long as the study was about the Nordic countries (i.e., Finland, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and Iceland).

The articles used were from high-quality journals (Q1 and Q2) on the basis of their Scimago Journal and Country Rank. Peer-reviewed journal articles and books were examined. In evaluating the relevance of the books, each chapter was examined, but the study included only the chapter(s) that pertained to the scope of this review. The studies were from various disciplinary and methodological traditions.

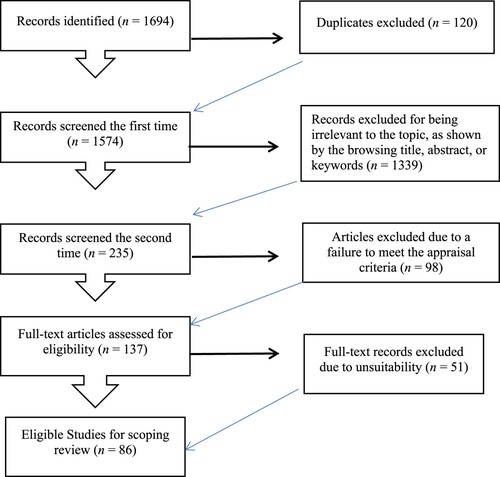

Identifying relevant studies: As already indicated, the idea of scoping the field is to be as comprehensive as possible in identifying suitable studies (published and unpublished) and reviews. To achieve this, we sought research evidence via different sources: Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, JSTOR, Taylor & Francis, SAGE, EBSCOhost, Springer, Google Scholar (in which saturation was reached after 50 pages of reviewing), and ResearchGate. Academia.com and Google.com were also used. Initially, key concepts such as ‘ranking’ AND ‘Nordic countries’ AND ‘higher education’ were searched for. Synonyms, abbreviations, and new keywords were added or redefined in the string by conducting more research, considering the early results. The search string was tested and refined using repeated scoping searches. The search strategy was ultimately finalized in such a way that it used every string separately or in combination. Strings were used for each of the above-mentioned databases. In a few cases, we contacted researchers or organizations via, for example, Research Gate or LinkedIn, in order to identify unpublished work or sources that we could not find in the databases. On the basis of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Liberati et al., Citation2009), a reliable and valid appraisal of the evidence base was created ().

We developed a charting approach similar to a narrative review (Pawson, Citation2002, p. 171), which includes information about the ‘process’ of the review so that the ‘outcome’ is understandable. Nonetheless, the ‘descriptive-analytical’ method within the narrative tradition (involving the application of a common analytical framework to all primary research reports and the collection of standard information on each study) remained valid. The data that we charted were entered onto a ‘data charting form’ using the Zotero database program. These data formed the basis of the analysis. Ultimately, 86 studies dealing with university rankings in the Nordic region were identified. Of these, 69 were peer-reviewed articles, 13 were book chapters, 3 were theses, and one was an international conference paper. In order to identify the themes and topics relating to university rankings in our data we employed qualitative content analysis in which similar notions were coded under content categories.

Findings

Time period, source locations, and target locations

The earliest item in our scoping review was from 2004, while 86 studies referring to university rankings in Nordic HE were published up to 2022. The numbers of studies within the 18-year timeline suggest that between 2004 and 2010, university rankings in the Nordic region received little attention. Between 2011 and 2016 the number of studies was considerably greater, culminating between 2017 and 2022 (). In terms of the source locations, the greatest single group of studies (n = 34) consisted of those conducted in Finland alone. In terms of target locations, a fairly large number of studies (n = 43) were on a combination of at least two Nordic countries, followed by studies on Finland alone (n = 27).

Table 1. Time periods, source location(s), and target location(s) of the studies.

Themes and topics

A wide range of topics and themes relating broadly to university rankings were represented in the studies in our data. Nonetheless, some themes were more dominant than others ().

Table 2. Themes by target location(s).

Most of the studies on university rankings in our review related to the structural and governance reforms of universities. The studies under this theme focused on reforms both at the system level (macro policies) and institutional level (meso policies). The greatest number of studies under this theme involved Finland’s higher education (n = 22) and the smallest number were on Danish higher education (n = 4). The common objects of the studies at the system level were the adoption of neo-liberal policies and strategic plans to utilize rankings (thereby pursuing the status of a world-class university), structural changes to promote excellence and global competitiveness, and efforts by national governments to shift the paradigm from cooperation to competition and to promote market-like efficiency and structures (Aula & Siltaoja, Citation2021; Lundin & Geschwind, Citation2023; Thun, Citation2020; Tervasmäki et al., Citation2020; Nikkola & Tervasmäki, Citation2022; Li, Citation2020; Hansen et al., Citation2019; Sørensen et al., Citation2019; Geschwind et al., Citation2019a; Pinheiro et al., Citation2014; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019; Dovemark et al., Citation2018, p. 408; Liu et al., Citation2018; Ursin, Citation2017; Tienari et al., Citation2016; Kauppinen & Kaidesoja, Citation2014; Jauhiainen et al., Citation2015; Välimaa et al., Citation2014; Wiborg, Citation2013; Hallonsten & Silander, Citation2012; Musiał, Citation2010; Schmidt, Citation2009; Jauhiainen et al., Citation2009; Keskinen & Silius, Citation2006; Häyrinen-Alestalo & Peltola, Citation2006).

At the institutional level, the structural/governance studies dealt with topics such as shifts in institutional governance policy towards the principle of quasi-market accountability, formalizing external stakeholders within the governance of HE, changes in leadership and management structures, and professional mechanisms allowing new forms of evaluation (Schnurbus & Edvardsson, Citation2022; Jokila, Citation2020; Tapanila et al., Citation2020; Jalava, Citation2013; Nokkala & Bladh, Citation2014).

The literature review indicates a direct correlation between Nordic universities’ system and institutional governance reforms and their attempts to elevate their positions in global rankings. These reforms vary from increased autonomy to implementing new evaluation and accountability procedures. Pinheiro and Berg (Citation2017) and Musiał (Citation2010) provide evidence of a transition from traditional forms of governance towards structures emphasizing market-like efficiency over time, reflecting changes in the discourse around rankings. Accordingly, in a pursuit to climb global rankings, Finland revamped its university governance, shifting from state-run entities to autonomous institutions, leveraging academic capitalism and strategic performance measures (Keskinen & Silius, Citation2006; Schmidt, Citation2009; Jalava, Citation2013; Kauppinen & Kaidesoja, Citation2014; Tienari et al., Citation2016; Sørensen et al., Citation2019; Tervasmäki et al., Citation2020; Aula & Siltaoja, Citation2021). Norway implemented similar changes, affording universities greater autonomy (Musiał, Citation2010; Lind et al., Citation2019; Geschwind et al. Citation2019b; Hansen et al., Citation2019; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019). Meanwhile, Denmark underscored the importance of quality assurance (Hansen et al., Citation2019; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019; Schmidt, Citation2009), while Sweden shifted towards more managerial governance models, prioritizing efficiency and performance (Hallonsten & Silander, Citation2012; Hansen et al., Citation2019; Lundin & Geschwind, Citation2023; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019; Schmidt, Citation2009).

Themes concerned with funding and finances and themes related to educational affairs (with a concern for university rankings) were the second most typical themes in our data (n = 26 for both themes). The focus on funding involved topics such as diversifying funding, including competition-based funding, and commercializing results from research and development as a means of promoting the excellence of the university. Furthermore, performance-based university structures and strategic changes in university funding were common topics under this theme (Griffin, Citation2022; Aula & Siltaoja, Citation2021; Jokila, Citation2020; Hansen et al., Citation2019; Geschwind et al., Citation2019a; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019; Jokila et al., Citation2019; Sørensen et al., Citation2019; Ursin, Citation2017; Kristensen & Karlsen, Citation2018; Elken et al., Citation2016b; Kauppinen & Kaidesoja, Citation2014; Nokkala & Bladh, Citation2014; Jalava, Citation2013; Hallonsten & Silander, Citation2012; Musiał, Citation2010; Schmidt, Citation2009; Keskinen & Silius, Citation2006). The greatest number of studies on funding and finances related to Finland’s higher education system (n = 10), and to a combined Nordic perspective (n = 9).

Changes in funding structures and sources in Nordic countries, often motivated by an aspiration to enhance global ranking, are clearly evident in the literature reviewed. Schmidt (Citation2009) and Griffin (Citation2022) underscore how funding, based on performance indicators and heightened competition, has profoundly influenced university rankings. Over time, the transition towards more output-oriented, competitive funding mirrors the evolution in ranking discourse. Specifically, Finland has seen a shift towards performance-based funding, with an emphasis on diversifying funding sources (Hansen et al., Citation2019; Jokila et al., Citation2019; Jokila, Citation2020; Aula & Siltaoja, Citation2021). Norway has also experienced a transition towards performance-based funding, while Denmark has introduced more competitive funding mechanisms (Hansen et al., Citation2019; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019). In Sweden, there has been a push towards a larger proportion of private revenue and competitive research funding (Hallonsten & Silander, Citation2012; Hansen et al., Citation2019; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019).

Educational affairs related to university rankings broadly refers to having university educational procedures oriented towards developing students’ intercultural competencies, and to deepening the research component. Many of the studies focused on the recruitment of students from a wide variety of social, cultural, and educational backgrounds, and on expanding the university’s language policies (all these in conjunction with market-led education reforms). The majority of the topics dealing with educational affairs related to a Finnish (n = 7), Swedish (n = 6), or combined Nordic (n = 8) perspective (Tange & Jæger, Citation2021; Lundin & Geschwind, Citation2023; Niska, Citation2021; Jokila, Citation2020; Jokila et al., Citation2019; Roumbanis, Citation2019; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019; Hansen et al., Citation2019; Sørensen et al., Citation2019; Airey et al., Citation2017; Wiers-Jenssen, Citation2019; Hellekjær & Fairway, Citation2015; Hultgren, Citation2014; Wiborg, Citation2013; Schmidt, Citation2009; Barabasch, Citation2009; Saarinen, Citation2012).

The adoption of market-led education reforms, language policies, and diverse recruitment strategies in Nordic countries has direct implications for university rankings. These strategies, largely driven by global trends, have evolved over time in response to the changing criteria and metrics of rankings. For example, Barabasch (Citation2009) and Wiborg (Citation2013) highlight how the shift towards English-language instruction and the expansion of university language policies have directly increased the international appeal, and consequently, the global rankings of these universities. The literature offers a variety of evidence, including policy analyses and statistical data, to support these claims.

In all four countries, the drive to increase the quality of education and the number of graduates, in order to enhance their standing in international tables, is clearly influenced by the rankings. In Finland, for instance, there has been a policy emphasis on study credits and the number of degrees granted (Jokila et al., Citation2019; Jokila, Citation2020; Sørensen et al., Citation2019; Niska, Citation2021). Similarly, Norway has also focused on increasing the number of completed degrees (Hansen et al., Citation2019; Wiers-Jenssen, Citation2019). Denmark has prioritized improving the quality of education, implementing reforms aimed at enhancing the quality of teaching, and ensuring that students complete their studies within the standard study period (Hultgren, Citation2014; Hansen et al., Citation2019; Tange & Jæger, Citation2021). Sweden, conversely, has implemented the Bologna Process, which includes measures to improve the comparability of degrees across Europe, in order to boost its standing in the rankings (Lundin & Geschwind, Citation2023; Roumbanis, Citation2019; Schmidt, Citation2009).

Research policies, as related to university rankings, refers to a stronger focus on research in universities and to more publications in international scientific journals, seeking thus to showcase both the quality and volume of research results. The reviewed studies focused on many activities by which universities had taken steps to achieve this goal. These included, for example, organizing strategic priorities tightly within a research excellence framework, plus policies to expand doctoral graduation rates and the number of postdoctoral fellowships. The aims here included an increase in the capacity for producing new knowledge, the creation of international networks for academic research production, a more market-oriented approach towards research activities, and efforts to publish in indexed journals (Verbytska & Kholiavko, Citation2020; Bégin-Caouette et al., Citation2020; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019; Hansen et al., Citation2019; Morphew et al., Citation2018; Zapp et al., Citation2018; Kristensen & Karlsen, Citation2018; Bégin-Caouette, Citation2017; Schriber, Citation2016; Elken et al., Citation2016b; Kauppinen & Kaidesoja, Citation2014; Kivinen et al., Citation2013; Hallonsten & Silander, Citation2012; Kivinen & Hedman, Citation2008; Keskinen & Silius, Citation2006).

Research policies and activities in Nordic universities have been significantly influenced by the ambition to elevate their positions in global rankings. For example, Kristensen & Karlsen (Citation2018) and Pinheiro et al. (Citation2019) illustrate how an increased emphasis on research output, specifically in high-impact journals, and the establishment of centers of excellence have been direct responses to the criteria set by these rankings. Over time, the focus has shifted from the quantity to the quality of research, mirroring changes in the discourse around rankings. Finland (Kauppinen & Kaidesoja, Citation2014; Elken et al. Citation2016a; Verbytska & Kholiavko, Citation2020) and Norway (Hansen et al., Citation2019; Zapp et al., Citation2018) have implemented policies emphasizing the number of scientific publications and research impact. Denmark has also prioritized the quality and impact of research but has added a focus on research collaborations and networks (Hansen et al., Citation2019). Like its Nordic counterparts, Sweden has put in place strategies to boost its research output, with a concentrated effort on high-quality research and international collaborations (Hallonsten & Silander, Citation2012; Benner & Sörlin, Citation2007; Roumbanis, Citation2019; Hansen et al., Citation2019).

Internationalization policies constituted the final theme identified in the analysis. Relatively few studies (n = 13) were conducted on this theme. The theme refers to enhancing educational exports and establishing internationalization strategies in HEIs, the aim being to score well in the rankings (in which internationalization and reputation form key indicators). The topics in our review related to the shifting of rationales from a more traditional approach towards a new and more integrated entity; this would encompass the internationalization of research and education, student and staff mobility, international agreements, and international networks and partnerships (Himanen & Puuska, Citation2022; Tange & Jæger, Citation2021; Lundin & Geschwind, Citation2023; Jokila, Citation2020; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019; Jokila et al., Citation2019; Wiers-Jenssen, Citation2019; Kristensen & Karlsen, Citation2018; Christensen & Gornitzka, Citation2017; Elken et al., Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Kivinen et al., Citation2015; Kauppinen & Kaidesoja, Citation2014; Saarinen, Citation2012; Barabasch, Citation2009; Benner & Sörlin, Citation2007; Smeby & Trondal, Citation2005).

Rankings have played a pivotal role in shaping internationalization strategies and research policies across the Nordic region. Finland, for instance, adopted a commercial tuition fee policy for non-EU/EEC students, focused on increasing the number of international students and staff, and implemented policies focusing on the number of scientific publications and the impact of research. Norway also prioritized attracting international students and staff, adopted English as the language of instruction in many programs (Smeby & Trondal, Citation2005; Wiers-Jenssen, Citation2019) and implemented similar research policies to Finland (Kauppinen & Kaidesoja, Citation2014; Elken et al. Citation2016b; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019; Jokila et al., Citation2019; Jokila Citation2020). Denmark echoed these strategies with policies aimed at attracting international students and staff, fostering international research collaborations, and emphasizing the quality and impact of research (Tange & Jæger, Citation2021). Sweden likewise increased its emphasis on internationalization and research output, focusing on English-taught programs, recruiting a larger international student body, and encouraging high-quality research and international collaborations (Lundin & Geschwind, Citation2023; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019).

In sum, this analysis suggests that changes in Nordic universities’ educational, research, internationalization, funding, and governance strategies over time have been largely driven by the desire to improve positions in global rankings. The types of evidence used to support these observations in the literature have also varied over time and across themes, reflecting changes in ranking criteria and discourse. This deeper, more dynamic analysis of the themes identified in the scoping review offers a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between these strategies and university rankings.

Changes in the rankings-related discourse in the Nordic countries over time

As evidenced in our review, between 2004 and 2010, academic discourse on rankings in Nordic higher education exhibited a growing interest in the use of rankings as a tool to enhance international competitiveness. There was a strong emphasis on improving the global visibility and reputation of Nordic institutions, with the intention of attracting international students, researchers, and funding. Universities sought to benchmark themselves against prestigious institutions worldwide and improve their rankings. Strategies such as investing in research excellence, recruiting internationally renowned faculty, and increasing the publication output were commonly pursued to improve ranking scores. In addition, strategies such as implementing tuition fees for international students were considered likely to generate additional revenue and improve the financial sustainability of universities (Engwall, Citation2004; Häyrinen-Alestalo & Peltola, Citation2006; Keskinen & Silius, Citation2006; Benner & Sörlin, Citation2007; Aksnes et al., Citation2008; Schmidt, Citation2009; Jauhiainen et al., Citation2009; Barabasch, Citation2009; Wæraas & Solbakk, Citation2009).

Based on our review from 2011 to 2016, the discourse on rankings in the Nordic countries began to evolve. While rankings continued to be acknowledged as a measure of institutional performance, there was an increasing recognition of the limitations and potential drawbacks of relying solely on rankings for decision-making. There was a growing concern that rankings might oversimplify the complex nature of higher education institutions and fail to capture their diverse missions and contributions to society. Discussions revolved around the need for a more nuanced understanding of rankings and their impact on academic values, institutional strategies, and research priorities. In addition, attention was paid to the need to balance the pursuit of internationalization with the preservation of academic autonomy and promotion of high-quality research and education. Universities grappled with the question of how much weight to give to rankings in decision-making (Aula & Tienari, Citation2011; Xia et al., Citation2012; Saarinen, Citation2012; Hallonsten & Silander, Citation2012; Nikunen, Citation2012; Kivinen et al., Citation2013; Ylijoki & Ursin, Citation2013; Wiborg, Citation2013; Kivinen et al., Citation2013; Jalava, Citation2013; Hultgren, Citation2014; Nokkala & Bladh, Citation2014; Välimaa et al., Citation2014; Pinheiro et al., Citation2014; Engwall, Citation2014; Kauppinen & Kaidesoja, Citation2014; Marca Wolfensberger, Citation2015; Jauhiainen et al., Citation2015; Kivinen et al., Citation2015; Lundahl, Citation2016; Schriber, Citation2016; Luoma et al., Citation2016; Antikainen, Citation2016; Elken et al., Citation2016a; Elken et al., Citation2016b; Piro & Sivertsen, Citation2016; Tienari et al., Citation2016).

During the period from 2017 to 2022, the discourse on rankings in the Nordic countries witnessed further expansion, encompassing a critical examination of the methodologies and criteria employed in rankings. This led to a heightened awareness of the potential biases and limitations inherent in ranking systems, particularly their heavy reliance on bibliometric indicators and their capacity to perpetuate inequalities. Furthermore, along with the concern for internationalization and competitiveness, more attention was paid to rankings in relation to sustainability, equality, diversity, and the overall societal impact. Universities and policymakers increasingly emphasized the importance of adopting an approach that would take into account multiple dimensions of institutional quality, such as teaching and learning, societal impact, and engagement with external stakeholders. In response, efforts were made to develop alternative or complementary assessment frameworks that would extend beyond rankings and offer a more comprehensive understanding of higher education institutions. Recognizing their role in tackling global challenges, universities also sought to align their activities with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. The central themes that emerged during this period included interdisciplinary collaboration, engagement with external stakeholders, and a focus on generating meaningful societal impact. Furthermore, in response to the need to address issues of equality, diversity, and inclusion, efforts were made to promote more equitable opportunities for underrepresented groups in academia (Hellstén, Citation2017; Christensen & Gornitzka, Citation2017; Airey et al., Citation2017; Pinheiro & Berg, Citation2017; Bégin-Caouette et al., Citation2017; Ursin, Citation2017; Siekkinen et al., Citation2017; Göransson, Citation2017; Bégin-Caouette, Citation2017; Young et al., Citation2017; Wang, Citation2017; Yeo, Citation2018; Dovemark et al., Citation2018; Zapp et al., Citation2018; Kristensen & Karlsen, Citation2018; Angervall & Beach, Citation2018; Morphew et al., Citation2018; Liu et al., Citation2018; Isopahkala-Bouret et al., Citation2018; Sørensen et al., Citation2019; Hansen et al., Citation2019; Geschwind et al., Citation2019b; Söderlind et al., Citation2019; Pinheiro et al., Citation2019; Roumbanis, Citation2019; Wiers-Jenssen, Citation2019; Geschwind et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Kohvakka et al., Citation2019; Lind et al., Citation2019; Jokila et al., Citation2019; Bégin-Caouette et al., Citation2020; Jokila, Citation2020; Tervasmäki et al., Citation2020; Tapanila et al., Citation2020; Thun, Citation2020; Angervall & Beach, Citation2020; Li, Citation2020; Erkkilä et al., Citation2020; Lundin & Geschwind, Citation2023; Niska, Citation2021; Tange & Jæger, Citation2021; Aula & Siltaoja, Citation2021; Schnurbus & Edvardsson, Citation2022; Diogo & Carvalho, Citation2022; Griffin, Citation2022; Nikkola & Tervasmäki, Citation2022; Poutanen, Citation2022; Himanen & Puuska, Citation2022).

Methods and data sources used in the studies

The studies reviewed were in large measure qualitative in nature (50%). Quantitative and mixed methods studies composed respectively 13% and 7% of the studies in our scope. In addition, there were conceptual articles (18%) and book chapters (12%). Most of the qualitative studies focused on a variety of university documents (such as universities’ strategies and legislations, research and funding documents) and on various policy documents (e.g., key government strategies).

A somewhat lesser number of studies took the form of conceptual studies. In our scoping review, 26 conceptual papers (16 articles and 10 book chapters) were published. By contrast, 11 publications in total (out of 86) utilized a quantitative approach. These latter studies typically used bibliometric data, surveys, and statistics as materials.

A few mixed-method studies (9 publications) were conducted. These studies utilized a combination of transcripts and questionnaires (Bégin-Caouette et al., Citation2020), interviews and surveys (Lind et al., Citation2019), databases, questionnaires, and interviews (Geschwind et al., Citation2019a; Bégin-Caouette, Citation2017; Bégin-Caouette et al., Citation2017), as well as policy texts, surveys, and interviews (Hellstén, Citation2017).

Discussion and conclusions

Themes, locations, and trends

We analysed studies on university rankings published in the Nordic countries between 2003 and 2022. Applying a scoping review methodology, we found 86 relevant studies in English. We identified five themes in the studies, namely, universities’ structural and governance reforms, changing funding and finances, educational affairs, research policies, and internationalization. These themes were often intertwined in the texts.

A large proportion of the studies concentrated on policies, strategies, and activities relating to universities’ structural and governance reforms, in which the aim was to achieve the status of a world-class university in a competitive environment. Somewhat less prominent than the structural and governance reform theme were themes dealing with educational affairs, and with funding and finances. The themes of research policies and internationalization – despite being important criteria in ARWU, THE, and QS – received less attention in the studies included in our review.

In addressing our research questions, we also charted data on study source location(s), target location(s), and methods. As regards the target locations, we found that the majority of the studies (43 out of 86) related to a combination of Nordic countries; thereafter, they followed the order Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. In our data, there were no studies on Iceland. Finland provided the largest overall number of studies, and Finland was also the most frequent individual target country. This observation suggests a need for more research from individual Nordic countries other than Finland in order to gain a better overall picture of the role of university rankings in the Nordic region.

Our findings also indicate that qualitative studies seem to be increasingly popular in investigating university rankings. Most of the qualitative studies related to only one or two data sources, which might create a bias regarding the strategies and activities observed. Only a few mixed-method studies were present in our data. This could indicate a need for more diverse perspectives in university-ranking studies.

The findings indicate that Finland and Sweden are moving more towards global HE markets, and that many structural reforms have been carried out. By contrast, Denmark has taken a step in the opposite direction since August 2018, having recently adopted more nationally oriented anti-internationalization policies, involving a reduction in the number of English-medium courses (Tange & Jæger,, Citation2021). Such a policy may indicate a desire to pay less attention to global rankings in the future. It would therefore be useful to have studies on the adoption of such policies and their effects on Denmark's international position. It was also notable that among the Scandinavian countries, Norway appears to be the country most reluctant to pursue a market-oriented policy. Norway thus emerges as an eager defender of the traditional welfare state, and of a comprehensive education organization (Wiborg, Citation2013).

Our analysis of the changes in the themes addressed within ranking-related discourse from 2004 to 2022 indicated a shift from a narrow focus on international competitiveness towards a more nuanced and critical perspective. While rankings continued to be considered, there was greater emphasis on the limitations and potential unintended consequences of relying solely on rankings for decision-making. The discussions evolved towards a broader understanding of institutional quality, encompassing diverse dimensions of higher education excellence, including the societal role of universities.

Limitations, and implications for the future

This review can be seen as a springboard for innovative approaches to researching university rankings in the Nordic context. However, the study has limitations, insofar as some studies relevant to this article may have been overlooked, despite our systematic review of several databases. In addition, some of the contextual richness, diversity, and variation between the studies can be obscured by the syntheses applied in this scoping review. Future reviews could address this limitation by focusing more on variety and less on the pure abundance of data.

It should be noted that our review included only studies published in English. This might in part explain why studies on Finland were so dominant. Finnish differs greatly from the other Scandinavian languages; it is therefore the norm in Finland to publish in English if one is addressing Scandinavian audiences. By contrast, the other Scandinavian countries can understand each other’s languages. Future studies should include published studies in all the indigenous Nordic languages, in order to expand the notion of regional geographical clusters, with the possibility also of identifying some unreviewed topics.

The reviewed studies suggested that the Nordic region has taken many measures in attempts to meet the global ranking criteria. Nonetheless, some gaps can be identified. The studies did not investigate, for example, how effective the policy changes have been in Nordic HE systems; nor did the studies pay attention to the longer-term implications, or to whether the changes implemented have in fact been reflected in higher university rankings.

Achieving the status of a world-class university may well require significant institutional transformation. This can involve the restructuring of governance systems, with new policies and strategic initiatives. Researchers may have focused more on these areas because they are seen as crucial for improving institutional performance and competitiveness in the rankings. The emphasis on structural and governance reforms may also have been influenced by the policies set by governments or higher education authorities in the Nordic countries. A strong policy emphasis on institutional reform or on the pursuit of world-class status may have shaped the research agenda, leading to more studies in this area.

It is interesting that research policies and internationalization have been important criteria in global rankings such as ARWU, THE, and QS, but received less attention in the studies analysed. This could indicate a discrepancy between the emphases in the rankings and scholars’ research priorities in the Nordic countries. It is possible that regional researchers have had different foci or have regarded other factors as more influential in shaping institutional performance or higher education development. The actual reasons for the observed pattern would require further investigation, including interviews with researchers or an analysis of funding patterns.

Looking to the future, it can be expected that Nordic universities will continue to navigate amid the tensions between academic values and market-driven demands. The balance between maintaining academic autonomy and meeting external expectations, which involve rankings, will remain challenging. Internationalization will continue to be a priority, with a focus on attracting talented students and researchers worldwide. Furthermore, the issues of equality, diversity, and inclusion are likely to receive increased attention, with efforts to create more equitable opportunities for underrepresented groups in academia. A particular emphasis is likely to be on universities’ contribution to a sustainable and just global future. Hence, sustainability and societal impact will be increasingly pre-eminent.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Airey, J., Lauridsen, K. M., Räsänen, A., Salö, L., & Schwach, V. (2017). The expansion of English-medium instruction in the Nordic countries: Can top-down university language policies encourage bottom-up disciplinary literacy goals? Higher Education, 73(4), 561–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9950-2

- Aksnes, D. W., Frølich, N., & Slipersæter, S. (2008). Science policy and the driving forces behind the internationalisation of science: The case of Norway. Science and Public Policy, 35(6), 445–457.

- Angervall, P., & Beach, D. (2018). The exploitation of academic work: Women in teaching at Swedish universities. Higher Education Policy, 31(1), 1–17.

- Angervall, P., & Beach, D. (2020). Dividing academic work: Gender and academic career at Swedish universities. Gender and Education, 32(3), 347–362.

- Antikainen, A. (2016). The Nordic model of higher education. In Routledge handbook of the sociology of higher education (pp. 234–240). Routledge.

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Aula, H., & Siltaoja, M. (2021). Praised from birth: Social approval assets in the creation of a new university. Baltic Journal of Management, 16(4), 638–657. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-04-2020-0103

- Aula, H. M., & Tienari, J. (2011). Becoming “world-class”? Reputation-building in a university merger. Critical Perspectives on International business, 7(1), 7–29.

- Barabasch, A. (2009). Reforming higher education in Nordic countries. Studies of change in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden.

- Bégin-Caouette, O. (2017). Small Mighty Centers in the Global Academic Capitalist Race: A Study of Systemic Factors Contributing to Scientific Capital Accumulation in Nordic Higher Education Systems (Doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto (Canada).

- Bégin-Caouette, O. (2020). The perceived impact of eight systemic factors on scientific capital accumulation. Minerva, 58(2), 163–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-019-09390-5

- Bégin-Caouette, O., Jansson, J., & Beaupré-Lavallée, A. (2020). The perceived contribution of early-career researchers to research production in Nordic higher education systems. Higher Education Policy, 33(4), 777–798. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-018-0125-5

- Bégin-Caouette, O., Schmidt, E. K., & Field, C. C. (2017). The perceived impact of four funding streams on academic research production in Nordic countries: The perspectives of system 46. Science and Public Policy, 44(6), 789–801. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scx014

- Benner, M., & Sörlin, S. (2007). Shaping strategic research: Power, resources, and interests in Swedish research policy. Minerva, 45(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-006-9019-6

- Christensen, T., & Gornitzka, Å. (2017). Reputation management in complex environments—a comparative study of university organizations. Higher Education Policy, 30(1), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-016-0010-z

- Diogo, S. M., & Carvalho, T. (2022). Brothers in arms? How neoliberalism connects North and South higher education: Finland and Portugal in perspective. Social Sciences, 11(5), 213.

- Dovemark, M., Kosunen, S., Kauko, J., Magnúsdóttir, B., Hansen, P., & Rasmussen, P. (2018). Deregulation, privatisation and marketisation of Nordic comprehensive education: Social changes reflected in schooling. Education Inquiry, 9(1), 122–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2018.1429768

- Elken, M., Hovdhaugen, E., & Stensaker, B. (2016a). Global rankings in the Nordic region: Challenging the identity of research-intensive universities? Higher Education, 72(6), 781–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9975-6

- Elken, M., Stensaker, B., & Hovdhaugen, E. (2016b). Do global university rankings drive convergence? Evidence from the Nordic region. In E. Hazelkorn (Ed.), Global rankings and the geopolitics of higher education (pp. 268–281). Routledge.

- Engwall, L. (2004). The Americanization of Nordic management education. Journal of Management Inquiry, 13(2), 109–117.

- Engwall, L. (2014). The recruitment of university top leaders: Politics, communities and markets in interaction. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(3), 332–343.

- Erkkilä, T., Piironen, O. (2020). What counts as world class? Global university rankings and shifts in institutional strategies. In Rider, et al. (Ed.), World class universities (pp. 171–196). Springer.

- Geschwind, L., Hansen, H. F., Pinheiro, R., Pulkkinen, K., & (2019a). Governing performance in the Nordic universities: Where are we heading and what have we learned?. In R. Pinheiro, L. Geschwind, H. F. Hansen, & K. Pulkkinen (Eds.), Reforms, organizational change and performance in higher education (pp. 269–299). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Geschwind, L., Kekäle, J., Pinheiro, R., & Sørensen, M. P. (2019b). Responsible universities in context. In M. P. Sørensen, L. Geschwind, J. Kekäle, & R. Pinheiro (Eds.), The responsible university (pp. 3–29). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Göransson, B. (2017). Role of universities for inclusive development and social innovation: Experiences from Sweden. In Universities, inclusive development and social innovation (pp. 349–367). Springer.

- Griffin, G. (2022). The ‘Work-Work Balance’ in higher education: Between over-work, falling short and the pleasures of multiplicity. Studies in Higher Education, 47(11), 2190–2203.

- Hallonsten, O., & Silander, C. (2012). Commissioning the university of excellence: Swedish research policy and new public research funding programmes. Quality in Higher Education, 18(3), 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2012.730715

- Hansen, H. F., Geschwind, L., Kivistö, J., Pekkola, E., Pinheiro, R., & Pulkkinen, K. (2019). Balancing accountability and trust: University reforms in the Nordic countries. Higher Education, 78(3), 557–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-0358-2

- Häyrinen-Alestalo, M., & Peltola, U. (2006). The problem of a market-oriented university. Higher Education, 52(2), 251–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-2749-1

- Hazelkorn, E. (2014). Rankings and the global reputation race. Critical Perspectives on Global Competition in Higher Education: New Directions for Higher Education, 2014(168), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20110

- Hellekjær, G. O., & Fairway, T. (2015). The mismatch between the unmet need for and supply of occupational English skills: An investigation of higher educated government staff in Norway. Higher Education, 70(6), 1033–1050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9882-x

- Hellstén, M. (2017). Internationalising Nordic higher education: Comparing the imagined with actual worlds of international scholar-practitioners. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE), 1(2), 2–13.

- Himanen, L., & Puuska, H. M. (2022). Does monitoring performance act as an incentive for improving research performance? National and organizational level analysis of Finnish universities. Research Evaluation, 31(2), 236–248. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvac004

- Hultgren, A. K. (2014). English language use at the internationalised universities of Northern Europe: Is there a correlation between Englishisation and world rank? Multilingua – Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication, 33(3-4), 389–411.

- Isopahkala-Bouret, U., Börjesson, M., Beach, D., Haltia, N., Jónasson, J. T., Jauhiainen, A., Jauhiainen, A., Kosunen, S., Nori, H., & Vabø, A. (2018). Access and stratification in Nordic higher education. A review of cross-cutting research themes and issues. Education Inquiry, 9(1), 142–154.

- Jalava, M. (2013). The Finnish model of higher education access: Does egalitarianism square with excellence? In Fairness in access to higher education in a global perspective (pp. 77–94). Brill.

- Jauhiainen, A., Jauhiainen, A., & Laiho, A. (2009). The dilemmas of the ‘efficiency university’ policy and the everyday life of university teachers. Teaching in Higher Education, 14(4), 417–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510903050186

- Jauhiainen, A., Jauhiainen, A., Laiho, A., & Lehto, R. (2015). Fabrications, time-consuming bureaucracy and moral dilemmas—Finnish university employees’ experiences on the governance of university work. Higher Education Policy, 28(3), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2014.18

- Jokila, S. (2020). From inauguration to commercialisation: Incremental yet contested transitions redefining the national interests of international degree programmes in Finland. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2020.1745016

- Jokila, S., Kallo, J., & Mikkilä-Erdmann, M. (2019). From crisis to opportunities: Justifying and persuading national policy for international student recruitment. European Journal of Higher Education, 9(4), 393–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2019.1623703

- Kauppinen, I., & Kaidesoja, T. (2014). A shift towards academic capitalism in Finland. Higher Education Policy, 27(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2013.11

- Keskinen, S., & Silius, H. (2006). New trends in research funding—threat or opportunity for interdisciplinary gender research? Nordic Journal of Women's Studies, 14(2), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740601022767

- Kivinen, O., & Hedman, J. (2008). World-wide university rankings: A Scandinavian approach. Scientometrics, 74(3), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-007-1820-y

- Kivinen, O., Hedman, J., & Kaipainen, P. (2013). Productivity analysis of research in natural sciences, technology and clinical medicine: An input–output model applied in comparison of Top 300 ranked universities of 4 North European and 4 East Asian countries. Scientometrics, 94(2), 683–699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0808-4

- Kivinen, O., Hedman, J., & Kaipainen, P. (2015). Reputation of universities in global rankings and top university research in six fields of research. In N. Callaos, J. Horne, B. Sánchez, A. Tremante, & F. Welsch (Eds.), Proceedings 9th International Multi-Conference on Society, Cybernetics & Informatics (IMSCI) (pp. 157–161). International Institute of Informatics and Systemics.

- Kohvakka, M., Nevala, A., & Nori, H. (2019). The changing meanings of ‘responsible university’. From a Nordic-Keynesian welfare state to a Schumpeterian competition state. In The responsible university (pp. 33–60). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kristensen, K. H., & Karlsen, J. E. (2018). Strategies for internationalisation at technical universities in the Nordic countries. Tertiary Education and Management, 24(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2017.1323949

- Li, H. (2020). How to retain global talent? Economic and social integration of Chinese students in Finland. Sustainability, 12(10), 4161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104161

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ, 339(jul21 1), b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

- Lind, J. K., Hernes, H., Pulkkinen, K., & Söderlind, J. (2019). External research funding and authority relations. In R. Pinheiro, L. Geschwind, H. F. Hansen, & K. Pulkkinen (Eds.), Reforms, organizational change and performance in higher education (pp. 145–180). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Litjens, J. (2005). The Europeanisation of higher education in the Netherlands. European Educational Research Journal, 4(3), 208–218.

- Liu, Q., Patton, D., & Kenney, M. (2018). Do university mergers create academic synergy? Evidence from China and the Nordic countries. Research Policy, 47(1), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.10.001

- Loukkola, T. (2016). Europe: Impact and influence of rankings in higher education. In E. Hazelkorn (Ed.), Global rankings and the geopolitics of higher education (pp. 127–139). Routledge.

- Lundahl, L. (2016). Equality, inclusion and marketization of Nordic education: Introductory notes. Research in Comparative and International Education, 11(1), 3–12.

- Lundin, H., & Geschwind, L. (2023). Exploring tuition fees as a policy instrument of internationalisation in a welfare state–the case of Sweden. European Journal of Higher Education, 13(1), 102–120.

- Luoma, M., Risikko, T., & Erkkilä, P. (2016). Strategic choices of Finnish universities in the light of general strategy frameworks. European Journal of Higher Education, 6(4), 343–355.

- Marca Wolfensberger, D. V. (2015). Talent development in European higher education: Honors programs in the Benelux, Nordic and German-speaking Countries (p. 335). Springer Nature.

- Marginson, S. (2007). Global university rankings: Implications in general and for Australia. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 29(2), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800701351660

- Marginson, S. (2009). University rankings, government and social order: Managing the field of higher education according to the logic of the performative present-as-future. In M. Simons, M. Olssen, & M. A. Peters (Eds.), Re-reading education policies (pp. 584–604). Brill.

- Morphew, C. C., Fumasoli, T., & Stensaker, B. (2018). Changing missions? How the strategic plans of research-intensive universities in Northern Europe and North America balance competing identities. Studies in Higher Education, 43(6), 1074–1088. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1214697

- Musiał, K. (2010). Redefining external stakeholders in Nordic higher education. Tertiary Education and Management, 16(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583881003629822

- Nikkola, T., & Tervasmäki, T. (2022). Experiences of arbitrary management among Finnish academics in an era of academic capitalism. Journal of Education Policy, 37(4), 548–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1854350

- Nikunen, M. (2012). Changing university work, freedom, flexibility and family. Studies in Higher Education, 37(6), 713–729.

- Niska, M. (2021). Challenging interest alignment: Frame analytic perspective on entrepreneurship education in higher education context. European Educational Research Journal, 20(2), 228–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904120909571

- Nixon, J. (2020). Disorderly identities: University rankings and the re-ordering of the academic mind. In S. Rider, M. A. Peters, T. Besley, & M. Hyvönen (Eds.), World class universities (pp. 11–24). Springer.

- Nokkala, T., & Bladh, A. (2014). Institutional autonomy and academic freedom in the Nordic context—similarities and differences. Higher Education Policy, 27(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2013.8

- OECD. Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI). (2009). Higher education to 2030: Volume 2: Globalisation. OECD.

- Pawson, R. (2002). Evidence-based policy: In search of a method. Evaluation, 8(2), 157–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1358902002008002512

- Pinheiro, R., Aarrevaara, T., Berg, L. N., Fumasoli, T., Geschwind, L., Hansen, H. F., Hernes, H., Kivistö, J., Lind, J.K., Lyytinen, A. and Pekkola, E. (2019). Nordic higher education in flux: System evolution and reform trajectories. In R. Pinheiro, L. Geschwind, H. Hansen, & K. Pulkkinen (Eds.), Reforms, organizational change and performance in higher education (pp. 69–108). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pinheiro, R., & Berg, L. N. (2017). Categorizing and assessing multi-campus universities in contemporary higher education. Tertiary Education and Management, 23(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2016.1205124

- Pinheiro, R., Geschwind, L., & Aarrevaara, T. (2014). Nested tensions and interwoven dilemmas in higher education: The view from the Nordic countries. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 7(2), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu002

- Piro, F. N., & Sivertsen, G. (2016). How can differences in international university rankings be explained? Scientometrics, 109(3), 2263–2278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2056-5

- Poutanen, M. (2022). I am done with that now. ‘Sense of alienations in Finnish academia. Journal of Education Policy, 38(4), 1–19.

- Roumbanis, L. (2019). Symbolic violence in academic life: A study on how junior scholars are educated in the art of getting funded. Minerva, 57(2), 197–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-018-9364-2

- Saarinen, T. (2012). Internationalization of Finnish higher education—is language an issue? International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2012(216), 157–173. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2012-0044

- Schmidt, E. K. (2009). Nordic higher education systems in a comparative perspective – recent reforms and impacts. The Journal of Finance and Management in Colleges and Universities, 6(4), 271–298.

- Schnurbus, V., & Edvardsson, I. R. (2022). The Third Mission among Nordic universities: A systematic literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 66(2), 238–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1816577

- Schriber, S. (2016). Nordic strategy research—topics, theories, and trends. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 32(4), 220–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2016.10.001

- Shahjahan, R. A., Bylsma, P. E., & Singai, C. (2022). Global university rankings as ‘sticky’ objects and ‘refrains’: Affect and mediatisation in India. Comparative Education, 58(2), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2021.1935880

- Siekkinen, T., Kuoppala, K., Pekkola, E., & Välimaa, J. (2017). Reciprocal commitment in academic careers? Finnish implications and international trends. European Journal of Higher Education, 7(2), 120–135.

- Smeby, J. C., & Trondal, J. (2005). Globalisation or europeanisation? International contact among university staff. Higher Education, 49, 449–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-2826-5

- Söderlind, J., Berg, L. N., Lind, J. K., & Pulkkinen, K. (2019). National performance-based research funding systems: Constructing local perceptions of research?. In Reforms, organizational change and performance in higher education (pp. 111–144). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sørensen, M. P., Geschwind, L., Kekäle, J., & Pinheiro, R. (2019). The responsible university: Exploring the nordic context and beyond (p. 318). Springer Nature.

- Tange, H., & Jæger, K. (2021). From Bologna to welfare nationalism: International higher education in Denmark, 2000–2020. Language and Intercultural Communication, 21(2), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2020.1865392

- Tapanila, K., Siivonen, P., & Filander, K. (2020). Academics’ social positioning towards the restructured management system in Finnish universities. Studies in Higher Education, 45(1), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1539957

- Tervasmäki, T., Okkolin, M. A., & Kauppinen, I. (2020). Changing the heart and soul? Inequalities in Finland’s current pursuit of a narrow education policy. Policy Futures in Education, 18(5), 648–661. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210318811031

- Thun, C. (2020). Excellent and gender equal? Academic motherhood and ‘gender blindness’ in Norwegian academia. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(2), 166–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12368

- Tienari, J., Aula, H. M., & Aarrevaara, T. (2016). Built to be excellent? The Aalto university merger in Finland. European Journal of Higher Education, 6(1), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2015.1099454

- Ursin, J. (2017). Transforming Finnish higher education: Institutional mergers and conflicting academic identities. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 35(2), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.35.2.295831

- Välimaa, J., Aittola, H., & Ursin, J. (2014). University mergers in Finland: Mediating global competition. New Directions for Higher Education, 2014(168), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20112

- Verbytska, A., & Kholiavko, N. (2020). Competitiveness of higher education system: International dimension. Economics & Education, 5(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.30525/2500-946X/2020-1-1

- Wang, H. Y. (2017). Once upon a reform: marketization of higher education and the identity transition of a Finnish university after the reform (Master's thesis, Itä-Suomen yliopisto).

- Wiborg, S. (2013). Neo-liberalism and universal state education: The cases of Denmark, Norway and Sweden 1980–2011. Comparative Education, 49(4), 407–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2012.700436

- Wiers-Jenssen, J. (2019). Paradoxical attraction? Why an increasing number of international students choose Norway. Journal of Studies in International Education, 23(2), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318786449

- Wæraas, A., & Solbakk, M. N. (2009). Defining the essence of a university: Lessons from higher education branding. Higher Education, 57(4), 449–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9155-z

- Xia, B. S., Liitiäinen, E., & Rekola, M. (2012). Comparative study of university and polytechnic graduates in Finland: Implications of higher education on earnings. Research in Comparative and International Education, 7(3), 342–351.

- Yeo, J. H. (2018). The effects of charging non-EU/EEA students’ tuition fees in Finland higher education: Comparing Nordic higher education.

- Ylijoki, O. H., & Ursin, J. (2013). The construction of academic identity in the changes of Finnish higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(8), 1135–1149.

- Young, M., Sørensen, M. P., Bloch, C., & Degn, L. (2017). Systemic rejection: Political pressures seen from the science system. Higher Education, 74(3), 491–505.

- Zapp, M., Helgetun, J. B., & Powell, J. J. (2018). (Re) shaping educational research through ‘programmification’: Institutional expansion, change, and translation in Norway. European Journal of Education, 53(2), 202–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12267