ABSTRACT

In Nordic countries, as well as in the Netherlands, schools have high school autonomy (OECD, Citation2016 [Netherlands 2016 Foundations for the Future. https://www.oecd.org/netherlands/netherlands-2016-9789264257658-en.htm]; Tolo et al., Citation2020 [Intelligent accountability in schools: A study of how school leaders work with the implementation of assessment for learning. Journal of Educational Change, 21(1), 59–82]). In schools there are both horizontal and vertical working relations and all teachers and school principals within a school are expected to take responsibility for collaborative-innovation practices (CIP). In this paper, we describe a study investigating how both horizontal and vertical working relations relate to CIP. We used longitudinal questionnaire (2036 teachers, 157 schools) and interview data (53 teachers, 20 schools). These data were gathered in Dutch schools participating in the large-scale ‘LeerKRACHT’ program. The results show that teachers perceive horizontal and vertical factors to enhance CIP. Furthermore, especially school principals and coach-teachers seem to be able to strengthen horizontal and vertical factors which leads to more CIP. We discuss implications for research and schools in the Netherlands and beyond.

Schools operate in demanding and rapidly changing environments. As a result, teachers and school principals are expected to continuously improve their school practices to maintain the quality of the education they provide (Lopes & Oliveira, Citation2020; Serdyukov, Citation2017). In literature on school development, change, and reform, there is an increasing emphasis on investigating how various educational interventions turn out (Boyd, Citation2021; Den Brok, Citation2018; Fullan, Citation2008; Vanlommel, Citation2021; Verbiest, Citation2021; Wubbels & Van Tartwijk, Citation2018). Some of these studies highlighted that interventions are sometimes an isolated activity of one teacher or a small group of teachers (Paju et al., Citation2022; Sales et al., Citation2017; Vangrieken & Kyndt, Citation2020). According to Vangrieken et al. (Citation2015), in education, a strong-rooted culture of individualism, autonomy, and independence appears to be dominant. A ‘culture of collaboration’, however, has many advantages. This is also shown in research traditions of whole-school improvement. It can result in more ‘school democracy’ and more appropriate ideas and solutions for the challenges faced by schools (Fullan, Citation2016; Sahlin, Citation2023; Sahlberg, Citation2010; Snoek et al., Citation2019; Tolo et al., Citation2020). A growing number of schools have begun to initiate types of teacher collaboration, such as ‘professional learning communities’ and ‘data teams’ (Admiraal et al., Citation2021; Hargreaves & O’Connor, Citation2017). Such collaborations of teachers in schools can be called horizontal working relations (e.g., Noordegraaf et al., Citation2016; Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2017; Torfing, Citation2019). Researchers from Nordic countries for instance studied the horizontal forms of accountability and responsibility in schools (Sahlberg, Citation2010; Tolo et al., Citation2020).

Consequently, international scholars have called for more ‘networked’ and ‘collaborative’ approaches (e.g., Liou et al., Citation2020). In the organizational literature, the notion of collaborative innovation is used for such approaches, which is characterized by both horizontal and vertical working relations (Bekkers & Noordegraaf, Citation2016; Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2017; Torfing, Citation2019). This notion fits within the broader field of school development research that approaches development as a collaborative process as well. Here both teachers’ working relations (horizontal) and working relations between teachers and school principals are studied (vertical). Studying both fits with the culture of The Netherlands and Nordic countries, which are found to be in the same cultural clusters, appreciating team-oriented and participative leadership (House et al., Citation2004; Liu, Citation2020), including horizontal and vertical working relations.

However, in daily school practice it seems that breaking with the individualistic culture and changing to more collaborative-innovation practices is hard. We have an unique opportunity to study the relationship between horizontal and vertical working relations and the degree of collaborative-innovation practices (CIP). Since, in the Netherlands there is a large-scale program called LeerKRACHT that aims to stimulate CIP in schools (LeerKRACHT means “Learning force” and also “Teacher” in Dutch). The program expects from both teachers and school principals to collaborate and share resources, knowledge, and ideas and it thus asks for at least one manner of working together. The program is used by over a thousand schools in the Netherlands, and the data used in the current paper are gathered as part of a larger research project in which this program was evaluated. We study the degree of CIP in primary, secondary, and vocational schools with a mixed method approach both at the start and when working on collaborative-innovation practices in a structured way with the program ‘leerKRACHT’.

Theoretical and analytical framework

Collaborative-innovation practices in schools

The notion of collaborative innovation was developed in research studying innovation in public sector contexts (Bekkers & Noordegraaf, Citation2016; Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2018). It is characterized by a multi-actor approach to innovation, with both vertical and horizontal working relations, wherein resources, knowledge, and ideas are exchanged, resulting in mutual development (Owen et al., Citation2008; Torfing, Citation2019). Vertical relations involve working relations that transverse different organizational levels, functions, and hierarchies (Torfing, Citation2019), which in schools would refer to teachers and school principals. Horizontal relations imply working relations between persons and organizations at the same hierarchical level, which would be teachers within a school or teachers affiliated with various schools. In this study, we apply this concept of collaborative innovation from the organizational literature in schools. We specifically focus on innovative practices of collaboration and therefore refer to collaborative-innovation practices.

Collaborative-innovation practices imply shared responsibility while collaborating. Fullan (Citation2016) and Sinnema et al. (Citation2020) argue that shared responsibility and collaborating in ways that leverage expertise across schools is essential to improve teaching and learning, resulting in school change. School organizations then benefit from the capacities and resources, knowledge, and ideas of multiple members, called a social exchange of resources (Coleman, Citation1988; Siisiainen, Citation2003 Sinnema et al., Citation2020). Researchers argue that CIP can have a powerful impact and facilitate more democratic, mutual, and appropriate solutions for school challenges (Azorín et al., Citation2020; Sinnema et al., Citation2020; Snoek et al., Citation2019). How CIP can lead to big innovations in schools is not the scope of this paper. We explore what teachers perceive to be relevant for collaborative-innovation practices to take place in schools.

Horizontal relations in collaborative innovation

In this study, we conceptualize horizontal relations as relations between teachers. Previous research examining horizontal relations indicates that the prior existence of a certain degree or intensity of collaboration helps to further enhance the degree of future collaboration (Hargreaves & O’Connor, Citation2017; Vangrieken et al., Citation2015). Vangrieken et al. (Citation2015) state that “without an essential amount of openness to collaborate, every effort pushing teachers towards collaboration may become lost in a culture of contrived collegiality” (p. 36). This also concerns a mindset of collaboration and involves teachers’ work style and routine. Organizational researchers recognize the complexity of how working together benefits from the prior existence of collaboration by emphasizing that cultural dynamics, i.e., how people are used to working and working together (‘This is how we work around here’) influences working relations (Noordegraaf et al., Citation2016; Thumlert et al., Citation2018).

In addition, a safe organizational climate, including trusting relationships and respect, supports risk taking and the exploration of innovative ideas (Tolo et al., Citation2020; Zhang & Zheng, Citation2020). Avalos-Bevan and Flores (2021) interviewed teachers and observed that horizontal relations require a climate marked by safe relationships and being open to each other. A study on informal learning indicated that teachers needed to feel safe to share their problems and collaborate (Grosemans et al., Citation2015), and research on team learning revealed that psychological safety is the most important and consistent predictor of learning occurring within teams (Boon et al., Citation2013; Dochy et al., Citation2014).

Vertical relations in collaborative innovation

In this study, we conceptualize vertical working relations as relations between teachers and school principals. Interestingly, the leerKRACHT program, used by all schools in this study, advices the school principal with the ultimate responsibility of the school to be part of working with the program. Therefore, we present previous research on formal leadership of school principals and focus on their leadership in our study. We acknowledge that within schools there are more (middle) leadership levels but these are beyond the scope of this study.

With formal leadership, we mean individuals who have the formal role in school (such as school principals) to exert influence over others to structure activities, relationships, knowledge, and skills (Daniëls et al., Citation2019; Yukl, 2002). Previous research on teacher collaboration acknowledges that school principals can support and guide teacher collaboration (Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2017; Torfing, Citation2019) by, for instance, inspiring and supporting staff and the facilitation thereof (Admiraal et al., Citation2016; de Neve & Devos, Citation2016; van Schaik et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). Avalos-Bevan and Flores (Citation2022) observed specific positive leadership practices that teachers experience that facilitate collaboration, namely emotional and informational support, encouragement of and respect for professional development, and setting direction. Also Tolo et al. (Citation2020) found a promising approach of how Norwegian school principals can challenge and motivate teachers to experiment and innovate and how school principals and teachers can share the responsibility in horizontal forms of accountability. However, in the specific context of collaborative innovation, previous studies on school principals’ role are largely theoretical or describe leadership practices only from the perspective of a school principal. Torfing (Citation2016) theoretically identified three types of leaders who can stimulate collaborative innovation in the public sector: conveners (e.g., spur interaction), facilitators (e.g., promoting collaboration), and catalysts (e.g., prompting actors to think out of the box). Furthermore, de Jong et al. (Citation2019) empirically studied leadership practices of school principals and found variation between school principals, ranging from principals who were distant to those who were quite involved in CIP.

Current study

The aforementioned studies identified three factors vital for teacher collaboration. We aimed to study how these three factors relate to collaborative-innovation practices, as two of these factors pertained to horizontal working relations: intensity of collaboration and safety, and one to vertical relations: leadership practices of school principals. We chose to use the word relate to not imply that we can say something about the direction of the relationship. Furthermore, we explore what teachers perceived relevant for collaborative-innovation practices and how horizontal and vertical working relation factors were associated.

To realize this aim, we could use a unique sample of schools that all participated in the same program aimed at stimulating CIP in schools (see Method section). The research question that guided our study was: How do horizontal and vertical working relations in schools relate to the degree of collaborative-innovation practices?

Method

Research design

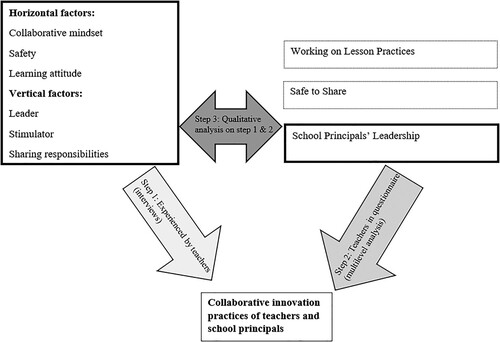

To study both the horizontal and vertical relations in schools and how they relate to CIP, we combined the strengths of qualitative (interviews) and quantitative data (two questionnaires). In our mixed method approach, several steps can be distinguished. In the first step, we analyzed the interviews with teachers with the aim of identifying which horizontal and vertical factors teachers experience that relate to the degree of CIP. In the second step, we analyzed teachers’ questionnaire data on how the prior intensity of teacher collaboration (horizontal), safety (horizontal), and school principals’ leadership (vertical) related to the degree of CIP. For these analyses, we used a multilevel analysis. In the third step, we analyzed the link between the horizontal and vertical factors in their relation to the degree of CIP. To do this, we combined the results from the interviews and questionnaires. Because of this, the design of our data collection was a convergent parallel design and the analyses an embedded design (Burke Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004). We subsequently explain these steps in detail but first we present information on the study context.

Context of the study: program aimed at collaborative-innovation practices

In 2016, the OECD highlighted that the educational quality of Dutch schools could be further improved by strengthening collaboration within schools. An independent Dutch foundation developed a program to achieve this aim in schools. So far, more than a thousand Dutch primary and secondary schools and schools for vocational education have voluntarily implemented this program. This is not a central or national policy initiative, schools choose to work with the program themselves. The program is based on a team-based approach, including teachers and school principal(s) to improve processes step-by-step, referring to the ‘agile’ principles of working in teams with short cycles (see Rigby et al., Citation2016). The program’s method consists of four tools: (1) stand-up sessions of 15 min, where ideas are translated into goals and action plans; (2) Within-school lesson visits; (3) Codesigning lessons; and (4) Students’ voices, a structured possibility to obtain students’ views as a source of inspiration.

In terms of the time allocation, firstly, a start team is trained by a coach from the external program, this coach remains involved for two years. The start team includes two to three coach-teachers (teachers who get a coach role in this program) and their school principal. The program advices to include the school principal with the ultimate responsibility of the school. Then, smaller groups of teachers are formed (8-10 persons) and within each team a coach-teacher helps the other teachers to collaboratively work on education with the four tools in a weekly routine. The school principal is expected to be quite actively involved in the teams and the practicing of the tools but not too steering.

Participants and sampling procedure

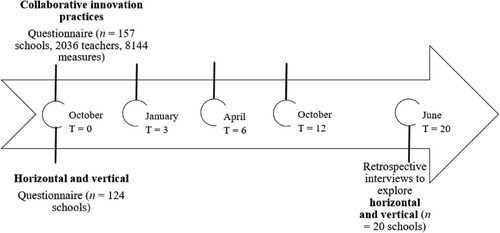

As part of the program, teachers completed questionnaires at several moments in time (see ). For the current study, we used data from a questionnaire on degree of CIP and a questionnaire on horizontal and vertical working relations.Footnote1 All schools that started to work with the program in 2017 and 2018 were in our dataset. The schools from which teachers answered these questionnaires were representative of Dutch schools in their urbanity, denomination, and school size (de Jong et al., Citation2021) and were from the primary, secondary, and vocational educational sectors.

Figure 1. Overview of data collection over time. Note. T is time in months. The lines indicate how many times the questionnaires were sent out (questionnaire on CIP 4 times to the same schools, questionnaire on horizontal and vertical and interviews once).

Furthermore, we conducted group interviews, including two to three teachers and at least one coach-teacher, with a total of 53 teachers across 20 schools. These schools were randomly selected based on a total list of schools that started to work with the program in September 2017 and 2018. The school principals received a short explanation about the investment required and the benefits of participating in the study. This resulted in 10 schools of the group of 2017 (face-to-face interviews were held in 2019) and 10 schools of 2018 (online interviews in 2020, due to Covid).

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee for social and behavioral sciences of our university (20-056). The teachers signed informed consent forms.

Measures

Collaborative-innovation practices

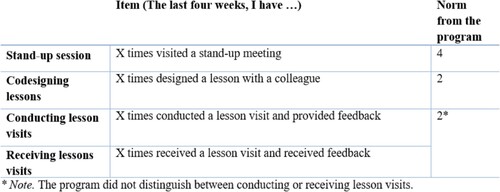

We measured the degree of CIP with four questionnaire items. These items examined the degree to which teachers use the tools of the leerKRACHT program (see ). The items formed a coherent scale at all four measurement points (α ranged from 0.73 to 0.81 at the four measurement points).

Horizontal and vertical relations

Retrospective group interviews

The first researcher openly asked a group of teachers per school (see sample under heading Participants and …): “What influences collaborative-innovation practices in your school?”. The researcher inquired on teachers’ answers and teachers could talk about positive and negative influences. The interviews were retrospective, and Covid-related answers were excluded. Interviews were audiotaped, transcripts were written, and member checks were conducted. The latter only led to minor changes.

Questionnaire: prior intensity of teacher collaboration, safety, and leadership

The program leerKRACHT designed a broad questionnaire on aspects of culture, completed by teachers. We chose what data to include in the study, based on insights in relevant factors for CIP from the theoretical and analytical framework and the available data of this questionnaire. A confirmatory factor analysis resulted in three scales on teacher collaboration, safety, and leadership. These together include 24 items, presented in Appendix 1. The scales had sufficient to good internal consistencies and we named them the following: Working on Lesson Practices (measuring the intensity of teacher collaboration on lesson practices, α = 0.73, 7 items), Safe to Share (measuring whether teachers felt safe to share their problems with colleagues; α = 0.85, 7 items), and School principals’ leadership (measuring how teacher perceive the involvement of school principals (the person with the ultimate responsibility of the school) with teachers and how much school principals stimulate teachers to improve education; α = 0.92, 10 items).

Analysis

The analyses consisted of three steps. These are explained below.

Step 1: what relates to CIP

Three researchers independently coded two interviews with teachers exploring what related to their CIP, as well as coded factors, using an open coding approach (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). Then, the first author coded all interviews and discussed all coded factors with the third author. A factor was included when it was named in more than one school (factors are presented in the results, ). Lastly, all authors jointly interpreted whether the factors pertained to horizontal or vertical relations.

Table 1. Factors mentioned by teachers in interviews that affect CIP.

Step 2: how horizontal and vertical working relations relate to CIP

To further study how horizontal and vertical working relations relate to collaborative innovation, we conducted a multilevel analysis using the Safe to Share, Working on Lesson Practices, and School Principals’ Leadership predictors. The ICC (see M0 in ) illustrated that a multilevel analysis fits our data, since we found that 12% of the variance in the degree of CIP was attributable to factors at the school level, 67% at the teacher level, and 21% at the measurement level. We measured the predictors both at the start of CIP in schools (time coded 0) and over time. Additionally, the assumptions, sufficient sample size, linear relationships, absence of multicollinearity, and normality for the dependent variable (Hox et al., Citation2018) were met. We checked this by following the procedure of Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2013). The missing values on the degree of CIP over time were assumed to be missing at random since 70 teachers with all four measurements did not score significantly different from teachers with three or less measurements.Footnote2 Missing values were not imputed, since multilevel analyses can effectively manage missing values under the missing-at-random assumption, and for outcome measures this is not necessary (Hox et al., Citation2018). Scatterplots indicated a quadratic development of CIP. Consequently, we computed a squared time variable (Time2) next to the Time variable (in months, see ). Lastly, 33 schools were missing from the questionnaire that measured the three predictors.

Table 2. Multilevel model predicting CIP with horizontal and vertical working relations.

The multilevel analysis was conducted with full maximum likelihood in HLM 8 (Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling). We added the predictors at the same time because, based on the literature, we did not expect one of the predictors to be more important than the others. We grand mean centered the predictors to allow the intercept to obtain a comprehensible value (being the mean of the degree of CIP when all independent variables are at their mean).

Step 3: how horizontal and vertical working relations are associated

To explore how the horizontal and vertical relations are associated in how they relate to CIP, we combined the horizontal and vertical factors mentioned by teachers from step 1 and the significant results of the multilevel analysis of step 2. We included schools in separate lines within one table. Three schools were dismissed from this analysis since their questionnaire data was missing. Out of the 17 schools, we selected extreme case studies, as this increases the reliability of the analyses (Seawright, Citation2016). As stated by Seawright (Citation2016), selecting extreme cases in the context of the main independent or dependent variable results in a better performance than other case-selecting approaches. Thus, to select extreme cases, we ordered the schools to come to a relative order. The ordering was based on their score on the degree of CIP and the scale(s) that resulted from the multilevel analysis (step 2). Since these multilevel results (step 2) are presented in the results, the next steps of the ordering are presented in step 3 of the results.

Results

Horizontal and vertical relations relate to CIP

The first analysis step resulted in an overview of both horizontal and vertical factors that teachers reported in interviews as relating to CIP in their schools. They mentioned three factors on the horizontal level: Collaborative mindset, Safety, and Learning attitude. On the vertical level, they also mentioned three factors: Leader (as leadership from school principals), Stimulator (as leadership of coach-teachers), and Sharing responsibilities (as leadership of teachers).Footnote3 In sum, teachers thus experienced both horizontal and vertical working relation factors to be able to contribute to more and/or better CIP.

How horizontal and vertical relations relate to CIP

The second analysis step included a multilevel analysis. The first model (see , M1) indicated that the degree of CIP develops in a slightly quadratic manner (y = 2.09–0.05x + 0.004×2.).

We tested whether the Working on Lesson Practices, Safe to Share, and School Principals’ Leadership scales predicted CIP. School Principals’ Leadership significantly predicted the degree of CIP when Safe to Share was also included (see the fixed model, M2).Footnote4 Safe to Share worked as a suppressor in the sense that it led to an increase in the predictive validity of School Principals’ Leadership (for suppressors, see Ludlow et al., Citation2014). This means that when the variance in School Principals’ Leadership that is shared with Safe to Share was blocked by including Safe to Share in the regression equation, the remaining variance in School Principals’ Leadership predicted the degree of CIP. Variance in the Working on Lesson Practices and Safe to Share scales did not predict the degree of CIP either alone or together.

Lastly, we identified that schools differ in their development of the degree of CIP over time (see random model M3b). Therefore, we tested whether the differences between schools can be predicted with Working on Lesson Practices, Safe to Share, and School Principals’ Leadership. The results showed that these three scales cannot predict the random variances between schools.Footnote5 Given the higher AIC (10794.62) and to improve the readability of the table, this model was not included in .

Association between horizontal and vertical working relations

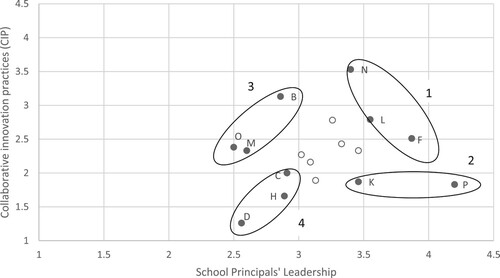

With the third step, we aimed to better understand the association between horizontal and vertical working relations. We combined the horizontal and vertical factors from step 1 and the positive predictor School Principals’ LeadershipFootnote6 on the degree of CIP of step 2. We subsequently plotted the schools on School Principals’ Leadership and the degree of CIP (see ) and selected extreme case studies, resulting in four groups:

high on both scales

high on School Principals’ Leadership, low on CIP

low on School Principals’ Leadership, high on CIP

low on both scales

Figure 3. Case selection on school principals’ leadership and CIP (n = 11, out of 17 schools). Note. The four circles represent the four groups of selected extreme case studies.

We qualitatively analyzed how the teachers within the four groups experienced each horizontal and vertical factor to extract their positive (+), medium (+/-), and negative experiences (-) (see ). Regarding leadership of school principals, we discovered that teachers who indicated high scores on the questionnaire scale on leadership (School Principals’ Leadership) were also positive in the interviews about their school principal (Leader factor) and vice versa. Teachers, in the interviews, were positive about how school principals provided frameworks and professional space. In the questionnaire, the School principals’ leadership scale indicated to what extent school principals stimulated teachers to improve their education collaboratively.

Table 3. Experiences per factor for four groups on school principals’ (SP) leadership and CIP.

We compared groups 1 and 2 (high on School Principals’ Leadership) with groups 3 and 4 (low on School Principals’ Leadership). illustrates that groups 1 and 2 all obtained positively scored factors (with one ambiguous score), while groups 3 and 4 indicated negative, medium, and ambiguous scores. We thus observed how teachers experienced their School Principals’ Leadership related to teachers’ own experiences of the horizontal and vertical factors.

We did not find a relationship between the degree of CIP and how teachers experience the horizontal and vertical factors. We compared groups 1 and 3 (high on CIP) and groups 2 and 4 (low on CIP) and observe that both groups 1 and 3 and groups 2 and 4 had a variety of experiences (+, +/-, -). With the factors, however, we could not explain why group 2, namely schools with high scores on School Principals’ Leadership and all positive factors, scored relatively low on CIP.

In step 2, we found that Safety was a suppressor of how School Principals’ Leadership predicted degree of CIP. Similarly, step 3 also showed an association between safety and leadership of school principals, since groups 1 and 2 (high on School Principals’ Leadership) had positive scores on Safety and groups 3 and 4 (low on School Principals’ Leadership) had medium and negative scores on Safety.

Lastly, Stimulator was the only factor that was experienced positively by all groups. When teachers mentioned the Stimulator role, they always referred to the coach-teacher who stimulated CIP, by guiding, preparing, and organizing stand-up sessions, and stimulating teachers to collaborate. Since Stimulator was experienced positively by groups that had both high and low scores on School Principals’ Leadership, it seemed that the role of a Stimulator is needed in addition to the role of school principals in CIP. In the interviews, teachers mentioned that a Stimulator had an even more important role when school principals are partially or not involved with the CIP. For instance, a teacher from School B, with lower scores on School Principals’ Leadership (and high CIP) described the relation between the role of a Stimulator and the school principal: “As a coach, I discuss the session beforehand and steer it in the right direction. But I said to the school principal that I don't want to be solely responsible, that he should also participate.”

In most of the schools with high scores on School Principals’ Leadership, it was mentioned that their Stimulator became part of the teacher team and that the organizing tasks were shared with the teachers. A teacher from School P (high leadership, low CIP) said:

The coaches say that they know a bit more about the program but do not have all the answers and thus we will search for them together. What they knew they shared with us in a concrete way, it wasn't like, ‘We are the coaches, you are the teachers, so you have to do what we say.’ They really took us in.

We provide an overview of the results in . The first and second step studied which factors relate to CIP, in two different manners (see on the left and right of the figure). The third step studied how these factors (from step 1) relate to School Principals’ Leadership (the significant predictor of step 2) and degree of CIP in schools.

Figure 4. Overview of results of the three steps. Note. The results of the interviews are presented on the left of the figure (step 1), the results of the questionnaire are presented on the right (step 2). In the middle and at the bottom, we present the qualitative analysis of step 1 and 2 (step 3).

Discussion

Following the notion of collaborative innovation, the current study addressed the role of horizontal and vertical working relations and how these related to schools’ degree of CIP. Overall, we conclude that, in teachers’ experiences, both horizontal and vertical working relation factors can contribute to CIP. In other words, we observe that collaborative-innovation practices involve both horizontal and vertical levels, forming a complex social system which can be adaptive. In order to work on collaborative-innovation practices, it seems relevant for teachers, school principals, and researchers to be aware of influence processes within and between these working relations.

More specifically, we found that school principals can enhance the degree of CIP. Our study provides insights into which leadership practices should be included in the role of school principals to have such a positive influence. Teachers mentioned they prefer school principals who are connected, affiliated, have a stimulating attitude, and are not too controlling, but set clear frameworks and provide professional space and safety for enhancing CIP. Our study mainly provides insights into how school principals contribute to the degree of CIP. However, the interviews prompt insights in how school principals can contribute to the quality of CIP in schools as well, such as being the critical friend during stand-up meetings and motivating teachers to experiment with their lesson practices.

Through these leadership practices that were mentioned before on how school principals can positively influence the degree of CIP, school principals seem to steer the agency of teachers. Steering the agency of teachers is also described by Mentink (Citation2014), who theoretically discussed the role of school principals’ leadership in professional learning communities (PLC). He stated that school principals need to strongly outline the lower limit or minimum teacher functioning in PLCs, as well as being more stimulating and facilitating and more from a distance when it comes to teacher development. This is in line with the concept of ‘distributed control,’ as mentioned by Zimmerman et al. (Citation1998). Furthermore, de Jong et al. (Citation2022) found that school principals seek a balance in their role of providing frameworks, direction, and space. They identified a variation in the leadership of school principals from a school principal perspective, ranging from school principals who were distant to those who were more involved in the CIP. The current study contributes the perspective of teachers, since teachers also observed variation between school principals, ranging from quite distant school principals to school principals who were stimulating to teachers, trusted teachers as professionals, and were involved in CIP. Tolo et al. (Citation2020) also found, in a Norwegian study, that school principals need to challenge teachers to experiment and that trust and distrust influences how closely school principals position themselves to teachers. The result that our findings confirm the findings of Tolo et al. (Citation2020) indicates that we can suggest some takeaways beyond the Netherlands, for instance for Nordic countries.

Another finding relating to school principals’ role was that the horizontal and vertical working relation factors mentioned by teachers are associated with school principals’ leadership practices. School principals are found to be central ‘shapers’ of school culture, including a safe climate (Daniëls et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, research on collaborative innovation approaches argues that safety and mutual trust are necessary for persons to be convinced that it is worthy and safe to be involved in working relations (Sahlin, Citation2023; Torfing, Citation2019). These previous findings from the literature can be linked to our study, since we found a positive association between school principals’ leadership practices and the safety of working relations. Our study seems to indicate that school principals can create the right ‘climate’ – a positive and safe spirit that sets working relations for the degree of CIP in motion. So, school principals have an important role in providing a safe climate for work processes at the intersection of horizontal and vertical relations as well. At the same time, school principals cannot do this alone, since cultural aspects such as safety, are held by the whole school personnel. Furthermore, situational leadership theory (Hujala, Citation2004; Thompson & Glasø, Citation2018) discusses how the leadership practices of school principals are influenced by other factors. In the example of safety, we assume that certain degrees of safety in working relations call for different leadership practices. Several cultural theories also address that sociocultural contexts relate to leadership practices (Rogoff, Citation1990) and contexts are transformed through leadership practices (Spillane & Sherer, Citation2004).

We also want to highlight the finding that teachers’ working on lesson practices does not relate to the degree of CIP in schools. Not finding this relationship in the quantitative analysis might be due to how we measured both variables. The questionnaire scale of working on lesson practices measured informal collaboration activities, while degree of CIP is measured by a more formal and fixed form, namely, the tools of the leerKRACHT program. Does this mean that teachers interpret the program differently than their informal collaborative practices in school? Our interpretation is that teachers might interpret the leerKRACHT program as different from informal and/or collaborative practices. In informal conversations with teachers, teachers sometimes mentioned that they do for instance just walk into classrooms of their colleagues and stay shortly. They do not feel this is a lesson visit since, in their opinion, that should be for instance a longer visit.

Findings resulting in directions for future research

Another main finding was the role of coach-teachers as stimulators, in addition to the school principal, in CIP. This finding provides many directions for future research. While teachers mentioned that coach-teachers sometimes replace school principals who are less involved in CIP, we found that coach-teachers have an additional role next to the direct and positive influence of school principals. Based on the interviews, we see that the coach-teachers play a role in horizontal relations by structuring and preparing collaboration sessions, and by stimulating teachers to collaborate. They play a role in vertical relations by addressing school principals on their role in the degree of CIP and connecting teachers and school principals, acting as a kind of mediator. This coach-teacher role is a component of the program that schools implement, with the aim of stimulating the degree of CIP. Our study clearly indicates that they have a vital role, but we cannot claim that a coach-teacher as a stimulator is indispensable. Therefore, further exploring whether a coach-teacher is always necessary for a higher degree of CIP and, if so, what this role should entail is a possible avenue for future research. Moreover, we think that it would enhance the literature to further explore the impact of the (well-defined) role of coach-teachers on how school principals decide to enact their leadership role within the school. Such future research is also relevant for studies on the role of teacher leaders (i.e., teachers with (in)formal leadership roles in combination with teaching duties; Struyve et al., Citation2018). Researchers in this field discuss the skills required and whether it should be a defined or distributed, and thus informal, role (Snoek et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, Struyve et al. (Citation2018) state that there is a lack of insight into the interactions between teacher leaders and their school principal and found that some school principals find it hard to change the structures and distributions of control to facilitate teacher leadership. Another relevant study in line with this is a Norwegian study of Lorentzen (Citation2022), who found that how specialist teachers are positioned by school principals influences trust and conflict with the other staff.

The coach-teacher and school principal are two roles experienced by teachers to stimulate collaboration innovation, but we found that these two are not sufficient for higher degrees of CIP and the same applies for the influence of other horizontal and vertical working relation factors. This became especially apparent in our findings when certain schools had positive scores on all horizontal and vertical working relation factors, but still had low degrees of CIP. Our study thus indicates the complexity of stimulating CIP in schools. Future research could further study what it means for school principals’ leadership when teachers with a defined role (such as coach-teachers, teacher leaders) are or are not involved and whether involving teachers with a defined role is at odds with developments such as distributed leadership and control.

Furthermore, we did not identify middle level leaders, while they are part of the school as a (social) system and can be mediators in the vertical working relation, especially in larger (secondary) schools, and play a role in e.g. teachers’ innovative attitudes, practices, and development (e.g., Abrahamsen & Aas, Citation2016; Van der Hilst & Imants, Citation2022). Future research is needed to study middle level leadership responsibilities and practices and its position in horizontal and vertical working relations and their role in CIP.

Besides, there might be additional underlying mechanisms that further explain this complexity of working relations and CIP that we have not yet identified but future research can dive into this. Based on the literature, we might assume the influence of the fact that working relations are socially and culturally pre-programmed: ‘This is how we work around here’ (Noordegraaf et al., Citation2016). Changing working relations into working together, i.e., CIP, does not start from scratch and is a complex process (e.g., Schein, Citation1989; Schein & Schein, Citation2016). The degree of CIP might depend on the prior existence of CIP, as well as the prior existence of a collaborative mindset within the working relations. In addition, in terms of social exchange, teachers mentioned in the interviews that a collaborative mindset and exchange of resources is of importance. We had no insights into whether all teachers and all formal leaders engaged in social exchange in the working relations. Including this information in future research by asking about this in interviews or questionnaires might be helpful to further understand the results. Indeed, if only a minority of teachers exchange social resources the potential of social exchange is not reached (e.g., Paju et al., 2021; Sales et al., Citation2017; Vangrieken & Kyndt, Citation2020).

Furthermore, based on our study we see more directions for future research. Safety and collaboration between teachers was studied confirmatively with a multilevel analysis and was mentioned by teachers in interviews as part of the horizontal relation. However, safety is not only part of the horizontal relation but is an organizational property (Bryk & Schneider, Citation2002), influenced by all school members and part of the horizontal and vertical working relations. Safety is recognized to be of importance for school improvement (Bryk & Schneider, Citation2002; Tschannen-Moran, Citation2014). It might be relevant for future research to include (quantitative) measures of for instance safety in the vertical relation as well to measure this more as an organizational property. Besides, including multiple factors in a multilevel analysis would help to more resolutely state how horizontal and vertical factors associate and in which combinations these can help to enhance CIP. Lastly, studying the interaction between school board members (viz., district leaders in USA research) and school principals as part of the broader vertical relation would be an interesting contribution to understanding vertical relations of CIP, partly within and partly outside the school building. Until now, this role of school board members in relation to school principals has rarely been studied (e.g., Hooge & Honingh, Citation2014; Honig & Rainey, Citation2020).

Limitations

Firstly, the sample might have been slightly biased and influenced the results, since schools chose to participate in the program and to complete questionnaires, and the teachers voluntarily joined the group interviews. The possible slight bias is, however, partly tackled by enhancing the reliability of the results with a mixed method approach. Furthermore, the triangulation of data on a couple of the variables showed that teachers responded the same to their school principals’ leadership in the interviews and questionnaire. Secondly, regarding the interviews, we did not specifically or comprehensively ask about associations between horizontal and vertical working relation factors nor focused on the quality of CIP. Future research with an in-depth character on this aspect would be relevant to understand the working relation factors and their association even better. Furthermore, including a larger sample and studying this outside the Netherlands as well in future studies would enhance the generalizability of the results of this study. Thirdly, we were not able to predict the random multilevel models. However, the development was flat, which might be a reason behind us not being able to predict this weak relation.

Implications

Overall, based on our findings we aim to motivate schools to focus on and initiate forms of both horizontal and vertical working relations to change into more collaborative approaches. For teachers, this means that they should have a collaborative and learning attitude and take and share responsibilities together with other teachers and their school principal(s). Sharing responsibilities is not only part of the horizontal relation but also influenced by and part of the vertical relation. For school principals, this means that they need to provide a safe work environment and relations, frameworks, and professional space, be involved in collaborative-innovation practices, and be stimulating to teachers and their teaching. Furthermore, school principals must be aware that their leadership alone is not sufficient to stimulate CIP. Coach-teachers as a kind of teacher leaders with a defined role seem to be essential in addition to school principals to stimulate CIP.

Conclusion

The current study stimulates educational practitioners and researchers to focus on both horizontal and vertical working relations to be included and active to collaboratively approach innovation. We showed that teachers perceive both horizontal and vertical working relations to be able to enhance the degree of CIP. In particular the stimulating role of school principals and coach-teachers, as well as teachers who engage in social exchange, when they experience a safe working climate and relations were notable. However, our study also indicated the complexity of how working relations do not necessarily result in more CIP and points to several avenues for future research. Thus, if we want to support schools in changing an individual culture into a more collaborative approach to innovation, understanding how horizontal and vertical working relations work and can be further stimulated seems highly promising.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants in this study for their cooperation. Furthermore, we thank Prof. dr. Van der Heijden for his supervision on the multilevel analysis and Jorick Mijnans for the preliminary interview analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Questionnaire CIP (M = 15 teachers per school completed the questionnaire), Questionnaire on horizontal and vertical working relations (M = 10 teachers per school).

2 (M0: F (1.1189) = 0.189, p = 0.664; M1: F (1.863) = 0.808, p = 0.369; M2: F (1.1024) = 2.999, p = 0.084; M3: F (1.1087) = 0.217, p = 0.641).

3 The teachers also noted Facilitate and Organize teams as factors. Since these could not be interpreted in terms of horizontal or vertical relations, they were excluded from further analyses.

4 SPs’ Leadership alone: b = 0.109, p = 0.14; Safe .. alone: b = -0.003, p = 0.97

5 Time: SPs’ Leadership b = -0.015, p = 0.75, Safe .. b = 0.034, p = 0.69, Working .. b = -0.058, p = 0.52. Time2: SPs’ Leadership b = -0.001, p = 0.74, Safe .. b = -0.003, p = 0.69, Working.. b = 0.008, p = 0.24.

6 Safe to Share is not included.

References

- Abrahamsen, H., & Aas, M. (2016). School leadership for the future: Heroic or distributed? Translating international discourses in Norwegian policy documents. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 48(1), 68–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2016.1092426

- Admiraal, W., Kruiter, J., Lockhorst, D., Schenke, W., Sligte, H., Smit, B., Tigelaar, D., & de Wit, W. (2016). Affordances of teacher professional learning in secondary schools. Studies in Continuing Education, 38(3), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2015.1114469

- Admiraal, W., Schenke, W., de Jong, L., Emmelot, Y., & Sligte, H. (2021). Schools as professional learning communities: What can schools do to support professional development of their teachers? Professional Development in Education, 47(4), 684–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1665573

- Avalos-Bevan, B., & Flores, M. A. (2022). School-based teacher collaboration in Chile and Portugal. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1854085

- Azorín, C., Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2020). Taking a distributed perspective on leading professional learning networks. School Leadership & Management, 40(2-3), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1647418

- Bekkers, V., & Noordegraaf, M. (2016). Enhancing public innovation by transforming public governance. Enhancing Public Innovation by Transforming Public Governance, 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316105337.007

- Boon, A., Raes, E., Kyndt, E., & Dochy, F. (2013). Team learning beliefs and behaviours in response teams. European Journal of Training and Development, 37(4), 357–379. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591311319771

- Boyd, T. (2021). Education reform in Ontario: Building capacity through collaboration. In F. M. Reimers (Ed.), Implementing deeper learning and 21st century education reforms. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57039-2_2

- Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. Russell Sage Foundation. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.77589781610440967.

- Burke Johnson, R., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033007014

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. https://doi.org/10.1086/228943

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. L. (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed.

- Daniëls, E., Hondeghem, A., & Dochy, F. (2019). A review on leadership and leadership development in educational settings. Educational Research Review, 27, 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.02.003

- de Jong, L., Meirink, J., & Admiraal, W. (2019). School-based teacher collaboration: Different learning opportunities across various contexts. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102925

- de Jong, W. A., Lockhorst, D., de Kleijn, R. A. M., Noordegraaf, M., & van Tartwijk, J. W. F. (2022). Leadership practices in collaborative innovation: A study among Dutch school principals. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220962098

- de Jong, W. A., Lockhorst, D., Klein, T., van Tartwijk, J., & Noordegraaf, M. (2021). Over de kracht van leerKRACHT Eindrapportage van vierjarig onderzoek.

- Den Brok, P. (2018). Cultivating the growth of life-science graduates: On the role of educational ecosystems [Inaugural address]. https://edepot.wur.nl/458920.

- de Neve, D., & Devos, G. (2016). How do professional learning communities aid and hamper professional learning of beginning teachers related to differentiated instruction? Teachers and Teaching, 23(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1206524

- Dochy, F., Gijbels, D., Raes, E., & Kyndt, E. (2014). Springer international handbooks of education. In International Handbook of Research in Professional and Practice-Based Learning, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8902-8_36

- Fullan, M. (2008). The Six Secrets of Change. http://michaelfullan.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2016/06/2008SixSecretsofChangeKeynoteA4.pdf.

- Fullan, M. (2016). The new meaning of educational change. Teachers College Press.

- Grosemans, I., Boon, A., Verclairen, C., Dochy, F., & Kyndt, E. (2015). Informal learning of primary school teachers: Considering the role of teaching experience and school culture. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.011

- Hargreaves, A., & O’Connor, M. T. (2017). Cultures of professional collaboration: Their origins and opponents. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 2(2), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-02-2017-0004

- Honig, M. I., & Rainey, L. R. (2020). A teaching-and-learning approach to principal supervision. Phi Delta Kappan, 102(2), 54–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721720963234

- Hooge, E. H., & Honingh, M. (2014). Are school boards aware of the educational quality of their schools? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 1–16.

- House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage.

- Hox, J., Moerbeek, M., & van de Schoot, R. (2018). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hujala, E. (2004). Dimensions of leadership in the childcare context. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 48(1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031383032000149841

- Liou, Y. H., Daly, A. J., Downey, C., Bokhove, C., Civís, M., Díaz-Gibson, J., & López, S. (2020). Efficacy, explore, and exchange: Studies on social side of teacher education from England, Spain, and US. International Journal of Educational Research, 99(134), 101518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101518

- Liu, Y. (2020). Focusing on the practice of distributed leadership: The international evidence from the 2013 TALIS. Educational Administration Quarterly, 56(5), 779–818. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X20907128

- Lopes, J., & Oliveira, C. (2020). Teacher and school determinants of teacher job satisfaction: A multilevel analysis. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 31(4), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1764593

- Lorentzen, M. (2022). Principals’ positioning of teacher specialists: Between sensitivity, coaching, and dedication. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 25(4), 615–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2020.1737240

- Ludlow, L., Klein, K., & College, B. (2014). Suppressor variables: The difference between “is” versus “acting as.”. Journal of Statistics Education, 22(2).

- Mentink, R. (2014). Sturen op zelfsturing: Leiderschap en professionele leergemeenschappen. De Nieuwe Meso, 55–60.

- Noordegraaf, M., Schneider, M. M. E., van Rensen, E. L. J., & Boselie, J. P. P. E. F. (2016). Cultural complementarity: Reshaping professional and organizational logics in developing frontline medical leadership. Public Management Review, 18(8), 1111–1137. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2015.1066416

- OECD. (2016). Netherlands 2016 Foundations for the Future. https://www.oecd.org/netherlands/netherlands-2016-9789264257658-en.htm.

- Owen, L., Goldwasser, C., Choate, K., & Blitz, A. (2008). Collaborative innovation throughout the extended enterprise. Strategy & Leadership, 36(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/10878570810840689

- Paju, B., Kajamaa, A., Pirttimaa, R., & Kontu, E. (2022). Collaboration for inclusive practices: Teaching staff perspectives from Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1869087

- Rigby, D. K., Sutherland, J., & Takeuchi, H. (2016). Embracing agile. Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2016/05/embracing-agile.

- Rogoff, B. M. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. Oxford University Press.

- Sahlberg, P. (2010). Rethinking accountability in a knowledge society. Journal of Educational Change, 11(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-008-9098-2

- Sahlin, S. (2023). Teachers making sense of principals’ leadership in collaboration within and beyond school. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 754–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2022.2043429

- Sales, A., Moliner, L., & Francisco Amat, A. (2017). Collaborative professional development for distributed teacher leadership towards school change. School Leadership & Management, 37(3), 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2016.1209176

- Schein, E. (1989). Organizational culture and leadership. Jossey Bass.

- Schein, P. A., & Schein, E. H. (2016). Organizational culture and leadership. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Seawright, J. (2016). The case for selecting cases that are deviant or extreme on the independent variable. Sociological Methods & Research, 45(3), 493–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124116643556

- Serdyukov, P. (2017). Innovation in education: What works, what doesn’t, and what to do about it? Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 10(1), 4–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-10-2016-0007

- Siisiainen, M. (2003). Two concepts of social capital: Bourdieu vs. Putnam. International Journal of Contemporary Sociology, 40(2), 183–204.

- Sinnema, C., Daly, A. J., Liou, Y. H., & Rodway, J. (2020). Exploring the communities of learning policy in New Zealand using social network analysis: A case study of leadership, expertise, and networks. International Journal of Educational Research, 99(September), 101492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.10.002

- Snoek, M., Hulstbos, F., & Andersen, I. (2019). Teacher leadership Hoe kan het leiderschap van leraren in scholen versterkt worden? www.hva.nl/teacher-leadership.

- Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2017). Metagoverning collaborative innovation in governance networks. The American Review of Public Administration, 47(7), 826–839. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074016643181

- Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2018). Co-initiation of collaborative innovation in urban spaces. Urban Affairs Review, 54(2), 388–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087416651936

- Spillane, J. P., & Sherer, J. Z. (2004). A distributed perspective on school leadership: Leadership practice as stretched over people and place. American Educational Research Association, 1–50.

- Struyve, C., Hannes, K., Meredith, C., Vandecandelaere, M., Gielen, S., & de Fraine, B. (2018). Teacher leadership in practice: Mapping the negotiation of the position of the special educational needs coordinator in schools. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62(5), 701–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1306798

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using Multivariate Statistics (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Thompson, G., & Glasø, L. (2018). Situational leadership theory: A test from a leader-follower congruence approach. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 39(5), 574–591. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-01-2018-0050

- Thumlert, K., Owston, R., & Malhotra, T. (2018). Transforming school culture through inquiry-driven learning and iPads. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 3(2), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-09-2017-0020

- Tolo, A., Lillejord, S., Flórez Petour, M. T., & Hopfenbeck, T. N. (2020). Intelligent accountability in schools: A study of how school leaders work with the implementation of assessment for learning. Journal of Educational Change, 21(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-019-09359-x

- Torfing, J. (2016). Collaborative innovation in the public sector. Georgetown University Press.

- Torfing, J. (2019). Collaborative innovation in the public sector: The argument. In Public management review (Vol. 21, Issue 1, pp. 1–11). Taylor and Francis Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1430248

- Tschannen-Moran, M. (2014). Trust matters: Leadership for successful schools (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Van der Hilst, B., & Imants, J. (2022). Inrichting van de schoolorganisatie. In L. van Wessum, A. van Ros, & P. Runhaar (Eds.), De schoolleider in verandering. Theorie en praktijk (pp. 9–15). https://deleiderschapsagenda.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ipdf-Leiderschapspraktijken.pdf

- Vangrieken, K., Dochy, F., Raes, E., & Kyndt, E. (2015). Teacher collaboration: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 15, 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.04.002

- Vangrieken, K., & Kyndt, E. (2020). The teacher as an island? A mixed method study on the relationship between autonomy and collaboration. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 35(1), 177–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-019-00420-0

- Vanlommel, K. (2021). Organiseren van complexe verandering in onderwijs [Openbare les] https://www.hu.nl/-/media/hu/documenten/nieuws/openbare-les-kristin-vanlommel.ashx.

- van Schaik, P., Volman, M., Admiraal, W., & Schenke, W. (2019). Approaches to co-construction of knowledge in teacher learning groups. Teaching and Teacher Education, 84, 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.04.019

- van Schaik, P., Volman, M., Admiraal, W., & Schenke, W. (2020). Fostering collaborative teacher learning: A typology of school leadership. European Journal of Education, 55(2), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12391

- Verbiest, E. (2021). Perspectieven op onderwijsvernieuwing. Gompel & Svacina.

- Wubbels, T., & Van Tartwijk, J. (2018). Dutch teacher and teacher education policies: Trends and ambiguities. In H. Niemi, A. Toom, A. Kallioniemi, & J. Lavonen (Eds.), Teacher’s role in changing global world: On resources and challenges related to the teaching profession (pp. 63–77). Brill / Sense.

- Zhang, J., & Zheng, X. (2020). The influence of schools’ organizational environment on teacher collaborative learning: A survey of Shanghai teachers. Chinese Education & Society, 53(5-6), 300–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/10611932.2021.1879553

- Zimmerman, B. J., Lindberg, C., & Plsek, P. E. (1998). Edgeware: Insights from complexity science for health care leaders. VHA Publishing.

Appendix 1:

Horizontal and vertical questionnaire scales

Working on lessson practices

I provide feedback to colleagues on what is going well.

I provide feedback to colleagues on what could be better.

I regularly talk with colleagues about education.

I regularly exchange lesson practices with colleagues from other schools.

I design new lesson practices together with colleagues.

I ask colleagues to visit my lessons and give feedback.

My colleagues and I collaborate on studying our own lesson practices.

Safe to Share

I share problems from my teaching practice with colleagues.

I regularly talk about educational content with colleagues.

I am open to feedback from my colleagues.

I feel safe enough to share with colleagues problems that I encounter in my work.

In difficult situations I can count on the support of my colleagues.

I feel like I am not alone with regard to teaching my class.

My colleagues are genuinely interested in how I am doing as a teacher.

School principals’ leadership

The school principal(s) challenges me and my colleagues to examine problems in our teaching practice.

The school principal(s) regularly visits my lessons.

The school principal(s) regularly visits team meetings.

The school principal(s) removes obstacles allowing me to focus on my classes.

The school principal(s) develops the school's vision in collaboration with all teachers.

The school principal(s) adjusts their own actions in response to feedback.

The school principal(s) discusses my personal goals with me.

The school principal(s) encourages me and my colleagues to be the best teachers we can be.

The school principal(s) encourages me and my colleagues to implement solutions to problems in our teaching practice.

The school principal(s) asks me for feedback .