ABSTRACT

Since the beginning of the new millennium, the Norwegian education system has shown a growing inclination towards performance-based management. This mixed-methods study aims to gain a deeper understanding of Norwegian primary school teachers’ perceptions of the implementation and application of the National Quality Assessment System. The results revealed that teachers’ professional agency is influenced by the changes in structure and content driven by performance-based management. The teachers perceived that the national testing process offers valuable insights into students’ performance, but it falls short in providing novel information that could enhance individualized instruction. Significant gender differences were discovered concerning the perceived importance, motivation, and influence of national testing on pupils in the primary school setting. This was evident in both the quantitative and qualitative findings of this study. The findings are discussed in light of current educational practices, existing research, and implications for future directions.

Introduction

Around the turn of the millennium, Norway implemented reforms in its public education system, aligning with new international organizational trends (Eakin et al., Citation2011; Giddens, Citation1984; Hall et al., Citation2015), also referred to as New Public Management (NPM) (for review see Hood & Dixon, Citation2016). In the wake of NPM, curriculum control and performance-based practices, through which teachers and educational leaders are held accountable for individual students` test results, have become a consistent practice in primary education in Norway (e.g., Mausethagen & Mølstad, Citation2015; Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2022b). In the year 2000, Norway showed disappointing results from the first Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), trailing behind other comparable OECD countries (Østerud, Citation2016). Termed the “PISA shock” in Norwegian media, these results sparked changes in Norwegian educational policy (Sjøberg, Citation2014). The average performance in the PISA 2000 test led to significant concern, with media coverage highlighting Norway's perceived shortcomings in education. Former Minister of Education and Research, Kristin Clemet, expressed disappointment, drawing parallels to returning from the Winter Olympics without a single Norwegian medal (Ramnefjell, Citation2001). Since then, enhancing competency levels in both primary and higher education has become a top priority within the Norwegian education system (Jensen et al., Citation2020; St. meld. nr. Citation30, Citation2003-Citation2004). The proposal for a national quality assessment system, including national large-scale school testing, was supported by Parliament (St.meld. 10 2003–2004). When compared to countries such as England and The United States, the shift towards an accountability-centred school policy, based on measurable performance targets, came relatively late to Norway (Smith & O’Day, Citation1990). The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (UDIR) was established in 2004 to serve the Ministry of Education, municipalities, and schools with national testing programmes, learning assessment, and teaching resources (Thuen, Citation2017). The first national tests were conducted in the spring of 2004 (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2022a).

The Norwegian national tests are constructed upon a standardized large-scale testing system that encompasses diverse dimensions of curriculum-based performance objectives, akin to those observed in internationally recognized assessments such as PISA, International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), and Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS). Large-scale educational testing typically seeks to assess a specific set of curriculum standards with accuracy and efficiency, employing a standardized scoring system. The resulting scores are intended to be comparable across individuals, groups, schools, and/or nations (Chudowsky & Pellegrino, Citation2003; Tobin et al., Citation2016). The national tests in Norway cover mathematics, reading, and English for 5th and 8th grade pupils, as well as mathematics and reading for 10th grade pupils. The mathematics and reading tests focus on measuring foundational skills outlined in the general part of the curriculum, which include mathematics, reading, writing, digital skills, and oral skills (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2020). The mathematics test evaluates the pupils’ abilities to recognize, describe, use, process, and reflect on mathematical problems (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2022a). Despite initial political support, national tests were temporarily halted for evaluation in 2004, following critical public feedback (Sjøberg, Citation2022). They resumed in 2007 and have continued since, with ongoing efforts to evaluate and enhance their contents and format (Soløst, Citation2023).

The test formats used in Scandinavian countries, as well as in other nations like Australia, South Korea, and Canada, can be classified as low to mid-stakes accountability testing (Gunnulfsen & Roe, Citation2018; Hargreaves, Citation2020). Like high-stakes testing, mid-stakes and low-stakes testing refer to large-scale assessments designed to transparently evaluate and compare performance outcomes and progress within and across schools. These tests serve the purpose of identifying areas for improvement and specific performance targets (Hargreaves, Citation2020; Harris & Herrington, Citation2006; Lee & Kang, Citation2019). Moreover, both high-stakes and mid-stakes tests provide results that are publicly accessible. School administrators and leaders are responsible to achieve new proficiency standards, which are established through a comparison of test results within and between schools (Elstad et al., Citation2009; Hargreaves, Citation2020). Low- and mid-stakes tests do not entail high-stakes consequences such as the withdrawal of salary advances, replacement of principals and teachers, reduced funding, and damage of reputation. Although punitive practice has persisted in many states in the U.S. and England (Hargreaves, Citation2020), Norway does not experience such high-stakes implications. The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training emphasizes the significance of school owners and leaders engaging in discussions about follow-up measures, understanding the reasons behind the results, and determining appropriate interventions. Furthermore, the Directorate suggests that these discussions should also take place at the individual school level (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2022b). Less effort has been invested in understanding Norwegian teachers’ perception of the national tests and how these are interpreted and followed up.

Review of research

Teachers’ perceptions of accountability testing

While there is a lack of studies directly examining teachers’ perceptions of curriculum assessment through national testing in Norway, several studies have been conducted in the United States since the increase of accountability testing in schools towards the end of the 1970s. Several studies assessing teachers’ perceptions of high-stakes accountability testing in various states in the U.S. have identified effects such as unfavourable competition between schools, motivational issues, turnover among teachers, and teaching for the test practices (Gordon & Reese, Citation1997; Jones & Egley, Citation2004; Reese et al., Citation2004; Wright & Choi, Citation2006). Ethical issues related to high-stakes testing, including altering answers, dismissing low-achieving students from taking the test, and presenting actual test items for practice have been reported in several studies in the U.S. (e.g., Heilig & Darling-Hammond, Citation2008; Kher-Durlabhji & Lacina-Gifford, Citation1992). A case study exploring a science teacher's identity within a high-stakes test environment, revealed tension between teaching and prioritizing high-stakes tests, leading to a de-emphasis on activity-based science teaching (Upadhyay, Citation2009). A decreased use of discovery learning in science subjects was also reported as a consequence of a newly introduced high-stakes test regimens in British Columbia (Wideen et al., Citation1997). A more recent study reported weaknesses in high-stakes testing, including pressure and its invalid way of assessing knowledge (Gunn et al., Citation2016).

A study surveying Australian teachers’ perceptions of the National Assessment Plan—Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) found that teachers were either choosing or being instructed to prepare for the test. The study revealed that less time was spent on other curriculum areas, as well as a decrease in engagement among students (Thompson & Harbaugh, Citation2013). A research study conducted with 360 teachers across three American states found that heightened testing stakes were positively associated with improved outcomes. An increased emphasis on interpreting standards through the lens of test results was also identified (Clarke et al., Citation2003). In China, teachers initially considered high-stakes testing as pertinent for educational objectives. Nevertheless, in comparison to high-stakes assessments, teachers regarded low-stakes testing as significantly more indicative and informative in terms of gauging improvement, guiding teaching practices, enhancing learning outcomes, and ensuring school accountability (Chen & Teo, Citation2020). A study investigating Canadian teachers’ perceptions of accountability testing within a low-stakes context found that teachers in general gave the programme a low rating, especially pointing out concerns with the accountability purpose of the programme (Klinger & Rogers, Citation2011). A more recent mixed-methods study comparing Norwegian and Chilean teachers’ interpretations of accountability testing found that teachers in both contexts were generally critical of the validity and fairness of such test regimens. The main difference was primarily related to the potential negative consequences of poor test results in the Chilean school system (Camphuijsen & Parcerisa, Citation2023). A study investigating teachers’ and principals’ perception of national large-scale assessment in Israel-GEMS, revealed that teachers primarily perceive national assessment as summative and accountability-focused. In contrast, principals mainly emphasized the formative aspects of the test (Klieger, Citation2016). A Norwegian study investigating the role of external and internal accountability, revealed that teachers adapted and accepted its rationales for assuring academic development, while also resisting external and internal accountability as a threat to the broader goals of education (Mausethagen, Citation2013). Broader goals have also been emphasized by scholars advocating for a transition from a performance-based assessment system to a formative mastery-based approach focusing on the specific needs of individual schools and students (Shepard et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, there is a substantial body of research supporting the many advantages of a mastery-based learning environment emphasizing task-relevant feedback rather than normative external judgement, control and/or rewards (DeCharms & Muir, Citation1978; Dweck, Citation1999; Leggett, Citation1988). As such, a study investigating how stakeholders (i.e., teachers, school leaders and students, local leaders, members of the directorate and government) perceived a government-initiated, large-scale policy implementation programme on Assessment for Learning (AfL) in Norway, found that successful implementation was associated with trust and autonomy-support among schools and teachers. Less successful implementation was the case when schools and teachers perceived the assessment as a means for control. The programme did not have an effect on the students’ performance (Hopfenbeck et al., Citation2015).

Implications of accountability testing

While large-scale accountability testing was implemented in the Scandinavian countries just after the turn of the millennium, other countries such as the U.S. and England paved the way for such testing from the end of the 1970s. The effectiveness of the national curriculum assessment in England, introduced in 1988, was examined by the government in 2008. The report found that test results improved between 1988 and 2000. However, high-stakes test environments had multiple unintended consequences. The report concluded by recommending a greater use of formative assessment strategies accompanied by sampled tests at a national level (Stobart, Citation2009; Wyse & Torrance, Citation2009). A more recent mixed-method study conducted in Israel revealed that teachers mainly perceived the test as unreliable, controlling, and unrelated to school curricula. Consequently, test results were hardly applied for any other pedagogical purpose than “teaching for the test” practice among some teachers (Arviv Elyashiv & Avidov-Ungar, Citation2023). Another recent study found that national testing in Sweden was associated with school-related stress and a reduction in academic self-esteem among Swedish seventh graders. These effects indirectly affected psychosomatic symptoms and life satisfaction for pupils, with the negative effects being generally stronger for girls (Högberg et al., Citation2021). In contrast, an English study from the same year found that Stake 2 tests in England were not related to lower levels of happiness, enjoyment of school, self-esteem, and mental wellbeing among pupils (Jerrim, Citation2021).

The consequences of abolishing accountability testing are less known. As such, a Scottish study investigating this phenomenon found that grade 6 science teachers (n = 600) perceived test preparation as narrowing the curriculum. A preliminary consequence of omitting grade 6 school testing in science, was an increase in the application of activity-based learning methods and investigative learning procedures (Collins et al., Citation2010). Finally, teachers’ societal status and appreciation have decreased during the last century (Thuen, Citation2017). An interesting study investigating determinants of societal appreciation among 66,593 teachers in Europe found that the overall accomplishment in PISA scores predicted perceived societal appreciation. The study concluded that expressing a crisis mentality towards low PISA scores seemed to strengthen the underappreciation and status of teachers (Spruyt et al., Citation2021). Accountability testing in general, especially high-stakes testing, seem to be an intricate and slightly paradoxical phenomenon (Wiliam, Citation2010). High-stake testing is strongly associated with a consistent increase in academic performance across different contexts (e.g., Amrein & Berliner, Citation2002). However, the positive effects may be outweighed by unintended consequences, such as an increase in drop-out rates, turnover among teachers, and “teaching for the test effects” (Wiliam, Citation2010).

Following up national curriculum testing in Norway

Following the public guidelines for education in Norway (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2022b), “results meetings” have been introduced, wherein teachers and school leaders discuss the implications and implementation of national test results at the local level. A study investigating the content of such meetings found that teachers drew upon a rich knowledge base when discussing relatively thin test results, typically suggesting strategies to improve subsequent test results in the short term (Mausethagen et al., Citation2018). The same research group examined how educational administrators in various Norwegian districts used data from national testing differently. The findings revealed that policy goals, as defined in key policy documents, were transformed, and adapted into different governing styles. This resulted in a shift of focus towards primary goals in some instances, while in others, the goals were extended and enhanced (Prøitz et al., Citation2021). Consistent with previous findings, another study revealed that school testing played a less prominent role in guiding school results. Yet, school leaders perceived information from national test results as beneficial for enhancing individual student learning (Gunnulfsen, Citation2017).

Different agents within the school system assumed different roles (Gunnulfsen, Citation2017). Leaders tended to be enthusiastic, managers and team leaders act as messengers, and teachers serve as critics and preventers of overburdening. Consequently, communication between hierarchies overshadowed the possibilities of using national test results (Gunnulfsen, Citation2017). Further, a recent review found that teachers generally have low efficacy in applying student data to address important identified weaknesses effectively (Sun et al., Citation2016). Similarly, school leaders in Norway expressed enthusiasm for national school testing as a method for quality enhancement. However, the extent to which the results were corroborated and deliberately applied in subsequent improvement was limited (Seland et al., Citation2015).

The purpose of this study is to gain a better understanding of the perceptions held by Norwegian teachers regarding the national curriculum testing implemented in primary school, as well as their perceptions of the educational and pedagogical implications. In addition, this study aims to investigate potential gender effects, differences between experienced and less experienced teachers, and variations in attitudes among teachers in Oslo and Inland Norway. With this in mind, the research questions for this study are as follows:

What are primary school teachers’ perceptions of the Norwegian national test programme?

Are there any differences in perceptions of the national test programme among primary school teachers based on gender, geographical location, and the duration of work experience?

Methods

Research design

The present study applied a mixed-methods approach (i.e., explanatory sequential design) combining statistical trends with stories and personal experience. According to Creswell (Citation2015, p. 2) mixed-methods “provide a better understanding of the research problem than either form of data alone”. The present study's mixed methods design was based on an explanatory sequential research design (Quan + Qual) where one initiates the investigation with quantitative methods to gather and analyse data, followed by the application of qualitative methods to delve deeper into and elucidate the results obtained from the quantitative analysis (Soløst, Citation2023). The advantage of an explanatory sequential research design lies in its comprehensibility, as the different phases are built upon one another (Creswell, Citation2015).

Quantitative procedures

During the autumn of 2021, the present study's two authors developed an electronic survey that aligned with the primary research objectives. The survey aimed at gathering information about attitudes and trends regarding mandatory national school tests in primary school. Background variables were incorporated to capture potential variations in these attitudes and trends across gender, work experience and the geographical location of schools. To assess the questionnaire's reliability and validity, it was piloted by two different groups (Marshall, Citation2005). First, adult family members (husband and two daughters) of one of the authors completed the questionnaire to assess its technical functionality, as well as the comprehensibility of instructions and items. Second, the questionnaire was given to four primary school teachers, including both novice and experienced teachers. They were asked to provide feedback on the clarity and suitability of the questions and instructions. Additionally, they were asked if any important questions were missing based on the main purpose of the study, to assess content validity. The time taken to complete the questionnaire (between 3 and 5 minutes) was recorded in both pilot tests. Subsequently, the survey was distributed electronically to principals of selected primary schools in the municipality of Oslo and Inland Norway (Innlandet), targeting grades 1–7. The principals were requested to share the questionnaire with teachers in their respective schools (i.e., convenience sample) (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation1994). Participants were assured of the questionnaire's anonymity, which was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data. Additionally, the questionnaire included a recruitment request for follow-up interviews. A friendly reminder was sent to the selected schools one week after the initial participation invitation before closing the recruitment process (Soløst, Citation2023). The statistical analyses for this study were carried out using IBM SPSS version 30.

Participants

A total of 117 teachers, consisting of 64.1% females and 35.9% males, participated in the survey. The teachers were from two regions: Innlandet, accounting for 71.8% of the participants, and Oslo, accounting for 28.2%. Regarding teaching experience, 19.7% of the teachers had between 0 and 5 years, while another 19.7% had between 6 and 10 years of teaching experience. Additionally, 29.9% of the teachers had accumulated between 11 and 20 years of teaching experience, and 30.8% had been teaching for more than 21 years. The distribution of teachers was nearly equal between those working in urban areas (46.2%) and those in rural areas (53.8%).

Measures

The questions developed for the present study were designed for descriptive purposes rather than for making inferences. However, an exploratory factor analysis was carried out to explore possible independent factors. The analysis failed to find sensible distinct dimension. As such, subsequent internal consistency testing was neither feasible nor relevant for the statistical tests carried out in the present study.

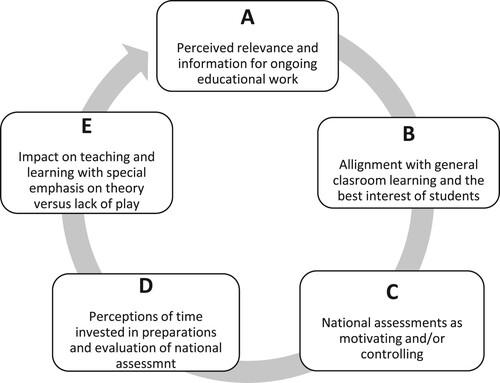

In addition to the background variables, the 14 continuous variables were categorized into five groups based on the scope and the aim of the present study (see and ). The items were entirely developed by the authors of the present study based on the research context, population, and aims (Soløst, Citation2023).

Table 1. Overview of the study's five main categories depicted in different colours from category A to category E.

Qualitative procedures

In order to supply and enrich this study's quantitative findings, semi-structured interviews (Kvale, Citation2007) were conducted. The goal was to conduct interviews with both a female and male teacher from both Oslo and Inland Norway. An option for participants to indicate their interest in participating in an interview was included as an option in the questionnaire distributed. In total, 14 individuals expressed their interest. To ensure diversity in perspectives, geographical representation, and gender, the responses from the questionnaire were reviewed in advance before sending out invitations. Finally, interviews were carried out with two teachers with contrasting backgrounds and demographics. A semi-structured interview approach was chosen as it allowed the themes from the questionnaire to be adapted into a flexible interview guide (Brinkmann & Kvale, Citation2018; Soløst, Citation2023).

The two interviews were conducted by the second author of this article. One of the interviews were carried out at the school where one participant is employed, while the second interview was conducted remotely using Teams. To ensure backup recordings, two mobile phones equipped with the Nettskjema voice recorder application (i.e., software solution for gathering research data) were utilized during each interview. Prior to commencing the interviews, casual conversation was initiated to foster a relaxed atmosphere conducive to a more authentic exchange. Moreover, a briefing session was conducted to clarify the interview's subject matter and the procedural aspects involved (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2021, p. 160). Subsequently, the recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by utilizing the audio player functionality within the Nettskjema software into a Word document. The decision was made to forgo adherence to transcription conventions (e.g., nods, face expressions, body language etcetera) (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2021, p. 209), opting instead to faithfully reproduce the spoken words, including appropriate punctuation. Additional transcription beyond this scope was deemed irrelevant for the purposes of the interview, given its focus on professionals expressing their opinions within their occupational context, devoid of personal content or sensitive topics (Soløst, Citation2023).

Participants

Teacher 1 is a female aged 30–39 who works at an urban school in Innlandet County, and Teacher 2 is a male teacher aged 40–49 who works at a school in the western part of Oslo. Both teachers teach 5th grade and have thus administered national tests with their respective classes during the same year of the interviews. Both schools predominantly achieved results slightly above the national average.

Analysis

The qualitative analysis was mainly carried out by the second author, yet in collaboration with the first author. Inter-rater reliability analysis was not conducted (McDonald et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, deliberate discussions regarding the relevance and functionality of codes based on key sentences, as well as the transformation of codes into main themes were ongoing. Thematic analysis (TA) was chosen for analysing the two interviews. TA is a versatile method that allows a multitude of philosophical and theoretical approaches (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Thematic analysis involves four distinct steps comprising the following content:

Familiarization: This initial step involves gathering and obtaining an overview of the data. In our study, this entailed conducting interviews and subsequently transcribing them.

Coding: During this phase, significant aspects of the transcribed text were identified and preliminarily selected. Several rounds of underlining and highlighting relevant topics in order to grasp essential aspects of the overall data were carried out. The final round comprised documentation and consolidation of mini-themes.

Theme-development: This step involved a back-and-forth process between coding and categorizing. The material was subjected to a thorough re-examination, employing colour highlighting to systematically arrange it into distinct themes. This categorization process was necessitated by the ongoing discovery of new textual elements.

Reviewing the fit between the codes and the themes: Certain aspects presented challenges in terms of categorization, as they demonstrated potential relevance to multiple categories. In order to uphold analytical coherence, deliberate decisions were made in such instances.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The first category concerning perceived relevance and importance of national testing (question A1: M = of 4.62) indicates that most teachers in the present study perceive that national tests generate valuable and relevant information concerning their students’ academic level. However, the teachers did not perceive the information generated by test results as novel information (A2: M = 3.96). Most teachers in this study do perceive that national testing facilitates the catering of the students’ individual needs (M = 3.62). Moving on to the second category (B1 and B2), significantly lower mean scores are observed (M = 3.16; M = 3.28). These results indicate that teachers perceive national assessments as a less important component of their students’ learning process, as well as an instrument that is not in the best interest of their students. The lowest mean score obtained in this study was for question C1 (M = 2.97), indicating that mandatory national assessments are viewed as an unmotivating aspect of the teachers’ overall role as professionals. The majority of the teachers perceive national assessments as a controlling element in their role as teachers (C2: M = 4.28), primarily serving as a tool for controlling and ranking schools (C3: M = 4.86). Furthermore, most teachers do not perceive the time invested in the preparation and evaluation as valuable (D1: M = 3.56). However, most teachers report that the schools they work in engage to some extent in both pre- and post-test work (D2: M = 4.47; D3: M = 4.65). Finally, regarding questions indicating the extent to which the youngest pupils in grades 1–4 are affected by preparations for upcoming national assessments, neutral mean scores are observed (E1: M = 3.83; E2: M = 4.36; and E3: M = 4.25). Yet, there appeared to be a tendency towards perceiving the learning context of the youngest children as theoretical and less playful due to a focus on test preparations ().

Table 2. Overview of central tendency and spread of the teachers’ answers within the data set.

Independent samples t-test

To compare the mean values of gender, geographical location, and work experience (i.e., seniority) on the continuous variables, an independent samples t-test was conducted (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013). To gain a better understanding of the magnitude of any significant difference, the t-test was followed by Cohen's d test, which measures effect sizes based on percentage differences between the measured means of two continuous variables (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013).

The results of the t-test revealed that female teachers (M = 5.15, SD = 1.52) perceive national assessment as a tool for control and the ranking of schools to a greater extent than male teachers (M = 4.36, SD = 1.80): t(115) = −2.51, p = .01 (d = −.49), indicating a moderate effect. Furthermore, the t-test found that male teachers (M = 3.38, SD = 1.95) generally perceive national assessment as more motivating compared to females (M = 2.75, SD = 1.52): t(115) = 1.96, p = .05 (d = .38). Male teachers also reported a higher overall perception of the importance of national assessment (M = 3.60, SD = 1.46) compared to female teachers (M = 2.92, SD = 1.42): t(115) = 2.43, p = .01 (d = .47). Finally, it was found that male teachers (M = 4.02, SD = 1.30) believe, to a significantly greater extent than female teachers, (M = 2.87, SD = 1.59) that national assessment are in the best interest of the students: t(115) = 3.67, p < .001 (d = .71). The assessed teachers in Oslo (M = 3.00, SD = 1.79) consider national assessment as a means for the students’ benefit to a greater extent than teachers in Inland Norway (M = 3.05, SD = 1.64): t(115) = 2.39, p = .01 (d = .49). The results of the t-test show that less experienced teachers with 0–10 years of experience (M = 5.30, SD = 1.38) view national assessment as a means of controlling and ranking schools more than experienced teachers with over 10 years of work experience (M = 4.58, SD = 1.77): t(115) = 2.35, p = .02 (d = .45). Other significant differences were not found between male and female teachers, nor between teachers in Oslo and Inland Norway, and between novice and experienced teachers (Soløst, Citation2023).

Qualitative findings

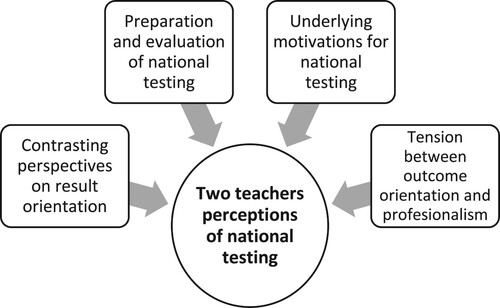

The qualitative analyses yielded four distinct main themes, as illustrated in . This section is structured accordingly based on these four identified themes (Soløst, Citation2023).

Different orientational perspectives

In relation to general perspectives on national testing, the two teachers hold different views. Teacher 2, a male teacher from Oslo, articulates that all students should attend national examinations as they enable the comparison of results and monitoring of long-term progress. Notably, he highlights an instance where a school exempted 30% of its students from the test. Using mathematics as an example, he contends that it may be more harmful for students to remain oblivious to their deficiencies in the subject throughout the academic year than to undergo the national testing.

Teacher 1 maintains that national assessments may yield advantageous outcomes for average to high achieving pupils. However, she argues that academically challenged pupils face a different scenario, as the complexity of the tests surpasses their cognitive abilities, thereby impeding them from showing their true abilities. Furthermore, teacher 1 believes that play has a limited role in schools:

Play is a beautiful gateway to learning. […] In connection with the increasing number of school refusers, more high-achieving girls, more stress … mental health etcetera. I can see that very clearly with my current students. And I think it's because there is too much academic pressure too early on (Soløst, Citation2023, p. 65).

Preparation and evaluation of national testing

Teacher 1 explains that there is little emphasis on pre-test work at her school in Innlandet. Instead, alternative texts are used for discussions and recreational activities. During test situations, the teachers emphasize the importance of identifying areas where their teaching may have been inadequate, rather than focusing solely on assessing the knowledge of the students. According to Teacher 1, this approach serves to alleviate student stress. She acknowledges that several texts in the tests may be lengthy for certain students. However, she asserts that they are of good quality. Furthermore, she contends that the test results are not surprising in terms of the students’ achievement level. Yet, she points out that they can still be applied as a valuable tool for identifying areas that demand further practice. However, she expresses concern about the challenges she encounters when interpreting and comprehending the test results as a whole.

Teacher 2, at the school located in the western part of Oslo, affirms that the approach to national tests varies significantly across different schools. In his previous employment at a school located on the opposite side of the city, intensive preparation for the test was conducted. This involved extensive practice using multiple sets of tests from previous years. At his current school, Teacher 2 observes that minimal preparation is conducted for the students, and they rely on test tasks provided by UDIR. Simultaneously, he notes that he has administered previous tests on multiple occasions for amusement. He has observed that students perform better in subsequent attempts when they are familiar with the test format. Consequently, he posits that favourable results not necessarily indicate subject knowledge but rather the students’ familiarity with the test structure. Teacher 2 primarily focuses on analysing results at the group level and expresses scepticism regarding their applicability for individual adaptations.

Both the schools in Inland Norway and Oslo have result meetings to review test results and identify areas that require further attention. The teacher in Oslo also discusses the test results with his students, which both he and the class find interesting. Finally, compared to previous years, both teachers perceive that the work around national tests focuses less time on preparation and evaluation.

Perceptions of the underlying motivations for national assessments

There is a disagreement between the two teachers regarding the purpose of national exams. Teacher 2 believes they aim to identify top-performing schools and facilitate comparisons (i.e., performance-orientation). The Innlandet teacher sees them as contributing to improved student learning (i.e., mastery-orientation). However, warning against potential negative effects on the pupils’ health and well-being. Notably, both teachers believe there has been a deviation from the original intention. Teacher 2 argues that the focus on personalized education overshadows the potential benefits of comparing schools, while Teacher 1 contends that national exams as assessment tools often receive less attention due to the media coverage of the schools’ performance.

Even though Teacher 1 perceives the intention behind testing is to evaluate students and apply the results to modify classroom practice, she acknowledges that her perception does not necessarily align with reality. As such, she mentions an unfortunate cultural phenomenon surrounding media coverage of schools’ results. According to her, such coverage does not necessarily portray the true quality of schools, and the emphasis on school ranking may overshadow the purpose of assessment. On the other hand, Teacher 2 expresses that:

Right-wing politicians like Clemet had a point when they argued that by being able to identify successful schools, one might learn something from them. It has also become more common for them (the politicians) to argue that you assess to see how each student perform … , and what each individual student needs to work on. (Soløst, Citation2023, p. 66).

Tension between result orientation and professional responsibility

The two teachers perceive the conflicting expectations between an orientation towards result on the one hand, and professional responsibility in varying ways on the other. Teacher 1 holds the view that these tests offer a limited basis for evaluating instructional quality, expressing concern about marginalization of important student qualities, such as empathy, in favour results. On the other hand, Teacher 2 favours the pedagogical application of results through national testing. However, he acknowledges the potential for an excessive emphasis on outcomes.

Furthermore, Teacher 1 provides a notable example of how accountability testing tends to be less high-stakes-oriented as compared to potential consequences faced in the past:

In the past, one would at times be `called on the carpet` if the test didn't go well. I used to find it very difficult to cope with the pressure and potential scrutiny we faced as a consequence of demonstrating low test scores (Soløst, Citation2023, p. 67).

In the preparation period of national testing, a significant amount of hours and resources were taken from other subjects, prioritizing the three subjects relevant for the upcoming test. There was no direct order from the school management to do so, but it was a common practice leading up to national assessments in general (Soløst, Citation2023, p. 67).

Teacher 2 reports that he has encountered opposition from many colleagues towards national testing due to the external pressure associated with them. Teacher 1 highlights that schooling extends beyond quantifiable attributes, emphasising qualities such as empathy and inclusivity. With regard to students, she finds it challenging that only their test results are deemed relevant. To illustrate her point, she provides an example involving one of her students:

I once identified a restless child who clearly did not possess the disposition to remain seated for two hours; however, he managed to do so regardless. Despite his mind wondering elsewhere, he continued to work diligently. Nevertheless, his test result was not outstanding. Still, the fact that the student endured the ordeal represents a personal triumph in itself. (Soløst, Citation2023, p. 68).

Discussion

The aim of this study is twofold: First, to investigate primary school teachers’ perceptions of the Norwegian national test programme, and second, to explore differences in perceptions of the national test programme among primary school teachers based on gender, geographical location of schools, and years of work experience.

Both the quantitative and qualitative findings indicate that teachers in the present study perceive national testing as a valuable and relevant source of information regarding their students’ academic abilities (M = 4.62). This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating a positive attitude towards the information derived from national testing (e.g., Mausethagen, Citation2013). However, most teachers did not perceive test results as providing new or novel information regarding their students’ level (M = 3.92). The findings also indicated that most teachers do not see national testing as a means to meet individual needs (M = 3.62). This finding is consistent with Collins et al., (Citation2010) who discovered that grade 6 teachers felt that spending time on test-related topics limit opportunities for individual hands-on learning and practical activities. The finding may also be linked to low motivation and persistence in following up on specific test results (Seland et al., Citation2015). In fact, the lowest mean score (M = 2.97) obtained in the present study regarded perceived motivation towards national testing. This outcome was anticipated based on previous research, which has demonstrated a similar inclination towards the motivational aspects of compulsory assessment in schools in general (Arviv Elyashiv & Avidov-Ungar, Citation2023; Gunnulfsen & Roe, Citation2018; Wright & Choi, Citation2006).

The present study demonstrated several unexpected gender effects. Compared to female teachers, male teachers perceive testing as more important for their students learning (d = .47). Male teachers were also more motivated than female teachers in regard to the overall implementation of national assessment (d = .38). The strongest gender effect (d = .71) obtained in this study showed that male teachers perceive national assessment as being in the best interest of the students to a much greater extent than female teachers. A similar tendency appeared in the interviews. In the absence of prior research emphasizing gender disparities in this field, it may be both reasonable to speculate whether these gender differences may be explained by previously reported gender effects (d = 1.18) on the people –things dimension within the big five personality framework (Lippa, Citation2010). As such, male teachers may be more inclined to demonstrate interest in the technicalities of generalizable testing as a tool per se than female teachers. Future research should explore this notion further. Furthermore, the teachers in Oslo regarded national testing as more important than the teachers in the Innlandet region (d = .49). This may be attributed to the substantial focus and political efforts directed towards the school system in Oslo, which has been selected as a positive example for other regions in terms of national testing (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2022a). However, it is impossible to generalize this notion based on the low sample size of teachers from Oslo in the present study. Yet, both teachers and parents in Oslo have actively warned against an overemphasis on testing and external control through parental movements, discussions and demonstrations (Elstad, Citation2009; Skedsmo & Camphuijsen, Citation2022).

Most teachers in the present study perceived national testing as a controlling factor in their overall work (M = 4.86). They viewed national assessment primarily as a tool for exerting control and ranking schools. Female teachers held this perception to a significantly greater extent than male teachers (d = .49). Furthermore, the present study revealed that younger and less experienced teachers, having between 0 and 10 years of experience, perceived national assessment as a tool for control and ranking of schools to a greater extent than experienced teachers (d = .45). As far as we know, there is no previous research providing possible reasons for this. Nevertheless, negative consequences arising from competitive dynamics between schools and their adverse effects on various aspects of teaching and learning were already discovered in the 1990s (e.g., Gordon & Reese, Citation1997). In general, there seems to be a conflict between the need for accountability and control on the one hand, and the desire for responsibility and autonomy on the other in Norwegian school policy. Such tension may lead to diverse outcomes, depending on the approach taken by local school leaders and educators (Elstad, Citation2009). Thus, teachers’ perceptions of control as an impeding external factor in the present study can be related to the conditions under which accountability testing is implemented (Hopfenbeck et al., Citation2015). On a basic psychological level, perceived autonomy and control is linked to the extent to which teachers feel their actions as based on an internal locus of control (i.e., being the origin of one's actions) versus an external locus of control (i.e., being externally controlled; DeCharms & Muir, Citation1978). Pioneering research carried out in the New York school district demonstrated that externally controlled teachers within a performance-oriented context are inclined to becoming drill agents with underachieving students. By contrast, teachers working within an autonomy-supportive learning climate, have high achieving and motivated students (e.g., deCharms, Citation1977; Reeve et al., Citation2004).

The results showed that teachers in the present study perceived spending a significant amount of time preparing (M = 4.47) and evaluating (M = 4.67) national tests. However, the teachers did not value the time and effort invested in the preparation and evaluation of national tests (M = 3.56). This finding deviated from the interviewed male teacher (teacher 2) who showed both enthusiasm and motivation towards engaging in post-test work based on group-level statistics. The female teacher (Teacher 1) found it challenging to comprehend and use the results for pedagogical purposes (Soløst, Citation2023). To the best of our knowledge, prior studies in Norway have not investigated the degree to which schools undertake activities related to preparing and evaluating national assessments. However, Sun et al. (Citation2016) found that teachers have low efficacy in applying student data to address important weaknesses effectively. Seland et al. (Citation2015) highlights a notable difference between the eagerness of school leaders and teachers (who appear less motivated) to use test results for formative purposes. Thus, there seems to be a discrepancy between the national educational goals, which emphasize the importance of analysing test results both collectively and individually (Utdanningsdirektoratet in 2022), and how teachers perceive and engage with this aspect of their work (Mausethagen et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, Norwegian schools do not face the same punitive consequences as the ones reported in several high-stakes testing environments in the U.S. and Latin America (Camphuijsen & Parcerisa, Citation2023; Jones & Egley, Citation2004; Wiliam, Citation2010). Even so, both parents and teachers in Norway perceive ongoing low-stakes accountability testing as controlling and lacking in trust (Camphuijsen & Parcerisa, Citation2023; Skedsmo & Camphuijsen, 2022). Thus, we recognize that it is challenging to identify motivational strategies that may assist educators and school administrators in using test data for formative educational purposes. However, if teachers are provided trust and autonomy (rather than external demands) to take the lead in such a process, they may become motivated based on their own identification of advantages related to formative evaluation (Deci et al., Citation1999; Hopfenbeck et al., Citation2015; Reeve et al., Citation2004).

Finally, teachers reported that national assessment to a certain degree affect the teaching and learning in grades 1–4 (M = 3.86). The teachers also tend to view the educational environment for young children as predominantly theoretical and thus lacking in playfulness. This perception was attributed to the extensive preparations involved in teaching (M = 4.36). This observation may suggest that the curriculum and activities implemented in the years preceding national testing are potentially designed to prepare children for assessment (Soløst, Citation2023). Previous studies have accordingly identified a tendency towards theory-driven methods in primary school (Arviv Elyashiv & Avidov-Ungar, Citation2023; Mausethagen & Mølstad, Citation2015). On the other hand, an increased emphasis on discovery-learning in primary school has been observed as a consequence of eliminating high stakes-test regimens (Collins et al., Citation2010). In conclusion, the qualitative findings indicated a decreased emphasis on accountability and stakes related to national testing in some primary schools. However, this may vary greatly based on the relevant school district. After 20 years with national curriculum testing in Norway, testing seems to be losing its importance at different levels of authority (Olsen & Björnsson). This decline is observed in light of a recommendation made in the United Kingdom over 10 years ago (Stobart, Citation2009; Wyse & Torrance, Citation2009). Currently, the Norwegian Ministry of Education is considering a shift towards a broader application of formative assessment methods, along with occasional national tests (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2023).

Limitations

The present study is subject to several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the sample size consisted of only 117 participants, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to a larger population (Fink, Citation2019). The use of convenience sampling further restricts the representativeness of the sample, as it introduces the possibility of selection bias and limits the external validity of the study (Rubin & Babbie, Citation2016). Additionally, relying solely on survey responses can be subject to response bias, as participants may provide socially desirable or incomplete answers (DeVellis & Thorpe, Citation2021). The qualitative semi-structured interviews conducted in this study also have certain limitations. The primary limitation is the small number of informants, as only two individuals were interviewed. This limited sample size may restrict the breadth and depth of insights obtained from the interviews (Patton, Citation2014). Additionally, the use of semi-structured interviews allows for flexibility but may also introduce interviewer bias, as the interviewer's interpretations and probing techniques can influence the data collected (Brinkmann & Kvale, Citation2018). Furthermore, the transferability of the findings may be limited due to the contextual specificity of qualitative research (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). Acknowledging these limitations is important in order to interpret the study findings within their proper context and to inform future educational research.

Conclusion

The present study has shed light on teachers’ perceptions of mandatory assessment of school children in primary education in Norway. The findings indicate that teachers generally perceive national tests as a valuable source of information, though not necessarily providing new or surprising insights into students’ abilities. It appears that teachers perceive the content of national tests to be somewhat disconnected from other pedagogical tasks that they may deem more significant in their teaching practice. This may explain the lack of motivation and persistence among teachers when it comes to engaging with and acting upon specific test results (Mausethagen, Citation2013; Seland et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, the study revealed notable gender differences in the teachers’ perceptions of national testing. Male teachers viewed testing as significantly more important for the students’ learning and exhibit greater enthusiasm and motivation towards engaging in post-test assessment work. On the other hand, female teachers expressed more scepticism concerning the impact of emphasizing test results and perceiving national assessment as a controlling measure. This was also the case among young teachers with less than 10 years of teaching experience. These differences highlight the need for understanding how teachers’ perceptions and attitudes towards national testing are influenced by work experience and gender-related personality factors (e.g., Lippa, Citation2010). The study emphasizes that national testing should not be used solely as a means to exerting control and ranking schools. Teachers’ concerns about competitive dynamics between schools and the adverse effects on teaching and learning should be addressed (Hargreaves, Citation2020; Shepard et al., Citation2018). There is a need to foster a balanced approach that considers the overall well-being of students, avoiding excessive emphasis on test results (Högberg et al., Citation2021).

In terms of future directions, the study suggests the adoption of a more extensive use of formative assessment approaches supplemented by sampled national tests (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2023). This approach aligns with recommendations made in other countries and aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of students’ progress while reducing the external pressure and expectations associated with accountability-based testing (Shepard et al., Citation2018; Stobart, Citation2009; Wyse & Torrance, Citation2009). Future research should explore the effectiveness and implementation of such an approach within the Norwegian context. In conclusion, this study contributes to the pedagogical discourse of national testing in primary schools. It highlights the importance of considering teachers’ perceptions, gender differences, work experience, regional variations, and the overall impact on teaching and learning (e.g., mastery-orientation vs. performance/results-orientation). By addressing these implications and exploring alternative assessment approaches, policymakers and educators may work towards creating a more balanced and effective assessment system that supports student learning and well-being.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Amrein, A. L., & Berliner, D. C. (2002). High-stakes testing, uncertainty, and student learning. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 10, 18. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v10n18.2002

- Arviv Elyashiv, R., & Avidov-Ungar, O. (2023). Teachers’ perceptions of national large-scale assessment: The pedagogical dimension. Educational Review, 31(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2023.2256996

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2018). Doing interviews (Vol. 2). Sage.

- Camphuijsen, M. K., & Parcerisa, L. (2023). Teachers’ beliefs about standardised testing and test-based accountability: Comparing the perceptions and experiences of teachers in Chile and Norway. European Journal of Education, 58(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12540

- Chen, J., & Teo, T. (2020). Chinese school teachers’ conceptions of high-stakes and low-stakes assessments: An invariance analysis. Educational Studies, 46(4), 458–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2019.1599823

- Chudowsky, N., & Pellegrino, J. W. (2003). Large-scale assessments that support learning: What will it take? Theory Into Practice, 42(1), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4201_10

- Clarke, M., Shore, A., Rhoades, K., Abrams, L., Miao, J., & Li, J. (2003). Perceived effects of state-mandated testing programs on teaching and learning: Findings from interviews with educators in low-, medium-, and high-stakes states. Lynch School Faculty Publications.

- Collins, S., Reiss, M., & Stobart, G. (2010). What happens when high-stakes testing stops? Teachers' perceptions of the impact of compulsory national testing in science of 11-year-olds in England and its abolition in Wales. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 17(3), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2010.496205

- Creswell. (2015). A concise introduction to mixed methods research (1.utgave). SAGE Publications.

- deCharms, R. (1977). Pawn or origin? Enhancing motivation in disaffected youth. Educational Leadership, 34(6), 444–448.

- DeCharms, R., & Muir, M. S. (1978). Motivation: Social approaches. Annual Review of Psychology, 29(1), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.29.020178.000515

- Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological bulletin, 125(6), 627–700. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications. Publisher description http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0658/93036736-d.html

- DeVellis, R. F., & Thorpe, C. T. (2021). Scale development: Theory and applications. Sage publications.

- Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press.

- Eakin, H., Eriksen, S., Eikeland, P. O., & Oyen, C. (2011). Public sector reform and governance for adaptation: Implications of new public management for adaptive capacity in Mexico and Norway. Environmental Management, 47(3), 338–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-010-9605-0

- Elstad, E. (2009). Schools which are named, shamed and blamed by the media: School accountability in Norway. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-009-9076-0

- Elstad, E., Turmo, A., & Nortvedt, G. A. (2009). The Norwegian assessment system: An accountability perspective. The Norwegian Assessment System, 21(2), 1000–1015.

- Fink, A. (2019). Conducting research literature reviews: From the internet to paper. Sage publications.

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Polity.

- Gordon, S. P., & Reese, M. (1997). High-stakes testing: Worth the price? Journal of School Leadership, 7(4), 345–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268469700700402

- Gunn, J., Al-Bataineh, A., & Al-Rub, M. A. (2016). Teachers? Perceptions of high-stakes testing. International Journal of Teaching and Education, 4(2), 49–62.

- Gunnulfsen, A. E. (2017). School leaders’ and teachers’ work with national test results: Lost in translation? Journal of Educational Change, 18(4), 495–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-017-9307-y

- Gunnulfsen, A. E., & Roe, A. (2018). Investigating teachers’ and school principals’ enactments of national testing policies: A Norwegian study. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(3), 332–349. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-04-2017-0035

- Hall, D., Grimaldi, E., Gunter, H. M., Moller, J., Serpieri, R., & Skedsmo, G. (2015). Educational reform and modernisation in Europe: The role of national contexts in mediating the new public management. European Educational Research Journal, 14(6), 487–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904115615357

- Hargreaves, A. (2020). Large-scale assessments and their effects: The case of mid-stakes tests in Ontario. Journal of Educational Change, 21(3), 393–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-020-09380-5

- Harris, D. N., & Herrington, C. D. (2006). Accountability, standards, and the growing achievement gap: Lessons from the past half-century. American Journal of Education, 112(2), 209–238. https://doi.org/10.1086/498995

- Heilig, J. V., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2008). Accountability Texas-style: The progress and learning of urban minority students in a high-stakes testing context. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 30(2), 75–110. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373708317689

- Högberg, B., Lindgren, J., Johansson, K., Strandh, M., & Petersen, S. (2021). Consequences of school grading systems on adolescent health: Evidence from a Swedish school reform. Journal of Education Policy, 36(1), 84–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1686540

- Hood, C., & Dixon, R. (2016). Not what it said on the tin? Reflections on three decades of UK public management reform. Financial Accountability & Management, 32(4), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12095

- Hopfenbeck, T. N., Flórez Petour, M. T., & Tolo, A. (2015). Balancing tensions in educational policy reforms: Large-scale implementation of assessment for learning in Norway. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(1), 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.996524

- Jensen, F., Frønes, T. S., Kjærnsli, M., & Roe, A.. (2020). Lesing i PISA 2000-2018: Norske elevers lesekompetanse i et internasjonalt perspektiv. I T. S. Frønes & F. Jensen (red.), Like muligheter til god leseforståelse? 20 år med lesing i PISA, kapittel 2, s. 21–45. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Jerrim, J. (2021). National tests and the wellbeing of primary school pupils: New evidence from the UK. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 28(5-6), 507–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2021.1929829

- Jones, B. D., & Egley, R. J. (2004). Voices from the frontlines: Teachers’ perceptions of high-stakes testing. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 12(39), n39. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v12n39.2004

- Kher-Durlabhji, N., & Lacina-Gifford, L. J. (1992Quest for test success: Preservice teachers' views of high stakes tests. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Mid-South Educational Research Association, Knoxville, TN. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 353 338).

- Klieger, A. (2016). Principals and teachers: Different perceptions of large-scale assessment. International Journal of Educational Research, 75, 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2015.11.006

- Klinger, D. A., & Rogers, W. T. (2011). Teachers’ perceptions of large-scale assessment programs within low-stakes accountability frameworks. International Journal of Testing, 11(2), 122–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/15305058.2011.552748

- Kvale, S. (2007). Doing interviews. SAGE. http://SRMO.sagepub.com/view/doing-interviews/SAGE.xml

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2021). Det kvalitative forskningsintervju (3. utg.). Gyldendal akademisk.

- Lee, J., & Kang, C. (2019). A litmus test of school accountability policy effects in Korea: Cross-validating high-stakes test results for academic excellence and equity. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 39(4), 517–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2019.1598851

- Leggett, E. L. C. S. D. (1988). A social cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256-273–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Lippa, R. A. (2010). Gender differences in personality and interests: When, where, and why? Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(11), 1098–1110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00320.x

- Marshall, G. (2005). The purpose, design and administration of a questionnaire for data collection. Radiography, 11(2), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2004.09.002

- Mausethagen, S. (2013). Accountable for what and to whom? Changing representations and new legitimation discourses among teachers under increased external control. Journal of Educational Change, 14(4), 423–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-013-9212-y

- Mausethagen, S., & Mølstad, C. E. (2015). Shifts in curriculum control: Contesting ideas of teacher autonomy. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 2015(2), 28520. https://doi.org/10.3402/nstep.v1.28520

- Mausethagen, S., Prøitz, T., & Skedsmo, G. (2018). Teachers’ use of knowledge sources in ‘result meetings’: Thin data and thick data use. Teachers and Teaching, 24(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2017.1379986

- Mausethagen, S., Prøitz, T. S., & Skedsmo, G. (2019). School leadership in data use practices: Collegial and consensus-oriented. Educational Research, 61(1), 70–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2018.1561201

- McDonald, N., Schoenebeck, S., & Forte, A. (2019). Reliability and inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: Norms and guidelines for CSCW and HCI practice. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), 1–23.

- Østerud, S. (2016). Hva kan norsk skole lære av PISA-vinneren Finland? Nordisk tidsskrift for pedagogikk og kritikk, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.17585/ntpk.v2.119

- Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage publications.

- Prøitz, T. S., Mausethagen, S., & Skedsmo, G. (2021). District administrators’ governing styles in the enactment of data-use practices. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 24(2), 244–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1562097

- Ramnefjell, E. (2001, Desember 5). Norge er en skoletaper. Dagbladet. https://www.dagbladet.no/nyheter/norge-er-skoletaper/65772609

- Reese, M., Gordon, S. P., & Price, L. R. (2004). Teachers’ perceptions of high-stakes testing. Journal of School Leadership, 14(5), 464–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268460401400501

- Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., & Barch, J. (2004). Enhancing students´ engagement by increasing teachers’ autonomy support. Motivationn and Emotion, 28(2), 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MOEM.0000032312.95499.6f

- Rubin, A., & Babbie, E. R. (2016). Empowerment series: Research methods for social work. Cengage Learning.

- Seland, I., Hovdhaugen, E., & Vibe, N. (2015). Mellom resultatstyring og profesjonsverdier. Nordisk Administrativt Tidsskrift, 92(3), 44–59.

- Shepard, L. A., Penuel, W. R., & Pellegrino, J. W. (2018). Classroom assessment principles to support learning and avoid the harms of testing. Educational Measurement, Issues and Practice, 37(1), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12195

- Sjøberg, S. (2014). PISA-syndromet – hvordan norsk skolepolitikk blir styrt av OECD. Nytt Norsk Tidsskrift, 31(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1504-3053-2014-01-04

- Sjøberg, S. (2022). Nasjonale prøver. I Store norske leksikon. https://snl.no/nasjonale_pr%C3%B8ver

- Skedsmo, G., & Camphuijsen, M. K. (2010). The battle for whole-child approaches: Examining the motivations, strategies and successes of a parents’ resistance movement against a performance regime in a local Norwegian school system. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 30, 136. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.30.6452

- Smith, M. S., & O’Day, J. (1990). Systemic school reform. Journal of Education Policy, 5(5), 233–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939008549074

- Soløst, T. (2023). Hva mener lærere om betydningen av nasjonale prøver i grunnskolen? (Master’s thesis, Inland Norway University).

- Spruyt, B., Van Droogenbroeck, F., Van Den Borre, L., Emery, L., Keppens, G., & Siongers, J. (2021). Teachers’ perceived societal appreciation: PISA outcomes predict whether teachers feel valued in society. International Journal of Educational Research, 109, 101833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101833

- St. meld. nr. 30. (2003-2004). Kultur for læring. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-030-2003-2004-/id404433/?ch = 1:Regjeringen.no

- Stobart, G. (2009). Determining validity in national curriculum assessments. Educational Research, 51(2), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880902891305

- Sun, J., Przybylski, R., & Johnson, B. J. (2016). A review of research on teachers’ use of student data: From the perspective of school leadership. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 28(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-016-9238-9

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, G. R. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (Vol. 6). Pearson Education.

- Thompson, G., & Harbaugh, A. G. (2013). A preliminary analysis of teacher perceptions of the effects of NAPLAN on pedagogy and curriculum. The Australian Educational Researcher, 40(3), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-013-0093-0

- Thuen, H. (2017). Den Norske Skolen: Utdanningssystemets historie. Abstract forlag.

- Tobin, M., Nugroho, D., & Lietz, P. (2016). Large-scale assessments of students’ learning and education policy: Synthesising evidence across world regions. Research Papers in Education, 31(5), 578–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1225353

- Upadhyay, B. (2009). Negotiating identity and science teaching in a high-stakes testing environment: An elementary teacher’s perceptions. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 4(3), 569–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-008-9170-5

- Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2020). Overordnet det—Verdier og prinsipper for grunnopplæringen. Utdanningsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/

- Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2022a). Rammeverk for nasjonale prøver. Utdannigsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/eksamen-og-prover/prover/rammeverk-for-nasjonale-prover2/hva-er-nasjonale-prover/

- Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2022b). Nasjonale prøver. Utdannigsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/eksamen-og-prover/prover/nasjonale-prover/

- Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2023). Kartleggingsprøver. Utdanningsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/eksamen-og-prover/prover/kartlegging-gs/

- Wideen, M. F., O’Shea, T., Pye, I., & Ivany, G.. (1997). High-Stakes Testing and the Teaching of Science. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue Canadienne de l’éducation, 22(4), 428–444. https://doi.org/10.2307/1585793

- Wiliam, D. (2010). Standardized testing and school accountability. Educational Psychologist, 45(2), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461521003703060

- Wright, W. E., & Choi, D. (2006). The impact of language and high-stakes testing policies on elementary school English language learners in Arizona. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 14(13), 1–75.

- Wyse, D., & Torrance, H. (2009). The development and consequences of national curriculum assessment for primary education in England. Educational Research, 51(2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880902891479