ABSTRACT

Hybrid teaching, synchronous face-to-face and online learning will continue to be part of flexible teaching methods. This mixed method study aimed to measure the effects of an educational intervention on the development of health sciences and medical educators’ (n = 16) hybrid teaching competence combining experiences about motivation. Hybrid teaching competence was measured with a self-assessment Hybrid Education Competence instrument from one Finnish university in 2022. Pre and post measures about hybrid teaching competence (n = 16) and semi-structured interviews (n = 5) about learning motivation were conducted. Wilcoxon’s signed rank test and inductive content data analysis were used. The educators showed a statistically significant increase in their competence in planning and resourcing hybrid teaching, technological, interaction, digital pedagogy, and ethical competence. Educators experienced the challenges of supporting motivation were less prominent in the second interview than in the first. The study provides evidence on the development of educators’ continuous education and supporting learning motivation.

Introduction

Highly educated, competent healthcare workers must be available to ensure high-quality healthcare. The World Health Organization (WHO) has predicted that by 2035 there will be a shortage of 12.9 million healthcare workers (WHO, Citation2013). Health sciences educators are needed to train future professionals (Mikkonen et al., Citation2019a). WHO (Citation2016), the National League for Nursing (Citation2018) and the Committee for Faculty and Organizational Development in Teaching (Görlitz et al., Citation2015) have identified core competencies for health sciences and medical educators to ensure the highest quality and effectiveness of education.

The professionals of the future will be trained through a range of qualifications and digitalised education. The development of digitalisation in education must be purposeful (Vlies, Citation2020). The digitalisation of education has increased accessibility and flexibility (Lakhal et al., Citation2021). Technology-based teaching is also seen as a factor that sustains and supports learning motivation (Dennis et al., Citation2007). However, these benefits cannot be achieved without educators’ digital competence, which can also support students’ adaptation and self-management in the face of unexpected challenges (Alarcón et al., Citation2020; Sormunen et al., Citation2021). The traditional teaching model of real-time face-to-face teaching in the same physical space has been paralleled by hybrid education; meaning in our study simultaneous face-to-face and online teaching (e.g., Lakhal et al., Citation2021).

Hybrid teaching has been studied recently (Bower et al., Citation2015; Lakhal et al., Citation2021; Raes et al., Citation2020), but only marginally in social and healthcare education. In the context of nursing education, previous studies have shown that face-to-face students typically have a stronger sense of presence than online students (Lafortune & Lakhal, Citation2020). Hybrid education creates additional challenges for the educator regarding teaching methods, for example, in providing attention to different student groups and facilitating interaction in a hybrid format (Raes et al., Citation2020; Suárez-Rodríguez et al., Citation2018). According to Mikkonen et al. (Citation2022), it is important to ensure that the education of social and healthcare educators is sufficiently comprehensive in the implementation of student-centred pedagogy using digital learning environments. As hybrid teaching methods in health sciences education are and will be one of the flexible methods that can be further developed, attention needs to be paid to the development of educators’ hybrid teaching competence and educational interventions to develop them. There is a gap in this kind of educational intervention and the effectiveness of those. This study aims to measure the effects of an educational intervention on the development of health sciences and medical educators’ hybrid teaching competence. The study also aims to better understand educators’ perceptions on learning motivation in hybrid education. The study results can be used to build educators’ competence through continuous education, especially regarding hybrid education.

Background

Health sciences educators’ education aims to initiate the growth of pedagogical expertise and promote growth as a social and healthcare educator based on evidence (Mikkonen et al., Citation2019a). This study focuses on educators working in the health sciences and medical sciences fields. Primarily, health sciences educators work as educators at higher education institutions (including universities or universities of applied sciences) or secondary vocational education, but also in clinical organisations in social and healthcare, e.g., as clinical educators (Kaarlela et al., Citation2022; Mikkonen et al., Citation2019a). Health sciences competence requires educators to have a wide range of different areas of competence on macro and micro levels (Mikkonen et al., Citation2018; Mikkonen et al., Citation2019a). Macro level competencies require competencies in evidence-based practice, sustainable innovation and foresight, and continuous competence development. Micro level competencies require scientific and professional competencies in the field of social, health and rehabilitation sciences, pedagogical competencies, ethical and cultural competencies, interaction, cooperation and networking competencies, as well as management and well-being at work competencies (Mikkonen et al., Citation2019a). The core competencies also consist of subject matter competence (Mikkonen et al., Citation2019b; Salminen et al., Citation2021; WHO, Citation2016), information and communication technology (ICT) competence (Mikkonen et al., Citation2019b) and development and work community competence (Kuivila et al., Citation2020; Mikkonen et al., Citation2019b; WHO, Citation2016). The health sciences educators must also be able to facilitate student learning and motivation through different teaching methods and the achievement of students’ goals (Christensen & Simmons, Citation2019; Kuivila et al., Citation2020). In addition, competencies are thought to include the ability to motivate students (Töytäri et al., Citation2016). Motivation drives the individual to act towards the learning outcome, thus it can be seen as one of the important factors for the achievement of learning (Dennis et al., Citation2007).

The GMA, Committee for Faculty and Organizational Development in Teaching has developed a model of core teaching competencies for medical educators. These competencies are educational action in medicine, learner-centeredness, social and communicative competencies, role modelling and professionalism, reflection and advancement of personal teaching practice and systems-related teaching and learning (Görlitz et al., Citation2015). In medical education, online teaching has become an important component of teaching (Chin et al., Citation2021) to reach effectiveness (Liao et al., Citation2022). To maintain the highest possible standards of clinical teaching, it is important that medical educators also know how to deliver effective online teaching if face-to-face clinical learning is compromised (Dong et al., Citation2021).

Educators in the social and healthcare field are expected to implement and manage a range of new digital teaching technologies (Suárez-Rodríguez et al., Citation2018; WHO, Citation2016). It is important that educators develop their skills to ensure the competence of future experts. Educators have faced new models of flexible teaching, for example, hybrid teaching that combines face-to-face and online teaching (Saichaie, Citation2020). This study defines hybrid teaching as simultaneous face-to-face and online teaching (Lakhal et al., Citation2021; Singh et al., Citation2021). Several different terms are used for this kind of teaching. Ashraf et al. (Citation2021) use the concept of “blended learning”, which combines different forms of teaching. The terms “synchronous blended learning” (Raes et al., Citation2020), “Here or There (HOT) learning” (Zydney et al., Citation2018), “hybrid learning” (Singh et al., Citation2021) and “blended synchronous learning” (Bower et al., Citation2015; Lakhal et al., Citation2021) have also been used. Hybrid education gains new meanings as forms of learning continue to evolve.

Hybrid teaching has been perceived as posing challenges for educators to create teaching and learning methods for two groups of students simultaneously and to integrate them into a coherent whole. Hybrid teaching also requires educators to learn and maintain technological skills (Bower et al., Citation2015; De Gagne, Citation2018; Lakhal et al., Citation2021; Wang & Huang, Citation2018), and the quality of teaching may depend on the educator’s technological skills (Bower et al., Citation2015). Learning and teaching in a hybrid learning environment can increase the mental load for both students and educators (Bower et al., Citation2015). In medical education, prolonged online learning can also undermine professional identity formation by reducing social interaction (Lee et al., Citation2022). In addition, it has been found that motivating and engaging distance learners in student-centred learning and engagement can be challenging and require more resources from the educator (Raes et al., Citation2020). According to several studies, student-centred learning is an approach that supports and sustains student motivation and allows educators to focus more on supporting students in their learning (Raes, Citation2021; Shi et al., Citation2021).

Motivation is the basis for effective learning: students must have the desire to learn in order for learning and studying to take place, especially in hybrid education. This study divided motivation into intrinsic and extrinsic motivation according to Ryan and Deci (Citation2020) to allow for a more in-depth analysis. The theoretical basis was chosen for its compatibility with the hybrid learning context. Motivation is an individual’s desire or state of mind to act for something, this desire is composed of several internal and external factors (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). Learning motivation is not necessarily a given, and often requires external support to be achieved. This support for learning motivation is often seen as a challenge for implementing hybrid education due to reduced social interaction (Ashraf et al., Citation2021; Boling et al., Citation2012). Supporting motivation requires educators to understand how motivation is formed and what factors contribute to its development. According to Ryan and Deci (Citation2020), the psychological needs of the individual are the driving factors behind the emergence of motivation. These needs are the need for autonomy, the need for self-reliance and the need for community. By satisfying and supporting these needs, the individual and his environment can influence and support his motivation (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). However, this is not an easy task because of motivation’s multi-dimensional and personal nature (Shi et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, it is possible to regulate by choosing quality materials, learning environments and the right teaching methods (Bower et al., Citation2015). These skills are required for educators to deliver effective hybrid education and learning.

Students in distance education can find it difficult to communicate and interact with the educator and students in the classroom (Bower et al., Citation2015; De Gagne, Citation2018; Lakhal et al., Citation2021; Wang & Huang, Citation2018). The functionality of technology, which is a prerequisite for smooth interaction in teaching, has also been identified as important (Wang et al., Citation2017). Hybrid teaching will be part of flexible teaching methods and demands competence development among educators (Lakhal et al., Citation2021; Raes et al., Citation2020). Continuous education for educators is essential. After conducting an extensive literature search with the terms “hybrid teaching” AND “health sciences” AND “medical science” in two electronic databases (Cinahl, Pubmed), no research was found on interventional studies relating to the topic. We concluded that information is needed to support educators’ competence in hybrid teaching in higher education, develop appropriate education for educators, support team teaching, and provide tools and new methods for higher education institutions by ensuring quality of education and students’ competence development.

Methods

This study aimed to measure the effects of an educational intervention on the development of health sciences and medical educators’ hybrid teaching competence and to better understand educators’ perceptions of learning motivation in hybrid education.

The research questions were: What are the effects of the educational intervention on health sciences and medical educators’ self-assessed hybrid teaching competence? What are the views of health sciences and medical educators on learning motivation and its role in hybrid learning? What are the views of health sciences and medical educators on students’ motivation to learn in hybrid learning?

The hypothesis was: Hybrid teaching education has a statistically significant (p < 0.05) effect on health sciences and medical educators’ self-assessed hybrid teaching competence when comparing competence before and after education.

Study design

The study was designed as a mixed-method study with pre- and post-measurements (Polit & Beck, Citation2018). Educators participated in the educational intervention and completed a self-assessment measurement before and after the education. The semi-structured interviews were also conducted before and after the educational intervention.

Participants and setting

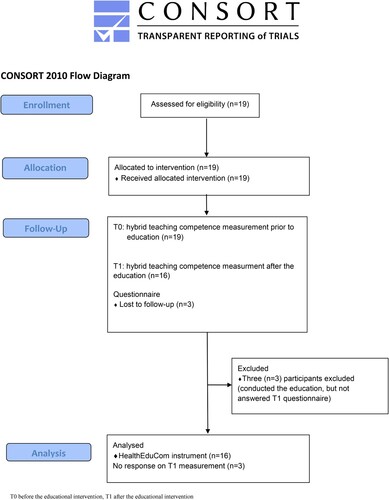

A total of 19 educators participated in the educational intervention and 16 responded to both (pre- and post-) invitations. The participants were educators from one Finnish university of health sciences-related fields (n = 16, mean age 43 years) (see ). The study participants were selected by the commonly used discretionary sampling (Polit & Beck, Citation2018). Five volunteer educators participating in the educational intervention took part in the interviews also before and after the intervention. The inclusion criteria required respondents to be (1) working in a Finnish university in an educational position, teaching health sciences or medical sciences and (2) were willing to participate in the study.

Table 1. Sociodemographic information of participants (n = 19).

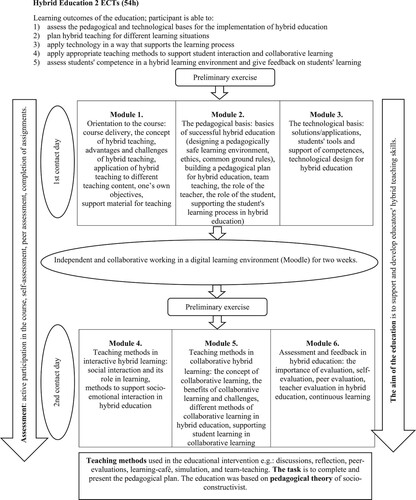

Educational intervention

The educational intervention () consisted of the theoretical framework built on the previous research data (Pramila-Savukoski et al., Citation2022; Pramila-Savukoski et al., Citation2023). Theoretical framework has been designed using the Tidier checklist (Hoffmann et al., Citation2014) and it was divided in six modules. These modules contain: (1) orientation to the course (e.g., introducing the concept of hybrid teaching) (2) the pedagogical premises (e.g., the basics of successful hybrid education and motivation 3) the technological premises (e.g., technological design for hybrid education, different applications) (4) teaching methods in interactive hybrid learning (e.g., social interaction and its role in learning and supporting learning process) (5) teaching methods in collaborative hybrid learning, (e.g., the concept of collaborative learning) and (6) assessment and feedback in hybrid education (e.g., the importance of evaluation). Education was 2 ECTs (54 hours), consisting of two contact days held as hybrid teaching. The education was based on a socio-constructivist perspective (Vygotsky, Citation1978) and included different teaching methods such as short lectures, videos, case studies, presentations, simulations, peer assessments, discussions, and collaborative learning tasks. The education aimed to enable the educator to understand the principles of hybrid teaching, plan hybrid teaching for different learning situations, assess the use of appropriate methods, develop student-educator interaction, and use team teaching methods. The aim was also to assess the suitability of different teaching methods for different subjects and different group sizes. Two educators implemented the education, one teaching in the classroom and one acting as a virtual educator.

Instrument

The Hybrid Education Competence (HybridEduCom) self-assessment instrument (Jokinen et al., Citation2023) was used to measure pre- and post-evaluations of participants’ hybrid education competence. The instrument included five sum-variables with 46 items, including: (1) Competence in planning and resourcing hybrid teaching (10 items, Cronbach’s alpha 0.93), (2) Technological competence in hybrid teaching (8 items Cronbach’s alpha 0.94), (3) Interaction competence in hybrid teaching (10 items, Cronbach’s alpha 0.94), (4) Digital pedagogy competence in hybrid teaching (12 items, Cronbach’s alpha 0.95) and (5) Ethical competence in hybrid teaching (6 items, Cronbach’s alpha 0.90) (Jokinen et al., Citation2023). Self-assessment was made with a five-level Likert scale (1-poor; 2-moderate; 3-good; 4-very good; 5-excellent). In addition, we also asked nine background questions (see ).

Data collection

The study’s CONSORT flow diagram demonstrates the study process’s flow (Schulz et al., Citation2010) (). Data was collected through a Webropol Survey & Reporting-online survey during and through telephone interviews the autumn 2022, before and after the educational intervention. Educators who participated in the educational intervention were invited to the study with a separate invitation via e-mail. The invitations provided information about the study’s aims, the method of data collection, and its ethical aspects. In addition, the invitation included a privacy statement, which explained the participation in the study and the privacy policy (Polit & Beck, Citation2018). Before and after the educational intervention, participants were asked to respond to nine background questions and 46 items of the HybridEduCom instrument. Also, they were asked to respond to a question about their attitude towards hybrid teaching (on a scale of 1–10). Additionally, using a separate poll, five questions were given in the post-test about the educator’s satisfaction with the instructions for the educational intervention; the contents; tasks and activities; how they feel they can utilise the information from the educational intervention; and how the organisers managed in technological design. A separate poll was made with a five-level Likert scale (1- very poor; 2-poor; 3-fair; 4-good; 5-very good). The educators were also asked to give feedback on the educational intervention by means of open-ended questions. The interview questions were related to educators’ perceptions of motivation and its support in hybrid education, including their satisfaction with the intervention. The interviews were conducted as semi-structured individual interviews via telephone. Questions included: In your opinion, what is motivation? What is the role of motivation in hybrid education? What are the different ways to support motivation in hybrid education? Learning motivation in hybrid education is a relatively new phenomenon for which no suitable instrument exists. For this reason, it was decided to complement the quantitative questionnaire about hybrid learning competence with qualitative data. The advantage of triangulation is that it allows us to approach a topic from more than one perspective and, thus, increase the reliability and validity of the research.

Data analysis

IBM SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) was used for data analysis. The sociodemographic background data were described using descriptive statistics, percentages, and frequencies. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine differences in educators’ hybrid teaching competence before and after the educational intervention. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The satisfaction-post-poll data was analysed using descriptive statistics frequencies, mean, median and standard deviation. The interviews were analysed using inductive content analysis. The data were used to form 20 subcategories. These subcategories were divided into seven main categories according to their content. These main categories were: external motivation, intrinsic motivation, distance learning and motivation, hybrid learning and motivation, learning environments, learning materials and methods, and social interaction. The main categories were used to form significant data clusters that answered the research questions. The analysis followed the framework for data analysis set by Miles and Huberman (Citation1994).

Ethical considerations

Good research ethics were followed at all stages of the study (Declaration of Helsinki, Citation2013). The study did not require ethical approval, because all the participants were over 18 years of age, and no sensitive data were collected (Medical Research Act 488/1999, Citation1999). A research permit was obtained from the university. Throughout the process, the data were stored in line with GPDR (European Parliament, Citation2016). The data was anonymised by adding codes to all participants. Before gathering informed consent, participants were informed of the study’s aim, their right to withdraw from the study at any time, using data and that participation was voluntary (European Parliament, Citation2016.).

Results

Participants

Participants’ mean age was 43 years. They were mostly female (94.7%), with an educational level of master’s degree (57.9%) or doctor’s degree (42.1%). Their current job titles were university lecturer, university teacher, clinical teacher, researcher (doctoral researcher, postdoc researcher) or medical teacher, and they taught in different university disciplines, such as health sciences, medicine, dentistry, or biochemistry. The mean score for work experience in years in the social and healthcare sector was 14 years. Participants had an average of 8 years of work experience in a teaching role. Most participants (68.4%) had no pedagogical qualification, but 36.8% had completed teacher’s pedagogical studies. One-tenth (10.5%) of participants had vocational teacher education and one-fifth (21.1%) had health science teacher education (see ).

Effects of the educational intervention on educator’s hybrid education competence

According to the measurements (see ), the educators reported that the educational intervention significantly improved their competence in planning and resourcing hybrid teaching (p < 0.001; pre-test mean = 2.23 (SD = 0.71) vs. post-test mean = 3.27 (SD = 0.63)), in technological competence in hybrid teaching (p < 0.001; pre-test mean = 2.25 (SD = 0.69) vs. post-test mean = 3.17 (SD = 0.62)), in interaction competence in hybrid teaching (p = 0.003, pre-test mean = 2.37 (SD = 0.84) vs. post-test mean = 3.21 (SD = 0.76)), in digital pedagogy competence in hybrid teaching (p = 0.002; pre-test mean = 2.13 (SD = 0.77) vs. post-test mean = 2.98 (SD = 0.78)), and in ethical competence in hybrid teaching (p = 0.003; pre-test mean = 2.28 (SD = 0.74) vs. post-test mean = 3.07 (SD = 0.67)). The educators reported that their attitude (on a scale of 1–10) towards hybrid education did not change significantly after the educational intervention (p = 0.156; pre-test mean = 7.05 (SD = 2.36) vs. post-test mean = 8.25 (SD = 1.00))

Table 2. Results of educational hybrid learning intervention (n = 16).

Educators’ satisfaction with the educational intervention

Participants (n = 15) reported that the education instructions supported their learning (mean = 4.25, median = 4.00 SD = 0.57, min = 3, max = 5). The module topics (pedagogical and technological competence, interaction, collaborative learning, evaluation, and feedback) were perceived as good (mean = 4.19, median = 4.00, SD = 0.65, min = 3, max = 5). The educators also felt that the learning tasks and activities supported their learning (mean = 3.81, median = 4.00, SD = 0.75, min = 2, max = 5). They felt that they could utilise well or really well their learning in working life (mean = 4.25, median = 4.00, SD = 0.68, min = 3, max = 5). They felt also that the technological implementation of education was successful (mean = 4.31, median = 4.00, SD = 0.70, min = 3, max = 5). In the open-ended question, they reported that education responded to their needs and was designed meaningfully. They also felt that the education increased their knowledge of hybrid teaching, which will encourage them to implement it.

Educators’ perceptions of motivation in hybrid education

Based on the educators’ responses, categories were formed to form significant entities that answered the research questions (see ). These entities were: Definition of motivation, The importance of motivation, Supporting motivation. In general, the interviews revealed that educators had a somewhat narrow perception of motivation to learn. They roughly divided motivation into intrinsic motivation and external motivation, and no other ways of describing motivation emerged in the interviews. In several situations, intrinsic motivation and external motivation were seen as mutually exclusive, with intrinsic motivation being seen as more important for learning. These categories formed the educators’ definition of motivation. Learning motivation was seen as a necessary factor in the learning process, which a variety of external support could influence. Educators saw the importance of motivation for teaching as varying between different teaching methods, for example, they considered the role of motivation to be greater in distance learning than in hybrid learning. The category distance learning and motivation and hybrid learning, and motivation formed educators’ understanding of the importance of motivation. According to the educators, learning materials and methods were the biggest factors supporting students’ motivation in hybrid teaching. High-quality learning materials were seen as motivating factors that could influence the whole learning process. Activating students through teaching methods was also seen as an important factor in the learning process, to which educators should pay attention in their teaching. The role of social interaction was also seen as a major factor in supporting students’ motivation in hybrid teaching. Great emphasis was also placed on a sense of community through interaction. The learning environment was also seen as a factor influencing student motivation and its support. Based on these descriptions, a framework for supporting motivation was formed. Overall, there was little difference in the content of the responses to the first and second interviews, the same influencing factors were raised in both interviews. The second round of interviews generally produced fewer responses than the first (see ). However, fewer challenges and issues in hybrid education were identified in the second round of interviews. Educators found the intervention’s content useful, and all interviewed educators felt that they had learned something new about hybrid teaching and motivation support during the intervention.

Table 3. Classification of interview results into subcategories and main categories, and their occurrence in the data (First/second interview).

Discussion

This study aimed to measure the effects of an educational intervention on the development of health sciences and medical educators’ hybrid teaching competence. This study indicated that participation in educational intervention increases health sciences and medical educators’ self-evaluation of hybrid teaching competence. The results of pre and post measurements of the present study show statistically significant improvements in each hybrid teaching competence area. Other studies have also found that continuing education has a strong role in educators’ professional development (e.g., Koskimäki et al., Citation2021). The hybrid education provided in this study was evidence-based and the educational intervention consisted of the theoretical framework built on the previous research data (Pramila-Savukoski et al., Citation2022; Pramila-Savukoski et al., Citation2023).

Following the hybrid education, participants reported good competence in hybrid teaching in all areas. However, the results still confirm the need to support educators’ hybrid teaching competencies. It is needed for extensive, high-quality professional development that is planned, and meaningful and should be supported by the organisation (Koskimäki et al., Citation2021). Significant changes were found particularly in planning and resourcing hybrid teaching and technological competence in hybrid teaching. In hybrid education, learning and maintaining technological competencies has been described in earlier studies as a challenge. Hybrid teaching has been perceived as posing challenges for educators to create teaching and learning methods for two groups of students at the same time and to integrate them into a coherent whole (Bower et al., Citation2015; De Gagne, Citation2018; Lakhal et al., Citation2021; Wang & Huang, Citation2018). It has also been found that the quality of teaching can depend on the technological competence of the educator (Bower et al., Citation2015). However, using different technological solutions in teaching has been found to enable alternative learning approaches through cleverly designed content, which can enrich the learning content visually and attract students to learn more broadly and deeply (Sormunen et al., Citation2021).

Previous studies have found that predicting interaction and collaboration between distance and face-to-face learners may also require planning from the educator (e.g., Lakhal et al., Citation2021). Health sciences and medical educators’ competence in interaction in hybrid teaching increased after educational intervention. Interaction and collaboration in a hybrid learning environment do not necessarily occur spontaneously and therefore require planning (Bower et al., Citation2015). It has been recognised in the previous study (Oprescu et al., Citation2017), that nursing educators may have among others poor motivation, poor communication skills or dysfunctional team communication with students. However, it is primarily important that the learning environment is interactive and participatory (Lakhal et al., Citation2021), because to succeed and make progress in their studies, students need interpersonal skills that promote their ability to communicate and interact effectively with each other (Sormunen et al., Citation2021). In the interviews, the educators highlighted the role of social interaction in supporting motivation in hybrid education. Also, prior studies have highlighted that social interaction between students maintains and develops students’ motivation to learn (Raes, Citation2021). The educators perceived activating teaching methods as a means of encouraging social interaction between learners and allowing more interactive teaching. This has been pointed out also in previous studies as an influencing factor, especially in hybrid education (Boling et al., Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2017).

In this study health sciences and medical educators’ competence in digital pedagogy in hybrid teaching, was the weakest of all areas before the educational intervention, and this has been shown in previous studies also, although educators are relatively interested in using digital technology in teaching (e.g., Ryhtä et al., Citation2021). However, competence increased significantly after the educational intervention. Previous studies have recognised that hybrid teaching creates additional challenges for the educator regarding teaching methods and paying attention to different student groups and interactions (Raes et al., Citation2020; Suárez-Rodríguez et al., Citation2018). Educators must also be able to facilitate student learning through different teaching methods and the achievement of student goals (Christensen & Simmons, Citation2019; Kuivila et al., Citation2020), so it is important that they have a good level of competence in digital pedagogy. Providing a continuous education can increase educators’ digital pedagogical competencies and thus provide quality teaching to students (Ryhtä et al., Citation2021). In hybrid teaching, the role of the students and the guidance of their activities is emphasised, while interaction is reduced (Shi et al., Citation2021).

The developed and evaluated hybrid education was proven to be effective in health sciences and medical educators’ competence in hybrid teaching. Feedback from educators also indicated that the education was satisfying for the educators’ needs, meaningful and enhanced their own hybrid teaching competence which again encouraged them to implement hybrid teaching. This aligns well with previous studies (e.g., Oprescu et al., Citation2017), which have recognised that educators think favourably about professional development and that they benefit from continuous digital pedagogy education (Ryhtä et al., Citation2021). Our results were statistically insignificant when comparing attitudes towards hybrid education before and after the education, which can be explained by educators’ highly positive attitudes towards hybrid education from the beginning. However, after the education, the attitudes towards hybrid education had changed in a more positive direction. The interviews also show a change in educators’ attitudes, and the descriptions of the challenges in hybrid teaching were less prominent in the second interview than in the first. In the future, when developing hybrid teaching competencies, it might also be good to consider attitudes, as attitudes also determine motivation (Ferrer et al., Citation2022). Evidence-based hybrid teaching education also seems to support competence development, which can, in turn, also support students’ adaptation and self-management in the face of unexpected challenges (Alarcón et al., Citation2020; Sormunen et al., Citation2021). Overall, in both interviews, educators described hybrid teaching and motivation as part of it in similar terms. However, how educators described support for motivation increased in the second interview. Hybrid teaching will be part of flexible teaching methods and demands competence development among educators in the future (Chin et al., Citation2021; Lakhal et al., Citation2021; Raes et al., Citation2020), to ensure quality education and the development of students’ competencies. Social and healthcare educators’ macro level competencies and continuous learning have important effects on the education and development of future professionals (Mikkonen et al., Citation2019b). Therefore, designing educational interventions that develop educators’ hybrid teaching competence is meaningful. However, planning of educators` learning should be a continuous, systematic process from the time of studies until a professional career (Koskimäki et al., Citation2022). Team teaching was utilised in our intervention, and that may have affected self-evaluations because resources were good. Organisations should consider team teaching or mentoring to reduce educators´ workload.

Limitations and strengths

There are a few limitations to this study. First, a small number of subjects, and second, the study was conducted in one Finnish university, so the presented results should be generalised with caution. Third, participants knew they would participate in the study, which may have influenced their assessment of their hybrid teaching competence. Fourthly, randomisation, participant blinding, or a control group were not used in this study, which affects the study’s internal validity. Still, this kind of educational intervention will provide promising results for continuous education and provide a new educational framework to improve hybrid education in health and medical sciences. The study’s strength is that health sciences and medical educators’ competence was assessed using the HybridEduCom instrument, which previously demonstrated acceptable content, construct validity, and sufficient internal consistency (Jokinen et al., Citation2023). Including a control group would have strengthened study’s validity (Des Jarlais et al., Citation2004). The TREND statement (Des Jarlais et al., Citation2004) and The TIDieR checklist (Hoffmann et al., Citation2014) were used to ensure the validity and when creating the educational intervention.

Conclusion

This study shows that the educational intervention significantly improved health sciences and medical educators’ competence in hybrid teaching. The results of this study can be used to develop hybrid education that will serve as continuing education for educators. However, more research is needed to evaluate hybrid teaching competence in different contexts and assess various innovative methods for providing hybrid education. In addition, educators need to be encouraged to participate in hybrid education and receive support to develop their hybrid competencies. For the development of hybrid teaching, it would also be important to pay attention to how educators perceive the learning process and how they can support motivation regulation. Organisations should enable every educator to participate in continuous education for hybrid teaching competencies and this theme should be considered in educators’ pedagogical studies. Future in this area could focus on retesting the educational intervention with a larger sample or in international contexts, integrating artificial intelligence solutions by including for example simulation or innovative methods like extended reality.

Ethics approval

The Dean of the University of Oulu provided a statement (11.1.2022) that the planned research was ethically acceptable. Ethical statement of ethical committee was not required according to Finnish data protraction act: https://www.oulu.fi/en/university/faculties-and-units/eudaimonia-institute/ethics-committee-human-sciences.

Author contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; MK, SPS, JO, HMK, KM

Drafting the work or reviewing it critically for important intellectual content; MK, SPS, JO, HMK, JJ, TT, KM

Final approval of the version to be published; MK, SPS, JO, HMK, JJ, TT, KM

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.: MK, SPS, JO, HMK, JJ, TT, KM

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of The University of Oulu & The Academy of Finland Profi 7 352788 for supporting this study. We appreciate all the health sciences and medical educators for their time and participating in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions to the privacy of the participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Alarcón, R., Pilar Jiménez, E., & Vicente-Yagüe, M. I. (2020). Development and validation of the DIGIGLO, a tool for assessing the digital competence of educators. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(6), 2407–2421. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12919

- Ashraf, M. A., Mollah, S., Perveen, S., Shabnam, N., & Nahar, L. (2021). Pedagogical applications, prospects, and challenges of blended learning in Chinese higher education: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 772322. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.772322

- Boling, E., Hough, M., Krinsky, H., Saleem, H., & Stevens, M. (2012). Cutting the distance in distance education: Perspectives on what promotes positive, online learning experiences. The Internet and Higher Education, 118–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.11.006

- Bower, M., Dalgarno, B., Kennedy, G. E., Lee, M. J. W., & Kenney, J. (2015). Design and implementation factors in blended synchronous learning environments: Outcomes from a cross-case analysis. Computers & Education, 86, 1–17. https://doi-org.pc124152.oulu.fi:9443/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.03.006

- Chin, K. E., Kwon, D., Gan, Q., Ramalingam, P. X., Wistuba, I. I., Prieto, V. G., & Aung, P. P. (2021). Transition from a standard to a hybrid on-site and remote anatomic pathology training model during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 145(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2020-0467-SA. .

- Christensen, L., & Simmons, L. E. (2019). The academic clinical nurse educator. Nursing Education Perspectives, 40(3), 196. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000509

- Declaration of Helsinki. (2013). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. Retrieved April 11, 2023, from https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053. .

- De Gagne, J. C. (2018). Teaching in online learning environments. In M. H. Oermann, J. C. De Gagne, & B. C. Phillips (Eds.), Teaching in nursing and role of the educator, the complete guide to best practice in teaching, evaluation, and curriculum development (2nd ed., pp. 95–111). Springer Publishing Company.

- Dennis, K., Bunkowski, L., & Eskey, M. (2007). The little engine that could - How to start the motor? Motivating the Online. InSight: A Collection of Faculty Scholarship, 2, 35–49. https://doi.org/10.46504/02200704de

- Des Jarlais, D. C., Lyles, C., Crepaz, N., & Group, T. (2004). Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. American Journal of Public Health, 94(3), 361–366. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.3.361

- Dong, C., Lee, D. W., & Aw, D. C. (2021). Tips for medical educators on how to conduct effective online teaching in times of social distancing. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare, 30(1), 59–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/2010105820943907

- European Parliament. (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Retrieved April Available 11, 2023, from http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj.

- Ferrer, J., Ringer, A., Saville, K., Parris, M. A., & & Kashi, K. (2022). Students’ motivation and engagement in higher education: The importance of attitude to online learning. Higher Education, 83(2), 317–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00657-5

- Görlitz, A., Ebert, T., Bauer, D., Grasl, M., Hofer, M., Lammerding-Köppel, M., & Fabry, G. (2015). Core competencies for medical teachers (KLM) a position paper of the GMA committee on personal and organizational development in teaching. GMS Zeitschrift für Medizinische Ausbildung, 32(2). https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000965

- Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., Altman, D. G., Barbour, V., Macdonald, H., Johnston, M., Lamb, S. E., Dixon-Woods, M., McCulloch, P., Wyatt, J. C., Chan, A.-W., & Michie, S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. British Medical Journal, 348(mar07 3), g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687

- Jokinen, H., Pramila-Savukoski, S., Kuivila, H.-M., Jämsä, R., Juntunen, J., Törmänen, T., Koskimäki, M., & Mikkonen, K. (2023). Development and psychometric testing of Hybrid Education Competence instrument for social, healthcare and health sciences educators. Nurse Education Today, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2023.105999

- Kaarlela, V., Mikkonen, K., Pohjamies, N., Ruuskanen, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kuivila, H., & Haapa, T. (2022). Competence of clinical nurse educators in university hospitals: A cross-sectional study. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research, 42(4), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/20571585211066018

- Koskimäki, M., Lähteenmäki, M., Mikkonen, K., Kääriäinen, M., Koskinen, C., Mäki-Hakola, H., Sjögren, T., & Koivula, M. (2021). Continuing professional development among social- and health-care educators. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 35(2), 668–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12948

- Koskimäki, M., Mikkonen, K., Kääriäinen, M., Lähteenmäki, M., Kaunonen, M., Salminen, L., & Koivula, M. (2022). An empirical model of social and healthcare educators’ continuing professional development in Finland. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(4), 1433–1441. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13473

- Kuivila, H.-M., Mikkonen, K., Sjögren, T., Koivula, M., Koskimäki, M., Männistö, M., Lukkarila, P., & Kääriäinen, M. (2020). Health science student teachers’ perceptions of teacher competence: A qualitative study. Nurse Education Today, 84, 104210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104210

- Lafortune, A., & Lakhal, S. (2020). Differences in students’ perceptions of the community of inquiry in a blended synchronous delivery mode. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 45(3). https://doi.org/10.21432/cjlt27839

- Lakhal, S., Mukamurera, J., Bédard, M., Heilporn, G., & Chauret, M. (2021). Students and instructors' perspective on blended synchronous learning in a Canadian graduate program. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(5), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12578

- Lee, I. C. J., Wong, P., Goh, S. P. L., & Cook, S. (2022). A synchronous hybrid team-based learning class: Why and How to do it? Medical Science Educator, 32(3), 697–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-022-01538-5

- Liao, N., Scherzer, R., & Kim, E. H. (2022). Effective methods of clinical education. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, 128(3), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2021.11.021

- Medical Research Act 488/1999. (1999). Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland. Retrieved April 11, 2023, from https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/1999/en19990488_20100794.pdf.

- Mikkonen, K., Koivula, M., Sjögren, T., Korpi, H., Koskinen, C., Koskinen, M., Kuivila, H.-M., Lähteenmäki, M.-L., Koskimäki, M., Mäki-Hakola, H., Wallin, O., Saaranen, T., Sormunen, M., Kokkonen, K.-M., Kiikeri, J., Salminen, L., Ryhtä, I., Elonen, I., & Kääriäinen, M. (2019a). TerOpe -key project. Social, health care and rehabilitation educators´ competence and development: Competent educators together! University of Oulu. Juvenes Print (in Finnish).

- Mikkonen, K., Koskinen, M., Koskinen, C., Koivula, M., Koskimäki, M., Lähteenmäki, M., & Kääriäinen, M. (2019b). Qualitative study of social and healthcare educators’ perceptions of their competence in education. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(6), 1555–1563. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12827

- Mikkonen, K., Kuivila, H., Sjögren, T., Korpi, H., Koskinen, C., Koskinen, M., & Kääriäinen, M. (2022). Social, health care and rehabilitation educators’ competence in professional education—Empirical testing of a model. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(1), e75–e85. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13414

- Mikkonen, K., Ojala, T., Koskinen, M., Piirainen, A., Sjögren, T., Koivula, M., Lähteenmäki, M. L., Saaranen, T., Sormunen, M., Ruotsalainen, H., Salminen, L., & Kääriäinen, M. (2018). Competence areas of health science teachers – A systematic review of quantitative studies. Nurse Education Today, 70, 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.08.017

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Sage.

- National League for Nursing. (2018). NLN Core Competencies for Academic Nurse Educators. Strengthening the Future of the Nursing Workforce. Retrieved January 17, 2023, from https://www.nln.org/education/nursing-education-competencies/core-competencies-for-academic-nurse-educators.

- Oprescu, F., McAllister, M., Duncan, D., & Jones, C. (2017). Professional development needs of nurse educators. An Australian case study. Nurse Education in Practice, 27, 165–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2017.07.004

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2018). Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice (9th ed., International edition). Wolters Kluwer.

- Pramila-Savukoski, S., Kärnä, R., Kuivila, H., Juntunen, J., Koskenranta, M., Oikarainen, A., & Mikkonen, K. (2022). The influence of digital learning on health sciences students’ competence development – A qualitative study. Nurse Education Today, 120, 105635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105635

- Pramila-Savukoski, S., Kärnä, R., Kuivila, H., Oikarainen, A., Törmänen, T., Juntunen, J., Järvelä, S., & Mikkonen, K. (2023). Competence development in collaborative hybrid learning among health sciences students: A quasi-experimental mixed-method study. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39(6), 1919–1938. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12859

- Raes, A. (2021). Exploring student and teacher experiences in hybrid learning environments: Does presence matter? Postdigital Science and Education, 4(1), 138–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-021-00274-0

- Raes, A., Detienne, L., Windey, I., & Depaepe, F. (2020). A systematic literature review on synchronous hybrid learning: Gaps identified. Learning Environments Research, 23(3), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-019-09303-z

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

- Ryhtä, I., Elonen, I., Hiekko, M., Katajisto, J., Saaranen, T., Sormunen, M., Mikkonen, K., Kääriäinen, M., Sjögren, T., Korpi, H., & Salminen, L. (2021). Enhancing social and health care educators’ competence in digital pedagogy: A pilot study of educational intervention. Finnish Journal of EHealth and EWelfare, 13(3), https://doi.org/10.23996/fjhw.107466

- Saichaie, K. (2020). Blended, flipped, and hybrid learning: Definitions, developments, and directions. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 164(164), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20428

- Salminen, L., Tuukkanen, M., Clever, K., Fuster, P., Kelly, M., Kielé, V., Koskinen, S., Sveinsdóttir, H., Löyttyniemi, E., & Leino-Kilpi, H. (2021). The competence of nurse educators and graduating nurse students. Nurse Education Today, 98, 104769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104769

- Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., & Moher, D. (2010). CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 115(5), 1063. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d9d421

- Shi, Y., Tong, M., & Long, T. (2021). Investigating relationships among blended synchronous learning environments, students’ motivation, and cognitive engagement: A mixed methods study. Computers and Education, 168, 104193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104193

- Singh, J., Steele, K., & Singh, L. (2021). Combining the best of online and face-to-face learning: Hybrid and blended learning approach for COVID-19, post vaccine, & post-pandemic world. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 50(2), 140–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472395211047865

- Sormunen, M., Heikkilä, A., Salminen, L., Vauhkonen, A., & Saaranen, T. (2021). Learning outcomes of digital learning interventions in higher education: A scoping review. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 40(3), 154–164. https://doi.org/10.1097/CIN.0000000000000797

- Suárez-Rodríguez, J., Almerich, G., Orellana, N., & Díaz-García, I. (2018). A basic model of integration of ICT by teachers: Competence and use. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(5), 1165–1187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-018-9591-0

- Töytäri, A., Piirainen, A., Tynjälä, P., Vanhanen-Nuutinen, L., Mäki, K., & Ilves, V. (2016). Higher education teachers’ descriptions of their own learning: A large-scale study of Finnish Universities of Applied Sciences. Higher Education Research and Development, 35(6), 1284–1297. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1152574

- Vlies, R. v. d. (2020). Digital strategies in education across OECD countries: Exploring education policies on digital technologies. https://doi.org/10.1787/33dd4c26-en

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological process. Harvard University Press.

- Wang, Q., & Huang, C. (2018). Pedagogical, social and technical designs of a blended synchronous learning environment. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(3), 451–462. https://doi-org.pc124152.oulu.fi:9443/10.1111/bjet.12558

- Wang, Q., Huang, C., & Quek, C. L. (2017). Students’ perspectives on the design and implementation of a blended synchronous learning environment. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3404

- WHO (World Health Organization). (2013). Global health workforce shortage to reach 12.9 million in coming decades. WHO publication. Retrieved January 17, 2023, from https://apps.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/health-workforce-shortage/en/index.html.

- WHO (World Health Organization). (2016). Nurse Educator Core Competencies. WHO Document Production Services, Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved January 17, 2023, from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/nurse-educator-core-competencies.

- Zydney, J. M., McKimmy, P., Lindberg, R., & Schmidt, M. (2018). Here or there instruction: Lessons learned in implementing innovative approaches to blended synchronous learning. TechTrends, 63(2), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0344-z