ABSTRACT

The targeting of ethnic Chinese voters is a relatively hidden area in New Zealand politics. This article explores how the two major parties in New Zealand, National and Labour, employed political marketing to target Chinese voters in the 2020 election. The findings reveal that National’s targeting approach lacked clear direction and structure, while Labour failed to demonstrate explicit intentions in targeting the Chinese community. Neither party exhibited a comprehensive understanding of this ethnic group nor developed effective political products to address their concerns. These shortcomings in targeting can be attributed to the broader context of National’s chaotic 2020 election campaign and Labour’s apparent disinterest in engaging with Chinese voters during an election where it already enjoyed a high approval rate among the public. The incomplete targeting efforts by both parties reflect the unique context of an election dominated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

The targeting of ethnic minority voters in elections is an increasingly prevalent phenomenon in western democracies. Recent notable instances include the Labour Party’s mobilisation of black, Asian, and minority ethnic voters in the 2019 UK general election (Walker Citation2019), as well as the Conservative Party of Canada’s focus on Asian voters since the 2006 Federal Election (Kwak Citation2017). While scholars have explored the motivations behind parties’ pursuit of ethnic votes and the role of ethnic minority candidates in elections (Chan and Zhao Citation2023; Landa, Copeland, and Grofman Citation1995; Zingher and Steen Thomas Citation2012), little is known about the specific strategies employed by parties to secure ethnic minority support. This article aims to bridge the gap by applying the concept of market orientation to investigate the extent to which New Zealand’s two major parties, National and Labour, adopted a market-oriented approach to target Chinese voters in the 2020 election.

The focus on New Zealand stems from the country’s distinctively inclusive political culture (Barker and McMillan Citation2014; Friesen Citation2015), which allows parties to target minority groups without concern for negative reactions from the majority electorate. A contrasting example can be observed in Germany, where two major parties displayed reluctance to nominate candidates with minority backgrounds to secure support among majority voters (Da Fonseca Citation2011, 109–27). Particularly under the Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) electoral system, New Zealand parties have demonstrated a greater willingness to appeal to ethnic minority voters (Banducci, Donovan, and Karp Citation2004; Nagel Citation1995).

This article starts by reviewing the literature on ethnic targeting and examining its prevalence in three parliamentary democracies with significant histories of migration and race relations: the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia. This section offers a theoretical framework of market orientation and provides a contextual understanding of the targeting of Chinese voters in a broader perspective.

The following part offers an overview of Chinese New Zealanders and examines how both the National and Labour parties have targeted this community in previous elections, with a particular focus on the 2017 election. Moving forward, the article delves into the context of the 2020 election, which took place amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, and applies market orientation principles to this unique ‘COVID election’. It discusses the distinct strategies employed by the two major political parties, uncovering several noteworthy issues. These include the challenges of launching a traditional targeting campaign amidst the pandemic, National’s inability to uphold trust within the Chinese community, Labour’s suboptimal utilisation of WeChat (China’s most popular chat and social media app) in its election campaign, and the limited targeting efforts towards Chinese voters by both parties in this particular election.

In the final section, I draw conclusions by discussing the implications of these findings. I argue that the incomplete targeting of Chinese voters by both parties in the 2020 election reflects the exceptional circumstances of an election overshadowed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ethnic targeting in literature

Targeting in election campaigns is typically accompanied by segmentation and positioning activities, collectively determining the target audience, the means of reaching them, and the political products or messages to convey (Baines, Harris, and Lewis Citation2002; Newman Citation1994; Smith and Hirst Citation2001). It is widely recognised that floating voters, characterised by their lack of party loyalty, have a higher likelihood, if not the highest likelihood, of influencing a party’s success in an election (Burton and Miracle Citation2014; Calvert Citation1985; Chappell and keech Citation1986). Consequently, parties have placed great importance on prioritising electorates based on their level of support. For instance, the UK Labour Party identified segments such as ‘Jack’ (representing the new style of Labour), ‘Old Fred’ (representing the old style of Labour), and ‘floating left’ in the 1970s (Rosenbaum Citation1997, 200–8). Likewise, the Conservative Party of Canada categorised the electorate into groups such as ‘hard Tories’, ‘soft Tories’, ‘soft others’, and ‘hard others’, based on their inclination to vote Conservative (Delacourt Citation2016, 76).

Ethnic minority voters, with their rapidly increasing numbers and distinctive political behaviour, have captured the attention of parties and emerged as a key target in elections. Research on ethnic minority politics indicates a tendency for migrant and ethnic minority voters to lean towards left-wing parties (Cain, Roderick Kiewiet, and Uhlaner Citation1991; Heath et al. Citation2013). However, like their white counterparts, they also prioritise performance issues and do not automatically align themselves with left-wing parties (Sanders et al. Citation2014; Zingher and Steen Thomas Citation2012). For instance, studies focusing on Asian Americans and Asian Australians highlight that Asian voters often exhibit lower levels of party identification (Chong and Kim Citation2006; Pietsch Citation2018), making them an appealing target for both left-wing and right-wing parties.

Targeting Asian voter has been a common practice by major political parties in the UK, Canada, and Australia. In the UK, despite the fact that ethnic minority groups predominantly supported the Labour Party, the Conservatives actively pursued Asian voters, particularly Indian voters, starting from the 1997 election, acknowledging them as ‘the most economically successful and culturally conservative ethnic minorities’ (Sobolewska Citation2013, 619). In the 2015 general election, the Conservative Party experienced a surge in its vote share among minority groups and, for the first time, surpassed Labour’s vote share among Hindu voters (Martin Citation2019).

Similarly, the Conservative Party of Canada specifically focused on Chinese and South Asian voters in its campaigns leading up to the 2006 and 2011 federal elections, recognising a perceived alignment between their socially conservative values and the party’s platform (Marwah, Phil, and Stephen Citation2013). In the Australian 2019 federal election, both major parties, the Australian Labour Party and the Liberal Party of Australia, nominated Chinese candidates to appeal to Chinese voters in the middle-suburban Melbourne seat of Chisholm (Ratcliff, Jill, and Juliet Citation2020. The Liberal campaign utilised Chinese language signs and the messaging platform WeChat to distribute information, indicating a targeted approach towards the Chinese community.Footnote1

Although ethnic targeting has become prevalent, our understanding of the strategies employed by parties to appeal to these voters primarily relies on media reports and limited literature. These sources have shed light on various actions taken by parties, including nominating candidates with minority ethnic backgrounds (e.g. Farrer and Zingher Citation2018; Taylor Citation2021), engaging with ethnic media outlets (e.g. Martin Citation2019; Taylor Citation2021), visiting religious sites and events significant to different minority voters (e.g. Kwak Citation2017; Martin Citation2019), and implementing targeted policies (e.g. Booth and Syal Citation2019; Walker Citation2019; White Citation2017). However, the absence of a comprehensive theoretical framework restricts our ability to conduct a thorough analysis of these targeting practices, let alone examine parties’ targeting strategies.

Examining parties’ targeting through the lens of market orientation can provide a starting point for analysis. While scholars use different frameworks and models to explore market orientation, there is a consensus that it involves placing voters at the centre of decision-making and being responsive to their concerns (Lees-Marshment Citation2001; Newman Citation1994; O’Cass Citation2001; Ormrod Citation2005). A party with a market-oriented targeting strategy is expected to identify voter demands and tailor its offerings accordingly. By embracing market orientation, political parties can adeptly comprehend and address voter opinions and concerns, thereby guaranteeing the inclusion and recognition of voices from ethnic minority voters in the formulation of more representative political agendas.

Applying the concept of market orientation to ethnic targeting, we can examine a party’s targeting strategy through the following principles, as listed in . Each principle will be briefly explained.

Table 1. Market-oriented ethnic targeting principles.

Building trust with the ethnic community

Gaining the trust of the target groups is a crucial first step for a party. Voter trust is a relational concept, based on the belief that the party will effectively represent the interests of its supporters and act in accordance with their expectations (Levi and Stoker Citation2000; Elaine, Schiffman, and Thelen Citation2008. Building this trust is a process that fosters confidence in the party (Scammell Citation1999). Once trust is established, targeted voters are more likely to be open to the party’s political offerings, such as its policy positions, even if their specific concerns are not directly addressed (Elder Citation2016).

Utilising market intelligence to comprehend the community’s concerns

To produce voters’ satisfaction, a party needs to understand its target market. Lees-Marshment’s Market-oriented Party model (Lees-Marshment Citation2014) suggests that conducting market intelligence is the first step for a party to achieve a market orientation. The information derived from market analysis would help a party learn its target, allocate its resources, and decide on its target products. Particularly in the case of targeting ethnic minority voters, a party needs to identify how different policy areas (e.g. education, employment, housing, law and order, tax, immigration) would affect its target group and sell its policy positions accordingly (Landa, Copeland, and Grofman Citation1995).

Tailoring political offering to address the specific needs of the community

The political products offered by parties during elections encompass various elements, including ideology (values, beliefs, and visions), party leaders and candidates, and policies (Lloyd Citation2005). Among these, policies are considered central by academics (O’Shaughnessy Citation2001). However, it can be challenging for a catch-all party to develop specific policies that exclusively benefit a particular ethnic group. Therefore, the focus shifts to selecting policies that can address the demands of the target groups, guided by market intelligence. By strategically positioning these target products, parties can effectively engage with ethnic communities and tailor offerings to meet their needs and aspirations.

Engaging with the community

Market-oriented communication during an election campaign can be developed through market analysis and target products. According to Robinson’s voter orientation model (Robinson Citation2010), a party can demonstrate its market orientation through advertisements that depict the party listening to the concerns of the target voters, using caring language, and making policy promises. In addition to crafting the right messages, a party must also select appropriate communication channels to effectively reach the target groups, such as ethnic language media and social media platforms.

The next section will provide the background of targeting Chinese voters in New Zealand and subsequently employ these market orientation principles to evaluate National and Labour’s targeting strategies in the 2020 election.

Contextualising the targeting of Chinese voters

In New Zealand, a significant proportion, 42.4%, of the population identifies with at least one ethnic minority ethnicity (Statistics New Zealand Citation2019). Among the non-European ethnic groups, the top three in terms of population are Māori (16.5%), Pacific peoples (8.1%), and Asian (15.1%) (Statistics New Zealand Citation2020). Specifically, the Chinese community represents the third-largest ethnic group, comprising 5.3% of New Zealand’s population and accounting for 35.0% of the Asian population (Statistics New Zealand Citation2020).

Efforts by New Zealand parties to compete for ethnic votes have been observed since 1996, particularly under the MMP electoral system where the party vote determines the number of seats each party receives in Parliament. The New Zealand Labour Party, New Zealand First, and the Māori Party have long competed for Māori electorates (Vowles, Coffé, and Curtin Citation2017, 215–40). The Labour Party has garnered significant support from Pasifika voters, as evidenced by its largest Pacific caucus following the 2017 election (Hopgood Citation2020). Furthermore, the nomination of Asian candidates in electorates with a high number of Asian residents has been a recurring phenomenon during elections. In 2020, New Zealand elected its most diverse Parliament ever, with 20.8% Māori, 9.2% Pasifika, and 6.7% Asian representation among MPs (Electoral Commission Citation2021; New Zealand Parliament Citation2021).

Ethnic Chinese voters, despite historically exhibiting a tendency for lower turnout compared to other ethnic groups (Huang Citation2023, 88–93), have increasingly emerged as a strategically targeted demographic in elections since the 2000s. Three key factors underpin this shift. Firstly, the Chinese community stands as New Zealand’s third-largest ethnic group (Statistics New Zealand Citation2020), thereby yielding substantial influence in the calculus of party votes. Secondly, while a politicalparticipation gap has been noted between Chinese New Zealanders and other ethnic communities, insights derived from the New Zealand General Social Survey challenge the notion that the relatively diminished turnout among Asian voters is exclusively a product of their ethnicity (Statistics New Zealand Citation2014, 8–9). In fact, a body of literature on ethnic voting suggests that within the same ethnic group, variations exist between native-born and foreign-born individuals, immigrants from democracies and non-democracies, as well as recent and long-term immigrants, leading to different turnout rates (Lien Citation2010; Wass et al. Citation2015). These findings indicate that the Chinese community, given its inherent diversity, possesses the potential for political engagement at a level commensurate with the majority population.

Furthermore, there is a pressing need for political parties, especially major ones, to cultivate an inclusive and diverse party image by engaging with Chinese voters. For instance, National, under the leadership of John Key since 2006, embarked on an effort to foster an image of a more inclusive party (Edwards Citation2009, 13–32), while Labour, led by Helen Clark since the 1990s, earned recognition for its commitment to acknowledging ‘the important contribution of ethnic communities in New Zealand’ (Hawkins Citation2001).

Indeed, political parties have recognised the challenge of relatively low turnout within the Chinese community. During the 2014 election campaign, a Mandarin forum was convened in Auckland, attended by several ethnic Chinese candidates, aimed at encouraging Chinese migrants to exercise their voting rights (Tan Citation2014).

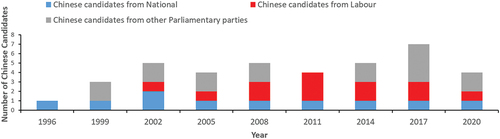

This strategic focus on the Chinese community is evident in the increasing number of parties selecting candidates with a Chinese ethnic background, as depicted in . Recognising the significance of this community, a senior MP from the New Zealand Labour highlighted in an interview I conducted in May 2021 that ‘any political party that ignored a community of that size would be foolish’. Notably, the National Party has actively sought a relationship with the Chinese community through initiatives like the Blue Dragons, while the Labour Party has established connections with the Chinese community through its multicultural sector.Footnote2

Figure 1. Number of candidates with Chinese ethnic background nominated by parties, 1996–2020 elections. Data set compiled by the author.

Both parties have recognised the significance of engaging with the Chinese community as part of their electoral strategies, and the 2017 election served as a notable example of their targeted efforts. The National Party established a strong connection with the Chinese community through the involvement of its Chinese ethnic MP, Jian Yang, who contributed columns to various Chinese language media outlets (McMillan and Barker Citation2021). It also utilised platforms like the party’s official WeChat account and the creation of the Chinese group, Blue Dragons, in 2016 to effectively communicate National’s policies and directly engage with Chinese voters. The party leaders, John Key and Bill English, actively sought coverage in the Chinese-language media and made multiple visits to the Chinese community before, during, and even after the 2017 election campaign.Footnote3

The Labour Party, although losing its experienced Chinese ethnic MP Raymond Huo after the 2014 election, demonstrated its commitment to maintaining connections with the Chinese community through the party leaders Andrew Little and Jacinda Ardern. Both leaders made appearances on talk shows hosted by Chinese language media, working to improve Labour’s perception among the Chinese community during the party's 2017 election campaign. (Skykiwi Citation2015, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Ardern, in particular, conveyed positive messages when addressing Labour’s lower approval ratings within the Chinese community (Skykiwi Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Moreover, the Labour team showcased responsiveness to the concerns of Chinese voters, including issues related to law and order and immigration.

These concerted efforts by both parties underscore their commitment to engaging with the Chinese community and tailoring their targeting strategies to effectively connect with Chinese voters during election campaigns.

2020 New Zealand general election

For the first two years of the 2017–2020 electoral term, polls suggested a close race between the two major parties. National even held a slight lead over Labour in the party vote from June 2019 to February 2020 (1 NEWS Colmar Brunton Poll Citation2020). However, the COVID-19 pandemic drastically changed the political landscape in March 2020. A state of emergency was declared on 25 March 2020, and New Zealand implemented various COVID-19 alert level lockdowns in the following months. The election itself was delayed by a month due to a COVID-19 lockdown in Auckland, resulting in a halt to most political campaigning (Levine Citation2021, 33–77; Ziena Citation2021, 35–46).

The 2020 election, overshadowed by the COVID-19 response and rebuilding efforts, was further characterised by chaos within the National Party. The party experienced two leadership changes and faced several scandals at the start of the election campaign. Additionally, both major parties saw the retirement of their experienced Chinese ethnic MPs at the outset of their election campaigns due to controversy surrounding their background, which added to the challenges (Elder et al. Citation2021, 109–20). The new Chinese ethnic candidates of both parties had limited time to understand the concerns of Chinese voters and build trust with the community.

Furthermore, concerns about China’s influence in New Zealand politics may have prompted both parties to exercise caution when targeting Chinese voters in the 2020 election. Multiple media reports published after 2017 underscored China’s growing impact on New Zealand elections (e.g. Fisher and Nippert Citation2017; RNZ Citation2017, Citation2021). Speculation in the media also arose regarding the reasons behind the resignations of two Chinese MPs and their connections with the Chinese government (Cheng Citation2020; RNZ Citation2020). In this context, both major parties were notably meticulous in their efforts to secure Chinese votes, which might have led to a more hands-off approach. This created a complex and challenging environment for both parties in devising their strategies to garner Chinese votes in the 2020 election.

National’s targeting of Chinese voters in 2020

During the 2020 election campaign, National’s ties with the Chinese community weakened. The trust between the party and its Chinese supporters diminished due to the leadership changes leading up to the election. Neither Todd Muller (Leader of the National Party from 22 May 2020, to 14 July 2020) nor Judith Collins (Party leader from 14 July 2020, to 25 November 2021) had sufficient time to connect with the community amidst the ongoing chaos within the party. Stuart Mullin, the Director of Campaign Operation for the National Party in the 2020 election, highlighted this issue in an interview I conducted in June 2021:

There was so much going on. She (referring to Judith Collins) cannot focus on everything … she was always interested in what’s happening and asked questions if there is something in Chinese media—‘do we have presence? Yes, good!’ Then she would move on to the next crisis that she had to try and fix.

The loss of National’s senior Chinese ethnic MP, Jian Yang, further hindered the party’s connection with the Chinese community. Yang, who had been National’s list MP since 2011 and was considered the most influential Chinese ethnic politician in a 2017 Chinese poll (Tan Citation2017), retired in July 2020, creating a void in National’s link with the community. Adding to the challenge, National nominated Nancy Lu as a list candidate in August 2020 without consulting the Chinese community, giving her limited time to establish name recognition and repair the connection with Chinese voters.

The COVID-19 restrictions during the election posed additional obstacles for National in engaging with Chinese voters. The party was unable to organise large campaign events that could have strengthened relations. Instead, National was forced to launch its election campaign online and cancel significant campaign events (Walls Citation2020). Had these events proceeded as planned, they could have provided valuable opportunities to showcase the Blue Dragons and cultivate stronger connections with Chinese voters, as affirmed by Mullin during the research interview. Mullin also noted that the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted National’s initial plans to employ formal market intelligence regarding Chinese voters.

As a result, National was unable to rely on market analysis to inform its targeting strategy in the 2020 election. Instead, it had to depend on party staff to understand the needs and wants of the Chinese community. However, this approach proved ineffective. The party lost focus on the concerns of Chinese voters and mistakenly assumed that the Chinese constituency would behave similarly to the general population in this ‘Covid election’. Tim Hurdle, National’s 2020 Campaign Director, argued during my research interview that the declining support for National among the Chinese community ‘reflects a national trend’. Despite this, some electoral candidates did recognise specific policy areas that would resonate with the Chinese community based on their experiences. For example, Simeon Brown, National’s MP for Pakuranga since 2017, highlighted education as one policy area that would appeal to Chinese voters in the interview for this research.

At the party level, National was unable to tailor its offerings to cater specifically to Chinese voters. The key elements that had previously contributed to National’s successful appeal, such as its leadership, brand of economic competence, and close relations with the Chinese community, were compromised in 2020. The leadership change just three months before the election prevented National from adequately introducing its new leader, Judith Collins, to Chinese voters. Furthermore, the party was unable to highlight its fiscal credentials due to a significant flaw in its flagship economic policy, which revealed a $4 billion hole (Malpass Citation2020). Additionally, apprehensions about China’s impact on New Zealand raised challenges for National in leveraging its close ties with China and aligning itself with the Chinese community, as it had effectively accomplished during the John Key era.

Due to the lack of appealing target products, National’s online engagement with the Chinese community was noticeably inactive. This was evident through its limited activity on Chinese social media platforms, particularly on its official WeChat account, where it only posted 14 times within a 120-day campaign period. Despite the party’s recognition of the importance of WeChat in election campaigns, as highlighted by its three-term Chinese ethnic MP Yang in my research interview, the campaign team faced challenges in effectively utilising the platform in 2020. As illustrated during my research interviews, Campaign Operation Director Mullin admitted his lack of comprehension, stating, ‘I don’t understand the platform, but I was told it was very good in terms of following’. Similarly, Campaign Director Hurdle expressed the desire for more time to familiarise himself with this Chinese social media channel.

Moreover, National’s engagement with the Chinese community was further undermined by its inconsistent presence in Chinese language media. A notable instance of this inconsistency occurred during a press conference held with the Chinese language media on 13 July 2020, where National’s finance spokesperson, Paul Goldsmith, took the lead and emphasised the commitment of Party Leader Todd Muller to address the demands of the Chinese community and strengthen the connection with Chinese voters (Skykiwi Citation2020f). However, just one day after the conference, Muller resigned as the Party Leader and was succeeded by Judith Collins.

National did not continue its Party Leader’s Column in Chinese Herald (the largest Chinese language newspaper in New Zealand) and Skykiwi (the largest Chinese language website in New Zealand) after the 2017 election. The party’s Chinese MP Columns ceased updating since August 2021. In a research interview, Mullin attributed this communication gap to Jian Yang’s retirement, stating,

It wasn’t just three weeks before the election we put ads, we made sure Jian had columns in different newspapers that were regular and keeping that consistent voice.

One thing we really struggled when changing Jian to Nancy was keeping that voice, even the way the writing has done—Jian had a particular style. Losing that style is very damaging to the communication itself.

In summary, National’s attempts to target the Chinese community in the 2020 election faced several hindrances. The party’s limited understanding of the concerns and preferences of Chinese voters resulted in a lack of appealing target products. Furthermore, National’s utilisation of ethnic platforms like WeChat was limited, and its presence in Chinese language media was inconsistent. These challenges were exacerbated by leadership changes and the retirement of Jian Yang, further diminishing the party’s engagement with the Chinese community.

Labour’s targeting of Chinese voters in 2020

Despite the challenges posed by COVID-19 restrictions during the 2020 election campaign, Labour maintained a significant lead over National in opinion polls (New Zealand Herald Citation2020). This advantage provided Labour with an opportunity to further strengthen its relationship with Chinese voters. However, the party’s efforts in this regard were minimal. Jacinda Ardern, Labour’s leader and the party’s most prominent figure in the 2020 election campaign, had made little effort to establish a connection with the Chinese community throughout the 2017–2020 period. This lack of engagement risked giving the impression that Labour had little interest in the Chinese community, as indicated by Kai Luey, the Chair of the Auckland Chinese Community Center, in my research interview:

We have this thing: invite community leaders and political guests and all that, to this function upstairs at the Chinese New Year, and we would have up to 150 people there because they stayed there and wanted to network and intermingle.

Jacinda? No, never. And that’s the attitude of the Labour Party. Whereas Helen Clark used to want to mingle, but it all depends on the person I suppose. But the attitude of Labour recently …

One of the key reasons for Labour’s significant lead in election polls was its effective management of the COVID-19 pandemic, as emphasised by a senior MP from Labour in the research interview: ‘Obviously in 2020, if you sit down and ask what’s the most important issue, everyone would say COVID’. The Chinese community expressed satisfaction with the Labour-led government’s handling of the virus, as evidenced by a survey of 1,364 ethnic Chinese individuals conducted by Trace Research two months before the election, where 75.0% of respondents approved of the government’s response to COVID (Chen Citation2020). This suggested that the approval could potentially translate into support for Labour in the election.

However, it is important to acknowledge that a notable gap exists between the Chinese community’s overall satisfaction with the government’s pandemic response and Labour’s electoral support among Chinese voters. The Trace Research survey, for instance, indicated that only 21.0% of Chinese respondents supported Labour (Chen Citation2020),Footnote4 and the New Zealand Vote Compass survey data suggested this figure reached 33.9% in 2020 (As cited in Huang Citation2023, 106).Footnote5 Despite these discrepancies in survey findings,Footnote6 the observed disparity between the community’s approval of the government’s pandemic management and its support for Labour highlights the need for the party to make more compelling appeals to acquire Chinese votes.

Although Labour’s senior MP Michael Wood (MP for Mt Roskill since 2017) identified law and order as one policy area that Chinese voters were particularly concerned about in my research interview, the issue did not feature prominently in Labour’s targeting strategy. Labour’s Chinese ethnic MP, Naisi Chen, explained during the interview that Labour aimed to win over Chinese voters by serving the entire country. Chen emphasised that,

We recognised that actually if you do well for the whole of New Zealand, the Chinese community recognise that. You don’t need to necessarily, specifically … at least I don’t think it’s always a best way to segregate the values of the Chinese community and endorse a separate set of values to the rest of New Zealand.

Indeed, in a policy-free election like the one in 2020 where both parties campaigned on similar policy platforms (Seabrook-Suckling Citation2020), it would have been challenging for any party to identify target policies. In the case of Labour, the campaign revolved around Jacinda Ardern, highlighting the party’s successful pandemic management and the public’s desire for stability. However, due to Ardern’s limited engagement with the Chinese community during her first term, her leadership might not have strongly resonated with this demographic. Moreover, the party lacked a clear strategy on how to effectively target its offerings to maximise support within the Chinese community. While the emphasis on stability in the campaign could have appealed to Chinese voters, the party failed to effectively communicate this vision to the Chinese community.

Another crucial aspect to consider in targeting Chinese voters is the nomination of Labour’s Chinese ethnic candidate, Naisi Chen. On one hand, Chen actively sought exposure in Chinese language media and served as Labour’s messenger to the Chinese community during the election, as she mentioned in the research interview: ‘I think I was on average at least on one or two interviews every single week, just to make sure I constantly being able to communicate our policies and our positions on a lot of things’. On the other hand, Chen approached her 2020 campaign with caution, likely influenced by the increasing concerns about China’s influence on New Zealand politics. As a result, she avoided directly presenting herself as a representative of the Chinese community and instead focused on representing youth, migrants, and women. This approach was evident in her 2020 campaign launch as Labour’s candidate for Botany (Times Online Citation2020):

Since coming to New Zealand at the age of five, I understand the experience of all migrant New Zealanders and the important, ever-changing role we play in society. I want to represent my generation by joining the Labour Party team that will keep New Zealand moving.

Similar to National, Labour’s use of Chinese social media platforms was ineffective. On its official WeChat account, Labour posted 60 times within 120 days before the election day. However, 51 out of these 60 posts were mere translations, randomly listing Labour’s election policies in Chinese alongside their English versions. This approach made the platform feel more like an English learning channel rather than a means of genuine communication with their Chinese followers.

Being the incumbent government, Labour had more visibility among Chinese voters leading up to the election. For instance, in April 2020, Labour’s Chinese ethnic MP Raymond Huo conducted a live interview with Skykiwi, discussing the government’s COVID management measures (Skykiwi Citation2020e). Additionally, during the reveal of Budget 2020, the Finance Minister Grant Robertson appeared on a Skykiwi talk show accompanied by Huo, explaining how the budget would rebuild New Zealand’s economy and encouraging the audience to download the NZ COVID Tracer app (Skykiwi Citation2020b). Other Labour MPs, such as the Minister of Revenue Stuart Nash and the Minister of Justice Andrew Little, also appeared on Skykiwi talk shows to clarify government policies (Skykiwi Citation2020a, Citation2020d).

Interestingly, these shows featuring Labour MPs were less influential compared to one featuring former Prime Minister and National’s former leader, John Key, and National’s Botany candidate Christopher Luxon (Skykiwi Citation2020c). The talk show with Key and Luxon generated 147 comments, while the four shows featuring Labour MPs combined only received 58 comments. Although not definitive, this suggests that if Labour had more well-known figures interacting with Chinese voters, it could have garnered greater interest from the Chinese community.

Ultimately, Labour’s approach to appealing to Chinese voters in 2020 was problematic. Despite the high approval of its COVID management among the Chinese community, the party failed to capitalise on this opportunity to strengthen its relationship with them. Additionally, Labour did not effectively select specific offerings to target the Chinese community, instead treating their concerns as identical to those of the general New Zealand voters. While the party had more visibility among Chinese voters leading up to the election, the lack of distinct policy offerings and effective messengers hindered its ability to maximise its influence and support within the community.

Discussion and conclusion

In evaluating the market orientation adopted by National and Labour to target Chinese voters in the 2020 election, three conclusions can be drawn. Firstly, National’s targeting approach was characterised by a lack of direction and structure. The party failed to maintain a long-term relationship with the Chinese community and did not offer effective targeting products. In fact, National’s campaign during the election appeared more reactive than strategic, reflecting the party’s overall crisis mode. Consequently, the Chinese community was largely overlooked in National’s campaign efforts as the party focused on preventing the collapse of its core voter base. This neglect of the Chinese community was not surprising given the circumstances and priorities of National’s campaign.

Secondly, Labour’s messaging directed towards Chinese voters in the 2020 election lacked clarity and directness. Despite nominating a Chinese ethnic candidate and having senior party members engage with Chinese language media, the party primarily relied on converting broader government messages to resonate with the Chinese community rather than demonstrating a genuine responsiveness to their specific concerns. As a result, Labour missed an opportunity to establish a meaningful connection with the Chinese community during the election.

That being said, it’s important to note that Labour gained increasing support from the Chinese community in the 2020 election. According to the New Zealand Vote Compass data, Labour’s backing among Chinese constituents rose by 9.4% in 2020 compared to 2017 (As cited in Huang, 106). The New Zealand Election Study data for 2020, while based on a relatively small sample of just over 100 ethnic Chinese respondents, showed a similar trend, with Labour’s support growing by 8.7% since 2017 (Vowles et al. Citation2022). This suggests a strong possibility that Labour gained some Chinese support due to its COVID response.

Finally, it can be concluded that neither major party demonstrated a market-oriented approach in targeting Chinese voters during the 2020 election. Concerns about China’s influence in New Zealand politics likely contributed to a sense of unease and caution within both parties when it came to courting Chinese votes that year. In practice, both parties operated under the assumption that Chinese voters would align their priorities with the general population during what was known as the ‘COVID election’, leading to a lack of tailored policy offerings. They failed to grasp and address the specific concerns of the Chinese community. In contrast to the 2017 election, both parties’ interactions with Chinese voters remained primarily at the level of individual electoral candidates rather than adopting a comprehensive party-level approach.

The incomplete targeting of Chinese voters in the 2020 election highlights the risk of neglecting the demands of ethnic voters. While parties often target ethnic minority groups to gain electoral support, a market-oriented approach as a long-term strategy aims to proactively integrate ethnic minorities into a party’s agenda by being responsive to their concerns. It is crucial for both parties to actively listen to the voices of Chinese voters and develop substantial targeting products to address their specific concerns in future elections. Additionally, the application of an analytical theory framework, such as the concept of market orientation within the realm of political marketing, provides a valuable starting point for analysing parties’ ethnic targeting efforts. However, to conduct a comprehensive analysis of parties’ ethnic targeting strategies, a more robust analytical framework is needed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Luna L. Zhao

Luna L. Zhao is a PhD candidate in Politics and IR at the University of Auckland. Her doctoral thesis encompasses an interdisciplinary examination of ethnic Chinese New Zealand voters, employing a blend of qualitative and quantitative analysis. Luna's research interests primarily revolve around New Zealand politics, ethnic minority voters, Asian studies, and the dynamics of elections in democratic systems. She has recently published works on Taiwan politics and the 2020 New Zealand General Election.

Notes

1. Please be aware that the Liberal Party also disseminated misleading instructions on how to vote in the Chinese language. See Paul Karp, “Labor Mulls Legal Challenge Over Misleading How-to-vote Instructions on WeChat’, The Guardian, last modified May 28, 2019. www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/may/28/.

2. Blue Dragons changed its name to Chiwi Nats after the 2020 election. For more information about Chiwi Nats, please visit its Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/Chiwi-Nats-108523044829206/.

The Labour Party has a dedicated multicultural section within its party structure, as confirmed in interviews. This section specifically focuses on cultivating and strengthening relationships with diverse minority groups, such as ethnic minorities and LGBTQ communities.

3. National leaders’ visits to Chinese-language media in 2016 and 2017 were documented on the party’s WeChat account.

4. The Trace Research primarily conducted the Chinese voter poll on its online survey platform and social media platforms like WeChat. As a result, the sample it gathered may be skewed by the representation of the Chinese population in New Zealand.

5. The 2020 Vote Compass was conducted between August 30th and October 19th, 2020, by the Vox Pop Lab in Canada for TVNZ. The overall sample size was 175,000, with a Chinese sub-sample consisting of 3,235 respondents.

6. Notably, ethnicity information is not available in New Zealand’s election rolls. However, sampling the rolls based on the ethnic origins of names could potentially yield fairly reliable data (Park Citation2006). As a result, surveys of Chinese New Zealanders may yield varying outcomes while still reflecting an overall trend.

References

- 1 NEWS Colmar Brunton Poll. 2020. 1 NEWS Colmar Brunton Poll. https://static.colmarbrunton.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/8-12-Feb-20201-NEWS-Colmar-Brunton-Poll-report-.pdf.

- Baines, Paul R., Phil Harris, and Barbara R. Lewis. 2002. “The Political Marketing Planning Process: Improving Image and Message in Strategic Target Areas.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning 20 (1): 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500210414710.

- Banducci, Susan A, Todd Donovan, and Jeffrey A Karp. 2004. “Minority Representation, Empowerment, and Participation.” The Journal of Politics 66 (2): 534–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2004.00163.x.

- Barker, Fiona, and Kate McMillan. 2014. “Constituting the Democratic Public: New Zealand’s Extension of National Voting Rights to Non-Citizens.” New Zealand Journal of Public and International Law 12 (1): 61–80.

- Booth, Robert, and Rajeev Syal. 2019. “BAME Support for Corbyn Much Higher Than Overall Electorate.” The Guardian, December 4. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/dec/04/bame-support-for-jeremy-corbyn-much-higher-than-overall-electorate#:~:text=Black%20and%20ethnic%20minority%20voters,votes%20in%20crucial%20swing%20seats.

- Burton, Michael John, and Tasha Miracle. 2014. “The Emergence of Voters Targeting: Learning to Send the Right Message to the Right Voters.” In Political Marketing in the United States, edited by Jennifer Lees-Marshment, Brian Conley, and Kenneth Cosgrove, 26–43. New York: Routledge.

- Cain, Bruce E., D. Roderick Kiewiet, and Carole J. Uhlaner. 1991. “The Acquisition of Partisanship by Latinos and Asian Americans.” American Journal of Political Science 35 (2): 390–422. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111368.

- Calvert, Randall L. 1985. “Robustness of the Multidimensional Voting Model: Candidate Motivations, Uncertainty, and Convergence.” American Journal of Political Science 29 (1): 69–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111212.

- Chan, Tayden Fung, and Luna L. Zhao. 2023. “Beyond the Bipartisan System in the Taipei Mayoral Elections—Rise of Market-Oriented Strategies in Electoral Campaigns?” China Report 59 (1): 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/00094455231155329.

- Chappell, Henry W., and William R. Keech, 1986, “Policy Motivation and Party Differences in a Dynamic Spatial Model of Party Competition.” The American Political Science Review, 80(3), 881–899, https://doi.org/10.2307/1960543.

- Chen, Liu. 2020. “Poll Shows Large Majority of Chinese New Zealanders Still Favour National Over Labour.” RNZ, August 27. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/424544/poll-shows-large-majority-of-chinese-new-zealanders-still-favour-national-over-labour.

- Cheng, Derek. 2020. “National MP Jian Yang to Retire from Politics Following Election.” New Zealand Herald, July 10. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/national-mp-jian-yang-to-retire-from-politics-following-election/4K2OLLQA2PFANAKCAGLBXCLXQ4/.

- Chong, Dennis, and Dukhong Kim. 2006. “The Experiences and Effects of Economic Status Among Racial and Ethnic Minorities.” The American Political Science Review 100 (3): 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055406062228.

- Da Fonseca, Sara Claro. 2011. “New Citizens—New Candidates? Candidate Selection and the Mobilization of Immigrant Voters in German Elections.” In The Political Representation of Immigrants and Minorities: Voters, Parties and Parliaments in Liberal Democracies, edited by Karen Bird, Thomas Saalfeld, and Andreas M. Wüst, 109–127. London and New York: Routledge.

- Delacourt, Susan. 2016. Shopping for Votes: How Politicians Choose Us and We Choose Them. 2nd ed. Madeira Park, British Columbia, Canada: Douglas & McIntyre.

- Edwards, Bryce. 2009. “Party Strategy and the 2008 Election.” In Informing Voters?: Politics, Media and the New Zealand Election 2008, edited by Chris Rudd, Janine Hayward, and Geoffrey Craig, 13–32. North Shore, New Zealand: Pearson.

- Elaine, Sherman, Leon Schiffman, and Shawn T. Thelen. 2008. “Impact of Trust on Candidates, Branches of Government, and Media within the Context of the 2004 U.S. Presidential Election.” Journal of Political Marketing 7 (2): 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377850802053000.

- Elder, Edward. 2016. Marketing Leadership in Government: Communicating Responsiveness, Leadership and Credibility. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Elder, Edward, Lees-Marshment Jennifer, Usman Malik Salma, and Zhao. Luna. 2021. “Targeted Communication by Minor and Major Parties.” In Political Marketing and Management in the 2020 New Zealand General Election, edited by Edward Elder and Jennifer Lees-Marshment, 109–120. Cham, UK: Palgrave Macmilla.

- Electoral Commission. New Zealand Election Results. (dataset). https://archive.electionresults.govt.nz/.

- Electoral Commission. 2021. A More Diverse Parliament. https://elections.nz/democracy-in-nz/25-years-of-mmp/a-more-diverse-parliament/.

- Farrer, Benjamin David, and Joshua N. Zingher. 2018. “Explaining the Nomination of Ethnic Minority Candidates: How Party-Level Factors and District-Level Factors Interact.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 28 (4): 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2018.1425694.

- Fisher, David, and Matt Nippert. 2017. “Revealed: China’s Network of Influence in New Zealand” New Zealand Herald, September 20. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/revealed-chinas-network-of-influence-in-new-zealand/F36WPWYQPCFOPP6HOMTMOFNLZU/.

- Friesen, Wardlow. 2015. Asian Auckland: The Multiple Meanings of Diversity. New Zealand: Asia New Zealand Foundation. https://www.asianz.org.nz/assets/Uploads/Asian-Auckland-The-multiple-meanings-of-diversity.pdf.

- Hawkins, George. 2001. “Speech to the AM990 Radio Chinese.” Beehive. govt.nz, March 18. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/speech-am990-radio-chinese.

- Heath, Anthony Francis, Stephen D. Fisher, Gemma Rosenblatt, David Sanders, and Maria K. Sobolewska. 2013. The Political Integration of Ethnic Minorities in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hopgood, Sela Jane. 2020. “NZ Election Brings in Largest Pacific Caucus.” RNZ, October 19. https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/428650/nz-election-brings-in-largest-pacific-caucus.

- Huang, Jie. 2023. The power of habit and electoral participation of ethnic Chinese in New Zealand. PhD diss., Victoria University of Wellington. https://openaccess.wgtn.ac.nz/articles/thesis/The_power_of_habit_and_electoral_participation_of_ethnic_Chinese_in_New_Zealand/22261522.

- Kwak, Laura J. 2017. “Race, Apology, and the Conservative Ethnic Media Strategy: Representing Asian Canadians in the 2011 Federal Election Campaign.” Amerasia journal 43 (2): 79–98. https://doi.org/10.17953/aj.43.2.79-98.

- Landa, Janet, Michael Copeland, and Bernard Grofman. 1995. “Ethnic Voting Patterns: A Case Study of Metropolitan Toronto.” Political Geography 14 (5): 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/0962-6298(95)93405-8.

- Lees-Marshment, Jennifer. 2001. “The Product, Sales and Market-Oriented Party—How Labour Learnt to Market the Product, Not Just the Presentation.” European Journal of Marketing 35 (9/10): 1074–1084. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005959.

- Lees-Marshment, Jennifer. 2014. Political Marketing: Principles and Applications. London and New York: Routledge.

- Levine, Stephen. 2021. “Politics in a Pandemic: New Zealand’s 2020 Election.” In Politics in a Pandemic: Jacinda Ardern and New Zealand’s 2020 Election, edited by Stephen Levine, 33–70. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University of Wellington Press.

- Levi, Margaret, and Laura Stoker. 2000. “Political Trust and Trustworthiness.” Annual Review of Political Science 3 (1): 475–508. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.475.

- Lien, Pei-te. 2010. “Pre-Emigration Socialization, Transnational Ties, and Political Participation Across the Pacific: A Comparison Among Immigrants from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.” Journal of East Asia Studies 10:453–482. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1598240800003696.

- Lloyd, Jenny. 2005. “Square Peg, Round Hole? Can Marketing-Based Concepts Such as the ‘Product’and the ‘Marketing Mix’ Have a Useful Role in the Political Arena?” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 14 (1–2): 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1300/J054v14n01_03.

- Malpass, Luke. 2020. “Election 2020: ‘Fair Cop’—National’s Paul Goldsmith Admits to Accounting Mistake as Labour Points Out $4b Hole.” Stuff, September 20. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/122827807/election-2020-fair-cop–nationals-paul-goldsmith-admits-to-accounting-mistake-as-labour-points-out-4b-hole.

- Martin, Nicole S. 2019. “Ethnic Minority Voters in the UK 2015 General Election: A Breakthrough for the Conservative Party?” Electoral Studies 57:174–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2018.12.004.

- Marwah, Inder, Triadafilopoulous Phil, and White. Stephen. 2013. “Immigration, Citizenship, and Canada’s New Conservative Party.” In Conservatism in Canada, edited by David Rayside and Jim Farney, 95–119. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- McMillan, Kate, and Fiona Barker. 2021. “‘Ethnic’ Media and Election Campaigns: Chinese and Indian Media in New Zealand’s 2017 Election.” Australian Journal of Political Science 56 (2): 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2021.1884644.

- Nagel, Jack H. 1995. “New Zealand’s Novel Solution to the Problem of Minority Representation.” The Good Society 5 (2): 25–27.

- Newman, Bruce I. 1994. The Marketing of the President: Political Marketing as Campaign Strategy. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications.

- New Zealand Herald. 2020. “Election 2020: Labour Down and NZ First Up in Final Poll.” New Zealand Herald, October 16. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/election-2020-labour-down-and-nz-first-up-in-final-poll/RUAOVF45J256TSZTXT34TE6NDA/.

- New Zealand Parliament. 2021. The 2020 General Election and Referendums: Results, Analysis, and Demographics of the 53rd Parliament https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/library-research-papers/research-papers/the-2020-general-election-and-referendums-results-analysis-and-demographics-of-the-53rd-parliament/.

- O’Cass, Aron. 2001. “Political Marketing-An Investigation of the Political Marketing Concept and Political Market Orientation in Australian Politics.” European Journal of Marketing 35 (9/10): 1003–1025. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560110401938.

- Ormrod, Robert P. 2005. “A Conceptual Model of Political Market Orientation.” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 14 (1–2): 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1300/J054v14n01_04.

- O’Shaughnessy, Nicholas. 2001. “The Marketing of Political Marketing.” European Journal of Marketing 35 (9/10): 1047–1057. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560110401956.

- Park, Shee-Jeong 2006. Political Participation of ‘Asian’ New Zealanders: A Case Study of Ethnic Chinese and Korean New Zealanders. PhD diss., University of Auckland.

- Pietsch, Juliet. 2018. Race, Ethnicity, and the Participation Gap : Understanding Australia’s Political Complexion. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Ratcliff, Shaun, Sheppard Jill, and Pietsch. Juliet. 2020. “Voter Behaviour.” In Morrison’s Miracle: The 2019 Australian Federal Election, edited by Anika Gauja, Marian Sawer, and Marian Simms, 253–274. Canberra, Australia: ANU Press.

- RNZ. 2017. “China’s Influence Over New Zealand at ‘Critical Level’ - Academic.” RNZ, November 14. https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/new-zealand/2017/11/china-s-influence-over-new-zealand-at-critical-level-academic.html.

- RNZ. 2020. “Labour List MP Raymond Huo to Retire from Politics at Election.” RNZ, July 21. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/421677/labour-list-mp-raymond-huo-to-retire-from-politics-at-election.

- RNZ. 2021. “Red Line.” RNZ Podcast Audio, https://www.rnz.co.nz/programmes/red-line.

- Robinson, Claire. 2010. “Political Advertising and the Demonstration of Market Orientation.” European Journal of Marketing 44 (3/4): 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561011020525.

- Rosenbaum, Martin. 1997. From Sapbox to Soundbite: Party Political Campaigning in Britain Since 1945. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sanders, David, Anthony Heath, Stephen Fisher, and Maria Sobolewska. 2014. “The Calculus of Ethnic Minority Voting in Britain.” Political Studies 62 (2): 230–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12040.

- Scammell, Margaret. 1999. “Political Marketing: Lessons for Political Science.” Political Studies 47 (4): 718–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00228.

- Seabrook-Suckling, Lee. 2020. “Act Takes Chinese Voter Support from National.” Asia Media Centre, October 1. https://www.asiamediacentre.org.nz/news/act-takes-chinese-voter-support-from-national/?stage=Live.

- Skykiwi. 2015. “天维网专访新西兰工党党魁 andrew Little.” Skykiwi, February 10. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OF5cl3SNvZY&list=PL1iBq0Vma9o82kBfiJ7jnX7ywxOpae8V8&index=37.

- Skykiwi. 2017a. “为政治而生的新西兰美女-工党副党魁 Jacinda Ardern.” Skykiwi, March 19. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rV463KhqZIY&list=PL1iBq0Vma9o82kBfiJ7jnX7ywxOpae8V8&index=66.

- Skykiwi. 2017b. “新西兰天维网专访工党党魁 Jacinda Ardern.” Skykiwi, September 12. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zj0ZuKHn2T0&list=PL1iBq0Vma9o82kBfiJ7jnX7ywxOpae8V8&index=35.

- Skykiwi. 2020a. “Andrew Little Meet with the Chinese Community.” Skykiwi Talk Show, August 12. https://www.yizhibo.com/l/MaoFvKIlRkMn89vz.htm.

- Skykiwi. 2020b. “Budget 2020: The Finance Minster Meeting with the Chinese Community.” Skykiwi Talk Show, May 20. https://www.yizhibo.com/l/a9PEh5rxD1qeUtLL.html.

- Skykiwi. 2020c. “Ex-Pm John Key and Ex-Ceo of Air New Zealand Chris Luxon Analyse NZ Economy for the Chinese Community.” Skykiwi Talk Show, April 21. https://www.yizhibo.com/l/epwnZhyOVPUyNnSh.html.

- Skykiwi. 2020d. “Hon Stuart Nash and Raymond Huo Meet with the Chinese Community.” Skykiwi Talk Show, June 10. https://www.yizhibo.com/l/KRhZQU6oOdBNFTM5.html.

- Skykiwi. 2020e. “How Government Copes with the COVID Pandemic: Labour’s MP Raymond Huo Interview.” Skykiwi Talk Show, April 22. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7jHa2lU1q2k.

- Skykiwi. 2020f. “国家党独家透露 不排除再推出一位华人候选人.” Skykiwi, July 13. http://politics.skykiwi.com/special-column/election/2020-07-13/424733.shtml.

- Smith, Gareth, and Andy Hirst. 2001. “Strategic Political Segmentation—A New Approach for a New Era of Political Marketing.” European Journal of Marketing 35 (9/10): 1058–1073. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005958.

- Sobolewska, Maria. 2013. “Party Strategies and the Descriptive Representation of Ethnic Minorities: The 2010 British General Election.” West European Politics 36 (3): 615–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2013.773729.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2014. Non-Voters in 2008 and 2011 General Elections: Findings from New Zealand General Survey. https://www.stats.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Retirement-of-archive-website-project-files/Reports/Non-voters-in-2008-and-2011-general-elections/non-voters-2008-2011-gen-elections-31jan2014.pdf.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2019. New Zealand’s Population Reflects Growing Diversity. https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/new-zealands-population-reflects-growing-diversity.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2020. Ethnic Group Summaries Reveal New Zealand’s Multicultural Make-Up. https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/ethnic-group-summaries-reveal-new-zealands-multicultural-make-up/.

- Tan, Lincoln. 2014. “Migrants Told Voting Crucial Part of Adopting NZ as Home.” New Zealand Herald, August 27. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/migrants-told-voting-crucial-part-of-adopting-nz-as-home/XIZQIXN2KZYAN3GDIQNVPVWWJE/.

- Tan, Lincoln. 2017. “Poll: National Will Be Back in Government if Chinese Voters Had Their Way.” New Zealand Herald, September 11. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/poll-national-will-be-back-in-government-if-chinese-voters-had-their-way/JLBDFGD5HNV7F5BKP66KFDNHWA/.

- Taylor, Zack. 2021. “The Political Geography of Immigration: Party Competition for Immigrants’ Votes in Canada, 1997-2019.” The American Review of Canadian Studies 51 (1): 18–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/02722011.2021.1874732.

- Times Online. 2020. “Naisi Chen Launches Labour Campaign for Botany.” Times Online, July 28. https://www.times.co.nz/news/naisi-chen-launches-labour-campaign-for-botany/.

- Vowles, Jack, Fiona Barker, Mona Krewel, Janine Hayward, Jennifer Curtin, Lara Greaves, and Luke Oldfield. 2022. “Data From: 2020 New Zealand Election Study” (dataset). https://doi.org/10.2619/3BPAMYJ.

- Vowles, Jack, Hilde Coffé, and Jennifer C Curtin. 2017. A Bark but No Bite Inequality and the 2014 New Zealand General Election. Canberra, Australia: ANU Press.

- Walker, Peter. 2019. Labour to Launch Race and Faith Manifesto The Guardian, November 25. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/nov/25/labour-to-launch-race-and-faith-manifesto.

- Walls, Jason. 2020. “Election 2020: Judith Collins in ‘Bittersweet’ Campaign Launch, Attacks Labour as ‘Erratic’ and ‘Lazy’.” New Zealand Herald, September 20. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/election-2020-judith-collins-in-bittersweet-campaign-launch-attacks-labour-as-erratic-and-lazy/AC3W2IHWY37ZDNB5DJZTVZR47E/.

- Wass, Hanna, André Blais, Alexandre Morrin-Chasse, and Marjukka Weide. 2015. “Engaging Immigrants? Examining the Correlates of Electoral Participation Among Voters with Migration Backgrounds.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 25 (4): 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2015.1023203.

- White, Stephen E. 2017. “Canadian Ethnocultural Diversity and Federal Party Support: The Dynamics of Liberal Partisanship in Immigrant Communities.” Political Science & Politics 50 (3): 708–711. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517000464.

- Ziena, Jalil. 2021. “The COVID-19 Election: How Labour Turned a Crisis into Its Biggest Branding Opportunity.” In Political Marketing and Management in the 2020 New Zealand General Election, edited by Elder Edward and Lees-Marshment Jennifer, 35–46. Cham, Swizerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zingher, Joshua N, and M. Steen Thomas. 2012. “Patterns of Immigrant Political Behaviour in Australia: An Analysis of Immigrant Voting in Ethnic Context.” Australian Journal of Political Science 47 (3): 377–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2012.704000.