ABSTRACT

The Asian values thesis argues that a coherent value system endemic to Asian societies is incompatible with the Western notion of individual human rights and liberal democracy. Past survey studies have treated Asian values as a one-dimensional variable and left the meaning of democracy open to various interpretations. As a result, the precise loci of conflict between the two value systems were never fully fleshed out. This study addresses those shortfalls by breaking the concept of Asian values down into ‘Asian’ personal and political values and liberal democracy down to its defining characteristics: electoralism, political rights, and civil rights. Using country-level data from the Pew Research Centre and the World Values Survey, I examined how ‘Asian’ personal and political values are associated with these liberal democratic principles. Regression results reveal a wide intraregional disparity in ‘Asian’ values orientation within East and Southeast Asia and interregional effects suggest that the existence of a pan-Asian identity is greatly overstated. Whereas ‘Asian’ personal values are not inimical to liberal democratic principles, ‘Asian’ political values are negatively associated with the support for electoralism and political rights. This leaves countries in Asia open to the possibility of alternative political models to gain mass support.

1. Introduction

The Asian values debate dates back to a series of high-profile clashes between Asian thought leaders and Western scholars in the 1990s over the issues of human rights and democracy in Asia. The problem was first brought to the forefront on the international stage at the UN Human Rights Conference held in Vienna in 1993 where representatives from Singapore and China maintained that a unique Asian development model justified an alternative outlook to the liberal conception of rights and governance, one that was centred around harmony, stability, and material welfare. Their arguments were bolstered by the string of economic success in the region, most notably the rapid industrialisation and growth experienced by the four Asian tigers (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan). In response, Western scholars decried such policies as a veil for human rights abuse and accused Asian political leaders of weaponising cultural attachments to serve their political agendas. The exchanges continued throughout the 1990s until 1997 when it seemingly fizzled out after the Asian financial crisis eroded much of the credibility of the Asian development model.

Two decades after UN Human Rights Conference, the issues central to the Asian values debate are no closer to finding any common resolution. Today, the ascendency of China and the disillusion with Western democracies are revitalising the Asian values debate, leading to new conflicts couched in the language of cultural differences. After the Myanmar coup of 2021, ASEAN leaders stayed mostly silent, preferring to adopt the principle of ‘non-interference’, until very recently when the bloc issued a joint statement condemning the acts of violence at the 2023 ASEAN Summit after years of international criticisms aimed at the bloc’s muted response (Strangio Citation2023). In a damning report, the OHCHR (Citation2022) excoriated China’s counter-terrorism efforts as ‘deeply problematic from the perspective of international human rights norms and standards’ (p. 45). China for its part retorts with a 131-page report, insisting that far from suppressing minority rights, these measures were about ‘protecting the rights and interests of all ethnic groups’ (Information Office of the People’s Government of Xinjiang Citation2022). As debates over family structure and sexual identity spill over to Asia, it is not uncommon to hear politicians recast liberal perspectives on these issues as foreign imports that undermine local values (Ang Citation2021; Bernama Citation2019). Despite spirited discussions, the tension between putative Asian values and liberal democratic rights was never resolved and the debate over Asian values remains as germane today as it was 20 years ago.

There are two main difficulties surrounding the Asian values debate. First, most of these exchanges took place between the elites, either in politics or academia, acting as the supposed mouthpiece of the masses. Much ink has been spilt over whether Asian philosophical traditions are compatible with liberal democracy on a theoretical level. However, very little empirical research was done to show if these attachments were actually hostile to the support for liberal democracy at the grassroots level, even though the domain of mass norms and beliefs is crucial to the consolidation of democracies (Diamond Citation1999). Second, the few empirical studies done in the past did not break down liberal democracy into its constituent institutions and principles when measuring support for liberal democracy vis-à-vis support for Asian values. As a result, the precise loci of conflict between the two value systems were never fully fleshed out. In addition, these studies were often based on surveys done a long time ago and focused exclusively on Asian societies instead of the comparison between Asian and non-Asian societies.

This paper attempts to fill the gaps by adding timeliness and specificity, and by breaking down the understanding of liberal democracy into its constituent principles. We analysed the World Values Survey and Pew Research Survey conducted from 2017 onwards of societies from all over the world, focusing on two research questions fundamental to the Asian values argument: 1) Is there a coherent value system unique to East and Southeast Asian societies; and 2) if this has any influence on the support for liberal democracy as defined by its constituent principles. We hope that our findings can provide a more nuanced perspective that reflects the cultural diversity of East and Southeast Asia that goes beyond the binary East versus West paradigm.

2. Theoretical background

2.1 The asian values thesis

The Asian values debate first gained prominence during the Conference on Human Rights held in Vienna in 1993. Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore warned that forcing the democratisation of East Asian states would undermine their socio-economic interests and retard the developmental progress made by these countries. The Chinese foreign minister was more blunt in articulating the region’s position, asserting that ‘individuals must put the state’s rights before their own’ (Chong Citation2004). The concurrence among Asian countries was no accident. Three months before the conference, the Asia region was already preparing for the inevitable confrontation. In what is known as the Bangkok Declaration, delegates from 40 Asian countries pledged to respect the ‘national sovereignty, territorial integrity and non-interference in the internal affairs of States’ and recognised the ‘right to development’ as inalienable and fundamental as other political rights (UNESCO Citation1994). This distinctively Asian approach was further popularised by Lee in subsequent interviews where Lee ascribed the meteoric rise of East Asian states to values centred on the family and society, in stark contrast to the unfettered individualism espoused by the West (Zakaria and Yew Citation1994). Throughout the 1990s, several Singaporean and Malaysian officials also spoke out against ‘Western’ universalist claims about human rights and advocated for the ‘correct’ political arrangement (Emmerson Citation1995; Kausikan Citation1997; Mahbubani Citation1993). Although Singapore and Malaysia have been the most ardent supporters of this ideology, the message has since found resonance with other Asian countries including Indonesia, Thailand, Myanmar, Japan, and South Korea (Seifert Citation1998).

Unsurprisingly, the Asian values thesis was met with much opprobrium from scholars of both Western and Asian origins. Some have argued that human rights can be derived from and indeed be enhanced by Asian core values (Bary and Theodore Citation1998; Fukuyama Citation1995a; Lama Citation1999). Others regard ‘Asian values’ as too crude a measure to encapsulate the diversity of cultural traditions in large and heterogenous Asian populations (Sen Citation1997). Even within Confucianism, substantial differences in interpretation exist. For example, Fukuyama (Fukuyama Citation1995a) points out that deference to authority is more characteristic of Japanese Confucianism than Chinese Confucianism which stressed familism over all other social relations, including relations with state authorities. Hence, any attempt to integrate various strands of Asian philosophies into a single set of ideas is likely to be facile. The Asian values thesis was also heavily criticised as a pretext for authoritarian governments to strengthen their rule and deny citizens the basic political and civil rights they are due (Bauer and Bell Citation2005; Englehart Citation2000). Hoon (Tan Citation2012) pointed out that by essentializing and constructing an exceptional Asian identity, Asian leaders perpetuate the same Orient/Occident dichotomy used by cultural chauvinists to demonstrate Western superiority. Lastly, some questioned the fatalistic implication of the Asian values thesis, arguing that no cultural practice or values are ever static or inviolable (Lawson Citation1998).

Overall, the Asian values position hinges on two key assumptions. One, there is a perceptible cluster of values and attitudes among Asian countries that one may draw on to demonstrate Asian exceptionalism. Two, the adoption of these values is antithetical to the support for liberal democracy as defined by the West which ought to be rejected as the normative institutional arrangement in the Asian context. This paper contributes to the debate by testing both of these propositions through empirical analysis of survey data.

2.2 Theoretical perspectives

Multiple theoretical perspectives have been proposed to either support or refute the Asian values thesis. The following section outlines the key arguments that scholars have made on both sides of the debate to reach their respective conclusions on the Asian values issue.

Cultural particularists

Cultural particularists argue that while there is no single pan-Asian set of values, there is enough overlap among the personal and political values of East and Southeast Asian societies to denote an exceptional Asian identity that renders them incompatible with liberal democracies. The most common of these overlaps is communitarianism, the view that the obligations to the community and family supersede the rights of individuals. In classic liberal traditions, the ontological basis of human rights is the atomistic and disembodied individual, free to live according to one’s own reasons and motives independent of external forces or social communities. By contrast, Confucianism designates the family and the community rather than the individual as the basic building block of society (Muzaffar Citation1996; Zakaria and Yew Citation1994). They argue that a communitarian view of human existence better approximates empirical reality because nobody exists independently of a larger social environment. Humans are social and interdependent beings by nature (Barr Citation2000). Moreover, insofar as individuals are free to choose their actions and beliefs, their identity which shapes and grounds these choices is at the same time constituted by the social attachments to the communities around them (Sandel Citation1998; Taylor Citation1985). Although the Asian values discourse draws heavily from Confucianism, this emphasis on community and family is shared not just by Confucian East Asia but also by Islamic and Buddhist states of Southeast Asia (Mauzy Citation1997; Zakaria and Yew Citation1994). As Muzaffar (Citation1996) notes, ‘none of the major Asian philosophies regards the individual as the ultimate measure of all things’ (p. 4).

The particularist worldview challenges liberalism on two fronts. One, society is made up of hierarchical relationships as opposed to equal ones. Two, social responsibilities to the family and society are given precedence over individual rights; duties are valued over freedom. In Asia, interactions between family members are governed by strict hierarchical norms based on age and gender. The father is the undisputed decision-maker of the household and exercises total control over his family in his housekeeping because he is presumed to know best while children are expected to obey and respect their parents (Bell Citation1995). The ‘metaphor of the household provides the basis of proper codes of social and political behaviour’ and the state will be governed in the same manner as the family (Park and Chull Shin Citation2006). Filial piety in the household translates to general deference to authority and rulers, freely elected or not. In turn, the rulers will govern like a Junzi, a virtuous gentleman who put the interests of the people first and provide for their welfare through paternalistic interventions (Shin Citation2011). For Confucianists, there is no ontological basis for equal treatment and universalisation of rights. Instead, familial and societal obligations trump all other prior commitments including one’s freedom to choose. Thus, individual autonomy understood as freedom from interference was never a primary concern to the Confucianists (Li, 1997). To the extent that rights did exist, they were the sole prerogative of the state and are not inalienable as the liberals have suggested (Huntington Citation1991). In fact, duties and obligations have always existed in traditional Asian cultures while the concept of rights was only recently introduced by the West (Mauzy Citation1997). Paradoxically, the emphasis on preserving close personal ties resulted in a lack of rules for impersonal relations and heightened hostility to those outside of one’s immediate networks, both of which are inimical to the development of a pluralistic democracy (Pye Citation1999).

However, to avoid the charge of being overly sympathetic to dictatorships, most Asian particularists chose not to abandon the language of rights entirely in favour of reciprocal obligations; instead, they claimed that the economic and development rights of society should be prioritised before the political and civil rights of the individual (Bell Citation1995; Lee Citation1992; Rosemont Citation2004). This is the view popularised by the Singapore model. Rosemont (Citation2004) defended this view by explaining that people have an obligation to uplift the material welfare of others by virtue of their membership in those particular communities and this could not be achieved through a Western conception of rights based on the principle of non-interference and individual autonomy. As rights are grounded in promoting social relations rather than limiting government overreach, the aversion to authority so often found in Western human rights discourse was mostly absent in the East (Mauzy Citation1997). The 1993 United Nations Asia Regional Meeting on Human Rights in Bangkok was the clearest expression of the commitment to economic rights where the governments of 40 Asian countries adopted the ‘Bangkok Declaration’, affirming the ‘right to development’ as an ‘integral part of fundamental human rights’ (UNESCO Citation1994).

The upshot of having a different view of rights and obligations is a polity with a distinct ‘Asian’ character. Even with free and fair elections, an Asian democracy is likely to be ‘illiberal’ rather than liberal if it were to maintain an affinity with Asian philosophical traditions (Barr Citation2000; Tan Citation2012). Under an Asian ‘illiberal’ democracy, the state is founded on a non-neutral understanding of the common good. Instead of leaving individuals to pursue their own understanding of the good life, the government reserves the right to intervene in citizens’ private lives to turn a predetermined good into reality and this good is usually defined in economic or development terms (Bell Citation1995). The paternalistic state is borne out of the unique developmental experience of Asian countries in the late 20th century which is historically distinct from the liberal democracies of the West (Huntington Citation1991; Zakaria Citation1997). The economic imperative continues to dominate the political discourse on rights and democracy today. Asians’ commitment to and understanding of democracy are realised in substantive terms which rest on the government’s economic and political performance (Chu, Diamond, and Andrew Citation2010; Huang, Chu, and Chang Citation2013). For example, in Singapore, democracy is valued not for its inherent quality of giving voice to every individual but merely instrumentally for its ability to deliver economic goods (Chua Citation2017). These illiberal elements undermine the liberal universalist argument that with time, every country would gravitate towards liberal democracy as the ideal mode of government regardless of the sociocultural context.

Liberal Universalism

Liberal universalists believe that liberal ideas about rights and democracy are not only compatible with Asian values but should be actively promoted within Asia. Subramaniam (Citation2000) identified three major arguments that made the case for compatibility. First, the political and cultural liberties guaranteed under a liberal democracy transcend cultural boundaries. The authoritarian threat to these basic human liberties is no less real in Asia than in the West. Any pretensions about the merits of a paternalistic government amounted to an excuse for human rights abuses (Englehart Citation2000; Kim Citation1994; Tan Citation2012). ‘Classic individual freedoms’ must be acknowledged universally even at the risk of being accused of Eurocentrism (Langguth Citation2003, 41). Second, Asian civilisations have liberal heritages often ignored by proponents of the Asian values argument. Choice and freedom are recurrent themes in Buddhism, a school of thought that is highly influential in informing cultural attitudes in different parts of Asia (Fukuyama Citation1997; Lama Citation1999). The early teachings of Confucianism stressed the importance of self-cultivation and moral autonomy; Confucianism only took on a more authoritarian character after the Legalists reform during the Qin dynasty (Shin Citation2011). Third, universalists argue that cultural practices, beliefs, and attitudes are amenable to change and that culture is in fact not destiny (Kim Citation1994; Zakaria and Yew Citation1994). Some universalists make the stronger claim that all societies will eventually converge upon Western liberal democracy (Fukuyama Citation1989).

A form of universalistic theory that made this claim is modernisation theory which traces back to Lipset (Citation1959), the first scholar to establish the link between the level of development and the level of democratisation within a country. He argued that economic development, a function of industrialisation, urbanisation, wealth, and education, is the precondition for democratisation to take place. Although hotly contested, the discussion was mostly confined to a small academic circle. However, the theory enjoyed a resurgence in popularity after the collapse of the Soviet Union when Fukuyama (Citation1989) made his controversial assertion, that humanity has reached the ‘end of history as such: that is, the end-point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalisation of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government’ (p. 4). Fukuyama (Fukuyama Citation1989) disputed the notion that liberal ideology and institutions inexorably corrode the current civil society and culture when in fact, ‘liberalism based on individual rights is quite compatible with strong, communitarian social structures’ (p. 13). The empirical observation that many Asian communities exist in liberal democracies such as the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States while remaining true to their cultural roots suggests that Asian values are not fundamentally hostile to Western democracies (Fukuyama Citation1997).

Building on the modernisation theory, Inglehart and Welzel (Citation2003) presented a more integrated framework, the ‘human development thesis’ where ‘human development’ refers to the ability of human beings to choose the lives they want. ‘human development’ hinges on three factors, socioeconomic development, rising emancipative values, and effective democracy, each of which leads to ‘human development’ via a separate pathway. Socioeconomic development contributes to human development by raising levels of education and access to information thereby increasing people’s capabilities to exercise freedom. Emancipative values elevate people’s desire to exercise freedoms and democratic institutions empower people legally to exercise those freedoms. The three factors interact according to the ‘utility logic of freedom’ (p. 6). Socioeconomic development results in a rise in emancipative values and this in turn encourage the endorsement of liberal democracy. Asian societies are not exempt from this ‘utility logic of freedom’ and the ‘human development thesis’ directly challenges the Asian exceptionalism narrative pushed by cultural particularists (Welzel Citation2011).

Other perspectives

Many scholars do not fall neatly into the particularists or universalists camp. Some have adopted a pluralistic approach to the Asian values dilemma. Parekh (Citation1992) argued that there are indeed universal principles of good governments but these might not be liberal in form and cannot be prescribed by Western governments alone. To gain legitimacy in the eyes of the international community, these principles ‘have to be freely negotiated by all involved and grounded in a broad global consensus’ (p. 173). Similarly, Lawson (Citation1998) criticised the prescription of either an ‘illiberal’ or ‘liberal’ democracy for Asian societies as being equally fatalistic and problematic. Culture is not destiny because it is not static. There is scope for people to periodically revise and champion a form of government that is most congruent with the prevailing cultural values, whether they are individualistic or collectivist in orientation. The cross-cultural debate over human rights is coloured by compatibilist scholars who believed that Confucianism is reconcilable with individual human rights. Confucian communitarians have argued that individuals embedded in social relations still have certain rights but stop short of endorsing the liberal conception of negative rights (Bary and Theodore Citation1998; Chan Citation2002; Tan Citation2012). In recent years, Confucian scholars also began to recognise the diversity and complexity of Asia as real obstacles to comprehensive moral doctrines such as classical Confucianism and propose reformulations of Confucianism that are more accommodating to pluralistic societies (Kim Citation2012; Weber Citation2015; Ziliotti Citation2020).

Others have focused their efforts on designing the best political and institutional arrangement for a Confucian society while acknowledging the importance of democratic legitimacy. Confucian meritocrats maintain that political leaders chosen on the basis of competence and virtue are better equipped to deal with problems in complex societies but democratically elected leaders grant the regime legitimacy. Therefore, they advocate for a hybrid bicameral legislature composed of a democratically elected lower house to express the popular will and a meritocratic ‘Confucian’ upper house where real decision-making power resides (Bai, 2020; Bell Citation2006; Huang, Chu, and Chang Citation2013). More recently, Bell (Citation2015) has moved away from his bicameral proposition in favour of a vertical democratic meritocracy, political meritocracy at the top (central government) and democracy at the bottom (provincial/local government), as the best way to reconcile political meritocracy and electoral democracy in large countries. Bell’s reason for the departure was that such a hybrid regime would not be consolidated because power will inevitably be wrestled away from the meritocratic chamber as long as some political leaders are chosen on the basis of one person, one vote. The perspectives highlighted here are not exhaustive of the full range of discussion on the Asian values debate but they should be enough to contextualise our analysis later on.

2.3 Delineating “liberal” democracy

The road to liberal democracy was fraught with fervent intellectual contestation. In his seminal work, Dahl (Citation1971) laid out eight institutional guarantees necessary for any regime to be considered a democracy. By contrast, scholars such as Schumpeter (Citation1976) and Huntington (Citation1993) measured democracy in minimalist terms; a political system where ‘its most powerful collective decision makers are selected through fair, honest, and periodic elections in which candidates freely compete for votes’ (Huntington Citation1993, 7). However, electoralism as a sufficient condition came under intense scrutiny with the proliferation of hybrid regimes, regimes that possessed the veneer of democratic rule by holding regular elections and yet routinely violate rules that legitimised political authority (Levitsky and Way Citation2002). In a bid to disentangle the semantic mire, many have argued that ‘liberal democracy’ should be differentiated from ‘electoral democracy’ in that the former goes beyond the minimalistic definition and even Dahl’s polyarchy, to include the requisite political and civil rights that make those elections ‘meaningful’ (Diamond Citation1999; Merkel Citation2004; Munck Citation2009). This dichotomy between the two types of democracy is now generally accepted by modern taxonomies of regime types (Diamond Citation2002; Lührmann, Tannenberg, and Lindberg Citation2018; Philip and Howard Citation2009; Schedler Citation2015)

Liberal democracy was the result of an unlikely marriage between two independent, potentially conflicting ideas, democracy and liberalism. A democracy recalls to mind a government that listens to the people or as Dahl (Citation1971) puts it ‘the continuing responsiveness of the government to the preferences of its citizens’ (p. 1). Free and fair elections as an institutional guarantee is the most basic requirement of this form of government. Political rights are the preconditions that enable the articulation of disparate individual and/or collective preferences in a pluralistic society and to have those preferences given equal consideration in the formulation of public policy (Dahl Citation1971, 2). To achieve these ends, freedom of expression and association is paramount. However, to live up to its full name, liberal democracy must grant legal protection to civil rights in addition to political rights (Mukand and Rodrik Citation2020). Civil rights as negative freedom shield individuals or groups of individuals from the ‘tyranny of the majority’ by upholding inalienable basic liberties that precede majoritarian decisions (Jefferson Citation1776; Mill, Mark Philp, and Mill Citation2015; Tocqueville et al. Citation2002). In other words, fundamental rights provide the antidote to the worst excesses of an unbridled democracy where oppression of the minority is to be expected. Though there has been much debate about what these individual rights should be, the basic idea is that we should be free to conduct our private affairs without unjustifiable intrusion from the state or other individuals (United Nations Citation1948). As these rights are guaranteed under the legal system, equal treatment before the law is part and parcel of the civil rights package (Merkel Citation2004). A better understanding of the constitutive elements of a liberal democracy allows us to better operationalise its support in the empirical analysis.

2.4 Past empirical studies

Much of the discussion available stems from theoretical disagreements, and there are only a handful of studies that have tested the relationship between Asian values and support for democracy empirically. Broadly speaking, these studies have tried to answer two interrelated queries: 1) if there is indeed a coherent value system unique to East and Southeast Asian societies; and 2) if this has any influence on the support for liberal democracy.

Only two of the previous studies have been able to generate insights into the first query. Through analysing World Values Survey data, Dalton and Ong (Citation2005) found that acceptance of authority was not markedly different for East Asian countries compared to Western democracies. The citizens of East Asian countries also differed significantly in their interpretation of Confucianism vis-à-vis their attitudes towards the family and authority. Welzel (Citation2011) reached similar conclusions using a newer wave of the World Values Survey. He argued that the differences in emancipative values and liberal notions of democracy between countries were gradual rather than categorical, refuting the assumption of a uniquely Asian cultural tradition.

On the second query, a few of the studies did find a negative association between Asian values and support for democracy in East Asian societies by using Asian Barometer Survey (Chang, Chu, and Tsai Citation2005; Nathan Citation2007). Park and Shin (Park and Chull Shin Citation2006) found that Confucian values of hierarchical collectivism, anti-pluralism and family state were associated with authoritarian sympathies. Using more recent data from the same survey, Zhai (Citation2017) found that Confucian values in both the political and non-political spheres had a negative effect on the adherence to liberal democratic values in China. On the flip side, Dalton and Ong (Citation2005) and Sing (Citation2012) found no statistically significant relationship between the dimensions of Asian values and support for democracy. Shen and Tsui (Citation2018) found no obvious relationship between Asian values and support for freedom of expression at the country level and an unexpected positive relationship between Asian values and support for freedom of expression at the individual level. Zhai (Citation2022) concludes that traditional family and social values are not incompatible with the support for liberal democracy but the political Asian values did decrease the preference for democracy. Although traditional family and social values remain popular in China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, the last three have become detached from Asian values in the political sphere, leaving China as the only one that still upholds authoritarian political values.

Valuable as these studies are, they suffer from three major limitations. First, except for Shen and Tsui (Citation2018) and Zhai (Citation2022), all empirical studies were done using survey data that were at least a decade old, calling the current relevance of their findings into question. Of the two studies, only Zhai (Citation2022) made a distinction between ‘Asian’ personal and political values, both of which have altered, in unique ways, with time. Therefore, new studies are needed to assess the commensurability of Asian values with support for liberal democracy in contemporary times.

Second, only Dalton and Ong (Citation2005) and Welzel (Citation2011) have made comparisons between Western and Asian countries, while the other studies have confined their analysis to Asia. Although the Asian Barometer Survey could provide invaluable insights into the preponderance of Asian values in Asian societies, a robust examination of the Asian exceptionalism premise cannot be made without contrasting the cultural attitudes of Asian societies with the West. Beyond the East/West dichotomy, we are also interested in how prevalent Asian values are in other parts of the world, in societies with vastly different cultural traditions and regime types.

Third, other than Welzel (Citation2011) which included different notions of democracy and Shen and Tsui (Citation2018) which tested people’s support for freedom of speech, these studies measured the support for democracy without defining and breaking democracy down into its constituent components. This makes cross-sectional comparisons difficult as an average citizen’s understanding of democracy diverges greatly across nations (Chu, Diamond, and Andrew Citation2010; Shin Citation2017). Another difficulty is that people might have conflated their support for certain democratic norms with their evaluation of democratic performance in their home country and people are generally more pessimistic about the latter (Richard et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, we do not know which specific rights or institutions under a liberal democracy are prone to cultural influence, making any cross-cultural dialogue between the East and the West almost impossible.

This study aims to plug these gaps by analysing survey data from 2017 onwards across geographical regions, measuring the effect of ‘Asian’ personal and political values on specific liberal democratic principles, grouped under electoralism, political rights or civil rights at the country level. In this study, we would expect a neat Southeast & East Asia/West regional divide of cultural values to be non-existent. In fact, Asian values may be a misnomer as we expect societies all across the world to adopt varying degrees of ‘Asian’ personal and political values. We also believe that support for liberal democratic principles is widely accepted and they would not vary with the level of attachment to ‘Asian’ personal values. However, as discussed in the theoretical frameworks, many scholars believe that a different attitude on governance orients Asian societies towards an illiberal democracy, hence we might find a negative association between ‘Asian’ political values and civil rights but we do not believe this relationship will bear out for electoralism and political rights.

3. Data and measurements

3.1 Data description

The two research questions were investigated by analysing the data provided by the Wave 7 World Values Survey (WVS) and the Pew Research Centre Global Attitudes Survey 2019 (PRS). WVS comes from the 7th wave which was launched in January 2017 and completed in December 2022 with a total of 64 countries surveyed (World Values Survey Citationn.d..). The PRS was a survey conducted by Pew Research Center from May 2019 to October 2019 that focused on democratic rights and satisfaction in 34 countries (Wike and Schumacher Citation2020). For both surveys, all the questions were standardised and translated into the national language of the respective countries. The data was collected using representative sampling techniques depending on the specific conditions in the country surveyed with a sample size of at least 1000 per country. The WVS offered the information necessary to answer the first question regarding the preponderance of ‘Asian’ personal and political attitudes across different societies while linking the data from WVS and PRS allowed us to answer the second question, the influence of ‘Asian’ values on the support for liberal democracy.

3.2 Sample construction

To juxtapose the preponderance of ‘Asian’ values in East and Southeast Asia with the rest of the world, it was first necessary to arrange the 62 countries into various geographical regions (Egypt was excluded from the analysis as Q198 (Paternalism dimension) was not asked in the WVS). (Nijman et al., 2020). As the WVS surveyed Great Britain and Northern Ireland separately, the scores from these two regions were averaged to form the score for United Kingdom which is needed for comparison with the data from PRS.

North America: Canada, United States

Latin America: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Peru, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Uruguay, Venezuela

Europe: Andorra, Czechia, Germany, Greece, Netherlands, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Ukraine, United Kingdom

Middle East & North Africa: Cyprus, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, Turkey

Sub-Saharan Africa: Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Zimbabwe

Russia & Central Asia: Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan

South Asia: Bangladesh, Maldives, Pakistan

East Asia: China, Hong Kong, Japan, Macao, Mongolia, South Korea, Taiwan

Southeast Asia: Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam

Oceania: Australia, New Zealand

The 10-fold grouping of countries was used to determine if the prevalence of ‘Asian’ values varies by region and if there is indeed a clustering of such values among East and Southeast Asian countries. The grouping further differentiates between East Asia and Southeast Asia countries, adjusting for the vast diversity between the Sino-Japanese and Southeast Asian macro cultures (Omondi Citation2017).

To investigate the second question of the effect of ‘Asian’ values on support for liberal democracy, the same geographical regions were kept. However, the sample size was restricted to the 23 countries which were surveyed in both the WVS and PRS.

North America: Canada, United States

Latin America: Argentina, Brazil, Mexico

Europe: Czechia, Germany, Greece, Netherlands, Slovakia, Ukraine, United Kingdom

Middle East & North Africa: Lebanon, Tunisia, Turkey

Sub-saharan Africa: Kenya, Nigeria

Russia & Central Asia: Russia

South Asia: N.A

East Asia: Japan, South Korea

Southeast Asia: Indonesia, Philippines

Oceania: Australia

3.3 Measurement of variables

The parameters selected to represent ‘Asian’ values were kept as broad as possible to encompass both East Asian and Southeast Asian cultures. However, the responses towards specific social issues, such as the patriarchy, abortion, homosexuality, etc., were left out because these positions are not necessarily tied to the core values integral to ‘Asian’ cultures as discussed in section 2.2. Conservatism on these issues could easily be found in other parts of the world and would not be apposite in formulating the unique Asian perspective. This paper replicated the past approach of distinguishing between personal values and political values (Chang, Chu, and Tsai Citation2005; Park and Chull Shin Citation2006; Zhai Citation2022).

“Asian” personal values

Under personal values, certain themes were assumed to be commonplace across Asia. To measure the different facets of ‘Asian’ personal values, I have divided the questions into three pairs, each measuring a distinct dimension: 1) Deference to Authority, 2) Familism, and 3) Duty to Society (see ). Deference to authority was measured by soliciting the respondent’s opinion on having ‘greater respect for authority’, whether it was 1 ‘Good’, 2 ‘Don’t mind’, or 3 ‘Bad’. The second question measured this dimension by asking the respondents to select up to five qualities among a list of 11 that children should be encouraged to learn at home. To measure familism, respondents were asked to state the extent to which they agreed with the following statements: ‘One of my main goals in life has been to make my parents proud’ and ‘Adult children have the duty to provide long-term care for their parents’. Duty to society was measured by asking respondents if they agree or disagree with the following statements: ‘It is a duty towards society to have children’ and ‘Work is a duty towards society’. All six questions were recoded from their original scales to take on the values of 0 or 0.5 (see ) so that within each of the three dimensions, the sum of the scores ranges from 0 to 1. An ‘Asian’ personal values index (ranging from 0 to 3) was constructed by summing the binary scores of the three dimensions together. A higher value on the index indicated a higher attachment to ‘Asian’ personal values.

“Asian” political values

Most Asian societies expected their government to rule with kindness and competence and bring about stability and economic prosperity. Therefore, the ‘Asian’ political values were measured in three dimensions, 1) benevolent government, 2) stability, and 3) paternalism. A benevolent government was measured by asking respondents if the ‘government should take more responsibility to ensure that everyone is provided for’ or if ‘people should take more responsibility to provide for themselves’ on a 10-point scale with 1 corresponding to full agreement with the former statement and 10 corresponding to full agreement with the latter. Stability was measured by the question: ‘Most people consider both freedom and security to be important, but if you had to choose between them, which one would you consider more important?’. Paternalism was measured by asking the participants if the government had the right to ‘collect information about anyone living in this country without their knowledge’. Those who answered ‘yes’ were assumed to believe that the government would use the information for their own good. All three questions were recoded from their original scales to binary variables of 0 or 1 (see ) and the scores were added to create the ‘Asian’ political values index (0–3). A higher value on the index indicated a higher attachment to ‘Asian’ political values.

Support for liberal democracy

Following the previous discussion, liberal democracy has three features, 1) electoralism, 2) political rights, and 3) civil rights. This paper broke down support for liberal democracy using a series of nine questions that corresponded to the three features; attitudes towards regular and competitive elections, freedom of operation for opposition parties (electoralism), freedom of operation for human rights organisations, freedom in media, freedom of speech, freedom on the internet (political rights), religious freedom, gender equality, and judicial fairness (civil rights). Each question represented a distinct democratic principle to circumvent the lack of a coherent and consistent definition of ‘democracy’ in previous survey studies. Responses were coded on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 ‘Very important’ to 4 ‘Not important at all’ (see ). The scores of these questions were reversed and summed to create the electoralism index, political rights index and civil rights index. The scores to all nine questions were also added to formulate the liberal democracy index, a proxy for people’s degree of support for liberal democracy. A higher value on the index indicated a higher support for liberal democracy.

Control variables

The multivariate analysis of attachment to ‘Asian’ values and support for liberal democracy at the country level controlled for each country’s age distribution (old-age dependency ratio), gender structure (female ratio), education level (average years of schooling), GDP per capita, and the level of existing institutional freedom (Freedom house scores).

3.4 Analytical strategy

We derived country-level data by calculating the mean responses of individuals in each of the sample countries. In section one, linear regressions were used to examine whether there were regional differences in ‘Asian’ values. Three ordinary least squares models were estimated for ‘Asian’ overall values, ‘Asian’ personal values, and ‘Asian’ political values, respectively, controlling for region dummies (with East Asia or Southeast Asia as the reference group) and country-level socio-demographic covariates. In the second section, to examine the association between ‘Asian’ values and support for liberal democracy, three models were estimated for electorialism, political rights, and civil rights, respectively, using the 19 sample countries present in both surveys. All models adjusted for country-level socio-demographic characteristics.

4. Findings

4.1 Distribution of “Asian” values by geographical regions

This section examined the homogeneity of Asian societies in two ways. First, we wanted to find out if there was intraregional consistency in the values exhibited by the different countries within East and Southeast Asia. Second, if there was a statistically significant difference in the ‘Asian’ values measured between East/Southeast Asia and other regions.

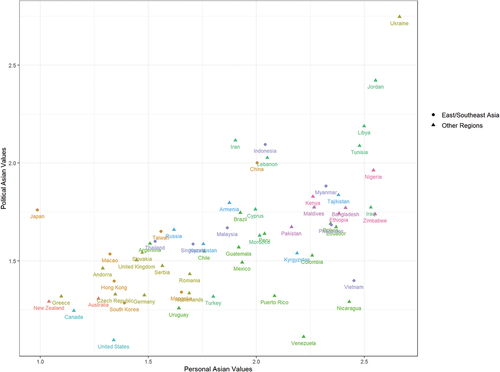

As expected, the societal distribution of both ‘Asian’ personal and political values spans almost the entire spectrum (). Liberal democracies in North America and Oceania possessed the lowest ‘Asian’ personal and political values score with relatively high intraregional consistency. Regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa and Europe also exhibited clustering of cultural attitudes while others have a much more varied distribution. Ironically, the East Asian region and Southeast Asian region displayed some of the highest intraregional discrepancies. In East Asia, Japan ranked exceptionally low on personal ‘Asian’ values. On the flip side, China ranked significantly higher on both political and personal values than other East Asian countries. Other East Asian countries do have similar personal and political values scores as shown in .

In Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Myanmar, and the Philippines scored much higher on both personal and political ‘Asian’ values than Thailand, Singapore, and Malaysia. Meanwhile, Vietnam had a high personal values score but a relatively low political values score (). Granted, the intraregional disparity was not exclusive to East and Southeast Asia; regions with a larger sample size generally showed a wider distribution. However, from this preliminary analysis, three trends were observed. One, the preponderance of ‘Asian’ values in East and Southeast Asia has been highly overstated. Other countries in the Middle East & North Africa or Sub-Saharan Africa possessed much higher ‘Asian’ personal and political value scores. Two, Asian countries which had been assumed to exist within the same cultural sphere can possess vastly different personal and political value orientations. Three, personal values were not always coterminous with political values. A country may have a high personal values score and low political values score (Vietnam) or vice versa (Japan).

We investigated the interregional difference in values attachment between East Asia and other regions using a linear regression model, incorporating regional dummy variables, societal age (old-age dependency ratio), gender (female ratio), education (average years of schooling), and wealth (GDP per capita) as controls. The results are tabulated in . Model 1 tested for the effect on the overall Asian values index weighted equally between personal and political values, while models 2 and 3 tested the effect of geographical regions on personal and political ‘Asian’ values respectively.

Table 1. Regression of Asian values with East Asia as base.

In model 1, regional effects were significant for some of the pairings. Adoption of overall Asian values was lower in North America (b = −0.586, p < 0.05) and Oceania (b = −0.640, p < 0.05) than in East Asia. Conversely, Middle East & North Africa (b = 0.602, p < 0.01) and Sub-Saharan Africa (b = 0.592, p < 0.05) had a higher Asian value score than East Asia. When looking at personal and political values specifically, the picture becomes more complicated. In model 2, Oceania was still lower than East Asia in Asian personal values but Latin America (b = 0.276), Middle East & Africa (b = 0.371) and Sub-Saharan Africa (b = 0.479) all had higher Asian personal values at the 0.05 significance level. In model 3, significant regional differences in Asian political values were found in North America (b = −0.417, p < 0.05) only.

We replicated the models with Southeast Asia as the base (). Similar to the previous case, North America (b = −0.885, p < 0.01) and Oceania (b = −0.939, p < 0.01) had lower Asian overall values compared to Southeast Asia. However, the higher values in Middle East & Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa found previously were not significant here. In models 2 and 3, the negative regional effect of North America (b = −0.442, p < 0.05; b = −0.459, p < 0.05) remained significant for both personal and political values and for Oceania (b = −0.601, p < 0.01), only the effect on personal values was significant. Overall, the significance of the regional effect varied according to the specific pairing of regions and the values examined.

Table 2. Regression of Asian values with Southeast Asia as base.

For model 1, the control variables did not have a significant effect on the adoption of ‘Asian’ values except for GDP (b = −0.008, p < 0.05) and for age (b = −0.016, p < 0.05) Although the relationship was expected, the negative association was small. Every $10,000 increase in GDP per capita only resulted in a 0.08 decrease in the ‘Asian’ values index and every 10% increase in old age dependency ratio led to a 0.16 decrease in the ‘Asian’ values index. In model 2, age (b = −0.017, p < 0.01) along with GDP (b = −0.005, p < 0.05) both had significant and negative effects on ‘Asian’ personal values. By contrast, none of the control variables in model 3 was significantly associated with ‘Asian’ political values.

4.2 Relationship between “Asian” values and support for liberal democracy

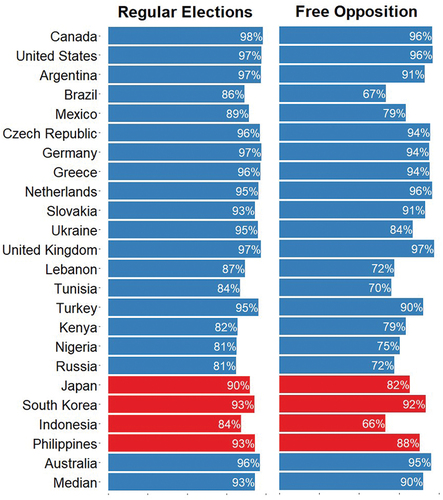

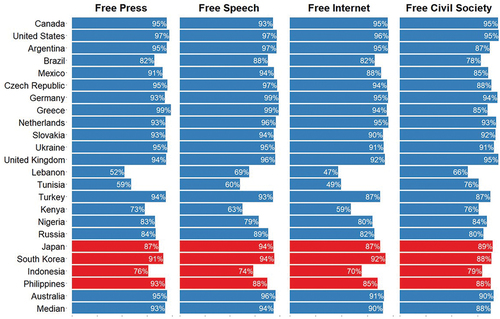

This section examines the question of whether support for liberal democracy varies with the degree of attachment to ‘Asian’ personal and/or political values. Generally, liberal democratic rights and institutions received strong support across all 19 countries. More than 80% of the respondents in all countries believed that having regular elections with at least two political parties was somewhat or very important to them (see ). Support for opposition parties to operate freely was still strong in most countries but declined considerably in Brazil and Indonesia.

The four questions for political rights revealed where the sharpest division in attitudes was found (see ). Support for the free press, speech, and internet was far lower in Lebanon, Tunisia, and Kenya as compared to other countries. Also worthy of note was Indonesia, whose support ranged from low to high seventies. In contrast, the strong support for freedom of expression in other countries was evinced by the high median of 93%, 94%, and 90%, respectively. Overall, respondents supported freedom of speech and freedom in media but were more reserved in their attitudes about censorship on the internet. When it comes to civil society, more than 70% of the respondents in all countries except Lebanon thought that human rights organisations should be able to operate freely without state intervention.

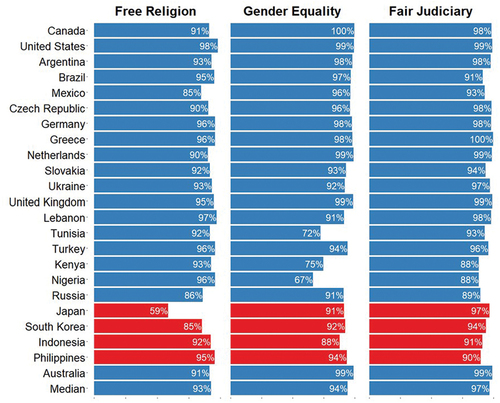

Respondents in most countries were strongly supportive of civil rights (see ). With the notable exception of Japan, strong majorities in every country said that it was somewhat or very important to allow people to practise their religion freely. For gender equality, strong support was seen in all countries other than Tunisia, Kenya, and Nigeria. Lastly, a fair judiciary was seen as important by the vast majority of the population in all countries. Apart from Indonesian’s attitude towards freedom of expression and freedom of opposition parties to operate, citizens of other East and Southeast Asia countries were not markedly unsupportive of liberal democratic principles.

As we have seen in section 1, a stronger attachment to ‘Asian’ values may be found in non-Asian societies. We used a linear regression model to test the effect of ‘Asian’ personal and political values on the support of liberal democracy across countries of all geographical regions, retaining the same set of demographic controls plus a new control variable, Freedom (Freedom house scores) to account for the effect of existing institutions. ‘Asian’ personal values had no statistically significant effect on the support for liberal democracy although we did find a weak, non-significant negative relationship between ‘Asian’ personal values and the liberal democratic index (). On the other hand, ‘Asian’ political values (b = −6.266, p < 0.01) were negatively associated with the support for liberal democracy. The magnitude of change was sizeable as a 1-point increase in the ‘Asian’ political values index translated to a 6.3-point decrease in the liberal democratic index. This effect was primarily driven by the association with political rights (b = −4.124, p < 0.001) and to a smaller extent, electoralism (β = −1.554, p < 0.01). Notably, there was no significant association between ‘Asian’ political values and civil rights and none of the control variables was statistically significant.

Table 3. Regression of support for liberal democracy.

None of the control variables was significantly associated with the support for liberal democracy, suggesting that the societal level of support for these liberal democratic principles was not influenced by demographic trends or existing institutional freedoms. We also investigated the interactional effects of ‘Asian’ personal and political values. In (Appendix), we added an interactional term to the linear regression and it had no significant effect on the support for liberal democratic principles. These results indicate that ‘Asian’ personal and political values were independent predictors for the support of liberal democracy.

5. Discussion and conclusion

This study assessed the two claims made in the Asian Values thesis. One, there is a uniquely ‘Asian’ value system that corresponds to a preponderance of certain cultural attitudes among East and Southeast Asian societies. Two, this ‘Asian’ value system undermined the support for liberal democracy as defined by liberal democratic principles. We will examine each of these propositions in turn.

5.1 Asian Exceptionalism

The proposition of Asian exceptionalism received very weak support through our analysis. The supposed intraregional clustering of ‘Asian’ values was found not in East and Southeast Asia but in other regions. Ironically, the countries of East and Southeast Asia regions exhibited a wide disparity in personal and political values distribution. Japan, Vietnam, and China were all extreme outliers in their respective regions and the clustering effect was observed for two to three countries at best but never the entire Asian region. ‘Asian’ personal and political values need not go together and quite a few countries fell on the extreme end of one continuum. None of these observations was particularly surprising. Cultural heterogeneity in Asia was well-recognised. In defining ‘Asian’ values, it is all too easy to accentuate Confucianism at the expense of other major philosophies such as Shintoism, Buddhism, and Islam which coincide with local customs in distinct and complex ways (Sen Citation1997). Even Confucianism manifests itself very differently from one country to another (Fukuyama Citation1997). The diversity of Asian cultures undermines any attempts to over-generalise ‘Asian’ systems of thought.

This brings us to the next major observation. There was little to no support for a quintessential Asian value system that was differentiated from the rest of the world as implied by cultural particularists. The linear regression of ‘Asian’ values showed that the regionality effect was only observed in a small number of regional pairings and for specific dimensions of ‘Asian’ values. For example, we can conclude that Southeast Asia had higher ‘Asian’ political and personal values than North America but we cannot say the same about East Asia. The neat East-West divide in cultural beliefs was not always found even if we limit our comparisons to characteristic Western democracies in North America and Oceania. Once we begin to broaden our comparisons, the contention that ‘Asian’ values are unique to Asian societies was categorically false. For the majority of the pairings, the difference in attachments to ‘Asian’ personal or political values between the regions was not significant. Interestingly, Latin America, Middle East & North Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa all had higher ‘Asian’ personal values than East Asia. These findings remind us that respecting authority, caring for one’s family and having a sense of duty to society are sentiments shared by many cultures in different parts of the world. The ontological starting point of defining the individual in communal terms is not alien to Middle Eastern and African societies (Parekh Citation1992). We should not fall into the trap of ‘essentializ[ing] their [Asian] cultural differences in stereotypes and dichotomies’ as this represents a ‘paradoxical reversal of Orientalism’ which has fuelled cultural chauvinism during the colonial period (Tan Citation2012, 162). That is not to say that there are no appreciable differences in the cultural beliefs of East and Southeast Asia vis-à-vis the rest of the world. Rather, it would be more fruitful to make these comparisons on the country level as the existence of a pan-Asian identity was greatly overstated by the cultural particularists.

5.2 “Asian” values and support for liberal democracy

Support for liberal democratic principles was strong across the board. With few exceptions, the proportion of people who indicated support for electoralism, political rights, and civil rights generally exceeds 70% of the sampled population. In three of the Asian societies observed, Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines, support for all three aspects of liberal democracy was on par with the median support. Although support for freedom of opposition and freedom of expression (media, speech, and internet freedom) was noticeably lower than the median in Indonesia, they were still supported by the majority. Despite frustrations with how democracy functions in their home country, most people were still committed to liberal democratic principles (Wike and Schumacher Citation2020). It is important to distinguish between people’s evaluation of democratic performance and the normative appeal of liberal democracy qua liberal democratic principles which was why we focused on the latter. The widespread appeal of liberal democratic principles provides prima facie evidence against the cultural particularist’s assertion that Asian societies are inherently illiberal. Of course, it may still be the case that any attachment to Asian values diminishes the support for liberal democratic principles, the strength of that attachment notwithstanding.

The main proposition that ‘Asian’ values erode support for liberal democracy needs to be examined at two levels. First, ‘Asian’ personal values grounded in traditional social mores were not a significant predictor for the support of liberal democracy. This observation undermined the cultural particularist argument and bolstered the Confucian communitarian position arguing that personal values revolving around the primacy of family and society were not necessarily antagonistic to a Western human rights regime (Chan Citation2002; Weiming Citation1984; Bary et al. Citation1998). Having social obligations does not, ipso facto, preclude one from employing the language of rights in making legitimate moral claims nor does it prevent the endorsement of liberal democratic principles. The compatibility between Asian personal values and liberal democracy found was also consistent with the findings of more recent empirical studies (Shen and Tsui Citation2018; Zhai Citation2022).

The real obstacle to realising liberal democratic principles in East and Southeast Asia lies in the support for ‘Asian’ political values. In our study, a negative association was observed only for electoralism and political rights, not civil rights, contrary to our expectations. The protection of civil rights, defined as rights that protect vulnerable minorities from majoritarian oppression, distinguishes a liberal democracy from a non-liberal one (Merkel Citation2004; Mukand and Rodrik Citation2020). The broad support for civil rights and its invariability with the influence of ‘Asian’ political values suggest that we should not rule out support for liberal values even in Asian countries with high attachments to ‘Asian’ political values. However, much of this debate turns on what is meant by illiberal in the first place. Bell (Citation1995) defined an illiberal democracy through the substantive goal of the government in achieving economic growth and stability through paternalistic interventions, contra Mukaand & Rodrik (Mukand and Rodrik Citation2020) which defined liberal democracy in more proceduralist terms. Past empirical data lends some credence to Bell’s view of Asian democracy, showing that individual freedom was considered secondary to the overarching goal of achieving stability and prosperity by citizens of authoritarian regimes in Asia (Chu, Diamond, and Andrew Citation2010; Sing Citation2012). Read this way, it would be more useful to dispense with labels of ‘liberalism’ and ‘illiberalism’ unless we have an agreed definition and conclude that ‘Asian’ political values evince no hostility towards civil rights that engender greater protection for minorities and egalitarianism, but they do clash with the institution of a free and fair election and the right of freedom of expression.

However, the incongruence between ‘Asian’ political values and support for liberal political rights should not be seen as conclusive evidence against liberal democracy as the normative end goal in Asia. Equally important is the question of how these political values arise in the first place. As Zhai (Citation2022) noted, liberal democracies such as Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea have all abandoned authoritarian political values over the past few decades while such a cultural shift was not observed in China. Such bifurcation in cultural evolution illustrates that deference to authority in the political sphere may not be an instantiation of an essential Asian value system that reflects people’s true beliefs. Instead, ‘Asian’ political values may be artificially sustained and prevented from adapting by an autocratic ruling class. Further research into this area is needed before any causal factors for ‘Asian’ political values can be established. Moreover, Confucianism itself has undergone radical changes since the death of its founder in 479 BC, expanding from a one-dimensional thought to a multidimensional, multilevel ideology that came to define the Chinese national consciousness (Shin Citation2011). The rise in education and information flow has also been shown to correspond to an increase in a procedural understanding of democracy in China (Zhai Citation2019). It would be remiss to assume the timelessness of Asian political values as if they were a static concept immune to change.

Although modernisation was not the focus of this paper, our findings did provide some evidence for the human development thesis. In , most developed countries were clustered around the lower left corner with relatively low attachments to ‘Asian’ personal and political values. Therefore, we believe that socio-economic development does generally lead to a decline in ‘Asian’ personal and political values via a similar pathway of cognitive empowerment. However, we are unsure if this will necessarily lead to the rise in emancipative values, as defined by Welzel & Inglehart (Inglehart and Welzel Citation2003), and support for liberal democracy given the inherent tension between ‘Asian’ political values and electoralism and political rights as discussed in the preceding paragraphs. While we do not exclude the possibility of liberal democracy consolidating in Asia, we hesitate to conclude that liberal democracy will consolidate in all of Asia eventually, supplanting all other regime types. We expect regime types to continue to reflect the cultural heterogeneity in the region and experiment with a mix of features, transcending the Western liberal and Eastern authoritarian dichotomy.

There were a few limitations that have to be mentioned. First, while we based our construction of the ‘Asian’ values index on broad consensus in the literature, disagreements over the operationalisation of ‘Asian’ values are inevitable. Culture is notoriously complex and hard to measure. What we hoped to show was not that the values identified were particularly ‘Asian’, but rather, how the values that have historically been associated with Asian traditions interacted with regionality, demographics, and liberal democratic principles. Second, the analysis in the paper was done at the country level, not the individual level as we used data from two different survey sets. We do not know if the associations or lack thereof will hold for individuals in these countries. We expect demographic factors to play a much bigger role in mediating the relationship between ‘Asian’ values and support for liberal democratic principles but this remains to be proven. Third, a number of Asian countries were omitted in the second part of the analysis because they were not included in PRS, most notably China. The inclusion of mixed or closed regimes would strengthen the findings in this paper and we hope to include a larger sample of Asian countries in the future. Future studies may also consider incorporating opposite-worded questions to address measurement errors.

5.3 Conclusion

Our paper refuted Asian exceptionalism and undermined partially the assertion that ‘Asian’ values diminish support for liberal democracy. The particularist position is significantly weakened as we found very little evidence for Asian exceptionalism or the variability of support for liberal democracy with ‘Asian’ personal values. However, the negative association of ‘Asian’ political values with electoralism and political rights must be acknowledged. We cannot outright dismiss the prospect of liberal democracy taking root in authoritarian regimes in Asia nor can we accept unequivocally, as liberal universalists do, that liberal democracy is the ‘right’ political model for all Asian cultures. Given the incongruence between ‘Asian’ political values and particular liberal democratic principles, future research should focus on establishing the reasons why ‘Asian’ political values persist and if they vary under different socio-political arrangements. It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss these implications in depth, but this paper has provided empirical evidence to enrich the Asian values debate and leaves countries in Asia open to the possibility of mass support for alternative political models, thus averting the rigid dogmatism of the cultural particularist or the liberal universalist position.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Tan Sor Hoon and Dr. Cheng Cheng for their invaluable advice and guidance in writing this research paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel Ho

Daniel Ho is a graduate of Singapore Management University with a double degree in Business Administration (Finance Major) and Social Science (Political Science). He has a cumulative GPA of 3.99 and was the recipient of the Kwek Hong Png Valedictorian Award which is presented to the top graduating undergraduate of the University. During his internship with the Ministry of Trade and Industry, he pursued a research project that examined the disparity in the correlation between the profitability of the firm and wages across sectors in Singapore. He also interned with the Adam Smith Centre to further hone his academic research skills and worked on various projects, including writing course materials for a Business, Government and Society undergraduate course, working on the draft chapters of a Springer textbook on development and gathering cross-sectional data on the entrepreneurial desire in OECD for a working paper (What Can Industrial Policy Do? Evidence from Singapore) which was subsequently published in the Review of Austrian Economics. He wrote his senior thesis on “Asian vs Liberal Democracy: identifying the locus of conflict in the Asian Values Debate”.

References

- Ang, Hwee Min. 2021. ‘Gender Identity Issues “Bitterly Contested Sources of Division”; Singapore “Should Not Import These Culture Wars”: Lawrence Wong’. Channel News Asia. 1 February 2021. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/moe-gender-identity-issues-gender-dysphoria-culture-wars-296366.

- Barr, Michael D. 2000. “Lee Kuan Yew and the “Asian Values” Debate.” Asian Studies Review 24 (3): 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357820008713278.

- Bary, De, and Wm Theodore. 1998. Asian Values and Human Rights: A Confucian Communitarian Perspective. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Bauer, Joanne R., and Daniel A. Bell, eds. 2005. The East Asian Challenge for Human Rights.Repr. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Bell, Daniel, ed. 1995. Towards Illiberal Democracy in Pacific Asia. Basingstoke, Hampshire : New York: Houndmills.

- Bell, Daniel, ed. 2006. Beyond Liberal Democracy: Political Thinking for an East Asian Context. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

- Bernama. 2019. ‘We Are Free to Reject LGBT, Other Unsuitable Western Influences - Dr Mahathir’. New Straits Times. 18 June 2019. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2019/06/497206/we-are-free-reject-lgbt-other-unsuitable-western-influences-dr-mahathir.

- Chan, Joseph. 2002. “Moral Autonomy, Civil Liberties, and Confucianism.” Philosophy East and West 52 (3): 281–310. https://doi.org/10.1353/pew.2002.0012.

- Chang, Yu-Tzung, Yun-Han Chu, and Frank Tsai. 2005. “Confucianism and Democratic Values in Three Chinese Societies.” Issues & Studies 41 (4): 1–33.

- Chong, Alan. 2004. “Singaporean Foreign Policy and the Asian Values Debate, 1992–2000: Reflections on an Experiment in Soft Power.” The Pacific Review 17 (1): 95–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951274042000182438.

- Chua, Beng Huat. 2017. “Liberalism Disavowed: Communitarianism and State Capitalism in Singapore.” In Liberalism Disavowed, 50–73. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Chu, Yun-han, Larry Diamond, and J. Nathan Andrew. 2010. “Introduction: Comparative Perspectives on Democratic Legitimacy in East Asia.” In How East Asians View Democracy, edited by Doh Chull Shin. Paperback ed. 1–38. New York, NY: Columbia Univ. Press.

- Dahl, Robert A. 1971. Polyarchy; Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Dalton, Russell J., and Nhu-Ngoc T. Ong. 2005. “Authority Orientations and Democratic Attitudes: A Test of the “Asian Values” Hypothesis.” Japanese Journal of Political Science 6 (2): 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109905001842.

- Diamond, Larry Jay. 1999. Developing Democracy: Toward Consolidation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Diamond, Larry Jay. 2002. “Thinking About Hybrid Regimes.” Journal of Democracy 13 (2): 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2002.0025.

- Emmerson, Donald K. 1995. “Singapore and the “Asian Values” Debate.” Journal of Democracy 6 (4): 95–105.https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1995.0065.

- Englehart, Neil A. 2000. “Rights and Culture in the Asian Values Argument: The Rise and Fall of Confucian Ethics in Singapore.” Human Rights Quarterly 22 (2): 548–568. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2000.0024.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1989. “The End of History?” The National Interest 16:3–18.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1995a. “Confucianism and Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 6 (2): 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1995.0029.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1997. “The Illusion of Exceptionalism.” Journal of Democracy 8 (3): 146–149. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1997.0043.

- Huang, Min-Hua, Yun-Han Chu, and Yu-Tzung. Chang. 2013. “Popular Understandings of Democracy and Regime Legitimacy in East Asia.” Taiwan Journal of Democracy 9 (1): 147–171.

- Huntington, Samuel P. 1991. “Democracy’s Third Wave.” Journal of Democracy 2 (2): 12–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1991.0016.

- Huntington, Samuel P. 1993. “The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century.” In Nachdr. The Julian J. Rothbaum Distinguished Lecture Series. Vol. 4. Norman, Okla: Univ. of Oklahoma Press.

- Information Office of the People’s Government of Xinjiang. 2022. Fight Against Terrorism and Extremism in Xinjiang: Truth and Facts. Geneva: Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations Office at Geneva and other International Organisations in Switzerland.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Christian Welzel. 2003. “Political Culture and Democracy: Analyzing Cross-Level Linkages.” Comparative Politics 36 (1): 61. https://doi.org/10.2307/4150160.

- Jefferson, Thomas. 1776. “Declaration of Independence: A Transcription.” National Archives. 7 April 1776. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript.

- Kausikan, Bilahari. 1997. “Governance That Works.” Journal of Democracy 8 (2): 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1997.0024.

- Kim, Dae Jung. 1994. “Is Culture Destiny?” Foreign Affairs 73 (6): 189–189. https://doi.org/10.2307/20047005.

- Kim, Sungmoon. 2012. “A Pluralist Reconstruction of Confucian Democracy.” Dao 11 (3): 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11712-012-9289-7.

- Lama, Dalai. 1999. “Buddhism, Asian Values, and Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 10 (1): 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1999.0005.

- Langguth, Gerd. 2003. “Asian Values Revisited.” Asia Europe Journal 1 (1): 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s103080200005

- Lawson, Stephanie. 1998. “Democracy and the Problem of Cultural Relativism: Normative Issues for International Politics.” Global Society 12 (2): 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600829808443163.

- Lee, Kuan Yew. 1992. ‘Democracy and Human Rights for the World’. Tokyo, November 20. https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/data/pdfdoc/lky19921120.pdf.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan Way. 2002. “The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism.” Journal of Democracy 13 (2): 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2002.0026.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. 1959. “Democracy and Working-Class Authoritarianism.” American Sociological Review 24 (4): 482. https://doi.org/10.2307/2089536.

- Lührmann, Anna, Marcus Tannenberg, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2018. “Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes.” Politics & Governance 6 (1): 60–77. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i1.1214.

- Mahbubani, Kishore. 1993. “The Dangers of Decadence: What the Rest Can Teach the West.” Foreign Affairs 72 (4): 10–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/20045709.

- Mauzy, Diane K. 1997. “The Human Rights and “Asian Values” Debate in Southeast Asia: Trying to Clarify the Key Issues.” The Pacific Review 10 (2): 210–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512749708719218.

- Merkel, Wolfgang. 2004. “Embedded and Defective Democracies.” Democratization 11 (5): 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340412331304598.

- Mill, John Stuart, F. Rosen Mark Philp, and John Stuart Mill. 2015. On Liberty, Utilitarianism, and Other Essays. New ed. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mukand, Sharun W, and Dani Rodrik. 2020. “The Political Economy of Liberal Democracy.” The Economic Journal 130 (627): 765–792. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueaa004.

- Munck, Gerardo L. 2009. Measuring Democracy: A Bridge Between Scholarship and Politics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Muzaffar, C. 1996. “Europe, Asia and the Question of Human Rights.” Just Commentary 23:1–6.

- Nathan, Andrew J. 2007. ‘Political Culture and Regime Support in Asia’. In Conference Paper, The Future of US–China Relations, Los Angeles: USC US–China Institute.

- The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2022. OHCHR Assessment of Human Rights Concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations.

- Omondi, Sharon. 2017. ‘The Macro-Cultural Regions Of Asia’. World Atlas. 27 September 2017. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-macro-cultural-regions-of-asia.html#:~:text=In%20Asia%2C%20there%20are%20four,people%20in%20the%20specific%20regions.

- Parekh, Bhikhu. 1992. “The Cultural Particularity of Liberal Democracy.” Political Studies 40 (1_suppl): 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1992.tb01819.x.

- Park, Chong-Min, and Doh Chull Shin. 2006. “Do Asian Values Deter Popular Support for Democracy in South Korea?” Asian Survey 46 (3): 341–361. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2006.46.3.341.

- Philip, Roessler, and Marc M. Howard. 2009. “‘Post-Cold War Political Regimes: When Do Elections Matter?’“ Democratization by Elections: A New Mode of Transition, edited by Staffan I. Lindberg, 101–27. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Pye, Lucian W. 1999. “Civility, Social Capital, and Civil Society: Three Powerful Concepts for Explaining Asia.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 29 (4): 763–782. https://doi.org/10.1162/002219599551886.

- Richard, Wike, Janell Fetterolf, Shannon Schumacher, and J. J. Moncus. 2021. Citizens in Advanced Economies Want Significant Changes to Their Political Systems. Pew Research Center.

- Rosemont, Henry. 2004. “Whose Democracy? Which Rights? A Confucian Critique of Modern Western Liberalism.” In Confucian Ethics, edited by Kwong-Loi Shun and David B. Wong,1sted., 49–71. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606960.005

- Sandel, Michael J. 1998. Liberalism and the Limits of Justice. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Schedler, Andreas. 2015. “The Politics of Uncertainty: Sustaining and Subverting Electoral Authoritarianism.” In Oxford Studies in Democratization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1976. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. with A new introduction by Tom Bottomore. 5th ed. London: Allen and Unwin.

- Seifert, Franz. 1998. “A Cultural Challenge to Liberal Democracy in Southeast Asia?” IHS Political Science Series 53. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/24673/ssoar-1998-seifert%02a_cultural_challenge_to_liberal.pdf;jsessionid=4A024D40508BCB7E15EFD0E8B459E6C3?sequence=1

- Sen, Amartya. 1997. “Human Rights and Asian Values: What Kee Kuan Yew and Le Peng Don’t Understand About Asia.” The New Republic 217 (2–3): 33–40.

- Shen, Fei, and Lokman Tsui. 2018. “Revisiting the Asian Values Thesis: An Empirical Study of Asian Values.” Asian Survey 58 (3): 535–556. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2018.58.3.535.

- Shin, Doh Chull. 2011. Confucianism and Democratization in East Asia. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139084086.

- Shin, Doh Chull. 2017. “Popular Understanding of Democracy.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics 1 (January). https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.80.

- Sing, Ming. 2012. “Explaining Support for Democracy in East Asia.” East Asia 29 (3): 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-012-9176-1.

- Strangio, Sebastian. 2023. “ASEAN Tweaks Its Approach Toward Military-Ruled Myanmar.” The Diplomat. 9 June 2023. https://thediplomat.com/2023/09/asean-tweaks-its-approach-toward-military-ruled-myanmar/.