ABSTRACT

Pre-election policy statements are important because they reveal information about parties’ policies and intended post-election priorities. Content analysis data from election manifestos, webpages, television broadcasts, and leaders’ speeches reveal clear left-right differences between the dominant Labour and National parties at elections between 1984 and 2023, with the exception of 1990. Between 1993 and 1999 and since 2011 broadcasts and speeches by National have been more right-wing on a left-right summary dimension than National’s manifestos and detailed webpages. The reverse was usually true for the right-wing Act Party, while New Zealand First’s position varied more in broadcasts and speeches than in its print programme. No real pattern for left-right topics was evident for the other parties. However, references to the environment, indigenous rights, and foreign policy were higher in long print documents than in television broadcasts and speeches. In contrast, political authority references were relatively low in print documents. When using equivalent documents, the Green and Māori parties, followed by Labour, were usually most supportive of environmental protection and socially progressive policies. The results confirm the importance of using similar documents, insofar as is possible, when making comparisons. In addition, shorter documents may be more useful for understanding parties’ main priorities.

Introduction

This article compares the two main and largest minor New Zealand political parties’ positions in different policy documents between 1984 and 2023. Parties issue election programmes in order to compete for votes. According to mandate theories of responsible party government, parties should present achievable policies to voters in their election programmes, and then implement their pre-election commitments if they become the government (Schelder Citation1998, 195). New Zealand’s first past the post electoral system produced single party governments between 1935 and 1993, who faced few constitutional limits on their actions (Lijphart Citation2012, 20–21, 251; Palmer Citation1992, 1–3). The responsible party government convention that parties who won elections would adhere to their pre-election policy commitments was imperative for avoiding elective dictatorship (Mulgan Citation1992, 513–531).

New Zealand political parties issued increasingly detailed manifestos between the 1950s and the late 1970s (Gibbons Citation2000). After criticisms of breaches of pre-election promises by parties between 1984 and 1993, and the introduction of proportional representation in 1996, New Zealand political parties campaigned on shorter policy statements. However, during the 2000s parties have often published detailed policy statements on their webpages. Until 2014, parties were also allocated free airtime for nation-wide television broadcasts, and these were important for election campaigning. Speeches from the Throne outlining a new government’s legislative programme also show parties’ priorities.

Policy documents have been coded using the Manifesto Project’s methods for classifying text. Comparing the results for different documents shows whether parties have followed a common agenda throughout election campaigns. If the results are similar, there are potential resource savings from using shorter documents in textual analysis by human coders. Since parties have taken considerable care about the policy messages in their broadcasts, the broadcasts may also provide insights into parties’ policies that are less evident from long manifestos and webpages. This article also considers which documents are best for understanding parties’ policies.

This article first discusses methods for coding policy statements, and what constitutes an election programme. It then outlines the election policy documents collected and coded for New Zealand’s dominant Labour and National parties, which are respectively centre-left and centre-right, and briefly considers the range of issues covered in different policy documents. The focus then switches to the percentage of Labour’s and National’s policy documents about different policy topics. Parties’ positions in aggregate on a left-right dimension and a social and environmental priorities dimension, including the positions of smaller parties that have been represented in Parliament or influenced electoral competition, are then compared.

Coding parties’ policies and defining election programmes

The Manifesto Project has collected election manifestos from around the world, initially for countries that have been continuously democratic since the end of the Second World War. Sentences in these programmes have been coded using standardised pre-set categories. For instance, a promise to increase the number of hospital operations would be coded as welfare state expansion, while a commitment to longer prison sentences would be coded as law and order: positive. Sentences with multiple messages are split into separate quasi-sentences, each of which is allocated a code (Werner et al. Citation2023). The sentences for this article have been manually coded by the author, who has coded New Zealand programmes for the Manifesto Project. Texts were coded in Excel, and Excel’s countif command was used to count the number of sentences in each category.

The Manifesto Project defines election programmes as ‘text published by a political party or presidential candidate … to compete for votes’ (Werner et al. Citation2023). The ‘ideal type’ of an election programme is an authoritative and comprehensive statement of party policy, which all party candidates have agreed to support. A single document is preferred, although sometimes press releases or webpages are the only documents available (Manifesto Project Citation2022). In a few countries, most notably Australia, the leader’s campaign opening speech is often the most authoritative statement of party policy (Budge Citation2013, 134, Citation2015). Well into the twentieth century parties’ programmes were short enough for newspapers in some countries, including New Zealand, to print in full (Gibbons Citation2003/Citation2024; Laver and Elliot Citation1987, 162–163). Sections, and sometimes the whole text of short programmes, have often been printed in brochures for mass distribution. However, because the attention span of most voters is limited, parties have had to keep their brochures short. Media coverage also ensures voters are aware of key messages from long party programmes (Merz Citation2018, 84, 107, 135, 141).

The range of documents coded by the Manifesto Project for some countries has been criticised (Hansen Citation2008, 208). It has been argued that using documents such as ‘speeches, pamphlets, newspaper articles and leaflets, as manifesto proxies’ may introduce ‘measurement error’ that ‘is often manifested as a centrist bias in parties’ left-right positions’ (Gemenis Citation2012, 594, Citation2013). In particular, party speeches tend to be high in references to political authority and social harmony, and less about policy preferences, suggesting these two categories should be excluded from left-right scales that include speeches (Benoit et al. Citation2012, 608). Research using Twitter posts and parliamentary speeches by politicians has also found them to have much higher references to democracy and to political authority than election programmes. More generally, the policies political actors emphasise is influenced by the communication channel used (Ivanusch Citation2024, 15, 21).

Manifesto Project criteria for identifying an election programme include the name of the document, whether it purports to represent the views of the party as a whole, whether it is party policy for the entire election campaign, and whether it reflects the party’s programmatic profile. The guideline about no external constraints on length (Merz and Regel Citation2013, 150) could be questioned, except if this constraint is very tight, because analysis focuses on the proportion of sentences about different topics. Longer documents contain more information and cover more topics than shorter programmes (Benoit, Laver, and Mikhaylov Citation2009, 501, 497; Gabel and Huber Citation2000, 100). However, they may also indicate a divided party and therefore be less precise, while small parties also often lack the resources to produce a long manifesto (Budge, McDonald, and Meyer Citation2013, 82). Furthermore, changes in the length of programmes may reduce their comparability over time (Hansen Citation2008, 208), and also affect whether voters read the full text, or instead consume shorter policy summaries. A comparison of the short and long versions of programmes for two German elections showed no systematic variation in left-right positions. In shorter documents, however, parties tended to emphasise their own topics more (Merz and Regel Citation2013, 160, 163, 165).

Even when substitutes to the best documents have been used for some countries, parties are still accurately classified in terms of being left or right-wing. Nevertheless, the Manifesto Project has been improving its document collection for countries as better documents become available (Budge Citation2013, 136–138).

New Zealand election policy documents

Opening campaign speeches by New Zealand party leaders were broadcast on public radio from the 1930s, and from the 1960s also on state-owned television channels. Successive single party governments were strongly committed to their detailed manifesto promises (Mulgan Citation1978). Living standards in New Zealand fell in the 1970s as international demand for wool decreased, and the United Kingdom’s accession to the EEC reduced access for New Zealand’s dairy and sheep meat exports (Neill Citation2008). By the time of the 1984 snap election, which is the first election covered by this paper, opposition parties argued the economy was in crisis (Goldfinch and Malpass Citation2007, 128).

While the left-right positions of New Zealand political parties’ largely fit well with existing interpretations of their positions, National’s short 1984 programme has been an important exception. Content analysis results have suggested National’s 1984 left-right position was its most right-wing ever (Gibbons Citation2000, 216–217, 208; Citation2011, 49, 52). This was surprising because although National had decreased tariffs, introduced voluntary unionism, reduced spending on education and health, and some economic deregulation had taken place, National’s comprehensive 1982 wage and price freeze was still in effect in 1984. In addition, National’s support for ‘Think Big’ industrialisation projects, subsidies to farmers, and pension policies had increased government expenditure and debt (Goldfinch and Malpass Citation2007, 125–127). It is possible that National’s television broadcast may provide a better depiction of its policies.

Television audiences fell sharply during party political broadcasts. However, even after they stopped being screened on all channels, 239,000 people watched the 2014 opening broadcasts and 279,000 watched the closing broadcasts (Electoral Commission Citation2015, 28–29). This provided an incentive for parties to think carefully about the messages conveyed. The broadcasts included graphs, text, images and video footage, and, to some extent, were a short version of a party’s manifesto that was broadcast, rather than mailed, to households. The television broadcasts were particularly important in the 1980s and 1990s, when they were relatively long (Church Citation2000, 106; Levine and McRobie Citation2002, 122, 164). Whereas in 1984 the two main parties each had an hour in total for their opening and closing broadcasts, the time had fallen to 25 minutes by 2008. From 2002, newspaper reporting often focused on the longer and non-televised, but increasingly broadcast on the internet, party campaign openings, whose mid-afternoon weekend time slots worked better for journalists. However, the television broadcasts were still important (Robinson Citation2009, 80–89). After the 2014 election the nation-wide television broadcasts ended, and parties were instead given funding for television and on-line advertisements (Peacock Citation2016).

The webpage documents, which had been archived by New Zealand’s National Library and by the author, were consolidated into a single document. All the policy statements have been recoded. Whereas the Manifesto Project’s coding advice currently largely focuses on policy goals, rather than means, apparent policy means have also been coded for this article (Zulianello Citation2014, 1734). For instance, ‘upgrade water infrastructure to create jobs’ was coded as a ‘double-duty solution’, with codes for both the short-term objective of more employment and the long-term objective of better infrastructure (Ardern Citation2021, 74; Stiglitz Citation2020, 12). Introductory statements by party leaders have also been coded, although this is currently strictly verboten by the Manifesto Project, whenever this resulted in a fuller picture of a party’s policies.

shows the documents coded for Labour. Labour’s full manifestos in 1984 and 1987 had very limited pre-election release, because MPs wanted to avoid large numbers of firm commitments in a period of economic crisis (Hubbard Citation1990). Labour’s long 1990 manifesto lacked policies on some controversial topics (Collins Citation1990), while its 1993 manifesto was published by a non-party organisation answerable to the party leader. For elections between 1996 and 2011 the full Labour Party manifesto was an internal policy document, that was only widely available after the election (Gibbons Citation2003/Citation2024).

Table 1. Labour Party documents coded, with number of sentences in brackets.

Between 1996 and 2005 Labour sought to increase its credibility by campaigning on limited range of promises, foreshadowing to some extent, and then explicitly using, a pledge card approach adopted by the British Labour Party from 1997 (Pearse Citation2000, 135–136). Labour’s specific promises were expanded upon in speeches, and also in brochures distributed to every household. However, there is no pre-election manifesto or webpages, or comprehensive set of press releases available for Labour in 1996. The use of taxpayer funding by Labour to print its brochures was criticised after the 2005 election (Thomson Citation2006). Labour subsequently abandoned both the pledge card approach, and also the nation-wide distribution of a similar document. In 2014, 2020 and 2023 Labour published a pre-election manifesto on its webpage, but not in 2017 when Labour’s leader changed shortly before the election.

The longest Labour document coded was Labour’s 2005 webpages, which contained 3323 sentences. Labour’s television broadcasts have varied between 97 policy sentences in 1999, when most of its broadcast was members of the public talking about their concerns, and 472 sentences in 1984. Some of Labour’s manifestos have contained only slightly more text than its brochures at other elections, indicating that documents can be difficult to classify. Labour’s post-election Speeches from the Throne, which outline a government’s policy priorities, were often very short, with the longest being 339 sentences in 1999.

shows the documents coded for National. National’s 1987 and 1990 manifestos had print runs of 92,000 and over 70,000 respectively, while its 2002 manifesto was inserted in a nation-wide Sunday newspaper with a circulation of over quarter of a million (Gibbons Citation2003/Citation2024). National’s 1996 leader stated that with the introduction of proportional representation, detailed programmes were less likely (Laugesen Citation1996, 1). However, since the early 2000s National has increasingly been using the Internet to distribute its policy statements. National’s unwieldy 2008 policy webpages contained 6238 sentences, but have become more concise since. National’s webpages have often included policy statements on topics that the party has felt it needs to have a policy statement on, but that it hoped would not become an important election issue. One example was National ‘quietly’ releasing its 2005 defence policy (Tunnah Citation2005). Similarly, National’s policy on the Māori seats at the 2008 election, which involved no changes until at least 2014, was quickly described by its leader as ‘not a bottom line’, that by 2014 had become too divisive to contemplate and a matter for Māori people to decide (NZPA Citation2008; Young Citation2014). National’s webpages have also included sections on topics which have been a low priority, when having policies on that topic has the potential to attract support from issue publics, or there has been pressure from the media to provide a policy statement.

Table 2. National Party documents coded, with number of sentences in brackets.

At the 2005 and 2008 elections National summarised its policies in brochures, to compete with Labour’s pledge card, but the 2011 equivalent was only published on its webpage. For elections between 2014 and 2020 no real equivalent document could be identified. However, in 2023 National summarised its politics in its Back on Track brochure. The series for National campaign launch speeches starts in 1999, when its leader’s speech was the most prominent policy statement on National’s webpage. Only in 2008 (208 sentences) and 2023 (215 sentences) have more than 200 policy points been made in a Speech from the Throne for a National government.

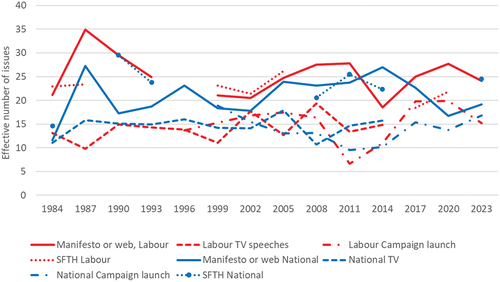

shows Labour’s manifestos and webpages have covered the most policy issues, with these pre-election documents averaging 25.1 effective issues (Laakso and Taagepera Citation1979; Merz and Regel Citation2013, 162). Speeches from the Throne, which averaged 22.5 effective issues, also covered a relatively high number of issues considering their brevity. In contrast, Labour’s television broadcasts and campaign speeches averaged only 14.1 and 15.3 effective issues respectively. Labour’s short 2011 campaign speech, which was held unusually late in the campaign, had a strong focus on opposition to state asset sales and an effective issue score of just 6.6.

National manifestos and webpages have covered an average of 20.7 effective issues although the average is reduced by the low number of topics National covered in 1984. National’s television broadcasts have invariably covered fewer issues, averaging just 14.6 effective issues. While National’s Speeches from the Throne have covered a wide range of issues, an exception is 1984, when the speech opening the last, and very brief, session of the third National Government has been coded as an additional policy statement.

These results generally provide further evidence that longer pre-election policy statements usually cover a wider range of topics (Merz and Regel Citation2013, 163). However, the post-election tradition that New Zealand governments state that they will unite the country, and consider the views and needs of all population groups (Mulgan Citation1992, 520, 524), has usually resulted in a high number of topics being covered in the relatively short Speeches from the Throne.

Ideological dimensions and topics discussed

Party competition in New Zealand is usually primarily structured around a left-right divide about economic policy and the level of spending on social services, and an associated urban-rural divide. In addition, topics about the structure of society, social change, the environment and foreign policy are important, and are often seen by voters as constituting a separate dimension of competition (Vowles et al. Citation1995, 108; Vowles, Coffe, and Curtin Citation2017, 11). This second dimension is here described as the environment and socially progressive versus economic development and socially conservative dimension.

shows the main coding categories used to operationalise the left-right economic and social policy divide, and also the description for agriculture and farmers. For instance, the market economy categories aggregate references to free markets and private ownership, policies to help businesses, and support for free trade. In contrast, the state intervention categories measure support for left-wing economic policies, such as consumer protection and economic controls, for economic planning and for corporatism, and for state ownership. Support for labour groups and expanding social services are also traditionally leftist policies. In contrast, references to government economic efficiency, balanced budgets and low inflation are important right-wing economic policy priorities (Laver and Budge Citation1992, 24; Volkens and Merz Citation2018). Examples of coded sentences for the main categories are shown in the on-line appendix.

Table 3. Economic policy and social services topics.

shows the brief descriptions for the socially conservative, economic development, environmental and socially progressive topics discussed. For instance, the social conservatism categories measure references to New Zealand’s national way of life, to traditional families, to tough law and order policies, and to national unity. The production and infrastructure categories contain references to higher economic growth, and to new infrastructure and to technical education. In contrast, the environment and sustainability categories measure references to protecting the environment and to ensuring development is environmentally sustainable. The military and peace and cooperation categories capture opposing views on foreign policy (Laver and Budge Citation1992, 24–26).

Table 4. Socially conservative, economic development, environmental and socially progressive topics.

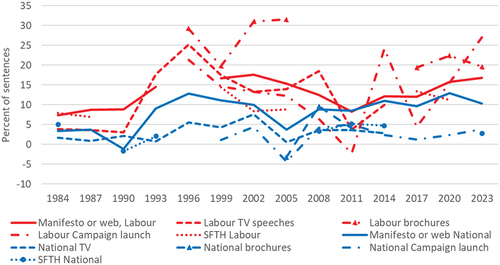

Most important economic policy and social services topics

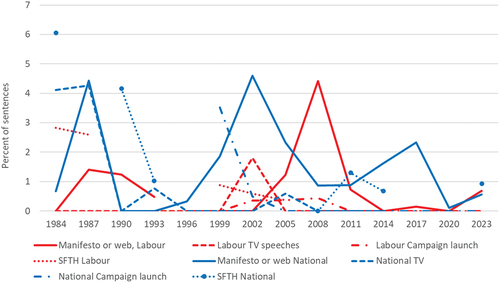

The focus now switches to analysing parties’ policies on the most important economic policy and social services topics. National’s manifestos in 1984 and 1987 had a high emphasis on market economy messages due to its free trade, deregulation, and pro-business policies, which shows were less strong in its television speeches. The high result for market economy themes in National’s 2014 campaign launch was because this speech focused on home ownership. Labour’s free market policies when in government during the 1980s were not very evident in pre-election policy documents (James and McRobie Citation1993, 11, 31), but were somewhat more apparent in its 1987 post-election Speech from the Throne. Labour committed itself to free market policies in some, but not all, 1999 policy documents, mostly due to its promises of support for business. Support for a more market direction in policy statements by the sixth Labour government was most evident in its 2020 Speech from the Throne.

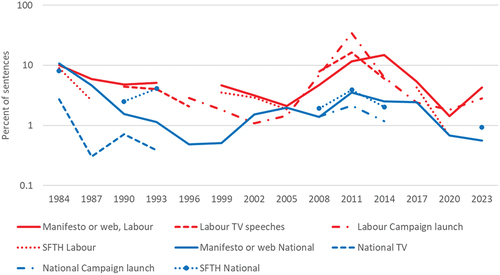

At the 1984 election Labour was fractionally less in support of economic interventionism () in its manifesto than National was. State intervention references in Labour’s policy documents trended downwards until the 2008 election, when Labour discussed its nationalisation of the railways and partial nationalisation of Air New Zealand, and in its campaign launch also criticised financial deregulation. Labour most strongly supported state intervention themes at the 2011 election, with its leader’s campaign speech, in particular, focussing on criticism of National’s plan to sell shares in state-owned enterprises. This necessitates a logarithmic scale for . Labour was relatively interventionist again in 2014, when it committed itself to protecting consumers from big business and reducing foreign ownership, and also in 2023 when protecting tenants and increasing competition in the grocery and banking industries were important election issues.

National’s 1984 manifesto, but not its leader’s speech, heavily emphasised state intervention, with the party discussing the desirability of energy self-sufficiency; protecting manufacturers, even as tariffs were reduced; and the necessity of the wage and price freeze. Self-sufficiency and protectionism, along with market regulation policies, were also relatively strong in National’s 1987 manifesto. National’s state intervention references since 1990 have mostly concerned market regulation to protect small investors and consumers, including more competitive telecommunications and electricity markets.

confirms that the Labour Party has usually emphasised policies to help labour groups more than National has. The biggest exception was the 1990 election when National’s closing address promised to reduce unemployment, and, despite promising voluntary unionism, unequivocally stated, ‘we are not going to smash unions, abolish awards, cut pay or overtime or weekend rates’. National made more negative than positive references to labour groups only in its 1984 television broadcasts. In those broadcasts National’s leader, Sir Robert Muldoon, claimed that ‘extreme left’ Socialist Unity Party and Federation of Labour leaders would be determining Labour Party policy, and also discussed how National had ended compulsory trade union membership.

Rural voters have shown a strong tendency to vote for National (Vowles Citation2020, 52), and shows that National’s manifestos and webpages have invariably emphasised helping agriculture and farmers. However, agriculture and farmers were covered least by National in its short 1984 and 1999 manifestos, which were the only elections when Labour programmes emphasised agriculture and farmers more than National’s. Probably because of its economic importance, farming has invariably been discussed in Speeches from the Throne. However, farming has often been omitted from pre-election speeches. Notable exceptions were National’s long 1984 television broadcast, and National’s 2023 campaign launch speech.

shows Labour has usually supported government spending on welfare, which includes health and social housing, and here also Keynesian demand management policies, more than National has. An important exception was the 2011 election when Labour’s short-lived policy of increasing the age of eligibility for superannuation resulted in it making more references in its opening campaign speech to welfare state limitation than to welfare state expansion. The increase in welfare references from 1993 initially largely reflected pressure for greater health expenditure. National supported reducing welfare spending in its 1990 manifesto, when it promised welfare reform, and also in its 2005 campaign launch speech. Since 1993 National has been more in favour of welfare state spending in its manifesto or on its webpage than in speeches. Labour’s brochures in 1999 and 2002 showed much stronger support for the welfare state than its other policy statements.

Figure 6. Percent of sentences about welfare state expansion and Keynesian demand management less welfare state limitation.

For education (), parties’ positions have frequently overlapped. Education was particularly prominent in Labour’s 1987 television broadcasts, with its leader stating that the days of New Zealanders leaving school early were over, and that New Zealand had taken ‘education too lightly for too long’. Similarly, National’s 2008 television broadcast and brochures had high coverage of education, reflecting its promises to improve education standards and for better reporting to parents. In addition, National’s 2008 webpages had a strong focus on the need for better school buildings, while National’s 2011 opening campaign speech argued that asset sales were imperative to fund modern learning environments and earthquake proof classrooms.

In contrast, in 1984 National largely ignored education (but not vocational training) in its policy statements. Even in National’s pre-election Speech from the Throne the only references to education were about requiring schools to increase the number of hours devoted to teaching ‘basic subjects’. National’s 2023 education policies also stated that schools would be required to concentrate on core subjects, with this implicitly involving less emphasis on topics relating to gender and ethnicity. Although National has campaigned on improving educational outcomes, since the early 1980s National governments have invariably reduced real education expenditure (Gibbons Citation2017, 59).

National has usually emphasised government efficiency themes and orthodox macroeconomic policies, such as balanced budgets and low inflation, more than Labour (). These economic constraint themes were particularly salient in National’s 2008 and 2011 campaign opening speeches, when John Key criticised the level of spending by Labour and promised better economic management. In 2011, Key was also justifying the need for asset sales. National also campaigned on the desirability of lower government spending in 2020, when the Labour-led government was borrowing heavily to provide support for workers and businesses during shutdowns to contain the spread of Covid-19. In addition, National criticised spending on initiatives like light rail. However, at the 2023 election National’s campaign speech made relatively few references to economic constraint themes.

Labour’s government efficiency and economic orthodoxy references have sometimes also been high. In particular, in 1984 Labour expressed disquiet about the size of the government debt, and supported a broader tax base. Labour’s concern about economic orthodoxy themes was also high in 2011, when it criticised the level of borrowing by National.

Most important socially conservative, economic development and socially progressive topics

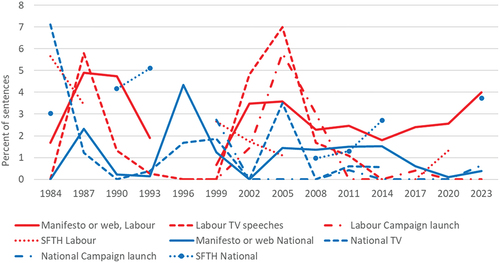

The focus now switches to analysing Labour’s and National’s policies on the socially conservative, economic development, environmental and socially progressive topics shown in . The percentage of policy statements by Labour and National about socially conservative topics is shown in . At the 1984 election Labour’s television broadcasts had a strong focus on national unity, and an end to the ‘politics of confrontation, of negation and division’. References to ‘working together’, volunteering and New Zealand’s traditional national way of life were also an important part of Labour’s 1990 television broadcasts. Internationally nationalism and national unity are emphasised most by the right (Budge and Judith Citation2001, 22). However, in New Zealand these topics can be consistent with a left-leaning economic policy direction.

National made no references to law and order or traditional morality in its 1984 manifesto or leader’s speech. However, since 1987 law and order has consistently been an important part of National’s election campaigning. References to moral values and traditional families, which in television broadcasts and speeches often alluded to the childlessness of Labour’s leaders at elections between 1990 and 2008 and in 2017, have also featured in National’s campaigning (Church Citation2000, 106–107; Robinson Citation2019, 262–263). Law and order references, opposition to drug use, and the need for civil society to support beneficiaries were particularly high in National’s 2008 television broadcast. National strongly campaigned on socially conservative themes again at the 2023 election.

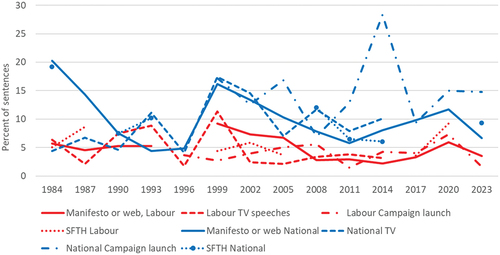

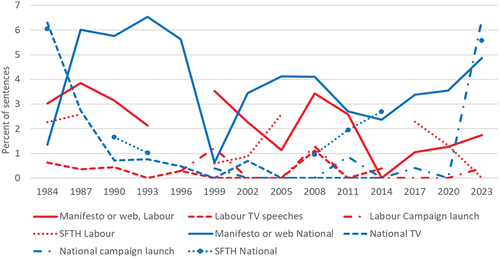

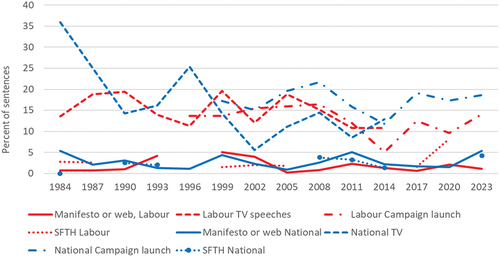

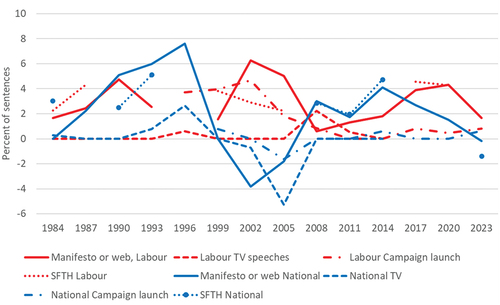

confirms that the type of document strongly matters for the extent to which parties emphasise political authority topics (Gemenis Citation2012, 598; Ivanusch Citation2024, 15). For the manifestos and webpages, political authority references have seldomly been more than five percent of the content. For television broadcasts and party campaign launches, by contrast, political authority has usually been more than ten percent of the content. Labour and National have overlapped on political authority for similar types of policy statements.

Political authority sentences were more than a third of the content of National’s 1984 television broadcasts, when its leader, Sir Robert Muldoon, unsuccessfully campaigned on his record as ‘the most experienced Finance Minister in the Commonwealth’. Muldoon also stated Labour’s leader had, ‘no knowledge of, or understanding of, economic affairs’. National again campaigned strongly on competency in 1996 in its television broadcast, with Jim Bolger emphasising National’s ability to provide strong government.

Labour’s and National’s positions on productivity and infrastructure () have frequently overlapped. National’s references were particularly high in 2020, when its webpages listed all the new roading projects it supported. In contrast, National’s leader’s speech was more selective. National’s 1984 manifesto emphasised New Zealand’s need to increase production and export earnings, and also technical education initiatives. Labour’s productivity and infrastructure references were highest in its 2008 leader’s speech, when its leader discussed the growth New Zealand had experienced, and investments which had been made in infrastructure and technical education.

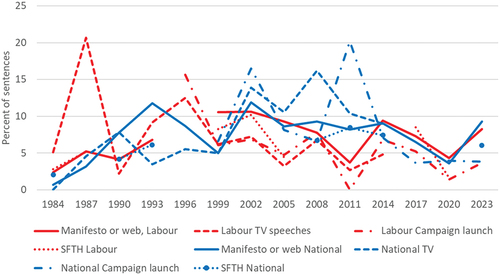

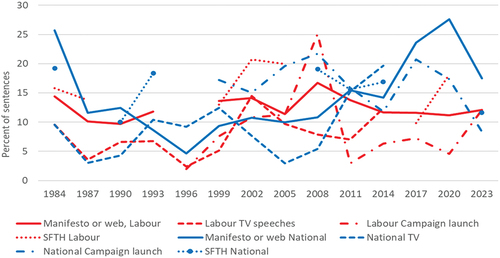

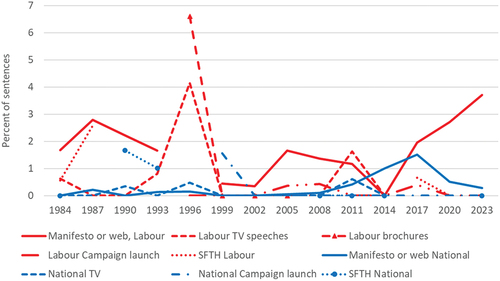

The environment and sustainability () are also topics where the type of document is important. The environment and sustainability have been important in relatively long National Party manifestos and webpages, and at four elections have been over eight percent of the content. However, the environment and sustainability were ignored in National Party television broadcasts between 1999 and 2011, and in National Party campaign launches between 2002 and 2014. Indeed, in her 1999 campaign launch speech Jenny Shipley stated, ‘National will not allow … extremists to lock up our land, sea and forestry resources’. In long policy documents during the 2000s, National has discussed the need for environmental protection and sustainable development, including new hydro-electric schemes and tax breaks for electric cars and fencing subsidies for farmers who own land adjacent to reserves. In contrast, in shorter documents National has tended to ignore or downplay the environment. In longer documents there is less need for prioritisation, and parties can seek to appeal to a wider range of groups of voters.

Similarly, the environment has usually been more prominent in Labour’s manifestos and webpages than in speeches by its leaders. At the 1984 election, when Labour needed to win provincial electorates dependent on resource extraction, there were probably good reasons for Labour to ignore the environment in its television broadcast. In contrast, its pre-election manifesto briefly promised to ‘carefully integrate conservation and development’. The growth of tourism during the 1980s made conservation and development seem more intertwined, and after 1987 Labour consistently, but briefly, emphasised the environment and sustainability in its television broadcasts. Except in its narrowly focused 2011 leader’s speech, these themes have also been covered in Labour’s official policy launch.

Labour heavily emphasised cultural activities in its 1999 leader’s speech (), and also in its 1999 and 2002 manifestos and 2005 webpages. Cultural activities were emphasised in National’s webpages after 2005, but not in campaign speeches by the party leader. This may have been a deliberate decision because Labour had become strongly associated with support for the arts, and perhaps also to leave space for the centrist United Party, which in 2005 was seeking the support of recreational hunters and fishers (Dunne Citation2007, 136).

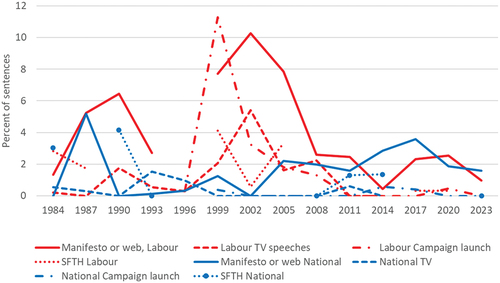

For policies about rights for New Zealand’s indigenous Māori population, less negative references to Māori rights, National’s position () shows the most variation. Between 1990 and 1996 National’s manifestos emphasised the need to settle Treaty claims. In 2002, however, National’s manifesto stated that ‘too much about the Treaty of Waitangi divides us’ and that National would ‘Close the book on historic Treaty claims’. National’s 2005 television broadcast went further, promising to ‘end racial separatism’, including abolishing the Māori seats. Claims that the Treaty process had become divisive split the National Party, with some National supporters feeling the messages being used were simplistic and had racist undertones (James Citation2016, 220, 228).

At the 2008 election, National ignored the position of Māori in speeches, and made more positive than negative references to Māori rights in its webpages. This was because John Key, who was National’s leader between 2006 and 2016, regarded Māori rights as a distraction (James Citation2016, 219–221, 234, 236). Subsequent National Party leaders have usually taken a similar approach. However, in 2023 National made slightly more negative than positive references to indigenous rights in its webpages. The Speech from the Throne, which was influenced by National’s coalition partners, was even more negative. Labour has usually said more about improving the position of Māori in its manifestos and webpages than in its other pre-election statements.

Figure 14. Percent of sentences about support for Māori, equality and indigenous rights: positive for Māori, less negative references to rights for Māori.

shows that Labour has almost always emphasised policies to help women, or that reject traditional moral values, more than National has. Labour’s references to these topics were particularly high in Labour’s 1996 television broadcast, where its leader, Helen Clark, talked at length about the obstacles women faced, and the need for more women in politics. Labour’s 1996 brochure also discussed the need for equal opportunities for women, the need for public policy to take their needs into account, and for more women to be involved in decision making. Since 2017, Labour has sought to appeal to women, through strongly emphasising the need for policies to actively advance equality, and also advocated policies to support the transgender community.

National Party policy-makers have sometimes stated that the needs of men and women are similar (McLeay Citation1994, 66–67). However, between 2011 and 2020 National’s webpages invariably included a section on policies to help women, including monitoring the gender pay gap and appointing more women to Crown bodies. In office, however, National was criticised for showing little commitment to improving the position of women (O’Neil Citation2014).

Figure 15. Percent of sentences about positive references to women, equality for women, and opposition to traditional moral views.

and show defence and peace and cooperation themes have appeared irregularly in Labour and National policy documents. Labour heavily emphasised peace and cooperation themes in its 1987 policy statements, and opposition to nuclear weapons was important to Labour’s election victory (Vowles Citation1990). Labour emphasised peace and cooperation themes again between 2002 and 2011 in speeches, but not in its brochures. National’s 1984 opening television broadcast, but not its manifesto, discussed ANZUS, the Second World War, Soviet aggression and also the need for disarmament and international financial reform.

National ignored defence and disarmament in its 1990 pre-election policy statements, to avoid priming anti-nuclear sentiment (Stone Citation1990, 4). However, National’s post-election Speech from the Throne committed New Zealand to alliance arrangements with Britain and the United States, providing they were consistent with remaining nuclear free. National’s 2002 manifesto, but not its television broadcast, and only to a very small extent its opening campaign speech, promised to rebuild New Zealand’s defence forces. Labour emphasised peace and cooperation statements in its 2002 and 2005 television broadcasts, while National also did so in 2005 to dispel claims by Labour it would abandon New Zealand’s anti-nuclear policies.

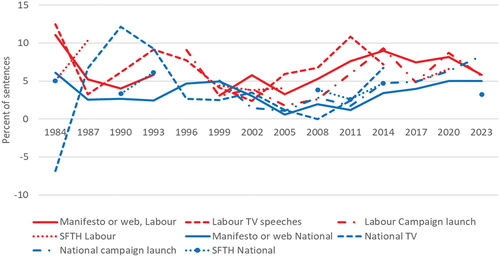

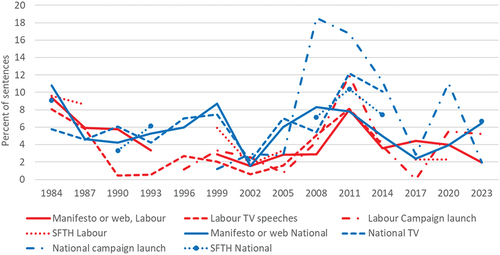

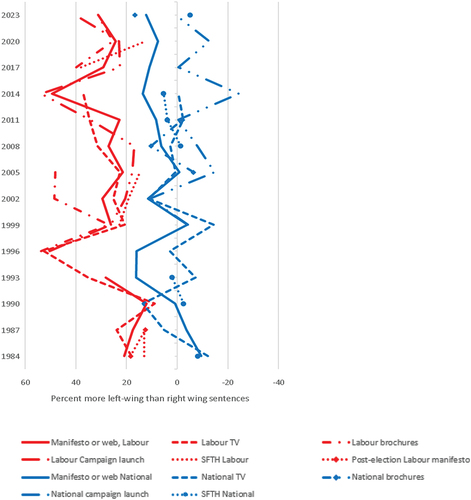

Parties’ positions on the left-right dimension

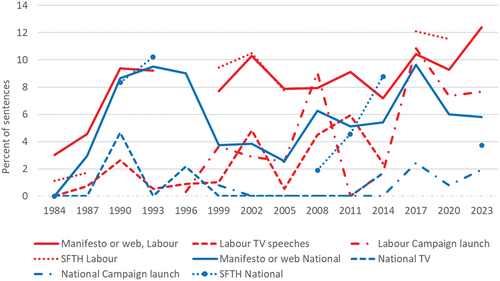

compares the positions of Labour and National using different documents on a summary economic and social policy left-right dimension.Footnote1 Irrespective of which documents are used, clear left-right differences between Labour and National are usually evident. The exception is 1990, when National’s television broadcast, but not its manifesto, was slightly to the left of both Labour’s television broadcast and Labour’s manifesto. As showed, National’s 1990 manifesto had promised to reduce welfare spending. However, the relatively moderate policy direction National sometimes signalled before the 1990 election and its ‘Decent Society’ election slogan fitted poorly with the sharp spending cuts, radical labour market deregulation, and privatisation policies National implemented after the 1990 election (James and McRobie Citation1993, 39–56; Boston and Dalziel Citation1992, iii).

An important reason for collecting data back to 1984 was that National’s 1984 position using manifesto data had unexpectedly been considerably to the right of National’s position at other elections (Gibbons Citation2000, 216–217, 208; Citation2011, 49, 52). Here National’s 1984 position is almost identical using its short manifesto, its television broadcast and its pre-election Speech from the Throne. National’s 1984 manifesto is still to the right of its manifesto or webpages at subsequent elections, but less so than previously. In addition, when compared to National’s broadcasts and speeches by party leaders at other elections, National’s 1984 position was not particularly right-wing. For National’s 1984 manifesto this is partly because a careful recoding resulted in sentences about the desirability of energy self-sufficiency being categorised as protectionism: positive, rather than as otherwise uncodable specific economic goals that had no left-right positional effects. The left-right dimension used here also includes Keynesian Demand Management references to the desirability of the government borrowing to maintain living standards, which had not previously been included, and these messages were particularly important in National’s 1984 policy statements.

Parties’ positions are often broadly similar at each election irrespective of the documents used. Labour’s short 1984 and 1987 manifestos were slightly more to the left than Labour’s full manifestos for these two elections, suggesting the number of policy commitments, rather than the policy direction indicated, were why Labour delayed the release of its full manifestos. None of Labour’s 1984 and 1987 policy statements predicted the increasingly radical economic policy direction Labour followed (James and McRobie Citation1993, 11–22), although Labour’s 1984 and 1987 Speeches from the Throne were noticeably more right-wing than its pre-election statements.

Labour’s 1990 positions were very similar, despite a leadership change just before the 1990 election. Even though its leader Mike Moore had unprecedented control over Labour’s 1993 manifesto (Harris Citation1993), Labour’s 1993 manifesto position was very similar to its television broadcast where Labour MPs outlined its policies. Irrespective of which policy document is used, Labour moved well to the left in 1996, when it was being challenged by the left-wing Alliance (see also ), and again in 2014, when David Cunliffe promised a left-wing policy direction (Vowles, Coffe, and Curtin Citation2017, 10). Labour’s brochures indicated a similar policy direction to other documents in 1996 and 1999, and again in 2017 and 2020, but were to the left of all other Labour policy documents in 2002 and 2005. In 2023, Labour’s campaign launch speech, in which Chris Hipkins announced a substantial increase in dental healthcare entitlements, was its most left-wing policy statement at the 2023 election.

National was comparatively right wing in 1999, under Jenny Shipley, and again in 2005, when Don Brash also forcefully advocated right-wing policies (James Citation2016, 168–169, 179, 217). Between 1993 and 1999 and since 2011 National has been more right-wing in pre-election broadcasts and speeches than in its manifesto or webpages. For instance, John Key’s speeches tended to discuss the need for winning, for welfare reform, for greater public sector efficiency, and for lower government spending. In contrast, National’s long webpages tended to be much blander, and to focus on spending promises. The biggest divergence was in 2014, when Key’s campaign launch focused on policies to encourage home ownership. This is different to the results found for Greece, where using speeches resulted in a centrist bias (Gemenis Citation2012, 598). From 1990 onwards, National’s Speeches from the Throne for the opening of parliament were invariably to the right of National’s position in its manifesto or webpages. The position of the 2023 Speech from the Throne indicates that the right-wing Act Party, which was one of National’s coalition partners, had a strong influence on the government’s programme.

broadens the analysis to include results for other political parties represented in Parliament, or have won over 4% of the vote, using print documents; and also television broadcasts up to 2014, followed by campaign opening speeches thereafter. The results reveal increasing polarisation from 1990, which preceded New Zealand’s 1996 switch to proportional representation.

The short-lived New Act Party was considerably further to the right in its 1984 television broadcast, where its leader strongly advocated free markets, than in its more cautious manifesto. For Social Credit, and for the left-wing Alliance and Progressives, and also for the Green Party, the choice of document usually makes little difference. However, the Alliance did not issue a manifesto in 1999, and the Alliance’s television broadcast was a more policy-focused document than its campaign opening speech. In addition, the Progressives were more centrist in 2005 using their broadcast than using print documents. For New Zealand First there is less movement using its manifesto or webpages, which at some elections has only been slightly revised, than using its highly programmatic television broadcasts. New Zealand First’s 2017 to 2023 campaign opening speeches show indicate it has been moving to the right on economic issues. The small centrist United Party (not shown here for reasons of clarity), which was represented in Parliament between 2005 and 2017, also moved between the left and right.

For the Act Party, its manifestos and webpages between 1999 and 2017 and in 2023 were well to the right of its broadcasts and campaign opening speeches. Act’s manifestos have consistently made more references to the need for lower government spending than its television broadcasts, as Act avoided discussing relatively extreme policies on television (Church Citation2000, 108). Act even shifted left of centre in 2017, when its speech by its leader (and sole MP), focused on improving the education system, albeit in a fairly right-wing way. The television broadcasts and leaders’ speeches therefore do not show consistent differences between National and Act, whereas the webpages do.

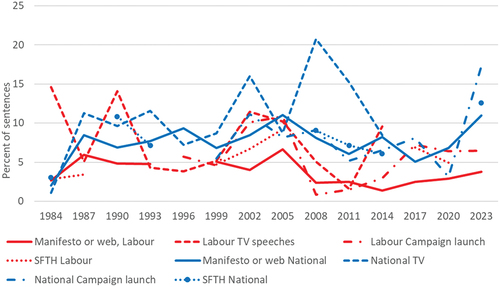

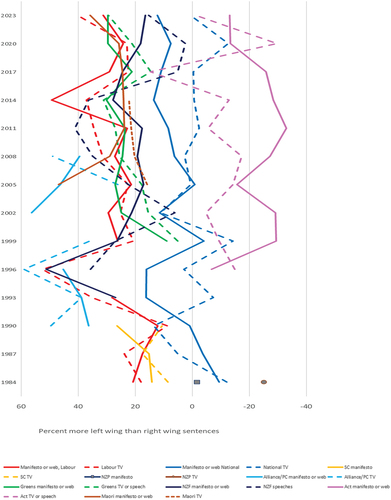

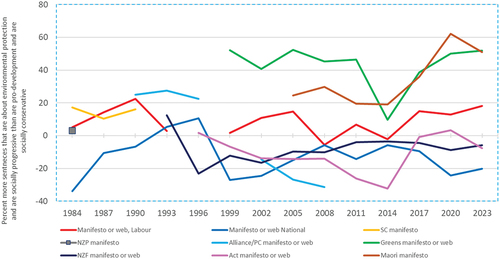

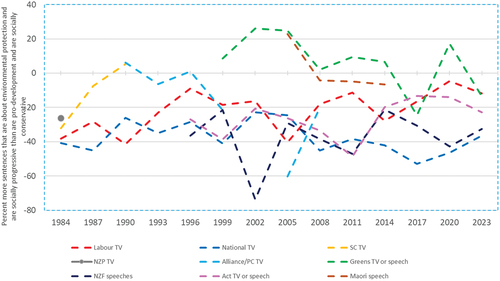

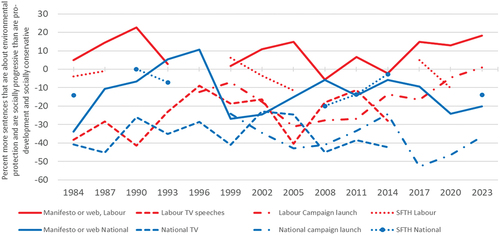

The socially conservatism and development versus environment and socially progressive dimension

Parties’ positions on a summary dimension for socially conservative, economic development, environmental protection, socially progressive and foreign policy topics are now evaluated.Footnote2 The results show the importance of the type of document used for these topics. Comparing manifestos and webpages, shows Labour is usually closer to the environment and socially progressive end than National. Parties’ campaign speeches are closer to the pro-development and social conservatism end, but again Labour is normally less towards the development, authority and social conservatism end than National is. The speeches seem to show more evidence of a gradual shift by Labour towards concern about the environment and socially progressive policies (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019, 87–94) than the manifestos and webpages.

Figure 20. National’s and Labour’s left-right positions on a socially conservatism and development versus environment and socially progressive dimension.

Looking at the results for all parties using print documents (), the Green Party has consistently been towards the environment and socially progressive end of the dimension than most other parties. The gap was smallest in 2014 when the Greens heavily emphasised the transformative power of technology and the need for more research and new infrastructure. Because of its strong focus on indigenous rights, Te Pāti Māori has also been strongly socially progressive. Since 1999, Labour has emphasised environmental and socially progressive themes next most. The positions of National, New Zealand First and Act have overlapped.

Using the television broadcasts and speeches () pulls all the parties towards the socially conservative and development end of the dimension. This happens even for the Green Party, whose broadcasts and speeches have emphasised New Zealand’s way of life and their party’s competency. However, apart from in 2017, when its campaign launch speech strongly focused on its competency, the Green Party have always been distinct from the other parties on this dimension. Using speeches, Labour is less distinct from the other parties. However, Labour has usually been more towards the environment and socially progressive end of this dimension than National and New Zealand First.

Conclusion

This article has compared New Zealand political parties’ policies between 1984 and 2023 using data derived from content analysis of election manifestos, webpages, television broadcasts, campaign opening speeches, brochures and speeches for the opening of parliament. Pre-election policy statements are important because they show voters what parties’ policies are, and reveal the policy direction voters can expect if a party forms a government, or becomes a coalition partner, after an election.

Irrespective of which documents are used, clear differences on a summary left-right dimension about economic policy, social services and labour groups were usually apparent between Labour and National. The only exception was the 1990 election when National’s television broadcast was to the left of both Labour’s television broadcast and Labour’s manifesto. National was consistently more centrist using data from long webpages than using data from its shorter television broadcasts and speeches by its leader for the five elections between 2011 and 2023. In contrast, Labour’s left-right position was usually similar in manifestos or webpages to its left-right position in television broadcasts and campaign speeches. However, Act was further to the right using print documents than in broadcasts and speeches, while New Zealand First’s position changed more using broadcasts and speeches. Whereas National’s 1984 manifesto was considerably further to the right than expected in previous analysis, after all the documents were recoded the left-right results for National in 1984 were much closer to what was expected.

There has been more overlap between Labour and National on issues like the environment and sustainability, development, social conservatism, indigenous rights, foreign policy, and political authority. However, when these issues are considered together, and the same types of documents are compared, Labour has usually been more towards the socially progressive end of this dimension. Irrespective of which document was used, the Green and Māori parties were almost always more towards the environment and socially progressive end of this dimension than other parties represented in Parliament.

However, political authority themes, were much higher in pre-election broadcasts and speeches than in manifestos and webpages. Sometimes socially conservative themes, such as national way of life and social harmony, were also higher in broadcasts and speeches than in print documents. In contrast, for the two main parties, references to agriculture and farmers, the environment and sustainability, policies to help Māori, and foreign policy, were higher in long manifestos and webpages than in shorter documents, where more prioritisation occurs. This means comparisons of policies for these topics over time need to use similar documents, insofar as is possible (Merz and Regel Citation2013, 163). When different documents are used the political authority category should be excluded from the left-right dimension (Gemenis Citation2012), and there are also good reasons for excluding this category whenever it dominates the content of some programmes (McDonald, Mendes Silvia, and Budge Citation2004, 15).

When resources are limited, focussing on coding relatively short pre-election policy statements may be necessary. Because there is more constraint over what is included, even when long documents have been coded often the author would use relatively short documents to analyse changes in Labour’s and National’s main priorities over time. In addition, it may sometimes be desirable to add the results for several short policy statements when a topic like defence is mentioned in one policy statement, but not another. Constructing measures of policy outcomes for New Zealand, similar to those that exist in countries like the United States (Erikson Citation2012, 45), would help show whether using shorter documents is the correct decision.

The ending of the television broadcasts after the 2014 election has meant a policy statement, albeit usually fairly brief, that the main parties usually took seriously is no longer available to voters and to researchers. New Zealand should consider requiring parties to publish pre-election programmes. A suitable length might be between 10 and 20 pages, with parties required to outline their priorities and the major policy changes they intend to make if elected. Governments could then be required to annually outline their policy and legislative agenda so that deviations from pre-election commitments could be reported upon.

It would be desirable to transcribe and code parties’ television broadcasts from earlier decades. Manifesto data shows Labour being very centrist in the 1970s and early 1980s, while National was also centrist at the 1972 and 1975 elections. Text from the broadcasts would be valuable for better understanding the growth of right-wing thinking within Labour. In addition, Robert Muldoon’s political messages before 1984 deserve further study. The extent to which Muldoon and Labour leader Norman Kirk used populist rhetoric could also be researched using the television broadcasts. Research comparing parties’ manifesto positions to party political broadcasts in other countries, such as the United Kingdom, would also be desirable, especially when parties’ manifestos have become very long. Similarly, in Australia the leaders’ speeches, which are often more than a dozen pages long, could be compared to the text of the webpages, which often contain more than a hundred pages of text.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Claire Robinson (Massey) for 1999 and 2002 transcripts of television broadcasts and Alitia Lynch (Chapman Archive, University of Auckland Library) for providing video of the broadcasts. When this article is published the transcripts of broadcasts will be archived at the Chapman archive. Thanks also to the anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Matthew Gibbons

Matthew Gibbons has been working on research projects on voting and non-voting and on social media at Victoria University of Wellington. He has also taught two undergraduate courses at Victoria. Matthew’s PhD was on election manifestos and government expenditure, and was made possible by a University of Waikato postgraduate scholarship.

Notes

1. The right end is support for a market economy (free enterprise, incentives, free trade) plus government efficiency and economic orthodoxy, plus welfare state limitation, education limitation, and labour groups negative. The left end is support for state intervention (market regulation, economic planning, corporatism, protectionism, economic controls and state ownership), plus social justice: economic, welfare state expansion, Keynesian demand management, education expansion, and labour groups positive.

2. The environment and socially progressive end is sustainability, the environment, culture, equality for minorities, traditional morality and way of life: negative, law and order: rehabilitation, peace and cooperation, freedom and democracy, decentralisation: positive, multiculturalism and Māori, and minorities. The development and socially conservative end is economic growth, infrastructure, political authority, social conservatism (which is positive references to national way of life, traditional morality, law and order and social harmony), multiculturalism: negative, foreign special relationships, and defence: positive. This dimension is similar to that used for studying British politics. See (Allen and Bara Citation2021).

References

- Allen, Nicholas, and Judith Bara. 2021. “Clear Blue Water? The 2019 Party Manifestos.” The Political Quarterly 92 (3): 531–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.13009.

- Ardern, Jacinda. 2021. “The Prime Minister’s Reflections - Campaigning in the Midst of a Pandemic.” In Politics in a Pandemic: Jacinda Ardern and New Zealand’s 2020 Election, edited by Stephen Levine, 71–75. Wellington: Victoria University Press.

- Benoit, Kenneth, Michael Laver, Will Lowe, and Slava Mikhaylov. 2012. “How to Scale Coded Text Units without Bias: A Response to Gemenis.” Electoral Studies 31 (3): 605–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.05.004.

- Benoit, Kenneth, Michael Laver, and Slava Mikhaylov. 2009. “Treating Words As Data with Error: Uncertainty in Text Statements of Policy Positions.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (2): 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00383.x.

- Boston, Jonathan, and Paul Dalziel. 1992. “Preface.” In The Decent Society? Essays in Response to National’s Economic and Social Policies, edited by Jonathan Boston and Paul Dalziel, iii–xii. Auckland: Oxford University Press.

- Budge, Ian. 2013. “Linking Uncertainty Measures to Document Selection and Coding.” In Mapping Policy Preferences from Texts III: Statistical Solutions for Manifesto Analysts, edited by Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, Ian Budge, Michael D. McDonald, and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, 131–145. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Budge, Ian. 2015. “Political Parties: Manifestoes.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, edited by James D. Wright, 417–420. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Budge, Ian, and Bara. Judith. 2001. “Introduction: Content Analysis and Political Texts.” In Mapping Policy Preferences: Estimates for Parties, Electors, and Governments 1945-1998, edited by Ian Budge, Hans-Dieter Klingemann, Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, and Eric Tanenbaum, 1–16. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Budge, Ian, Michael D. McDonald, and Thomas Meyer. 2013. “Validated Estimates versus Dodgy Adjustments: Focussing Excessivly on Error Distorts Results.” In Mapping Policy Preferences from Texts III: Statistical Solutions for Manifesto Analysts, edited by Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, Ian Budge, Michael D. McDonald, and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, 69–84. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Church, Stephen. 2000. “Lights, Camera, Election: The Television Campaign.” In Left Turn: The New Zealand General Election of 1999, edited by Jonathan Boston, Stephen Church, Stephen Levine, Elizabeth McLeay, and Nigel S. Roberts, 105–126. Wellington: Victoria University Press.

- Collins, Simon. 1990. “PM Unveils Labour Manifesto.” New Zealand Herald. Accessed October 12, 1990.

- Dunne, Peter. 2007. “United Future - Ironies of a Doomed Campaign.” In The Baubles of Office: The New Zealand General Election of 2005, edited by Stephen Levine and Nigel S. Roberts, 134–138. Welington: Victoria University Press.

- Electoral Commission. 2015. Report of the Electoral Commission on the 2014 General Election. Electoral Commission (Wellington). https://elections.nz/assets/2014-general-election/report-of-the-electoral-commission-on-the-2014-general-election.pdf.

- Erikson, Robert S. 2012. “Public Opinion at the Macro Level.” Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 141 (4): 35–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41721979.

- Gabel, Matthew J., and John D. Huber. 2000. “Putting Parties in Their Place: Inferring Party Left-Right Ideological Positions from Party Manifestos Data.” American Journal of Political Science 44 (1): 94–103. https://doi.org/10.2307/2669295.

- Gemenis, Kostas. 2012. “Proxy Documents As a Source of Measurement Error in the Comparative Manifestos Project.” Electoral Studies 31 (3): 594–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.01.002.

- Gemenis, Kostas. 2013. “What to Do (And Not to Do) with the Comparative Manifestos Project Data.” Political Studies 61 (1): 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12015.

- Gibbons, Matthew. 2000. “Election Programmes in New Zealand Politics, 1911-1996.” PhD, Politics Department, University of Waikato.

- Gibbons, Matthew. 2003/2024. An Annotated Bibliography of New Zealand Election Programmes Since 1905. University of Waikato (Hamilton). https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download;jsessionid=7FDF4404147E650BBC47E6DB0EF9AC9E?doi=10.1.1.198.3516&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Gibbons, Matthew. 2011. “New Zealand Political Parties’ Policies.” New Zealand Sociology 26 (1): 41–67. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.114699866489365.

- Gibbons, Matthew. 2017. “Government Expenditure in New Zealand Since 1935.” Policy Quarterly 13 (2): 56–64. https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/pq/article/view/4664/4148.

- Goldfinch, Shaun, and Daniel Malpass. 2007. “The Polish Shipyard: Myth, Economic History and Economic Policy Reform in New Zealand.” Australian Journal of Politics & History 53 (1): 118–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8497.2007.00446.x.

- Hansen, Martin Ejnar. 2008. “Back to the Archives? A Critique of the Danish Part of the Manifesto Dataset.” Scandinavian Political Studies 31 (2): 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2008.00202.x.

- Harris, Stephen. 1993. “Moore’s ‘Cash Box’ Creates Unease.” National Business Review. Accessed November 12, 1993. Newztext.

- Hubbard, Anthony. 1990. “Broken Promises.” New Zealand Listener. October 22, 18–21.

- Ivanusch, Christoph. 2024. “Where Do Parties Talk About What? Party Issue Salience Across Communication Channels.” West European Politics 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2024.2322234.

- James, Colin. 2016. National at 80: The Story of the New Zealand National Party. Auckland: Bateman.

- James, Colin, and Alan McRobie. 1993. Turning Point: The 1993 Election and Beyond. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books.

- Laakso, Markku, and Rein Taagepera. 1979. “‘Effective Number of Parties: A Measure with Application to West Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 12 (1): 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041407901200101.

- Laugesen, Ruth. 1996. “Detailed Manifesto Unlikely - Bolger.” Dominion, Newztext. Accessed June 4, 1996.

- Laver, Michael, and Ian Budge. 1992. “Measuring Policy Distances and Modelling Coalition Formation.” In Party Policy and Government Coalitions, edited by M. J. Laver and Ian Budge, 15–40. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Laver, Michael, and Sydney Elliot. 1987. “Northern Ireland 1921-1973: Party Manifestos and Platforms.” In Ideology, Strategy and Party Change: Spatial Analyses of Post-War Election Programmes in 19 Democracies, edited by Ian Budge, David Robertson, and Derek Hearl, 160–176. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Levine, Stephen, and Alan McRobie. 2002. From Muldoon to Lange: New Zealand Elections in the 1980s. Rangiora: MC Publishers.

- Lijphart, Arend. 2012. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. 2nd ed. New Haven, Connecticut, USA: Yale University Press.

- Manifesto Project. 2022. Manifesto Collection Guidelines. WZB (Berlin). https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/down/papers/Manifesto_Project_Collection_Guidelines.pdf.

- McDonald, Michael D., M. Mendes Silvia, and Ian Budge. 2004. “What are Elections For? Conferring the Median Mandate.” British Journal of Political Science 34 (1): 1–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4092397.

- McLeay, Elizabeth. 1994. “Policy Issues and the Policy Agenda.” In Double Decision: The 1993 Election and Referendum in New Zealand, edited by Jack Vowles and Peter Aimer, 37–68. Wellington: Department of Politics.

- Merz, Nicolas. 2018. The Manifesto-Media Link: How Mass Media Mediate Manifesto Messages. Berlin: Humboldt-Universität zu.

- Merz, Nicolas, and Sven Regel. 2013. “What Are Manifestos For? Selecting and Typing Documents in the Database.” In Mapping Policy Preferences from Texts III: Statistical Solutions for Manifesto Analysts, edited by Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, Ian Budge, Michael D. McDonald, and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, 146–168. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mulgan, Richard. 1978. “The Concept of Mandate in New Zealand Politics.” Political Science 30 (2): 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/003231877803000203.

- Mulgan, Richard. 1992. “The Elective Dictatorship in New Zealand.” In New Zealand Politics in Perspective, edited by Hyam Gold, 513–532. 3rd ed. Auckland: Longman Paul.

- Neill, Carol. 2008. “New Zealand’s Butter, Sheep Meat and Wool Exports to the EU-15 Since 1960.” In New Zealand and the European Union, edited by Matthew Gibbons, 13–33. Auckland, N.Z: Pearson.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2019. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- NZPA. 2008. “Maori Seats Policy ‘Not a Bottom Line’ for Nats - Key.” New Zealand Herald. Accessed October 16, 2008. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/maori-seats-policy-not-a-bottom-line-for-nats-key/PZH6I6FDCFAZ7HGLWWVH332BHA/.

- O’Neil, Andrea. 2014. “Beauty Pageants Great for Women - Minister.” Dominion Post. Accessed November 29, 2014. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/63676478/beauty-pageants-great-for-women—minister.

- Palmer, Geoffrey. 1992. New Zealand’s Constitution in Crisis. Dunedin: John McIndoe.

- Peacock, Colin. 2016. “Brace Yourself for Multimedia Political Persuasion.” Radio New Zealand. Accessed October 30, 2016. https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/mediawatch/audio/201821350/brace-yourself-for-multimedia-political-persuasion.

- Pearse, Hilary. 2000. “No Junk Mail: The Street-Level Campaign.” In Left Turn: The New Zealand General Election of 1999, edited by Jonathan Boston, Stephen Church, Stephen Levine, Elizabeth McLeay, and Nigel S. Roberts, 127–140. Wellington: Victoria University Press.

- Robinson, Claire. 2009. “‘Vote for Me’: Political Advertising.” In Informing Voters: Politics, Media and the New Zealand Election 2008, edited by Chris Rudd, Janine Hayward, and Geoffrey Craig, 73–89. Auckland: Pearson Education.

- Robinson, Claire. 2019. Promises, Promises: 80 Years of Wooing New Zealand Voters. Auckland: Massey University Press.

- Schelder, Andreas. 1998. “The Normative Force of Electoral Promises.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 10 (2): 191–214. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0951692898010002003.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. 2020. The Economy of Tomorrow: Recovering and Restructuring After Covid-19. Roosevelt Institute. https://business.columbia.edu/sites/default/files-efs/imce-uploads/Joseph_Stiglitz/RI_-RecoveringandStructuringAfterCOVID19_IssueBrief_202010.pdf.

- Stone, Andrew. 1990. “Booklet Directed at Undecided Voters.” New Zealand Herald. Accessed September 18, 1990.

- Thomson, Audrey. 2006. “Labour Escapes Charges on Pledge Card but Case Found.” New Zealand Herald. Accessed March 17, 2006. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/labour-escapes-charges-on-pledge-card-but-case-found/OTMRGAMRSAC6ZWBWBJCQDMWV6E/.

- Tunnah, Hannah. 2005. “Foreign Policy Slips Out Quietly on Party Website.” New Zealand Herald. Accessed June 2, 2005.

- Volkens, Andrea, and Nicolas Merz. 2018. “Are Programmatic Alternatives Disappearing? The Quality of Election Manifestos in 21 OECD Countries Since the 1950s.” In Democracy and Crisis: Challenges in Turbulent Times, edited by Wolfgang Merkel and Sascha Kneip, 71–95. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Vowles, Jack. 1990. “Nuclear Free New Zealand and Rogernomics: The Survival of a Labour Government.” Politics 25 (2): 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/00323269008402107.

- Vowles, Jack. 2020. “Populism and the 2017 Election - the Background.” In A Populist Exception: The 2017 New Zealand General Election, edited by Jack Vowles and Jennifer Curtin, 35–70. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Vowles, Jack, Peter Aimer, Helena Catt, Jim Lamare, and Raymond Miller. 1995. Towards Consensus? The 1993 Election in New Zealand and the Transition to Proportional Representation. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- Vowles, Jack, Hilde Coffe, and Jennifer Curtin. 2017. A Bark but No Bite: Inequality and the 2014 New Zealand General Election. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Werner, Annika, Onawa Lacewell, Andrea Volkens, Theres Matthieß, Lisa Zehtner, and Leila Van Rinsum. 2023. Manifesto Coding Instructions. WZB (Berlin). https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/down/papers/handbook_2021_version_5.pdf.

- Young, Audrey. 2014. “John Key: Dropping Maori Seats Would Mean ‘Hikois from Hell’.” New Zealand Herald. Accessed August 22, 2014. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/john-key-dropping-maori-seats-would-mean-hikois-from-hell/UGJT7GEENF2M2KF4FOGLSNMUQE/.

- Zulianello, Mattia. 2014. “Analyzing Party Competition Through the Comparative Manifesto Data: Some Theoretical and Methodological Considerations.” Quality & Quantity 48 (3): 1723–1737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-013-9870-0.