Abstract

Girls’ school participation has expanded considerably in the developing world over the last few decades, a phenomenon expected to have substantial consequences for reproductive behaviour. Using Demographic and Health Survey data from 43 countries, this paper examines trends and differentials in the mean ages at three critical life-cycle events for young women: first sexual intercourse, first marriage, and first birth. We measure the extent to which trends in the timing of these events are driven either by the changing educational composition of populations or by changes in behaviour within education groups. Mean ages have risen over time in all regions for all three events, except age at first sex in Latin America and the Caribbean. Results from a decomposition exercise indicate that increases in educational attainment, rather than trends within education groups, are primarily responsible for the overall trends. Possible explanations for these findings are discussed.

Introduction

A successful transition to adulthood includes adequate preparation for adult roles and the capacity to make informed decisions about the timing of key life events (Lloyd Citation2005). First sexual intercourse, first marriage, and first birth are among the most consequential of these events. Taking on the roles of sexual partner, spouse, and parent too early may undermine the success of this transition, jeopardize a young person’s health and well-being, and have deleterious effects on the health and well-being of her offspring (Lloyd Citation2005). In less-developed-country settings, where HIV is endemic and where young women suffer disproportionately from sexually transmitted infections (STIs), the earlier sex is initiated, the longer the exposure to the risk of infection. On average, the younger the age of a woman at marriage, the larger the age difference between spouses, the less agency women are reported to have within marriage, and the higher the likelihood of marital dissolution (Singh and Samara Citation1996; Mensch Citation2005). And finally, early childbirth, before achieving full physical maturity around age 16, is associated with a higher likelihood of maternal death (Blanc et al. Citation2013; Nove et al. Citation2014), infant death, and other poor child health outcomes (Finlay et al. Citation2011). Moreover, the timing of births has an effect on population growth. For all these reasons, there is considerable interest on the part of researchers and policymakers in trends that are the focus of this study: ages at first sex, marriage/union, and childbirth in the developing world.

The paper begins with a review of the literature on the impact of women’s schooling on fertility and on the timing of first sex, first marriage, and first birth. This is followed by a detailed empirical analysis of levels and trends in the ages at these life-cycle events, based on data collected by Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) since 1986 in 43 less developed countries in Asia and Northern Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and sub-Saharan Africa. The mean ages at events are estimated with a method that allows period-based measurements to provide more up-to-date results than the conventional cohort-based approach used in earlier studies. Girls’ school participation has expanded considerably in many of these countries over the last few decades, with substantial consequences for reproductive behaviour. We examine the extent to which trends in the timing of events are driven by changing educational attainment within countries—that is, the educational composition of the population—or by changes in behaviour within groups that share the same level of education. The discussion and conclusion summarize the main findings of this analysis.

Background

The effect of girls’ schooling on subsequent fertility

Over 35 years ago, Caldwell (Citation1980) argued that mass education—which, he asserted, altered traditional family production and family dynamics—was the dominant force behind fertility transitions. Since then an extensive demographic literature has documented and analysed the inverse association in the developing world between years of schooling attained by women and the number of children ever-born (Jejeebhoy Citation1995; Martin Citation1995; Ainsworth et al. Citation1996; Bledsoe et al. Citation1999). The magnitude of education differentials among women varies between countries and the relationship is not always monotonic (Jejeebhoy Citation1995; Bledsoe et al. Citation1999); for example, some narrowing appears to emerge as countries reach the end of the transition (Bongaarts Citation2003). Nevertheless, differences in fertility between the more and less educated are observed in nearly all countries. Researchers have discussed a number of mechanisms underlying the association between formal schooling of girls and subsequent fertility, fertility preferences, or both, although data are often lacking to support these assertions. A number of factors that underlie the negative gradient between education and fertility have been mentioned, including greater autonomy, exposure to new gender and childbearing norms, improved knowledge about behaviours that enhance the health of women and children, development of social capital to navigate health institutions, alteration of childbearing preferences, growth in women’s earning potential, and the concomitant rise in the opportunity cost of women’s time, assortative mating, and increased material aspirations (Jejeebhoy Citation1995; Subbarao and Raney Citation1995; Ainsworth et al. Citation1996; Appleton Citation1996; Bledsoe et al. Citation1999; Diamond et al. Citation1999; Lloyd and Mensch Citation1999; Basu Citation2002; Ferré Citation2009; Behrman Citation2015; Grant Citation2015). Literacy has also been said to provide the tools for learning and acquiring knowledge (Jejeebhoy Citation1995), thus improving women’s ability to understand and absorb family planning messages and to consider the desirability of a smaller family (Bledsoe and Cohen Citation1993). Most of the hypothesized effects are direct but some are indirect and work through, for example, improved child survival and delayed marriage, for which many of the mechanisms overlap with those listed above (Ainsworth et al. Citation1996).

Girls’ schooling and the timing of reproductive events

Recently, with the unparalleled growth in the population of young people, increasing attention has been devoted to identifying conditions for a successful transition to adulthood and the role of girls’ schooling in the timing of reproductive events (Lloyd Citation2005, Citation2010; Mensch et al. Citation2005; Clark and Mathur Citation2012; Grant Citation2015). DHS data indicate that girls who are enrolled in school are less likely to report initiating sex than their same-age counterparts who are not enrolled (Lloyd Citation2009). DHS data also indicate later ages at sexual initiation, first marriage, and childbearing among those with more years of schooling (Lloyd Citation2005). In the majority of less developed countries, schooling is considered incompatible with marriage and childbearing, so that those who remain in school during adolescence delay marriage and childbearing, and those who marry early drop out of school (Lloyd and Mensch Citation2008). These associations have led many to argue that increased schooling is the dominant force behind the observed rise in age at marriage (United Nations Dept. of Economic and Social Affairs Citation2002). However, a regression analysis of the amount of change in early marriage that might be expected, based on change in educational attainment from older to younger cohorts in 39 DHS countries, revealed that in 15 countries the observed change was lower than the expected change. In about half of these 15 countries, the probability of early marriage actually increased between cohorts despite the increase in schooling (Mensch et al. Citation2005). An earlier analysis of change in four Latin American countries from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s also concluded that increases in education during that period were not associated with later marriage, although improvements in education did account for a large proportion of observed fertility decline (Weinberger et al. Citation1989).

The endogeneity of schooling and reproductive behaviour

The question of whether the association between girls’ education and reproductive behaviour in the developing world is causal has generated considerable interest in the last few years. Are the observed differentials in reproductive behaviour between the better and less well educated a result of selectivity of those with higher grade attainment? Using data from sub-Saharan Africa, researchers have addressed the potential endogeneity of schooling (Ferré Citation2009; Behrman Citation2015; Glick et al. Citation2015; Grant Citation2015). One study found that the failure to address endogeneity led to ‘substantial overestimation’ of the effect of schooling on the timing of marriage and childbirth among young women in Madagascar, although a significant effect was still observed (Glick et al. Citation2015). Three studies have taken advantage of natural experiments in the form of policy reforms in order to ‘instrument’ for years of schooling, and two found that education still had significant effects on fertility timing (Kenya: Ferré Citation2009) and desired family size (Malawi, Uganda, and Ethiopia: Behrman Citation2015). The one exception is a study by Grant (Citation2015) that investigated the effect of the introduction of free primary education and subsequent expansion of secondary schooling in Malawi. These increases in girls’ education did not lead to a delay in age at first birth, which she argued may be because of poor and declining school quality with the large influx of students.

Declining school quality and reproductive behaviour

The situation in Malawi is unlikely to be unique and prompts consideration of whether the benefits of education for reproductive behaviour will be realized in countries where expansion of school participation is not accompanied by significant improvements in learning outcomes. Basu and Stephenson (Citation2005) observed that child survival was higher for mothers in India who did not complete primary school relative to mothers with no education; it would appear that even a small amount of schooling, likely insufficient to confer literacy, may yield advantages in providing skills to improve health. As Basu (Citation2002, p. 1780) has argued elsewhere, there may be benefits to school attendance ‘without there being much that is compellingly positive about the typical developing country schooling experience’. The question remains, however, whether the effects of girls’ education on reproductive behaviour that have been observed historically are compromised by the declining school quality that has accompanied the recent expansion of schooling in many less developed countries (Pritchett Citation2013). Will schooling, given low and perhaps declining quality, continue to have a dampening effect on marriage and fertility, and, if it does, are the observed effects a function of more women becoming educated or of a change in preferences, for example, diffusion of ideas regarding the negative consequences of child marriage and early childbearing?

Contributions of this analysis to the literature

The preceding summary of the current literature on the association between education and reproductive behaviour in the developing world sets the context for our analysis and raises important questions best answered by in-depth country analyses. We contribute to this extensive literature by investigating whether: (1) increases or decreases in age at the time of reproductive events are observed in recent surveys and (2) if so, to what extent those changes are associated with shifts in the educational composition of the population of females, and to what extent they are associated with alteration in behaviour within education groups. Given that girls’ education has been promoted as the priority focus for twenty-first-century population policy (Lutz Citation2014), an examination of the contribution of girls’ schooling to recent changes in the timing of first sex, marriage, and childbearing is warranted.

Data and methods

The primary sources of data for this study were DHS conducted in less developed countries since 1986. One of the distinguishing characteristics of the DHS is the comparability of the questionnaires. We included in the analysis data from countries with nationally representative surveys covering at least two timepoints; this resulted in data from 43 countries in Asia and Northern Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and sub-Saharan Africa. To minimize sampling error in the estimates, we excluded surveys with sample sizes of fewer than 3,000 currently married women. The threshold of 3,000 was selected (somewhat arbitrarily) to minimize the loss of countries from the study while still excluding potential outliers. We also excluded countries with a population size of less than 2 million in 2000 and countries with inter-survey intervals of five or fewer years. Several of the smallest countries and island nations are outliers in our analyses for reasons that are not entirely clear, but high migration among young adults could be a factor. Short inter-survey intervals produce unstable trend estimates. If a country had a first survey that did not collect information on the timing of first sex, the next available survey with such data was selected.

The following countries were included in the analysis:

Asia and Northern Africa: Bangladesh, Cambodia, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Jordan, Morocco, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Turkey.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Peru.

Eastern and Southern Africa: Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Middle and Western Africa: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Togo.

In parts of the results and discussion, the latter two groups are combined and referred to as sub-Saharan Africa. Details of the survey years are provided in Appendix A.

For each of the surveys we estimated the period mean ages at first sex, first marriage, and first birth for the five years before the date of the survey, by highest level of education attended (i.e., no schooling, primary, and secondary or higher). (Throughout this study the term ‘marriage’ includes consensual union.) The method for calculating these mean ages is described in Bongaarts and Blanc (Citation2015) and summarized in Appendix B. The period mean age at a life-cycle event is defined as the mean age at which women would experience the event if they lived through the reproductive years having the age-specific event rates observed in a particular period. The calculation of the mean uses five-year age-specific rates of events as reported by female respondents in the DHS. This general approach is widely used to calculate current mean ages at first birth in countries with vital statistics (Human Fertility Database Citation2015) but is not used in country reports published by the DHS. Instead, DHS reports provide median ages at past events as reported by women of different current ages. These cohort medians have the advantage of being available for all DHS surveys but there are also drawbacks: (1) the median refers to past experience of cohorts and is therefore not as current as is preferable for many analytic purposes; (2) the retrospective reporting of the date of life-cycle events may suffer from recall errors that are likely to increase as time since the event increases; and (3) the cohort median as calculated by DHS is not independent of the quantum of first events and can change over time, even if the mean is constant. For these reasons, we prefer the period mean as our primary indicator of the timing of first birth, marriage, and sex. Regional means are unweighted averages of country means so that each country is given equal weight.

Limitations

Our analysis has several limitations. First, the number of countries included in each region ranged from eight in Latin America and the Caribbean to 14 in Middle and Western Africa. The countries for which we had data are not necessarily representative of their regions. The proportion of the regional population covered by these countries is 90 per cent in Middle and Western Africa, 75 per cent in Eastern and Southern Africa, 74 per cent in Asia and Northern Africa, and 54 per cent in Latin America and the Caribbean. Second, several countries included in the analysis had not had a very recent DHS survey. The most recent survey took place on average in 2010 but the range is from 1996 to 2014. It is possible that if we had more recent data, particularly for Latin America, and could include more of the populous countries (e.g., Mexico and Argentina), the results would be somewhat different. Third, the number of years of schooling represented by the primary or secondary level varies among countries. Finally, the aggregate analyses mask important country trends and our general explanations for observed aggregate trends, by design, may not reflect particular country experiences.

Results: mean ages at first sex, marriage, and birth

Levels

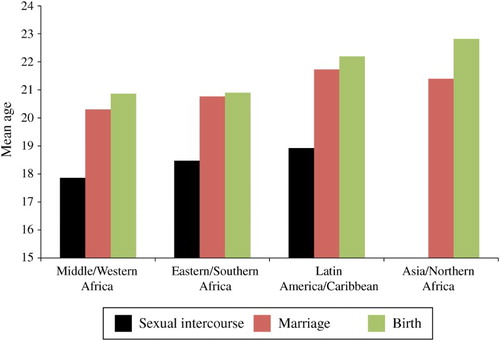

plots the unweighted regional averages for the country-level means of each of the three life-cycle events: first sex, first marriage, and first birth as estimated from the most recent DHS survey (c.2010) in 43 countries. Substantial regional differences are apparent, with countries in Middle and Western Africa having the lowest average values (17.9, 20.3, and 20.9 years for these events, respectively), and Eastern and Southern Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean, having intermediate values for first sex and birth. Latin America and the Caribbean had the highest age at first marriage (21.7) and Asia and Northern Africa the highest age at first birth (22.8). The average age at first sex in Asia and Northern Africa was not available because in several of the countries in this region the question about first sex was not included in surveys.

Figure 1 Mean ages at first sex, first marriage, and first birth for women, averages by world region, c.2010

The time between the average ages at first sex and first marriage was around two and a half years in sub-Saharan Africa and in Latin America and the Caribbean, indicating a substantial prevalence of premarital sex. The difference between the average ages at first marriage and first birth ranged from 0.1 years in Eastern and Southern Africa to 1.4 years in Asia and Northern Africa. It should be noted that the differences in intervals between average ages at successive events are not equal to the average interval between these events at the individual level, because some women who have sex never marry and some who marry never have a child.

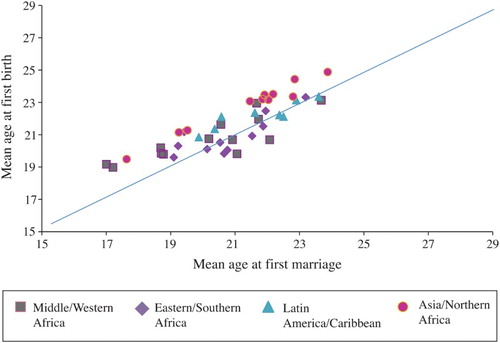

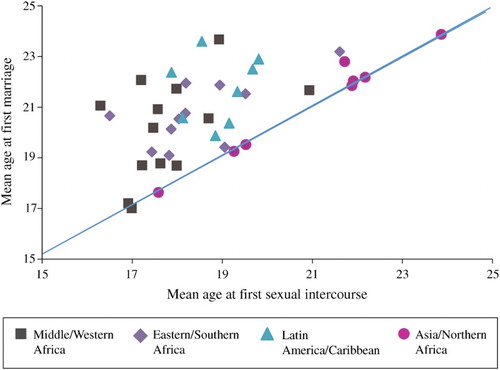

The averages plotted in conceal considerable variation among country estimates. The figure also gives no indication of the correlation between means of successive events. To examine these issues, plots the mean age at first marriage against the mean age at first sex for individual countries. A positive correlation (r = 0.58) exists between these variables, with the diagonal line representing the points at which the means are equal. It is noteworthy that in all but one country the mean age at marriage was either equal to or greater than the mean age at first sex. The difference between the mean age at sex and marriage reached a high of five years in Haiti, where premarital sex was common and marriage was late.

Figure 2 Mean age at first marriage by mean age at first sex, women in 40 countries, c.2010

shows a strong correlation (r = 0.84) between country mean ages at first birth and first marriage. The majority of countries fall above the diagonal line, which indicates that the mean age at birth is higher than the mean age at first marriage. However, a substantial number show the reverse, which is expected in countries with premarital childbearing.

Trends

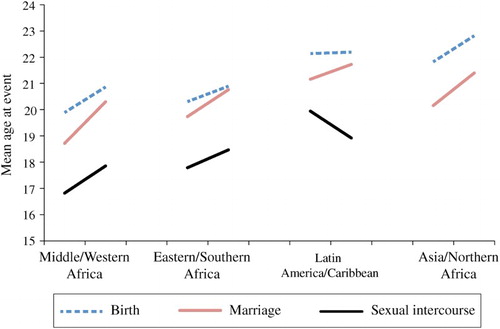

To examine trends in the various indicators, we compared the values estimated for the most recent survey with those observed at the first available survey. On average the most recent surveys occurred in 2010 and the first surveys in 1993, thus giving an average interval between surveys of 17 years. (The first and last surveys in some countries deviate significantly from the average. For example, the first and last surveys in Brazil were conducted in 1986 and 1996, respectively.) As shown in , the regional mean ages at reproductive events generally rose between c.1993 and c.2010. In particular, the mean ages at first sex, first marriage, and first birth all rose in sub-Saharan Africa, as they did for first marriage and first birth in Asia and Northern Africa. (This observation applies to the regional averages of country values, and not necessarily to every individual country.) In contrast, in Latin America and the Caribbean, the timing of first birth did not change significantly and the regional mean age at first sex declined substantially. This decline occurred in seven out of the eight Latin American and Caribbean countries.

Figure 4 Trends in mean ages at first sex, first marriage, and first birth for women, by world region, c.1993–2010

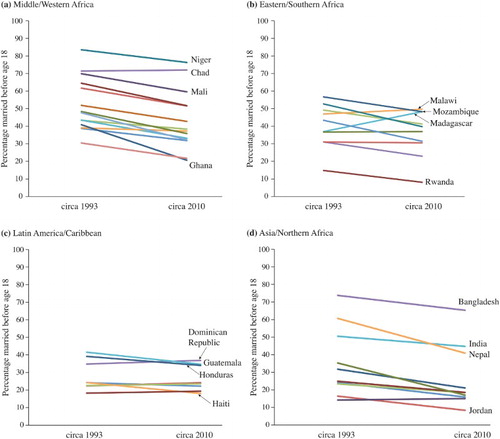

The upward trends in all regional mean ages at first marriage suggest that the prevalence of child marriage was declining. This inference is examined in , which plots the trend between c.1993 and c.2010 in the percentage of women aged 20–24 who married before age 18, that is, who were married as children. Several conclusions can be drawn. First, child marriage remained very common in parts of Middle and Western Africa in 2010, with the highest values in Niger, Chad, and Mali ((a)). In Asia and Northern Africa, child marriage was high in Bangladesh, Nepal, and India ((d)). Second, the prevalence of child marriage declined in 34 countries, but rose in nine countries (e.g., Malawi and Madagascar in (b)). Third, the pace of decline between c.1993 and c.2010 was typically rather slow. Unless this pace accelerates, child marriage will remain widespread in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia for the next few decades.

Results: the role of education

Trends in education

Since the early 1990s, substantial investments have been made in achieving universal primary education and gender parity in education, with investment accelerating after the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals in 2000. Enrolment in primary school has increased rapidly in many regions of the world and the gender gap has narrowed, although educational attainment levels still favour males, especially at secondary and higher levels (United Nations Dept. of Economic and Social Affairs Citation2010). Levels of adult literacy have increased since 1990 in all developing regions; for example, the percentage literate among women in sub-Saharan Africa rose from 43 to 53 per cent between 1990 and 2008 and from 34 to 51 per cent in Southern and Western Asia. However, the proportion of all illiterate adults that are women has remained the same at approximately two-thirds, even as the illiterate population has declined (UNESCO Institute for Statistics Citation2010).

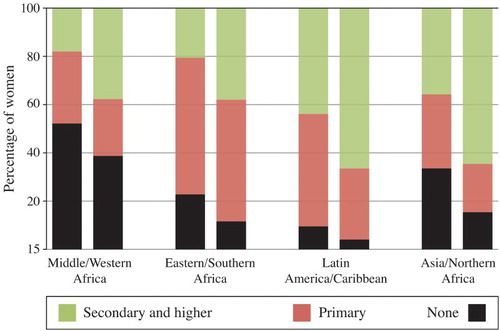

shows the shift in the educational distribution of women at first birth between c.1993 and c.2010 in the 43 countries included in our analysis. (The educational distribution by age is weighted by the age distribution of first births in the five years preceding the survey, because education levels vary considerably with age, younger cohorts having higher levels than older cohorts.) In all regions, the change was strongly positive. By c.2010, in all regions except Middle and Western Africa, fewer than one in five women had received no education; in Middle and Western Africa 39 per cent of women were still without any formal schooling c.2010. In Latin America and the Caribbean and in Asia and Northern Africa, almost two-thirds of women had achieved at least some secondary education c.2010, whereas less than 45 per cent had any secondary education in the early 1990s.

Figure 6 Educational distribution of women at age of first birth, by world region, c.1993–2010

Education differentials

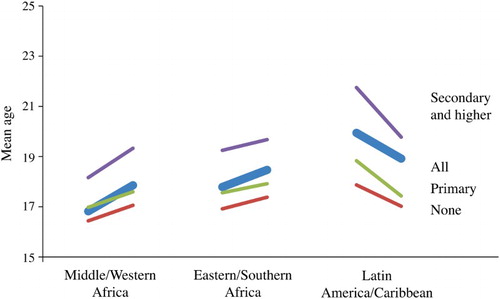

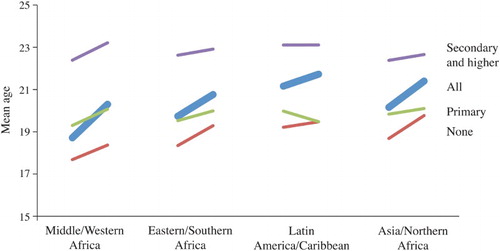

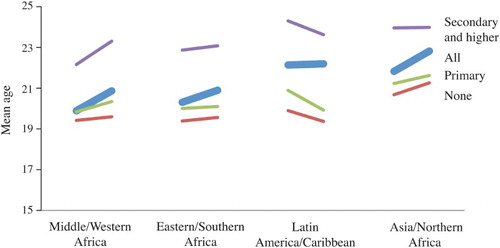

Trends in mean age at event by region and by highest level of education attended are plotted in . These results confirm the expected correlation with education; in every region, for each of the three events, and at both points in time, a higher level of education was associated with a higher mean age. Overall, the difference in mean age between those with secondary and those with primary education was much greater than the difference between women with primary and those with no education.

Figure 7 Trends in mean age at first sex by world region, for all women and by education level, c.1993–2010

Figure 8 Trends in mean age at first marriage by world region, for all women and by education level, c.1993–2010

Figure 9 Trends in mean age at first birth by world region, for all women and by education level, c.1993–2010

Another key finding is that the trends for all education groups together (represented by thicker lines on the figures) had steeper positive slopes (or less negative slopes) than the slopes of the education-specific trends. For example, the mean age at first birth changed little over this period for Latin America and the Caribbean in the aggregate, but the trends for the three education-specific means in this region were all downward. The explanation for this finding is that education levels have risen over time in all countries and regions. As a result, the weight given to the more highly educated groups in the calculation of the overall mean rose over time, and the weight for the less well educated groups declined.

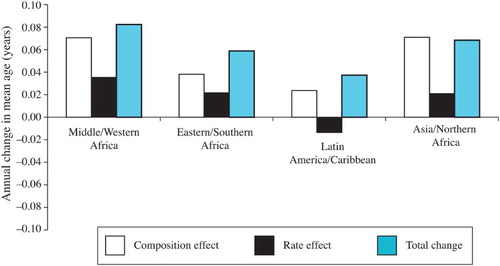

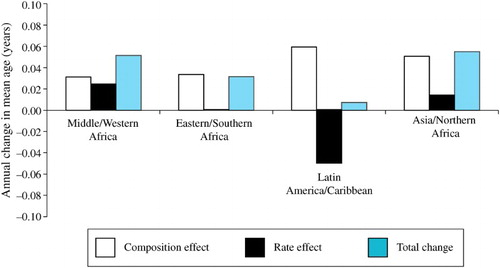

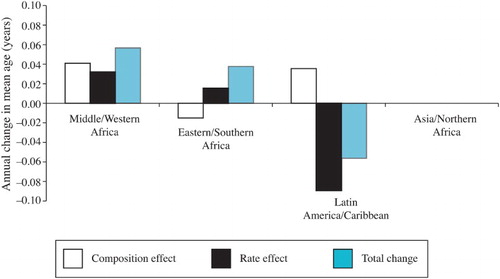

Decomposition of trends in effect of education

The overall trend in the mean age at an event has two distinct components:

The ‘composition’ effect refers to the impact of improvements in educational attainment. These improvements increase the size of the more highly educated groups and reduce the size of the less well educated groups thus raising the average pace of increase in the age at an event because higher levels of education are associated with a higher age at the event.

The ‘rate’ effect refers to trends in the education-specific means. As shown in , education-specific trends in the mean ages at events varied among regions; they tended to rise in sub-Saharan Africa and in Asia and Northern Africa, and to decline in Latin America and the Caribbean.

To quantify the role of these two factors, we undertook a decomposition exercise, which is the same as the one used by Weinberger et al. (Citation1989). The composition effect was estimated by holding education-specific means constant while allowing the educational composition to evolve as observed. The rate effect was estimated by holding educational composition constant while allowing the education-specific means to evolve as observed. The difference between the sum of these two components and the observed change is the ‘interaction’ effect, which will not be examined here.

Results are presented in . For each event and for each of the regions, three bars are presented. The white bar measures the composition effect and the hatched bar the rate effect. The black bar shows the observed increase or decrease in the mean. The main finding from this analysis is that the composition effect was positive for all three events in all regions (except for age at first sex in Eastern/Southern Africa) for which data were available. This is as expected, given the universal improvements in education levels in the large majority of less developed countries in recent decades. In contrast, the rate effect varied in size and direction, as expected from . This effect was largely positive in sub-Saharan Africa and in Asia and Northern Africa, but negative in Latin America and the Caribbean. The composition effect dominated the rate effect for changes in first birth and first marriage.

Figure 10 Annual change in mean age at first sex by world region, decomposed, c.1993–2010

Discussion and conclusion

At the time of the most recent DHS surveys (c.2010), the mean ages at first birth, first marriage, and first sex varied significantly by region, with events occurring at an earlier age in sub-Saharan Africa than in Latin America and the Caribbean or Asia and Northern Africa. For example, the average age at first birth was 20.9 years in Middle and Western Africa and in Eastern and Southern Africa, while it was 22.2 and 22.8 years in Latin America and the Caribbean and in Asia and Northern Africa, respectively. These differences are expected, given that on most development indicators sub-Saharan African countries typically score lower than elsewhere.

Our examination of trends in the mean ages at life-cycle events between c.1993 and c.2010 also showed significant differences between regions. In sub-Saharan Africa and in Asia and Northern Africa, the mean ages at first sex, first marriage, and first birth all rose during this period. These findings are as expected with rising levels of education. In contrast, in Latin America and the Caribbean the mean age at first birth remained constant and the mean age at first sex declined. We can only speculate why this region differed, but the combination of increasing globalization and the declining influence of the Catholic Church (which disapproves of premarital sex) are likely factors. As expected, the upward trends in age at marriage in all regions were associated with declines in child marriage. Although it remained high in some places, the prevalence of child marriage fell in all but nine of the 43 countries in our analysis.

In all regions, the average age at first birth was higher than the average age at first marriage, which in turn was higher than the average age at first sex. (This average ordering of life-cycle events does not necessarily hold for individual countries or for individual women, because sexual initiation can occur before, at the time of, or after marriage, and birth can precede marriage.) The substantial gap between age at first sex and age at first marriage in sub-Saharan Africa and in Latin America and the Caribbean indicates a high prevalence of premarital sex. Furthermore, the gap grew over time, suggesting a change in the context of sexual initiation. This trend may reflect a rising period at risk of premarital sex, as marriage is increasingly delayed, as well as to greater social tolerance of this behaviour and wider availability and use of contraception (Mensch et al. Citation2006). In contrast, the gap between ages at first marriage and first birth in these regions narrowed over time, indirect evidence of an increase in premarital conceptions, births, or both. It might also be the case that women who marry later are under increasing pressure by family members to prove their fertility. But the fact that the increase in age at first birth paralleled the increase in age at marriage in Asian and Northern African countries, where premarital sex is not thought to be common, suggests that premarital childbearing and not the pressure to have a child explains the narrowing of the gap between marriage and first birth in other regions.

In all regions, the level of girls’ education was positively associated with the timing of reproductive events. Among women who had attended secondary school, the mean ages at first birth and first marriage were typically several years higher than among women with primary education alone. In contrast the differences between women who had attended primary school and women with no education were mostly less than one year, indicating that secondary education had a more powerful effect on the timing of events than primary education. This finding may be explained by the selectivity of those who attend secondary school, as well as the fact that ages at first sex, marriage, and birth may overlap with, and therefore compete with, the age of participation in secondary education more than with primary education.

The preceding discussion focused on regional patterns in the timing of reproductive events. Although a full analysis of country-specific estimates is beyond the scope of this paper, a few results are noteworthy (while keeping in mind that trends in individual countries are affected more severely by sampling and reporting errors). The average pace of increase in the mean age at first birth was 0.04 years per annum, but country-level changes ranged from highs of 0.12 in Senegal, 0.11 in Ghana, and 0.10 in Jordan and Morocco, to a slight decrease in Chad, the DRC, Malawi, the Philippines, Brazil, and Colombia. For age at marriage the average pace of increase in all countries in the analysis was 0.06 years per annum, substantially higher than the pace for age at first birth. In twelve countries, the pace of increase in the mean age at first marriage was 0.10 years per annum or higher, which translates into a one-year increase every decade. Declines in the average age at marriage were observed in five of the 43 countries.

The degree of correlation between trends in girls’ education and trends in the ages at reproductive events also varied substantially among countries. For example, there was a rapid expansion of education in Ethiopia between 2000 and 2011, with the proportion of women with at least primary education rising from 34 to 67 per cent (about three percentage points annually). During the same period, the mean age at first birth increased by only a modest 0.03 years per annum. The age at first birth increased by approximately the same annual amount in Burkina Faso, Egypt, Mali, Mozambique, and Uganda, despite the proportion of women with at least primary education rising only about a third as much as in Ethiopia (one percentage point or less annually). Given the substantial improvement in education among women in Ethiopia, a larger shift in age at first birth would be expected. In Bangladesh and Nepal large improvements in education levels were also accompanied by lower than expected increases in age at first birth.

Over the roughly 17 years covered by this analysis, sizeable improvements in the educational attainment of women of reproductive age were observed. The impact of educational improvements on the timing of life-cycle events was examined with a decomposition exercise. The results indicate that in sub-Saharan Africa and in Asia and Northern Africa the changes in timing of first marriage and first birth overall were primarily a result of changes in the educational composition of the population of females (the ‘composition’ effect) and to a lesser extent changes in timing within categories of education (the ‘rate’ effect). This suggests that, even in the absence of changes in behaviour within education groups, age at first marriage and first birth would have increased.

In Latin America and the Caribbean (as represented by the eight countries in the analysis) the results were less straightforward. For the time interval we analysed, the average age at first sex decreased by almost a year, the age at marriage increased by less than a year, and the age at first birth remained constant. The positive effects of shifts in the education distribution on the average ages at marriage and first birth were almost cancelled out by the negative effects of decreases within education categories. For mean age at first sex, the negative rate effect was substantially greater than the positive composition effect. The Latin American experience suggests that it is difficult to speculate how future increases in educational attainment might affect the timing of early reproductive events.

The variability in trends across regions and countries and in the composition and rate effects of these trends is linked to differential changes in four factors. The first is the rapidity with which education levels have altered. In countries where education levels have increased markedly over a short period, one would expect more rapid change in the timing of early life-cycle events. Next is the effect of selectivity; as education becomes more widespread, those with higher levels of schooling are not as select a group as in the past and therefore may be more resistant to changes in reproductive behaviour. In addition, the group with no education becomes increasingly selective of those with lower socio-economic status. Third, the rate effect is influenced by norms that are altered not just by increased schooling but also as a result of other secular changes, such as the economy or the political context.

Finally, there is the attenuating effect of declining school quality (Grant Citation2015). As noted earlier, the rapid expansion of girls’ education over the last few decades has not translated into substantially improved learning outcomes in many settings (Riddell Citation2003; Pritchett Citation2013), which may reduce the transformative effect of education on the timing of reproductive events. If, however, the association between increased schooling and reproductive behaviour is in part because of a modification of attitudes and autonomy resulting from exposure to school, then continued changes in the educational composition of the population, particularly in Africa and Asia, will likely result in a continued rise in age at marriage and at first birth, even if academic skills at a particular grade level deteriorate somewhat over time.

Notes

1 John Bongaarts, Barbara S. Mensch, and Ann K. Blanc are all at the Population Council, New York. Please direct all correspondence to John Bongaarts, Population Council, One Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USA; or by e-mail at: [email protected]

2 This research was supported by a grant from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation to the Population Council. The authors are grateful to Katharine McCarthy and Barbara Miller for assistance in analysing data and preparing this manuscript.

References

- Ainsworth, Martha, Kathleen Beegle, and Andrew Nyamete. 1996. The impact of women's schooling on fertility and contraceptive use: a study of fourteen sub-Saharan African countries, World Bank Economic Review 10(1): 85–122. doi: 10.1093/wber/10.1.85

- Appleton, Simon. 1996. How does female education affect fertility? A structural model for the Côte d'Ivoire, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 58(1): 139–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0084.1996.mp58001007.x

- Basu, Alaka M. 2002. Why does education lead to lower fertility? A critical review of some of the possibilities, World Development 30(10): 1779–1790. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00072-4

- Basu, A. and R. Stephenson. 2005. Low levels of maternal education and the proximate determinants of childhood mortality: a little learning is not a dangerous thing, Social Science and Medicine 60: 2011–2023. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.057

- Behrman, Julia Andrea. 2015. Does schooling affect women's desired fertility? Evidence from Malawi, Uganda, and Ethiopia, Demography 52: 787–809. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0392-3

- Blanc, Ann K., William Winfrey, and John Ross. 2013. New findings for maternal mortality age patterns: aggregated results for 38 countries, PLoS ONE 8(4): E59864–00. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059864

- Bledsoe, Caroline H. and Barney Cohen. 1993. Social Dynamics of Adolescent Fertility in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Bledsoe, Caroline H., Jennifer A. Johnson-Kuhn, and John G. Haaga. 1999. Introduction, in C. H. Bledsoe, J. B. Casterline, J. A. Johnson-Kuhn, and J. G. Haaga (Eds.), Critical Perspectives on Schooling and Fertility in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, pp. 1–22.

- Bongaarts, John. 2003. Completing the fertility transition in the developing world: the role of educational differences and fertility preferences, Population Studies 57(3): 321–335. doi: 10.1080/0032472032000137835

- Bongaarts, John and Ann K. Blanc. 2015. Estimating the current mean age of mothers at the birth of their first child from household surveys, Population Health Metrics 13(25): Open Access (6 pages).

- Caldwell, John. 1980. Mass education as a determinant of the timing of fertility decline, Population and Development Review 6(2): 225–255. doi: 10.2307/1972729

- Clark, Shelley and Rohini Mathur. 2012. Dating, sex, and schooling in urban Kenya, Studies in Family Planning 43(3): 161–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00315.x

- Diamond, Ian, Margaret Newby, and Sarah Varle. 1999. Female education and fertility: examining the links, in C. Bledsoe, J. Casterline, J. Johnson-Kuhn, and J. Haaga (Eds.), Critical Perspectives on Schooling and Fertility in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, pp. 23–48.

- Ferré, Céline. 2009. Age at First Child: Does Education delay Fertility Timing? Policy Research Working Paper 4833. Washington, DC: World Bank Human Development Division, South Asia Region.

- Finlay, Jocelyn E., Emre Özaltin, and David Canning. 2011. The association of maternal age with infant mortality, child anthropometric failure, diarrhoea, and anaemia for first births: evidence from 55 low- and middle-income countries, BMJ Open 1(2): e000226. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000226

- Glick, Peter, Christopher Handy, and David E. Sahn. 2015. Schooling, marriage, and age at first birth in Madagascar, Population Studies 69(2): 219–236. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2015.1053513

- Grant, Monica J. 2015. The demographic promise of expanded female education: trends in the age at first birth in Malawi, Population and Development Review 41(3): 409–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00066.x

- Human Fertility Database. 2015. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany) and Vienna Institute of Demography (Austria). Available www.humanfertility.org (accessed: 16 December 2015).

- Jejeebhoy, Shireen. 1995. Women's Education, Autonomy, and Reproductive Behaviour: Experience from Developing Countries. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Lloyd, Cynthia B. and Barbara S. Mensch. 1999. Implications of formal schooling for girls’ transitions to adulthood in developing countries, in C. Bledsoe, J. B. Casterline, J. A. Johnson-Kuhn, and J. G. Haaga (Eds.), Critical Perspectives on Schooling and Fertility in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, pp. 80–104.

- Lloyd, Cynthia B. 2005. Growing Up Global: The Changing Transitions to Adulthood in Developing Countries. Panel on Transitions to Adulthood in Developing Countries. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Lloyd, Cynthia B. and Barbara S. Mensch. 2008. Marriage and childbirth as factors in dropping out from school: an analysis of DHS data from sub-Saharan Africa, Population Studies 62(1): 1–13. doi: 10.1080/00324720701810840

- Lloyd, Cynthia B. 2009. New Lessons: The Power of educating Adolescent Girls (A Girls Count Report on Adolescent Girls). New York: Population Council.

- Lloyd, Cynthia B. 2010. The role of schools in promoting sexual and reproductive health among adolescents in developing countries, in S. Malarcher (Ed.), Social Determinants of Sexual and Reproductive Health: Informing Future Research and Programme Implementation. Geneva: World Health Organisation, pp. 113–131.

- Lutz, Wolfgang. 2014. A population policy rationale for the twenty-first century, Population and Development Review 40: 527–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2014.00696.x

- Martin, Teresa Castro. 1995. Women's education and fertility: results from 26 Demographic and Health Surveys, Studies in Family Planning 26(4): 187–202. doi: 10.2307/2137845

- Mensch, Barbara S. 2005. The transition to marriage, in C. B. Lloyd (Ed.), Growing up Global: The Changing Transitions to Adulthood in Developing Countries. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, pp. 416–505.

- Mensch, Barbara S., Susheela Singh, and John B. Casterline. 2005. Trends in the timing of first marriage among men and women in the developing world, in C. B. Lloyd, J. R. Behrman, N. P. Stromquist, and B. Cohen (Eds.), The Changing Transitions to Adulthood in Developing Countries: Selected Studies. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, pp. 118–171.

- Mensch, Barbara S., Monica J. Grant, and Ann K. Blanc. 2006. The changing context of sexual initiation in sub-Saharan Africa, Population and Development Review 32(4): 699–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2006.00147.x

- Nove, Andrea, Zoe Matthews, and Alma Virginia Camacho. 2014. Maternal mortality in adolescents compared with women of other ages: evidence from 144 countries, Lancet Global Health 2: ( E155).

- Pritchett, Lant. 2013. The Rebirth of Education: Schooling ain't Learning. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

- Riddell, A. R. 2003. The introduction of free primary education in sub-Saharan Africa. Paper commissioned for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2003/4, The Leap to Equality.

- Singh, Susheela and Renee Samara. 1996. Early marriage among women in developing countries, International Family Planning Perspectives 22(4): 148–157. doi: 10.2307/2950812

- Subbarao, K. and Laura Raney. 1995. Social gains from female education: a cross-national study, Economic Development and Cultural Change 44(1): 105–128. doi: 10.1086/452202

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2010. Global Education Digest 2010: Comparing Education Statistics across the World. Quebec: UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

- United Nations Dept. of Economic and Social Affairs. 2002. ‘Concise Report on World Population Monitoring 2002: Reproductive Rights and Reproductive Health with Special Reference to Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS). Report of the Secretary General (E/CN.9/2002/2),’ Paper presented at 35th Session, Commission on Population and Devlopment. New York, 1–5 April.

- United Nations Dept. of Economic and Social Affairs. 2010. The World’s Women 2010: Trends and Statistics. New York: United Nations.

- Weinberger, Mary Beth, Cynthia Lloyd, and Ann Klimas Blanc. 1989. Women’s education and fertility: a decade of change in four Latin American Countries, International Family Planning Perspectives 15(1): 4–14. doi: 10.2307/2133273

Appendix A: Demographic and health survey countries and years

Appendix B: Estimating the period mean ages at life-cycle events

The method for estimating the period mean ages at life-cycle events (such as first birth, first marriage, and first sex) from DHS surveys follows Bongaarts and Blanc (Citation2015). In the absence of events before age 15 and above age 44(B1) where M(t) = average age at the event in period t, b(a,t) = age-specific event rate at age a in period t (events per 1,000 women).

In countries where large numbers of events are recorded (e.g., from vital registration), event rates are available by single age and single year. As a result, annual estimates of M(t) can be obtained. In contrast, in applications of this equation to DHS surveys, samples of events in single years are relatively small. To obtain robust estimates of the mean ages at events for a survey, we calculated b(a,t) by single year of age for a period of five years before each survey. In addition, we excluded surveys with sample sizes of currently married women below 3,000 to minimize sampling errors. The ages included in equation (B1) were from 15 to 44. The upper age was set at 44 years because in a few countries no data were available for higher ages. Moreover, the incidence of first sex, marriage, and births at higher ages was negligible in the countries included in this analysis. Equation (B1) uses a minimum age of 15 years because respondents under age 15 are not included in DHS surveys. Unfortunately, the incidence of events under age 15 was not negligible in a number of countries. An adjustment to equation (B1) was therefore needed to account for the occurrence of events below age 15. This adjustment relied on the retrospective reporting of events before age 15 by women aged 15–19 at the time of the survey. The adjusted equation is as follows:(B2) where M*(t) = adjusted average age at the event in period t, b(a,t) = age-specific event rate at age a in period t (events per 1,000 women), p(T) = proportion of women aged 15–19 reporting an event before age 15 at T, the time of the survey (early events per 1,000 women).

Events before age 15 were assumed to have occurred at exact age 14. Equation (B2) was used to estimate the period mean ages at first birth, first marriage, and first sex throughout this study.