Abstract

Declines in HIV incidence have been slower than expected during the roll-out of antiretroviral treatment (ART) services in sub-Saharan African populations suffering generalized epidemics. Using data from a population-based, open cohort HIV sero-survey (2004–13), we found evidence for initial reductions in sexual activity and multiple sexual partnerships, followed by increases during the period of ART scale-up in areas of high HIV prevalence in Manicaland, east Zimbabwe. Recent population-level increases in condom use were also recorded, but largely reflected high use by the rapidly growing proportion of HIV-infected individuals on treatment. Sexual risk behaviour increased in susceptible uninfected individuals and in untreated (and therefore more infectious) HIV-infected men, which may have slowed the decline in HIV incidence in this area. Intensified primary HIV prevention programmes, together with strengthened risk screening, referral, and support services following HIV testing, could help to maximize the impact of ‘test-and-treat’ programmes in reducing new infections.

Introduction

In 2011, the United Nations set targets for large reductions in new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections (UNAIDS Citation2017). These targets were predicated largely on empirical evidence for very low transmission rates from people living with HIV (PLHIV) with suppressed viral loads, and also on mathematical model estimates that universal HIV testing and immediate antiretroviral treatment (ART) could eliminate HIV transmission. In Rakai, Uganda, Wawer et al. (Citation2005) found that the HIV transmission rate per coital act was 9.62 times greater (95 per cent confidence interval [CI], 3.00–30.84) from PLHIV with a viral load in the highest quartile (≥4.89 log10 copies/mL) than from those with a viral load in the lowest quartile (0.00–3.49 log10 copies/mL). In a landmark trial with 1,763 sero-discordant couples in nine countries, Cohen et al. (Citation2011) found that early ART initiation reduced genetically linked HIV infections by 96 per cent (hazard ratio 0.04; 95 per cent CI 0.01–0.27). Granich et al. (Citation2009) used mathematical models to explore the effect of universal annual HIV testing and immediate ART initiation following a positive diagnosis (‘test-and-treat’) on the long-term dynamics of the HIV epidemic in South Africa. They found that this strategy could reduce HIV incidence from 2 per cent to below 0.1 per cent within ten years. These findings drove changes in World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations on HIV testing and counselling in 2007 (from an ‘opt-in’ to an ‘opt-out’ approach [WHO and UNAIDS Citation2007]) and also in the recommended CD4 count threshold for ART initiation, from 200 to 350 cells/mm3 in 2010 (World Health Organization Citation2010), from 350 to 500 cells/mm3 in 2013 (World Health Organization Citation2013), and from 500 cells/mm3 to initiation regardless of CD4 count in 2015 (World Health Organization Citation2015a).

By 2019, coverage of ART globally had risen to 61 and 73 per cent in HIV-positive men and women, respectively (World Health Organization Citation2020). Disappointingly though, UNAIDS estimates show that HIV incidence fell by only 23 per cent (from 2.2 million in 2010 to 1.7 million [uncertainty range: 1.2–2.2 million] in 2019) against a target of 75 per cent (to 0.5 million) by 2020 (UNAIDS Citation2020). Furthermore, early studies in sub-Saharan African countries found mixed evidence for a population-level impact of ART in reducing HIV incidence (Tanser et al. Citation2013; Iwuji et al. Citation2018; Hayes et al. Citation2019; Makhema et al. Citation2019). A review of trials of test-and-treat strategies, in some cases including promotion of primary prevention methods such as voluntary male medical circumcision (World Health Organization Citation2015b), reported 20–32 per cent lower HIV incidence in intervention arms than in control arms but found that HIV elimination targets were not reached (Havlir et al. Citation2020).

A plausible explanation for these disappointing results is that HIV risk behaviour increased during ART scale-up due to behavioural disinhibition associated with falling death rates (Stolte et al. Citation2004; Venkatesh et al. Citation2011). In a longitudinal analysis of data from eleven countries in eastern and southern Africa with at least three Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) between 1999 and 2016, Schaefer et al. (Citation2019) found that multiple, non-regular, or casual partnerships increased in ten countries for men and nine countries for women. However, in the same analysis, condom use in sexual activity with non-regular partners increased in six countries for men and eight countries for women. In a systematic review of published data on sexual behaviour trends in sub-Saharan Africa over the period of ART roll-out, Legemate et al. (Citation2017, p. 797) concluded that there was ‘no clear evidence of behavioural disinhibition due to expanded access to ART’.

An important limitation of these studies is that the data are not disaggregated by HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment status. Indeed, no previous studies have compared levels and trends in multiple sexual partners or condom use between these population strata. This is an important gap because these kinds of differences occurring within a population could help to explain why reductions in HIV incidence have been smaller than expected during periods of ART scale-up, even when overall levels of unprotected sexual activity remained unchanged. This would be expected if there were an increase in the concentration of sexual risk in groups with higher biological risks of HIV transmission or acquisition; this, in turn, is quite plausible for a combination of three reasons. First, in general, substantial proportions of PLHIV have continued to have unsuppressed viral loads during ART scale-up. In national population-based HIV impact assessment surveys carried out between 2015 and 2019 in ten southern and eastern African countries, the proportions of PLHIV with unsuppressed viral load ranged from 22.6 per cent in Namibia (2017) to 48.0 per cent in Tanzania (2016–17) (PHIA Project Citation2020). Second, with increasingly early ART eligibility, PLHIV with unsuppressed viral loads become increasingly selected for recent infection and therefore for high viraemia and infectiousness. In Rakai, Uganda, Wawer et al. (Citation2005) found that the HIV transmission rate per coital act was 8.25 times greater (95 per cent CI 3.37–20.22) from PLHIV infected in the previous five months than from those with unknown seroconversion dates followed for up to 40 months. Third, PLHIV with unsuppressed viral loads and HIV-negative people may have higher or more rapidly increasing levels of unprotected sexual activity than other population groups. No studies have compared levels and trends in sexual behaviour between these groups. However, there is strong evidence that diagnosis of infection and initiation of ART can reduce sexual risk behaviour in HIV-positive individuals. In a systematic review of literature examining the efficacy of voluntary HIV counselling and testing (VCT) in changing HIV-related risk behaviours in less developed countries, Fonner et al. (Citation2012) found that VCT reduced numbers of sexual partnerships (odds ratio [OR] 0.61; 95 per cent CI 0.37–0.997) and increased condom use (OR 3.24; 95 per cent CI 2.29–4.58) in people receiving HIV-positive results. In a review of observational studies in less developed countries, Venkatesh et al. (Citation2011) concluded that ART initiation can be associated with a reduction in unprotected sexual activity. One example was a multi-country cohort study in which unprotected sexual activity between three-monthly visits declined from 6.2 per cent before ART initiation to 3.7 per cent after ART initiation (p = 0.03) (Donnell et al. Citation2010). Another example was a cohort study of 6,263 PLHIV in South Africa, where, in comparison to follow-up visits before ART initiation, visits while receiving ART were associated with reductions in reports of being sexually active (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.86; 95 per cent CI 0.78–0.95), having unprotected sexual activity (aOR 0.40; 95 per cent CI 0.34–0.46), and having multiple sexual partners (aOR 0.20; 95 per cent CI 0.14–0.29) (Venkatesh et al. Citation2010). Where overall levels of sexual risk behaviour are unchanged and a growing proportion of PLHIV are on ART with reduced risk behaviour, there must have been increases in risk behaviour in undiagnosed PLHIV with unsuppressed viral loads and in uninfected people.

Increases in sexual risk behaviour in PLHIV with undiagnosed infection and in uninfected people are also plausible because there have been changes likely to have placed upward pressures on risk. These include the scaling down of national behaviour change programmes to focus on the ‘treatment-as-prevention’ approach (Nguyen et al. Citation2011); reductions in post-test counselling, with priority given to identifying and referring those with positive results to treatment (Wanyenze et al. Citation2013; World Health Organization Citation2015c); increasing selection for improved health in PLHIV who remain undiagnosed; and behavioural disinhibition concentrated within these groups.

This paper addresses these gaps in understanding of the changes in sexual risk behaviour that occur within sub-Saharan African populations during periods of ART scale-up, and the influence of increases in HIV diagnosis, treatment, and survival on HIV risk, by using data from a population-based, open cohort HIV sero-survey in high prevalence areas in Manicaland, Zimbabwe, to investigate the following questions:

Did levels of sexual risk behaviour and condom use in the population as a whole increase or decrease during the introduction and roll-out of ART services?

How did the composition of the population by HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment status (i.e. between population subgroups with different biological and behavioural risks of acquiring or transmitting infection) change during the roll-out of ART services?

To what extent did levels and trends in sexual risk behaviour and condom use differ between HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment population subgroups during the roll-out of ART services? and

Did aspects of ART scale-up (e.g. HIV diagnosis, ART initiation, and behavioural disinhibition) or selection for individual characteristics associated with high- or low-risk behaviours (age, marital status, and predisposition towards risk-taking) contribute to differences in sexual risk between these population subgroups?

Data and methods

Study setting and data

Data were taken from the Manicaland General Population Open Cohort HIV Sero-Survey (Manicaland Study) conducted at twelve sites (eight sites in 2012–13) in Zimbabwe’s eastern Manicaland province between 1998 and 2013 (Gregson et al. Citation2017). The survey sites represented the diverse population strata in Manicaland and included two towns, four agricultural estates (two in 2012–13), two roadside trading centres, and four subsistence farming areas (two in 2012–13). In each survey round, a prospective household census was updated and eligible individuals were identified. From 2006–08 onwards, eligibility was restricted to a random sample of two-thirds of households. Survey rounds were conducted at three-year intervals with newly eligible individuals recruited at each round and participants followed prospectively in subsequent rounds.

Long-term trends in population-level sexual behaviour have been documented previously (Gregson et al. Citation2017). Here, data from the four most recent survey rounds (2003–05, 2006–08, 2009–11, and 2012–13) were used to investigate trends in sexual behaviour disaggregated by HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment status during the introduction (2004–07) and the early (2007–10) and more recent (2010–13) periods of scale-up of ART services for HIV infection in Zimbabwe (Church et al. Citation2015). VCT services for HIV were introduced in 1999, but coverage and uptake were low and increased only with the national roll-out of ‘prevention of mother-to-child transmission’ (PMTCT) services in 2002 (Cremin et al. Citation2010). Clinics for treatment of opportunistic infections were established in 2003 and the ART programme began in 2004. Zimbabwe replaced VCT with provider-initiated testing and counselling (PITC) in 2007 and increased the CD4 count threshold for ART initiation from 200 to 350 cells/mm3 in 2010, and subsequently to 500 cells/mm3 in 2013. In 2012, WHO’s Option B+ approach to PMTCT was adopted, requiring immediate initiation of pregnant women on to lifelong ART (Tlhajoane et al. Citation2018).

For consistency across survey rounds, the four survey sites dropped in 2012–13 were excluded from the current study. Eligibility was limited to adults aged 15–54 years who had slept in a survey household for four or more nights in the last month. Participation rates in the four survey rounds ranged around 73.0–83.5 per cent; follow-up rates among individuals who were still alive and resident in survey households ranged from 77.0 to 85.9 per cent (Gregson et al. Citation2017).

Data collected in the Manicaland Study included results from HIV sero-testing (using dried blood spot samples) and self-reported information on socio-demographic characteristics, sexual behaviour, health status, and uptake of HIV testing and treatment services. The latter included data on the timing of HIV diagnosis and ART initiation where relevant. To reduce social desirability bias in data on sexual behaviour, informal confidential voting interview methods were used (Gregson et al. Citation2002), in which participants answered questions on sexual behaviour on small pieces of card and inserted these into a locked box instead of responding directly to the interviewer.

HIV prevalence in the study sites declined from 19.9 per cent (95 per cent CI 19.0–20.7) in 2004 to 15.8 per cent (95 per cent CI 14.9–16.6) in 2013. HIV incidence fell by 45 per cent, from 1.72 per cent (95 per cent CI 1.44–2.06) between 2004 and 2007 to 0.95 per cent (95 per cent CI 0.75–1.20) by 2010; and declined more slowly, by 18 per cent, to 0.78 per cent (95 per cent CI 0.62–0.99) from 2010 to 2013 (Gregson et al. Citation2017). HIV incidence in the Manicaland cohort was higher initially and declined more steeply between 2005 and 2012 than in other population cohorts in southern and eastern Africa except for South Africa (Slaymaker et al. Citation2018). Further details of the Manicaland Study are available elsewhere (Gregson et al. Citation2017) (http://www.manicalandhivproject.org/).

Data analysis

To establish whether levels of sexual risk behaviour for HIV acquisition and transmission changed during ART scale-up, indicators of three primary aspects of sexual behaviour (sexual abstinence, multiple sexual partnerships, and condom use) were examined. These indicators were chosen to be consistent with recent publications that have measured trends in sexual behaviour during ART scale-up in sub-Saharan African countries, including Zimbabwe (Legemate et al. Citation2017; Schaefer et al. Citation2019). Sexual abstinence was defined as not having had sexual intercourse in the year before the interview date, among people who reported ever having had sexual intercourse. Multiple sexual partnerships and condom use were defined, respectively, as having had more than one sexual partner in the last year and having used condoms at last sexual intercourse, among people who reported having had sexual intercourse in the last year. Trends in different types of sexual partnerships (new, casual, concurrent, and commercial) were also measured. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable by central year of survey round (2004, 2007, 2010, and 2013), for men and women separately, and by age, marital status, and survey round (supplementary material, Tables S9(a)–(f)). For sexual abstinence, changes in reported reasons over time were examined. For condom use, descriptive statistics were calculated separately for people who reported one sexual partner vs. multiple sexual partners in the last year. Differences in each behaviour variable were calculated for each survey date compared with the 2004 baseline measurement.

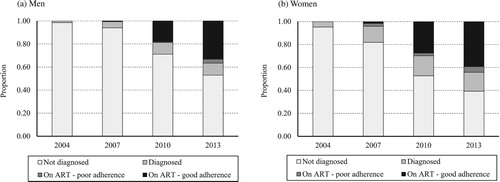

Changes in HIV prevalence between survey rounds were investigated using the biomarker test results. To examine changes over time in the distribution of the population by HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment status, descriptive statistics were calculated for the proportions of the total population infected at each round of the survey. PLHIV were separated into those not yet diagnosed, those diagnosed but not yet on ART, and those on ART with poor vs. good adherence, using self-reported data collected in survey questionnaires. ‘Good’ ART adherence was defined as having started and still being on ART and never having forgotten to take the drugs.

To measure differences in levels and trends in sexual risk behaviours between HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment groups during ART scale-up, proportions of study participants reporting each sexual behaviour were calculated and compared for each of these groups across the survey rounds. For ART status, those with poor and good adherence were combined into a single group due to small numbers. Binomial exact 95 per cent confidence intervals were calculated for proportions, and differences in behaviour between HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment groups and over time were investigated.

To investigate the effects of receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis and of ART initiation on sexual risk behaviour for HIV transmission, the proportions reporting multiple sexual partners between 2010 and 2013 and condom use at last sexual intercourse in 2013 were compared for PLHIV who were undiagnosed in 2010 according to whether they: (1) remained undiagnosed in 2013; (2) were newly diagnosed but not initiated on ART between 2010 and 2013; or (3) were newly diagnosed and initiated on ART between 2010 and 2013. The same behaviour indicators were compared for PLHIV who were diagnosed but not on ART in 2010 according to whether or not they were initiated on ART between 2010 and 2013. Differences between groups in numbers of lifetime sexual partners were accounted for in these analyses.

The contribution of selection for older or younger age to differences in behaviour between HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment groups was investigated by comparing the median ages of people in these groups and the proportions of people in each age group that reported each primary indicator of sexual risk behaviour for HIV infection. The contribution of differences in individuals’ underlying tendencies to engage in sexual risk behaviour due to predisposition or personal circumstances (such as being divorced or widowed) to differences in behaviour between HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment groups was investigated. This was done by pooling the data from the 2010 and 2013 surveys, comparing proportions of individuals with five or more lifetime sexual partners in these groups, and examining whether differentials found in this indicator were also present in two indicators of recent sexual risk behaviour (multiple sexual partners in the last year, and multiple sexual partners in the last year alongside no condom use at last sexual intercourse). Finally, the contribution of behavioural disinhibition, resulting from ART-associated reductions in mortality, to sexual risk behaviour within the study population was investigated by examining changes in the proportions of HIV-negative individuals who reported multiple sexual partners in the last year and condom use at last sexual intercourse during the early (2007–10) and more recent (2010–13) periods of ART scale-up.

Differences between groups and survey rounds were investigated by calculating and examining odds ratios using multivariable logistic regression. Unless stated otherwise, regressions were adjusted for age group (15–24, 25–34, 35–44, and 45–54 years) and study location (town, estate, roadside, and subsistence farming). In the analysis of the influence of predisposition to engage in sexual risk behaviour on differences in recent behaviour between HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment groups, regressions were also adjusted for survey round and clustering of measurements for the same individuals. All analyses were carried out using Stata v.14.2.

Results

Trends in sexual behaviour and condom use in the population as a whole

Previous research has shown that median age at first sexual intercourse increased during the period before ART scale-up (1999–2007) for both sexes: for men, from 18.6 years (interquartile range [IQR] 16.9–20.5) to 20.2 years (18.2–22.4); for women, from 18.8 years (17.3–20.5) to 19.4 years (17.7–21.0) (Gregson et al. Citation2017). Then, as ART services were scaled up, median age at first sexual intercourse for men rose further, to 22.0 years (19.6–24.4) in 2010 before falling to 21.0 years (19.0–23.2) in 2013. For women, median age at first sexual intercourse fell back more quickly, to 19.1 years (17.7–20.8) in 2010 and 18.8 years (17.3–20.5) in 2013 (Gregson et al. Citation2017).

Similarly, the proportions of sexually experienced people who were currently sexually active decreased up to 2007 before increasing between 2007 and 2013: for men, from 85.5 per cent in 2007 to 92.1 per cent in 2013; for women, from 76.8 to 83.1 per cent (; see also supplementary Tables S9(a)–(b)). Common reasons given for sexual abstinence in 2004 were not yet having married (men 28.3 per cent; women 5.9 per cent); being widowed, divorced, or separated (5.4 vs. 26.3 per cent); living apart from one’s spouse (5.6 vs. 16.6 per cent); and risk of HIV infection (29.6 vs. 15.6 per cent) (supplementary Table S1). The contribution of never marrying to sexual abstinence increased between 2004 and 2007 and then fell in 2010. The contribution of widowhood to sexual abstinence was highest among PLHIV and increased between 2004 and 2010 before stabilizing in 2013. The proportion of HIV-negative people reporting risk of HIV infection as their reason for sexual abstinence fell after the introduction of ART, from 31.1 per cent in 2004 to 15.6 per cent in 2007 for men; and from 15.3 per cent in 2004 to 12.1 per cent in 2007, 4.0 per cent in 2010, and 1.5 per cent in 2013 for women. Throughout the study period, being HIV-positive, having a partner who is HIV-positive, and risk of passing on HIV infection were rarely mentioned as reasons for sexual abstinence.

Table 1 Trends in sexual behaviour and condom use, men and women aged 15–54 years in Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 2004–13

Among men and women who had started sexual activity and were not abstaining, the proportions with multiple sexual partners in the last year fell from 2004 to 2010, before recovering between 2010 and 2013: for men from 15.3 to 23.2 per cent; for women from 1.9 to 2.3 per cent (; see also supplementary Tables S9(c)–(d)). Similar trends were found for other measures of sexual risk behaviour including having a new partner in the last year, a casual partner in the last three years, or concurrent sexual partners, and engaging in commercial sexual activity (). An exception to this was that, for women, these measures increased between 2004 and 2007 before falling from 2007 to 2010.

Table 2 Trends in sexual partner types in men and women aged 15–54 years who have been sexually active in the last year, Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 2004–13

For sexually active men, condom use at last sexual intercourse fell from 27.3 per cent in 2004 to 20.2 per cent in 2010, and then increased to 25.1 per cent in 2013 (). The initial reduction in condom use reflected an increase in the proportion of sexually active men who were married (from 61.8 per cent in 2004 to 78.8 per cent in 2010) and consistently lower condom use in married men compared with unmarried men (supplementary Table S9(e)). For men with multiple sexual partners, condom use remained consistent at close to 40 per cent throughout the study period (). For men with one partner, condom use was much lower and fell from 21.5 per cent in 2007 to 16.8 per cent in 2010 before recovering to 20.5 per cent in 2013. For women overall, condom use increased from 12.1 per cent in 2007 to 16.1 per cent in 2010 but remained unchanged between 2010 and 2013. Condom use was much higher in women with multiple sexual partnerships than in those with a single partner. Similar time trends were observed for both groups but sample sizes for women with multiple partners were small and no statistically significant changes were found.

For people with a single sexual partner in the last year, condom use at last sexual intercourse was higher in those for whom this was a new rather than an existing partner (for men, 44.5 vs. 14.6 per cent; aOR = 3.06; N = 6,978; p < 0.001; for women, 24.6 vs. 11.8 per cent; aOR = 3.23; N = 13,985; p < 0.001; figures from pooled data from the four survey rounds [not shown in tables]). For men and women with multiple sexual partners in the last year, condom use did not differ between those with and without concurrent partners (p = 0.54).

Temporal changes in the HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment composition of the population

Between 2004 and 2013, the proportion of the population infected with HIV fell steadily, from 15.5 to 12.6 per cent (aOR 0.85; 95 per cent CI 0.81–0.89) for men, and from 20.5 to 18.1 per cent (aOR 0.89; 95 per cent CI 0.87–0.92) for women (not shown in tables). In 2004 few PLHIV had been diagnosed and none were on ART (). For men, the proportion of PLHIV diagnosed increased to 5.9 per cent in 2007, 28.8 per cent in 2010, and 47.1 per cent by 2013; and the proportion on treatment increased to 0.6 per cent in 2007, 18.7 per cent in 2010, and 36.7 per cent by 2013. For women, the proportion diagnosed increased to 18.2 per cent in 2007, 47.3 per cent in 2010, and 60.7 per cent in 2013; and the proportion on treatment increased to 4.2 per cent in 2007, 29.8 per cent in 2010, and 44.2 per cent in 2013. Self-reported ART adherence among PLHIV on treatment increased from 39.5 per cent overall in 2007 to 93.1 per cent in 2010, before dropping to 89.3 per cent in 2013; similar levels and trends were seen for both sexes.

Figure 1 Changes over time in the proportions of (a) men and (b) women aged 15–54 years living with HIV infection who were undiagnosed, diagnosed but not yet on antiretroviral treatment, on antiretroviral treatment with poor adherence, and on antiretroviral treatment with good adherence, Manicaland, East Zimbabwe, 2004–13

Source: Authors’ analysis of Manicaland General Population Open Cohort Sero-Survey, 2004–13.

Levels and trends in sexual behaviour and condom use by HIV and treatment status

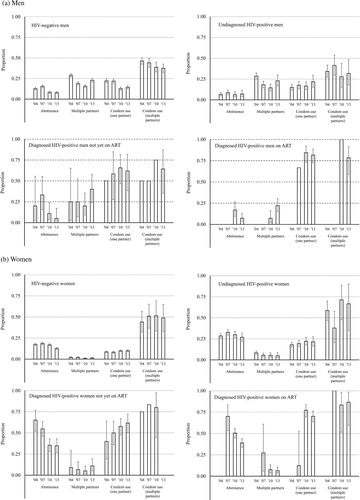

(a) shows the levels and trends in sexual abstinence, multiple sexual partnerships, and condom use at last sexual intercourse for those with a single partner vs. multiple sexual partnerships in the last year, for sexually experienced HIV-negative men and for HIV-positive men by diagnosis and treatment status. The pattern observed in the overall population of a decline in the proportion of men abstaining between 2007 and 2010 following an earlier increase is also evident in the three population subgroups with sufficient data. Abstinence in HIV-positive men on treatment fell between 2010 and 2013 (age- and location-adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.34; 95 per cent CI 0.15–0.78) (supplementary Table S2).

Figure 2 Levels and trends in sexual risk behaviour for HIV acquisition and transmission, by HIV infection, diagnosis, and antiretroviral treatment status, in (a) men and (b) women aged 15–54 years, Manicaland, east Zimbabwe, 2004–13

Notes: Error bars indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals (CIs). Bars without CIs are based on small sample sizes (N < 10).

Source: As for .

HIV-negative men and undiagnosed HIV-positive men reported similar levels and trends in multiple sexual partnerships in the past year ((a)). In both cases, the proportion with multiple partnerships declined between 2004 and 2010 and increased in 2013 (supplementary Table S3). The numbers of HIV-positive men who had been diagnosed or were on ART in 2004 and 2007 were small, but the data also show increases in the proportion with multiple partnerships between 2010 and 2013 in these groups. In 2013, the odds of reporting multiple sexual partnerships in the last year were twice as high for diagnosed men not yet on ART as for HIV-negative men and undiagnosed HIV-positive men combined (40.0 vs. 22.9 per cent; aOR 2.44; 95 per cent CI 1.25–4.76). The proportion of men on ART with multiple sexual partnerships rose from a low base in 2010 (7.2 per cent) to a similar level to that of HIV-negative men and undiagnosed HIV-positive men in 2013 (22.2 per cent).

For men with one sexual partner in the last year, the overall drop between 2007 and 2010 in condom use at last sexual intercourse was only seen in HIV-negative men, for whom it fell from 22.0 to 12.8 per cent and then increased slightly between 2010 and 2013 (to 14.5 per cent) ((a)). In undiagnosed HIV-positive men, condom use increased from 16.6 per cent in 2010 to 21.7 per cent in 2013. In diagnosed HIV-positive men, condom use was much higher, and was highest in those on ART (81.6 per cent in 2013). However, no significant changes in condom use occurred in these groups between 2010 and 2013, so the overall increase in condom use during this period () resulted mainly from the increase in the proportion of HIV-positive men who knew their status and the higher condom use in this group.

For HIV-negative men and undiagnosed HIV-positive men, condom use was consistently higher in those with multiple sexual partnerships than in those with a single partner ((a); supplementary Table S5). This difference was not seen in diagnosed HIV-positive men, including those on treatment, for whom condom use was higher. In HIV-negative men with multiple partners, condom use declined steadily from 46.3 per cent in 2004 to 37.4 per cent in 2013; however, this decline was not statistically significant after adjusting for changes in the age and location distributions of the study population over time (p = 0.3). No changes in condom use over time were detected in the subgroups of HIV-positive men with multiple sexual partnerships; as with HIV-positive men with a single partner, condom use was highest in those on ART, and there were considerable gaps in protection in those who had not been diagnosed or started on treatment.

Similar results for women are shown in (b). As for men, the overall temporal changes in abstinence noted in occurred across all HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment groups, with declines between 2007 and 2013 being seen in each group (supplementary Table S2). However, there were more pronounced differences in underlying levels of abstinence between the groups, with HIV-positive women reporting consistently higher levels than uninfected women. Up to 2007, abstinence was particularly common in diagnosed HIV-positive women not on ART (54.8 per cent vs. 18.7 per cent in HIV-negative women in 2007) and in those on treatment (70.0 per cent). The declines in abstinence during ART scale-up were also steepest in these groups.

In general, few sexually active women reported multiple sexual partnerships in the last year, but levels were higher in all groups of HIV-positive women than in uninfected women ((b)). The overall drop in women with multiple partnerships between 2007 and 2010 was statistically significant in the majority group of HIV-negative women (from 2.1 to 1.0 per cent; aOR 0.50; 95 per cent CI 0.33–0.76), and the rebound after 2010 (to 1.5 per cent) also occurred mainly in this group (supplementary Table S3).

As with men, condom use at last sexual intercourse was higher in HIV-positive women than in uninfected women and, for those with one sexual partner in the last year, highest in HIV-positive women on ART ((b); supplementary Tables S4 and S6). This gradient was less steep for women with multiple sexual partnerships, among whom even HIV-negative women reported relatively high condom use (48.8 per cent in 2013). Steady increases in condom use over time were found for diagnosed HIV-positive women not on ART with one sexual partner (from 40 per cent in 2004 to 61.7 per cent in 2013; aOR 2.35; 95 per cent CI 0.84–6.55). Otherwise no clear trends were seen in the data (supplementary Table S6).

Factors contributing to differences and changes in sexual risk behaviour by HIV and treatment status

Differences in the age structures of population subgroups delineated by HIV and treatment status could have contributed to the differences in sexual behaviour and condom use found between these groups. For both sexes, PLHIV in the study population tended to be older than uninfected people; and, among PLHIV, those on treatment were older than those not yet on ART (supplementary Table S7). The median ages of men in each HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment group increased over time except for men diagnosed with HIV but not on ART. The median age of undiagnosed HIV-positive women increased from 31 years in 2004 to 34 years in 2013, but otherwise there were no systematic changes over time. Levels of risk behaviour varied with age (supplementary Table S8) but the differences in sexual risk behaviour between HIV and treatment groups remained after accounting for these differences by age (; supplementary Tables S2–S6).

Table 3 Lifetime sexual partners and recent sexual behaviour by HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment status, men and women aged 15–54 in Manicaland, Zimbabwe, pooled data from 2010 and 2013

Differences in individuals’ predisposition to engage in unprotected sexual activity with multiple sexual partners might also have contributed to the differences found in sexual risk behaviour between HIV and treatment status groups. Larger proportions of PLHIV than uninfected people reported five or more lifetime sexual partners, and more PLHIV who had been diagnosed (including those on ART) than undiagnosed PLHIV reported five or more lifetime partners (). These differences remained after accounting for the older ages of the HIV-infected and diagnosed groups. To a limited extent, these patterns persisted in recent behaviour. In particular, the odds of reporting multiple sexual partners in the last year were higher for HIV-positive men who were diagnosed but not on ART (aOR 2.01; 95 per cent CI 1.20–3.36) than for uninfected men. However, higher condom use in this group meant that their odds of having multiple sexual partners without condom use were no higher. The odds of reporting multiple sexual partners in the last year were much higher for women in all HIV-positive categories than for HIV-negative women (). HIV-positive women also reported higher condom use than HIV-negative women but the odds of having multiple sexual partners without condoms were still higher for those who had not yet been diagnosed (aOR 2.16; 95 per cent CI 1.14–4.09).

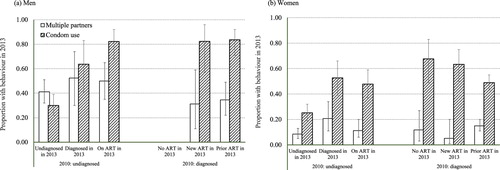

Individuals have been found to alter their sexual behaviour after receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis (Rucinski et al. Citation2018) or being initiated on ART (Venkatesh et al. Citation2010). This possibility is explored in (and supplementary Table S10). For men who were HIV-positive in 2010, a higher proportion of those newly diagnosed between 2010 and 2013 but not yet on ART reported multiple sexual partnerships during this period compared with those who remained undiagnosed, after adjusting for differences in number of lifetime sexual partners (52.4 vs. 41.2 per cent; aOR 2.87; 95 per cent CI 0.93–8.90). New initiation on ART did not show an association with multiple sexual partnerships. HIV diagnosis and ART initiation between 2010 and 2013 were both associated with much greater odds of reporting condom use at last sexual intercourse in 2013, among men who were HIV-positive in 2010. Men already on ART in 2010 were also much more likely to report condom use in 2013 than men who were HIV-positive in 2010 and remained undiagnosed in 2013. Similar patterns of association between HIV diagnosis and ART initiation status and the multiple sexual partners and condom use variables were found for HIV-positive women.

Figure 3 Effects of HIV diagnosis and antiretroviral treatment initiation between 2010 and 2013 on multiple sexual partnerships in the last year and condom use at last sexual intercourse in 2013, in (a) men and (b) women aged 15–54 years living with HIV infection, Manicaland, east Zimbabwe

Notes: Error bars indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals (CIs).

Source: As for .

Finally, behavioural disinhibition following the introduction of ART services and subsequent mortality reductions (Reniers et al. Citation2014) could have altered sexual risk behaviour and condom use. This effect might have been expected to occur particularly in uninfected individuals, due to reductions in the perceived negative consequences of acquiring HIV infection. In uninfected men, the long-term decline in the proportion reporting multiple sexual partners in the last year ended in 2010 and had reversed by 2013, increasing from 15.7 to 23.0 per cent (aOR 1.62; 95 per cent CI 1.38–1.91) ((a); supplementary Table S3). Condom use at last sexual intercourse also fell in this group between 2007 and 2010, from 26.2 to 16.9 per cent (aOR 0.67; 95 per cent CI 0.57–0.79) ((a); supplementary Tables S4 and S5). However, in uninfected women, the proportion reporting multiple sexual partnerships declined from 2.1 per cent in 2007 to 1.0 per cent in 2010 (aOR 0.50; 95 per cent CI 0.33–0.76) ((b); supplementary Table S3) and condom use increased from 9.1 per cent in 2007 to 10.4 per cent in 2010 (aOR 1.16; 95 per cent CI 0.99–1.37) ((b); supplementary Tables S4 and S6).

Discussion and conclusions

Population-level changes in sexual risk behaviour for HIV transmission occurred during the roll-out of ART in east Zimbabwe. In the early years (2004–07), age at first sexual intercourse rose, sexual abstinence increased, and fewer sexually active people reported multiple sexual partnerships, but there was little change in condom use. As the scale-up of ART services accelerated (2007–13), these changes were reversed, with reported increases in sexual activity, multiple sexual partnerships, and condom use. These increases in multiple partnerships and condom use were similar to those reported during ART scale-up in other sub-Saharan African countries with generalized HIV epidemics (Legemate et al. Citation2017; Schaefer et al. Citation2019).

The study results also show that there can be substantial differences in sexual abstinence, multiple sexual partnerships, and condom use between HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment groups within a population. In east Zimbabwe, we found that PLHIV generally reported similar (men) or higher (women) levels of multiple sexual partnerships compared with uninfected individuals, but their levels of condom use were also higher, particularly after HIV diagnosis. Between 2007 and 2013, multiple sexual partnerships increased and condom use changed little in all HIV infection and treatment groups. However, a large rise in the proportion of PLHIV diagnosed and initiated on ART drove the population-level increase in condom use during this period. Changes in sexual behaviour distributed within the population in this way will ceteris paribus have pushed up HIV incidence. This is because the groups showing increased risk behaviour included susceptible (uninfected) people and infectious people (untreated PLHIV), whereas the increase in condom use was concentrated in people with a low risk of transmitting infection (PLHIV on ART, with a low viral load) (Wawer et al. Citation2005; Cohen et al. Citation2011; Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care Citation2016).

In another general population cohort in a rural community in South Africa, McGrath et al. (Citation2013) found small reductions in people reporting multiple sexual partnerships in the last year and in the point prevalence of concurrent partnerships, and an increase in condom use at last sexual intercourse with regular partners as ART became available between 2005 and 2011. In contrast to east Zimbabwe, they found that the increase in condom use occurred among uninfected individuals and undiagnosed PLHIV, as well as diagnosed PLHIV. Condom use was highest in diagnosed PLHIV, but their results were not disaggregated by ART status, so it was not possible to gauge fully the extent to which condoms provided protection against transmission from infectious individuals. Nevertheless, the authors concluded that changes in sexual behaviour had not counteracted the preventative biological effects of HIV treatment in their study population. No other studies have investigated trends in sexual behaviour in the general population by HIV infection and diagnosis status during ART scale-up.

The higher levels of condom use in diagnosed PLHIV in the general population in east Zimbabwe and South Africa are consistent with clinical data showing an association between receiving a positive HIV diagnosis and subsequent reductions in unprotected sexual activity (Venkatesh et al. Citation2011; Fonner et al. Citation2012). Among undiagnosed PLHIV in east Zimbabwe in 2010, those who had been diagnosed by 2013 were more likely to use condoms in 2013 than those who remained undiagnosed, which suggests that the ART scale-up itself contributed to the population-level increase in condom use.

It is less clear whether the ART scale-up contributed to the increase in multiple sexual partnerships. Among PLHIV in 2010, those who were diagnosed but not on treatment in 2013 were more likely to report multiple sexual partnerships in the last year in 2013 than those who remained undiagnosed. The numbers of PLHIV in this group were small though, and the differences were not statistically significant or sustained in those on treatment. Elsewhere, HIV diagnosis (Fonner et al. Citation2012) and ART initiation (Venkatesh et al. Citation2010) have been associated with reductions in multiple sexual partners. PLHIV in east Zimbabwe, including those on ART, were selected for higher numbers of lifetime sexual partnerships and were more likely to report multiple partnerships in the last year than uninfected individuals after accounting for age differences. Therefore, the longer survival of PLHIV could have contributed to the population-level increase in multiple sexual partnerships. The reductions in age at first sexual intercourse and in sexual abstinence, large declines in reporting HIV risk as the reason for sexual abstinence, and increase in multiple sexual partnerships in uninfected individuals during ART scale-up are all consistent with a growth in behavioural disinhibition following improvements in the health and survival of PLHIV, as was documented for men engaging in sexual activity with men in the Netherlands in the early 2000s (Stolte et al. Citation2004).

An alternative explanation for the trends in multiple sexual partnerships in east Zimbabwe is that these reflected volatility in the national economy. The country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), in constant 2010 US$, fell from $17.5 billion in 2001 to $12.4 billion in 2004 and $9.0 billion in 2008, before recovering to $16.4 billion in 2013 (World Bank Citation2020). Steen et al. (Citation2019) have argued that the substantial declines in GDP before 2009 caused a drop in men’s demand for sex work, which rebounded subsequently as the economy recovered. They noted reports of economic stagnation driving larger numbers of women into transactional sex arrangements in the early 2000s (O’Donnell et al. Citation2002), a phenomenon also documented in a qualitative study in east Zimbabwe in early 2009 (Elmes et al. Citation2017). These trends and patterns in commercial sexual activity are reflected in the survey data presented here. The data show a steady reduction in the proportion of men reporting commercial sexual activity, from 8.5 per cent in 2004 to 2.5 per cent in 2010, but also short-term increases around the height of Zimbabwe’s economic collapse (2006–08) in the proportions of women reporting a new sexual partner in the last year (12.8 per cent in 2004; 18.8 per cent in 2007; 9.1 per cent in 2010), a casual partner in the last three years (10.7, 14.6, and 7.0 per cent, respectively), and recent commercial sexual activity (2.7, 4.8, and 2.6 per cent, respectively) (). During the economic recovery, between 2010 and 2013, the data show a resurgence in commercial sexual activity contributing to the increase in reports of multiple sexual partnerships ().

The primary indicator of sexual risk behaviour in this study was chosen to be multiple sexual partnerships in the last year, for consistency with recent studies of national trends in HIV risk behaviour (Legemate et al. Citation2017; Schaefer et al. Citation2019) and because of its strong association with actual HIV risk in east Zimbabwe (Lopman et al. Citation2008). However, as Slaymaker has highlighted, all aspects of sexual behaviour are interrelated, so single aspects cannot be fully understood if looked at in isolation (Slaymaker Citation2004). Others have argued that multiple sexual partnerships can be an inadequate indicator of HIV risk because the variable does not account for partners’ sexual histories (Dimbuene et al. Citation2014). In the present study, trends in reports of new partners in the last year, casual partners in the last three years, concurrent partnerships at date of interview, and current engagement in commercial sexual activity were generally similar to trends in multiple sexual partnerships. Important exceptions were the changes for women during Zimbabwe’s economic collapse, as noted earlier (; supplementary Figure S1(b)). Eaton et al. (Citation2014) found similar relative declines (60–70 per cent) in multiple sexual partnerships, non-marital concurrency, and polygyny in the study population between 1998 and 2011. Their study showed that polygyny accounted for 25 per cent of concurrency among men, and polygynous men experienced higher levels of marital dissolution (relative risk [RR] 2.92; 95 per cent CI 1.87–4.55) and casual sexual partnerships (RR 1.63; 95 per cent CI 1.41–1.88) than monogamously married men. Trends in age-disparate relationships (Luke and Kurz Citation2002) are not reported here. However, in an earlier analysis, no changes were found during ART scale-up in the proportion of women aged 15–24 years in age-disparate relationships or in the association between this type of relationship and HIV incidence (Schaefer et al. Citation2017). Delva et al. (Citation2013) have argued that how condom use is distributed within a population by HIV infection status and sexual risk behaviour can be an important determinant of HIV transmission. In east Zimbabwe, condom use was higher in people with multiple sexual partnerships than among those with one partner, and also higher in individuals in concurrent partnerships compared with those with a single sexual partner but not compared with others with multiple partners. In people reporting a single partner in the last year, condom use was higher for those whose partner was a new partner. For men, the proportion reporting a new sexual partner in the last year increased during ART scale-up (; supplementary Figure S1(b)), so this higher level of condom use with new partners could have contributed to the rise in condom use in those with a single partner over this period. Condom use at last sexual intercourse in the last year was used in calculating the indicators of unprotected sexual activity for people with single and multiple sexual partnerships. These simple indicators use the same time frames as indicators recommended by UNAIDS (Citation2019) but will not capture differences in consistency and correctness of condom use, which may vary between population subgroups or over time (Slaymaker Citation2004). More generally, the indicators of sexual risk behaviour used in this study were chosen to strike a balance between matching the length of the three-year intervals over which trends in ART scale-up and HIV incidence were measured and minimizing recall bias.

The strengths of this study include use of longitudinal data from a large population-based, open cohort survey that spanned the scale-up of ART services in a sub-Saharan African population with a well-described generalized HIV epidemic (Gregson et al. Citation2017). The indicators of sexual risk behaviour and of HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment were measured consistently across survey rounds using a fixed set of questions. However, the data on sexual behaviour, HIV diagnosis, and treatment were based on self-reports, which can provide underestimates due to social desirability bias (Catania et al. Citation1990; Kim et al. Citation2016). An informal confidential voting interview method was used to reduce this bias in the sexual behaviour data (Gregson et al. Citation2002) but some under-reporting could remain (Langhaug et al. Citation2010). For PLHIV on ART, differences in sexual risk behaviour by ART adherence (and thereby, indirectly, by viral load suppression and transmission probability) could not be investigated because numbers with self-reported poor adherence were small. In an analysis of 560 PLHIV on ART in the study population in 2010, 94.3 per cent self-reported good adherence, which reduced to 69.3 per cent after confirming antiretroviral drug presence and concentration using biomarkers (Rhead et al. Citation2016). People with high mobility and sexual risk behaviour can be under-represented in population surveys (Catania et al. Citation1990). In 174 female sex workers (FSWs) identified using snowball sampling and household survey methods in the study sites in 2010, only 36.2 per cent (63/174) participated in the survey (Rhead et al. Citation2018). HIV prevalence was much higher in FSWs than in non-FSWs (52.6 vs. 19.8 per cent; age-adjusted odds ratio 4.0; 95 per cent CI 2.9–5.5). Among HIV-positive women, FSWs were more likely to be diagnosed (58.2 vs. 42.6 per cent; p = 0.042) and HIV-diagnosed FSWs were more likely to be on ART (84.9 vs. 64.0 per cent; p = 0.043) (Rhead et al. Citation2018), so overall levels of HIV diagnosis and treatment could be underestimated in this study. Other limitations include repeated interview bias (six rounds of data collection were completed over 15 years) and the assumption, made in the analyses of multiple sexual partnerships in the last year, that all study participants had been in their current HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment state throughout the year preceding the interview, which could have caused bias in the differences in behaviour measured between these states. Insufficient data were available to compare multiple sexual partnerships and condom use by type of location or by discordance/concordance in HIV infection, diagnosis, and treatment status between survey participants and their partners, which may also affect HIV transmission rates within a population.

The results of this study must be interpreted with caution, given these limitations in the data. With this important caveat, it appears that both multiple sexual partnerships and condom use increased in the population in east Zimbabwe during the rapid scale-up of ART services. However, unprotected sexual risk behaviour became more concentrated in the population subgroups at greatest biological risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV infection. An unknown combination of increasing behavioural disinhibition, selective survival, and reduced morbidity in individuals with high-risk behaviours, alongside revival in the local economy, contributed to the rise in multiple sexual partnerships. This rise in multiple partnerships, greater condom use in these partnerships, and increases in the proportions of PLHIV diagnosed and initiated on ART contributed to the rise in condom use. Mathematical model studies have shown that increases in sexual risk behaviour can counteract the biological effects of ART in reducing HIV transmission (Velasco-Hernandez et al. Citation2002; Baggaley et al. Citation2005). For example, in Bezemer et al.’s (Citation2008) study of men who engage in sexual activity with men in the Netherlands, the epidemiological benefits of earlier diagnosis and ART on HIV incidence were offset entirely by increases in sexual risk behaviour. Granich et al.’s (Citation2009) study showing that test-and-treat strategies could eliminate HIV transmission assumed that strengthened behaviour change programmes would contribute to the reduction in incidence. Therefore, it is plausible that the changes in patterns of sexual risk behaviour found in this study contributed to the small reduction in HIV incidence in east Zimbabwe between 2007 and 2013.

The cohort study that provided the data for this analysis ended in 2013 in the locations we studied. Looking beyond this, full implementation of test-and-treat for HIV infection after 2016 (World Health Organization Citation2015a; National Medicine and Therapeutics Policy Advisory Committee and AIDS and TB Directorate Citation2016) brought about further reductions in the proportions of PLHIV who were undiagnosed and not on treatment in Zimbabwe (Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care Citation2016), and therefore at greatest risk of transmitting infection, and this could have accelerated the decline in HIV incidence. However, concerns remain that uninfected individuals’ exposure to HIV infection could continue to rise due to increasing behavioural disinhibition, particularly given recent reductions in support for national behaviour change and condom distribution and promotion programmes. To combat these concerns and speed up progress towards meeting its goal of ending AIDS by 2030, UNAIDS has called for urgent efforts to revive primary HIV prevention programmes, focussing on five pillars (UNAIDS Citation2017): combination prevention for adolescent girls, young women, and their male partners in high-prevalence locations; combination prevention programmes for key populations; strengthened national condom and behaviour change programmes; promoting voluntary medical circumcision of males; and offering pre-exposure prophylaxis to population groups with high HIV incidence. The results of this study also support re-establishing the counselling component within HIV testing and treatment services and, in particular, the need to differentiate, in counselling on primary and secondary HIV prevention, between individuals according to their behavioural, infection, and treatment circumstances. For uninfected individuals, WHO has launched a promising initiative to develop a risk differentiation tool to identify, characterize, and link high-risk individuals to relevant primary prevention services (World Health Organization Citation2018). A meta-analytic review found that for PLHIV on treatment, levels of unprotected sexual activity were higher among those who knew that receiving ART could reduce HIV transmission (Crepaz et al. Citation2004). Therefore, counselling on primary prevention, as well as strengthened counselling to reduce loss to follow-up from ART (Tenthani et al. Citation2014) and improve adherence (Bärnighausen et al. Citation2011), could help to reduce HIV incidence.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (304.9 KB)Notes

1 Simon Gregson and Constance Nyamukapa are both based at the Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Imperial College London, United Kingdom, and at the Manicaland Centre for Public Health Research, Biomedical Research and Training Institute, 10 Seagrave Road, Avondale, Harare, Zimbabwe. Please direct all correspondence to Simon Gregson, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Imperial College London, Norfolk Place, London W2 1PG, United Kingdom; or by E-mail: [email protected]

2 Data availability statement: Data from the Manicaland Study can be obtained from the project website (http://www.manicalandhivproject.org/data-access.html). Here we provide a core data set containing a sample of socio-demographic, sexual behaviour, and HIV-testing variables from all six rounds of the main survey, as well as data used in the production of recent academic publications. If further data are required, a data request form must be completed (available to download from our website) and submitted to [email protected]. If the proposal is approved, we will send a data sharing agreement, which must be agreed on before we release the requested data.

3 Acknowledgements: We are very grateful to the Manicaland Centre for Public Health Research team and to study participants in Manicaland, east Zimbabwe, for their kind assistance with the research.

4 Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the Wellcome Trust (award numbers: 084401/Z/07/B and 069516/Z/02/Z), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1161471), and by the joint MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis funding from the UK Medical Research Council and Department for International Development (MR/R015600/1). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Wellcome Trust, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, or the UK Medical Research Council.

5 Ethical approval for the Manicaland Study was provided by the Imperial College London Research Ethics Committee (ICREC_9_3_13) and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ/A/681).

References

- Baggaley, R., N. M. Ferguson, and G. P. Garnett. 2005. The epidemiological impact of antiretroviral use predicted by mathematical models: A review, Emerging Themes in Epidemiology 2: 9. https://doi.org/doi:10.1186/1742-7622-2-9

- Bärnighausen, T., K. Chaiyachati, N. Chimbindi, A. Peoples, J. Haberer, and M.-L. Newell. 2011. Interventions to increase antiretroviral adherence in subSaharan Africa: A systematic review of evaluation studies, The Lancet Infectious Diseases 11: 942–951. https://doi.org/doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70181-5

- Bezemer, D., F. De Wolf, M. C. Boerlijst, A. van Sighem, T. D. Hollingsworth, M. Prins, R. B. Geskus, L. Gras, R. A. Coutinho, and C. Fraser. 2008. A resurgent HIV-1 epidemic among men who have sex with men in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy, AIDS 22: 1071–1077. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282fd167c

- Catania, J. A., D. D. Chitwood, D. R. Gibson, and T. J. Coates. 1990. Methodological problems in AIDS behavioral research: Influences on measurement error and participation bias in studies of sexual behavior, Psychological Bulletin 108: 339–362. https://doi.org/doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.339

- Church, K., F. Kiweewa, A. Dasgupta, M. Mwangome, E. Mpandaguta, F. X. Gómez-Olivé, S. Oti, J. Todd, A. Wringe, E. Geubbels, A. Crampin, J. Nakiyingi-Miiro, C. Hayashi, M. Njage, R. G. Wagner, A. Ario, S. D. Makombe, O. Mugurungi, and B. Zaba. 2015. A comparative analysis of national HIV policies in six African countries with generalized epidemics, Bulletin of the World Health Organization 93: 457–467. https://doi.org/doi:10.2471/BLT.14.147215

- Cohen, M. S., Y. Q. Chen, M. McCauley, T. Gamble, M. C. Hosseinipour, N. Kumarasamy, G. J. Hakim, J. Kumwnda, B. Grinsztejn, J. H. S. Pilotto, S. V. Godbole, S. Mehendale, S. Chariyalertsak, B. R. Santos, K. H. Mayer, I. F. Hoffman, S. H. Eshleman, E. Piwowar-Manning, L. Wang, J. Makhema, L. A. Mills, G. De Bruyn, I. Sanne, J. Eron, J. Gallant, D. Havlir, S. Swindells, H. Ribaudo, V. Elharrar, D. Burns, T. Taha, K. Nielsen-Saines, D. D. Celentano, M. Essex, T. R. Fleming, and HPTN 052 Study Team. 2011. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy, New England Journal of Medicine 365: 493–505. https://doi.org/doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1105243

- Cremin, I., C. Nyamukapa, L. Sherr, T. B. Hallett, G. Chawira, S. Cauchemez, B. Lopman, G. P. Garnett, and S. Gregson. 2010. Patterns of self-reported behaviour change associated with receiving voluntary counselling and testing in a longitudinal study from Manicaland, Zimbabwe, AIDS and Behavior 14: 708–715. https://doi.org/doi:10.1007/s10461-009-9592-4

- Crepaz, N., T. A. Hart, and G. Marks. 2004. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior, JAMA 292: 224–236. https://doi.org/doi:10.1001/jama.292.2.224

- Delva, W., F. Meng, R. Beauclair, N. Deprez, M. Temmerman, A. Weite, and N. Hens. 2013. Coital frequency and condom use in monogamous and concurrent sexual relationships in Cape Town, South Africa, Journal of the International AIDS Society 16: 18034. https://doi.org/doi:10.7448/IAS.16.1.18034

- Dimbuene, Z. T., J. B. O. Emina, and O. Sankoh. 2014. UNAIDS ‘multiple sexual partners’ core indicator: Promoting sexual networks to reduce potential biases, Global Health Action 7: 23103. https://doi.org/doi:10.3402/gha.v7.23103

- Donnell, D., J. M. Baeten, J. Kiarie, K. K. Thomas, W. Stevens, C. R. Cohen, J. McIntryre, J. R. Lingappa, and C. Celum. 2010. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: A prospective cohort analysis, The Lancet 375: 2092–2098. https://doi.org/doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2

- Eaton, J. W., F. Takavarasha, C. Schumacher, O. Mugurungi, G. P. Garnett, C. A. Nyamukapa, and S. Gregson. 2014. Trends in concurrency, polygyny, and multiple sex partnerships during a decade of declining HIV prevalence in eastern Zimbabwe, The Journal of Infectious Diseases 210: S562–S568. https://doi.org/doi:10.1093/infdis/jiu415

- Elmes, J., M. Skovdal, K. Nhongo, H. Ward, C. Campbell, T. B. Hallett, C. Nyamukapa, P. J. White, and S. Gregson. 2017. A reconfiguration of the sex trade: How social and structural changes in Eastern Zimbabwe left women involved in sex work and transactional sex more vulnerable, Public Library of Science One 12: e0171916. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171916

- Fonner, V. A., J. A. Denison, C. E. Kennedy, K. O’Reilly, and M. Sweat. 2012. Voluntary counseling and testing for changing HIV-related risk behavior in developing countries, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 9: CD001224. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001224.pub4

- Granich, R. M., C. F. Gilks, C. Dye, K. M. De Cock, and B. Williams. 2009. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: A mathematical model, The Lancet 373: 48–57. https://doi.org/doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9

- Gregson, S., T. Zhuwau, J. Ndlovu, and C. Nyamukapa. 2002. Methods to reduce social desirability bias in sex surveys in low-development settings, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 29: 568–575. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/00007435-200210000-00002

- Gregson, S., O. Mugurungi, J. Eaton, A. Takaruza, R. Rhead, R. Maswera, J. Mutsvangwa, J. Mayini, M. Skovdal, R. Schaefer, T. Hallett, L. Sherr, S. Munyati, P. R. Mason, C. Campbell, G. P. Garnett, and C. A. Nyamukapa. 2017. Documenting and explaining the HIV decline in east Zimbabwe: The Manicaland general population cohort, BMJ Open 7: e015898. https://doi.org/doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015898

- Havlir, D., S. Lockman, H. Ayles, J. Larmarange, G. Chamie, T. Gaolathe, C. Iwuji, S. Fidler, M. R. Kamya, S. Floyd, J. Moore, R. Hayes, M. Petersen, and F. Dabis. 2020. What do the universal test and treat trials tell us about the path to HIV epidemic control? Journal of the International AIDS Society 23: e25455. https://doi.org/doi:10.1002/jia2.25455

- Hayes, R., D. Donnell, S. Floyd, N. Mandla, J. Bwalya, K. Sabapathy, B. Yang, M. Phiri, A. Schaap, S. H. Eshleman, E. Piwowar-Manning, B. Kosloff, and for the HPTN 071 (PopART) Study Team. 2019. Effect of universal testing and treatment on HIV incidence — HPTN 071 (PopART), New England Journal of Medicine 381: 207–218. https://doi.org/doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1814556

- Iwuji, C. C., J. Orne-Gliemann, J. Larmarange, E. Balestre, R. Thiebaut, F. Tanser, N. Okesola, T. Makowa, J. Dreyer, K. Herbst, N. McGrath, T. Bärnighausen, S. Boyer, T. De Oliveira, C. Rekacewicz, B. Bazin, M.-L. Newell, D. Pillay, and F. Dabis. 2018. Universal test and treat and the HIV epidemic in rural South Africa: A phase 4, open-label, community cluster randomised trial, The Lancet HIV s2352–s3018(17): 30205–30209. doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30205-9

- Kim, A. A., I. Mukui, P. Young, J. Mirjahangir, S. Mwanyumba, J. Wamicwe, N. Bowen, L. Wiesner, L. Ng’ang’a, and K. M. De Cock. 2016. Undisclosed HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy use in the Kenya AIDS indicator survey 2012: Relevance to national targets for HIV diagnosis and treatment, AIDS 30: 2685–2695. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000001227

- Langhaug, L., L. Sherr, and F. M. Cowan. 2010. How to improve the validity of sexual behaviour reporting: Systematic review of questionnaire delivery modes in developing countries, Tropical Medicine and International Health 15: 362–381. https://doi.org/doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02464.x

- Legemate, E. M., J. A. C. Hontelez, C. W. N. Looman, and S. J. de Vlas. 2017. Behavioural disinhibition in the general population during the antiretroviral therapy roll-out in Sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review and meta-analysis, Tropical Medicine and International Health 22: 797–806. https://doi.org/doi:10.1111/tmi.12885

- Lopman, B., C. A. Nyamukapa, P. Mushati, M. Wambe, Z. Mupambireyi, P. R. Mason, G. P. Garnett, and S. Gregson. 2008. HIV incidence in 3 years of follow-up of a Zimbabwe cohort—1998–2000 to 2001–03: Contributions of proximate and underlying determinants to transmission, International Journal of Epidemiology 37: 88–105. https://doi.org/doi:10.1093/ije/dym255

- Luke, N., and K. M. Kurz. 2002. Cross-generational and Transactional Sexual Relations in sub-Saharan Africa: Prevalence of Behavior and Implications for Negotiating Safer Sexual Practices. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women.

- Makhema, J., K. E. Wirth, M. P. Holme, M. Mmalane, E. Kadima, U. Chakalisa, K. Bennett, J. Leidner, K. Manyake, A. M. Mbikiwa, S. V. Simon, R. Letlhogile, K. Mukokomani, E. van Widenfelt, S. Moyo, R. Lebelonyane, M. G. Alwano, K. M. Powis, S. Dryden-Peterson, C. Kgathi, V. Novitsky, J. Moore, P. J. Bachanas, W. Abrams, L. Block, S. El-Halibi, T. Marukutira, L. A. Mills, C. Sexton, E. Raizes, S. Gaseitsiwe, H. Bussmann, L. Okui, O. John, R. L. Shapiro, S. Pals, H. Michael, M. Roland, V. DeGruttola, Q. Lei, R. Wang, E. J. Tchetgen Tchetgen, M. Essex, and S. Lockman. 2019. Universal testing, expanded treatment, and incidence of HIV infection in Botswana, New England Journal of Medicine 381: 230–242. https://doi.org/doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1812281

- McGrath, N., J. Eaton, T. Barnighausen, F. Tanser, and M-L. Newell. 2013. Sexual behaviour in a rural high HIV prevalence South African community: time trends in the antiretroviral treatment era, AIDS 27(15): 2461–2470. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000432473.69250.19

- National Medicine and Therapeutics Policy Advisory Committee, and AIDS and TB Directorate. 2016. Guidelines for Antiretroviral Therapy for the Prevention and Treatment of HIV in Zimbabwe. Harare, Zimbabwe: Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care.

- Nguyen, V.-K., N. Bajos, F. Dubois-Arber, J. O’Malley, and C. M. Pirkle. 2011. Remedicalizing an epidemic: From HIV treatment as prevention to HIV treatment is prevention, AIDS 25: 291–293. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283402c3e

- O’Donnell, M., M. Khozombahm, and S. Mudenda. 2002. The Livelihoods of Commercial Sex Workers in Binga. London: Save the Children Fund.

- PHIA Project. 2020. Population-based HIV impact assessment. Available: https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/ (accessed: 18 September 2020).

- Reniers, G., E. Slaymaker, J. Nakiyingi-Miiro, C. Nyamukapa, A. C. Crampin, K. Herbst, M. Urassa, F. Otieno, S. Gregson, M. Sewe, D. Michael, T. Lutalo, V. Hosegood, I. Kasamba, A. Price, D. Nabukalu, E. Mclean, and B. Zaba. 2014. Mortality trends in the era of antiretroviral therapy: Evidence from the network for Analysing Longitudinal Population Based HIV/AIDS data on Africa (ALPHA), AIDS 28: S533–S542. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000496

- Rhead, R., J. Elmes, E. Otobo, K. Nhongo, A. Takaruza, C. Nyamukapa, and S. Gregson. 2018. Do female sex workers have lower uptake of HIV treatment services than non-sex workers? A cross-sectional study from east Zimbabwe, BMJ Open 8, e018751. https://doi.org/doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018751

- Rhead, R., C. Masimirembwa, G. Cooke, A. Takaruza, C. Mutsimhu, C. Nyamukapa, and S. Gregson. 2016. Might ART adherence estimates be improved by combining biomarker and self-report data? Public Library of Science One 11(12): e0167852. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0167852

- Rucinski, K. B., S. E. Rutstein, K. A. Powers, D. K. Pasquale, A. M. Dennis, S. Phiri, M. C. Hosseinipour, G. Kamanga, D. Nsona, C. Massa, I. F. Hoffman, W. C. Miller, and A. E. Pettifor. 2018. Sustained sexual behavior change after acute HIV diagnosis in Malawi, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 45: 741–746. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000873

- Schaefer, R., S. Gregson, and C. Benedikt. 2019. Widespread changes in sexual behaviour in Eastern and Southern Africa: Challenges to achieving global HIV targets? Longitudinal analyses of nationally representative surveys, Journal of the International AIDS Society 22: e25329. https://doi.org/doi:10.1002/jia2.25329

- Schaefer, R., S. Gregson, J. W. Eaton, O. Mugurungi, R. Rhead, A. Takaruza, R. Maswera, and C. Nyamukapa. 2017. Age-disparate relationships and HIV incidence in adolescent girls and young women: Evidence from a general-population cohort in Zimbabwe, AIDS 31: 1461–1470. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000001506

- Slaymaker, E. 2004. A critique of international indicators of sexual risk behaviour, Sexually Transmitted Infections 80: ii13–ii21. doi:10.1136/sti.2004.011635

- Slaymaker, E., J. Todd, M. Urassa, K. Herbst, N. McGrath, R. Newton, D. Nabukalu, T. Lutalo, A. Crampin, S. Gregson, K. Tomlin, K. Risher, G. Reniers, M. Marston, C. Kabudula, B. Zaba. 2018. HIV incidence trends among the general population in Eastern and Southern Africa 2005–2016. 22nd International AIDS Conference. Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Steen, R., J. A. C. Hontelez, O. Mugurungi, A. Mpofu, S. M. Matthjsse, S. J. De Vlas, G. Dallabetta, and F. M. Cowan. 2019. Economy, migrant labour and sex work: Interplay of HIV epidemic drivers in Zimbabwe over three decades, AIDS 33: 123–131. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000002066

- Stolte, I. G., N. H. T. M. Dukers, R. B. Geskus, R. A. Coutinho, and J. B. F. de Wit. 2004. Homosexual men change to risky sex when perceiving less threat of HIV/AIDS since availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy: A longitudinal study, AIDS 18: 303–309. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/00002030-200401230-00021

- Tanser, F., T. Barninghausen, E. Grapsa, J. Zaidi, and M.-L. Newell. 2013. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, Science 339: 966–971. https://doi.org/doi:10.1126/science.1228160

- Tenthani, L., A. D. Haas, H. Tweya, A. Jahn, J. J. van Oosterhout, F. Chimbwandira, Z. Chirwa, W. Ng’ambi, A. Bakali, S. Phiri, L. Myer, F. Valeri, M. Zwahlen, G. Wandeler, and O. Keiser. 2014. Retention in care under universal antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women (‘Option B+’) in Malawi, AIDS 28: 589–598. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000143

- Tlhajoane, M., T. Masoka, E. Mpandaguta, R. Rhead, K. Church, A. Wringe, N. Kadzura, N. Arinaminpathy, C. Nyamukapa, N. Schur, O. Mugurungi, M. Skovdal, J. W. Eaton, and S. Gregson. 2018. A longitudinal review of national HIV policy and progress made in health facility implementation in eastern Zimbabwe, Health Research Policy and Systems 16: 92. https://doi.org/doi:10.1186/s12961-018-0358-1

- UNAIDS. 2017. HIV Prevention 2020 Road Map: Accelerating HIV Prevention to Reduce New Infections by 75%. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- UNAIDS. 2019. Global AIDS Monitoring 2020: Indicators for Monitoring the 2016 Political Declaration on Ending AIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- UNAIDS. 2020. Seizing the Moment: Tackling Entrenched Inequalities to End Epidemics. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- Velasco-Hernandez, J. X., H. B. Gershengorn, and S. M. Blower. 2002. Could widespread use of combination antiretroviral therapy eradicate HIV epidemics? The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2: 487–493. https://doi.org/doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00346-8

- Venkatesh, K. K., G. de Bruyn, M. N. Lurie, L. Mohapi, P. M. Pronyk, M. Moshabela, E. Marinda, G. E. Gray, E. W. Triche, and N. A. Martinson. 2010. Decreased sexual risk behavior in the era of HAART among HIV-infected urban and rural South Africans attending primary care clinics, AIDS 24: 2687–2696. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833e78d4

- Venkatesh, K. K., T. P. Flanigan, and K. H. Mayer. 2011. Is expanded HIV treatment preventing new infections? Impact of antiretroviral therapy on sexual risk behaviors in the developing world, AIDS 25: 1939–1949. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834b4ced

- Wanyenze, R. K., M. R. Kamywa, R. Fatch, H. Mayanja-Kizza, S. Baveewo, G. Szekeres, D. R. Bangsberg, T. Coates, and J. A. Hahn. 2013. Abbreviated HIV counselling and testing and enhanced referral to care in Uganda: A factorial randomised controlled trial, The Lancet Global Health 1: e137–e145. https://doi.org/doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70067-6

- Wawer, Maria J., Ronald H. Gray, Nelson K. Sewankambo, David Serwadda, Xianbin Li, Oliver Laeyendecker, Noah Kiwanuka, Godfrey Kigozi, Mohammed Kiddugavu, Thomas Lutalo, Fred Nalugoda, Fred Wabwire-Mangen, Mary P. Meehan, and Thomas C. Quinn. 2005. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital Act, by Stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda, The Journal of Infectious Diseases 191: 1403–1409. https://doi.org/doi:10.1086/429411

- WHO, and UNAIDS. 2007. Guidance on Provider-Initiated HIV Testing and Counselling in Health Facilities. Geneva: WHO.

- World Bank. 2020. National accounts data, and OECD national accounts data files. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD?locations=ZW (accessed: 30 September 2020).

- World Health Organization. 2010. Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. 2013. Consolidated Guidelines on the use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. 2015a. Guideline on When to Start ART and on pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. 2015b. Progress Brief: Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention in 14 Priority Countries in East and Southern Africa. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. 2015c. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Testing Services - 5Cs: Consent, Confidentiality, Counselling, Correct Results and Connection. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. 2018. Cascade data use manual: to identify gaps in HIV and health services for programme improvement. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. 2020. HIV/AIDS: Data and statistics. Available: https://www.who.int/hiv/data/en/ (accessed: 17 September 2020).

- Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care. 2016. Zimbabwe Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment Survey: ZIMPHIA 2015-2016. Harare, Zimbabwe: Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care.