Abstract

Family formation, a process that includes union formation, fertility, and their timing and order, has become increasingly diverse and complex in Europe. We examine how the relationship between socio-economic background and family formation has changed over time in France, Italy, Romania, and Sweden, using first wave Generations and Gender Survey data. Competing Trajectories Analysis, a procedure which combines event-history analysis with sequence analysis, allows us to examine family formation as a process, capturing differences in both the timing of the start of family formation and the pathways that young adults follow. Regarding timing, socio-economic background differences in France and Sweden have remained relatively small, whereas in Italy and Romania higher parental education has become more strongly associated with postponement. Pathways tend to diverge by socio-economic background, particularly in Sweden and France. These results indicate that while family formation patterns have changed, they continue to be stratified by socio-economic background.

Introduction

Over the last decades, there has been a diversification and destandardization of family formation patterns in Europe (Brückner and Mayer Citation2004; Buchmann and Kriesi Citation2011). Marriage rates have declined, and unmarried cohabitation and non-marital childbearing have risen (Lesthaeghe Citation2010; Perelli-Harris et al. Citation2012). Some scholars have argued that these changes have contributed to increasing social inequality, because of the rise in more precarious forms of family formation, particularly among the disadvantaged (Perelli-Harris et al. Citation2010b; Amato et al. Citation2015). This idea was well captured by McLanahan (Citation2004) with the notion of ‘Diverging Destinies’, whereby the disadvantaged are increasingly more likely to experience single parenthood and/or divorce, and less likely to marry. This raises the question of whether the children of the disadvantaged have also become increasingly likely to experience these family formation pathways.

While there are many studies describing and explaining the societal changes in family formation in Europe, few studies have examined how the effect of socio-economic background on family formation has changed over time. Our study extends the literature on the influence of socio-economic background on the process of family formation in Europe by studying how this relationship has evolved over time and how similar this process is across countries. Thus, this study addresses two questions: (1) to what extent the relationship between socio-economic background and family formation has changed over time; and (2) how similar this change has been in different European country contexts.

According to the Second Demographic Transition (SDT) theory, European differences in family formation patterns are expected to become smaller, the more the SDT spreads across European countries (Lesthaeghe Citation2010). Some research (e.g. Billari and Liefbroer Citation2010) has suggested, however, that cross-national differences may rather be increasing. This study examines how the effect of socio-economic background on family formation has changed over time in four European countries, selecting two countries which can be described as front runners in the SDT (Sweden and France) and two countries that can be described as laggards (Italy and Romania). Although the Generation and Gender Survey (GGS) data cover many European countries, studying these patterns across all the countries would lead to an overload of information and reduce the clarity and interpretability of the results. Therefore, we opt for a comparison of four quite different countries spread across the continent. The four countries we focus on—France, Italy, Sweden, and Romania—allow us to gauge how similar the developments across birth cohorts have been with regard to the links between socio-economic background and family formation across Europe.

Examining socio-economic background, rather than the individual’s own socio-economic status as mostly done in previous research (Blossfeld and Huinink Citation1991; Perelli-Harris et al. 2010; Zimmermann and Konietzka Citation2018), adds to the literature on stratification, as socio-economic background is an ascribed rather than an achieved characteristic. Thus, if the association between socio-economic background and family formation is persistent, it suggests that intergenerational social inequality remains important. Moreover, socio-economic background shapes educational opportunities, implying that educational attainment partially mediates the influence of socio-economic background (Blau and Duncan Citation1967). The aim of this paper, however, is not to examine to what extent the total influence of parental education on family formation is mediated by an individual’s own educational attainment, but rather to examine to what extent the total association between parental education and family formation has changed in different European countries.

Previous research on the link between socio-economic background and family formation across time and space has typically focused on specific demographic events. These studies show differences between countries in the timing of union formation and choice of marriage versus cohabitation (Hoem et al. Citation2009; Wiik Citation2009; Brons et al. Citation2017) and in the relationship context in which children are born (McLanahan and Percheski Citation2008; Perelli-Harris et al. 2010; Koops et al. Citation2017). Yet, examining separate transitions does not provide a complete picture of the comprehensive consequences of socio-economic background. Conceptualizing and analysing family formation as a process has merit, as family events are clearly interrelated. It is important to examine sequences of family events, as sequences contain rich information not only about the timing, quantum, and ordering of family events (Billari Citation2001), but also on the duration of time spent in specific family states (Studer and Ritschard Citation2016). Existing studies using sequence analysis and latent class analysis have indeed allowed a detailed examination of the diversity in family pathways in Europe (Sironi et al. Citation2015; Lesnard et al. Citation2016; Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos Citation2016; Schwanitz Citation2017; Van Winkle Citation2018). However, hardly any attention has been paid to differences in family pathways between young adults coming from different socio-economic backgrounds, with the notable exception of Sironi et al. (Citation2015), who compared Italy and the US.

Background

Socio-economic background and the family formation process over time

There are various reasons as to why family formation behaviours are stratified according to socio-economic background. Compared with those from lower socio-economic backgrounds, children from higher socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to be socialized with values of self-actualization and autonomy, making them more likely to focus on their career in the early stages of young adulthood, while postponing family commitments, particularly marriage and parenthood (Billari et al. Citation2019). On the other hand, youths from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to engage in risky behaviours, such as unprotected sexual activity (Miller Citation2002), thereby increasing the risk of becoming a teenage parent. Across Europe disadvantaged youths are not only more likely to start family formation early, but are also more likely to become parents outside marriage and to a lesser extent outside any cohabiting union (Perelli-Harris et al. Citation2010b; Koops et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, Brons et al. (Citation2017) found that across Europe young adults from high socio-economic backgrounds postpone union formation. In addition, they observed that this relationship is partly mediated by young adults’ own education. However, these studies have not covered to what extent the association between socio-economic background and family formation developed during a century of rapid change in family formation behaviour. During the first half of the twentieth century, the family formation process had become highly standardized. The vast majority of young adults left the parental home in order to marry and start a family (Mayer Citation2004). Since the Second World War, the rise in unmarried cohabitation, divorce, and parenthood outside marriage, and the decrease in marriage and fertility, have led to a diversification of family formation pathways. Lesthaeghe and Van de Kaa (Citation1986), in their SDT thesis, saw these family formation changes as the result of cultural change. According to SDT theory, the highly educated segment of the population are trendsetters for new living arrangements, such as unmarried cohabitation (although in an adjustment of the original theory it has also been acknowledged that in some national contexts these new behaviours were initiated by the lower social strata [Lesthaeghe Citation2014]). Nonetheless, SDT theory assumes that the demographic trends diffuse across all layers of society. This appears to imply that the link between socio-economic background and family formation patterns will become weaker across birth cohorts. In our reading, differences between socio-economic background will increase at the start of the SDT, as children from families with high socio-economic backgrounds adopt new family formation behaviours earlier than children from families with low socio-economic backgrounds. However, these differences will decrease again as these new family formation patterns become more widespread, and may eventually even lead to smaller differences overall in family formation by socio-economic background than before the SDT.

SDT theory has not remained unchallenged. Main criticisms include that it is merely a continuation of the first demographic transition and that the SDT applies mainly to Northern and Western European countries (Coleman Citation2003; Sobotka Citation2008; Zaidi and Morgan Citation2017). If the second point is true, the influence of socio-economic background may have changed in Northern and Western European countries, but not (so much) in Southern and Eastern countries. Lesthaeghe, however, insisted that the SDT, having started in Northern and Western Europe, later spread to other developed countries, including those in Southern and Eastern Europe (Lesthaeghe Citation2010). We can therefore infer that the influence of socio-economic background on family formation patterns changed later in Southern and Eastern Europe than in Northern and Western European countries. With respect to Eastern Europe, scholars have even claimed that only after the fall of the Iron Curtain was the SDT able to spread to the former Soviet Union countries (Frejka Citation2008; Potârcă et al. Citation2013).

Another criticism of SDT theory is that it assumes an irreversible cultural change, while relatively little attention is paid to changes in economic conditions (Zaidi and Morgan Citation2017). Perelli-Harris and Gerber (Citation2011) suggested that new family forms, such as unmarried cohabitation, are not chosen because of individualistic preferences, but rather due to financial necessity, and called this explanation the Pattern of Disadvantage (PoD). Furthermore, they claimed that childbearing outside marriage is usually chosen by the lower educated (Perelli-Harris et al. Citation2010b; Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos Citation2016). The importance of economic conditions for family formation was also stressed by Mills and Blossfeld (Citation2013), who emphasized that the process of globalization has led to rising uncertainty about individual economic prospects, creating a need for people to opt for flexible unions, thus preferring cohabitation over marriage. Both the PoD and globalization theories suggest that socio-economic status may be one of the main drivers of the diversification in family formation patterns and that differences in family formation between individuals from different family backgrounds will remain.

The SDT and PoD perspectives lead to different expectations about how the relationship between socio-economic background and family formation will change across cohorts. From an SDT perspective, we would expect those from higher socio-economic backgrounds to initiate new demographic behaviours, both in terms of timing (i.e. postponement of family formation) and in terms of the type of family formation patterns (i.e. unmarried cohabitation and childbearing outside marriage). Thus, at the initial stage of the SDT there will be a divergence between those of higher and lower socio-economic backgrounds, as the former will initiate these new family behaviours, whereas the latter will not and thus be more likely to follow more conservative family trajectories. However, SDT theory suggests that these new behaviours will eventually be adopted by all members of society, thus leading to a convergence across all layers of society. This will ultimately lead to more similarity in family formation pathways between individuals of different socio-economic backgrounds.

From the PoD perspective, the strength of the link between socio-economic background and family formation depends on the spread of poverty among groups from lower socio-economic backgrounds. If the economic circumstances of the lower social strata worsen, children from disadvantaged families will become less able to afford marriage, whereas children from higher socio-economic backgrounds will still have the financial safety net to support marriage and a family. This could imply the postponement of family formation for those of lower relative to those of higher socio-economic backgrounds. At the same time, those with few parental resources may need to cohabit for financial reasons. Furthermore, as described earlier, young adults from low socio-economic backgrounds may have little confidence in their career and marriage prospects, increasing the chance of early parenthood. Therefore, from the PoD perspective we would expect unmarried cohabitation and particularly childbearing outside marriage to be phenomena that will occur among young adults from families of low rather than high socio-economic backgrounds. Thus, while the SDT is a developmental theory on change in family formation patterns, the PoD perspective views family formation change as more directly linked with changes in economic circumstances.

Country differences

In this paper, we compare four countries that differ in their economic, cultural, and institutional development, as well as in the way their family formation patterns have developed over time. In the 1960s and 1970s, family policies in Sweden, France, and Italy increasingly targeted individual family members, particularly women and children, and changes were made to divorce and abortion laws (Haas Citation1996; Martin Citation2010; Rose and Vignoli Citation2011). Sweden developed into a social democratic welfare regime granting all social classes access to childcare, whereas France became a corporatist welfare regime, with less individualization, but strong financial support for childcare. At the same time, Italy developed into a more familialist welfare regime with limited welfare provisions, providing little support for women to work alongside having a family (Esping-Andersen Citation1990). Finally, during the communist era, Romania had a pronatalist welfare regime in which abortion was forbidden, whereas after the fall of the communist regime family policy provisions decreased sharply, especially for unemployed women (Fodor et al. Citation2002; Frejka Citation2008). As a result, after the fall of the Iron Curtain, fertility dropped to well below replacement level in Romania (Thornton and Philipov Citation2009). Whereas fertility levels in most Western European countries have also decreased to below replacement level, both Sweden and France differ in that they have kept fertility relatively close to replacement level (Sobotka Citation2008). Italy, on the other hand, developed into a low-fertility country in the second half of the twentieth century, with one of the lowest fertility levels in Europe (Rose et al. Citation2008).

Culturally, these four countries experienced the SDT at quite different moments during their history, leading to differences in the onset and magnitude of several family behaviours. Sweden is often considered the forerunner in the SDT, as the first country to display increased levels of unmarried cohabitation and childbearing outside marriage. However, it must be noted that this behaviour started among individuals of all socio-economic backgrounds (Hoem Citation1986), contrary to the expectation of the SDT. Billari and Liefbroer (Citation2010) compared family-related trends for the different countries by birth cohort, and show that in Sweden almost 50 per cent of the 1940–49 birth cohort entered cohabitation rather than marrying directly as their first union, whereas these percentages were much lower for France (around 15 per cent) and Romania (less than 5 per cent). The increase in cohabitation started later in France, while in Romania the percentage increased to 17 per cent only in the 1970–79 cohort, and the same birth cohort in Sweden and France were already seeing percentages close to 90 per cent. In Romania, unmarried cohabitation is less accepted as an alternative to marriage and is seen rather as a stage before marriage when the couple lacks the resources to marry (Apostu Citation2013). In contrast, France and Sweden had developed legal protections for cohabiters by the end of the twentieth century (Bradley Citation2001; Perelli-Harris and Gassen Citation2012). In Italy, studies have shown a slow diffusion of unmarried cohabitation, partly due to its Catholic heritage (Rose et al. Citation2008). Statistics on the diffusion of childbearing outside marriage show a similar trend, although for Romania this percentage has remained quite stable at around 12 per cent for birth cohorts between 1930 and 1979 (Billari and Liefbroer Citation2010). Regarding the timing of entry into marriage and parenthood, there has been a strong increase across these birth cohorts in the median age of both events for France, Sweden, and Italy, whereas for Romania the increase in the median age was limited.

Data and methods

Data

This study uses data from the first wave of the GGS harmonized histories, version 4.2 (Vikat et al. Citation2007; Perelli-Harris et al. Citation2010a). Data from Italy were collected in 2003, for France and Romania in 2005, and for Sweden in 2012–13. The GGS contains rich information on family formation histories, including the start and end dates of all married and unmarried cohabiting relationships and dates of all births. Using this information, retrospective family histories can be constructed. As a measure of socio-economic background, we opt for the parents’ educational level. Although socio-economic background can also be captured by other indicators, such as parents’ occupational status, their educational level may better reflect the cultural, and to a lesser extent also the economic, resources of the parental home (Lyngstad Citation2006). The GGS includes information on the educational attainment of the mother and father, from which we construct a measure by taking the higher of the two parents’ highest educational level, which reduces the number of missing values on this variable to about 5 per cent. Based on the International Standard Level of Education (ISLED) scale, a continuous, country-comparative measure of educational level (Schröder and Ganzeboom Citation2013) as recorded for the GGS data by Brons and Mooyaart (Citation2018), parental education is recoded into three categories: low (ISLED < 33), medium (ISLED 33–66), and high (ISLED > 66).

We focus on four countries that differ in the timing of the onset of the SDT and in their welfare systems. The key aim is to examine the relationship between socio-economic background and family formation changes across cohorts, more precisely three birth cohorts (1925–44, 1945–64, and 1965–89) within four countries (Sweden, France, Italy, and Romania). Descriptive statistics on parental education, the sex and cohort distributions of the sample members, and the number of observations can be found in .

Table 1 Descriptive information on the sample for the four selected countries

Analytical strategy

Our focus is on how parental education is associated with both the timing of the start of the family formation process and the course of family formation after that start. To study this issue empirically, we use Competing Trajectories Analysis (CTA) (Studer et al. Citation2018). First, event-history analysis is used to study the timing of the first event in the family formation domain. In our usage of CTA, we examine the median age at entry into family formation based on Kaplan–Meier estimates to capture timing differences in the start of the family formation process. Next, sequence analysis is used to create a meaningful typology of family formation pathways that follow after this first family event has occurred, and the resulting clusters are used as alternative outcomes in a competing risk event-history model. CTA solves a key problem of sequence analysis, as the latter often uses a fixed age range in which sequences differ mainly in the timing of the first event, which makes clustering solutions less clear (Studer et al. Citation2018). CTA allows for a better distinction between countries in types of pathways, especially with multiple countries showing wide variation in the median timing of the first family event.

Creating a typology of family formation pathways

For all respondents, we construct family formation sequences that start at the moment that the first family event occurs (i.e. when the individual’s state switches from single and childless to any of the other family states). The family formation sequences span a period of six years after the first event occurred. A six-year time frame is used as it allows for key characteristics of the early family formation processes to be observed. Studer et al. (Citation2018) used a time frame of five years, but found very similar results with time frames of four or six years. Each month respondents are assigned to one of the following six states: unmarried cohabitation (‘cohabiting’), marriage (‘married’), parenthood outside a cohabiting relationship (‘no partner + child’), having a child in a cohabiting relationship (‘cohabiting + child’), having a child within marriage (‘married + child’), and finally not being in any cohabiting relationship and having no child (‘no partner’). Divorce or separation occurs within six years for only 9.6 per cent of the respondents, and in the vast majority of cases (75 per cent) this is a dissolution of a cohabiting union without children. As there are relatively few observations categorized as ‘no partner’ or ‘no partner with child’, we do not split this state into multiple states (e.g. divorced, separated, etc.), each of which would contain only a small number of observations. It is important to note that having a child does not necessarily imply that the respondent is living with the child. Furthermore, we do not distinguish between having one or more children.

We extract family formation sequences from respondents’ retrospective histories between ages 15 and 45. This means that cases are censored if: (1) a respondent did not experience any family formation event; (2) the first family event occurred at age 40 or older; or (3) the first family formation event was less than six years before the date of interview. Although the clusters are based on family formation pathways between ages 15 and 45 across all birth cohorts, we display only cumulative entry into the different family pathways up to age 30 for each cohort. As interviews were conducted in 2003 and 2005 in France, Italy, and Romania, this means that in the 1965–89 cohort many cases are censored as either they had not yet started their family trajectory at the time of the survey or the start of their family trajectory was after 1998 (i.e. less than six years before the survey was taken). This results in few fully observed family formation pathways past age 30, hence our opting for this age range for all cohorts in order to obtain comparable graphs (results up to age 40 for the 1925–44 and 1945–64 cohorts are available on request).

For the clustering of the sequences we make use of the TraMineR and WeightedCluster packages in ‘R’ (Gabadinho et al. Citation2011; Studer Citation2013). We choose Optimal Matching (Abbott and Tsay Citation2000) with substitution costs based on the transition rates between family states in the data to calculate distances between all six-year family formation sequences. Finally, hierarchical clustering (Ward’s method) is used to generate the optimal number of clusters (see supplementary material, Appendix C, for details).

Analysing differences by parental education

First, median ages at which the first family formation event occurred by country, birth cohort, sex, and parental education group are presented, based on Kaplan–Meier estimates. Next, the predicted cumulative incidence functions of entry into each type of family formation pathway for each country, birth cohort, and parental education group are estimated non-parametrically and visualized using the R-cmprsk package (Scrucca et al. Citation2010). Gray’s tests are conducted to verify whether the predicted cumulative incidence rates differ between groups with different levels of parental education (Gray Citation1988). We discuss variation between parental education groups only if the predicted cumulative incidence rates for these groups are statistically significant. Details on the significance of all tests can be found in the supplementary material, Appendix B (Tables B1–B4).

Results

Family formation pathways

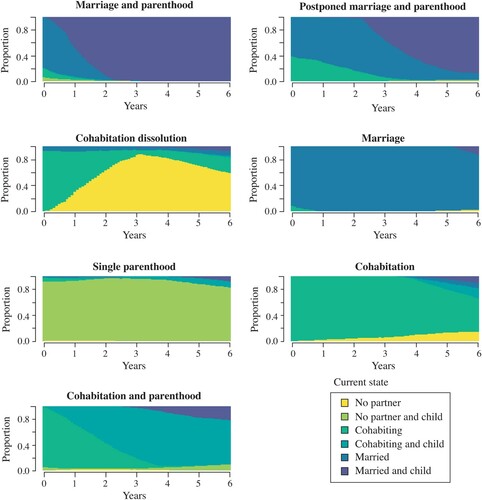

Based on the sequence analysis, seven family formation pathways can be distinguished (see ). We provide names for the clusters that describe their distinguishing features. The first cluster (Marriage and parenthood; 44 per cent) portrays the traditionally most ‘socially acceptable’ pathway, where marriage is the first family formation event, quickly followed by having a first child. The second cluster (Postponed marriage and parenthood; 19 per cent) is quite similar to the first, but a higher proportion of people cohabit prior to marriage, and childbearing within marriage does not generally start until 2.5 years after the union. We consider this a more modern version of the first cluster, given that family formation is more delayed and more often involves unmarried cohabitation. The third cluster (Cohabitation dissolution; 3 per cent) comprises respondents who experience the dissolution of their first cohabiting union. Some enter a new union relatively soon, whereas others do not. The fourth cluster (Marriage; 10 per cent) consists of people who marry but do not enter parenthood within the first six years of their family formation pathway. The fifth cluster (Single parenthood; 4 per cent) is characterized by entry into single parenthood as the start of the family formation pathway. The sixth cluster (Cohabitation; 12 per cent) is composed mainly of people who remain cohabiting for six years, although some enter a different family state towards the end of the six-year period. The final cluster (Cohabitation and parenthood; 7 per cent) consists of respondents who enter a cohabiting union in which most have a child within three years.

Figure 1 A typology of family formation pathways

Note: Seven distinct family formation pathway types, covering the six-year period after the first family formation event, were distinguished using hierarchical clustering, Ward method.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Generation and Gender Survey, first wave data: Italy (2003), France (2005), Romania (2005), Sweden (2012–13).

Results by country

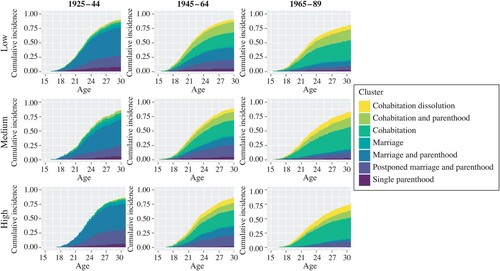

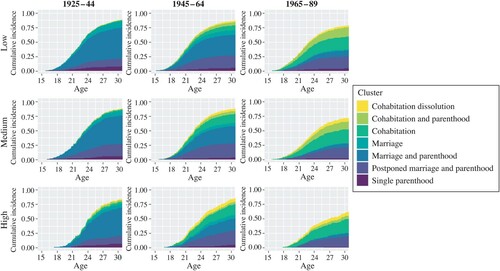

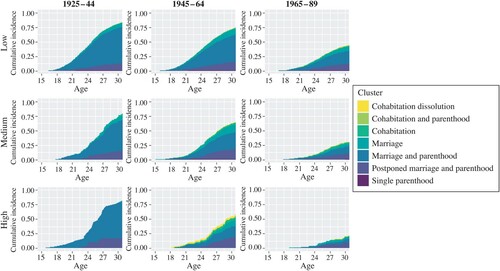

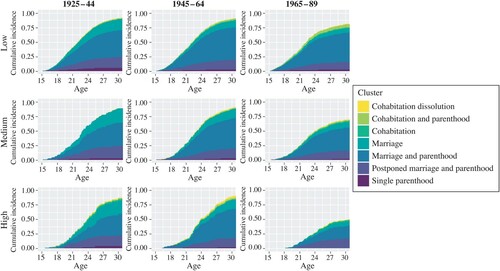

Now we examine socio-economic background differences in the timing of onset of family formation and in the family pathways chosen after the start of family formation, as well as how these socio-economic background differences vary across cohorts and countries. For each country, presents information on the median age of entry into family formation by sex for each parental education group and birth cohort. These results are split for men and women, since there are substantial sex differences in the timing of family formation (Winkler-Dworak and Toulemon Citation2007). display the predicted cumulative entry into different family formation pathways up to age 30 for, from left to right, the earliest (1925–44), middle (1945–64), and most recent (1965–89) cohorts, and from top to bottom, those with low, medium, and high parental education. We discuss the results in the order in which the SDT (may have) occurred in each country, with Sweden first, followed by France, Italy, and finally Romania. The predicted cumulative entry graphs do not only show the prevalence of different types of family formation pathways, but also their timing. When curves are steep and high this indicates that entry into family formation pathways occurs at an early age, whereas if curves are less steep and lower this indicates that family formation is postponed.

Figure 2 Predicted cumulative entry into family formation pathways by parental education and birth cohort in Sweden

Note: From left to right: cohorts 1925–44, 1945–64, and 1965–89. From top to bottom: low parental education, medium parental education, high parental education.

Source: As for .

Figure 3 Predicted cumulative entry into family formation pathways by parental education and birth cohort in France

Note: From left to right: cohorts 1925–44, 1945–64, and 1965–89. From top to bottom: low parental education, medium parental education, high parental education.

Source: As for .

Figure 4 Predicted cumulative entry into family formation pathways by parental education and birth cohort in Italy

Note: From left to right: cohorts 1925–44, 1945–64, and 1965–89. From top to bottom: low parental education, medium parental education, high parental education.

Source: As for .

Figure 5 Predicted cumulative entry into family formation pathways by parental education and birth cohort in Romania

Note: From left to right: cohorts 1925–44, 1945–64, and 1965–89. From top to bottom: low parental education, medium parental education, high parental education.

Source: As for .

Table 2 Median entry into family formation in four selected countries, split by sex, cohort, and parental education

Sweden

On examining the results in for Sweden, we observe little difference in median age of entry into family formation between those with low, medium, and high parental education, with a maximum difference of 1.5 years for both men and women. Among men, there appears to be a slight downward trend in timing differences between the parental education groups, whereas among women, differences appear to be quite stable across cohorts. Generally, the higher the parental education, the later the start of the family formation process, but in the most recent cohort it was actually those with medium-educated parents whose median age of entering family formation was lowest. Among men, the relationship between parental education and timing of family formation is even completely reversed, as median age was highest among those with low-educated parents. Nevertheless, the overall picture in Sweden is that parental education bears little relation to family formation timing and that this has not changed across cohorts.

displays the predicted cumulative entry into family formation pathways for each birth cohort and parental education group in Sweden. In the 1925–44 cohort, the process of family formation differs little between parental education groups. Among all parental educational groups, the Marriage and parenthood pathway is clearly dominant.

In the 1945–64 cohort, a trend towards greater diversity is observed. The percentages following the Cohabitation and Cohabitation and parenthood pathways and, to a lesser extent, the Cohabitation dissolution pathway increase, resulting in fewer people following pathways that include marriage and childbearing. At the same time, some significant differences between parental education groups emerge. Young adults with low-educated parents are still most likely to follow the traditional Marriage and parenthood pathway. The Cohabitation and parenthood and Single parenthood pathways are also most common among young adults with low-educated parents. However, the Cohabitation dissolution pathway is found mainly among young adults with more highly educated parents. Having medium-educated parents is associated with a higher likelihood of following the Postponed marriage and parenthood pathway.

In the 1965–89 cohort, the general trends observed in the second cohort continue, with a decreasing percentage of young adults following pathways that include marriage and childbearing, and an increasing percentage following pathways that include cohabitation. Differences between the parental education groups remain largely similar to those found among the 1945–64 cohort.

France

When examining the results on median age of entry for France in , we find that timing differences in family formation between those with different parental education slightly increased in the 1945–64 cohort compared with the 1925–44 cohort, but that for the 1965–89 cohort the differences became smaller than in the 1925–44 cohort, indicating a general decline in differences in median age of entry between the parental education groups across cohorts. Among men, the differences even became almost zero in the 1965–89 cohort. However, similar to Sweden, the differences between those with low, medium, and high parental education were not large. Among both men and women, the maximum difference in median age at entry into family formation between those with low- and highly educated parents, observed in the 1945–64 cohort, was around two years. Contrary to Sweden, in France median age of entry into family formation was consistently higher among those with highly educated parents than those with low- and medium-educated parents.

displays the predicted cumulative entry into family formation pathways by birth cohort and parental education group for France. In the 1925–44 cohort, only a few differences between the parental educational groups are observed. Among all groups, Marriage and parenthood is the dominant pathway. The main difference is that young adults with a medium-educated parent are more likely to opt for Postponed marriage and parenthood. In line with the idea that young adults from more highly educated backgrounds are front runners in new family formation pathways, those with highly educated parents show a slightly stronger tendency to opt for the Cohabitation and parenthood pathway.

In the 1945–64 cohort, similar changes are observed among all parental education groups; the percentage entering the Marriage and parenthood pathway declines, while there are strong increases in all the other pathways except Single parenthood. Although Marriage and parenthood is still the most common option, the Postponed marriage and parenthood and Cohabitation pathways become increasingly popular. Yet, differences between parental education groups are now much more pronounced. Compared with young adults with low-educated parents, those with highly educated parents become less likely to opt for traditional pathways, such as Marriage and parenthood, Postponed marriage and parenthood, or Marriage, but more likely to enter the Cohabitation and Cohabitation dissolution pathways. Finally, young adults with medium-educated parents are less likely to enter the Single parenthood pathway than those with other educational backgrounds.

In the 1965–89 cohort, a continuation of the general trend is observed. Only a minority of young adults now opt for Marriage and parenthood by age 30, but at the same time no clear new dominant family formation pathway emerges. In particular, there is an increase in the percentage who enter the Cohabitation and Cohabitation and parenthood pathways. Nonetheless, differences between parental education groups remain. On one hand, the rates into pathways involving marriage are all higher for young adults with low-educated parents than for those with higher levels of parental education. On the other hand, having medium- or highly educated parents is associated with a higher rate of entry into the Cohabitation dissolution pathway and a lower rate of entry into the Cohabitation and parenthood pathway. Contrary to the previous birth cohort, all parental education groups are equally likely to enter the Cohabitation pathway. Thus, overall differences by parental education seem to decrease a little across cohorts, suggesting a slight process of convergence.

Italy

The results on differences in timing of family formation between parental education groups in Italy can be found in . These results show divergence between parental education groups in median age at entry into family formation across cohorts for both men and women. The maximum age difference in median entry into family formation between the parental education groups was 1.6 and 3.0 years for men and women, respectively, in the 1925–44 cohort, but increased to 4.0 and 5.9 years in the 1965–89 cohort. For both men and women, those with medium-educated parents show the least increase over time. As a result, among men in the 1965–89 cohort, the lowest median age of entering family formation is seen in those with medium-educated parents. There is a sex component, as for men it was mainly those with highly educated parents that diverged in terms of their median entry age from those with medium- and low-educated parents, with the former showing a lower median age of entry into family formation than the latter in the most recent cohort. However, for women it was simply that the more highly educated an individual’s parents were, the higher the individual’s median age of entering family formation. In addition, these socio-economic background differences increased across cohorts.

displays the predicted cumulative incidence of family formation pathways by birth cohort and parental education group for Italy. The Marriage and parenthood pathway is the dominant one in the 1925–44 cohort, and hardly anyone opts for a pathway that does not include marriage. Differences between the parental education groups are small, with two exceptions. Individuals with medium-educated parents are least likely to enter the Marriage and parenthood pathway, whereas those with low-educated parents enter this pathway fastest and those with highly educated parents catch up to some extent. Finally, although few young adults follow the Cohabitation pathway, those with medium-educated parents are more likely to do so than others.

In the 1945–64 cohort, the relative frequency of the Marriage and parenthood pathway decreases, with people more likely to opt for the Marriage or Postponed marriage and parenthood pathways than in earlier cohorts. Pathways that do not include marriage remain uncommon. The differences between those with low-educated parents and the others become more pronounced. As in the 1925–44 cohort, young adults with low-educated parents are more likely to enter a traditional pathway. On the other hand, those with medium- and highly educated parents are more likely to enter the Postponed marriage and parenthood, Cohabitation dissolution, and Cohabitation pathways. These results are in line with the SDT theory in that those with more highly educated parents are more likely to initiate new forms of family formation behaviour.

In the 1965–89 cohort, the graphs show a general postponement of entering all family pathways, whereas the relative likelihoods of entering each of the different pathways are quite similar to those for the 1945–64 cohort. Young adults with medium- and highly educated parents in particular show a lower entry into the Marriage and parenthood pathway. They are also less likely to follow the Marriage pathway than those with low-educated parents. However, Italy remains, across all birth cohorts, a country in which family pathways that include marriage are dominant across all social groups.

Romania

From we can assess the differences between parental education groups in median age of entry into family formation for Romania. Similar to Italy, these results show increasing differences between parental education groups in median age at entry into family formation across cohorts, for both men and women. In the 1925–44 and 1945–64 cohorts, the age difference in median age at entry into family formation between different parental educational levels was 1.6 and 2.0 years for men and women, respectively, in the 1925–44 cohort, but this increased to 3.0 and 5.2 years in the 1965–89 cohort. The divergence was stronger for women, whereas for men the divergence only became substantial in the 1965–89 cohort. Median age was consistently lowest among those with low-educated parents, and was even under 20 among women in the 1945–64 and 1965–89 cohorts with low-educated parents.

displays the predicted cumulative incidence of family formation pathways by birth cohort and parental education group in Romania. In the 1925–44 cohort, hardly anyone follows a family formation pathway that does not include marriage. Differences between parental education groups are small, with only two exceptions. Higher levels of parental education appear to be associated with a higher entry rate into the Marriage pathway. In addition, those with highly educated parents tend occasionally to enter the Cohabitation dissolution pathway, whereas those with low- or medium-educated parents do not.

In the 1945–64 cohort, the general picture remains roughly the same. The rates of entry into the Marriage and parenthood pathway increase slightly, but less so for those with highly educated parents, leading to a significant difference between parental education groups in entry into this pathway. At the same time, those with highly or medium-educated parents are more likely to follow the Marriage pathway. Furthermore, having highly educated parents increases the chance of entering the Cohabitation dissolution pathway, although in absolute terms very few do so.

Results from the 1965–89 cohort show even more strongly that individuals with highly educated parents in particular refrain from entering the Marriage and parenthood pathway. What is also noticeable is that the entry rates into Single parenthood and Cohabitation and parenthood are also higher for those with low-educated parents than for those with parents with higher levels of education.

Country comparison

The separate country analyses presented in the previous subsection suggest both similarities and differences across countries in the way parental education influences family formation patterns among young adults. Here, we synthesize these similarities and differences into three key points. First, children with highly educated parents enter the process of family formation at older ages than children with low-educated parents in all four countries. However, across cohorts, the age difference between both groups becomes slightly smaller in Sweden and France, but clearly increases in Italy and Romania. Second, differences in family formation pathways between young adults with low-, medium-, and highly educated parents increase across cohorts in all four countries, although mainly when comparing the earliest (1925–44) with the middle (1945–64) and most recent (1965–89) birth cohorts. Third, the type of socio-economic background divergence in family formation pathways that is witnessed differs between Italy and Romania on the one hand and France and Sweden on the other. In Italy and Romania unmarried cohabitation remains a marginal phenomenon for all three birth cohorts, and differences between young adults with low- and highly educated parents increase mainly because those with highly educated parents increasingly postpone all pathways that include parenthood during the first six years after the start of family formation. In Sweden and France, differences between young adults with low- and highly educated parents across cohorts increase partly for the same reason, but also because those with highly educated parents are increasingly more likely to enter cohabitation pathways and less likely to enter the Single parenthood pathway. Thus, in Italy and Romania we observe divergence because young adults with highly educated parents are increasingly more likely to postpone entry into family formation. In France and Sweden, we observe divergence not because young adults with highly educated parents are more likely to postpone entry into family formation, but because they are more likely to postpone marriage and parenthood and opt for unmarried cohabitation as an alternative.

Discussion

In this paper, we investigated the role of social origin in the family formation process over time and space. While there has been ample research showing a clear diversification of the family formation landscape across cohorts in European countries (Elzinga and Liefbroer Citation2007; Van Winkle Citation2018), little attention has been paid to the question of to what extent family background continues to shape differences in these family pathways. Our main finding is that differentials in family formation in terms of social origin remain strong and, arguably, have increased.

An innovation of this study was the separate examination of the timing of the start of family formation and the subsequent family formation pathway. In terms of timing, we found that those with low parental education entered family formation earlier than those with medium-or highly educated parents. Across cohorts, differences between parental educational groups became larger in Italy and, to a lesser extent, in Romania, whereas for France and Sweden differences remained rather small. In the most recent Swedish birth cohort, those with medium-educated parents even entered family formation the fastest. Perhaps in Sweden, those with low-educated parents have increasingly become a selective group with lower desirability on the marriage market, which delays their entry into family formation.

Regarding differences between parental education groups in the subsequent family formation pathways, we observed one common trend across all countries: young adults with highly educated parents have become increasingly less likely to follow what used to be the most traditional family trajectory, that is, marriage quickly succeeded by childbirth. Although young adults from low parental education backgrounds have also become less likely to opt for these kinds of pathways, they are still more likely to do so than those from high parental education backgrounds. The family pathways of young adults with medium-educated parents were generally slightly more similar to those of young adults with highly educated parents than to those with low-educated parents. Another trend is that those with low-educated parents were more likely to enter cohabitation and parenthood or single parenthood than those with medium- or highly educated parents. However, we hardly observed this trend in Italy. It appears that in Italy young adults with high socio-economic backgrounds postpone family formation altogether rather than choosing postponement of marriage and childbearing after starting the family formation process.

Overall, these results indicate that young adults from high socio-economic backgrounds are increasingly opting for a slower family formation process, either by spending longer in cohabitation and marriage before moving on to parenthood or by postponing family formation altogether, whereas young adults from low socio-economic backgrounds are still more likely to enter marriage and parenthood at a high rate, but at the same time are also more likely to follow pathways that include single parenthood or childbearing within cohabitation. Thus, in terms of the family pathways followed, there is clear divergence between individuals from low and high socio-economic backgrounds across birth cohorts in all four countries. However, the specific type of divergence varies across countries. In Italy and Romania, divergence occurs because young adults with highly educated parents are increasingly more likely to postpone entry into family formation. In France and Sweden, divergence occurs because young adults with more highly educated parents are more likely to postpone marriage and parenthood and to opt for cohabitation. In line with the “Diverging Destinies” literature (McLanahan Citation2004; McLanahan and Percheski Citation2008; Amato et al. Citation2015), our study suggests that the impact of socio-economic background on family formation patterns is increasing rather than stabilizing or declining (Wiik Citation2009; Brons et al. Citation2017; Koops et al. Citation2017).

The general changes in family formation across cohorts, and the differences in this process between France and Sweden on the one hand and Italy and Romania on the other, are in line with expectations from SDT theory. However, the SDT does not stress the persistent impact of family background. We found that socio-economic background differences do not become smaller across cohorts; on the contrary, they increase. This is where the PoD theory can complement the SDT theory. The PoD theory focuses on socio-economic differences, but cannot explain changes in patterns that occur across all social strata. The cultural changes that drove the SDT have facilitated routes to disadvantageous family patterns, including forms of non-marital childbearing that would previously not have been socially accepted or would have been prevented by institutions, such as the church. Before the SDT, more uniformity existed in the family formation pathways of young adults from all socio-economic backgrounds, as almost everyone entered family formation by marrying and subsequently having children. Hence, we can argue that the cultural processes behind the SDT created more room for diversity on the basis of socio-economic background. The less effective social norms are in forcing people towards one particular family formation pathway, the larger any social inequalities in terms of family formation pathway patterns will become.

This study is not without limitations. First, we used a single indicator of socio-economic background, highest parental education. It would be worthwhile to examine the impact of other indicators of socio-economic background, such as parental occupational status, parental household income, and parental assets. Furthermore, the meaning of parental education may have changed. Whereas in the past the educational level of the father might have mattered most, nowadays the mother’s might matter more or both might be equally important. Future research could try to disentangle the impact of both the father’s and the mother’s education. Second, although we selected four quite distinct European countries, these may be too specific to generalize the results to the whole of Europe. Therefore, it will be important in future research to investigate in more detail how country and regional differences impact the relationship between socio-economic background and family formation.

Although the influence of parents may have declined since the time when the majority of parents arranged marriages for their children (Cherlin Citation2012), this study has demonstrated that in a subtler form the impact of parents on their children’s family formation is still salient. It is worth noting that the results from studies investigating the role of own education on family formation show similar results. For instance, Mikolai et al. (Citation2018) found that childbearing within cohabitation is more common among the lower educated, which is in line with our finding that the risk of childbearing outside marriage is higher among those with lower-educated parents. This suggests that the intergenerational transmission of education is an important explanation as to why differences in family formation patterns arise between individuals with different levels of education. However, it would be useful for future research to examine to what extent the influence of socio-economic background is mediated through own educational attainment and perhaps how these relationships have changed over time (Brons et al. Citation2017).

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (173.3 KB)Notes

1 Jarl E. Mooyaart is based at the Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute, the Hague, affiliated with the University of Groningen. Aart C. Liefbroer is based at the Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute, the Hague; the Department of Epidemiology at University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG) and the University of Groningen; and the Department of Sociology, VU University Amsterdam, all in the Netherlands. Francesco C. Billari is based in the Department of Social and Political Sciences and the Carlo F. Dondena Centre for Research on Social Dynamics and Public Policies, Bocconi University, Milan, Italy.

2 Please address all correspondence to Jarl E. Mooyaart, Postbus 11650, 2502 AR Den Haag; or by Email: [email protected]

3 Funding information: European Commission Seventh Framework Programme (FP7), Ideas programme, European Research Council [grant number 324178].

References

- Abbott, Andrew, and Angela Tsay. 2000. Sequence analysis and optimal matching methods in sociology: Review and prospect, Sociological Methods & Research 29(1): 3–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124100029001001

- Amato, Paul R., Alan Booth, Susan M. McHale, and Jennifer Van Hook (eds). 2015. Families in an Era of Increasing Inequality, Vol. 5. National Symposium on Family Issues. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08308-7

- Apostu, Iulian. 2013. The traditionalism of the modern family–social and legal direction and contradiction, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 92: 46–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.635

- Billari, Francesco C. 2001. Sequence analysis in demographic research, Canadian Studies in Population 28(2): 439–458. doi:https://doi.org/10.25336/P6G30C

- Billari, Francesco C., and Aart C. Liefbroer. 2010. Towards a new pattern of transition to adulthood? Advances in Life Course Research 15(2–3): 59–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2010.10.003

- Billari, Francesco C., Nicole Hiekel, and Aart C. Liefbroer. 2019. The social stratification of choice in the transition to adulthood, European Sociological Review 35(5): 599–615. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcz025

- Blau, Peter M., and Otis D. Duncan. 1967. The American occupational structure. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Blossfeld, Hans-Peter, and Johannes Huinink, 1991. Human capital investments or norms of role transition? How women's schooling and career affect the process of family formation, American Journal of Sociology 97(1): 143–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/229743

- Bradley, D. 2001. Regulation of unmarried cohabitation in west-European jurisdictions - determinants of legal policy, International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/lawfam/15.1.22

- Brons, M. D. A., Aart C. Liefbroer, and Harry B. G. Ganzeboom. 2017. Parental socio-economic status and first union formation: Can European variation be explained by the Second Demographic Transition theory? European Sociological Review 33(6): 809–822. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx078

- Brons, Anne M.D., and Jarl E. Mooyaart. 2018. The generations & gender programme: Constructing harmonized, continuous socio-economic variables for the GGS Wave 1. Working paper available at: https://pure.knaw.nl/portal/nl/publications/the-generations-amp-gender-programme-constructing-harmonized-cont

- Brückner, Hannah, and Karl Ulrich Mayer. 2004. De-standardization of the life course: What it might mean? And if it means anything, whether it actually took place? Advances in Life Course Research. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-2608(04)09002-1

- Buchmann, Marlis C., and Irene Kriesi. 2011. Transition to adulthood in Europe, Annual Review of Sociology 37(1): 481–503. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150212

- Cherlin, Andrew J. 2012. Goode’s world revolution and family patterns: A reconsideration at fifty years, Population and Development Review. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00528.x

- Coleman, David. 2003. Why we don’t have to believe without doubting in the “Second Demographic Transition” — some agnostic comments, Vienna Yearbook of Population Research 2(2004): 11–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1553/populationyearbook2004s11.

- Elzinga, Cees H., and Aart C. Liefbroer. 2007. De-standardization of family-life trajectories of young adults: A cross-national comparison using sequence analysis, European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie 23(3–4): 225–250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-007-9133-7

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 1990. The three worlds of welfare capitalism, in The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, pp. 1–34. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2073705

- Fodor, Eva, Christy Glass, Janette Kawachi, and Livia Popescu. 2002. Family policies and gender in Hungary, Poland, and Romania, Communist and Post-Communist Studies. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-067X(02)00030-2

- Frejka, Thomas. 2008. Overview chapter 5: Determinants of family formation and childbearing during the societal transition in Central and Eastern Europe, Demographic Research. doi:https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.7

- Gabadinho, Alexis, Gilbert Ritschard, Nicolas Séverin Mueller, and Matthias Studer. 2011. Analyzing and visualizing state sequences in R with TraMineR, Journal of Statistical Software 40(4): 1–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v040.i04

- Gray, Robert J. 1988. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk, The Annals of Statistics 16(3): 1141–1154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176350951

- Haas, Linda. 1996. Family policy in Sweden, Journal of Family and Economic Issues. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02265031

- Hoem, Jan M. 1986. The impact of education on modern family-union initiation, European Journal of Population. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01796886

- Hoem, Jan M., Dora Kostova, Aiva Jasilioniene, and Cornelia Mureşan. 2009. Traces of the second demographic transition in four selected countries in central and Eastern Europe: Union formation as a demographic manifestation, European Journal of Population / Revue Européenne de Démographie 25(3): 239–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-009-9177-y

- Koops, Judith C., Aart C. Liefbroer, and Anne H. Gauthier. 2017. The influence of parental educational attainment on the partnership context at first birth in 16 Western societies, European Journal of Population 33(4): 533–557. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-017-9421-9

- Lesnard, Laurent, Anne-Sophie Cousteaux, Flora Chanvril, and Viviane Le Hay. 2016. Do transitions to adulthood converge in Europe? An optimal matching analysis of work–family trajectories of men and women from 20 European countries, European Sociological Review 32(3): 355–369. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcw003

- Lesthaeghe, Ron. 2010. The unfolding story of the Second Demographic Transition, Population and Development Review 36(2): 211–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00328.x

- Lesthaeghe, Ron. 2014. The second demographic transition: A concise overview of its development: Table 1, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(51): 18112–18115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1420441111

- Lesthaeghe, Ron and van de Kaa, Dirk, 1986. Twee demografische transities? [Two demographic transitions?], in R. Lesthaeghe and D. van de Kaa (eds), Bevolking: groei en krimp [Population, growth & decline], pp. 9–24. Deventer: Mens enMaatschappij, 1986 book supplement, Van Loghum Slaterus.

- Lyngstad, Torkild Hovde. 2006. Why do couples with highly educated parents have higher divorce rates? European Sociological Review 22(1): 49–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jci041

- Martin, Claude. 2010. The reframing of family policies in France: Processes and actors, Journal of European Social Policy. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928710380479

- Mayer, Karl Ulrich Urlich. 2004. Whose lives? How history, societies, and institutions define and shape life courses, Research in Human Development 1(3): 161–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427617rhd0103_3

- McLanahan, Sara. 2004. Diverging destinies : How children are faring under the Second Demographic Transition*, Demography 41(4): 607–627. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2004.0033

- McLanahan, Sara, and Christine Percheski. 2008. Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities, Annual Review of Sociology 34(1): 257–276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134549

- Mikolai, Julia., Ann Berrington, and Brienna Perelli-Harris. 2018. The role of education in the intersection of partnership transitions and motherhood in Europe and the United States, Demographic Research 39: 753–794. doi:https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2018.39.27

- Miller, Brent C. 2002. Family influences on adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior, Journal of Sex Research 39(1): 22–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490209552115

- Mills, Melinda, and Hans-Peter Blossfeld. 2013. The second demographic transition meets globalization: A comprehensive theory to understand changes in family formation in an era of rising uncertainty, in Ann Evans, and Janeen Baxter (Eds.), Negotiating the Life Course. Stability and Change in Life Pathways, pp. 9–33. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8912-0_2

- Perelli-Harris, Brienna, and Nora Sánchez Gassen. 2012. How similar are cohabitation and marriage? Legal approaches to cohabitation across Western Europe, Population and Development Review. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00511.x

- Perelli-Harris, Brienna, and Theodore P. Gerber. 2011. Nonmarital childbearing in Russia: Second Demographic Transition or Pattern of Disadvantage? Demography 48(1): 317–342. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-010-0001-4

- Perelli-Harris, Brienna, and Mark Lyons-Amos. 2016. Partnership patterns in the United States and across Europe: The role of education and country context, Social Forces 95(1): 251–282. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sow054

- Perelli-Harris, Brienna, Michaela Kreyenfeld, and Karolin Kubisch. 2010a. Harmonized histories: Manual for the preparation of comparative fertility and union histories, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research Working Paper 11: 0–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.4054/MPIDR-WP-2010-011

- Perelli-Harris, Brienna, Wendy Sigle-Rushton, Michaela Kreyenfeld, Trude Lappegård, Renske Keizer, and Caroline Berghammer. 2010b. The educational gradient of childbearing within cohabitation in Europe, Population and Development Review 36(4): 775–801. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00357.x

- Perelli-Harris, Brienna, Michaela Kreyenfeld, Wendy Sigle-Rushton, Renske Keizer, Trude Lappegård, Aiva Jasilioniene, Caroline Berghammer, and Paola Di Giulio. 2012. Changes in union status during the transition to parenthood in eleven European countries, 1970s to early 2000s, Population Studies. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2012.673004

- Potârcă, Gina, Melinda Mills, and Laurent Lesnard. 2013. Family formation trajectories in Romania, the Russian Federation and France: Towards the Second Demographic Transition?, European Journal of Population / Revue Européenne de Démographie 29(1): 69–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-012-9279-9

- Rose, A. De, and D. Vignoli. 2011. Families all’italiana: 150 years of history, Rivista Italiana Di Demografia, Economia e Statistica 65(2): 121–144.

- Rose, Alessandra De, Filomena Racioppi, and Anna Laura Zanatta. 2008. Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour, Demographic Research. doi:https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.19

- Schröder, Heike, and Harry B.G. Ganzeboom. 2013. Measuring and modelling level of education in European societies, European Sociological Review 30(1): 119–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jct026

- Schwanitz, Katrin. 2017. The transition to adulthood and pathways out of the parental home: A cross-national analysis, Advances in Life Course Research 32: 21–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2017.03.001

- Scrucca, L., A. Santucci, and F. Aversa. 2010. Regression modeling of competing risk using R: An in depth guide for clinicians, Bone Marrow Transplantation. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2009.359

- Sironi, Maria, Nicola Barban, and Roberto Impicciatore. 2015. Parental social class and the transition to adulthood in Italy and the United States, Advances in Life Course Research 26: 89–104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2015.09.004

- Sobotka, Tomáš. 2008. Overview chapter 6: The diverse faces of the second demographic transition in Europe, Demographic Research. doi:https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.8

- Studer, Matthias. 2013. WeightedCluster Library Manual: A practical guide to creating typologies of trajectories in the social sciences with R (LIVES Working Papers, 24). doi:https://doi.org/10.12682/lives.2296-1658

- Studer, Matthias, and Gilbert Ritschard. 2016. What matters in differences between life trajectories: A comparative review of sequence dissimilarity measures, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 179(2): 481–511. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/rssa.12125

- Studer, Matthias, Aart C. Liefbroer, and Jarl E. Mooyaart. 2018. Understanding trends in family formation trajectories: An application of competing trajectories analysis (CTA), Advances in Life Course Research 36: 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2018.02.003

- Thornton, Arland, and Dimiter Philipov. 2009. Sweeping changes in marriage, cohabitation and childbearing in central and Eastern Europe: New insights from the developmental idealism framework, European Journal of Population. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-009-9181-2

- Van Winkle, Zachary. 2018. Family trajectories across time and space: Increasing complexity in family life courses in Europe? Demography 55(1): 135–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0628-5

- Vikat, Andres, Zsolt Spéder, Gijs Beets, Francesco C Billari, Christoph Bühler, Aline Désesquelles, Tineke Fokkema, Jan M Hoem, Alphonse MacDonald, and Gerda Neyer. 2007. Generations and Gender Survey (GGS): Towards a better understanding of relationships and processes in the life course, Demographic Research 17: 389–440. doi:https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2007.17.14

- Wiik, Kenneth Aarskaug. 2009. ‘You’d Better Wait!’- Socio-economic background and timing of first marriage versus first cohabitation, European Sociological Review 25(2): 139–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn045

- Winkler-Dworak, Maria, & Laurent Toulemon. 2007. Gender differences in the transition to adulthood in France: Is there convergence over the recent period?, European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie 23(3): 273–314. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27694366.

- Zaidi, Batool, and S. Philip Morgan. 2017. The Second Demographic Transition theory: A review and appraisal, Annual Review of Sociology 43(1): 473–492. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053442

- Zimmermann, Okka, and Dirk Konietzka. 2018. Social disparities in destandardization—Changing family life course patterns in seven European Countries, European Sociological Review 34(1): 64–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx083