Abstract

This paper argues that son preference resulted in gender-based discriminatory practices that unduly increased mortality rates for females at birth and throughout infancy and childhood in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Greece. The relative numbers of boys and girls at birth was extremely high and under-registration of females cannot on its own explain this result. The infanticide and/or mortal neglect of infant girls was therefore more common than previously acknowledged. Likewise, sex ratios increased as children grew older, thus suggesting that parents continued to treat boys and girls differently throughout childhood. A large body of qualitative evidence (contemporary accounts, folklore traditions, feminist newspapers, and anthropological studies) further supports the conclusion that girls were neglected due to their inferior status in society.

Introduction

Written by Alexandros Papadiamantis, one of the most influential Greek authors, The Murderess (Citation1903) provides a bleak picture of the fate of women in Greece. As servants of their fathers, husbands, children, and grandchildren, women suffered miserable lives toiling under harsh conditions and the prevailing patriarchal system. In this short story, Hadoula, the central female character, is impelled to murder a series of infant girls, including her newborn niece. Reflecting on the futility, emptiness, and hardness of her life, Hadoula realizes that there is nothing worse than being born a woman and this thought leads her to kill young girls, almost as a mercy to save them from a gloomy future. This idea is also quite explicit in her recurrent prayer for little girls: ‘May they not survive! May they go no further!’ (Papadiamantis Citation1983, p. 14).

Although Papadiamantis’ fiction may admittedly have exaggerated societal attitudes towards girls, it is surprising that previous research has hardly entertained the possibility that the infanticide and/or mortal neglect of girls was a defining feature of Modern Greece. While a number of studies have openly discussed the high sex ratios found in Greek historical statistics, their authors have not linked the lack of females to gender-based discriminatory practices resulting in excess mortality among females (Valaoras Citation1960; Asdrahas Citation1978; Panagiotopoulos Citation1987; Caftantzoglou Citation1997; Komis Citation1999; Kosmatou Citation2000). Moreover, these studies have focused mostly on adult men and women, rather than their experiences in infancy and childhood. Only a few scholars have tangentially called into question previous assumptions and suggested that the predominance of males was due to relatively higher mortality for females early in life (Siampos Citation1973, p. 57; Hionidou Citation1993, p. 51; Gavalas Citation2001, pp. 232–4; Komis Citation2004, p. 290). However, distorted sex ratios at birth, in infancy, and in childhood, as well as anecdotal evidence on discriminatory practices, do indeed indicate that this issue merits further attention.

This paper shows that the relative numbers of boys and girls found in the published Greek birth statistics and population censuses showed extreme imbalances during the second half of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century. Sex ratios were not only extremely high at birth and in infancy, but increased as children got older, thus suggesting that gender discrimination continued throughout childhood. Greek families prioritized boys’ well-being and, in a context characterized by widespread poverty and high mortality, discrimination in terms of food, childcare, and/or workload impaired girls’ net nutritional status and increased mortality for females due to the combined effect of malnutrition and diseases. Taken together, the estimations reported here imply that a significant fraction of girls went ‘missing’ due to discriminatory practices between 1861 and 1920 (ranging from 4.6 to 10.4 per cent depending on the particular census year). Crucially, the analysis also provides evidence that under-registration of females cannot on its own explain these distorted figures, especially considering that the child sex ratios found in Greek migrant families in the United States (US) were also very high. In addition, a large body of qualitative evidence (ranging from contemporary accounts, folklore traditions, and feminist newspapers to anthropological studies) supports the argument that some sort of gender discrimination was unduly increasing mortality for females early in life.

Although a vast body of research has explored the ‘missing girls’ phenomenon in contemporary less developed countries, especially in South and East Asia and in Africa (e.g. Sen Citation1990; Das Gupta et al. Citation2003; Anderson and Ray Citation2010; Drixler and Kok Citation2016; Das Gupta Citation2017; Iqbal et al. Citation2018), the historical European experience has received very little attention. If anything, the prevailing argument is that religious beliefs and the household formation system limited the infanticide and mortal neglect of young girls (Derosas and Tsuya Citation2010; Lynch Citation2011). This paper challenges the idea that there were no missing girls in historical Europe and thus builds on recent research showing that this phenomenon was likely much more widespread than previously thought, especially in Southern and Eastern Europe (Hanlon Citation2016; Beltrán Tapia and Gallego-Martínez Citation2017; Beltrán Tapia Citation2019; Beltrán Tapia and Marco-Gracia Citation2020; Marco-Gracia and Beltrán Tapia Citation2020; Beltrán Tapia et al. Citation2021). A related strand of the literature has also suggested that an unequal allocation of resources within households negatively affected girls’ heights and mortality in nineteenth-century Britain and continental Europe (Tabutin Citation1978; Johansson Citation1984; Pinnelli and Mancini Citation1997; Tabutin and Willems Citation1998; Baten and Murray Citation2000; McNay et al. Citation2005; Horrell and Oxley Citation2016; Manfredini et al. Citation2016, Citation2017).

This paper also contributes to the literature discussing the underlying factors behind gender discrimination. The position of women within the household and society in general is influenced by cultural values that tend to respond to the incentives created by the economic and environmental context (Das Gupta et al. Citation2003; also Giuliano Citation2017). It has been argued, for instance, that the historical division of labour arising from pastoralism or the use of the plough helped to shape gender inequality (Alesina et al. Citation2013; Becker Citation2019). Likewise, having access to employment opportunities and urban areas tends to strengthen the position of women (Qian Citation2008; Beneito and García-Gómez Citation2019; Evans Citation2019; Van Zanden et al. Citation2019; Xue Citation2020). The kinship and dowry systems can also play a crucial role in motivating son preference (Mattison et al. Citation2016; Bhalotra et al. Citation2020). The status of Greek girls, living within a rural, poor, and patriarchal society, was negatively shaped by patrilineality and the obligation that the dowry imposed on families (Blum and Blum Citation1965; Stott Citation1973). Moreover, as Modern Greek history was riddled with conflict, the fear of war (and of blood feuds) may also have contributed to a strong son preference due to the perception that males were defenders, while females were liabilities because they needed to be defended (Mavisakalyan and Minasyan Citation2018; Sng and Zhong Citation2018), a feature that was reinforced by the concept of honour that is characteristic of Greek and other Mediterranean cultures (Peristiany Citation1965). The lack of potential male partners due to mass migration in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries further worsened women’s position in the marriage market. Given that remaining single was not socially accepted, the rising costs of dowries made having girls a heavier burden for their families. However, the skewed sex ratios and the qualitative evidence pointing to neglect of females began to disappear from the 1920s onwards. Studying the Greek case is therefore crucial to shedding light on the complex relationship between gender discrimination and changing economic, social, and cultural circumstances.

Gender roles, dowries, and attitudes towards girls in Greece

At least until the 1960s, women’s agency in rural Greece was rather limited, and was restricted to rigid gender roles (Friedl Citation1967; Stott Citation1973; Hionidou Citation1995; Thanailaki Citation2018). In the nineteenth century, women were socially defined by their natural attributes as wives and mothers, confined to the private sphere, and regarded as second-class citizens (Avdela Citation2005, p. 117; Tzanake Citation2009, p. 128; Varikas Citation2011, p. 62). The hierarchical status of the traditional patriarchal Greek family assigned sons a higher status than their older sisters or even their mothers (Valmas Citation1936). Naming practices also reflected this hierarchy: the surname was written in the nominative case for boys and in the genitive case for girls, thus implying that females were ‘of’ a particular family while males ‘were’ the family (Danforth Citation1982, p. 137; Stewart Citation2016, p. 56). In addition, most families were prejudiced against schooling for females, so most girls remained illiterate (Tsoukalas Citation1987, p. 413; Varikas Citation2011, p. 77; Thanailaki Citation2018, p. 13).

Moreover, girls were not allowed to choose their future husbands, and marriages were usually arranged by their parents. As remaining unmarried was not socially accepted and resulted in marginalization for women, girls had no choice but to accept the arranged marriage (Lambiri-Dimaki Citation1972, p. 75). Although age differences between spouses declined over time, a significant gap was still visible in the early twentieth century (Bafounis Citation1984, p. 217; Hionidou Citation1993, p. 54; Gavalas Citation2008, p. 516). The new bride often lived with her in-laws, but this practice varied by region (Couroucli Citation1987; Hionidou Citation2011, Citation2016). A woman’s moral reputation was extremely important, so rigid codes regulated women’s behaviour in order to safeguard their honour. They were not supposed to go to wine shops, cafés, or taverns, and they could not visit friends alone (Garnett Citation1914, pp. 193–7; Stott Citation1973, p. 127). Women bearing ‘illegitimate’ children were forced to leave the village because having children outside marriage was considered a disgrace (Thanailaki Citation2018, p. 94). Strict customs also regulated widowhood, and remarriage was not generally accepted. Although the status of women improved over subsequent decades, many of these practices were still visible in rural areas up to the 1970s (Friedl Citation1964, p. 12; Blum and Blum Citation1965). According to Du Boulay (Citation1984), men’s dominance was so prevalent in Greece that women had not only accepted it, but also internalized it. Greek women were thus supposed to endure all hardships, including domestic violence, without complaining (Blum and Blum Citation1965, pp. 48–50; Dimen Citation1986; Thanailaki Citation2018, p. 111).

Son preference was therefore an important feature of Greek society. At wedding receptions, for instance, it was customary to wish the bride the good fortune of bearing seven sons and one daughter (Lawson Citation1910, p. 21). Another ritual at these celebrations involved rolling a male child over the newly-weds’ bed several times in order to symbolically wish that the couple will have a male firstborn (Argyrou Citation1996, p. 64). Indeed, while the birth of a son was greeted with expressions of joy, the birth of a daughter was often seen as a cause for blame and lamentation (Du Boulay Citation1983, p. 244; Paradelles Citation1995, pp. 88–9; Thanailaki Citation2018, pp. 57, 100, 130). The folklore traditions of symbolically pleading to have a male baby while showing contempt for female ones were widespread throughout Greece. A tradition of the Mani region was particularly extreme: while a newborn boy would be placed in a sieve to symbolize the hope that the mother will give birth to as many boys as the holes of the sieve, a baby girl would be put into a washtub, a symbolic grave that represented the wish to avoid giving birth to another girl in the future (Paradelles Citation1995, p. 96). Males were considered more useful for the family economy, especially in rural areas, regardless of whether their labour contribution was actually larger than that of females (Friedl Citation1964; Campbell Citation1964). In addition, sons were supposed to support their single sisters and parents, in particular to support their mothers through widowhood (Hionidou Citation2011, pp. 220–1, 231). While patrilocal and patrilineal traditions also contributed to the subordinate position of rural Greek women (Danforth Citation1982, p. 136; Gallant Citation1991, p. 493), these practices were not uniformly spread across Greece (Kasdagli Citation2004, p. 268).

Likewise, the dowry system made girls a burden to their families since they drained the family resources (Parren Citation1888, pp. 1–2; Rodd Citation1892, p. 92; see also Parren Citation1887b; Stott Citation1973, pp. 126–7; Du Boulay Citation1983; Alexakis Citation1984; Couroucli Citation1987; Caftantzoglou Citation1994; Franghiadis Citation1998; Petmezas and Papataxiarchis Citation1998; Kasdagli Citation2005; Hionidou Citation2011; Varikas Citation2011; Michaleas and Sergentanis Citation2019). As well as furniture, clothes, homeware, or cash, dowries could consist of livestock, one or more pieces of land, and/or a house, depending on the parents’ wealth (regional differences, however, affected the type of dowry that girls received). Although direct evidence of the value of such dowries is limited, dowries generally represented a significant fraction of the familial wealth and probably approximated the corresponding share were the family property to be divided equally among all the children (Hionidou Citation1999, p. 418).

Moreover, ensuring that their daughters married was a primary obligation for families, and whether families succeeded in doing so depended on how generous the dowries were. Higher endowments were paid if the marriage was a step up the social ladder (Michaleas and Sergentanis Citation2019). The exact amount was often subject to bargaining, and marriages were often seen as commercial transactions in which brides were judged primarily on the basis of the size of their dowries (Ferriman Citation1910, p. 141; Sanders Citation1962, p. 166; Lambiri-Dimaki Citation1972, p. 75; see also Miller Citation1905, pp. 92–3; Garnett Citation1914, p. 197). The lack of a dowry usually meant that the daughter was condemned to end up a spinster (Stott Citation1973, pp. 126–7). In the absence of the father, male children were traditionally obliged to remain single in order to contribute to their sisters’ dowries until they were all married (Franghiadis Citation1998, p. 189).

Providing daughters with enough resources to secure a good marriage thus imposed a heavy burden on parents, an obligation that was especially onerous for poor families with many daughters (Stott Citation1973, pp. 126–7; Varikas Citation2011, pp. 183, 297). According to Blum and Blum (Citation1965, p. 48), the anticipation of the dowry problem is one reason why female infants were not welcomed. The shortage of men due to mass migration (or in contexts where sailors were away from home for long periods) made boys even more valuable and contributed to dowry inflation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Psychogios Citation1987, pp. 174–80; Sant Cassia and Bada Citation1992, p. 192; Kasdagli Citation2005, p. 9). For instance, in Thebes, dowries were around 300–400 drachmas before mass-scale migration, but had risen sharply to 5,000–10,000 drachmas by the 1920s (Tourgeli Citation2020, p. 147). Not only were many of these dowries paid with loans (Surridge Citation1930), but securing a dowry for their sisters was also another reason why young males were migrating to the US at such high rates in the early twentieth century (Fairchild Citation1911, p. 39; Xenides Citation1922, p. 91; Saloutos Citation1964, p. 31). The problem of the lack of men was indeed so acute that the Greek Parliament considered intervening by creating a special tax for unmarried males in both 1887 and 1928, although the tax was ultimately not approved (Sant Cassia and Bada Citation1992, p. 192).

Lastly, other historical and cultural factors may also have shaped the position of women and girls in Modern Greece. The long struggle for emancipation from the Ottoman Empire led to a very violent period plagued by war and conflict. As well as major conflicts, such as the War of Independence (1821–29), the Greco–Turkish War (1897), and the Balkan Wars (1912–13), a series of rebellions, uprisings, and invasions meant that violence was a constant presence in this society (Gallant Citation2015, pp. 187, 327–8). Blood feuds were also common, especially in certain regions (Campbell Citation1970; Herzfeld Citation1985; Gallant Citation2015, pp. 205–8). The fear of conflict may therefore have altered how Greek families perceived the relative values of boys and girls (Mavisakalyan and Minasyan Citation2018; Sng and Zhong Citation2018). While males were seen as useful defenders, females were considered liabilities based on the perception that they needed to be protected. In addition, these notions about women were probably accentuated by the Mediterranean honour culture (Peristiany Citation1965). The belief that girls were a liability also stemmed from the idea that they needed to be protected because the family could be dishonoured through their behaviour, so girls were a constant source of worry (Blum and Blum Citation1965, pp. 50, 75; Du Boulay Citation1974, p. 124).

Given the perceived value of women and the resulting attitudes towards girls observed in Modern Greece, it is plausible that families engaged in the infanticide and mortal neglect of young girls. Relying on the analysis of sex ratios at different ages and qualitative evidence from contemporary accounts, folklore traditions, feminist newspapers, and anthropological studies, the next two sections provide evidence that the infanticide and/or mortal neglect of young girls was much more prevalent in Greece than has been previously recognized, at least during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Sex ratios at birth and during childhood in Greece

Analysing the relative numbers of boys and girls observed in published birth statistics and population censuses provides crucial hints about the prevalence of discriminatory practices that unduly increased mortality among females (Sen Citation1990; Das Gupta et al. Citation2003; Klasen and Wink Citation2003; Jayachandran Citation2015; Guilmoto Citation2018).

Sex ratios at birth

In the absence of differential treatment, the sex ratio at birth is remarkably regular: in most developed countries today, it revolves around 105–106 boys per 100 girls (Hesketh and Xing Citation2006; World Bank Citation2011). Compared with this benchmark, the relative number of male births reported in Greece was extremely high during the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century. We should nonetheless be cautious about the reliability of these early demographic reports. The Ministry of Interior did not start to collect the number of births systematically until 1861. However, this information was collected yearly only until 1873. Between 1874 and 1920, birth statistics were made available only for the year 1884. Data collection resumed in 1921 and published annual statistics are available for the 1921–38 period. The Second World War and the political and economic crises that followed, which resulted in the Greek Civil War, also prevented the gathering of this information between 1940 and 1949 (NSSG Citation1956, pp. XII–IV). Although these statistics probably underestimated the number of births up to the 1920s (Valaoras Citation1988), this under-enumeration was not sex-specific, at least in Mykonos (Hionidou Citation1993, p. 123; 1997, p. 158). In this regard, Stéphanos (Citation1884, p. 455) noticed the disproportionate number of males in the statistics but argued that there was no reason for families to have under-registered female births.

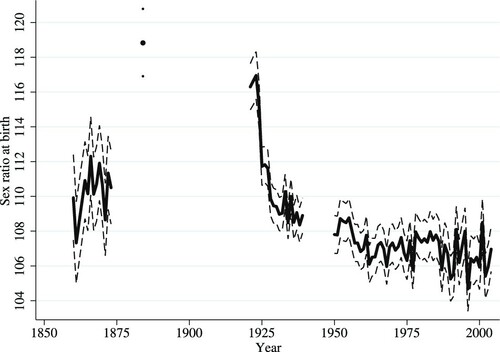

plots Greek sex ratios at birth between 1861 and 2004. For the period between 1861 and 1873, when this information was available without interruptions, the average ratio was 110.4 boys per 100 girls (with the 95 per cent confidence interval for that period being 109.8–111.1). By 1884, the sex ratio at birth had further increased to 118.8. Similar high figures are observed when the information became available again in the early 1920s: the average sex ratio at birth was 116.3 boys per 100 girls between 1921 and 1924. Significantly lower figures are, however, clearly visible in 1925–27 (when the average was 111.7) and the declining trend continued during the next decade (by 1939, the sex ratio at birth had decreased to 108.9). Although sex ratios in the early 1950s were still slightly elevated, the figures observed from then onwards did not diverge fundamentally from those found in similar contexts; the sex ratio at birth fluctuated between 106 and 108 (see also Tragaki and Lasaridi Citation2009). Interestingly, recent research has found strong evidence of sex-selective abortions among illiterate Greek mothers between 2004 and 2011 (Gavalas et al. Citation2015), thus indicating that son preference has not completely disappeared in certain contexts.

Figure 1 Sex ratios at birth in Greece, 1861–2004

Notes: The dashed lines reflect the corresponding confidence intervals at the 95 per cent level. See ‘Sex ratios at birth’ subsection for information on missing data.

Source: Statistics of the Movement of the Population; Monthly Statistical Bulletin of Greece.

These high sex ratios at birth, especially those pre-1930, were noted by the Greek statistical authorities (see, for instance, the comments by Soutsos in Population Movement During the Year 1860 [Ministry of Interior Citation1862, p. 6]). A detailed statistical description provided by the Bavarian consul in Athens also included similarly extreme figures in 1839: 111.8 for the whole country and even higher (114.3) for the regions in mainland Greece (Strong Citation1842, pp. 46–7). There was also an exceptional imbalance in the relative numbers of male and female births on the Ionian island of Lefkada between 1823 and 1863 (Ministry of Interior Citation1866; Tomara-Sideri and Sideris Citation1986, pp. 30–2). Even accepting that girls could have been under-registered to some degree, the sex ratios at birth found in Greece during the nineteenth century and the 1920s are simply too high and suggest the presence of infanticide and/or mortal neglect of infant girls. As we will see in the next subsection, the analysis of infant and child sex ratios shows that the reported sex ratios at birth were probably an accurate reflection of those infants who survived to be registered as live births.

Child sex ratios from population censuses

This subsection relies on sex ratios computed from the population counts in order to: (1) test further the accuracy of sex ratios at birth reported in the vital statistics; and (2) assess whether excess mortality among females continued during infancy and childhood.

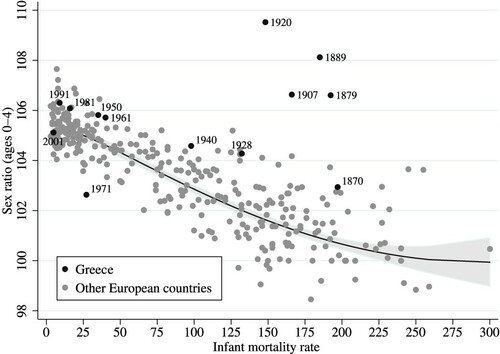

Before considering the relative numbers of boys and girls in the Greek censuses, it is important to note that child sex ratios in the past are not comparable to contemporary ones because mortality levels during infancy and childhood have a direct influence on sex ratios in these age groups. Due to the survival advantage of females, harsher environments are especially deleterious to boys (especially during the first years of life), thus increasing their relative mortality and resulting in lower sex ratios. Following the estimation in Beltrán Tapia (Citation2019, pp. 5–6), plots the available information on infant mortality and child sex ratios (ages 0–4) in European countries between 1750 and 2001 and illustrates the negative relationship between these two variables. According to these estimates, infant mortality of slightly below 200 deaths per 1,000 live births (in line with the values reported for Greece during the second half of the nineteenth century [Valaoras Citation1960, p. 132]), should yield child sex ratios of around 101 boys per 100 girls.

Figure 2 Child sex ratios (ages 0–4) and infant mortality in Greece and Europe, 1750–2001

Notes: The Kingdom of Greece underwent significant changes during the period depicted here. It incorporated the Ionian Islands in 1864, Thessaly and Arta in 1881, Epirus, Macedonia, Crete, and the North Aegean Islands in 1913, Thrace in 1920, and the Dodecanese Islands in 1947. The events of 1922–23 also led to significant changes in the Greek population.

Source: Beltrán Tapia (Citation2019). Based on Mitchell (Citation2013), Valaoras (Citation1960, p. 132), and the respective Greek population censuses.

Compared with this benchmark, the child sex ratios (for ages 0–4) reported in the Greek censuses were much higher than they should have been (see black circles in ), at least between 1879 and 1920, when this ratio ranged between 106.7 and 109.5. The figures were indeed much higher than those of most European countries during that period (see Figure A1 in the supplementary material; the relative numbers of boys and girls, together with the corresponding confidence intervals, for the 1861–2001 period are provided in Table A1, supplementary material). It is important to stress that, due to the biological advantage of females, sex ratios at birth should be higher than child sex ratios because more boys die naturally at birth and during infancy and childhood, especially in high-mortality environments. The relatively high number of boys aged 0–4 reported here therefore implies that the sex ratios at birth discussed in the previous subsection (well above 110 during the nineteenth century and the early 1920s) are consistent with the available information on surviving children. These results therefore support the argument that infanticide and/or neglect of females was widespread in this period.

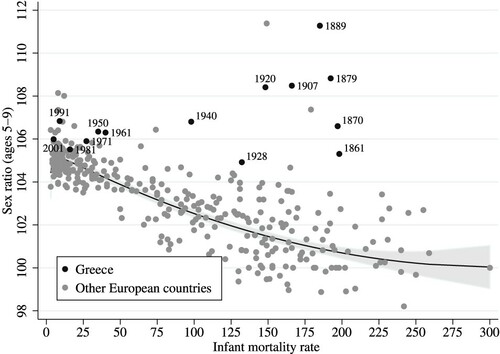

Analysing, instead, the 5–9 age group provides nearly the same picture (). This finding is crucial because this indicator is less subject to registration issues, as under-enumeration mainly affected infants (Hionidou Citation1993, p. 57). In this regard, it seems likely that the comparatively low figure (102.9) reported in the 1870 Census for children aged 0–4 is an artefact of the underlying quality of those numbers because the same census reported that there were 106.6 boys per 100 girls aged 5–9, which suggests that high sex ratios were the norm for that year as well. Looking at this age group also allows us to extend the analysis further back because, although the 1861 Census did not provide information on young children, it reported a relatively high sex ratio at ages 5–9 (105.3). Likewise, the Bavarian consul reported extremely distorted figures in 1839: a sex ratio of 119.2 among children aged 0–9 (Strong Citation1842, p. 49). Interestingly, as well as being more reliable, child sex ratios at older ages (5–9) provide a cumulative measure of excess mortality among females during birth, infancy, and childhood, and thus allow us to estimate the overall prevalence of discriminatory practices. The deviation between the observed figures and what would be expected, given the mortality environment, implies that gender discrimination resulted in ‘missing girls’ ranging between 4.6 and 10.4 per cent over the 1861–1920 period (depending on the particular census year; see Table A2, supplementary material).

Figure 3 Child sex ratios (ages 5–9) and infant mortality in Greece and Europe, 1750–2001

Notes: As the 1861 Census provided sex-specific information on children aged 5–9, it has also been included here. See the note below regarding the territorial changes the Kingdom of Greece underwent during the period reported here.

Source: As for .

The large imbalance in the relative numbers of boys and girls thus remained during the second half of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century, and it was not until 1928 that the figures in Greece began to resemble those in other countries. Although the significant drop in child sex ratios during the 1920s could be explained by changing attitudes towards girls, there are many potential confounders that make interpreting this shift difficult. The refugee crisis in Asia Minor in the early 1920s probably led to increased levels of infant and child mortality and could therefore have pushed sex ratios down due to the biological advantage of females. Likewise, these population movements also imply that the underlying population in the 1928 Census was not the same as in 1920, which further complicates the interpretation of what happened during this decade. Alternatively, increasing living standards could have made gender-based discriminatory practices less visible because they no longer translated into higher mortality for females. Improvements in data coverage, as civil registration became available in most Greek settings in 1925, could also have played a role in this shift. Nonetheless, it should be noted that sex ratios in the 5–9 age group remained slightly higher in Greece than in other countries with similar mortality environments, at least until 1940.

However, as Komis (Citation2004, p. 290) has pointed out, the predominance of boys reported in Greek sources can be explained by factors other than the excess mortality among females arising from gender discrimination. Valaoras (Citation1960, pp. 117–21), for instance, warned about the quality of the historical censuses, by arguing that the infant population was under-enumerated and that females were more likely to be omitted than males at nearly all ages (see also Valaoras Citation1960; NSSG Citation1966, p. 15). His assumptions are, however, questionable and Hionidou (Citation1993, p. 51) has suggested that higher levels of mortality among females might have been behind the excess of males (see also Siampos Citation1973, p. 57; Asdrahas Citation1978; Panagiotopoulos Citation1987; Caftantzoglou Citation1997; Komis Citation1999, Citation2004). Likewise, neither contemporary sources nor secondary literature support the possibility that girls were being under-registered. Censuses were conducted by a local committee that visited each household and collected information on each person living there (Hionidou Citation1993, p. 32), so there were no particular incentives to under-register girls.

The Central Statistical Office indeed noticed the excess of males in the 1881 Census and warned that the enumeration had been carried out under difficult circumstances. The census-takers, however, also indicated that they were expecting boys, not girls, to be under-reported, due to the military purpose of the census (Ministry of Interior Citation1884, p. ζ). In this regard, the early Greek censuses suffered from under-registration of males aged 18–24, because this age group was eligible for military service (Siampos Citation1973, pp. 57–8; Hionidou Citation1993, p. 144). This issue became less important from 1878 onwards due to changes in the legislation that made all men aged 24–40 eligible for military service, and thus reduced the under-registration of males in these age groups (Hionidou Citation1993, p. 20). Mass migration in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, however, raised these issues again because a significant fraction of young males emigrated to avoid military service (Saloutos Citation1964, pp. 31, 39–42).

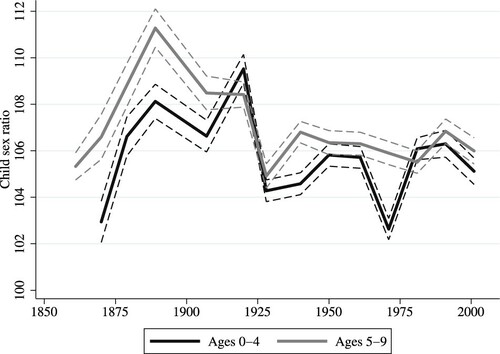

Moreover, as mentioned earlier, under-registration primarily affected infants (Hionidou Citation1993, p. 57). Although some infants may have escaped enumeration, this issue was due mostly to age misreporting. Many infants were reported as being one year old, so were registered in the ‘1–2’ age group, especially in the nineteenth-century censuses (Hionidou Citation1993, p. 144; Gavalas Citation2001, pp. 82–3). However, even if female infants had been more subject to under-enumeration, they should have been visible in the censuses as they grew up. The older age groups should have been less prone to under-enumeration, and lower sex ratios would be expected. depicts the evolution of sex ratios for different age groups over time and clearly shows that under-reporting of females was not on its own the cause of the high sex ratios observed in Greece in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries. Not only did the evolution of sex ratios at ages 5–9 mimic to some extent that of ages 0–4, but sex ratios were generally higher at older ages. This pattern is also evident in data from earlier sources: in 1839, for instance, the sex ratio was 111.8 at birth but 119.2 for the 0–9 age group (Strong Citation1842, pp. 46–9). These findings therefore suggest that gender discrimination resulted in excess mortality for females, not only at birth but throughout infancy and childhood.

Figure 4 Child sex ratios (ages 0–4 and 5–9) in Greece, 1861–2001

Note: The dashed lines reflect the corresponding confidence intervals at the 95 per cent level.

Source: Mitchell (Citation2013).

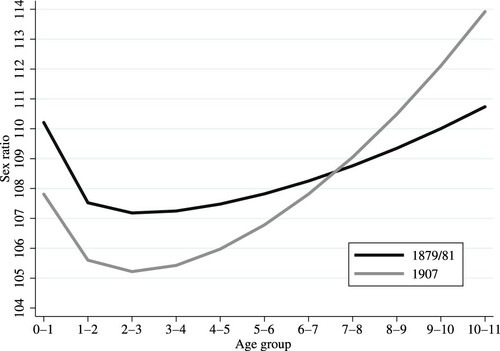

A closer look at the 1879–81 and 1907 Population Censuses provides further evidence that as well as being high at young ages, sex ratios increased as children grew older (; see also Table A3, supplementary material). This evolution stands in marked contrast to the trend seen in other countries where gender discrimination was not an issue, for example England or the Netherlands (Beltrán Tapia Citation2019, p. 8; Figure A2, supplementary material). As explained earlier, the biological advantage of females should result in more boys than girls dying, especially during the first years of life, when mortality is higher. Sex ratios are thus expected to decline or remain flat as infants grew older. The atypical age pattern observed in the Greek data arguably suggests that gender discrimination led to increases in mortality for females at birth, in infancy, and throughout childhood. Even the Italian case, which shared a number of economic and social features present in Greece, did not exhibit such an extreme pattern.

Figure 5 Sex ratios in infancy and childhood, by age group, 1879–81 and 1907

Notes: Given that many infants were registered as being one year old (and were thus counted in the ‘1–2’ age group) and that age heaping might also have affected registration around particular ages (especially around ages five and ten), actual sex ratios are smoothed using a fractional polynomial (the raw data are reported in Table A2, supplementary material). The initial decline in sex ratios from the ‘0–1’ to the ‘1–2’ age group is expected due to the biological advantage of females during this crucial stage (especially in a high-mortality environment).

Source: Ministry of Interior (Citation1881, Citation1884, Citation1909).

Migration might also be an issue if either boys or girls were more likely to move away. Greeks often resorted to seasonal or permanent migration to regulate the size of the local population (Hionidou Citation2002), making this an important safety valve for balancing population pressures. However, as most of those who migrated were young single (adult) men (Psychogios Citation1984, pp. 164–5; Tsoukalas Citation1987, pp. 112–23; Caftantzoglou Citation1997, pp. 412–3; Hionidou Citation1999, p. 407, Citation2002, pp. 70–1; Citation2016, p. 55), it is unlikely that migration can explain away our results. Due to a strict moral code designed to prevent premarital sexual relations, working outside the parental household was not considered desirable for women, especially for young single women whose chances of getting married could be jeopardized (Garnett Citation1914, p. 200; Stott Citation1973, pp. 125, 127; Hionidou Citation1995, pp. 78, 92, Citation1999, p. 418). Although single girls could be sent into domestic service to alleviate household poverty or to contribute to their own dowries (Sant Cassia and Bada Citation1992, p. 191; Hionidou Citation2005), this form of employment rarely involved girls younger than ten years old. Likewise, while it is plausible that children participated in migratory flows by accompanying their parents, since most migrants were male it is very unlikely that they took their female children with them. There is very little information about sex-specific migration at early ages but, if anything, it was boys who were more likely to be absent (Hionidou Citation1993, p. 57, Citation2016, p. 54), so child sex ratios should decrease as children get older. Figures 4 and 5 actually show the opposite, thus providing evidence that higher sex ratios at older ages were the result of discriminatory practices against girls.

Child sex ratios in Greek families in the US

Mass migration started in the late nineteenth century due to the economic consequences of the Greek ‘currant crisis’, as well as other structural factors (Tsoukalas Citation1987, pp. 150–1; Kitroeff Citation2000, p. 125). Apart from the significant internal migration from rural areas to urban centres, around half a million Greeks also migrated abroad, mostly young males going to the US. A crucial reason why under-registration of females is not likely to be the main factor behind the high child sex ratios observed in late-nineteenth-century Greece is that there was also an imbalance in the relative numbers of boys and girls born to Greek migrants in the US.

Relying on the US population censuses between 1900 and 1940 (Ruggles et al. Citation2019), we computed the sex ratios of children born in the US to Greek parents. In order to avoid the effect of the presence of other cultures in mixed couples, we counted only those children whose parents were both Greek. As shows, child sex ratios (at ages 0–4 and 5–9) in 1900 and 1910 were around 115 boys per 100 girls or higher. Apart from being significantly higher than those observed for children whose parents both were born in the US (around 102 in 1900 and 1910; see Table A4, supplementary material), these sex ratios are even higher than those found in the Greek censuses at the time. This finding therefore suggests that under-registration of females did not play a major role in the sex ratios reported in the homeland. Although the numbers of children underlying the sex ratios for 1900 are admittedly small, the sample sizes for 1910 are large enough to confirm that the observed child sex ratios are statistically different from 101 (or an even higher benchmark). Restricting the analysis in to only those children born in the US, to avoid capturing migratory choices, reduced the sample size but still yielded extremely high figures: child sex ratios (ages 0–9) in 1900 and 1910 were 109.6 and 111.3, respectively. The relative numbers of boys and girls fell drastically in 1920 and continued declining up to 1940 (), thus suggesting that gender-based discriminatory practices resulting in excess mortality for females in infancy and childhood were receding in the US slightly earlier than in Greece.

Table 1 Child sex ratios in the US, 1900–40: children where both parents are Greek

These figures suggest that, despite living in a totally different environment from that of their homeland, the first generation of Greek immigrants in the US did not leave their cultural values behind, especially their strong son preference and attitudes towards girls. These migrants were mostly young males: either singles or married men who had left their wife and children in Greece (Xenides Citation1922, p. 95; Saloutos Citation1964, pp. 45, 85; Kitroeff Citation2000). As soon as they secured a job, they brought their family over or asked their parents to find a bride in their home village. Although very little is known about whether Greek parents in the US treated their sons and daughters differently, it appears that these first migrants succeeded in carrying the Greek social and cultural life over to their new environment (Saloutos Citation1956, p. 71). The literature has stressed that this highly patriarchal culture pressured women to remain in the domestic sphere and endure hardships for their family (Xenides Citation1922, p. 86; Saloutos Citation1964, pp. 85–8, 311; Patrona Citation2015, p. 87). Indeed, women did not work outside the home because this was perceived as acting against men’s honour (Abbot Citation1909, p. 388; Lacey Citation1916, p. 54; Saloutos Citation1956, p. 87). It is interesting to note that Xenides (Citation1922, pp. 91–2) referred to the ‘evil custom of dowry’ indicating that although less important than in the homeland, this practice had not been entirely abandoned. Likewise, Saloutos (Citation1956, p. 314) argued that the position of daughters, especially in poor traditional families, was not an enviable one and that their ‘plight was aggravated by the greater degree of subservience to which she was subjected’. Living in a different context nonetheless eroded Greek customs and traditions from the First World War onwards (Saloutos Citation1956, p. 256), a timing that coincides with the decrease in child sex ratios reported in .

Qualitative evidence on infanticide and neglect of females during infancy and childhood

The previous section showed that under-reporting and sex-specific migration cannot account for the distorted child sex ratios observed in Greece during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, direct evidence of discriminatory practices resulting in excess mortality among females is limited. Contemporary accounts by either Greek intellectuals or foreign travellers stressed the inferior position of women but were mostly silent about the infanticide or mortal neglect of young girls. The high levels of infant and child mortality in Greece at the time might nonetheless have facilitated the concealment of certain practices (i.e. smothering, suffocation, irregular feeding, exposure to cold, etc.), as such deaths could easily have been considered as resulting from natural causes (Hrdy Citation1999; Derosas and Tsuya Citation2010). The story in The Murderess clearly reflects this possibility: ‘There had been no particular commotion about the little daughter of Delcharo Trachilaina, they buried her the same day … Obviously, the child had died of fever’ (Papadiamantis Citation1983, p. 49). Alternatively, parents who deliberately killed newborns could have reported them as stillbirths (Drixler Citation2013, p. 206; Hanlon Citation2016, p. 537). As well as being easily reported as stillbirths, infant deaths occurring within the first days of life may have escaped registration (Hionidou Citation1993, p. 123).

Oral evidence from Lefkada in the Ionian Islands, a British protectorate until 1864, suggests that many families suffocated their unwanted children, a practice that seems to have been more common for girls (Tomara-Sideri and Sideris Citation1986, p. 44). Furthermore, Vlachogiannis (Citation1938, p. 12) reported that the inhabitants of the island of Skopelos in the Sporades decided to abolish the dowry system in 1836, as it was seen as responsible for many secret infanticides of females and disputes between parents when a female infant was born. Varikas (Citation2011, p. 66) also referred to the story of a grandmother who tried to comfort her grandson with the hope that his newborn twin sisters would die (since if they lived, they would be a great burden to their family) (Anon Citation1898, p. 82). Although Varikas indicated that ‘unfortunately there are no studies on different child mortality rates, so it is impossible to find out to what extent people had contributed to the administration of divine justice’, she suggested that infanticide of females was a very likely explanation for many deaths.

The cruellest description of infanticide and neglect of females can be found in the Ladies’ Journal, perhaps the most influential contemporary publication in Greece edited by and addressed to women. A paper about the incognito Queen’s tour through the Peloponnese in April 1887 described the misfortune of rural women and the woeful reception of newborn girls by their fathers (Parren Citation1887a; see also Anon Citation1887a, p. 2). According to this account, mothers who had committed the sacrilege of giving birth to a female infant were not only beaten by their husbands, but kicked out of the house. As girls were growing up, they were left hanging from trees at the mercy of God and the ‘non-bloodthirsty’ animals (goats and pigs), and often died of suffocation. In a subsequent issue, a reader reported that mothers in most areas of the country preferred to kill their one- or two-day-old female infants in order to relieve their families of the burden (Anon Citation1887b, p. 4). Although it is unclear how literal these descriptions were, they nonetheless strongly suggest the existence of discriminatory practices against girls.

In interviews carried out in rural villages in 1962, old women (who were probably born in the late nineteenth century) could often not recall how many of their children had died (Blum and Blum Citation1965, pp. 73–4). Many of these women appeared reluctant or unable to recall abortions or miscarriages and they actually confused abortions, ‘nine-month abortions’ (occurring at nine months’ gestation), stillbirths, and infanticides, practices that seem to have been relatively common. According to a local priest, around 20 per cent of all infants were intentionally aborted or killed at birth (Blum and Blum Citation1965, p. 76). It was also reported that many villagers believed that infanticide could be justified under certain circumstances: not only were unbaptized children not treated as fully human, but some infants could even be considered demons. The devilish nature of some newborns was often attributed to the infant’s origins, including whether they were wanted. In this regard, female infants were considered more likely candidates for nine-month abortions than males (Blum and Blum Citation1965, p. 75). Writing about her experiences in a Greek village in the 1970s, Du Boulay (Citation1983, p. 245) recounted two cases in the previous 25 years that had resulted in the mortal neglect of two female infants: one was cast out into a ditch to die, and the other was neglected and subsequently died. Regardless of the anecdotal nature of this evidence, these episodes stress how entrenched the underlying attitudes towards girls were and how real the temptations to get rid of unwanted girls continued to be, even well into the twentieth century.

Likewise, there is evidence that nineteenth-century Greek families were abandoning more girls than boys. Around 60 per cent of the children who entered the Athens Foundling Hospital between 1859 and 1884 were girls, and Zinnis, the director of that institution, attributed this situation to the subordinate position of girls in nineteenth-century Greece, especially among the poor (Korasidou Citation1995, pp. 112–13). More females were also being abandoned in other areas, such as Hermoupolis and Kephallenia (Gallant Citation1991, pp. 492–3; Loukos Citation1994, p. 256). Poverty and the kinship system, rather than illegitimacy, were the main drivers of child abandonment and its selectivity in Kephallenia, where young girls were marginalized and placed in an extremely vulnerable position in the nineteenth century (Gallant Citation1991, p. 503). There is also evidence of girls being abandoned, even at older ages, in Cyprus during the 1930s, a period of extreme poverty and hardship (Argyrou Citation1996, p. 32). As in other countries around that time, child abandonment could be considered a sort of ‘deferred infanticide’ (Johansson Citation1984). Loukos (Citation1994, p. 256), for instance, estimated that around 60 per cent of these foundlings died within the first year in Hermoupolis between 1873 and 1910. It seems also that the increase in the number of foundlings in Greece occurred in parallel to the decline in infanticides (Loukos Citation1994, p. 256). It should, however, be noted that the number of foundlings probably underestimates the total number of abandoned children because it is likely that many of them never reached these institutions alive.

As well as from infanticide, abandonment, or mortal neglect, excess mortality among girls could also have arisen from more indirect mechanisms. There is some evidence from nineteenth-century Britain and continental Europe that parents treated their sons differently from their daughters (Johansson Citation1984; Baten and Murray Citation2000; McNay et al. Citation2005; Horrell and Oxley Citation2016). An unequal allocation of resources within the household (food, care, and/or workload) translated into girls experiencing lower nutritional status and higher morbidity, which, in turn, affected their heights and mortality. In a study of a mountainous village in central mainland Greece, Papathanassiou (Citation2004, pp. 332–3) found that food was distributed in ways that gave priority to men and that girls tended to be given a heavier workload than boys. Moreover, census reporters observed that females in general worked very hard, something that probably increased their mortality (Hionidou Citation1993, p. 150). Similarly, in Karpathos, younger female children were not only discriminated against in terms of food and clothing, but were also assigned the hardest tasks (Vernier Citation1984, p. 38).

As described in the previous section, and contrary to what would be expected, child sex ratios in Greece increased with age during the second half of the nineteen century and the first decades of the twentieth century. These findings suggest that discriminatory practices were leading to increased mortality among females during childhood. In this regard, Stéphanos (Citation1884, p. 473) noted that despite the biological survival advantage of females, more girls than boys were dying during the first year of life (especially at 6–12 months old) between 1863 and 1878, and he linked this anomaly to the prevalence of gastrointestinal diseases in Greece. Given that breastfeeding confers some protection against such diseases, this observation may indicate that girls were weaned earlier than boys. The detailed family reconstitution carried out by Hionidou (Citation1993, pp. 129, 149, Citation1997, p. 161) on Mykonos also showed that infant mortality was higher for girls than for boys during the 1859–78 period. Interestingly, the gap in life expectancy between males and females was even higher for the 1–4 age group than for infants, which indicates that excess mortality among females was affecting girls not only in the first year of life, but throughout childhood. Indeed, Hionidou (Citation1993, p. 149) stressed how unexpected these figures were, but did not dig more deeply into this issue. A similar pattern has, however, been found in Hermoupolis during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when mortality tended to be higher for females than males in infancy, and especially in early childhood (Raftakis Citation2019, pp. 305–9). This finding is especially telling because, if anything, girls were under-reported in death registers, so the observed figures provide only a minimum estimation of the mortality gap between the sexes.

Concluding remarks

Son preference was a crucial feature of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Greek society. The results of the analysis carried out here strongly suggest that in a context of generalized poverty, gender discrimination resulted in excess mortality for females at birth and throughout infancy and childhood. At least until the 1920s, child sex ratios were extremely high, and not just early in life: they increased as children grew older, thus evidencing that these distortions cannot be explained only by under-registration of females. The 1900 and 1910 US Censuses also showed large imbalances in the numbers of sons and daughters born to Greek families. This finding not only further supports the conclusion that the distorted sex ratios observed in Greece were not a statistical artefact of the quality of Greek censuses; it also suggests that the first wave of migrants did not leave these gender-based discriminatory practices behind.

Identifying, however, which practices led to these imbalances in sex ratios is challenging. It is likely that the infanticide, mortal neglect, and abandonment of infant girls all contributed to this phenomenon. Moreover, sex ratios grew steadily throughout childhood, which indicates that families were prioritizing boys over girls in terms of the distribution of resources. In a society where families were living close to subsistence levels and mortality was high, differences in the ways that parents treated boys and girls in terms of the distribution of food, childcare, and workload likely contributed to their relative mortality due to malnutrition and illness. There is indeed considerable qualitative evidence from a wide range of sources (contemporary commentators, folklore traditions, feminist newspapers, and anthropological studies) showing that families privileged sons in different ways, including neglect of females. This tendency was probably even more acute in large families, especially those with several daughters.

The substantial gap between the observed child sex ratios in Greece and what would be expected in the absence of discrimination (Figures 2 and 3) allows an estimation of the magnitude of this phenomenon. In particular, the deviation at older ages provides a measure of the cumulative impact of gender bias in perinatal, infant, and child mortality and, consequently, the prevalence of discriminatory practices. As the level of under-registration at these ages was probably negligible, this approach provides an accurate picture of this tragedy. Given the mortality environment of Greece in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the child sex ratio should have been around 101 (see also Table A2, supplementary material). Compared with this benchmark, the observed figures imply that around 4.6–10.4 per cent of Greek girls, depending on the particular year, went ‘missing’ during this period.

The kinship and dowry systems crucially shaped the underlying attitudes towards girls. It is, however, likely that other economic, social, and cultural factors also played a role by affecting the relative values assigned to boys and girls. The fear of violence, for instance, may have influenced not just the demand for boys, but the perception of girls as liabilities because they needed to be defended. The latter can also be seen as a feature of the honour culture existing in Greece and other Mediterranean regions. However, more research is needed to assess how these practices may have varied within Greece, as well as to determine the relative importance of conflict, family types, inheritance rules, and dowry systems in shaping excess mortality among females. This paper is only a first step towards re-evaluating the prevalence of gender-based discriminatory practices in Modern Greek society, an issue that has long been neglected despite all the hints that pointed in this direction.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (150.3 KB)Notes

1 Please direct all correspondence to Francisco J. Beltrán Tapia, Department of Modern History and Society, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Dragvoll, 7048, Trondheim, Norway; or by Email: [email protected]

2 We are grateful to Eftychia Kalaitzidou for invaluable research assistance. We are also thankful to the editor and the anonymous referees for their detailed comments and suggestions.

3 This research received financial support from the Research Council of Norway (project 301527).

References

- Abbot, G. 1909. A study of the Greeks in Chicago, American Journal of Sociology 15(3): 379–393. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/211787

- Alesina, A., P. Guiliano, and N. Nunn. 2013. On the origins of gender roles: Women and the plough*, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(2): 469–530. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt005

- Alexakis, E. 1984. E Eksagora tes Nyfes. Symvole ste Melete ton Gamilion Thesmon ste Neotere Ellada [The Bride-Price. A Contribution to the Study of Marriage Customs in Modern Greece]. Athens.

- Anderson, S., and D. Ray. 2010. Missing women: Age and disease, Review of Economic Studies 77: 1262–1300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-937X.2010.00609.x

- Anon. 1887a. Dromologio tes periodeias tes vasilikes oikogeneias [The itinerary of the royal family tour], Akropolis, 1767, 19 April 1887:2.

- Anon. 1887b. Meteres paidoktonoi [Mothers child-murderers], Efemeris ton Kyrion [Ladies’ Journal] A/12: 3–4.

- Anon. 1898. Selides Tines tes Istorias tou Vasileos Othonos [Pages of the Story of King Otto]. Athens: Publisher Karolos Mpek.

- Argyrou, V. 1996. Tradition and Modernity in the Mediterranean: The Wedding as Symbolic Struggle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Asdrahas, S. 1978. Mechanismoi tes Agrotikes Oikonomias sten Tourkokratias (IE- IST aionas [Mechanisms of the Peasant Economy in the Period of Turkish Rule (15th–16th Centuries)]. Athens: Themelio.

- Avdela, E. 2005. Between duties and rights: Gender and citizenship in Greece, 1864–1952, in F. Birtek and T. Dragonas (eds), Citizenship and the Nation-State in Greece and Turkey. London: Routledge, pp. 117–143.

- Bafounis, G. 1984. Gamoi sten Ermoupole (1845–1853) [Marriages in Hermoupolis (1845–1853)], Mnemon 9: 211–243. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/mnimon.274

- Baten, J., and J. E. Murray. 2000. Heights of men and women in 19th-century Bavaria: Economic, nutritional and disease influences, Explorations in Economic History 37(4): 351–369. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/exeh.2000.0743

- Becker, A. 2019. On the economic origins of restrictions on women’s sexuality. CESifo Working Paper 7770.

- Beltrán Tapia, F. J. 2019. Sex ratios and missing girls in late-19th-century Europe. EHES Working Paper 160.

- Beltrán Tapia, F. J., and D. Gallego-Martínez. 2017. Where are the missing girls? Gender discrimination in 19th-century Spain, Explorations in Economic History 66: 117–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2017.08.004

- Beltrán Tapia, F. J., and D. Gallego-Martínez. 2020. What explains the missing girls in 19th century Spain? The Economic History Review 73(1): 59–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12772

- Beltrán Tapia, F. J., and F. Marco-Gracia. 2020. Death, sex and fertility: Female infanticide in rural Spain, 1750-1950. EHES Working Paper 186.

- Beltrán Tapia, F. J., M. Szoltysek, B. Ogórek, and S. Gruber. 2021. Inferring “missing girls” from child sex ratios in European historical census data: A conservative approach. CEPR Discussion Paper Series 15818.

- Beneito, P., and J. J. García-Gómez. 2019. Gender gaps in wages and mortality rates during industrialization: The case of Alcoy, Spain, 1860–1914. Discussion Papers in Economic Behaviour 0119. University of Valencia, ERI-CES.

- Bhalotra, S., A. Chakravarty, and S. Gulesci. 2020. The price of gold: Dowry and death in India, Journal of Development Economics 143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.102413

- Blum, R., and E. Blum. 1965. Health and Healing in Rural Greece. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Caftantzoglou, R. 1994. The household formation pattern of a Vlach mountain community of Greece: Syrrako 1898–1929, Journal of Family History 19(1): 79–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/036319909401900104

- Caftantzoglou, R. 1997. Syggeneia kai Organose tou Oikiakou Chorou. Syrrako, 1898–1930 [Kinship and Organisation of the Household Space. Syrrako, 1898–1930]. Athens: National Centre for Social Research.

- Campbell, J. K. 1964. Honour, Family and Patronage: A Study of Institutions and the Moral Values in a Greek Mountain Community. Oxford: University of Oxford.

- Campbell, J. K. 1970. Honour and the devil, in J. G. Peristiany (ed.), Honour and Shame: The Values of Mediterranean Society. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, pp. 141–170.

- Couroucli, M. 1987. Dot et société en Grèce Moderne, in G. Ravis-Giordani (ed.), Femmes et Patrimonie dans les Sociétiés Rurales de l’Europe Méditerranée. Paris: Editions du Centre National du Recherche Scientifique, pp. 327–348.

- Danforth, L. M. 1982. The Death Rituals of Rural Greece. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Das Gupta, M. 2017. Return of the missing daughters, Scientific American 317(3): 80–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0917-80

- Das Gupta, M., J. Zhenghua, L. Bohua, X. Zhenming, W. Chung, and B. Hwa-Ok. 2003. Why is son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? A cross-country study of China, India and the Republic of Korea, The Journal of Development Studies 40(2): 153–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331293807

- Derosas, R., and N.O. Tsuya. 2010. Child control as a reproductive strategy, in N. O. Tsuya, F. Wang, G. Alter, and J. Z. Lee (eds), Prudence and Pressure: Reproduction and Human Agency in Europe and Asia, 1700–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 129–155.

- Dimen, M. 1986. Servants and sentries. Women, power, and social reproduction in Kriovrisi, in J. Dubisch (ed.), Gender and Power in Rural Greece. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 53–67.

- Drixler, F. 2013. Mabiki. Infanticide and Population Growth in Eastern Japan, 1660–1950. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Drixler, F. 2016. Hidden in plain sight: Stillbirths and infanticides in Imperial Japan, The Journal of Economic History 76(3): 651–696. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050716000814

- Drixler, F., and J. Kok. 2016. A lost family-planning regime in eighteenth-century Ceylon, Population Studies 70(1): 93–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2015.1133842

- Du Boulay, J. 1974. Portrait of a Greek Mountain Village. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Du Boulay, J. 1983. The meaning of dowry: Changing values in rural Greece, Journal of Modern Greek Studies 1(1): 243–270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/mgs.2010.0051

- Du Boulay, J. 1984. The blood: Symbolic relationships between descent, marriage, incest prohibitions and spiritual Kinship in Greece, Man 19(4): 533–556. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2802325

- Evans, A. 2019. How cities erode gender inequality: A new theory and evidence from Cambodia, Gender & Society 33(6): 961–984. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243219865510

- Fairchild, H. 1911. Greek Immigration to the United States. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Ferriman, Z.D. 1910. Home life in Hellas. London: Mills & Boon.

- Franghiadis, A. 1998. Dowry, capital accumulation and social reproduction in 19th century Greek agriculture, Mélanges de l’Ecole Française de Rome, Italie et Méditerranée 110(1): 187–192. doi:https://doi.org/10.3406/mefr.1998.4548

- Friedl, E. 1964. Vasilika. A Village in Modern Greece. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Friedl, E. 1967. The position of women: Appearance and reality, Anthropological Quarterly 40(3): 97–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3316943

- Gallant, T. W. 1991. Agency, structure, and explanation in social history: The case of the foundling home on Kephallenia, Greece, during the 1830s, Social Science History 15(4): 479–508. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0145553200021258

- Gallant, T. W. 2015. The Edinburgh History of the Greeks, 1768 to 1913: The Long Nineteenth Century. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Garnett, L. M. J. 1914. Greece of the Hellenes. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Gavalas, V. S. 2001. Demographic reconstruction of a Greek island community: Naoussa and Kostos, on Paros, 1894–1998. Unpublished PhD dissertation, London School of Economics and Political Science, London.

- Gavalas, V. S. 2008. Marriage patterns in Greece during the twentieth century, Continuity and Change 23(3): 509–529. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0268416008006826

- Gavalas, V. S., K. Rontos, and N. Nagopoulos. 2015. Sex ratio at birth in twenty-first century Greece: The role of ethnic and social groups, Journal of Biosocial Science 47(3): 363–375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932014000182

- Giuliano, P. 2017. Gender: An historical perspective, NBER Working Papers 23635.

- Guilmoto, C. Z. 2018. Sex ratio imbalances in Asia: An ongoing conversation between anthropologists and demographers, in S. Srinivasan and S. Li (eds), Scarce Women and Surplus Men in China and India. Demographic Transformation and Socio-Economic Development, Vol 8. Cham: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63275-9_8.

- Hanlon, G. 2016. Routine infanticide in the West, 1500–1800, History Compass 14: 535–548. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12361

- Herzfeld, M. 1985. The Poetics of Manhood. Contest and Identity in a Cretan Mountain Village. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hesketh, T., and Z. W. Xing. 2006. Abnormal sex ratios in human populations: Causes and consequences, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103(36): 13271–13275. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0602203103

- Hionidou, V. 1993. The demography of a Greek island, Mykonos 1859–1959. A family reconstitution study. Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Liverpool, Liverpool.

- Hionidou, V. 1995. Nuptiality patterns and household structure on the Greek island of Mykonos, 1859–1959, Journal of Family History 20(2): 67–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/036319909502000204

- Hionidou, V. 1997. Infant mortality in Greece, 1859–1959: Problems and research perspectives, in C. A. Corsini and P. P. Viazzo (eds), The Decline of Infant and Child Mortality. The European Experience: 1750-1990. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, pp. 155–172.

- Hionidou, V. 1999. Nineteenth-century urban Greek households: The case of Hermoupolis, 1861–1879, Continuity and Change 14(3): 403–427. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0268416099003380

- Hionidou, V. 2002. ‘They used to go and come’. A century of circular migration from a Greek Island, Mykonos 1850 to 1950, Annales de Démographie Historique 104(2): 51–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.3917/adh.104.0051

- Hionidou, V. 2005. Domestic service on three Greek islands in the later 19th and early 20th centuries, The History of the Family 10(4): 473–489. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hisfam.2005.09.008

- Hionidou, V. 2011. Independence and inter-dependence: Household formation patterns in eighteenth century Kythera, Greece, The History of the Family 16(3): 217–234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hisfam.2011.03.005

- Hionidou, V. 2016. From modernity to tradition: Households on Kythera in the early nineteenth century, in S. Sovic, P. Thane, and P. P. Viazzo (eds), The History of Families and Households: Comparative European Dimensions. Leiden: Brill, pp. 47–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004307865_004

- Horrell, S., and D. Oxley. 2016. Gender bias in nineteenth-century England: Evidence from factory children, Economics & Human Biology 22: 47–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2016.03.006

- Hrdy, S. B. 1999. Mother Nature: A History of Mothers, Infants and Natural Selection. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Iqbal, N., A. Gkiouleka, A. Milner, D. Montag, and V. Gallo. 2018. Girls’ hidden penalty: Analysis of gender inequality in child mortality with data from 195 countries, BMJ Global Health 3: e001028. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001028

- Jayachandran, S. 2015. The roots of gender inequality in developing countries, Annual Review of Economics 7(1): 63–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115404

- Johansson, S. R. 1984. Deferred infanticide: Excess female mortality during childhood, in G. Hausfater and S. Hrdy (eds), Infanticide: Comparative and Evolutionary Perspectives. New York: Aldine, pp. 463–485.

- Kasdagli, A. E. 2004. Family and inheritance in the Cyclades, 1500–1800: Present knowledge and unanswered questions, The History of the Family 9(3): 257–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hisfam.2004.01.008

- Kasdagli, A. E. 2005. Dowry and inheritance, gender and empowerment in the ‘Notarial societies’ of the Early Modern Greek World, in G. Jacobsen, H. Vogt, I. Dübeck and H. Wunder (eds), Less Favored–More Favored: Proceedings from a Conference on Gender in European Legal History, 12th-19th Centuries. Copenhagen: The Royal Library, pp. 1–10.

- Kitroeff, A. 2000. Yperatlantike Metanastefse [Transatlantic migration], in C. Hadziiossif (ed.), Istoria tes Elladas tou 20ou aiona. 1900–1922. Oi Aparches [History of Greece in the 20th Century. 1900–1922. The Beginning]. A, 1. Athens: Vilviorama, pp. 123–171.

- Klasen, S., and C. Wink. 2003. “Missing women”: Revisiting the debate, Feminist Economics 9(2-3): 263–299. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570022000077999

- Komis, K. 1999. Demographikes Opseis tes Prevezas 16os–18os aionas [Demographic Dimensions of Preveza 16th –18th century]. Ioannina: University of Ioannina.

- Komis, K. 2004. Demographic aspects of the Greek household: The case of Preveza (18th century), The History of the Family 9(3): 287–298. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hisfam.2004.01.010

- Korasidou, M. 1995. Oi Athlioi ton Athenon kai oi therapeftes tous. Ftocheia kai filanthropia sten Ellenike Protevousa to 19o Aiona [The Miserables of Athens and their therapists. Poverty and Philanthropy in the Greek Capital during the 19th Century]. Athens: Typothyto.

- Kosmatou E. 2000. La population des Iles Ioniennes: XVIIIeme-XIXeme siècle. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Université de Paris I, Paris.

- Lacey, T. J. 1916. A Study of Social Heredity as Illustrated in the Greek People. New York: E.S. Gorham.

- Lambiri-Dimaki, J. 1972. Dowry in modern Greece: An institution at the crossroads between persistence and decline, in C. Safilios-Rothschild (ed.), Towards a Sociology of Women. Lexington, MA: Xerox College, pp. 73–83.

- Lawson, J. C. 1910. Modern Greek Folklore and Ancient Greek Religion. A Study in Survivals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Loukos, C. 1994. Ta ektheta vrefe tes Ermoupoles: Ta prota thymata tes pathologias mias koinonias [Foundling infants of Hermoupolis: First victims of a society’s pathology?], in Afieroma ston Kathegete Vasileio Vl. Sfyroera [A Tribute to the Professor Vasileios Vl. Sfyroeras]. Athens: Lychnos Publishers, pp. 247–264.

- Lynch, K. A. 2011. Why weren’t (many) European women “missing”? The History of the Family 16(3): 250–266. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hisfam.2011.02.001

- Manfredini, M., M. Breschi, and A. Fornasin. 2016. Son preference in a sharecropping society. Gender composition of children and reproduction in a pre-transitional Italian community, Population 71(4): 641–658. doi:https://doi.org/10.3917/popu.1604.0683

- Manfredini, M., M. Breschi, and A. Fornasin. 2017. Mortality differentials by gender in the first years of life: The effect of household structure in Casalguidi, 1819–1859, Essays in Economic and Business History 35(1): 291–314. https://www.ebhsoc.org/journal/index.php/ebhs/article/view/45

- Marco-Gracia, F. J., and F. J. Beltrán Tapia. 2020. Son preference, gender discrimination and missing girls in rural Spain, 1750-1950, AEHE Working Paper 2007. https://www.aehe.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/

- Mattison, S. M., B. Beheim, B. Chak, and P. Buston. 2016. Offspring sex preferences among patrilineal and matrilineal Mosuo in Southwest China revealed by differences in parity progression, Royal Society Open Science 3: 160526. doi:https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160526

- Mavisakalyan, A., and A. Minasyan. 2018. The role of conflict in sex discrimination: The role of missing girls, GLO Discussion Paper Series 217.

- McNay, K., J. Humphries, and S. Klasen. 2005. Excess female mortality in nineteenth-century England and Wales, Social Science History 29(4): 649–681. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0145553200013341

- Michaleas, S. N., and T. N. Sergentanis. 2019. Dowries in Greece: Dowry contracts in Ioannina during the early twentieth century, The History of the Family 24(4): 675–706. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1081602X.2019.1641129

- Miller, W. 1905. Greek Life in Town and Country. London: George Newnes.

- Ministry of Interior. Statistics of Greece. 1862a, 1866a–1889a. Kinesis tou plethysmoy kata to etos (1860), (1864–1883), (1885) [Population Movement During the Year (1860), (1864–1883), (1885)]. Athens: National Printing Press.

- Ministry of Interior. 1881. Plethysmos 1879 [Population 1879]. Athens: National Printing Press.

- Ministry of Interior. 1884. Pinakes eparchion Epeirou kai Thessalias kata ten apographe tou 1881 [Tables of Provinces of Epirus and Thessaly in the 1881 Census]. Athens: National Printing Press.

- Ministry of Interior. 1909. Statistika apotelesmata tes genikes apographes tou plethysmou kata ten 27 Oktovriou 1907 [Statistical Results of the General Population Census in 27th October 1907]. Athens: National Printing Press.

- Mitchell, B. R. 2013. International Historical Statistics, 1750–2010. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- National Statistical Service of Greece (NSSG). 1956. Statistike tes physikes kineseos tou plethysmou tes Ellados kata to etos 1956 [Statistics of Natural Movement of Population of Greece by the Year 1956]. Athens: NSSG.

- National Statistical Service of Greece (NSSG). 1966. Demographikai ropai kai mellontikai proektaseis tou plethysmou tes Ellados, 1960–1985 [Demographic Trends and Population Projections of Greece, 1960–1985]. Athens: NSSG.

- Panagiotopoulos, V. 1987. Plethysmos kai Oikismoi tes Peloponnesou, 13os–18os Aionas [Population and Settlements of Peloponnese, 13th–18th Century]. Athens: Istoriko Archeio Emporikes Trapezas.

- Papadiamantis, A. 1983 [1903]. The Murderess. New York: New York Review Books.

- Papathanassiou, M. 2004. Aspects of childhood in rural Greece: Children in a mountain village (ca. 1900–1940), The History of the Family 9(3): 325–345. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hisfam.2004.01.013

- Paradelles, T. 1995. Apo te viologike gennese sten koinonike: Politismikes kai teletourgikes diastaseis tes genneses ston elladiko choro tou 19ou aiona [From biological birth to social birth: Cultural and ritual aspects of birth in 19th century Greece]. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Panteion University, Athens.

- Parren, K. 1887a. E Vasilissa periodevei [The Queen’s tour], Efemeris ton Kyrion [Ladies’ Journal] A/9: 3–4.

- Parren, K. 1887b. Gamoi htoi synallagai emporikai [Marriages were commercial transactions], Efemeris ton Kyrion [Ladies’ Journal] A/21: 1–2.

- Parren, K. 1888. Diati oi pateres thlivontai epi te gennesei thygatros [Because fathers grieve at the birth of a daughter], Efemeris ton Kyrion [Ladies’ Journal] B/76: 1–2.

- Patrona, T. 2015. The forgotten female voices of the Greek Diaspora in the United States, The Journal of Modern Hellenism 31: 87–100.

- Peristiany, J. G. 1965. Honour and Shame: The Values of Mediterranean Society. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Petmezas, S., and E. Papataxiarchis. 1998. The devolution of property and kinship practices in late-and post-Ottoman ethnic Greek societies. Some demo-economic factors of 19th and 20th century transformations, Mélanges de L’École Française de Rome. Italie et Méditerranée 110(1): 217–241. doi:https://doi.org/10.3406/mefr.1998.4553

- Pinnelli, A., and P. Mancini. 1997. Gender mortality differences from birth to puberty in Italy 1887–1940, in C.A. Corsini and P.P. Viazzo (eds), The Decline of Infant and Child Mortality. The European Experience: 1750–1990. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, pp. 73–93.

- Psychogios, D. K. 1984. Symvole ste melete ton demographikon phainomenon tou 19ou aiona [A contribution to the study of demographic events of the 19th century], Greek Review of Social Research 36: 133–200.

- Psychogios, D. K. 1987. Proikes, Foroi, Stafida kai Psomi: Oikonomia kai Oikogeneia sten Agrotike Ellada tou 19ou Aiona [Dowries, Taxes, Currants and Bread: Economy and Family in Rural Greece during the 19th Century]. Athens: National Centre for Social Research.

- Qian, N. 2008. Missing women and the price of tea in China: The effect of sex-specific earnings on sex imbalance, Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(3): 1251–1285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2008.123.3.1251

- Raftakis, M. 2019. Mortality change in Hermoupolis, Greece (1859–1940). Unpublished PhD dissertation, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne.

- Rodd, R. 1892. The Customs and Lore of Modern Greece. London: D. Stott.

- Ruggles, S., S. Flood, R. Goeken, J. Grover, E. Meyer, J. Pacas, and M. Sobek. 2019. IPUMS USA: Version 9.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS.

- Saloutos, T. 1956. They Remember America: The Story of the Repatriated Greek-Americans. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Saloutos, T. 1964. The Greeks in the United States. Cambridge: Harvard UP.

- Sanders, I. T. 1962. Rainbow in the Rock. The People of Rural Greece. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Sant Cassia, P., and C. Bada. 1992. The Making of the Modern Greek Family: Marriage and Exchange in Nineteenth-Century Athens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sen, A. 1990. More than 100 million women are missing, New York Review of Books 37: 61–66.

- Siampos, G. S. 1973. Demographike Ekseliksis tes Neoteras Ellados (1821–1985) [Demographic Evolution of Modern Greece 1821–1985]. Athens: S. Tzanettis Press.

- Sng, T., and S. Zhong. 2018. Historical violence and China’s missing women. Available: https://economics.smu.edu.sg/sites/economics.smu.edu.sg/files/economics/pdf/Seminar/2018/20181109.pdf (accessed: 21 February 2021).

- Stéphanos, C. 1884. Grèce, géographie médicale, in A. Dechambre (ed.), Dictionnaire Encyclopédique des Sciences Médicales, Vol. 2, Series 4. Paris: Masson and Asselin et Gie.

- Stewart, C. 2016. Demons and the Devil: Moral Imagination in Modern Greek Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Stott, M. A. 1973. Economic transition and the family in Mykonos, Greek Review of Social Research 17: 122–133.

- Strong, F. 1842. Greece as a Kingdom. A Statistical Description of That Country. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- Surridge, B. J. 1930. Survey of Rural Life in Cyprus. Nicosia: Government Printing Office.

- Tabutin, D. 1978. La surmortalité féminine en Europe avant 1940, Population (French Edition) 33(1): 121–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1531720