?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The interplay between remarriage and fertility is among the most poorly documented subjects in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), despite remarriage being one of the fundamental aspects of marriage dynamics in this region. We use Demographic and Health Survey data from 34 countries in SSA to document the association between remarriage and fertility during the reproductive years and over the fertility transition. The findings show that in 29 countries, remarried women end up having fewer children than women in intact unions, despite attaining similar or higher levels of fertility at early reproductive ages. However, remarriage is found to have a positive effect on fertility in Sierra Leone. The effects of remarriage on fertility diminish as fertility declines, with smaller effects generally observed in countries that are relatively advanced in their fertility transition and larger effects found elsewhere. These findings shed light on the role that remarriage might play in country-level fertility declines.

Introduction

Fertility transition is underway in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). However, the pace of the decline has been slow, and fertility in these countries remains high. These dynamics are key drivers of rapid population growth in SSA. For instance, the world’s population is projected to increase by 1.9 billion between 2020 and 2050, and half of this increase will occur in SSA, even though just 14 per cent of the global population live in this region (United Nations Citation2019a). This rapid population growth is leading to strong demand for social services, especially health and education. It is also associated with a high dependency ratio, which limits the economic development of SSA countries (Eastwood and Lipton Citation2011; Cruz and Ahmed Citation2018).

The evolution of the fertility transition in SSA has led to the emergence of complex and diverse perspectives on its pattern and attributes. Previous research has offered several explanations connected to the proximate determinants of fertility for the slow pace of fertility decline in this region: stable (or slowly increasing) rates of early first marriage and first birth, rising premarital birth rates, and lack of contraceptive access (Ezeh et al. Citation2009; Hertrich Citation2017; Finlay et al. Citation2018). Missing from these elements are divorce and remarriage, despite their being fundamental features of marriage dynamics in this region. For example, in some countries, over half of first marriages end in divorce within the first 20 years (Clark and Brauner-Otto Citation2015), and remarriage following union dissolution is rapid and nearly universal (Locoh and Thiriat Citation1995; Reniers Citation2003).

Divorce reduces a woman’s exposure to pregnancy risk (Davis and Blake Citation1956), whereas remarriage reinstates that risk and may provide additional motivations for childbearing with a new partner (Griffith et al. Citation1985). In low-fertility settings, divorce is associated with reduced fertility, and remarriage does not quite compensate for lost fertility (Beaujouan and Solaz Citation2008; Meggiolaro and Ongaro Citation2010; Thomson et al. Citation2012). Similar results have been found in two contexts in SSA: Cameroon (Lee and Pol Citation1988) and, more recently, Ghana (Elleamoh and Dake Citation2019). While these studies offer essential insights regarding the link between remarriage and fertility in SSA, the patterns there might differ in nature and strength from those prevailing in other countries. Thus, whether the contribution of divorce and remarriage to fertility is positive or negative in contexts characterized by early childbearing and high fertility remains unclear. In addition, many other aspects of this relationship have been under-researched or overlooked. There are questions about how the fertility differential between women who remarry and those who remain in their first marriage evolves during the reproductive years and over the fertility transition. At the population level, this link could be related to the stage of fertility transition. Early curtailment of childbearing, lengthening birth intervals, and weakening cultural norms as the fertility transition unfolds (Caldwell Citation1976; Moultrie et al. Citation2012; Towriss Citation2014; Timæus and Moultrie Citation2020) could lead to an attenuation or reversal of this relationship. To the best of our knowledge, this possibility has not been clearly rationalized in the literature, nor empirically tested.

In this paper, we seek to address both of these research gaps by extending the investigation of the effect of remarriage on childbearing to 34 countries in SSA and assessing the trends in fertility differences between remarried women and women who remain in first intact unions over time. We rely on fertility reports from women aged 40–49, collected between 1986 and 2019 through the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) programme in 34 countries, to address two specific questions: (1) How does the cumulative fertility of remarried women and women in intact first marriages compare as they advance in age and at the end of the reproductive lifespan? and (2) Does the relationship between remarriage and fertility depend on the stage of fertility transition? The DHS does not collect detailed marriage histories, so no information is available on the date or age at which a union is dissolved or when a new partnership is formed. Therefore, we intend to answer these questions by using a novel demographic technique that adopts an approach for estimating cohort–period fertility rates (Moultrie et al. Citation2013) and applying Poisson and fixed-effects regression methods.

Background

Fertility and marriage dynamics in sub-Saharan Africa

Fertility, though declining, remains high in SSA. The fertility decline did not begin until after 1980 in several countries (United Nations Citation2019a). During 1950–55, total fertility varied around 6.5 children per woman on average; it was highest in Rwanda, at 8.0 children per woman, and lowest in Gabon, at 5.0 children per woman (mostly due to sterility in the region, rather than due to family-control policies). After these countries gained independence in the 1960s, fertility increased further. On average, total fertility was 6.8 children per woman during the 1975–80 period. Since then, total fertility in SSA has dropped to 4.7 over a 40-year period. However, substantial variation persists between countries. For example, during 2015–20, total fertility varied between 2.4 in South Africa and 7.0 in Niger, with only six of the 34 countries reporting total fertility of less than 4.0, and 27 countries reporting between 4.0 and 5.0.

Fertility changes in SSA are strongly linked to the institution of marriage, primarily because childbearing within marriage is portrayed as the ideal. In most SSA countries, mean age at first marriage is below 20 years (United Nations Citation2019b). However, it has increased over the past three decades (Garenne Citation2004; Shapiro and Gebreselassie Citation2014), a development that was critical for the onset of the fertility decline in this region (Harwood-Lejeune Citation2001; Hertrich Citation2017). For instance, Harwood-Lejeune (Citation2001) found that rising age at first marriage accounted for 16–33 per cent of the fertility decline observed in Southern and East Africa between 1976 and 1998.

The institution of marriage in SSA is also volatile, as union dissolution and remarriage are common. Several studies have documented these dynamics in different parts of SSA. For example, Grant and Soler-Hampejsek (Citation2014) examined marriage outcomes among young women in two districts of Malawi and found that only 58 per cent of first marriages remained intact by the fifth year of marriage. Similarly, Tilson and Larsen (Citation2000) observed that only 60 per cent of Ethiopian first marriages persisted after 20 years. Finally, Clark and Brauner-Otto (Citation2015) presented a thorough and broad investigation of divorce (and widowhood) in 33 countries in SSA, observing that 25 per cent of first marriages ended in divorce after 15–19 years. These studies have also reported that most women who divorce enter a new relationship very quickly. For example, De Walque and Kline (Citation2012) found that in nine out of 13 SSA countries studied, the proportion of currently married women who were remarried was above 15 per cent, with the highest proportions found in Ethiopia (24.0 per cent), Cameroon (23.6 per cent), and Malawi (23.3 per cent). Of the few studies that have assessed remarriage rates, Locoh and Thiriat (Citation1995) found that more than 67 per cent of women in Togo remarried within three years after their divorce/separation. Similarly, Reniers (Citation2003) reported that after a divorce, 40 per cent of women in three rural areas in Malawi had remarried within two years, 70 per cent within five years, and 90 per cent within ten years.

How remarriage affects fertility: A theoretical and empirical appraisal

A theoretical appraisal of the relationship between remarriage and fertility can help us better understand the fertility disparity between remarried women and women in intact first unions. While we can trace this relationship to Davis and Blake’s (Citation1956) framework of proximate determinants, Cohen and Sweet (Citation1974) provided one of the pioneering works that specifically links remarriage and childbearing. Based on this study and the literature accumulated over recent decades, fertility differentials between women in intact first unions and their remarried counterparts appear to arise from differences in three components: (1) timing of union dissolution and remarriage (age at dissolution; gap between dissolution and remarriage); (2) childbearing motivations and behaviour in second- or higher-order unions; and (3) selection for divorce, remarriage, and high fertility.

The timing of union dissolution and remarriage is an essential mechanism in the whole framework for understanding fertility differentials between remarried women and those in intact first unions, mainly because age constrains human reproduction. We can consider two pathways through which this timing influences the ability of remarried women to have as many children as women in intact first unions. First, marital dissolution shifts childbearing to older ages (Van Bavel et al. Citation2012), where fecundity is lower. Thus, union dissolution at earlier childbearing ages allows women to initiate new partnerships at ages where fecundity is still relatively high, thereby increasing the odds that a remarried woman will have as many children as one in an intact union (Thomson et al. Citation2012). However, Wineberg (Citation1990) illustrated that delaying union dissolution does not necessarily result in low fertility, because women who experience union dissolution at an advanced age may have already attained a high level of lifetime fertility before the dissolution (or remarriage). As we highlight later in this section, this argument is more likely to hold in a low-fertility context than in a high-fertility setting such as SSA. Second, union dissolution removes a woman from a socially sanctioned childbearing institution, thus reducing her exposure to regular sexual intercourse and lowering her risk of pregnancy (Davis and Blake Citation1956). Therefore, the timing of remarriage—that is, how quickly a woman remarries following union dissolution—influences her overall fertility by directly modulating her loss of exposure to conception.

Nevertheless, the degree to which the length of time between two successive marriages affects fertility is contingent on prevailing social and religious norms. In societies where women strictly follow traditional customs that disapprove of non-marital childbearing, this effect is likely to be stronger than in communities where non-marital childbearing is considered acceptable (Cohen and Sweet Citation1974). In the latter, the effect may be offset because there may be little or no loss of reproductive years due to union dissolution.

The second argument that helps us understand the link between remarriage and fertility is related to childbearing motivation and behaviour in second- or higher-order unions. At least three key motivations directly influence childbearing behaviour in such unions. First, the ‘parenthood effect’ hypothesis suggests that individuals who remain childless in their first marriage are more inclined to engage in childbearing following remarriage to attain parenthood status (Wineberg Citation1990; Lillard and Waite Citation1993; Jefferies et al. Citation2000; Beaujouan and Solaz Citation2008). Beaujouan and Solaz (Citation2008) demonstrated this proposition in France, noting that childless women were 2.15 times more likely to give birth following remarriage than women who had started childbearing in their first union. Second, remarried women may initiate childbearing to strengthen the marriage bond (Griffith et al. Citation1985), which is commonly referred to as the ‘commitment effect’. Third, women in a second union may resume childbearing to attain their desired family size (Thornton Citation1978), mostly in cases in which the first marriage dissolved before achieving this.

Finally, a selection process may explain the differential fertility between remarried women and those in intact first marriages. At first union onset, some women are selected for demographic and socio-economic characteristics that simultaneously influence their risks of union disruption and childbearing (Cohen and Sweet Citation1974; Lillard and Waite Citation1993; Leone and Hinde Citation2007; Coppola and Di Cesare Citation2008). For instance, in Italy, Coppola and Di Cesare (Citation2008) simultaneously modelled union disruption and childbearing processes, and found that women with a high risk of childbearing also showed a lower probability of union dissolution. They argued that women who desire larger families are disproportionately self-selected for high fertility and stable unions. This finding is comparable to the results reported by Lillard and Waite (Citation1993). They found a significant negative correlation between the unobserved heterogeneity of union dissolution and fertility, which suggests that women with a low likelihood of union dissolution also experience a higher risk of childbearing.

At the population level, the remarriage–fertility link could be related to the fertility transition stage. This mechanism has not been well rationalized in the literature, nor empirically assessed. Downing and Yaukey (Citation1979) explained this trend (albeit without empirically assessing change over time) based on the premise of the early curtailment of childbearing, a common feature associated with low-fertility regimes (Timæus and Moultrie Citation2020). Downing and Yaukey (Citation1979) argued that in low-fertility countries, remarried women are likely to have achieved their desired family size at the time of union dissolution; thus, childbearing in higher-order unions could generate excess fertility. Closely related to this idea, and more relevant to the SSA context, is the concept of extended birth intervals. Longer birth intervals among women in intact first unions could correspond equally to the average time spent outside marriage among women who later remarry. The fertility transition also brings changes in social norms regarding family configuration and childbearing (Caldwell Citation1976) that could influence the remarriage–fertility relationship. Caldwell (Citation1976) noted that as countries modernize, extended family kin networks tend to weaken and become less influential in couples’ reproductive decisions. Modernization is also likely to be accompanied by the fading of cultural norms that confine childbearing to within marriage. In such contexts, childbearing could be equally likely to occur during periods between union dissolution and remarriage, leading to a weakening or reversal of the remarriage–fertility relationship.

Recent studies, conducted mostly in Europe, have shed light on this relationship. For France, Beaujouan and Solaz (Citation2008) found that women aged 45–60 achieved a completed family size (CFS) of 2.25 births, on average, if they remained in an intact union, 2.17 births if they remarried, or 2.02 births if they remained separated. In Italy, Meggiolaro and Ongaro (Citation2010) found that when current age was controlled, the fertility of women who married only once was 15 per cent higher than among remarried women. Van Bavel et al. (Citation2012) investigated the effect of remarriage on childbearing across 24 European countries, finding that remarried European women aged 20–50 had 0.02 fewer children than their counterparts in intact first unions. Finally, a study in Bangladesh found support for the same pattern, albeit while showing a more substantial effect: a difference in CFS of 1.1 children between remarried women and those in intact first unions, with the remarried having 3.9 children on average (Uddin and Hosain Citation2013). However, in an earlier study on West Malaysia, Palmore and bin Marzuki (Citation1969) observed a negative effect of remarriage on fertility.

The studies by Lee and Pol (Citation1988) and Elleamoh and Dake (Citation2019) are the only ones that have attempted to investigate this question in SSA. Using data from the 1978 Cameroon World Fertility Survey, Lee and Pol (Citation1988) found that remarried women had fewer children than women in intact first unions. Specifically, they showed that the mean number of children ever born (CEB) to women was 3.48 for those in a stable union, 3.34 for those who married twice, 2.67 for those who married three times, and 1.83 for those who married four or five times. Elleamoh and Dake (Citation2019) reached a similar conclusion in Ghana using 2014 DHS data: mean CEB was lower among remarried women aged 15–49. Our paper extends this literature and considers two new dimensions of this relationship: the age and period patterns.

The sub-Saharan African context and research hypotheses

SSA is a generally high-fertility region characterized by large-family-size ideals (Bongaarts and Casterline Citation2013). It has a history of early marriage (Shapiro and Gebreselassie Citation2014; Hertrich Citation2017), and remarriage following union dissolution is usually rapid (Locoh and Thiriat Citation1995; Reniers Citation2003). In some countries with a high prevalence of HIV, women use divorce to mitigate exposure to the risk of HIV/AIDS (Reniers Citation2008; Grant and Soler-Hampejsek Citation2014). In such cases, remarriage may be regarded as a pathway to accomplish the ‘unfinished agenda of childbearing’ within marriage. Non-marital childbearing is rising in some countries (Clark et al. Citation2017); nevertheless, norms that condemn such childbearing still dominate in SSA. For example, Palamuleni and Adebowale (Citation2014) noted that the children of women who give birth outside marriage are called names, such as ‘children without fathers’ or ‘children of the bush’. These norms most likely influence women with disrupted unions to avoid childbearing despite the desire to have children. The fertility transition is at different stages in different SSA countries: in some it is still in its beginning stages, while in others, it has reached middle to advanced stages. In this region, fertility decline tends to be characterized by a lengthening of birth intervals (Moultrie et al. Citation2012; Towriss Citation2014).

These dynamics lead us to propose three specifics hypotheses about the relationship between remarriage and fertility, and how it changes during the reproductive years and over the fertility transition. First, it is likely that loss of exposure to regular sexual intercourse is minimized due to rapid remarriage. However, because childbearing within marriage is still portrayed as the ideal, the time spent outside a union following dissolution is likely to be reflected in the average fertility distributions of remarried women. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is that remarried women are likely to have given birth to fewer children, on average, at the end of their childbearing years than their counterparts in intact first marriages. Second, first marriages that dissolve are likely to do so before women have attained their desired family size. Thus, the desire to have children in second- or higher-order unions is likely to be dominant. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is that ever-remarried women in SSA are more likely than women in intact first unions to have more children at late reproductive ages, as they attempt to catch up on lost fertility to fulfil their family-size goals. Finally, as fertility declines, the lengthening of birth intervals is likely to compensate for loss of exposure due to union dissolution. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is that as the fertility transition unfolds in SSA, the fertility gap between remarried women and women in intact first unions will diminish and could become negative. Existing DHS data, which span over 15 years in some countries, present an opportunity to test these hypotheses and provide a broader perspective on this relationship.

Data and methods

Data

We use data from DHSs conducted in 34 SSA countries between 1986 and 2019. In total, 139 surveys were carried out during this period, with multiple surveys available in 32 countries. We include 137 surveys in our analysis (Appendix 1, supplementary material), and exclude the Mali 1987 and Senegal 1997 surveys because they lack critical information for identifying remarried women.

The DHSs are a series of nationally representative studies that collect fertility, nuptiality, and socio-economic information from women aged 15–49. The routinely collected nuptiality data include age at first marriage, current marital status, and number of unions a woman has ever formed. The definition of marriage in the DHS data is flexible, classifying women in both formal and informal unions as married. This specification is desirable because it addresses the challenge of identifying legitimately married women in regions where union formation is a process rather than an event (Meekers Citation1992; Chae Citation2016). We follow the same practice and identify ever-married women as those who report having ever been married or having ever lived with a man at least once. Similarly, we define ever-remarried women as those who have ever married or lived with a man more than once. On fertility, the DHS collects two forms of data: summary birth histories (reports of lifetime fertility that provide the aggregate CEB) and full birth histories (comprehensive fertility reports that specify, among other aspects, the date of birth for each child). We rely on full birth histories for the calculation of fertility measures in our analyses.

Our goal is to examine the fertility differences between ever-remarried women and women in intact first unions during their reproductive years and over the fertility transition. Thus, we focus our analysis on women who are towards the end of their childbearing lifespan. The conventional approach is to consider women aged 45–49, since their cumulative fertility is regarded as a measure of CFS. However, we extend this age bracket to include all women aged 40–49, to achieve a reasonable sample size for each country and survey.

Methods

We combine statistical and demographic methods to analyse fertility differentials among remarried women (those who have ever married or ever lived with a man more than once) relative to women in intact first unions (those in their first union who have never experienced a dissolution). Our measure of fertility is mean CEB.

To respond to our first question of how the cumulative fertility of remarried women and women in intact first unions differs over the reproductive years, we compare the lifetime fertility attained by the two groups at successive childbearing ages. We adopt a technique for estimating cohort–period fertility rates to perform this investigation (Moultrie et al. Citation2013). Cohort–period fertility rates are derived from the distribution of births by age of mother and period before the survey, and the distribution of women by age at the survey date. Appendix 2 in the supplementary material shows the matrix for calculating cohort–period fertility rates, where represents the number of women aged

to x + n at the survey date, and

denotes the total number of births j years before the survey to women aged x to x + n. In this case, cohort–period fertility rates are defined as:

(1)

(1) If we consider an individual woman

, and single-year intervals

, equation (1) reduces to

and represents the number of births to a woman

aged

at

years before the survey. This expression equally corresponds to the number of live births woman

aged

had when aged

. We can denote this function as

. Thus, for a specific woman i aged

at survey, we can estimate her cumulative fertility as she turned exact age

as:

(2)

(2) where

= age at firsbirth. In this study, we consider the cumulative fertility of women aged 40–49 at successive childbearing ages (i.e. at different values of

). We focus our analysis on fertility attained before or at age 40 (

), since the birth histories of some women in our sample are right-censored after age 40. To calculate the total number of children ever born to women aged 40–49 at specific age

, denoted as

, we first use full birth histories to derive cumulative fertility at age

for every individual woman in the sample

. We then obtain

by aggregating the fertility attained by each woman at exact age ω. This calculation can be expressed as:

(3)

(3) where

= total number of women aged

. We divide F

by the total number of women aged 40–49 to determine the mean CEB for women aged 40–49 at exact age ω. We calculate this estimate separately for women in intact first unions and remarried women. Our fertility comparison index between these two groups is the ‘net fertility difference’, calculated by subtracting the mean CEB for remarried women from the mean CEB for women in intact first unions.

However, some observable socio-demographic characteristics of remarried women differ from those of women in intact first unions (Appendix 3, supplementary material). On average, remarried women are older, start childbearing sooner, and marry at a younger age than women in intact first unions, and their premarital fertility is higher. Furthermore, the proportions of remarried women who are secondary or higher educated or who live in an urban area are lower than for women in intact first unions. Therefore, we use Poisson regression models to account for the fertility gap between these two groups due to variation in age, age at first marriage, age at first birth, premarital fertility, education, and area of residence. Our main outcome is the number of children ever born by a specific age ω, . We fit a series of Poisson regression models for each country and survey year corresponding to different maternal ages. Therefore, our model is specified as:

(4)

(4) where

= 15, 16, 17, … , 40;

is the expected number of children born to woman

when turning exact age

;

represent covariates (remarriage status, age, age at first marriage, age at first birth, premarital fertility, education, and area of residence) associated with woman

; and

are the corresponding regression coefficients. We obtain the equivalent estimate of observed net fertility difference at exact age ω by deriving marginal effects from the model. The contrast of the derived margins returns the expected difference in number of children ever born to a woman in an intact first union if she had ever remarried, while fixing her observed socio-demographic characteristics.

To assess the association between remarriage and fertility change throughout the fertility transition, we first examine trends over time in net fertility difference at age 40. Therefore, this part of the analysis is restricted to the 32 countries with at least two surveys (Angola and Gambia excluded). Our outcome measure is the change in net fertility difference between ever-remarried women and women in intact first marriages from the earliest to the most recent survey in each country. We divide the total change by the years between the two surveys to estimate the average annual change.

The analysis of the change in net fertility difference broadly shows whether the fertility gap between remarried women and those in intact first unions is shrinking or widening over time. However, it does not explicitly indicate how the gap is associated with the level of fertility. Therefore, we use a fixed-effects regression analysis to investigate this relationship. Fixed-effects models are used to estimate the effect of a predictor on an outcome using panel data. They control for unobservable time-invariant covariates between clusters. We construct a panel data set using all 135 surveys from the 32 countries included in this analysis. Countries constitute the panels, and survey years represent periods of observation. The dependent variable is the observed net fertility difference at exact age 40, , while the main explanatory variable is the corresponding cumulative fertility

. Therefore, our model is specified as:

(5)

(5) where

represents a country,

represents a survey period,

is the country-specific intercept, and

is the error term.

Results

Levels and trends in remarriage in sub-Saharan Africa

displays the percentage of ever-remarried women among ever-married women aged 40–49 in 34 SSA countries at two survey time points. Based on the most recent surveys, on average 23.2 per cent of women in SSA have married more than once (not shown). The highest percentage of remarried women is observed in Liberia (41.5 per cent) and the lowest in Lesotho (3.7 per cent). The proportion of ever-remarried women is also high in Comoros, Congo, Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Madagascar, and Malawi, where at least 30 per cent of women have married more than once. It is below 10 per cent only in Kenya, South Africa, and Lesotho. The prevalence of remarried women has declined in all countries except Congo, Congo (DRC), Lesotho, and Zimbabwe, where it marginally increased.

Table 1 Percentage of ever-remarried women among ever-married women aged 40–49 in 34 sub-Saharan African countries

Children ever born at the end of childbearing years

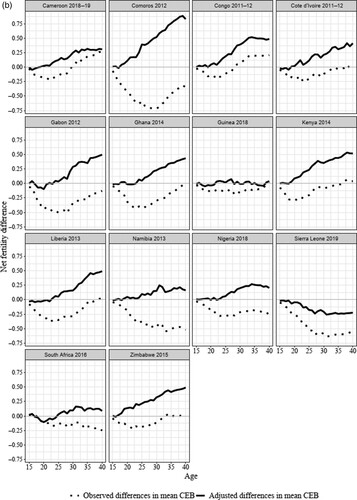

shows the observed mean CEB for women in intact first unions and ever-remarried women as they turn age 40 (equivalent estimates at ages 15, 20, 25, 30 and 35 are shown in supplemental Table 1, supplementary material). It also displays the corresponding fertility differences between these two groups.

Figure 1 Observed mean number of children ever born by age 40 among women aged 40–49, by remarriage status, in 34 sub-Saharan African countries.

Note: Net fertility differences (mean CEB for women in intact first unions minus mean CEB for ever-remarried women) are presented with 95 per cent confidence intervals. A negative difference indicates that cumulative fertility is higher among remarried women.

Source: Most recent DHS data available for each country.

The results show that in most countries, fertility is high both for women in intact first unions and remarried women. The mean CEB for those in intact first marriages varies between 2.91 in South Africa and 7.82 in Niger, and for ever-remarried women from 3.02 in Lesotho to 6.77 in Niger. In 23 of the 34 countries, the average woman has given birth to at least five children by age 40, irrespective of whether she remains in a first union or has remarried. The only countries where mean CEB at age 40 is less than five children both for remarried women and those in intact first unions are Ghana, Guinea, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. The fertility gap between these two groups ranges from −0.56 in Sierra Leone to 1.25 in Chad (with mean = 0.47; standard deviation = 0.33).

Remarriage and fertility over the reproductive years

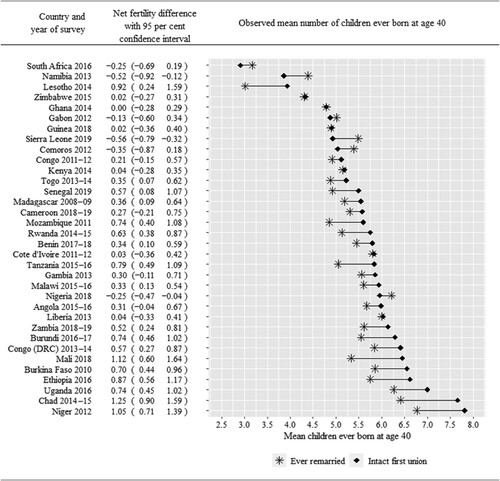

displays the pattern of net fertility differences between remarried women and women in intact first unions by age during the reproductive years. It shows observed differences (dotted lines) and fertility differentials adjusted for age, age at first marriage, age at first birth, premarital fertility, education, and area of residence (solid lines). In panel (a) we show countries where the observed net fertility difference falls above zero at most reproductive ages, and the remaining countries are presented in panel (b). The gap between the observed and adjusted net fertility differences reflects the importance of the socio-demographic characteristics included in our analysis in shaping the fertility differential between remarried women and those in intact first unions: the larger the gap, the greater the influence of these variables (i.e. the greater the differences in the socio-demographic profiles of the two groups). The results () show enormous disparities between the observed and adjusted net fertility differences in 31 of the 34 countries (only slight differences are found in Benin, Mozambique, and Uganda). The observed net fertility difference falls substantially below the adjusted estimates at each age in all countries except Burkina Faso, Chad, Lesotho, Mali, Mozambique, and Niger. This pattern signifies that in most countries, remarried women tend to have attributes that select them for high fertility. This dynamic is quite striking when we consider Comoros, Gabon, Ghana, Liberia, Namibia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and South Africa. In these countries, the observed net fertility difference falls below zero throughout the reproductive years, denoting a positive link between remarriage and fertility. However, this pattern fades in all countries except Sierra Leone when we account for socio-demographic characteristics.

Figure 2 Observed and adjusted net fertility differences among women aged 40–49, by remarriage status and age, in 34 sub-Saharan African countries: (a) countries where observed net fertility difference falls above zero at most ages; and (b) remaining countries.

Note: Net fertility difference = mean CEB for women in intact first unions minus mean CEB for ever-remarried women. A negative net fertility difference indicates that cumulative fertility is higher among remarried women at that age.

Source: As for .

We focus on the adjusted net fertility difference to illustrate how the relationship between remarriage and cumulative fertility evolves during the reproductive years. At ages below 20, cumulative fertility does not differ significantly by remarriage status in 28 countries (). Remarriage is notably associated with higher cumulative fertility at age 20 in South Africa, where ever-remarried women have 22.1 per cent more births during their adolescent years than women in intact first unions. In contrast, it is associated with lower fertility in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, and Zimbabwe, where remarried women have 9.3–18.7 per cent fewer births on average than women in intact first unions as they turn age 20.

Table 2 Differentials in adjusted fertility increments (mean CEB) between women in intact first unions and ever-remarried women aged 40–49, over three broad reproductive age ranges, in 34 sub-Saharan African countries

Except in Guinea and Sierra Leone, net fertility difference is generally more pronounced after age 20. Cumulative fertility is lower among remarried women up to the end of childbearing. In most countries, the rise in net fertility difference with age is very steep, and, in some cases, lasts until the late-30s. For example, in Rwanda, the fertility difference at age 20 is 0.03, increasing to 0.61 at age 30 and reaching 1.06 by age 40. A similar trend is apparent in several countries, including Burundi, Chad, Congo (DRC), Comoros, Ethiopia, and Tanzania. The sharp upward slope in net fertility difference in these countries indicates that the fertility of women who remarry slows down markedly during the middle reproductive ages. Indeed, we find that the fertility increments between ages 20 and 35 are significantly smaller among remarried women in all countries except Guinea, Namibia, Sierra Leone and South Africa (). For example, a Senegalese woman whose first union remains intact is likely to produce 0.65 more births between age 20 and 35 than her counterpart who eventually remarries.

At advanced reproductive ages (35–40), net fertility difference levels off in 19 countries, most notably in Cameroon, Congo, Gambia, Namibia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and South Africa (). This pattern implies that remarried women and those in intact first unions produce similar numbers of births during these later reproductive years. Indeed, we find that the fertility increments beyond age 35 do not differ significantly between remarried women and women in intact first unions in these countries (). However, in 15 countries, net fertility difference continues to increase significantly, with large differences in fertility increments found in Burundi, Chad, Ethiopia, Niger, and Uganda. These are all countries with very high fertility (i.e. with a CFS among ever-married women aged 40–49 varying from 6.40 in Burundi to 7.95 in Niger).

Across all 34 countries, none show a significant drop in net fertility difference during the late reproductive ages. This suggests that remarried women do not significantly close the fertility gap as they approach the end of their childbearing lifespan. At first, we attributed this pattern to our failure to examine fertility differentials at the very oldest reproductive ages because of truncated birth histories. We assumed that and the estimates in underestimated the extent to which remarried women close the fertility gap. Therefore, we performed two robustness checks to assess how net fertility difference evolves during the late reproductive years. First, we used fertility reports from women aged 45–49 in each country to examine differentials in fertility increments between ages 35 and 45 and between ages 40 and 45. Although this analysis was based on smaller sample sizes, the results (Appendix 4, supplementary material) are parallel to those displayed in , and the fertility gap levels off in more (23) countries. Second, we assessed the net fertility difference pattern using a pooled sample of women aged 49 from all recent surveys (N = 4,842). We found that net fertility difference levels off at around 0.51 after age 39 (Appendix 5, supplementary material). These findings contradict the assumption that remarried women are likely to have more children than women in intact first unions towards the end of their reproductive ages, to close the fertility gap.

Sierra Leone presents a unique case. There, remarriage is shown to be associated with higher cumulative fertility throughout the reproductive lifespan (). We found comparable patterns in earlier surveys (2008 and 2013). Thus, the relationship between remarriage and fertility in Sierra Leone appears to be distinct from that seen elsewhere in SSA. We conducted a robustness check to test whether the pattern observed in Sierra Leone and the other countries persisted if we replaced CEB with surviving children in the models (Appendix 6, supplementary material). The results show comparable but not identical patterns in several countries. In most countries, the line showing net fertility difference based on surviving children lies above that based on CEB. In Sierra Leone, it falls above zero at advanced reproductive years, thus indicating a potential reversal of the link between remarriage and fertility when surviving children are considered instead of CEB here. At minimum, this pattern reflects inequalities in child mortality between the two groups (i.e. it indicates that children born to remarried women experience higher mortality than children born to women in intact first unions). We also found that net fertility difference based on either surviving children or CEB becomes more pronounced during the middle and late reproductive years. For example, in Angola, Burundi, Kenya, Lesotho Madagascar, and Malawi, the two shapes are indistinguishable until age 25. Thus, it appears that the mechanism that produces these disparities is somehow linked to remarriage itself.

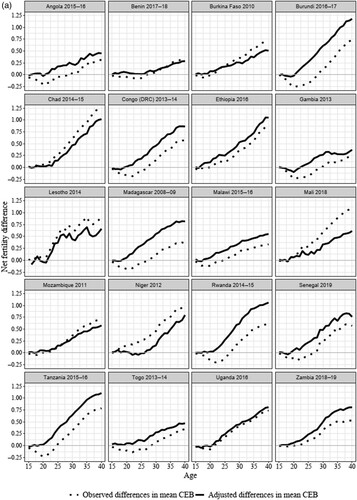

shows country disparities in adjusted net fertility differences at age 40, based on CEB and also on surviving children. Based on CEB, the fertility of ever-remarried women is significantly lower than for women who remain in a first union in 29 countries. The largest fertility gap is found in Burundi, where a woman who eventually remarries is likely to have 1.18 fewer children by age 40. In Sierra Leone, where remarriage is associated with higher fertility, a remarried woman has, on average, 0.21 more births than a woman whose first union remains intact. When we instead consider surviving children, we find that remarriage is significantly associated with having fewer children in 31 countries: using this measure, Chad shows the highest net fertility difference, estimated at 1.41, while South Africa’s is the lowest at 0.10.

Figure 3 Adjusted net fertility differences at age 40 among women aged 40–49, based on mean children ever born and on mean surviving children, in 34 sub-Saharan African countries

1Fertility of ever-married women excludes fertility of women who married once but experienced a union dissolution.

Notes: Net fertility difference = mean CEB or surviving children for women in intact first unions minus mean CEB or surviving children for ever-remarried women. A negative net fertility difference indicates that cumulative fertility is higher among remarried women.

Source: As for .

We were unable to adjust consistently for HIV in the models that produced results shown in and due to limited availability of HIV data. HIV is an important factor that potentially selects women for union dissolution (Porter et al. Citation2004; Anglewicz and Reniers Citation2014) and reduces their fertility outcomes (Zaba and Gregson Citation1998; Terceira et al. Citation2003; Lewis et al. Citation2004). Therefore, we used a pooled data set (N = 21,127) of the most recent surveys from 23 countries for which HIV data are available to investigate the potential bias introduced in our findings when HIV is omitted from the models (Appendix 7, supplementary material). The results reveal that HIV prevalence is indeed higher among remarried women (12.0 per cent on average) than among their counterparts in intact first unions (5.1 per cent). Nevertheless, we do not reach a different conclusion when HIV is considered in the model, although the magnitude of net fertility difference drops slightly. More related to HIV is the issue of infecundity selectivity. The observed fertility difference at older ages could be overstated if infecundity rose more quickly with age among remarried women than among women in intact first unions. An assessment of this issue indicated that the age patterns of infecundity between these two groups are nearly identical in most countries (see Appendix 8(a), supplementary material, for the definition of our measure of infecundity). The levels notably differ at older ages in Angola, Cameroon, and Namibia (Appendix 8(a)). Nonetheless, even in these three countries, the age pattern of net fertility difference presented in this paper does not differ substantially from the pattern we observed when the analyses were restricted to ever-married women who had not been declared infecund (Appendix 8(b), supplementary material).

Remarriage and fertility during the fertility transition

also provides a glimpse of the inherent association between net fertility difference and the fertility level (we focus this analysis on CEB, as it is more robust to temporal mortality variation). Net fertility difference is generally larger in countries with high fertility and smaller elsewhere. For example, in countries where mean CEB at age 40 is below five children (Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe), net fertility difference varies between 0.04 and 0.66, with a mean of 0.34. In contrast, it ranges from 0.20 to 1.18, with a mean of 0.75, in countries where mean CEB is at least six children (Burkina Faso, Burundi, Chad, Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and Uganda). Next, we examine this observation further by assessing changes in net fertility difference over time and how it correlates with the fertility level.

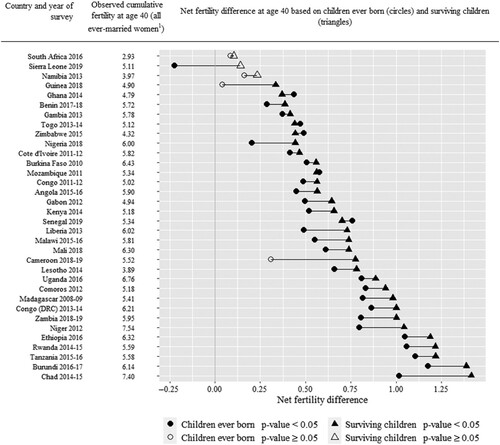

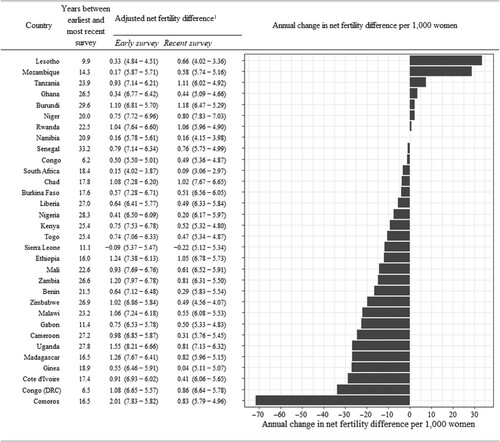

presents the annual change in net fertility difference between the earliest and most recent surveys in countries with multiple surveys. Detailed country-specific fertility trends at age 40 by remarriage status are presented in Appendix 9, supplementary material. The results in and Appendix 9 depict the convergence of fertility trends between remarried women and women in intact first unions. Net fertility difference has declined over the years in 24 countries. The largest absolute decrease (−1.18) is found in Comoros, observed over 16.5 years. Notable increases in net fertility difference can be seen in Lesotho (0.33) and Mozambique (0.41).

Figure 4 Change in net fertility difference at age 40 between the earliest and most recent DHS surveys, women aged 40–49, in 32 sub-Saharan African countries.

1Net fertility difference = mean CEB for women in intact first unions minus mean CEB for ever-remarried women, as shown by the calculation in parentheses. A negative net fertility difference indicates that cumulative fertility is higher among remarried women.

Source: Earliest and most recent DHS data available for each country, 1986–2019.

According to our definition of net fertility difference, we would expect it to remain constant if the fertility of both groups remained stable or changed in parallel. Thus, in countries where women in intact first unions have higher fertility than remarried women, and the fertility of both groups declined, a negative and substantial change in net fertility difference over time would imply that fertility declined more rapidly among women in intact first unions than among remarried women. In contrast, a positive change would suggest a massive fertility decline among remarried women. Thus, the results shown in , taken together with the fertility trends shown in Appendix 9, clearly indicate that the fertility convergence we observed is essentially driven by declining fertility among women in intact first unions. Fertility among remarried women remained steady or increased slightly in Burundi, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Uganda.

presents the results of our fixed-effects models used to estimate the association between net fertility difference and overall fertility. Our dependent variable is net fertility difference at age 40, while the main explanatory variable is mean CEB at age 40 among ever-married women. Model 1 considers this relationship without accounting for any compositional differences. In Model 2, we adjust for differences in age, age at first marriage, age at first birth, premarital fertility, education, and area of residence. We exclude education from Model 2 to produce Model 3 and also exclude area of residence to produce Model 4.

Table 3 Association between net fertility difference and mean children ever born (CEB) at age 40 among ever-married womenTable Footnote1 aged 40–49 (country-level fixed-effects models) in 32 sub-Saharan African countries

Model 1 reveals a strong positive association between net fertility difference and CEB. A one-unit increase in cumulative fertility at age 40 is associated with an increase of 0.45 in the fertility gap between ever-remarried women and women in intact first unions. The predicted net fertility difference from this model drops below zero as mean CEB drops below 5.0. Thus, this finding implies a shifting link between remarriage and fertility from negative to positive as cumulative fertility drops below 5.0 children per woman. Controlling for socio-demographic characteristics (Model 2) erodes the strength of this relationship. Only education is found to be significantly associated with net fertility difference in Model 2. Increasing the percentage of women with secondary or higher education by one percentage point (say, from 15 to 16 per cent) is associated with a reduction of 1.43 in net fertility difference. Therefore, education appears to mediate the association between CEB and the fertility differentials between remarried women and those in intact first unions. This finding becomes even more apparent when we consider Models 3 and 4. A significant association between net fertility difference and cumulative fertility at age 40 resurfaces when education is dropped (Model 3). However, the proportion of women living in an urban area also becomes marginally associated with net fertility difference in Model 3. This is because the percentage of women living in an urban area is likely to be correlated with the proportion of women with secondary education. Dropping area of residence from Model 3 (and thus fully excluding the effect of education) indeed yields a stronger association between net fertility difference and cumulative fertility (Model 4).

Discussion and conclusion

Our aim in this study was to investigate the relationship between remarriage and fertility, and how it changes during the reproductive years and over the fertility transition. We used fertility reports from women aged 40–49, collected through the DHS programme in 34 countries since 1986, to compare the fertility of remarried women with that of women in intact first unions. Our fertility comparison index was net fertility difference, estimated by subtracting the cumulative fertility of ever-remarried women from the corresponding measure for women in intact first unions. Like many other comparative studies that rely on cross-sectional data, such analyses are affected by compositional disparities between comparison groups. In our case, remarried women differed significantly from women in intact first unions in several respects that could produce fertility differences. In most countries, remarried women were older, started childbearing sooner, and married at a younger age, and their premarital fertility was higher compared with women in intact first unions. Furthermore, the proportions of remarried women with secondary or higher education and living in an urban area were generally lower than for women in intact first unions. This profile is typically a catalyst for high fertility. Therefore, we accounted fully for the effects of these factors in our analytical models.

The findings presented in this paper make two key contributions towards our understanding of the role that fertility in remarriage might play in explaining country-level fertility decline. First, our findings provide evidence in support of Hypothesis 1, that remarriage is associated with lower fertility. In most of the countries we studied (29/34), women who remarried ended up having significantly fewer children, despite attaining higher or similar levels of fertility at younger reproductive ages. The small fertility gaps observed during the early reproductive years became wider during the middle reproductive ages and, in most cases, increased until the mid-30s. This pattern signifies that much of the fertility difference towards the end of the reproductive lifespan arose from a significant slowdown in childbearing among remarried women during their prime reproductive years. We can attribute this behaviour to loss of exposure to regular sexual intercourse following union dissolution. However, because remarriage following a union dissolution is generally rapid in SSA (Locoh and Thiriat Citation1995; Reniers Citation2003), and in some countries, non-marital childbearing is rising (Clark et al. Citation2017), it seems implausible that this pattern could arise solely from a slowdown of childbearing due to lack of exposure to regular sexual intercourse. We argue that remarried women in these countries were likely controlling childbearing following remarriage for different reasons. One motivation could be the presence of stepchildren, which may compensate for women’s desire to have their own children (Stewart Citation2002). Remarried women might also delay childbearing in a new partnership as they try to ascertain the level of commitment of their new partners. Indeed, qualitative studies from some parts of Africa have documented lower fertility intentions among remarried women for reasons related to the uncertainty of the current union (Agadjanian Citation2005; Towriss Citation2014). As we discuss in more detail shortly, the latter motivation is likely more dominant in this region than the former.

Our results further indicated that net fertility difference either levelled off or continued rising at advanced reproductive ages. We found that fertility increments after age 34 did not differ significantly between women in intact first unions and remarried women in 19 countries but were significantly higher among women in intact first unions in the remaining 15 countries (generally those with high fertility). Our robustness checks, based on fertility reports from women aged 45–49 in each country, yielded similar results. We also noted a strong levelling off of net fertility differences after age 39 when we considered a pooled sample of women aged 49 from all recent surveys across the 34 countries. Thus, our findings do not support Hypothesis 2, that ever-remarried women are more prone than women in intact first unions to have more children at late reproductive ages, to catch up on lost fertility. The fertility achieved by women in intact first unions at these ages is likely to be similar or significantly higher (especially in a high-fertility context). However, the key implication of this pattern is that, in most countries, women who remarry resume childbearing at some point following remarriage, and probably proceed at the same pace (either intentionally or due to biological constraints) as women in intact first unions. Thus, it appears that the postponement, rather than stopping, of childbearing most likely gave rise to the steep and extended rise in the fertility gap we observed during the middle reproductive ages. Stopping childbearing would have given more weight to the assumption that the presence of stepchildren was the likely principal motivation for fertility restriction following remarriage, while postponement suggests that remarried women were likely delaying childbearing probably in response to uncertainty about the stability of the current union. These dynamics appear to conform with the observation that in this region remarriage is usually associated with child fostering (Grant and Yeatman Citation2014), which potentially reduces the effect of stepchildren on remarried women’s fertility intentions.

The second key contribution of this paper draws from the results of our fixed-effects models and the net fertility difference pattern to document how the remarriage–fertility relationship evolves during the fertility transition, while highlighting potential mechanisms that mediate this link. First, the findings support Hypothesis 3, that the fertility gap between remarried women and women in intact first unions will diminish and could become negative as fertility declines. Like Downing and Yaukey (Citation1979), we found smaller net fertility differences when fertility was low and larger differences in other contexts. For example, in Zambia, net fertility difference at age 40 was 1.20 in 1992, when cumulative fertility among ever-married women aged 40–49 was 7.7. It dropped to 0.81 in 2018 when the corresponding fertility was 6.0. Moreover, the unadjusted fixed-effects regression model revealed a strong association between the level of fertility and net fertility differences. The model implied that the association between remarriage and fertility would shift from negative to positive as cumulative fertility drops below 5.0 children per woman.

This shift is fundamentally driven by the socio-demographic traits of remarried women rather than by behaviour adjustments linked to remarriage or stage of the fertility transition. This observation became clearer when we adjusted for compositional differences in our models. The significant positive association between net fertility difference and fertility level disappeared, and the association between remarriage and fertility at older reproductive ages turned out negative even in countries where observed (unadjusted) fertility was significantly higher among remarried women than women in intact first unions. We interpret these findings to mean that in most countries, the potential causal effect of remarriage on cumulative fertility is likely to remain negative, regardless of the fertility level. However, when fertility is low we would expect to observe more births (on average) among remarried women than women in intact first unions, simply because their socio-demographic characteristics select them for higher fertility. This raises the question of why we observed lower fertility among remarried women in high-fertility contexts, even though remarried women possessed attributes that positioned them for higher fertility. We suggest that the loss of exposure to regular sexual intercourse following union dissolution and the potential postponement of childbearing after remarriage cease to matter as fertility declines. Remarried women could readily match or exceed the fertility of their counterparts in intact first unions because the longer birth intervals or early curtailment of childbearing (Timæus and Moultrie Citation2020) that characterize low-fertility regimes would compensate for the periods of childbearing postponement among remarried women.

Differences in the pace of fertility decline between remarried women and women in intact first unions also appeared to mediate the fertility differential between these two groups. In most countries our findings uncovered evidence of fertility convergence between ever-remarried women and women in intact first unions. We observed that the reduction in net fertility difference was heavily influenced by the larger fertility declines among women in intact first unions. For example, between 1992 and 2015 in Malawi, fertility declined by only 6.9 per cent among remarried women, compared with 17.8 per cent among women in intact first unions. In some countries, including Burundi, Cameroon, Nigeria, and Uganda, fertility slightly increased among remarried women, while declining substantially among women in intact first unions. The slow pace of fertility decline among ever-remarried women can be linked to their low social status. As we have noted, remarried women are more likely to live in rural areas and to be less educated, factors strongly associated with conservative reproductive behaviours (Shapiro Citation2012; Lerch Citation2018).

However, although it was minimized, the convergence of fertility persisted even after we adjusted for socio-demographic characteristics, which implies that other factors influenced this trend. We argue that the higher risk of child mortality among children born to remarried women than to women in intact first unions partly drove this pattern. Our findings revealed a substantial increase in net fertility difference in several countries when we replaced CEB with surviving children in the models. This change reflected substantial child mortality disparities between these two groups. This observation confirms findings from previous studies that showed higher mortality among children born to women who have experienced a union dissolution (Akinyemi et al. Citation2017). Therefore, according to classic demographic theory (Notestein Citation1945), the slow pace of fertility decline among remarried women can be regarded as a response to their child mortality circumstances.

A unique relationship between remarriage and fertility was found in Sierra Leone, where remarried women reported higher cumulative fertility throughout their reproductive years. The socio-demographic profile of remarried women in Sierra Leone was comparable to that of most SSA countries. Thus, we suggest that the observed link was driven by community or cultural factors. Note that Sierra Leone is one of the countries with the highest prevalence of remarried women, estimated at 29.6 per cent in 2019, down from 38.4 per cent in 2008. This could explain why its fertility has declined only slowly. However, further investigations need to be conducted in Sierra Leone to understand its unique pattern.

The findings presented here are of profound importance in shaping our understanding of the role that union dissolution and remarriage play in explaining childbearing dynamics and fertility trends in SSA. First, given the high prevalence of remarriage in this region, the finding that union dissolution and remarriage significantly lower fertility prompts serious concerns about the status of fertility control efforts in these countries. In particular, it raises questions about whether fertility control is much less effective than might be imagined based on current fertility levels. Specifically, we should consider how much of the reduced exposure to sexual intercourse due to union dissolution is not accounted for in models that assume all women are exposed at the same rate throughout their childbearing years. Assessing these issues in future studies could shed more light on the union–fertility nexus in SSA and the underlying fertility control dynamics. Second, our finding of a steep rise in net fertility difference in the early 20s that lasted until the mid-30s reflected a substantial slowdown of childbearing among remarried women during their prime reproductive ages. As we have argued, the postponement of childbearing in higher-order unions is likely critical in shaping this pattern. Thus, the results give more weight to the assumption that the high prevalence of union dissolution and remarriage in SSA could be one of the factors underlying the extended birth intervals (Timæus and Moultrie Citation2020). Finally, we documented that in several countries, the pace of fertility decline was slower among remarried women than their counterparts in intact first unions. Therefore, we argue that the high levels of union dissolution and remarriage observed in some parts of SSA could partly explain their slow pace of fertility decline, particularly during the early stages of the fertility transition when the proportion of remarried women was relatively higher. It could also be argued that the persistently low prevalence of remarriage in countries such as South Africa, Lesotho, Kenya, and Zimbabwe helps to explain why these countries are regarded as precursors of fertility decline in SSA.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (1,008.7 KB)Notes

1 Ben Malinga John is based at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR) and the Department of Population Studies, Chancellor College, University of Malawi. Vissého Adjiwanou is based in the Département de sociologie, Université du Québec à Montréal, and the Département de démographie, Université de Montréal.

2 Please direct all correspondence to Ben Malinga John, Konrad-Zuse-Straße 1, 18057 Rostock, Germany; or by Email: [email protected] or [email protected]

3 We are grateful for the feedback on an earlier version of this paper we received from Natalie Nitsche of MPIDR and Elizabeth Thomson of the University of Stockholm. Their insights helped us tremendously in refining the issues discussed in this paper. Nonetheless, none of them is responsible for how we have decided to use their insights and suggestions.

4 The data used in this paper are openly available at https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

5 Supplemental Table 2 provides incidence rate ratios of mean CEB at age 40 by remarriage status.

References

- Agadjanian, Victor. 2005. Fraught with ambivalence: Reproductive intentions and contraceptive choices in a sub-Saharan fertility transition, Population Research and Policy Review 24(6): 617–645. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-005-5096-8

- Akinyemi, Joshua O., Clifford O. Odimegwu, and Olufunmilayo O. Banjo. 2017. Dynamics of maternal union dissolution and childhood mortality in sub-Saharan Africa, Development Southern Africa 34(6): 752–770. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2017.1351871

- Anglewicz, Philip, and Georges Reniers. 2014. HIV status, gender, and marriage dynamics among adults in rural Malawi, Studies in Family Planning 45(4): 415–428. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00005.x

- Beaujouan, Eva, and Anne Solaz. 2008. Childbearing after separation: Do second unions make up for earlier missing births? Evidence from France. Research Paper, Institut National Etudes Démographiques (Documento de trabajo, 155).

- Bongaarts, John, and John Casterline. 2013. Fertility transition: Is sub-Saharan Africa different?, Population and Development Review 38(Suppl 1): 153–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00557.x

- Caldwell, John C. 1976. Toward a restatement of demographic transition theory, Population and Development Review 2(3/4): 321–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1971615

- Chae, Sophia. 2016. Forgotten marriages? Measuring the reliability of marriage histories, Demographic Research 34(19): 525–562. doi:https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2016.34.19

- Clark, Shelley, and Sarah Brauner-Otto. 2015. Divorce in sub-Saharan Africa: Are unions becoming less stable?, Population and Development Review 41(4): 583–605. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00086.x

- Clark, Shelley, Alissa Koski, and Emily Smith-Greenaway. 2017. Recent trends in premarital fertility across sub-Saharan Africa, Studies in Family Planning 48(1): 3–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12013

- Cohen, Sarah Betsy, and James A. Sweet. 1974. The impact of marital disruption and remarriage on fertility, Journal of Marriage and the Family 36(1): 87–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/350998

- Coppola, Lucia, and Mariachiara Di Cesare. 2008. How fertility and union stability interact in shaping new family patterns in Italy and Spain, Demographic Research 18(4): 117–144. doi:https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.18.4

- Cruz, Marcio, and S. Amer Ahmed. 2018. On the impact of demographic change on economic growth and poverty, World Development 105: 95–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.12.018

- Davis, Kingsley, and Judith Blake. 1956. Social structure and fertility: An analytic framework, Economic Development and Cultural Change 4(3): 211–235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/449714

- De Walque, Damien, and Rachel Kline. 2012. The association between remarriage and HIV infection in 13 sub-Saharan African countries, Studies in Family Planning 43(1): 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00297.x

- Downing, Douglas C., and David Yaukey. 1979. The effects of marital dissolution and remarriage on fertility in urban Latin America, Population Studies 33(3): 537–547. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2173897

- Eastwood, Robert, and Michael Lipton. 2011. Demographic transition in sub-Saharan Africa: How big will the economic dividend be? Population Studies 65(1): 9–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2010.547946

- Elleamoh, Gertrude E., and Fidelia A. A. Dake. 2019. “Cementing” marriages through childbearing in subsequent unions: Insights into fertility differentials among first-time married and remarried women in Ghana, PloS One 14(10): e0222994. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222994

- Ezeh, Alex C., Blessing U. Mberu, and Jacques O. Emina. 2009. Stall in fertility decline in Eastern African countries: Regional analysis of patterns, determinants and implications, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 364(1532): 2991–3007. doi:https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0166

- Finlay, Jocelyn E., Iva’n Mejı´a-Guevara, and Yoko Akachi. 2018. Inequality in total fertility rates and the proximate determinants of fertility in 21 sub-Saharan African countries, PloS One 13(9): e0203344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203344

- Garenne, Michel. 2004. Age at marriage and modernization in sub-Saharan Africa, Southern African Journal of Demography 9(2): 59–79. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20853271

- Grant, Monica J., and Erica Soler-Hampejsek. 2014. HIV risk perceptions, the transition to marriage, and divorce in Southern Malawi, Studies in Family Planning 45(3): 315–337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00394.x

- Grant, Monica J., and Sara Yeatman. 2014. The impact of family transitions on child fostering in rural Malawi, Demography 51(1): 205–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0239-8

- Griffith, Janet D., Helen P. Koo, and Chirayath M. Suchindran. 1985. Childbearing and family in remarriage, Demography 22(1): 73–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2060987

- Harwood-Lejeune, Audrey. 2001. Rising age at marriage and fertility in Southern and Eastern Africa, European Journal of Population/ Revue Europenne de Démographie 17(3): 261–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011845127339

- Hertrich, Véronique. 2017. Trends in age at marriage and the onset of fertility transition in sub-Saharan Africa, Population and Development Review 43(1): 112–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12043

- Jefferies, Julie, Ann Berrington, and Ian Diamond. 2000. Childbearing following marital dissolution in Britain, European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie 16(3): 193–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026529300659

- Lee, Bun Song, and Louis G. Pol. 1988. Effect of marital dissolution on fertility in Cameroon, Social Biology 35(3-4): 293–306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19485565.1988.9988708

- Leone, Tiziana, and Andrew Hinde. 2007. Fertility and union dissolution in Brazil: An example of multi-process modelling using the Demographic and Health Survey calendar data, Demographic Research 17(7): 157–180. doi:https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2007.17.7

- Lerch, Mathias. 2018. Fertility decline in urban and rural areas of developing countries, Population and Development Review 45(2): 301–320. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12220

- Lewis, James J.C., Carine Ronsmansb, Alex Ezehc, and Simon Gregson. 2004. The population impact of HIV on fertility in sub-Saharan Africa, Aids (London, England) 18(suppl 2): S35–S43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-200406002-00005

- Lillard, Lee A., and Linda J. Waite. 1993. A joint model of marital childbearing and marital disruption, Demography 30(4): 653–681. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2061812

- Locoh, Therese, and Marie-Paule Thiriat. 1995. Divorce et remariage des femmes en Afrique de l’Ouest. Le cas du Togo [Divorce and remarriage of women in West Africa. The case of Togo], Population (French edition) 50(1): 61–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1533793

- Meekers, Dominique. 1992. The process of marriage in African societies: A multiple indicator approach, Population and Development Review 18(1): 61–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1971859

- Meggiolaro, Silvia, and Fausta Ongaro. 2010. The implications of marital instability for a woman’s fertility: Empirical evidence from Italy, Demographic Research 23(34): 963–996. doi:https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2010.23.34

- Moultrie, Tom A., Rob E. Dorrington, Allan G. Hill, Kenneth Hill, Ian M. Timæus, and Basia Zaba. 2013. Tools for Demographic Estimation. Paris: International Union for the Scientific Study of Population. http://demographicestimation.iussp.org

- Moultrie, Tom A., Takudzwa S. Sayi, and Ian M. Timæus. 2012. Birth intervals, postponement, and fertility decline in Africa: A new type of transition? Population Studies 66(3): 241–258. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2012.701660

- Notestein, F W. 1945. Population—the long view, in T. W. Schultz (ed.), Food for the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 36–41.

- Palamuleni, Martin E., and Adeyemi S. Adebowale. 2014. Patterns of premarital childbearing among unmarried female youths in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from demographic health survey, Scientific Research and Essays 9(10): 421–430. doi:https://doi.org/10.5897/SRE2013.5529

- Palmore, James A., and Ariffin bin Marzuki. 1969. Marriage patterns and cumulative fertility in West Malaysia: 1966–1967, Demography 6(4): 383–401. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2060084

- Porter, Laura, Lingxin Hao, David Bishai, David Serwadda, Maria J. Wawer, Thomas Lutalo, Ronald Gray, and the Rakai Project Team. 2004. HIV status and union dissolution in sub-Saharan Africa: The case of Rakai, Uganda, Demography 41(3): 465–482. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2004.0025

- Reniers, Georges. 2003. Divorce and remarriage in rural Malawi, Demographic Research (Special Collection 1) 6: 175–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2003.S1.6

- Reniers, Georges. 2008. Marital strategies for regulating exposure to HIV, Demography 45(2): 417–438. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0002

- Shapiro, David. 2012. Women’s education and fertility transition in sub-Saharan Africa, Vienna Yearbook of Population Research 10: 9–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1553/populationyearbook2012s9

- Shapiro, David, and Tesfayi Gebreselassie. 2014. Marriage in sub-Saharan Africa: Trends, determinants, and consequences, Population Research and Policy Review 33(2): 229–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9287-4

- Stewart, Susan D. 2002. The effect of stepchildren on childbearing intentions and births, Demography 39(1): 181–197. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2002.0011

- Terceira, Nicola, Simon Gregson, Basia Zaba, and Peter Mason. 2003. The contribution of HIV to fertility decline in rural Zimbabwe, 1985-2000, Population Studies 57(2): 149–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472032000097074

- Thomson, Elizabeth, Maria Winkler-Dworak, Martin Spielauer, and Alexia Prskawetz. 2012. Union instability as an engine of fertility? A microsimulation model for France, Demography 49(1): 175–195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0085-5

- Thornton, Arland. 1978. Marital dissolution, remarriage, and childbearing, Demography 15(3): 361–380. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2060656

- Tilson, Dana, and Ulla Larsen. 2000. Divorce in Ethiopia: The impact of early marriage and childlessness, Journal of Biosocial Science 32(3): 355–372. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932000003552

- Timæus, Ian M., and Tom A. Moultrie. 2020. Pathways to low fertility: 50 years of limitation, curtailment, and postponement of childbearing, Demography 57(1): 267–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00848-5

- Towriss, Catriona A. 2014. Birth intervals and reproductive intentions in Eastern Africa: Insights from urban fertility transitions. PhD thesis, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. doi:https://doi.org/10.17037/PUBS.01917783.

- Uddin, M Sheikh Giash, and Md Mozaffar Hosain. 2013. Factors affecting marital instability and its impact on fertility in Bangladesh, ASA University Review 7(2): 35–41. http://www.asaub.edu.bd/data/asaubreview/v7n2sl4.pdf.

- United Nations, Population Division. 2019a. World Population Prospects 2019. Available: https://population.un.org/wpp/DataQuery/ (accessed: 1 February 2021).

- United Nations, Population Division. 2019b. World Marriage Data 2019. Available: https://population.un.org/MarriageData/index.html#/maritalStatusData (accessed: 1 February 2021).

- Van Bavel, Jan, Mieke Jansen, and Belinda Wijckmans. 2012. Has divorce become a pro-natal force in Europe at the turn of the 21st century, Population Research and Policy Review 31(5): 751–775. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-012-9237-6

- Wineberg, Howard. 1990. Childbearing after remarriage, Journal of Marriage and the Family 52(1): 31–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/352835

- Zaba, Basia, and Simon Gregson. 1998. Measuring the impact of HIV on fertility in Africa, Aids (London, England) 12(Suppl 1): S41–S50.