Abstract

Child marriage is associated with adverse outcomes related to women’s well-being. Many countries have introduced laws banning this practice, and a number of studies have evaluated their impact. Scant research has focused on instances where countries have lowered the legal minimum age at marriage, even though such ‘reverse policies’ could result in stalled or uneven progress in eradicating child marriage. Using visualization techniques, regression analyses, and multiple robustness checks, we document changes in the prevalence of child marriage in Mali, where in 2011 the general minimum age at marriage of 18 was lowered to 16. Since 2011, the prevalence of child marriage has progressively increased among women with no education and women living in communities characterized by low local development. We reflect on the role that data collection processes may play in explaining some of these findings and stress how repealing existing provisions aiming to protect girls can have adverse consequences on the most vulnerable social strata.

Introduction

Child marriage is widely recognized in international human rights agreements as a harmful and discriminatory global practice. Early unions are known to be associated with a range of adverse effects on the health of women and their children, women’s opportunities in education and paid employment, and within-couple decision-making power dynamics (Raj Citation2010; Delprato et al. Citation2015; Efevbera et al. Citation2017; Yount et al. Citation2018). Consequently, many countries (including several in sub-Saharan Africa) have introduced legislation in the last two decades to increase the legal minimum age at marriage, thus banning child marriage. A growing number of studies have evaluated the effectiveness of these laws, providing mixed and context-specific evidence on whether they are successful at reducing the prevalence of early unions (Collin and Talbot Citation2017; Amirapu et al. Citation2020; Bellés-Obrero and Lombardi Citation2020; Rokicki Citation2020; Batyra and Pesando Citation2021; McGavock Citation2021).

Conversely, scant attention has been paid to instances where countries have lowered the legal minimum age at marriage. It is equally important to evaluate such ‘reverse policies’, to understand better whether repealing existing laws that aim to protect young women could have consequences on the prevalence of child marriage. This paper focuses on the case of Mali, where the general legal minimum age at marriage for women was lowered from 18 to 16 in 2011 when the new Family Code was passed, repealing the existing legal provisions of the 1962 Marriage Code that banned marriage before age 18 (with some exceptions, discussed later). As a result, a new general legal minimum age at marriage of 16 was set. We aim to examine trends in child marriage—defined as marriage before age 18—among women prior to and following the introduction of the 2011 Family Code, to assess whether the prevalence of early marriage in Mali changed after the minimum legal age at marriage was lowered. In so doing, we reflect on potential alternative explanations, including the complexity of collecting reliable data on age among vulnerable populations in (often conflict-affected) resource-deprived societies, as carefully discussed by Randall et al. (Citation2013). A study of this kind is critical for monitoring progress towards eradicating this harmful practice, achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 (which classifies child marriage as a threat to gender equality and calls for its elimination (United Nations Citation2016)), devising more careful data collection practices aimed at minimizing interviewer effects, and combining quantitative records with thorough qualitative insights.

Background

Family life, child marriage, and family law in Mali

Marriage in Mali is almost universal, and the percentage of women who never enter a union during their lifetime is small (Measure DHS Citation2022). Despite the continued widespread nature of marriage, union formation practices have undergone a substantial change in recent decades. Marriages were traditionally planned and managed by family elders and involved the payment of bride wealth (i.e. net assets moving from the groom’s to the bride’s family on marriage); however, they are increasingly resulting from individuals’ own choices or joint negotiations with parents (Hertrich and Lesclingand Citation2012). Despite the downward trend in parental authority over marriage, research conducted among young women in the Sikasso and Ségou regions has suggested that marriages arranged by the family continue to be common (Melnikas et al. Citation2017). A distinct feature of Malian marriage regimes is the high and enduring prevalence of polygynous unions (Whitehouse Citation2023), which goes hand in hand with large age differences between spouses (Lardoux Citation2004) and limited women’s agency, although some recent ethnographic work from the capital, Bamako, has suggested that Malian women are becoming more powerful than publicly stated norms let on (Whitehouse Citation2022). For the majority of women union formation takes place very early, and levels of child marriage in Mali are among the highest in the world. Although the prevalence of early unions has decreased in recent decades, in 2018 more than half of women aged 25–49 had still married before age 18 (Measure DHS Citation2022). Child marriage is most common among vulnerable women (i.e. those living in the poorest households and the least educated), most likely as a route to higher economic security (Whitehouse Citation2016; Flynn et al. Citation2021; Zegeye et al. Citation2021). Heterogeneity in child marriage in Mali is pronounced, not only across socio-economic strata but also across regions. Early unions are concentrated in the south-western parts of Mali, which are mostly rural and feature high poverty rates (Girls Not Brides Citation2021).

The high prevalence of child marriage in Mali has persisted in spite of the blurred legal provisions banning and penalizing the practice that were in place until 2011. According to the Malian 1962 Marriage Code, the general (i.e. without parental consent) legal minimum age at marriage was 18 years (Assemblée Nationale Citation1962). Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind that in a patriarchal society such as Mali, parental consent was widely viewed as a prerequisite of any marriage (customary/religious or civil), leading to an informal understanding that the country’s legal marriage age was 18 for males and 15 for females, with unclear implications for actual marriage practices (Kang Citation2015). In December 2011, the Malian government passed a revised Family Code, which established a new general legal minimum age at marriage whereby women were now not allowed to legally marry before age 16 (Assemblée Nationale Citation2011). Given the failure of this new code to mention parental consent explicitly, this effectively meant that the general minimum age at marriage was lowered by two years, from 18 to 16. It is worth noting that there were exceptions in both the old and new codes that allowed marriage earlier than 18 and 16, respectively, thus creating loopholes. According to the 1962 law, marriage among women was permitted at age 15 with parental consent and even below age 15, but only if the Minister of Justice granted an exemption for serious reasons. According to the 2011 law, there are no exceptions with parental consent, but the code states that the head of the administrative district could grant exemptions from the minimum age at marriage of 16 for serious reasons before the civil judge; nonetheless, this age should not be lower than 15. As such, the new law showcases elements of greater child marriage permissiveness by lowering the general minimum age to 16, yet it is important to note that some aspects are also less permissive: for instance, the removal of the parental consent exception. Both the 1962 Marriage Code and 2011 Family Code specify penalties for breaking the law. Those who approve the marriage of individuals who do not reach the required age are subject to a prison sentence of six months to one year, together with a fine (Assemblée Nationale Citation1962, Citation2011).

A summary of the 1962 and 2011 laws is presented in and is based on data from the Policy-Relevant Observational Studies for Population Health Equity and Responsible Development project (PROSPERED) (Nandi et al. Citation2018). The information simplifies reality to a significant extent and may not fully capture the complexity of family and marriage life across different Malian contexts (for a comprehensive study drawing on extensive ethnographic work, see Whitehouse Citation2023).

Table 1 Details of the legal minimum age at marriage based on the 2011 Family Code and 1962 Marriage Code, Mali

Even though many girls in Mali were already marrying before age 18 in response to various parental pressures (Schaffnit and Lawson Citation2021), the introduction of the 2011 Family Code is publicly considered to be a setback for women’s rights. Various organizations called for action to amend the discriminatory provisions against women that came into effect with the passing of the code (UN Human Rights Council Citation2012). Various sources suggest that the Malian government originally began creating the first draft of the new family law to grant women more rights (e.g. in relation to inheritance and divorce) and promote gender equality (e.g. within marriage). The draft also included an article prohibiting child marriage among women. However, the new law’s text was met with criticism, and its drafting was brought to a halt due to a backlash that resulted in protests and pressure from religious organizations and leaders (Burrill Citation2020; Flynn et al. Citation2021). Flynn et al. (Citation2021) highlighted that religious norms are an important determinant of values and behaviour in Mali. The interpretation of these norms suggests they support practices such as child marriage, which ‘can be seen as a way to preserve girls sexual purity and avoid pregnancies before marriage’ (Flynn et al. Citation2021, p. 3). As a result of this opposition, the final 2011 Family Code excluded many provisions that had been part of the earlier draft, including the legal minimum age at marriage for women of 18 years, which instead was set to 16 years. Mali’s 2011 Family Code is considered by international actors to be a violation of agreements that aim to protect women’s rights, such as the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (the Maputo Protocol) (Burrill Citation2020).

Despite the existing legal provisions, child marriage in Mali persists at very high levels, showing little evidence of waning. Data suggest that poverty and rural residence are strongly associated with child marriage globally, but particularly in West and Central Africa (UNICEF Citation2018). In these contexts, child marriage is over three times more common among those from the poorest wealth quintile relative to the richest wealth quintile (UNICEF Citation2018). There are several family, community, and societal/contextual reasons that may help explain why there is so much inertia behind the decline in child marriage (Kohno et al. Citation2020). As outlined in Batyra and Pesando (Citation2021), Kagitçibasi’s theory of family change describes the relationship between society/culture, family, and the resultant self, as well as how children are perceived by the parents as crucial ‘economic resources’ (Kagitçibasi Citation1996). In a poor context such as Mali—affected by economic uncertainty and conflicts of different magnitudes at the macro level, alongside practices such as arranged marriage and bride wealth at the household level—parental pressures are likely to drive earlier marriage, as financial transfers provide incentives for parents to marry daughters off early, especially in the poorest rural areas. Norms and traditions sustaining arranged marriage typically increase pressures and expectations on daughters beyond what the law imposes (Schaffnit and Lawson Citation2021). Related to the latter point, the theory by Gelfand et al. (Citation2006) introduces the concept of ‘cultural tightness–looseness’, which highlights the role of social norms in determining the socio-cultural sanctions imposed on people within societies if they transcend such norms. Additional factors underlying the sustained high prevalence of child marriage in Mali may be feelings of insecurity tied to violence and conflict (marriage as a protective strategy), insufficient protections and legal enforcement, discrepancies between societal and family knowledge regarding the official age at marriage, lack of autonomy in decision-making, and foremost, the strong influence of patriarchal ideologies that pervade the structure of Malian families and societies (Kohno et al. Citation2020; Schaffnit and Lawson Citation2021).

Theoretical channels

Given the sustained levels of child marriage in Mali, it is important to assess if the legal change introduced by the 2011 Family Code contributed to any change in the prevalence of early unions, particularly around the ‘newly legal’ ages of 16–17. A potential channel through which a lowered minimum legal age at marriage may raise child marriage is through a direct knowledge mechanism (i.e. familiarity with the change in the law and its consequences) whereby individuals (and families) shift their behaviours gradually by marrying (or marrying off daughters) at younger ages in response to the new law allowing them to do so. On one hand, in a hypothetical scenario where information reaches all strata of society equally and swiftly, this shift in early unions would be particularly apparent among low-income households: those facing the strongest financial pressures to marry off their daughters at a younger age, mainly for economic reasons. On the other hand, a solid body of research has suggested that in resource-deprived contexts characterized by rooted gender inequalities, widespread social acceptance of child marriage, and little or non-existent legal enforcement—especially poor rural areas, where most people ignore civil marriages and institutions and are unaware of legal changes (Soares Citation2009)—individuals hardly shift their behaviours at all in response to changes in legislation (Collin and Talbot Citation2017; Batyra and Pesando Citation2021), and this is even the case in instances of ‘favourable’ changes in legislation. This general lack of awareness and disregard for changes in the law may be similarly witnessed in instances of reverse policies, such as the one analysed here. In such a case, we might expect to observe little to no change in the prevalence of child marriage, irrespective of population group.

Although a direct knowledge mechanism is hardly plausible, especially in poor rural areas, the change in the law may have indirectly affected some poor individuals’ knowledge and perception regarding the acceptability of early marriage—mostly through community influences and/or exposure to different sources of media, which are widely available even among the poorest strata of society (de Bruijn et al. Citation2009; Pesando and Rotondi Citation2020)—and this only gradually led to behaviour change. In other words, while the law itself did not contribute to an immediate shift in behaviour, it may have shaped generalized knowledge and attitudes towards patriarchal and gender norms in societies and communities, ultimately resulting in a higher acceptability of early unions (indirect knowledge channel). While poor rural dwellers are typically the least aware of legal changes, plenty of recent research suggests that media and digital technologies—such as radio, television, and mobile phones—have pervaded every strata of society, with proportionally higher impacts among the poorest and most disadvantaged countries and communities (Aker and Mbiti Citation2010; Rotondi et al. Citation2020), even affecting gender norms and attitudes in multiple domains (Robert and Oster Citation2009; Varriale et al. Citation2022). Such a theorization would be in line with a world society perspective and socio-demographic frameworks of ideational change.

Socio-economic status (SES) differences in early marriage in Mali are vast, hence it is also critical to reflect on potential heterogeneities underlying these policy changes. As already mentioned, information asymmetries may play out differently across socio-economic strata in the context of reverse policy changes, leading to shifting norms and attitudes towards more conservatism (particularly among the poorest strata of society), accompanied by more binding community influences, including religious and customary ones. This is a plausible mechanism in the Malian context, where initial efforts to promote women’s rights in family and society, as embedded in the first draft of the law, were met with a backlash that led to the adoption of a more restrictive family law. The revocation of the initial draft could have led to the strengthening of conservative norms (norm-shifting channel), including those favouring early marriage: a phenomenon that is typically more pervasive among the least educated and most vulnerable strata of society. Higher educational attainment also plays a role in the acquisition, processing, and endorsement of legal information (such as a new law lowering the minimum legal age at marriage), as more highly educated women (who also possess, on average, greater decision-making power within the household) may be more aware of the negative implications of such a change and be in a better position to find effective loopholes to preserve the status quo and/or circumvent new regulations (education/empowerment of females channel). Relatedly, existing research from Cameroon has underscored the existence of significant differences in the normative endorsement of early marriage between more and less advantaged individuals in low-income contexts (Cislaghi et al. Citation2019).

Lastly, from a theoretical standpoint we might also observe an increase in early marriage following the law change for a whole range of reasons not tied to the law itself, such as generalized violence, economic instability, and situations of upheaval (such as the 2012 conflicts, which may have led to an increase in early marriage as a protective mechanism). While some of these factors are accounted for in the current study, others cannot be measured with the data at hand. It is also likely that aspects related to data collection and data quality, such as interviewer effects and mismatches in SES between interviewers and interviewees, may underlie changes in early marriage following the law implementation, independently of the law itself, as discussed next.

Data quality and data collection issues

When working with survey data collected in low-income contexts, and particularly with variables that rely on the correct reporting of age, it is good practice to reflect on how the data have been generated and the challenges that surveyors/enumerators may have faced when filling in questionnaires (Randall et al. Citation2013). This is especially the case in contexts often affected by conflict and where socio-economic disparities between communities—or between socio-economic groups within communities—are widespread. In Mali, for instance, poor rural dwellers have little to no contact with institutions and live in contexts where knowing one’s age is rare and largely irrelevant (Soares Citation2009). This creates critical issues for correct age reporting and—in this specific context—for the precise reporting of age at marriage on which our estimates are based. Such complexity, exacerbated by the socio-economic distance between interviewers and respondents, often leaves enumerators with a large degree of discretion in estimating women’s ages and ages at marriage. In our analysis, which focuses separately on high- and low-educated individuals, these issues may imply that age variables are correctly reported for the former group but estimated with uncertainty—or reported incorrectly—for the latter group (also due to the lack of a birth certificate, unnecessary for unschooled women).

In the context of a legal change, interviewers in poor rural areas may be faced with the challenge of estimating women’s ages and ages at marriage, and estimates may reflect their own knowledge of the change in the law, be it conscious or unconscious, resulting in reporting lower ages at marriage relative to the true unobserved ones. While evidence of interviewer-induced biases is pervasive (Randall et al. Citation2013, Citation2015; Chae Citation2016; Leone et al. Citation2021), there is little that can be done empirically (complementing with qualitative interviews would be the best strategy) besides acknowledging these intricacies and recognizing that shifts in marital behaviour may not be due to the law itself but to interviewers’ knowledge of the change in the law, which in turn shapes the way that information is recorded. Stated differently, poor data quality may constitute an alternative yet oft-neglected mechanism in studies of this kind.

Data and methods

We use data from the latest Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) conducted in Mali (hereafter referred to as the MDHS) in 2018 (INSTAT et al. Citation2019) and reconstruct cohorts of women retrospectively. The MDHS is a nationally representative survey of women and men aged 15–49. Although information for men is also available, we do not consider them here because marriage before age 18 was banned for men under both the 1962 and 2011 Codes (Nandi et al. Citation2018). The MDHS provides information about age at vital events (e.g. women’s date of birth, age at first union) and women’s socio-economic characteristics (e.g. educational level, household wealth status). Using information about women’s month and year of birth and when the new Family Code was introduced, we classify women into two groups according to their exposure to the new law. The first group consists of women who were not exposed to the new Family Code (i.e. were subject to the old law that prohibited marriage before age 18): more specifically, women aged 18 or older when the new Family Code was introduced in 2011, who in theory had not been allowed to marry before age 18. The second group consists of women who were exposed to the new Family Code (i.e. subject to the new minimum age at marriage of 16): specifically, women who were 17 or younger when the 2011 Family Code was passed and so had the opportunity to marry legally before age 18, not being subject to the child marriage ban.

Our analysis consists of three parts. First, we estimate long-term trends in the prevalence of child marriage for women who were aged 12–30 at the time of the new Family Code implementation and thus at least 18 at time of survey in 2018. This design allows us to avoid right censoring, whereby younger women would still be at risk of marrying before age 18 at time of survey. The sample sizes by individual age range from 230 to 544 for women aged 30 and 13, respectively, at the time of the law change and, except for four ages (30, 29, 26, 25), all include over 300 cases. We use information about women’s age at first union, which in the DHS corresponds to age at first marriage or first cohabitation, since no distinction is made between these two types of unions when the information is collected. Nonetheless, the vast majority of women in unions in Mali are married, and cohabitation is uncommon: in 2018, less than 1 per cent of women aged 15–49 reported being in a cohabitating union (Measure DHS Citation2022). Moreover, the focus on both marriage and living together is in fact preferable because in some African contexts the definition of unions is ambiguous, and distinguishing between formal and informal unions may be impossible (Casterline et al. Citation1986; Clark and Brauner-Otto Citation2015). Many couples who marry in Mali—an overwhelming majority in rural areas—never register their marriages (‘religious ceremonies’ in the language of Malian civil law) with the state, thus making any formal distinction impossible (Soares Citation2009). In other words, their marital unions are not recognized as civil marriages yet are still recorded in the DHS (to the best possible extent). Finally, we acknowledge the importance of incorporating further information about union characteristics that are relevant to the Malian context, for example, whether a given union is polygynous. However, this information is available only for women who are currently in a union; this makes it challenging to incorporate polygyny into the retrospective design of our study, given that we focus on women’s first unions.

Using data visualization techniques, we examine levels and trends in the prevalence of child marriage across cohorts of women exposed and not exposed to the new law, allowing us to cast light on whether the legal change was followed by a shift in marriage behaviour. When estimating the prevalence of child marriage, we use DHS sampling weights to account for the complex DHS survey design. In addition to the analysis for the whole female population, we also disaggregate trends by women’s educational level to explore heterogeneity across socio-economic strata. Since the majority of women in Mali have never attended school (61 per cent in 2018) (INSTAT et al. Citation2019), we divide women into those with no education (‘unschooled’) and those who have received some education (‘schooled’).

Educational level defined this way is the best proxy of women’s SES at time of first marriage available in the DHS. Attendance at school (or not) is set before the teenage years and before any women in our sample have entered their first union (our lowest recorded age at first marriage is 10). Thus, we increase our confidence that we are analysing the prevalence of child marriage by a characteristic that is arguably defined before first union. Other characteristics included in DHS, such as household wealth, refer only to time of survey and are unlikely to be stable over time. For instance, given that marriage is likely to result in moving between households, such current-status variables might not correspond to the wealth of the household in which a woman was living at the time of the law implementation. Moreover, household wealth at time of survey could be an outcome of the law change through its impact on women’s marriage trajectories: this is the case in places where bride wealth is common, such as parts of Mali and most sub-Saharan African countries (Melnikas et al. Citation2017; Womanstats Citation2021). For these reasons, we focus on educational level as the primary marker of women’s SES at the individual level and complement our analyses with ancillary georeferenced information on local development at the community/cluster level through the use of night-time lights, a well-established proxy of local development (Pokhriyal and Jacques Citation2017; Bruederle and Hodler Citation2018; Rotondi et al. Citation2020). Night-time lights data are obtained from the DHS geospatial covariate file and measured through the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS). Night-time lights are arguably exogenous to both the law implementation and its outcome, providing a rather stable measure of development, at least over a 10-year time frame.

Second, we conduct regression analyses—using linear probability models—to cast light on the relationship between exposure to the new law and probability of child marriage, while controlling for additional variables. Our outcome variable is a binary indicator referring to whether a given woman married for the first time before age 18 (‘1’ if yes, ‘0’ if no). In the models we include two key explanatory variables and their interaction term. The first is a binary indicator of exposure to the law, describing whether a given woman was exposed to the new Family Code (‘1’) or not (‘0’), as defined earlier. The second variable is a continuous indicator describing women’s age at the law implementation (Age at law). We include an interaction term between these two variables to examine whether trends in child marriage—represented by the regression slope coefficient—differed between women who were exposed to the new Family Code and those who were not.

For a more straightforward interpretation of this interaction term, we omit the main effect for the Age at law variable and estimate separate slope coefficients of Age at law for women exposed to the new Family Code and those not exposed. Moreover, we centre the variable Age at law at the cohort of women who were first to be exposed to the new law, such that the positive sign of the coefficient of the interaction term denotes a higher probability of child marriage among younger women. We run a series of regressions that include no additional controls (M1) and subsequently add control variables: women’s place of residence (urban–rural) and region of residence (M2). We include these variables because regional and urban–rural differences in child marriage in Mali are pronounced (Zegeye et al. Citation2021). Finally, all the regression analysis are disaggregated by women’s level of education.

Third, we conduct a series of ancillary analyses that serve as robustness checks and validation exercises, increasing the reliability of our estimates. First, we explore alternative age cut-offs to examine whether the implementation of the law resulted in shifts in marriage prevalence by cut-offs other than age 18. Second, we investigate whether the conflict that Mali has been experiencing over the last decade could have been a driver of changes in child marriage. To measure conflict intensity, we use data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (Sundberg and Melander Citation2013), which provides georeferenced estimates of conflict-related deaths across the world, including for Mali. Using these data, we compute the number of deaths within each administrative region of Mali between 2011 and 2018. We group regions into those affected by war to a small extent (i.e. fewer than 100 deaths: Sikasso, Kayes, Koulikoro) and those affected more (i.e. where the death toll exceeded 100: Ségou, Tombouctou, Kidal, Mopti, Gao).

Next, we leverage external georeferenced satellite data on intensity of night-time lights, which provide a good proxy for local development at the community level for women in our sample. Our goal is to provide evidence of heterogeneous associations by markers of SES that are rather stable over time and to capture both individual- and community-level socio-economic conditions. Night-time lights measure the average luminosity of an area within a 2-km (urban) or 10-km (rural) radius of the DHS cluster location. Note that out of 345 unique clusters, no GPS coordinates were recorded for 17, hence the analyses by local development level are limited to 328 unique clusters. The scale is continuous, ranging—in the context of Mali—between 0 and 22. As about 48 per cent of the observations are zeros, we dichotomize the continuous variable, creating a dummy variable for high vs low local development (dummy = 1 if night-time lights > 0, otherwise 0).

Lastly, we conduct some additional analyses drawing on previous MDHS survey waves (2001, 2006, 2012), focusing on the same birth cohorts surveyed at different time points, to explore the extent to which there may be reporting biases in child marriage estimates. Reporting bias is always an issue in retrospective studies on the topic, yet one underlying concern in the context of the general minimum age at marriage of 18 in place until 2011 is that people might have been reporting higher-than-actual age at marriage because marrying before age 18 was illegal. Once the ban was removed, people may have started reporting the true (lower) marriage age. As discussed earlier, other important concerns relate to mismatches between interviewers and interviewees’ SES, which may lead to conscious or unconscious misreporting of age variables for women in poor rural areas: for example reporting lower age at marriage for unschooled women because of interviewers’ (but not women’s) knowledge of the law.

Results

Changes in the prevalence of child marriage following the introduction of the new Family Code

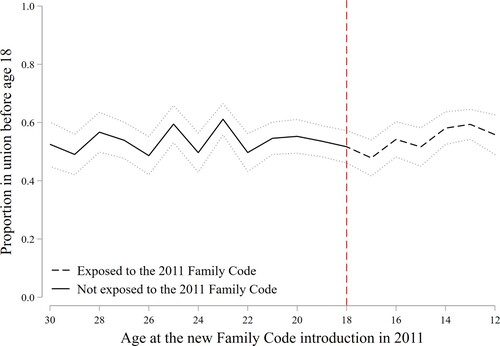

shows the proportion of women who entered their first union before age 18, by their age at the passing of the 2011 Family Code (including 95 per cent confidence intervals around the estimates). Despite women aged 18–30 having been subject to the old law prohibiting marriage before age 18, around 50 per cent of these women had married before age 18, which suggests that child marriage was prevalent despite the law banning it. This finding is in line with studies on low- and middle-income countries, discussed in the Background section, which showed that minimum-age-at-marriage laws rarely achieve their goal of reducing the prevalence of early marriage to a significant extent. The proportion of women marrying early among those exposed to the old law (aged 18–30) was relatively stable, with no apparent change over time, although a large degree of volatility in age-specific estimates should be acknowledged. Women who were aged 12–17 at the time of the new Family Code implementation were not subject to the law prohibiting marriage before age 18, thus were allowed to marry before that age. Although there appears to be a slight upward trend in the prevalence of child marriage following implementation, with younger women exhibiting increasing levels of early marriage, the confidence intervals around the point estimates for women younger and older than 18 overlap. This can be seen in detail in , which provides the exact values of the point estimates and 95 per cent confidence intervals (All women panel).

Figure 1 Proportion of women who entered their first union before age 18, by their age at (and hence exposure to) the 2011 Family Code implementation: all women, Mali

Notes: Proportions are estimated using DHS weights and account for the complex survey design. Dotted lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals around the estimates.

Source: MDHS 2018.

Table 2 Percentage of women who entered their first union before age 18, by their age at (and hence exposure to) the 2011 Family Code implementation: all women and by educational level, Mali

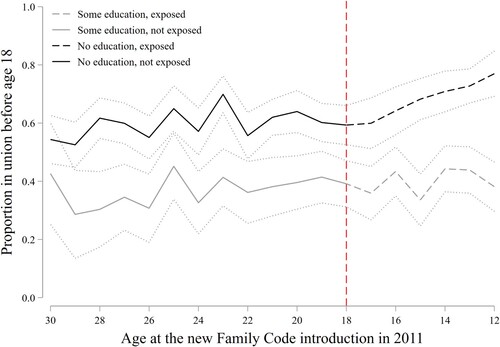

shows trends in child marriage prevalence disaggregated by women’s educational level. The prevalence of unions before age 18 was consistently lower among women with some education, as compared with women with no education. Due to the disaggregation of the sample into two groups based on women’s schooling, the estimates exhibit noticeable variability. Nonetheless, two patterns are worth noting. On one hand, among women with some education (grey line), the confidence intervals of the point estimates describing the proportion of women who entered their first union before age 18 are overlapping for all ages, that is, both among women who were subject to the minimum age at marriage of 18 and those who were not (see detailed point estimates and confidence intervals in , Some education panel).

Figure 2 Proportion of women who entered their first union before age 18, by their age at (and hence exposure to) the 2011 Family Code implementation: women by educational level, Mali

Notes: Proportions are estimated using DHS weights and account for the complex survey design. Dotted lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals around the estimates.

Source: As for .

On the other hand, the picture is different for women with no education (black dashed line), among whom the prevalence of child marriage started to increase after the new Family Code was introduced. Among women who were aged 12–17 at that time—who were no longer subject to the minimum age at marriage of 18 and were legally allowed to marry below that age—there is a smooth upward trend in the prevalence of child marriage, according to the central point estimates. Detailed estimates in (No education panel) show that 59 per cent of women who were 18 when the new Family Code was passed—thus were subject to the child marriage ban—married before age 18 (95 per cent confidence interval (CI): 53–66 per cent). Comparing these estimates with those for women subject to the new legal minimum age at marriage of 16, the confidence intervals overlap up until the cohort of women aged 14 when the new law was implemented. Conversely, the values for the youngest women covered by our analysis (i.e. those aged 13 and 12 in 2011) were 73 per cent (95 per cent CI: 67–79 per cent) and 79 per cent (95 per cent CI: 70–88 per cent), respectively, thus higher than among the last cohort (and the majority of cohorts) not exposed to the new law. When considering the point estimates and confidence intervals, no clear upward trend is observed among women aged at least 18 at the time of implementation, thus subject to the law banning marriage before age 18. These results suggest that the implementation of the new Family Code was accompanied by an increase in child marriage among the least educated (i.e. most vulnerable) women. These results suggest that the new Family Code allowing early marriage may have contributed to growing socio-economic inequality in child marriage, because the gap in child marriage between the more and the less educated grew for more recent cohorts.

The following subsections present our additional regression analyses and a series of robustness checks. These analyses corroborate our findings that following the lowering of the legal minimum age at marriage, the prevalence of child marriage increased among women from the lowest socio-economic strata. Interestingly, this finding was also confirmed when limiting the analysis to the capital city, Bamako (suggesting that it is not only a finding tied to an urban–rural divide), and the cleavage by SES (schooled vs unschooled) was also apparent within the main city (supplementary material, Figure S1). That said, concerns about data quality and interviewer-induced biases remain valid and may similarly contribute to explaining some of these findings.

Regression analyses

We conduct regression analyses to cast further light on educational differences in the relationship between exposure to the new law and probability of child marriage. These analyses aim to explore whether the introduction of the new law was associated with a shift in marriage behaviour, resulting in distinct child marriage trends before and after law implementation and between educational groups, including when controlling for additional variables. In line with results from , our findings in show how child marriage trends differed by women’s educational level. Among women with some education, the coefficients of the interaction terms are not significantly different from zero both for women exposed and those not exposed to the new law (in models without and with controls). This means that the probability of child marriage was stable among women with some education, whether exposed to the new Family Code or not.

Table 3 Linear probability models predicting the probability of first union before age 18, by exposure to the new 2011 Family Code and by educational level: women in Mali

Conversely, among women with no education, the interaction term suggests that the trend in the probability of child marriage across cohorts differed between women exposed to the new law and those not exposed. The coefficient of the interaction term Not exposed to the law × Age at law, which describes the change in the probability of child marriage among women not exposed to the new Family Code, does not statistically differ from zero in either the M1 or M2 models. This suggests stability in child marriage trends among women with no education who were not exposed to the new Family Code. Conversely, the coefficients of the interaction term Exposed to the law × Age at law (which describes the change in the probability of child marriage among women with no education who were subject to the new Family Code) are 0.02 and 0.03 in the models without controls (M1) and with controls (M2), respectively. This suggests the emergence of an upward slope in the probability of child marriage among unschooled women subject to the new minimum age at marriage of 16 (recall that the variable Age at law is centred at the cohort of women who were the first to be exposed to the new law, such that the positive sign of the coefficient of the interaction term denotes a higher probability of child marriage among younger women). Substantively, these results suggest that among women with no schooling, being exposed to the new Family Code and being younger by one year are associated with an increase in child marriage of two (M1) to three (M2) percentage points.

Ancillary analyses

Alternative age cut-offs. As described in the Background section, both the old and new family legislation included some exceptions under which women could marry earlier than permitted according to the general legal minimum age at marriage. For this reason, we explore alternative exposure classifications to identify whether the implementation of the new law resulted in shifts in the prevalence of marriage by cut-offs other than age 18. The 2011 Family Code does not include any exemptions to the minimum age at marriage of 16 with parental consent; this can be interpreted such that both the general minimum age at marriage and the minimum age at marriage with parental consent are 16 years. As before 2011 the legal minimum age for marriage with parental consent was 15, we check whether there have been any changes in the prevalence of marriage before age 16 due to the new law implementation. Thus, for the purpose of this sensitivity analysis, we restrict the sample to women aged at least 16 at time of survey (i.e. aged 10–30 in 2011).

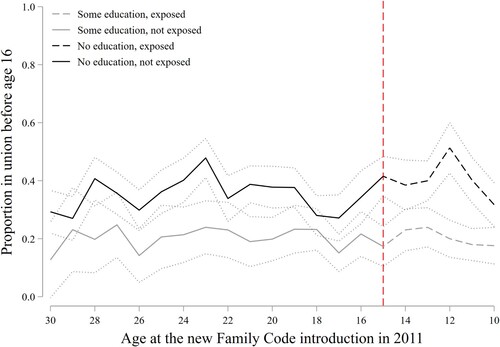

shows no evidence of an increase in marriage before age 16 following the law implementation, neither among women with some education nor among women who have never attended school. The prevalence of very early unions is relatively stable across cohorts, both those affected and unaffected by the law change, and there is no discernible change in the trend in the prevalence of marriage before age 16. This suggests that the law implementation was not associated with shifts in very early union formation (below age 16).

Figure 3 Proportion of women who entered their first union before age 16, by their age at (and hence exposure to the 2011 Family Code implementation): women by educational level, Mali

Notes: Proportions are estimated using DHS weights and account for the complex survey design. Dotted lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals around the estimates.

Source: As for .

Potential macro-level confounders

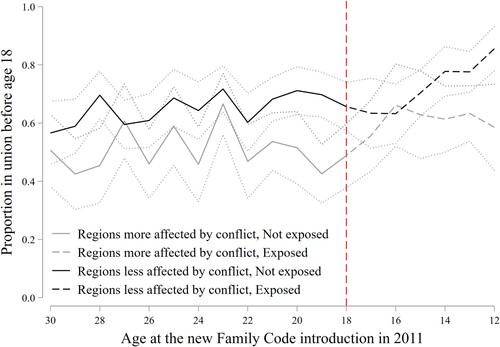

Mali has experienced sustained conflicts and severe economic sanctions over the past decade. Results of the analysis disaggregated by conflict intensity for women with no education show that the increase in child marriage prevalence in areas more affected by conflict was no larger than in areas less affected by it (). The fact that the regions particularly affected by the war do not exhibit a more pronounced change in child marriage among the least educated suggests that the increasing prevalence of union formation before age 18 is unlikely to be related to consequences of war.

Figure 4 Proportion of women who entered their first union before age 18, by their age at (and hence exposure to) the 2011 Family Code implementation, for regions that were more and less affected by the conflict: women with no education, Mali

Notes: Regions more affected by conflict (>100 deaths between 2011 and 2018) were Ségou, Tombouctou, Kidal, Mopti, and Gao. Regions less affected by conflict (<100 deaths between 2011 and 2018) were Sikasso, Kayes, and Koulikoro. Data on conflict intensity are based on the number of deaths (best estimates) from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (Sundberg and Melander Citation2013). Proportions are estimated using DHS weights and account for the complex survey design. Dotted lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals around the estimates.

Source: As for .

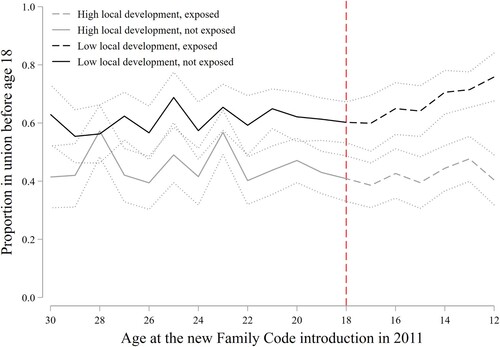

Socio-economic status at the community level

We use georeferenced data on night-time lights to provide a meso-level counterpart to the individual-level analyses of heterogeneity by educational level (Benjamin et al. Citation2018) and one that is arguably more reliable than relying on the more volatile household-level measure of wealth captured by the wealth index. The Night-time lights variable proxies for conditions of local development within the community, with the underlying idea being that socio-economic development is higher where lights at night are more widespread. The results in mirror almost exactly those in and provide evidence of an increase in the prevalence of early marriage among exposed women living in communities where socio-economic development is lower. Detailed numerical estimates are reported in the supplementary material (Table S1).

Figure 5 Proportion of women who entered their first union before age 18, by their age at (and hence exposure to) the 2011 Family Code implementation: women by level of local development, Mali

Notes: Proportions are estimated using DHS weights and account for the complex survey design. Dotted lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals around the estimates. High local development is defined as night-time lights > 0. GPS coordinates are not available for 17 DHS clusters, so this analysis is limited to 328 unique clusters, of which half (167) report a value of zero for lights, hence the dichotomization.

Source: As for .

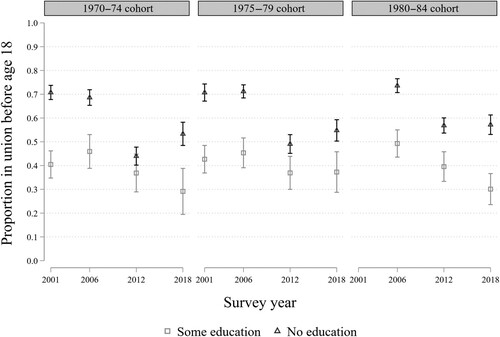

Reporting bias in ages at first union and interviewers’ effects

We conclude this investigation by conducting analyses aimed at testing the consistency around the estimates of child marriage prevalence for selected cohorts across four MDHS rounds conducted in Mali in 2001, 2006, 2012, and 2018. In doing so, we aim to rule out valid concerns that our results could be driven by biases related to misreporting of age at first union, especially among unschooled women. This analysis attempts to check that the identified increase in child marriage among women with no education is not driven by, for example, a change in women’s and/or interviewers’ propensities to report ‘artificial’ early marriage due to the law change, as outlined in the Background section. We follow an empirical strategy that compares estimates for the same birth cohorts at different points in time (i.e. survey years), in a spirit similar to Fan et al. (Citation2022) in their study of child marriage in China. Specifically, we choose three cohorts for which it is possible to estimate the proportion of women who entered their first union before age 18 across multiple survey rounds (1970–74 and 1975–79 cohorts across all four survey waves; 1980–84 across the latest three survey waves) and compare whether the estimates are consistent.

shows that across all cohorts, trends in both educational groups are similar, in that there is less reporting of child marriage in 2018 and 2012 than in 2006 and 2001, albeit this pattern is more visible for the unschooled group. Among women with some education, the prevalence of child marriage for the same cohort is similar across all survey rounds, with most 95 per cent CIs overlapping. Results for women with no education are more complex but, overall, across all cohorts the estimates from earlier surveys are significantly higher (non-overlapping CIs) than those from later ones. The fact that women belonging to the same cohort are no more likely (if anything, the unschooled are less likely) to report that they married early in surveys conducted after the law implementation (2012 and 2018) increases our confidence that the changes we document are unlikely to be driven fully by age misreporting and/or changing propensity to report early marriages. Nonetheless, our findings reveal relative stability in estimates among the schooled population, alongside important discrepancies in age reporting among the unschooled population (see also supplementary material, Figure S2), which may suggest the presence of some recall and/or reporting biases and/or mismatches in SES between interviewers and interviewees. This calls for better data collection efforts, especially among disadvantaged populations.

Figure 6 Proportion of women who entered their first union before age 18 for selected cohorts across four DHS rounds: Mali

Notes: Proportions are estimated using DHS weights and account for the complex survey design. Chart shows point estimates and 95 per cent confidence intervals. Due to differences in survey design and coverage across the survey rounds, we exclude three regions of Mali—Tombouctou, Gao, and Kidal—to ensure that the estimates across surveys are fully comparable

Source: MDHS 2001, 2006, 2012, and 2018.

Conclusions

Using the latest DHS from Mali, this study adopted a cohort perspective to explore changes in child marriage prevalence following a change in age-at-marriage law in Mali: what we labelled reverse policy, a specific country scenario involving the new 2011 Family Code that, with a few exceptions, lowered the general minimum age at marriage from 18 to 16. We conducted this analysis with the aim of complementing the blossoming literature investigating the effectiveness of increases in minimum age at marriage on women’s marriage and fertility trajectories, a set of studies which has reached very mixed and context-specific conclusions (Dahl Citation2010; Collin and Talbot Citation2017; Amirapu et al. Citation2020; Bellés-Obrero and Lombardi Citation2020; Rokicki Citation2020; Batyra and Pesando Citation2021; McGavock Citation2021). Some recent studies from Ethiopia found that raising the minimum age at marriage led to large reductions in rates of adolescent birth, child marriage, and early sexual initiation (e.g. Rokicki Citation2020), thus suggesting that strong legal frameworks for gender equality may be effective catalysts in facilitating social change in child marriage; however, paying attention to specific layers of heterogeneity within the population weakens the conclusions to a significant extent. For instance, within the same country context (Ethiopia), McGavock (Citation2021) found that the effects of the reform, though large at the population level, were insignificant among women belonging to ethnic groups with the strongest norms favouring child marriage. Findings related to the mixed and context-specific effectiveness of policy changes aimed at curbing early marriage align with claims made by Arthur et al. (Citation2018) and Collin and Talbot (Citation2017), who showed that despite the increasing prevalence of ‘protective’ legal provisions, the level of enforcement varies widely, and legal exceptions based on parental consent and customary or religious laws remain in place—alongside high rates of illegal or informal marriage (Collin and Talbot Citation2017; Bellés-Obrero and Lombardi Citation2020)—thus preventing the full effectiveness of the legal provisions. What happens, then, when the minimum age at marriage is effectively lowered rather than raised? Do we observe the same type of heterogeneity? Do we observe similar loopholes? In this study, we sought to answer these research questions by focusing on an ‘extreme-case’ scenario (i.e. a country with one of the highest child marriage rates in the world).

We conducted this study by adopting a retrospective cohort-level approach, leveraging data visualization techniques, regression analyses, and a series of robustness checks to test for potential confounders, macro-level discontinuities, and age misreporting biases. In so doing, we paid particular attention to specific layers of disadvantage at both the individual and community levels (e.g. educational level; local development). We reached two sets of findings. The first set of results suggested that lowering the general minimum age at marriage to 16 was not associated with a change in child marriage prevalence for the Malian female population as a whole: child marriage remains a very pervasive practice in the country, as even among the youngest cohorts around 50 per cent of women marry before age 18, due primarily to customary practices and financial pressures to marry daughters off early in the face of economic adversity. The second set of results suggested that once different layers of socio-economic heterogeneity were taken into account, the decrease in the general minimum age at marriage was associated with an increase in child marriage among the most disadvantaged women. Relying on educational level as the primary marker of disadvantage, we found that child marriage prevalence increased from 59 to 79 per cent among the youngest cohort of women with no education who were legally allowed to marry at age 16. Similar results were found among women living in areas characterized by very low local development, where child marriage prevalence increased from 60 to 76 per cent.

Returning to the theoretical channels outlined earlier, our results are partly compatible with an indirect knowledge and a norm-shifting mechanism, whereby the law itself may not have contributed to an immediate shift in behaviour yet it may have shaped generalized knowledge and attitudes towards patriarchal and gender norms in more conservative areas. This may have occurred, for instance, through community influences and/or exposure to different sources of media, ultimately resulting in heightened financial pressures to marry off daughters earlier among the poorest populations and most disadvantaged communities. While we expected economic and political instability to play an important role in increasing child marriage among the poorest, our analyses did not provide support to such a hypothesis, although we acknowledge that there may be alternative—and, arguably, more effective—ways of measuring economic and political instability.

Not least, our checks for reporting biases in age at marriage did not reveal increased reporting of child marriage in more recent surveys within the same cohort (rather, the opposite), thus suggesting that our results are unlikely to be entirely driven by such a channel. This makes sense from a purely theoretical standpoint, as lower-SES women—especially in resource-deprived and predominantly rural contexts—are less likely to be aware of changes in laws, hence they constitute the bulk of individuals who are least likely to react ‘strategically’ to such changes. In other words, the misreporting argument would need to rest on an assumption that lower-SES individuals are somehow more aware of changes in the law or more concerned about legal penalties than higher-SES individuals, a hypothesis which finds little applicability in the Malian context, as confirmed by the proportionally stronger implications of the change in the law for lower-SES individuals (rather than higher-SES ones).

The lack of alternative data sources and the difficulty of capturing reporting biases by means of purely quantitative analyses do not allow us to provide further empirical tests to cast light on this matter. We thus cannot reject this explanation; we remain open to the possibility that data quality issues, including those resulting from mismatches in SES between interviewers and interviewees, may have played some role in driving the documented increase in child marriage. The finding that discrepancies in age misreporting are more evident among the unschooled population cannot be stressed enough. The results highlight the importance of paying attention to potential survey data quality issues when studying responses to changes in age-at-marriage laws, particularly in contexts such as Mali, where many people do not know and/or remember their age.

Despite these important limitations, by identifying particularly vulnerable groups of women within the population, this study is among the first to suggest that repealing existing legislative frameworks aimed at protecting young women from harmful practices can have severe and irreversible consequences for women’s health and well-being. A statistically significant increase of 20 percentage points in the likelihood of experiencing child marriage among women with no education (who in Mali constitute the vast majority of the population) is a really marked effect size, which should swiftly catalyse attention and mobilize practitioners and policymakers working in the areas of human rights, reproductive health, and gender inequalities, irrespective of the main underlying channel. Given the long-term implications of child marriage for women’s life-course trajectories and those of their children (Jensen and Thornton Citation2003; Otoo-Oyortey and Pobi Citation2003; Ashcraft and Kevin Citation2006; Field and Ambrus Citation2008; Dahl Citation2010; Raj Citation2010; Efevbera et al. Citation2017; Yount et al. Citation2018; Sunder Citation2019), addressing this is of utmost importance to avoid widening inequalities in life-course trajectories, which are already highly unequal to start with, any further.

When thinking about different types of inequalities, it is key to devise interventions that will protect the most vulnerable population strata: policies that will break the cycles of gender and socio-economic inequalities that contribute to reinforcing dynamics of poverty and unequal decision-making power within couples and in society. In the United Nations SDG framework, such efforts are central not only to achieving SDG 5.3 (related to the elimination of ‘all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation’) but also SGD 1 (tied to ‘end poverty’) and SDG 8 (tied to ‘economic growth’), among others (United Nations Citation2016). Although existing research has revealed that legislative frameworks are only partially effective, this paper suggests that it is all the more crucial to sustain and further strengthen legislative efforts to protect the rights of girls and women, including through better monitoring and enforcement mechanisms. We also support the view that such national marriage policies would have a more meaningful impact if part of a comprehensive, multipronged, and context-sensitive approach targeting poverty and rooted social norms in all their forms: including through raising awareness among parents and young people, better integrating women in economic, social, cultural, and political activities, and targeting explicit educational and reproductive-health interventions towards youth (Batyra and Pesando Citation2021).

Given the marked discrepancies in age misreporting between schooled and unschooled women, we also encourage scholars and practitioners to question more critically the nature and reliability of the data they rely on and also to combine quantitative evidence with thorough qualitative insights through ethnographic research whenever possible: a fruitful avenue for future research. Echoing Randall et al. (Citation2013), we note that in contexts where survey concepts are often different from local concepts and interviewers are socio-economically distant from respondents, persuasive social skills and an ability to follow precise wording are essential for improving the reliability of the data produced.

We conclude this study by highlighting the relevance of our findings for other country contexts where similar reverse policies have been implemented or considered. While these constitute rare instances, the Malian case is not an isolated one. For instance, Yemen is one of the countries with no legislation on minimum age at marriage, and there have even been discussions of setting the minimum age to coincide with when a woman is ‘ready’ (i.e. reaches puberty). According to the PROSPERED database, the current lack of a minimum age at marriage in Yemen is the result of a legislative change in 1998, which overrode previous provisions banning marriage below age 15 (Nandi et al. Citation2018). Thus, although child marriage—defined as marriage below age 18—was legally allowed prior to 1998, the new law effectively reversed the existing provisions that aimed to protect girls from extremely early union formation. Similarly, in 2014, lawmakers in Bangladesh proposed to lower the minimum age at marriage for girls from 18 to 16 years. With much resistance from policymakers and international NGOs, the proposal was never implemented, as Kofi Annan—alongside the Girls Not Brides global partnership—successfully managed to warn politicians that ‘such a change in legislation would undermine efforts to reduce poverty and improve the welfare of girls and women across Bangladesh’ (Girls Not Brides Citation2014). Results from our study fully support these statements, and we are hopeful that scholars, policymakers, and lawmakers concerned with promoting health and well-being of populations across disadvantaged contexts will take them at face value.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (214.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Ewa Batyra is based at the Centre for Demographic Studies (CED-CERCA), Spain, and the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Germany. Luca Maria Pesando is based in the Division of Social Science, New York University Abu Dhabi in the UAE and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs (WCFIA), Harvard University, USA.

2 Please direct all correspondence to Ewa Batyra, Centre for Demographic Studies (CED-CERCA), Carrer de Ca n’Altayó, Edifici E2, 08193, Barcelona, Spain; or by Email: [email protected] and [email protected]

3 We acknowledge support of the University of Pennsylvania through the Global Family Change (GFC) Project (NSF Grant 1729185, PIs: Kohler & Furstenberg). Ewa Batyra acknowledges funding from the Max Planck Society and the Centre for Demographic Studies: Juan de la Cierva Individual Fellowship (FJC2019-040652-I), GLOBFAM (RTI2018-096730-B-I00), and MINEQ (H2020-ERC-2020-STG-GA-948557-MINEQ). Luca Maria Pesando acknowledges support from the Insight Development Grant (Fund #: 430-2021-00147) awarded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada (PI: Pesando), the Jacobs Foundation Research Fellowship Program (2021-1417-00), the Division of Social Science at New York University Abu Dhabi (76-71240-ADHPG-AD405), and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard. The authors are grateful for useful comments and suggestions received during the 2021 International Population Conference (IPC) and the 2022 Population Association of America (PAA) annual meeting. Colleagues at McGill University provided particularly helpful suggestions. The authors would also like to thank Dr Bruce Whitehouse for providing rich and valuable feedback and reading resources on the Malian context.

References

- Aker, J. C., and I. M. Mbiti. 2010. Mobile phones and economic development in Africa, Journal of Economic Perspectives 24(3): 207–232. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.24.3.207

- Amirapu, A., M. N. Asadullah, and Z. Wahhaj. 2020. Can Child Marriage Law Change Attitudes and Behaviour? Experimental Evidence from an Information Intervention in Bangladesh. EDI Working Paper Series.

- Arthur, M., A. Earle, A. Raub, I. Vincent, E. Atabay, I. Latz, G. Kranz, A. Nandi, and J. Heymann. 2018. Child marriage laws around the world: Minimum marriage age, legal exceptions, and gender disparities, Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 39(1): 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2017.1375786

- Ashcraft, A., and L. Kevin. 2006. The Consequences of Teenage Childbearing. Working Paper No. 12485, Cambridge, MA.

- Assemblée Nationale. Code du mariage et de la tutelle [Code of Marriage and Guardianship] (1962). LOI NO 62-17 AN-RM, Mali.

- Assemblée Nationale. Portant Code Des Personnes Et De La Famille [On the Personal and Family Code], (2011). LOI N°2011–087, Mali.

- Batyra, E., and L. M. Pesando. 2021. Trends in child marriage and new evidence on the selective impact on changes in age-at-marriage laws on early marriage, SSM – Population Health 14: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100811

- Bellés-Obrero, C., and M. Lombardi. 2020. Will You Marry Me, Later ? Age-of-Marriage Laws and Child Marriage in Mexico. Discussion Paper No. 139.

- Benjamin, M., T. D. Fish, D. Eitelberg, and Dontamsetti Mayala. 2018. The Geospatial Covariate Datasets Manual (Second Edition). Rockville, MD: ICF.

- Bruederle, A., and R. Hodler. 2018. Nighttime lights as a proxy for human development at the local level, PLoS ONE 13(9): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202231

- Burrill, E. 2020. Legislating marriage in postcolonial Mali: A history of the present, in L. Boyd and E. Burrill (eds), Legislating Gender and Sexuality in Africa : Human Rights, Society, and the State, pp. 25–41. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Casterline, J. B., L. Williams, and P. McDonald. 1986. The age difference between spouses: Variations among developing countries, Population Studies 40(3): 353–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000142296

- Chae, S. 2016. Forgotten marriages? Measuring the reliability of marriage histories, Demographic Research 34(1): 525–562. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2016.34.19

- Cislaghi, B., G. Mackie, P. Nkwi, and H. Shakya. 2019. Social norms and child marriage in Cameroon: An application of the theory of normative spectrum, Global Public Health 14(10): 1479–1494. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2019.1594331

- Clark, S., and S. Brauner-Otto. 2015. Divorce in sub-Saharan Africa: Are unions becoming less stable?, Population and Development Review 41(4): 583–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00086.x

- Collin, M., and T. Talbot. 2017. Do Age-of-Marriage Laws Work? Evidence from a Large Sample of Developing Countries. Center for Global Development Working Paper 458.

- Dahl, G. B. 2010. Early teen marriage and future poverty, Demography 47(3): 689–718. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0120

- de Bruijn, M., F. Nyamnjoh, and I. Brinkman. 2009. Mobile Phones: The New Talking Drums of Everyday Africa. Bamenda: Langaa Publishers /ASC.

- Delprato, M., K. Akyeampong, R. Sabates, and J. Hernandez-Fernandez. 2015. On the impact of early marriage on schooling outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa and South West Asia, International Journal of Educational Development 44: 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.06.001

- Efevbera, Y., J. Bhabha, P. E. Farmer, and G. Fink. 2017. Girl child marriage as a risk factor for early childhood development and stunting, Social Science and Medicine 185: 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.027

- Fan, S., Y. Qian, and A. Koski. 2022. Child marriage in Mainland China, Studies in Family Planning.

- Field, E., and A. Ambrus. 2008. Early marriage, age of menarche, and female schooling attainment in Bangladesh, Journal of Political Economy 116(5): 881–930. https://doi.org/10.1086/593333

- Flynn, C., C. Orlassino, and G. Szabo. 2021. Ending child marriage and accelerating progress for gender equality, Mali. Save the Children Spotlight Series.

- Gelfand, M. J., L. H. Nishii, and J. L. Raver. 2006. On the nature and importance of cultural tightness-looseness, Journal of Applied Psychology 91(6): 1225–1244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1225

- Girls Not Brides. 2014. “Lowering the marriage age in Bangladesh: A step in the wrong direction” writes Kofi Annan. https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/articles/lowering-marriage-age-step-wrong-direction-kofi-annan-warns-bangladesh/.

- Girls Not Brides. 2021. Child Marriage Atlas. London: Girls Not Brides.

- Hertrich, V., and M. Lesclingand. 2012. Adolescent migration and the 1990s nuptiality transition in Mali, Population Studies 66(2): 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2012.669489

- INSTAT, CPS/SS-DS-PF, and ICF. 2019. Enquête Démographique et de Santé au Mali 2018 [Demographic and Health Survey of Mali 2018]. Bamako, Mali et Rockville, MD, USA : INSTAT, CPS/SS-DS-PF et ICF.

- Jensen, R., and R. Thornton. 2003. Oxfam GB Early Female Marriage in the DevelopingSource: Gender and Development (Vol. 11).

- Kagitçibasi, C. 1996. Family and Human Development Across Cultures: A View from the Other Side. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Kang, A. 2015. Bargaining for Women’s Rights: Activism in an Aspiring Muslim Democracy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Kohno, A., T. Techasrivichien, S. Pilar Suguimoto, M. Dahlui, N. D. Nik Farid, and T. Nakayama. 2020. Investigation of the key factors that influence the girls to enter into child marriage: A meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence, PLoS ONE 15(7 July): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235959

- Lardoux, S. 2004. Marital changes and fertility differences among women and men in urban and rural Mali, African Population Studies 19(2): 89–123.

- Leone, T., L. Sochas, and E. Coast. 2021. Depends who’s asking: Interviewer effects in Demographic and Health Surveys abortion data, Demography 58(1): 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-8937468

- McGavock, T. 2021. Here waits the bride? The effect of Ethiopia’s child marriage law, Journal of Development Economics 149(December 2018): 102580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102580

- Measure DHS. 2022. STATcompiler.

- Melnikas, A. J., S. Engebretsen, S. Ami, and M. Gueye. 2017. Child marriage in Mali and Niger: Timing, processes, and transactions. Paper presented at the International Union for Scientific Study of Population, Cape Town, October 29–November 4, 2017.

- Nandi, A., I. Vincent, and E. Atabay. 2018. PROSPERED Dataset: Minimum age for marriage. Harvard Dataverse, V5, Harvard Dataverse, V5.

- Otoo-Oyortey, N., and S. Pobi. 2003. Early marriage and poverty: Exploring links and key policy issues, Gender and Development 11(2): 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/741954315

- Pesando, L. M., and V. Rotondi. 2020. Mobile technology and gender equality, in W. Leal Filho, A. Azul, L. Brandli, A. Lange Salvia and T. Wall (eds), Gender Equality. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (pp. 1–13). Cham: Springer.

- Pokhriyal, N., and D. C. Jacques. 2017. Combining disparate data sources for improved poverty prediction and mapping, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114(46): E9783–E9792. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1700319114

- Raj, A. 2010. When the mother is a child: The impact of child marriage on the health and human rights of girls, Global Child Health 95(11): 931–935. http://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2009.178707

- Randall, S., E. Coast, P. Antoine, N. Compaore, F.-B. Dial, A. Fanghanel, S. B. Gning, et al. 2015. UN census “households” and local interpretations in Africa since independence, SAGE Open 5(2): 215824401558935. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015589353

- Randall, S., E. Coast, N. Compaore, and P. Antoine. 2013. The power of the interviewer, Demographic Research 28(27): 763–792. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2013.28.27

- Robert, J., and E. Oster. 2009. The power of TV: Cable television and women’s status in India, Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(3): 1057–1094. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.3.1057

- Rokicki, S. 2020. Impact of family law reform on adolescent reproductive health in Ethiopia: A quasi-experimental study, World Development 144: 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105484

- Rotondi, V., R. Kashyap, L. M. Pesando, S. Spinelli, and F. C. Billari. 2020. Leveraging mobile phones to attain sustainable development, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(24): 13413–13420. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1909326117

- Schaffnit, S. B., and D. W. Lawson. 2021. Married too young? The behavioral ecology of ‘child marriage’, Social Sciences.

- Soares, B. F. 2009. The Attempt to Reform Family Law in Mali, Die Welt des Islams 49: 398–428. Leiden: Brill.

- Sundberg, R., and E. Melander. 2013. Introducing the UCDP georeferenced event dataset, Journal of Peace Research 50(4): 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343313484347

- Sunder, N. 2019. Marriage age, social status, and intergenerational effects in Uganda, Demography 56(6): 2123–2146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00829-8

- UN Human Rights Council. 2012. Summary: [Universal Periodic Review]: Mali / prepared by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in accordance with paragraph 5 of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 16/21. 30 October 2012, A/HRC/WG.6/15/MLI/3.

- UNICEF. 2018. Child Marriage in West and Central Africa. New York: UNICEF.

- United Nations. 2016. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

- Varriale, C., L. M. Pesando, R. Kashyap, and V. Rotondi. 2022. Mobile phones and attitudes towards women’s participation in politics: Evidence from Africa, Sociology of Development 8(1): 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1525/sod.2020.0039

- Whitehouse, B. 2016. Sadio’s choice: Love, materialism, and consensual marriage in Bamako, Mali, Africa Today 62(3): 29–46. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.62.3.29

- Whitehouse, B. 2022. Male dominance versus female hidden power: Patriarchy, marriage, and gender in Bamako, Mali, L’Ouest Saharien 16: 119–141. https://doi.org/10.3917/ousa.221.0119

- Whitehouse, B. 2023. Enduring Polygamy: Plural Marriage and Social Change in an African Metropolis. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Womanstats. 2021. Brideprice/Dowry/Wedding Costs (Types and Prevalence).

- Yount, K. M., A. A. Crandall, and Y. F. Cheong. 2018. Women’s age at first marriage and long-term economic empowerment in Egypt, World Development 102: 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.09.013

- Zegeye, B., C. Z. Olorunsaiye, B. O. Ahinkorah, E. K. Ameyaw, E. Budu, A. A. Seidu, and S. Yaya. 2021. Individual/household and community-level factors associated with child marriage in Mali: Evidence from Demographic and Health Survey, BioMed Research International 2021: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5529375