?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Intermarriage between immigrants and native individuals highlights the need to study childbearing as a joint decision of couples, because fertility preferences are likely to differ for the two partners involved. This study focuses on Sweden, where the majority population holds a relative preference for daughters but many immigrants come from countries with son preferences. Using longitudinal registers for the period 1990–2009, I analyse third-birth risks according to the sex composition of previous children and type of union. Doing so allows the study of preferences from behavioural data: couples with a daughter preference, for example, are more likely to have another child if their two previous children were boys. Results show that third-birth risks tend to be higher in unions between Swedish women and immigrant men, whereas unions between Swedish men and immigrant women tend to exhibit lower third-birth risks. Son preferences are rarely realized in intermarriages.

Introduction

There is a growing body of demographic literature focusing on international migrant fertility, particularly fertility levels (e.g. Abbasi-Shavazi and McDonald Citation2000; Mayer and Riphahn Citation2000; Andersson Citation2004; Sobotka Citation2008; Adsera and Ferrer Citation2014; Kulu and González-Ferrer Citation2014). Surprisingly, international migrants’ preferences for sons vs daughters are an aspect of immigrant fertility that has received far less study. By focusing on fertility levels, many scholars have overlooked the fact that immigrants’ preferences for the sex of their children could make an interesting case study, since there are strong son preferences in certain parts of the world (Bongaarts Citation2013)—particularly in Asia (Guilmoto Citation2009)—that are not found in Western migrant-receiving countries. I argue that preferences for the sex composition of children are an important aspect of migrant fertility, since they offer insights into the relative importance of migrant origin and the processes of adaptation related to fertility behaviour. In the present study, I go one step beyond the study of sex composition preferences in immigrant unions and focus on the previously unaddressed topic of fertility patterns in intermarriages between non-Western immigrants and native Swedes. Native Swedes are defined here as native-born individuals with two native-born parents.

Although intermarried migrants (those in exogamous unions) are only a small proportion of all migrants, focusing on intermarried couples addresses the larger matter of fertility decision-making: it highlights the need to study childbearing as a joint decision of couples rather than limiting the analysis to the mother’s fertility (and origin). Sweden provides a particularly interesting context for this study, because it hosts many immigrants from various countries (Bevelander Citation2010) and because the majority population holds a relative preference for daughters (Andersson et al. Citation2006; Miranda et al. Citation2018), whereas certain immigrant groups hold distinct son preferences (Mussino et al. Citation2019, Citation2018).

Different empirical strategies have been used to study parents’ preferences for the sex of their offspring, ranging from surveys to the study of parity progressions and analysing sex ratios at birth. In this study, I investigate parents with two common biological children and analyse whether the likelihood of having a third child depends on the sex of the previous two. Analysing the transition to third birth has become a common way to assess sex preferences for children, using behavioural data. The main assumption behind the approach is that parents take the sex of their previous children into account when making decisions about further childbearing. I follow Pollard and Morgan (Citation2002) in assuming that the transition from parity two to parity three is the most informative of parental preferences in below-replacement-fertility settings with a two-child norm. A relatively strong two-child norm exists in Europe, including in Sweden (Sobotka and Beaujouan Citation2014). To address the question of sex composition preferences for children in immigrant–native intermarriages, I use event-history techniques and analyse transitions to third birth using Sweden’s longitudinal population registers for the period 1990–2009. I focus on adult immigrants, to ensure that immigrants’ main socialization took place in the origin country rather than in Sweden.

Parental sex preferences for children in different parts of the world

Parental preferences for sons are widespread: today, several countries report sex ratios at birth that are well above the natural ratio of about 105 male to 100 female births. Significantly elevated sex ratios have been observed only in recent decades and are a strong indication of sex-selective abortion, particularly when occurring at higher parities (Bongaarts Citation2013; Guilmoto Citation2015). The most skewed sex ratios have been found in China, India, and South Korea, as well as more recently in post-Soviet countries and in Vietnam (Guilmoto Citation2015). While several of these countries have shown declining sex ratios at birth in recent years (Ritchie Citation2019), South Korea is one of very few countries to have reversed the trend and reduced its sex ratio at birth to natural levels (Boer and Hudson Citation2017). Skewed sex ratios at birth are a particularly strong indication of specific preferences for the sex of children but are absent in some other parts of the world despite existing son preferences. In those countries, however, sex-specific stopping behaviour may be observed: parents either stop childbearing once the desired number of sons has been reached or, otherwise, continue. Evidence for sex-specific stopping has been found in the same contexts as skewed sex ratios (Arnold Citation1997; Larsen et al. Citation1998; Clark Citation2000) and also in other contexts where skewed sex ratios and sex-selective abortion practices are absent, such as Türkiye (Altindag Citation2016) and Pakistan (Zaidi and Morgan Citation2016).

Sex composition preferences for children in Western countries are commonly studied by analysing either the actual stopping behaviour of parents or their intentions to stop. In the United States (US), couples with children of both sexes are significantly less likely to have another child (Wood and Bean Citation1977). Since (without intervention) the sex of offspring is random, such aggregate behaviour indicates a preference for one child of each sex (Wood and Bean Citation1977; Pollard and Morgan Citation2002), which has not changed much over time (Tian and Morgan Citation2015; Querin Citation2022). Preferences for a ‘sex mix’ are also found in some European countries, while other European countries show no clear preference for children’s sex and yet others show daughter preferences (Hank and Kohler Citation2000). The Nordic countries show consistent patterns of relatively stable preferences for a sex mix, and relative preferences for daughters are emerging in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden (Andersson et al. Citation2006). In Sweden, relative daughter preference has become more pronounced over time (Miranda et al. Citation2018).

Thus, while son preferences are dominant in many world regions, several Western countries have reported a preference for a sex mix or even a daughter preference. This leads to the intriguing question of whether these preferences are adjusted when confronted head-on, as is the case when international migrants from countries with son preference migrate to Western countries with diverging preferences. The question of whether migrants carry over the preferences of their origin countries to their new country of residence has been addressed in several studies, and evidence of this has been found, particularly among Asian migrants in different contexts, both in terms of elevated sex ratios at birth (Dubuc and Coleman Citation2007; Almond and Edlund Citation2008; Abrevaya Citation2009; Almond et al. Citation2013; González Citation2014; Kulu and González-Ferrer Citation2014; Ambrosetti et al. Citation2016; Mussino et al. Citation2018 [on Sweden]; Singh et al. Citation2010; Verropoulou and Tsimbos Citation2010) and in terms of differential stopping (Almond et al. Citation2013; Ost and Dziadula Citation2016).

Most of the aforementioned studies on migrant fertility have included only mothers, assuming that fathers are either less relevant for fertility decisions or exhibit the same preferences as mothers. For some immigrant groups, most marriages are with native individuals, who may have different preferences. Not accounting for differential intermarriage rates by sex and country of origin means falsely assuming that mothers alone make fertility decisions. Very few studies (e.g. Almond and Edlund Citation2008; Ambrosetti et al. Citation2016) have explicitly restricted their samples to endogamous immigrant couples, that is, couples in which both parents come from the same country of origin. Because intermarriage rates differ widely between different immigrant groups (e.g. Dribe and Lundh Citation2011 [on Sweden]; Lichter et al. Citation2015), not accounting for intermarriage can lead to biased estimates. Few studies on the fertility of female migrants have taken the father’s background into account (Andersson and Scott Citation2007; examples are Kahn Citation1988; Mussino and Strozza Citation2012). One study by Lillehagen and Lyngstad (Citation2018) showed that sex composition preferences became closer to a sex-mix or girl preference when an immigrant mother had a child with a native-born father. To my knowledge, only two studies have explicitly addressed fertility differentials between endogamous native and interethnic couples. While fertility levels were found to be similar among white native and most interethnic couples in the US (Fu Citation2008), Choi and Goldberg (Citation2018) showed that white women married to Black men experienced higher pregnancy risks, which the authors explained with a possible selection of women who prioritize marriage and family into these unions. The small number of studies on fertility patterns in interethnic unions is nevertheless surprising, given the otherwise broad interest in migrant fertility (see e.g. Andersson Citation2004 [on Sweden]; Kulu and González-Ferrer Citation2014) and interethnic marriage patterns (Chiswick and Houseworth Citation2011; Kalmijn Citation2012; Alba and Foner Citation2015; Lichter et al. Citation2015; Rodríguez-García Citation2015 for an overview).

Theoretical accounts of fertility and sex composition preferences

Sex-mix and homophily preferences in Western societies

Sex composition preferences for children are prevalent in many Western countries, often in the form of a desired sex mix. These preferences are assumed to be based on psychological rather than economic or social needs and are likely to be related to assumptions about the different character traits and interests of boys and girls. The preference of fathers for a son and the preference of mothers for a daughter are often mentioned together as being a reason for the ‘one-of-each’ preference (Williamson Citation1976; Gray et al. Citation2007; Hank Citation2007). Mills and Begall (Citation2010) call this the ‘homophily hypothesis’, where for heterosexual couples, the conflicting preferences of mothers and fathers will result in a one-of-each preference.

If a sex-mix preference is related to the father’s and mother’s homophily preferences, it is assumed that both parents will have a similar level of influence on fertility decisions. Theoretically, however, how much each partner influences the fertility decision can vary. Bargaining models state that the partner with the greater financial resources or the partner with a lower threshold for terminating the union (due, say, to a larger pool of potential partners) has greater bargaining power and hence greater influence on fertility decisions (Lundberg Citation2005).

Economic and socio-structural preferences in less developed countries

Scholars often assume that economic factors affect preferences for sons in less developed countries (e.g. Williamson Citation1976) if sons contribute more than daughters to household income in terms of labour. Also, in cases where daughters give their labour to their husband’s family on marriage, where daughters’ dowries are required, and where sons provide economic security and are the primary breadwinners in the parents’ old age, parents may prefer boys to girls. In addition to economic incentives, social structures can determine parental son preferences: this is the case in societies where sons are considered the male heirs who will continue the family line (Das Gupta et al. Citation2003).

Migrant fertility

The literature on migrant fertility discusses four major hypotheses concerning immigrant cultures and norms concerning fertility decisions: adaptation, socialization, selectivity, and disruption. These hypotheses originate from the literature on effects of migration on the fertility of internal migrants (see e.g. Goldstein Citation1973; Hervitz Citation1985; Kulu Citation2005) but have frequently been applied to the study of international migrant fertility (Singley and Landale Citation1998; e.g. Stephen and Bean Citation1992). Since these hypotheses do not distinguish between immigrants in endogamous and exogamous unions, many scholars have implicitly related the hypotheses to those in endogamous unions only.

Adaptation means that migrants will gradually adapt their fertility patterns to those in the new context. Adaptation may be a response to different economic conditions or different social and cultural environments (Goldstein Citation1973; Hervitz Citation1985). In contrast, the socialization hypothesis assumes that migrant fertility behaviour is determined by childhood socialization, since fertility preferences have been internalized early on and are not influenced by economic or social incentives (as suggested by Das Gupta et al. Citation2003). According to this hypothesis, the fertility patterns of the receiving context will be adopted only by the next generation (Stephen and Bean Citation1992; Singley and Landale Citation1998). Selectivity refers to the well-established fact that migrants are a select group: they may hold fertility preferences that differ from their context of origin and may choose a destination that matches their fertility preferences. The selectivity of migrants in terms of fertility patterns is likely to be related to observed characteristics (e.g. socio-economic status) and unobserved characteristics (e.g. fertility preferences). Lastly, disruption suggests that the process of migration is a shock to migrants’ fertility and thus a temporary drop in fertility will occur around the time of migration (Hervitz Citation1985). Because disruption refers to responses related to family migration, a process that does not apply to intermarried couples, it is outside the focus of this paper.

Migrants’ sex composition preferences for children

Although the four hypotheses are formulated about fertility levels, three out of the four (adaptation, socialization, and selectivity) can easily be applied to migrants’ sex composition preferences for children. Accordingly, adaptation would mean that migrants adapt not only to fertility levels in the receiving context but also to local sex preferences, such as the sex-mix and relative girl preferences seen in Sweden. It is plausible that the process of adaptation would lead to a weakening of son preferences after migration, through a breaking up of kinship networks and fewer economic incentives for having a son after settling into life in the new context. If, however, these preferences are deeply rooted in the origin culture, it is unlikely that immigrants will adapt to Swedish sex composition preferences. In that case, I would expect the socialization hypothesis to be more important for explaining migrants’ sex preferences for their offspring. Selectivity among migrants in terms of sex composition preferences would suggest that migrants are selected in terms of the preferences themselves, which may indeed contribute to reasons for migration (e.g. dissatisfaction with the patriarchal organization of the origin society).

Expected results based on intermarried migrants’ sex composition preferences

Based on the presentation of the theoretical accounts of fertility and sex composition preferences, I formulate two main competing expectations which I refer to in the discussion of the results: adaptation/bargaining vs socialization/homophily. I exclude selectivity from the formulation of expectations because selection processes are hard to theorize, not least since the selectivity of migrants and native individuals into intermarriage may differ based on migrants’ origins. Intermarried immigrants are often described as being positively selected based on observable characteristics (e.g. higher education; Dribe and Lundh Citation2008 [on Sweden]) and are likely to be selected in terms of unobserved characteristics, among them their fertility preferences. Fertility patterns that resemble those of the Swedish majority may therefore not be an outcome of intermarriage but, instead, be related to selection into intermarriage. Likewise, intermarried native individuals may be a select group whose fertility preferences diverge from those of the native majority. Even though I do not formulate strict expectations regarding selectivity, I still refer to that hypothesis when discussing the results. Results diverging from the theoretical expectations described next may be attributed to selectivity.

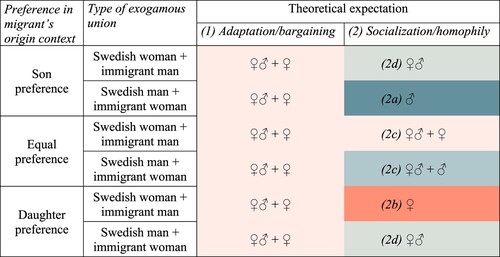

The adaptation/bargaining expectation. Intermarriage with native individuals is likely to play a key role in the process of preference adaptation for migrants. Despite having experienced the same childhood socialization as immigrants in endogamous unions, intermarried migrants may either: (1) be more likely to adapt to fertility preferences in the destination context because they are, for instance, exposed to native norms and values to a greater degree than migrants in endogamous unions; or (2) maintain the fertility preferences they acquired during childhood socialization but differ in realizing these preferences, for example, due to the native partner’s higher bargaining power. The higher bargaining power of the native spouse may give them a comparative advantage in making fertility decisions due to, for example, higher (potential) income or a larger pool of potential partners. Thus, under circumstances (1) and (2) we would expect sex composition preference patterns to resemble those of endogamous Swedish couples (relative girl preference). I summarize the theoretical expectations in . The adaptation/bargaining expectation is represented in column (1) and summarized as follows:

Intermarried migrants will adapt to local sex preferences, such as the Swedish sex-mix and relative girl preferences (all cells in , column (1)).

Figure 1 Theoretical expectations of sex composition preferences for children in intermarriages

= no preference or one-of-each preference;

The socialization/homophily expectation. In contrast to the adaptation/bargaining expectation, here I follow the socialization hypothesis discussed in the literature and expect that immigrants in both endogamous and exogamous unions will hold the same sex composition preferences as they were socialized in the same cultural environment. Yet, there may be differences when it comes to realizing these preferences due to the native partner’s preferences. In the adaptation/bargaining expectation, I expect all native Swedes to hold the same sex preferences for children, namely a sex-mix or relative girl preference. However, sex composition preferences are not necessarily the same for native Swedish men and women. In light of the homophily hypothesis discussed in the literature, I formulate the socialization/homophily expectation assuming that Swedish men will prefer sons and Swedish women will prefer daughters. For the sake of simplicity, I assume that homophily preferences are more important in explaining Swedish parents’ sex composition preferences for children than those of immigrants, for whom socialization is assumed to be more important (i.e. I assume uniform preferences for male and female immigrants from the same regions).

The socialization/homophily expectation is summarized in , column (2), and summarized as follows:

| (2) | Native Swedish men will prefer sons and native Swedish women will prefer daughters. Immigrants’ sex composition preferences will depend on socialization in their respective countries of origin. | ||||

This can be broken down into four sub-expectations, as shown in , column (2):

| (2a) | Immigrant women with son preferences will realize their son preference in unions with Swedish men. | ||||

| (2b) | Immigrant men with daughter preferences will realize their daughter preferences in unions with Swedish women. | ||||

| (2c) | Immigrants with equal preferences will realize their preferences in unions with Swedish men or women, and these unions may display patterns of a relative son or daughter preference. | ||||

| (2d) | Unions in which one partner holds a son preference and the other partner holds a daughter preference will display a joint preference for one child of each sex. | ||||

Data and method

The study is based on data from Sweden’s administrative registers that are maintained by Statistics Sweden. The sample consists of parents who were either cohabiting or formally married in the period 1990–2009 and had two common biological children (registered in Sweden). In Sweden, the propensity to marry is unrelated to the sex composition of children (Andersson and Woldemicael Citation2001); therefore, this analysis does not distinguish between formally married and non-married cohabiting parents. All second and third births in this study occurred in 1990–2009 (although first births could have occurred before 1990). By selecting couples with two common biological children, I disregarded transitions to first and second births in this study. The couples in the sample were thus likely to be more family oriented and have more stable relationships (whereas couples whose unions dissolved before or after a first child were disregarded), and the extent of selection may differ between endogamous and exogamous couples and between different migrant origins. Because the main purpose of this paper is to study sex composition preferences in intermarriage, the focus on transitions to third birth is appropriate. For an overview of fertility levels in endogamous and exogamous unions, see sections 1 and 2 of the supplementary material.

Partner information and parent–child information were linked using a unique identifier from the civil registration system. I excluded parents with previous children from other relationships and all twin births at parity two. Parents whose first child was born outside Sweden were included, but I conditioned on the second and third births occurring in Sweden. Third births occurring more than eight years after the previous birth were excluded. I define intermarriage in this paper as marriage or non-marital cohabitation between a native Swede (with Swedish-born parents) and an immigrant partner. I focused on adult immigrants only and excluded immigrants migrating as children (below age 12) from the sample, since the socialization experience is mixed for child migrants. For child migrants, I would assume that general adaptation of preferences and behaviour takes place independent of adaptation to a native spouse.

Model

To estimate the transition to third birth, I used piecewise constant exponential models (Blossfeld and Rohwer Citation2007), which make no assumptions about the functional form of the baseline hazard. The underlying idea of piecewise models is to split the period from the last birth into time intervals. It is assumed that the baseline hazard is constant in each of these intervals but can change between them. I estimated the following model:

(1)

(1) where, following Miranda et al. (Citation2018), I divided time since last birth (provided in months) into categories: 0–1, >1–1.5, >1.5–2, >2–2.5, >2.5–3, >3–4, >4–5, >5–6, and >6–8 years (observations are censored after more than eight years). As well as time since previous birth, I included a vector of controls (Xi) for the mother’s age, mother’s age squared, and parental age gap (in four categories: mother older (more than two years); same age (± two years); father three to six years older; and father seven or more years older). Moreover, I included period (in four categories: 1990–94, 1995–99, 2000–04, and 2005–09) and municipality of residence to account for differences in third-birth risks due to time and locality as well as selectivity of immigrants. The main variable of interest here is SEXCOM, which shows the sex composition of previous children (one boy and one girl (1B1G); two boys (2B); or two girls (2G)) by the individual’s immigrant status (immigrant or native Swede) and union type (exogamous or endogamous). The creation of this variable followed an interaction parametrization, which provides more straightforward conclusions than when comparing native individuals and immigrants in endogamous and exogamous couples separately (Fu Citation2008). The advantage is that the reference category (endogamous Swedish couples with a boy and a girl) remains the same for every group. Having a common reference category in each model makes it possible to identify the relative sex composition preferences as well as relative fertility levels of immigrants and Swedes in endogamous and exogamous unions, making the results easily comparable. For descriptive statistics on the main variables, see Table A3 supplementary material.

Observations were further censored on death, emigration, union dissolution, or the mother reaching age 46. The models were estimated separately by sex (i.e. one model included all unions between Swedish men and immigrant men in the indicated origin group and the other model included all unions between Swedish women and immigrant women from the indicated origin group). Piecewise constant exponential models assume proportionality of hazards of the explanatory variables. There are no strong signs of violation of the proportionality assumption.

Immigrants are a diverse group, not least when it comes to sex composition preferences. Based on the literature review, preferences can be expected to range from daughter preferences to strong son preferences, depending on the country of origin. I estimate hazard ratios (HRs) for some of the major regional immigrant-origin groups (Central and Eastern Europe; East Asia; and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA); see Table A4, supplementary material, for the entire list of countries). According to the literature, these three origin groups can be classified as son preference regions. Results for immigrants from Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa can be found in Figure A1, supplementary material.

In many cases, the birth of sons vs daughters can be considered random (Tian and Morgan Citation2015), and this feature is important when studying sex composition preferences. Randomness holds, however, only under certain assumptions, that is: (1) no sex-selective abortion at parities one and two; (2) no differential stopping behaviour at parity 1; and (3) no differences in union dissolution according to the sex composition of children. Nonetheless, even if the sex composition of children under these assumptions can be considered random, intermarriage cannot. In a further model, I, therefore, added education as an additional control variable to control for selection into intermarriage. Education was included as a categorical variable with three categories (maximum compulsory/ unknown; upper secondary; tertiary). Given the lack of information in the education register on many immigrants, I included missing cases in the compulsory category, because the majority of individuals whose educational background was not recorded were assumed to have undergone compulsory schooling at most (Statistics Sweden Citation2006).

Including education in the model is not unproblematic, however, as most potential control variables are endogenous and likely to be an outcome of intermarriage rather than a cause. This is particularly the case with income (Elwert and Tegunimataka Citation2016) but may also be the case with education. I nevertheless explore here how the estimates change when education is included as a control (e.g. Ost and Dziadula Citation2016), because education may be viewed as a proxy for unobservable characteristics or may have a causal effect on preferences. The overall results presented in display the HRs for Model 1 (without controlling for education) and Model 2 (controlling for education). The table clearly shows that including education does not change the HRs greatly.

Table 1 Relative third-birth risks by union type and sex composition of previous children, estimated from piecewise constant exponential models: Sweden, 1990–2009

To estimate the potential impact of unobserved selection, I used family fixed-effects models. I derived family (mother) IDs from the multigenerational register, allowing me to match the Swedish mothers and fathers in the sample to their own sisters and brothers, respectively. About 85 per cent of Swedish mothers and 78 per cent of Swedish fathers (born in 1942 and later) can be matched to their own mothers (with increasing coverage for later cohorts). In this data extraction, a full count of these grandparents exists only for parents born in 1942 or later. To account for cohort differences, I included a linear control for mother’s/father’s year of birth in the models. For these models, I ran stratified Cox regressions. Using the stratification option available for Cox models allows each family to have different baseline hazard functions (Allison Citation2009). Results are presented in .

Table 2 Relative third-birth risks in exogamous unions between immigrants and Swedish men or women, estimated from Cox proportional hazards models with and without family fixed effects: Sweden 1990–2009

Results

The overall results for endogamous Swedish couples, endogamous immigrant couples, and exogamous unions are displayed in . Endogamous Swedish couples display a clear one-of-each preference, as seen by the higher third-birth risks after two boys (HR 1.39) and two girls (HR 1.24) relative to the reference category of one boy and one girl (Model 1). The HRs also show a relative daughter preference, since the risk of having a third birth is significantly higher after two boys than after two girls. A relative daughter preference in third-birth risks has been found in previous studies (Andersson et al. Citation2006) and is supported by survey data (Miranda et al. Citation2018). This third-birth risk pattern can be interpreted as sex-specific stopping behaviour, where parents continue childbearing until the preferred number of daughters (at least one) is reached. Third-birth risks in endogamous immigrant unions are generally higher than in endogamous Swedish unions, independent of the sex composition of the two previous children. However, third-birth risks after two boys (HR 1.76) and after two girls (2.26) in particular, are higher than after one boy and one girl (1.62), which reveals a slight preference for having at least one child of each sex and a more pronounced preference for having at least one son. Interestingly, exogamous unions display different patterns of sex composition preference depending on whether the native partner is the father or mother. On one hand, unions between Swedish women and immigrant men generally exhibit higher third-birth risks than endogamous Swedish unions, and they display a preference for having at least one child of each sex. Third-birth risks after two boys compared with those after two girls are similar in size (1.83 vs 1.84), thus, no preference for either boys or girls is seen. On the other hand, unions between Swedish men and immigrant women generally show lower third-birth risks than endogamous Swedish unions where couples already have one boy and one girl. However, third-birth risks are higher after two children of the same sex, which reveals a one-of-each preference.

Origin groups

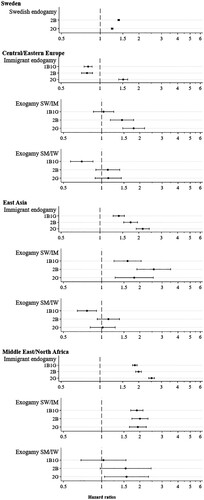

The three origin groups considered (Central and Eastern Europe; East Asia; MENA region) are all immigrant groups with prevalent son preferences in their origin regions. The HRs from various models are shown in , which also shows the patterns for endogamous Swedish couples as a comparison.

Figure 2 Relative third-birth risks by union type and sex composition of previous children, for three regional immigrant-origin groups, estimated from piecewise constant exponential models: Sweden, 1990–2009

Notes: Models control for mother’s age, mother’s age squared, parental age gap, period, and municipality fixed effects. 1B1G = one boy, one girl; 2B = two boys; 2G = two girls. Exogamy SW/IM = Swedish woman and immigrant man; Exogamy SM/IW = Swedish man and immigrant woman. Dashed vertical lines show the reference category: endogamous Swedish couples with a boy and a girl. Horizontal bars show 95 per cent confidence intervals. The x-axis is on a logarithmic scale.

The patterns for endogamous immigrant couples from Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, and the MENA region show relatively clear son preferences, as seen from the higher third-birth risks after two girls compared with two boys or one boy and one girl. The son preference pattern is most pronounced among Central and Eastern European immigrants, where third-birth risks are higher than in the reference category only after having two girls (HR 1.51). Endogamous couples from East Asia and the MENA region generally display higher third-birth risks compared with endogamous Swedish couples, and risks are highest among parents of two daughters. For intermarried couples, the most striking pattern is the relatively high third-birth risks in unions between Swedish women and immigrant men. In the case of unions with men from East Asia or the MENA region, the magnitude of the third-birth risk is more comparable to that of endogamous immigrant couples in the respective origin group than to that of endogamous Swedish couples. Unions between Swedish women and Central/Eastern European men, in contrast, exhibit higher third-birth risks than the corresponding immigrant couples. The opposite can be seen for unions between Swedish men and immigrant women from the three origins: their third-birth risks are of a magnitude comparable to or even lower than those of endogamous Swedish couples.

To summarize, sex composition preference patterns diverge markedly between the three origin groups and by whether the mother or father is the immigrant. Son preference patterns are discernible only among unions between Swedish women and immigrant men from Central/Eastern Europe (HR after two girls 1.79 compared with 1.04 and 1.45 after one boy and one girl or two boys, respectively), not among the other exogamous unions. These other exogamous unions indicate either no sex preference for children (unions between Swedish women and MENA men), a sex-mix preference (unions between Swedish men and Central/Eastern European women), or potentially even a relative daughter preference (Swedish–East Asian intermarriages with a migrant man or woman). In this final group, the higher HRs after two boys indicate a daughter preference rather than a son preference, resembling the pattern among endogamous Swedish couples rather than that of endogamous immigrant couples. Intermarriage between Swedish men and MENA women is rather rare and the large confidence intervals make it hard to see any pattern.

Family fixed-effects models

The results presented in the previous subsections show, overall, that Swedish women in relationships with immigrants from non-Western countries display higher third-birth risks than Swedish women in endogamous couples, independent of the sex composition of previous children. Swedish men married to immigrants from non-Western countries display overall lower third-birth risks than Swedish men in endogamous unions, independent of the sex composition of previous children (in most origin groups). These findings may be the result of a selection into intermarriage of Swedish women and men with high and low fertility preferences, respectively. One way to account for this kind of selection is to include family fixed effects in the models, that is, to use within-family variation to compare sisters and brothers in endogamous and exogamous unions. In family fixed-effects models, shared family background experiences and maternal factors are controlled for. To the extent that family factors contribute to shaping preferences about family sizes, family fixed-effects models allow us to assess the degree to which the higher and lower third-birth risks of Swedish women and men in exogamous unions are a result of their own childhood experience (and to some degree genetic endowments) and the degree to which they may be the result of the intermarriage itself or selection into intermarriage that is unrelated to family factors. The groups became relatively small when using this specification, therefore, I did not apply family fixed effects to the sex composition models by origin.

displays the third-birth risks for Swedish women and men in exogamous unions (relative to their Swedish counterparts in endogamous couples). As in the main models, unions with immigrants from Central/Eastern Europe, East Asia, Latin America, the MENA region, and sub-Saharan Africa are included. Intermarriages with immigrants from Western countries are not considered. Model 1 displays the overall third-birth risks for all Swedish women and men in exogamous unions in the sample. Intermarried Swedish women’s third-birth risks are about 50 per cent higher than the third-birth risks for those in endogamous Swedish unions, and intermarried Swedish men’s third-birth risks are about 10 per cent lower than third-birth risks for those in endogamous Swedish unions. In Model 2, the sample is restricted to sibling pairs only, to ensure that it is not the sample selection—having adult same-sex siblings with children—that mainly drives the results. Model 2 displays the third-birth risks of intermarried men and women without applying family fixed effects. The HRs for intermarried women are only marginally different; however, the HRs in the sample of brothers are slightly lower than in the overall sample. Model 3 shows the family-fixed-effects estimates for the entire sample. For women, the HRs are considerably reduced, although intermarried women’s third-birth risks are nevertheless about 22 per cent higher than those of their counterparts in endogamous unions. Selection based on family factors, such as preferences for larger families, is thus likely to explain in part the higher third-birth risks of intermarried women, but a positive association between intermarriage and third-birth risks remains. For men, however, third-birth risks are further reduced when including family fixed effects. For intermarried men, family factors thus appear to be unrelated to the third-birth risks they face; other factors, such as being intermarried or part of a selection effect unrelated to family factors, are more likely to explain the lower third-birth risks in this group.

Discussion

One of the most noticeable patterns from this research is that third-birth risks are generally high in intermarriages between Swedish women and immigrant men, whereas they tend to be low for unions between Swedish men and immigrant women. Third-birth risks are particularly high when Swedish women are in unions with immigrants from origin countries where endogamous immigrant couples also display high third-birth risks. Third-birth risks are, however, also higher for Swedish women in unions with Central/Eastern European men even though endogamous immigrant couples from these origin countries do not show particularly high third-birth risks. It is thus possible that Swedish women in unions with immigrants hold preferences for more children. Similarly, Choi and Goldberg (Citation2018) found higher pregnancy risks for white women married to Black men, which they explained by a potential selection of women into these unions. Unlike in Choi and Goldberg’s work, the data here allow me to account for selection based on shared family factors using family fixed effects. Findings show that the higher third-birth risks for women can indeed be partly explained by family factors, although an independent factor remains. Third-birth risks for intermarried Swedish men are, however, lower than those of Swedes in endogamous unions and much lower than those of immigrants in endogamous unions. Selection of the Swedish partner based on family factors does not explain this finding. It may thus be related to factors stemming from intermarriage itself, the selection of the immigrant partner, or a selection effect for the native partner that is unrelated to family factors.

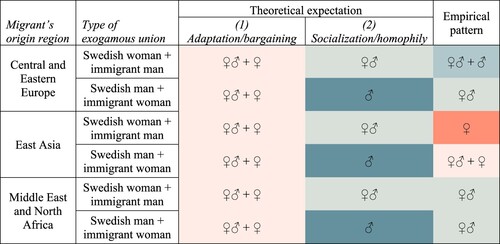

summarizes the expected and actual sex composition preference patterns for the three origin groups that are theoretically expected to be regions with son preference (as shown in the upper part of ). The expected sex composition patterns differ depending on the theoretical expectation and the immigrant’s origin group. On one hand, in the adaptation/bargaining expectation, I expect all immigrant–native intermarriages to adapt to local sex composition preferences and show patterns of a sex-mix and relative girl preference. In the socialization/homophily expectation, on the other hand, I expect patterns to differ depending on the immigrant’s origin and whether the male or female partner is the immigrant. However, because all three groups presented in the table are classified as regions with son preference (see e.g. Guilmoto Citation2015), all three origin groups are expected to show the same patterns.

Figure 3 Theoretical expectations and empirical patterns of sex composition preferences for children in intermarriages, for three regional immigrant-origin groups with son preference

= no preference or one-of-each preference;

Despite all three groups having the same theoretical patterns, they differ markedly in the empirically observed patterns, which range from relative son preferences (unions with Central/Eastern European men) to daughter preferences (unions with East Asian men). While the socialization/homophily expectation predicts son preferences in unions between Swedish men and immigrant women, relative son preferences are visible only in unions between Swedish women and Central/Eastern European men. (Relative) daughter preferences are visible in Swedish–East Asian unions, independent of the father or mother being the immigrant. Swedish–MENA unions show no sex composition preference, also independent of the father or mother being the immigrant.

Overall, the observed patterns do not match either of the expected patterns for these three origin groups. Yet, the patterns for endogamous immigrant couples largely match those observed in their respective origin countries. That intermarried immigrants’ patterns diverge from those of endogamous immigrant couples is well in line with Lillehagen and Lyngstad (Citation2018) who found that sex preferences for children in intermarriages rather resembled those of endogamous native couples. My findings nevertheless show that there is no general adaptation as could be assumed from Lillehagen and Lyngstad (Citation2018). In my study, the patterns neither show the expected general adaptation to Swedish sex composition preferences nor the alternatively expected gendered realization of preferences for sons or daughters in unions between immigrant men and Swedish women or immigrant woman and Swedish men. Since the patterns meet neither of the two expectations, they may rather reflect the selectivity of intermarried immigrants. Unobserved selection of immigrants—for instance on fertility preferences—cannot be accounted for in the models.

Limitations

While the findings of this study are very indicative in terms of deviation from expected patterns, there are clear shortcomings in the clarity of patterns. Different immigrant groups vary in size and in their propensity to marry a native spouse, which leads to small sample sizes and overlapping confidence intervals for some of the groups.

Scholars focusing on migrant fertility may object that length of stay in the receiving country is important for explaining fertility adaptation (see e.g. Andersson Citation2004), something the main specifications here do not account for. The reasons for not including years since migration in the main specification are that native Swedes are included in every model and that the unit of analysis is the couple. Therefore, no reasonable value of years since migration can be assigned to the native partner. I address this objection in two ways. First, by excluding immigrants migrating as children from all models, I account for major differences in exposure to majority population norms, which assumedly are most influential during childhood socialization. Second, to assess whether or not the patterns change when years since migration is included in the models, I ran robustness analyses for immigrants only (available from the author on request). Despite the overall size of the coefficients being slightly affected in some of the specifications, the sex composition patterns were not affected. Therefore, I am confident that the main models are robust to immigrants’ different lengths of stay.

Conclusions

The particular focus of this study was sex composition preferences for children in immigrant–native intermarriages in Sweden. While immigrant fertility has attracted a lot of interest in terms of research in recent decades, the fertility patterns of intermarried couples have received relatively little attention. The limited interest in intermarried couples’ fertility patterns (Choi and Goldberg Citation2018; except for Fu Citation2008; Lillehagen and Lyngstad Citation2018) is surprising, given the high level of general interest in research on intermarriage. The findings of this study showed that while the fertility patterns of endogamous immigrant couples in Sweden were largely in line with theory and previous research, those of intermarried couples were much more diverse than theoretically expected. The patterns in most intermarriages deviated from those of endogamous immigrant couples, suggesting that intermarried immigrants are a select group. Native partners, in turn, were equally likely to be a select group in terms of partner and childbearing choices. Selection based on family-of-origin factors indeed explains part of the higher third-birth risks for intermarried Swedish women. One of those factors could be growing up in a larger family, which might lead to a preference for partners with similar fertility preferences. Intermarried native men’s lower third-birth risks cannot, however, be explained by selection based on family-of-origin characteristics. One potential explanation is that selection of men into intermarriages is less related to fertility preferences and family orientation and more related to the wife’s characteristics, as suggested in the literature (Esteve et al. Citationforthcoming).

To conclude, the findings of this study call for future research to account for diversity both empirically, by distinguishing endogamous and exogamous migrant couples, and theoretically, by theorizing on the exogamous groups’ distinct preferences and behaviour. Predictions based on the most common hypotheses on migrant fertility and sex preferences for children failed to align with the empirical patterns observed. Future research will therefore require much more theorizing on fertility choices in intermarriages.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (488.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Annika Elwert is based in the Department of Sociology, Lund University, and also affiliated with the Centre for Economic Demography. Most of the work associated with this paper was conducted at the Department of Economic History and Centre for Economic Demography at Lund University.

2 Please direct all correspondence to Annika Elwert, Box 114, 221 00 Lund, Sweden; or by E-mail: [email protected].

3 Acknowledgements: This study forms part of the Male Fertility and Parenthood project (Principal investigator: Maria Stanfors, Lund University). The author is grateful to Valentine Becquet, Martin Dribe, Christofer Edling, Ognjen Obucina, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

References

- Abbasi-Shavazi, Mohammad Jalal and Peter McDonald. 2000. Fertility and multiculturalism: Immigrant fertility in Australia, 1977-1991, International Migration Review 34(1): 215–242. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676018

- Abrevaya, Jason. 2009. Are there missing girls in the United States? Evidence from birth data, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1(2): 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.1.2.1

- Adsera, Alicia and Ana Ferrer. 2014. Factors influencing the fertility choices of child immigrants in Canada, Population Studies 68(1): 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2013.802007

- Alba, Richard and Nancy Foner. 2015. Mixed unions and immigrant-group integration in North America and Western Europe, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 662(1): 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716215594611

- Allison, Paul David. 2009. Fixed Effects Regression Models. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Almond, Douglas and Lena Edlund. 2008. Son-biased sex ratios in the 2000 United States Census, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105(15): 5681–5682. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0800703105

- Almond, Douglas, Lena Edlund, and Kevin Milligan. 2013. Son preference and the persistence of culture: Evidence from South and East Asian immigrants to Canada, Population and Development Review 39(1): 75–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00574.x

- Altindag, Onur. 2016. Son preference, fertility decline, and the nonmissing girls of Turkey, Demography 53(2): 541–566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0455-0

- Ambrosetti, Elena, Livia Elisa Ortensi, Cinzia Castagnaro, and Marina Attili. 2016. Sex imbalances at birth in migratory context: Evidence from Italy, GENUS 71(2-3): 29–51. https://www.jstor.org/stable/genus.71.2-3.29

- Andersson, Gunnar. 2004. Childbearing after migration: Fertility patterns of foreign-born women in Sweden, International Migration Review 38(2): 747–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00216.x

- Andersson, Gunnar and Kirk Scott. 2007. Childbearing dynamics of couples in a universalistic welfare state, Demographic Research 17: 897–938. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2007.17.30

- Andersson, Gunnar and Gebremariam Woldemicael. 2001. Sex composition of children as a determinant of marriage disruption and marriage formation: Evidence from Swedish register data, Journal of Population Research 18(2): 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03031886

- Andersson, Gunnar, Karsten Hank, Marit Rønsen, and Andres Vikat. 2006. Gendering family composition: Sex preferences for children and childbearing behavior in the Nordic countries, Demography 43(2): 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2006.0010

- Arnold, Fred. 1997. Gender Preferences for Children: DHS Comparative Studies No. 23. Calverton, MD: Macro International Inc.

- Bevelander, Pieter. 2010. The immigration and integration experience, the case of Sweden, in Uma Anand Segal, Doreen Elliott and Nazneen S. Mayadas (eds), Immigration Worldwide: Policies, Practices, and Trends. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 286–302.

- Blossfeld, Hans-Peter and Götz Rohwer. 2007. Event History Analysis with Stata. Hove: Psychology Press.

- Boer, Andrea den and Valerie Hudson. 2017. Patrilineality, son preference, and sex selection in South Korea and Vietnam, Population and Development Review 43(1): 119–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12041

- Bongaarts, John. 2013. The implementation of preferences for male offspring, Population and Development Review 39(2): 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00588.x

- Chiswick, Barry R. and Christina A. Houseworth. 2011. Ethnic intermarriage among immigrants: Human capital and assortative mating, Review of Economics of the Household 9(2): 149–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-010-9099-9

- Choi, Kate H. and Rachel E. Goldberg. 2018. Fertility behavior of interracial couples, Journal of Marriage and Family 80(4): 871–887. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12483

- Clark, Shelley. 2000. Son preference and sex composition of children: Evidence from India, Demography 37(1): 95–108. https://doi.org/10.2307/2648099

- Das Gupta, Monica, Jiang Zhenghua, Li Bohua, Xie Zhenming, Woojin Chung, and Bae Hwa-Ok. 2003. Why is son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? A cross-country study of China, India and the Republic of Korea, The Journal of Development Studies 40(2): 153–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331293807

- Dribe, Martin and Christer Lundh. 2008. Intermarriage and immigrant integration in Sweden: An exploratory analysis, Acta Sociologica 51(4): 329–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699308097377

- Dribe, Martin and Christer Lundh. 2011. Cultural dissimilarity and intermarriage. A longitudinal study of immigrants in Sweden 1990–2005, International Migration Review 45(2): 297–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2011.00849.x

- Dubuc, Sylvie and David Coleman. 2007. An increase in the sex ratio of births to India-born mothers in England and Wales: Evidence for sex-selective abortion, Population and Development Review 33(2): 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2007.00173.x

- Elwert, Annika and Anna Tegunimataka. 2016. Cohabitation premiums in Denmark: Income effects in immigrant–native partnerships, European Sociological Review 32(3): 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcw018

- Esteve, Albert, Annika Elwert and Ewa Batyra. forthcoming. Gender asymmetries in cross-national couples. Population and Development Review.

- Fu, Vincent Kang. 2008. Interracial-interethnic unions and fertility in the United States, Journal of Marriage and Family 70(3): 783–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00521.x

- Goldstein, Sidney. 1973. Interrelations between migration and fertility in Thailand, Demography 10(2): 225–241. https://doi.org/10.2307/2060815

- González, Libertad. 2014. Missing Girls in Spain, Barcelona Graduate School of Economics Working Papers. Available: http://www.barcelonagse.eu/file/2888/download?token=_sdSuF-w (accessed: 29 September 2017).

- Gray, Edith, Rebecca Kippen, and Ann Evans. 2007. A boy for you and a girl for me: Do men want sons and women want daughters?, People and Place 15(4): 1–8.

- Guilmoto, Christophe Z. 2009. The sex ratio transition in Asia, Population and Development Review 35(3): 519–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2009.00295.x

- Guilmoto, Christophe Z. 2015. The masculinization of births. Overview and current knowledge, Population 70(2): 185–243. https://doi.org/10.3917/popu.1502.0201

- Hank, Karsten. 2007. Parental gender preferences and reproductive behavior: A review of the recent literature, Journal of Biosocial Science 39(5): 759–767. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932006001787

- Hank, Karsten and Hans-Peter Kohler. 2000. Gender preferences for children in Europe: Empirical results from 17 FFS countries, Demographic Research 2(1). https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2000.2.1

- Hervitz, Hugo M. 1985. Selectivity, adaptation, or disruption? A comparison of alternative hypotheses on the effects of migration on fertility: The case of Brazil, International Migration Review 19(2): 293–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791838501900205

- Kahn, Joan R. 1988. Immigrant selectivity and fertility adaptation in the United States, Social Forces 67(1): 108. https://doi.org/10.2307/2579102

- Kalmijn, Matthijs. 2012. The educational gradient in intermarriage: A comparative analysis of immigrant groups in the United States, Social Forces 91(2): 453–476. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sos128

- Kulu, Hill. 2005. Migration and fertility: Competing hypotheses re-examined, European Journal of Population 21(1): 51–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-005-3581-8

- Kulu, Hill and Amparo González-Ferrer. 2014. Family dynamics among immigrants and their descendants in Europe: Current research and opportunities, European Journal of Population 30(4): 411–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-014-9322-0

- Larsen, Ulla, Woojin Chung, and Monica Das Gupta. 1998. Fertility and son preference in Korea, Population Studies 52(3): 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000150496

- Lichter, Daniel T., Zhenchao Qian, and Dmitry Tumin. 2015. Whom do immigrants marry? Emerging patterns of intermarriage and integration in the United States, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 662(1): 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716215594614

- Lillehagen, Mats and Torkild Hovde Lyngstad. 2018. Immigrant mothers’ preferences for children’s sexes: A register-based study of fertility behaviour in Norway, Population Studies 72(1): 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2017.1421254

- Lundberg, Shelly. 2005. Sons, daughters, and parental behaviour, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 21(3): 340–356. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/gri020

- Mayer, Jochen and Regina T. Riphahn. 2000. Fertility assimilation of immigrants: Evidence from count data models, Journal of Population Economics 13(2): 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001480050136

- Mills, Melinda and Katia Begall. 2010. Preferences for the sex-composition of children in Europe: A multilevel examination of its effect on progression to a third child, Population Studies 64(1): 77–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720903497081

- Miranda, Vitor, Johan Dahlberg, and Gunnar Andersson. 2018. Parents’ preferences for sex of children in Sweden: Attitudes and outcomes, Population Research and Policy Review 37(3): 443–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-018-9462-8

- Mussino, Eleonora and Salvatore Strozza. 2012. The fertility of immigrants after arrival: The Italian case, Demographic Research 26: 99–130. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2012.26.4

- Mussino, Eleonora, Vitor Miranda, and Li Ma. 2018. Changes in sex ratio at birth among immigrant groups in Sweden, GENUS 74(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-018-0036-8

- Mussino, Eleonora, Vitor Miranda, and Li Ma. 2019. Transition to third birth among immigrant mothers in Sweden: Does having two daughters accelerate the process?, Journal of Population Research 36(2): 81–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-019-09224-x

- Ost, Ben and Eva Dziadula. 2016. Gender preference and age at arrival among Asian immigrant mothers in the US, Economics Letters 145: 286–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2016.06.025

- Pollard, Michael S. and S. Philip Morgan. 2002. Emerging parental gender indifference? Sex composition of children and the third birth, American Sociological Review 67(4): 600–613. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088947

- Querin, Federica. 2022. Preferences for a mixed-sex composition of offspring: A multigenerational approach, Population Studies 76(1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2022.2027003

- Ritchie, Hannah. 2019. How does the sex ratio at birth vary across the world? Available: https://ourworldindata.org/sex-ratio-at-birth (accessed: 20 January 2022).

- Rodríguez-García, Dan. 2015. Intermarriage and integration revisited: International experiences and cross-disciplinary approaches, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 62(1): 8–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716215601397

- Singh, Narpinder, Are Hugo Pripp, Torkel Brekke, and Babill Stray-Pedersen. 2010. Different sex ratios of children born to Indian and Pakistani immigrants in Norway, BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 10(1): 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-10-40

- Singley, Susan G. and Nancy S. Landale. 1998. Incorporating origin and process in migration-fertility frameworks: The case of Puerto Rican women, Social Forces 76(4): 1437–1464. https://doi.org/10.2307/3005841

- Sobotka, Tomáš. 2008. Overview chapter 7: The rising importance of migrants for childbearing in Europe, Demographic Research 19: 225–248. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.9

- Sobotka, Tomáš and Éva Beaujouan. 2014. Two is best? The persistence of a two-child family ideal in Europe, Population and Development Review 40(3): 391–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2014.00691.x

- Statistics Sweden. 2006. Evalvering av utbildningsregistret [Evaluation of the education register]. Available: https://www.scb.se/statistik/_publikationer/be9999_2006a01_br_be96st0604.pdf (accessed: 14 August 2017).

- Stephen, Elizabeth Hervey and Frank D. Bean. 1992. Assimilation, disruption and the fertility of Mexican-origin women in the United States, International Migration Review 26(1): 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791839202600104

- Tian, Felicia F. and S. Philip Morgan. 2015. Gender composition of children and the third birth in the United States, Journal of Marriage and Family 77(5): 1157–1165. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12218

- Verropoulou, Georgia and Cleon Tsimbos. 2010. Differentials in sex ratio at birth among natives and immigrants in Greece: An analysis employing nationwide micro-data, Journal of Biosocial Science 42(3): 425–430. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932009990599

- Williamson, Nancy E. 1976. Sons or Daughters: A Cross-Cultural Survey of Parental Preferences. Beverley Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Wood, Charles H. and Frank D. Bean. 1977. Offspring gender and family size: Implications from a comparison of Mexican Americans and Anglo Americans, Journal of Marriage and the Family 39(1): 129–139. https://doi.org/10.2307/351069

- Zaidi, Batool and S. Philip Morgan. 2016. In the pursuit of sons: Additional births or sex-selective abortion in Pakistan?, Population and Development Review 42(4): 693–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12002