ABSTRACT

Aims

This survey aimed to explore real-world physician experiences and treatment satisfaction with fast-acting insulin aspart (faster aspart) in clinical practice across Europe and Canada.

Materials and methods

An online web-based survey was used for physicians treating people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. General practitioners and specialists, with experience using faster aspart, were interviewed.

Results

A total of 191 physicians participated in the survey. Most of their patients (68% of those with T1D and 63% of those with T2D) were previously treated with another mealtime insulin before switching to faster aspart. At the time of initiating faster aspart, nearly half of patients had an HbA1c level between 7.5% (59 mmol/mol) and 8.5% (69 mmol/mol). The main prescription drivers for faster aspart, versus other mealtime insulins, were faster onset of action, improved postprandial glucose (PPG) control, and dosing flexibility. Most physicians were more satisfied with faster aspart than other mealtime insulins regarding at-meal (66%) and post-meal (71%) dosing flexibility, improved PPG levels (66%), and onset of action (61%). Main reasons for not prescribing faster aspart included a good response to current treatment (76%) or patient reluctance to switch (57%). Overall, 12% of patients discontinued faster aspart, for reasons including concerns of hypoglycemia (17%), poor adherence (17%), and level of patient co-pay (17%). More than half of physicians had fewer concerns regarding postprandial hyperglycemia, and were more confident in their patients reaching their HbA1c target with faster aspart than with other mealtime insulins.

Limitations

The findings of this survey are based heavily on physicians’ experiences, and could therefore be subject to recall bias.

Conclusions

Reported physician and patient experiences of using faster aspart have been positive, and better PPG control and increased dosing flexibility are expected to improve glycemic management.

Introduction

Bolus insulin therapy aims to improve glycemic control [Citation1–Citation3] by mimicking physiological insulin secretion as closely as possible in response to a meal. Reducing postprandial hyperglycemia is an essential but challenging component for meeting recommended HbA1c target levels [Citation1,Citation3,Citation4].

Rapid-acting insulin analogs, including insulin lispro [Citation5,Citation6] insulin aspart [Citation7,Citation8], and insulin glulisine [Citation9,Citation10], are engineered with a reduced tendency to aggregate, thereby allowing more rapid dissociation and absorption compared with regular human insulin [Citation11–Citation14]. Rapid-acting insulin analogs are more effective in lowering postprandial glucose (PPG) levels than regular human insulin, primarily due to their faster onset and shorter duration of action [Citation15]. However, due to their relatively slow absorption, they are unable to fully mimic physiological insulin secretion patterns.

Fast-acting insulin aspart (faster aspart) is an ultra-fast-acting mealtime insulin that comprises conventional insulin aspart in a new formulation with the excipients niacinamide and L-arginine, to achieve faster absorption [Citation16,Citation17]. The pharmacological profile of faster aspart has been shown to be different to insulin aspart, in that onset of action occurred earlier, early glucose-lowering effect was 74% greater, and offset of glucose-lowering effect occurred earlier versus insulin aspart [Citation18]. The clinical impact of faster aspart was evaluated in the onset clinical program in people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) [Citation19,Citation20] and type 2 diabetes (T2D) [Citation21,Citation22], where it showed promising results in terms of HbA1c reduction and control of PPG excursions, without an increased risk of overall hypoglycemia compared with insulin aspart. However, due to its recent regulatory approval and availability, there are limited real-world data investigating the use of faster aspart in clinical practice. Real-world studies are useful because they enable assessment of a wider, more representative, disease population in terms of age, comorbidities, treatment adherence, and other important factors.

This survey aimed to gain an understanding of the characteristics of patients initiating faster aspart and the characteristics, experiences, perceptions, and behaviors of a broad range of physicians who have used faster aspart for the treatment of T1D and T2D, in selected European countries and Canada.

Methods

Survey design and participants

This was a previously tested online web-based survey, conducted from 19 February 2018 to 9 April 2018 and completed by a broad range of physicians (general practitioners [GPs] and specialists) from the UK, Denmark, Switzerland, Finland, and Canada who were treating people with diabetes. Exclusion criteria included physicians who were not treating any people with multiple daily insulin injections (MDI) (i.e. ‘basal plus’ or ‘full basal–bolus’), who were treating <2 people with diabetes with faster aspart, or who initiated first patient on faster aspart <3 months prior to the survey (Switzerland, Canada, and Denmark), <4 months prior to the survey (Finland), or <8 months prior to the survey (UK). The differences in the dates were due to the different launch dates for faster aspart in these countries. ‘Basal plus’ was defined as basal insulin plus one or two mealtime insulins with or without oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs). ‘Full basal–bolus’ was defined as basal insulin plus three mealtime insulin injections with or without OADs. The survey included 33 questions (Table S1).

Informed consent process/Confidentiality/Data protection

Respondents were informed that data would be stored securely on IQVIA servers, in accordance with applicable data protection laws, only for as long as necessary, for the purposes of use outlined. Respondent’s personal details were anonymized and responses were confidential. Respondents provided their consent to waive confidentiality in relation to adverse events so that their name and contact details could be forwarded to the sponsor’s pharmacovigilance department, without linking the name in any way to the responses given during the interview.

Survey questionnaire development and pre-testing

The survey questionnaire contained the main survey, along with screener questions, to ensure that only experienced physicians relevant to the study were included. The questionnaire was tested, to ensure the questions were clear and non-ambiguous, in 10 cognitive-debriefs (two per country, one with a GP and one with a specialist [except for Denmark, where GPs usually do not prescribe mealtime insulin, so both were with a specialist]) via telephone and online (duration ~ 40 minutes), and respondent feedback was incorporated. These data are not published but information can be provided upon request on the cognitive debriefs.

Recruitment methodology

The OneKey and Medical Booking System (MEBOS) database (maintained by IQVIA) was used to identify potential participants; an e-mail was sent to them containing a unique link (mapped to a respondent ID) providing access to screener questions and then the main questionnaire if the physician passed the screener test. Once the survey was submitted, it could not be taken again. In the UK, 433 physicians were screened out from 6110 contacted; in Finland, 39 were screened out of 220; in Denmark, 35 were screened out of 268; in Switzerland, 29 were screened out of 517; and, in Canada, 308 were screened out of 1594 contacted.

Survey administration

Responses were captured using computer-assisted web interview methodology, using a unique link shared with each respondent, and stored in a proprietary IQVIA Medical Radar Pharmaceutical Interviews (MERPHIN) database. Respondents had to answer each question to be able to move to the next. After submission, a ‘complete’ tag was assigned to all completed surveys. Incentives were provided to respondents using IQVIA’s Healthcare (Research) Partner Program (HPP) incentive scheme.

Analysis

Only fully completed, surveys were analyzed. The sample size represented the population under study, with a mix of GPs and specialists across all countries. To study the difference in responses between GPs and specialists, significance testing was done at a 95% confidence level. For some questions, significance testing at a 95% confidence level was calculated between T1D and T2D to study the differences in physician responses for the two patient groups.

Results

Physician profiles

A total of 191 physicians participated in the survey: 89 from Europe and 102 from Canada. Overall, 129 participants (68%) were GPs and 62 (32%) were specialists (diabetologists/endocrinologists). Denmark and Switzerland had more specialist participants (n = 11/15; 73% and n = 9/13; 69%, respectively) and Canada more GP participants (n = 89/102; 87%).

The majority of physicians (63%) treated >40 patients with T1D per month and more than half (55%) treated >80 patients with T2D per month. Physicians had been prescribing faster aspart for a mean of 7 months; longer in the UK (10 months) and for a shorter time in Switzerland (5 months), Denmark (6 months), and Finland (6 months). This is a reflection of the different launch dates for faster aspart in these countries. The majority of physicians (~70%) had treated or were currently treating between two and 15 T1D patients and between two and 15 T2D patients with faster aspart. More than half (52%) of physicians agreed that controlling PPG at every meal was important. This was considered particularly important in Finland (n = 8/13; 62% of physicians) but less important in Switzerland (n = 4/13; 31%) and Denmark (n = 5/15; 33%).

Characteristics of patients initiating faster aspart

The characteristics of patients starting treatment with faster aspart are shown in . Data from 177 physicians for their T1D patient caseload, and 166 physicians for their T2D patient caseload, were included in the survey. Of the patients prescribed faster aspart for the first time, 57% of those with T1D were ≤40 years of age, while 56% of those with T2D were 41–65 years of age. Patients with T2D had a higher body mass index (BMI) (63% BMI >30 kg/m2) than patients with T1D (36% BMI >30 kg/m2) ().

Table 1. Patient characteristics at faster aspart initiation.

As expected, the majority of patients (69%) with T1D were administering insulin MDI at the time of starting treatment with faster aspart (). Patients with T2D were administering ‘full basal–bolus’ (21%), ‘basal plus’ (15%), basal insulin ± OADs (18%), or OADs alone (18%) prior to initiating faster aspart ().

Most patients (68% of those with T1D and 63% of those with T2D) were previously treated with another mealtime insulin before switching to faster aspart (). Of those switching from another mealtime insulin, 42% of patients with T1D and 37% of patients with T2D had a change in the timing or dose of their mealtime insulin when they started faster aspart (). Specialists had more patients switching to faster aspart (80% and 69% of patients with T1D and T2D, respectively) compared with GPs (62% and 60%). A greater number of patients with T1D and T2D had switched from another mealtime insulin to faster aspart in Denmark (81% and 92%, respectively) and in Finland (97% and 86%) compared with other countries. shows data for patients switching from another mealtime insulin across all countries included in the survey.

Table 2. Patients switching to faster aspart from another mealtime insulin.

Faster aspart was mostly prescribed due to inadequate HbA1c control in patients initiating faster aspart (30%) or switching to faster aspart (27%) from another mealtime insulin (). The second and third most influential reasons for initiating or switching to faster aspart were potential problems of hypoglycemia or patient concerns about postprandial hyperglycemia ().

At the time of initiating faster aspart, nearly half of patients had an HbA1c level between 7.5% (59 mmol/mol) and 8.5% (69 mmol/mol), and most patients with T1D and T2D were considered by the physician to have good adherence to their diabetes therapy (68% and 59%) (). Physicians reported that 52% of their patients with T1D or T2D on faster aspart were able to reach their target HbA1c level, taking an average of four visits and 3–4 phone calls over a period of 4–5 months, with an average daily dose of 39 and 45 units, respectively. Overall, the main reasons for not achieving target HbA1c in the remaining 48% of patients were recent initiation of treatment (33%), low adherence (24%), and poor self-management (23%).

The preferred intensification alternative in patients with T2D, if they had not been prescribed faster aspart, was ‘up-titration of either basal or bolus insulin’ (reported in 57% of patients). Most physicians (78%) had access to an on-site diabetes nurse or educator to help start insulin therapy in insulin-naïve patients, with 95% of specialists having access. Access to this support varied between countries, ranging from 67% in Canada to 98% in the UK.

Prescription pattern, drivers, and barriers with faster aspart

The majority (70%) of physicians introduced and prescribed faster aspart to patients during the same visit (84% [specialists], 63% [GPs]). For the remainder, it took an average of two visits or 2 months on average before faster aspart was prescribed. Overall, 27% of physicians made changes to other diabetes medication after prescribing faster aspart (in most cases [76%] altering the medication dose) and, overall, more GPs (32%) made changes than specialists (16%).

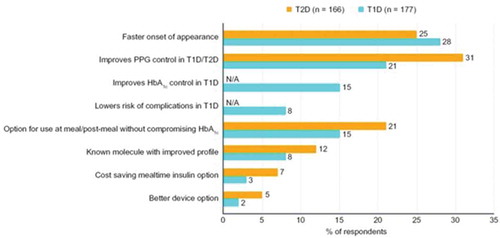

When physicians were questioned about their main drivers for using faster aspart in people with T1D or T2D, these were faster onset of action (in 28% and 25% of respondents, respectively), improved PPG control (21% and 31% of respondents), and dosing flexibility (the option to be used at meal and post-meal when needed; 15% and 21% of respondents) (). Prescription drivers were similar for both GPs and specialists.

Similarly, when asked to differentiate faster aspart from other mealtime insulins, 90% of physicians agreed that faster onset of action was the main differentiator, with 84% and 85%, respectively, feeling that mealtime dosing flexibility at meal or up to 20 minutes after starting eating were the major differentiators, and 68% that better PPG control and 57% that better control of HbA1c in patients with T1D were the main differentiators. Physicians agreed that the least differentiating factor was cost savings (30%).

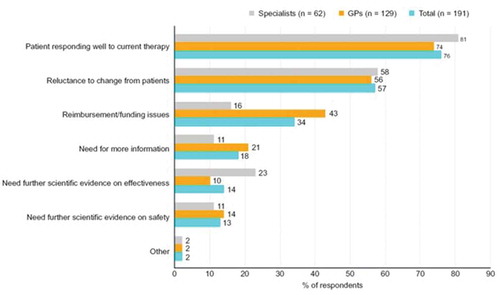

The most cited reasons for not prescribing faster aspart included a good response to current treatment (76%), patient reluctance to switch (57%), or perceived non-reimbursement/funding issues (34%) ().

Titrating and discontinuation of faster aspart

The majority of physicians (76% of those treating patients with T1D and 79% of those treating T2D) were confident in up-titrating faster aspart. More than half of those treating T1D (56%) or T2D (52%) were confident in their patients’ ability to up-titrate the dose. The majority of specialists (68% of those treating T1D and 63% of those treating T2D) were confident in their patients’ ability to self-titrate faster aspart. Around half of the GPs questioned (50% of those treating T1D and 48% of those treating T2D) were confident in their patients’ ability to self-titrate.

On average, 12% of patients discontinued treatment with faster aspart, usually within 3 months of starting treatment (68%). Main reasons for treatment discontinuation were concerns of hypoglycemia (17%), poor adherence (17%), level of patient co-pay (17%), not achieving HbA1c target (16%), and difficulties with self-management (15%). Other reasons are outlined in Table S2. Level of patient co-pay was particularly relevant in Canada (27%), but not considered important in Switzerland (1%), Finland (4%), or Denmark (6%).

Physician satisfaction with faster aspart

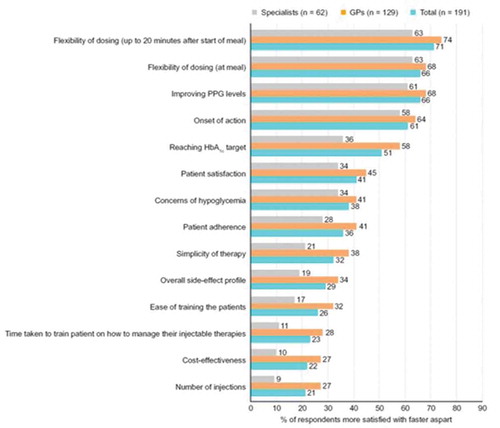

The majority of physicians were more satisfied with faster aspart than other mealtime insulins with regard to flexibility of dosing (at meal and up to 20 minutes after starting meal; 66% and 71%, respectively), improved PPG levels (66%), onset of action (61%), and reaching HbA1c target (51%) (). For other attributes, most physicians expressed equal satisfaction with faster aspart and other mealtime insulins. GPs expressed more satisfaction than specialists regarding reaching HbA1c target with faster aspart (58% vs 36%).

Physician and patient concerns with faster aspart

More than half (54%) of physicians were less concerned with faster aspart than with other mealtime insulin formulations regarding postprandial hyperglycemia. Hypoglycemia was less of a concern with faster aspart than with other mealtime insulins for 41% of physicians and an equal concern for both faster aspart and other mealtime insulins for 47%. Concern about allergic reactions was expressed equally for faster aspart and other mealtime insulins by most physicians (76%).

According to the participating physicians, difficulty in taking the dose at the right time was a concern that many patients (45%) expressed less with faster aspart than with other mealtime insulins. Most physicians (72%) mentioned that patients were more confident in reaching their HbA1c target with faster aspart compared with other mealtime insulins. In Switzerland and Finland, patient confidence was even higher (93% and 85%, respectively), whereas, in Denmark, patient confidence was a little lower (47%).

Discussion

Results presented provide insight into the real-world use of faster aspart in Europe and Canada. Data are based on experiences, perceptions, and behaviors of a broad range of physicians managing patients with diabetes, and the results are reflective of a large number of patients receiving faster aspart.

Most patients were previously treated with another mealtime insulin before switching to faster aspart. The main prescription drivers and differentiators for faster aspart compared with other mealtime insulins were faster onset of action, improved PPG control, and dosing flexibility. This is reflective of the pharmacological attributes of faster aspart and the results from the phase 3 onset faster aspart clinical trial program [Citation19–Citation23]. A pooled analysis of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of faster aspart in T1D demonstrated earlier onset of action, 74% greater early glucose-lowering effect, and earlier offset of glucose-lowering effect for faster aspart versus insulin aspart [Citation18]. Results from the onset 1 and onset 8 trials, in adults with T1D, demonstrated superiority for mealtime faster aspart versus insulin aspart with regard to the 2-hour and 1-hour PPG increments, respectively, after a meal test [Citation19,Citation23]. Similarly, results from onset 2, in adults with T2D receiving basal insulin and OADs, also demonstrated a significant improvement in 1-hour PPG increment following a meal test when adding faster aspart versus insulin aspart [Citation21]. In onset 1 and onset 8, non-inferiority for the change from baseline in HbA1c was demonstrated for both mealtime and post-meal faster aspart versus insulin aspart in patients with T1D [Citation19,Citation23].

More than half of physicians were more concerned about postprandial hyperglycemia with other mealtime insulin formulations than with faster aspart, and hypoglycemia was either of equal or more concern with other mealtime insulins compared with faster aspart. According to physician responses, difficulty in taking the dose at the right time was a concern many patients expressed more with other mealtime insulins than with faster aspart, which is likely to be reflective of the pharmacological differences between these formulations. This may also partly explain why physicians had more confidence in their patients reaching their HbA1c target with faster aspart compared with other mealtime insulins. Despite HbA1c target levels being difficult to achieve in clinical practice, physicians who took the survey reported that more than half of their patients on faster aspart reached their target.

The survey found that dosing flexibility around meals was important to physicians and patients. Although post-meal dosing cannot be recommended, it may be suitable for use in certain patient populations who require dosing flexibility in their daily lives. Flexibility of dosing offers diabetes patients the freedom to live a normal life, with fewer worries about constant meal planning, resulting in a better quality of life. In certain situations, for example when it is difficult to predict the exact timing or carbohydrate content of a meal in advance, post-meal dosing of insulin may offer increased flexibility compared with mealtime dosing [Citation24,Citation25]. Interestingly, around half of physicians agreed that controlling PPG at every meal was important. The fact that this number was not higher may reflect a lack of awareness of the importance of PPG for overall glycemic control.

The most cited reasons for not prescribing faster aspart were good patient response to current treatment, patient reluctance to switch, or perceived non-reimbursement/funding issues. Despite evidence from randomized clinical trials demonstrating its benefits compared with insulin aspart [Citation19–Citation22], there is still a lack of clinical experience with faster aspart, which could have contributed to a reluctance to switch. In addition, therapeutic inertia is a recognized problem in patients with diabetes. It is known that, despite having poor glycemic control, many patients experience a delay before their treatment is intensified [Citation26,Citation27]. Studies have reported delays in intensification from one to two OADs despite patients having a HbA1c level >7.0% (>53 mmol/mol) [Citation26], and significant delays in initiation of insulin treatment despite poor glycemic control with OADs [Citation28–Citation30].

Some country-specific differences were seen, likely reflective of the prescribing history of faster aspart and local healthcare systems. Compared with the overall study population, Denmark and Switzerland had a greater proportion of specialist participants, and Canada had a greater proportion of GPs. This difference could be reflective of diabetes management pathways at a local level, with GPs in Canada being more likely to manage diabetes patients than specialists, and specialists being more responsible for diabetes care than GPs in Denmark and Switzerland. Physicians had been prescribing faster aspart for a longer period of time in the UK and for a shorter time in Switzerland, Denmark, and Finland. It is worth considering whether prescribing faster aspart for only 5–6 months (in Switzerland, Denmark, and Finland) is a long enough time for physicians to make truly informed claims about faster aspart, and whether they can be confident about the level of HbA1c control after this short time period. According to the survey, insulin-naïve patients starting insulin therapy have good access to an on-site diabetes nurse or educator in the UK, Denmark, and Finland, whereas access to this support appears to be more limited in Canada. Having an appropriate level of support and monitoring when switching to an ultra-fast-acting insulin, such as faster aspart, may indeed be critical to the success of the therapy. Reimbursement/funding was cited as a reason for not switching to faster aspart by a quarter of physicians in the UK and half of the physicians questioned in Canada, but it was not felt to be a reason for not prescribing faster aspart in Switzerland or Finland. These differences could be reflective of the reimbursement systems in these countries.

Compared with participating GPs, participating specialists had treated more patients with T1D with faster aspart, and managed a greater number of patients switching to faster aspart from another mealtime insulin. Furthermore, specialists were quicker or more able to prescribe faster aspart compared with GPs, perhaps reflecting differences in experience and/or availability of healthcare resources. Accordingly, more GPs considered reimbursement to be a reason for not prescribing faster aspart than did specialists. Access to an on-site diabetes nurse or educator was reportedly more common for specialists than GPs. This may have contributed to the increased confidence of specialists vs GPs in their patients’ ability to self-titrate faster aspart. Interestingly, access to this support varied between countries, ranging from 67% in Canada to 98% in the UK. However, this may have been a reflection of a greater number of GPs reporting in Canada versus specialists in the UK.

Most physicians in this survey expressed equal satisfaction with faster aspart and other mealtime insulins with regard to cost-effectiveness. However, studies have shown increased PPG levels to be associated with increased healthcare resource utilization in adults with diabetes treated with basal–bolus insulin in Italy, the UK, and the USA [Citation31]. Moreover, an analysis of faster aspart versus insulin aspart in patients with T1D in the UK enrolled in the onset 1 trial also showed that faster aspart was associated with not only improved clinical outcomes, but also cost savings in this setting [Citation23]. Therefore, treating postprandial hyperglycemia with faster formulations of mealtime insulin, such as faster aspart, may prove cost-effective while providing a clinical benefit to patients.

The findings of this survey are based heavily on physicians’ experiences, and could therefore be subject to recall bias.

Conclusions

Our real-world data on prescribers’ clinical experiences with faster aspart add to, and complement, the current body of evidence for its use in the management of diabetes. Physician and patient experiences were positive and, in keeping with the pharmacological attributes of faster aspart and phase 3 clinical data vs insulin aspart, the main prescription drivers were faster onset of action, improved PPG control, and dosing flexibility. These attributes of faster aspart are expected to be beneficial in glycemic management around meals. With adequate support and monitoring, results support switching of patients from a variety of other mealtime insulins to faster aspart.

Author’s contribution

AB was involved in study conception and design, co-formulation of the research questionnaire, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approval of the final version to be published; SA was involved in co-formulation of the research questionnaire, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approval of the final version to be published; ME was involved in study conception and design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approval of the final version to be published, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of this work; RM was involved in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approval of the final version to be published; JDDRF was involved in study conception and design, interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approval of the final version to be published, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of this work.

Declaration of interest

AB and SA are employees of IQVIA, which supported Novo Nordisk in this research. ME is an employee of Novo Nordisk and a minor stockholder in NN. RM was an employee of Novo Nordisk at the time this manuscript was prepared. JDDRF is an employee and shareholder of Novo Nordisk.

Reviewers disclosure

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they are a speaker for Novo Nordisk. The other Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (45.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the people who participated in this study, to Monika Russel-Szymczyk and Lise Højbjerre, Novo Nordisk, for review of and input to the manuscript, and to Jane Blackburn and Catherine Jones of Watermeadow Medical, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc (funded by Novo Nordisk A/S), for medical writing and editing assistance.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, JDDRF, upon reasonable request.

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Diabetes Association. 6 glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S55–s64. Epub 2017/12/10.

- Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT, Grunberger G, et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists and American college of endocrinology - clinical practice guidelines for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan - 2015. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(Suppl 1):1–87. Epub 2015/04/15.

- International Diabetes Federation Guideline Development Group. Guideline for management of postmeal glucose in diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:256–268. Epub 2013/03/14.

- Ryden L, Grant PJ, Anker SD, et al. ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: the task force on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and developed in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3035–3087. Epub 2013/09/03.

- DiMarchi RD, Chance RE, Long HB, et al. Preparation of an insulin with improved pharmacokinetics relative to human insulin through consideration of structural homology with insulin-like growth factor I. Horm Res. 1994;41(Suppl 2):93–96. Epub 1994/01/01.

- Howey DC, Bowsher RR, Brunelle RL, et al. [Lys(B28), Pro(B29)]-human insulin. A rapidly absorbed analogue of human insulin. Diabetes. 1994;43:396–402. Epub 1994/03/01.

- Heinemann L, Heise T, Jorgensen LN, et al. Action profile of the rapid acting insulin analogue: human insulin B28Asp. Diabet Med. 1993;10:535–539. Epub 1993/07/01.

- Owens D, Vora J. Insulin aspart: a review. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2006;2:793–804. Epub 2006/10/04.

- Barlocco D. Insulin glulisine. Aventis Pharma. Curr Opin Invest Drugs. 2003;4:1240–1244. Epub 2003/12/03.

- Helms KL, Kelley KW. Insulin glulisine: an evaluation of its pharmacodynamic properties and clinical application. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:658–668. Epub 2009/04/02.

- Basu A, Pieber TR, Hansen AK, et al. Greater early postprandial suppression of endogenous glucose production and higher initial glucose disappearance is achieved with fast-acting insulin aspart compared with insulin aspart. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:1615–1622. Epub 2018/03/02.

- Bruttomesso D, Pianta A, Mari A, et al. Restoration of early rise in plasma insulin levels improves the glucose tolerance of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 1999;48:99–105. Epub 1999/01/19.

- Pandyarajan V, Weiss MA. Design of non-standard insulin analogs for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12:697–704. Epub 2012/9/18.

- Kang S, Creagh FM, Peters JR, et al. Comparison of subcutaneous soluble human insulin and insulin analogues (AspB9, GluB27; AspB10; AspB28) on meal-related plasma glucose excursions in type I diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:571–577. Epub 1991/07/01.

- Home PD. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rapid-acting insulin analogues and their clinical consequences. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14:780–788. Epub 2012/2/11.

- Heise T, Hovelmann U, Brondsted L, et al. Faster-acting insulin aspart: earlier onset of appearance and greater early pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects than insulin aspart. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:682–688. Epub 2015/04/08.

- Home PD. Plasma insulin profiles after subcutaneous injection: how close can we get to physiology in people with diabetes? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:1011–1020. Epub 2015/06/05.

- Heise T, Pieber TR, Danne T, et al. A pooled analysis of clinical pharmacology trials investigating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of fast-acting insulin aspart in adults with type 1 diabetes. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56:551–559. Epub 2017/2/17.

- Buse JB, Carlson AL, Komatsu M, et al. Fast-acting insulin aspart versus insulin aspart in the setting of insulin degludec-treated type 1 diabetes: efficacy and safety from a randomized double-blind trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:2885–2893. Epub 2018/9/28.

- Russell-Jones D, Bode BW, De Block C, et al. Fast-acting insulin aspart improves glycemic control in basal-bolus treatment for type 1 diabetes: results of a 26-week multicenter, active-controlled, treat-to-target, randomized, parallel-group trial (Onset 1). Diabetes Care. 2017;40:943–950. Epub 2017/3/31.

- Bowering K, Case C, Harvey J, et al. Faster aspart versus insulin aspart as part of a basal-bolus regimen in inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes: the onset 2 trial. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:951–957. Epub 2017/5/10.

- Rodbard HW, Tripathy D, Vidrio Velazquez M, et al. Adding fast-acting insulin aspart to basal insulin significantly improved glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, 18-week, open-label, phase 3 trial (Onset 3). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:1389–1396. Epub 2017/3/28.

- Russell-Jones D, Heller SR, Buchs S, et al. Projected long-term outcomes in patients with type 1 diabetes treated with fast-acting insulin aspart vs conventional insulin aspart in the UK setting. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:1773–1780. Epub 2017/6/03.

- Cengiz E. Undeniable need for ultrafast-acting insulin: the pediatric perspective. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6:797–801. Epub 2012/8/28.

- Ligthelm RJ, Kaiser M, Vora J, et al. Insulin use in elderly adults: risk of hypoglycemia and strategies for care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1564–1570. Epub 2012/8/14.

- Khunti K, Wolden ML, Thorsted BL, et al. Clinical inertia in people with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study of more than 80,000 people. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3411–3417. Epub 2013/7/24.

- Brown JB, Nichols GA, Perry A. The burden of treatment failure in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1535–1540. Epub 2004/6/29.

- Rubino A, McQuay LJ, Gough SC, et al. Delayed initiation of subcutaneous insulin therapy after failure of oral glucose-lowering agents in patients with type 2 diabetes: a population-based analysis in the UK. Diabet Med. 2007;24:1412–1418. Epub 2007/11/29.

- Vaag A, Lund SS. Insulin initiation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: treatment guidelines, clinical evidence and patterns of use of basal vs premixed insulin analogues. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166:159–170. Epub 2011/9/21.

- Mosenzon O, Raz I. Intensification of insulin therapy for type 2 diabetic patients in primary care: basal-bolus regimen versus premix insulin analogs: when and for whom? Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 2):S212–8. Epub 2013/8/02.

- Pfeiffer KM, Sandberg A, Nikolajsen A, et al. Postprandial glucose and healthcare resource use: a cross-sectional survey of adults with diabetes treated with basal-bolus insulin. J Med Econ. 2018;21:66–73. Epub 2017/9/07.