ABSTRACT

Oral semaglutide is the first US Food and Drug Administration-approved oral glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA) for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D). Prior articles within this supplement reviewed the PIONEER trial program, which demonstrated that oral semaglutide reduced glycated hemoglobin and body weight when given to patients with uncontrolled T2D on various background therapies, and had a safety profile consistent with subcutaneous GLP-1RAs. This article provides guidance on integrating oral semaglutide into clinical practice in primary care. Patient populations with T2D who may gain benefit from oral semaglutide include those with inadequate glycemic control taking one or more oral glucose-lowering medication (e.g. after metformin), patients for whom weight loss would be beneficial, patients at risk of hypoglycemia, those who would historically have been considered for treatment with a subcutaneous GLP-1RA, and those receiving basal insulin who require treatment intensification. Like other GLP-1RAs, oral semaglutide is contraindicated in those with personal/family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma, and in those with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2, as noted in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Oral semaglutide has not been studied in those with a history of pancreatitis, is not recommended in patients with suspected/confirmed pancreatitis, and is not indicated in type 1 diabetes. When initiating oral semaglutide, gradual dose escalation is recommended to minimize the risk of gastrointestinal adverse events. As food and excess liquid reduce oral semaglutide absorption, patients should swallow the tablet with up to 4 fl oz/120 mL of water on an empty stomach upon waking, and should wait at least 30 minutes before eating, drinking, or taking other oral medications. Those managing patients should be aware of the potential impact of these dosing conditions on concomitant medications. When counseling patients, it is important to discuss these administration instructions, realistic therapeutic expectations, and strategies for mitigation of gastrointestinal events. Oral semaglutide provides a new option for add-on to initial T2D therapy (or later in the treatment paradigm), with the potential to enable more patients to benefit from the improvements in glycemic control, reductions in body weight, and low risk of hypoglycemia afforded by GLP-1RAs.

Article overview and relevance to your clinical practice

This supplement has explored the clinical profile of oral semaglutide, focusing on the results from the PIONEER program of clinical trials.

Drawing on these results, this article aims to provide guidance on integrating oral semaglutide into clinical practice in primary care.

In particular, the article focuses on answering several key questions that practitioners may face, including:

which patient populations is oral semaglutide most appropriate/suitable for and in what settings is oral semaglutide not recommended?

when can treatment with oral semaglutide be considered?

how should oral semaglutide be initiated?

what are the key topics for consideration when counseling patients?

In addressing these questions, we discuss illustrative patient cases and provide graphical summaries of the key considerations.

1. Introduction

As outlined in the previous articles in this supplement, the PIONEER program has established that oral semaglutide reduces glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and body weight when given to patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes (T2D) on diet and exercise alone, or who are receiving one or two oral antihyperglycemic agents, or receiving insulin with or without metformin () [Citation1–7]. Overall, the safety profile of oral semaglutide appears to be consistent with that reported for subcutaneous glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), with transient, mild-to-moderate gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events (AEs) being the most commonly reported. Drawing on the clinical profile of oral semaglutide from the PIONEER clinical trial program, this article aims to provide guidance on integrating oral semaglutide into clinical practice in the primary care setting.

Table 1. Summary of PIONEER 1–8 study design and clinical efficacy results

2. Which patients are appropriate for/most suited to oral semaglutide?

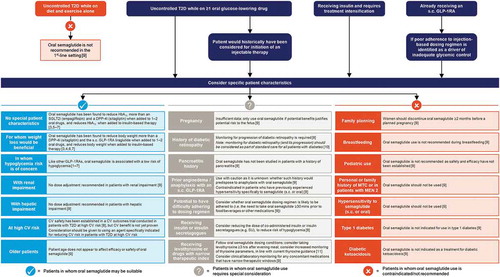

First approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2019, oral semaglutide is now available in the USA and several other countries for improving glycemic control in adults with T2D [Citation9,Citation12]. Potential scenarios in which oral semaglutide could be considered are summarized in and described in detail in this section. This discussion focuses on the suitability of oral semaglutide for various patient populations based on the clinical profile of the drug, as established in the PIONEER clinical trial program. However, in the reality of clinical practice, practitioners will also need to factor in nonclinical considerations when selecting a therapeutic agent – medication cost, insurance coverage, and local healthcare system guidelines may constrain the options available.

Figure 1. Key considerations for the use of oral semaglutide across a spectrum of clinical scenarios in type 2 diabetes

2.1. As monotherapy in patients with inadequate glycemic control on diet and exercise

Like most other GLP-1RAs [Citation13–18], oral semaglutide is indicated in the US “as an adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus” [Citation9]. The PIONEER 1 study demonstrated a beneficial effect of oral semaglutide as add-on to diet and exercise in terms of HbA1c and body weight reductions compared with placebo [Citation1]. While metformin monotherapy is the initial pharmacotherapy typically recommended for most patients [Citation19,Citation20], some clinical practice guidelines suggest that GLP-1RAs may be considered as treatment options in the first-line setting for select patients, such as those with cardiovascular disease (CVD) [Citation19,Citation21]. However, it should be noted that trials demonstrating cardiovascular (CV) benefits with some GLP-1RAs have been conducted in populations in which up to 98% of patients were already receiving one or more glucose-lowering medications [Citation22–26], and as such provide little evidence in the first-line setting.

The prescribing information notes that oral semaglutide is not recommended as first-line therapy [Citation9], which is consistent with the recommendations in the prescribing information for the injectable GLP-1RA, exenatide extended-release [Citation13].

2.2. Patients taking one or more oral antihyperglycemic agent (including metformin) with inadequate glycemic control

When patients fail to achieve glycemic control while on metformin with or without other oral antihyperglycemic agents, current treatment guidelines recommend considering a variety of options including GLP-1RAs, sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, sulfonylureas, and thiazolidinediones [Citation19,Citation20]. Practitioners wishing for more background on the profiles of these therapies should consult the latest Standards of Medical Care from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) or recommendations from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and American College of Endocrinology (ACE), which provide summarized overviews of the different classes [Citation19,Citation20].

Several trials within the PIONEER program have investigated the use of oral semaglutide as add-on to one or more oral antihyperglycemic agents in patients with inadequate glycemic control, as reviewed in detail in articles 2 and 3 of this supplement [Citation27,Citation28]. In summary, these studies demonstrated:

superior HbA1c lowering after 26 weeks with oral semaglutide compared with the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in patients uncontrolled on metformin (PIONEER 2) [Citation5];

superior HbA1c lowering after 26 weeks with oral semaglutide compared with the DPP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin in patients uncontrolled on metformin with or without a sulfonylurea (PIONEER 3) [Citation6];

similar (noninferior) HbA1c lowering with oral semaglutide compared with the subcutaneous GLP-1RA liraglutide after 26 weeks in patients uncontrolled on metformin with or without an SGLT2 inhibitor, with statistically significant HbA1c reductions by 1 year (PIONEER 4) [Citation4].

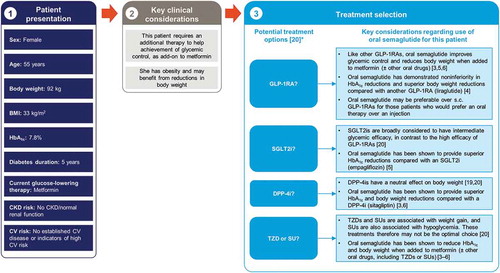

Oral semaglutide would therefore seem an appropriate agent to consider alongside these established treatment options when selecting a therapy for the second-line setting, after failure of metformin, as illustrated in the case study shown in . The choice of specific second-line agent should be guided by the principles of patient-centered care [Citation20]. This takes into consideration patient characteristics such as presence of comorbidities (e.g. CVD, chronic kidney disease [CKD], or heart failure), hypoglycemia risk, body weight, ability to tolerate AEs, and preferences on administration route and frequency (injection versus oral; daily versus weekly). We discuss each of these characteristics in the context of oral semaglutide in the following sections of this article.

Figure 2. The rationale for oral semaglutide early in the type 2 diabetes disease course, in a patient with inadequate glycemic control on metformin: an illustrative case study

2.3. Patients for whom weight loss would be beneficial

Almost 90% of patients with T2D are overweight or living with obesity [Citation29]. There are two key considerations regarding body weight that influence the choice of T2D medication: i) the need to minimize weight gain; ii) the potential benefit of inducing weight loss [Citation19,Citation20,Citation30]. Both GLP-1RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors are associated with weight loss and are recommended by the ADA for patients who need to minimize weight gain or who would benefit from weight loss [Citation20]. In contrast, DPP-4 inhibitors have a neutral effect, while thiazolidinediones, sulfonylureas, and insulin can induce weight gain [Citation20]. The results of studies exploring the use of oral semaglutide as add-on to metformin with or without additional oral antihyperglycemic agents are largely consistent with this class-specific hierarchy:

oral semaglutide was shown to provide body weight reductions at least as great as those with the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in PIONEER 2 after 26 weeks, with significantly greater reductions seen after 52 weeks (for the trial product estimand, but not the treatment policy estimand – see Panel 1) [Citation5];

oral semaglutide provided superior body weight reductions to the DPP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin after 26 weeks, and helped significantly more patients achieve body weight reductions of at least 5%, in PIONEER 3 [Citation6];

after 26 weeks in PIONEER 4, superior reductions in body weight were reported and a significantly greater proportion of patients achieved body-weight loss of at least 5% for oral semaglutide compared with the subcutaneous GLP-1RA liraglutide [Citation4], highlighting the fact that individual GLP-1RAs have different clinical profiles.

Within both PIONEER 2 and 4, body weight reductions with oral semaglutide 14 mg appeared to continue to accrue until ~38 weeks and plateau thereafter [Citation4,Citation5], although the results of PIONEER 3 suggest that reductions may continue to accrue for up to ~52 weeks [Citation6]. Plateauing of weight loss and maintenance thereafter is characteristic of GLP-1RAs, and an expected effect given their primary mechanism of weight loss is believed to be through reducing energy intake [Citation32].

Panel 1. Estimand use in the PIONEER trial program

The ability of oral semaglutide to induce weight loss from baseline reported across the PIONEER program suggests that it would be reasonable to consider use of this novel therapy in patients who would benefit from weight loss. It should be noted that while they have been shown to reduce body weight, neither oral semaglutide nor the injectable GLP-1RAs approved for T2D are specifically indicated for weight loss [Citation30], with the exception of liraglutide at a recommended dose of 3.0 mg once daily [Citation33] (exceeding the maximum 1.8 mg once-daily dose recommended for the version of liraglutide approved in T2D [Citation14]). The ADA guidelines for T2D recommend considering the use of FDA-approved weight-loss medications (of which there are few) in patients with T2D who have a body mass index of 27 kg/m2 or higher, with appropriate balancing of the benefit:risk profile with long-term use of these drugs [Citation30].

2.4. Patients in whom hypoglycemia risk is of particular concern

Hypoglycemia risk is one of the key considerations when selecting pharmacological therapy for patients with T2D [Citation20]. There is a need to avoid both mild-to-moderate episodes of hypoglycemia and their associated impact on patient quality of life, as well as more severe episodes that carry the risk of further patient morbidity, including hospitalization, CV events, and also death [Citation34,Citation35]. Older patients, those with cognitive dysfunction, those who have renal impairment, and those with longer duration of diabetes are at particular risk of experiencing severe hypoglycemia, as reviewed in detail elsewhere [Citation35,Citation36]. Several classes of antihyperglycemic agents are considered to have a neutral effect on the risk of hypoglycemia, including DPP-4 inhibitors, metformin, GLP-1RAs, SGLT2 inhibitors, and thiazolidinediones, whereas sulfonylureas and insulin are associated with increased risk [Citation19].

Like the subcutaneous formulations of GLP-1RAs, addition of oral semaglutide to the treatment regimen has typically been shown to be associated with a low risk of hypoglycemia, with a low incidence of severe or blood glucose-confirmed symptomatic episodes reported across the PIONEER studies, similar to that reported for empagliflozin, sitagliptin, and liraglutide [Citation1–6,Citation8]. However, it is important to understand that the risk of hypoglycemia is influenced by the background therapy the patient is receiving. In the PIONEER program, instances of severe or blood glucose-confirmed symptomatic hypoglycemia were most commonly reported among patients who were also receiving a background sulfonylurea or insulin [Citation3,Citation6,Citation7,Citation9].

Patients who have CKD are at increased risk of hypoglycemia [Citation37]. In patients with T2D and moderate renal impairment (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2), incidence of blood glucose-confirmed symptomatic hypoglycemia was low with oral semaglutide, and no patients experienced severe hypoglycemia, despite background therapy including sulfonylureas in 40% of patients and basal insulin in 35% of patients [Citation2]. Similarly, in a small pharmacokinetic study that enrolled patients with or without T2D who had mild, moderate or severe renal impairment, or end-stage renal disease (ESRD), blood glucose-confirmed symptomatic hypoglycemia was rare and no patients experienced severe hypoglycemia [Citation38].

2.5. Patients for whom initiation of an injectable GLP-1RA would otherwise have been considered

Oral semaglutide offers broadly similar benefits to injectable GLP-1RAs in terms of reductions in HbA1c and body weight, with low risk of hypoglycemia, and is therefore a new option for patients who would traditionally have been prescribed a subcutaneous GLP-1RA. In this context, oral semaglutide presents a potential advantage for those patients who would prefer oral medications over injectable therapy [Citation39]. As clinical inertia is often seen when patients require intensification to injectables [Citation40], the oral formulation may help ameliorate some of the resistance to use reported for subcutaneous GLP-1RAs [Citation39] and improve adherence to therapy [Citation41]. Nevertheless, the potential benefits of some injectable GLP-1RAs, in terms of frequency of administration, convenience, and ease of administration, should not be discounted when selecting the most appropriate therapy for the individual patient, taking into consideration factors such as the patient’s lifestyle, existing treatment regimen, and preference (see article 1 for a more in-depth review of the GLP-1RA class) [Citation20].

2.6. Patients receiving insulin who require treatment intensification

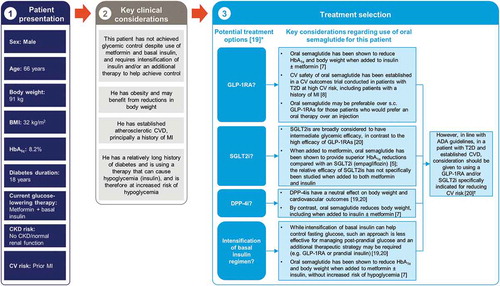

For patients who are already receiving basal insulin, addition of a subcutaneous GLP-1RA is proposed as an alternative to intensifying the insulin regimen, offering the potential for improvement in glycemic control, reduction in body weight, and lower risk of hypoglycemia [Citation20]. Similar effects were seen in the PIONEER 8 study, with add-on of oral semaglutide to insulin, including basal, basal-bolus, and premix regimens (41.9%, 38.9%, and 17.6% of patients at screening, respectively), with or without metformin [Citation7]. In this trial, oral semaglutide as add-on to insulin with or without metformin also enabled a reduction from baseline in the mean daily insulin dosage after a year of treatment [Citation7]. Addition of oral semaglutide may therefore be a new option for those not achieving glycemic control with insulin. An illustrative case study exploring the rationale for oral semaglutide in this setting is shown in .

Figure 3. The rationale for oral semaglutide at a later stage in the type 2 diabetes disease course, in a patient with inadequate glycemic control on insulin and metformin and with prior cardiovascular disease: an illustrative case study

2.7. Patients already receiving an injectable GLP-1RA who may benefit from a switch to an oral formulation

As discussed in detail in the first article in this supplement [Citation42], subcutaneous GLP-1RAs are currently associated with adherence/persistence rates that indicate room for improvement [Citation43–45]. While there is likely a myriad of factors contributing to these rates, in part they are likely to relate to patient and health-care provider concerns regarding injections, including perceived pain, inconvenience, and administration challenges [Citation46–49].

In those patients currently receiving a subcutaneous GLP-1RA who are not reaching their glycemic targets, an appropriate strategy may be to first explore with the patient whether they are experiencing challenges adhering to the recommended dosing regimen, and if so, consider whether switching to a tablet formulation (i.e. oral semaglutide) would be likely to enhance compliance. However, given the relatively recent availability of oral semaglutide, there are currently no data showing whether oral semaglutide enhances adherence compared with subcutaneous GLP-1RAs.

Oral semaglutide appears to have a safety and tolerability profile that is comparable to subcutaneous GLP-1RAs [Citation4,Citation50]. Consequently, while switching from a subcutaneous GLP-1RA to oral semaglutide may afford benefits in terms of improved adherence for some patients, it would not be expected to improve tolerability for those who have previously experienced AEs with GLP-1RAs.

2.8. Patients with renal impairment

Dose adjustment is required for many glucose-lowering agents in patients with renal impairment [Citation19,Citation20]. For the subcutaneous GLP-1RAs, dose adjustment is not required in mild or mild-to-moderate renal impairment (eGFR 45–89 mL/min/1.73 m2), while recommendations for those with moderately severe (eGFR 30–44 mL/min/1.73 m2) or severe renal impairment (eGFR 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2) and ESRD (eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2) vary between individual agents [Citation13–18]. For oral semaglutide, renal impairment (including ESRD) has no clinically relevant impact on the pharmacokinetics of semaglutide, and no dose adjustments are recommended [Citation9,Citation38]. In patients with moderate renal impairment (eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2), oral semaglutide was found to reduce HbA1c and body weight, with a renal safety profile similar to that previously reported for other GLP-1RAs (PIONEER 5) [Citation2]. As noted in the prescribing information, if patients with renal impairment report severe adverse GI reactions while taking oral semaglutide, monitoring of renal function is recommended during dose initiation or escalation [Citation9].

2.9. Patients with hepatic impairment

Dose adjustment is not required for oral semaglutide in patients with hepatic impairment, as hepatic impairment does not appear to impact the exposure of semaglutide; however, this recommendation is based on the limited data currently available [Citation9,Citation54].

2.10. Patients with established CVD or at high CV risk

For patients with established atherosclerotic CVD or indicators of high risk, the ADA and AACE/ACE recommend use of GLP-1RAs or SGLT2 inhibitors that have proven CVD benefit [Citation19,Citation20]. ADA recommendations define ‘proven’ as being specifically indicated for reducing CVD events [Citation20], which for GLP-1RAs currently applies to dulaglutide, liraglutide, and subcutaneous semaglutide. These three agents are FDA-approved for the reduction of major adverse CV events in patients with T2D and established CVD (all three agents) or multiple CV risk factors (dulaglutide only) [Citation14,Citation17,Citation18]. In those with or at high risk of heart failure (particularly with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction [<45%]), SGLT2 inhibitors are preferred, with GLP-1RAs recommended if SGLT2 inhibitors are contraindicated/not tolerated or if eGFR is less than adequate [Citation20]. For patients with or at high risk of atherosclerotic CVD, CKD, or heart failure, the choice of treatment should be considered independent of baseline or target HbA1c [Citation19,Citation20].

The CV safety of oral semaglutide has been studied in patients at high CV risk as part of the PIONEER 6 study [Citation8] (see article 4 [Citation55] for a more in-depth review of this study). The study established the noninferiority of oral semaglutide to placebo in terms of the incidence of major adverse CV events in this population [Citation8]. Whether oral semaglutide has a positive effect on CV risk will be determined by the ongoing SOUL trial (see article 4 for further information [Citation55]) [Citation56]. An illustrative case study exploring the treatment options for a patient with CV risk factors is shown in .

2.11. Older patients

As described earlier in this supplement (see article 4 [Citation55]), patient age does not appear to affect the efficacy or safety of oral semaglutide [Citation9,Citation57], and consequently, no adjustments are recommended when using oral semaglutide in older patients in general. While there is no reported evidence, the prescribing information for oral semaglutide does, however, note that greater sensitivity of some older patients to the effects of the drug cannot be ruled out [Citation9]. In line with treatment guidelines, glycemic targets in older patients should therefore be individualized to take into account the patient’s health status and individual treatment response, and over-treatment should be avoided through strategies such as using the lowest effective dose required to maintain glycemic control [Citation58].

2.12. Patient populations in whom oral semaglutide use is not recommended or requires special consideration

Oral semaglutide use is either not recommended or requires special consideration in women who are pregnant, planning a family, or breastfeeding, in pediatric patients, and in those who have previously experienced hypersensitivity to semaglutide (oral or subcutaneous formulations) or angioedema/anaphylaxis with an injectable GLP-1RA, as described in [Citation9]. In addition, like most GLP-1RAs, oral semaglutide should not be used in patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) or in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 (MEN 2) [Citation9] – see Panel 2 herein, article 1 of this supplement [Citation42], and the prescribing information [Citation9] for further information on this topic. It should also be noted that oral semaglutide is not indicated for patients with type 1 diabetes or for the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis, nor has it been studied in those with a history of pancreatitis [Citation9]. The prescribing information notes that upper GI disease (including chronic gastritis and/or gastroesophageal reflux disease) does not affect the pharmacokinetics of oral semaglutide [Citation9]; however, consistent with recommendations for other GLP-1RAs [Citation13,Citation15,Citation16,Citation18,Citation47,Citation59], the authors would not recommend oral semaglutide for patients with gastroparesis.

Panel 2. Exploring the risks of thyroid C-cell tumors with GLP-1RAs

3. When can treatment with oral semaglutide be considered?

Early achievement of glycemic control has many potential benefits for patients with T2D [Citation40]. Of note, there is increasing evidence supporting the theory that poor glycemic control in the early years after diagnosis increases the risk of complications in later life [Citation67,Citation68]. These results suggest a need to avoid clinical inertia and ensure glycemic control is achieved rapidly after diagnosis [Citation69]. Several analyses of data from the PIONEER studies provide insights into the effects of oral semaglutide when used relatively soon after diagnosis, or later in the disease course, as summarized below.

An exploratory analysis investigated the efficacy of oral semaglutide based on diabetes duration, including data from PIONEER 1–5, 7, and 8 [Citation70]. Across the studies, reductions in HbA1c with oral semaglutide were found to be consistent regardless of whether patients had diabetes durations of <5, 5–<10, or ≥10 years [Citation70]. In addition, the odds of achieving HbA1c <7.0% were consistently greater with oral semaglutide 7 and 14 mg versus the comparators in each study, irrespective of diabetes duration [Citation70]. A further exploratory analysis using the same dataset assessed the efficacy of oral semaglutide in subgroups with baseline HbA1c ≤8.0%, >8.0–≤9.0%, or >9.0% [Citation71]. This analysis indicated that oral semaglutide 7 and 14 mg reduced HbA1c to a greater extent than the comparators in each study across all the baseline HbA1c subgroups, with the greatest reductions seen in the subgroups with higher baseline HbA1c [Citation71].

The proportion of patients requiring rescue medication (for persistent/unacceptable hyperglycemia) during treatment with oral semaglutide was lower than with placebo in all of the PIONEER trials that had a placebo arm, including PIONEER 1 (in T2D uncontrolled on diet/exercise alone) and PIONEER 4 (in T2D uncontrolled with metformin with or without an SGLT2 inhibitor) [Citation1,Citation4]. This finding suggests a potential benefit of early initiation of oral semaglutide in terms of reducing the need for rescue medication for hyperglycemia.

Overall, these results indicate that oral semaglutide has the potential to help patients achieve glycemic control, whether it is used earlier or later in the disease course ( and ).

4. How should oral semaglutide be initiated and what are the key communication points for counseling patients?

Key considerations when initiating oral semaglutide are described in detail below, and in Panel 3 and , and include:

Figure 4. Key communication points for counseling patients suitable for initiation of oral semaglutide [Citation9,Citation59,Citation76]

![Figure 4. Key communication points for counseling patients suitable for initiation of oral semaglutide [Citation9,Citation59,Citation76]](/cms/asset/153d9529-2c6d-44ce-9cd2-631eca415e39/ipgm_a_1798162_f0004_c.jpg)

the need for gradual dose-escalation;

how and when the tablets are taken (particularly in relation to other medications);

adjustment of background insulin/insulin secretagogue doses;

potential side effects and how to mitigate them;

managing patients’ therapeutic expectations.

Panel 3. An illustrative clinical discussion exploring administration recommendations for oral semaglutide

4.1. Recommended doses and the rationale for dose escalation

Oral semaglutide is recommended to be initiated at 3 mg once daily for 30 days, followed by an increase to 7 mg once daily, and after a further 30 days to increase to 14 mg once daily if additional glycemic control is required [Citation9]. This gradual dose-escalation approach is designed to help minimize the risk of GI AEs [Citation1,Citation50]. It is important to understand (and counsel patients accordingly) that the initial 3 mg dose is intended for treatment initiation in order to help mitigate GI AEs and may not be effective as a maintenance dose [Citation9], and as such, decisions based on treatment effectiveness should not be made until after escalation to the intended maintenance dose of 7 or 14 mg is reached and the drug has reached steady-state on this dose, which occurs after 4–5 weeks [Citation9].

4.2. How to take oral semaglutide and what to do if doses are missed

Exposure is limited when oral semaglutide is administered within 30 minutes of eating food [Citation72], or with excess water [Citation75]. To avoid decreasing the absorption of oral semaglutide and reducing its effectiveness, patients should therefore be instructed to take oral semaglutide in a fasting state and at least 30 minutes before the first food or beverage of the day, with up to 4 fl oz (120 mL) of water [Citation9]. Patients should also be advised that any other oral medications should be taken at least 30 minutes after oral semaglutide, and not at the same time [Citation9]. It is also important to highlight that the oral semaglutide tablet should be swallowed whole, and not split, crushed, or chewed [Citation9]. Patients should be advised that if they miss a dose, they should skip that dose for the day and take the next dose as scheduled the next day [Citation9].

4.3. Dose adjustment for patients taking insulin or insulin secretagogues

Consistent with many classes of antihyperglycemic therapy, concomitant administration of oral semaglutide with an insulin secretagogue (e.g. sulfonylureas) or insulin can increase the risk of hypoglycemia [Citation9,Citation19]. In line with recommendations for other classes of agents [Citation19], consideration should be given to reducing the dose of background insulin or insulin secretagogues (e.g. sulfonylureas) when initiating oral semaglutide, in order to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia [Citation9]. In PIONEER 8, a 20% reduction in total daily insulin dose was recommended for the first 8 weeks of concomitant treatment, with insulin dose adjustment recommended thereafter based on blood glucose and target HbA1c levels [Citation7]. In this study, addition of oral semaglutide to insulin treatment did not increase the risk of hypoglycemia compared with placebo [Citation7].

4.4. Considerations for patients taking other oral medications

As oral semaglutide delays gastric emptying, it may affect absorption of other oral medications [Citation11]. It is therefore important to ensure patients adhere to administration timing recommendations (i.e. taking oral semaglutide prior to other oral medications and waiting at least 30 minutes before taking any other oral medications) [Citation9]. Pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction studies suggest no clinically relevant interactions or need for dose adjustment for patients receiving commonly used medications including omeprazole, lisinopril, warfarin, digoxin, metformin, furosemide, rosuvastatin, or the combined oral contraceptive ethinylestradiol/levonorgestrel [Citation77–80].

When oral semaglutide is administered concomitantly with medications that have narrow therapeutic windows or that require clinical monitoring, increased clinical/laboratory monitoring should be considered [Citation9]. An example of such an agent is levothyroxine, which is used as a thyroid hormone replacement therapy and is recommended to be taken on an empty stomach before breakfast [Citation81]. When a single dose of levothyroxine 600 µg was co-administered with oral semaglutide at steady-state in a study in healthy volunteers, thyroxine exposure increased by 33%, potentially due to a delay in gastric emptying caused by oral semaglutide [Citation9,Citation73]. Patients taking concomitant levothyroxine should therefore be advised to comply with the dosing conditions for oral semaglutide [Citation9]. In line with current medical guidance, close monitoring of thyroxine parameters should be considered and patients could consider taking levothyroxine at least 3 hours after the last meal of the day instead of in the morning [Citation73,Citation74].

4.5. Approach to follow-up and monitoring

The ADA and AACE/ACE recommend the patient’s clinical status should be reassessed and treatment modified accordingly on a regular basis – the AACE/ACE suggest every 3 months, while the ADA propose every 3 to 6 months [Citation19,Citation20]. For oral semaglutide, specific monitoring recommendations include the need to monitor renal function if patients with renal impairment report serious GI AEs, observe patients for any signs/symptoms of pancreatitis (discontinue treatment if any occur), and consider increased clinical/laboratory monitoring of concomitant oral medications with a narrow therapeutic index [Citation9] (). The prescribing information also recommends monitoring for progression of diabetic retinopathy complications if oral semaglutide is used in those with a history of diabetic retinopathy [Citation9]. This should not represent a change to clinical practice, as monitoring for diabetic retinopathy (and its progression) is recommended as part of standard care for all patients with diabetes [Citation10].

4.6. Recommendations for managing transient GI adverse effects

GI AEs, typically of a transient and mild-to-moderate nature, are the most common type of AE seen with oral semaglutide (Panel 4), consistent with the wider GLP-1RA class. Across the PIONEER 1–8 trials, discontinuation of therapy due to GI AEs was reported in 2–12% of patients in oral semaglutide groups [Citation1–7,Citation8]. Beyond adherence to the recommended gradual dose-escalation regimen, potential approaches to minimizing/managing GI AEs with oral semaglutide are similar to those suggested for injectable GLP-1RAs [Citation59,Citation76]:

patient education about the anticipated transient nature of GI AEs;

recommending that patients avoid large, high-fat meals, and instead reduce meal sizes/eat smaller meals more frequently and stop eating when they feel full;

highlighting the importance of drinking fluids to reduce risk of dehydration if GI AEs are experienced [Citation9].

Consideration could also be given to short-term use of antiemetics, as has been suggested for subcutaneous GLP-1RAs [Citation76,Citation82,Citation83]; however, there is no direct evidence to date exploring the impact of antiemetics on incidence of GI AEs with oral semaglutide.

Panel 4. Key safety outcomes across the global PIONEER trial program [Citation1–7,Citation9]

4.7. Additional patient counseling

In addition to informing patients (and their caregivers) about the potential for GI AEs, it is important to advise the patient to read the patient information included with oral semaglutide, which provides information on topics such as pancreatitis, diabetic retinopathy complications, and pregnancy () [Citation9]. Taking the time to counsel patients on the anticipated effects of oral semaglutide (e.g. what glucose-lowering effects to expect and the importance of allowing time for HbA1c goals to be realized, setting realistic expectations for body weight reductions, etc.) may also help ensure patient motivation and adherence to treatment [Citation59,Citation76].

5. Conclusion

Oral semaglutide provides a new option for the management of T2D for use as add-on to initial treatment (or further along the therapeutic pathway), with a convenient administration route for patients who may prefer oral therapies over injections. By reducing the administrative burden on patients and practitioners, the availability of oral semaglutide may enable more patients to benefit from the improvements in glycemic control, reductions in body weight, and low risk of hypoglycemia afforded by GLP-1RAs, and shift the use of this modality to earlier in the treatment continuum.

Article highlights

Article overview and relevance to your clinical practice

This supplement has explored the clinical profile of oral semaglutide, focusing on the results from the PIONEER program of clinical trials.

Drawing on these results, this article aims to provide guidance on integrating oral semaglutide into clinical practice in primary care.

In particular, the article focuses on answering several key questions that practitioners may face, including:

– Which patient populations is oral semaglutide most appropriate/suitable for and in what settings is oral semaglutide not recommended?

– When can treatment with oral semaglutide be considered?

– How should oral semaglutide be initiated?

– What are the key topics for consideration when counseling patients?

In addressing these questions, we discuss illustrative patient cases and provide graphical summaries of the key considerations.

Declaration of interest

S.A.B. has received speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Janssen, and Novo Nordisk; consultant honoraria from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi US.

O.M. has served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, BOL Pharma, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; received a research grant paid to her institution from AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk; and has been a member of the speaker’s bureau for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

E.E.W. has received research support from Abbott; serves on advisory boards for Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Voluntis; and consults for Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Mannkind.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Under the direction of the authors, medical writing and editorial support were provided by Nicola Beadle of Axis, a division of Spirit Medical Communications Group Ltd. (funded by Novo Nordisk Inc.). The authors were involved with drafting the outline and critically editing all drafts during the development of the article, and all authors provided their final approval for submission.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aroda VR, Rosenstock J, Terauchi Y, et al. PIONEER 1: randomized clinical trial of the efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide monotherapy in comparison with placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(9):1724–1732.

- Mosenzon O, Blicher TM, Rosenlund S, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate renal impairment (PIONEER 5): a placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(7):515–527.

- Pieber TR, Bode B, Mertens A, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide with flexible dose adjustment versus sitagliptin in type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 7): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(7):528–539.

- Pratley R, Amod A, Hoff ST, et al. Oral semaglutide versus subcutaneous liraglutide and placebo in type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 4): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3a trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):39–50.

- Rodbard HW, Rosenstock J, Canani LH, et al. Oral semaglutide versus empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled on metformin: the PIONEER 2 trial. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(12):2272–2281.

- Rosenstock J, Allison D, Birkenfeld AL, et al. Effect of additional oral semaglutide vs sitagliptin on glycated hemoglobin in adults with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled with metformin alone or with sulfonylurea: the PIONEER 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(15):1466–1480.

- Zinman B, Aroda VR, Buse JB, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of oral semaglutide versus placebo added to insulin with or without metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: the PIONEER 8 trial. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(12):2262–2271.

- Husain M, Birkenfeld AL, Donsmark M, et al. Oral semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(9):841–851.

- Rybelsus® (semaglutide) prescribing information [updated Jan 2020; cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/213182s000,213051s001lbl.pdf

- American Diabetes Association. 11. Microvascular complications and foot care: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S135–S151.

- Dahl K, Blundell J, Gibbons C, et al. Oral semaglutide improves postprandial glucose and lipid metabolism and delays first-hour gastric emptying in subjects with type 2 diabetes (Abstract). Diabetologia. 2019;62(Suppl 1):50.

- Novo Nordisk. Rybelsus® (oral semaglutide) approved for the treatment of adults with type 2 diabetes in the EU. 2020 [cited 2020 May 25] Available from: https://www.novonordisk.com/media/news-details.2277630.html

- Bydureon® (exenatide extended-release) prescribing information [updated Feb 2020; cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/022200s030lbl.pdf

- Victoza® (liraglutide) prescribing information [updated Jun 2019; cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/022341s031lbl.pdf

- Adlyxin® (lixisenatide) prescribing information [updated Jan 2019; cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: http://products.sanofi.us/Adlyxin/Adlyxin.pdf

- Byetta® (exenatide) prescribing information [updated Feb 2020; cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/021773s043lbl.pdf

- Ozempic® (semaglutide) prescribing information [updated Jan 2020; cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/209637s003lbl.pdf

- Trulicity® (dulaglutide) prescribing information [updated Feb 2020; cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/125469s033lbl.pdf

- Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm – 2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107–139.

- American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S98–S110.

- Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(2):255–323.

- Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of participants in the Researching cardiovascular Events with a Weekly Incretin in Diabetes (REWIND) trial on the cardiovascular effects of dulaglutide. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(1):42–49.

- Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10193):121–130.

- Hernandez AF, Green JB, Janmohamed S, et al. Albiglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Harmony Outcomes): a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10157):1519–1529.

- Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311–322.

- Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1834–1844.

- Lavernia F, Blonde L. Clinical review of the efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with other oral antihyperglycemic agents and placebo. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(S2):15–25.

- Wright EE, Aroda VA. Clinical review of the efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes considered for injectable GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy or currently on insulin therapy. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(S2):26–36.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report 2020: estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. [cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf

- American Diabetes Association. 8. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S89–S97.

- Aroda VR, Saugstrup T, Buse JB, et al. Incorporating and interpreting regulatory guidance on estimands in diabetes clinical trials: the PIONEER 1 randomized clinical trial as an example. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(10):2203–2210.

- Nauck MA, Meier JJ. Are all GLP-1 agonists equal in the treatment of type 2 diabetes? Eur J Endocrinol. 2019;181:R211–R234.

- Saxenda® (liraglutide) prescribing information [updated Oct 2018; cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/206321s007lbl.pdf

- Lash RW, Lucas DO, Illes J. Preventing hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(4):1265–1268.

- Yun JS, Ko SH. Risk factors and adverse outcomes of severe hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J. 2016;40(6):423–432.

- Amiel SA, Dixon T, Mann R, et al. Hypoglycaemia in type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25(3):245–254.

- Moen MF, Zhan M, Hsu VD, et al. Frequency of hypoglycemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(6):1121–1127.

- Granhall C, Søndergaard FL, Thomsen M, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of oral semaglutide in subjects with renal impairment. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018;57(12):1571–1580.

- Bui V, Neumiller JJ. Oral semaglutide. Clin Diabetes. 2018;36(4):327–329.

- Santos Cavaiola T, Kiriakov Y, Reid T. Primary care management of patients with type 2 diabetes: overcoming inertia and advancing therapy with the use of injectables. Clin Ther. 2019;41(2):352–367.

- Miller E, Aguilar RB, Herman ME, et al. Type 2 diabetes: evolving concepts and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2019;86(7):494–504.

- Brunton SA, Wysham CH. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: role and clinical experience to date. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(S2):3–14.

- Buysman EK, Liu F, Hammer M, et al. Impact of medication adherence and persistence on clinical and economic outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with liraglutide: a retrospective cohort study. Adv Ther. 2015;32(4):341–355.

- Divino V, Boye KS, Lebrec J, et al. GLP-1 RA treatment and dosing patterns among type 2 diabetes patients in six countries: a retrospective analysis of pharmacy claims data. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10(3):1067–1088.

- Mody R, Grabner M, Yu M, et al. Real-world effectiveness, adherence and persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus initiating dulaglutide treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(6):995–1003.

- Kruger DF, LaRue S, Estepa P. Recognition of and steps to mitigate anxiety and fear of pain in injectable diabetes treatment. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2015;8:49–56.

- Lyseng-Williamson KA. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor analogues in type 2 diabetes: their use and differential features. Clin Drug Investig. 2019;39(8):805–819.

- Okemah J, Peng J, Quiñones M. Addressing clinical inertia in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1735–1745.

- Spain CV, Wright JJ, Hahn RM, et al. Self-reported barriers to adherence and persistence to treatment with injectable medications for type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther. 2016;38(7):1653–1664.

- Davies M, Pieber TR, Hartoft-Nielsen ML, et al. Effect of oral semaglutide compared with placebo and subcutaneous semaglutide on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(15):1460–1470.

- Farxiga® (dapagliflozin) prescribing information [updated Jan 2020; cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/202293s022lbl.pdf

- Jardiance® (empagliflozin) prescribing information [updated Jan 2020; cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/204629s023lbl.pdf

- Invokana® (canagliflozin) prescribing information [updated Jan 2020; cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/204042s036lbl.pdf

- Bækdal TA, Thomsen M, Kupčová V, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of oral semaglutide in subjects with hepatic impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;58(10):1314–1323.

- Mosenzon O, Miller EM, Warren ML. Oral semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, renal impairment, or other comorbidities, and in older patients. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(S2):37–47.

- Clinicaltrials.gov. A heart disease study of semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes (SOUL). Trial ID NCT03914326. [cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03914326

- Aroda VR, Bauer R, Herts CL, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide by baseline age in the PIONEER clinical trial program. Diabetes. 2020;69(Suppl 1):932-P.

- American Diabetes Association. 12. Older adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S152–S162.

- Reid TS. Practical use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist therapy in primary care. Clin Diabetes. 2013;31(4):148–157.

- Altekruse S, Das A, Cho H, et al. Do US thyroid cancer incidence rates increase with socioeconomic status among people with health insurance? An observational study using SEER population-based data. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009843.

- Cabanillas ME, McFadden DG, Durante C. Thyroid cancer. Lancet. 2016;388(10061):2783–2795.

- Olson E, Wintheiser G, Wolfe KM, et al. Epidemiology of thyroid cancer: a review of the National Cancer Database, 2000-2013. Cureus. 2019;11(2):e4127.

- Stamatakos M, Paraskeva P, Stefanaki C, et al. Medullary thyroid carcinoma: the third most common thyroid cancer reviewed. Oncol Lett. 2011;2(1):49–53.

- Cao C, Yang S, Zhou Z. GLP-1 receptor agonists and risk of cancer in type 2 diabetes: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endocrine. 2019;66(2):157–165.

- Guo X, Yang Q, Dong J, et al. Tumour risk with once-weekly glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a systematic review. Clin Drug Investig. 2016;36(6):433–441.

- Liu Y, Zhang X, Chai S, et al. Risk of malignant neoplasia with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Res. 2019;2019:1534365.

- Laiteerapong N, Ham SA, Gao Y, et al. The legacy effect in type 2 diabetes: impact of early glycemic control on future complications (the Diabetes & Aging Study). Diabetes Care. 2019;42(3):416–426.

- Takao T, Matsuyama Y, Suka M, et al. Analysis of the duration and extent of the legacy effect in patients with type 2 diabetes: a real-world longitudinal study. J Diabetes Complications. 2019;33(8):516–522.

- Khunti K, Seidu S. Therapeutic inertia and the legacy of dysglycemia on the microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(3):349–351.

- Haluzík M, Bauer R, Eriksson JW, et al. Efficacy of oral semaglutide according to diabetes duration: an exploratory subgroup analysis of the PIONEER trial programme (Abstract). Diabetologia. 2019;62(Suppl 1):49.

- Meier JJ, Bauer R, Blicher TM, et al. Efficacy of oral semaglutide according to baseline HbA1c: an exploratory subgroup analysis of the PIONEER trial programme (Abstract). Diabetologia. 2019;62(Suppl 1):51.

- Maarbjerg SJ, Borregaard J, Breitschaft A, et al. Evaluation of the effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of oral semaglutide. Presented at the American Diabetes Association, San Diego, California; 2017 Jun 9–13.

- Hauge C, Breitschaft A, Hartoft-Nielsen M-L, et al. A drug-drug interaction trial of oral semaglutide with levothyroxine and multiple coadministered tablets. J Endocr Soc. 2019;3(Suppl 1):SAT–140.

- Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the American Thyroid Association Task Force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid. 2014;24(12):1670–1751.

- Connor A, Donsmark M, Hartoft-Nielsen M-L, et al. A pharmacoscintigraphic study of the relationship between tablet erosion and pharmacokinetics of oral semaglutide. Diabetologia. 2017;60(Suppl 1):S361. Abstract 787.

- Milne N. How to use GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy safely and effectively. Diabetes Primary Care. 2019;21:45–46.

- Bækdal TA, Breitschaft A, Navarria A, et al. A randomized study investigating the effect of omeprazole on the pharmacokinetics of oral semaglutide. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2018;14:869–877.

- Bækdal TA, Albayaty M, Manigandan E, et al. A trial to investigate the effect of oral semaglutide on the pharmacokinetics of furosemide and rosuvastatin in healthy subjects (Abstract). Diabetologia. 2018;61(Suppl 1):714.

- Bækdal TA, Borregaard J, Hansen CW, et al. Effect of oral semaglutide on the pharmacokinetics of lisinopril, warfarin, digoxin, and metformin in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019;58(9):1193–1203.

- Jordy AB, Breitschaft A, Christiansen E, et al. Oral semaglutide does not affect the bioavailability of the combined oral contraceptive, ethinylestradiol/levonorgestrel (Abstract). Diabetologia. 2018;61(Suppl 1):713.

- Levoxyl® (levothyroxine sodium) prescribing information [updated Nov 2018; cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/021301s038lbl.pdf

- Ellero C, Han J, Bhavsar S, et al. Prophylactic use of anti-emetic medications reduced nausea and vomiting associated with exenatide treatment: a retrospective analysis of an open-label, parallel-group, single-dose study in healthy subjects. Diabet Med. 2010;27(10):1168–1173.

- Kalra S, Das AK, Sahay RK, et al. Consensus recommendations on GLP-1 RA use in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: South Asian task force. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10(5):1645–1717.