ABSTRACT

Pustular psoriasis refers to a heterogeneous group of chronic inflammatory skin disorders that are clinically, histologically, and genetically distinct from plaque psoriasis. Pustular psoriasis may present as a recurrent systemic illness (generalized pustular psoriasis [GPP]), or as localized disease affecting the palms and/or soles (palmoplantar pustulosis [PPP], also known as palmoplantar pustular psoriasis), or the digits/nail beds (acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau [ACH]). These conditions are rare, but their possible severity and consequences should not be underestimated. GPP, especially an acute episode (flare), may be a medical emergency, with potentially life-threatening complications. PPP and ACH are often debilitating conditions. PPP is associated with impaired health-related quality of life and psychiatric morbidity, while ACH threatens irreversible nail and/or bone damage. These conditions can be difficult to diagnose; thus, primary care providers should not hesitate to contact a dermatologist for advice and/or patient referral. The role of corticosteroids in triggering and leading to flares of GPP should also be noted, and physicians should avoid the use of systemic corticosteroids in the management of any form of psoriasis.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

A brief guide to pustular psoriasis for primary care providers

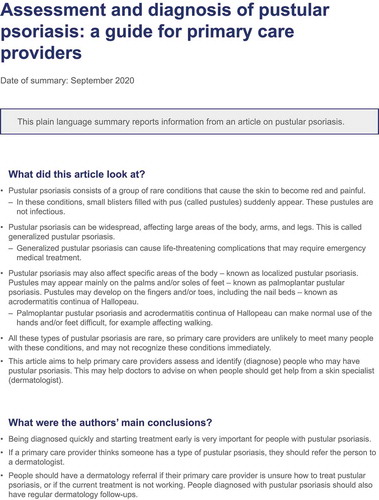

Pustular psoriasis consists of a group of rare conditions that cause the skin to become red and painful. In these conditions, small blisters filled with pus (called pustules) appear suddenly. The pustules are not infectious. Pustular psoriasis is different from plaque psoriasis, in which people develop scaly patches of skin. People can have pustular psoriasis and plaque psoriasis at the same time. Pustular psoriasis can be widespread, affecting large areas of the body, arms, and legs. This is called generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP). GPP can cause life-threatening complications that may require emergency medical treatment. Pustular psoriasis can be more localized, occurring on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. This is called palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP). It can also occur on the fingers, toes, and nail beds, called acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH). PPP and ACH can make walking and other everyday activities difficult. Because GPP, PPP, and ACH are rare, primary care providers are unlikely to meet many people with pustular psoriasis, so they may not recognize these conditions immediately. This article aims to help primary care providers assess and diagnose people who may have GPP, PPP, or ACH, and advise when they should get help from a skin specialist (dermatologist). See for a full infographic version of this summary.

1. Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated disease that primarily affects the skin (reviewed in [Citation1]), and up to 30% of affected individuals develop psoriatic arthritis [Citation2]. Moderate to severe psoriasis is a systemic disease associated with various comorbidities (reviewed in [Citation3,Citation4]), including cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome. Psoriasis is a multifactorial condition, involving a plethora of susceptibility genes and environmental triggers.

Prevalence of psoriasis in adults varies between 0.17% in east Asia to 2.50% in western Europe; estimated prevalence in the United States is 1.87% (95% uncertainty interval: 0.64% to 5.23%) [Citation5]. The most frequent clinical presentation is plaque psoriasis (psoriasis vulgaris), which accounts for >80% of cases [Citation1,Citation6]). Other presentations include guttate (droplet psoriasis), inverse (flexural, intertriginous psoriasis), and pustular psoriasis. Some patients may present with psoriasis localized to the palms and soles (palmoplantar psoriasis), while some patients may have disease only affecting the nails, or the scalp, or the genitals, and there may be no evidence of psoriasis elsewhere. In addition, erythrodermic psoriasis is a rare and severe variant that can develop from any type of psoriasis, or may be the first presentation of psoriasis. It is characterized by widespread inflammatory erythema involving most of the body surface area, and is a potentially life-threatening condition.

Table 2. Pustular psoriasis sub-types and summary of main features. GPP: generalized pustular psoriasis. Clinical photographs supplied by JJ Crowley, DM Pariser, and PS Yamauchi

Pustular psoriasis refers to a heterogeneous group of inflammatory skin disorders, characterized by the presence of neutrophil-filled pustules. Pustular psoriasis sub-types are clinically, histologically, and genetically distinct from plaque psoriasis [Citation7], although lesions can occur concurrently with those of plaque psoriasis [Citation8]. Pustular psoriasis may present as a disseminated systemic illness (generalized pustular psoriasis [GPP]), or a localized disease affecting the palms/soles (palmoplantar pustulosis [PPP], also known as palmoplantar pustular psoriasis), or digits/nail beds (acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau [ACH]) [Citation9–11]. Pustular psoriasis is rare, accounting for ~1% of all cases of psoriasis [Citation12]. Asian individuals tend to be affected by GPP more commonly than Caucasians. The estimated prevalence of GPP ranges from 1.76 per million in Europe to 7.46 per million in Japan [Citation13,Citation14]. The estimated prevalence of PPP ranges from 0.01% and 0.05% [Citation15]; although, one large Japanese study reported a national prevalence of 0.12% [Citation12].

Most cases of GPP are apparently idiopathic, but common precipitating factors include withdrawal of corticosteroid treatment in individuals with existing plaque psoriasis, certain medications such as lithium (reviewed in [Citation16]), infection, stress, and pregnancy [Citation17]. PPP is related to tobacco smoking (per data from case studies, reviewed in [Citation10]), and oral infection may be a triggering factor (per data from a retrospective analysis; PPP, n = 85) [Citation18]). ACH typically occurs after localized trauma or infection (reviewed in [Citation11]). Gene mutations resulting in activation of pro-inflammatory pathways have been reported in individuals with pustular psoriasis, mainly GPP. These include the gene encoding the interleukin (IL)-36 receptor antagonist (IL36RN) [Citation19–21], caspase-activating recruitment domain member 14 (CARD14) [Citation22], and adaptor protein complex 1 subunit sigma 3 (AP1S3) [Citation23]. In GPP, uncontrolled inflammatory signaling results in the recruitment and activation of immune cells (including neutrophils and macrophages) via the release of additional inflammatory mediators [Citation24]. Briefly, stimulation of the IL-36 receptor results in the activation of transcription factor NF-kB, and the secretion of IL-8 (a chemokine for neutrophils), pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF) -alpha, IL-1, and IL-23, and an increase in T-helper 17 cell activity. This causes a progressive cycle of inflammation, and further recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages, resulting in the histopathologic and macroscopic features of GPP. The suggested pathoimmunogenetic pathways are complex, and are reviewed in [Citation24–26]. A review of PPP pathoimmunogenetics was recently published [Citation27].

The aim of this brief review is to present current opinion for the evaluation and diagnosis of pustular psoriasis sub-types in the primary care setting, and particularly when to involve a dermatology specialist. Literature was retrieved using Boolean searches for English language articles in PubMed and Google Scholar, and included terms related to pustular psoriasis, GPP, PPP, and ACH. The reference lists from retrieved articles were also considered.

2. Clinical information for primary care providers

2.1. What are the most common symptoms and signs?

Details of pustular psoriasis sub-types are summarized in [Citation7,Citation9–11,Citation28,Citation29]. Briefly, acute GPP (also called von Zumbusch type) is the most severe presentation of pustular psoriasis [Citation7]. GPP is often characterized by intermittent flares of disease with periods of partial or complete remission. There is a rapid and widespread eruption of superficial pustules – these may coalesce into ‘lakes of pus’ – accompanied by systemic symptoms, commonly fever. The skin lesions are often extremely painful. Life-threatening complications (sepsis, renal, hepatic, and/or cardiorespiratory failure) and even death may ensue, and prognosis is worse in older individuals [Citation30]. Overall, GPP exhibits a highly unpredictable course, with flares varying in severity, duration, and frequency. Symptoms can resolve with limited intervention, or may require aggressive treatment.

Key points:

The diagnosis of GPP should be suspected in individuals with sudden onset erythema and pustulosis [Citation9].

The absence of systemic symptoms does not exclude the diagnosis [Citation7].

It is imperative to determine if the patient needs immediate hospitalization, due to the risk of complications [Citation9].

PPP is the most common sub-type of pustular psoriasis [Citation7]. It presents as an eruption of pustules on the palms and soles, accompanied by pain and pruritus. It has a chronic and relapsing course, and is associated with impaired health-related quality of life more than other types of psoriasis [Citation10]. Psychiatric disorders, including depression, have been associated with PPP. Recent DNA sequencing studies of PPP pustular material report that the pustules contain specific bacterial microbiomes, rather than being sterile (thought to be so because bacterial cultures from PPP pustules are frequently negative) [Citation31].

Key point:

PPP is a potentially debilitating condition requiring prompt and effective treatment.

ACH is characterized by the appearance of tender pustules on the tip of a digit (or digits) – affecting fingers more commonly than toes – with progressive destruction of the nail apparatus, and underlying bone erosions in severe cases [Citation7,Citation11]. ACH follows a chronic and progressive path.

Key point:

The threat of irreversible nail and/or bone damage necessitates the early treatment of individuals with ACH [Citation7].

2.2. What are the main approaches to diagnosis?

Diagnosis of GPP, PPP, and ACH is mainly clinical, and is based upon the patient’s history and presenting clinical features. The diagnostic criteria for GPP – originally presented in Japanese guidelines in 2003 [Citation32] – were discussed in treatment recommendations for pustular psoriasis from the US National Psoriasis Foundation (2012) [Citation33]. Preliminary consensus definitions for the classification and diagnosis of pustular psoriasis sub-types have been developed by the European Rare and Severe Psoriasis Expert Network (ERASPEN; [Citation8]).

Table 3. Definitions for the diagnosis of pustular psoriasis from the European Rare and Severe Psoriasis Expert Network [Citation8]

In terms of medical history, individuals should be asked about a history or family history of psoriasis or pustular psoriasis, and recent use of medication (e.g. corticosteroids and their association with GPP flare; a new prescription and possible acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis [AGEP] – see below). Laboratory tests may be necessary to assess disease severity, and the extent of any systemic complications associated with acute GPP, including the following [Citation9,Citation30,Citation34]: a) inflammation – leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein, increased plasma globulins (IgG or IgA); b) loss of plasma proteins into tissues – hypoproteinemia and hypocalcemia; c) oligemia – elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine; d) liver damage – elevated aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, and/or bilirubin; e) kidney damage – positive urinary albumin; and f) secondary bacterial infection – positive bacterial cultures (pustules and/or blood). Histopathological examination of a skin biopsy (including pustule/s) confirms the diagnosis. (Detailed description is beyond the scope of this report, but can be found in these publications [Citation9–11].)

2.3. What are the differential diagnoses?

For GPP, the major diagnosis to exclude is AGEP [Citation9]. Clinically, it may be almost impossible to distinguish AGEP from GPP. The main clue would be a history of recent drug ingestion, as 90% of AGEP cases are associated with medication (commonly certain types of antibiotic, and calcium channel blocker agents) [Citation35]. The main features of AGEP include [Citation35]: acute widespread appearance of pinhead-sized sterile pustules, with erythema, edema, fever, and leukocytosis (the illness is usually mild, <5% mortality). Furthermore, AGEP has a more abrupt onset and a shorter duration than GPP – AGEP signs/symptoms occur within 48 hours and resolve within 1 to 2 weeks – AGEP does not recur, and has no association with plaque psoriasis. Skin biopsy (including at least one intact pustule) should be taken for histopathological examination to distinguish AGEP from other pustular skin conditions [Citation35,Citation36]. Other differential diagnoses for GPP include localized forms of pustular psoriasis, IgA pemphigus [Citation37], and subcorneal pustular dermatosis (also called Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) [Citation38].

For localized sub-types of pustular psoriasis, the main differential diagnoses include PPP and ACH, pompholyx (also called dyshidrotic eczema, or acute and recurrent vesicular hand dermatitis), and nail infection (for ACH). Pompholyx is a chronic dermatitis characterized by the appearance of clusters of vesicles (clear blisters) on the palms and soles, accompanied by erythema and intense pruritus, and pustules may be present [Citation39]. It is rarely difficult to distinguish between PPP and pompholyx, although discriminatory histopathologic features have been described [Citation40]. Nail infection may be investigated by testing the pustule material (e.g. gram stain for possible bacterial infection; potassium hydroxide test for possible fungal infection; polymerase chain reaction testing for possible herpetic whitlow [Citation41]).

2.4. When should a patient be referred to a dermatologist?

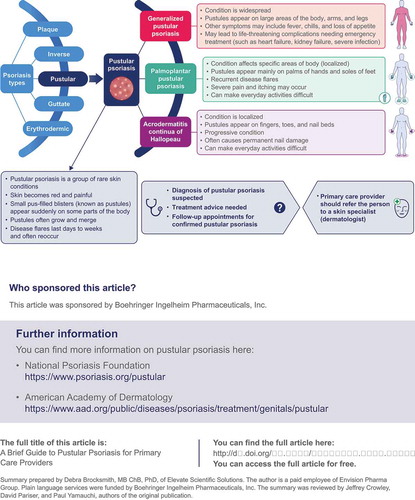

An individual with suspected pustular psoriasis should be referred to a dermatologist if there is any question about the diagnosis (). Individuals with GPP, suspected or confirmed, should always be referred to a dermatologist. Similarly, a dermatology referral should always be made for possible cases of ACH. For an individual with PPP, a referral should be made if topical treatments do not work (the diagnosis may be incorrect, and/or treatment choice may be incorrect). A patient with any sub-type of pustular psoriasis should see their dermatologist every 3 months, and/or as needed to manage the disease. The involvement of a rheumatologist may also be required if the patient has psoriatic arthritis, pustulotic arthro-osteitis (PAO; Sonozaki syndrome), or synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome. (PAO and SAPHO are reviewed in these reports [Citation42,Citation43].)

2.5. How are pustular psoriasis sub-types treated?

The rarity of pustular psoriasis sub-types, and the unpredictability of disease flares makes it extremely challenging to gather statistically significant data on treatment efficacy/safety. Consequently, there is a lack of up-to-date guidelines for the management of GPP, PPP, and ACH in the United States and Europe (although updated Japanese guidelines on the management and treatment of GPP were published in 2018 [Citation34]). The current range of treatment options is limited, and generally involves agents used to treat plaque psoriasis. No specific treatment for any sub-type of pustular psoriasis has been approved in the United States to date (although, several biologic agents have been approved in Japan for the treatment of GPP). Once the diagnosis of pustular psoriasis is made, treatment needs to be prompt to reduce disease severity and the risk of progression and/or complications.

Treatment of pustular psoriasis sub-types in adults may involve the use of topical agents, systemic agents, phototherapy, and/or targeted immunomodulatory therapy with biologic agents (reviewed in [Citation28,Citation44]). Immunomodulatory therapies are broadly used in the treatment of GPP – based on anti-plaque psoriasis strategies – but their benefit:risk profiles have not been established, and there is limited evidence supporting their efficacy and safety in treating GPP (as well as PPP and ACH) [Citation45]. Thus, there is a high unmet need for treatments that specifically target GPP (and PPP). While biologics may have a rapid onset of action and safety advantages over traditional systemic agents, the latter remain important as they are administered orally (biologics are usually given via subcutaneous injection), and have lower costs [Citation1]; thus, payer approval/prior authorization is usually less problematic. Topical therapy includes corticosteroids, and vitamin D derivatives. Systemic therapy includes acitretin, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and corticosteroids. There are potential safety issues with acitretin (osteoarticular symptoms), cyclosporine (hypertension, renal dysfunction), and methotrexate (hepatotoxicity, hematologic toxicity). Acitretin and methotrexate are also contraindicated during pregnancy. Corticosteroids should be used with great care, as non-tapered withdrawal in individuals with existing plaque psoriasis may precipitate pustular flares. Phototherapy includes psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA), and narrow-band ultraviolet B (NB-UVB). Oral psoralen is contraindicated during pregnancy. Biologics include anti-TNF-alpha, anti-IL-17, anti-IL-12/23, and anti-IL-23 agents. These agents are associated with a potentially increased risk of infection. To date, infliximab (anti-TNF-alpha) and ustekinumab (anti-IL-23) have the most evidence of efficacy and safety for the treatment of pustular psoriasis [Citation45]. Anti-IL-36 agents are in clinical development for GPP and PPP indications. Data on the use of small molecules in pustular psoriasis sub-types are sparse, although Janus kinase inhibitors are being studied as a possible treatment for plaque psoriasis [Citation46].

For adults with acute GPP, first-line treatment includes initiation of systemic therapy (acitretin, cyclosporine, methotrexate, a biologic agent [e.g. anti-TNF-alpha agent, infliximab] [Citation33]), plus appropriate supportive measures [Citation30]. To gain disease control, a dermatologist may utilize combination therapy of a biologic plus another systemic agent, or sequential use of two biologics. Phototherapy can be used when the disease becomes less severe. Individuals with acute GPP may need to be hospitalized for fluid management, and/or treatment of ensuing heart failure. Antibiotic therapy may also be administered to prevent secondary bacterial infection. Treatment of pregnant women with acute GPP requires additional considerations, as untreated GPP is associated with adverse effects on maternal and fetal health (e.g. increased risk of placental insufficiency, fetal anomalies, fetal death) (reviewed in [Citation29]). Some medications are contraindicated in patients who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant (e.g. retinoids, methotrexate, oral psoralen), and care should be taken with other medications during breast-feeding (e.g. cyclosporine). PPP is often recalcitrant to treatment [Citation10]. Topical therapies are commonly used first (including corticosteroids, calcipotriol, and combination products), followed by agents including PUVA, NB-UVB, acitretin, methotrexate, cyclosporine, or a biologic. ACH is also notoriously difficult to treat [Citation11]. Topical therapies may help some individuals (including combination products, such as calcioptriol plus betamethasone). However, systemic therapy or biologic agents are often needed to obtain a good clinical response (usually in combination with topical agents), particularly for nail lesions.

3. Case studies (hypothetical) for evaluation and diagnosis of pustular psoriasis sub-types

3.1. GPP following systemic steroid use

A 48-year-old woman presented to her primary care provider with worsening dermatitis affecting her hands and arms. No trigger factor was identified (formal allergen testing was not done). Topical medications had minimal effect, and the primary care provider prescribed a course of oral prednisone. The dermatitis improved, and the prednisone dose was decreased. During this period, the patient presented to the emergency room with a painful skin eruption that had started on her abdomen, and had become widespread over subsequent hours. She now had confluent erythema with small pustular lesions over her trunk, arms, and legs. Some areas of pustulation on her legs had become confluent. In addition, the patient had general malaise, anorexia, fever, and was in severe pain. The emergency room physician diagnosed an infection. Due to the seriousness of the symptoms, hospitalization was indicated, and the patient was admitted for intravenous antibiotic therapy, and fluid replacement. After 2 days of persistent fever, and worsening of the pustular skin lesions, the patient was seen by a dermatologist, who diagnosed GPP.

3.2. PPP following azithromycin use

A 60-year-old man visited his primary care provider with a 2-month history of what he described as painful burning blisters on the palms and soles. The patient had long-standing (and relatively mild) plaque psoriasis on his elbows, knees, and scalp, which was being treated topically. The blisters in the presenting complaint started as discrete lesions, and progressed to involve most of the palmar and plantar surfaces. The primary care provider correctly observed that the lesions were pustules (i.e. contained purulent material) and not vesicles (i.e. contained fluid), and assumed that the psoriasis was becoming infected – even though there was no previous history of plaque psoriasis on the patient’s hands or feet. A specimen for bacterial culture was obtained, and the patient was empirically started on a 3-day azithromycin oral dose pack. When the patient returned after 1 week, there had been no change in the severity of the lesions, but the patient was now complaining of more pain and burning. The bacterial culture showed no growth, but the primary care provider assumed that it was falsely negative, repeated the culture, prescribed a 7-day course of a cephalosporin antibiotic, and made an urgent referral to a dermatologist. Upon examining the patient, the dermatologist noted scaly plaques on the extremities and scalp covering approximately 8% of the body surface area, and documented the presence of individual and confluent pustules covering most of the surface of the palms and soles (). A diagnosis of PPP was made.

4. Conclusions

Primary care providers have a vital role in psoriasis care, and it is important that they are familiar with all the clinical presentations of psoriasis, including pustular psoriasis. Although rare, the potential severity of GPP, PPP, and ACH – and their consequences – should not be underestimated. Because primary care providers are unlikely to encounter many patients with pustular psoriasis sub-types, unfamiliarity inevitably renders evaluation and diagnosis difficult. Thus, primary care providers should not hesitate to contact a dermatologist for help, and prompt patient referral. Patients should be educated about pustular psoriasis, and advised of any advancements in treatment. In addition, primary care providers can help to avoid the overuse of systemic corticosteroids in psoriasis, as even a single course of corticosteroids (oral or intramuscular) can trigger a pustular psoriasis flare in individuals who are predisposed to these conditions.

5. Useful resources

NIH, US National Library of Medicine, Genetics Home Reference: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/generalized-pustular-psoriasis

DermNetNZ:https://dermnetnz.org/topics/generalized-pustular-psoriasis/

American Academy of Dermatology:https://www.aad.org/member/clinical-quality/guidelines/psoriasis

National Psoriasis Foundation:https://www.psoriasis.org/primary-care-and-psoriatic-disease

Medscape Dermatology, Psoriasis:https://www.medscape.com/resource/psoriasis

Contribution statement

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, critical review, revision, and approval of the final version of this manuscript.

Data sharing

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no new data were created or analyzed in this report.

Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

JJC: Acted as a consultant/speaker/investigator for Abbvie, Lilly, Novartis, Janssen, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, and UCB; acted as a consultant/investigator for Dermira; acted as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim; acted as an investigator for Merck, Pfizer, Sandoz, MC2 Therapeutics, and Verrica Pharmaceuticals.

DMP: Acted as a consultant for Atacama Therapeutics, Bickel Biotechnology, Biofrontera AG, BMS, Celgene Corporation, Dermira, LEO Pharma US, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., Pfizer Inc., Regeneron, Sanofi, TDM SurgiTech, Inc., TheraVida, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International; and received grant funding from Abbott Laboratories, Almirall, Amgen, AOBiome LLC, Asana Biosciences LLC, Bickel Biotechnology, Celgene Corporation, Dermavant Sciences, Dermira, Eli Lilly and Company, LEO Pharma US, Menlo Therapeutics, Merck & Co., Inc., Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., Novo Nordisk A/S, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer Inc., Regeneron, Stiefel (a GlaxoSmithKline company), and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International.

PSY: Speaker, consultant, investigator for Abbvie, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, LEO, Lilly, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, Sun Pharma, UCB; Consultant and investigator for Arcutis, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dermavant, Anaptys Bio.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance, supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (BIPI), was provided by Debra Brocksmith, MB ChB, PhD, of Elevate Scientific Solutions during the preparation of this manuscript. BIPI was given the opportunity to check the data used in this manuscript for factual accuracy only.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lebwohl M. Psoriasis. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(7):ITC49–ITC64.

- National Psoriasis Foundation. About psoriatic arthritis; [ cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriatic-arthritis

- Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):377–390.

- Furue M, Tsuji G, Chiba T, et al. Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases comorbid with psoriasis: beyond the skin. Intern Med. 2017;56(13):1613–1619.

- Global Psoriasis Atlas. Statistics; [ cited 2020 Jun 24]. Available from: https://globalpsoriasisatlas.org/statistics/prevalence

- World Health Organization. Global report on psoriasis; 2016 [cited 2020 Jun 24]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204417

- Bachelez H. Pustular psoriasis: the dawn of a new era. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(3):adv00034.

- Navarini AA, Burden AD, Capon F, et al. European consensus statement on phenotypes of pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(11):1792–1799.

- Ly K, Beck KM, Smith MP, et al. Diagnosis and screening of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2019;9:37–42.

- Misiak-Galazka M, Zozula J, Rudnicka L. Palmoplantar pustulosis: recent advances in etiopathogenesis and emerging treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(3):355–370.

- Smith MP, Ly K, Thibodeaux Q, et al. Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau: clinical perspectives. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2019;9:65–72.

- Kubota K, Kamijima Y, Sato T, et al. Epidemiology of psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a nationwide study using the Japanese national claims database. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006450.

- Augey F, Renaudier P, Nicolas JF. Generalized pustular psoriasis (Zumbusch): a French epidemiological survey. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16(6):669–673.

- Ohkawara A, Yasuda H, Kobayashi H, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis in Japan: two distinct groups formed by differences in symptoms and genetic background. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76(1):68–71.

- Miyazaki C, Sruamsiri R, Mahlich J, et al. Treatment patterns and healthcare resource utilization in palmoplantar pustulosis patients in Japan: A claims database study. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232738.

- Balak DM, Hajdarbegovic E. Drug-induced psoriasis: clinical perspectives. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2017;7:87–94.

- Choon SE, Lai NM, Mohammad NA, et al. Clinical profile, morbidity, and outcome of adult-onset generalized pustular psoriasis: analysis of 102 cases seen in a tertiary hospital in Johor, Malaysia. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(6):676–684.

- Kouno M, Nishiyama A, Minabe M, et al. Retrospective analysis of the clinical response of palmoplantar pustulosis after dental infection control and dental metal removal. J Dermatol. 2017;44(6):695–698.

- Marrakchi S, Guigue P, Renshaw BR, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):620–628.

- Onoufriadis A, Simpson MA, Pink AE, et al. Mutations in IL36RN/IL1F5 are associated with the severe episodic inflammatory skin disease known as generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(3):432–437.

- Bachelez H, Choon SE, Marrakchi S, et al. Inhibition of the interleukin-36 pathway for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(10):981–983.

- Berki DM, Liu L, Choon SE, et al. Activating CARD14 mutations are associated with generalized pustular psoriasis but rarely account for familial recurrence in psoriasis vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(12):2964–2970.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Simpson MA, Navarini AA, et al. AP1S3 mutations are associated with pustular psoriasis and impaired Toll-like receptor 3 trafficking. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94(5):790–797.

- Johnston A, Xing X, Wolterink L, et al. IL-1 and IL-36 are dominant cytokines in generalized pustular psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(1):109–120.

- Ogawa E, Sato Y, Minagawa A, et al. Pathogenesis of psoriasis and development of treatment. J Dermatol. 2018;45(3):264–272.

- Furue K, Yamamura K, Tsuji G, et al. Highlighting interleukin-36 signalling in plaque psoriasis and pustular psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(1):5–13.

- Murakami M, Terui T. Palmoplantar pustulosis: current understanding of disease definition and pathomechanism. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98(1):13–19.

- Benjegerdes KE, Hyde K, Kivelevitch D, et al. Pustular psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2016;6:131–144.

- Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Women’s Health. 2018;10:109–115.

- Cockerell CJ. Pustular psoriasis; 2019 [cited 2020 Jun 26]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1108220-overview

- Masuda-Kuroki K, Murakami M, Tokunaga N, et al. The microbiome of the “sterile” pustules in palmoplantar pustulosis. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(12):1372–1377.

- Umezawa Y, Ozawa A, Kawasima T, et al. Therapeutic guidelines for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) based on a proposed classification of disease severity. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295(Suppl 1):S43–S54.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the medical board of the national psoriasis foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(2):279–288.

- Fujita H, Terui T, Hayama K, et al. Japanese guidelines for the management and treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis: the new pathogenesis and treatment of GPP. J Dermatol. 2018;45(11):1235–1270.

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(8):1214.

- Kardaun SH, Kuiper H, Fidler V, et al. The histopathological spectrum of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) and its differentiation from generalized pustular psoriasis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37(12):1220–1229.

- Estupiňan BA. IgA pemphigus; 2017 [cited 2020 Jun 28]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1063776-overview

- Sekulovic LK. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis; 2019 [cited 2020 Jun 28]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1124252-overview

- Amini S. Dyshidrotic eczema (pompholyx); 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 03]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1122527-overview

- Masuda-Kuroki K, Murakami M, Kishibe M, et al. Diagnostic histopathological features distinguishing palmoplantar pustulosis from pompholyx. J Dermatol. 2019;46(5):399–408.

- Schremser V, Antoniewicz L, Tschachler E, et al. Polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of herpesvirus infections in dermatology: analysis of clinical data. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2020;132(1–2):35–41.

- Kose R, Senturk T, Sargin G, et al. Pustulotic arthro-osteitis (Sonozaki Syndrome): a case report and review of literature. Eurasian J Med. 2018;50(1):53–55.

- Liu S, Tang M, Cao Y, et al. Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis syndrome: review and update. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020;12:1759720X20912865.

- Gooderham MJ, Van Voorhees AS, Lebwohl MG. An update on generalized pustular psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15(9):907–919.

- Falto-Aizpurua LA, Martin-Garcia RF, Carrasquillo OY, et al. Biological therapy for pustular psoriasis: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(3):284–296.

- Fragoulis GE, McInnes IB, Siebert S. JAK-inhibitors. New players in the field of immune-mediated diseases, beyond rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(Suppl 1):i43–i54.